- Department of Thoracic Oncology & Oncology Immunotherapy, Beijing GoBroad Hospital, Beijing, China

Patients with brain metastases from lung cancer exhibit rapid disease progression and a poor prognosis, underscoring an urgent need for effective therapeutic strategies. Drug sensitivity testing using patient-derived organoids (PDOs) has emerged as a promising tool for guiding clinical treatment decisions. Here, we report two cases of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with brain metastases where treatment guided by PDO-based drug sensitivity screening aided in disease control. Case 1 involved a patient with an EGFR exon 19 deletion. The corresponding PDO model demonstrated sensitivity to a combination of pemetrexed, carboplatin, and osimertinib, but insensitivity to osimertinib monotherapy. Following this guidance, the patient achieved a partial response (PR) to the triplet regimen and was subsequently de-escalated to maintenance therapy. The patient’s disease remained stable at the time of this report. Case 2 involved a patient with a complex EML4-ALK fusion variant 3 (E6:A20) and a novel NRXN1-ALK fusion (N19:A20). The patient had progressed on multiple lines of therapy, including alectinib and lorlatinib. The PDO model showed sensitivity to brigatinib but insensitivity to ensartinib. Subsequent treatment with brigatinib induced a PR that was sustained for 5.8 months; the patient survived for a total of 9 months following the initiation of this PDO-guided therapy. These two cases suggests that PDOs derived from primary and metastatic lesions may help optimize treatment regimens for patients with lung cancer brain metastases, thereby enabling personalized therapy and potentially improving survival outcomes.

Introduction

A 2022 survey documented 1.06 million new cases of lung cancer and 730,000 related deaths annually in China (1). The presence of brain metastases (BM) is strongly associated with severe morbidity and limited survival in patients with lung cancer (2). Data from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) reveal an overall incidence of BM of approximately 10% at initial diagnosis, rising to 26% in patients with stage IV disease and up to 40% during disease progression, with a median survival time of only 6 months (3). Approximately 70% of patients diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations eventually develop brain metastases (4).

The phase III FLAURA2 study (NCT04035486) established that first-line osimertinib combined with platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy has a manageable safety profile in metastatic EGFR-mutated NSCLC (5). Results from this trial confirmed superior progression-free survival (PFS) in the osimertinib-chemotherapy group (median PFS 24.0 months) versus the osimertinib monotherapy group (median PFS 15.3 months) (6). However, in clinical practice, patients achieving an objective response often desire a reduction in treatment burden during maintenance. Such a de-escalation requires rigorous, evidence-based assessment to avoid compromising efficacy.

Among patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged NSCLC, BM is present in 23.8% at the time of advanced disease diagnosis (7). The majority (85%) of these are EML4-ALK variants (8). The EML4-ALK fusion variant 3 (v3), resulting from a fusion between exon 6 of EML4 and exon 20 of ALK (E6:A20), is associated with greater resistance to second- and third-generation ALK inhibitors compared to first-generation agents (9). Consequently, data are lacking to inform treatment selection for patients with the ALK v3 fusion, particularly when co-occurring with novel fusions after progression on standard therapies.

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) are three-dimensional in vitro models generated from a patient’s tumor tissue, which are increasingly used for predicting therapeutic response and facilitating personalized medicine (10). Here, we describe two cases of NSCLC with brain metastases where PDO-based drug sensitivity screening helped guide therapy, leading to objective clinical responses.

Case report

Case 1

In mid-December 2022, a 52-year-old male presented with a headache, dizziness, blurred vision, intermittent nausea, and a “walking on cotton” sensation in his feet. On January 13, 2023, a cranial MRI revealed a malignant tumor in the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA), with significant surrounding edema. The patient underwent resection of the CPA tumor on January 17, 2023, which alleviated his symptoms. Pathological analysis confirmed metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma. A PET-CT scan on January 28, 2023, identified a hypermetabolic mass in the right lung with associated mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

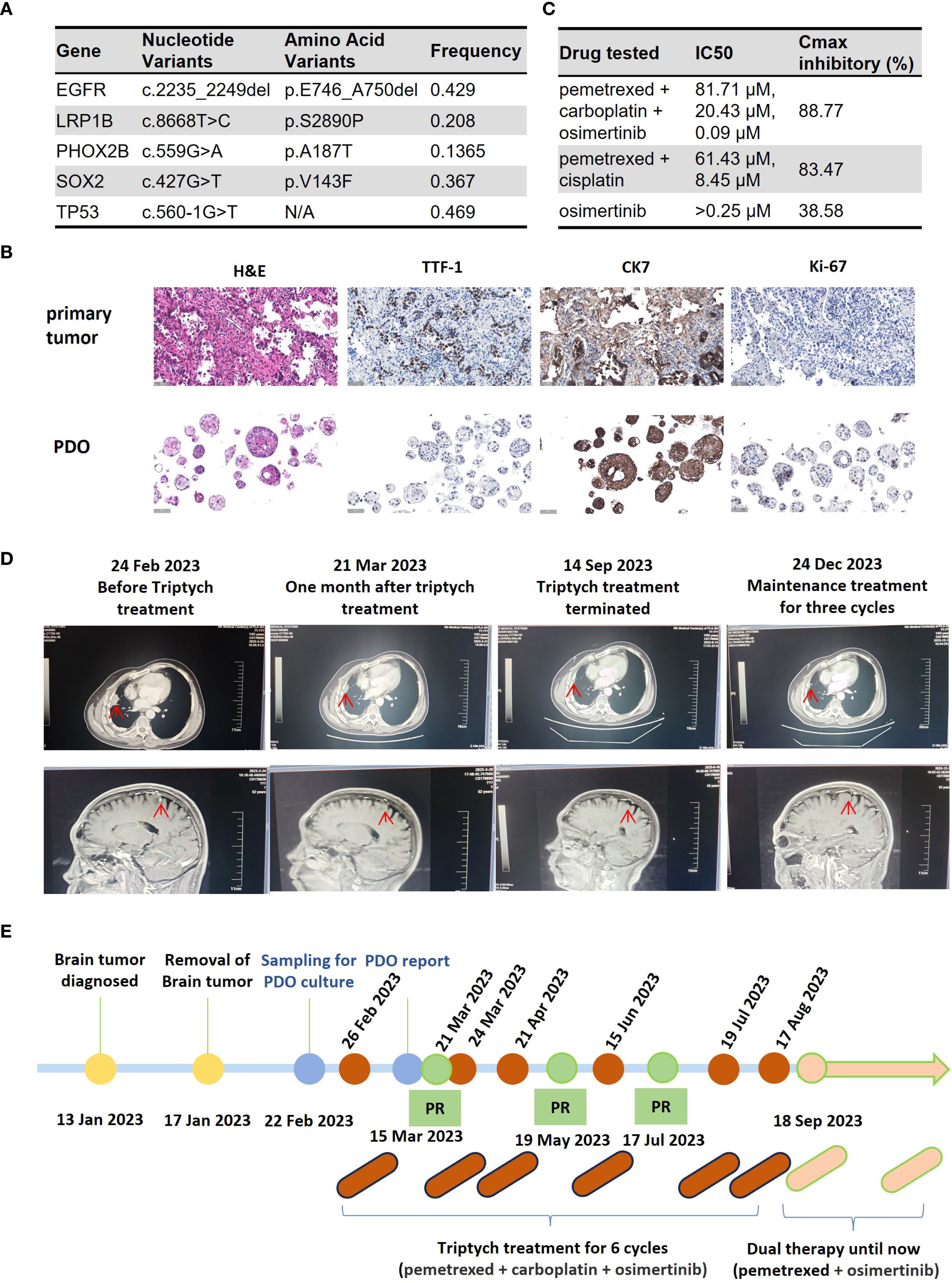

On February 22, 2023, the patient underwent a CT-guided lung biopsy at our hospital for PDO culture and drug sensitivity testing (Beijing Daxiang Biotech, China). Pathological and genetic analyses confirmed lung adenocarcinoma with an EGFR exon 19 deletion and a TP53 mutation (Figure 1A). While awaiting PDO results, the patient commenced empirical treatment on February 26, 2023, with a triplet regimen of pemetrexed (900 mg), carboplatin (500 mg), and osimertinib (80 mg orally). The PDO drug sensitivity report was issued on March 15, 2023. The results prospectively validated the choice of therapy, showing high sensitivity to the triplet combination (maximal inhibition: 88.77%) and the chemotherapy doublet (pemetrexed+cisplatin, 83.47%), but insensitivity to osimertinib monotherapy (38.58%) (Figure 1C). The PDO was histologically consistent with the source tumor (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Clinical course of Case 1, a patient with EGFR-mutant NSCLC with brain metastases. (A) Table of somatic mutations detected in the tumor tissue sample. (B) Histological comparison confirming the fidelity of the patient-derived organoid (PDO) to the primary tumor via H&E and IHC staining for key biomarkers. (C) Results of the PDO drug sensitivity assay. Cell viability was measured using an ATP-based assay following drug exposure. The table displays the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and the maximal inhibitory rate for each agent. (Data are presented as the mean of technical replicates; error bars and statistical tests were not reported). (D) Serial imaging confirming a partial response (PR) to treatment. (E) Timeline of the patient’s clinical course, from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up. (H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1; CK7, cytokeratin 7; PDO, patient-derived organoid; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration).

Imaging assessments confirmed a partial response (PR) (Figure 1D). On September 18, 2023, treatment was de-escalated to maintenance therapy with pemetrexed and osimertinib. The patient’s disease remained stable for over 8 months at the time of submission. The treatment timeline is shown in Figure 1E.

Case 2

A 33-year-old male presented with pain and reduced mobility in the left lower limb. PET-CT on September 30, 2021, at an external hospital revealed lung cancer in the right lower lobe with obstructive atelectasis, multiple lymph node metastases (right supraclavicular, mediastinal, retroperitoneal), and bone metastases. Bronchoscopic pathology confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Genetic testing identified an EML4-ALK fusion (E6:A20) and a novel NRXN1-ALK fusion (N19:A20).

From October 2021 to June 2022, first-line alectinib yielded a partial response with progression-free survival of 8 months. Second-line lorlatinib in July 2022 led to progression after 1 month. Third-line albumin-bound paclitaxel (200 mg on days 1 and 8) + carboplatin (600 mg on day 1) for 2 cycles achieved stable disease. Fourth-line albumin-bound paclitaxel + carboplatin + tislelizumab for 3 cycles (October 2022 to January 2023) resulted in partial response. After progression in February 2023, fifth-line treatment included 14 cycles of local radiotherapy to the right skeletal bone and one cycle of oral anlotinib, discontinued due to intolerance. Sixth-line albumin-bound paclitaxel + carboplatin + tislelizumab for 1 cycle in March 2023 led to progression.

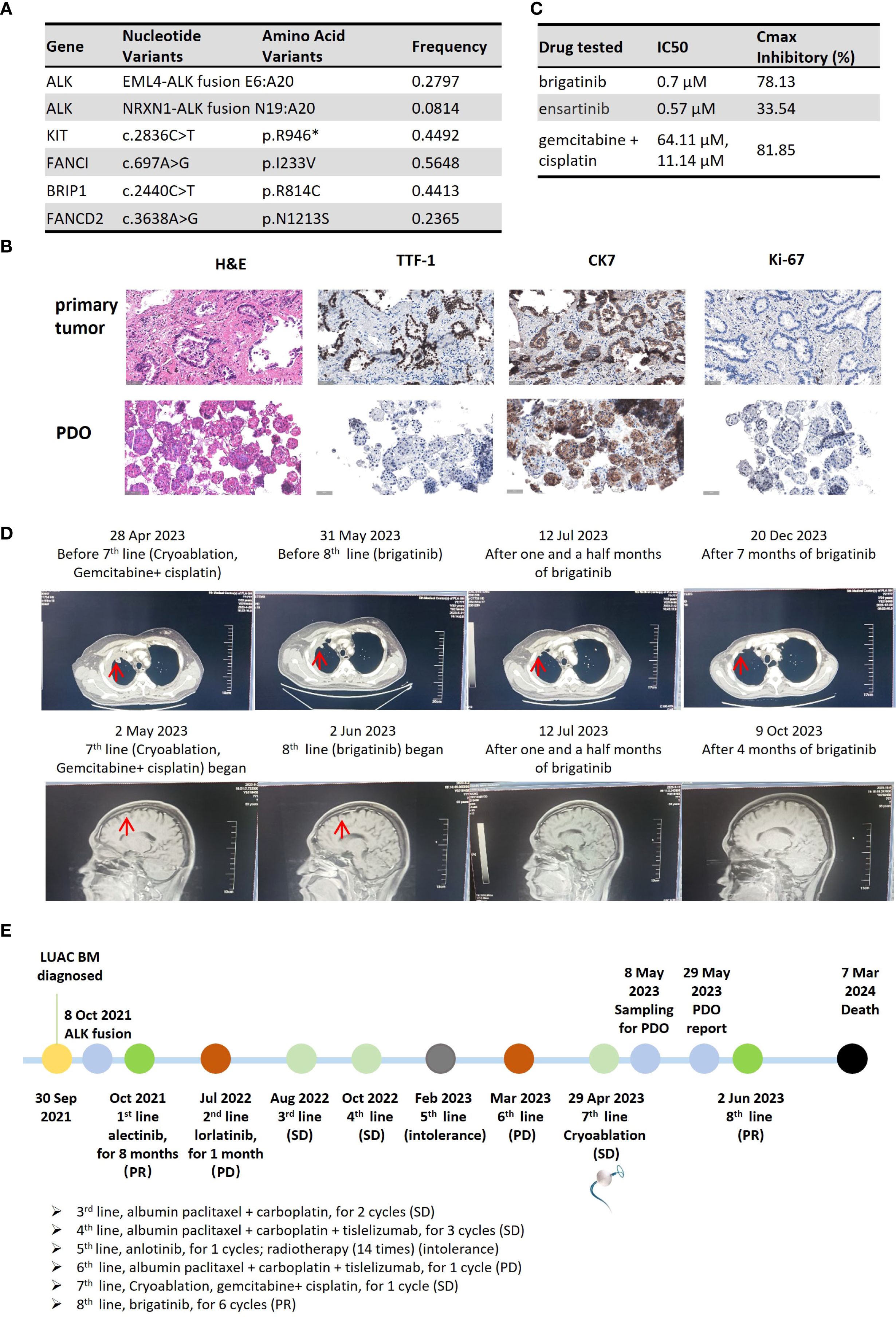

On April 27, 2023, the patient was admitted to our hospital with imaging-confirmed progression. CT-guided percutaneous puncture of a right pleural metastatic lesion with combiknife cryoablation, digital subtraction angiography, bronchial artery embolization, and perfusion chemotherapy (gemcitabine 1.6 g + cisplatin 120 mg) was performed as seventh-line therapy. Three fresh samples from the May 8, 2023, puncture were sent for PDO culture and testing (Beijing Daxiang Biotech, China). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the metastases confirmed retention of both ALK fusions (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Clinical course of Case 2, a patient with dual ALK-fusion NSCLC. (A) Table of somatic mutations and fusions detected in the metastatic tumor tissue. (B) Histological comparison confirming the fidelity of the PDO to the metastatic pleural tumor. (C) Results of the PDO drug sensitivity assay. The table displays the IC50 and maximal inhibitory rate for each tested agent. (IC50 values represent the mean of technical replicates; standard deviations are not reported). (D) Serial imaging showing a PR after initiation of 8th-line therapy with brigatinib. (E) Timeline of the patient’s extensive clinical course, culminating in a PDO-guided therapy selection. (H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1; CK7, cytokeratin 7; PDO, patient-derived organoid; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration).

PDO results on May 29, 2023, showed brigatinib with 78.13% inhibition (IC50: 0.7 μM) and ensartinib with 33.54% (IC50: 0.57 μM). Gemcitabine + cisplatin achieved 81.85% inhibition (IC50: 64.11 μM and 11.14 μM) (Figure 2C). Organoids preserved source tumor features, including CK7, Ki-67, and TTF-1 expression (Figure 2B). The report was issued 21 days post-collection.

On May 30, 2023, follow-up imaging showed stable disease after 1 month of gemcitabine + cisplatin. Although the treatment regimen achieved some disease control, the patient opted to try the oral brigatinib, which demonstrated the second-highest inhibition rate in the PDO testing and offered a more convenient administration route. Eighth-line brigatinib started on June 2, 2023, with partial response on July 10, 2023 (Figure 2D). Adverse events included rash and diarrhea. Disease remained stable until November 24, 2023 (5.8 months). The patient died from progression and multi-organ failure 9 months after initiating PDO-guided brigatinib. The treatment timeline is shown in Figure 2E.

Discussion

PDO derivation and testing are integral to precision medicine in lung cancer, especially for alterations of unknown clinical significance (11–13). PDOs preserve the biological and genetic characteristics of parental tumors, reflecting changes in gene expression and metabolism induced by prior therapies (14, 15).

For newly diagnosed EGFR-mutated NSCLC with brain metastases, osimertinib-chemotherapy is often recommended, but patients may desire reduced burden during maintenance. In China, monthly hospital visits and biochemical monitoring for chemotherapy add time and cost. Many prefer oral osimertinib alone once stable. Here, PDO insensitivity to osimertinib monotherapy prevented premature de-escalation, emphasizing the need for informed regimen adjustments.

In Case 2, initial detection of ALK v3 fusion with novel NRXN1-ALK (N19:A20) led to progression after 8 months of alectinib and inefficacy of lorlatinib. Subsequent lines failed to control progression, with ALK fusions persisting in metastases. ALK v3 fusions are refractory; studies show median PFS of 34.9 months with alectinib versus 14.6 months with crizotinib (9, 16). Third-generation ALK inhibitors yield longer PFS than second-generation ones in brain metastases (17). Dual fusions may confer sensitivity or resistance to ALK inhibitors and chemotherapy (18–20). We hypothesize the novel fusion contributed to resistance, complicating treatment of brain and systemic metastases. PDO results indicated sensitivity to brigatinib and gemcitabine + cisplatin, and resistance to ensartinib. This aligned with stable disease on gemcitabine + cisplatin and subsequent brigatinib benefit. Certain gatekeep mutations may emerge after treatment with alectinib. However, our study did not perform targeted sequencing on the PDO samples to identify specific EML4-ALK fusion variants or co-occurring mutations. As highlighted by Lin et al. (21), brigatinib has demonstrated activity in patients with alectinib-refractory ALK-positive NSCLC. This study identified several potential mutations that can arise after alectinib treatment, which may influence the response to subsequent therapies such as brigatinib.

Case reports show PDOs guiding treatment in LRRTM4-ALK fusions (13) and EGFR-negative NSCLC (22). PDOs can aid diagnosis and therapy even from unknown primaries, metastases, lymph nodes, or ascites (23, 24), advancing precision oncology.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as a report of only two cases, its findings lack statistical power and cannot be generalized. The PDO models, while useful for drug screening, lack an immune microenvironment and other systemic factors, representing an inherent simplification of in vivo tumor biology. Furthermore, we did not report the overall success rate of PDO establishment, which is a key metric for assessing feasibility. Based on published literature, the success rate for establishing NSCLC PDOs can vary, typically ranging from 70% to 88%, depending on factors such as sample type, tumor cellularity, and culture techniques (25, 26). Secondly, these organoids were not used for downstream mechanistic studies to formally explore the basis for drug resistance or the functional role of the novel ALK fusion. Lastly, we are working to shorten the 21-day turnaround time for testing to better align with urgent clinical decision-making timelines.

Conclusion

These two case reports illustrate the utility of PDO-based drug sensitivity assays in newly diagnosed and multi-line progressed patients with lung cancer brain metastases. They encourage clinicians to leverage PDOs for selecting personalized regimens, especially when genomic profiling offers multiple options.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing GoBroad Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LQ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. LL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. HQ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beijing Daxiang Biotech Co., Ltd. for technical support in organoid cultures. We thank Dr. Bin Qiao for editing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. (2024) 4:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.00

2. Goldberg SB, Contessa JN, Omay SB, and Chiang V. Lung cancer brain metastases. Cancer J. (2015) 21:398–403. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000146

3. Waqar SN, Samson PP, Robinson CG, Bradley J, Devarakonda S, Du L, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis at presentation. Clin Lung Cancer. (2018) 19:e373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.01.007

4. Ge M, Zhuang Y, Zhou X, Huang R, Liang X, and Zhan Q. High probability and frequency of EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases. J Neurooncol. (2017) 135:413–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2590-x

5. Planchard D, Feng PH, Karaseva N, Kim SW, Kim TM, Lee CK, et al. Osimertinib plus platinum-pemetrexed in newly diagnosed epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: safety run-in results from the FLAURA2 study. ESMO Open. (2021) 6:100271. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100271

6. Planchard D, Jänne PA, Cheng Y, Yang JC, Yanagitani N, Kim SW, et al. Osimertinib with or without chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:1935–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2306434

7. Rangachari D, Yamaguchi N, VanderLaan PA, Folch E, Mahadevan A, Floyd SR, et al. Brain metastases in patients with EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancers. Lung Cancer. (2015) 88:108–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.020

8. Zhang SS, Nagasaka M, Zhu VW, and Ou SI. Going beneath the tip of the iceberg. Identifying and understanding EML4-ALK variants and TP53 mutations to optimize treatment of ALK fusion positive (ALK+) NSCLC. Lung Cancer. (2021) 158:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.06.012

9. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:829–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795

10. Polak R, Zhang ET, and Kuo CJ. Cancer organoids 2.0: modelling the complexity of the tumour immune microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. (2024) 24:523–39. doi: 10.1038/s41568-024-00706-6

11. Xie Y, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Xie X, Lin X, Tang Q, et al. Analysis of the resistance profile of real-world alectinib first-line therapy in patients with ALK rearrangement-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer using organoid technology in one case of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. (2024) 16:3854–63. doi: 10.21037/jtd-23-1964

12. Weng CD, Liu KJ, Jin S, Su JW, Yao YH, Zhou CZ, et al. Triple-targeted therapy of dabrafenib, trametinib, and osimertinib for the treatment of the acquired BRAF V600E mutation after progression on EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2024) 13:2538–48. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-24-358

13. Li B, Jia Z, Huang Z, Xue J, Wang Y, Guo C, et al. Adjuvant crizotinib treatment selected by patient-derived organoids in a patient with stage IIIA adenocarcinoma with novel LRRTM4-ALK fusion: a case report. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2023) 12:2322–9. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-23-48

14. Wang HM, Zhang CY, Peng KC, Chen ZX, Su JW, Li YF, et al. Using patient-derived organoids to predict locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer tumor response: A real-world study. Cell Rep Med. (2023) 4:100911. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100911

15. Peschke K, Jakubowsky H, Schäfer A, Maurer C, Lange S, Orben F, et al. Identification of treatment-induced vulnerabilities in pancreatic cancer patients using functional model systems. EMBO Mol Med. (2022) 14:e14876. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114876

16. Camidge DR, Dziadziuszko R, Peters S, Mok T, Noe J, Nowicka M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data and impact of the EML4-ALK fusion variant on the efficacy of alectinib in untreated ALK-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the global phase III ALEX study. J Thorac Oncol. (2019) 14:1233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.007

17. Ando K, Manabe R, Kishino Y, Kusumoto S, Yamaoka T, Tanaka A, et al. Comparative efficacy of ALK inhibitors for treatment-naïve ALK-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer with central nervous system metastasis: A network meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:2242. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032242

18. Tao H, Liu Z, Mu J, Gai F, Huang Z, and Shi L. Concomitant novel ALK-SSH2, EML4-ALK and ARID2-ALK, EML4-ALK double-fusion variants and confer sensitivity to crizotinib in two lung adenocarcinoma patients, respectively. Diagn Pathol. (2022) 17:27. doi: 10.1186/s13000-022-01212-9

19. Luo J, Gu D, Lu H, Liu S, and Kong J. Coexistence of a novel PRKCB-ALK, EML4-ALK double-fusion in a lung adenocarcinoma patient and response to crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol. (2019) 14:e266–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.07.021

20. Wang Z, Luo Y, Gong H, Chen Y, and Tang H. A novel double fusion of EML4-ALK and PLEKHA7-ALK contribute to rapid progression of lung adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. Discov Oncol. (2024) 15:638. doi: 10.1007/s12672-024-01517-9

21. Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Schoenfeld AJ, Yeap BY, Saxena A, Ferris LA, et al. Brigatinib in patients with alectinib-refractory ALK-positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2018) 13:1530–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.06.005

22. Pan Y, Cui H, and Song Y. Organoid drug screening report for a non-small cell lung cancer patient with EGFR gene mutation negativity: A case report and review of the literature. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1109274. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1109274

23. Ruhe L, Heibl S, Czompo M, Haybaeck J, Loskutov J, Regenbrecht MJ, et al. Functional precision medicine successfully guides therapeutic regimen of ‘Cancer of unknown primary’ Later classified as triple-negative breast cancer: A case report. Case Rep Oncol. (2024) 17:490–6. doi: 10.1159/000538137

24. Chen W, Fang PH, Zheng B, Liang Y, Mao Y, Jiang X, et al. Effective treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer guided by drug sensitivity from ascites-derived organoid: A case report. Int J Womens Health. (2023) 15:1047–57. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S405010

25. Kim M, Mun H, Sung CO, Cho EJ, Jeon HJ, Chun SM, et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:3991. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11867-6

Keywords: case report, non-small cell lung cancer, organoid, brain metastasis, personalized medicine

Citation: Qin L, Wang S, Li L and Qin H (2025) Patient-derived organoid facilitating personalized medicine in non-small cell lung cancer: two case reports. Front. Oncol. 15:1674897. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1674897

Received: 28 July 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 03 October 2025.

Edited by:

James C.M. Ho, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Frankie Chi Fat Ko, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaRoland Leung, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2025 Qin, Wang, Li and Qin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haifeng Qin, aGlmb0AyNjMubmV0

Lili Qin

Lili Qin Haifeng Qin

Haifeng Qin