- Department of Anesthesiology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Background: The impact of dexmedetomidine (DEX) on postoperative survival outcomes in cancer remains controversial. Our study aimed to investigate the influence of intraoperative DEX administration on postoperative mortality outcomes in colorectal cancer patients.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study of adult patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery in a large academic hospital in southern China between 2011 and 2018. Patients were divided into two groups: the DEX group, in which patients received intravenous DEX during the operation, and the non-DEX group. The primary endpoint was overall death or tumor recurrence, deriving two outcome variables: “all-cause death” and “recurrence or death.” Secondary endpoints included total hospital stay, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. Multivariable Cox regression and propensity score matching were used to control confounders.

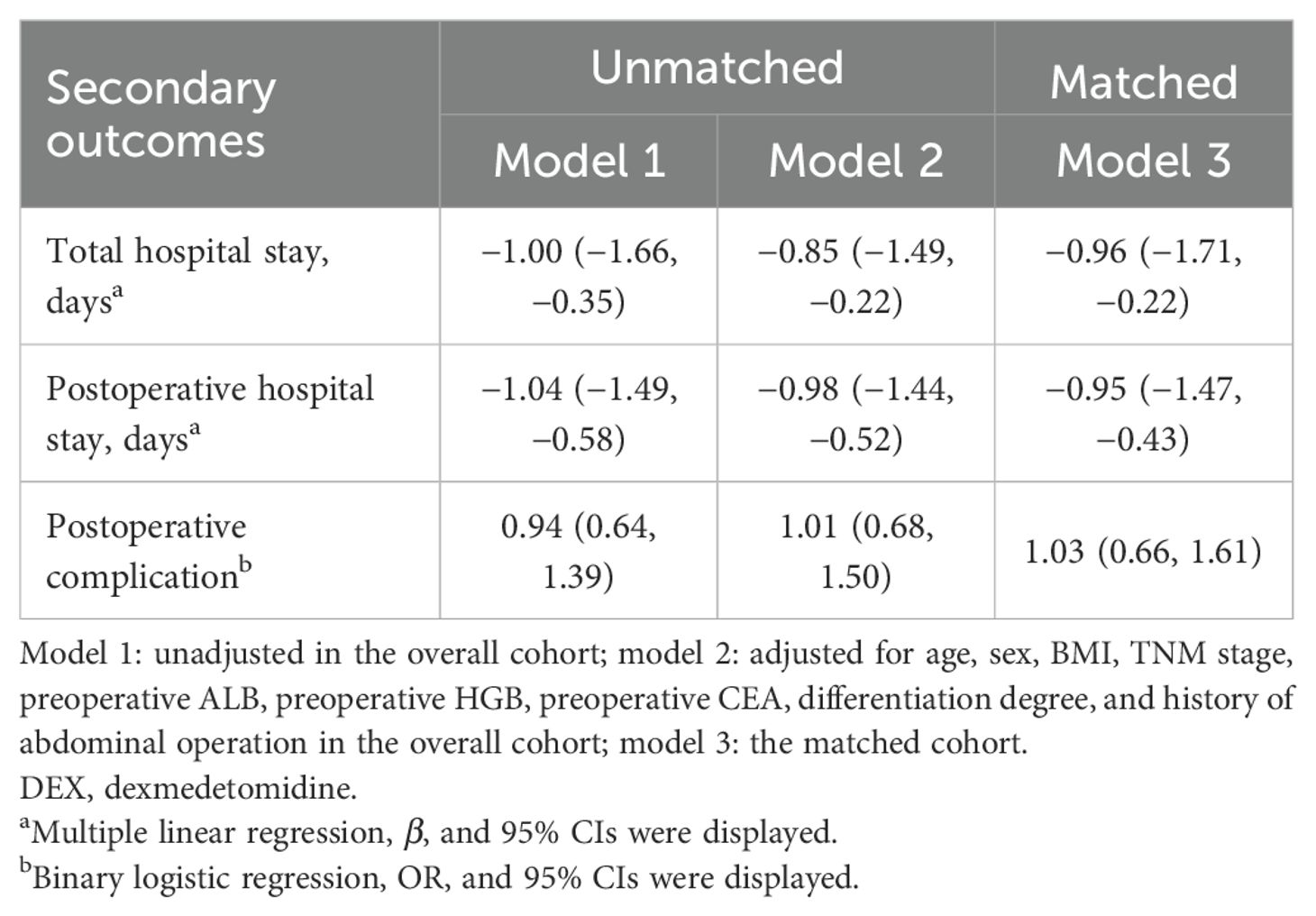

Results: A total of 1,367 adult patients were included, of which 485 pairs were matched. Patients who received intraoperative DEX had a lower all-cause death rate (8.0% vs. 14.2%, P = 0.002) and a lower recurrence or death rate (14.8% vs. 23.1%, P = 0.001). Intraoperative DEX administration was associated with a lower risk of all-cause death postoperatively [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.74, 0.52–1.07 in overall patients; 0.66, 0.45–0.98 in matched patients] compared with non-DEX. The risk of recurrence or death was lower with a marginal significance (HR and 95% CI: 0.75, 0.56–1.01) in matched patients. The total hospital stay and postoperative hospital stay were lower in patients who used DEX than those who did not use it (β and 95% CI: −0.96 [−1.71, −0.22] and −0.95 [−1.47, −0.43], respectively, in matched patients). Meanwhile, the risk of postoperative complications was not associated with DEX.

Conclusions: In patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery, intraoperative DEX administration was associated with better postoperative survival.

Introduction

With the increasing aging population, the incidence of cancer has risen rapidly. According to global cancer statistics, the number of new colorectal cancer cases exceeded 1.9 million in 2020, with an estimated 940,000 deaths, making it the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1). Surgery is the main treatment for patients with non-metastasized colorectal cancer (2), but the use of anesthesia drugs during the intraoperative period may affect the metastasis and spread of cancer, thereby potentially impacting its survival outcomes (3, 4). Therefore, it is urgent to explore the appropriate anesthesia agents to improve postoperative survival outcomes.

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a highly selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist with anti-sympathetic, anxiolytic, and sedative properties (5), has been utilized in intensive care units and is now widely used as a relatively new anesthetic by anesthesiologists (6). Its use in patients with cancer surgery remains controversial due to conflicting findings from various studies. Studies have shown that DEX can reduce antitumor immunity, promote tumor growth and metastasis (7–9), and even decrease the postoperative overall survival in patients who underwent lung cancer surgery (10). Conversely, studies have suggested that DEX could inhibit the growth of various cancer cells, such as ovarian cancer cells, lung adenocarcinoma cells, and esophageal cancer cells, which might help improve postoperative outcomes (11–13). Moreover, a clinical study has shown that DEX can alleviate postoperative immunosuppression and improve postoperative outcomes in oral cancer patients (14).

Based on these controversial reports, DEX may have opposite postoperative outcomes for different cancers. We hypothesized that DEX might improve postoperative survival outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer because of its antitumor effects, reduced stress and inflammatory response, and protection of immune function (15, 16). Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate the influence of intraoperative DEX administration on postoperative survival outcomes in colorectal cancer patients.

Methods

Study design and participants

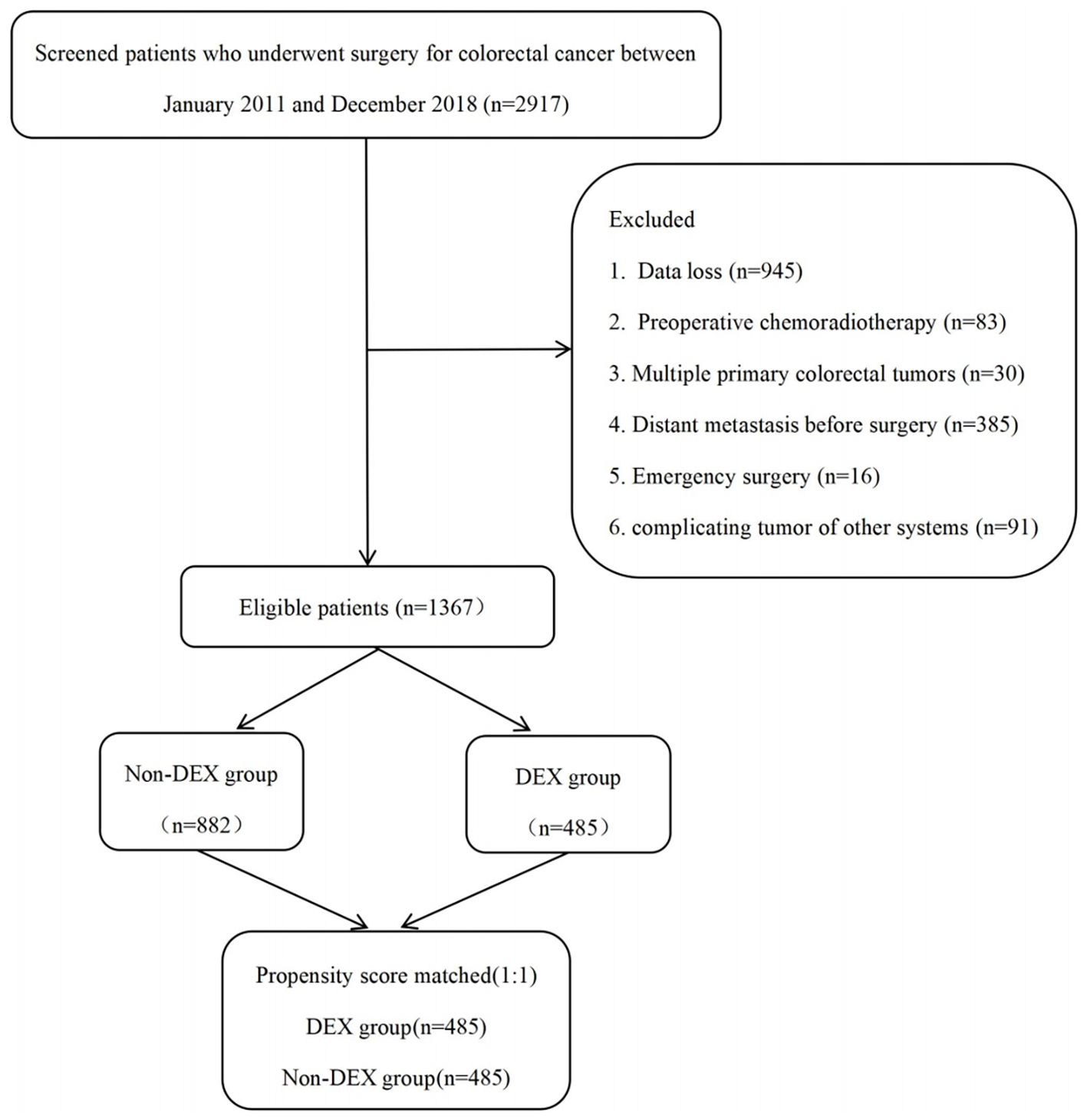

This was a retrospective analysis from a large tertiary academic hospital in southern China. After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (NFEC-2020-050, 24 March 2020), the study cohort included patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery between January 2011 and December 2018 at Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University. Adult patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery under general anesthesia were included in the analysis, and all patients were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition manual for colorectal cancer. All anesthetics used by the patients included inhaled anesthetics, intravenous anesthetics, opioids, and muscle relaxants with non-depolarizing agents. The patient selection flowchart is presented in Figure 1. The exclusion criteria included the following: 1) data loss (n = 945); 2) preoperative chemoradiotherapy (n = 83); 3) presence of multiple primary colorectal tumors (n = 30); 4) distant metastasis before surgery (n = 385); 5) emergency surgery due to conditions such as intestinal obstruction, bleeding, or perforation (n = 16); and 6) complicating tumor of other systems (n = 91). Finally, 1,367 patients were included, of which propensity score matching (PSM) acquired 485 pairs.

Clinical data collection

Clinical data were collected using Perioperative Data Warehouse from the Department of Anesthesiolgy, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), preoperative hemoglobin (HGB), preoperative albumin (ALB), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, comorbidities, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, tumor location, tumor differentiation, pathological tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, surgical type, previous abdominal surgery, the duration of operation, intraoperative blood loss, total intraoperative infusion volume and blood transfusion, postoperative chemotherapy, postoperative ICU (intensive care unit admission), total hospital stay, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. We also collected information on the total amount of DEX administered perioperatively. DEX exposure was defined as continuous intravenous infusion initiated after anesthesia induction and before the end of surgery. The infusion rate ranged from 0.2 to 0.7 μg/kg/h, with a median total dose of 60 μg. Patients who did not receive DEX during this intraoperative period were assigned to the non-DEX group.

Long-term follow-up and outcomes

Long-term follow-up of postoperative mortality and tumor recurrence was performed by investigators who had no knowledge of group assignment and who had been trained for follow-up data collection. Telephone follow-up was utilized to access patient survival information. The primary endpoint of this study was the overall death or tumor recurrence following colorectal cancer surgery, deriving two outcome variables: “all-cause death” and “recurrence or death.” Secondary outcomes included total hospital stay, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications, including wound infection, anastomotic leakage, pulmonary infections, and complications related to urinary retention or bacteremia. Survival time was defined as the duration from the day of colorectal cancer surgery until death from any cause following surgery during follow-up. Disease-free survival time referred to the period from the day of colorectal cancer surgery until either tumor recurrence or death from any cause during the follow-up. Tumor recurrence was confirmed by radiological or pathological evidence.

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the Student’s t-test. Continuous variables with a non-normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies with percentages and compared using the χ² test or continuity-corrected χ² test.

Cox proportional hazard regression analyses with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI were used to estimate mortality risk. Survival proportion was compared using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. Covariates for the multivariable Cox models were selected based on clinical relevance and prior published studies. Preoperative factors were included as confounders, as they influence the exposure factor but are not affected by it. Since DEX was used immediately after anesthesia induction, the intraoperative variables could not affect the exposure factor; thus, these variables were not suitable as confounders. Therefore, the confounder factors in this study included age, sex, BMI, preoperative HGB, preoperative ALB, ASA grade, history of abdominal operation, preoperative CEA, surgery type (open surgery or laparoscopic surgery), TNM stage, differentiation degree, tumor location, and preoperative comorbidity. The Schoenfeld residual method was used to test the proportional hazards assumption, and no significant violations were detected (Supplementary Table S1). Two models were applied: model 1 was unadjusted, while model 2 was adjusted for the above confounder factors, in which the comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease.

Propensity score matching analysis with a 1:1 ratio was used to verify the robustness of the results. The logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity score, with DEX as the dependent variable and all confounder factors mentioned above as matching variables. Propensity score matching was performed using a nearest-neighbor algorithm without replacement, with a caliper value of 0.2 SD of the logit of the propensity score. In the matched cohort, 485 patients were selected for each group. The patients in the DEX and non-DEX groups demonstrated improved homogeneity after matching (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). A love plot with standard mean difference (SMD) was used to evaluate the balance between matched groups, with SMD <0.1 indicating balance (Supplementary Figure S3).

The association of DEX with total hospital stay and postoperative hospital stay was assessed using multiple linear regression with coefficients (β) and 95% CIs. The hypothesis test that satisfied the assumptions of linear regression was performed (Supplementary Tables S2, S3; Supplementary Figures S4-S7). A logistic regression model with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs was used to determine the association of DEX with postoperative complications. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P-values <0.05 for the two-sided test were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

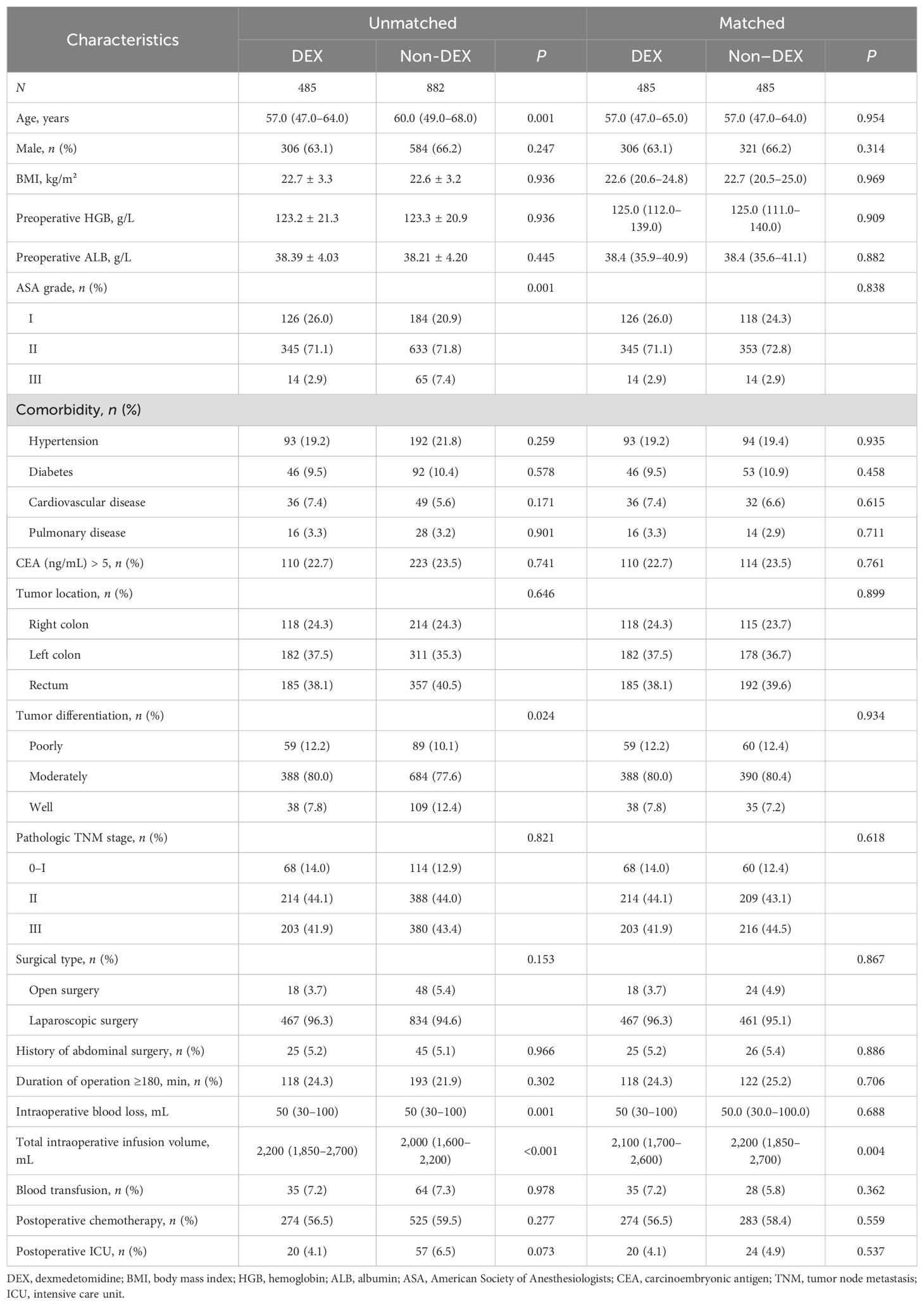

Among the 1,367 participants, 485 patients received DEX with a median intraoperative consumption of 60 μg. Patients in the DEX group were younger, had lower ASA grades and worse tumor differentiation, and received more intraoperative infusion volume than those who did not receive DEX. After propensity score matching, an imbalance remained in the intraoperative infusion volume (P = 0.004), while other covariates were balanced (Table 1).

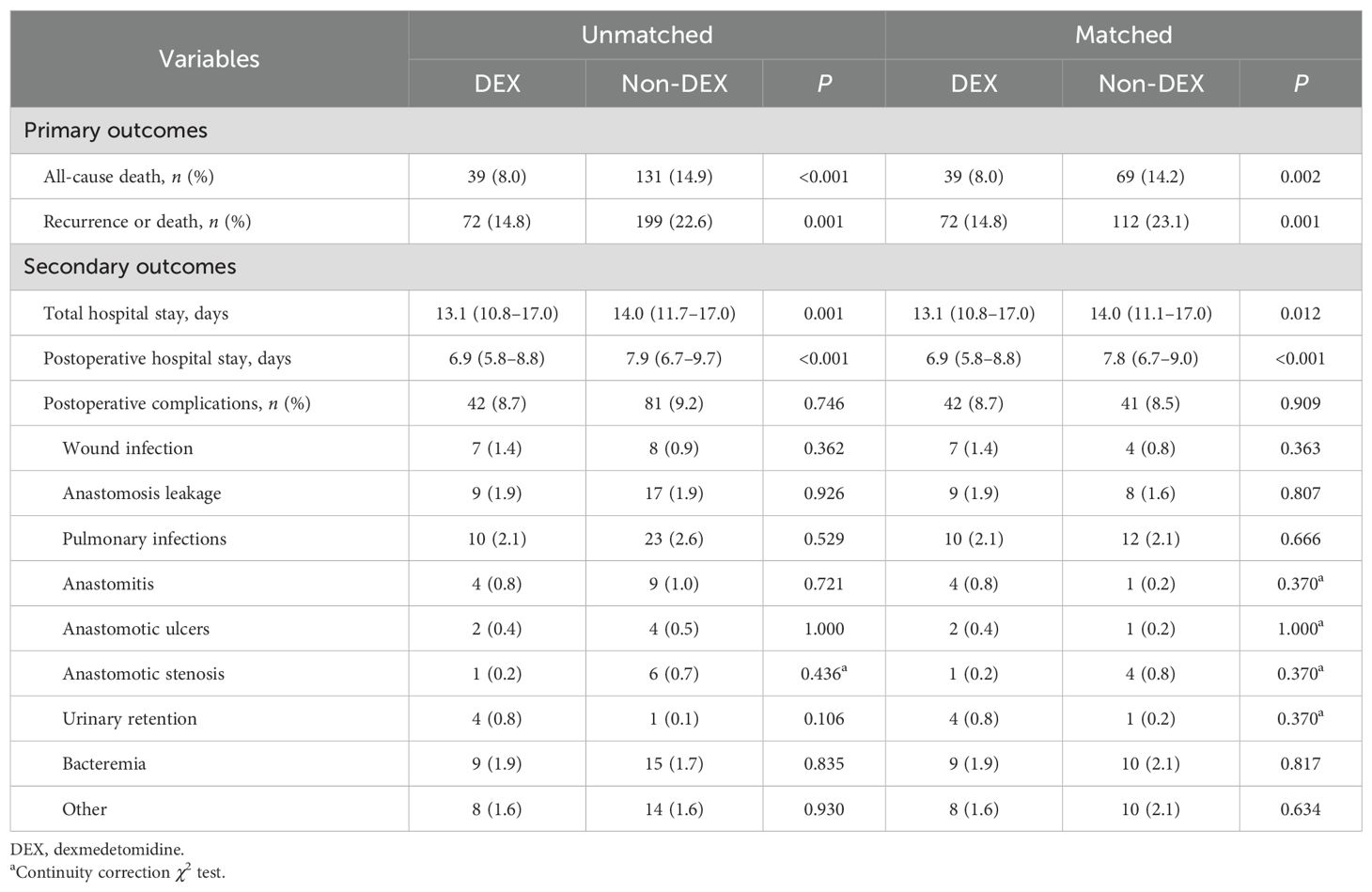

The incidence of outcomes between patients in the DEX and non-DEX groups

Overall, patients in the DEX group had significantly lower incidence rates of all-cause death (8.0% vs. 14.9%) and recurrence or death (14.8% vs. 22.6%) than the non-DEX group. The incidence rates of all-cause death (8.0% vs. 14.2%) and recurrence or death (14.8% vs. 23.1%) were also lower in the DEX group after matching. Furthermore, the total hospital stay (13.1 vs. 14.0 days) and postoperative hospital stay (6.9 vs. 7.9 days) were significantly shorter for patients who received DEX compared to those who did not, with these differences remaining significant after matching (13.1 vs. 14.0 days for total hospital stay, 6.9 vs. 7.8 days for postoperative hospital stay). No significant difference was observed in the incidence of postoperative complications (Table 2).

The associations of DEX with the main outcomes

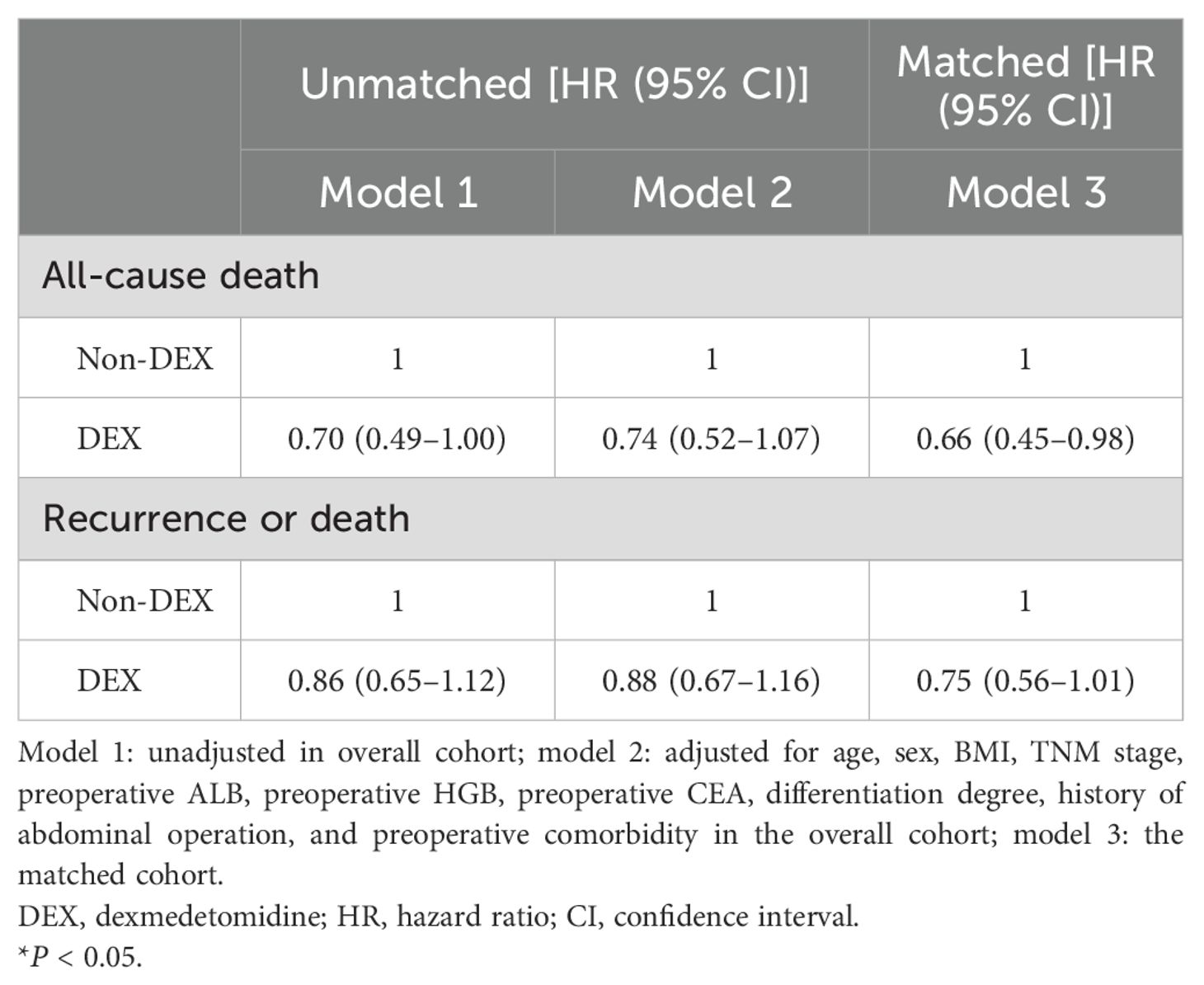

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses revealed that patients receiving DEX had a lower all-cause death risk prior to matching, although this association only reached marginal significance [adjusted HR and 95% CI: 0.74 (0.52–1.07)]. In the matched cohort, the risk of all-cause death was significantly reduced in patients who received DEX compared to those who did not receive it [adjusted HR and 95% CI: 0.66 (0.45–0.98)]. However, no significant difference was observed in the risk of recurrence or death [adjusted HR and 95% CI: 0.88 (0.67–1.16)] for the prematched cohort, while a marginal decrease in the risk of recurrence or death was observed in the matched cohort [adjusted HR and 95% CI: 0.75 (0.56–1.01)] (Table 3).

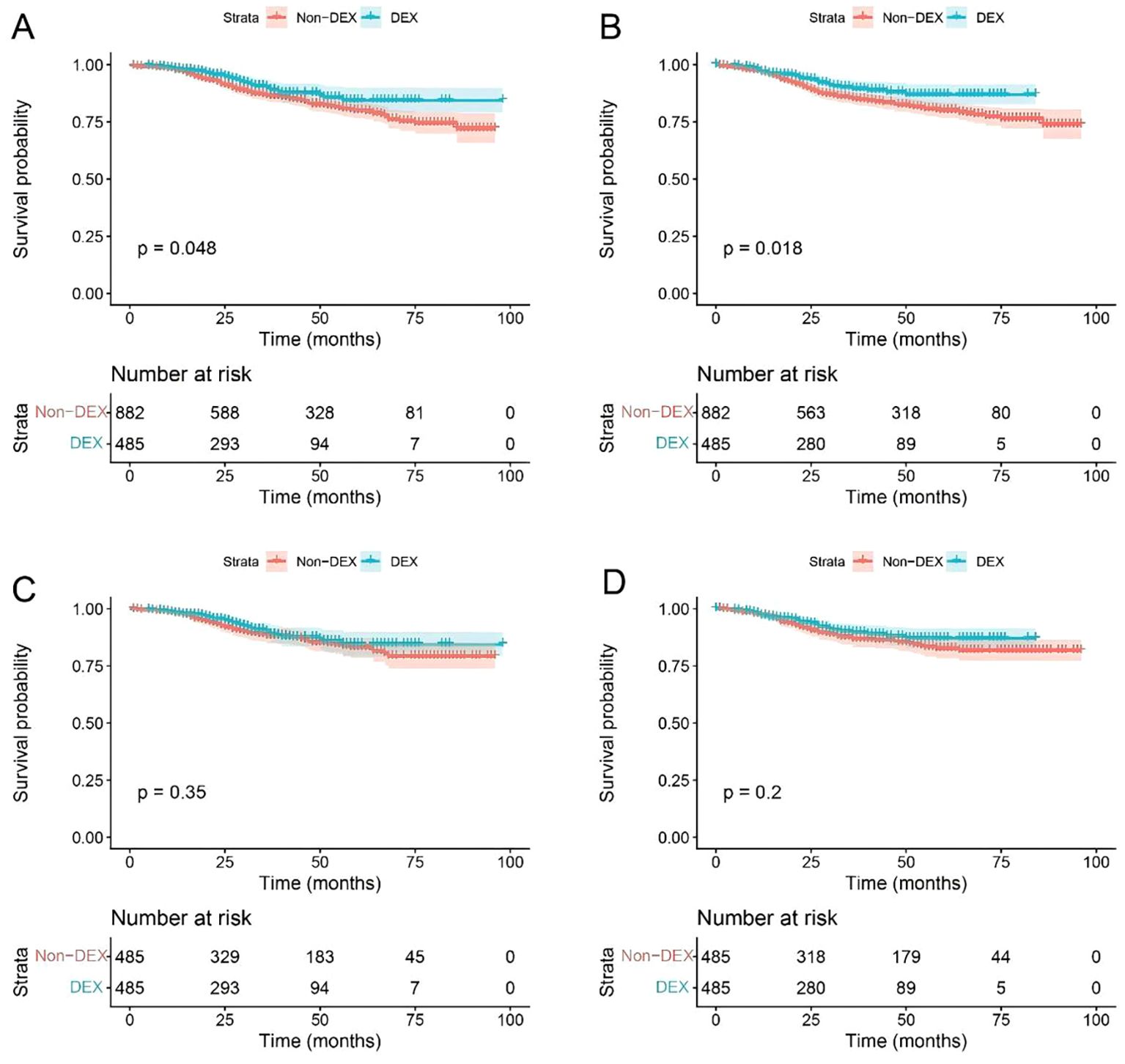

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve demonstrated a significantly higher overall survival probability for patients treated with DEX compared to those without this medication (P = 0.048 before matching, P = 0.018 after matching). However, no significant difference was found in disease-free survival probability (P = 0.350 before matching, P = 0.200 after matching) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Survival curve of the patients before and after matching. (A) Overall survival before matching; (B) overall survival after matching; (C) disease-free survival before matching; (D) disease-free survival after matching. DEX, dexmedetomidine.

We performed dose-reactive relationship analyses for DEX on the main outcomes. The results showed that there was no significant dose dependence for all-cause death and recurrence or death risks (Supplementary Table S4). In addition, subgroup analyses showed no significant interaction between DEX and subgroup factors (tumor location, tumor differentiation, pathologic TNM stage, surgical type, and any complication before the operation) (Supplementary Table S5).

The associations of DEX with secondary outcomes

In the overall cohort, linear regression models revealed a significant reduction in total hospital stay [adjusted β and 95% CI: −0.85 (−1.49, −0.22)] and postoperative hospital stay [adjusted β and 95% CI: −0.98 (−1.44, −0.52)] among patients in the DEX group. These findings remained statistically significant in the matched cohort [adjusted β and 95% CI for total hospital stay: −0.96 (−1.71, −0.22), adjusted β and 95% CI for postoperative hospital stay: −0.95 (−1.47, −0.43)]. However, no significant association was observed between DEX use in postoperative complications (Table 4).

Discussion

Our results showed that, among patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery, intraoperative use of DEX was associated with improved overall survival, but not with improved disease-free survival. Patients receiving DEX had shorter total hospital stays and postoperative hospital stays. Furthermore, intraoperative use of DEX was not related to an increased risk of postoperative complications.

The impact of DEX on cancer outcomes is a fascinating topic. Preclinical investigations reported conflicting results. On the one hand, DEX could trigger tumorigenic signaling pathways by regulating specific enzymes and apoptotic molecules, thereby promoting tumor proliferation and migration (9, 17, 18). On the other hand, DEX inhibits the growth of lung adenocarcinoma cells and induces apoptosis by upregulating the expression of miR-493-5p (12). Furthermore, DEX inhibits the growth and metastasis of esophageal carcinoma cells through upregulating miR-143-3p and reducing epidermal growth factor receptor (13). These inconsistent findings may be attributed to DEX acting on different research subjects and activating different molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways.

Clinical studies investigating the long-term effects of DEX in patients with colorectal cancer are limited. In a follow-up analysis of patients with laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer, DEX did not improve overall survival and disease-free survival but presented an increasing trend in overall survival and disease-free survival, indicating that the use of DEX may benefit the long-term prognosis of patients undergoing laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer (19). In our study, the intraoperative administration of DEX was associated with improved overall survival, but not associated with disease-free survival (only marginal significance), which is a bit different from the results of the aforementioned study. The cause of this result may be that these were two different types of studies, with different baseline characteristics of the population, confounding factors, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. It is worth noting that patients receiving DEX had higher total intraoperative infusion volume even after propensity score matching, which may be another reason for the inconsistent results. We cannot control infusion volume as a confounder, because it appeared after using DEX, which violates the concept of confounding factors. Thus, a randomized controlled trial, a more effective method, may be needed to control the influence of intraoperative factors. Nevertheless, both studies showed an upward trend in overall survival and disease-free survival rates for patients who received DEX. In addition, we also explored the dose-reactive relationship between DEX and survival. We did not find that a higher dose of DEX can acquire a better survival. Given that this is a retrospective study, the accurate dose-reactive relationship needs to be validated in a future study.

Accumulating evidence suggests that DEX could mediate direct antitumor effects through various mechanisms, such as epigenetic modifications and the induction of apoptosis and ferroptosis (12, 13, 20, 21). In addition, DEX could alleviate stress response and inflammation, reduce the level of cortisol, and regulate immune function, thus inducing indirect antitumor effects (16, 22). Therefore, DEX can inhibit tumor growth in different ways. In a murine study, DEX showed inhibition of colorectal cancer growth by modulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (23). These may indicate that intraoperative infusion of DEX may potentially inhibit tumor growth and improve clinical outcomes for colorectal cancer patients.

Our study controlled various potential confounding factors through propensity score matching, a method successfully applied in previous studies. However, this study has several limitations. First, residual confounding factors may still exist due to the retrospective property. Some covariates were difficult to collect, such as anesthetic drug dosages, depth of anesthesia, and intraoperative hemodynamic fluctuations. Second, we did not take into account the use of other anesthetics, hemodynamics, vasoactive drugs, and depth of anesthesia, resulting in failure to explain the intraoperative anesthetic-related environment. Third, retrospective studies cannot eliminate information bias, as electronic medical records may have some recording biases. Fourth, retrospective studies cannot elucidate the mechanisms that need to be explored through a basic study. Fifth, a further multicenter prospective study is necessary to validate the causal relationship.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that intraoperative infusion of DEX is associated with decreased risk of all-cause mortality in patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery. Patients who received DEX infusion exhibited shorter total hospital stays and postoperative hospital stays. These findings suggest that DEX infusion is a safe and feasible sedation scheme for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (NFEC-2020-050). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. LG: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. RZ: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. XH: Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. PL: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. JN: Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. KL: Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82072224) to Cai Li, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (grant no. 2021A1515220089) to Cai Li, Funding by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2024A04J5217) to Huamin Liu, and Bethune Charitable Foundation (bnmr-2023-001) to Huamin Liu.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1693496/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, Seufferlein T, Sung JJ, Boelens PG, et al. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2015) 1:15065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65

3. Tavare AN, Perry NJ, Benzonana LL, Takata M, and Ma D. Cancer recurrence after surgery: direct and indirect effects of anesthetic agents. Int J Cancer. (2012) 130:1237–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26448

4. Soltanizadeh S, Degett TH, and Gögenur I. Outcomes of cancer surgery after inhalational and intravenous anesthesia: A systematic review. J Clin Anesth. (2017) 42:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.08.001

5. Belleville JP, Ward DS, Bloor BC, and Maze M. Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans. I. Sedation, ventilation, and metabolic rate. Anesthesiology. (1992) 77:1125–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199212000-00013

6. Weerink MAS, Struys MMRF, Hannivoort LN, Barends CRM, Absalom AR, and Colin P. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2017) 56:893–913. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0507-7

7. Inada T, Shirane A, Hamano N, Yamada M, Kambara T, and Shingu K. Effect of subhypnotic doses of dexmedetomidine on antitumor immunity in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. (2005) 27:357–69. doi: 10.1080/08923970500240883

8. Lavon H, Matzner P, Benbenishty A, Sorski L, Rossene E, Haldar R, et al. Dexmedetomidine promotes metastasis in rodent models of breast, lung, and colon cancers. Br J Anaesth. (2018) 120:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.004

9. Chen HY, Li GH, Tan GC, Liang H, Lai XH, Huang Q, et al. Dexmedetomidine enhances hypoxia-induced cancer cell progression. Exp Ther Med. (2019) 18:4820–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8136

10. Cata JP, Singh V, Lee BM, Villarreal J, Mehran JR, Yu J, et al. Intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine is associated with decreased overall survival after lung cancer surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. (2017) 33:317–23. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_299_16

11. Tian H, Hou L, Xiong Y, Cheng Q, and Huang J. Effect of dexmedetomidine-mediated insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) signal pathway on immune function and invasion and migration of cancer cells in rats with ovarian cancer. Med Sci Monit. (2019) 25:4655–64. doi: 10.12659/MSM.915503

12. Xu B, Qian Y, Hu C, Wang Y, Gao H, and Yang J. Dexmedetomidine upregulates the expression of miR-493-5p, inhibiting growth and inducing the apoptosis of lung adenocarcinoma cells by targeting RASL11B. Biochem Cell Biol. (2021) 99:457–64. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2020-0267

13. Zhang P, He H, Bai Y, Liu W, and Huang L. Dexmedetomidine suppresses the progression of esophageal cancer via miR-143-3p/epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 axis. Anticancer Drugs. (2020) 31:693–701. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000934

14. Huang L, Qin C, Wang L, Zhang T, and Li J. Effects of dexmedetomidine on immune response in patients undergoing radical and reconstructive surgery for oral cancer. Oncol Lett. (2021) 21:106. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12367

15. Carnet Le Provost K, Kepp O, Kroemer G, and Bezu L. Trial watch: dexmedetomidine in cancer therapy. Oncoimmunology. (2024) 13:2327143. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2024.2327143

16. Wang K, Wu M, Xu J, Wu C, Zhang B, Wang G, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on perioperative stress, inflammation, and immune function: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. (2019) 123:777–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.07.027

17. Zhang F, Ding T, Yu L, Zhong Y, Dai H, and Yan M. Dexmedetomidine protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced injury through the I2 imidazoline receptor-PI3K/AKT pathway in rat C6 glioma cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. (2012) 64:120–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01382.x

18. Wang C, Datoo T, Zhao H, Wu L, Date A, Jiang C, et al. Midazolam and dexmedetomidine affect neuroglioma and lung carcinoma cell biology in vitro and in vivo. Anesthesiology. (2018) 129:1000–14. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002401

19. Hu J, Gong C, Xiao X, Chen L, Zhang Y, Li X, et al. Association between intraoperative dexmedetomidine and all-cause mortality and recurrence after laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer: Follow-up analysis of a previous randomized controlled trial. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:906514. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.906514

20. Hu Y, Qiu LL, Zhao ZF, Long YX, and Yang T. Dexmedetomidine represses proliferation and promotes apoptosis of esophageal cancer cells by regulating C-Myc gene expression via the ERK signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2021) 25:950–6. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202101_24664

21. Gao X and Wang XL. Dexmedetomidine promotes ferroptotic cell death in gastric cancer via hsa_circ_0008035/miR-302a/E2F7 axis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. (2023) 39:390–403. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12650

22. Shin S, Kim KJ, Hwang HJ, Noh S, Oh JE, and Yoo YC. Immunomodulatory effects of perioperative dexmedetomidine in ovarian cancer: an in vitro and xenograft mouse model study. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:722743. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.722743

Keywords: dexmedetomidine, colorectal cancer, postoperative outcomes, all-cause death, tumor recurrence

Citation: Chen S, Gan L, Zhang R, Huang X, Li P, Ni J, Liu K, Liu H and Li C (2025) Association between intraoperative dexmedetomidine and survival outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Oncol. 15:1693496. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1693496

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025; Revised: 11 November 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Airazat M. Kazaryan, Østfold Hospital, NorwayReviewed by:

Sergey Efetov, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, RussiaXisheng Shan, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, China

Copyright © 2025 Chen, Gan, Zhang, Huang, Li, Ni, Liu, Liu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cai Li, MTA0MTQ5ODVAcXEuY29t; Huamin Liu, bGl1aHVhbWluMTJAc211LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Shirong Chen

Shirong Chen Lu Gan†

Lu Gan† Kexuan Liu

Kexuan Liu Huamin Liu

Huamin Liu