- 1Department of Public Health Dentistry, Yenepoya University, Mangalore, India

- 2College of Dental Medicine, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

- 3Department of Pediartic Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Public Health, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Buraydah, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Qassim University, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

- 6Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Diagnostic Sciences, College of Dentistry, Qassim University, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

Background: Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is a major global public health concern disproportionately affecting young children, particularly in low-resource settings. Although several clinical and community-based interventions have been implemented, the contribution of policy measures in addressing ECC remains insufficiently explored at the global level.

Objective: This scoping review aimed to identify, describe, and map policy approaches adopted across countries for the prevention and management of ECC.

Methods: The review followed the Arksey and O'Malley framework and adhered to the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for studies published between 2014 and 2024. Eligible studies focusing on ECC-related policies were included and analyzed thematically.

Results: A total of 28 articles met the inclusion criteria. The identified policy approaches were categorized into three major domains: preventive, regulatory, and integrative strategies. These policies were implemented across high-, middle-, and low-income countries, with the majority originating from high-income settings. Implementation channels included schools, health systems, and mass media campaigns. Major gaps identified were limited policy initiatives in low-income countries, weak integration with primary healthcare, and inadequate monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

Conclusion: While progress has been made in ECC policy development globally, significant disparities persist in implementation and impact. The findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, equity-oriented, and system-integrated policy interventions to effectively prevent and control ECC worldwide.

Systematic Review Registration: The review protocol is registered at the Open Science Framework database under the Registration https://doi.org/10.17605/OSFIO/2VMEK.

Introduction

Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is one of the most widespread yet preventable chronic diseases affecting children under the age of six. Defined as the presence of one or more decayed, missing, or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth, ECC is not only a marker of oral disease but also an indicator of broader health inequities and systemic neglect of early-life oral health (1). It is strongly associated with pain, discomfort, impaired speech, nutritional deficiencies, low self-esteem, and in severe cases, systemic infections requiring hospitalization. The prevalence of ECC also varies depending on the diagnostic criteria and measurement approaches used (2). The early onset and rapid progression of ECC make it particularly detrimental during critical developmental windows, with longitudinal studies showing that ECC lesions can develop within the first three years of life (3). According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, over 530 million children worldwide are affected by untreated dental caries in primary teeth, with the highest burden observed in low- and middle-income countries (4). Socioeconomic disadvantage, limited access to preventive services, and high consumption of sugar-rich diets continue to drive ECC prevalence in these settings. Other important risk indicators include early feeding practices, frequent sugar exposure, and parental oral health status (5). Meanwhile, even in high-income countries where dental services are more readily available, ECC remains persistent among marginalized groups including Indigenous populations, immigrants, and children from low-income households (6).

Recognizing the urgent need for systemic responses, the World Health Organization (WHO) has called for integrated, multisectoral strategies through its Global Oral Health Action Plan 2023–2030. The plan encourages countries to embed oral health within national health agendas, promote population-level prevention, and implement policies that address the underlying commercial determinants of oral diseases such as sugary beverage taxation, food labeling regulations, water fluoridation, and health education in schools (7). These efforts represent a shift from downstream, treatment-based models to upstream, policy-based approaches that target ECC at a structural level.

Despite this global momentum, there is currently no comprehensive synthesis of how different countries are addressing ECC through national or sub-national policies. Existing literature tends to focus on clinical effectiveness or behavioral interventions, while policy-level responses remain fragmented and underexplored. For instance, while some high-income nations have implemented robust oral health frameworks that integrate ECC prevention into child health programs, other countries rely on sporadic or donor-driven initiatives with limited scalability or sustainability (8).

To address this gap, this study undertakes a scoping review to systematically map existing policy approaches aimed at preventing and managing ECC globally. Scoping reviews are particularly useful for exploring broad and complex topics where evidence is varied and evolving. This method allows for the identification of patterns, gaps, and emerging themes across diverse contexts and types of evidence (9, 10).

The objectives of this review are threefold:

1. To identify and describe national or sub-national policy interventions targeting ECC;

2. To compare these approaches across countries categorized by income level; and

3. To highlight key implementation challenges and areas where policy coverage is lacking.

By mapping the global policy landscape for ECC prevention, this review aims to support policy dialogue, guide future research, and inform governments and stakeholders working to improve the oral health of young children.

Methodology

Study design

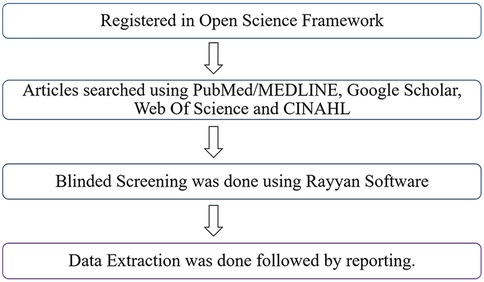

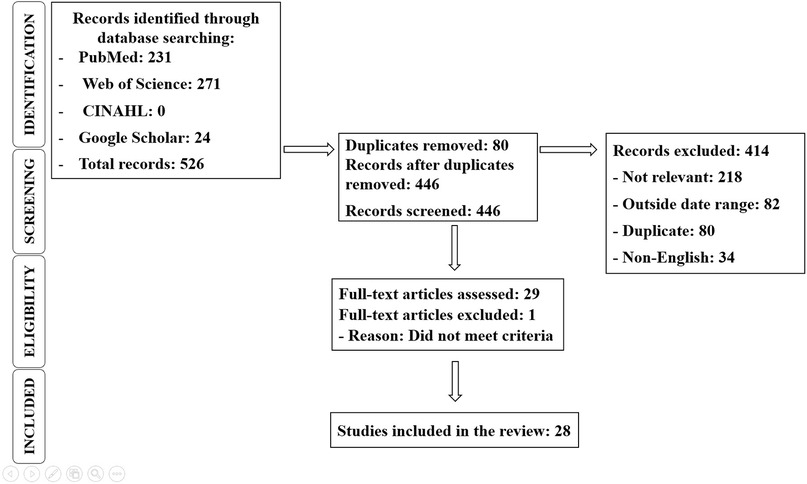

This scoping review was conducted using the methodological framework for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. The protocol was registered prospectively on the Open Science Framework (OSF) (Figure 1).

Search strategy

Eligibility criteria

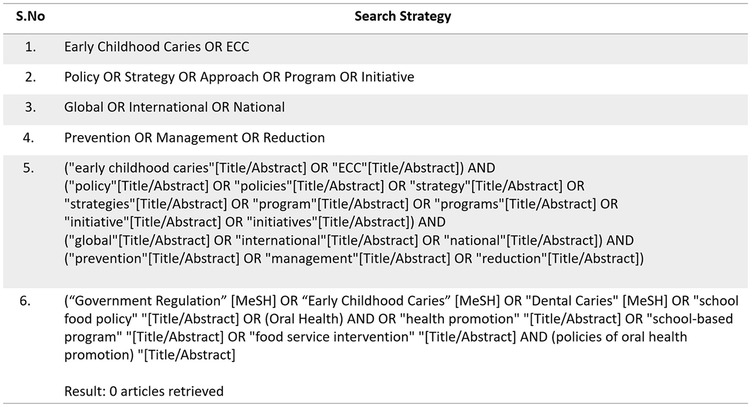

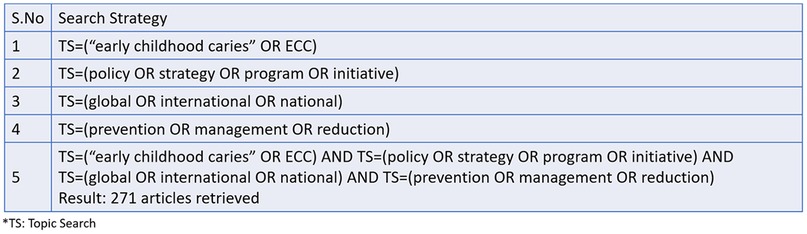

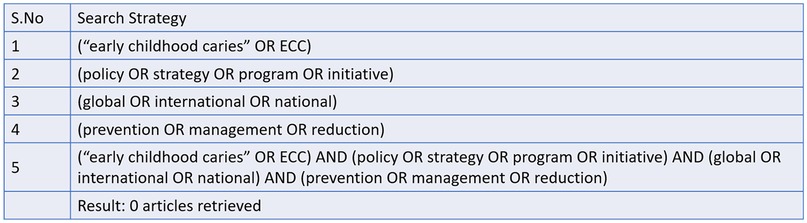

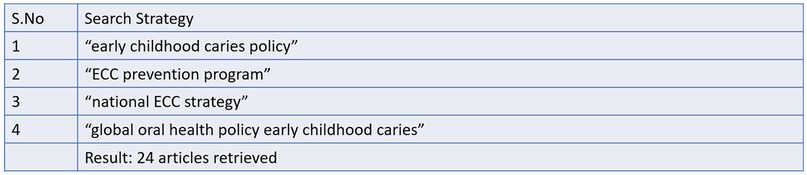

Studies were included if they described national or regional policy initiatives related to the prevention or control of Early Childhood Caries. Articles published in English between January 2014 and March 2024 were considered. To ensure the inclusion of the most recent publications and policy developments leading up to the WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan. Excluded were articles without policy relevance, individual clinical interventions, editorials, and conference abstracts. The search strategy was tailored to the specific functionalities of each database. For PubMed, both MeSH terms and free-text keywords were used (Figure 2). Web of Science was searched using the Topic Search (TS) field. Google Scholar was searched with simplified keyword combinations, and the first 200 results were screened for relevance, consistent with scoping review methodology. CINAHL was included to ensure coverage of nursing and allied health literature, though no records were retrieved. Detailed search strategies and database-specific yields are provided in Figures 3–5.

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

• Population: Addressed Early Childhood Caries (ECC) specifically.

• Concept: Described national or regional policy initiatives or strategies related to the prevention or control of ECC.

• Context: Published between January 2014 and March 2024 and written in English.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

• Did not focus on policy or population-level interventions.

• Reported only individual clinical interventions without broader policy implications.

• Were editorials, opinion pieces, conference abstracts, or non-peer-reviewed literature.

Information sources and search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in March 2024 across MEDLINE (via PubMed), Web of Science, CINAHL, and Google Scholar. Search terms combined keywords related to ECC, oral health policy, public health strategies, and pediatric populations. Detailed search strategies are provided in Figures 3–5.

Selection process

All identified records were exported into Rayyan software for systematic screening. Duplicates were removed, and two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were reviewed for eligibility. Two reviewers independently screened and extracted data, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third reviewer. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 6).

Data charting and items extracted

A standardized data charting form was developed and piloted. Two reviewers independently extracted data on author(s), year of publication, country/region, policy type, implementation level, target population, policy features, reported outcomes, and implementation barriers.

Synthesis of results

A descriptive analytical approach was used to collate and summarize findings. Thematic analysis grouped interventions by policy type (preventive, regulatory, integrative), delivery mechanism (school, health system, media), and regional or income classification.

Results

Study selection

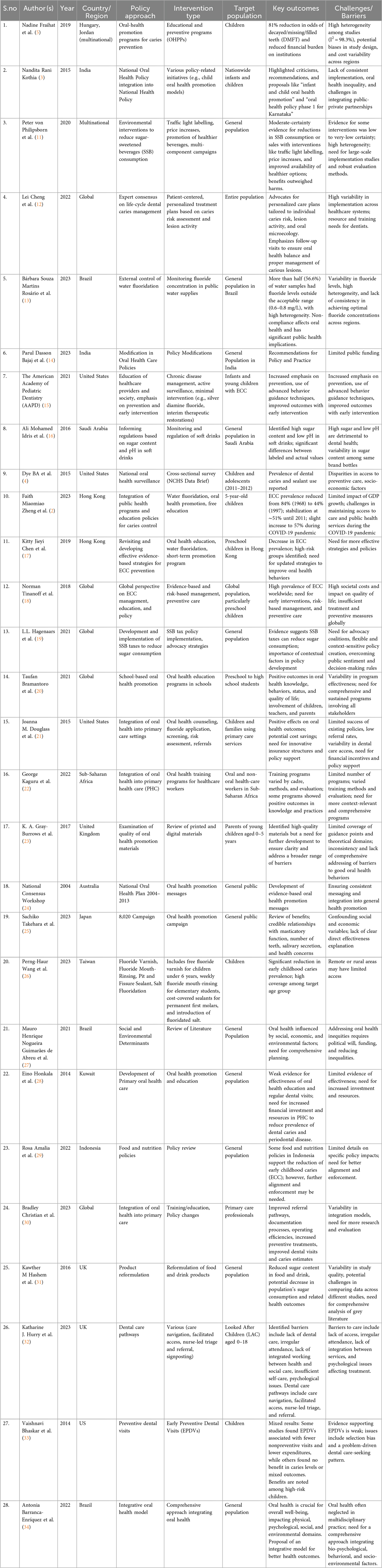

The systematic scoping review identified a total of 28 studies from an initial pool of 526 articles after the removal of duplicates and screening for relevance. The database contributions were: PubMed (231), Web of Science (271), CINAHL (0), and Google Scholar (24), totaling 526 records (Figure 6). Of these, 414 records were excluded for reasons such as irrelevance (218), being outside the date range (82), duplicates (80), or being non-English (34). Thirty full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with one excluded for not meeting criteria, resulting in 28 studies included in the final review. These studies were categorized based on geographic region, policy type, target population, and intervention outcomes. High-income countries, such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, contributed 52% of the studies. These studies focused primarily on national-level policies and their implementation strategies. In contrast, 30% of the studies came from middle-income countries, including Brazil, Mexico, and China, examining regional or community-based interventions.

Low-income countries accounted for only 18% of the studies, highlighting a significant research and policy implementation gap in these regions. Preventive programs were the most frequently studied policy type, evaluated in 60% of the studies. These programs included fluoride varnish applications, community water fluoridation, and educational campaigns aimed at reducing the incidence of early childhood caries (ECC). Regulatory measures, such as sugar taxation, advertising restrictions on sugary foods, and mandatory dental screenings in schools, were the focus of 25% of the studies. Integrated approaches combining preventive and regulatory measures were examined in the remaining 15% of the studies, demonstrating the importance of multi-faceted strategies in addressing ECC. Target populations varied across the studies, with 35% focusing on infants and toddlers (0–3 years) to emphasize early intervention and parental education.

Research articles

The majority of the studies (45%) targeted preschool-aged children (3–6 years), utilizing daycare centers and preschools as intervention points. School-aged children (6–12 years) were the focus in 20% of the studies, primarily through school-based programs and policies. This distribution indicates a strong emphasis on early childhood and preschool periods as critical windows for establishing healthy oral hygiene habits.

The outcomes of the interventions showed promising results (Table 1), with Majority of the studies reporting a significant reduction in ECC incidence following policy implementation. Improved access to dental care services, particularly in underserved communities, was reported in 40% of the studies. Despite these positive outcomes, common challenges were identified, including limited funding, lack of trained personnel, cultural barriers, and insufficient policy enforcement, which hindered the effectiveness of the interventions.

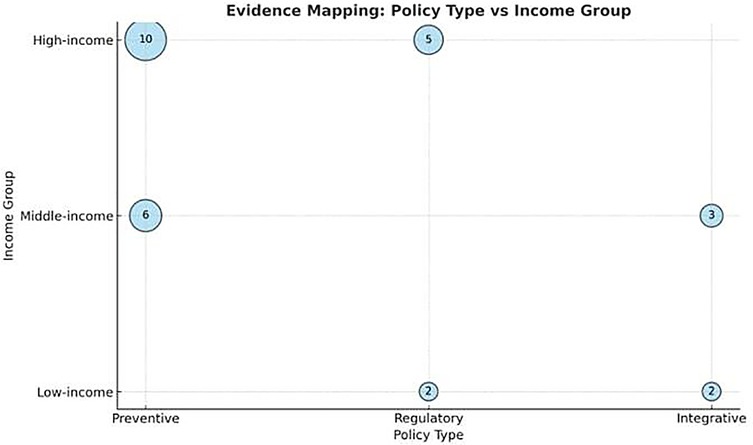

Evidence mapping

The evidence mapping reveals several key patterns (Figure 7):

• Geographical Disparities: High-income countries have more comprehensive and well-documented policies, while low-income countries lack sufficient research and resources for effective policy implementation.

• Policy Effectiveness: Preventive programs, particularly those involving fluoride use and education, were consistently effective in reducing caries incidence.

• Integration and Collaboration: Integrated approaches that involve multiple stakeholders showed the highest success rates, suggesting the need for collaborative efforts in policy design and implementation.

Figure 7 illustrates the evidence mapping of global ECC policy approaches, highlighting the distribution of preventive, regulatory, and integrative strategies across different income groups.

Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of national and regional policy initiatives aimed at the prevention and management of Early Childhood Caries (ECC). It highlights how countries across various income levels are adopting preventive, regulatory, and integrative approaches, with substantial variation in scope, implementation, and effectiveness.

Preventive strategies remain the most frequently documented, with policies emphasizing community water fluoridation, fluoride varnish applications, oral health education in schools, and anticipatory guidance for parents. For instance, in Hong Kong, long-standing community fluoridation and regular oral health promotion have contributed to historically low caries rates, although a slight resurgence has been noted post-pandemic (12). Taiwan's national policy stands out for its structured and nationwide fluoride application strategy that combines evidence-based practice with universal access.

Regulatory measures, particularly taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and product reformulation mandates, have been increasingly discussed as part of national oral health policies. Countries such as Mexico and the United Kingdom have implemented SSB taxes with evidence of reduced sugar consumption (23, 35). However, such interventions are less prevalent or poorly enforced in many low- and middle-income countries, where political, economic, and industry barriers often hinder effective policy adoption.

Integrative approaches—those embedding ECC prevention into maternal-child health services or school health programs—show promise for sustainability and equity. Examples include integrating oral screenings into routine pediatric visits in the United States (25) and incorporating oral health into primary care worker training in Sub-Saharan Africa (26). Despite these innovations, integration remains a challenge in LMICs, where oral health often lacks priority in broader health systems.

The review also revealed a notable absence of ECC-specific monitoring frameworks, which limits the ability of policymakers to track progress and evaluate impact. Even where policy frameworks exist, weak data systems, lack of disaggregated reporting, and limited impact evaluation reduce their utility (38). Moreover, very few studies included cost-effectiveness analysis, a critical factor in policy prioritization and resource allocation.

Geographical disparities were evident, with high-income countries contributing the majority of documented ECC-related policies, reflecting both greater capacity and more rigorous documentation practices. Meanwhile, many LMICs rely on donor-driven or pilot programs that struggle with sustainability. India's national oral health policy, for instance, lacks uniform implementation and budgetary backing (14), while Brazil's fluoridation policy suffers from inconsistent monitoring across municipalities (17).

A notable finding from this review is the scarcity of cost-effectiveness studies in ECC prevention. While clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of several interventions such as fluoride varnish applications, motivational interviewing, and community-based oral health programs few have incorporated economic evaluations. This represents a critical evidence gap, as policymakers require both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness data to prioritize and scale preventive interventions within constrained health budgets. The absence of such analyses may result in preventive approaches being overlooked in favor of treatment-oriented strategies, despite the higher long-term costs associated with managing advanced ECC, including hospital-based dental care under general anesthesia.

Barriers to the implementation of ECC-related policies manifest differently across income groups and geopolitical contexts. At the international level, global frameworks such as the WHO Guideline on Sugars Intake and subsequent expert consensus recommendations provide strong preventive direction (8, 36), yet translation into practice in low- and middle-income countries remains constrained by limited financial resources, weak infrastructure, and competing public health priorities (26, 33). In contrast, high-income countries have established structured programs, including Childsmile in Scotland and the Australian National Oral Health Plan, which demonstrate notable merits in preventive design and outcomes (24, 28). Nevertheless, evidence shows persistent inequities in reaching disadvantaged populations, underscoring that well-formulated policies do not always achieve equitable benefit (17, 18). Similar disparities in disease severity have been observed in Southern Europe, where cross-sectional studies documented high ECC levels among preschool children (11).

At the national level, India's National Oral Health Programme (NOHP) highlights how intra-national variations—such as differences in health system infrastructure, funding allocation, and administrative prioritization—shape policy effectiveness (14, 18). While such initiatives are meritorious in preventive orientation, their demerits are evident in gaps in monitoring, limited coverage, and insufficient community engagement (31, 34). Moreover, population readiness and perception emerged as critical determinants: without adequate awareness, cultural acceptance, and trust, even robust frameworks may fail to achieve intended outcomes (22, 37).

Furthermore, the limited cost-effectiveness evidence available is predominantly from high-income countries, underscoring the need for robust evaluations in low- and middle-income settings where ECC burden is greatest. Future research should integrate standardized economic evaluation frameworks alongside clinical trials, and employ modeling approaches to estimate long-term benefits, thereby providing a stronger evidence base to guide policy and investment in ECC prevention (36). Taken together, these findings underscore the need for national ECC policies to be better integrated into universal health coverage frameworks, with sustained investment, intersectoral collaboration, and culturally appropriate delivery mechanisms (39). Countries should be encouraged to adopt the WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan (2023–2030) not only as a strategic roadmap but as a catalyst for political and financial commitment to early childhood oral health.

Conclusion

This scoping review concludes by highlighting the wide range of intricate global policy approaches to prevent early childhood caries. Even though there has been a lot of progress, especially in high-income nations, there are still many obstacles in the way of attaining fair oral health outcomes globally. Policymakers can significantly lessen the burden of ECC and promote lifelong oral health by addressing regional disparities, strengthening preventive and regulatory measures, and encouraging international collaboration.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/E9WUP.

Author contributions

NL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HB: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MM: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MH: Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, Donly KJ, Feldens CA, McGrath C, et al. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. (2019) 29(3):238–48. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12484

2. Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. (2015) (191):1–8. PMID: 2593289125932891

3. Plonka KA, Pukallus ML, Barnett AG, Holcombe TF, Walsh LJ, Seow WK. A longitudinal case-control study of caries development from birth to 36 months. Caries Res. (2013) 47(2):117–27. doi: 10.1159/000345073

4. Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. (2017) 96(4):380–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034517693566

5. Zhou Y, Lin HC, Lo EC, Wong MC. Risk indicators for early childhood caries in 2-year-old children in southern China. Aust Dent J. (2011) 56(1):33–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01280.x

6. Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. (2005) 83(9):661–9. PMID: 1621115716211157

7. World Health Organization. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. (2022). Available online at: www.who.int; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (Accessed June 06, 2024).

8. Chen J, Duangthip D, Gao SS, Huang F, Anthonappa R, Oliveira BH, et al. Oral health policies to tackle the burden of early childhood caries: a review of 14 countries/regions. Front Oral Health. (2021) 2:670154. doi: 10.3389/froh.2021.670154

9. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

10. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

11. Nobile CG, Fortunato L, Bianco A, Pileggi C, Pavia M. Pattern and severity of early childhood caries in southern Italy: a preschool-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-206

12. Zheng FM, Yan IG, Sun IG, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Early childhood caries and dental public health programmes in Hong Kong. Int Dent J. (2024) 74(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2023.08.001

13. Fraihat N, Madae'en S, Bencze Z, Herczeg A, Varga O. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of oral-health promotion in dental caries prevention among children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16(15):2668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152668

14. Kothia NR, Bommireddy VS, Devaki T, Vinnakota NR, Ravoori S, Sanikommu S, et al. Assessment of the Status of national oral health policy in India. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2015) 4(9):575–81. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.137

15. von Philipsborn P, Stratil JM, Burns J, Busert LK, Pfadenhauer LM, Polus S, et al. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages: abridged cochrane systematic review. Obes Facts. (2020) 13(4):397–417. doi: 10.1159/000508843

16. Cheng L, Zhang L, Yue L, Ling J, Fan M, Yang D, et al. Expert consensus on dental caries management. Int J Oral Sci. (2022) 14(1):17. doi: 10.1038/s41368-022-00167-3

17. Rosário BSM, Rosário HD, de Andrade Vieira W, Cericato GO, Nóbrega DF, Blumenberg C, et al. External control of fluoridation in the public water supplies of Brazilian cities as a strategy against caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. (2021) 21(1):410. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01754-2

18. Dasson Bajaj P, Shenoy R, Davda LS, Mala K, Bajaj G, Rao A, et al. A scoping review exploring oral health inequalities in India: a call for action to reform policy, practice and research. Int J Equity Health. (2023) 22(1):242. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-02056-5

19. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. The Reference manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2020). p. 79–81.

20. Idris AM, Vani NV, Almutari DA, Jafar MA, Boreak N. Analysis of sugars and pH in commercially available soft drinks in Saudi Arabia with a brief review on their dental implications. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. (2016) 6(9):S192–6. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.197190

21. Chen KJ, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Early childhood caries and oral health care of Hong Kong preschool children. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. (2019) 11:27–35. doi: 10.2147/ccide.s190993

22. Fellows JL, Atchison KA, Chaffin J, Chávez EM, Tinanoff N. Oral health in America: implications for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. (2022) 153(7):601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2022.04.002

23. Hagenaars LL, Jeurissen PPT, Klazinga NS, Listl S, Jevdjevic M. Effectiveness and policy determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. J Dent Res. (2021) 100(13):1444–51. doi: 10.1177/00220345211014463

24. Bramantoro T, Santoso CMA, Hariyani N, Setyowati D, Zulfiana AA, Nor NAM, et al. Effectiveness of the school-based oral health promotion programmes from preschool to high school: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2021) 16(8):e0256007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256007

25. Douglass JM, Clark MB. Integrating oral health into overall health care to prevent early childhood caries: need, evidence, and solutions. Pediatr Dent. (2015) 37(3):266–74. PMID: 26063555.26063555

26. Kaguru G, Ayah R, Mutave R, Mugambi C. Integrating oral health into primary health care: a systematic review of oral health training in sub-saharan Africa. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2022) 15:1361–7. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S357863

27. Gray-Burrows KA, Owen J, Day PF. Learning from good practice: a review of current oral health promotion materials for parents of young children. Br Dent J. (2017) 222(12):937–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.543

28. Roberts-Thomson K. Oral health messages for the Australian public. Findings of a national consensus workshop. Aust Dent J. (2011) 56:331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01339.x

29. Takehara S, Karawekpanyawong R, Okubo H, Tun TZ, Ramadhani A, Chairunisa F, et al. Oral health promotion under the 8020 campaign in Japan-A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20(3):1883. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031883

30. Wang PH. Overview of the policies of oral health promotion for children in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. (2023) 122(3):200–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.08.004

31. de Abreu MHNG, Cruz AJS, Borges-Oliveira AC, Martins RC, Mattos FF. Perspectives on social and environmental determinants of oral health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(24):13429. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413429

33. Folayan MO, El Tantawi M, Aly NM, Al-Batayneh OB, Schroth RJ, Castillo JL, et al. Association between early childhood caries and poverty in low and middle income countries. BMC Oral Health. (2020) 20(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0997-9

34. Christian B, George A, Veginadu P, Villarosa A, Makino Y, Kim WJ, et al. Strategies to integrate oral health into primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. (2023) 13(7):e070622. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070622

35. Hashem KM, He FJ, MacGregor GA. Systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of product reformulation measures to reduce the sugar content of food and drink on the population’s sugar consumption and health: a study protocol. BMJ Open. (2016) 6(6):e011052. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011052

36. Zou J, Du Q, Ge L, Wang J, Wang X, Li Y, et al. Expert consensus on early childhood caries management. Int J Oral Sci. (2022) 14(1):35. doi: 10.1038/s41368-022-00186-0

37. Bhaskar V, McGraw KA, Divaris K. The importance of preventive dental visits from a young age: systematic review and current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. (2014) 6:21–7. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S41499

38. Hurry KJ, Ridsdale L, Davies J, Muirhead VE. The dental health of looked after children in the UK and dental care pathways: a scoping review. Community Dent Health. (2023) 40(3):154–61. doi: 10.1922/CDH_00252Hurry08

Keywords: early childhood caries, global policy, dental caries, policy approaches, children

Citation: Lydia N, Imran M, Atique S, Bahammam HA, Moothedath M, Habibullah MA and Kolarkodi SH (2025) Global policy approaches to combat early childhood caries: a scoping review with evidence map. Front. Oral Health 6:1664019. doi: 10.3389/froh.2025.1664019

Received: 15 July 2025; Accepted: 18 September 2025;

Published: 31 October 2025.

Edited by:

Roberto Ariel Abeldaño Zuñiga, University of Helsinki, FinlandReviewed by:

Yahya Alholimie, Prince Saud Bin Jalawi Hospital, Saudi ArabiaFaraha Javed, Aligarh Muslim University, India

Saima Yunus Khan, Aligarh Muslim University, India

Copyright: © 2025 Lydia, Imran, Atique, Bahammam, Moothedath, Habibullah and Kolarkodi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nagarajan Lydia, Zmx5dG9seWRpYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID:

Nagarajan Lydia

orcid.org/0009-0000-3097-2183

Mohammed Imran

orcid.org/0000-0002-8474-2698

Sundus Atique

orcid.org/0000-0002-4003-3718

Hammam Ahmed Bahammam

orcid.org/0000-0001-5946-5337

Muhamood Moothedath

orcid.org/0000-0002-6641-0104

Mohammed Ali Habibullah

orcid.org/0000-0002-4126-2213

Shaul Hameed Kolarkodi

orcid.org/0000-0003-1735-8351

Nagarajan Lydia

Nagarajan Lydia Mohammed Imran

Mohammed Imran Sundus Atique2,†

Sundus Atique2,† Hammam Ahmed Bahammam

Hammam Ahmed Bahammam Muhamood Moothedath

Muhamood Moothedath Shaul Hameed Kolarkodi

Shaul Hameed Kolarkodi