Abstract

Background:

Female adnexal tumor of Wolffian origin (FATWO) is an exceedingly rare gynecologic neoplasm characterized by nonspecific clinical manifestations and diagnostic challenges. This article presents a case of an incidentally discovered FATWO in a postmenopausal woman, with a literature review.

Case presentation:

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman was found to have a 5.2-cm solid mass in the left adnexa during routine examination. Ultrasonography revealed a well-circumscribed lesion with detectable blood flow, while computed tomography (CT) scan suggested an ovarian origin. Tumor markers were within normal limits, and the patient remained asymptomatic. Single-port laparoscopic exploration identified a 5-cm solid ovarian nodule with an intact capsule. Intraoperative frozen section analysis suggested FATWO, prompting subsequent total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. No adjuvant therapy was administered postoperatively, and the patient showed no evidence of disease progression during 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion:

FATWO exhibits a potentially malignant biological behavior. For postmenopausal patients, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended. Postoperative management should be individualized. Current evidence regarding treatment strategies for reproductive-age patients remains limited, warranting further investigation to optimize clinical decision-making.

Introduction

The Wolffian tumor, also known as the female adnexal tumor of Wolffian origin (FATWO), is a rare and distinctive epithelial neoplasm originating from the Wolffian duct. This pathology was first described by Kariminejad and Scully in 1973 (1). The majority of FATWOs are located in the broad ligament or the mid-portion of the fallopian tube, with only 20% found in the ovarian hilum near the rete ovarii. Patients’ ages vary from 15 to 87 years. Lower abdominal pain/bloating is the most common sign, and a pelvic mass or abnormal genital bleeding is discovered incidentally (2, 3). The rarity of FATWO and its nonspecific clinical presentation and heterogeneous histopathological features make its diagnosis challenging. While the majority of FATWOs exhibit a low malignant potential, aggressive behavior—including recurrence and metastasis—has been reported in rare cases (1, 4). Currently, there is no standardized treatment protocol for FATWO. Here, we present a case of an incidentally discovered Wolffian tumor in a postmenopausal woman during surgery. This report aimed to draw attention to this disease and to explore the clinical management of Wolffian tumors and discuss therapeutic options, contributing to the limited evidence on the management of this rare entity.

Case presentation

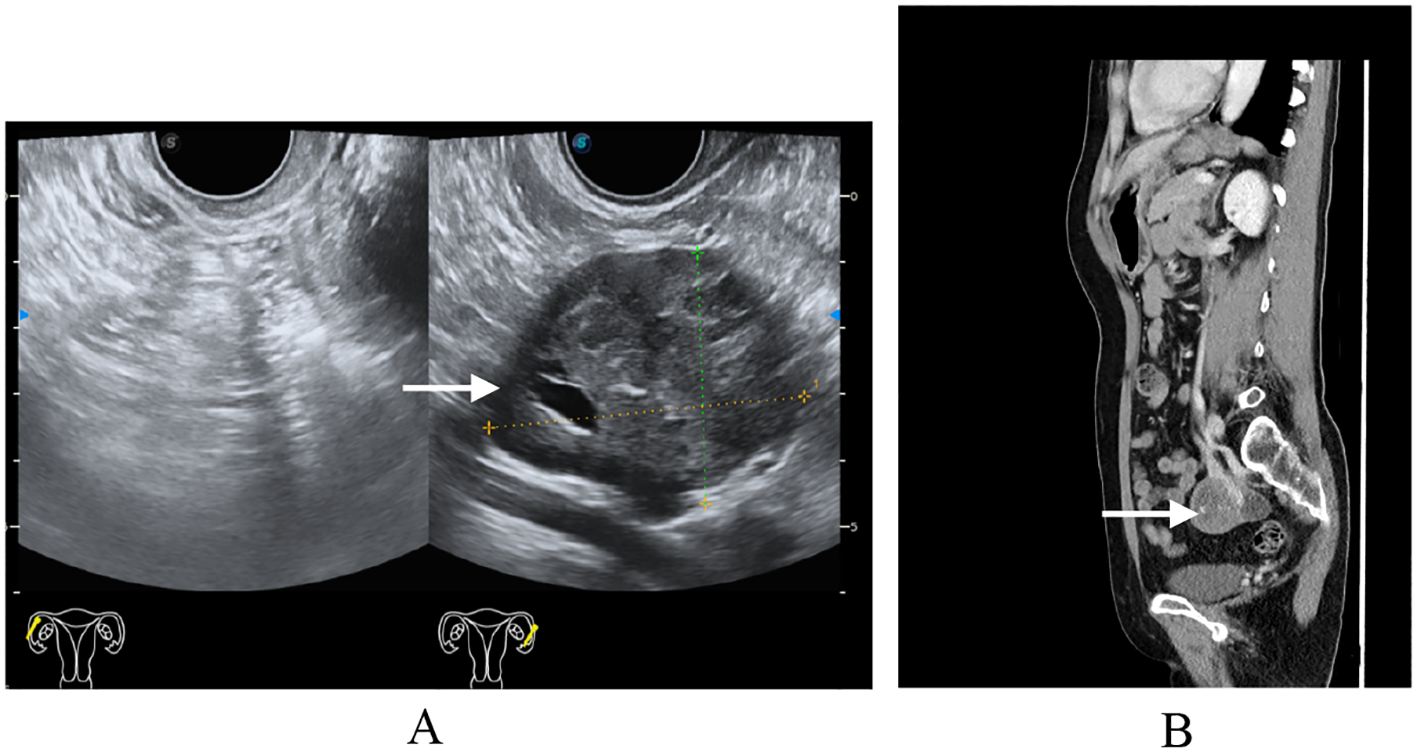

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman, gravida 3 para 1 (G3P1) with a history of one full-term vaginal delivery and two remote-induced abortions (over 20 years ago), was admitted to our hospital following a routine physical examination in June 2024. She had no significant medical or surgical comorbidities. The patient was asymptomatic, with no abdominal discomfort, abnormal vaginal bleeding, or urinary or gastrointestinal symptoms. Her previous menstrual history was unremarkable. A comprehensive gynecological examination was conducted. Speculum examination revealed no vaginal wall lesions and a normal-appearing cervix (cervical cytology was obtained, with the results within normal limits). Bimanual examination palpated a well-defined, mobile, non-tender, approximately 5-cm mass in the left adnexa. Transvaginal ultrasonography confirmed a corresponding 5.2-cm solid left adnexal mass, demonstrating well-demarcated but irregular margins, heterogeneous echogenicity, and punctate vascular signals on color Doppler. To further characterize the lesion, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which identified a solid left adnexal mass with heterogeneous enhancement and no evidence of lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). The imaging findings were most consistent with an ovarian neoplasm. The tumor markers were within normal limits, including CA-125 (16.7 U/ml; normal range, <35 U/ml), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (2.1 ng/ml; normal range, <8.1 ng/ml), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (0.9 ng/ml; normal range, <2.5 ng/ml for non-smokers). Based on the comprehensive evaluation, including the physical examination, imaging features (well-demarcated borders and absence of ascites or lymphadenopathy), and notably negative tumor markers, the mass was preoperatively assessed as highly likely to be benign. The leading differential diagnoses included an ovarian fibroma/thecoma or a pedunculated uterine leiomyoma. The patient was subsequently scheduled for surgical intervention for both definitive diagnosis and treatment. After the preoperative evaluation and signing of informed consent, the patient received a single-port transumbilical laparoscopic exploration. The surgery confirmed an atrophic uterus, and the left ovary was enlarged, containing a 5-cm × 4-cm × 4-cm solid nodular tumor. The left fallopian tube and the right adnexa were unremarkable. No ascites or peritoneal lesions were detected. Frozen section pathology revealed tumor cells arranged in tubular with solid patterns, suggesting FATWO, although sex cord–stromal tumors remained in the differential diagnosis. After negotiating with the patient’s relatives during the operation, a subsequent total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged home 4 days later.

Figure 1

Preoperative imaging findings. (A) Transvaginal ultrasound: single-chamber anechoic cystic lesion, 5 cm in diameter, arising from the left adnexa; wall thin and smooth, no internal septa or papillary projections, color Doppler shows absent vascularity. (B) Computed tomography same-level non-contrast CT reveals a well-circumscribed, oval low-density cystic mass in the left adnexal region, homogeneous attenuation, no enhancement, adjacent structures mildly displaced without mass effect.

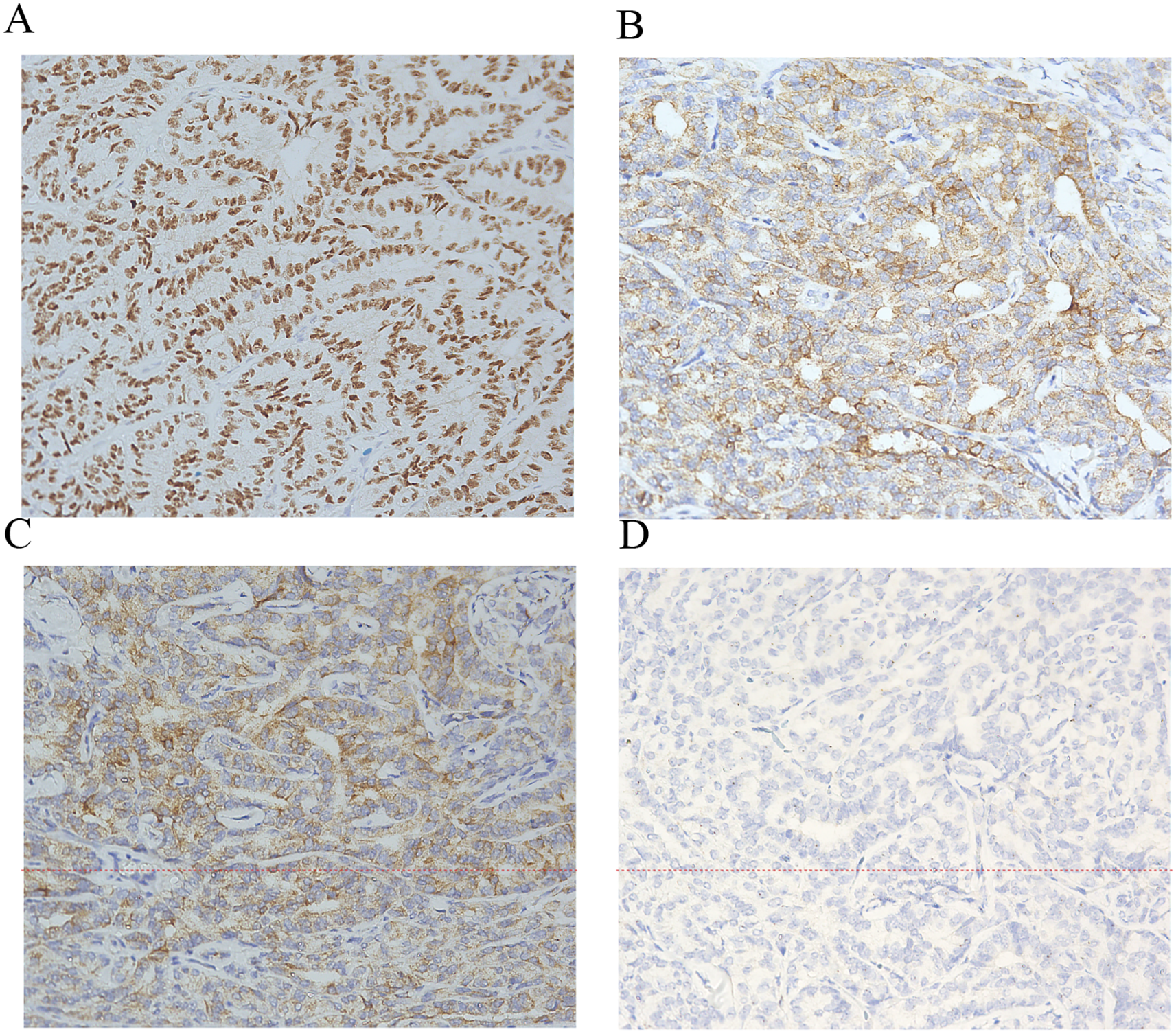

Definitive pathology confirmed Wolffian tumor (ICD code: 9110/1), which measured 5.2 cm in maximal diameter. The tumor was confined to the left ovarian parenchyma without capsular invasion, with negative margins, and without involvement of adjacent structures. The resected tumor specimen was thoroughly examined. Macroscopically, the tumor appeared well circumscribed, with a solid and partially cystic cut surface. Microscopically, the tumor exhibited a mixed growth pattern, including solid, tubular, and sieve-like structures. The tumor cells were uniform and bland, with scant cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei. Focal areas showed hyalinized vascular stroma and intraluminal eosinophilic secretions. Immunohistochemistry showed the following: FOXL2 (+++, strongly positive), calretinin (++), SF-1 (++), α-inhibin (++), vimentin (++), CD10 (focal luminal positivity), and AR (+). On the other hand, ER, PR, EMA, GATA3, and TTF-1 were negative. The Ki-67 proliferation index was approximately 1% (Figure 2), indicating low cellular activity. These features supported diagnosis as a rare adnexal tumor of borderline malignant potential. Multidisciplinary consensus recommended no adjuvant therapy. A rigorous surveillance protocol was suggested, including quarterly gynecological exams, tumor marker assessments, and imaging studies. At the 12-month follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic with normal tumor markers and no evidence of recurrence on pelvic ultrasound/CT, achieving 1-year progression-free survival (PFS). Long-term monitoring continues.

Figure 2

Immunohistochemistry of Wolffian tumor. Immunohistochemical stains (×200) for FOXL2+ (A) α-inhibin+ (B) calretinin+ (C) and epithelial membrane antigen− (D).

Discussion

FATWO exhibits a unique embryological origin. During female reproductive system development, the Wolffian duct guides caudal growth of the Müllerian duct, ultimately fusing with the urogenital sinus to form the lower vagina (5, 6). Under the influence of the anti-Müllerian hormone, the Wolffian duct remnants persist in structures including the broad ligament, the lateral cervical wall, and the vaginal fornix, with FATWO arising from these vestigial tissues (7). This explains the predominant localization of FATWO in the upper Wolffian system derivatives (e.g., the broad ligament), whereas mesonephric adenocarcinomas typically occur in the lower portions. The imaging characteristics of FATWO are nonspecific, which often leads to a broad differential diagnosis preoperatively. In our case, ultrasonography and CT revealed a solid, well-demarcated adnexal mass, findings that are consistent with the limited reports available. The seminal work by Matsuki et al. in 1999 first detailed the MRI features of this entity, providing valuable insights for radiologists. In their report, the tumor appeared isointense to the skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images and demonstrated heterogeneous, slightly high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, often with areas of cystic degeneration. Following contrast administration, the solid components typically showed homogeneous enhancement (8). While our patient did not undergo MRI, the solid nature and well-defined borders observed on CT align with the fundamental MRI description of a solid mass. The key radiological challenge, as highlighted by Matsuki et al., is how to differentiate FATWO from the more common entities such as a subserosal leiomyoma or an ovarian stromal tumor (e.g., thecoma or fibroma). The presence of a separate, normal ipsilateral ovary on imaging can be a crucial clue to suggest an extra-ovarian origin, such as a FATWO arising from the broad ligament. Ultimately, however, the overlapping imaging features underscore the necessity of a histopathological examination for a definitive diagnosis, which was performed in our case.

The principal differential diagnoses for FATWO include a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor, and a granulosa cell tumor. Endometrioid adenocarcinomas frequently originate from fallopian tubes and demonstrate a more pronounced nuclear atypia and mitotic activity (1). Although Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors share morphological similarities, FATWO lacks endocrine manifestations and may exhibit characteristic cribriform patterns (9). Granulosa cell tumors are identified by their pathognomonic nuclear grooves, although this feature is not entirely specific (10). Distinguishing Wolffian tumors from sex cord–stromal tumors reveals particular challenges, as both may express calretinin, inhibin, WT1, and CD10 while typically remaining negative for EMA and PAX8 (11, 12). Sex cord–stromal tumors typically demonstrate diffuse inhibin positivity, whereas female adnexal tumors of Wolffian origin generally show focal expression patterns. FATWO displays considerable morphological heterogeneity (solid, tubular, and cribriform patterns), necessitating combined morphological and immunohistochemical evaluation due to its nonspecific features (4, 13). The immunohistochemical profile of our case presented with strongly positive FOXL2 (+++), calretinin (++), SF-1 (++), α-inhibin (++), and vimentin (++), focal luminal CD10 positivity, and AR (+), but with negative ER, PR, EMA, GATA3, and TTF-1, aligning with the established FATWO characteristics in the literature (13, 14). This immunophenotype, in particular the strong positivity of FOXL2 contrasting with the variable expression of sex cord–stromal tumors, provides critical diagnostic support for FATWO. The dual negativity of GATA3 and TTF-1 effectively excludes metastatic carcinomas of breast, urothelial, or thyroid origin, while the hormonal receptor negativity (ER/PR) further differentiates it from hormone-responsive neoplasms. The low Ki-67 index (1%) observed correlates with the typically indolent biological behavior of FATWO.

Heatley et al. proposed, based on a UK literature review, that Wolffian tumors cannot be entirely regarded as benign lesions (15). Furthermore, there are documented cases of contralateral adnexal and pelvic–abdominal metastases occurring 2 years after fertility-sparing surgery for Wolffian tumors (16). The current literature primarily focuses on postmenopausal patients (with favorable prognosis following total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), while the therapeutic dilemma for younger patients remains unresolved. While infracolic omentectomy, peritoneal washings, and lymph node sampling are standard for epithelial ovarian carcinomas, their role in FATWO remains undefined. Given the rarity of the tumor and its generally indolent behavior, staging procedures are typically reserved for cases with overt malignant features (e.g., tumor rupture, gross metastases, or high-grade morphology). In our case, the tumor was intact and confined to the adnexa without suspicious extra-ovarian findings, justifying a conservative approach. Nonetheless, future studies should evaluate whether systematic staging impacts the survival or recurrence risk of patients with adverse pathological features. It must be emphasized that there is a notable lack of reliable evidence with regard to the application of fertility-preserving treatments in premenopausal patients and their long-term efficacy. Although FATWO typically exhibits an indolent clinical course, its potential for aggressive progression necessitates the establishment of evidence-based therapeutic strategies.

Our targeted literature review of FATWO cases from the past decade (Table 1) revealed significant heterogeneity in the treatment approaches—ranging from surgery alone to multimodal therapy. Of particular note, while isolated case reports have described transient remission with adjuvant therapies (including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal agents, and targeted drugs), the definitive role of these interventions in malignant FATWO remains unestablished due to the absence of controlled clinical studies.

Table 1

| Author (year) | Age (years) | Child-bearing history | Clinical presentation | Primary site and tumor size (diameter: cm) | Tumor nature | Treatment category | Follow-up and outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shabnam Mashhadi (2024) (16) | 35 | G1P1 | None | Left adnexal: 10 | Malignant behavior | First: Ovarian cystectomy For recurrence: TH + BSO+ six cycles of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC5) chemotherapy |

Recurrence at 2-year follow-up | |

| Shuhui Hong (2018) (17) | 50 | G1P1 | Lower abdominal pain, constipation, and increased urinary urgency | Left adnexal: 9 Right adnexal: 5 |

Malignant behavior | Surgery: TH + BSO | NR | |

| Qiuhe Chen (2021) (18) | 75 | G3P2 | None | Right pelvis: 5 | NR | First: BSO Second: TH and systemic chemotherapy: six cycles of docetaxel (80 mg/m2) and carboplatin (300 mg/m2) 3 weeks after the second surgery |

Recurrence was followed up for 3 years | |

| Alina Seixas (2020) (19) | 39 | G2P2 | None | Right adnexal: 11 | NR | 2-year conservative treatment failed (fertility preserved) Surgery: TH + BSO |

No recurrence at 4 years of follow-up | |

| Cheng Chi (2025) (20) | 64 | Unclear | Persistent abdominal pain and distension | Left adnexal: 11 | Malignant behavior | Surgery: TH + BSO Adjuvant chemotherapy with four cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin (TC regimen) was administered |

No recurrence at 3-month follow-up | |

| Ya-Qiong Du (2017) (21) | 73 | NR | Abdominal pain and bloating | Left ovary: 26 | Benign behavior | Simple tumor resection | No recurrence at 6-month follow-up | |

| Tian Qiu (2017) (22) | 53 | NR | Abdominal distension | Left mesosalpinx: 13 | NR | First: TH + BSO Second: Cytoreductive surgery + chemotherapy was performed with cisplatin intraperitoneally and docetaxel intravenously |

Liver and renal failure 2 months after second surgery. Died of the disease | |

| Lenan Liu (2018) (23) | 34 | G0P0 | Unclear | Left adnexal: 6 | NR | Left salpingo-oophorectomy | NR | |

| A. Piciu (2021) (24) | 43 | NR | Unclear | Right adnexal: 7 | Malignant behavior | First: TH + unilateral resection of the right ovarian cyst Second: Both of the annexes were resected along with the omentum and the lymph nodes in the Douglas and subhepatic region Third: Excision of the lymph nodes was performed followed by peritoneal diathermy+ six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy given using paclitaxel and carboplatin Fourth: Cytoreduction + three cycles of carboplatin (AUC5) and etoposide 100-mg regimen Fifth: Excision of the masses + four cycles of chemotherapy with topotecan |

Recurrence four times. Gave up the treatment and loss of evidence of the patient | |

| G. Khastgir (2024) (25) | 60 | G4P4 | Intermittent lower abdominal pain for 2 years | Right adnexal: 9.8 | NR | TH + BSO + peritoneal biopsy and lymph node sampling | No recurrence at 5 years of follow-up | |

| M. Goel (2025) (26) | 65 | NR | None | Fat (3.0 cm), rectouterine pouch (0.9 cm), and left fallopian tube surface (0.7 cm) | Benign behavior | First: Revealing a remote history (32 years prior) of a left para-ovarian cyst Second: TH + BSO |

Alive without radiologic evidence of disease at 15 months. Continued surveillance with CT scans every 6 months is planned. | |

Summary of the clinical characteristics and management in reported cases of female adnexal tumor of Wolffian origin (FATWO) from the past decade.

TH + BSO, total hysterectomy + bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; NR, not reported.

The management of advanced, recurrent, or metastatic FATWO poses a significant challenge due to the lack of established guidelines, with evidence confined to isolated case reports. A variety of chemotherapeutic regimens have been employed, with mixed outcomes. Combinations included paclitaxel/carboplatin (27), cisplatin/cyclophosphamide and etoposide/carboplatin (2), and cisplatin/docetaxel (22). However, the responses are often unsatisfactory and transient. For instance, a patient treated with cisplatin/oxaliplatin/docetaxel experienced adverse effects and succumbed to the disease shortly after a second surgery (22). The potential role of molecular-targeted therapy, particularly tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib, remains intriguing, yet inadequately defined. This interest stems from the observed KIT (CD117) immunoreactivity in a subset of FATWOs (28, 29). However, it is crucial to emphasize that KIT positivity does not consistently predict the efficacy of TKIs. As demonstrated by Wakayama et al. (28), treatment with imatinib mesylate led to only transient disease stabilization—which lasted 4 months—before progression ensued, highlighting the limitations of TKI therapy in the absence of actionable driver mutations. In contrast, more encouraging outcomes have been achieved with chemotherapy. In the same report (28), combination treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel induced a significant response in a patient with recurrent metastatic FATWO following imatinib failure, underscoring the potential utility of platinum-based regimens in this setting.

While surgical resection remains the cornerstone of therapy, the current literature indicates that, for recurrent or metastatic disease, platinum-based combination chemotherapy (e.g., paclitaxel/carboplatin) currently presents the most supported systemic option. The use of TKIs such as imatinib should be approached with caution and may be reserved for cases with confirmed activating mutations, given the documented lack of efficacy in wild-type tumors. In the present case, considering the complete surgical excision with negative margins, the low-grade histological features, and the absence of evidence supporting a clear survival benefit from adjuvant therapy for localized disease, a decision for close clinical and radiological surveillance was made. This conservative approach is supported by the indolent nature of many FATWOs. However, given the documented risk of late recurrence, the patient will be monitored long term.

Emerging evidence suggests that FATWO may share tumorigenic mechanisms with certain ovarian cancers, particularly regarding genomic instability. Kwon et al. demonstrated that MGMT inactivation through promoter hypermethylation may contribute to the pathogenesis of FATWO (27), providing epigenetic insights into its development. Notably, Estevez-Diz et al. proposed STK11 mutation testing for patients with FATWO, as frequent STK11 mutations in a case series indicated potential therapeutic vulnerability to mTOR inhibitors (30). The molecular characterization of eight FATWO cases by Mirkovic et al. revealed distinct genetic alterations: KMT2D variants (57%), STK11 mutations (29%, including one Peutz–Jeghers syndrome case), and ARID1B mutations (14%). Importantly, FATWOs lack the KRAS/NRAS, TP53, and DICER1 mutations typically seen in mesonephric carcinomas or Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors, with an overall low mutational burden, suggesting divergent oncogenic pathways (31). However, it is important to note that emerging evidence suggests that tumors harboring STK11 mutations may represent a distinct biological subset, sometimes termed “STK11 adnexal tumors,” which could be distinguished from classic STK11 wild-type FATWOs in future classifications. This distinction is crucial as it may have significant implications for targeted therapy and genetic counseling (32).

Our literature synthesis highlights the diagnostic dilemma for FATWO: early-stage manifestations are nonspecific, with normal tumor markers in most cases. Symptomatic presentations typically result from mass effects rather than biochemical activity. Although conventionally classified as benign, accumulating reports have described postoperative recurrences and metastases. Current evidence shows uncertain chemotherapy efficacy, leaving complete surgical resection as the mainstay treatment. Given its malignant potential, long-term surveillance remains imperative. This study has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the analysis may introduce inherent biases. Secondly, our immunohistochemical panel did not include PAX8 and WT1, which are pivotal markers for excluding Müllerian lesions, including mesonephric and serous carcinomas. While the distinctive morphology and the existing profile (e.g., calretinin+/inhibin+/GATA3−) strongly support the diagnosis of FATWO, the addition of these markers would have provided greater diagnostic confidence and more comprehensively ruled out morphological mimics.

Conclusions

Based on current evidence, FATWO should not be categorically considered benign. These neoplasms demonstrate concerning biological behaviors, including local invasion, recurrence, and metastatic potential. For postmenopausal patients, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy represents the standard approach. However, the role of adjuvant therapy requires an individualized multidisciplinary team (MDT) evaluation considering pathological risk factors. Notably, the current evidence-based recommendations for fertility-age patients remain insufficient, highlighting the urgent need for high-quality studies to guide clinical practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Second University Hospital and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DL: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. MX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at West China Second Hospital for providing the platform and to the Departments of Pathology for their support in analyzing this case.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Kariminejad MH Scully RE . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin. A distinctive pathologic entity. Cancer. (1973) 31:671–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<671::aid-cncr2820310328>3.0.co;2-k

2

Steed H Oza A Chapman WB Yaron M De Petrillo D . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin: A clinicopathological case report and a possible new treatment. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2004) 14:546–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014319.x

3

Fanghong L Szallasi A Young RH . Wolffian tumor of the ovary with a prominent spindle cell component: report of a case with brief discussion of unusual problems in differential diagnosis, and literature review. Int J Surg Pathol. (2008) 16:222–5. doi: 10.1177/1066896907307034

4

Shalaby A Shenoy V . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin: A review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2020) 144:24–8. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0152-RA

5

Kurita T . Normal and abnormal epithelial differentiation in the female reproductive tract. Differentiation. (2011) 82:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.04.008

6

Masse J Watrin T Laurent A Deschamps S Guerrier D Pellerin I . The developing female genital tract: from genetics to epigenetics. Int J Dev Biol. (2009) 53:411–24. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082680jm

7

Marquette A Moerman P Vergote I Amant F . Second case of uterine mesonephric adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2006) 16:1450–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00489.x

8

Matsuki M Kaji Y Matsuo M . Female adnexal tumour of probable Wolffian origin: mr findings. Br J Radiol. (1999) 72:911–3. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.861.10645202

9

Fukunaga M Bisceglia M Dimitri L . Endometrioid carcinoma of the fallopian tube resembling a female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin. Adv Anat Pathol. (2004) 11:269–72. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000138141.88763.6a

10

Czernobilsky B Lifschitz-Mercer B Trejo L Atlas I . Granulosa cell tumor of the broad ligament: report of a case with emphasis on the differential diagnosis with female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. (2011) 19:783–6. doi: 10.1177/1066896909356104

11

Devouassoux-Shisheboran M Silver SA Tavassoli FA . Wolffian adnexal tumor, so-called female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin (Fatwo): immunohistochemical evidence in support of a Wolffian origin. Hum Pathol. (1999) 30:856–63. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90148-x

12

Deavers MT Malpica A Liu J Broaddus R Silva EG . Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors: an immunohistochemical study including a comparison of calretinin and inhibin. Mod Pathol. (2003) 16:584–90. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000073133.79591.A1

13

Bennett JA Ritterhouse LL Furtado LV Lastra RR Pesci A Newell JM et al . Female adnexal tumors of probable Wolffian origin: morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 15 cases. Mod Pathol. (2020) 33:734–47. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0375-9

14

Al-Agha OM Huwait HF Chow C Yang W Senz J Kalloger SE et al . Foxl2 is a sensitive and specific marker for sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. (2011) 35:484–94. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820a406c

15

Heatley MK . Is female adnexal tumour of probable Wolffian origin a benign lesion? A systematic review of the English literature. Pathology. (2009) 41:645–8. doi: 10.3109/00313020903273084

16

Mashhadi S Ameli F Sheikhhasani S Parviz S Nili F Jahanbin B et al . A bilateral Wolffian adnexal tumor with Malignant behavior: A rare case report with literature review. Iran J Pathol. (2024) 19:453–9. doi: 10.30699/IJP.2024.1999797.3095

17

Hong S Cui J Li L Buscema J Liggins C Zheng W . Malignant female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin: case report and literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2018) 37:331–7. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000422

18

Chen Q Shen Y Xie C . Recurrent and metastatic female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin: A case report and review of the literature. Med (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e25377. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025377

19

Seixas A Tente D Pinto E Goncalves J . Female adnexal tumour of probable Wolffian origin: A rare entity with challenging histopathological diagnosis and unpredictable behaviour. BMJ Case Rep. (2020) 13:e237127. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237127

20

Chi C Li G Zheng Z Wang X Liu X . Malignant Wolffian adnexal tumor in the ovary: A case report and literature review. Front Oncol. (2025) 15:1526030. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1526030

21

Du YQ Song SZ Ni XC Wu JG Wang SL Jiang BJ et al . Large Wolffian adnexal tumor of the ovary: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. (2017) 14:5167–70. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6859

22

Qiu T Teng Y Tong J Tao W Xu L . Recurrent female adnexal tumor of probably Wolffian origin: A case report. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. (2017) 56:382–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.12.017

23

Liu L Fang Q Xing Y . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin arising from mesosalpinx: A case report and review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2018) 44:1859–63. doi: 10.1111/jog.13704

24

Piciu A Cainap C Sur D Havasi A Fetica B Balacescu O et al . Rare Malignant female adnexal tumor of Wolffian origin (Fatwo) with multiple relapses and chemotherapy regimens. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). (2021) 17:259–65. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2021.259

25

Khastgir G Siwatch S Jain V Gupta N . Unraveling the enigma: fatwo and its clinicopathologic implications. BMJ Case Rep. (2024) 17:e261065. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2024-261065

26

Goel M Ronne E Vesterfjell EV Aune G Bennett JA . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin (Fatwo): an unusual case with development of peritoneal lesions after 3 decades. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2025) 44:453–6. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000001103

27

Kwon MJ Yun MJ Kim MK . A female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin showing positive O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase methylation. Obstet Gynecol Sci. (2016) 59:328–32. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.4.328

28

Wakayama A Matsumoto H Aoyama H Saio M Kumagai A Ooyama T et al . Recurrent female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin treated with debulking surgery, imatinib and paclitaxel/carboplatin combination chemotherapy: A case report. Oncol Lett. (2017) 13:3403–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5874

29

Harada O Ota H Takagi K Matsuura H Hidaka E Nakayama J . Female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin: morphological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study with C-kit gene analysis. Pathol Int. (2006) 56:95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01930.x

30

Estevez-Diz MP Bonadio RC Carvalho FM Carvalho JP . Everolimus plus anastrozole for female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin (Fatwo) with stk11 mutation. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2021) 37:100838. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2021.100838

31

Mirkovic J Dong F Sholl LM Garcia E Lindeman N MacConaill L et al . Targeted genomic profiling of female adnexal tumors of probable Wolffian origin (Fatwo). Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2019) 38:543–51. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000545

32

Bennett JA Oliva E Young RH . Stk11 adnexal tumor: A newly recognized entity that expands the spectrum of neoplasms associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gynecol Oncol. (2025) 197:25–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2025.04.001

Summary

Keywords

FATWO, diagnosis, differential, laparoscopy, single-site, treatment, case reports

Citation

Li D-m, Xi M-r and Zeng X (2025) Incidental intraoperative discovery of a Wolffian tumor in a postmenopausal woman: a case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 15:1674008. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1674008

Received

27 July 2025

Accepted

24 September 2025

Published

08 October 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Tullio Golia D’Augè, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Reviewed by

Payman Nasr, California State University, Dominguez Hills, United States

Gaurav Khastgir, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Xi and Zeng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xi Zeng, zengxi1003@hotmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.