- 1Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

- 2Medical Research Core Facility and Platforms Department, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 6King Abdulaziz Medical City, National Guard Health Affairs (NGHA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Department of Preclinical Studies, Benefit and Risk Assessment Executive Directorate, Drug Sector – Saudi Food and Drug Authority, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 8Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 9Wellness and Preventative Medicine Institute, Health Sector, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Metastasis is the primary cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. This narrative review integrates recent advances in the molecular circuits orchestrating metastatic progression, encompassing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), organotropism, extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, hypoxia-inducible signaling, tumor-cell migration modes, and tumor–immune interactions through expert-guided literature selection. We examined therapeutic innovations that disrupt these pathways, including EMT modulators, matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, VEGF/VEGFR-targeted regimens, hypoxia-activated prodrugs, and next-generation immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint blockade and chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Additionally, we discuss established nanotechnology-based delivery systems, advancing multi-omics integration, evolving single-cell analyses, and emerging CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing applications as tools for improving metastasis detection, monitoring, and treatment. Despite this progress, translational obstacles persist, particularly regarding intratumoral heterogeneity, adaptive resistance, and limited preclinical model fidelity. Addressing these challenges requires biomarker-guided, multi-target therapeutic combinations, interdisciplinary collaboration, and globally inclusive clinical trials. This evidence underscores the importance of integrated strategies that simultaneously target intrinsic tumor plasticity and microenvironmental support to transform metastatic cancer outcomes.

1 Introduction

Cancer metastasis is the process by which malignant tumor cells spread from their original sites to distant organs, resulting in secondary tumors. It accounts for approximately 90% of cancer-related deaths, rendering it a critical area of research and clinical focus (1). This complex, multi-step process, known as the metastatic cascade (Figure 1), involves local invasion, intravasation into the circulation, survival of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), extravasation, and colonization at secondary sites. Each step is intricately linked to various cellular and molecular mechanisms that dictate the behavior of cancer cells and their interactions with the surrounding environment (2). The invasion process begins when tumor cells lose their adhesion to neighboring cells, allowing them to break away from the primary tumor and invade surrounding tissues. This is accomplished through the degradation of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix (ECM), along with the regulation of proteins that control cell movement (3). After invasion, tumor cells undergo intravasation, penetrating the lymphatic or blood circulatory systems, and subsequently extravasation, where they enter new tissues to form secondary tumors (4). The ability of these cells to survive in the bloodstream, adapt to foreign microenvironments, and establish new growth at distant sites is influenced by multiple factors, including ECM composition and stiffness, which can promote or inhibit tumor progression (5). Moreover, the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a significant role in metastasis. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, and various growth factors interact with tumor cells, thereby altering their invasive capabilities and facilitating metastasis (6). For instance, CAFs can remodel the ECM, making it more permissive for tumor invasion and promoting further cancer progression through cytokine and matrix-degrading enzyme release (7). All these factors influence metastatic potential and therapy resistance.

Figure 1. The metastatic cascade refers to the sequence of events in which aggressive cancer cells detach from the original tumor, circulate through the bloodstream, and ultimately arrive at distant organs, where they can form one or more metastases. Created with BioRender.com.

Understanding these pathways is pivotal for identifying novel therapeutic targets and underpins emerging precision medicine strategies (8, 9). For example, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are central regulators of cell behavior and ECM remodeling, and their dysregulation facilitates invasion and metastasis (10). Advances in genomic and multi-omics profiling have clarified that metastasis is not a uniform process; distinct tumors and even separate metastatic lesions exhibit heterogeneous molecular signatures and unique organotropism patterns (11, 12). Consequently, personalized approaches that account for this diversity are increasingly necessary.

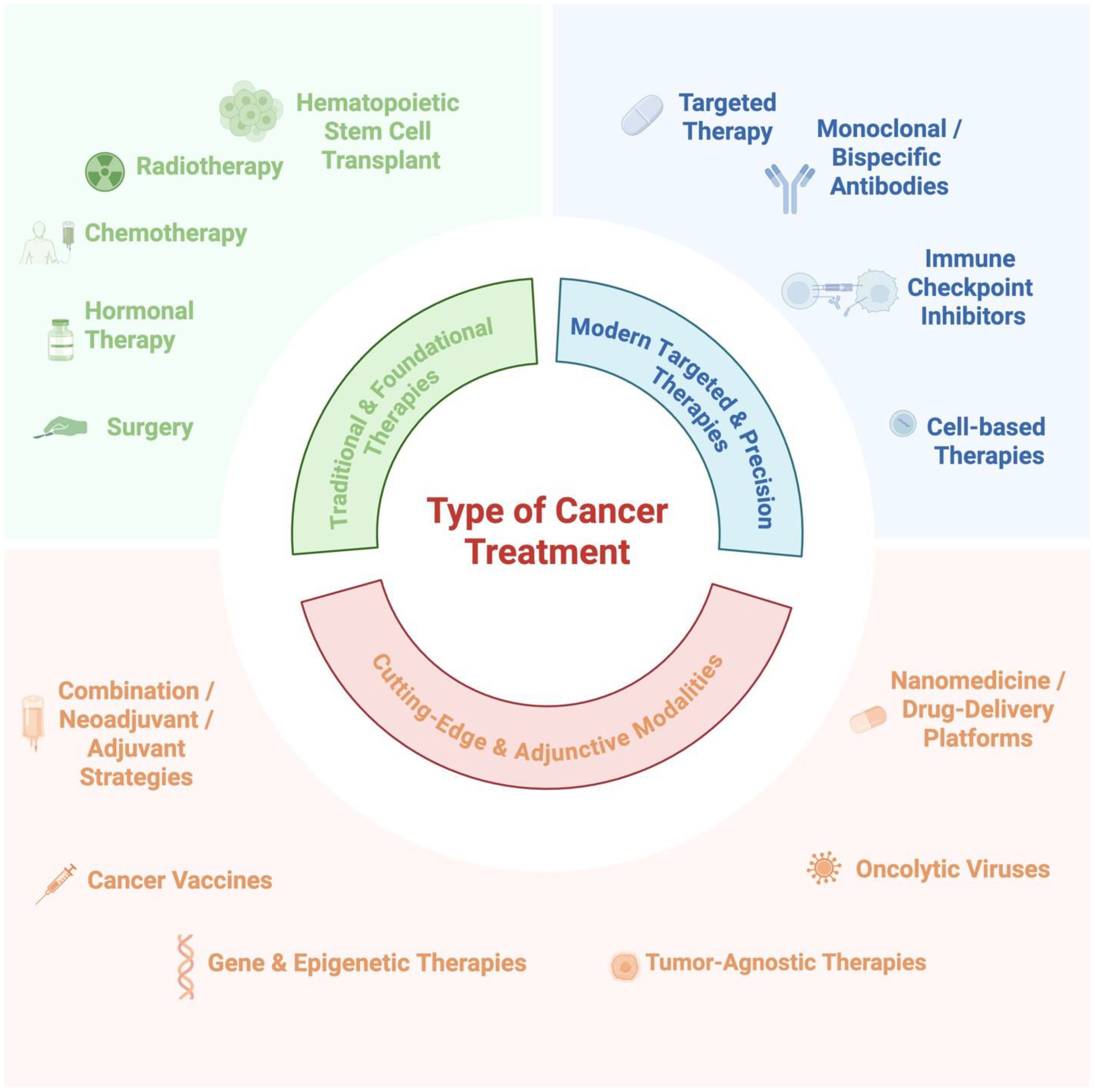

Traditional cancer therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy (Figure 2), have historically prioritized the reduction of the primary tumor bulk, often with limited effects on established or micrometastatic disease (13). while newer anti-cancer drugs, such as neutralizing antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors, often address metastasis only as a secondary effect. Newer classes of agents, such as migrastatics that target the migratory and invasive capacity of cancer cells, are promising but still require clinical validation (14). Integrating antimetastatic strategies with precise biomarkers detected through liquid biopsy and integrated multi-omics technologies is essential for real-time disease monitoring, individualized treatment, and improved outcomes (15, 16).

Figure 2. Available treatment options consist of traditional and foundational therapies, modern targeted and precision therapies, and cutting-edge and adjunctive modalities, among others. Created with BioRender.com.

Despite these advances, the field faces persistent challenges. Tumor heterogeneity complicates the identification of universal treatment regimens, as genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors result in variable therapeutic responses, resistance, and disease progression (13, 17–19). Furthermore, several antimetastatic therapies have failed in clinical trials due to inadequate efficacy or unanticipated toxicity (20, 21), often reflecting an incomplete understanding of metastatic biology and the influence of factors such as ECM composition, hypoxia, angiogenesis, and the immune system. Addressing these multifaceted obstacles requires multi-targeted therapeutic regimens that disrupt both the tumor-intrinsic and microenvironmental drivers of metastasis, supported by continued innovation in diagnostics and drug development. In this review, we critically examine the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying cancer invasion and metastatic progression and discuss recent and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways.

2 Key molecular pathways involved in cancer invasion and metastasis

2.1 Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a cellular mechanism by which epithelial cells lose specific epithelial features and gain mesenchymal traits, thereby increasing cell motility. EMT activation is essential in physiological settings for numerous embryonic developmental processes, such as gastrulation, neural crest development, cardiac valve formation, and wound healing (22). However, under pathological conditions, EMT is a pivotal contributor to organ fibrosis and is a critical process enabling cancer progression and metastasis, allowing epithelial tumor cells to disseminate from the primary site to distant organs (22–27). However, histological analyses of human carcinoma metastases have revealed that most distant lesions retain epithelial characteristics similar to the primary tumor, making it difficult to distinguish EMT-derived tumor cells from stromal cells (28–30). These observations fueled debate, particularly among pathologists, over whether EMT truly contributes to human metastasis. However, experimental models demonstrate that EMT activation enables dissemination, whereas mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET) at distant sites facilitates colonization and metastatic outgrowth (29–35). Research has shown that EMT is not a binary process but generates intermediate hybrid epithelial–mesenchymal (E/M) states, many of which do not progress to a fully mesenchymal phenotype (36, 37). While EMT confers invasive and migratory properties fundamental to embryonic development and cancer progression, in pathological contexts such as organ fibrosis, the program remains partial, producing hybrid E/M cells with limited migratory activity (38, 39). In cancer, however, hybrid E/M cells can be highly invasive and possess strong metastatic potential (40–42). These intermediate states are part of a broader concept termed epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity (EMP), which allows cancer cells to reversibly occupy position along the E/M spectrum. As illustrated in Figure 3, this plasticity enables dynamics switching between epithelial, mesenchymal, and hybrid phenotypes, conferring trait such as invasion, migration, immune evasion, and resistance. These intermediate states, together with EMT’s transient and plastic nature, underscore the nonlinear dynamics of this process. The ability of cancer cells to transition between epithelial, mesenchymal, and hybrid states is regulated by transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic mechanisms (43). A study using an inducible mouse model of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) found that switching on TWIST1 triggers EMT, aiding cancer cells to break away and enter the bloodstream. However, for these cells to settle in new organs and grow into large metastases, TWIST1 must be downregulated to stop the EMT process (33). Tran et al. reported similar findings in an inducible Snail1 mouse model of breast cancer (44). Collectively, these studies demonstrated that while TWIST1- or SNAI1-driven EMT is highly effective in promoting tumor invasion, bloodstream entry (intravasation), and exit at distant sites (extravasation), the reversal of MET is essential for the growth of metastases in distant organs. Reichert et al. found that the loss of p120-catenin (p120ctn) in a mouse model is sufficient to trigger EMT and enhance metastasis development. Interestingly, the loss of both p120ctn and E-cadherin appears to drive metastasis, specifically to the lungs, whereas their expression is necessary to enable MET and support metastasis in the liver (45). This indicates that EMT may play a role in determining the organ-specific spread of metastasis. Complementing EMT-promoting transcription factors, several metastasis suppressor genes (MSGs), such as CADM1, BRMS1, and KAI1/CD82, function to restrict metastatic dissemination without affecting primary tumor growth. For example, CADM1 enhances immune-mediated clearance of tumor cells and suppresses tumor invasiveness by modulating cell–cell adhesion and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity (46). BRMS1 impedes metastatic spread by repressing EMT-associated transcriptional networks, including NF-κB and Twist signaling, and by modulating chromatin remodeling complexes (47). KAI1/CD82, a member of the tetraspanin family, maintains epithelial adhesion by stabilizing E-cadherin at the plasma membrane and inhibiting cell motility and invasion (48). Loss or downregulation of these MSGs is frequently observed in aggressive tumors and correlates with poorer clinical outcomes, underscoring their critical roles as intrinsic molecular brakes on the metastatic cascade. In addition to EMT–MET dynamics, metastatic dormancy represents a critical barrier to long-term cancer control (49). Disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) can enter a quiescent state, often remaining undetectable for years before reactivating to form overt metastases (50). This dormant state is regulated by molecular signals such as p38 MAPK, TGF-β2, and BMP, as well as niche-derived cues that suppress proliferation and modulate immune evasion (49). Reactivation from dormancy—often triggered by inflammation or niche remodeling—is clinically associated with late relapse, particularly in breast and prostate cancers (50).

Figure 3. Epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) in cancer. Signals such as TGF-β, Wnt, Notch, and hypoxia induce EMT, generating hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M) states with mixed traits. These states enhance adaptability through invasion, migration, resistance, and immune evasion, while MET at distant sites supports metastatic colonization. Adapted from Kuburich et al. (2023), Semin Cancer Biol. Created with BioRender.com.

2.2 Organotropism

Different cancer types exhibit organ-specific metastasis patterns. Gastric, gallbladder, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers typically develop liver metastases before colonizing distant organs, such as the lungs. Breast cancer cells frequently disseminate to preferred metastatic sites, including the lungs, bone, brain, and liver, whereas prostate cancer cells primarily spread to bone (5, 51). The distribution of CTCs throughout the body is influenced by blood flow patterns. As the liver and lungs are among the first organs that CTCs reach, they frequently serve as primary sites of metastasis in many cancer types. Additionally, gaps in the liver and bone marrow sinusoids facilitate the extravasation of CTCs, contributing to a higher occurrence of metastases in these organs (52). Although anatomical characteristics contribute to the preferential spread of cancer to specific organs, they do not fully explain the nonrandom patterns observed in metastasis. The key mechanisms that drive organotropism include chemokine signaling, vascular niche formation, and immune interactions.

2.2.1 Chemokine signaling

Many studies have highlighted the significant role of chemokine signaling in organ-specific metastasis. The CCR7/CCL21 axis has been shown to drive lymph node metastasis in several cancers (53). Research has indicated that CCR7 expression correlates with increased lymphatic spread in esophageal SCC, reinforcing its role in tumor progression (54). Similarly, in gastric cancer, high CCR7 expression has been linked to metastasis to the regional lymph nodes, suggesting that targeting this pathway may be a potential strategy to limit disease dissemination (55). Another well-characterized chemokine axis, the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, plays a critical role in guiding cancer cells to the bone marrow, lungs, and liver, which are common metastatic sites for various tumors. Studies indicate that CXCL12 is highly expressed in these organs, creating a chemotactic gradient that attracts CXCR4-expressing tumor cells, thereby facilitating metastasis (56). These findings reinforce the importance of chemokine-driven organotropism in cancer metastasis and suggest that targeting these signaling pathways may provide novel therapeutic strategies for the prevention and management of metastatic diseases.

2.2.2 Vascular niche formation

The formation of pre-metastatic niches (PMNs) significantly influences organotropism during cancer metastasis. Primary tumor-release factors prepare distant organs for future metastasis by altering the local microenvironment. These alterations include ECM remodeling, increased vascular permeability, and recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells, creating a supportive niche for incoming tumor cells (57). For instance, cancer-derived exosomal miR-25-3p promotes PMN formation by inducing vascular permeability and angiogenesis (58). These pre-metastatic niches determine the organ-specific spread of metastasis, thereby influencing cancer cell organotropism (59). Vascular niche formation explains why cancer spreads to specific organs. This knowledge may result in the development of novel therapies that block supportive environments.

2.2.3 Immune interactions

Immune interactions play a pivotal role in organotropism and in the tendency of cancer cells to metastasize to specific organs. The dynamic interplay between tumor cells and the host immune system significantly influences the establishment and progression of metastasis. Emerging evidence suggests that tumor cells can recruit immune cells, which, in turn, promote tumor cell invasion, survival in circulation, and colonization of different organs (60). Additionally, the formation of a PMN, a microenvironment conducive to tumor cell colonization, is influenced by immune components. Primary tumors can modulate distant sites by recruiting bone marrow-derived cells and altering the local immune environment, thereby promoting organ-specific metastasis (61). Understanding these immune interactions is crucial for the development of therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating the immune system to prevent or treat organ-specific metastases.

Building upon the principles of organ-specific metastasis, the role of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) is pivotal in modulating both tumor cell detachment and intravasation and homing and colonization at distant sites.

2.3 Cell adhesion molecules and ECM remodeling in cancer metastasis

CAMs including cadherins, integrins, and selectins are crucial for tissue architecture and metastatic dissemination (62, 63). In epithelial cancers, loss of E-cadherin (the “cadherin switch” to N-cadherin) during EMT disrupts adherens junctions and enhances cell motility and invasiveness (62). Aberrant integrin expression (e.g., αvβ3 and α5β1) strengthens tumor cell attachment to the ECM and activates FAK/Src–PI3K/AKT signaling, driving migration through tissue barriers (63). In the bloodstream, selectins (E-, P-, and L-selectin) mediate rolling adhesion of CTCs on activated endothelium, a process analogous to leukocyte extravasation, thereby aiding tumor cell arrest and extravasation at distant sites (64). Dysregulation of these CAMs fuels metastasis: for example, reduced E-cadherin correlates with higher invasiveness and poor prognosis, while overactive integrins enhance survival and migration (62, 63). Integrin-dependent CAM–ECM interactions link CAM biology with dynamic ECM remodeling, which is pivotal for metastasis. Tumor-associated ECM undergoes extensive remodeling to facilitate invasion. Proteolytic enzymes such as MMPs are major drivers: MMP-2 and MMP-9 (gelatinases) degrade basement membrane type IV collagen and interstitial collagens, clearing paths for invading cells (65, 66). Elevated MMP-9 levels, for instance, are clinically associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival in breast cancer. ECM degradation not only removes physical barriers but also releases bound growth factors and bioactive matrikines that promote angiogenesis and further tumor growth (65, 66). Concurrently, enzymes like lysyl oxidase (LOX) crosslink collagen and elastin, increasing matrix stiffness. CAF- and tumor-derived TGF-β induces LOX expression in CAFs, leading to collagen crosslinking and a rigid ECM that paradoxically supports tumor cell migration and formation of PMN (66).

Aberrant ECM remodeling can also create a dense, fibrotic desmoplastic stroma that impedes treatment. In pancreatic and other tumors, massive collagen and hyaluronan deposition raise interstitial pressure and block drug delivery (67). A stiff matrix amplifies integrin signaling in cancer cells, further enhancing proliferation and survival. Non-malignant stromal cells amplify these effects: CAFs are key architects of the remodeled ECM. CAFs deposit new matrix proteins (e.g., collagens and fibronectin) and secrete growth factors (TGF-β, VEGF, PDGF, FGF2, and HGF) and cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, and CXCL12/SDF-1) that jointly reprogram the matrix and tumor behavior (66). For example, CAF-derived TGF-β activates LOX and fibronectin assembly, reinforcing a stiff, fibrillar ECM (66). CAFs also produce multiple MMPs (MMP-1, -2, and -9) to clear ECM barriers. These CAF–tumor interactions are now targeted therapeutically: agents against fibroblast activation protein (FAP) on CAFs (e.g., FAP-specific CAR-T cells or inhibitors) and inhibitors of CAF-derived signals (e.g., TGF-β or IL-6 blockade) are being explored to disrupt the tumor-supportive stroma (66, 68).

Immune cells within the TME further modulate the ECM. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) secrete MMPs and other proteases that degrade ECM and promote metastasis. Importantly, a rigid, collagen-rich matrix can skew immune cell function toward an immunosuppressive phenotype (69). For instance, stiff ECM promotes accumulation of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, creating barriers to immune infiltration and therapy. Thus, the reciprocal interplay of CAMs and ECM remodeling establishes a feed-forward loop driving invasion. Targeting this axis—for example, by LOX or integrin inhibitors, MMP modulators, or drugs that normalize ECM stiffness—is a promising strategy to limit metastatic spread and improve treatment outcomes (66, 69).

2.4 Hypoxia, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis in metastasis

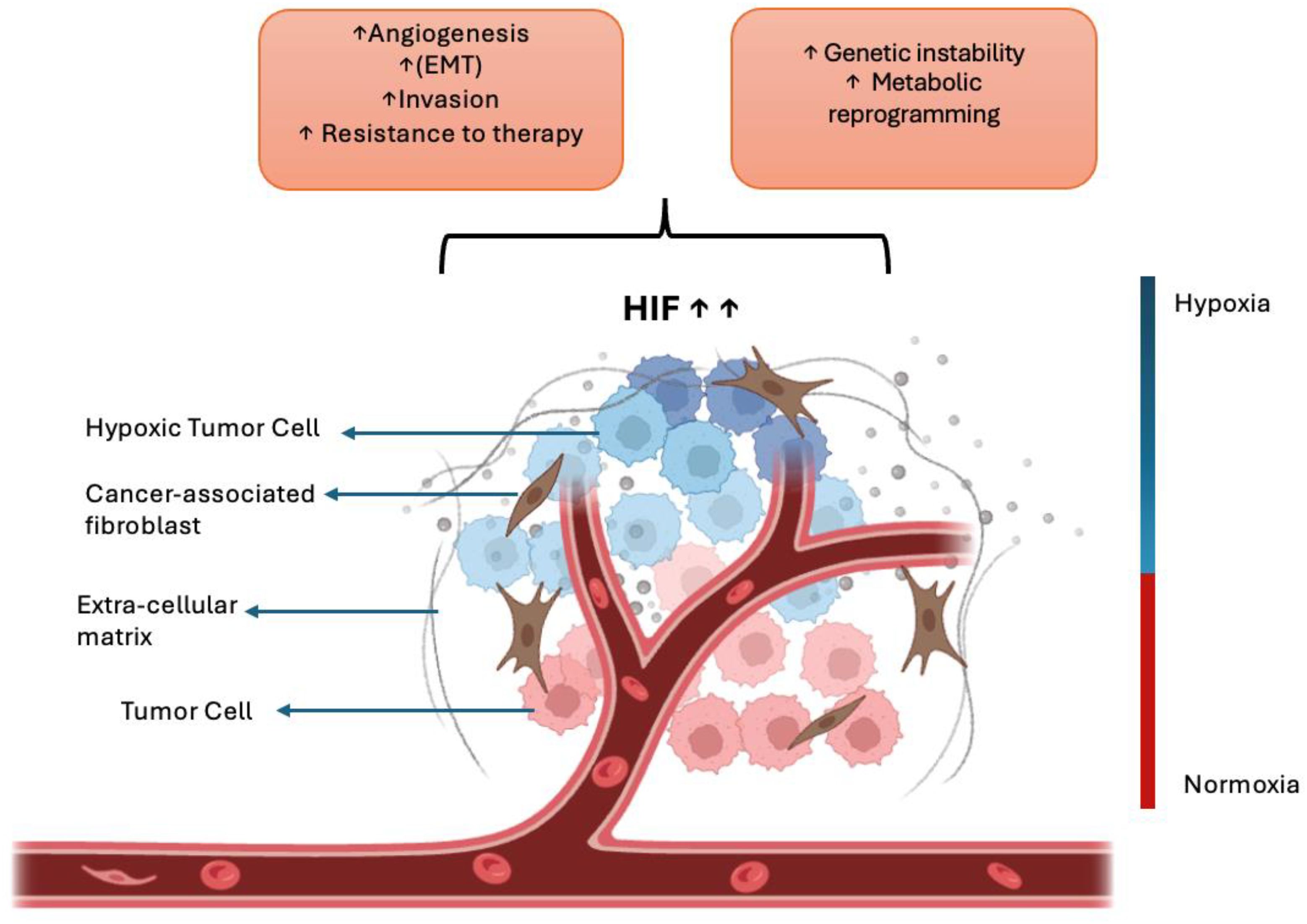

Hypoxia (low oxygen) in the TME strongly drives metastasis. Under hypoxic stress, cancer cells stabilize HIF-1α and HIF-2α, which activate genes promoting angiogenesis, EMT, invasion, and therapy resistance (70, 71). These adaptations increase cell motility and survival, enabling tumor cells to escape the primary site and colonize distant organs. Hypoxia also impairs DNA repair and causes genomic instability, and it reprograms cellular metabolism to support an invasive phenotype (72). Clinically, tumors with high hypoxia or HIF levels exhibit more metastases and poorer patient outcomes (72). One key consequence of hypoxia is the induction of angiogenesis (Figure 4)—new blood vessels that supply the tumor with oxygen and nutrients and provide routes for dissemination (73). Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis are fundamental processes enabling tumor growth and spread. Angiogenesis—the sprouting of new blood vessels from existing vasculature—is driven by growth factors such as VEGF (and FGF) (73). It provides tumors with nutrients and oxygen and creates conduits for tumor cells to enter the bloodstream. Importantly, higher intratumoral microvessel density (a measure of angiogenesis) strongly correlates with increased metastatic potential and worse prognosis (73).

Figure 4. Hypoxia-driven mechanisms in cancer metastasis. Under low-oxygen conditions, cancer cells stabilize hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1α and HIF-2α), which activate downstream signaling pathways that promote angiogenesis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, and therapeutic resistance. These molecular adaptations enable cancer cells to escape from the primary tumor and metastasize to distant organs. Created with BioRender.com.

Lymphangiogenesis—the formation of new lymphatic vessels—is similarly induced by factors like VEGF-C and VEGF-D (73), which facilitate tumor cell entry into lymphatic capillaries and spread to regional lymph nodes. Both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis thus serve as prognostic indicators and therapeutic targets: blocking VEGF/VEGFR or related signaling can limit metastatic dissemination. Figure 5 illustrates tumor-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis under these conditions.

Figure 5. Tumor-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in metastatic progression. Tumor-secreted growth factors (VEGF, FGF, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D) stimulate the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and lymphatic vessels (lymphangiogenesis), providing routes for cancer cell dissemination to distant organs and regional lymph nodes, respectively. Increased vascular density correlates with enhanced metastatic potential and poor prognosis. Created with BioRender.com.

2.5 Tumor cell migration mechanisms

Tumor cell migration is a highly adaptable process involving several distinct mechanisms that enable cancer cells to invade the surrounding tissues and metastasize. These mechanisms include individual migration, such as mesenchymal and amoeboid movement, and collective migration, where groups of cells move together while maintaining cell–cell junctions (74). Mesenchymal migration is characterized by an elongated cell morphology, strong adhesion to the ECM via integrins, and proteolytic degradation of ECM components, often facilitated by MMPs (74, 75). In contrast, amoeboid migration involves rounded, highly deformable cells that can squeeze through ECM gaps with minimal proteolysis, relying more on cytoskeletal contractility and less on adhesion (74). Collective migration allows clusters or sheets of tumor cells to invade while preserving intercellular connections, providing resistance to environmental stress (75). The plasticity of tumor cells enables them to switch between these migration modes in response to microenvironmental cues, such as ECM stiffness or therapeutic interventions, which complicates efforts to target metastasis (74, 75). At the molecular level, migration is driven by actin polymerization, formation of membrane protrusions (lamellipodia and filopodia), and dynamic regulation of adhesion complexes, all tightly coordinated by signaling pathways and mechanical forces (76).

Given the reciprocal interplay between migrating tumor cells and host immunity, understanding the dualistic role of the immune system in constraining or promoting metastasis is essential.

2.6 Tumor–immune system interactions

Tumor–immune system interactions represent a complex and dynamic relationship that critically influences cancer progression and metastasis. Rather than passively escaping immunosurveillance, metastatic cancer cells actively hijack and reprogram the immune system to facilitate progression through a metastatic cascade (60). This bidirectional relationship evolves throughout tumor development, with immune cells initially demonstrating anti-tumor effects during the early invasion stages, before transitioning into tumor-promoting phenotypes as the disease advances (77). Tumors employ multiple immune evasion mechanisms, including restricting antigen recognition, creating immunosuppressive microenvironments, and exploiting immune checkpoints (78). Particularly important is how cancer cells undergoing EMT contribute to immune suppression, allowing them to escape from cytotoxic T cells and NK cells (60). Immune cells, particularly those of the myeloid lineage, reciprocally support metastasis by secreting inflammatory factors that promote invasion, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling (79). These interactions extend beyond the primary tumor, as tumor–immune crosstalk generates premetastatic niches in distant organs, facilitating colonization and determining organ-specific metastatic patterns, or “organotropism” (60, 80).

Understanding these complex interactions provides critical insights for developing immunotherapeutic strategies that disrupt tumor–immune collaboration and enhance anti-tumor immunity.

3 Advances in therapeutic targeting of metastasis

3.1 Targeting EMT pathways

One therapeutic approach involves inhibiting EMT-activating transcription factors (EMT-TFs) such as Snail, Twist, and ZEB1/2 through RNA interference (RNAi)-based approaches, antisense oligonucleotides, or vaccine-based modalities (81).

A complementary therapeutic strategy involves inhibiting the upstream signaling pathways that sustain EMT, particularly TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, Notch, RAS, and PI3K/Akt. Several pharmacological and repurposed agents have shown potential to disrupt these networks. For example, the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor rolipram and the statin simvastatin attenuate TGF-β-induced EMT, while suramin (a heparanase inhibitor) and olaparib (a PARP inhibitor) suppress EMT in TGF-β-driven models (82–84). Collectively, these findings underscore that targeting EMT-related signaling, even with drugs of established safety profiles, can modulate metastatic behavior and may facilitate rapid clinical translation.

Increasing attention has been directed toward non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) (85). These molecules serve as critical regulators of EMT and contribute to both intrinsic and acquired resistance to cancer therapies (86). Tumor-suppressive miRNAs, such as the miR-200 family and miR-34, have been shown to directly suppress EMT-TFs, whereas oncogenic lncRNAs and circRNAs often promote EMT by modulating chromatin structure or acting as miRNA sponges (24, 87, 88). Therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring tumor-suppressive ncRNAs or inhibiting oncogenic ncRNAs are being actively investigated using tools such as antagomirs, antisense oligonucleotides, miRNA mimics, and CRISPR-Cas9-based approaches. However, safe and efficient delivery remains a major challenge, and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and ligand-targeted carriers are being researched and developed to address this limitation (85).

Another promising avenue lies in targeting post-translational regulators of EMT. Enzymes such as Hakin-1, FBXW7, and USP27X influence the stability and activity of EMT TFs through protein degradation pathways, offering additional points for therapeutic intervention. Moreover, modulating the TME represents another approach to limiting EMT activation, with strategies targeting fibroblast-derived signals and immune-cell-mediated cytokine loops (89–91). Because EMT can influence tumor–immune interactions, combining EMT-targeted strategies with immunotherapy may enhance treatment responsiveness (92).

Recent studies have underscored the role of metabolic reprogramming in the EMT. Cancer cells undergoing EMT exhibit altered glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolisms, supporting their survival and migration in hostile microenvironments (93). Metabolic inhibitors, including 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), L-tetrahydro-2-furoic acid (L-THFA), and 4-methylumbelliferone, have demonstrated the potential to block EMT-associated metabolic shifts (94, 95). Repurposing such agents, many of which have been evaluated in other clinical contexts, could provide a feasible route for targeting the EMT with reduced toxicity. Epalrestat, which is currently undergoing Phase II trials for triple-negative breast cancer, exemplifies this strategy (96). These metabolic inhibitors are also being investigated as adjuncts to standard chemotherapy or immunotherapy to overcome the resistance associated with EMT.

EMT exists along a phenotypic continuum, and emerging evidence indicates that intermediate or hybrid EMT states, characterized by the co-expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers, possess heightened metastatic and adaptive potential. Consequently, indiscriminate inhibition of EMT may inadvertently promote MET, enabling disseminated cells to reacquire epithelial traits conducive to secondary tumor formation (41).

EMT is closely associated with cancer stem cell (CSC) traits. EMT can endow cells with stem-like properties, including self-renewal and resistance to apoptosis, which contribute to tumor initiation, relapse, and poor clinical outcomes (97). Thus, targeting EMT may reduce the stemness of residual tumor cells and limit recurrence. Several clinical studies have begun to explore EMT-modulating therapies, including the TGF-β receptor I inhibitor, galunisertib, which has undergone early phase trials in combination with chemotherapeutics (98). Although the data remain preliminary, these efforts represent the initial steps in translating EMT research into clinical practice.

In addition to therapeutic interventions, targeting the EMT has been proposed as a chemopreventive strategy for high-risk individuals, particularly when the EMT contributes to early tumorigenic processes. However, caution must be exercised in this regard. The lack of robust clinical biomarkers for detecting and monitoring EMT progression, particularly in partial EMT states, limits translational success (93). Future research should focus on integrating liquid biopsy tools and single-cell technologies to monitor EMT dynamics in real time. CTCs, exosomal RNA, and spatial transcriptomics may help stratify patients and guide EMT-targeted therapies with greater precision. As our understanding of EMT biology continues to evolve, personalized multipronged approaches will be essential for overcoming the complexity of EMT-driven cancer progression and metastasis.

3.2 ECM inhibitors and anti-MMP therapies

Given its central role in tumor invasion and metastatic progression, the ECM has emerged as a therapeutic target. Among the enzymes that modulate ECM remodeling, MMPs, a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases frequently overexpressed in tumors, are of particular interest (99, 100). Among the MMP family, isoforms such as MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-13 are particularly associated with invasion, angiogenesis, and metastatic niche formation, making them key candidates for selective therapeutic targeting (101).

Despite the well-established role of MMPs in cancer metastasis, therapeutic efforts to target them have faced significant challenges. Early generation broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors, such as batimastat and marimastat, were evaluated in clinical trials but were ultimately discontinued owing to limited efficacy and unacceptable musculoskeletal toxicity (102). These failures were not solely due to toxicity but also reflected an incomplete understanding of MMP biology at the time. While certain MMPs promote tumor invasion and angiogenesis, others maintain essential physiological functions in wound healing, immune modulation, and vascular homeostasis. Broad-spectrum inhibition disrupted this balance, leading to off-target effects and a narrow therapeutic window. Moreover, most clinical trials administered MMP inhibitors in late-stage cancers, where tumors were already well-established and vascularized (98). However, current evidence suggests that MMPs exert their most critical functions during the early phases of tumor progression, including local invasion and stromal remodeling. This treatment stage mismatch likely contributed to the lack of therapeutic benefit observed in advanced disease settings. Additionally, the absence of predictive biomarkers and insufficient stratification of patients whose tumors were truly MMP-driven may have further obscured potential responses (103). These drawbacks are largely attributed to the lack of specificity for individual MMP isoforms and the essential physiological roles played by MMPs in normal tissue remodeling and wound healing. Consequently, more recent strategies have focused on improving selectivity and minimizing systemic side effects. For instance, targeting specific MMPs associated with distinct stages of metastasis, such as MMP-2 in tumor invasion or MMP-9 in angiogenesis, offers a more refined approach. In a preclinical model, combining hemoglobin-loaded liposomes with chemotherapeutic agents effectively reduced MMP-2 expression and attenuated tumor invasiveness, suggesting that the indirect modulation of MMP activity through combination strategies may have therapeutic potential (104).

Beyond MMPs, LOX family enzymes have emerged as additional therapeutic targets due to their role in ECM stiffening and metastatic dissemination previously described in this review. Inhibitors of LOX are currently under investigation for their ability to prevent PMN formation and reduce metastatic burden (105).

Given the diverse and context-dependent functions of ECM remodeling in metastasis, therapeutic inhibition must be carefully optimized to balance efficacy with systemic safety. Because ECM remodeling occurs early and continuously during tumor progression, the timing of intervention is likely critical for clinical success. Emerging technologies such as ECM-targeted imaging and proteomic profiling may improve patient stratification and accelerate the translation of ECM-modulating therapies (106).

Ultimately, although direct inhibition of the ECM remains a challenging therapeutic frontier, it offers considerable promise when integrated into comprehensive anti-metastatic strategies. Selective targeting of matrix-degrading enzymes in combination with systemic treatments or nanotechnology-based delivery systems represents a next-generation approach to disrupting the physical and biochemical mechanisms that facilitate tumor dissemination and colonization.

3.3 Targeting hypoxia pathways

Hypoxia within the TME is a hallmark of solid malignancies and is closely linked to metastatic progression and resistance to conventional therapies. This adaptive response is largely mediated by HIF-1α and HIF-2α, which regulate transcriptional programs that promote survival, invasion, angiogenesis, and immune evasion (107, 108).

Considering its profound impact on tumor biology and clinical outcomes, hypoxia has emerged as a rational and validated target for therapeutic intervention (109). One widely explored approach involves inhibition of HIF signaling. Pharmacological strategies for blocking HIF function target various steps, such as protein stability, dimerization, transcriptional activity, and downstream gene expression (110). Agents including PX-478, digoxin, acriflavine, echinomycin, and bortezomib have shown preclinical activity in suppressing HIF-1α signaling, with some advancing to early-phase clinical trials (111–113). Specific inhibitors of HIF-2α, such as PT2385 and PT2977, have also demonstrated efficacy in hypoxia-driven tumors like renal cell carcinoma (114). Moreover, repurposed compounds, such as high-dose vitamin C and quercetin, interfere with HIF-mediated transcription, offering alternative strategies for modulating hypoxic responses (115, 116).

In addition to directly targeting HIFs, the development of hypoxia-activated prodrugs (HAPs) has provided a selective means of eradicating hypoxic tumor cells. These bioreductive agents remain inactive under normoxic conditions but are metabolically activated in hypoxic regions, enabling preferential toxicity to oxygen-deprived cancer cells (116). Examples include tirapazamine, PR-104, AQ4N, TH-302 (evofosfamide), and SN30000. Despite encouraging results in early phase trials, some HAPs have failed in phase III studies, partly owing to challenges in identifying suitable patient populations and achieving sufficient drug penetration in deeply hypoxic tumor zones. Nevertheless, HAPs continue to hold promise, particularly in targeting micrometastases and dormant cancer cells located in severely hypoxic niches (117).

Another avenue involves increasing oxygen availability in tumors through systemic reoxygenation strategies or localized oxygen delivery systems (116, 117). For instance, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been shown to transiently improve tumor oxygenation and enhance the efficacy of radiation and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (118). More advanced approaches include the use of oxygen-generating nanoparticles and bioengineered carriers such as catalase-loaded vesicles, which release oxygen directly into the hypoxic microenvironment (116). These strategies alleviate hypoxia and modulate the tumor vasculature and immune landscape, increasing the infiltration of cytotoxic T cells and reducing regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (119).

In addition to HIF signaling and oxygen delivery, hypoxia drives tumor progression through metabolic reprogramming, ECM remodeling, and immune modulation. Hypoxia-induced metabolic shifts, such as increased glycolysis, glutamine metabolism, and lipid biosynthesis, support cancer cell survival in hostile environments and facilitate distant organ colonization (120, 121). Targeting these pathways, for instance, by inhibiting PDK1 or creatine kinase activity, may limit the metastatic capacity of hypoxia-adapted cells (120). Hypoxia also promotes ECM degradation and alignment through the upregulation of MMPs and LOX family enzymes (e.g., LOX and LOXL2), which facilitate cancer cell invasion and the establishment of premetastatic niches. In this context, digoxin- and LOX-directed antibodies have shown potential in preclinical models by limiting metastatic spread (122).

Crucially, hypoxia contributes to immune evasion by upregulating immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 via HIF-1α and fostering an immunosuppressive TME. Targeting these effects through combined oxygenation, HIF inhibition, and the blockade of downstream pathways, such as the adenosine A2A receptor axis, has been proposed to improve immunotherapy outcomes (123). Engineering immune cells, such as NK cells, to better withstand hypoxic stress is also under investigation as a means of overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance (124, 125).

Nanotechnology has further enhanced the ability to precisely target hypoxia. Nanoparticles can be engineered to deliver antihypoxic agents, siRNAs, or HAPs specifically to oxygen-deficient tumor regions, thereby improving the therapeutic index while minimizing off-target toxicity (116, 126). Red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles have been used to co-deliver chemotherapy and oxygen, while manganese dioxide nanoparticles have demonstrated dual action by alleviating hypoxia and suppressing HIF-1α expression (126, 127).

Despite these promising strategies, several major challenges remain. One key limitation of clinical translation is the heterogeneity of hypoxia across tumors and patients. Standardized, noninvasive methods to measure and stratify tumor hypoxia are lacking, rendering patient selection difficult in clinical trials. Advanced imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET) with hypoxia-sensitive tracers, are under development and may improve patient stratification (128). Additionally, the complexity of the hypoxia-driven transcriptional landscape, redundancy in survival pathways, and potential toxicity to normal tissues under physiological hypoxia must be addressed through refined therapeutic designs and combination regimens (116).

3.4 Inhibiting angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the generation of new vasculature from pre-existing vessels, is a critical driver of tumor growth and metastatic dissemination. Tumors exploit angiogenic signaling to secure oxygen and nutrient supply, eliminate metabolic waste, and establish routes for invasion (129–131). Among the mediators of tumor angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and its receptor VEGFR-2 constitute the principal signaling axis that regulates endothelial proliferation, migration, and survival. Elevated VEGF activity correlates with increased vascular density, aggressive tumor behavior, and poor prognosis, establishing the VEGF/VEGFR pathway as a central target for anti-angiogenic cancer therapy (131, 132).

3.4.1 Anti-VEGF therapies

Therapeutic strategies targeting angiogenesis fall into three principal categories: ligand-neutralizing agents, VEGF receptor-directed agents, and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (131). Ligand-neutralizing antibodies such as bevacizumab, the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-angiogenic drug, bind VEGF-A and prevent its interaction with VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, thereby suppressing neovascularization and reducing vascular permeability, two key drivers of metastatic spread. Bevacizumab has demonstrated clinical benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, and other malignancies (133).

VEGF receptor-targeting agents, including the fusion protein aflibercept (VEGF-trap), act as decoy receptors that sequester VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and placental growth factor (PlGF), producing broader blockade of pro-angiogenic signaling (134). In contrast, TKIs such as sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib inhibit the intracellular kinase activity of VEGFRs and related angiogenic receptors, thereby curtailing endothelial proliferation and metastatic vascular support (129–132, 135).

Short-term anti-VEGF therapy can transiently normalize aberrant tumor vasculature, reducing leakiness, improving perfusion, and enhancing drug and oxygen delivery. This “vascular normalization” window enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy, but is transient and dose-dependent, requiring precise scheduling to exploit optimally (136).

Nonetheless, durable clinical responses remain limited by adaptive resistance mechanisms, including compensatory up-regulation of alternative angiogenic pathways and recruitment of pro-angiogenic myeloid cells. These limitations underscore the rationale for integrating VEGF-targeted agents with cytotoxic, immunomodulatory, or other anti-metastatic therapies to achieve sustained therapeutic benefit.

3.4.2 Limitations and resistance mechanisms of anti-VEGF

Despite the initial clinical benefit, anti-VEGF therapies frequently encounter intrinsic or acquired resistance, leading to transient responses and poor long-term survival (137, 138). Resistance arises through several mechanisms. Tumors circumvent VEGF blockade by activating parallel pro-angiogenic signaling networks involving PDGF, bFGF, Ang-1/2, PlGF, and VEGF-D, the latter stimulating VEGFR-3-mediated lymphangiogenesis even under VEGF-A inhibition (134, 137, 139, 140). In addition, tumors can adopt alternative vascularization strategies such as vessel co-option, vasculogenic mimicry, and intussusceptive angiogenesis, all of which sustain perfusion independent of classical VEGF signaling (134, 138, 141–143).

Anti-angiogenic therapy also remodels the TME, often aggravating hypoxia and stabilizing HIF-1α, which, in turn, re-induces angiogenic and pro-survival genes. Hypoxia recruits immunosuppressive myeloid and regulatory cells (MDSCs, TAMs, and Tregs) and drives desmoplastic ECM deposition that limits drug penetration, collectively reinforcing therapeutic resistance (144, 145). Additional contributors include endothelial heterogeneity, MDR protein overexpression, lysosomal degradation of TKIs, and angiogenic gene polymorphisms affecting drug response (131, 136, 145).

The clinical utility of VEGF blockade is further constrained by toxicity, as VEGF is integral to normal vascular maintenance. Adverse events such as hypertension, proteinuria, hemorrhage, and impaired wound healing frequently necessitate dose reduction or discontinuation, narrowing the therapeutic window (146, 147). Moreover, rebound hypoxia following vessel regression can paradoxically promote EMT and metastatic dissemination, illustrating the dualistic nature of angiogenesis suppression (146).

To address these limitations, combination regimens are increasingly employed. Integrating VEGF inhibitors with chemotherapy enhances drug delivery and cytotoxicity, while combinations with immune checkpoint blockade reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor milieu and convert “cold” tumors to “hot” ones more amenable to immunotherapy (144, 148–150). Dual angiogenic blockade (e.g., VEGF plus Ang-2 or PDGFR inhibition) and rational scheduling to exploit transient vascular normalization further improve outcomes (151–154). Collectively, these advances underscore that durable benefit requires targeting angiogenesis within multimodal frameworks guided by predictive biomarkers and precision-medicine principles.

3.5 Immunotherapies for metastatic cancer

Immunotherapy has revolutionized metastatic cancer treatment by enabling the body’s immune system to detect and destroy tumor cells. Unlike conventional therapies that directly target tumor proliferation or vascularization, immunotherapy modulates the immune response to achieve durable control or eradication of malignancies. Among the most significant advances are ICIs and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, both of which have demonstrated promise for the treatment of advanced cancers, although each faces distinct challenges in the metastatic setting.

3.5.1 Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoints function as vital mechanisms that maintain self-tolerance while controlling the intensity of physiological immune reactions. However, tumor cells often utilize these pathways, particularly the CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 axes, to escape immune surveillance. ICIs function by disrupting these inhibitory signals, removing T-cell activation restrictions, and restoring antitumor immunity (155, 156).

The first checkpoint inhibitor to receive FDA approval was ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody that demonstrated survival benefits in metastatic melanoma. CTLA-4, expressed on Tregs and activated T cells, impairs immune priming by inhibiting the co-stimulatory signaling between CD28 and its ligands (CD80/CD86) in antigen-presenting cells. Ipilimumab counteracts immunosuppression by enhancing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity (157).

Subsequent therapeutic developments focused on the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor expressed on activated T cells, whereas PD-L1 is overexpressed in tumors and stromal cells. These interactions suppress T-cell proliferation, cytokine production, and survival. PD-1 inhibitors such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, and PD-L1 inhibitors including atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab, have been approved for a broad spectrum of solid tumors, including metastatic melanoma, NSCLC, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and urothelial carcinoma (158–160).

Nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy demonstrated superior results to monotherapy in metastatic melanoma patients through improved survival rates and sustained treatment outcomes (161, 162). Pembrolizumab, alone or in combination with chemotherapy, is the first-line treatment option for metastatic NSCLC. ICIs have also shown benefits in colorectal cancers with high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), which are characterized by high tumor mutational burden and neoantigen load, factors that enhance immunogenicity (162).

Despite their potential for transformation, ICIs are not universally effective. A substantial proportion of patients exhibit primary resistance, and many experience relapse. Resistance mechanisms include low tumor immunogenicity; absence or exclusion of T cells from the TME; and compensatory immunosuppressive mechanisms involving MDSCs, Tregs, or alternative checkpoint pathways. Moreover, immune-related adverse events (irAEs), ranging from dermatitis and colitis to endocrinopathies and pneumonitis, can necessitate treatment discontinuation and immunosuppressive interventions (158, 163).

3.5.2 CAR-T cell therapies and their challenges in metastasis

The development of CAR T-cell therapy has led to significant progress in immuno-oncology, particularly in the treatment of hematological conditions. This approach involves the ex vivo genetic modification of autologous T cells to express CARs that target specific tumor-associated antigens. Upon reinfusion, the engineered cells recognize and destroy malignant cells in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent manner. The application of CD19-targeted CAR-T cells has proven highly successful in treating B-cell malignancies, achieving complete remission in many patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (164).

However, translating the success of CAR-T therapy to solid tumors, especially in metastatic settings, has proven more difficult. As previously discussed, the immunosuppressive and structurally complex TME remains a major obstacle to effective CAR-T therapy. Factors such as cytokine-mediated suppression, cellular inhibitors, and hypoxia collectively impair T-cell activation, infiltration, and persistence within solid tumors. Additionally, the abnormal vasculature and dense ECM of solid tumors limit the effective trafficking, infiltration, and survival of CAR-T cells at tumor sites (165).

Antigen heterogeneity and immune escape are also obstacles. Unlike hematologic cancers, in which a uniform and lineage-restricted antigen such as CD19 can be targeted, solid tumors often exhibit variable and heterogeneous antigen expression. This variability can result in antigen-loss variants or selection of resistant tumor clones, leading to treatment failure. Furthermore, many tumor-associated antigens are expressed at low levels in normal tissues, increasing the risk of on-target off-tumor toxicity, a potentially life-threatening complication (166).

Therefore, various methods have been developed to overcome these limitations. Strategies include engineering CAR-T cells with dual or tandem CARs to target multiple antigens, using armored CAR-T cells that secrete immune-stimulating cytokines, and combining CAR-T therapy with ICIs or antiangiogenic agents to improve T-cell infiltration and function. Locoregional delivery approaches such as intratumoral or intra-arterial injections have also been explored to enhance tumor-specific accumulation and reduce systemic toxicity (165). Additionally, novel delivery platforms, such as biomaterial scaffolds and CAR-macrophage (CAR-M) therapies, are under investigation for their ability to improve tumor penetration and modulate the suppressive TME (167).

Despite these advancements, CAR T-cell therapy for metastatic solid tumors remains in its early clinical stages. The need for improved antigen specificity, enhanced cell persistence, and resistance to immunosuppression continues to drive innovation in CAR engineering, delivery strategies, and combination regimens. As our understanding of tumor–immune system interactions deepens, the integration of CAR-T cell therapy into metastatic cancer treatment models holds considerable promise, particularly when combined with other immunomodulatory and cytotoxic modalities (168).

3.6 Recent advancements in drug delivery systems

Effective management of metastatic disease requires drug delivery systems that directly target the biological and physical pathways enabling invasion and colonization. Conventional formulations often fail because metastatic niches are protected by desmoplastic extracellular matrices, aberrant and poorly perfused vasculature, and immunosuppressive microenvironments that restrict penetration and foster cellular dormancy (169–171). Additional challenges arise from organ-specific barriers such as the blood–brain barrier, from physical forces including elevated interstitial pressure and solid stress that impair convective transport, and from pharmacokinetic limitations such as rapid clearance and multidrug resistance. As detailed in earlier sections, features such as ECM remodeling, vascular disorganization, and immune suppression actively contribute to metastatic progression rather than serving as passive barriers; therefore, delivery platforms must be designed to counteract these mechanisms.

Recent nanotechnology-based systems integrate molecular and physical design principles to overcome these constraints. Immune-modulating nanoparticles reprogram suppressive immune and stromal cells within the metastatic niche; ECM-degrading or shape-adaptive carriers penetrate dense stroma; and stimuli-responsive formulations release drugs in response to pH, enzymatic activity, or hypoxia—conditions characteristic of invasive lesions (172, 173). Ligand conjugation and biomimetic surface coatings improve organ-specific targeting, prolong systemic circulation, and enhance therapeutic retention. Collectively, these advances couple drug-delivery engineering with the molecular hallmarks of metastasis, providing a framework for selective and sustained eradication of DTCs.

3.6.1 Precision medicine approaches, including nanotechnology, lipid carriers, and targeted delivery systems

The most clinically validated nanocarriers include lipid-based systems such as liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs). Liposomes consist of phospholipid bilayers surrounding an aqueous core and can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs (174). Modifications such as PEGylation improve the circulation half-life by evading opsonization and phagocytosis, while ligand conjugation ensures active targeting (173). The success of liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil®), the first FDA-approved nanodrug, underscores the translational potential of this platform. In addition, LNPs have become prominent vehicles for nucleic acid delivery, particularly mRNA delivery, offering applications in both cancer therapeutics and immunization strategies. These carriers demonstrate high transfection efficiency, endosomal escape, and safety profiles, making them ideal for delivering gene regulatory sequences to metastatic cells (175).

Targeted drug delivery is the cornerstone of nanoparticle drug delivery system (NDDS) functionality and is achieved through both passive and active mechanisms. Passive targeting uses the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, a phenomenon characterized by leaky tumor vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage, permitting the preferential accumulation of nanoparticles at tumor sites. Active targeting involves the surface functionalization of nanoparticles with ligands such as antibodies, peptides, aptamers, or vitamins that bind selectively to receptors overexpressed on tumor cells, thereby enhancing cellular uptake and retention. Such precision is vital in the metastatic context, where DTCs often reside in complex or inaccessible places, such as the brain, bone marrow, or lymphatic system. Active targeting facilitates greater intracellular uptake and enhances therapeutic efficacy by maintaining localized drug concentrations, thereby reducing the need for high systemic doses that contribute to toxicity (176–178).

Another approach for achieving precise drug delivery is the development of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers. These advanced systems are designed to release therapeutic payloads in response to specific endogenous stimuli, such as acidic pH, high levels of glutathione, tumor-associated enzymes, or exogenous triggers including temperature, magnetic fields, ultrasound, or light. This responsiveness enables spatiotemporal control of drug release, providing on-demand activation at the tumor site while minimizing off-target effects. Such systems are particularly valuable for treating metastases located in organs with sensitive microenvironments, such as the brain or lungs (179). By enhancing penetration, selective accumulation, and controlled release within metastatic niches, these precision delivery systems directly address the microenvironmental barriers that sustain invasion, dormancy, and colonization.

3.6.2 Specific examples such as SNA and amphiphile-based systems

Spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) represent a next-generation class of nanotherapeutics constructed by densely arranging DNA, RNA, or miRNA strands around a nanoparticle core, such as gold, polymers, or liposomes. This three-dimensional architecture enhances cellular uptake and nuclease resistance. Their structural design facilitates the efficient delivery of gene regulatory agents (e.g., siRNA or miRNA) to silence oncogene expression, with advanced formulations demonstrating high-density duplex loading and improved endosomal escape for sustained knockdown effects (180).

In addition to gene silencing, SNAs exhibit a strong immunotherapeutic potential. Immunostimulatory SNAs functionalized with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, such as CpG oligonucleotides, activate dendritic cells and induce robust T cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Hybridized SNAs that co-deliver tumor antigens and immune adjuvants have shown enhanced T-cell activation and tumor regression in preclinical models. Liposomal SNAs, which are constructed by combining amphiphilic liposomal cores with surface-bound nucleic acids, exemplify the convergence of gene modulation and immune activation strategies. These systems have demonstrated the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, making them promising candidates for targeting brain metastases. Early-phase clinical studies have confirmed their safety, and ongoing efforts employing artificial intelligence and high-throughput screening aim to further refine their therapeutic efficacy through optimized structure–function relationships (180, 181).

Polymeric micelles and amphiphile-based nanocarriers have also gained attention in metastatic cancer therapy. These structures are formed by the self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers, creating core–shell architectures capable of encapsulating hydrophobic drugs. Their small size enhances tumor penetration and lymphatic transport. A well-known example is Genexol-PM®, a paclitaxel-loaded polymeric micelle formulation that has been approved for clinical use in several countries, including South Korea and parts of Asia, although it has not yet received FDA approval in the United States (182). Further refinement has led to the development of peptide amphiphile micelles (PAMs), which incorporate targeting ligands or cell-penetrating peptides into the micellar structure to achieve receptor-specific delivery and enhance cellular uptake (183). Collectively, these nucleic acid and amphiphile-based nanocarriers address key challenges in metastatic cancer by enabling gene regulation, immune activation, and efficient drug transport across physiological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier, thereby improving therapeutic access to disseminated and treatment-resistant tumor cells.

3.6.3 Clinical translation and ongoing challenges

The integration of nanotechnology with precision medicine is transforming metastatic cancer treatment by enabling targeted and personalized drug delivery. Clinical examples include PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin with trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (184). Bone-targeting alendronate nanoparticles (185) and brain-targeting intranasal nanocarriers (186) are under active preclinical and translational investigation. These strategies demonstrate the adaptability of nanoscale delivery systems to overcome site-specific challenges in metastatic treatments. By addressing the biological and physiological barriers that characterize metastatic niches, such as vascular heterogeneity, immune suppression, and organ specific permeability, these targeted systems exemplify how precision nanomedicine can directly influence invasion, colonization, and treatment resistance.

Despite promising outcomes, translational challenges remain significant. Drawbacks such as inconsistent nanoparticle accumulation, variable drug ratios, scale-up difficulties, and unintended deposition in non-target organs, such as the liver and spleen, continue to impede widespread clinical application. Addressing these challenges requires refined nanoparticle design, improved manufacturing protocols, and more precise patient stratification (187).

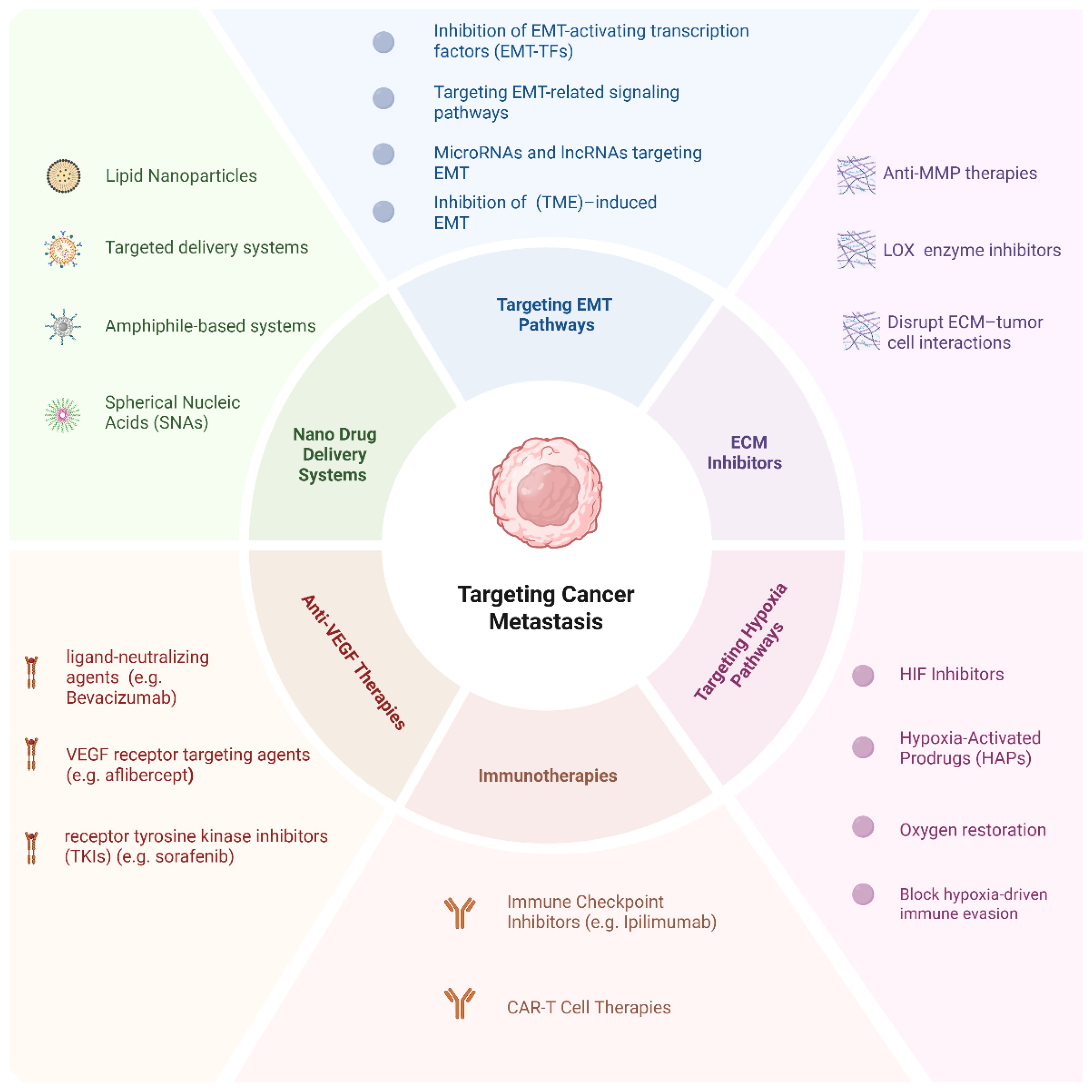

Recent innovations, including SNAs, peptide-functionalized amphiphilic systems, and stimuli-responsive carriers, demonstrate the evolving sophistication of nanomedicines. These platforms enhance drug solubility, stability, and release kinetics, while minimizing systemic toxicity. With interdisciplinary research bridging the fields of materials science, oncology, and bioengineering, the development of intelligent patient-specific nanomedicines is reshaping metastatic cancer therapy. With continued advancements, these next-generation systems hold great promise for delivering safer, more effective, and highly individualized treatments. Figure 6 provides a comprehensive overview of the key interventions discussed in this section.

Figure 6. Targeting cancer metastasis: a comprehensive overview of therapeutic strategies. This diagram illustrates the six principal therapeutic categories aimed at combating cancer metastasis.

4 Emerging technologies and innovations

4.1 Multi-omics approaches

EMT transition, cell adhesion, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis are among the various multistep processes involved in cancer cell invasion and metastasis (169). Tumor heterogeneity, which encompasses genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic elements that drive cancer progression, complicates the identification and prevention of recurrence (188). Although conventional single-omics approaches are valuable, they provide limited perspectives and are inadequate for capturing the complexity of cancer (189, 190). This limitation is particularly critical in metastasis, where coordinated alterations across genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic networks drive invasion, immune evasion, and colonization.

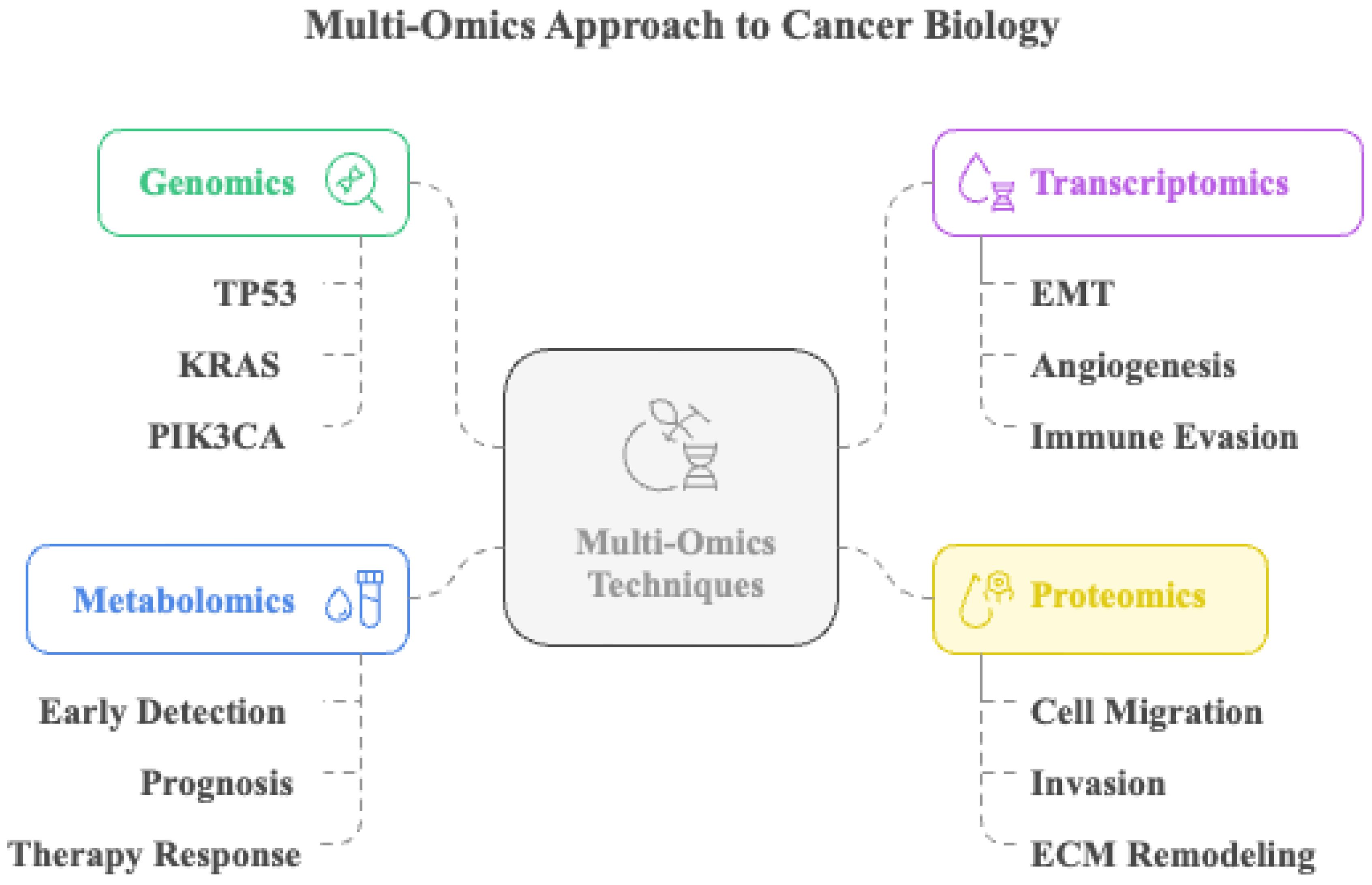

These limitations highlight the need for more thorough methods to provide better knowledge of cancer biology (190). By capturing the complex interactions between molecular processes, multi-omics techniques, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, offer a more thorough understanding of cancer biology (190).

Through this systems-level integration, researchers can trace how molecular heterogeneity translates into metastatic phenotypes and treatment resistance. Integrating multi-omics data offers the potential to identify unique biomarkers for early detection, prognosis, and therapeutic responses. Additionally, multi-omics facilitates the identification of new therapeutic targets and strategies to combat cancer invasion and metastasis (191, 192). Nonetheless, the analysis of multi-omics data to identify trends and links between several data types depends on advanced computational techniques and machine learning algorithms, which provide insights into the fundamental causes of cancer progression (188, 193).

Additionally, proteomic profiling highlights active signaling pathways and post-translational modifications related to cell migration, invasion, and ECM remodeling, further enhancing our understanding of these processes (194).

Integrative multi-omics platforms have improved our knowledge of metastatic processes and offered new targets for pathway-specific therapies (195). Genomic sequencing has revealed mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors such as TP53, KRAS, and PIK3CA, which are associated with metastatic potential in many malignancies (196). With the growing importance of lncRNAs and microRNAs, transcriptomic studies have shown that they alter the expression of genes that control the EMT, angiogenesis, and immune evasion (197). Beyond enriching our mechanistic understanding, multi-omics approaches are now demonstrating direct clinical utility in monitoring metastatic evolution, detecting minimal residual disease (MRD), and guiding personalized therapeutic strategies. For instance, longitudinal tumor-informed ctDNA profiling coupled with genomic and transcriptomic modeling, as shown in the TRACERx lung cancer program, enables real-time tracking of subclonal expansion and metastatic seeding, identifying relapse months before radiological detection (198, 199). Likewise, plasma-only multi-omics MRD assays that integrate somatic variants with epigenomic (methylation) signatures have increased sensitivity for detecting micrometastasis and residual disease in early-stage breast and colorectal cancer, supporting risk-adapted adjuvant therapy and intensified surveillance (200, 201). In terms of patient stratification, proteogenomic analyses (e.g., CPTAC) have revealed pathway activation states and phospho-signaling dependencies not predictable from genomics alone, informing therapeutic prioritization and resistance mechanisms (202, 203). Complementing this, the WINTHER clinical trial demonstrated that incorporating transcriptomic profiling alongside tumor genomics increased the proportion of patients matched to targeted therapy and improved clinical benefit, underscoring the translational relevance of integrative multi-omics in precision oncology decision-making (204). Emerging single-cell and spatial multi-omics further allow resolution of rare disseminated clones and metastatic niche interactions, holding promise for earlier intervention and rational combination treatment design (205). The multi-omics techniques are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Multi-omics approach to cancer biology. This illustration depicts the integration of multi-omics techniques, including genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, to comprehensively investigate cancer biology. Genomic profiling identifies frequently mutated genes, such as TP53, KRAS, and PIK3CA. Transcriptomic analysis reveals gene expression changes associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, and immune evasion. Metabolomic profiling aids in early detection, prognosis, and evaluation of therapy response. Proteomic data provide insights into mechanisms like cell migration, invasion, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling.

4.2 Examination of single cells

Single-cell analysis has become an invaluable tool for interrogating intratumoral heterogeneity and the TME to elucidate the dynamic mechanisms underlying cancer invasion and metastasis (206). Conventional bulk profiling averages signals across large cell populations, thereby masking rare but clinically consequential subclones that drive metastatic progression (206). In contrast, single-cell approaches enable the resolution of gene expression, protein activity, and epigenetic states at the individual-cell level, allowing the identification of discrete metastatic subpopulations and the molecular pathways that sustain their invasive phenotypes (207).

Emerging single-cell technologies, including spatial transcriptomics and scRNA-seq, now provide high-resolution maps of tumor ecological structure (208). These approaches have uncovered rare cell states, such as cancer stem-like subpopulations and hybrid E/M phenotypes, which disproportionately contribute to dissemination and therapeutic resistance (209). Additionally, single-cell analysis has delineated complex interactions between malignant cells and immune or stromal elements in the TME, clarifying how microenvironmental cues reinforce invasion and support metastatic colonization (210).

Beyond mechanistic insight, single-cell platforms are increasingly demonstrating direct clinical relevance. Single-cell DNA and multi-omics analyses can reconstruct patient-specific clonal evolution across primary and metastatic lesions and during therapy, enabling the identification of emergent drug-tolerant subclones for timely therapeutic intervention (206–208). Moreover, scRNA-seq profiling of circulating or compartmentalized tumor cells allows early detection of micrometastasis, surpassing the sensitivity of conventional cytology, and supports longitudinal molecular disease monitoring (209–212). Finally, integration of single-cell tumor and immune signatures into machine-learning frameworks is advancing personalized treatment stratification, including predicting response to ICIs and prioritizing rational multi-target drug combinations (150). Together, these advancements position single-cell technologies not only as discovery tools but also as emerging clinical decision-support systems.

4.3 Bioinformatics and computer modeling

Bioinformatics and computational modeling have become indispensable tools for decoding the complex molecular and biophysical mechanisms that drive cancer invasion and metastasis. Machine learning models trained on multi-omics and clinical datasets can stratify patients according to metastatic risk and therapeutic response, improving prognostic precision (213, 214). The reconstruction of signaling networks and virtual drug testing in silico enables data-driven hypothesis generation, prioritization of anti-metastatic targets, and rapid evaluation of therapeutic strategies (215). These computational approaches allow mechanistic exploration of invasion-associated signaling pathways, clonal adaptation, and microenvironmental feedback loops that are difficult to capture experimentally.

By integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, computational models clarify how molecular alterations converge to promote metastatic progression (169). In particular, the combination of multi-omics data with mathematical and machine learning frameworks has transformed metastasis research, accelerating the development of targeted and individualized treatments (216–219). Computational modeling also provides a quantitative foundation for understanding the mechanical determinants of metastasis. Mechanical features of the TME, including stiffness and stress, influence cell migration, invasion, and dissemination (220, 221). Simulating these forces in silico reveals how cancer cells adapt to mechanical constraints and how therapeutic interventions can be designed to modulate these dynamics, potentially reducing metastatic spread.

Bioinformatics complements these efforts by enabling large-scale interpretation of genomic and transcriptomic data to identify key genes, pathways, and biomarkers involved in metastatic progression (222). Through comparative expression and mutation analyses, bioinformatics tools can uncover upregulated and downregulated genes that regulate EMT, immune evasion, and organ-specific colonization. Translational bioinformatics extends this framework to clinical practice by integrating clinical, genetic, and molecular data to identify biomarkers that predict outcomes and therapy responses (223, 224). The development of advanced computational pipelines for next-generation sequencing and real-time molecular monitoring allows detection of resistance mechanisms and adaptation of treatment strategies (225).

Together, the integration of bioinformatics and computational modeling bridges experimental biology with clinical oncology, revealing functional relationships between gene networks, mechanical properties, and metastatic phenotypes. This synergy not only enhances our mechanistic understanding of metastasis but also supports the development of precision therapies tailored to the molecular and physical characteristics of individual tumors. Key computational approaches are summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Integration of bioinformatics and computer modeling approaches in cancer research. The central framework combines four major domains: computational models, machine learning models, translational bioinformatics, and bioinformatics tools. These components work together to facilitate a system-level understanding of cancer biology and support precision oncology applications.

4.4 Gene editing using CRISPR-Cas9

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized cancer research by enabling precise and efficient genome editing. Derived from the adaptive immune system of bacteria and archaea, this tool allows targeted modification of DNA sequences within living cells, facilitating functional gene analysis and the development of novel therapeutic strategies (226, 227). In metastasis research, CRISPR-Cas9 provides a direct means to interrogate causal relationships between specific genes and metastatic behavior. Targeted editing of key regulators such as SNAI1, TWIST1, and MMP9 has clarified their roles in EMT, ECM remodeling, and invasion (226). By functionally dissecting these and related genes, CRISPR approaches reveal hierarchical networks that orchestrate invasion, dissemination, and colonization, thereby identifying potential therapeutic vulnerabilities that cannot be resolved through correlative omics analyses alone.

High-throughput CRISPR screens have further expanded this capability, uncovering novel regulators of cell invasion, survival in circulation, and secondary site colonization (227). Pooled knockout libraries allow systematic assessment of phenotypes such as drug resistance, dormancy, or immune evasion, providing functional validation of metastasis-associated pathways (228). Moreover, CRISPR-based tools are increasingly being integrated into combinatorial studies with transcriptomics and proteomics to map feedback loops that sustain metastatic persistence and therapeutic resistance.

Despite its transformative potential, several challenges limit the clinical translation of CRISPR-Cas9. Off target effects, immunogenicity, and inefficient delivery remain major obstacles that must be overcome to achieve safe and effective therapeutic application (229). Continued refinement of guide RNA design, delivery vectors, and editing precision will be essential for fully realizing CRISPR’s role in dissecting and therapeutically targeting the molecular circuitry of metastasis.

4.5 Liquid biopsy and biomarkers

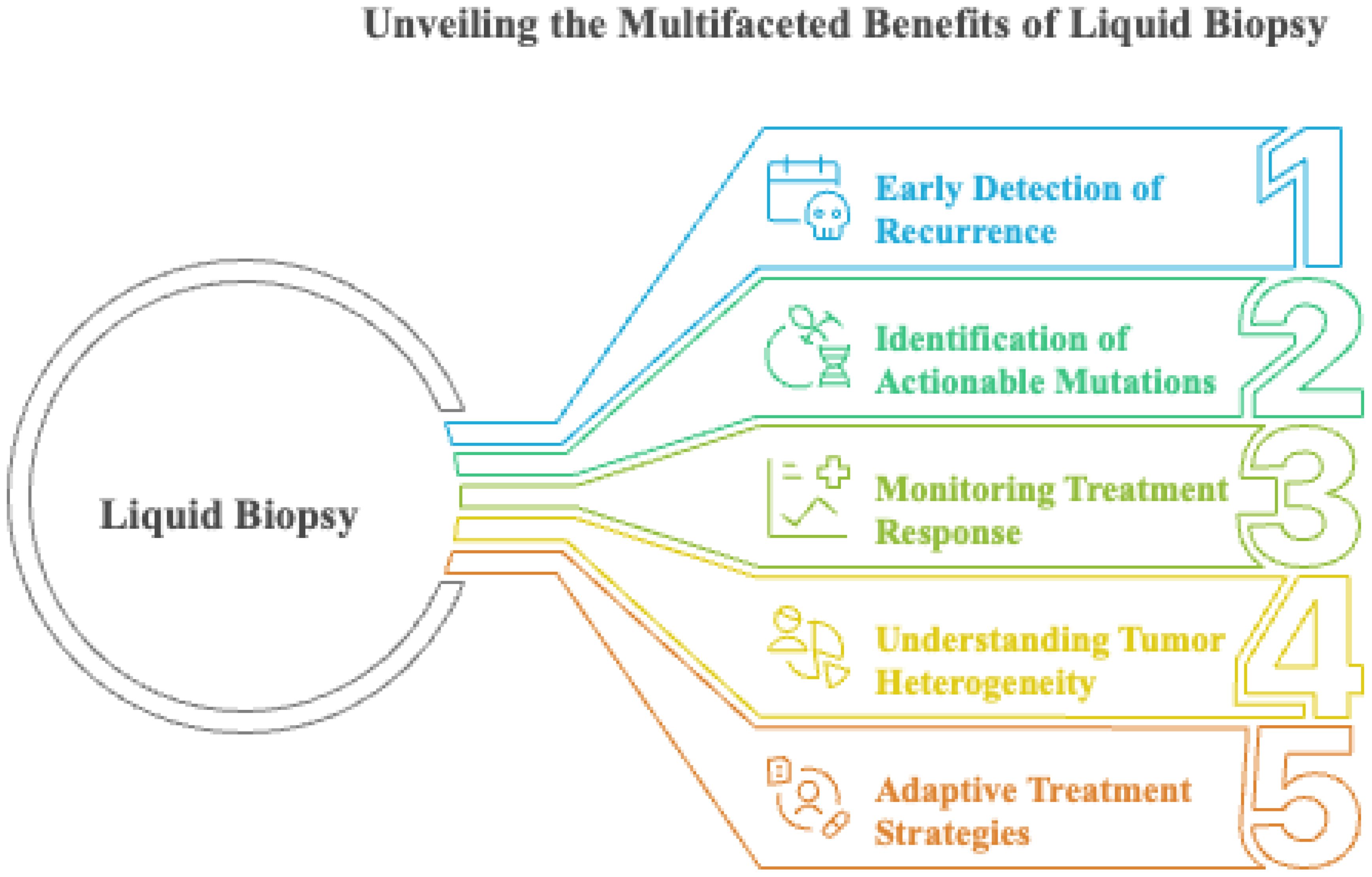

The minimally invasive and unique approach of liquid biopsy shows promise for the dynamic surveillance of tumor metastasis. It could revolutionize cancer management by revealing the changing landscape of the disease. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which are fixed and localized, liquid biopsies can gather CTCs and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from the blood. This helps track disease progression and the efficacy of treatments over time (230). In various metastatic tumors, this technique overcomes the drawbacks of traditional biopsies, which are invasive, expensive, and subject to sample bias (231). Liquid biopsies overcome these limitations by enabling real-time and comprehensive analysis of the cancer genome and tumor heterogeneity. In particular, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis through liquid biopsy offers a viable alternative to traditional methods, enabling the detection of early recurrence and distinguishing tumor progression from pseudo-progression without the need for repeated surgical samples (232). The clinical value of liquid biopsy lies in its ability to identify actionable mutations in metastatic lesions that may not be present in the primary tumor (233). This enables a comprehensive and adaptable understanding of cancer pathology, supporting continuous biomarker monitoring, early detection of therapy resistance, and the discovery of new therapeutic targets.

Liquid biopsy not only enhances treatment monitoring but also accelerates drug development. By monitoring ctDNA levels during therapy, healthcare providers can promptly discover therapeutic responses or resistance and adjust the treatment plan (234). This approach is beneficial for targeted therapies, as it identifies resistance mutations early, allowing for therapeutic adjustments before clinical symptoms appear. Furthermore, liquid biopsies enable drug developers to identify predictive biomarkers and determine which patients are most likely to benefit from new treatments (235).