- 1Translational-Transdisciplinary Research Center, Medical Science Research Institute, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2Department of Medicine, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 3Department of Biomedical & Robotics Engineering, College of Engineering, Incheon National University, Incheon, Republic of Korea

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Background: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains highly lethal with five-year survival below 10%, primarily due to late diagnosis, treatment resistance, and immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Methods: This review examines recent advances in PDAC precision medicine by analyzing organoid-based drug screening platforms, mRNA immunotherapy developments, and integrated diagnostic technologies.

Results: Patient-derived organoids demonstrate strong predictive value for clinical outcomes, with drug sensitivity profiles correlating with patient responses (concordance >80%). Personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccines induce robust T-cell responses, with vaccine responders showing significantly prolonged recurrence-free survival (median not reached vs. 13.4 months). KRAS-targeted therapies achieve 10-15% response rates in G12C-mutant PDAC. Integration of spatial transcriptomics and liquid biopsy enables real-time molecular monitoring.

Conclusions: The development of patient-derived organoids for drug sensitivity testing, personalized mRNA vaccines for immune activation, and precision diagnostic and therapeutic technologies represents complementary advances in PDAC. While each approach has demonstrated independent clinical value, their integration remains an important future direction that may provide a comprehensive framework for improving outcomes in PDAC.

1 Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most formidable challenges in modern oncology, with approximately 60,430 new diagnoses expected annually in the United States and a rapidly increasing global incidence (1). Despite intensive research efforts, the five-year survival rate has remained below 10% for decades, and PDAC is projected to become the second most common cause of cancer mortality by 2030 (2). This poor prognosis reflects unique biological characteristics that distinguish PDAC from other solid malignancies and profound limitations of current therapeutic approaches.

The challenges inherent in PDAC treatment stem from multiple interconnected factors creating a highly challenging therapeutic environment. Most patients present with advanced, unresectable disease due to early metastatic spread and absence of reliable screening methods (3). The biological complexity of PDAC creates formidable therapeutic barriers through its dense stromal architecture, immunosuppressive environment, and nearly universal KRAS mutations that collectively generate a treatment-resistant phenotype (4, 5). Despite significant technological advances, therapeutic progress has been constrained by fragmented approaches that address individual biological barriers in isolation and fail to account for the considerable adaptability and heterogeneity of this malignancy (6).

Recent technological advances have generated multiple complementary approaches for transforming PDAC management. The development of organoid culture systems enable high-throughput drug screening (7, 8). Patient-derived organoids have demonstrated strong predictive value for clinical outcomes, with drug sensitivity profiles correlating closely with patient treatment responses (9, 10). In parallel, personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccines show meaningful clinical benefits in early-phase clinical studies (11, 12). Advanced technologies including single cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and proteomics provide insights into tumor heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms (13, 14). This review examines these complementary advances in PDAC, whose long-term progression may provide a novel framework that may transform PDAC from an invariably fatal malignancy to a potentially manageable chronic disease.

2 Current clinical landscape: standard-of-care and precision therapies

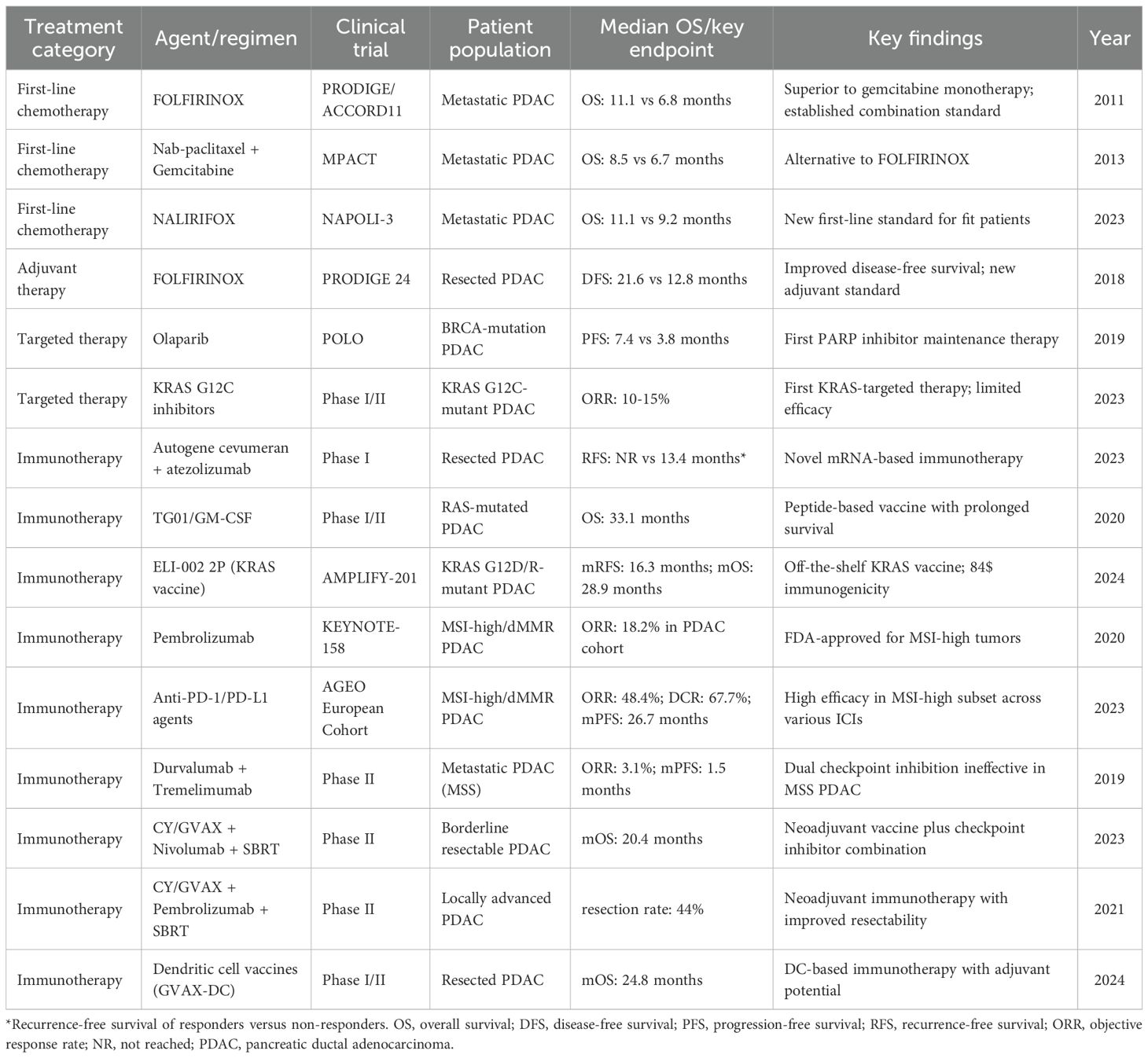

The therapeutic landscape for PDAC has evolved significantly through landmark clinical trials. The FOLFIRINOX regimen demonstrated superior overall survival compared with gemcitabine monotherapy (11.1 vs. 6.8 months), establishing combination chemotherapy as the foundation for treating metastatic PDAC in fit patients (15). Subsequently, nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine showed improved overall survival (8.5 vs. 6.7 months), providing an alternative regimen (16). The recent NAPOLI-3 trial demonstrated the superiority of NALIRIFOX over nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, establishing a new benchmark for first-line treatment with median overall survival of 11.1 months versus 9.2 months (17).

FOLFIRINOX has also shown significant benefits in the adjuvant setting. The PRODIGE 24 trial demonstrated that adjuvant FOLFIRINOX improved disease-free survival compared with gemcitabine (21.6 vs. 12.8 months) in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (18). The treatment paradigm for localized PDAC has shifted significantly toward neoadjuvant therapy for borderline resectable and locally advanced disease, with recent randomized trials demonstrating improved resection quality and compliance (19).

Significant strides have been made in precision medicine. For patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations, the PARP inhibitor olaparib improves progression-free survival (7.4 vs. 3.8 months) (20). Recent FDA approvals have expanded targeted therapy options including KRAS G12C inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib, which have shown response rates of 10-15% in patients with KRAS G12C-mutant PDAC (21). Table 1 summarizes these pivotal clinical trials that have shaped the current therapeutic landscape. These successes underscore the importance of genomic profiling in guiding treatment and highlight the emerging role of personalized approaches in PDAC management.

Immunotherapy represents an emerging treatment modality in PDAC despite the traditionally immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. KRAS targeted peptide vaccines, including TG01/GM-CSF and ELI-002 2P, have demonstrated encouraging survival and immunogenicity outcomes (22, 23). Neoadjuvant combinations of allogenic tumor vaccines with checkpoint inhibitors and radiotherapy have improved resectability in advanced disease (24, 25). For patients with microsatellite instability-high tumors (1-2% of PDAC), pembrolizumab has achieved FDA approval (26, 27). In contrast, dual checkpoint inhibition proved ineffective in microsatellite-stable (MSS) PDAC, which comprise the majority of cases, underscoring the profound immunosuppressive nature of the PDAC microenvironment (28). Although these approaches remain investigational, they represent important therapeutic developments summarized in Table 1 and discussed in detail in Section 5.2.

3 Biological foundations of PDAC resistance

3.1 Intratumor heterogeneity and multi-layered resistance

PDAC exhibits significant cellular diversity within individual tumors, posing major challenges to treatment efficacy (6). Intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) encompasses genetic and metabolic variations that enable tumor evolution and adaptation (29, 30). This heterogeneity is actively maintained through crosstalk between tumor cells and the stromal microenvironment (31), creating distinct cellular subpopulations with varying sensitivities to therapeutic agents that serve as reservoirs for chemoresistance (32).

Therapeutic resistance arises through multiple interconnected mechanisms operating across different temporal and spatial scales (33). Genetic evolution drives the emergence of resistant tumor clones through acquisition of mutations in drug targets and bypass pathways, whereas epigenetic reprogramming enhances cellular plasticity and adaptability (32). Concurrently, microenvironmental adaptations mediated by stromal-immune interactions create physical and biological barriers to therapy (4, 34). Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) contribute significantly to chemoresistance by secreting exosome-derived mi croRNAs that reprogram tumor cell metabolism. CAF-derived miR-3173-5p specifically targets ACSL4 to suppress ferroptosis and confer gemcitabine resistance (35). PDAC cells employ autophagy-dependent mechanisms to evade immune surveillance by selectively degrading MHC-I molecules, effectively rendering tumor cells invisible to CD8+ T cells (36). These stromal interactions are further reinforced by ERK-dependent transcriptional landscapes that drive PDAC growth and therapeutic resistance (37).

Rather than pursuing traditional maximum tolerated dose approaches that may select for resistant clones, recent evidence suggests that constraining cellular heterogeneity through combination approaches represents a more viable strategy for halting PDAC progression (6). The goal shifts from eliminating all tumor cells to constraining their evolutionary potential and rendering them vulnerable to conventional therapies (38).

3.2 Immunosuppressive microenvironment

The PDAC microenvironment is characterized by multiple immunosuppressive cell populations that collectively create a hostile environment for antitumor immunity (4). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) constitute a key element, facilitating PDAC progression and inhibiting effective antitumor immunity (39). These cells mediate resistance to treatment through T cell suppression and enhanced vascular formation (40, 41). The recruitment and activation of MDSCs involves complex molecular mechanisms, including the CRIP1/NF-κB/CXCL axis, where CRIP1 facilitates NF-κB nuclear translocation leading to CXCL1/5 secretion that drives MDSC chemotaxis and establishes immunosuppressive niches (42). PDAC-derived factors promote metabolic reprogramming of MDSCs, enhancing their immunosuppressive capacity (43, 44).

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis has identified distinct CAF subtypes that differentially contribute to PDAC pathogenesis, including inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs) characterized by high expression of inflammatory mediators and myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs) distinguished by elevated alpha-smooth muscle actin expression (45, 46). Recent studies have uncovered an interferon-response CAF (ifCAF) subtype with tumor-restraining properties that can be induced by STING agonists and can suppress tumor cell invasiveness (47, 48). Epigenetic alterations also play crucial roles, with loss of SETD2 leading to ectopic H3K27 acetylation that drives BMP2 signaling and promotes lipid-laden CAF differentiation (49). Stromal signals orchestrate epigenetic reprogramming through histone modifications, creating a BRD2-dependent regulatory hub that integrates oncogenic KRAS pathways with microenvironmental cues (50).

4 Diagnostic and predictive technologies

4.1 Molecular subtyping and spatial technologies

Molecular subtyping has identified distinct transcriptional programs that correlate with clinical outcomes and treatment responses. The classical and quasi-mesenchymal subtypes show differential responses to therapy, with classical tumors generally demonstrating better survival outcomes (51). Subsequent work revealed that pancreatic tumors contain independent tumor- and stroma-derived molecular signatures, with the worst clinical outcomes observed when basal-like tumor features co-occur with an activated stromal microenvironment (52). Recent consensus molecular subtyping approaches have integrated both tumor and microenvironmental features to provide a more comprehensive classification system (53). Spatial transcriptomic analysis reveals complex tissue architecture and distinct cellular neighborhoods within tumors (54). Integration with single-cell RNA sequencing uncovers cellular subtypes involved in aggressive features, though translating findings into therapeutic strategies remains challenging (14, 55).

4.2 Organoid models and liquid biopsy

Patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTOs) are three-dimensional culture systems that maintain key features of primary tumors, including genetic, histological, and drug response characteristics (10, 56). Drug sensitivity profiles of PDOs closely mirror patient treatment responses, demonstrating strong clinical predictive value (9, 57). Integration with advanced tools, such as label-free single-cell phenotyping, enables real-time assessment of tumor heterogeneity (58). These systems have identified novel therapeutic targets, exemplified by the discovery of perhexiline maleate, an inhibitor of mutant KRAS through cholesterol synthesis modulation (59).

PDAC organoids enable high-throughput screening and systematic evaluation of therapeutic compounds, with recent advances focusing on developing standardized protocols for organoid culture, drug screening assays, and data interpretation (60, 61). The integration of organoid screening with genomic profiling enhances the precision of treatment selection, enabling clinicians to predict chemotherapy resistance and improve therapeutic efficacy (8, 10).

Patient-derived organoids preserve transcriptional heterogeneity observed in primary tumors, with studies demonstrating that PDOs can maintain the coexistence of ‘classical’ and ‘basal-like’ transcriptional subtypes within individual organoid cultures (62). Single-cell transcriptomic analyses indicate this preserved cell state plasticity may influence therapeutic responses, potentially enabling investigation of subtype-dependent drug sensitivity patterns (63). From a practical perspective, PDOs can be established from endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy (UES-FNB) specimens with 70-87% success rate, providing a less invasive approach for unresectable cases (64). Cell-free DNA isolated from organoid culture supernatants as early as 72 hours post-biopsy can reflect the mutational profile of primary tumors, suggesting potential for rapid molecular characterization (65). Additionally, emerging data suggest that PDO morphology may correlate with molecular subtypes and should be classified within 2 weeks of tissue sampling (66). While these morphological patterns have shown association with treatment response and overall survival in initial studies, the predictive value of morphological subtyping requires validation in larger cohorts before routine clinical implementation can be recommended.

While PDOs offer significant advantages for personalized medicine, important limitations must be acknowledged that currently constrain their clinical implementation. The progressive loss of stromal components during serial passaging depletes immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and endothelial (67–69) This loss of tumor microenvironment interaction may result in incomplete recapitulation of drug responses that are modulated by stromal or immune factors, potentially limiting the ability to evaluate immunotherapies or agents targeting the tumor-stroma interface. Standard PDO cultures require sophisticated co-culture systems with patient-matched immune cells to adequately assess the immunotherapy responses (70). To address these limitations, ongoing research efforts are focused on developing complex organoid models that integrate immune components, vascular structures, and stromal elements to better recapitulate the native tumor microenvironment. Turnaround time of 3–4 weeks from tissue acquisition to drug screening results (71, 72) may exceed decision making windows for rapidly progressing disease. Technical establishment rates vary considerably across protocols and tissue sources, ranging from 20% to 90% depending on sample quality, biopsy technique, and culture methodology (73). This variability introduces potential selection bias, as failure may preferentially occur with less proliferative or more differentiated tumor subtypes.

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a valuable approach in oncology, offering noninvasive molecular profiling capabilities. Recent developments have focused on integrating multi-analyte liquid biopsy panels to provide comprehensive tumor profiling (74), enabling precision medicine by allowing clinicians to track molecular changes in real-time (75). Liquid biopsy technologies have demonstrated particular promise in pancreatic cancer due to inherent challenges of tissue acquisition (76). Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis enables noninvasive and dynamic monitoring of tumor burden and treatment response in pancreatic cancer patients (77). Surveillance programs utilizing advanced diagnostic technologies have demonstrated significant improvements in outcomes, with surveillance-detected PDAC showing better survival rates and earlier-stage diagnoses (78). While promising, significant challenges remain in standardizing protocols, improving sensitivity for early-stage disease, and demonstrating clinical utility through prospective trials.

5 Therapeutic innovations

5.1 KRAS-targeted and metabolic therapies

Large-scale genomic investigations demonstrated the prognostic importance of distinct KRAS mutations in patients with PDAC. In a significant analysis of 1,360 patients who underwent surgical treatment, tumors harboring KRAS G12R mutations were more frequently observed in early-stage cases and demonstrated reduced rates of distant metastasis along with superior overall survival outcomes relative to other KRAS mutation subtypes (79). The development of KRAS-targeted therapies has shown promising clinical results, with several inhibitors demonstrating anticancer activity in clinical trials (80). These developments represent significant advances in PDAC treatment, overcoming the long-standing challenge of targeting KRAS, which has emerged as a tractable therapeutic target (81). However, clinical experience remains limited, with most data from early-phase trials, and questions persist regarding optimal patient selection, resistance mechanisms, and long term efficacy.

PDAC cells undergo profound metabolic reprogramming to survive within a uniquely hypoxic and nutrient-scarce tumor microenvironment, creating targetable vulnerabilities. PDAC cells exhibit distinct metabolic subtypes characterized by enhanced glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and altered lipid metabolism, which correlate with differential sensitivities to specific metabolic inhibitors (82). Although autophagy suppression through chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine showed therapeutic potential in laboratory studies, randomized clinical trials have revealed limited clinical benefits attributed to adaptive upregulation of alternative nutrient scavenging mechanisms (83). Recognizing this compensatory response, researchers have developed combination strategies that simultaneously target both autophagic recycling and macropinocytic uptake pathways, resulting in enhanced antitumor efficacy in experimental PDAC models (84, 85). Additionally, disrupting glutamine metabolism using glutaminase inhibitors has shown promise in KRAS-driven PDAC models, particularly when combined with modulation of the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling axis (86, 87).

5.2 mRNA vaccines and immunotherapy

The development of personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccines represents a notable advance in PDAC immunotherapy. These vaccines deliver tumor-specific antigenic sequences to antigen-presenting cells, which then prime naïve T cells to recognize and eliminate cancer cells bearing these neoantigens, inducing potent neoantigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses (88). This mechanism leverages lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA, which is internally translated into target proteins, processed into peptides, and presented on MHC molecules to activate T cell responses. Early-phase clinical data for the adjuvant autogene cevumeran have shown significant clinical benefits, with vaccine-induced immune responses serving as a strong predictor of improved disease-free survival outcomes (11). Patients with vaccine-expanded T cells showed significantly prolonged recurrence-free survival compared to non-responders (median not reached vs. 13.4 months, P = 0.003).

Contemporary vaccine development has expanded beyond mRNA platforms to include diverse therapeutic modalities. The AMPLIFY-201 trial offered initial clinical evidence supporting the potential of standardized peptide vaccines targeting recurrent KRAS mutations and highlighted their ability to induce mutation-specific immune responses with acceptable safety (22). The TG01/GM-CSF vaccine targeting KRAS oncogenic mutations demonstrated high immunogenicity when combined with adjuvant gemcitabine in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma, with over 90% of patients showing positive immune responses and a median overall survival of 33.1 months (23). These findings support the continued development of multiple vaccine platforms with personalized mRNA vaccines leading the way toward precision immunotherapy of PDAC.

6 Discussion

PDAC represents a formidable oncological challenge with profound therapeutic resistance and poor outcomes. Recent biotechnological and clinical advances have created multiple complementary approaches toward improvement. The development of PDTOs that can accurately predict individual therapeutic responses (10, 56), clinical validation of personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccines capable of inducing robust antitumor immunity (11), and successful targeting of the KRAS oncogene (21, 89) collectively represents significant progress in PDAC research and treatment. Advanced diagnostic technologies such as spatial transcriptomics and multi-analyte liquid biopsies may offer a high-resolution perspective of tumor biology (52, 54, 76). Nevertheless, several critical barriers must be overcome before these technologies can be routinely integrated into clinical practice, including standardization of methods, and validation across diverse patient populations.

The development of patient-derived organoids and personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccines exemplifies complementary approaches in PDAC precision medicine. Organoids enable prospective identification of effective therapies through ex vivo drug screening, demonstrating strong concordance with clinical responses (10, 61), while mRNA vaccines extend precision medicine principles to immune-based relapse prevention by generating tumor-specific T cell responses, with vaccine responders showing significantly prolonged recurrence-free survival (11). These platforms address different stages of the therapeutic continuum—organoids for treatment selection and vaccines for adjuvant immunotherapy—yet both rely on patient-specific molecular information. Proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated that organoid-derived genomic profiles comparable to primary tumors (90, 91), which could theoretically inform rational neoantigen selection for vaccine design. However, clinical integration of these complementary platforms remains to be systematically validated. Future investigations are warranted to determine whether such integrated approaches can improve therapeutic outcomes beyond the independent application of each technology (92).

The clinical feasibility and therapeutic relevance of these approaches are no longer theoretical. Evidence from clinical trials indicates that patients harboring actionable molecular alterations have substantially improved median overall survival when treated with matched therapies, reinforcing the clinical validity of precision oncology approaches (93). Prospective studies such as COMPASS have shown that comprehensive genomic profiling can be delivered within a clinically actionable timeframe, with treatment outcomes strongly influenced by genomic and transcriptomic subtypes (94). Current ASCO guidelines emphasize routine molecular testing for microsatellite instability, BRCA mutations, and other actionable alterations to guide targeted therapies and immunotherapy (95).

While these technologies are advancing independently, their coordinated integration could form the basis for future strategies aimed at more comprehensive therapeutic management. The historical approach of applying static, one-size-fits-all regimens for biologically heterogeneous diseases is becoming obsolete (92). Emerging AI-driven platforms provide novel analytical capabilities for integrating complex datasets. AI-assisted analysis of temporal imaging from PDTO co-culture systems enables dynamic assessment of therapeutic responses (96), while machine learning algorithms integrate multi-omics data to enhance treatment prediction (97). These AI-based prognostic models demonstrate superior predictive performance compared to conventional staging approaches (98).

Nevertheless, significant challenges must be addressed. Analysis of refractory metastatic cancers has revealed that standard-of-care resistance biomarkers are identified in only 9.6% of treatment-resistant tumors, highlighting the urgent need for broader validation of investigational resistance mechanisms (99). As we deploy these novel therapies, we must anticipate and study the next generation of resistance mechanisms, such as acquired mutations that bypass KRAS inhibition (100) or immunoediting that allows tumors to escape vaccine-induced T cell responses (101, 102). The PDAC biology requires multifaceted therapeutic approaches including radiation-enhanced immunotherapy (103), dendritic cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies (24), mRNA vaccines with conventional chemotherapy (101), and organoid-guided personalized therapy with adaptive dosing strategies (71). Manufacturing scalability represents a critical bottleneck in personalized therapies, with mRNA vaccine production timelines requiring further optimization for routine clinical implementation (104).

In conclusion, the parallel development of patient-derived organoids for drug sensitivity testing, personalized mRNA vaccines for immune activation, and precision diagnostic technologies provides complementary tools that address different aspects of DPAC biology. While each approach has demonstrated independent clinical value, their long-term integration may provide a conceptual basis for more coordinated strategies in PDAC management. Although the prospect of converting pancreatic cancer from an invariably fatal diagnosis into a manageable chronic condition remains highly challenging, continued technological and therapeutic advances suggest incremental progress toward this goal. Achieving this vision will require sustained collaborative efforts from basic scientists, clinical researchers, bioinformaticians, regulatory bodies, and pharmaceutical partners to translate these significant scientific advances into meaningful improvements in patient outcomes.

Author contributions

WL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. H-MW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Hyun-Myung Woo was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00279241).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor MP declared a shared parent affiliation with the authors WL, JC & MK at the time of the review.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; iCAF, inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblast; ifCAF, interferon-response cancer-associated fibroblast; ITH, intratumor heterogeneity; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; myCAF, myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblast; OS, overall survival; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDTO, patient-derived tumor organoid.

References

1. Park W, Chawla A, and O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic cancer: a review. JAMA. (2021) 326:851–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13027

2. Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, and Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155

3. Halbrook CJ, Lyssiotis CA, Pasca di Magliano M, and Maitra A. Pancreatic cancer: advances and challenges. Cell. (2023) 186:1729–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.014

4. Ahmad RS, Eubank TD, Lukomski S, and Boone BA. Immune cell modulation of the extracellular matrix contributes to the pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:901. doi: 10.3390/biom11060901

5. Nusrat F, Khanna A, Jain A, Jiang W, Lavu H, Yeo CJ, et al. The clinical implications of kras mutations and variant allele frequencies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:2103. doi: 10.3390/jcm13072103

6. Evan T, Wang VM, and Behrens A. The roles of intratumour heterogeneity in the biology and treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. (2022) 41:4686–95. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02448-x

7. Driehuis E, Van Hoeck A, Moore K, Kolders S, Francies HE, Gulersonmez MC, et al. Pancreatic cancer organoids recapitulate disease and allow personalized drug screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 116:26580–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911273116

8. Xiang D, He A, Zhou R, Wang Y, Xiao X, Gong T, et al. Building consensus on the application of organoid-based drug sensitivity testing in cancer precision medicine and drug development. Theranostics. (2024) 14:3300. doi: 10.7150/thno.96027

9. Boj SF, Hwang CI, Baker LA, Chio II, Engle DD, Corbo V, et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. (2015) 160:324–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021

10. Tiriac H, Belleau P, Engle DD, Plenker D, Deschênes A, Somerville TD, et al. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. (2018) 8:1112–29. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0349

11. Rojas LA, Sethna Z, Soares KC, Olcese C, Pang N, Patterson E, et al. Personalized rna neoantigen vaccines stimulate t cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2023) 618:144–50. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06063-y

12. Liu X, Baer JM, Stone ML, Knolhoff BL, Hogg GD, Turner MC, et al. Stromal reprogramming overcomes resistance to ras-mapk inhibition to improve pancreas cancer responses to cytotoxic and immune therapy. Sci Transl Med. (2024) 16:eado2402. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05010-3

13. Connor AA, Denroche RE, Jang GH, Timms L, Kalimuthu SN, Selander I, et al. Association of distinct mutational signatures with correlates of increased immune activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:774–83. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3916

14. Hwang WL, Jagadeesh KA, Guo JA, Hoffman HI, Yadollahpour P, Reeves JW, et al. Single-nucleus and spatial transcriptome profiling of pancreatic cancer identifies multicellular dynamics associated with neoadjuvant treatment. Nat Genet. (2022) 54:1178–91. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01134-8

15. Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. Folfirinox versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923

16. Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:1691–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369

17. Wainberg ZA, Melisi D, Macarulla T, Pazo Cid R, Chandana SR, de la Fouchardière C, et al. Nalirifox versus nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in treatment-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (napoli 3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 402:1272–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01366-1

18. Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. Folfirinox or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:2395–406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775

19. Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the dutch randomized phase iii preopanc trial. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:1763–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02274

20. Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline brca-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:317–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387

21. Strickler JH, Satake H, George TJ, Yaeger R, Hollebecque A, Garrido-Laguna I, et al. Sotorasib in kras p.g12c–mutated advanced pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:33–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2208470

22. Pant S, Wainberg ZA, Weekes CD, Furqan M, Kasi PM, Devoe CE, et al. Lymph-node-targeted, mKRAS-specific amphiphile vaccine in pancreatic and colorectal cancer: the phase 1 AMPLIFY-201 trial. Nat Med. (2024) 30:531–42. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02760-3

23. Palmer DH, Valle JW, Ma YT, Faluyi O, Neoptolemos JP, Gjertsen TJ, et al. TG01/GM-CSF and adjuvant gemcitabine in patients with resected RAS-mutant adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (CT TG01-01): a single-arm, phase 1/2 trial. Br J Cancer. (2020) 122:971–7. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0752-7

24. van ‘t Land FR, Willemsen M, Bezemer K, van der Burg SH, van den Bosch TPP, Doukas M, et al. Dendritic cell–based immunotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2024) 42:3083–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.02585

25. Tsujikawa T, Crocenzi T, Durham JN, Sugar EA, Wu AA, Onners B, et al. Evaluation of cyclophosphamide/GVAX pancreas followed by Listeria-mesothelin (CRS-207) with or without nivolumab in patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2020) 26:3578–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3978

26. Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, De Jesus-Acosta A, Delord JP, et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair–deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02105

27. Taïeb J, Sayah L, Heinrich K, Kunzmann V, Boileve A, Cirkel G, et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in microsatellite unstable/mismatch repair-deficient advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: an AGEO European cohort. Eur J Cancer. (2023) 188:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.04.012

28. O’Reilly EM, Oh DY, Dhani N, Renouf DJ, Lee MA, Sun W, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab for patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2019) 5:1431–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1588

29. Campbell PJ, Yachida S, Mudie LJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, Stebbings LA, et al. The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2010) 467:1109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09460

30. Robertson-Tessi M, Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA, and Anderson AR. Impact of metabolic heterogeneity on tumor growth, invasion, and treatment outcomes. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:1567–79. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1428

31. Marusyk A, Janiszewska M, and Polyak K. Intratumor heterogeneity: the rosetta stone of therapy resistance. Cancer Cell. (2020) 37:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.007

32. Easwaran H, Tsai HC, and Baylin SB. Cancer epigenetics: tumor heterogeneity, plasticity of stem-like states, and drug resistance. Mol Cell. (2014) 54:716–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.015

33. Yu S, Zhang C, and Xie KP. Therapeutic resistance of pancreatic cancer: Roadmap to its reversal. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. (2021) 1875:188461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188461

34. Witkiewicz A, Williams TK, Cozzitorto J, Durkan B, Showalter SL, Yeo CJ, et al. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma recruits regulatory t cells to avoid immune detection. J Am Coll Surg. (2008) 206:849–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.014

35. Qi R, Bai Y, Li K, Liu N, Xu Y, Dal E, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts suppress ferroptosis and induce gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells by secreting exosome-derived acsl4-targeting mirnas. Drug Resist Updat. (2023) 68:100960. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2023.100960

36. Yamamoto K, Venida A, Yano J, Biancur DE, Kakiuchi M, Gupta S, et al. Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading mhc-i. Nature. (2020) 581:100–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2229-5

37. Klomp JA, Klomp JE, Stalnecker CA, Bryant KL, Edwards AC, Drizyte-Miller K, et al. Defining the kras-and erk-dependent transcriptome in kras-mutant cancers. Science. (2024) 384:eadk0775. doi: 10.1126/science.adk0775

38. Gatenby RA and Brown JS. The evolution and ecology of resistance in cancer therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2020) 10:a040972. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a040972

39. Markowitz J, Brooks TR, Duggan MC, Paul BK, Pan X, Wei L, et al. Patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma exhibit elevated levels of myeloid-derived suppressor cells upon progression of disease. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2015) 64:149–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1618-8

40. Zhang Y, Velez-Delgado A, Mathew E, Li D, Mendez FM, Flannagan K, et al. Myeloid cells are required for pd-1/pd-l1 checkpoint activation and the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment in pancreatic cancer. Gut. (2017) 66:124–36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312078

41. Blidner AG, Bach CA, García PA, Merlo JP, Cagnoni AJ, Bannoud N, et al. Glycosylation-driven programs coordinate immunoregulatory and pro-angiogenic functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunity. (2025) 58:1553–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2025.04.027

42. Liu X, Tang R, Xu J, Tan Z, Liang C, Meng Q, et al. Crip1 fosters mdsc trafficking and resets tumour microenvironment via facilitating nf-κb/p65 nuclear translocation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut. (2023) 72:2329–43. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-329349

43. Chen Q, Yin H, He J, Xie Y, Wang W, Xu H, et al. Tumor microenvironment responsive cd8+ t cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells to trigger cd73 inhibitor ab680-based synergistic therapy for pancreatic cancer. Adv Sci. (2023) 10:2302498. doi: 10.1002/advs.202302498

44. Pan D, Li X, Qiao X, and Wang Q. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1582305. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1582305

45. Ohlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. (2017) 214:579–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162024

46. Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, Flynn WF, Courtois ET, Burkhart RA, et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. (2019) 9:1102–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0094

47. Cumming J, Maneshi P, Dongre M, Alsaed T, Dehghan-Nayeri MJ, Ling A, et al. Dissecting fap+ cell diversity in pancreatic cancer uncovers an interferon-response subtype of cancer-associated fibroblasts with tumor-restraining properties. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:2388–411. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-3252

48. Chen Y, Kim J, Yang S, Wang H, Wu CJ, Sugimoto H, et al. Type i collagen deletion in αsma+ myofibroblasts augments immune suppression and accelerates progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:548–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.02.007

49. Biffi G, Oni TE, Spielman B, Hao Y, Elyada E, Park Y, et al. Il1-induced jak/stat signaling is antagonized by tgfβ to shape caf heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. (2019) 9:282–301. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0710

50. Sherman MH, Yu RT, Tseng TW, Sousa CM, Liu S, Truitt ML, et al. Stromal cues regulate the pancreatic cancer epigenome and metabolome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:1129–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620164114

51. Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med. (2011) 17:500–3. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344

52. Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, Volmar KE, Loeza SG, Hoadley KA, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor-and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:1168–78. doi: 10.1038/ng.3398

53. Puleo F, Nicolle R, Blum Y, Cros J, Marisa L, Demetter P, et al. Stratification of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas based on tumor and microenvironment features. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:1999–2013. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.033

54. Moncada R, Barkley D, Wagner F, Chiodin M, Devlin JC, Baron M, et al. Integrating microarray-based spatial transcriptomics and single-cell rna-seq reveals tissue architecture in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Nat Biotechnol. (2020) 38:333–42. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0392-8

55. Grünwald BT, Devisme A, Andrieux G, Vyas F, Aliar K, McCloskey CW, et al. Spatially confined sub-tumor microenvironments in pancreatic cancer. Cell. (2021) 184:5577–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.022

56. Romero-Calvo I, Weber CR, Ray M, Brown M, Kirby K, Nandi RK, et al. Human organoids share structural and genetic features with primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumors. Mol Cancer Res. (2019) 17:70–83. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0531

57. Huang L, Holtzinger A, Jagan I, BeGora M, Lohse I, Ngai N, et al. Ductal pancreatic cancer modeling and drug screening using human pluripotent stem cell–and patient-derived tumor organoids. Nat Med. (2015) 21:1364–71. doi: 10.1038/nm.3973

58. Wittenzellner K, Lengl M, Röhrl S, Maurer C, Klenk C, Papargyriou A, et al. Label-free single cell phenotyping to determine tumor cell heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer in real-time. JCI Insight. (2025) 10(13):e169105. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.169105

59. Duan X, Zhang T, Feng L, de Silva N, Greenspun B, Wang X, et al. A pancreatic cancer organoid platform identifies an inhibitor specific to mutant kras. Cell Stem Cell. (2024) 31:71–88. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.11.011

60. Zuo J, Fang Y, Wang R, and Liang S. High-throughput solutions in tumor organoids: from culture to drug screening. Stem Cells. (2025) 43:sxae070. doi: 10.1093/stmcls/sxae070

61. Grossman JE, Muthuswamy L, Huang L, Akshinthala D, Perea S, Gonzalez RS, et al. Organoid sensitivity correlates with therapeutic response in patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2022) 28:708–18. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4116

62. Krieger TG, Le Blanc S, Jabs J, Ten FW, Ishaque N, Jechow K, et al. Single-cell analysis of patient-derived pdac organoids reveals cell state heterogeneity and a conserved developmental hierarchy. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:5826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26059-4

63. Raghavan S, Winter PS, Navia AW, Williams HL, DenAdel A, Lowder KE, et al. Microenvironment drives cell state, plasticity, and drug response in pancreatic cancer. Cell. (2021) 184:6119–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.017

64. Tiriac H, Bucobo JC, Tzimas D, Grewel S, Lacomb JF, Rowehl LM, et al. Successful creation of pancreatic cancer organoids by means of eus-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling for personalized cancer treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. (2018) 87:1474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.12.032

65. Kim H, Jang J, Choi JH, Song JH, Lee SH, Park J, et al. Establishment of a patient-specific avatar organoid model derived from eus-guided fine-needle biopsy for timely clinical application in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. (2024) 100:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2024.02.021

66. Matsumoto K, Fujimori N, Ichihara K, Takeno A, Murakami M, Ohno A, et al. Patient-derived organoids of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma for subtype determination and clinical outcome prediction. J Gastroenterol. (2024) 59:629–40. doi: 10.1007/s00535-024-02103-0

67. Hu JW, Pan YZ, Zhang XX, Li JT, and Jin Y. Applications and challenges of patient-derived organoids in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers. World J Gastroenterol. (2025) 31:106747. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i20.106747

68. Yao N, Jing N, Lin J, Niu W, Yan W, Yuan H, et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids for cancer immunotherapy: culture techniques and clinical application. Invest New Drugs. (2025) 43(2):394–404. doi: 10.1007/s10637-025-01523-w

69. Yin X, Mead BE, Safaee H, Langer R, Karp JM, and Levy O. Stem cell organoid engineering. Cell Stem Cell. (2016) 18:25. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.12.005

70. Grönholm M, Feodoroff M, Antignani G, Martins B, Hamdan F, and Cerullo V. Patient-derived organoids for precision cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:3149–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-4026

71. Boilève A, Cartry J, Goudarzi N, Bedja S, Mathieu JR, Bani MA, et al. Organoids for functional precision medicine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. (2024) 167:961–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.032

72. Foo MA, You M, Chan SL, Sethi G, Bonney GK, Yong WP, et al. Clinical translation of patient-derived tumour organoids-bottlenecks and strategies. biomark Res. (2022) 10:10. doi: 10.1186/s40364-022-00356-6

73. Thorel L, Perréard M, Florent R, Divoux J, Coffy S, Vincent A, et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids: a new avenue for preclinical research and precision medicine in oncology. Exp Mol Med. (2024) 56:1531–51. doi: 10.1038/s12276-024-01272-5

74. Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, and Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:531–48. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.14

75. Hou J, Li X, and Xie KP. Coupled liquid biopsy and bioinformatics for pancreatic cancer early detection and precision prognostication. Mol Cancer. (2021) 20:34. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01309-7

76. Heredia-Soto V, Rodríguez-Salas N, and Feliu J. Liquid biopsy in pancreatic cancer: are we ready to apply it in the clinical practice? Cancers. (2021) 13:1986. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081986

77. Kirchweger P, Kupferthaler A, Burghofer J, Webersinke G, Jukic E, Schwendinger S, et al. Prediction of response to systemic treatment by kinetics of circulating tumor dna in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:902177. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.902177

78. Blackford AL, Canto MI, Dbouk M, Hruban RH, Katona BW, Chak A, et al. Pancreatic cancer surveillance and survival of high-risk individuals. JAMA Oncol. (2024) 10:1087–96. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.1930

79. McIntyre CA, Grimont A, Park J, Meng Y, Sisso WJ, Seier K, et al. Distinct clinical outcomes and biological features of specific kras mutants in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:1614–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.08.002

80. Janes MR, Zhang J, Li LS, Hansen R, Peters U, Guo X, et al. Targeting kras mutant cancers with a covalent g12c-specific inhibitor. Cell. (2018) 172:578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.006

81. Waters AM and Der CJ. Kras: the critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2018) 8:a031435. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031435

82. Daemen A, Peterson D, Sahu N, McCord R, Du X, Liu B, et al. Metabolite profiling stratifies pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas into subtypes with distinct sensitivities to metabolic inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2015) 112:E4410–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501605112

83. Karasic TB, O’Hara MH, Loaiza-Bonilla A, Reiss KA, Teitelbaum UR, Borazanci E, et al. Effect of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel with or without hydroxychloroquine on patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2019) 5:993–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0684

84. Su H, Yang F, Fu R, Li X, French R, Mose E, et al. Cancer cells escape autophagy inhibition via NRF2-induced macropinocytosis. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:678–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.02.016

85. Kinsey CG, Camolotto SA, Boespflug AM, Guillen KP, Foth M, Truong A, et al. Protective autophagy elicited by RAF→MEK→ERK inhibition suggests a treatment strategy for RAS-driven cancers. Nat Med. (2019) 25:620–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0367-9

86. Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. (2013) 496:101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12040

87. Mukhopadhyay S, Goswami D, Adiseshaiah PP, Burgan W, Yi M, Guerin TM, et al. Undermining glutaminolysis bolsters chemotherapy while NRF2 promotes chemoresistance in KRAS-driven pancreatic cancers. Cancer Res. (2020) 80:1630–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1363

88. Guasp P, Reiche C, Sethna Z, and Balachandran VP. Rna vaccines for cancer: Principles to practice. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:1163–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.05.005

89. Wasko UN, Jiang J, Dalton TC, Curiel-Garcia A, Edwards AC, Wang Y, et al. Tumour-selective activity of ras-gtp inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2024) 629:927–36. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07379-z

90. Xiao Y, Li Y, Jing X, Weng L, Liu X, Liu Q, et al. Organoid models in oncology: advancing precision cancer therapy and vaccine development. Cancer Biol Med. (2025) 22:903–27. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2025.0127

91. Levink IJM, Brosens LAA, Rensen SS, Aberle MR, Olde Damink SSW, Cahen DL, et al. Neoantigen quantity and quality in relation to pancreatic cancer survival. Front Med. (2022) 8:751110. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.751110

92. Casolino R, Braconi C, Malleo G, Paiella S, Bassi C, Milella M, et al. Reshaping preoperative treatment of pancreatic cancer in the era of precision medicine. Ann Oncol. (2021) 32:183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.013

93. Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, Lyons E, DeArbeloa P, Hendifar A, et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the know your tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:508–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30074-7

94. Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, Jang GH, Dodd A, Creighton S, et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the compass trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2018) 24:1344–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2994

95. Sohal DP, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, Conroy T, Copur MS, Crane CH, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: Asco guideline update. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:3217–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01364

96. Ferreira N, Kulkarni A, Agorku D, Midelashvili T, Hardt O, Legler TJ, et al. Organoidnet: a deep learning tool for identification of therapeutic effects in pdac organoid-pbmc cocultures from time-resolved imaging data. Cell Oncol. (2025) 48:101–22. doi: 10.1007/s13402-024-00958-2

97. Osipov A, Nikolic O, Gertych A, Parker S, Hendifar A, Singh P, et al. The molecular twin artificial-intelligence platform integrates multi-omic data to predict outcomes for pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients. Nat Cancer. (2024) 5:299–314. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00697-7

98. Wang L, Liu Z, Liang R, Wang W, Zhu R, Li J, et al. Comprehensive machine-learning survival framework develops a consensus model in large-scale multicenter cohorts for pancreatic cancer. Elife. (2022) 11:e80150. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80150.sa2

99. Pradat Y, Viot J, Yurchenko AA, Gunbin K, Cerbone L, Deloger M, et al. Integrative pan-cancer genomic and transcriptomic analyses of refractory metastatic cancer. Cancer Discov. (2023) 13:1116–43. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0966

100. Dilly J, Hoffman MT, Abbassi L, Li Z, Paradiso F, Parent BD, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to oncogenic kras inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. (2024) 14:2135–61. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-24-0177

101. Sethna Z, Guasp P, Reiche C, Milighetti M, Ceglia N, Patterson E, et al. Rna neoantigen vaccines prime long-lived cd8+ t cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2025) 639(8056):1042–51. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08508-4

102. Mukherjee P, Ginardi AR, Madsen CS, Tinder TL, Jacobs F, Parker J, et al. Muc1-specific ctls are non-functional within a pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Glycoconj J. (2001) 18:931–42. doi: 10.1023/A:1022260711583

103. Parikh AR, Szabolcs A, Allen JN, Clark JW, Wo JY, Raabe M, et al. Radiation therapy enhances immunotherapy response in microsatellite stable colorectal and pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a phase ii trial. Nat Cancer. (2021) 2:1124–35. doi: 10.1038/s43018-021-00269-7

Keywords: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, patient-derived organoids, mRNA neoantigen vaccines, precision medicine, KRAS mutation, immunotherapy, drug resistance

Citation: Lee W, Woo H-M, Cho JH and Kim MS (2025) Complementary strategies in pancreatic cancer precision medicine: therapeutic prediction and immune modulation. Front. Oncol. 15:1718911. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1718911

Received: 07 October 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Moon Nyeo Park, Kyung Hee University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Zhuolong Zhou, Zhejiang University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Lee, Woo, Cho and Kim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Man S. Kim, bWFuc2tpbUBraHUuYWMua3I=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wonmin Lee

Wonmin Lee Hyun-Myung Woo

Hyun-Myung Woo Ja Hyang Cho4

Ja Hyang Cho4 Man S. Kim

Man S. Kim