- 1Department of Radiation Medicine, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, WA, United States

- 2Department of Physics, George Washington University, Washington, WA, United States

Background/objectives: Studies involving the interaction of protons with boron (11B) have shown potential for enhanced cell killing in cancer cells. However, theoretical analyses conducted using Monte Carlo simulations have not corroborated the experimental findings. Our objective is to independently investigate the effects of proton-boron capture interaction on the killing of cancer cells in SQ20-B and MCF-7 cells.

Methods: Cell survival and DNA damage endpoints were analyzed in radiation resistant SQ-20B cells and in radiation sensitive MCF-7 cancer cells after exposure to 11B (BSH11) and proton irradiation. Clonogenic cell survival curves were assessed to fit the Linear Quadratic (LQ) and Single-Hit Multi-Target (SHMT) models. Additionally, γH2AX foci were quantified to evaluate DNA damage up to 24 hours post irradiation, comparing the effects of proton irradiation alone to proton irradiation in the presence of boron in SQ-20B cells.

Results: Exposure of cells to BSH11 resulted in decreased survival of SQ-20B cells following proton irradiation as compared to untreated control cells. Assays measuring γH2AX showed prolonged presence of γH2AX foci in cells after proton exposure in the presence of BSH11. In contrast, cells treated with BSH11 and irradiated with Cs-137 γ-rays did not show cell killing enhancement. Additionally, cells treated with BSH10, an analog of BSH11 that contains only 10B, displayed no change in survival after proton irradiation compared to untreated cells.

Conclusions: Our data show a small enhancement of cell killing by proton radiation in the presence of BSH11 that we attribute to the proton-boron interaction. Analysis of γH2AX demonstrates a prolonged duration of foci formation in cells after proton irradiation in the presence of BSH11. Further research will be needed to better understand the potential clinical applications of proton-boron interaction.

Introduction

The primary advantage of proton radiotherapy (RT) compared to photon RT is the unique energy deposition associated with the Bragg peak, which results in no radiation dose delivered beyond this peak (1, 2). In addition to utilizing the inherent physical and biological properties of protons in radiotherapy, further strategies have been explored to enhance their biological effectiveness (3, 4).

One of the strategies is to explore interaction between proton and boron and the products it produces. Upon absorption of a proton, a stable isotope of boron (11B) is converted into a 12C nucleus in an excited state, which subsequently decays to an 8Be nucleus and emits a α particle of energy 3.76 MeV. The 8Be nucleus further decays into two α particles of energy 2.74 MeV each (5). When placed in a cell medium, the three α particles produced in this process possess enough energy to traverse several cancer cells of typical thickness of 10-20 µm. Mindful of the high lethality of α particles (6, 7), one can expect an enhancement of cell killing by proton irradiation when a 11B containing compound is introduced into the cell medium.

The experimental data presented by Cirrone et al. on the effectiveness of proton-boron capture therapy offered the first evidence of the potential efficacy of proton-boron capture therapy (PBCT) (8). However, subsequent theoretical studies have questioned the validity of the mechanisms proposed in this report (5, 9, 10). The concerns are primarily based on Monte Carlo simulation of the proton-boron capture interaction and the amount of energy released in the process, with a consensus among the authors that the energy released is too small to support the magnitude of effects on cell survival reported by Cirrone et al.

This study reports additional experimental data on potential efficacy of proton-boron interaction in cell killing. By employing a 11B containing compound (BSH11) and two cancer cell lines of different radiation sensitivity, we hope to gain insight on the potential cell killing effects of α particles as well as that of protons. To account for the fact that BSH11 contains 80% 11B and 20% 10B and the presence of secondary neutrons in the proton irradiation experiments, we irradiated with protons cells treated with BSH10 compound that contains over 99.97% 10B to evaluate the possibility of cell killing resulting from 10B and neutron capture interaction. In addition, BSH11 treated cells were also irradiated with photons to evaluate potential biological effects of BSH11.

Materials and methods

Two cell lines were used in this study: the radioresistant SQ20-B cell line, which originated from squamous carcinoma of head and neck origin and is known for its radiation resistance and the radiosensitive MCF-7 cell line, which was derived from breast cancer and is more radiosensitive than other cell lines. These two cell lines allow for an analysis of the different radiation effects induced by densely ionizing particles, such as alpha particles which may have the potential to overcome the radiation resistance of cancer cells (6, 7). In addition to colony formation-based survival studies, we assessed DNA double-strand break (DSB) damage by quantifying γH2AX at various time points following irradiation.

Cell growth and cytotoxicity assay

Cells were obtained from the Lombardi Cancer Center Tissue Culture Core Facility at Georgetown University Medical Center. SQ-20B cells were maintained in complete DMEM media: DMEM, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 5% Pen/Strep. MCF-7 cells were cultured in complete RPMI media: RPMI, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 5% Pen/Strep. Both cell lines were kept in logarithmic growth phase at 370C and 5% CO2 environment and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Cytotoxicity assays were performed by exposing cells to graded drug dilutions for 48 hours. Cytotoxicity was measured using the CellTox Green Cytotoxicity Assay (Cat.#G8731, Promega), following manufacturer’s instructions. Positive and negative controls were included to ensure proper normalization of the results. Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring fluorescence at 513 nm excitation/532 nm emission. Cell viability is expressed as a percentage of the control groups. The inhibitory concentration values of 50% (IC50) values and the mean value of IC50 were calculated using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc).

Boron containing BSH compounds

This investigation utilized two BSH compounds: BSH11 and BSH10. The compounds, BSH11 (sodium mercaptododecaborate or N-BSH, Na2[1-SH11B12H11]) and BSH10 Compound (sodium mercaptododecaborate (10B), BSH, Na2[1-SH10B12H11] were purchased from KATCHEM Ltd, a commercial vendor (Czech Republic). The primary compound used in this research was BSH11, which has a boron isotope distribution of 80% 11B and 20% 10B; in contrast, BSH10, which contains 99.97% 11B, served as a control to assess the potential effects of boron neutron capture reaction during interactions with BSH11 and protons. The BSH compounds were in powder form and were dissolved in deionized, distilled water to achieve appropriate dilutions, resulting in a concentration of 50 µM, equivalent to 6.6 ppm for B11.

Proton irradiation

Proton irradiations were conducted at the Proton Center of Medstar Georgetown University Hospital using the Mevion S250i pencil beam scanning proton system. The radiation field consisted of a single energy layer of 85 MeV, with a field size of 20x20 cm2, comprising 1681 spots spaced 5 mm apart. Each spot received a monitor unit (MU) of 1.358. Cells in petri dishes, in a medium 1-mm thick, were positioned on top of a 5-cm solid water plate and CT scanned. Figure 1A shows the transverse CT image of the apparatus, where the light gray colored block shows the solid water plate and 3 containers on top show the petri dishes; the light gray colored layers at the bottom of the dishes show the cell containing liquid, as pointed by the white arrow. The CT images were imported into a Raystion treatment planning system (RS11A) by Raysearch Laboratories (Stochholm, Sweden) to generate radiation dose distribution from a single proton beam as defined above and directed posteriorly at the bottom of the solid water plate for irradiation of the cells. Figure 1B shows the Bragg peak curve of the beam and the arrow shows the position of the cells. This setup ensured that the dose delivery to the cell medium was maintained within the proximal 90% to distal 90% region of the Bragg peak. The doses were further measured using a calibrated parallel plate chamber with measurements taken in 1-mm increment along the beam direction to confirm that the dose variation within the irradiated medium is less than 10%. For each radiation delivery, six-well plates containing cells were placed within the treatment field. Doses of 0 (sham), 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 Gy were administered in triplicate to facilitate statistical error determination.

Figure 1. CT image of the irradiation apparatus (A) and the Bragg peak curve calculated by the Raystation treatment planning system. The arrow in (A) shows the location of the cell medium in one of the petri dishes, and the arrow in (B) shows the location of cell medium relative to the Bragg peak. The Y-axis shows the calculated RBE dose of proton along the beam path normalized to the maximum dose at the Bragg peak. The X axis shows the distance starting from the bottom of the solid water plate.

Photon irradiation

Photon irradiation of the cells was conducted at Georgetown University Lombardi Cancer Center’s core facility using a Cs-137 γ−irradiator on BSH11 treated SQ-20B cells. The dose rate of this irradiator was 1.56 Gy/min. Sample preparation and the doses delivered were consistent with previously detailed methods, except for the radiation source.

Cell survival assay

Cells were seeded into T25 flasks and treated with the drug for 48 hours prior to proton irradiation. The treatments included a Sham group (no drug) and the BSH11 compound at a concentration of 50 μM. As a control to evaluate any potential cell-killing effects of neutron-boron interaction that might occur in the proton-BSH11 reaction, the BSH10 compound was infused in another batch of SQ-20B cells at the same concentration. Each treatment was conducted in triplicate. Following irradiation, cells were incubated for 10–14 days post radiation until colony formation was observed. The cell survival data were fitted with the Linear-Quadratic (LQ) model for calculation of survival at various dose levels and alpha and beta values, The Single-Hit-Multi-Target (SHMT) model was also used for determination of D0. Mean and standard deviation were calculated from three repeats of each experiment. Unpaired student t-test was used for evaluation of statistical significance.

H2AX analysis

SQ-20B cells were treated with the BSH11 compound at a concentration of 50 μM for 48 hours prior to exposure to 5 Gy of proton radiation. Sham-treated cells served as control. Cells were fixed for 15 min using 4% formaldehyde at various time points (30min, 1hr, 2hrs, 4hrs, 6hrs, 12hrs and 24hrs) following irradiation. After fixation in 4% Formaldehyde, the cells were blocked for 1 hour using a Blocking Buffer (95% PBS, 5% Goat Serum and 0.3% TritonX-100) and incubated with γH2AX antibody (Abcam) overnight at 40C, followed by incubation with a secondary anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 for 1hr. Fluorescence images were captured using a Leica SP8 AOBS Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope after mounting the cells with Scale bar = 200 µm for all images. The number of distinct foci in individual nuclei was counted for each condition. Two-sample unpaired t-tests were performed for statistical analysis.

Results

There were no observed cytotoxicities to BSH11 or BSH10 exposures of SQ-20B or MCF7 cells to concentration from 1 to 50 μM. BSH is non-toxic in these cancer cells at the concentrations used in these experiments. Therefore, we selected a concentration of 50 μM for radiation experiments.

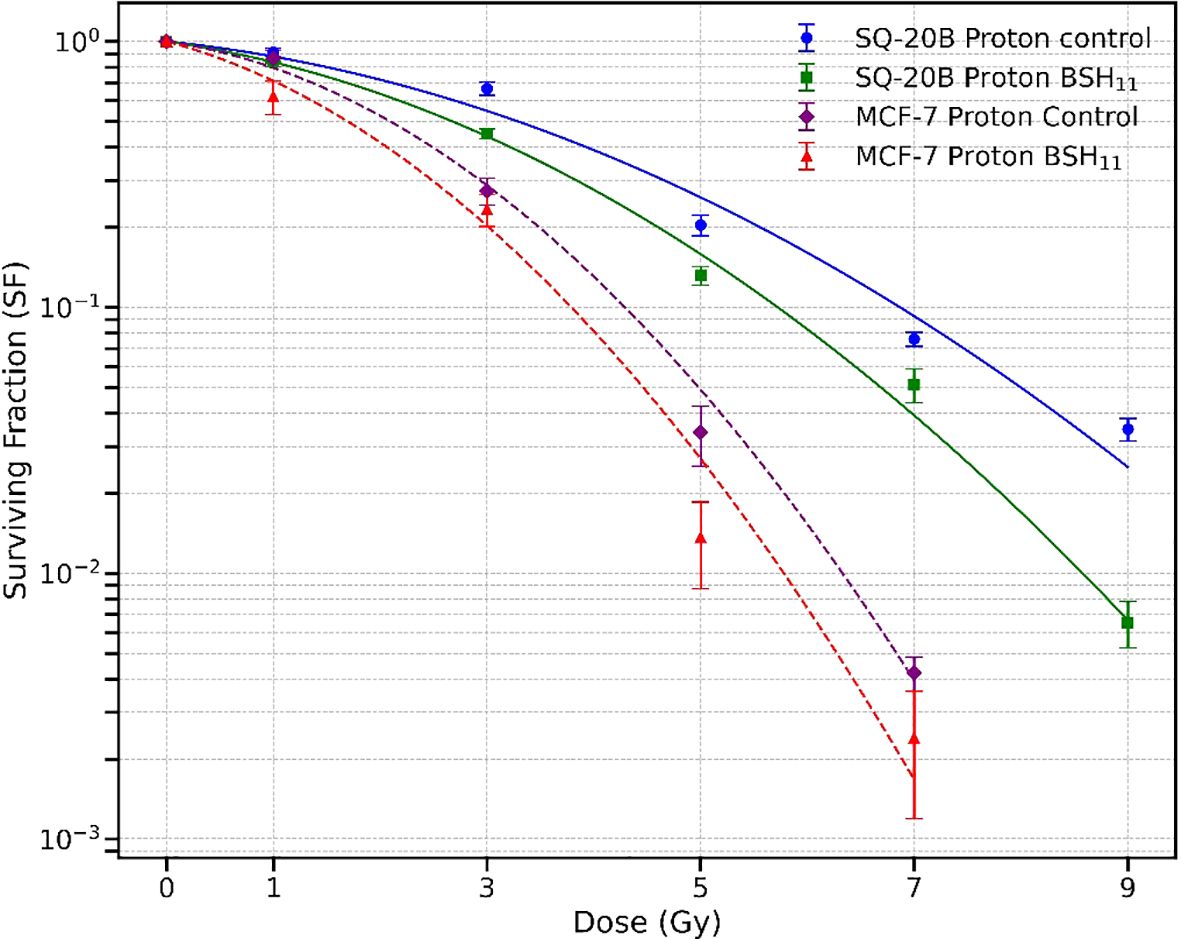

Figure 2 shows the cell survival curves for SQ20-B and MCF-7 cells irradiated with protons alone and with protons combined with 50 µM BSH11. Solid curves correspond to SQ-20B, while dashed curves correspond to MCF-7. Across the dose range, the addition of BSH11 reduced survival for both cell lines, consistent with a radiation sensitizing effect. Radiation resistant SQ-20B cells consistently exhibited higher survivals than MCF-7 cells.

Figure 2. Survival curves for SQ-20B (solid lines) and MCF-7 (dashed lines) cell lines following proton irradiation, with and without 50 µM BSH11. For SQ-20B, circles represent control (no BSH11) and squares represent BSH11-treated cells; for MCF-7, diamonds represent control, and triangles represent BSH11-treated cells. Data points represent the mean ± standard error from three independent experiments. Curves were obtained from log-scale least-squares fit the experimental data.

Dose by dose analysis using the LQ model revealed that BSH11 treatment significantly decreased SQ-20B survival at 3 Gy (p = 0.0069), 5 Gy (p = 0.0266), 7 Gy (p = 0.0473), and 9 Gy (p = 0.0014) indicating a pronounced effect at intermediate and high doses. For MCF-7, although survival was consistently lower in the BSH11 group, the dose points did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). The LQ model derived D10 (dose required to reduce cell survival to 10%) further reflected these differences. In SQ-20B cells, D10 decreased from 6.890 ± 0.134 Gy to 5.776 ± 0.080 Gy with BSH11 (p = 0.0002), corresponding to a dose-modifying factor (DMF - ratio of the dose required to achieve 10% survival without BSH to that with BSH) of 1.19, which indicates an enhanced overall radiation sensitizing effect. In MCF-7 cells, D10 decreased from 4.322 ± 0.090 Gy to 3.994 ± 0.512 Gy (p = 0.3360), giving a DMF of 1.08, but this change was not statistically significant.

From the SHMT model, the D0, defined as the dose that reduces cell survival to 37% in the exponential portion of the survival curve, was significantly reduced in SQ-20B cells from 1.874 ± 0.108 Gy (control) to 1.523 ± 0.102 Gy with BSH11 treatment (p = 0.0149). This decrease indicates an increased intrinsic radiosensitivity of SQ-20B cells in the presence of BSH11. In contrast, MCF-7 cells showed no significant changes in D0 between control (0.941 ± 0.105 Gy) and BSH11-treated (0.948 ± 0.154 Gy) groups (p = 0.9529) which suggests that the intrinsic sensitivity of MCF-7 to proton irradiation was not altered by BSH11.

The BSH11 compound contains 80% 11B and 20% 10B; therefore, the 10B component could contribute to the observed cellular effects of BSH11 through the boron-neutron interaction. To investigate this possibility, we irradiated SQ-20B cells with protons after treatment with BSH10 which contains 99.97% of 10B. Figure 3 shows the resulting survival curves. No statistically significant differences in survival were observed between the BSH10-treated and control groups with D10 values of 6.23 ± 0.30 Gy and 5.78 ± 0.23 Gy, respectively (p = 0.1117). These findings suggest that 10B, in the absence of 11B, does not significantly alter proton radiosensitivity in SQ-20B cells under the tested conditions.

Figure 3. Survival curves for SQ-20B cells irradiated with protons alone (circles) or with 50 µM BSH10 treatment (squares). Data points represent the mean ± standard error from three independent experiments. Curves were fitted using the Linear–Quadratic (LQ) model. No statistically significant differences in D10 were observed between the two groups (p = 0.1117).

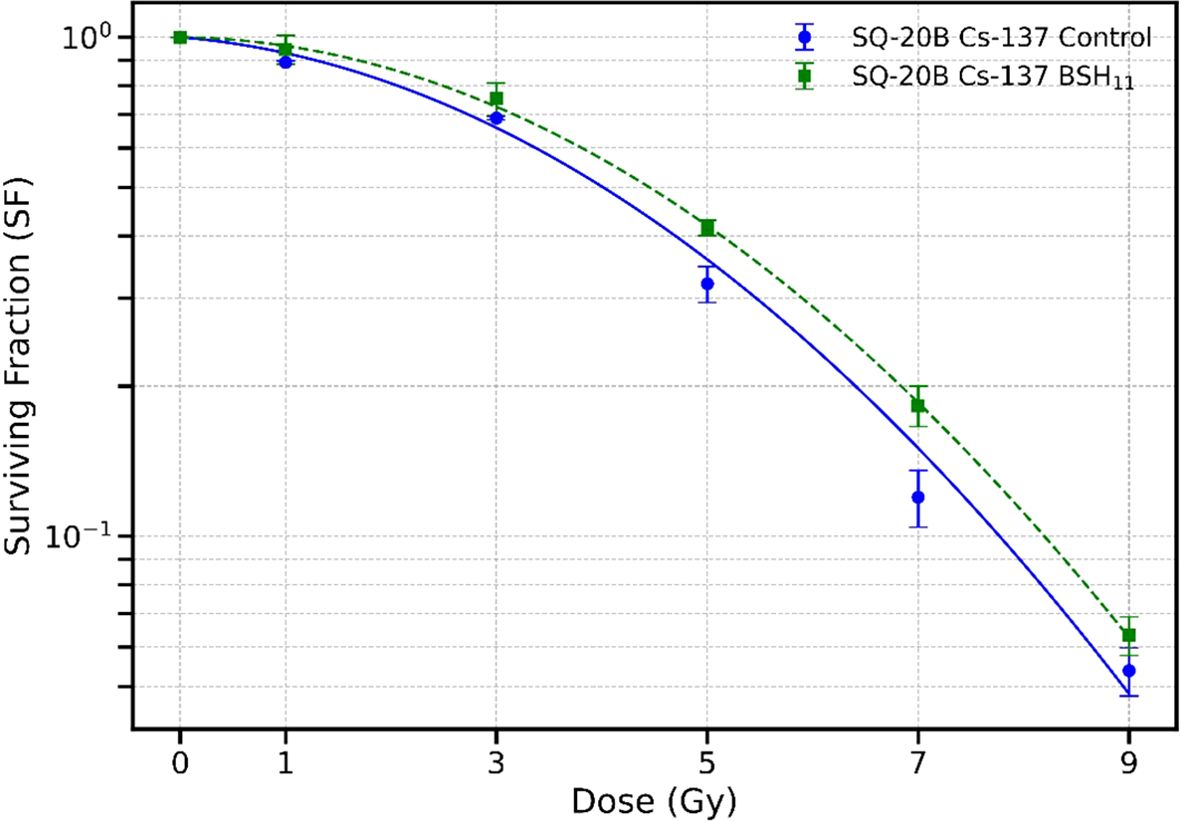

To further evaluate the role of the proton-11B interaction, we irradiated SQ-20B cells with Cs-137 gamma rays in a Cesium irradiator with and without BSH11 treatment. To rule out any purely chemical effects of the BSH compound, the BSH11 concentration was increased from 50 to 450 µM. Figure 4 shows the corresponding survival curves. Treatment with BSH11 did not produce a statistically significant change in survival when cells were irradiated with gamma photons, with D10 values of 7.78 ± 0.23 Gy for control cells and 8.21 ± 0.25 Gy for BSH11-treated cells (p = 0.0920). These results indicate that the survival differences observed in proton-irradiated SQ-20B cells are unlikely to be due to chemical effects of BSH11 but rather to the specific interaction between protons and 11B.

Figure 4. Survival curves for SQ-20B cells irradiated with Cs-137 gamma rays in the absence (circle) and presence (square) of 450 µM BSH11. Data points represent the mean ± standard error from three independent experiments. Data fitted with LQ model. No statistically significant difference in survival was observed between the two groups with D10 values of 7.78 ± 0.23 Gy (control) and 8.21 ± 0.25 Gy (BSH11) (p = 0.0920).

H2AX

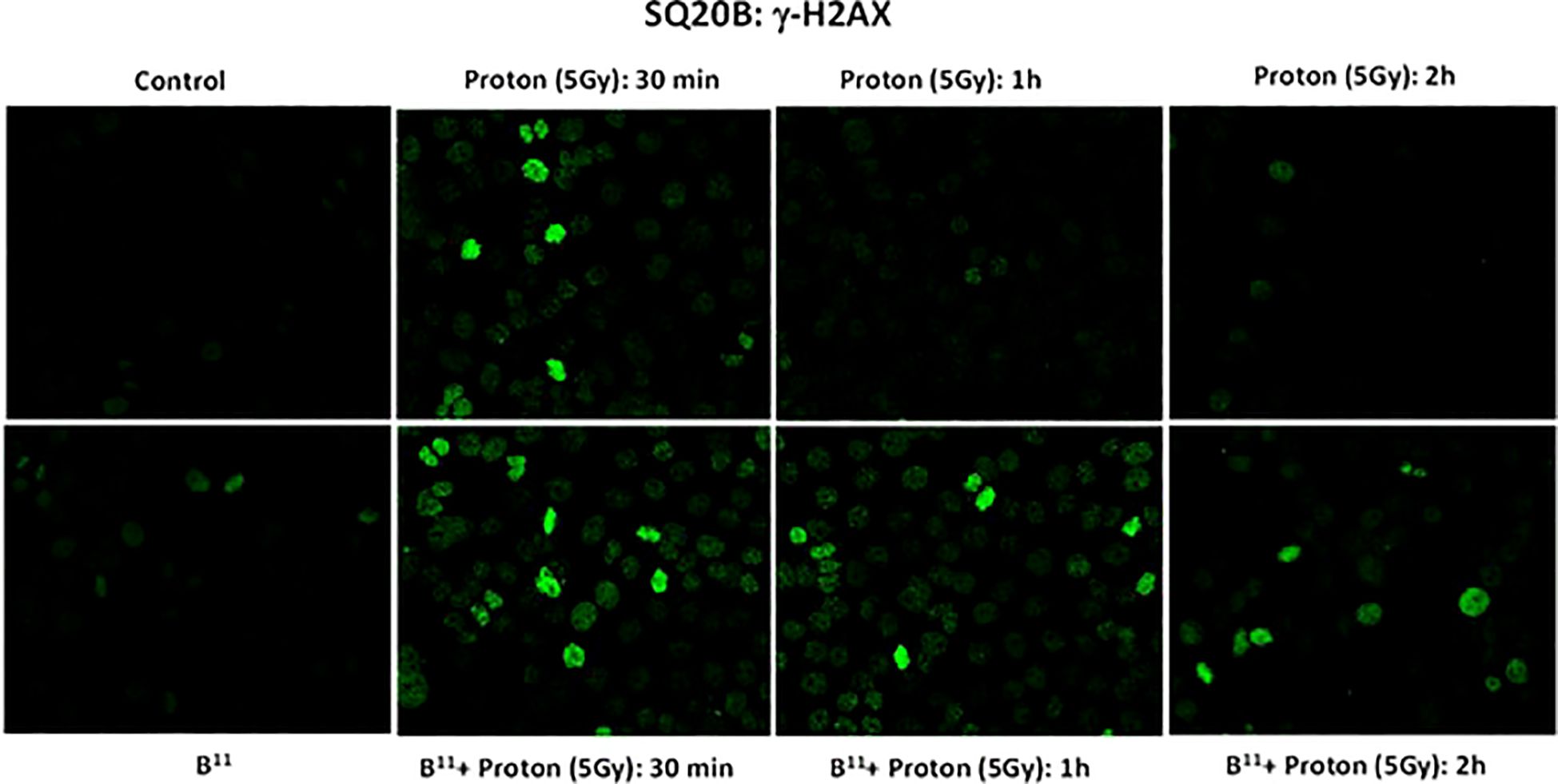

γH2AX is a highly sensitive molecular marker for detecting the presence of DNA double strand breaks and the subsequent repair of these lesions (11). To investigate whether the observed reduction in cell survival in the presence of BSH11 may be the result of a possible change in the DNA DSB pattern, potentially attributable to proton-boron capture interaction, we irradiated the SQ-20B cells with a single fraction, proton dose of 5 Gy, both with and without BSH. We conducted γH2AX analyses on the irradiated cells up to two hours post irradiation.

As shown in Figures 5, the number of foci per cell was significantly higher in BSH11 treated SQ-20B cells and persisted longer following exposure to proton irradiation (5Gy) compared to irradiated cells without BSH11 treatment (all P < 0.001).

Figure 5. γH2AX foci formation for SQ-20B cells post irradiation at 30 mins, 1 hr and 2 hr time intervals.

We further evaluated the kinetics of the repair processes by assessing foci formation at various time points, ranging from 0 hours to 24 hours, across three different fields. Each field contained an average of 50 to 100 cells, which were analyzed to determine the number of foci formed. Figure 6 shows the foci numbers peaking at 30 minutes and then decreasing over a 6-hour interval. The proton + BSH11 treated cells demonstrate a slower recovery process.

Figure 6. Analysis of γH2AX foci in SQ-20B (B) cells. Following treatment at various time points, the number of cells with foci formation was counted in three different fields. Each field contained as average 50–100 cells, which were examined to determine the number of foci formations. The 0-hour samples were treated with BSH11 only or subjected to sham irradiation. Error bars represent the standard error, and the percentage of focus-positive cells (cells containing at least 10 foci) is plotted. The histogram was created using the average number of foci in five cells within each field at different time points.

The difference in the number of foci per cell in BSH11 treated cells after radiation—compared to cells without BSH11 treatment—suggests that nearly all double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by proton radiation were repaired within 24 hours in SQ-20B cells. In contrast, treatment with BSH11 altered this response in two important ways: it increased the number of breaks at the same radiation dose and slowed their repair.

Discussion

Investigations of the effectiveness of proton-boron interaction have produced inconsistent results, ranging from radiation killing enhancement to no apparent effects (8, 12–17). Our experiments comparing two different cancer cell lines, one radioresistant and the other sensitive, reveal a small sensitization of the radiation resistant cells, but not of the radiation sensitive cells. As illustrated in Figure 2, the addition of BSH11 to the SQ-20B cells led to statistically significant reduction in survival across all dose levels except at the lowest dose of 1 Gy. For the MCF-7 cells, although the survival appears to be lower in the presence of BSH11 at all dose levels, the reductions are not statistically significant.

We interpret these observations to support a radiation sensitizing effect of BSH11 on radiation resistant cells and suggest that the alpha particles released in the p-11B interaction may contribute to the observed increase in cell killing of the SQ-20B cells. This interpretation is consistent with the observations of high-LET radiation overcoming radiation resistance. For the more radiation sensitive MCF-7 cells, sensitization was observed (Figure 2) but did not reach statistical significance in our experiments. Nonetheless, the sensitization effect on radiation resistant cell lines is the focus of this research.

In a therapeutic proton system, neutrons are also generated due to scattering interactions with various atoms along the beam path. For the Mevion S250i proton system, the neutron contamination in the primary beam is less than 0.1% (18). Despite this low neutron flux, it can still damage certain electronics in the treatment room, potentially including cells in the petri dish used for experiments. Recent Monte Carlo simulations by other investigators have estimated the presence of high energy and thermal neutrons in proton irradiated materials, including cell medium (19, 20) and found a thermal neutron flux on the order of 108/cm2/GyE and potential radiation sensitization due to BNCT effects by irradiating cells of various cell lines treated with BPA (19). A small sensitization was reported at BPA concentration of 80 ppm which was attributed to the BNCT effect (19), suggesting the possibility of thermal neutron contribution in PBCT due to the 20% 10B contained in BSH11. In this research we investigated the potential role of 10B by irradiating cells treated with BSH10 which contains over 99.97% 10B with no 11B and found no sensitization and thus ruled out the BNCT effects due to effects of possible thermal neutrons under our experimental conditions.

The results obtained in the p-BSH11, p-BSH10 and γ-BSH11 experiments support the interpretation that the reduced cell survival in the p-BSH11 experiment was likely due to the interaction between proton and 11B which produces three alpha particles. These alpha particles are lethal in cell killing when traversing cells and may induce additional bystander cell killing effects (21, 22).

It is interesting to observe that BSH11 induced a statistically significant survival reduction in the radiation resistant SQ-20B cells but not the radiation sensitive MCF-7 cells. Further experiments will be needed to assess the effects of higher concentrations.

Conclusions

The experimental data on cell survival that we present in this report for SQ-20B and MCF-7 cells, following proton and photon irradiation in the presence of BSH, demonstrate a small but statistically significant increase in cell death in the radiation resistant SQ-20B cells but not the radiation sensitive MCF-7 cells. Our findings are less robust but qualitatively support Cirrone’s report of enhanced cell kill by protons in the presence of 11B. This enhancement can be attributed to the boron-proton interaction under our experimental conditions. The potential clinical relevance may require further studies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

DP: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation. MJ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Visualization. AV: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. WP: Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis. AD: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Amrit Kaphle for assistance in statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Goitein M, Lomax AJ, and Pedroni ES. Treating cancer with protons. Phys Today. (2002) 55:45–50. doi: 10.1063/1.1522215

2. Kjellberg R, Sweet W, Preston W, and Koehler A. The Bragg peak of a proton beam in intracranial therapy of tumors. Trans Am Neurological Assoc (US). (1962) 87:216–8.

3. Schuemann J, Berbeco R, Chithrani DB, Cho SH, Kumar R, McMahon SJ, et al. Roadmap to clinical use of gold nanoparticles for radiation sensitization. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Physics. (2016) 94:189–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.09.032

4. Waissi W, Nicol A, Jung M, Rousseau M, Jarnet D, Noel G, et al. Radiosensitizing pancreatic cancer with PARP inhibitor and gemcitabine: an in vivo and a whole-transcriptome analysis after proton or photon irradiation. Cancers. (2021) 13:527. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030527

5. Ganjeh ZA and Eslami-Kalantari M. Investigation of proton–boron capture therapy vs. Proton therapy. Nucl Instruments Methods Phys Res Section A: Accelerators Spectrometers Detectors Associated Equipment. (2020) 977:164340. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2020.164340

6. Sgouros G. Alpha-particles for targeted therapy. Advanced Drug delivery Rev. (2008) 60:1402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.007

7. Brooks A, Newton G, Shyr L-J, Seiler F, and Scott B. The combined effects of α-particles and X-rays on cell killing and micronuclei induction in lung epithelial cells. Int J Radiat Biol. (1990) 58:799–811. doi: 10.1080/09553009014552181

8. Cirrone G, Manti L, Margarone D, Petringa G, Giuffrida L, Minopoli A, et al. First experimental proof of Proton Boron Capture Therapy (PBCT) to enhance protontherapy effectiveness. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19258-5

9. Mazzone A, Finocchiaro P, Meo SL, and Colonna N. On the (un) effectiveness of proton boron capture in proton therapy. Eur Phys J Plus. (2019) 134:361. doi: 10.1140/epjp/i2019-12725-8

10. Shahmohammadi Beni M, Islam MR, Kim KM, Krstic D, Nikezic D, Yu KN, et al. On the effectiveness of proton boron fusion therapy (PBFT) at cellular level. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:18098. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23077-0

11. Mah L, El-Osta A, and Karagiannis T. γH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia. (2010) 24:679–86. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.6

12. Bláha P, Feoli C, Agosteo S, Calvaruso M, Cammarata FP, Catalano R, et al. The proton-boron reaction increases the radiobiological effectiveness of clinical low-and high-energy proton beams: novel experimental evidence and perspectives. Front Oncol. (2021) 11. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.682647

13. Manandhar M, Bright SJ, Flint DB, Martinus DK, KolaChina RV, Ben Kacem M, et al. Effect of boron compounds on the biological effectiveness of proton therapy. Med physics. (2022) 49:6098–109. doi: 10.1002/mp.15824

14. Jelínek Michaelidesová A, Kundrát P, Zahradníček O, Danilová I, Pachnerová Brabcová K, Vachelová J, et al. First independent validation of the proton-boron capture therapy concept. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:19264. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-69370-y

15. Belchior A, Alves BC, Mendes E, Megre F, Alves LC, Santos P, et al. Unravelling physical and radiobiological effects of proton boron fusion reaction with anionic metallacarboranes ([o-COSAN]-) in breast cancer cells. EJNMMI Res. (2025) 15:13. doi: 10.1186/s13550-025-01199-6

16. Cammarata FP, Torrisi F, Vicario N, Bravatà V, Stefano A, Salvatorelli L, et al. Proton boron capture therapy (PBCT) induces cell death and mitophagy in a heterotopic glioblastoma model. Commun Biol. (2023) 6:388. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04770-w

17. Ricciardi V, Bláha P, Buompane R, Crescente G, Cuttone G, Gialanella L, et al. A new low-energy proton irradiation facility to unveil the mechanistic basis of the proton-boron capture therapy approach. Appl Sci. (2021) 11:11986. doi: 10.3390/app112411986

18. Prusator MT, Ahmad S, and Chen Y. Shielding verification and neutron dose evaluation of the Mevion S250 proton therapy unit. J Appl Clin Med physics. (2018) 19:305–10. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12256

19. Shiba S, Shimo T, Yamanaka M, Yagihashi T, Sakai M, Ohno T, et al. Increased cell killing effect in neutron capture enhanced proton beam therapy. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:28484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-79045-3

20. Safavi-Naeini M, Chacon A, Guatelli S, Franklin DR, Bambery K, Gregoire M-C, et al. Opportunistic dose amplification for proton and carbon ion therapy via capture of internally generated thermal neutrons. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:16257. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34643-w

21. Deshpande A, Goodwin E, Bailey S, Marrone B, and Lehnert B. thE. Alpha-particle-induced sister chromatid exchange in normal human lung fibroblasts: evidence for an extranuclear target. Radiat Res. (1996) 145:260–7. doi: 10.2307/3578980

Keywords: boron, proton, irradiation, cell survival, γH2AX, SQ-20B, MCF-7, BSH

Citation: Pang D, Jung M, Velena A, Parke W and Dritschilo A (2025) Proton-boron capture interaction enhances killing of radiation resistant cancer cells. Front. Oncol. 15:1720143. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1720143

Received: 07 October 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025; Revised: 21 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Abdul K. Parchur, University of Maryland Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Teresa Pinheiro, University of Lisbon, PortugalLorenzo Manti, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Pang, Jung, Velena, Parke and Dritschilo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dalong Pang, cGFuZ2RAZ2VvcmdldG93bi5lZHU=

Dalong Pang

Dalong Pang Mira Jung

Mira Jung Alfredo Velena1

Alfredo Velena1 Anatoly Dritschilo

Anatoly Dritschilo