- Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shaoxing People’s Hospital, Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China

This article presents a case study of a patient with early-stage lung cancer who received comprehensive management at our institution throughout the entire clinical course. During follow-up, multiple progressively enlarging solid nodules were detected in the right lung and pleural cavity. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) demonstrated increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in these nodules, with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 3.568. Following a multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion, surgical resection of the nodules was undertaken. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis (NSG), with special staining and microbiological testing yielding negative results, thereby excluding infectious lesions and tumor metastasis. This case highlights the critical importance of distinguishing metastatic tumors from NSG when new intrapulmonary or pleural nodules appear post-lung cancer surgery. Surgical biopsy is demonstrated to be an effective modality for achieving a definitive diagnosis.

Introduction

Liebow was the first to describe necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis (NSG), a rare idiopathic benign lung illness, in 1973. Although its exact etiology is unknown, it is thought to be related to immunological dysregulation, genetic predisposition, and infectious agents (such as fungus and atypical pathogens) (1, 2). According to epidemiological data, NSG primarily affects women between the ages of 20 and 60 (3). Sarcoid-like granulomas, vasculitis, and necrotic lesions are histopathologically indicative of NSG (4, 5). Multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules are the typical radiological manifestation, typically without hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy (3, 6). In this paper, we detail an NSG case that was preoperatively suspected to being a lung metastatic tumor. We intend to investigate the variations in imaging characteristics between NSG and pulmonary malignancies, as well as their corresponding treatment approaches, by combining clinical data, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and a study of the literature.

Case presentation

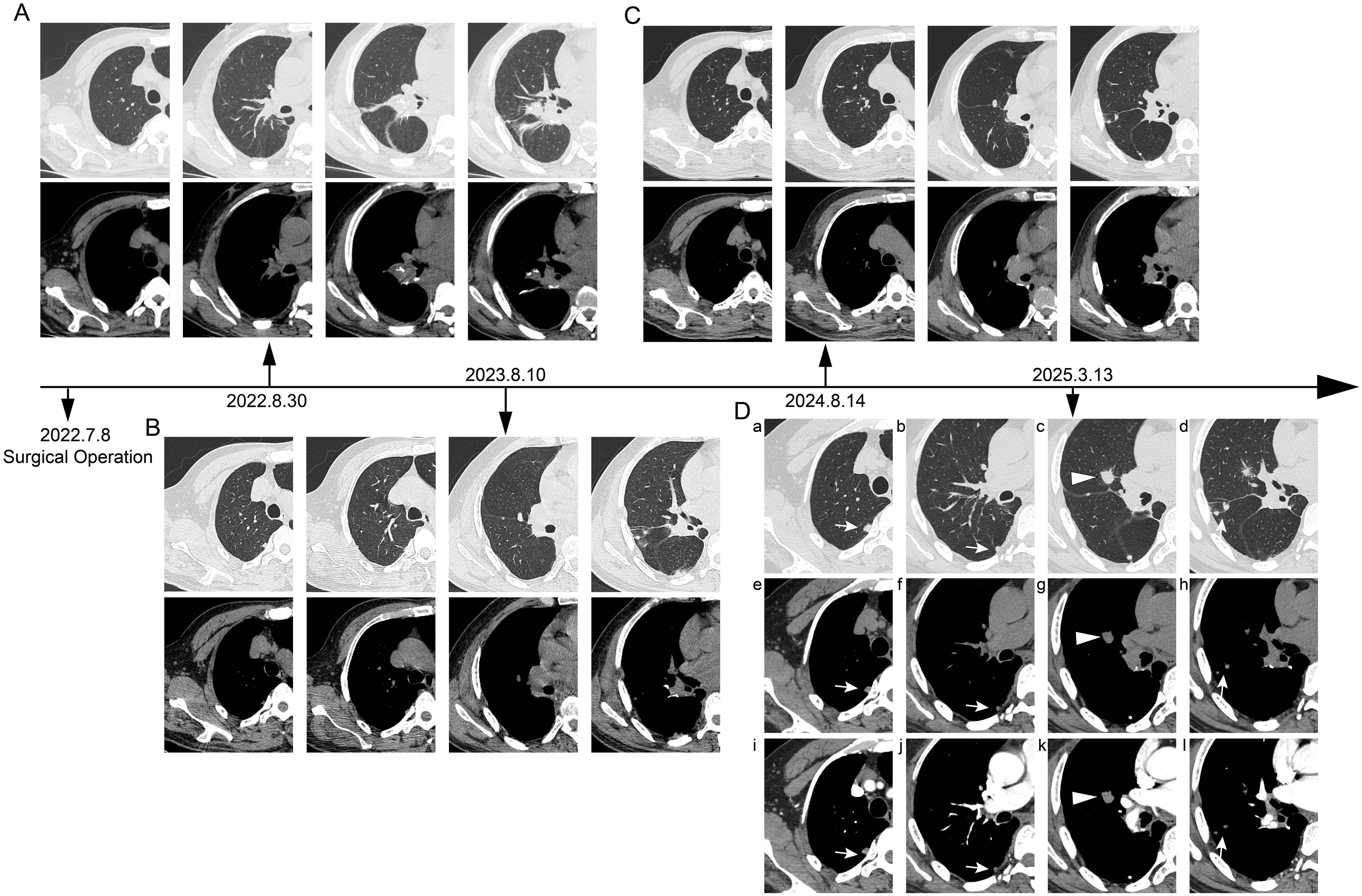

A 63-year-old male patient was admitted on March 13, 2025, with a history of right lung cancer surgery performed over 2 years ago and found to have an enlarging right pulmonary mass for over 1 year. The patient had undergone Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) right lower lobe posterior basal segmentectomy in July 2022 for a lung adenocarcinoma, staged as pT1bN0M0, stage IA2. Postoperatively, he was followed up regularly with chest computed tomography (CT) scans. On August 10, 2023, chest CT revealed a 12×6 mm solid pulmonary nodule in the lateral segment of the right middle lobe and several solid nodules in the subpleural area of the right upper lobe posterior segment and at the surgical site. Serial follow-up showed gradual enlargement. Thereafter, an annual chest CT examination was performed on the patient. (Figure 1). A CT performed one week before admission demonstrated an enlarged right middle lobe lesion measuring 16×13 mm (mean CT value –15.4 Hounsfield units (Hu)), with well-defined margins, suspicious for malignancy. Multiple solid nodules in the right upper lobe posterior subpleural region and at the surgical site were also noted to have increased in size.

Figure 1. Timeline of postoperative chest CT follow-up. (A) Postoperative day 53 (August 30, 2022): Chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed local atelectasis at the surgical site, with no new subpleural lesions observed. (B) 1 year postoperatively (August 10, 2023): Follow-up chest CT demonstrated a solid nodule (approximately 16×13 mm) in the lateral segment of the right middle lobe, along with additional subpleural solid nodules. (C) 2 years postoperatively (August 14, 2024): Follow-up chest CT showed no significant interval change in the nodule within the lateral segment of the right middle lobe or the subpleural nodules compared to the previous year. (D) Preoperative contrast-enhanced chest CT. On lung window (a-d) and mediastinal window (e-h) settings, several round nodules (open arrows and arrowheads) are observed in the subpleural region of the right upper lobe and the right middle lobe (c, g). The nodule in the right middle lobe exhibits short spiculations and pleural indentation. (i-l) The nodules in the subpleural area of the right upper lobe and the right middle lobe demonstrate contrast enhancement.

The patient denied cough, sputum, chest tightness, dyspnea, fever, night sweats, or fatigue. Physical examination was unremarkable except for a well-healed surgical scar. Laboratory findings showed elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (65.9 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (152.6 U/L), while C-reactive protein (CRP) and complete blood count were within normal limits.

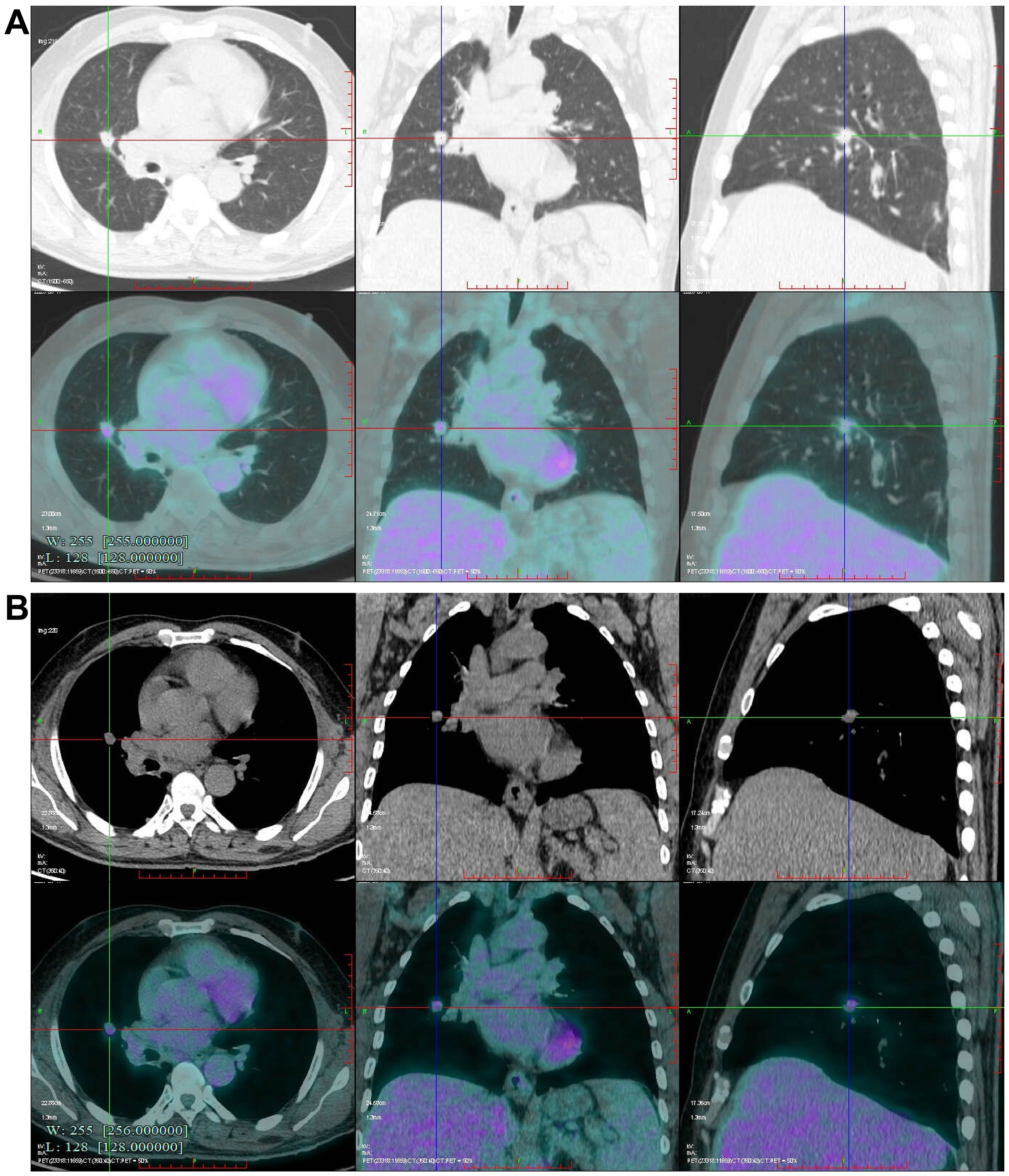

After admission, a contrast-enhanced chest CT scan revealed multiple solid nodules in the subpleural area of the right upper lobe posterior segment, the lateral segment of the right middle lobe, and the surgical field of the right lower lobe. The findings were categorized as Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) 4A. Postsurgical changes were observed in the right lower lobe, along with multiple small bilateral pulmonary nodules (Figure 1). A bone emission computed tomography (ECT) scan showed no evidence of bone metastasis. Tumor markers revealed a prostate antigen ratio of 0.189. CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and procalcitonin were within normal limits. Fungal assays, including the (1,3)-β-D-glucan (G) test, galactomannan (GM) test, cryptococcal capsular antigen, and tuberculosis (TB) infection T-cell assays, were all negative. Given the patient’s history of lung cancer, metastatic disease could not be excluded for the right lung lesion. After multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion, preoperative positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed. PET-CT demonstrated a right middle lobe nodule measuring approximately 12 × 11 × 14 mm, with partially well-defined margins and fine spiculation at the periphery. The lesion exhibited increased uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 3.568, suggestive of metastatic disease (Figure 2). Surgical treatment was therefore undertaken.

Figure 2. Preoperative Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan. (A, B) Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (standardized uptake value, SUVmax 3.568) is observed in the nodule located in the right middle lobe.

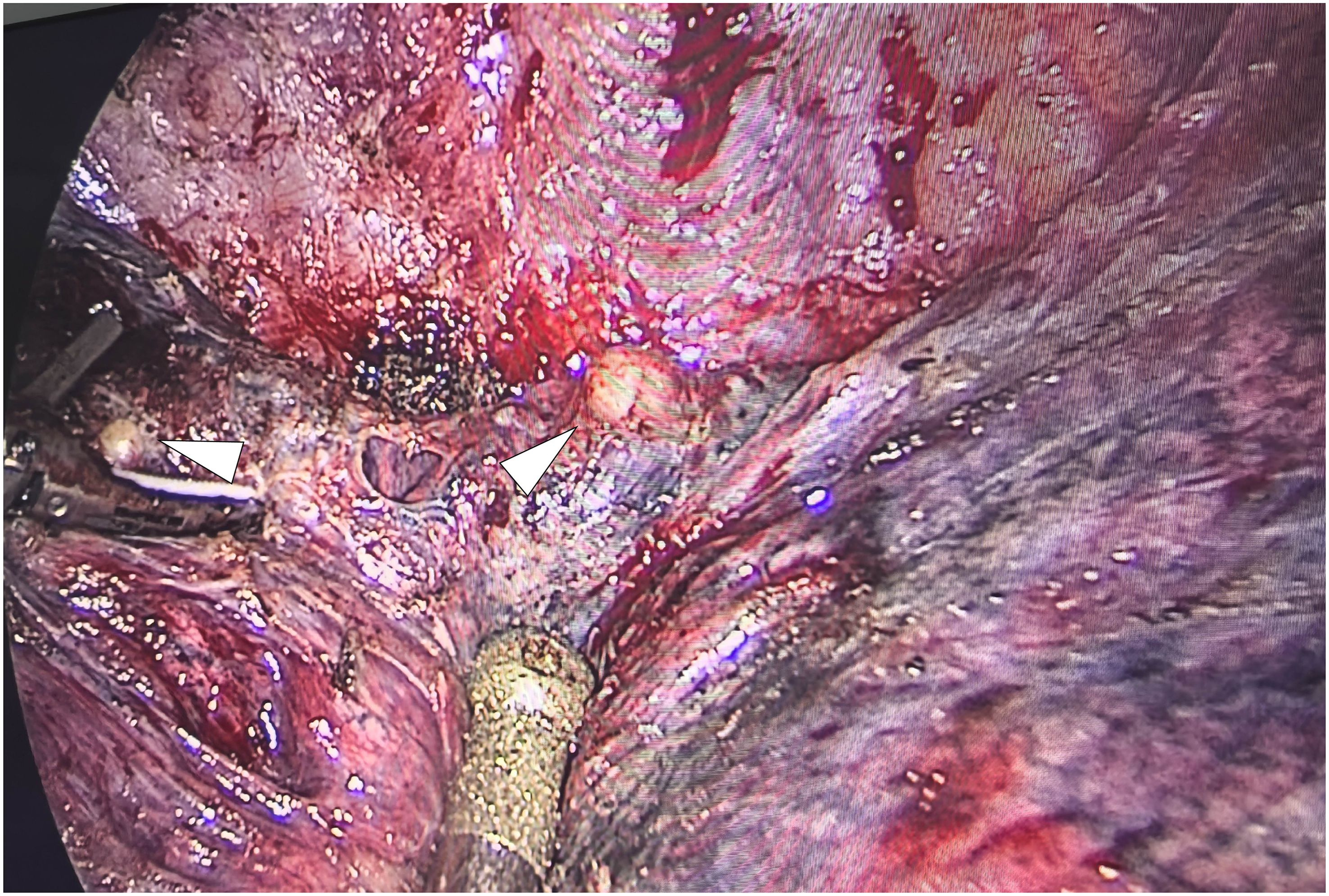

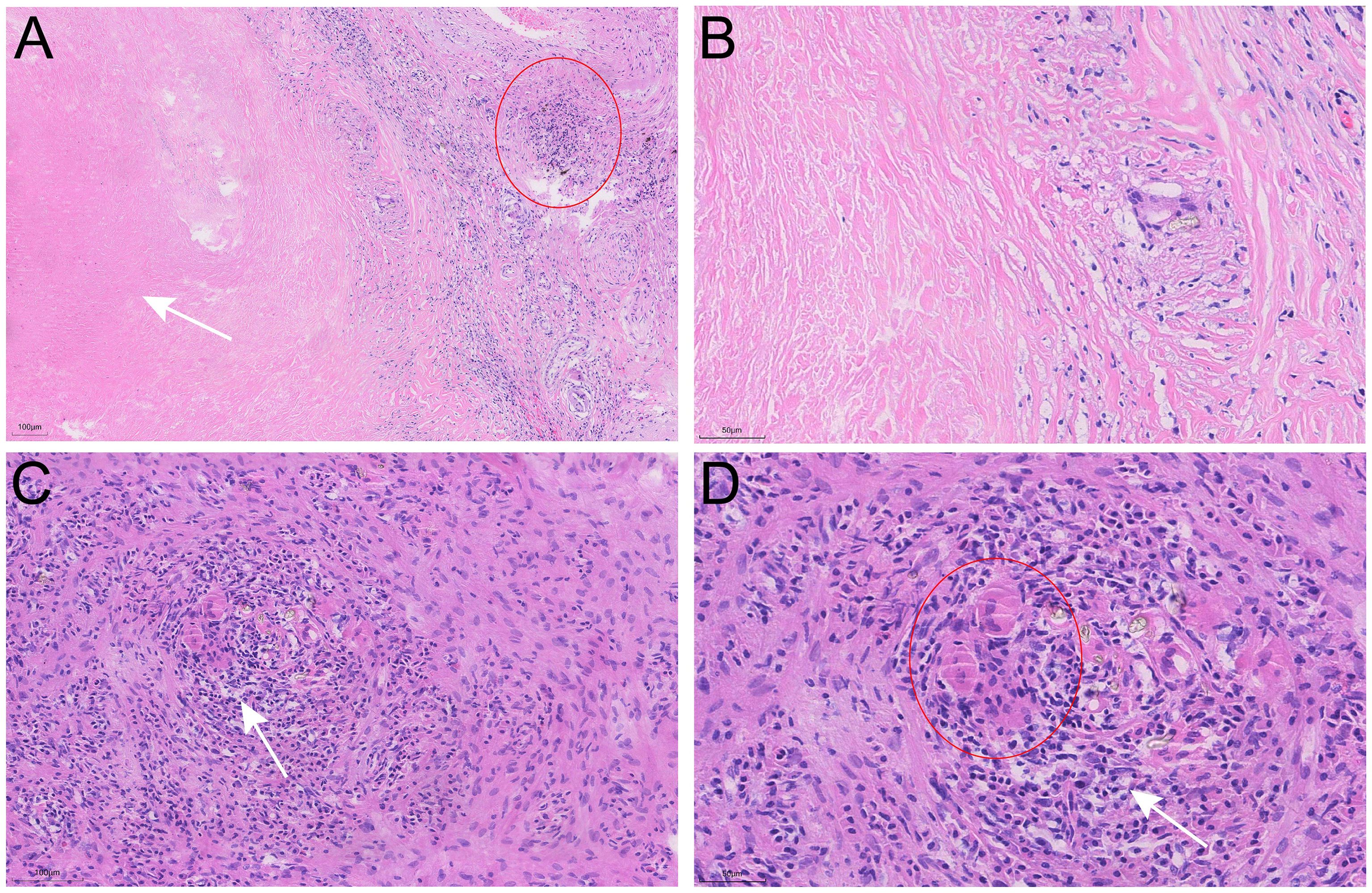

The patient underwent a VATS lung biopsy. After being found to be white in color and firm in consistency during surgery, the nodules in the right upper lobe, right middle lobe, and visceral pleura were removed for biopsy (Figure 3). Analysis of frozen sections showed widespread coagulative necrosis and granulomatous inflammation. The final histological analysis verified that the perilesional stroma had intense lymphocytic infiltration and granulomatous inflammation with widespread necrosis (Figure 4). The results of special staining, such as acid-fast staining (negative) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (negative), were all non-reactive. NSG was the diagnosis supported by the histopathological results.

Figure 3. Intraoperative endoscopic gross photograph of the nodule in the right middle lobe. The nodules appear round, pale yellow, and have well-defined margins.

Figure 4. Pathological characteristics of the nodule in the right middle lobe resected by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). (A, B) Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining reveals extensive areas of necrosis (arrows), inflammatory cell infiltration (circle), and nodular granulomas within the nodule. (C, D) Multinucleated giant cells (circle) and vasculitis with lymphocytic infiltration (arrows) are observed.

Given that the patient’s laboratory tests showed no abnormalities and all enlarged nodules had been surgically resected, the attending physician recommended continued medical observation postoperatively, with no initiation of glucocorticoid therapy.

Discussion

After sublobar resection for stage IA2 early lung cancer, multiple solid nodules in the right lung were found to be progressively enlarged during follow-up. Imaging findings and medical history highly suggest metastasis. However, the pathological findings were confirmed as necrotizing nodular granuloma. Necrotizing nodular granulomatosis is a rare benign disease of the lung that is histologically characterized by necrotizing granulomatosis with vasculitis and massive necrosis and is often clinically confused with pulmonary malignancy, attributed to its highly similar imaging features to peripheral lung cancer, and its size may grow over time, often resulting in misdiagnosis, which may lead to unnecessary systemic treatment (7–10). Similarly, case reports have documented that sarcoidosis can present as a solitary pulmonary nodule or mass, with imaging features closely resembling those of lung cancer, potentially leading to misdiagnosis and unnecessary invasive procedures or treatment (11). Thus, nodules of 8 mm or larger usually require further refinement on PET-CT scan for evaluation. Some scholars believe (12) that PET-CT can effectively distinguish between benign and malignant Solitary pulmonary nodule, and its positive results can be used as the basis for pulmonary resection surgery. However, although FDG PET may be of ancillary value in metabolically inactive lung lesions, the occurrence of false-positive results is a significant problem for granulomatous disease (6, 13). As the PET-CT scan results of this patient suggested elevated FDG uptake in multiple solid nodules in the right lung surgical area (Suvmax 3.568), combined with the history of lung cancer, lung cancer recurrence was highly suspected, so our team did a thoracoscopic lung biopsy.

Since pulmonary necrotizing nodular granuloma is highly similar to lung cancer and there are only a few articles on its radiological features, the clinical diagnosis is difficult. Recent research by Catelli et al. has shed important light on this diagnostic dilemma. Their findings elucidated that in patients with sarcoidosis, the presence of spiculation, a larger diameter, elevated CT attenuation (e.g., >60 HU), and a solitary presentation are distinct radiological characteristics significantly correlated with a higher probability of malignancy (14). A classification system has been developed by combining the clinical baseline characteristics of patients with chest thin-section computed tomography (TSCT) features, it also includes eight types with different characteristics (15). This classification scheme can provide effective guidance for clinical practice to distinguish granulomatous inflammation from lung cancer. In addition, the team retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging features of pulmonary granulomatous inflammation and lung cancer through a case-control study. Studies have found that in young patients with diabetes (≤63 years), nonenhanced CT values (≤21hu), irregularly shaped, and non-moderately enhanced SNS should first be suspected as granulomas (16). It is helpful to recognize and understand the clinical and radiological features of necrotizing nodular granulomas to guide the appropriate diagnosis, treatment and management.

Surgical biopsy is a reliable diagnostic tool for new nodules of lung cancer that can not be identified on imaging (9). And compared with other interventional methods such as puncture, surgery can simultaneously explore and biopsy multiple or even all nodules on the same side. Even if puncture is guided by CT, there is also the possibility of false negatives and the inability to deal with smaller nodules. This patient underwent a thoracoscopic procedure to explore all the nodules and obtain sufficient tissue according to the preoperative imaging guidance. Metastatic adenocarcinoma and infectious disease were excluded, unnecessary chemoradiotherapy or targeted therapy is avoided. Therefore, we believe that there is the possibility of coexistence of benign nodules and metastatic lesions of lung cancer in theory. We should try to explore and sample comprehensively during the operation to avoid missed diagnosis of metastases.

Conclusions

New intrapulmonary/pleural nodules after surgery for early stage lung cancer need to be differentiated between metastatic tumors and non-neoplastic lesions (e.g., NSG), and it is inappropriate to blindly adopt systemic therapy (chemotherapy or targeted therapy, etc.) without the basis of pathologic confirmation, and surgical biopsy is an effective means of clarifying the diagnosis and guiding the treatment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of Shaoxing People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

LD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DW: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. GY: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Liebow AA. The J. Burns Amberson lecture–pulmonary angiitis and granulomatosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. (1973) 108:1–18. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.1.1

2. Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Feigin DS, Garancis JC, and Ward PA. Necrotizing sarcoid-like granulomatosis: clinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic findings. Hum Pathol. (1980) 11:510–9.

3. Quaden C, Tillie-Leblond I, Delobbe A, Delaunois L, Verstraeten A, Demedts M, et al. Necrotising sarcoid granulomatosis: clinical, functional, endoscopical and radiographical evaluations. Eur Respir J. (2005) 26:778–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00024205

4. Schiekofer S, Zirngibl C, and Schneider JG. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis (NSG): A diagnostic pitfall to watch out for! J Clin Diagn Res. (2015) 9:OJ02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13328.6228

5. Giraudo C, Nannini N, Balestro E, Meneghin A, Lunardi F, Polverosi R, et al. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with an uncommon manifestation: clinicopathological features and review of literature. Respir Care. (2014) 59:e132–6. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02842

6. Sahin H, Ceylan N, Bayraktaroglu S, Tasbakan S, Veral A, and Savas R. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis mimicking lung Malignancy: MDCT, PET-CT and pathologic findings. Iran J Radiol. (2012) 9:37–41. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.6572

7. Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, and Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: Number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician” Edited by Peter Dorfmuller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev. (2017) 26:170012. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

8. Karpathiou G, Batistatou A, Boglou P, Stefanou D, and Froudarakis ME. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis: A distinctive form of pulmonary granulomatous disease. Clin Respir J. (2018) 12:1313–9. doi: 10.1111/crj.12673

9. Thiessen R, Seely JM, Matzinger FR, Agarwal P, Burns KL, Dennie CJ, et al. Necrotizing granuloma of the lung: imaging characteristics and imaging-guided diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2007) 189:1397–401. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2389

10. Xu DM, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Oudkerk M, Wang Y, Vliegenthart R, Scholten ET, et al. Smooth or attached solid indeterminate nodules detected at baseline CT screening in the NELSON study: cancer risk during 1 year of follow-up. Radiology. (2009) 250:264–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2493070847

11. Ballabh M, Ganesan S, Guru Prasad N, and Raghupathy T. Sarcoidosis: solitary pulmonary mass masquerading as lung cancer. Cureus. (2025) 17:e81775. doi: 10.7759/cureus.81775

12. Patz EF Jr., Lowe VJ, Hoffman JM, Paine SS, Burrowes P, Coleman RE, et al. Focal pulmonary abnormalities: evaluation with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET scanning. Radiology. (1993) 188:487–90. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.2.8327702

13. Yen RF, Chen ML, Liu FY, Ko SC, Chang YL, Chieng PU, et al. False-positive 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography studies for evaluation of focal pulmonary abnormalities. J Formos Med Assoc. (1998) 97:642–5.

14. Catelli C, Guerrini S, D’Alessandro M, Cameli P, Fabiano A, Torrigiani G, et al. Sarcoid nodule or lung cancer? A high-resolution computed tomography-based retrospective study of pulmonary nodules in patients with sarcoidosis. Diagnostics (Basel). (2024) 14:2389. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14212389

15. Xu HB, Lv FJ, Ding C, Fu BJ, Li WJ, Yu JQ, et al. Exploring and verifying key thin-section computed tomography features for accurately differentiating granulomas and peripheral lung cancers. J Thorac Dis. (2025) 17:2827–40. doi: 10.21037/jtd-24-1505

Keywords: lung cancer, necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis, metastatic tumor, multidisciplinary team, surgical biopsy

Citation: Dong L, Fu L, Wei D and Yu G (2025) Case Report: A case of necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis mimicking metastatic tumor. Front. Oncol. 15:1703599. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1703599

Received: 11 September 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Lizza E.L. Hendriks, Maastricht University Medical Centre, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Nerina Denaro, IRCCS Ca ‘Granda Foundation Maggiore Policlinico Hospital, ItalyChiara Catelli, Lung Transplant Unit, Siena University Hospital, Italy

Ismail Savas, SGS North America, United States

Copyright © 2025 Dong, Fu, Wei and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guangmao Yu, eXVndWFuZ21hb2toaUAxNjMuY29t

Lingjun Dong

Lingjun Dong Linhai Fu

Linhai Fu Guangmao Yu

Guangmao Yu