Abstract

Background:

Accurately determining the pathogenicity of newly discovered POLE mutations is crucial for the precise molecular classification of endometrial carcinoma.

Methods:

In one patient with endometrial carcinoma, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed to detect variants in POLE, TP53, BRCA1/2, CTNNB1, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, as well as microsatellite instability (MSI) status in the tumor tissues. Variant interpretation followed ACMG/AMP guidelines, integrating evidence from literature, established guidelines, public databases, and clinical studies. Immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6, and p53 protein expression in tumor tissues.

Results:

We successfully identified a novel potential missense mutation, c.1381T>C: p.(S461P), in exon 14 of POLE. This variant, reported here for the first time in endometrial carcinoma, was preliminarily classified as likely pathogenic based on available evidence. Additional variants were detected: TP53: c.844C>T: p.(R282W), TP53: c.711G>A: p.(M237I), and MSH6: c.3103C>T: p.(R1035*). The MSI status was classified as MSI-L. Immunohistochemistry revealed MLH1 (+), PMS2 (+), MSH2 (+), MSH6 (−), and p53 expression consistent with a mixed pattern (80% tumor region wild type, 20% region mutant subtype).

Conclusion:

This is the first report of the POLE (c.1381T>C: p.(S461P)) variant in endometrial carcinoma. We analyzed its potential pathogenic mechanism, which may contribute to the complex molecular phenotype of POLEmut + MMRd + p53abn tumors, and expanded the POLE mutation spectrum by adding a new likely pathogenic site.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is among the most common malignant tumors in the female reproductive system. Surgery is the standard treatment, and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy is tailored according to pathological and clinical factors. However, traditional clinical staging and histopathological classification have limitations in achieving accurate classification, individualized treatment, and precise prognostication (1). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project used a multi-platform analysis database to classify EC into four molecular subtypes: DNA polymerase ϵ (POLE) super mutation type, high MSI (MSI-H) type, low copy type, and high copy type. This classification, combining pathological assessment and molecular typing, has opened a new era for EC diagnosis and treatment (2).

POLE is located on chromosome 12q24.3, spanning 63,604 bp of cDNA, and encodes the largest catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ϵ (3). It has two key catalytic functions, template-based DNA polymerase activity and exonuclease proofreading activity, both essential for DNA replication and base mismatch repair (MMR). Mutations within the exonuclease domain can abolish proofreading activity, increase gene instability, and prevent the removal of mismatched bases, thereby elevating the number of genomic mutations and damage to cells and ultimately increasing tumor risk (4). POLE mutations occur in approximately 7-12% of EC cases, representing one of the highest rates among human malignancies (5). In high-grade endometrioid EC, POLE mutations are associated with improved prognosis, including longer overall survival and progression-free survival (6, 7). POLE have five common hotspot mutations, namely P286R, V411L, S297F, A456P, and S459F, encompassing 95.3% of the known pathogenic mutation sites (8). However, when whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data are unavailable, defining and classifying low-frequency mutations, variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and novel mutations is highly challenging, complicating clinical decision-making. Given that adjuvant therapy for early-stage POLE-mutant EC can often be safely de-escalated, accurate identification and classification of pathogenic POLE variants are essential for molecular subtyping and optimal treatment planning (8, 9).

In this report, we describe a case of EC with a complex molecular profile (POLE mut +MMRd +p53abn) in which we identified a previously unreported missense variant, c.1381T>C: p.(S416P), located in exon 14 of POLE. Through comprehensive molecular profiling and bioinformatics analysis, we classified this variant as likely pathogenic.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the Gynecology Department of Liaocheng People’s Hospital with a 2-month history of spontaneous, light vaginal bleeding. She had experienced natural menopause at age 52 and had no family history of gynecologic malignancies or genetic predisposition disorders.

Initial transvaginal ultrasound revealed a 2.3 × 1.0-cm heterogeneous intrauterine mass. The patient then underwent diagnostic hysteroscopy with dilation and curettage (D&C). Frozen section analysis of the curetting confirmed endometrioid carcinoma.

A laparoscopic total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was subsequently performed. Gross pathological findings of the surgical specimen included: uterine size: 5.5 × 5.5 × 3.5 cm; tumor location: endometrium of the fundus; tumor size: 2.5 × 1.8 × 1.5 cm; appearance: grayish, friable with irregular borders; myometrial invasion: <50% of uterine wall thickness; cervical stromal involvement: absent; cervical canal: intact. A gross picture of this surgically removed uterus was presented in Supplementary Material 1.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liaocheng People’s Hospital (No. 2024027).

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the Ventana Benchmark XT chromatograph. The antibodies to be used in the test were purchased from Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. with antibody clone numbers: MLH1 (ES 05, mouse mAb), PMS2 (EP51, rabbit mAb), MSH2 (RED 2, rabbit mAb), MSH6 (EP49, rabbit mAb), and p53 (DO-7, murine mAb). Immunohistochemical testing was performed following the corresponding seller’s instructions.

Detection of molecular subtyping of endometrial carcinoma

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed to detect the tumor tissues for POLE, TP53, BRCA1/2, CTNNB1, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 and MSI. The detection reagent was molecular typing of endometrial carcinoma and genetic susceptibility gene mutation (HANDLE System) (AmoyDx, Xiamen, China), and the instrument model was Illumina NextSeq 550. Library construction and sequencing were performed in accordance with the reagent and sequencer manufacturer’s instructions. NGS result interpretation criteria: effective depth (Depth) 30, variant frequency (Freq): 3%, effective sequencing depth (AltDepth): 5, MSI site ratio (MSI _ Ratio): 15%. When the MSI _ Ratio value was detected in the 12–24% interval, verification by PCR-capillary electrophoresis was recommended.

MSI detection

The status of the five single-nucleotides (i.e., BAT-25, MONO-27, CAT-25, BAT-26, and NR-24) in the tumor tissues and normal control tissues was determined by fluorescence PCR-capillary electrophoresis. The detection reagent was the human MSI detection kit (AmoyDx), the detection instrument was ABI3500 Dx Genetic Analyzer, and the MSI-detection sensitivity was 5%. MSI was performed as per the reagent and instrument manufacturer’s instructions. MSI result interpretation criteria: using normal tissue as the control, 2 or more of the five markers changes were defined as MSI-H; only 1 marker change was defined as low MSI (MSI-L); no detected marker change was defined as microsatellite stability (MSS).

Bioinformatic analysis

After sequencing, the test data were analyzed by using the “Human Cancer Polygene Mutation Analysis software” from AmoyDx, which yielded variant outcomes for the POLE, TP53, BRCA1/2, CTNNB1, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, and the MSI results. The detected genetic variants were interpreted based on published literature, guidelines, public databases, and clinical findings. Evidence was carefully examined in the population databases (e.g., 1000 Genomes, ExAC, gnomAD, and iJGVD) to determine the allele frequencies. Further investigations of the variants included ClinVar, OncoKB, VarSome, and other mutation databases, and the evidence was extracted from the existing literature or case reports. Subsequently, grades of evidence were assigned based on the functional studies, clinical trials, co-isolation, disease incidence, and other associated factors. The interpretation of variants was performed as per the Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting of Tumor Variations (2017 edition), jointly developed by the American Society of Pathology (AMP), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the American Society of Pathologists (CAP) (10). The gene variants are divided into four grades based on their clinical significance: class I (with a strong clinical significance), class II (with a potential clinical significance), class III (with unknown clinical significance), and class IV (these are benign and possibly benign variants, with no known clinical significance).

Results

Pathology and immunohistochemical results

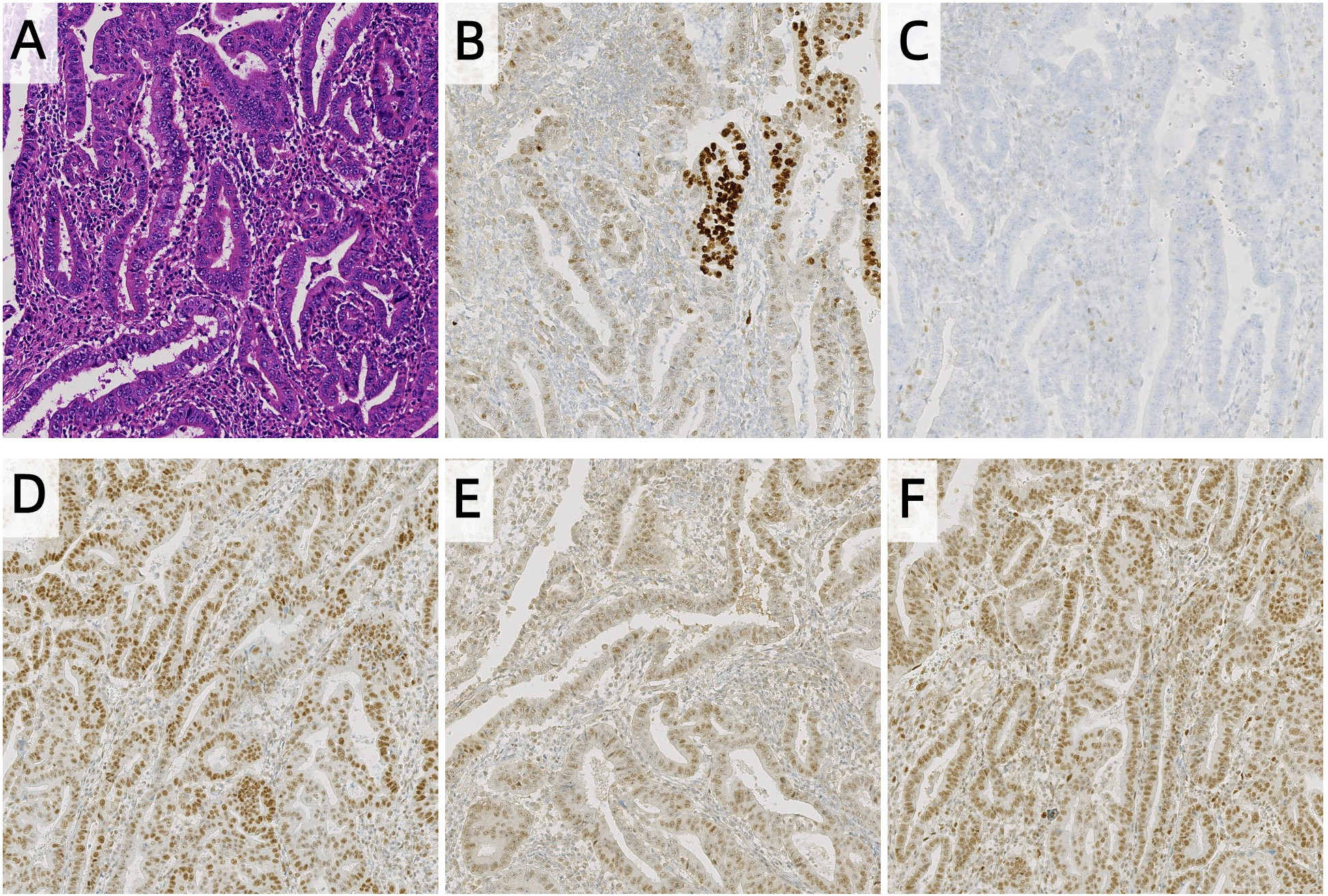

Postoperative histopathological examination confirmed endometrioid adenocarcinoma (grade 2, according to the 2023 FIGO grading system) with myometrial invasion limited to the inner half. No tumor was involved in the uterine serosa, cervix, lymphovascular spaces, or blood vessels. Lymph node analysis unveiled no metastases (0/17 right pelvic, 0/9 left pelvic, and 0/7 para-aortic lymph nodes). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated intact MLH1, PMS2, and MSH2 expression, but complete loss of MSH6. p53 staining showed a wild-type pattern in 80% of tumor areas and a mutant pattern in 20% (Figure 1). Based on the 2023 FIGO staging system (11), this case was classified as Stage IA, as the tumor was confined to the uterus with <50% myometrial invasion and no lymph node involvement.

Figure 1

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry of endometrial carcinoma, (A) HE, (B) p53, (C) MSH6, (D) MLH1, (E) PMS2, (F) MSH2 (100 ×). The expression of MSH6 in tumor cells is completely lost, while the interstitial blood vessels serve as a positive internal control. The p53 expression was heterogeneous, with 80% tumor region wild-type and 20% tumor region mutant subtypes.

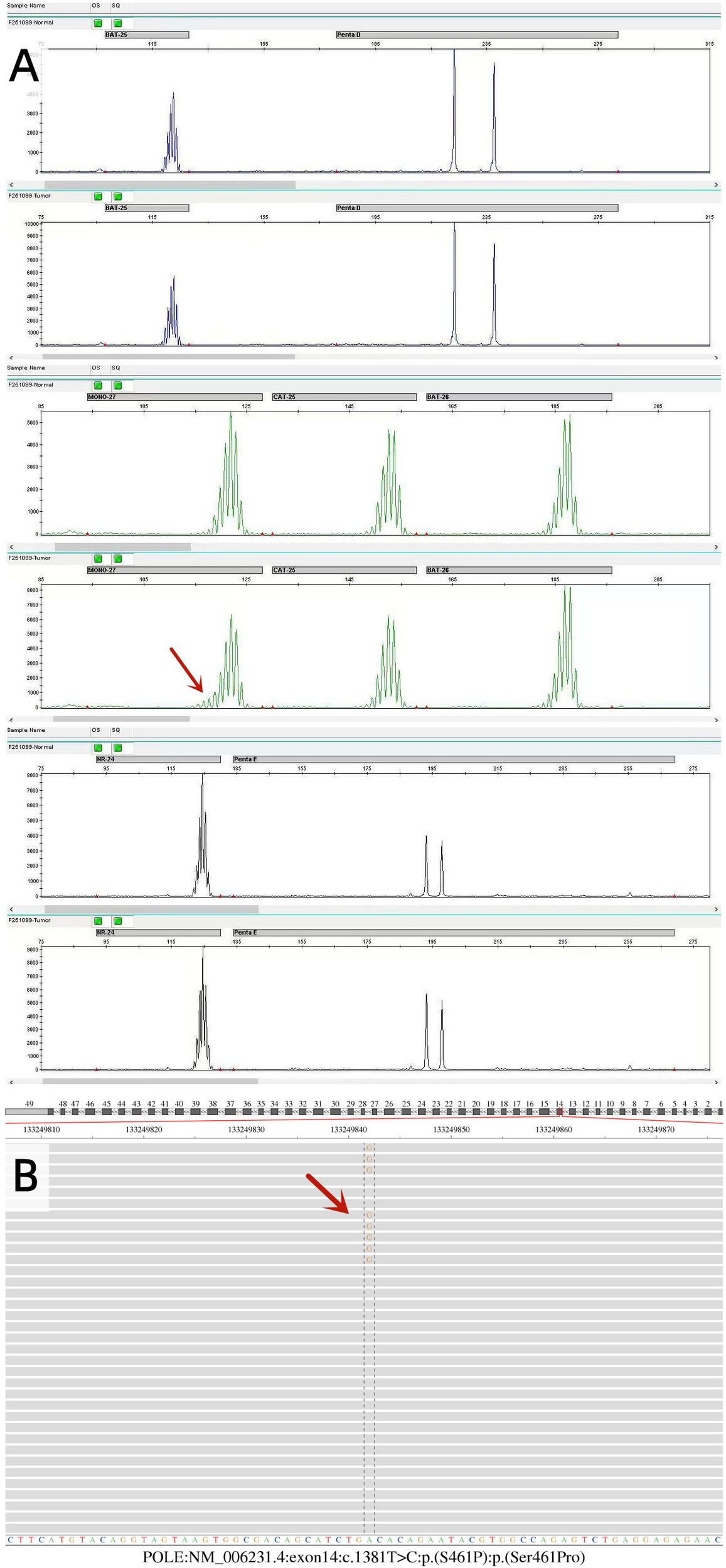

MSI results

NGS analysis of the tumor tissue revealed an MSI Ratio of 23.64%, falling within the 12%–24% range, necessitating PCR-capillary electrophoresis confirmation. Validation testing showed a change in the MONO-27 mononucleotide marker, with all other sites unchanged. The final result indicated MSI-L (Figure 2A).

Results of molecular subtyping of endometrial carcinoma

NGS detected a POLE variant in the tumor tissue: NM_006231.4: exon14: c.1381T>C: p.(S461P) (Figure 2B). This missense mutation substitutes serine with proline at amino acid position 461 in the gene-encoded protein. For the population data observation, the variant was not recorded in the 1000G, ExAC, gnomAD, and iJGVD databases, as well as in the ClinVar database. This variant was absent in population databases, supporting PM2 evidence. This variant is located in the ExoIII exonuclease motif, adjacent to the conserved exonuclease catalytic residue D462. For functional studies, in vitro experiments demonstrated that this variant caused loss of fidelity of genome duplications, significantly elevated mutation rates, and impaired polymerase proofreading compared with wild type (PMID: 25642631) (12). The results of functional studies confirmed the deleterious effect of this variant, supporting PS3 evidence. According to ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines, the cumulative evidence (PM2_Supporting + PS3) classifies the POLE c.1381T>C: p.(S461P) variant as “Likely Pathogenic,” with potential clinical significance for patient management decisions.

Figure 2

Molecular pathology findings of endometrial cancer. (A) The MSI results were detected by PCR-capillary electrophoresis. The MONO-27 mono-nucleotide status was changed in this sample, and the remaining sites remained unchanged, resulting in low microsatellite instability (MSI-L). (B) Sequencing results of the POLE gene. POLE: NM_006231.4: exon14: c.1381T>C p.(S461P) variant in the tumor tissue was detected using the NGS method.

Additionally, 16 other variants were identified in tumor tissues using NGS (Table 1). These included three pathogenic variants, TP53: NM_000546.6: exon8: c.844C>T: p.(R282W); BRCA2: NM_000059.4: exon11: c.6430G>T: p.(E2144*), BRCA2: NM_000059.4: exon14: c.7423G>T: p.(E2475*). The aforementioned variants were interpreted as class II variants (with potential clinical significance). Two additional likely pathogenic variants were also detected: TP53: NM_000546.6: exon7: c.711G>A: p.(M237I) (interpreted as Class II (with potential clinical significance)) and MSH6: NM_000179.3: exon4: c.3103C>T: p.(R1035*) (interpreted as Class III (with unclear clinical significance)). Nine likely benign variants and two variants of uncertain significance were also detected.

Table 1

| Gene | CDS change | Pathogenic classification | Variant level | Pathogenic evidences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPCAM | NM_002354.3:exon5:c.516G>A:p.(T172=):p.(Thr172=) | Likely benign | IV | BP4;BP7;PM2_Supporting |

| MSH2 | NM_000251.3:intron2:c.366+3A>G:p.?:p.? | Uncertain | III | BP4 |

| MSH6 | NM_000179.3:exon4:c.3103C>T:p.(R1035*):p.(Arg1035Ter) | Likely pathogenic | II | PVS1;PP4_Moderate |

| PMS2 | NM_000535.7:exon5:c.429T>C:p.(I143=):p.(Ile143=) | Likely benign | IV | BP4;BP7;PM2_Supporting |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:exon11:c.6430G>T:p.(E2144*):p.(Glu2144Ter) | Pathogenic | II | PM2_Supporting;PVS1;PM5_Strong |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:intron13:c.7008-4G>A:p.?:p.? | Uncertain | III | BP4;PM2_Supporting |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:exon14:c.7423G>T:p.(E2475*):p.(Glu2475Ter) | Pathogenic | II | PM2_Supporting;PVS1;PM5_Strong |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:intron18:c.8331+14C>T:p.?:p.? | Likely benign | IV | BP4;BP7 |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:exon22:c.8904C>T:p.(T2968=):p.(Thr2968=) | Likely benign | IV | BS1_Supporting;BP4;BP7 |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:exon27:c.10153C>T:p.(R3385C):p.(Arg3385Cys) | Likely benign | IV | BS1_Supporting;BP1_Strong |

| TP53 | NM_000546.6:exon11:c.1147C>A:p.(L383I):p.(Leu383Ile) | Likely benign | IV | BP4;BS3;PM2_Supporting |

| TP53 | NM_000546.6:exon11:c.1136G>A:p.(R379H):p.(Arg379His) | Likely benign | IV | BP4;BS3 |

| TP53 | NM_000546.6:exon7:c.711G>A:p.(M237I):p.(Met237Ile) | Likely pathogenic | II | PS3;PM1 |

| TP53 | NM_000546.6:exon5:c.474C>T:p.(R158=):p.(Arg158=) | Likely benign | IV | BS1;BS2_Supporting;BP4;BS3_Supporting |

| BRCA1 | NM_007294.4:exon11:c.2574G>A:p.(Q858=):p.(Gln858=) | Likely benign | IV | BP1_Strong;PM2_Supporting |

| TP53 | NM_000546.6:exon8:c.844C>T:p.(R282W):p.(Arg282Trp) | Pathogenic | II | PS4_Moderate;PP3_Moderate;PS3;PM1;PS2 |

Gene variants in endometrial cancers identified using NGS.

DNA quality and sequencing metrics are presented in Supplementary Material 2. Detailed sequencing data analysis is presented in Supplementary Material 3.

Discussion

The World Health Organization molecular classification scheme for EC can clearly categorize most cases into a single molecular subtype. However, 3.0%–11.4% of ECs exhibit multiple molecular features (13), defined by four combinations: POLEmut + p53abn, MMRd + p53abn, POLEmut + MMRd, and POLEmut + MMRd + p53abn. According to preliminary testing, our case falls into the rare POLEmut + MMRd + p53abn category, which accounts for approximately 0.3%–0.7% of all EC cases (14). Although these cases with complex molecular features account for a relatively small proportion of the overall cohort, they exhibit significant differences in treatment decisions and prognosis. For specific patient populations, such as those considering fertility-preserving treatment, these characteristics are particularly crucial.

First, we detected the POLE c.1381T>C: p.(S461P) variant. This variant, unrecorded in population databases including 1000G, ExAC, and gnomAD, is the first finding in EC, although three cases were previously reported in ultra-hypermutated malignant brain tumors (12). Although S461P is not a known POLE hotspot mutation, but affects a key amino acid residue in the ExoIII exonuclease motif adjacent to D462, a universally conserved catalytic site in all polymerases (15). Somatic POLE exonuclease domain driver mutations impair proofreading, resulting in high tumor mutation burden (TMB) (16). In previous studies, when assessing how the POLE mutation affects the proofreading ability of Pol ϵ, the S461P mutation was introduced into the structure encoding the Pol ϵ catalytic subunit, and mutation accumulation was measured in vitro. The results confirmed that the S461P mutation compromises replication fidelity and increases mutation rates (12). Collectively, this evidence supports its classification as a likely pathogenic variant.

Second, we also detected the MSH6: c.3103C>T: p.(R1035*) likely pathogenic variant and loss of MSH6 protein expression, but MSI testing revealed MSI-L rather than MSI-H. Such MMRd is inconsistent with MSI-L results often for the following reasons. The MSS state remains unchanged because of the MMR system’s functional compensation. Loss of MSH6 protein expression together with MSS was the most common discordant type. This was partly caused by the functional compensation of MSH3 for the MSH6 protein. Even when the MSH6 protein is damaged, the MSH2/MSH3 continues to function, and DNA mismatch is corrected and repaired. Meanwhile, MSH6 primarily recognizes single-base mismatches; MSI testing based on dinucleotide repeats may miss such defects (17, 18). In this case, PCR-capillary electrophoresis of five mononucleotide loci (BAT-25, MONO-27, CAT-25, BAT-26, NR-24) showed changes only in MONO-27, explaining the MSI-L finding. Therefore, we speculate that the inconsistency between MMRd and MSI-L in this case may be because MSH2/MSH3 partially compensates for the MSH6 protein function. Furthermore, as Stelloo et al. (19) reported, POLE mutations may themselves impair MMR, contributing to the accumulation of mutations and the observed discordance between immunochemistry and MSI results.

Furthermore, in this EC patient, we detected a pathogenic TP53 variant (c.844C>T: p.(R282W), a likely pathogenic TP53 variant (c.711G>A; p.M237I), and subclonal abnormal p53 protein expression. These focal abnormal expression patterns suggest the presence of complex genetic and epigenetic alterations, potentially related to TP53 mutations or other related gene variants. Studies have reported that approximately 60% of “MMRd + p53abn” and 46.7% of “POLEmut + p53abn” ECs show subclonal abnormal expression of p53 protein (13, 20). Regarding gene mutation characteristics, hierarchical clustering of single nucleotide variant (SNV) profiles and somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) from TCGA data demonstrates that most “MMRd + p53abn” ECs cluster with single-molecule MMRd tumors, rather than single-molecule p53 abnormal ECs. Similarly, “POLEmut + p53abn” ECs typically cluster with single-molecule classified POLE-mutant ECs rather than with single-molecule p53-abnormal ECs (13). These findings suggest that TP53 mutations may be “passenger” events in POLEmut or MMRd ECs that do not define the tumor’s molecular profile. Clinically, outcomes for stage I “POLEmut + p53abn” (5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) of 94.1%) and “MMRd + p53abn” (92.2%) ECs are significantly better than for single-molecule p53-abnormal ECs (70.8%) (13). Therefore, TP53 mutations in “POLEmut and/or MMRd + p53abn” ECs are likely secondary, non-driver passenger mutations with limited prognostic value. From a diagnostic perspective, cases cannot be simply classified as p53-abnormal EC solely based on TP53 mutations detected by NGS or abnormal p53 immunohistochemical staining. A comprehensive analysis incorporating POLE mutation status and MMR profiling is essential. In molecular typing of ECs, the abnormal staining of the p53 protein and the pathogenic mutation or suspected pathogenic mutation in TP53 can represent type p53abn only after the POLEmut and MMRd types are excluded.

In the present case, both a POLE and an MSH6 mutation were identified, making it challenging to accurately determine the primary driver of the tumor. Evidence suggests that POLE-hypermutated tumors display a predominance of SNVs and higher TMB, while MMR pathway–driven tumors more frequently harbor indel variations. ECs with POLEmut/MMR-proficient (MMRp) and POLEmut/MMRd profiles exhibit more SNVs, whereas small indel variations are enriched in POLEwt/MMRd ECs (21). POLEmut tumors typically have extremely high TMB (>100 mutations/Mb) and distinctive mutational signatures, including >20% of TCT → TAT bases turnover, >20% of TCG ➝ TTG base conversion, and approximately 7% of TTT ➝ TGT base turnover (22). TMB testing was not performed in this patient due to funding constraints. However, all 17 genetic variants identified in this tumor were SNVs, with 35% (6/17) being C>T base changes and 6% (1/17) being C>A base changes. Based on these features, we infer that genomic instability in this tumor was primarily driven by the POLE mutation. Regarding prognosis, Leon Castillo et al. analyzed 12 “POLEmut + MMRd” ECs among 3,361 EC cases and found that their genomic features and 5-year RFS (92.3%) were similar to those of single-molecule POLE-mutant ECs (8).

This case was classified as stage IA endometrial cancer according to the 2023 FIGO staging system (11). The NCCN Guidelines® for Uterine Neoplasms (2025) recommend risk-stratified postoperative management for stage IA disease based on histologic type, grade, molecular features, and other risk factors (23). The patient presented with endometrioid adenocarcinoma (grade 2), absence of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI-negative), and a POLE-mutated molecular subtype, which categorized her as low-risk stage IA with favorable prognosis. In accordance with NCCN guidelines, no adjuvant therapy was recommended, and only regular surveillance was advised. During follow-up, transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound at 1 and 4 months postoperatively showed no abnormalities, and serum CA-125 levels at 3 and 4 months postoperatively remained within normal range. Five months have elapsed since the surgery without any recurrence being observed.

In conclusion, this study is the first to report a POLE c.1381T>C (p.S461P) variant in EC, adding a novel potential pathogenic missense mutation to the POLE mutation spectrum. Through integrated molecular-pathological profiling, including MSH6 protein loss, MSH6 mutation, MSI-L status, subclonal p53 expression, and TP53 mutations, we explored potential mechanisms underlying the complex POLEmut + MMRd + p53abn molecular subtype. These findings improve our understanding of the molecular characteristics of POLE-mutant EC biology and underscore the critical importance of accurate POLE pathogenic variant interpretation in molecular classification.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Liaocheng People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. LW: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. LH: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ZZ: Methodology, Writing – original draft. JY: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1652864/full#supplementary-material.

References

1

Sung H Ferlay J Siegel RL Laversanne M Soerjomataram I Jemal A et al . Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2

Kandoth C Schultz N Cherniack AD Akbani R Liu Y Shen H et al . Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. (2013) 497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113

3

Park VS Pursell ZF . POLE proofreading defects: contributions to mutagenesis and cancer. DNA Repair. (2019) 76:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.02.007

4

Nicolas E Golemis EA Arora S . POLD1: Central mediator of DNA replication and repair, and implication in cancer and other pathologies. Gene. (2016) 590:128–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.031

5

. (!!! INVALID CITATION!!! (2, 5, 6)).

6

Casanova J Duarte GS da Costa AG Catarino A Nave M Antunes T et al . Prognosis of polymerase epsilon (POLE) mutation in high-grade endometrioid endometrial cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecologic Oncol. (2024) 182:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.01.018

7

McAlpine JN Chiu DS Nout RA Church DN Schmidt P Lam S et al . Evaluation of treatment effects in patients with endometrial cancer and POLE mutations: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Cancer. (2021) 127:2409–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33516

8

León-Castillo A Britton H McConechy MK McAlpine JN Nout R Kommoss S et al . Interpretation of somatic POLE mutations in endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol. (2020) 250:323–35. doi: 10.1002/path.5372

9

León-Castillo A Boer SMD Powell ME Mileshkin LR Bosse T . Molecular classification of the PORTEC-3 trial for high-risk endometrial cancer: impact on prognosis and benefit from adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:3388–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00549

10

Li MM Datto M Duncavage EJ Kulkarni S Lindeman NI Roy S et al . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer. J Mol Diagnostics. (2017) 19:4–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.002

11

Berek JS Matias-Guiu X Creutzberg C Fotopoulou C Gaffney D Kehoe S et al . FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. J Gynecologic Oncol. (2023) 34:e85. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2023.34.e85

12

Shlien A Campbell BB de Borja R Alexandrov LB Merico D Wedge D et al . Combined hereditary and somatic mutations of replication error repair genes result in rapid onset of ultra-hypermutated cancers. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:257–62. doi: 10.1038/ng.3202

13

León-Castillo A Gilvazquez E Nout R Smit VT McAlpine JN McConechy M et al . Clinicopathological and molecular characterisation of ‘multiple-classifier’ endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol. (2020) 250:312–22. doi: 10.1002/path.5373

14

Vitis LAD Schivardi G Caruso G Fumagalli C Vacirca D Achilarre MT et al . Clinicopathological characteristics of multiple-classifier endometrial cancers: a cohort study and systematic review. Int J gynecological cancer: Off J Int Gynecological Cancer Soc. (2024) 34:229–38. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2023-004864

15

Henninger EE Pursell ZF . DNA polymerase ϵ and its roles in genome stability. IUBMB Life. (2014) 66:339–51. doi: 10.1002/iub.1276

16

Shah SM Demidova EV Ringenbach S Faezov B Andrake M Gandhi A et al . Exploring co-occurring POLE exonuclease and non-exonuclease domain mutations and their impact on tumor mutagenicity. Cancer Res Commun. (2024) 4:213–25. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.crc-23-0312

17

Kunkel TA Erie DA . DNA MISMATCH REPAIR*. Annu Rev Biochem. (2005) 74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243

18

Wu Y Berends MJW Mensink RGJ Kempinga C Sijmons RH Zee A.G.J.V.D. et al . Association of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer–related tumors displaying low microsatellite instability with MSH6 germline mutations. Am J Hum Genet. (1999) 65:1291–8. doi: 10.1086/302612

19

Stelloo E Jansen AML Osse EM Nout RA Creutzberg CL Ruano D et al . Practical guidance for mismatch repair-deficiency testing in endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. (2017) 28:96–102. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw542

20

Huvila J Thompson EF Vanden Broek J Lum A Senz J Leung S et al . Subclonal p53 immunostaining in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma molecular subtype. Histopathology. (2023) 83:880–90. doi: 10.1111/his.15029

21

Moufarrij S Gazzo A Rana S Selenica P Abu-Rustum NR Ellenson LH et al . Concurrent POLE hotspot mutations and mismatch repair deficiency/microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer: A challenge in molecular classification. Gynecologic Oncol. (2024) 191:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.09.008

22

Hodel KP Sun MJS Ungerleider N Park VS Pursell ZF . POLE mutation spectra are shaped by the mutant allele identity, its abundance, and mismatch repair status. Mol Cell. (2020) 78:1166–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.012

23

Abu-Rustum NR Campos SM Amarnath S Arend R Barber E Bradley K et al . NCCN guidelines® Insights: uterine neoplasms, version 3.2025. J Natl Compr Cancer Network. (2025) 23:284–91. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2025.0038

Summary

Keywords

POLE gene, missense mutation, endometrial carcinoma, multiple−molecular features, molecular classification

Citation

Li Y, Wang L, Han L, Zheng Z and Yan J (2025) A novel missense mutation c.1381T>C: p.(S461P) in POLE causes multiple molecular features of endometrial carcinoma in China: a case report. Front. Oncol. 15:1652864. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1652864

Received

24 June 2025

Accepted

08 September 2025

Published

23 September 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Robert Fruscio, University of Milano Bicocca, Italy

Reviewed by

Lorenzo Ceppi, Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital, Italy

Chang Shi, Dalian Medical University, China

João Casanova, Hospital da Luz Lisboa, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Wang, Han, Zheng and Yan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zheng Zheng, sdzheng01@126.com; Jinqiang Yan, yanjinqiang1988@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.