- 1Thoracic Oncology, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 2Department of Biostatistics, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, United States

- 3Department of Bioinformatics, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, United States

- 4Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, United States

- 5Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, United States

- 6Division of Individualized Cancer Management, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, United States

- 7Department of Thoracic Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, United States

Background: Oncogenic BRAF mutations affect ~4% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Class I mutations (i.e., V600) are typically responsive to BRAF/MEK inhibitors, while non-Class I are often resistant. The role of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as first-line therapy in BRAF-mutant NSCLC remains unclear.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed patients with BRAF-mutant NSCLC treated at Moffitt Cancer Center from January 1, 2012, to August 9, 2023. Demographics, biomarker (e.g., PD-L1, molecular profile), and treatment data were collected. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using standardized real-world endpoints.

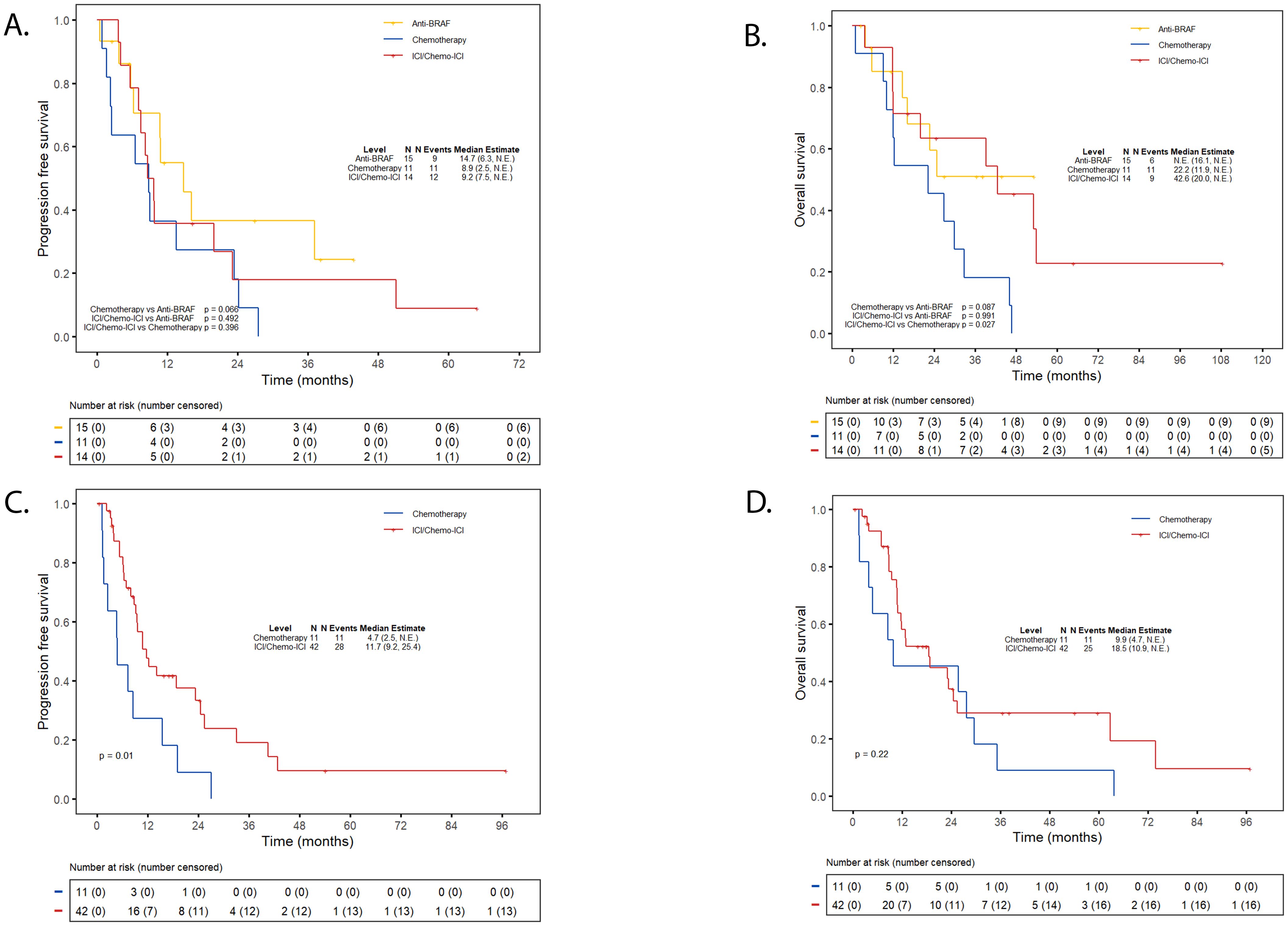

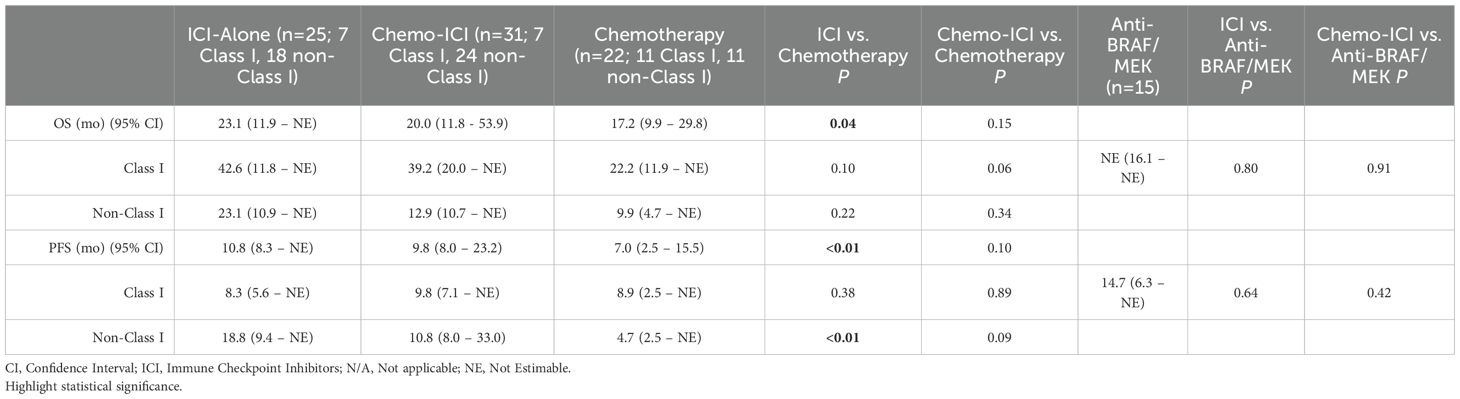

Results: Among 122 individuals, 54 had Class I and 68 had non-Class I mutations. For Class I mutations, ICIs yielded a PFS of 9.2 months and OS of 42.2 months, representing a significant OS advantage over chemotherapy-alone (22.2 months; p = 0.03). Outcomes were comparable to those seen with anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (PFS 14.7 months; p = 0.49, OS NE; p = 0.99), while ICIs trended towards improved OS in those with PD-L1 ≥50% (53.1 vs. 24.8 months; p = 0.61). For non-Class I mutations, ICI benefit was more limited (PFS 11.7 months, OS 18.5 months) yet compared favorably to chemotherapy-alone (PFS 4.7 months; p = 0.01; OS 9.9 months; p = 0.22). No patients with non-Class I mutations received anti-BRAF/MEK therapy.

Conclusion: ICIs appear effective in BRAF mutant-NSCLC. For Class I mutations, ICIs yielded significant survival benefit over chemotherapy-alone. Outcomes were comparable to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, with a potential survival advantage favoring ICIs in those with PD-L1 ≥50%. For non-Class I mutations, ICIs benefit was more modest but compared favorably to chemotherapy-alone.

1 Introduction

Oncogenic BRAF mutations affect 8% of solid malignancies and 4% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1, 2). BRAF mutations upregulate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK –or– RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK) signaling pathway causing uncontrolled cell proliferation and growth (2, 3). BRAF mutations can be categorized into Class I and non-Class I based on the kinase activity, dependency on RAS, and dimerization status (4). Class I mutations (i.e., V600) form potent RAS-independent monomers that can be targeted with BRAF inhibitors. Class II and III mutations, on the other hand, lead to intermediate-potency RAS-independent dimers and low-potency RAS-dependent dimers, respectively (4, 5). BRAF inhibitors have limited activity against BRAF dimerization signaling and are ineffective for most non-Class I mutations (6–8).

Class I and non-Class I BRAF mutations occur at similar rates in NSCLC, especially in North America and Europe, but most therapeutic efforts have focused on individuals with Class I mutations (9–11). Anti-BRAF/MEK therapies (i.e., dabrafenib/trametinib or encorafenib/binimetinib) improve survival for Class I BRAF-mutant NSCLC and are recommended for frontline use by clinical guidelines (12–14). These recommendations are, however, based on clinical trials that lacked comparator arms for other standard-of-care therapies, and included therapy-naïve and therapy-resistant populations (12–15). Further, the most effective frontline regimens for non-Class I BRAF-mutant NSCLC have not been fully elucidated (16).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have improved the outcomes for many NSCLC subtypes, but their role in BRAF-mutant NSCLC remains poorly defined (17). This is likely a result of the limited representation of these mutations in clinical trials. Retrospective and prospective studies suggest that frontline ICIs improve outcomes, but the study heterogeneity and sampling bias towards Class I mutations, limit definitive conclusions (18–23). We conducted a retrospective analysis to evaluate the role of frontline ICIs in advanced BRAF-mutant NSCLC compared to anti-BRAF/MEK agents and chemotherapy, hoping to assist in clinical decision-making and optimize treatment strategies for these patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients, 18 years of age or older, with NSCLC harboring an oncogenic BRAF mutation treated at Moffitt Cancer Center between January 1, 2012, and August 9, 2023. The oncogenic classification of each BRAF mutation (i.e., Class I, II, III) was defined based on prior literature and data from the OncoKB™ database (4, 24). Mutations lacking clear oncogenic function or classified as neutral, were categorized as variants of unknown significance (VUS). An internal electronic database containing tumor genomic and pyrosequencing data for all treated patients, identified eligible individuals. Data were collected for individuals with de-novo Class I and non-Class I BRAF mutations through electronic medical record review. Individuals with incomplete clinical information, acquired BRAF mutations (e.g., arising from use of targeted therapies against other oncogenes – EGFR or ALK –), or those with BRAF amplifications or VUS only, were excluded. Demographic information (i.e., sex, self-reported race/ethnicity, tobacco use, age at diagnosis) and disease-specific information (i.e., mutation type, histology, stage, tumor programmed-death ligand 1 [PD-L1] expression, central nervous system [CNS] involvement at presentation) were collected in all eligible individuals. Staging was calculated using the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM classification (25). In those with advanced or metastatic disease receiving at least one cycle of palliative systemic therapy, treatment details (i.e., agents, date of initiation and completion, number of cycles, reason for discontinuation) and outcomes datapoints were collected.

This study was conducted with appropriate regulatory measures and was approved by the scientific review committee and the institutional review boards (IRB) at Moffitt Cancer Center (Approval: MCC 19335; August 14, 2023). Informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

2.2 Genomic profiling and PD-L1 testing

Genomic data were retrieved from the internal database containing results from different platforms including immunohistochemistry, next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays from both commercial and in-house platforms (e.g., liquid-based [FoundationOne Liquid CDx, Guardant] and tissue-based tests [FoundationOne CDx, Moffitt STAR]), pyrosequencing (Moffitt Pyrosequencing), mass spectrometry-based assays (MassARRAY), and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping (SNaPshot).

PD-L1 expression was assessed using the recommended procedure for commercially available IHC tests VENTANA PD-L1 (SP263) and PD-L1 IHC 22C3 PharmDx (26). PD-L1 was reported as tumor proportion score (TPS). Positivity was defined as TPS ≥1%, and high expression as ≥50%.

2.3 Outcomes

Outcomes analysis was pursued in those with advanced/metastatic disease receiving at least one cycle of either ICI-based therapy, anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, or chemotherapy-alone. Individuals treated under clinical trials or treated with other systemic therapies were excluded from outcomes analysis. Treatment response was assessed by the investigators and defined as the best documented clinical and/or radiographic response reported in the medical record. Responses were categorized using standardized real-world endpoints (27, 28). Complete response (CR) was defined as a reported complete resolution of disease by the treating clinician or radiographic report. Partial response (PR) was defined as a documented partial reduction in the disease burden or clinical improvement. Stable disease (SD) was defined as no significant clinical or radiographical change. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as an increase in disease burden, appearance of new lesions, or clinical progression deemed by the treating physician. Real-world progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from initiation of first-line systemic therapy until PD, death, or lost to follow-up. Real-world overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from initiation of first-line systemic therapy until death from any cause or end of follow-up. Those without PD, death, or lost to follow-up were censored at the most recent encounter.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. For continuous variables, mean, median, and ranges were reported. Comparisons between groups were made using either t-test or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions. Group comparisons were made using Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and subgroups differences were assessed through log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A p value of ≤0.05 was defined as significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software version 4.4.2.

3 Results

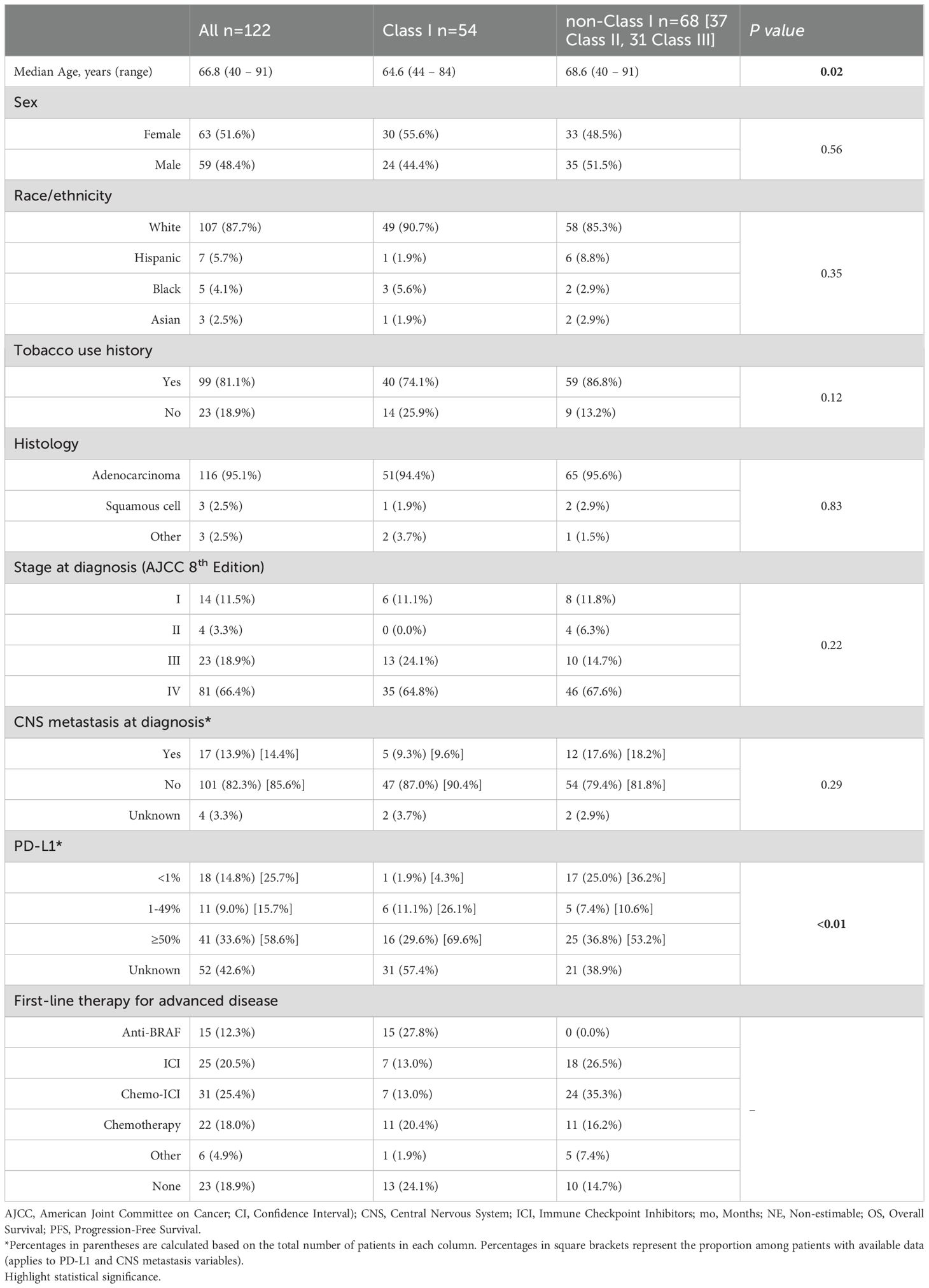

We identified 122 patients with BRAF-mutant NSCLC: 54 Class I, 37 Class II, and 31 Class III mutations (Table 1). The median age was 67 years (range 40 – 91). Those with BRAF Class I NSCLC were slightly younger than non-Class I (65 vs. 69 years; p = 0.02). Females made up 52% of the entire cohort, while most males (60%) had non-Class I mutations. Up to 88% of patients self-identified as White. Over 95% had adenocarcinoma and 85% had at least stage III disease at presentation. CNS involvement was present at diagnosis in 21% of individuals with stage IV disease (17/81), the majority of whom harbored non-Class I mutations (12/17; 71%). History of tobacco use was common (81%), but never-smokers were disproportionately represented among Class I mutations (61%).

3.1 PD-L1 levels

There were 70 patients with PD-L1 testing available of which 52 (74%) had a TPS ≥1%. Those with Class I mutations were more likely to have PD-L1 expression ≥1% (96% vs. 64%) and ≥50% (70% vs. 53%) compared to those with non-Class I mutations (p < 0.01).

3.2 Molecular landscape

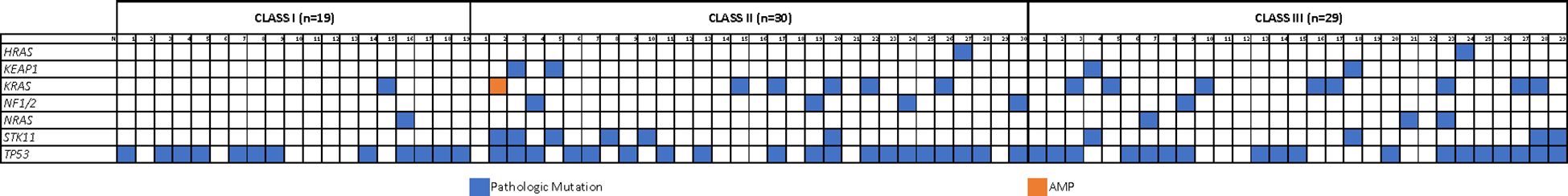

BRAF mutations were detected on NGS for most patients (81%), while other detection methods (i.e., pyrosequencing, genotyping) were less common (Supplementary Table 1S). Because NGS platforms identified specific BRAF variants and other co-mutations, the mutational landscape analysis was limited to individuals with available NGS data.

In those with Class I mutations on NGS, all had a V600E variant (n=32) and 63% (n=19) harbored additional pathogenic mutations. TP53 was the most common (n=12/19; 63%) while other co-mutations were rare (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1S). In patients with non-Class I mutations on NGS, the most common BRAF variants were G469X (n=18; 28%), N581X (n=8; 12%), D594X (n=8; 12%), G466X (n=7; 11%), and K601X (n=6; 9%) (Supplementary Table 2S). Among these individuals, 91% (n=59) had additional pathogenic mutations, including TP53 (n=37/59; 63%), RAS (n=19/59; 32% - KRAS 24%, NRAS 5%, HRAS 3%), STK11 (n=10/59; 17%), NF1 (n=5/59; 8%), and KEAP1 (n=4/59; 7%) (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1S). While concurrent EGFR alterations were identified in a small subset of patients with Class I (n=5) and non-Class I (n=9) BRAF mutations, only a minority harbored sensitizing variants and received anti-EGFR therapy, suggesting that most EGFR co-mutations were not clinically actionable (Supplementary Table 3S).

Figure 1. Mutational landscape. OncoMap showing the genomic distribution for different co-mutations according to BRAF mutation class.

3.3 Clinical outcomes: real world progression-free survival and overall survival

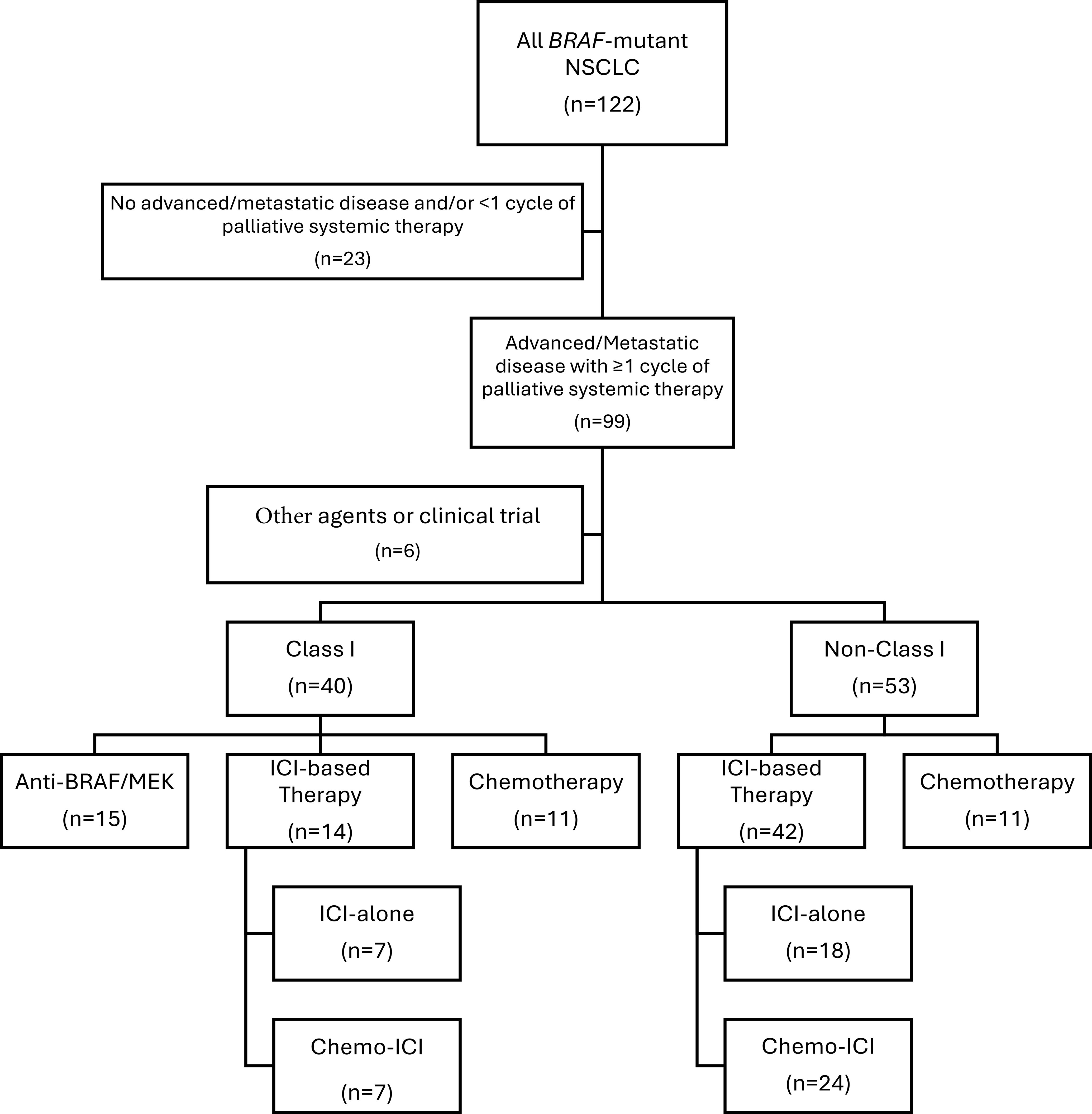

Among the 122 patients, 99 had advanced/metastatic disease treated with at least one cycle of palliative systemic therapy. Of these, 56 received frontline ICI-based therapies including 25 ICI-alone (7 Class I, 7 Class II, 11 Class III) and 31 chemo-ICI (7 Class I, 12 Class II, 12 Class III). Fifteen patients received anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (all Class I) and 22 received chemotherapy-alone (11 Class I, 6 Class II, 5 Class III). Six patients (1 Class I, 4 Class II, 1 Class III) were treated with clinical trial or other targeted agents and were excluded from the outcomes analysis (Figure 2) (Supplementary Table 3S).

Figure 2. Diagram of evaluable population. CONSORT Flow Diagram depicting individuals eligible for outcomes evaluation according to therapy. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

In patients with Class I mutations, the efficacy of ICI-based therapies was comparable to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy and conferred a survival advantage over chemotherapy. Specifically, the median PFS with ICI/chemo-ICI was similar to chemotherapy (9.2 vs. 8.9 months; p = 0.40) and not significantly different than anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (14.7 months; p = 0.49) (Figure 3A). However, the median OS was significantly longer with ICI/chemo-ICI than with chemotherapy (42.6 vs. 22.2 months; p = 0.03) and not significantly different compared to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (not estimable [NE]; p=0.99) (Figure 3B). In those treated with frontline ICI/chemo-ICI, subsequent treatments included anti-BRAF/MEK inhibitors (43%; n=6/14), other ICI-based regimens (14%; n=2/14), or chemotherapy (14%; n=2/14). For those treated with frontline anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, subsequent therapies included ICI-based treatments (15%; n=3/15) and chemotherapy (7%; n=1/15), while 60% (n=9/15) received no additional treatments. In the chemotherapy group, 27% (n=3/11) received additional chemotherapy, 27% (n=3/11) received ICI-based therapy, 9% (n=1/11) received anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, 9% (n=1/11) were enrolled in clinical trials, and 27% (n=3/11) received no additional therapy (Supplementary Table 4S).

Figure 3. Progression-free survival and overall survival first-line immunotherapy. (A) PFS ICI/chemo-ICI vs. targeted therapy or chemotherapy in class (I) (B) OS ICI/chemo-ICI vs. targeted therapy or chemotherapy in class (I) (C) PFS ICI/chemo-ICI vs. chemotherapy in non-class (I) (D) OS ICI/chemo-ICI vs. chemotherapy in non-class (I) Kaplan Meier Curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) for individuals with class I BRAF mutations treated with frontline ICI-based therapy compared to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy or chemotherapy-alone (A) Overall survival (OS) for individuals with class I treated with frontline ICI-based therapy compared to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy or chemotherapy-alone (B) PFS for individuals with non-class I mutations treated with frontline ICI-based therapy compared to chemotherapy-alone (C) OS for individuals with non-class I mutations treated with frontline ICI-based therapy compared to chemotherapy-alone (D) ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NE, Not Estimable.

For non-Class I patients, treatment with ICI/chemo-ICI was associated with a significantly better PFS compared to chemotherapy (11.7 vs. 4.7 months; p = 0.01), and a non-significant trend toward improved OS (18.5 vs. 9.9 months; p = 0.22) (Figures 3C, D). For those treated with frontline ICI/chemo-ICI, subsequent therapies included anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (5%; n=2/42), a different ICI-based treatment (7%; n=3/42), and chemotherapy (14%; n=6/42) while the majority (67%; n=28/42) received no additional treatment. Subsequent therapies for those treated with frontline chemotherapy included additional chemotherapy (9%, n=1/11), ICI-based therapy (45%; n=5/11), and 36% (n=4/11) received no further therapy (Supplementary Table 4S).

We found no significant differences in outcomes between individuals with Class I and non-Class I treated with ICI/chemo-ICI or chemotherapy (Supplementary Figure 2S).

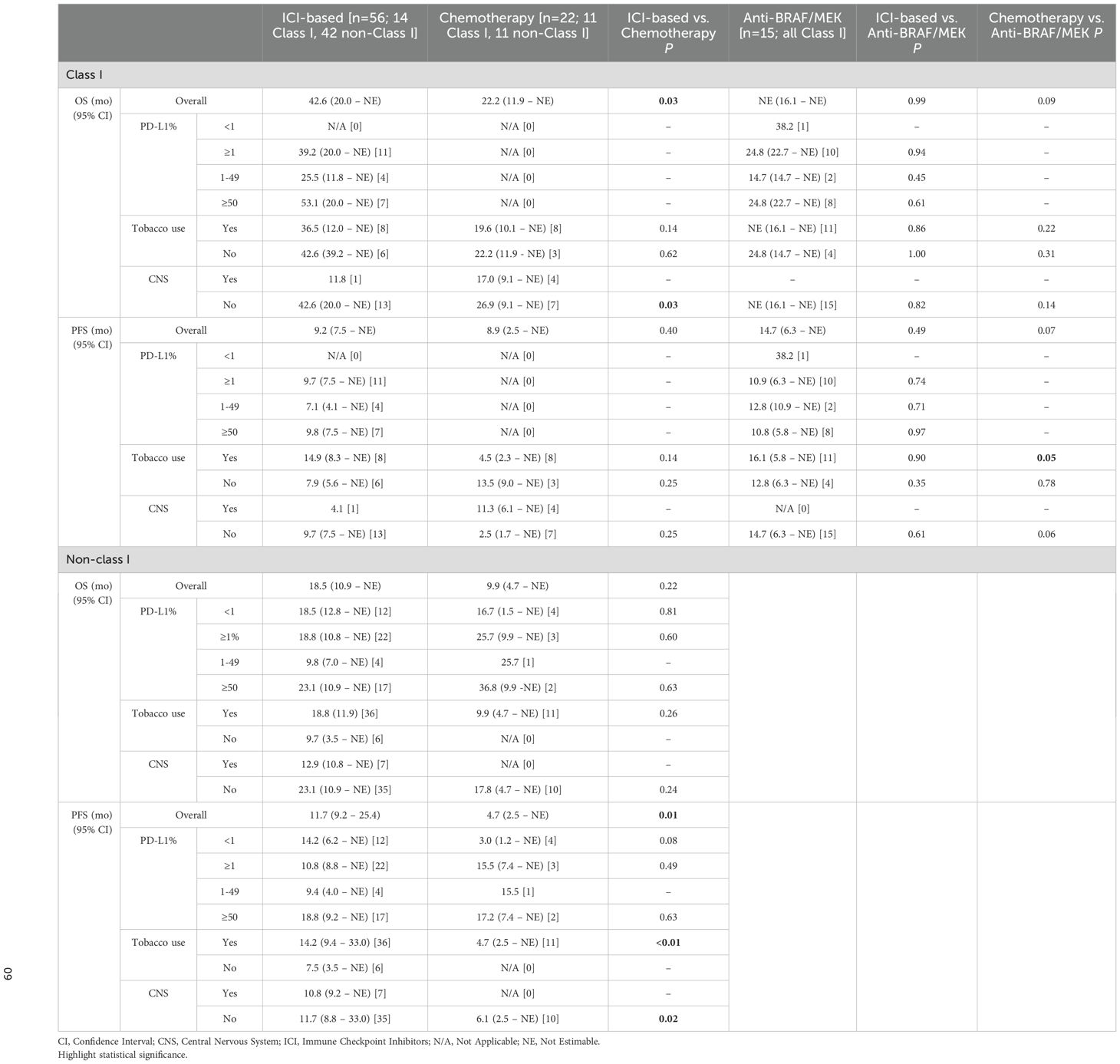

3.4 Exploratory subgroup analyses

3.4.1 PD-L1 levels

For individuals with Class I mutations and PD-L1 ≥1% (n=21), both ICI-based and anti-BRAF/MEK therapies yielded comparable outcomes (Table 2). There was a trend towards improved OS with higher PD-L1 levels in those treated with ICI-based therapy. This was particularly striking for individuals with TPS ≥50% (n=7) (53.1 vs. 24.8 months; p=0.61). While no statistical significance was achieved, this finding suggests that individuals with Class I mutations and high PD-L1 expression could derive clinically relevant long-term benefit from ICI-based therapy. Only 1 patient with Class I mutation had PD-L1 <1%, thus no formal analysis was pursued between treatment arms.

The sample size was limited for patients with non-Class I mutations and PD-L1 ≥1% (n=25), thus no meaningful differences were seen between ICI-based therapies and chemotherapy. Specifically, individuals with PD-L1 ≥50% treated with ICI/chemo-ICI (n=17) or chemotherapy (n=2) had similar PFS (18.8 vs. 17.2 months; p = 0.63) and OS (23.1 vs. 36.8 months; p = 0.63). In contrast, patients with PD-L1 <1% (n=12) had surprisingly longer PFS (14.2 vs. 3.0 months; p = 0.08) and OS (18.5 vs. 16.7 months; p = 0.81) compared to chemotherapy (n=4). While this could suggest that ICI-based therapy could be more effective in this subgroup, the number of patients limits definitive conclusions.

3.4.2 ICI-alone and chemo-ICI

An analysis among those treated with ICI-based therapies demonstrated that ICI-alone (n=25) was associated with significantly improved PFS (10.8 vs. 7.0 months; p < 0.01) and OS (23.1 vs. 17.2 months; p = 0.04) compared to chemo-ICI (n=31). This difference is likely confounded by imbalances in PD-L1 expression between the groups. Up to 89% (n=16/18) of patients receiving ICI-alone had PD-L1 ≥50% compared to 30% (n=8/27) in the chemo-ICI group.

For patients with Class I mutations, outcomes with ICI-alone (n=7) or chemo-ICI (n=7) were comparable to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (n=15) and trended toward improved OS relative to chemotherapy (n=11) (Table 3, Supplementary Figure 3S). Conversely, in patients with non-Class I mutations ICI-alone was associated with greater benefit than chemo-ICI. Specifically, ICI-alone (n=18) led to a significant improvement in PFS compared to chemotherapy (n=11) (18.8 vs. 4.7 months; p < 0.01). This was not seen with chemo-ICI (n=24) (10.8 months; p=0.09) (Supplementary Figure 3S). This finding could also have resulted from the higher PD-L1 expression within the ICI-alone versus the chemo-ICI subgroup (PD-L1 ≥50%: 93% [n=13/14] vs. 20% [n=4/20], respectively).

Table 3. Outcomes with ICI-alone or chemo-ICI compared to chemotherapy-only and anti-BRAF/MEK therapy.

3.4.3 Tobacco use

Tobacco use seemed to influence outcomes in patients treated with ICI-based therapies (Table 2). Never-smokers (n=12) demonstrated significantly shorter PFS compared to tobacco users (n=44) in the overall cohort (7.9 vs. 14.2 months; p = 0.04, Supplementary Figure 4S). This trend persisted within the Class I subgroup (7.9 vs. 14.9 months; p = 0.14). In contrast, OS was numerically more favorable among never-smokers, both in the overall cohort (39.2 vs. 20.0 months; p = 0.84, Supplementary Figure 4S) and within the Class I subgroup (42.6 vs. 36.5 months; p = 0.90). Never-smokers with Class I mutations (n=6) also trended towards improved OS with ICI/chemo-ICI compared to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (n=4) (24.8 months; p = 1.00) or chemotherapy (n=3) (22.2 months; p = 0.62). These differences, however, did not reach statistical significance likely due to the limited cohort size.

In patients with non-Class I mutations, tobacco users treated with ICI-based therapies (n=36) showed a trend towards improved PFS (14.2 vs. 7.5 months; p = 0.07) and OS (18.8 vs. 9.7 months; p = 0.07) compared to never-smokers (n=6). Tobacco users also had significantly better PFS (14.2 vs. 4.7 months; p<0.01), and numerically higher OS (18.8 vs. 9.9 months; p = 0.26) compared to those treated with chemotherapy (n=11).

3.4.4 CNS involvement

Given the limited number of patients with CNS involvement, formal comparisons across treatment arms were not feasible. In those treated with ICI-based therapies (n=8), however, OS was significantly shorter for patients with CNS involvement (12.4 months) than without CNS involvement (24.6 months; p = 0.05; Supplementary Figure 5S, Supplementary Table 5S). In patients without CNS involvement, ICI-based therapies were particularly beneficial for individuals with Class I mutations (n=13). PFS and OS in this subgroup (9.7 and 42.6 months, respectively) were comparable to those observed with anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (n=15) (PFS 14.7 months, p = 0.61; OS NE, p = 0.86) while OS was significantly improved compared to chemotherapy (n=7) (26.9 months; p = 0.03). In those with non-Class I mutations and no CNS involvement, the benefit of ICI/chemo-ICI (n=35) was less pronounced. PFS however, remained significantly longer compared to chemotherapy (n=10) (11.7 vs. 6.1 months; p=0.02) and OS showed a non-significant trend toward improvement (23.1 vs. 17.8 months; p=0.24) (Table 2).

4 Discussion

This study represents one of the largest single-institution analyses to-date evaluating the role of frontline ICI-containing regimens across all subclasses of BRAF-mutant NSCLC in North America. Our findings support previous reports where individuals with BRAF-mutant NSCLC derived meaningful clinical benefit from ICI-based regimens (20, 22, 23, 29).

For individuals with Class I mutations, current guidelines recommend frontline anti-BRAF/MEK therapy based on the survival benefit seen in clinical trials (12–14). These therapies, however, are associated with substantial toxicities (i.e., rash, fever, diarrhea, reduced ejection fraction, retinopathy) that may limit their use and impact quality of life. Further, individuals with melanoma and Class I mutations experience better survival with frontline ICI-based therapy than anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, raising questions about the optimal treatment sequencing in NSCLC (16, 30–33). In our study, ICI-based regimens led to survival outcomes that were comparable to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy. This aligns with clinical trial and real-world data reporting a PFS of 10.5 – 18.5 months and OS of 28.0 – 43.3 months for ICI-based therapy, versus PFS of 10.8 – 30.2 months and OS of 17.3 – NE for anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (12, 14, 16, 19, 22, 23, 34–36). In our cohort, we also noticed a clinically meaningful trend favoring OS with ICIs in those with PD-L1 ≥50% (53.1 vs 24.8 months; p = 0.61), but the study was underpowered for a definitive conclusion. Patients treated with chemotherapy-alone, on the other hand, experienced significantly worse OS compared to those receiving ICI/chemo-ICI (p = 0.03) and trended towards inferior OS compared to anti-BRAF/MEK therapy (p = 0.09). While these OS differences could reflect confounding factors from subsequent therapies in each cohort, previous studies reported that chemotherapy has limited efficacy in patients with Class I BRAF-mutant NSCLC (1). Taken together, our results suggest that frontline ICIs offer a viable alternative to targeted therapy in individuals with Class I BRAF-mutant NSCLC, particularly in those whose PD-L1 expression is elevated. This may be especially relevant given real-world data suggesting that the efficacy of anti-BRAF/MEK therapy may be preserved beyond the frontline setting (37, 38). Randomized studies are needed to confirm these observations, especially given the conflicting data on PD-L1 expression and ICI outcomes for Class I mutations (18, 22, 23).

Individuals with non-Class I mutations present a greater therapeutic challenge. These mutations confer intrinsic resistance to many BRAF-inhibitors as a result of RAS-independent dimerization (4, 39). Consistent with existing literature, no patients with non-Class I mutations in our cohort received anti-BRAF therapy while outcomes with chemotherapy-alone were poor (1). ICI-based therapies, however, improved PFS and trended towards better OS compared to chemotherapy. These findings support current guideline recommendations and expert opinions favoring ICI incorporation for individuals with non-Class I-mutant NSCLC (13, 19, 20, 40–42). Our findings also support the potential of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker of ICI-response in this population (18). For instance, patients treated with ICI-only appeared to outperform those with chemo-ICI, likely reflecting a higher prevalence of PD-L1 ≥50% in those treated with ICI-only. Patients with PD-L1 levels <1% treated with ICI-based therapies also experienced improved survival compared to chemotherapy-alone, suggesting that chemotherapy may have limited – if not detrimental – effects in non-Class I BRAF mutations. These observations are speculative and should be interpreted with caution due to the limited sample size.

An intriguing finding was the survival advantage observed in Class I over non-Class I for individuals treated with ICIs. This differs from reports where survival between both groups was either comparable or favored non-Class I mutations (18, 20, 43). We believe several factors contributed to this discrepancy. First, 60% of individuals in our cohort exhibited high PD-L1 levels ≥1%, which contrasts with the 23% seen in the general NSCLC population (44). Further, PD-L1 ≥1% was more common in Class I (96%) compared to non-Class I mutations (64%), and higher PD-L1 levels correlated with improved outcomes. This suggests that BRAF-mutant NSCLC, particularly those with Class I and higher PD-L1, may be more responsive to ICIs compared to other oncogene-driven NSCLCs (i.e., EGFR or ALK) (18, 45–49). Second, non-Class I mutations were frequently associated with STK11, KEAP1, and RAS family gene alterations (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS). These co-mutations have been previously reported in this population, reflect independent RAS activation, and negatively impact ICIs response (50–53). Dual ICI therapy has been proposed as a strategy to mitigate the negative effects of STK11/KEAP1 mutations and may be a potential therapeutic approach for patients with non-Class I BRAF mutations with concurrent STK11/KEAP1 mutations (54). Third, clinical and demographic differences may have played a role. While our cohort was representative of other North American populations (high proportion of White individuals; no significant association between BRAF mutation Class and sex, histology, or stage), patients with Class I mutations were slightly younger than non-Class I (1, 9, 11, 50). This may have positively impacted ICI responses in patients with Class I mutations (55). Additionally, Class I mutations were more common in never-smokers, and never-smokers have better outcomes among NSCLC with targetable mutations (11, 56). Conversely, tobacco use appeared to correlated with improved outcomes in patients with non-Class I mutations treated with ICIs. We hypothesize that high tobacco exposure may have led to an increased PD-L1 expression resulting in enhanced ICI response (57). Finally, CNS involvement was more prevalent in non-Class I patients. This may have negatively impacted outcomes (50, 58).

Our study has several limitations. Its retrospective, single-institution design limits generalizability. The 11-year study period may have introduced confounders resulting from evolving treatment standards. Self-reported data on ethnicity and tobacco use, as well as provider-documented outcomes, may be subject to bias. Subgroup analyses were mainly exploratory given the small sample size and limited interpretation. Finally, the observed differences between ICI-alone and Chemo-ICI were likely influenced by selection bias as patients with more aggressive disease may have preferentially received chemo-ICI (59).

This study also has important clinical implications for patients with newly diagnosed, advanced, BRAF-mutant NSCLC. First, ICI-based therapy appears to be a viable frontline option for patients with Class I mutations, particularly those in whom there is concern about the toxicity from targeted therapies or in those whose PD-L1 levels are ≥50%. The prolonged OS observed in this subgroup compared with anti-BRAF/MEK therapy, although not statistically significant, suggests a potential clinically meaningful benefit in long-term outcomes that warrants confirmation in prospective studies. PD-L1 also appeared to be a useful predictive marker in our cohort, but its role remains unclear and warrants validation in larger clinical trials. Second, in individuals with non-Class I mutations, ICI-based therapy should be considered the backbone of treatment given the lack of benefit observed with chemotherapy-alone. Finally, a comprehensive assessment of the genomic landscape is key, since the presence of co-mutations like STK11 or KEAP1 may negatively impact ICI response and affect treatment selection (e.g., dual over single ICI regimen).

5 Conclusion

Our findings suggest that ICI-based therapies are an effective treatment option for BRAF-mutant NSCLC. In patients with Class I mutations, ICIs appear at least comparable to anti-BRAF/MEK therapies and could provide superior outcomes in patients with high PD-L1 expression. Among non-Class I mutations, ICIs are promising but their benefit seems more limited, likely reflecting a lower PD-L1 expression, a more aggressive co-mutational landscape, and increased rates of CNS involvement. Prospective studies should clarify the predictive role of PD-L1 in BRAF-mutant NSCLC, directly compare ICIs and anti-BRAF/MEK therapy in Class I mutations and identify optimal strategies for treating non-Class I mutations such as intensified or combination ICI strategies in those with STK11/KEAP1 co-alterations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted with appropriate regulatory measures and was approved by the scientific review committee and the institutional review boards (IRB) at Moffitt Cancer Center (Approval: MCC 19335; August 14, 2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Author contributions

JM-A: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RT: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. D-TC: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used generative AI technologies to improve readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflict of interest

JH is a paid consultant for ARUP, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Jackson Laboratories. JG is a paid consultant for AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Coherus, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Eli Lilly, EMD Serono – Merck KGaA, Gilead Sciences, GO2 for Lung Cancer, IDEOlogy Health, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Spectrum ODAC, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Triptych Health Partners/Catalyst Pharmaceuticals, Zai Lab US LL. Research support to institution from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono – Merck KGaA, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GO2 for Lung Cancer, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Panbela Therapeutics, Inc., Pfizer, and Regeneron. SP is paid consultant for G1 therapeutics, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Janssen, Novocure, Oncohost, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda. Spouse is a paid consultant for AbbVie and Intuitive Surgical. Research support to institute from ORIC and Janssen.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work the authors used generative AI technologies to improve readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1681119/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Cardarella S, Ogino A, Nishino M, Butaney M, Shen J, Lydon C, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and biologic features associated with BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2013) 19:4532–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0657

2. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. (2002) 417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766

3. Cantwell-Dorris ER, O’Leary JJ, and Sheils OM. BRAFV600E: implications for carcinogenesis and molecular therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. (2011) 10:385–94. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0799

4. Dankner M, Rose AAN, Rajkumar S, Siegel PM, and Watson IR. Classifying BRAF alterations in cancer: new rational therapeutic strategies for actionable mutations. Oncogene. (2018) 37:3183–99. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0171-x

5. Haling JR, Sudhamsu J, Yen I, Sideris S, Sandoval W, Phung W, et al. Structure of the BRAF-MEK complex reveals a kinase activity independent role for BRAF in MAPK signaling. Cancer Cell. (2014) 26:402–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.007

6. Karoulia Z, Gavathiotis E, and Poulikakos PI. New perspectives for targeting RAF kinase in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2017) 17:676–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.79

7. Negrao MV, Raymond VM, Lanman RB, Robichaux JP, He J, Nilsson MB, et al. Molecular landscape of BRAF-mutant NSCLC reveals an association between clonality and driver mutations and identifies targetable non-V600 driver mutations. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:1611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.05.021

8. Okimoto RA, Lin L, Olivas V, Chan E, Markegard E, Rymar A, et al. Preclinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor that evades paradoxical MAPK pathway activation in protein kinase BRAF-mutant lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2016) 113:13456–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610456113

9. Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, Sima CS, Miller VA, Kris MG, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. (2011) 29:2046–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280

10. Tissot C, Couraud S, Tanguy R, Bringuier PP, Girard N, and Souquet PJ. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. Lung Cancer. (2016) 91:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.11.006

11. Litvak AM, Paik PK, Woo KM, Sima CS, Hellmann MD, Arcila ME, et al. Clinical characteristics and course of 63 patients with BRAF mutant lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. (2014) 9:1669–74. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000344

12. Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, Hashemi SMS, Mazieres J, Kim TM, et al. Phase 2 study of dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic NSCLC: updated 5-year survival rates and genomic analysis. J Thorac Oncol. (2022) 17:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.011

13. Oncology NCPGi. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), NCCN. Version 3.2025 — January 14, 2025 (2025). Available online at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2025).

14. Riely GJ, Ahn MJ, Clarke JM, Dagogo-Jack I, Esper R, Felip E, et al. Updated Efficacy and safety from the phase 2 PHAROS study of encorafenib plus binimetinib in patients with BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic NSCLC–A brief report. J Thorac Oncol. (2025) 20:1538–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2025.05.023

15. Mazieres J, Cropet C, Montane L, Barlesi F, Souquet PJ, Quantin X, et al. Vemurafenib in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with BRAF(V600) and BRAF(nonV600) mutations. Ann Oncol. (2020) 31:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.022

16. Planchard D, Sanborn RE, Negrao MV, Vaishnavi A, and Smit EF. BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic NSCLC: disease overview and treatment landscape. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2024) 8:90. doi: 10.1038/s41698-024-00552-7

17. Zimmermann S, Peters S, Owinokoko T, and Gadgeel SM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of lung cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. (2018) 38:682–95. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_201319

18. Dudnik E, Peled N, Nechushtan H, Wollner M, Onn A, Agbarya A, et al. BRAF mutant lung cancer: programmed death ligand 1 expression, tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability status, and response to immune check-point inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. (2018) 13:1128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.024

19. Gibson AJW, Pabani A, Dean ML, Martos G, Cheung WY, and Navani V. Real-world treatment patterns and effectiveness of targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor-based systemic therapy in BRAF mutation-positive NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. (2023) 4:100460. doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100460

20. Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, Mhanna L, Cortot AB, Mezquita L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:1321–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz167

21. Provencio M, Robado de Lope L, Serna-Blasco R, Nadal E, Diz Tain P, Massuti B, et al. BRAF mutational status is associated with survival outcomes in locally advanced resectable and metastatic NSCLC. Lung Cancer. (2024) 194:107865. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107865

22. Di Federico A, Chen MF, Pagliaro A, Ogliari FR, Stockhammer P, Aldea M, et al. 1299P First-line immunotherapy versus BRAF and MEK inhibitors for patients with BRAF V600E mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. (2024) 35:S826–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.08.1356

23. Wiesweg M, Alaffas A, Rasokat A, Saalfeld FC, Rost M, Assmann C, et al. Treatment sequences in BRAF-V600-mutated NSCLC: first-line targeted therapy versus first-line (Chemo-) immunotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. (2025) 20:1328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2025.04.016

24. Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. (2017) 2017:1–16. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00011

25. Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD, and Rusch VW. Lung cancer - major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. (2017) 67:138–55. doi: 10.3322/caac.21390

26. Lantuejoul S, Sound-Tsao M, Cooper WA, Girard N, Hirsch FR, Roden AC, et al. PD-L1 testing for lung cancer in 2019: perspective from the IASLC pathology committee. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:499–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.107

27. Ma X, Bellomo L, Magee K, Bennette CS, Tymejczyk O, Samant M, et al. Characterization of a real-world response variable and comparison with RECIST-based response rates from clinical trials in advanced NSCLC. Adv Ther. (2021) 38:1843–59. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01659-0

28. Stewart M, Norden AD, Dreyer N, Henk HJ, Abernethy AP, Chrischilles E, et al. An exploratory analysis of real-world end points for assessing outcomes among immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2019) 3:1–15. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00155

29. Negrao M, Skoulidis F, Montesion M, Schulze K, Bara I, Shen V, et al. MA03.05 BRAF mutations are associated with increased benefit from PD1/PDL1 blockade compared with other oncogenic drivers in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. (2019) 14:S257–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.514

30. Garutti M, Bergnach M, Polesel J, Palmero L, Pizzichetta MA, and Puglisi F. BRAF and MEK inhibitors and their toxicities: A meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 15:14. doi: 10.3390/cancers15010141

31. Jeng-Miller KW, Miller MA, and Heier JS. Ocular effects of MEK inhibitor therapy: literature review, clinical presentation, and best practices for mitigation. Oncologist. (2024) 29:e616–e21. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyae014

32. Mincu RI, Mahabadi AA, Michel L, Mrotzek SM, SChadendorf D, Rassaf T, et al. Cardiovascular adverse events associated with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e198890. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8890

33. Atkins MB, Lee SJ, Chmielowski B, Tarhini AA, Cohen GI, Truong TG, et al. Combination dabrafenib and trametinib versus combination nivolumab and ipilimumab for patients with advanced BRAF-mutant melanoma: the DREAMseq trial-ECOG-ACRIN EA6134. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:186–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01763

34. Auliac JB, Bayle S, Do P, Le Garff G, Roa M, Falchero L, et al. Efficacy of dabrafenib plus trametinib combination in patients with BRAF V600E-mutant NSCLC in real-world setting: GFPC 01-2019. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12:3608. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123608

35. Wang H, Cheng L, Zhao C, Zhou F, Jiang T, Guo H, et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2023) 12:219–29. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-613

36. Janzic U, Shalata W, Szymczak K, Dziadziuszko R, Jakopovic M, Mountzios G, et al. Real-world experience in treatment of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with BRAF or cMET exon 14 skipping mutations. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:12840. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612840

37. Couraud S, Barlesi F, Fontaine-Deraluelle C, Debieuvre D, Merlio JP, Moreau L, et al. Clinical outcomes of non-small-cell lung cancer patients with BRAF mutations: results from the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup biomarkers France study. Eur J Cancer. (2019) 116:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.016

38. Telli TA, Tatli AM, Alan O, Keskin GY, Karadurmus N, Karakaya S, et al. Real-world outcomes in BRAF-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter analysis from the turkish oncology group. Clin Lung Cancer. (2025) 26:e649–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2025.07.015

39. Dagogo-Jack I, Awad MM, and Shaw AT. BRAF mutation class and clinical outcomes-response. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:3189. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0422

40. Sholl LM. A narrative review of BRAF alterations in human tumors: diagnostic and predictive implications. Precis Cancer Med. (2020) 3:26. doi: 10.21037/pcm-2019-ppbt-02

41. Abuali I, Lee C-S, and Seetharamu N. A narrative review of the management of BRAF non-V600E mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Precis Cancer Med. (2022) 5:13. doi: 10.21037/pcm-21-49

42. Guisier F, Dubos-Arvis C, Vinas F, Doubre H, Ricordel C, Ropert S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC with BRAF, HER2, or MET mutations or RET translocation: GFPC 01-2018. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:628–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.129

43. Li H, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Huang Z, Cheng G, Xie M, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy efficacy in BRAF mutation non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. (2022) 13:1064. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05510-4

44. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:2018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824

45. Rihawi K, Giannarelli D, Galetta D, Delmonte A, Giavarra M, Turci D, et al. BRAF mutant NSCLC and immune checkpoint inhibitors: results from a real-world experience. J Thorac Oncol. (2019) 14:e57–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.036

46. Lisberg A, Cummings A, Goldman JW, Bornazyan K, Reese N, Wang T, et al. A phase II study of pembrolizumab in EGFR-mutant, PD-L1+, tyrosine kinase inhibitor naive patients with advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2018) 13:1138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.035

47. Sankar K, Nagrath S, and Ramnath N. Immunotherapy for ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: challenges inform promising approaches. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13:1476. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061476

48. Tang Y, Fang W, Zhang Y, Hong S, Kang S, Yan Y, et al. The association between PD-L1 and EGFR status and the prognostic value of PD-L1 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with EGFR-TKIs. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:14209–19. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3694

49. Yan N, Zhang H, Guo S, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Xu L, et al. Efficacy of chemo-immunotherapy in metastatic BRAF-mutated lung cancer: a single-center retrospective data. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1353491. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1353491

50. Dagogo-Jack I, Martinez P, Yeap BY, Ambrogio C, Ferris LA, Lydon C, et al. Impact of BRAF mutation class on disease characteristics and clinical outcomes in BRAF-mutant lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:158–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2062

51. Kazandjian S, Rousselle E, Dankner M, Cescon DW, Spreafico A, Ma K, et al. The clinical, genomic, and transcriptomic landscape of BRAF mutant cancers. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:445. doi: 10.3390/cancers16020445

52. Yao Z, Torres NM, Tao A, Gao Y, Luo L, Li Q, et al. BRAF mutants evade ERK-dependent feedback by different mechanisms that determine their sensitivity to pharmacologic inhibition. Cancer Cell. (2015) 28:370–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.001

53. Ricciuti B, Arbour KC, Lin JJ, Vajdi A, Vokes N, Hong L, et al. Diminished efficacy of programmed death-(Ligand)1 inhibition in STK11- and KEAP1-mutant lung adenocarcinoma is affected by KRAS mutation status. J Thorac Oncol. (2022) 17:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.10.013

54. Skoulidis F, Araujo HA, Do MT, Qian Y, Sun X, Cobo AG, et al. CTLA4 blockade abrogates KEAP1/STK11-related resistance to PD-(L)1 inhibitors. Nature. (2024) 635:462–71. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07943-7

55. Voruganti T, Soulos PR, Mamtani R, Presley CJ, and Gross CP. Association between age and survival trends in advanced non-small cell lung cancer after adoption of immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. (2023) 9:334–41. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.6901

56. Kerrigan K, Wang X, Haaland B, Adamson B, Patel S, Puri S, et al. Real world characterization of advanced non-small cell lung cancer in never smokers by actionable mutation status. Clin Lung Cancer. (2021) 22:260–7 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2021.01.013

57. Norum J and Nieder C. Tobacco smoking and cessation and PD-L1 inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a review of the literature. ESMO Open. (2018) 3:e000406. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000406

58. Ali A, Goffin JR, Arnold A, and Ellis PM. Survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after a diagnosis of brain metastases. Curr Oncol. (2013) 20:e300–6. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1481

Keywords: BRAF mutations, NSCLC, adenocarcinoma, smoking, driver mutations, PD-L1, immunotherapy, targeted therapy

Citation: Marin-Acevedo JA, Thapa R, Bandikatla SV, Chen D-T, Hicks JK, Gray JE and Puri S (2025) Outcomes with frontline immune checkpoint inhibitors among individuals with BRAF-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 15:1681119. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1681119

Received: 06 August 2025; Accepted: 21 November 2025; Revised: 07 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Chukwuka Eze, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, GermanyReviewed by:

Walid Shalata, Soroka Medical Center, IsraelDan Yan, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, United States

Copyright © 2025 Marin-Acevedo, Thapa, Bandikatla, Chen, Hicks, Gray and Puri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sonam Puri, c29uYW0ucHVyaUBtb2ZmaXR0Lm9yZw==

†These authors share senior authorship

Julian A. Marin-Acevedo

Julian A. Marin-Acevedo Ram Thapa2,3

Ram Thapa2,3 Dung-Tsa Chen

Dung-Tsa Chen J. Kevin Hicks

J. Kevin Hicks Jhanelle E. Gray

Jhanelle E. Gray Sonam Puri

Sonam Puri