- 1Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki, Japan

- 2Department of Respiratory Medicine, Inoue Hospital, Nagasaki, Japan

- 3Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki, Japan

- 4Clinical Oncology Center, Nagasaki University Hospital, Nagasaki, Japan

- 5Clinical Research Center, Nagasaki University Hospital, Nagasaki, Japan

Background: Amivantamab, a bispecific antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, has been approved for certain types of non-small cell lung cancer; however, it is known to cause severe adverse events. The management of such adverse events is necessary for maintaining the therapeutic efficacy of amivantamab. The frequency of cardiotoxicity caused by amivantamab is low, despite its association with a high incidence of severe adverse events. Most of the adverse events are cardiovascular events caused by thrombosis. No reports of amivantamab-induced myocardial injury have been published.

Case presentation: We present the first case of drug-induced myocardial injury, detected with tachycardia but not associated with any cardiovascular events, immediately after initiating amivantamab. Echocardiography revealed a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction and global longitudinal strain, while contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed shortened T1 values, leading to a diagnosis of amivantamab-induced myocardial injury. Furthermore, with early detection and therapeutic interventions, we were able to continue treatment with amivantamab without interruption.

Conclusions: When treating patients with amivantamab, oncologists should screen for cardiac disease-related symptoms, even in the absence of elevated cardiac serum biomarkers. Furthermore, when amivantamab-induced myocardial injury is suspected, a cardiologist should be consulted promptly, as the dysfunction may be reversible.

Introduction

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that blocks the activities of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET). Amivantamab is used in combination with chemotherapy for patients with untreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring an EGFR exon 20 insertion, or for those previously treated for NSCLC with a canonical EGFR mutation who experienced EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) failure (1, 2). Amivantamab-containing regimens have proven highly efficacious; however, clinical trials have reported a high frequency (32%–52%) of adverse events associated with their use (1–3). The incidence of cardiac-related toxicity caused by amivantamab has been reported to be low. Furthermore, no cases of myocardial injury in the absence of thrombotic events have been reported to date. We present the case of a 56-year-old male patient with advanced NSCLC harboring a canonical EGFR mutation who was treated with chemotherapy in conjunction with amivantamab and developed amivantamab-induced myocardial injury in the absence of thrombotic events.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old Japanese male with no history of smoking was referred to the hospital with symptoms of exertional dyspnea. A chest X-ray revealed a right-sided pleural effusion. Aspiration revealed malignant cytology consistent with adenocarcinoma. An irregular nodule was observed in the right upper lobe of the lung on follow-up chest computed tomography (CT). Radiographic and pathologic evaluations confirmed the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, the detection of an EGFR exon 19 deletion on genetic testing led to the initiation of oral targeted therapy with osimertinib.

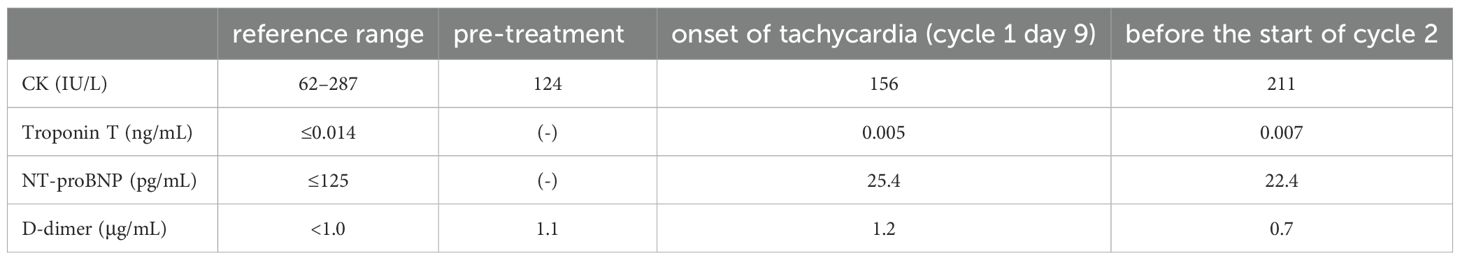

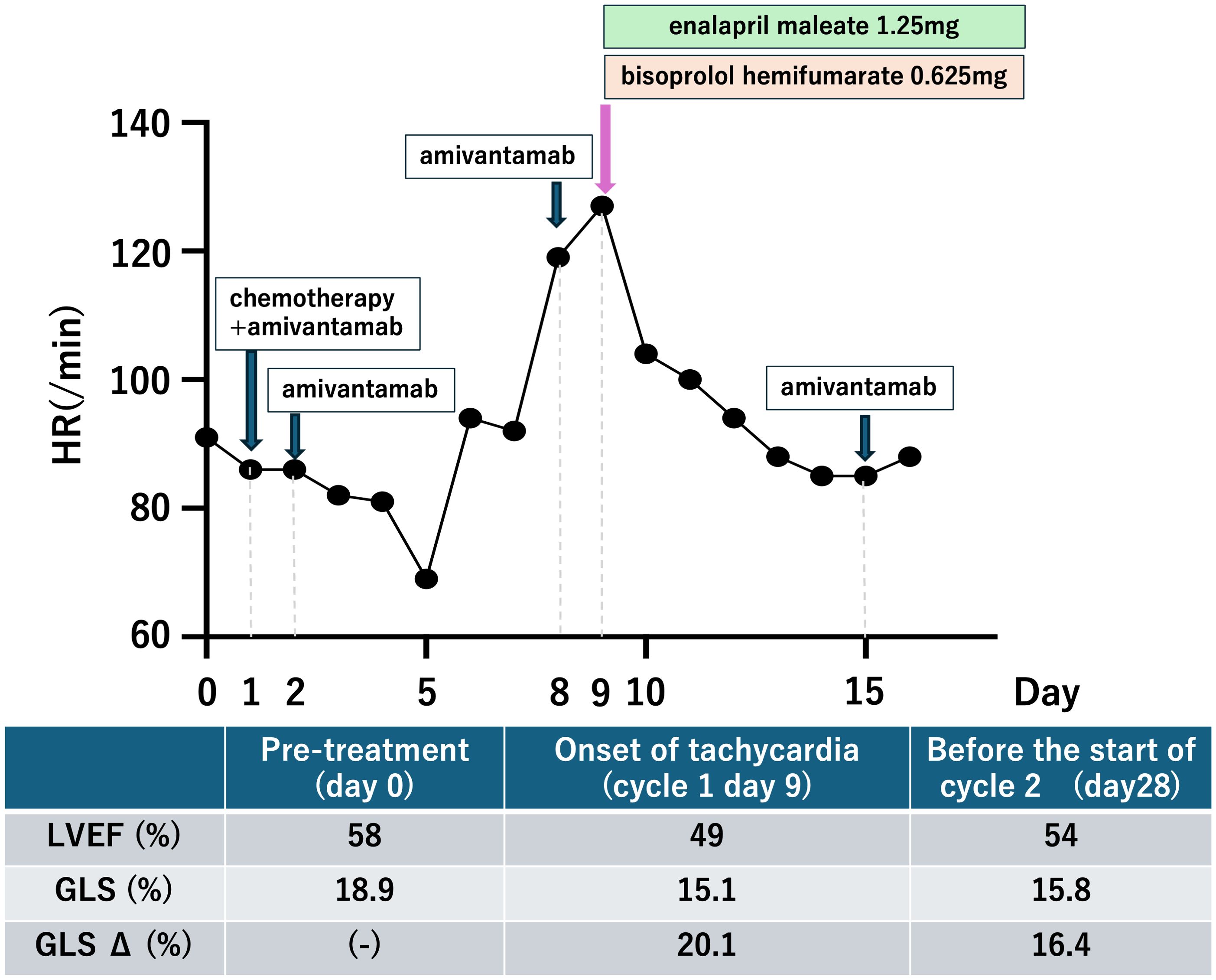

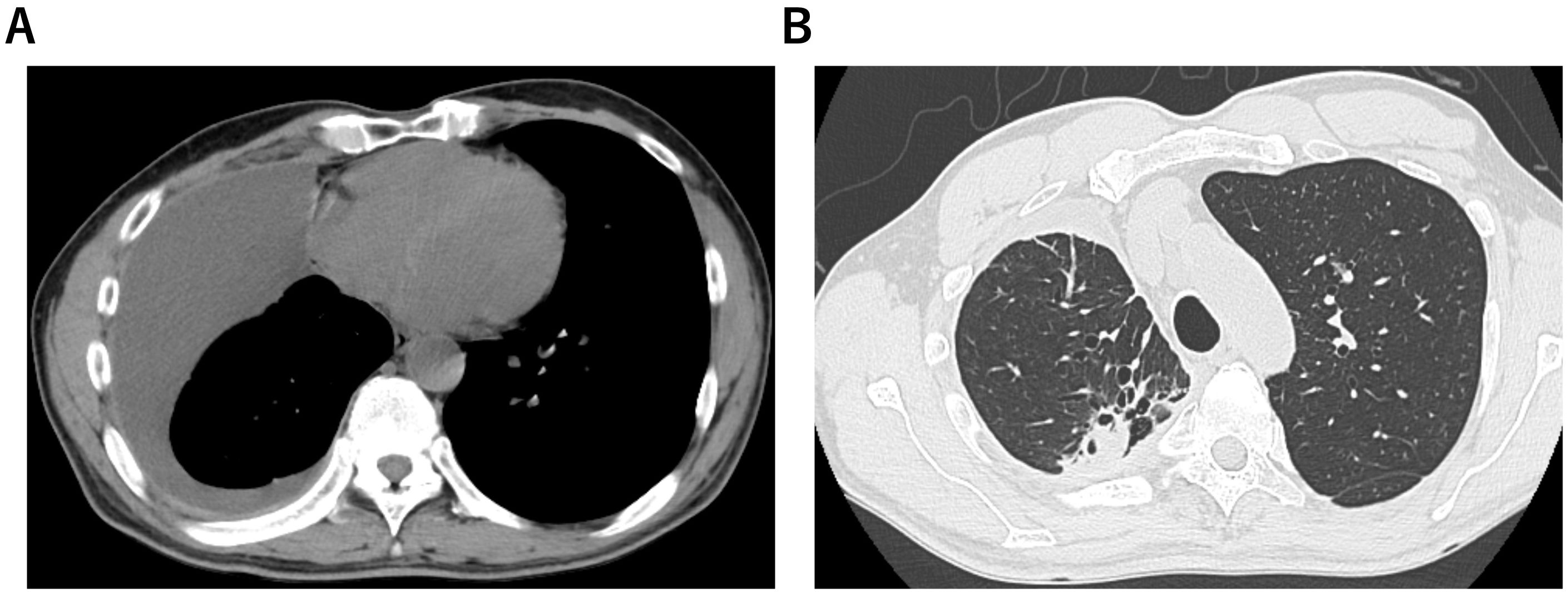

After 13 months of osimertinib treatment, the level of the carcinoembryonic antigen was slightly elevated at 8.2 ng/mL (normal range <5.0 ng/mL). A chest CT scan revealed enlargement of the right upper lobe nodule and increased right pleural effusion (Figures 1A, B). Based on these results, second-line treatment with carboplatin, pemetrexed, and amivantamab was initiated. Electrocardiogram (ECG), serum cardiac markers, and echocardiography performed before initiation of treatment all yielded normal results (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. A patient with epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated non-small cell lung carcinoma. Computed tomography scans showed right pleural effusion (A) and nodules in the right upper lobe (B) before treatment with amivantamab.

Figure 2. Comparison of 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECG) at baseline and after treatment. (A) Baseline ECG showing normal sinus rhythm (HR: 90 bpm). (B) ECG obtained 9 days after treatment commencement showing sinus tachycardia (HR: 108 bpm) without ischemic changes. Paper speed: 25mm/s.

The patient developed tachycardia 9 days following initiation of treatment, which occurred 1 day after the administration of amivantamab. ECG showed no ischemic changes, with normal sinus rhythm and sinus tachycardia at 108 bpm. Cardiac and coagulation markers, including myocardium markers, showed no elevation (Table 1). However, echocardiography revealed a mild reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a significant reduction in global longitudinal strain (GLS) (Figure 3). Furthermore, contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed no apparent left ventricular wall thickening or wall motion abnormalities. Although there was no clear elevation of native T1 values or late gadolinium enhancement (Figures 4A, B), a shorted T1 signal on contrast imaging was observed, indicative of drug-induced myocardial injury (Figure 4C). Additionally, no evidence of myocardial edema was detected on T2 mapping or T2-weighted imaging (Figure 4D). Finally, contrast-enhanced cardiac CT showed no evidence of coronary artery disease (Figures 4E, F).

Figure 4. Detection of myocardial injury using cardiac imaging. (A) T1 mapping showed no clear elevation of native T1 values. (B) Delayed enhancement imaging revealed no areas of hyperenhancement. (C) Contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed areas of T1 shortening in the myocardium, indicative of drug-induced myocardial injury. (D) T2 mapping showed no evidence of myocardial edema. (E, F) No significant stenosis of the coronary arteries was observed on contrast-enhanced cardiac computed tomography.

Following immediate consultation with cardiologists, the patient was treated with enalapril maleate 1.25 mg and bisoprolol hemifumarate 0.625 mg. The patient’s condition improved, and a follow-up echocardiogram was conducted 28 days after treatment initiation (i.e., 19 days after the event onset). LVEF had nearly returned to its baseline value, but GLS only showed a slight improvement, remaining slightly lower than the baseline value. The patient is currently receiving treatment with amivantamab under close cardiology follow-up.

Discussion

In cancer therapy, cancer treatment-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) is a potentially life-threatening adverse event. CTRCD refers to new-onset cardiac dysfunction or worsening of pre-existing dysfunction due to cancer treatment, assessed by measuring LVEF and GLS on echocardiography (4). In this case, the rapid decline in LVEF and GLS after amivantamab administration, along with exclusion of other potential causes, confirmed amivantamab-induced CTRCD. One of the main limitations of this case study lies in the fast that carboplatin and pemetrexed might have contributed to the development of myocardial injury. However, these agents rarely lead to such an outcome. For example, Quan et al. reported a case in which myocardial injury occurred in the ultra-acute phase following combination therapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed (5). In our case, carboplatin and pemetrexed were administered only on day 1, whereas amivantamab was the sole agent administered on the day prior to the onset of myocardial injury. Considering this temporal relationship, amivantamab suggestively may have played a causative role in inducing the myocardial injury. GLS, troponin T, and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are considered useful indicators for the early detection of CTRCD (6–8); Although only GLS decreased in the present case, the sensitivity of troponin for detecting CTRCD has been reported to be 0.78 (9), and CTRCD induced by molecular targeted agents has been linked to functional or metabolic alterations rather than direct myocardial necrosis (10). Furthermore, the absense of correlation between NT-proBNP elevation and left ventricular dysfunction has also been reported (11). These findings suggest that negative results for troponin and NT-proBNP do not necessarily exclude the presence of CTRCD, highlighting the importance of comprehensive assessment that incorporated imaging-related findings. And post-contrast T1 shortening on cardiac MRI constituted the main imaging finding. Post-contrast T1 shortening and increased extracellular volume fraction on cardiac MRI have been reported to indicate interstitial expansion even in patients without left ventricular hypertrophy (12). These findings suggest that myocardial injury and remodeling may occur prior to overt hypertrophy or late gadolinium enhancement, and this has been reported as an imaging feature that supports the diagnosis of drug-induced myocardial injury (12). Regarding treatment, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers have been reported to be effective for CTRCD, and early intervention may allow continuation of cancer therapy (6, 13, 14).

Several studies have reported that trastuzumab, an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) agent, is a representative molecularly targeted therapy that can cause CTRCD (15–17). Reports have also indicated that early intervention for treating CTRCD caused by trastuzumab enables continuation of treatment (18, 19). HER2 and EGFR belong to the same erythroblastosis group B receptor family and have closely related functions (20). Furthermore, their kinase domains share approximately 83% sequence identity (21). Compared with first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs, osimertinib is more likely to cause a decrease in LVEF (22). Although inhibition of HER2 by osimertinib has been suggested as a possible mechanism, its inhibitory activity is reported to be 6–12 times lower than that of other HER2 inhibitors such as lapatinib or afatinib, and therefore, the involvement of HER2 in this mechanism remains unclear (23). Report suggests that one possible contributing factor is the exacerbation of endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by osimertinib, which is closely associated with the onset and progression of heart failure (24). In addition to kinase inhibition, amivantamab reportedly exerts antitumor effects through Fc-mediated immune mechanisms, including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (25–27). These effects involve the recruitment and activation of natural killer cells and macrophages, leading to direct tumor cell killing and modulation of the tumor microenvironment (28). Although such Fc-mediated effects have not been established for small molecule EGFR-TKIs, these findings show that the biological impact of EGFR/HER2 inhibition extends beyond kinase suppression and may involve complex immunogenic crosstalk. Given that immune activation and cytokine release can influence cardiomyocyte stress pays, Fc-dependent immune mechanisms may represent an additional factor linking EGFR/HER2-targeted therapy to CTRCD development. Taken together, these findings indicate that agents inhibiting EGFR or HER2 require careful monitoring for the development of CTRCD as highlighted in a review of cardio-oncology surveillance for targeted therapies, including the 2022 ESC Cardio-Oncology Guidelines (29).

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of amivantamab-induced myocardial injury without thrombotic events. Furthermore, it is critically important to promptly consult with cardiologists if CTRCD is suspected, even in the absence of elevated cardiac serum biomarkers, to allow continuation of amivantamab-containing treatments for better outcomes, as this CTRCD may be reversible.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagasaki University Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

SK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. YD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TI: Writing – review & editing. TFM: Writing – review & editing. TY: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. TM: Writing – review & editing. NH: Writing – review & editing. KA: Writing – review & editing. HT: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. HT: Writing – review & editing. ST: Writing – review & editing. HM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1708575/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Video 1 | Baseline echocardiographic findings showing normal left ventricular contraction.

Supplementary Video 2 | Echocardiographic findings at the onset of myocardial injury demonstrating reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and wall-motion abnormalities.

Supplementary Video 3 | Speckle-tracking echocardiographic analysis from standard apical (A) 4-, (B) 2-, (C) 3-chamber views showing the shortening of global longitudinal strain at the onset of myocardial injury.

Abbreviations

EGFR, Epidermal growth factor receptor; MET, Mesenchymal-epithelial transition; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; TKI, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CT, computed tomography; ECG, Electrocardiogram; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; GLS, Global longitudinal strain; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; CTRCD, cancer treatment-related cardiac dysfunction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; HER2, Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

References

1. Passaro A, Wang J, Wang Y, Lee SH, Melosky B, Shih JY, et al. Amivantamab plus chemotherapy with and without lazertinib in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC after disease progression on osimertinib: primary results from the phase III MARIPOSA-2 study. Ann Oncol. (2024) 35:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.117

2. Zhou C, Tang KJ, Cho BC, Liu B, Paz-Ares L, Cheng S, et al. Amivantamab plus Chemotherapy in NSCLC with. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:2039–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2306441

3. Cho BC, Lu S, Felip E, Spira AI, Girard N, Lee JS, et al. Amivantamab plus lazertinib in previously untreated. N Engl J Med. (2024) 391:1486–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2403614

4. Delgado V, Marsan NA, de Waha S, Bonaros N, Brida M, and Burri H. Correction to: 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis: Developed by the task force on the management of endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:4780. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad625

5. Quan X, Zhang H, Xu W, Cui M, and Guo Q. Sinus arrhythmia caused by pemetrexed with carboplatin combination: A case report. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e11006. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11006

6. Thavendiranathan P, Negishi T, Somerset E, Negishi K, Penicka M, Lemieux J, et al. Strain-guided management of potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.020

7. Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F, Lim KD, Plana JC, Woo A, and Marwick TH. Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 63:2751–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.073

8. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Civelli M, De Giacomi G, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2010) 55:213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.095

9. Lv X, Pan C, Guo H, Chang J, Gao X, Wu X, et al. Early diagnostic value of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T for cancer treatment-related cardiac dysfunction: a meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. (2023) 10:2170–82. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14373

10. Kubota S, Hara H, and Hiroi Y. Current status and future perspectives of onco-cardiology: Importance of early detection and intervention for cardiotoxicity, and cardiovascular complication of novel cancer treatment. Glob Health Med. (2021) 3:214–25. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2021.01024

11. Michel L, Mincu RI, Mahabadi AA, Settelmeier S, Al-Rashid F, Rassaf T, et al. Troponins and brain natriuretic peptides for the prediction of cardiotoxicity in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:350–61. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1631

12. Ho CY, Abbasi SA, Neilan TG, Shah RV, Chen Y, Heydari B, et al. T1 measurements identify extracellular volume expansion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sarcomere mutation carriers with and without left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2013) 6:415–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000333

13. Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, Domenech A, Ortiz-Perez JT, de Caralt TM, et al. Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with Malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (preventiOn of left Ventricular dysfunction with Enalapril and caRvedilol in patients submitted to intensive ChemOtherapy for the treatment of Malignant hEmopathies). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 61:2355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.072

14. Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley MR, das Dores Cruz F, Goncalves Brandao SM, Rigaud VOC, et al. Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity: the CECCY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 71:2281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.049

15. Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. (2001) 344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101

16. Costa RB, Kurra G, Greenberg L, and Geyer CE. Efficacy and cardiac safety of adjuvant trastuzumab-based chemotherapy regimens for HER2-positive early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. (2010) 21:2153–60. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq096

17. Chen J, Long JB, Hurria A, Owusu C, Steingart RM, and Gross CP. Incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 60:2504–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.068

18. Lynce F, Barac A, Geng X, Dang C, Yu AF, Smith KL, et al. Prospective evaluation of the cardiac safety of HER2-targeted therapies in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and compromised heart function: the SAFE-HEaRt study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2019) 17:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05191-2

19. Pituskin E, Mackey JR, Koshman S, Jassal D, Pitz M, Haykowsky MJ, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to novel therapies in cardio-oncology research (MANTICORE 101-Breast): a randomized trial for the prevention of trastuzumab-associated cardiotoxicity. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:870–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.7830

20. Dietel E, Brobeil A, Tag C, Gattenloehner S, and Wimmer M. Effectiveness of EGFR/HER2-targeted drugs is influenced by the downstream interaction shifts of PTPIP51 in HER2-amplified breast cancer cells. Oncogenesis. (2018) 7:64. doi: 10.1038/s41389-018-0075-1

21. Telesco SE and Radhakrishnan R. Atomistic insights into regulatory mechanisms of the HER2 tyrosine kinase domain: a molecular dynamics study. Biophys J. (2009) 96:2321–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3912

22. Waliany S, Caswell-Jin J, Riaz F, Myall N, Zhu H, Witteles RM, et al. Pharmacovigilance analysis of heart failure associated with anti-HER2 monotherapies and combination regimens for cancer. JACC CardioOncol. (2023) 5:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2022.09.007

23. Ewer MS and Lippman SM. Type II chemotherapy-related cardiac dysfunction: time to recognize a new entity. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:2900–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.827

24. Okada K, Minamino T, Tsukamoto Y, Liao Y, Tsukamoto O, Takashima S, et al. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing heart after aortic constriction: possible contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation. (2004) 110:705–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137836.95625.D4

25. Vijayaraghavan S, Lipfert L, Chevalier K, Bushey BS, Henley B, Lenhart R, et al. Amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an fc enhanced EGFR/cMet bispecific antibody, induces receptor downmodulation and antitumor activity by monocyte/macrophage trogocytosis. Mol Cancer Ther. (2020) 19:2044–56. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-20-0071

26. Neijssen J, Cardoso RMF, Chevalier KM, Wiegman L, Valerius T, Anderson GM, et al. Discovery of amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), a bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and MET. J Biol Chem. (2021) 296:100641. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100641

27. Rivera-Soto R, Henley B, Pulgar MA, Lehman SL, Gupta H, Perez-Vale KZ, et al. Amivantamab efficacy in wild-type EGFR NSCLC tumors correlates with levels of ligand expression. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2024) 8:192. doi: 10.1038/s41698-024-00682-y

28. Cho BC, Simi A, Sabari J, Vijayaraghavan S, Moores S, and Spira A. Amivantamab, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET) bispecific antibody, designed to enable multiple mechanisms of action and broad clinical applications. Clin Lung Cancer. (2023) 24:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2022.11.004

29. Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, Asteggiano R, Aznar MC, Bergler-Klein J, et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:4229–361. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, mesenchymal-epithelial transition, lung cancer, amivantamab, myocardial injury, case report

Citation: Kaneko S, Dotsu Y, Inoue T, Motokawa T, Yoshimuta T, Mori M, Morikawa T, Honda N, Akagi K, Tomono H, Matsuo M, Taniguchi H, Takemoto S and Mukae H (2025) Acute amivantamab-induced myocardial injury in a patient with epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung cancer: a first case report. Front. Oncol. 15:1708575. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1708575

Received: 03 October 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

George Latsios, Hippokration General Hospital, GreeceReviewed by:

Aimilia Lazarou, Hippokration General Hospital, GreeceDorothea Tsekoura, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Copyright © 2025 Kaneko, Dotsu, Inoue, Motokawa, Yoshimuta, Mori, Morikawa, Honda, Akagi, Tomono, Matsuo, Taniguchi, Takemoto and Mukae. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yosuke Dotsu, eW9zdWtlLmRvdHN1QG5hZ2FzYWtpLXUuYWMuanA=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Seiya Kaneko

Seiya Kaneko Yosuke Dotsu

Yosuke Dotsu Tomoaki Inoue2

Tomoaki Inoue2 Kazumasa Akagi

Kazumasa Akagi Hirokazu Taniguchi

Hirokazu Taniguchi