- 1Northern Sydney Cancer Center, Royal North Shore Hospital, St Leonards, NSW, Australia

- 2The Mater Hospital, North Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Genesis Care, North Shore Health Hub, St Leonard, NSW, Australia

- 5Bowel Cancer and Biomarker Laboratory, Kolling Institute, St Leonard, NSW, Australia

Background: The gut microbiome may influence breast cancer (BC) development by modulating estrogen metabolism, immune responses, and microbial metabolites. Altered microbial patterns have been reported in BC, but their value as predictive biomarkers remains uncertain.

Methods: We reviewed 13 case–control studies that compared gut microbiome composition in women with and without BC, focusing on diversity, compositional shifts, and geographic variation.

Results: Reduced microbial richness (alpha diversity, the number and balance of bacterial species) was observed in more than half of the studies, although findings were not uniform. Differences in community composition (beta diversity) were common. Across studies, BC was consistently associated with elevated Bacteroides and reduced Faecalibacterium, a genus linked to anti-inflammatory effects. Other recurrent findings included enrichment of Eggerthella and Blautia in BC, though results for several taxa were inconsistent. Geographic variation was evident: Eggerthella was enriched in U.S. cohorts, Blautia in European cohorts, and in Chinese cohorts, Prevotella was elevated while Akkermansia was reduced.

Conclusions: Despite heterogeneity, converging evidence supports reduced diversity and shifts in select taxa, particularly enrichment of Bacteroides and depletion of Faecalibacterium, as emerging features of the BC microbiome. Geographic differences underscore the influence of host and environmental factors. These findings suggest biomarker potential but highlight the need for larger, longitudinal, and standardized studies to establish causality and clinical utility.

1 Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent cancer among women globally and remains a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality, despite significant advancements in early detection and treatment (1). Innovations such as advanced imaging techniques, minimally invasive surgeries, targeted therapies, immunotherapies, personalized medicine, radiation therapy, and multidisciplinary approaches have contributed to improved survival outcomes (2). However, approximately 20-30% of women diagnosed with early-stage BC, depending on the subtype, experience recurrence, often manifesting as metastatic disease (3, 4). This highlights the critical need for enhanced early detection strategies and innovative prognostic tools to improve therapeutic efficacy and survival outcomes.

Emerging evidence highlights the pivotal role of the gut microbiome in several cancers, including BC, where dysbiosis has been implicated in disease initiation, progression, and therapeutic response (5–9). Current evidence suggests that the gut microbiome influences BC risk by modulating systemic estrogen levels (10), metabolite production (11), and inflammatory responses. Elevated estrogen levels are well-documented risk factors for BC, with β-glucuronidase enzymes produced by certain gut bacteria facilitating estrogen reabsorption into the bloodstream, thereby contributing to BC pathogenesis (10, 12). Recent mechanistic studies also demonstrate that gut microbiota can regulate steroid hormone activity, immune modulation, and therapeutic response in BC, further underscoring their potential role as biomarkers and therapeutic targets (7, 13–15).

Several reviews have investigated the relationship between gut microbiome composition and BC. A systematic review of 10 case studies reported that BC patients exhibit decreased relative abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Prevotellaceae, Ruminococcus, Roseburia inulinivorans, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, alongside increased abundance of Bacteroides and Erysipelotrichaceae (16). However, findings across studies remain inconsistent, with variability linked to cancer stage, molecular subtype (11, 17, 18), menopausal status (10, 19), ethnicity, body mass index (20), diet (13), and medication use (21). Moreover, although prior reviews have highlighted mechanistic links between microbiota, estrogen metabolism, and BC progression, they have not adequately addressed how these associations may differ across geographical regions. This review, therefore, aims to fill this gap by synthesizing evidence on gut microbiome variations in BC across China, the USA, and Europe. By critically examining geographical differences, we seek to identify consistent microbial signatures, evaluate their potential as predictive biomarkers (22), and highlight directions for future research. Ultimately, this analysis may contribute to the development of microbiome-informed strategies that support personalized approaches to BC management.

2 Methods

We performed a mini-review of the literature through structured searches of PubMed, Medline, and ScienceDirect from database inception through December 2024. The search strategy included the terms “gut microbiome,” “gut microbiota,” “breast cancer,” and related synonyms. Reference lists of eligible articles were also screened. Eligible studies were peer-reviewed, English-language, human case–control studies comparing gut microbiome composition in adult women with BC and healthy controls. We excluded animal and preclinical studies, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and non-English publications. Data extracted from each study included participant characteristics, geographic setting, sequencing platform, measures of microbial diversity, and taxonomic findings. Owing to heterogeneity in study design, sequencing methodology (16S rRNA vs. metagenomics), and reported outcomes, quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, we undertook a narrative synthesis, with emphasis on consistent and divergent findings and on geographic patterns across cohorts from China, Europe, and the United States.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics and characteristics of studies

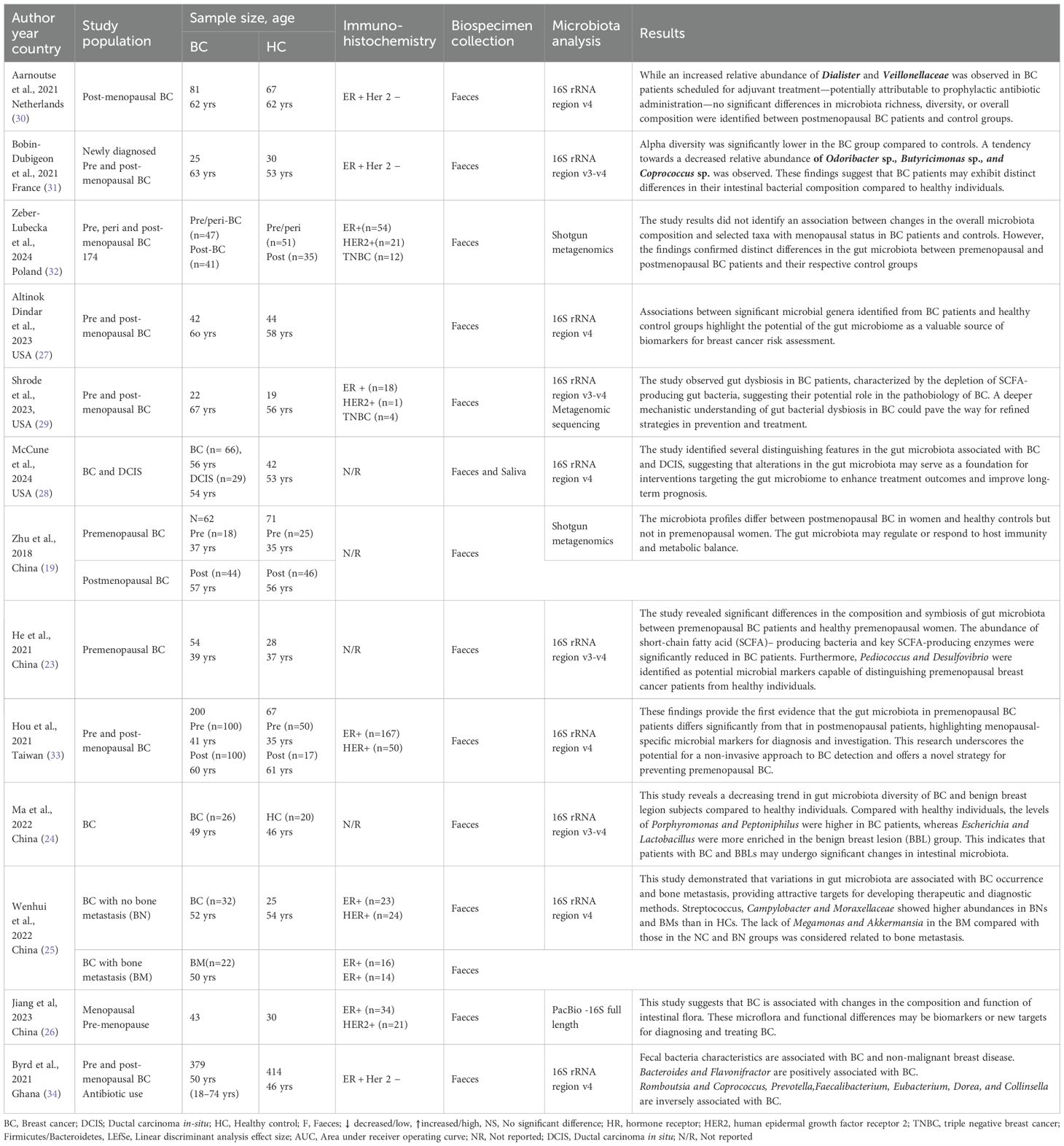

The studies were published from 2018 to 2024 and involved research from various regions, including China (n=5) (19, 23–26), the USA (n=3) (27–29), the Netherlands (n=1) (30), France (n=1) (31), Poland (n=1) (32), Taiwan (n=1) (33), and Ghana (n=1) (34). The study population includes premenopausal (n=2) (23), postmenopausal (n=1) (19), and mixed pre/post-menopausal (n=7) BC populations (33). Three studies did not describe the menopausal status (24, 25, 34). Specific populations were BC with/without bone metastasis (n=1) (25) while two studies not reported study populations were either pre- or post-menopausal BC. Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 379. Common participants’ immunohistochemistry was ER+ (n=10) followed by HER2+ (n=5), and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (n=2). Four studies did not report their participants’ immunohistochemistry data (24). Feces were collected and universally used across studies for microbiota analysis, while each study collected saliva (28) and blood (24) in addition to feces. Microbiota analysis was commonly performed with 16S rRNA sequencing (n=11) (23–25, 33, 34) while two were conducted with shotgun metagenomics (19, 29) and one study used PacBio (26) (Table 1).

3.2 Gut microbiota diversity and composition between the BC and HC

3.2.1 Diversity

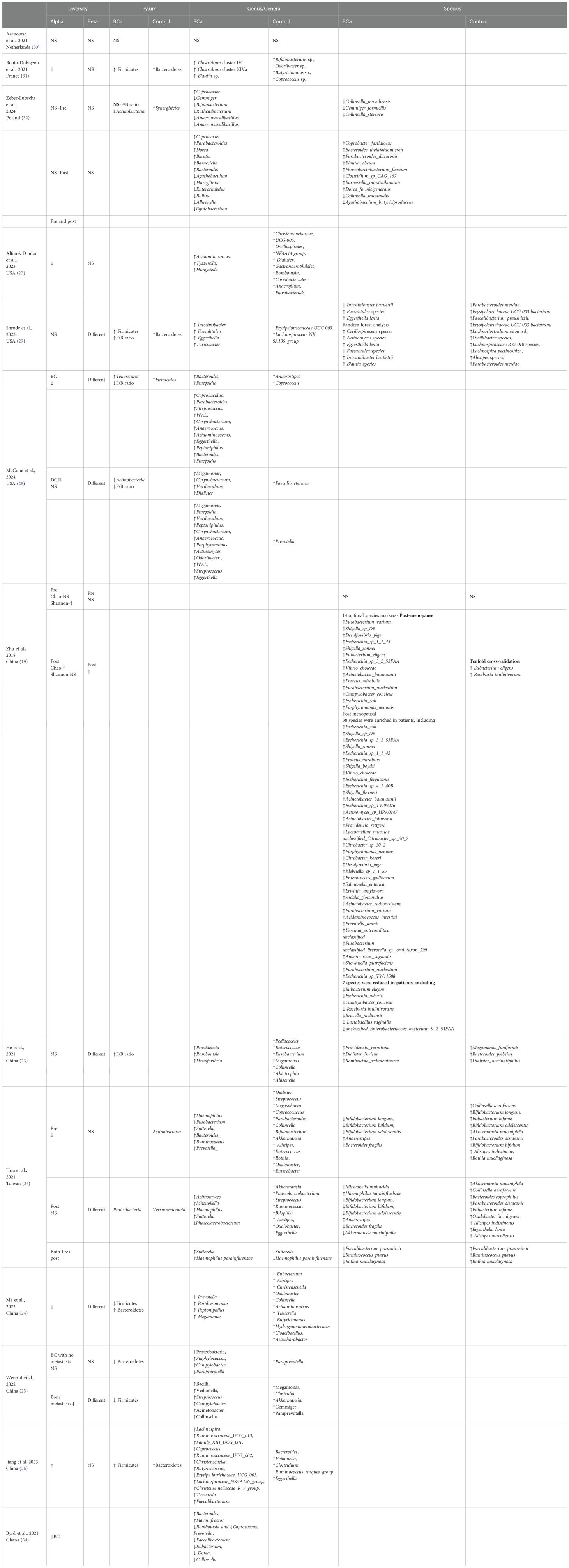

Of 13 studies, 7 reported lower alpha diversity in BC compared with HC, while 2 reported higher diversity and 4 reported no significant differences. Variability was partly attributed to menopausal status and diversity indices applied (Shannon v.s. Chao). For beta diversity, 7 studies found significant differences in overall microbial structure between BC and HC, whereas 4 reported no differences (Table 2).

3.3 The difference in gut microbiota composition between the BC and HC

3.3.1 Phylum level

At the phylum level, dysbiosis in BC was variably reported. Four studies (23, 26, 29, 31) observed an increased abundance of Firmicutes and higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratios in BC compared with controls, while three studies (24, 25, 28) reported decreased ratios. The remaining investigations found no significant or inconclusive differences. Actinobacteria findings were also inconsistent, with some studies reporting enrichment (28) and others depletion (32), underscoring methodological heterogeneity and population-specific effects.

3.3.2 Genus level

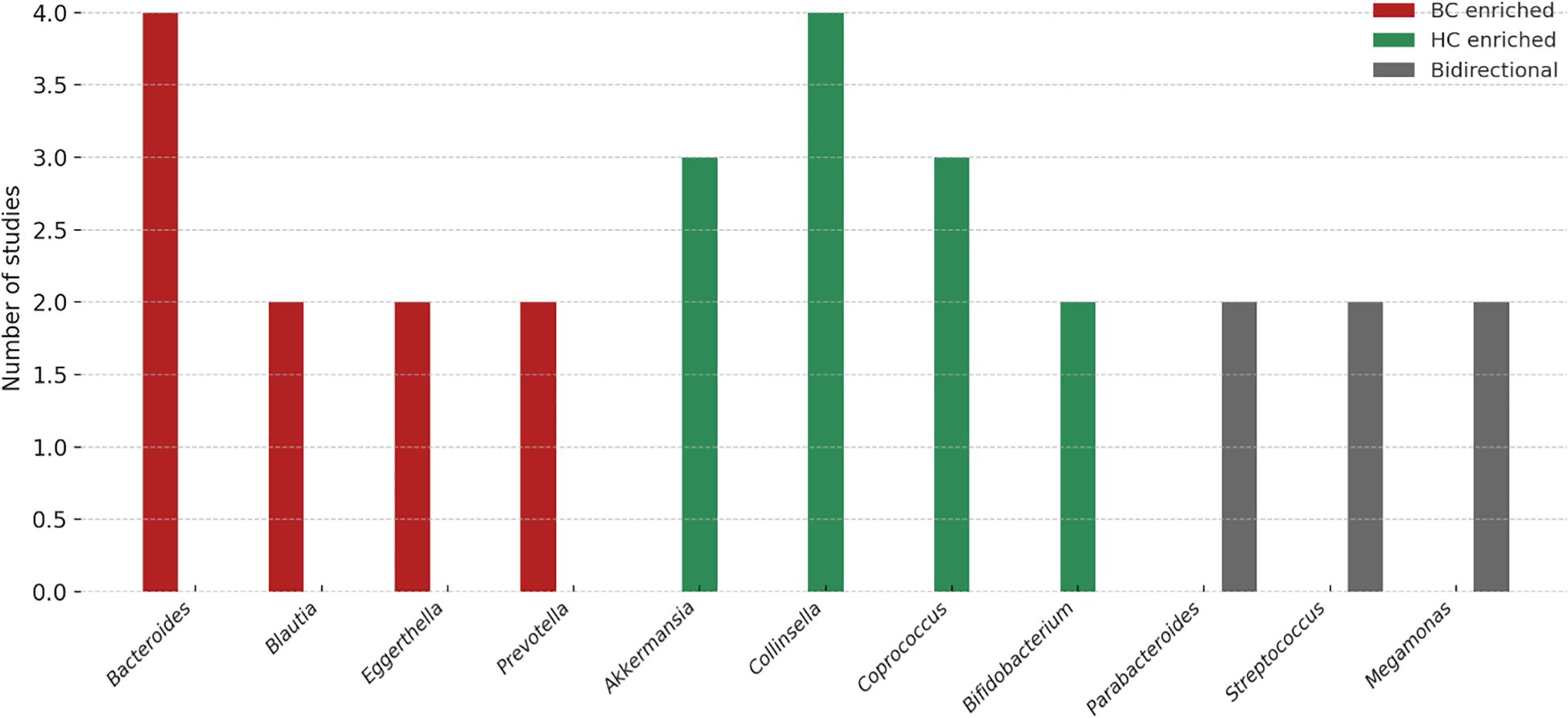

“At the genus level, several taxa showed consistent patterns across studies (Figure 1). Bacteroides was enriched in BC in four studies (28, 32–34), while Collinsella was reduced in four studies (23, 24, 33, 34), suggesting potential roles as risk- and protective-associated genera, respectively. Blautia (31, 32), Eggerthella (28, 29), Peptoniphilus (24, 28), Actinomyces (28, 33), and Tyzzerella (26, 27) were each reported as increased in BC in at least two independent cohorts. Conversely, Akkermansia (25, 33), Coprococcus (28, 31, 34), and occasionally Collinsella (24, 32, 33) were more abundant in healthy controls, suggesting protective associations. Several genera displayed bidirectional findings across populations: Megamonas (2↑, 2↓) (23, 24, 28, 33), Parabacteroides (2↑, 1↓) (28, 32, 33), and Streptococcus (2↑, 1↓) (25, 28, 33), indicating potential context-specific influences such as diet, menopausal status, or methodology (32).

Figure 1. Genus-level trends in gut microbiota associated with breast cancer. The figure summarizes the number of studies reporting enrichment of specific genera in breast cancer (BC; red), healthy controls (HC; green), or with bidirectional/inconsistent associations (gray). Bacteroides, Blautia, Eggerthella, and Prevotella were more frequently reported as enriched in BC, whereas Akkermansia, Collinsella, Coprococcus, and Bifidobacterium were commonly enriched in HC. Genera such as Parabacteroides, Streptococcus, and Megamonas showed bidirectional associations, indicating possible context-dependent effects. These variations highlight both reproducible microbial signals and methodological or population-related heterogeneity that warrant validation in larger, standardized cohorts.

3.3.3 Species level

“At the species level, some consistent patterns emerged. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was consistently depleted in BC patients in multiple studies (29, 33), supporting its proposed anti-inflammatory and protective role. By contrast, Eggerthella lenta (29, 33) and Parabacteroides distasonis (32, 33) showed bidirectional associations, with some studies reporting enrichment in BC and others showing depletion. Other species, such as Akkermansia muciniphila (25, 33) were more frequently reported as enriched in controls, suggesting a potentially protective influence.

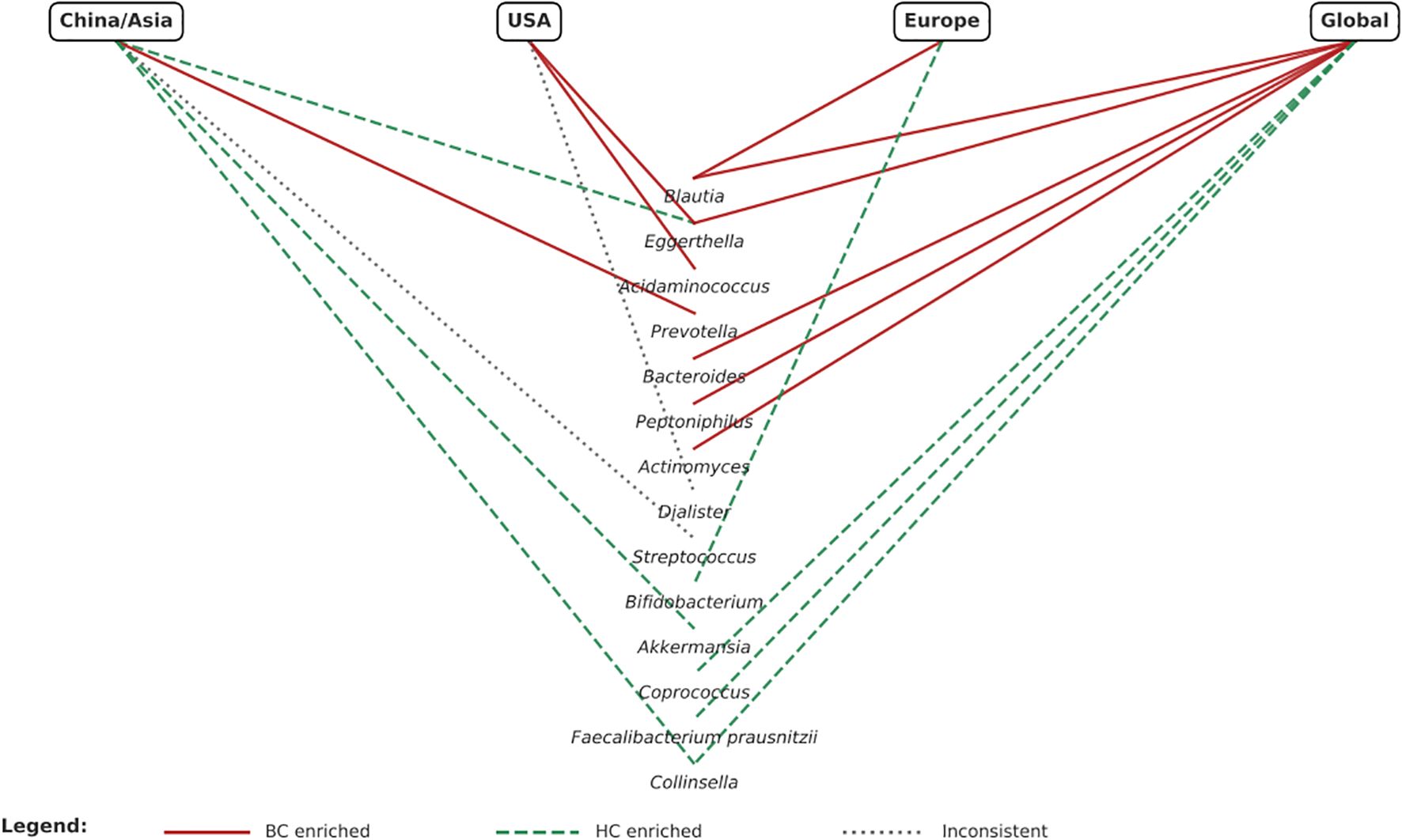

3.4 Geographical comparison of microbiota differences in BC Across China, USA, and Europe

Distinct geographical patterns in microbiota composition were observed (Figure 2). In Chinese cohorts, Prevotella was enriched in BC patients (24, 33), while Akkermansia (25, 33) and Collinsella (23, 24, 33) were generally depleted, suggesting possible protective roles. However, findings for Streptococcus were inconsistent, with one study showing an increase (25) and another a decrease (33). In the USA, Acidaminococcus (27, 28)and Eggerthella (28, 29) were consistently enriched in BC patients, whereas Dialister showed contradictory patterns (27, 28). European studies reported enrichment of Blautia (31, 32) in BC and depletion of Bifidobacterium (31, 32) compared with controls. When considered together, Asian cohorts tended to show enrichment of Prevotella and depletion of Akkermansia/Collinsella, whereas Western cohorts more often reported enrichment of Blautia, Acidaminococcus, and Eggerthella. These differences likely reflect not only biological variation but also dietary patterns (e.g., high-fiber traditional Asian diets vs higher fat Western diets), ethnicity-related host–microbiome interactions, antibiotic use, and methodological heterogeneity. These confounders must be critically accounted for before geographical differences can be translated into predictive or therapeutic applications.

4 Discussion

This review synthesizes emerging evidence on gut microbiota alterations in BC, with a particular emphasis on geographical variation across China, the USA, and Europe. To our knowledge, this is the first review to explicitly examine regional differences in gut microbiome cancer associations while incorporating species-level insights. Our findings highlight consistent signs of dysbiosis, identify potential candidate biomarkers, and point to opportunities for translational application, consistent with previous studies (35–37). At the same time, they underscore the methodological heterogeneity, modest evidence base, and predominance of cross-sectional designs that constrain definitive conclusions (19, 23, 34).

Overall, alpha diversity was reduced in BC patients in seven of the thirteen included studies (24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34), suggesting disrupted microbial homeostasis and a possible link to systemic inflammation (38, 39). However, two studies found increased alpha diversity (19, 26) and four reported no significant differences (23, 29, 30, 32). Beta diversity findings were similarly inconsistent; seven studies reported significant community-level shifts (19, 23–25, 28, 29, 33), whereas others observed no significant differences. These conflicting results likely reflect heterogeneity in study populations, particularly menopausal status, as well as methodological variability in sequencing approaches and the use of different diversity indices (40–42). Standardization of analytic pipelines will be essential to allow comparability across studies.

At the phylum level, four studies observed increased F/B ratios in BC patients (23, 26, 29, 31), consistent with pro-inflammatory states and altered energy harvesting (41, 43). In contrast, three studies reported no difference or reduced ratios (24, 25, 28), highlighting the influences of dietary and methodological influences (44, 45). These discrepancies highlight the limited utility of broad phylum-level metrics as reliable biomarkers. Such conflicting findings may reflect heterogeneity in host factors and study design, including dietary patterns (e.g., high-fiber vs. Western diets), sequencing approaches (16S rRNA vs. shotgun metagenomics), and menopausal status, which shapes the hormonal and metabolic milieu. Notably, compositional variability at the taxonomic level may converge functionally, through shared microbial outputs such as short-chain fatty acids or estrogen-modulating enzymes (10, 46). This functional redundancy suggests that integrative approaches combining compositional and metabolomic analyses are essential to elucidate the biological relevance of microbiome alterations in BC. More informative trends emerged at the genus level. Enrichment of Bacteroides, Blautia, Eggerthella and Parabacteroides in BC patients was observed across multiple studies (23, 24, 28, 29, 31, 34). These genera are linked to bile acid metabolism, pro-inflammatory signaling, and estrogen reactivation (47, 48). Eggerthella, in particular, is notable for β-glucuronidase activity, which may increase circulating bioactive estrogens and drive tumor progression (38, 49). Conversely, protective taxa, including Akkermansia, Collinsella, and Coprococcus were consistently depleted (19, 24, 25, 32–34). Of particular note, Akkermansia muciniphila was frequently reduced, consistent with its established role as a marker of mucosal health (50).

Species-level analysis, although limited to three metagenomic studies (23, 31, 32), yielded greater biomarker specificity. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a key butyrate producer with anti-inflammatory properties, was consistently reduced in BC patients (29, 33). By contrast, Eggerthella lenta and Parabacteroides distasonis showed inconsistent patterns of enrichment and depletion across cohorts (29, 31–33). These bidirectional results may reflect population-level dietary differences, strain-level functional variation, or technical inconsistencies (51, 52). Importantly, different taxonomic changes may converge on similar functional outcomes, such as reduced SCFA production or enhanced estrogen reactivation, suggesting that functional signatures may prove more reliable than taxonomy alone (53–55).

A major and novel contribution of this review is the comparative analysis of geographical variation. In the United States, enrichment of Acidaminococcus and Eggerthella was consistently reported (27–29), plausibly linked to high-fat, high-protein dietary patterns (45, 56). In Europe, Blautia enrichment was observed (31, 32), suggesting that fiber-driven microbial fermentation may influence breast (57, 58). In Chinese cohorts, enrichment of Prevotella and depletion of Akkermansia and Collinsella were common (19, 24, 25, 32, 33, 59, 60) reflecting carbohydrate-rich and fermented food dietary profiles (44, 45). Taken together, Asian cohorts showed Prevotella dominance and reduced SCFA-producing taxa, whereas Western cohorts were more likely to report enrichment of Blautia, Acidaminococcus, and Eggerthella. These patterns highlight how diet, ethnicity, and host factors interact with microbial ecology. However, translation into clinical application is premature. Regional differences complicate biomarker standardization but also create opportunities for precision nutrition and region-specific interventions (9, 61, 62). Contradictory findings, such as divergent F/B ratios or variable Collinsella levels, require careful appraisal. These discrepancies can be explained by methodological heterogeneity, including differences in DNA extraction, sequencing platform, and analytic pipelines. Clinical and demographic confounders, such as menopausal status, body mass index, antibiotic exposure, and treatment history, were often incompletely reported yet are known to shape microbiome composition. Importantly, taxonomic variability may still converge on functional similarity: reduced SCFA production, loss of barrier integrity, and enhanced estrogen metabolism are recurrent themes. Future work must therefore integrate metagenomics, metabolomics, and metatranscriptomics to link compositional changes with mechanistic outputs (8).

The potential of the gut microbiome as a predictive biomarker in BC should be viewed as preliminary. Current evidence is largely cross-sectional and insufficient to establish causality. Nevertheless, recurring signals, such as depletion of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia muciniphila, provide biologically plausible candidate biomarkers that merit validation (42, 50, 63). Integration with established predictors, including circulating estrogen, inflammatory markers, hormone receptor status, and genomic risk scores, could yield multi-modal models with greater predictive power (64, 65). In practice, stool-based microbiome profiling could emerge as a low-cost, non-invasive adjunct, but clinical application will require reproducible assays, validated thresholds, and demonstration of incremental benefits (9, 49). Microbiota-based interventions represent a promising but as yet untested avenue in BC (63, 66). Evidence from other cancers indicates that dietary fiber, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation can modulate therapeutic response (62, 66, 67). In breast cancer, dietary modification, particularly fiber enrichment or polyphenol supplementation, may support protective taxa such as Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia. Probiotic and prebiotic interventions targeting estrogen metabolism or SCFA production are theoretically attractive but require robust testing in controlled trials (50, 63, 66).

This review has several strengths, including its structured literature search, inclusion of species-level analyses, and integration of geographical perspectives, which have been largely overlooked in prior work. However, important limitations must be acknowledged. Only 13 studies met eligibility criteria, reflecting the early stage of this field. Most were small, cross-sectional studies relying on 16S rRNA sequencing, which restricts taxonomic resolution. Only three employed metagenomic approaches, which are needed for functional insight. Menopausal status, body mass index, and antibiotic use were inconsistently reported, limiting comparability. Restriction to English-language publications may have introduced selection bias. A formal risk-of-bias assessment was not conducted, consistent with the Mini Review format, but methodological variability was qualitatively addressed.

Future research should therefore prioritize prospective designs to establish temporal and causal relationships between dysbiosis and breast cancer (68). Microbiome signatures should be integrated with established biomarkers in multivariable models to test whether they improve prediction. Region-specific interventions should be trialed, recognizing that microbiome–diet interactions are culturally and geographically contingent (13). Functional profiling must be incorporated to reconcile taxonomic heterogeneity and clarify biological plausibility. Harmonization of methods for sampling, sequencing, and analysis will be critical to reproducibility (69). Finally, international collaborations are needed to validate microbial predictors across diverse populations, including underrepresented regions such as Africa and South America, ensuring equitable global translation (61, 67, 70).

In conclusion, while the gut microbiome cannot yet be regarded as an established predictive biomarker for BC, the trajectory of current research suggests considerable promise. Consistent signals at genus and species levels, functional links to estrogen metabolism and inflammation, and region-specific variation provide a biologically credible foundation for further study. Translation into clinical practice will depend on large-scale, longitudinal, standardized studies capable of establishing causality and reproducibility. If achieved, microbiome-informed approaches may ultimately contribute to precision oncology by enhancing risk stratification, guiding dietary counselling, and supporting the development of microbiome-targeted interventions.

Author contributions

BO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SCa: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MMr: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. FB: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NP: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SCl: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. AG: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. AM: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CD: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. KM: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SB-H: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TE: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MMl: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MB: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:229–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

2. Burguin A, Diorio C, and Durocher F. Breast cancer treatments: updates and new challenges. J Pers Med. (2021) 11. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080808

3. Morgan E, O’Neill C, Shah R, Langselius O, Su Y, Frick C, et al. Metastatic recurrence in women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. (2024) 26:171. doi: 10.1186/s13058-024-01881-y

4. O'Shaughnessy J. Extending survival with chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. (2005) 10 Suppl 3:20–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-20

5. Toumazi D, El Daccache S, and Constantinou C. An unexpected link: The role of mammary and gut microbiota on breast cancer development and management (Review). Oncol Rep. (2021) 45. doi: 10.3892/or.2021.8031

6. Nandi D, Parida S, and Sharma D. The gut microbiota in breast cancer development and treatment: The good, the bad, and the useful! Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2221452. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2221452

7. Zhao L-Y, Mei J-X, Yu G, Lei L, Zhang W-H, Liu K, et al. Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2023) 8:201. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01406-7

8. Aarnoutse R, Ziemons J, Hillege LE, de Vos-Geelen J, de Boer M, Bisschop SMP, et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota in postmenopausal oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients treated with (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy. NPJ Breast Cancer. (2022) 8:89. doi: 10.1038/s41523-022-00455-5

9. Arnone AA, Ansley K, Heeke AL, Howard-McNatt M, and Cook KL. Gut microbiota interact with breast cancer therapeutics to modulate efficacy. EMBO Mol Med. (2025) 17:219–34. doi: 10.1038/s44321-024-00185-0

10. Parida S and Sharma D. The microbiome-estrogen connection and breast cancer risk. Cells. (2019) 8. doi: 10.3390/cells8121642

11. Guo Y, Dong W, Sun D, Zhao X, Huang Z, Liu C, et al. Bacterial metabolites: Effects on the development of breast cancer and therapeutic efficacy. Oncol Lett. (2025) 29:210. doi: 10.3892/ol.2025.14956

12. Feng ZP, Xin HY, Zhang ZW, Liu CG, Yang Z, You H, et al. Gut microbiota homeostasis restoration may become a novel therapy for breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. (2021) 39:871–8. doi: 10.1007/s10637-021-01063-z

13. Jiang Y and Li Y. Nutrition intervention and microbiome modulation in the management of breast cancer. Nutrients. (2024) 16. doi: 10.3390/nu16162644

14. Gopalakrishnan V, Helmink BA, Spencer CN, Reuben A, and Wargo JA. The influence of the gut microbiome on cancer, immunity, and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. (2018) 33:570–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.015

15. Xie M, Li X, Lau HC-H, and Yu J. The gut microbiota in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol. (2025) 22:1012–31. doi: 10.1038/s41423-025-01326-2

16. Luan B, Ge F, Lu X, Li Z, Zhang H, Wu J, et al. Changes in the fecal microbiota of breast cancer patients based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Oncol. (2024) 26:1480–96. doi: 10.1007/s12094-023-03373-5

17. Huang M, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Yu X, Luo S, Peng X, et al. Gut microbiota reshapes the TNBC immune microenvironment: Emerging immunotherapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Res. (2025) 215:107726. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107726

18. Hong W, Huang G, Wang D, Xu Y, Qiu J, Pei B, et al. Gut microbiome causal impacts on the prognosis of breast cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Genomics. (2023) 24:497. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09608-7

19. Zhu J, Liao M, Yao Z, Liang W, Li Q, Liu J, et al. Breast cancer in postmenopausal women is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Microbiome. (2018) 6:136. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0515-3

20. Yende AS and Sharma D. Obesity, dysbiosis and inflammation: interactions that modulate the efficacy of immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1444589. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1444589

21. Lee KA, Luong MK, Shaw H, Nathan P, Bataille V, and Spector TD. The gut microbiome: what the oncologist ought to know. Br J Cancer. (2021) 125:1197–209. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01467-x

22. Amaro-da-Cruz A, Rubio-Tomás T, and Álvarez-Mercado AI. Specific microbiome patterns and their association with breast cancer: the intestinal microbiota as a potential biomarker and therapeutic strategy. Clin Transl Oncol. (2025) 27:15–41. doi: 10.1007/s12094-024-03554-w

23. He C, Liu Y, Ye S, Yin S, and Gu J. Changes of intestinal microflora of breast cancer in premenopausal women. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2021) 40:503–13. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-04036-x

24. Ma J, Sun L, Liu Y, Ren H, Shen Y, Bi F, et al. Alter between gut bacteria and blood metabolites and the anti-tumor effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in breast cancer. BMC Microbiol. (2020) 20:82. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01739-1

25. Wenhui Y, Zhongyu X, Kai C, Zhaopeng C, Jinteng L, Mengjun M, et al. Variations in the gut microbiota in breast cancer occurrence and bone metastasis. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:894283. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.894283

26. Jiang Y, Gong W, Xian Z, Xu W, Hu J, Ma Z, et al. 16S full-length gene sequencing analysis of intestinal flora in breast cancer patients in Hainan Province. Mol Cell Probes. (2023) 71:101927. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2023.101927

27. Altinok Dindar D, Chun B, Palma A, Cheney J, Krieger M, Kasschau K, et al. Association between gut microbiota and breast cancer: diet as a potential modulating factor. Nutrients. (2023) 15. doi: 10.3390/nu15214628

28. McCune E, Sharma A, Johnson B, O'Meara T, Theiner S, Campos M, et al. Gut and oral microbial compositional differences in women with breast cancer, women with ductal carcinoma in situ, and healthy women. mSystems. (2024) 9:e0123724. doi: 10.1128/msystems.01237-24

29. Shrode RL, Knobbe JE, Cady N, Yadav M, Hoang J, Cherwin C, et al. Breast cancer patients from the Midwest region of the United States have reduced levels of short-chain fatty acid-producing gut bacteria. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:526. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-27436-3

30. Aarnoutse R, Hillege LE, Ziemons J, De Vos-Geelen J, de Boer M, Aerts E, et al. Intestinal microbiota in postmenopausal breast cancer patients and controls. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13. doi: 10.3390/cancers13246200

31. Bobin-Dubigeon C, Luu HT, Leuillet S, Lavergne SN, Carton T, Le Vacon F, et al. Faecal microbiota composition varies between patients with breast cancer and healthy women: A comparative case-control study. Nutrients. (2021) 13. doi: 10.3390/nu13082705

32. Zeber-Lubecka N, Kulecka M, Jagiełło-Gruszfeld A, Dąbrowska M, Kluska A, Piątkowska M, et al. Breast cancer but not the menopausal status is associated with small changes of the gut microbiota. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1279132. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1279132

33. Hou MF, Ou-Yang F, Li CL, Chen FM, Chuang CH, Kan JY, et al. Comprehensive profiles and diagnostic value of menopausal-specific gut microbiota in premenopausal breast cancer. Exp Mol Med. (2021) 53:1636–46. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00686-9

34. Byrd DA, Vogtmann E, Wu Z, Han Y, Wan Y, Clegg-Lamptey JN, et al. Associations of fecal microbial profiles with breast cancer and nonmalignant breast disease in the Ghana Breast Health Study. Int J Cancer. (2021) 148:2712–23. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33473

35. Xuan C, Shamonki JM, Chung A, Dinome ML, Chung M, Sieling PA, et al. Microbial dysbiosis is associated with human breast cancer. PloS One. (2014) 9:e83744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083744

36. Esposito MV, Fosso B, Nunziato M, Casaburi G, D'Argenio V, Calabrese A, et al. Microbiome composition indicate dysbiosis and lower richness in tumor breast tissues compared to healthy adjacent paired tissue, within the same women. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:30. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09074-y

37. Schettini F, Gattazzo F, Nucera S, Garcia ER, López-Aladid R, Morelli L, et al. Navigating the complex relationship between human gut microbiota and breast cancer: Physiopathological, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Cancer Treat Rev. (2024) 130:102816. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102816

38. Laborda-Illanes A, Sanchez-Alcoholado L, Dominguez-Recio ME, Jimenez-Rodriguez B, Lavado R, Comino-Méndez I, et al. Breast and gut microbiota action mechanisms in breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Cancers. (2020) 12:2465. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092465

39. Chen J, Douglass J, Prasath V, Neace M, Atrchian S, Manjili MH, et al. The microbiome and breast cancer: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2019) 178:493–6. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05407-5

40. An J, Yang J, Kwon H, Lim W, Kim Y-K, and Moon B-I. Prediction of breast cancer using blood microbiome and identification of foods for breast cancer prevention. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:5110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32227-x

41. Garrett WS. The gut microbiota and colon cancer. Science. (2019) 364:1133–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2367

42. Lynch SV and Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:2369–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266

43. Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, and Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. (2006) 444:1027–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05414

44. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. (2014) 505:559–63. doi: 10.1038/nature12820

45. O'Keefe SJ. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2016) 13:691–706. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.165

46. Mirzaei R, Afaghi A, Babakhani S, Sohrabi MR, Hosseini-Fard SR, Babolhavaeji K, et al. Role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in cancer development and prevention. BioMed Pharmacother. (2021) 139:111619. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111619

47. Abdelqader EM, Mahmoud WS, Gebreel HM, Kamel MM, and Abu-Elghait M. Correlation between gut microbiota dysbiosis, metabolic syndrome and breast cancer. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:6652. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-89801-8

48. Mima K, Hamada T, Inamura K, Baba H, Ugai T, and Ogino S. The microbiome and rise of early-onset cancers: knowledge gaps and research opportunities. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2269623. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2269623

49. Ruo SW, Alkayyali T, Win M, Tara A, Joseph C, Kannan A, et al. Role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in breast cancer and novel approaches in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. (2021) 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17472

50. Cani PD and de Vos WM. Next-generation beneficial microbes: the case of akkermansia muciniphila. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:1765. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01765

51. Zhernakova A, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, Tigchelaar EF, Schirmer M, Vatanen T, et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science. (2016) 352:565–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3369

52. Sonnenburg ED and Sonnenburg JL. The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2019) 17:383–90. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0191-8

53. Thaiss CA, Zmora N, Levy M, and Elinav E. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. (2016) 535:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nature18847

54. Bai X, Sun Y, Li Y, Li M, Cao Z, Huang Z, et al. Landscape of the gut archaeome in association with geography, ethnicity, urbanization, and diet in the Chinese population. Microbiome. (2022) 10:147. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01335-7

55. Gupta VK, Paul S, and Dutta C. Geography, ethnicity or subsistence-specific variations in human microbiome composition and diversity. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162

56. Zitvogel L, Ma Y, Raoult D, Kroemer G, and Gajewski TF. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: Diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science. (2018) 359:1366–70. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6918

57. Chen S, Chen Y, Ma S, Zheng R, Zhao P, Zhang L, et al. Dietary fibre intake and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:80980–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13140

58. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. (2012) 486:222–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11053

59. Lu J, Zhang L, Zhai Q, Zhao J, Zhang H, Lee Y-K, et al. Chinese gut microbiota and its associations with staple food type, ethnicity, and urbanization. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. (2021) 7:71. doi: 10.1038/s41522-021-00245-0

60. Xie Y, Xu S, Xi Y, Li Z, Zuo E, Xing K, et al. Global meta-analysis reveals the drivers of gut microbiome variation across vertebrates. iMetaOmics. (2024) 1:e35. doi: 10.1002/imo2.35

61. Zitvogel L, Derosa L, Routy B, Loibl S, Heinzerling L, de Vries IJM, et al. Impact of the ONCOBIOME network in cancer microbiome research. Nat Med. (2025) 31:1085–98. doi: 10.1038/s41591-025-03608-8

62. Roy S and Trinchieri G. Microbiota: a key orchestrator of cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2017) 17:271–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.13

63. Di Modica M, Gargari G, Regondi V, Bonizzi A, Arioli S, Belmonte B, et al. Gut microbiota condition the therapeutic efficacy of trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:2195–206. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1659

64. Feng T-Y, Azar FN, Dreger SA, Rosean CB, McGinty MT, Putelo AM, et al. Reciprocal interactions between the gut microbiome and mammary tissue mast cells promote metastatic dissemination of HR+ breast tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. (2022) 10:1309–25. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-1120

65. Chapadgaonkar SS, Bajpai SS, and Godbole MS. Gut microbiome influences incidence and outcomes of breast cancer by regulating levels and activity of steroid hormones in women. Cancer Rep. (2023) 6:e1847. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1847

66. Fernandes MR, Aggarwal P, Costa RGF, Cole AM, and Trinchieri G. Targeting the gut microbiota for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2022) 22:703–22. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00513-x

67. Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. (2018) 359:91–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706

68. Bernardo G, Le Noci V, Di Modica M, Montanari E, Triulzi T, Pupa SM, et al. The emerging role of the microbiota in breast cancer progression. Cells. (2023) 12:1945. doi: 10.3390/cells12151945

69. Cullin N, Azevedo Antunes C, Straussman R, Stein-Thoeringer CK, and Elinav E. Microbiome and cancer. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1317–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.08.006

Keywords: breast cancer, gut microbiome, predictive biomarker, geographical variation, estrogen metabolism, precision oncology

Citation: Oh B, Lamoury G, Carroll S, Morgia M, Boyle F, Pavlakis N, Clarke S, Guminski A, Menzies A, Diakos C, Moore K, Baron-Hay S, Eade T, Molloy M and Back M (2025) The gut microbiome as a potential predictive biomarker for breast cancer: emerging association and geographic differences. Front. Oncol. 15:1666830. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1666830

Received: 15 July 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 19 September 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Purvi Purohit, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Jodhpur, IndiaReviewed by:

Dipayan Roy, University of Allahabad, IndiaCopyright © 2025 Oh, Lamoury, Carroll, Morgia, Boyle, Pavlakis, Clarke, Guminski, Menzies, Diakos, Moore, Baron-Hay, Eade, Molloy and Back. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Byeongsang Oh, Ynllb25nLm9oQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Byeongsang Oh

Byeongsang Oh Gillian Lamoury1,2,3,4

Gillian Lamoury1,2,3,4 Nick Pavlakis

Nick Pavlakis Stephen Clarke

Stephen Clarke Alexander Guminski

Alexander Guminski Mark Molloy

Mark Molloy