Abstract

Aims: Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury markedly undermines the protective benefits of revascularization, contributing to ventricular dysfunction and mortality. Due to complex mechanisms, no efficient ways exist to prevent cardiomyocyte reperfusion damage. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) appears as a potential therapeutic intervention to alleviate myocardial I/R injury. Hence, this meta-analysis intends to elucidate the potential cellular and molecular mechanisms underpinning the beneficial impact of VNS, along with its prospective clinical implications.

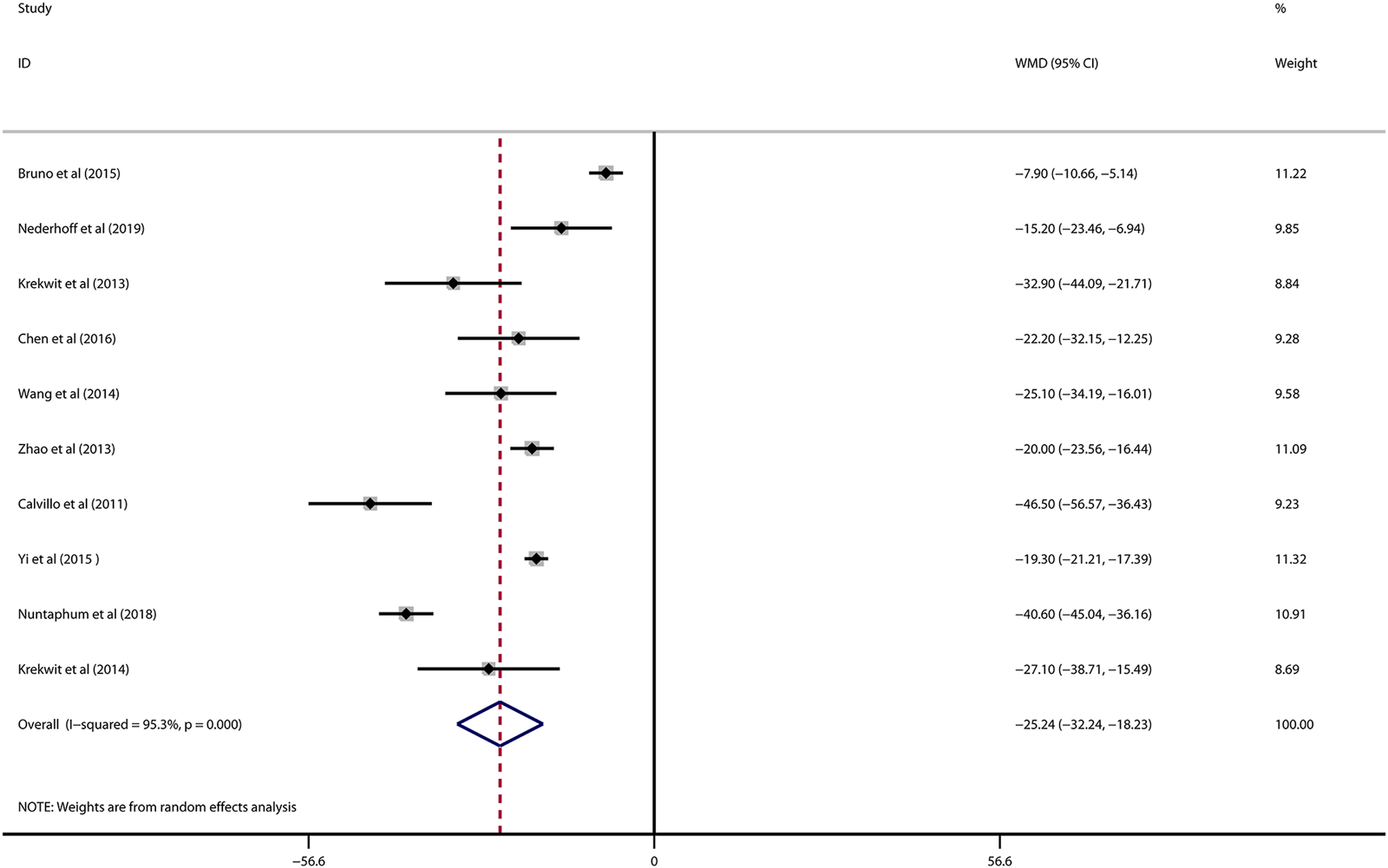

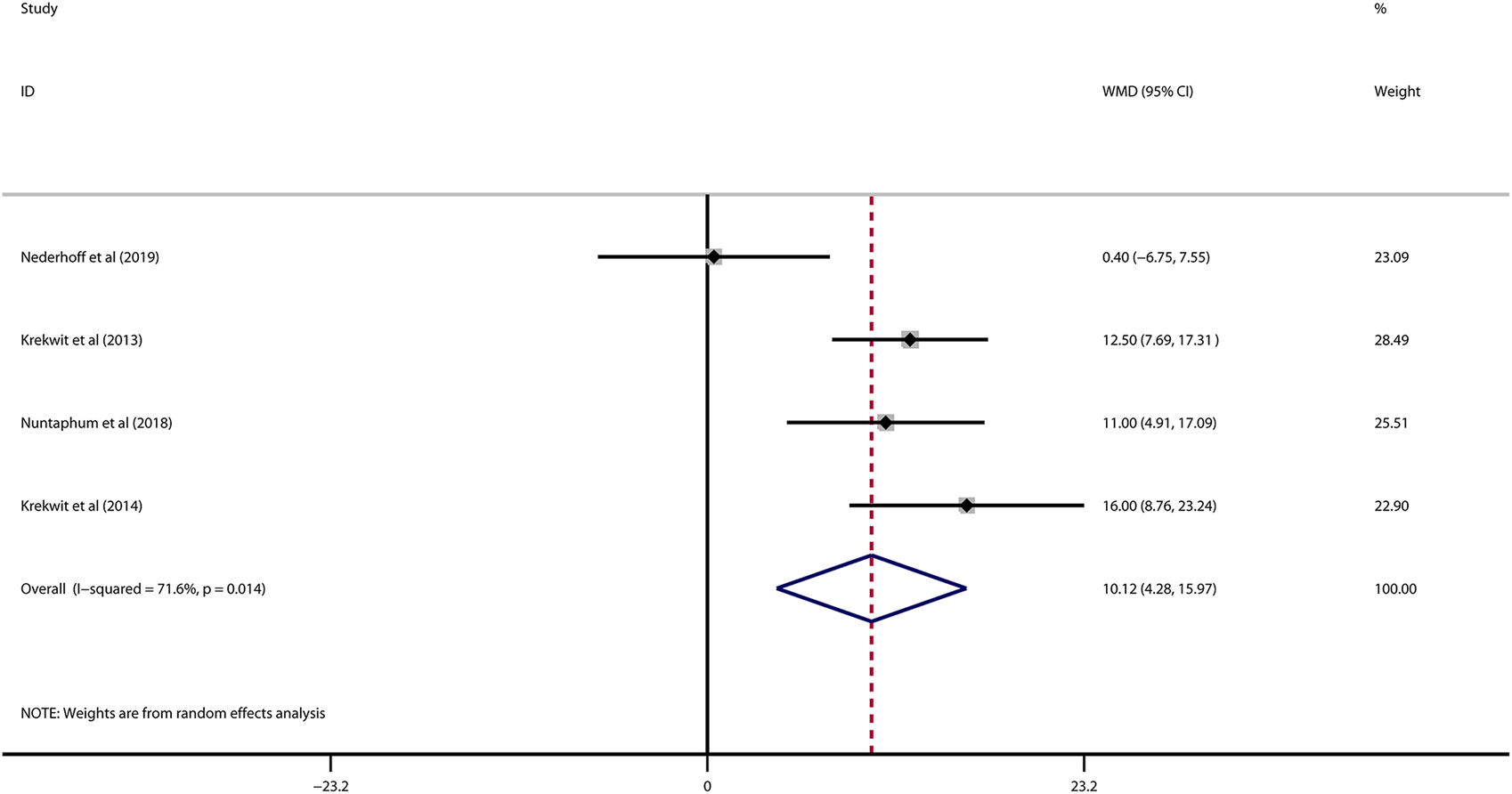

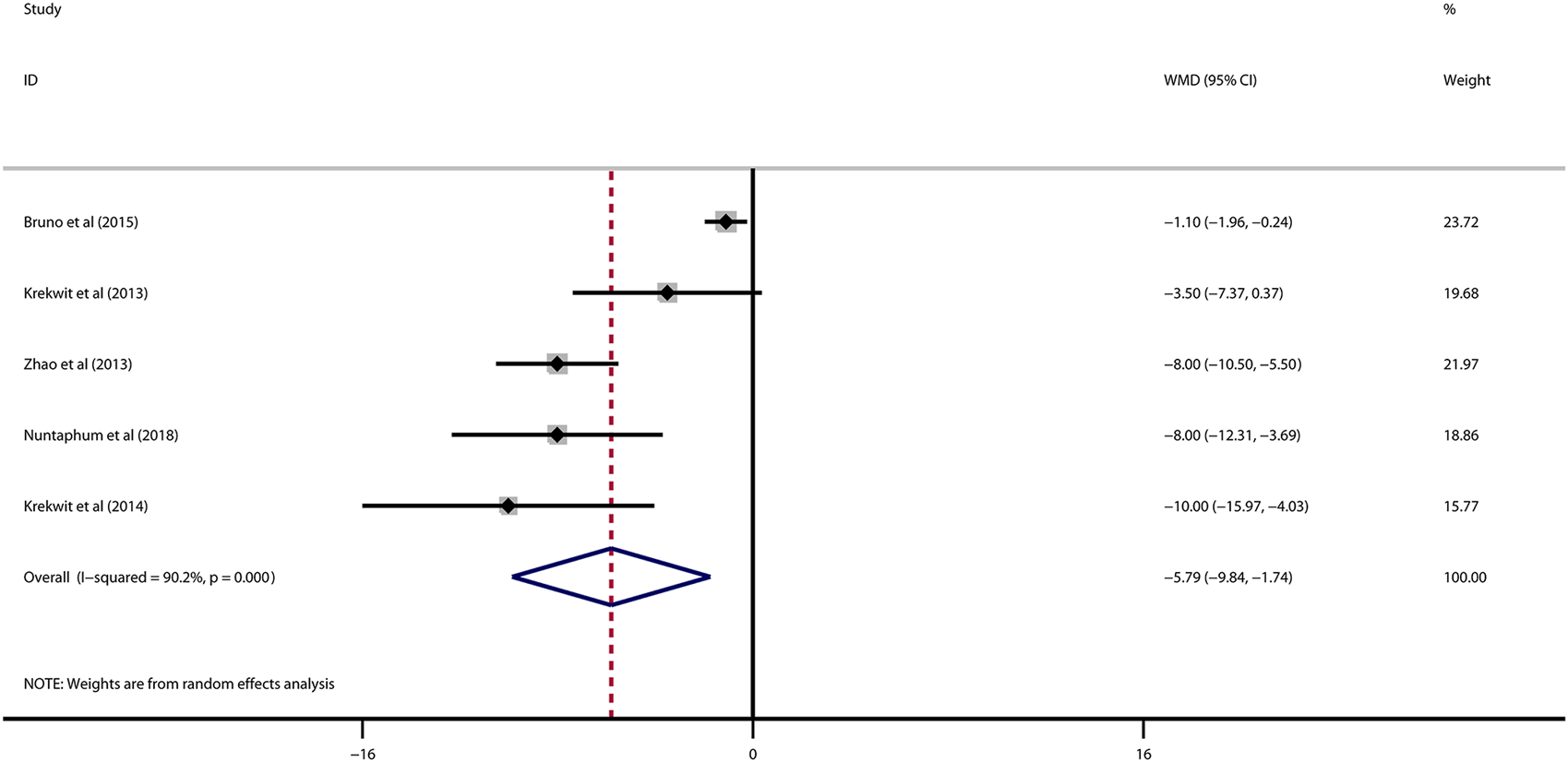

Methods and Results: A literature search of MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Database yielded 10 articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria. VNS was significantly correlated with a reduced infarct size following myocardial I/R injury [Weighed mean difference (WMD): 25.24, 95% confidence interval (CI): 32.24 to 18.23, p < 0.001] when compared to the control group. Despite high heterogeneity (I2 = 95.3%, p < 0.001), sensitivity and subgroup analyses corroborated the robust efficacy of VNS in limiting infarct expansion. Moreover, meta-regression failed to identify significant influences of pre-specified covariates (i.e., stimulation type or site, VNS duration, condition, and species) on the primary estimates. Notably, VNS considerably impeded ventricular remodeling and cardiac dysfunction, as evidenced by improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (WMD: 10.12, 95% CI: 4.28; 15.97, p = 0.001) and end-diastolic pressure (EDP) (WMD: 5.79, 95% CI: 9.84; −1.74, p = 0.005) during the reperfusion phase.

Conclusion: VNS offers a protective role against myocardial I/R injury and emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy for future clinical application.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a primary global cause of mortality and disability. Prompt and successful reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium through thrombolytic therapy or primary percutaneous coronary intervention is the most efficacious strategy to salvage ischemic myocardium, mitigate myocardial injury, and enhance clinical outcomes (Hausenloy and Yellon, 2013). However, the process of myocardial reperfusion may trigger cardiomyocyte death and exacerbate cardiac dysfunction. This paradoxical occurrence, known as myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, curtails the beneficial effects of revascularization strategies (González-Montero et al., 2018; Yang, 2018). While the exact molecular mechanisms of reperfusion-related cardiomyocyte death remain not fully clarified, it thus implicates a pressing need for deep exploration and succedent unmarked novel therapeutic targets (Piper et al., 1998).

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was originally employed for treating refractory epilepsy and depression, leveraging its potential advantages in autonomic neuromodulation (George et al., 2007; González et al., 2019). Subsequent research has increasingly suggested that VNS can also confer protection against heart failure progression, due to the restoration of autonomic balance, baroreceptor sensitivity, and electrical stability (Capilupi et al., 2020; Verrier et al., 2022; Elamin et al., 2023). Recent studies have progressively unveiled the role of VNS in mitigating myocardial I/R injury through the activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, anti-oxidative stress response, or anti-apoptotic response (Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2022). However, the intricate mechanisms underlying VNS-mediated cardioprotection in experimental studies, along with limited clinical evidence, pose obstacles to its broader application in clinical practice.

Hence, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis are warranted to evaluate the effectiveness of VNS during myocardial I/R injury and provide a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of this therapeutic approach.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search for animal studies assessing the cardioprotection of VNS in myocardial I/R injury in MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Database from the inception to July 2023, with no language restriction. The following search terms were used: “myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury” OR “myocardial I/R injury” OR “myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury” AND “vagal nerve stimulation”. Moreover, we searched the references of comments, meeting abstracts, and review articles for additive studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included based on the following criteria: (a) reported the infarct size measured by triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) and Evan’s blue double staining method, (b) analyzed intervention received VNS treatment merely; comparator intervention received or no treatment, (c) with no cardiovascular-related comorbidity. We excluded studies that did not express infarct size as the percentage of infarct area over the area at risk (AAR) or did not quantify the ischemic area by Evans blue/TTC staining.

Data extraction

The data were extracted independently by two authors (Yu-Peng Xu and Xin-Yu Lu) from included studies, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. The following details were recorded in Table1: (1) studies’ information, including first author’s name, country, year of publication number of included animals, and duration of I/R injury; (2) animals’ characteristics, including species, gender and anesthetics; (3) the vagal nerve stimulation protocol, including stimulation site, duration, parameters and heart rate reduction; (4) methods for determining the infarct size. The results were expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation to minimize publication bias. The digital ruler software was used to measure the value when some data were only represented by graphs.

TABLE 1

| Author | Year | Country | Animals | Sample size | I/R duration | Anesthetic agent | Infarct size measurement | VNS protocols | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | VNS | Site of stimulation /Duration |

Parameters | HR reduction | Timing of VNS | |||||||

| Bruno et al.Buchholz et al. (2015) | 2015 | Argentina | Rabbits, NZ, M | 10 | 20 | 30min/3 h | Pentobarbital | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 10m, int or con | 0.1 m, 10HZ | 10%–20% | 10min before ischemia |

| Nederhoff et al.Nederhoff et al. (2019) | 2019 | Netherland | Mice, C57BL/6, M | 19 | 18 | 30min/48 h | Fentanyl/Dormicum | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 30s, con | 0.5 m, 10HZ | 15% | 10min before ischemia |

| Krekwit et al.Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2013) | 2013 | Thailand | Swines | 8 | 16 | 60min/2 h | Zoletil/Xylazine | Evans blue/TTC | LVN, 3h, int or con | 0.5 m, 20HZ | NA | 0min after ischemia |

| Chen et al.Chen et al. (2016) | 2016 | China | Dogs, mongrel, M | 12 | 9 | 60min/1 h | Pentobarbital | Evans blue/TTC | LVN, 2h, con | 0.1 m, 20HZ | NA | 0min after ischemia |

| Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2014) | 2014 | China | Rats, SD, M | 20 | 20 | 30min/2 h | Pentobarbital | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 30min, con | 2.0 m, 10 Hz | 10% | 15min after ischemia |

| Zhao et al.Zhao et al. (2013) | 2013 | China | Rats, SD, M | 8 | 8 | 60min/2 h | Pentobarbital | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 3.25h, con | 1.0 m, 5HZ | 10% | 15min before ischemia |

| Calvillo et al.Calvillo et al. (2011) | 2011 | Italy | Rats, SD, M | 13 | 6 | 30min/24 h | Isoflurane | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 24.7h, con | 0.5 m, 8-10HZ | 10% | 5min before ischemia |

| Yi et al. (Yi et al., 2016) | 2015 | China | Rats, SD, M | 12 | 12 | 30min/4 h | Pentobarbital | Evans blue/TTC | RVN, 30min, con | 0.2 m, 10HZ | 10% | 15min after ischemia |

| Nuntaphum et al.Nuntaphum et al. (2018) | 2018 | Thailand | Swines | 6 | 6 | 60min/2 h | Zoletil/Xylazine | Evans blue/TTC | LVN, 3h, int | 0.5 m, 20HZ | NA | 0min after ischemia |

| Krekwit et al.Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2014) | 2014 | Thailand | Swines | 7 | 8 | 60min/2 h | Zoletil/Xylazine | Evans blue/TTC | LVN, 2.5h, int | 0.5 m, 20HZ | NA | 30min after ischemia |

Characteristics of included studies, animals and VNS treatment.

VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; SD, Sprague-Dawley rats; NZ, new zealand rabbit; M, male; RVN, right vagus nerve stimulation; LVN, left vagus nerve stimulation, TTC, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride; HR, heart rate; con, continuous; int, intermittent; NA, none available.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently evaluated and graded the quality of included studies based on published criteria for animal experiments. One point for each of the following: a peer-reviewed publication, random allocation to groups, blinded assessment of outcome, sample size calculation, compliance with animal welfare regulations, and a statement of a potential conflict of interest. Any discrepancies were arbitrated by a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

All outcome data were treated as continuous variables in this meta-analysis, presented as the mean and standard deviation. DerSimonian and Laird random effects meta-analysis was used to measure the WMD and the related 95%CIs. Heterogeneity between studies results was evaluated by Cochran’s Q test and quantified by I2 statistics test. Begger’s and Egger’s test was used to assess the potential publication bias.

Results

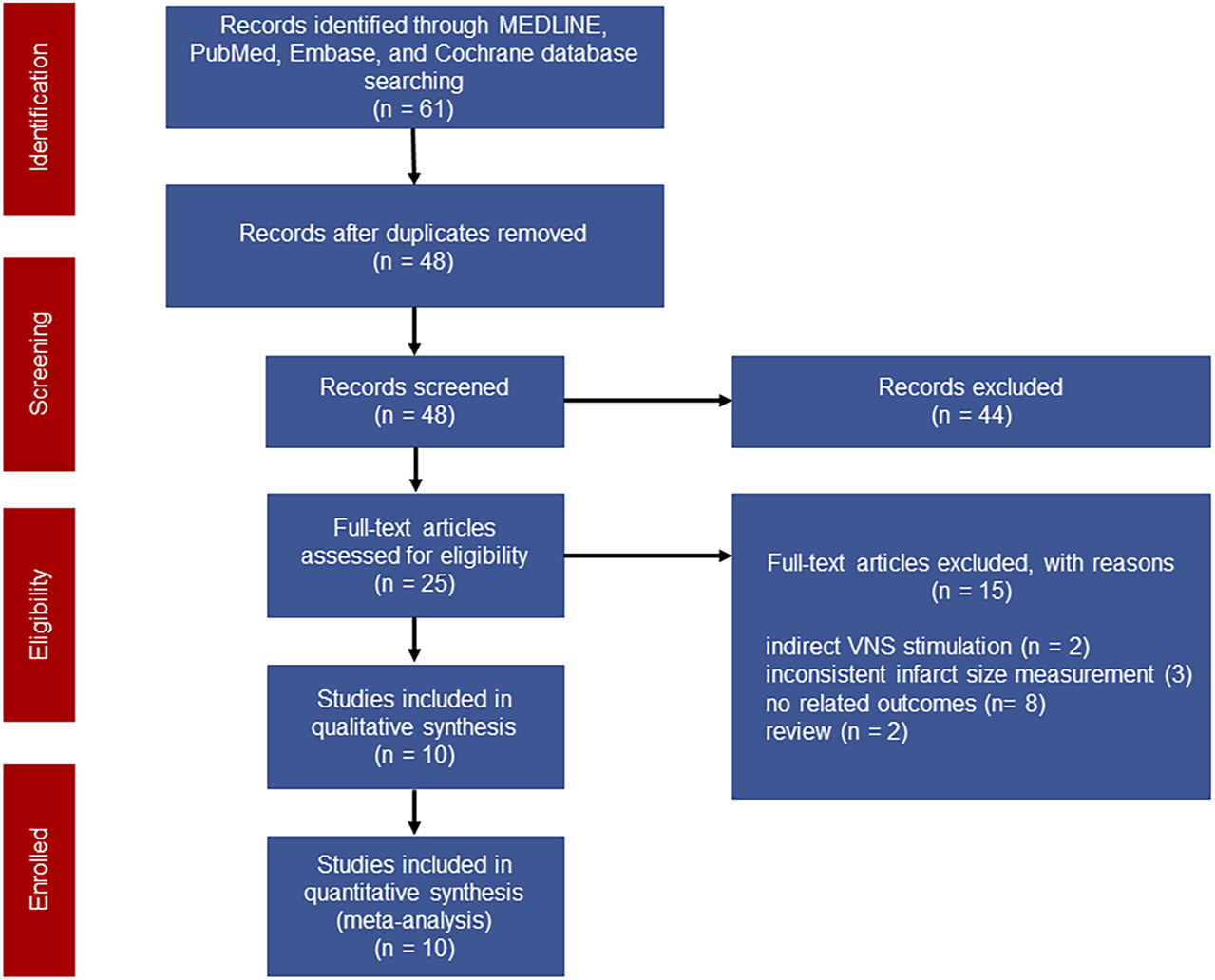

A total of 61 studies were initially screened and 10 studies comprising 238 animals matched the inclusion criteria for further quantitative analysis (Figure 1). Of these, 123 animals were treated with VNS and 115 animals were treated with control therapy. Cohort characteristics were presented in Table 1. Half of the studies used rodents with the remaining used rabbits, dogs and swine. Continuous, right cervical vagal trunk stimulation was conducted in most of enrolled studies for VNS, the remaining studies performed VNS in left vagal nerve with either continuous or intermittent regimen. The parameters of VNS varied substantially among the studies. The majority of studies reported a 10%–20% heart rate reduction during the procedure to guarantee the biological effect of VNS. Additionally, the potential mechanisms of action of VNS in myocardial I/R injury were detailed in Table 2, predominantly involving anti-inflammatory, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction anti-apoptosis.

FIGURE 1

Flow chart of the literature screening.

TABLE 2

| Studies | Year | Proposed mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Bruno et al | 2015 | Consistent vagal stimulation: co-activation of the sympathetic nervous system Intermittent vagal stimulation: activation of the Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway |

| Nederhoff et al | 2019 | A less inhibiting effect on inflammatory responsiveness |

| Krekwit et al | 2013 | Prevent mitochondrial dysfunction during myocardial I/R |

| Chen et al | 2016 | inhibiting oxidative stress and reducing cellular apoptosis |

| Wang et al | 2014 | Alleviating inflammatory responsiveness in early phase of myocardial I/R |

| Zhao et al | 2013 | Endothelial function and structure protection, anti-inflammatory activity via STAT3 signaling and NF-κB cascade |

| Calvillo et al | 2011 | anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activity |

| Yi et al | 2015 | Restraining inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress and apoptosis via IL-17A |

| Nuntaphum et al | 2018 | Attenuation of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, apoptosis and metabolic abnormalities |

| Krekwit et al | 2014 | Protect mitochondrial integrity by mitigating cytochrome c induced apoptosis |

The underlying mechanisms involved in the protective effects of VNS against myocardial I/R injury.

VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion.

Infarct size

Data on infarct size were available in 10 studies. VNS was associated with a dramatic reduction of infarct size assessed by Evans blue/TTC staining post myocardial I/R injury (WMD: 25.24, 95% CI: 32.24 to −18.23, p < 0.001, Figure 2), accompanied by high heterogeneity (I2 = 95.3%, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias according to Begg’s and Egger’s test. Subsequent sensitivity analysis utilizing the one-study-omit method showed similar findings (Table 3). In addition, stratified analysis according to vagal stimulation site, duration, animal species and state region and myocardial I/R regimen did not influence the efficacy results of infarct size after I/R assaults (Table 4). Further meta-regression also did not reveal any interaction between the pre-specified covaries and VNS-mediated reduction in myocardial I/R damage (Table 5).

FIGURE 2

Forest plot of infarct size for VNS treatment against myocardial I/R injury. VNS, vagus nerve stimulation.

TABLE 3

| Omitted studies | Pooled estimate | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buchholz et al. (2015) | −27.375332 | −34.116432; −20.634233 | <0.001 |

| Nederhoff et al. (2019) | −26.351851 | −33.873882; −18.829815 | <0.001 |

| Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2013) | −24.491714 | −31.822363; −17.161068 | <0.001 |

| Chen et al. (2016) | −25.56126 | −33.027866; −18.094656 | <0.001 |

| Wang et al. (2014) | −25.26421 | −32.741207; −17.787214 | <0.001 |

| Zhao et al. (2013) | −25.974266 | −34.273678; −17.674858 | <0.001 |

| Calvillo et al. (2011) | −23.037252 | −29.975634; −16.098871 | <0.001 |

| Yi et al. (2016) | −26.155228 | −35.789894; −16.520563 | <0.001 |

| Nuntaphum et al. (2018) | −22.940166 | −28.790264; −17.090067 | <0.001 |

| Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2014) | −25.065401 | −32.455986; −17.674816 | <0.001 |

| Combined | −25.235 | −32.238; −18.232 | <0.001 |

Sensitivity analysis for pooled estimates of infarct size by leaving each study out.

CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 4

| Pooled estimates | No. of studies | WMD (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VNS type | |||

| Intermittent | 4 | −32.49 (−44.51; −20.47) | <0.001 |

| Consistent | 8 | −19.23 (−31.91; −6.55) | 0.003 |

| Site of vagus nerve | |||

| RVN | 6 | −21.24 (−28.15; −14.33) | <0.001 |

| LVN | 4 | −31.38 (−40.97; −21.79) | <0.001 |

| VNS duration | |||

| >60min | 6 | −31.49 (−41.67; −21.30) | <0.001 |

| ≤60min | 4 | −16.39 (−24.21; −8.58) | <0.001 |

| Animal | |||

| Small animals | 6 | −21.24 (−28.15; −14.33) | <0.001 |

| Large animals | 4 | −31.38 (−40.97; −21.79) | <0.001 |

| Region | |||

| Asian | 7 | −26.58 (−33.74; −19.42) | <0.001 |

| Europe/America | 3 | −22.75 (−42.29; 10.14) | 0.029 |

| Ischemic duration | |||

| 30min | 5 | −21.83 (−30.66; −13.00) | <0.001 |

| 60min | 5 | −28.62 (−39.31; −17.92) | <0.001 |

| Reperfusion duration | |||

| ≥2 h | 4 | −21.14 (−31.12; −11.15) | <0.001 |

| <2 h | 6 | −28.05 (−37.16; −18.93) | <0.001 |

| Total | 10 | −25.24 (−32.24; −18.23) | <0.001 |

Subgroup analysis for pooled estimates of infarct size according to vagal stimulation site, duration, animal species, state region and myocardial I/R regimen.

VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; RVN, right vagus nerve stimulation; LVN, light vagus nerve stimulation; WMD, weighed mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 5

| Covariates | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation type | −7.89749 | −20.84117; 5.046191 | 0.197 |

| Site of vagus nerve | −9.519369 | −26.61292; 7.574181 | 0.235 |

| Duration of VNS | −2.451402 | −7.261435; 2.358632 | 0.274 |

| Species | −3.103634 | −9.256419; 3.049152 | 0.278 |

| Region | −5.766457 | −12.56464; 1.031722 | 0.086 |

| Ischemic duration | −6.530279 | −23.95324; 10.89268 | 0.413 |

| Reperfusion duration | −6.654516 | −24.30372; 10.99469 | 0.410 |

Meta-regression for infarct size.

VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; CI, confidence interval.

Coefficient* indicates the estimates (WMD) of corresponding covariates for infarct size in the context of meta-regression.

Cardiac function

Data on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was available in 4 studies. VNS was associated with a significantly improved systolic function after myocardial I/R injury (WMD: 10.12, 95% CI: 4.28 to 15.97, p < 0.001, Figure 3), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 71.6%, p < 0.001). Data on left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) were available in 5 studies. In accordance with the results for LVEF, there was also a significantly diminished LVEDP in VNS treated group (WMD: 5.79, 95% CI: 9.84 to −1.74, p = 0.005, Figure 4), despite high heterogeneity (I2 = 90.2%, p < 0.001). One-study-omit sensitivity analysis presented similar results (Table 6). Moreover, there were no signs of any correlation between the pre-specified covaries and both pooled estimates for LVEF and LVDEP, respectively (Table 7).

FIGURE 3

Forest plot of LVEF for VNS treatment in myocardial I/R injury. LVEF: left ventricular eject fraction; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation.

FIGURE 4

Forest plot of LVEDP for VNS treatment in myocardial I/R injury. LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation.

TABLE 6

| LVEF | LVDEP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omitted studies | Pooled estimate | 95% CI | p-value | Omitted studies | Pooled estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

| Nederhoff et al. (2019) | 12.795615 | 9.4486408; 16.14259 | <0.001 | Buchholz et al. (2015) | −7.1386299 | −9.619873; −4.6573863 | <0.001 |

| Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2013) | 9.1613674 | 0.56876612; 17.753969 | 0.037 | Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2013) | −6.4334135 | −11.459242; −1.4075845 | 0.012 |

| Nuntaphum et al. (2018) | 9.7538939 | 1.3396233; 18.168163 | 0.023 | Zhao et al. (2013) | −5.08149 | −9.2801981; −.88278198 | 0.018 |

| Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2014) | 8.3556633 | 1.491866; 15.21946 | 0.017 | Nuntaphum et al. (2018) | −5.2803035 | −9.7766495; −.78395754 | 0.021 |

| Shinlapawittayatorn et al. (2014) | −4.9952269 | −9.2649097; −.7255435 | 0.022 | ||||

| Combined | 10.124 | 4.277; 15.971 | 0.001 | Combined | −5.793 | −9.842; −1.744 | 0.005 |

Sensitivity analysis for left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVDEP).

LVEF, left ventricular eject fraction; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 7

| LVEF | LVEDP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-value | Covariates | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-value |

| Stimulation type | 6.042812 | −3.079621; 15.16525 | 0.104 | Stimulation type | −3.820668 | −7.660276; 0.0189403 | 0.051 |

| Site of vagus nerve | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Site of vagus nerve | −2.525814 | −14.33199; 9.280359 | 0.545 |

| Duration of VNS | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Duration of VNS | −6.038574 | −12.66625; 0.589101 | 0.063 |

| Animal | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Animal | −3.598583 | −8.449862; 1.252697 | 0.099 |

| Region | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Region | −3.598583 | −8.449862; 1.252697 | 0.099 |

| Ischemic duration | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Ischemic duration | −6.038574 | −12.66625; 0.589101 | 0.063 |

| Reperfusion duration | 11.20161 | −7.079008; 29.48222 | 0.119 | Reperfusion duration | −6.038574 | −12.66625; 0.589101 | 0.063 |

Meta-regression for left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVDEP).

LVEF, left ventricular eject fraction; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; CI, confidence interval.

Coefficient* indicates the estimates (WMD) of corresponding covariates for LVEF, or LVDEP, in the context of meta-regression.

Discussion

As far as we are aware, this is the first meta-analysis ever conducted to demonstrate that VNS is beneficial in protecting the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. By incorporating data from 10 distinct studies, our research evaluated the efficacy of VNS in preclinical studies. These findings indicated that VNS could significantly reduce infarct size during myocardial I/R injury and also improve heart function by reducing LVEDP and increasing LVEF. Intriguingly, these benefits were observed to be independent of the type and site of VNS or the animal size.

Myocardial I/R injury remains a significant clinical challenge despite advancements in reperfusion therapies such as thrombolysis and PCI(Férez Santander et al., 2004). This is primarily because of the intricated pathophysiologic process underlying reperfusion injury, including oxidative stress, calcium overload, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell apoptosis (Davidson et al., 2019). During the reperfusion, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production due to the abrupt increase in oxygen supply and corresponding antioxidant enzyme insufficiency are the critical factor of cardiomyocyte death (Férez Santander et al., 2004; Hausenloy and Yellon, 2013). Meanwhile, previous studies reported that mitochondria are the main source of ROS and mitochondrial damage affects post-injury cardiac function by dysregulated ROS modulation. In a vicious cycle, ROS can also impair the mitochondrial respiratory chain and promote mitochondrial membrane depolarization, leading to impaired ATP production and further exacerbating cell death (Murphy and Steenbergen, 2008; Ong and Hausenloy, 2010; Ong and Gustafsson, 2012). Moreover, non-coding RNA, including mi-RNA and Lnc-RNA have increasingly emerged as key regulators in various cellular processes such as apoptosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis and have implications for myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (Ong et al., 2018). Unfortunately, there are currently limited therapeutic options available to prevent heart damage from reperfusion injury. Several pharmacological interventions have been tried to attenuate myocardial I/R injury by targeting the abovementioned cellular and molecular mechanisms. Vitamins C and E, being well-established antioxidant, have been shown to reduce cardiomyocyte death by inhibiting ROS release during the reperfusion injury (Rodrigo et al., 2014). In addition to the anti-inflammatory drugs, calcium channel blockers or cyclosporine also showed similar cardioprotective effects in retarding infarct area extension and subsequent deterioration of systolic function in a preclinical setting (Boden et al., 2000; Piot et al., 2008; Trelle et al., 2011). However, none of them showed the theoretical potential in clinical translation due to the huge gap between compelling experimental evidence and scant clinical data.

The vagus nerves, originating from the medulla oblongata, are the longest cranial nerve and is involved in the regulation of various physiological systems (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000). VNS is first identified as a therapeutic approach for Inflammatory disease by activating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Bonaz et al., 2016). On the contrary, vagal denervation consistently released the lymphocyte from thymus to spleen and lymph nodes, which indicated the role of vagus nerves in controlling inflammatory status (Antonica et al., 1994; Antonica et al., 1996). Recently, clinical trials and preclinical trials have demonstrated the beneficial effect of VNS in reducing arrhythmias and hospitalizations, improving cardiac contractility and quality of life for patients with heart failure or AF, which suggests a crucial role of VNS in the treatment of heart disease (Li et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2009; Zannad et al., 2015; Gold et al., 2016). In terms of the physiological properties of VNS, it was also utilized as a promising method for alleviating myocardial reperfusion injury. As expected, VNS modulates inflammatory cytokines and simultaneously inhibits ROS by activation of AMPK cascades (Kong et al., 2012). Additionally, experimental research indicated that VNS preserved the integrity and function of mitochondria by regulating mitochondrial dynamics, biogenesis, and mitophagy, which turns into cardioprotection against myocardial I/R injury (Nuntaphum et al., 2018). Meanwhile, VNS suppresses the sympathetic nerve sprouting and blocks the inflammatory process, which attenuating ventricular remodeling and decreases the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias after reperfusion injury on mechanism, Jak2/STAT3, NF-κB, Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway, which are responsible for VNS induced preventive effects on myocardium during reperfusion injury (Buchholz et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2021). Yoshihiko et al. reveal a PI3K/Akt pathway for HIF-1α induction by vagal stimulation, which minimizes cardiomyocyte apoptosis under hypoxia and normoxia (Kakinuma et al., 2005). Intriguingly, in vitro studies also have demonstrated that VNS could impede FoxO3A phosphorylation through P13K/AKT signaling activation, thus optimizing the sequelae of infarct myocardium (Luo et al., 2020). Collectively, preclinical evidence confirms the potential ability of VNS in facilitating heart recovery from I/R damage, and raise the possibility that it may have a role in improving the prognostic endpoints of myocardial infarction patients receiving timely revascularization. In accordance with the animal experimental results, Yu et al. have reported that tragus stimulation significantly reduces the inducibility of reperfusion-induced ventricular tachycardia and the levels of myocardial injury biomarkers, improves systolic function in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI(Yu et al., 2017).It also indicates that suppressed inflammatory response, evidenced by lower IL-6, IL-1β, high-mobility group-box 1 protein 1, and TNF-α, contributes to the favorable effects of tragus stimulation. However, there remains a great challenge to translate the cardioprotective effects of VNS into myocardial infarction patients, and it therefore is still a pressing need for well-designed randomized control trials to further confirm the role of VNS in the setting of myocardial I/R injury, and contemporaneously deeply elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Limitations

First, there is no standard protocol for myocardial I/R regimen (i.e., different ischemic or reperfusion duration) or VNS treatment (i.e., different parameters, stimulation site, and type), while subgroup analysis shows remarkable consistent outcomes among the studies. Second, the pooled results from this meta-analysis are based on animals without comorbidities which may impede extrapolating these findings to complicated clinical situations. Third, despite significant heterogeneity that may affect the interpretation of the results, sensitivity analysis and subgroup analyses with robust data substantially support the benefits and reliability of VNS in reducing infarct size and improving cardiac function after reperfusion injury. Meanwhile, the prespecified covariates have no impact on pooled results of both infarct size and LVEF by meta-regression. Finally, the majority of outcomes of included studies concentrate on infarct area and LVEF, rather than mortality or other cardiac functional indicators (e.g., 6-min walking or cardiopulmonary exercise testing), which may more precisely reflect the prognosis and symptoms in clinical practice.

Conclusion

In summary, VNS is a promising therapeutic strategy for preventing lethal myocardial reperfusion injury according to the significant advantages in limiting infarct size and cardiac function from basic studies. It thus provides the theoretical feasibility and reliability to extend the utilization of VNS in ST elevation myocardial infarction patients with revascularization, and implicates the future prospects of clinical application.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because This study is meta-analysis is a re-examination of data from published articles.

Author contributions

Y-HC: Writing–review and editing. Y-PX: Writing–original draft. X-YL: Writing–original draft. Z-QS: Writing–original draft. HL: Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Wenzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No: Y20180079) to Y-HC and the 2023 Science and Technology Innovation Activity Plan for Students in Zhejiang Province (No. 2023R413020) to X-YL.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y-HC for providing the idea, designing and subsequent guiding of this article. We thank HL for revising of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Antonica A. Ayroldi E. Magni F. Paolocci N. (1996). Lymphocyte traffic changes induced by monolateral vagal denervation in mouse thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs. J. Neuroimmunol.64 (2), 115–122. 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00157-3

2

Antonica A. Magni F. Mearini L. Paolocci N. (1994). Vagal control of lymphocyte release from rat thymus. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst.48 (3), 187–197. 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90047-7

3

Berthoud H. R. Neuhuber W. L. (2000). Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton. Neurosci.85 (1-3), 1–17. 10.1016/s1566-0702(00)00215-0

4

Boden W. E. van Gilst W. H. Scheldewaert R. G. Starkey I. R. Carlier M. F. Julian D. G. et al (2000). Diltiazem in acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic agents: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Incomplete Infarction Trial of European Research Collaborators Evaluating Prognosis post-Thrombolysis (INTERCEPT). Lancet355 (9217), 1751–1756. 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02262-5

5

Bonaz B. Sinniger V. Pellissier S. (2016). Anti-inflammatory properties of the vagus nerve: potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. J. Physiol.594 (20), 5781–5790. 10.1113/jp271539

6

Buchholz B. Donato M. Perez V. Deutsch A. C. R. Höcht C. Del Mauro J. S. et al (2015). Changes in the loading conditions induced by vagal stimulation modify the myocardial infarct size through sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions. Pflugers Arch.467 (7), 1509–1522. 10.1007/s00424-014-1591-2

7

Calvillo L. Vanoli E. Andreoli E. Besana A. Omodeo E. Gnecchi M. et al (2011). Vagal stimulation, through its nicotinic action, limits infarct size and the inflammatory response to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J. Cardiovasc Pharmacol.58 (5), 500–507. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31822b7204

8

Capilupi M. J. Kerath S. M. Becker L. B. (2020). Vagus nerve stimulation and the cardiovascular system. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med.10 (2), a034173. 10.1101/cshperspect.a034173

9

Chen M. Li X. Yang H. Tang J. Zhou S. (2020). Hype or hope: vagus nerve stimulation against acute myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Trends Cardiovasc Med.30 (8), 481–488. 10.1016/j.tcm.2019.10.011

10

Chen M. Zhou X. Yu L. Liu Q. Sheng X. Wang Z. et al (2016). Low-level vagus nerve stimulation attenuates myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury by antioxidative stress and antiapoptosis reactions in canines. J. Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.27 (2), 224–231. 10.1111/jce.12850

11

Davidson S. M. Ferdinandy P. Andreadou I. Bøtker H. E. Heusch G. Ibáñez B. et al (2019). Multitarget strategies to reduce myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.73 (1), 89–99. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.086

12

Deng S. Zhang Y. Xin Y. Hu X. (2022). Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates acute kidney injury induced by hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 21662. 10.1038/s41598-022-26231-w

13

Elamin A. B. A. Forsat K. Senok S. S. Goswami N. (2023). Vagus nerve stimulation and its cardioprotective abilities: a systematic review. J. Clin. Med.12 (5), 1717. 10.3390/jcm12051717

14

Férez Santander S. M. Márquez M. F. Peña Duque M. A. Ocaranza Sánchez R. de la Peña Almaguer E. Eid Lidt G. (2004). Myocardial reperfusion injury. Rev. Esp. Cardiol.57 (Suppl. 1), 9–21. 10.1157/13067415

15

George M. S. Nahas Z. Borckardt J. J. Anderson B. Burns C. Kose S. et al (2007). Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of depression and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother.7 (1), 63–74. 10.1586/14737175.7.1.63

16

Gold M. R. Van Veldhuisen D. J. Hauptman P. J. Borggrefe M. Kubo S. H. Lieberman R. A. et al (2016). Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of heart failure: the INOVATE-HF trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.68 (2), 149–158. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.525

17

González H. F. J. Yengo-Kahn A. Englot D. J. (2019). Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am.30 (2), 219–230. 10.1016/j.nec.2018.12.005

18

González-Montero J. Brito R. Gajardo A. I. Rodrigo R. (2018). Myocardial reperfusion injury and oxidative stress: therapeutic opportunities. World J. Cardiol.10 (9), 74–86. 10.4330/wjc.v10.i9.74

19

Hausenloy D. J. Yellon D. M. (2013). Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a neglected therapeutic target. J. Clin. Invest.123 (1), 92–100. 10.1172/jci62874

20

Kakinuma Y. Ando M. Kuwabara M. Katare R. G. Okudela K. Kobayashi M. et al (2005). Acetylcholine from vagal stimulation protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia and hypoxia involving additive non-hypoxic induction of HIF-1alpha. FEBS Lett.579 (10), 2111–2118. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.065

21

Kong S. S. Liu J. J. Yu X. J. Lu Y. Zang W. J. (2012). Protection against ischemia-induced oxidative stress conferred by vagal stimulation in the rat heart: involvement of the AMPK-PKC pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci.13 (11), 14311–14325. 10.3390/ijms131114311

22

Li M. Zheng C. Sato T. Kawada T. Sugimachi M. Sunagawa K. (2004). Vagal nerve stimulation markedly improves long-term survival after chronic heart failure in rats. Circulation109 (1), 120–124. 10.1161/01.cir.0000105721.71640.da

23

Luo B. Wu Y. Liu S. L. Li X. Y. Zhu H. R. Zhang L. et al (2020). Vagus nerve stimulation optimized cardiomyocyte phenotype, sarcomere organization and energy metabolism in infarcted heart through FoxO3A-VEGF signaling. Cell Death Dis.11 (11), 971. 10.1038/s41419-020-03142-0

24

Murphy E. Steenbergen C. (2008). Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol. Rev.88 (2), 581–609. 10.1152/physrev.00024.2007

25

Nederhoff M. G. J. Fransen D. E. Verlinde S. Brans M. A. D. Pasterkamp G. Bleys R. (2019). Effect of vagus nerve stimulation on tissue damage and function loss in a mouse myocardial ischemia-reperfusion model. Auton. Neurosci.221, 102580. 10.1016/j.autneu.2019.102580

26

Nuntaphum W. Pongkan W. Wongjaikam S. Thummasorn S. Tanajak P. Khamseekaew J. et al (2018). Vagus nerve stimulation exerts cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury predominantly through its efferent vagal fibers. Basic Res. Cardiol.113 (4), 22. 10.1007/s00395-018-0683-0

27

Ong S. B. Gustafsson A. B. (2012). New roles for mitochondria in cell death in the reperfused myocardium. Cardiovasc Res.94 (2), 190–196. 10.1093/cvr/cvr312

28

Ong S. B. Hausenloy D. J. (2010). Mitochondrial morphology and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res.88 (1), 16–29. 10.1093/cvr/cvq237

29

Ong S. B. Katwadi K. Kwek X. Y. Ismail N. I. Chinda K. Ong S. G. et al (2018). Non-coding RNAs as therapeutic targets for preventing myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets22 (3), 247–261. 10.1080/14728222.2018.1439015

30

Piot C. Croisille P. Staat P. Thibault H. Rioufol G. Mewton N. et al (2008). Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med.359 (5), 473–481. 10.1056/NEJMoa071142

31

Piper H. M. García-Dorado D. Ovize M. (1998). A fresh look at reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res.38 (2), 291–300. 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00033-9

32

Rodrigo R. Hasson D. Prieto J. C. Dussaillant G. Ramos C. León L. et al (2014). The effectiveness of antioxidant vitamins C and E in reducing myocardial infarct size in patients subjected to percutaneous coronary angioplasty (PREVEC Trial): study protocol for a pilot randomized double-blind controlled trial. Trials15, 192. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-192

33

Shinlapawittayatorn K. Chinda K. Palee S. Surinkaew S. Kumfu S. Kumphune S. et al (2014). Vagus nerve stimulation initiated late during ischemia, but not reperfusion, exerts cardioprotection via amelioration of cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction. Heart rhythm.11 (12), 2278–2287. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.08.001

34

Shinlapawittayatorn K. Chinda K. Palee S. Surinkaew S. Thunsiri K. Weerateerangkul P. et al (2013). Low-amplitude, left vagus nerve stimulation significantly attenuates ventricular dysfunction and infarct size through prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction during acute ischemia-reperfusion injury. Heart rhythm.10 (11), 1700–1707. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.08.009

35

Trelle S. Reichenbach S. Wandel S. Hildebrand P. Tschannen B. Villiger P. M. et al (2011). Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. Bmj342, c7086. 10.1136/bmj.c7086

36

Verrier R. L. Libbus I. Nearing B. D. KenKnight B. H. (2022). Multifactorial benefits of chronic vagus nerve stimulation on autonomic function and cardiac electrical stability in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Front. Physiol.13, 855756. 10.3389/fphys.2022.855756

37

Wang M. Deng J. Lai H. Lai Y. Meng G. Wang Z. et al (2020). Vagus nerve stimulation ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibiting NF-κB activation and iNOS protein expression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2020, 7106525. 10.1155/2020/7106525

38

Wang Q. Li R. P. Xue F. S. Wang S. Y. Cui X. L. Cheng Y. et al (2014). Optimal intervention time of vagal stimulation attenuating myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Inflamm. Res.63 (12), 987–999. 10.1007/s00011-014-0775-8

39

Yang C. F. (2018). Clinical manifestations and basic mechanisms of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi30 (4), 209–215. 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_33_18

40

Yi C. Zhang C. Hu X. Li Y. Jiang H. Xu W. et al (2016). Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting the expression of interleukin-17A. Exp. Ther. Med.11 (1), 171–176. 10.3892/etm.2015.2880

41

Yu L. Huang B. Po S. S. Tan T. Wang M. Zhou L. et al (2017). Low-level tragus stimulation for the treatment of ischemia and reperfusion injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a proof-of-concept study. JACC. Cardiovasc. Interv.10 (15), 1511–1520. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.04.036

42

Zannad F. De Ferrari G. M. Tuinenburg A. E. Wright D. Brugada J. Butter C. et al (2015). Chronic vagal stimulation for the treatment of low ejection fraction heart failure: results of the NEural Cardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure (NECTAR-HF) randomized controlled trial. Eur. Heart J.36 (7), 425–433. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu345

43

Zhang Y. Popovic Z. B. Bibevski S. Fakhry I. Sica D. A. Van Wagoner D. R. et al (2009). Chronic vagus nerve stimulation improves autonomic control and attenuates systemic inflammation and heart failure progression in a canine high-rate pacing model. Circ. Heart Fail2 (6), 692–699. 10.1161/circheartfailure.109.873968

44

Zhao M. He X. Bi X. Y. Yu X. J. Gil Wier W. Zang W. J. (2013). Vagal stimulation triggers peripheral vascular protection through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in a rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Basic Res. Cardiol.108 (3), 345. 10.1007/s00395-013-0345-1

45

Zhao S. Dai Y. Ning X. Tang M. Zhao Y. Li Z. et al (2021). Vagus nerve stimulation in early stage of acute myocardial infarction prevent ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac remodeling. Front. Cardiovasc Med.8, 648910. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.648910

Summary

Keywords

myocardial I/R injury, vagus nerve stimulation, cardioprotection, meta-analysis, molecular mechanisms

Citation

Xu Y-P, Lu X-Y, Song Z-Q, Lin H and Chen Y-H (2023) The protective effect of vagus nerve stimulation against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: pooled review from preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1270787. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1270787

Received

01 August 2023

Accepted

31 October 2023

Published

14 November 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Helio Cesar Salgado, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Reviewed by

Nazareno Paolocci, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Suren Soghomonyan, The Ohio State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Xu, Lu, Song, Lin and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi-He Chen, chenyihe@wmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.