- 1Department of Thoracic Surgery, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

- 2Department of Anesthesiology, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

Background: The therapeutic value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remains uncertain compared to surgery alone (SA), particularly in real-world settings. This study utilized propensity score matching (PSM) to compare survival outcomes between NAC and surgery in a well-balanced ESCC cohort, while assessing pathological complete response (pCR) and prognostic factors to guide clinical decision-making.

Methods: The study conducted a retrospective analysis of 690 patients with locally advanced ESCC (T3-4aN0-3M0) who underwent radical esophagectomy between 2009 and 2019. PSM was employed to balance baseline characteristics, yielding 452 matched patients (135 NAC, 317 SA). NAC consisted of platinum-based doublet regimens. Survival outcomes, including disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression methods. pCR were assessed using CAP criteria.

Results: NAC significantly improved 5-year DFS (28.7% vs. 18.5%, P = 0.001) and OS (37.9% vs. 24.2%, P = 0.001) compared to SA. Patients achieving pCR (11.9%) exhibited superior DFS (5-year: 55.0% vs. 18.5%, P = 0.010) and OS (5-year: 59.8% vs. 35.0%, P = 0.019). Multivariate analysis identified NAC, histologic grade, ypN stage, vessel/nerve invasion, and pCR as independent prognostic factors.

Conclusions: This real-world data supports that NAC significantly improves survival outcomes compared to SA in locally advanced ESCC. pCR post-NAC independently predicted improved OS.

1 Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remains one of the most aggressive malignancies worldwide, with locally advanced disease presenting particularly poor prognosis (1, 2). While surgical resection forms the cornerstone of treatment, the 5-year survival rates for surgery alone remain dismal, rarely exceeding 25% (3). This sobering reality has driven the development of multimodal approaches, with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) emerging as the current standard based on landmark trials including CROSS (4) and NEOCRTEC 5010 (5).

While the landmark CROSS and NEOCRTEC 5010 trials established NCRT as the standard of care for locally advanced ESCC, demonstrating significant survival benefits. However, most of these trials and studies have focused on data from esophageal cancer patients in Western countries, where the predominant pathological type is adenocarcinoma. Thus, their guidance for the treatment of ESCC is limited. In addition, a study by Ken Kato et al. (6) based on an Asian population with ESCC showed that, compared to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), NCRT did not significantly improve patient survival rates. Moreover, the incidence of treatment-related adverse events and postoperative complications was higher with NCRT than with NAC (7, 8). On the other hand, the role of NAC remains controversial and less well-defined. While some studies suggest comparable efficacy between NAC and NCRT (6–10), others report inferior outcomes with chemotherapy alone (7). This controversy stems from several critical knowledge gaps: (1) limited real-world evidence comparing NAC directly with SA in rigorously matched cohorts, (2) uncertainty regarding pathological complete response (pCR) rates and their prognostic significance in NAC-treated ESCC, and (3) inadequate understanding of predictive biomarkers for chemotherapy response.

To address these gaps, we conducted a large-scale real-world study to retrospectively analyze patients with locally advanced ESCC (T3-4aN0-3M0) who underwent radical esophagectomy at our center. Using propensity score matching (PSM) analysis of the enrolled cohort, performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and multivariate Cox regression to identify prognostic factors influencing outcomes in ESCC patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These findings provide an evidence-based theoretical foundation for optimizing personalized treatment strategies for this patient population.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and patient selection

This study was a real-world retrospective analysis with PSM to investigate the survival outcomes of patients with locally advanced ESCC who received platinum-based doublet chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment at The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2009 and January 2019. Eligible patients met the following criteria: (1) underwent radical esophagectomy; (2) tumor located in the thoracic esophagus; (3) histologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma; (4) clinical stage (neoadjuvant chemotherapy group) or pathological stage (surgery-alone group) classified as T3–4aN0–3M0 according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for esophageal cancer (11); (5) complete clinical data available. Patients were excluded if they had (1) perioperative mortality; (2) patients who received any additional anticancer therapy (such as radiotherapy or immunotherapy) during or after the neoadjuvant chemotherapy; (3) received fewer than 2 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy; (4) intraoperative lymph node dissection with fewer than 15 nodes harvested.

Diagnosis and clinical staging were determined using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and cervical ultrasonography. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was additionally performed of necessary. The pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy was evaluated according to the College of American Pathologists (CAP) tumor regression grading system (12).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (NO.2022MECD58) and was strictly conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised 2013).

2.2 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy before radical resection of esophageal cancer

The neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens were administered according to contemporary NCCN and CSCO guidelines. According to the drug instructions, patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a platinum-based doublet regimen consisting of paclitaxel (175 mg/m² intravenously on day 1) combined with either carboplatin (300 mg/m² intravenously on day 2) or cisplatin (15 mg/m²/day intravenously on days 1-5), administered in 3–4 week cycles. The treatment comprised 2–4 cycles, followed by surgical resection 4–6 weeks after completion of chemotherapy.

2.3 Surgical procedure for radical resection of esophageal cancer

All patients underwent standardized radical esophagectomy using either the Ivor-Lewis approach (open or minimally invasive) with right thoracic esophagogastric anastomosis or the McKeown approach (open or minimally invasive) with cervical anastomosis.

2.4 Follow-up

The follow-up information was obtained through our hospital’s follow-up center by means of phone calls, letters, and review of inpatient and outpatient records. The follow-up started from the date of the surgery and was calculated monthly until the last follow-up or the date of the clinical event occurred. The follow-up deadline was December 2024. Patients who failed to respond to two consecutive follow-up reminders were defined as lost to follow-up. In the survival analysis, these patients were censored at the date of the first missed follow-up. The follow-up content for postoperative patients included clinical symptoms, signs, and results of various examinations and tests. The examinations included gastrointestinal radiography, gastroscopy, computed tomography (CT) (head, chest and abdominal), ultrasound, etc. Hematological tests included tumor markers, etc. If necessary, tissue pathological biopsy was performed to determine whether there was recurrence and/or metastasis. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from surgery to disease recurrence. Local or lymph node recurrence and metastatic diseases were considered as indications of recurrence of the primary tumor. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death due to any cause, and the longest follow-up time was used as the termination criterion.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies with percentages. For survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier estimates were generated and compared using log-rank tests in univariate analysis. Variables demonstrating significant associations (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were subsequently included in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models with forward selection to identify independent prognostic factors for survival outcomes. All P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Basic characteristics of participants

Between January 2009 and January 2019, 703 patients with locally advanced ESCC who underwent surgical resection at our center were initially reviewed. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 690 eligible patients with complete clinical and follow-up data were included in this study. Of these, 138 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by surgery, while 552 underwent surgery alone (SA). The baseline characteristics of the entire cohort are summarized in Table 1.

To mitigate potential selection bias, we performed a one-to-three PSM analysis (nearest-neighbor matching, caliper=0.1) using the NAC group as the reference. Matching variables included tumor location, regional lymph nodes status, clinical T stage, histologic grade, surgical approach,vessel or nerve invasion. After PSM, the final analysis included 452 patients, 135 patients in the NAC group and 317 patients in the SA group, respectively. The baseline clinical characteristics were well balanced after PSM between two groups (Table 1).

3.2 Evaluation of disease-free survival and overall survival

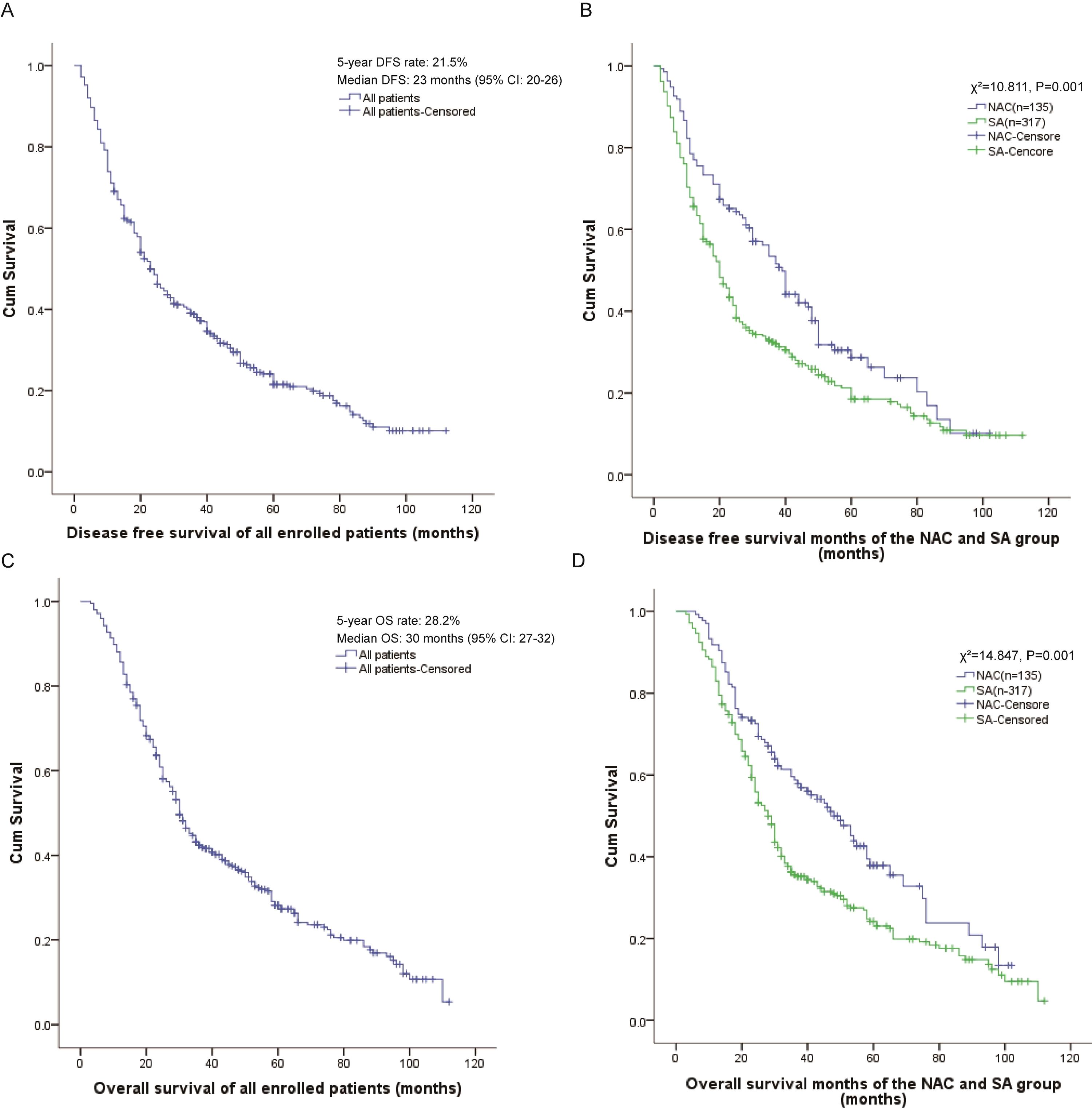

At the final follow-up, the overall cohort population demonstrated a 5-year DFS rate of 21.5% with a median DFS of 23 months (95% CI: 20-26) (Figure 1A). Comparative analysis revealed significant survival benefit in the NAC group, which exhibited superior 5-year DFS (28.7% vs. 18.5%; P = 0.001) and prolonged median DFS (39 months, 95% CI: 34–44 vs. 20 months, 95% CI: 17-23; χ²=10.811, P = 0.001) compared to the SA group (Figure 1B).

Similarly, survival analysis revealed a 5-year OS rate of 28.2% and median OS of 30 months (95% CI: 27-32) for the overall population (Figure 1C). Notably, the neoadjuvant chemotherapy arm maintained a significant survival advantage, demonstrating both higher 5-year OS (37.9% vs. 24.2%; P = 0.001) and extended median OS (48 months, 95% CI: 38–58 vs. 28 months, 95% CI: 25-31; χ²=14.847, P = 0.001) relative to SA group (Figure 1D).

3.3 Comparisons between pathological response, DFS and OS subgroups

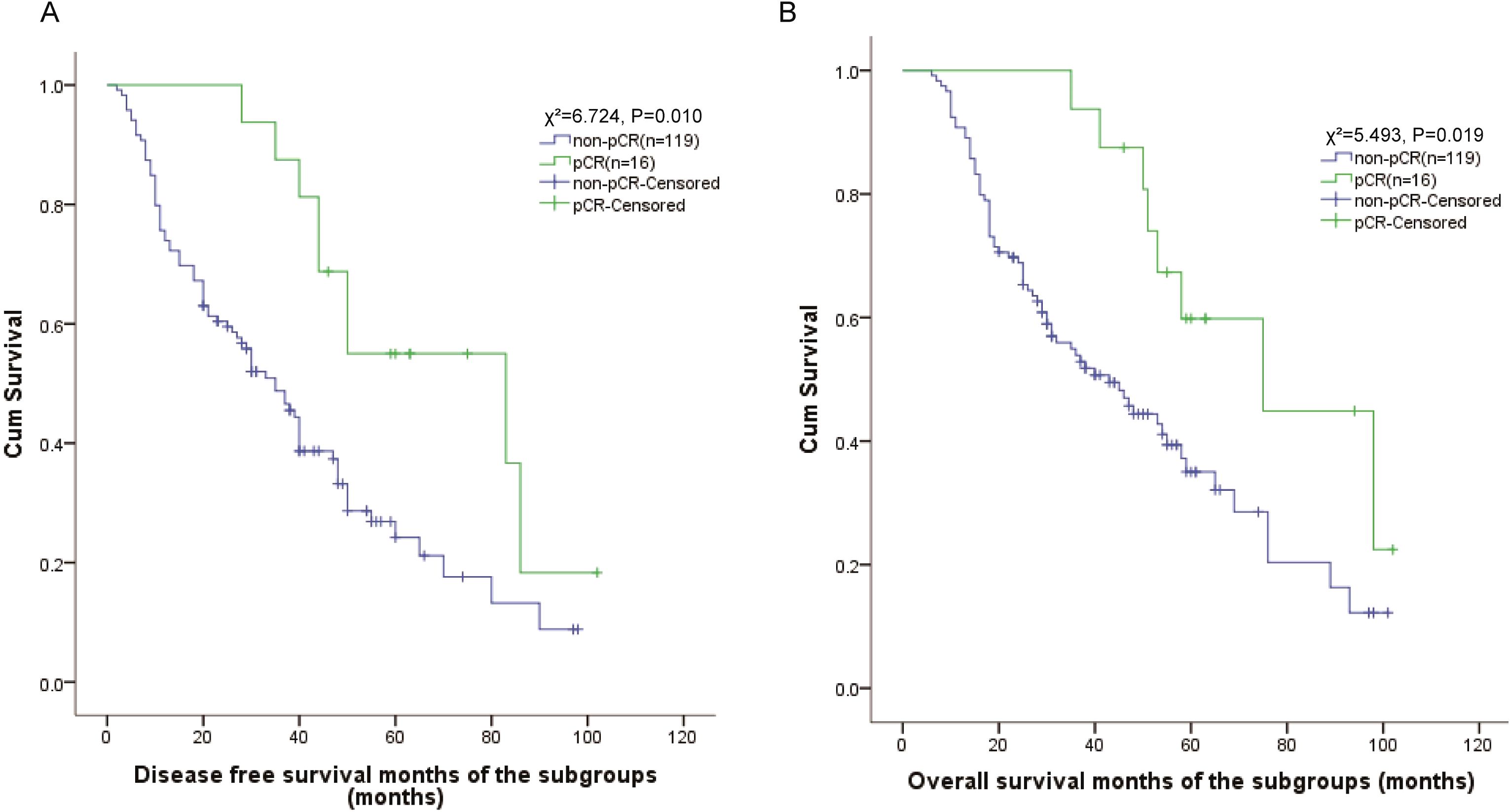

To further investigate prognostic factors in locally advanced ESCC, we performed subgroup analysis of 135 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Pathological complete response (pCR) was achieved in 16 patients (11.9%). Kaplan-Meier survival analyses revealed significantly superior outcomes in pCR patients compared to non-pCR cases. Patients achieving pCR showed markedly improved DFS outcomes compared to non-pCR patients, with 5-year DFS rates of 55.0% vs. 18.5% (χ²=6.724, P = 0.010). The median DFS was 83 months (95% CI: 22-144) in pCR patients compared to 35 months (95% CI: 27-43) in non-pCR patients (Figure 2A).

Similarly, OS analysis demonstrated superior outcomes for pCR patients, with 5-year OS rates of 59.8% versus 35.0% in non-pCR patients (χ²=5.493, P = 0.019). The median OS was 75 months (95% CI: 40-111) in the pCR group compared to 43 months (95% CI: 30-56) in the non-pCR group (Figure 2B).

3.4 Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of DFS and OS

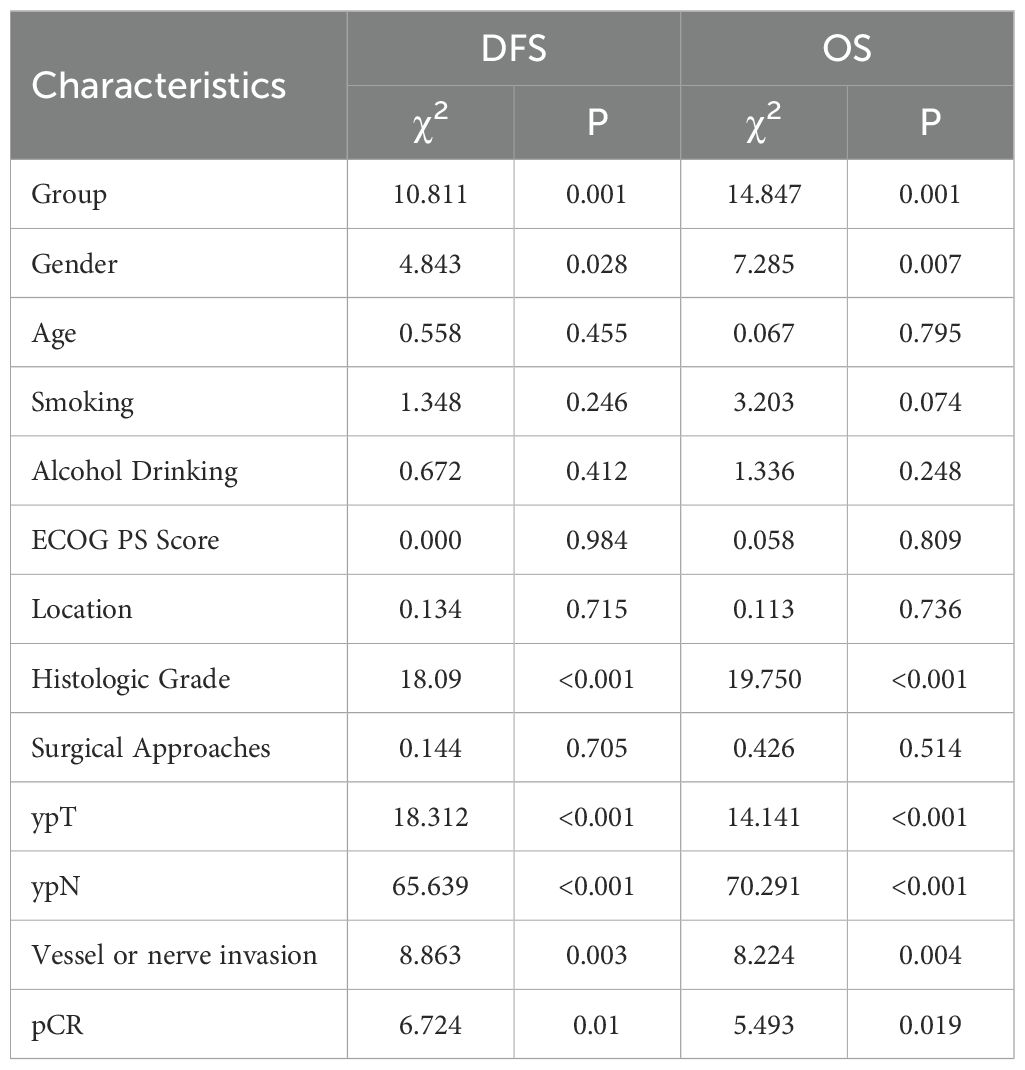

Subsequently, univariate analyses were performed to identify variables potentially influencing DFS and OS. As shown in Table 2, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (χ²=10.811, P = 0.001), gender (χ²=4.843, P = 0.028), histologic grade (χ²=18.090, P < 0.001), ypT stage (χ²=22.136, P < 0.001), ypN stage (χ²=65.639, P < 0.001), vessel or nerve invasion (χ²=8.863, P = 0.003) and pCR (χ²=18.312, P < 0.001) as factors significantly associated with DFS. Similar variables were predictive of OS, including neoadjuvant chemotherapy (χ²=14.847, P = 0.001), gender (χ²=7.285, P = 0.007), histologic grade (χ²=19.750, P < 0.001), ypT stage (χ²=14.141, P < 0.001), ypN stage (χ²=70.291, P < 0.001), vessel or nerve invasion (χ²=8.224, P = 0.004), and pCR (χ²=5.493, P = 0.019) (Table 2).

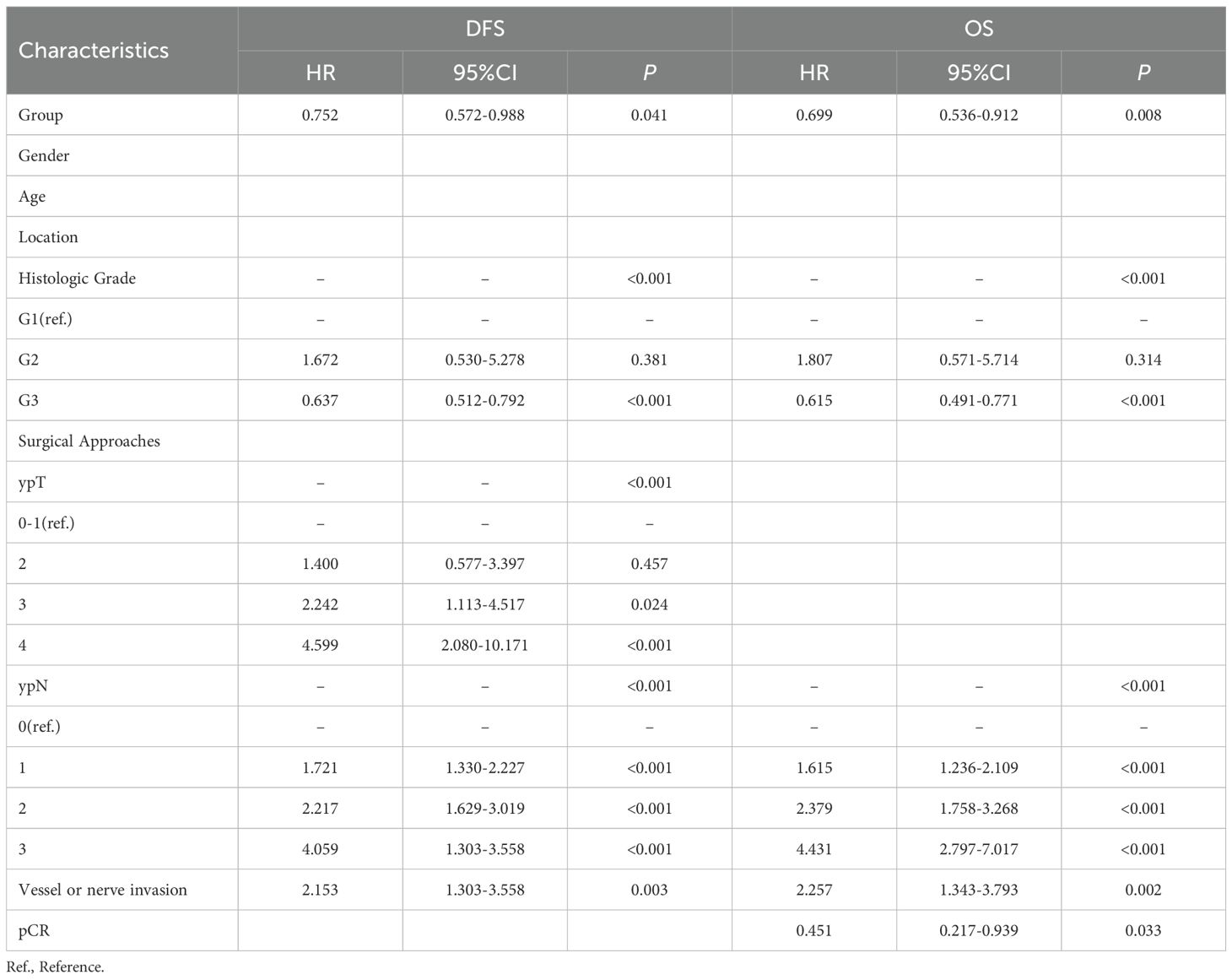

To further investigate potential prognostic factors for DFS and OS, we conducted multivariate Cox regression analyses. The results identified the following as independent prognostic factors for DFS: neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a protective factor (HR: 0.752, 95% CI: 0.572–0.988, P = 0.041), and histologic grade (HR:0.637, 95% CI:0.512-0.792, P < 0.001 (G3 vs. G1)), ypT stage (HR: 2.242, 95% CI: 1.113-4.517, P = 0.024 (T3 vs. T0-1); HR: 4.599, 95% CI: 2.080-10.171, P < 0.001 (T4 vs. T0-1)), ypN stage (HR: 1.721, 95% CI: 1.330-2.227, P < 0.001 (N1 vs. N0); HR: 2.217, 95% CI: 1.629-3.019, P < 0.001 (N2 vs. N0); HR: 4.059, 95% CI: 1.303-3.558, P < 0.001 (N3 vs. N0)) as well as vessel or nerve invasion (HR: 2.153, 95% CI: 1.303–3.558, P = 0.003) as independent risk factors (Table 3). For OS, independent factors were neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR: 0.699, 95% CI: 0.536–0.912, P = 0.008), histologic grade (HR:0.615, 95% CI:0.491-0.771, P < 0.001 (G3 vs. G1)), ypN stage (HR: 1.615, 95% CI: 1.236-2.109, P < 0.001 (N1 vs. N0); HR: 2.379, 95% CI: 1.758-3.268, P < 0.001 (N2 vs. N0); HR: 4.431, 95% CI: 2.797-7.017, P < 0.001 (N3 vs. N0)), vessel or nerve invasion (HR: 2.257, 95% CI: 1.343–3.793, P = 0.002), and pCR (HR: 0.451, 95% CI: 0.217–0.939, P = 0.033) (Table 3).

Collectively, both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses confirmed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen, histologic grade, ypN stage, vessel or nerve invasion, and pCR were independent prognostic factors associated with DFS and OS.

4 Discussion

This retrospective study demonstrates that NAC followed by surgery significantly improves both DFS and OS compared to SA in patients with locally advanced ESCC. After PSM minimized selection bias, NAC was associated with superior 5-year DFS and OS. These findings align with prior evidence suggesting a survival benefit for NAC in ESCC (13–15).

Although the NCCN guidelines and other studies recommend neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) as a standard for esophageal cancer (4, 14, 16), their applicability to ESCC is limited, as they are primarily derived from Western populations where adenocarcinoma predominates. This limitation is underscored by a Japanese study focusing on Asian ESCC patients, which found that NCRT did not confer a significant survival advantage over NAC and was associated with a higher incidence of treatment-related adverse events and postoperative complications (6). In this context, our findings provide novel and compelling insights into the ongoing debate regarding NAC as a viable alternative. Our study is distinctive in its focus on demonstrating the direct survival benefit of NAC over surgery alone in a real-world setting, thereby offering robust evidence for its clinical utility. Furthermore, our analysis incorporated detailed pathological assessments, including vessel or nerve invasion and CAP (Ryan) grading, which are critical prognostic factors often underreported in comparable studies.

A key innovation of this study lies in its comprehensive evaluation of pCR as a prognostic marker in NAC-treated ESCC patients. We not only confirmed that pCR was associated with significantly improved survival (17, 18) but also demonstrated its independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis. This finding is particularly relevant given the scarcity of large-scale studies examining pCR rates and their clinical implications specifically in NAC-treated ESCC, as most prior research has focused on NCRT (17). Our results suggest that pCR could serve as an early surrogate endpoint for treatment efficacy in NAC regimens, warranting further investigation in prospective trials. It is noteworthy that the pCR rate observed with NAC in this study was relatively low, a finding consistent with the results of the Japanese JCOG1109 trial (5%) and the study of Klevebro et al. (6, 19) but in stark contrast to the higher pCR rates typically achievable with NCRT (20). This discrepancy likely stems from fundamental differences in the mechanisms of action and pathological responses between the two modalities. NCRT combines the systemic effects of chemotherapy with the potent local intensification provided by radiotherapy, leading to more effective eradication of the primary tumor and consequently higher pCR rates. In contrast, NAC relies primarily on systemic chemotherapy, with its key objectives being the eradication of micrometastases and tumor downstaging. This may explain why NAC has a lower pCR compared to NCRT.

Additionally, our study advances the understanding of prognostic factors in NAC-treated ESCC by identifying vessel or nerve invasion as a strong independent predictor of poor outcomes. While previous studies have linked vessel or nerve invasion to adverse prognosis in ESCC (21–23), our work is among the few to validate its significance specifically in the NAC context, providing clinicians with valuable risk stratification tools. The inclusion of these pathological features in our multivariate model adds granularity to existing prognostic frameworks and may guide postoperative adjuvant therapy decisions.

While this real-world study provides valuable insights into the clinical outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ESCC, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, while the retrospective design enhances the generalizability of our findings to real-world clinical practice, it may introduce inherent selection biases, despite our use of PSM to mitigate this concern. Furthermore, this study conducted numerous exploratory subgroup analyses to identify potential prognostic factors. However, these analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, which inherently increases the risk of false-positive findings. Consequently, these results should be interpreted with caution and considered hypothesis-generating, requiring validation through future multi-center, prospective, randomized controlled trials. Second, as a single-center study, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by institutional-specific treatment protocols and patient populations. Although our current findings provide a theoretical basis for the application of NAC in ESCC, the inherent limitations of this single-center retrospective study necessitate further validation through multi-center, large-scale clinical trials. Third, despite effectively documenting survival endpoints, our study is subject to the inherent limitations of a retrospective design, including the lack of systematic data on treatment-related toxicity and patient quality of life. This gap prevents a comprehensive risk-benefit evaluation. It is therefore imperative that future prospective studies concurrently evaluate survival, toxicity, and patient-reported outcomes to guide optimal clinical decision-making. Finally, the evolving landscape of ESCC treatment, including emerging immunotherapies and targeted therapies, highlights the need for future prospective studies incorporating comprehensive biomarker analyses and standardized response assessment criteria to further optimize treatment strategies.

Our study not only reinforces the survival benefit of NAC in locally advanced ESCC but also introduces several novel contributions: (1) a PSM-balanced analysis confirming NAC’s efficacy versus surgery alone, (2) robust evidence for pCR as a prognostic marker in NAC-treated ESCC, and (3) validation of vessel or nerve invasion as key pathological risk factors. These findings underscore NAC as a valuable alternative to NCRT in select patients and point to a clear future direction: investigating biomarkers of chemotherapy sensitivity, such as ERCC1, could help identify patients most likely to derive significant benefit from NAC. The development of an integrated predictive model combining these biomarkers with clinical data is the logical next step towards tailoring neoadjuvant therapy, thereby optimizing outcomes and quality of life for individual patients.

With the evolving landscape of ESCC treatment, immunotherapy and targeted therapy have emerged as highly promising paradigms for future precision oncology. However, the relatively recent introduction of these modalities in our region means that robust long-term survival data are not yet available. Consequently, reliable comparisons regarding their efficacy and potential advantages over NAC remain elusive. In response to this knowledge gap, our center has initiated the systematic collection and follow-up of relevant data. Future work will focus on a more comprehensive and scientific analysis of the impact of NAC, NCRT, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy on survival outcomes in patients with ESCC.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee of The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical (NO.2022MECD58). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YW: Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation. ZY: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Methodology. ZL: Validation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. JY: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision. JFY: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Supervision. JFL: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was funded by the Key Medical Scientific Research Project of Hebei province (No. 20260511) and Hebei Natural Science Foundation (Approval No. H2021206233).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1691998/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Puhr HC, Prager GW, and Ilhan-Mutlu A. How we treat esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. ESMO Open. (2023) 8:100789. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100789

2. Sun R, Tian L, and Wei LJ. Evaluating long-term efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for the treatment of locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Surg. (2022) 157:458–9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.7113

3. Herskovic A, Russell W, Liptay M, Fidler MJ, and Al-Sarraf M. Esophageal carcinoma advances in treatment results for locally advanced disease: review. Ann Oncol. (2012) 23:1095–103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr433

4. van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:2074–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088

5. Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, Zhu C, Fang W, Yu Z, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (NEOCRTEC5010): A phase III multicenter, randomized, open-Label clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:2796–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.1483

6. Kato K, Machida R, Ito Y, Daiko H, Ozawa S, Ogata T, et al. Doublet chemotherapy, triplet chemotherapy, or doublet chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced oesophageal cancer (JCOG1109 NExT): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2024) 404:55–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00745-1

7. Chan KKW, Saluja R, Delos Santos K, Lien K, Shah K, Cramarossa G, et al. Neoadjuvant treatments for locally advanced, resectable esophageal cancer: A network meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. (2018) 143:430–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31312

8. Zhao X, Ren Y, Hu Y, Cui N, Wang X, and Cui Y. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for cancer of the esophagus or the gastroesophageal junction: A meta-analysis based on clinical trials. PloS One. (2018) 13:e0202185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202185

9. Tang H, Wang H, Fang Y, Zhu JY, Yin J, Shen YX, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by minimally invasive esophagectomy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective multicenter randomized clinical trial. Ann Oncol. (2023) 34:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.508

10. Zhan M, Zheng H, Yang Y, Xu T, and Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma based on the NEOCRTEC5010 trial. Radiother Oncol. (2019) 141:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.07.031

11. Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Kelsen DP, Hofstetter WL, Apperson-Hansen C, and Blackstone EH. Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration I: Recommendations for neoadjuvant pathologic staging (ypTNM) of cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction for the 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging manuals. Dis Esophagus. (2016) 29:906–12. doi: 10.1111/dote.12538

12. Ryan R, Gibbons D, Hyland JM, Treanor D, White A, Mulcahy HE, et al. Pathological response following long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Histopathology. (2005) 47:141–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02176.x

13. Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Zalcberg JR, Simes RJ, Barbour A, et al. Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials G: Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2011) 12:681–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5

14. Yang Y, Shao R, Cao X, Chen M, Gong W, Ying H, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiother Oncol. (2024) 200:110517. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2024.110517

15. Duan X, Zhao F, Shang X, Yue J, Chen C, Ma Z, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy was associated with better short-term survival of patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma compared to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Med. (2024) 13:e70113. doi: 10.1002/cam4.70113

16. Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2023) 21:393–422. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0019

17. Yuan J, Weng Z, Tan Z, Luo K, Zhong J, Xie X, et al. Th1-involved immune infiltrates improve neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy response of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. (2023) 553:215959. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215959

18. Lu SL, Hsu FM, Tsai CL, Lee JM, Huang PM, Hsu CH, et al. Improved prognosis with induction chemotherapy in pathological complete responders after trimodality treatment for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Hypothesis generating for adjuvant treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2019) 45:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.03.020

19. Klevebro F, Alexandersson von Döbeln G, Wang N, Johnsen G, Jacobsen AB, Friesland S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for cancer of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction. Ann Oncol. (2016) 27:660–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw010

20. Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof M, van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:1090–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6

21. Ma Y, Chen J, Yao X, Li Z, Li W, Wang H, et al. Patterns and prognostic predictive value of perineural invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:1287. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-10386-w

22. Gao A, Wang L, Li J, Li H, Han Y, Ma X, et al. Prognostic value of perineural invasion in esophageal and esophagogastric junction carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Dis Markers. (2016) 2016:7340180. doi: 10.1155/2016/7340180

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, pathological complete response, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, survival benefits, survival outcomes

Citation: Wang Y, Yue Z, Li Z, Yang J, Yao J and Liu J (2025) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity-matched real-world study. Front. Oncol. 15:1691998. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1691998

Received: 25 August 2025; Accepted: 06 November 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Yan Zheng, Henan Provincial Cancer Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Yadong Wang, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), ChinaXiaozheng Kang, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, China

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Yue, Li, Yang, Yao and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junfeng Liu, bGl1amZAaGVibXUuZWR1LmNu; Jifang Yao, eWFvamlmYW5nMjAyM0AxMjYuY29t

Yuchen Wang1

Yuchen Wang1 Zhifeng Li

Zhifeng Li Jifang Yao

Jifang Yao Junfeng Liu

Junfeng Liu