- 1Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Taiyuan, China

- 2Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital/Shanxi Hospital Affiliated to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, The Fifth Clinical Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

- 4Department of Stomatology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China

- 5School of Stomatology, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 6School of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

Background: Lip cancer is a type of oral cancer with a different prognosis than that of other cancers. However, a lack of well-established understanding of the relationship between the peripheral blood inflammatory biomarker (PBIB) and prognosis in patients with lip cancer is evident. This study investigated the prognostic value of inflammatory markers and other unfavourable prognostic factors. It compares the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR), systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV) and prognosis nutritional index (PNI) in patients with lip cancer.

Materials and methods: This retrospective study included 122 patients with lip cancer. Clinical characteristics and hematological parameters were retrospectively obtained prior to treatment. SII, PLR, NLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV and PNI were calculated to analyze their effects on survival and recurrence further.

Results: Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis demonstrated SII >534.286, PLR >146.528, NLR >2.134, LMR ≤4.000, SIRI >0.7100, PIV >211.930, PNI ≤51.900 were factors associated with increased mortality. Univariate analysis showed that these inflammatory parameters were associated with a lower survival rate. In multivariate analysis, NLR was identified as having a cumulative role in predicting overall survival (HR=5.885, 95% CI: 2.131–16.256, P<0.001).

Conclusion: This study revealed that NLR is a promising blood biomarker in patients with lip cancer. The predictive power of other PBIBs, albeit showing a trend towards significance, were not statistically significant, possibly due to the limited number of cases. The clinical applicability of other hematological indicators requires further study.

1 Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death in both developed and developing countries. Oral cavity and pharynx cancer is the 6th most common malignant tumor in the world. Approximately 700,000 newly diagnosed cases and 350,000 deaths occur annually worldwide. A National Cancer Institute study showed that the 5-year relative mortality of oral and pharyngeal cancer exceeds 30% (1). However, cancer in the front of the mouth, such as lip cancer, has a better prognosis with lower mortality (<15%) (2) than cancers in other areas of the oral cavity and pharynx do, such as those in the tongue (68.8%) (3), floor of the mouth (>60%) (4), laryngeal (61%), oropharyngeal (41%) and hypopharyngeal (25%) (5).

Inflammation is a pivotal factor in tumors, and growing evidence indicates that it can regulate the tumor microenvironment and immune reaction to accelerate tumor proliferation, progression, and lymph node metastasis (6). Peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (PBIBs), including the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), have been reported in head and neck cancers. In recent years, many new biomarker such as systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV) and prognosis nutritional index (PNI) have been proven to affect survival in various cancer type (7). All these peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers primarily encompass ratios between neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, monocytes, and serum albumin levels. Neutrophils, one of the primary effector cells in inflammatory responses, release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that promote tumor invasion and metastasis (8). Lymphocytes play an important role in the immune system and are capable of recognizing and eliminating tumor cells. Platelets are essential elements of innate and adaptive immune responses, and abnormal platelets also contribute to tumor metastasis and poor prognosis (9). Monocytes have a strong inhibitory effect on a variety of antitumor immune cells. In many tumors, such as prostate cancer (10), breast cancer (11), and colorectal cancer (12), a high number of monocytes is associated with poor prognosis.

Several meta-analyses of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) have confirmed that inflammatory biomarkers such as the NLR and PNI serve as reliable predictors of cancer prognosis (7, 13). Beyond OSCC, a growing body of evidence underscores the broad prognostic utility of these markers across various head and neck malignancies. For instance, in malignant salivary gland tumors, the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) have been shown to independently predict overall survival, with their combination offering high prognostic accuracy (AUC=0.884) and significantly stratifying 5-year survival outcomes (14). Moreover, the clinical relevance of these biomarkers extends beyond survival prognostication to include the detection of occult lymph node metastases. In early-stage oral cavity carcinomas (T1-T2/N0), inflammatory markers such as PLR, NLR, and SII demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in identifying occult neck metastases, thereby supporting preoperative decision-making regarding neck management. However, while these studies affirm the value of systemic inflammation indices in sites such as the oral cavity and salivary glands, their predictive power for long-term survival and recurrence specifically in lip cancer remains insufficiently elucidated (15). The current study therefore aimed to comprehensively evaluate the prognostic significance of an extended panel of inflammatory and nutritional marker, including SII, NLR, PLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV, and PNI, in a well-defined cohort of lip cancer patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients and methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with lip cancer treated at Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital between September 1999 and August 2020. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Histopathologically confirmed carcinoma of the lip (Squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma, etc.); (2) Underwent curative-intent surgical resection and/or radiotherapy as the primary treatment (wide local excision, with or without neck dissection, and/or reconstructive surgery); (3) Availability of peripheral blood specimens collected within one week prior to any treatment; (4) Availability of complete clinical information and follow-up data. To ensure a comprehensive analysis of the biomarkers’ prognostic value across disease severities, patients across all T and N stages, including those with clinically or pathologically confirmed neck lymph node metastases, were included. Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of synchronous or metachronous malignancies in other organs; (2) Presence of preoperative active infection or systemic inflammatory conditions (inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disorders) that could confound the inflammatory biomarker levels; (3) History of prior radiotherapy (RT) or chemotherapy (CMT) for any condition in the head and neck region; (3) Patients with incomplete medical records or lost to follow-up.

In total, 122 patients with lip cancer met the criteria and were enrolled in the present study (89 men and 33 women; median age 64 years; interquartile range: 52.00-73.25 years). These patients were classified and staged according to the Union for International Cancer Control tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification for head and neck cancer.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliated institution (approval number: KY2024048). The requirement of informed consent was waived.

2.2 Data collection

The following clinical characteristics were retrospectively reviewed using inpatient records: sex, age, BMI, tumor size, tumor location, surgical treatment, neck dissection, radiotherapy, tumor stage, pathological type, prognosis, lymph node metastasis, death, and recurrence.

All blood specimens were acquired from patients within 7 days of treatment. Peripheral blood cell counts were determined and classified, including neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets. Inflammatory indices were calculated based on previously established methods (16–18): SII = platelets × neutrophils/lymphocytes, NLR = neutrophil count/lymphocyte count, PLR =platelet count/lymphocyte count, LMR = lymphocyte count/monocyte count, SIRI = (neutrophil count × monocyte count)/lymphocyte count, PIV = (platelet count × neutrophil count × monocytes count)/lymphocyte count, serum albumin + 5 × lymphocyte count was used to determine the PNI.

Clinical staging was determined in accordance with the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th Edition). All patients underwent a standardized diagnostic workup, which included a comprehensive physical examination, high-resolution ultrasonography of the neck to assess lymph node status, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the local extent of the primary tumor and rule out distant metastasis. The final pathological stage (pTNM) was assigned for surgically treated patients based on histopathological examination of the resection specimens.

After primary treatment, patients were regularly followed up according to our institutional protocol. Follow-up examinations were scheduled every 3 months for the first two years, every 6 months for the next three years, and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included a thorough physical examination of the head and neck region and ultrasonography of the neck. Additional imaging (CT, MRI, or PET-CT) was performed if recurrence or metastasis was clinically suspected. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to the first event of disease recurrence or death from any cause. Disease recurrence was defined as the confirmed reappearance of the tumor following primary treatment, encompassing local (at the primary site), regional (in cervical lymph nodes), or distant metastasis.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to identify and determine the optimal cutoff values of the SII, NLR, PLR, LMR SIRI, PIV and PNI. Using the maximum area under the curve (AUC) method, we systematically evaluated the predictive performance of each biomarker at different threshold levels for 5-year overall survival. The optimal cutoff points were selected based on thresholds yielding the highest AUC values, thereby maximizing their prognostic discrimination capability.

The Mann-Whitney U test and the chi-square test were used to analyze the differences between inflammatory indices and the prognosis of lip cancer, respectively. Univariate analyses and Cox proportional regression models were used to estimate the predictive value of the variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to visualize the prognosis of the variables. The log-rank test was used to analyze survival differences between the groups and to draw a survival curve. All statistical analyses were performed using bilateral P<0.05, which indicated a statistically significant difference.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

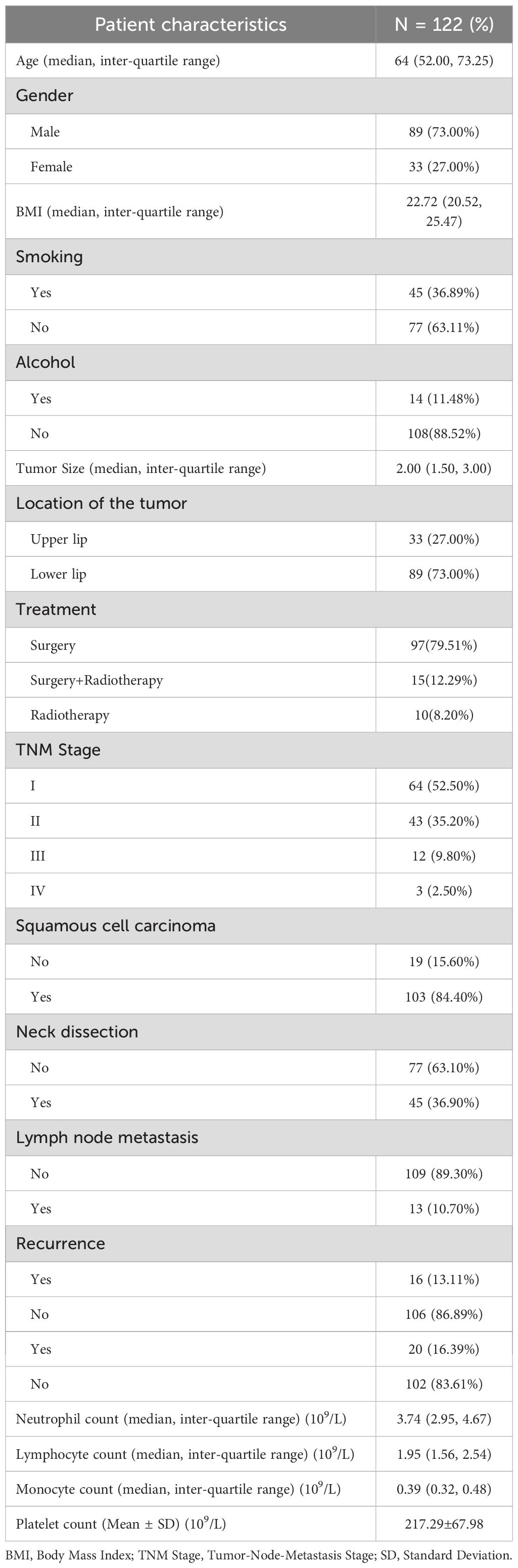

Detailed characteristics of the 122 patients are shown in Table 1. In short, the patients included 89 (73.00%) males and 33 (27.00%) females aged 17–90 years. The mean age at diagnosis was 64 (52.00, 73.25) years. 36.89% (45/122) of participants reported having a smoking history, while 11.48% (14/122) indicated a history of alcohol consumption. In the current study, most lesions were located in the lower lip (73.00%), while 33 (27.00%) were located in the upper lip, with a mean tumor size of 2.36 ± 1.14cm. In this study, the treatment modalities for lip cancer consisted of surgery alone (97 patients, 79.51%), surgery combined with radiotherapy (15 patients, 12.29%), and radiotherapy alone (10 patients, 8.20%). No patients underwent chemotherapy as part of their treatment regimen. Most of patients (84.40%) were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, 15.60% of patients were other clinicopathologic results. 64 (52.50%) patients were at TNM stage I, 43 (35.20%) were at stage II. Neck dissection was performed in 45 patients (36.90%), among whom 13 (10.70% of total patients) had lymph node metastasis. The complete blood count analysis revealed the following median values with interquartile ranges: neutrophils 3.74 (2.95-4.67) × 109/L, monocytes 1.95 (1.56-2.54) × 109/L, and lymphocytes 0.39 (0.32-0.48) × 109/L Platelets averaged 217.29 ± 67.98 × 109/L.

3.2 Prognostic performance of inflammatory biomarkers

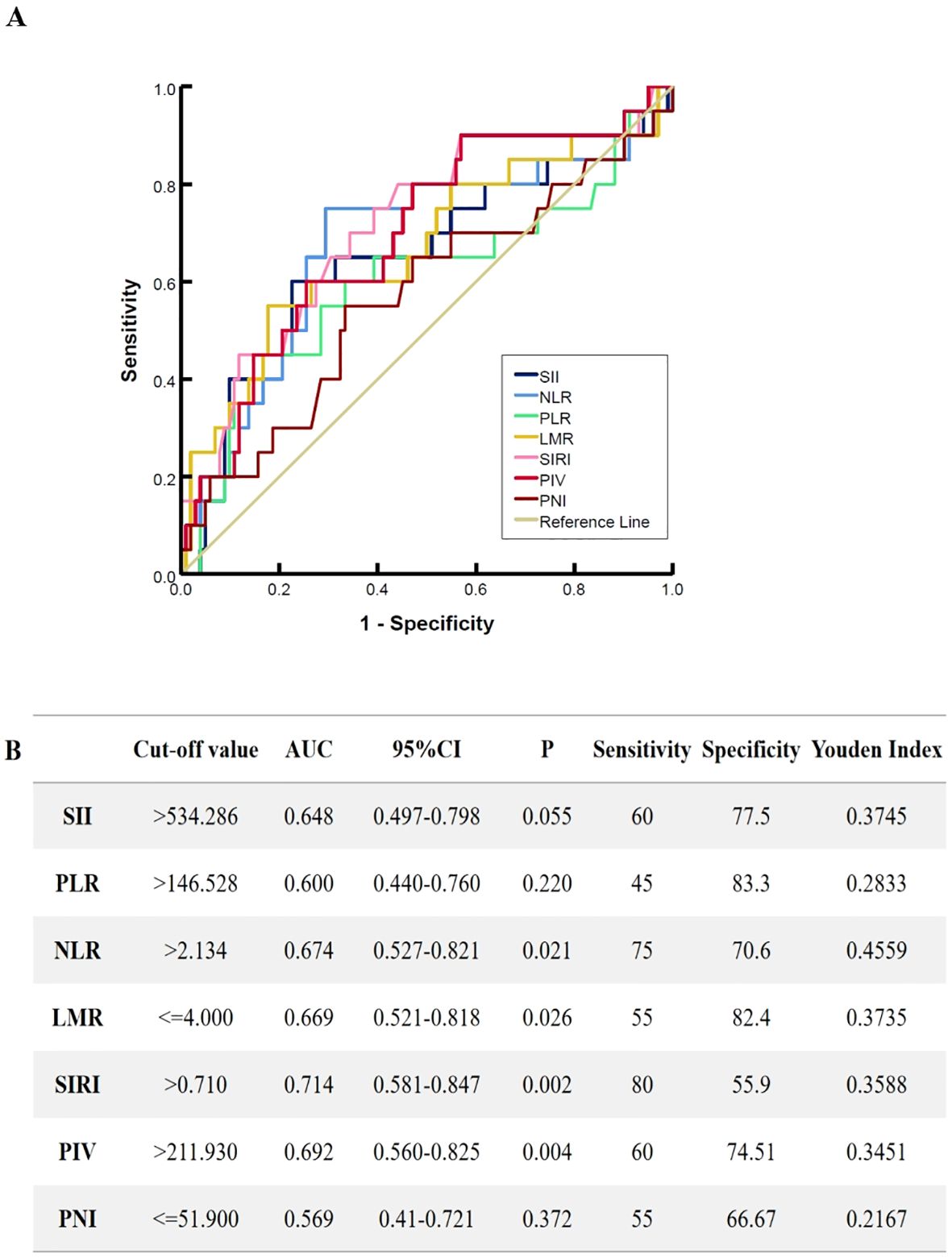

Using the SII, NLR, LMR, PLR, SIRI, PIV, and PNI as test variables, ROC curves were used to calculate and identify the optimal cutoff values of the inflammatory markers for overall survival. The optimal cutoff values were as follows: SII=534.286; PLR=146.528; NLR=2.134; LMR=4.000; SIRI=0.710; PIV=211.930 and PNI=51.900. Figure 1 shows the ROC curves of the pretreatment inflammation indexes and nutritional index.

Figure 1. The receiver operating characteristic curves for pretreatment inflammation markers. (A) the ROC characteristic of SII, NLR, LMR, PLR, SIRI, PIV and PNI, (B) The selection of the optimal cutoff values and predictive power of inflammation markers on patient. SII, systemic immune/inflammatory response index calculated by multiplying platelets by neutrophils and divided by lymphocytes; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; PIV, pan-immune-inflammation value; PNI, prognosis nutritional index.

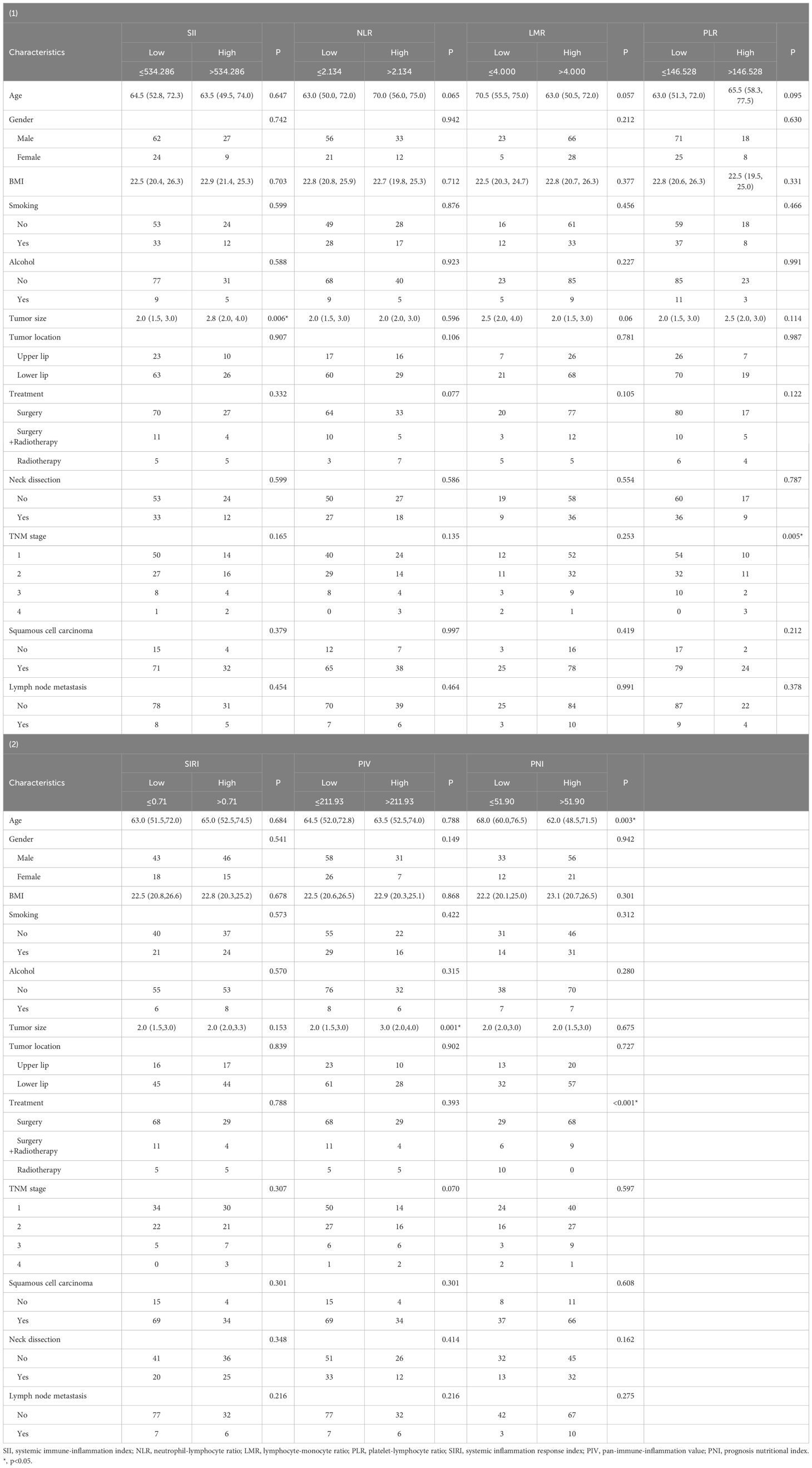

To elucidate the significance of these peripheral blood related indexes in the prognosis of lip cancer, all patients were divided into two groups based on the optimal cutoff points for further analysis (low and high values). The correlations among the SII, NLR, PLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV, PNI and clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were investigated (Table 2). In this study, the NLR and SIRI groups analysis indicated no significant baseline differences between the high and low cutoff values groups. The high SII group was significantly correlated with a larger tumor size (P =0.006), and significant differences in TNM stage were observed between the higher PLR group and the lower group (P =0.005). Differences of tumor size (P =0.001) were obvious between different PIV groups. The Age (P <0.003) and different treatment approaches (P <0.001) differed significantly between PNI groups.

Table 2. Correlation between hematological parameters and clinicopathological characteristics of lip cancer patients.

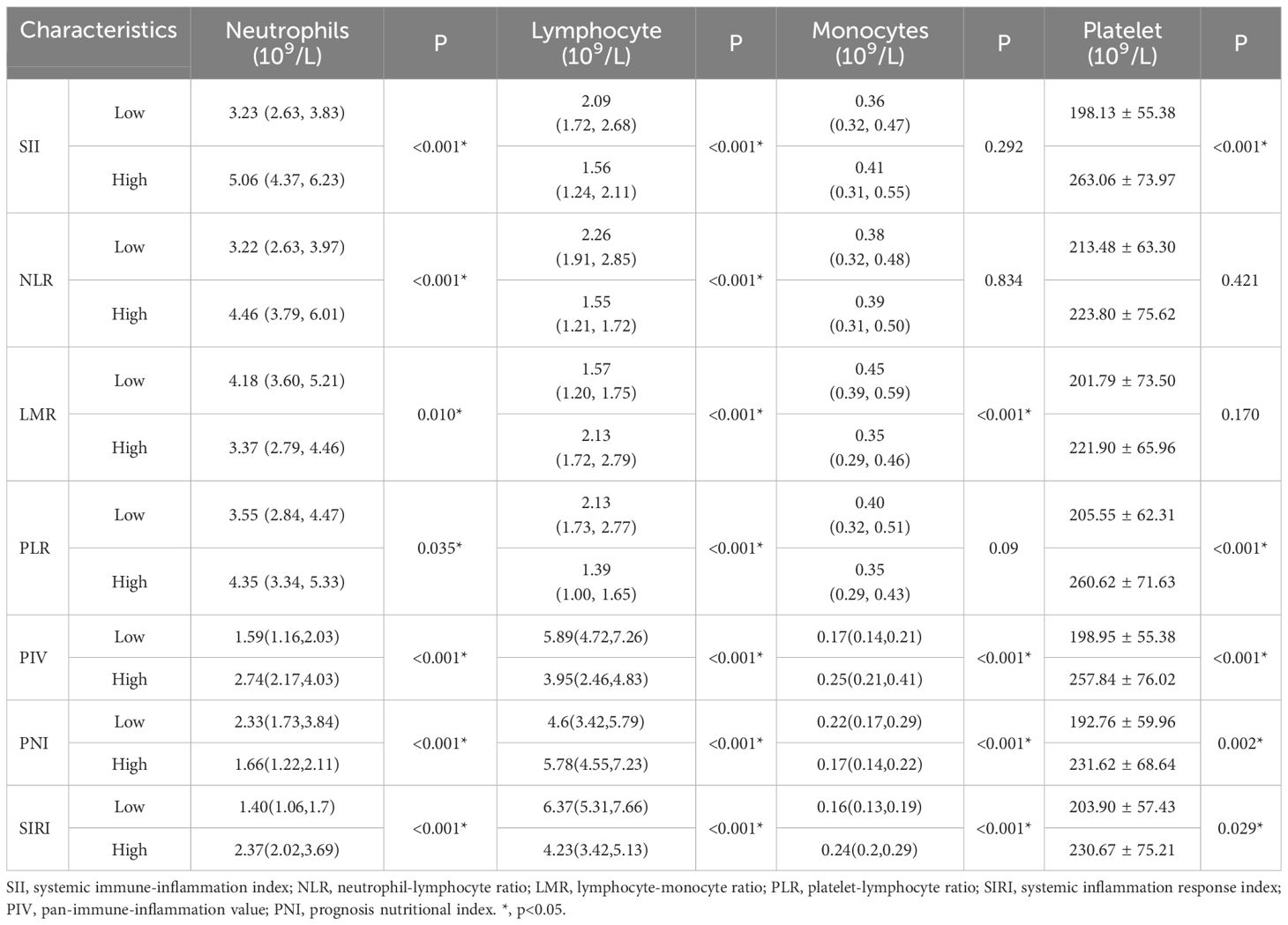

When inflammation indices and other clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed, there were no significant differences in the location of lip cancer, neck dissection, lymph node status, or pathological type. Both groups across the seven inflammation indices were associated with neutrophils, lymphocytes (P <0.05) (Table 3), LMR, SIRI, PIV and PNI groups were significantly correlated with monocytes count; SII, PLR, SIRI, PIV and PNI groups were significantly correlated with Platelet count.

Table 3. Correlation between biomarkers for hematological parameter and haemocytes of lip cancer patients.

3.3 Survival analysis

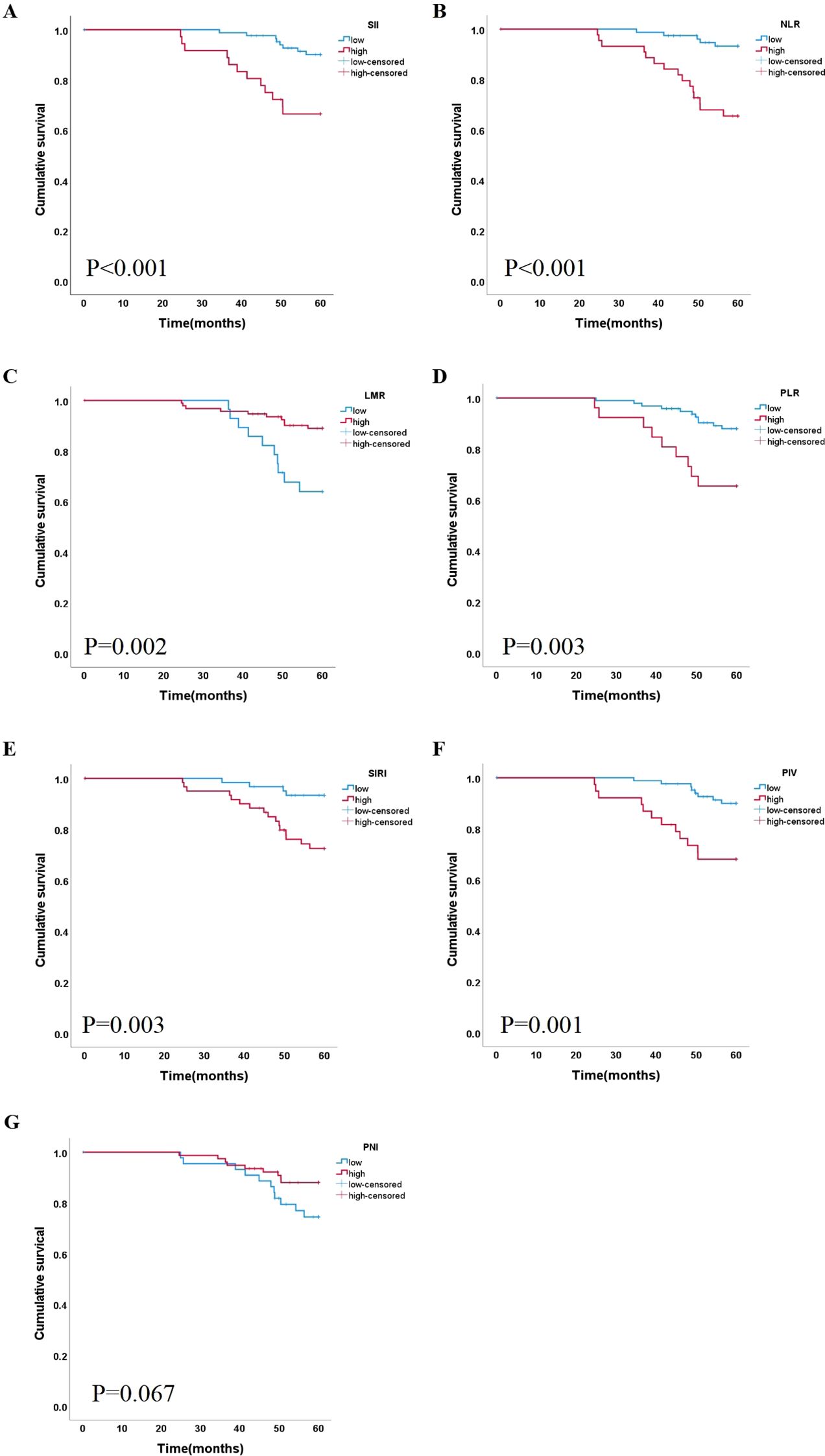

A Kaplan–Meier curve was used in the survival analyses of the different inflammation indices. Figure 2 shows that the cumulative survival rate in patients with a lower SII, NLR, PLR, SIRI, and PIV was better than that in other patients (P<0.050). In the group of NLR ≥2.134, survival was negatively correlated with NLR values. The high LMR group exhibited a superior survival rate compared to the low LMR group (P<0.050), Only the groups of PNI had no significant difference in cumulative survival rate.

Figure 2. Correlation between the level of 7 indicators and lip cancer survival. Kaplan-Meier curves based on inflammation markers (A) SII, (B) NLR (C) LMR, (D) PLR, (E) SIRI, (F) PIV and (G) PNI SII, systemic immune/inflammatory response index calculated by multiplying platelets by neutrophils and divided by lymphocytes; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; PIV, pan-immune-inflammation value; PNI, prognosis nutritional index.

During follow-up, 16 (13.11%) patients had disease recurrence, and 20 (16.39%) patients died. Descriptive data are presented in Table 1. These variables were identified as independent predictors using univariate and multivariate analyses.

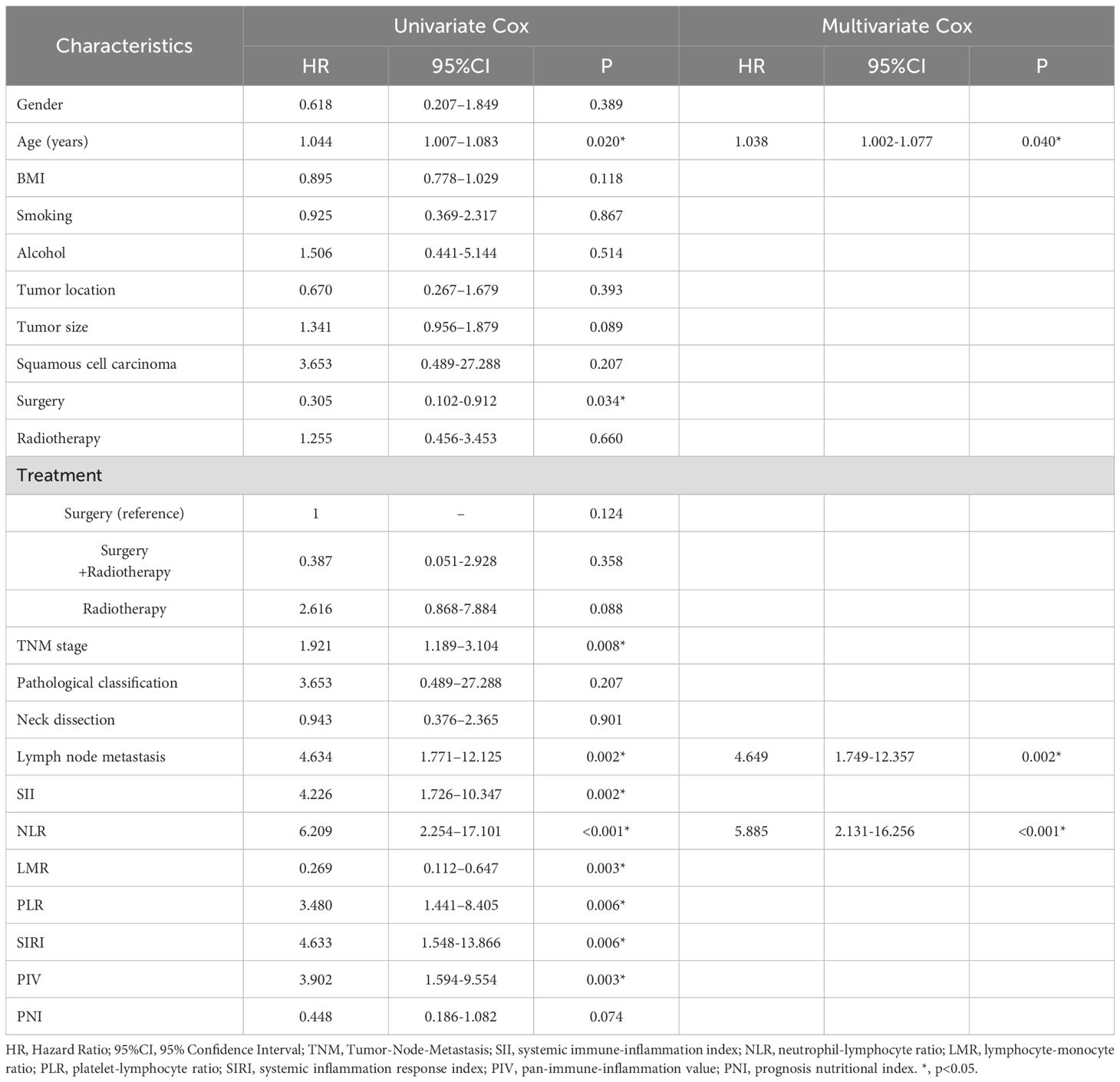

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that age (HR=1.044, 95% CI: 1.007-1.083, P=0.020), TNM stage (HR=1.921, 95% CI: 1.189-3.104, P=0.008), Surgery (HR=0.305, 95% CI: 0.102-0.912, P=0.034) and lymph node metastases (HR=4.634, 95% CI: 1.771-12.125, P=0.002) were all associated with lower survival rates. The inflammation indices in our study, SII (HR=4.226, 95% CI: 1.726-10.347, P=0.002), NLR (HR=6.209, 95% CI: 2.254-17.101, P<0.001), and PLR (HR=3.480, 95% CI: 1.441-8.405, P=0.006), LMR (HR=0.269, 95% CI: 0.112-0.647, P =0.003), SIRI (HR=4.633, 95% CI: 1.548-13.866, P=0.006), PIV (HR=3.902, 95% CI: 1.594-9.554, P=0.003),were all factors associated with lower overall survival (Table 4).

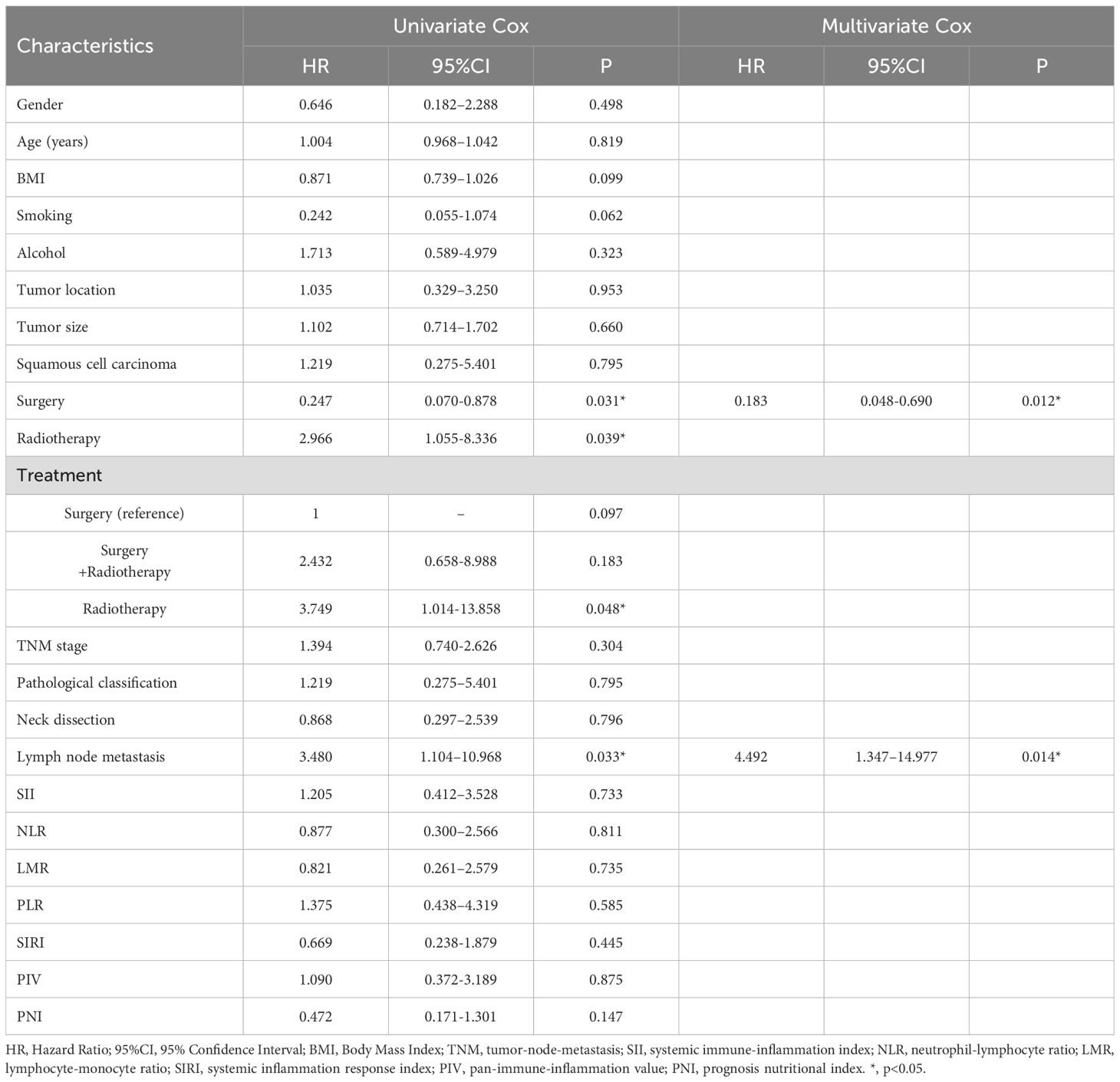

A multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to assess whether these parameters were independent predictors of overall survival (Table 4). The Age (HR=1.038, 95% CI: 1.002-1.077, P=0.040), lymph node metastases (HR=4.649, 95% CI: 1.749-12.357, P=0.002), and NLR (HR=5.324, 95% CI: 1.928-14.701, P<0.001) were shown to have a cumulative role in predicting overall survival. Furthermore, in the analysis of disease recurrence, both surgery (HR=0.183, 95% CI: 0.048-0.690, P =0.012) and lymph node metastases (HR=4.492, 95% CI: 1.347-14.977, P =0.014) were identified as significant factors. However, none of the inflammatory indices showed a significant association with recurrence in the multivariate analysis (Table 5).

4 Discussion

Peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers have demonstrated the prognostic significance in different diseases. Elevated inflammatory responses in the tumor microenvironment consistently correlating with poorer clinical outcomes (19). These biomarkers not only show significant associations with patient prognosis but also serve as independent prognostic factors in multiple cancer type (20), including lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma (21), and liver cancer (22). Inflammation indices have been established as predictors of carcinogenesis and disease progression in head and neck malignancies. However, most prior studies focused on the larynx, tongue, and oral cavity, our study presents an extensive analysis of systemic indices and their link to unfavourable prognosis in lip cancer, a topic not previously reported. The findings reveal correlations between peripheral blood inflammatory markers and both poor survival outcomes and disease recurrence in lip cancer patients. Furthermore, we systematically evaluate composite biomarkers including SIRI, PIV and PNI to elucidate the synergistic impacts of immune dysregulation, systemic inflammation, and nutritional status on disease progression. This multidimensional analysis provides novel insights into the correlation between host inflammatory responses and lip cancer outcomes.

The indices SII, NLR, PLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV and PNI were associated with poor overall survival in the univariate analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves in our study demonstrated that SII, NLR, PLR, SIRI, and PIV were positively correlated with poor prognosis in lip cancer, while LMR showed a negative correlation. Blood inflammatory biomarkers have better prognostic value than nutrition-related index. These biomarkers are closely linked to the inflammatory-immune imbalance within TME. Low LMR or elevated NLR reflects lymphocytopenia, indicating impaired immune surveillance that leads to insufficient CD8+ T cell responses against tumor-specific antigens. Additionally, a high MLR may be associated with monocyte differentiation into M2-polarized macrophages, which suppress local immune activity through TGF-β secretion and promote the maintenance of cancer stem cell-like phenotypes. Lip cancer likely sustains a low-grade inflammatory state in the TME, resulting in persistently elevated PBIBs. This chronic inflammation further activates pro-survival genes via the NF-κB signaling pathway, exacerbating therapeutic resistance (23). Collectively, these mechanisms elucidate the independent prognostic value of PBIBs for survival outcomes in lip cancer and provide a theoretical foundation for future precision therapies targeting inflammatory pathways.

But, in the multivariate analysis, only NLR was significantly correlated with poor prognosis (P <0.001). This study shows that NLR has independent prognostic value in lip cancer, which is consistent with previous research on other head and neck cancers (24). Most of these studies have shown that a high NLR in cancer patients is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in cancer patients (25, 26). This study demonstrated that the optimal cutoff value of NLR was 2.134, which was lower than that in many studies on head and neck cancer (27). This discrepancy may reflect distinct pathophysiological characteristics of lip cancer, including its unique ultraviolet-induced inflammatory patterns and fundamentally different tumor immune microenvironment (26, 28).

Elevated NLR signifies neutrophilia (pro-inflammatory state) and lymphopenia (immunosuppression), mirroring a tumor microenvironment (TME) skewed toward tumor progression. Neutrophils, the most abundant leukocyte in the innate immune system, originate from myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, have a short lifespan but are highly active (8). The homeostasis of neutrophil numbers is finely regulated by positive and negative feedback signals. In cancer, this balance can be disrupted, the number of neutrophils in peripheral blood is often elevated. Within the tumor microenvironment, neutrophils release ROS/RNS, which can damage DNA bases and promote tumor growth. They also secrete various cytokines (e.g., OSM, TGF-β) and chemokines (e.g., IL17, CXCR2 ligands) in response to different stimuli, thereby driving tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression (29, 30).

During the metastatic process, neutrophils promote tumor progression through stage-specific mechanisms: in the early stage, they secrete proteases to enhance tumor cell invasive capabilities; in the intermediate stage, they support tumor cell survival and immune evasion; and in the late stage, they accumulate in the pre-metastatic niche and release factors to stimulate tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis (29). Elevated neutrophil counts correlate with worse prognosis, forming the basis of NLR. Lymphocytes, conversely, mediate antitumor immunity by inhibiting tumor proliferation and migration. Reduced lymphocyte counts impair immune surveillance, further worsening outcomes (31).

Furthermore, we found that all the inflammatory markers were associated with neutrophils. The effect of neutrophils on various inflammatory indicators and their important roles in prognosis have also been demonstrated. Therefore, the effect of neutrophils on oral cancer, especially lip cancer, may be an issue that we need to explore further.

However, lip cancer is often caused by UV exposure, leading to unique molecular and inflammatory features compared to HNCs linked to HPV or tobacco use (32). This may explain why other PBIBs, like SII and PIV, are less predictive in lip cancer. In lip cancer, UV-induced neutrophil infiltration and oxidative stress boost NLR’s prognostic importance, while in HPV-negative HNCs or tobacco - related cases, PD-L1 driven T-cell exhaustion or platelet activation makes other PBIBs more clinically relevant. Previous research on the association of these indicators with OSCC prognosis has been inconclusive, and our findings revealed no significant statistical difference (13, 33–35). Therefore, whether we can use all these inflammatory indicators (except NLR) to build a prediction model for cancer requires further research.

Therefore, if the above indices can be reasonably used to increase the sensitivity and specificity of the prediction model, tumor prognosis can be better evaluated. We hypothesized that the combined inflammatory index might be helpful in determining adverse risks in patients with lip cancer and has an important role in predicting cancer-free survival.

In this study, we also analyzed the association between disease recurrence and inflammation indices and found no significant differences between the two groups. Lip cancer recurrence was only affected by operation and lymph node metastasis status in the multivariate analysis. Therefore, we concluded that these parameters derived from the peripheral blood were not suitable predictors of disease recurrence. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to verify the effects of inflammatory indices on recurrence.

As a retrospective cohort study, our analysis has inherent limitations. While univariate analysis identified SII, LMR, PLR, SIRI, and PIV as predictors of poor overall survival, these indices lost significance in multivariate models, likely due to collinearity with clinical variables or insufficient statistical power from the limited sample size. The retrospective design also introduces potential selection bias and restricts control over confounding factors. We explicitly state that while treatment heterogeneity exists, our statistical analysis did not find it to be a significant confounder in this specific study, thereby strengthening the independent prognostic value of the inflammatory biomarkers we identified. Finally, although lymph node metastasis is a well-established negative prognostic factor, NLR retained its independent prognostic significance even after the exclusion of node-positive (N+) patients, thereby further corroborating our conclusions. Nonetheless, the relatively small number of N+ patients (n=13) limits a more granular analysis of the interaction between inflammatory biomarkers and nodal disease burden, which should be explored in larger, future studies. Furthermore, the lack of standardized cutoff values for inflammatory markers (NLR, SIRI) across studies complicates clinical translation, as thresholds often vary between populations.

To address these limitations, future multicenter, prospective studies with larger cohorts are essential to validate the prognostic utility of PBIBs and establish universal cutoff criteria. Integrating PBIBs with tumor-specific molecular profiling (e.g., PD-L1 status, TP53 mutations) or radiomic features could enhance risk stratification models by improving sensitivity and specificity. Mechanistic investigations should focus on longitudinal monitoring of PBIBs during treatment to clarify their role in predicting therapeutic resistance, while experimental models (e.g., in vitro or animal studies) could explore interventions targeting inflammation-immune crosstalk, such as TGF-β or IL-6/STAT3 pathway inhibition, to improve clinical outcomes in lip cancer.

5 Conclusions

In the present study, the inflammation index demonstrated predictive power for unfavourable prognosis. A significant association was observed between an increased NLR and increased mortality in patients with lip cancer. The clinical utility of NLR lies in its cost-effectiveness, routine accessibility, and reproducibility, making it a practical tool for risk stratification in resource-limited settings. While other peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (SII, PLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV, PNI) demonstrated prognostic potential in univariate analyses, their predictive strength requires validation in larger prospective cohorts. These findings advocate for the integration of NLR into standard prognostic workflows for lip cancer, while underscoring the need for multicenter studies to harmonize cutoff values and explore combinatorial models incorporating molecular biomarkers to refine precision oncology strategies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Shanxi Cancer Hospital (KY2024048). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from Tumor Sample Center of Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. ZY: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. LG: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. JW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. HY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202403021221256), Scientific Research Project of Shanxi Provincial Health Commission (Grant No. 2024100), Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (Grant No.202103021224374).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. (2022). Available online at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html.

2. Lang K, Akbaba S, Held T, El Shafie R, Farnia B, Bougatf N, et al. Retrospective analysis of outcome and toxicity after postoperative radiotherapy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lip. Tumori. (2022) 108:125–33. doi: 10.1177/0300891621996805

3. da Silva Souto AC, Vieira Heimlich F, Lima de Oliveira L, Bergmann A, Dias FL, Spindola Antunes H, et al. Epidemiology of tongue squamous cell carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. Oral Dis. (2023) 29:402–10. doi: 10.1111/odi.13897

4. Saggi S, Badran KW, Han AY, Kuan EC, and St John MA. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes in floor of mouth squamous cell carcinoma: A population-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2018) 159:51–8. doi: 10.1177/0194599818756815

5. Machiels JP, Rene Leemans C, Golusinski W, Grau C, Licitra L, Gregoire V, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2020) 31:1462–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.011

6. Mantovani A. The inflammation - cancer connection. FEBS J. (2018) 285:638–40. doi: 10.1111/febs.14395

7. Dai M and Sun Q. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in patients with oral cancer: a meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY). (2023) 15:1615–27. doi: 10.18632/aging.204576

8. Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, and de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:431–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52

9. Ma C, Fu Q, Diggs LP, McVey JC, McCallen J, Wabitsch S, et al. Platelets control liver tumor growth through P2Y12-dependent CD40L release in NAFLD. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:986–98.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.08.004

10. Bakhshi P, Nourizadeh M, Sharifi L, Nowroozi MR, Mohsenzadegan M, and Farajollahi MM. Impaired monocyte-derived dendritic cell phenotype in prostate cancer patients: A phenotypic comparison with healthy donors. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). (2024) 7:e1996. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1996

11. Wang X, Gao H, Zeng Y, and Chen J. A Mendelian analysis of the relationships between immune cells and breast cancer. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1341292. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1341292

12. Toffoli EC, van Vliet AA, Verheul HWM, van der Vliet HJ, Tuynman J, Spanholtz J, et al. Allogeneic NK cells induce monocyte-to-dendritic cell conversion, control tumor growth, and trigger a pro-inflammatory shift in patient-derived cultures of primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer. (2023) 11:e007554. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-007554

13. Mariani P, Russo D, Maisto M, Troiano G, Caponio VCA, Annunziata M, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic factor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. (2022) 51:39–51. doi: 10.1111/jop.13264

14. Abbate V, Barone S, Troise S, Laface C, Bonavolontà P, Pacella D, et al. The combination of inflammatory biomarkers as prognostic indicator in salivary gland Malignancy. Cancers. (2022) 14:5934. doi: 10.3390/cancers14235934

15. Troise S, Di Blasi F, Esposito M, Togo G, Pacella D, Merola R, et al. The role of blood inflammatory biomarkers and perineural and lympho-vascular invasion to detect occult neck lymph node metastases in early-stage (T1-T2/N0) oral cavity carcinomas. Cancers. (2025) 17:1305. doi: 10.3390/cancers17081305

16. Ye M and Zhang L. Correlation of prognostic nutritional index and systemic immune-inflammation index with the recurrence and prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma with the stage of III/IV. Int J Gen Med. (2024) 17:2289–97. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S458666

17. Shi X, Li H, Xu Y, Nyalali AMK, and Li F. The prognostic value of the preoperative inflammatory index on the survival of glioblastoma patients. Neurol Sci. (2022) 43:5523–31. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06158-w

18. Chen Q, Wang SY, Chen Y, Yang M, Li K, Peng ZY, et al. Novel pretreatment nomograms based on pan-immune-inflammation value for predicting clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1399047. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1399047

19. Bruno M, Bizzarri N, Teodorico E, Certelli C, Gallotta V, Pedone Anchora L, et al. The potential role of systemic inflammatory markers in predicting recurrence in early-stage cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2024) 50:107311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.107311

20. Jensen HK, Donskov F, Marcussen N, Nordsmark M, Lundbeck F, and von der Maase H. Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2009) 27:4709–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9498

21. Bilen MA, Rini BI, Voss MH, Larkin J, Haanen J, Albiges L, et al. Association of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio with Efficacy of First-Line Avelumab plus Axitinib vs. Sunitinib in Patients with Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Enrolled in the Phase 3 JAVELIN Renal 101 Trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2022) 28:738–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1688

22. Geh D, Leslie J, Rumney R, Reeves HL, Bird TG, and Mann DA. Neutrophils as potential therapeutic targets in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2022) 19:257–73. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00568-5

23. Maniaci A, Giurdanella G, Chiesa Estomba C, Mauramati S, Bertolin A, Lionello M, et al. Personalized treatment strategies via integration of gene expression biomarkers in molecular profiling of laryngeal cancer. J Pers Med. (2024) 14:1048. doi: 10.3390/jpm14101048

24. Rodrigo JP, Sanchez-Canteli M, Triantafyllou A, de Bree R, Makitie AA, Franchi A, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:802. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030802

25. Du S, Fang Z, Ye L, Sun H, Deng G, Wu W, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the benefit of gastric cancer patients with systemic therapy. Aging (Albany NY). (2021) 13:17638–54. doi: 10.18632/aging.203256

26. Chen S, Guo S, Gou M, Pan Y, Fan M, Zhang N, et al. A composite indicator of derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and lactate dehydrogenase correlates with outcomes in pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:951985. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.951985

27. Mirestean CC, Stan MC, Iancu RI, Iancu DPT, and Badulescu F. The prognostic value of platelet-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)-A retrospective single center study and a literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). (2023) 13:3396. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13223396

28. Zeng Z, Chew HY, Cruz JG, Leggatt GR, and Wells JW. Investigating T cell immunity in cancer: achievements and prospects. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22062907

29. Wu L, Saxena S, and Singh RK. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2020) 1224:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-35723-8_1

30. Singh N, Baby D, Rajguru JP, Patil PB, Thakkannavar SS, and Pujari VB. Inflammation and cancer. Ann Afr Med. (2019) 18:121–6. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_56_18

31. Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, Sebban C, Le Cesne A, Judson I, et al. Treatment of Cancer Soft and G. Bone Sarcoma, Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:5383–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845

32. Toprani SM and Kelkar Mane V. A short review on DNA damage and repair effects in lip cancer. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. (2021) 14:267–74. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2021.01.007

33. Takenaka Y, Oya R, Kitamiura T, Ashida N, Shimizu K, Takemura K, et al. Platelet count and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Meta-analysis. Head Neck. (2018) 40:2714–23. doi: 10.1002/hed.25366

34. Wang J, Wang S, Song X, Zeng W, Wang S, Chen F, et al. The prognostic value of systemic and local inflammation in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. (2016) 9:7177–85. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S113307

35. Ruiz-Ranz M, Lequerica-Fernandez P, Rodriguez-Santamarta T, Suarez-Sanchez FJ, Lopez-Pintor RM, Garcia-Pedrero JM, et al. Prognostic implications of preoperative systemic inflammatory markers in oral squamous cell carcinoma, and correlations with the local immune tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:941351. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.941351

Keywords: lip cancer, peripheral blood inflammatory biomarker (PBIB), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), prognostic factors, survival outcomes

Citation: Li Z, An W, Wang B, Yan Z, Gao L, Wang J, Yu H and Wen S (2025) Prognostic significance of peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (SII, PLR, NLR, LMR, SIRI, PIV, PNI) in lip cancer: NLR as an independent biomarker for survival outcomes. Front. Oncol. 15:1676824. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1676824

Received: 31 July 2025; Accepted: 03 October 2025;

Published: 21 October 2025.

Edited by:

Alberto Rodriguez-Archilla, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Francesca Piccotti, Scientific Clinical Institute Maugeri (ICS Maugeri), ItalyStefania Troise, University of Naples Federico II, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Li, An, Wang, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yu and Wen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuxin Wen, d2Vuc3hzeEAxNjMuY29t; Hongmei Yu, eXVAc3htdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Zhilin Li1,2†

Zhilin Li1,2† Liangbin Gao

Liangbin Gao Hongmei Yu

Hongmei Yu Shuxin Wen

Shuxin Wen