- 1Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Jinnah University for Women, Karachi, Pakistan

- 2Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

- 3Department of Pharmacy Practice, Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan

- 4Department of Pharmacy Practice, School of Pharmacy, IMU (Former International Medical University), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 5Department of Pharmacy Practice, Shifa College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 6Department of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Jinnah University for Women, Karachi, Pakistan

Background: The prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) in older adults populations is a significant concern, often leading to adverse drug events and increased health-care utilization.

Objective: In the present study, we aim to evaluate the prevalence of PIMs among hospitalized older adults patients in Pakistan using STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions) criteria version 3.

Methodology: A prospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary-care hospital in Karachi over 1 year from March 2023 to March 2024. Patients aged 60 years and above, prescribed at least one medication, were included. Data on demographics, comorbidities, and medications were collected and analyzed using the STOPP criteria to identify PIMs. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. To find the variables linked to PIM use, multivariable logistic regression analysis was used. The 95% CI and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) were used to measure the statistical association’s strength. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results: Among 450 participants, the median age was 67 years, with a predominance of male patients (55.3%). The prevalence of PIM use was 56.6%, and a total of 388 instances of PIM use were identified according to STOPP criteria version 3. Acetylsalicylic acid (18%) and pheniramine (11%) were the most frequent inappropriately prescribed medications. The multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that polypharmacy and the presence of one or more comorbidities primarily influence the PIM use.

Conclusion: The findings highlight a critical need for improved prescribing practices in the older adults population in Pakistan. Utilizing screening tools like the STOPP criteria can significantly enhance medication safety and optimize pharmacotherapy in this vulnerable group.

Introduction

Potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use is a significant concern in the older adults population, as it can lead to adverse drug events, hospitalizations, and other negative health outcomes (Lavan and Gallagher, 2016). With the growing age, there is an increased prevalence of chronic diseases which progress to multiple comorbidities. These multiple comorbidities are often accompanied by polypharmacy. The former and the latter are important factors that subsequently lead to the use of potentially inappropriate medication in this vulnerable population (Hudhra et al., 2016; Khatter et al., 2021).

Polypharmacy and PIM go hand in hand. There have been more than 20 definitions proposed for the term polypharmacy, with all of them revolving around the number of medications prescribed to the patient. The numeric threshold of medications for polypharmacy varies from 4 to 10 or even more (Khezrian et al., 2020). Polypharmacy may also be referred to as the use of unnecessary medication having a significant negative impact on patients’ health. Additionally, it also exerts an economical burden through misutilization of health-care services, wastage of limited medical resources, and additional costs to treat any adverse event (Kojima et al., 2012). A number of studies have documented that optimization of pharmacotherapy in the older adults cannot be just achieved by tackling polypharmacy per se but also by considering the inappropriate prescribing of medications (Scheen, 2014; Topinková et al., 2012).

The impact and consequences of polypharmacy on patient care are not recent findings and have been known since years. However, it is noteworthy that its complexity and magnitude is increasing day by day. The presence of comorbidities in the older adults warrants the need of polypharmacy; however, its negative impact cannot be neglected (Drusch et al., 2021). It includes but is not limited to medication errors, adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, and drug interactions. Compared to younger individuals, prescribing in the older adults is complex. Owing to age-related organ pathophysiology and declined function of the regulatory processes, the older adults are at an increased risk of inappropriate prescribing outcomes (Fulton and Riley Allen, 2005).

It has been well documented in a number of epidemiological studies that in patients aged 50 years and above, the prevalence of polypharmacy ranges from 12% to 48%, which is quite alarming (Aubert et al., 2016). Identification of the inappropriate medications and medications having higher risks with adverse outcomes is a useful tool to improve prescribing in the older adults. Taking this into account, numerous screening tools have been developed. The most commonly cited tools are the START (Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment)/STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions), the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) (Hanlon and Schmader, 2013), and the Beers Criteria (American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2015). A concise explanation regarding why the prescribing practice is potentially inappropriate is associated with each criterion.

The START/STOPP tool was first used in 2008, and till date, it is the most widely used and validated tool. It was developed by a panel of United Kingdom and Irish experts. The START criteria identify the medications that are needed to optimize medication therapy in the older adults, while the STOPP criteria identify medications that may impose potential harm in this population (Abukhalil et al., 2022). Recently, the tool has been updated in 2023 (O‘Mahony et al., 2023). The latest version comprises a set of 190 criteria (57 START and 133 STOPP criteria) compared to 114 criteria in version 2 and 87 criteria in version 1. There has been a 66.7% increase in the criteria compared to its predecessors. The majority of the STOPP/START version 3 criteria are based on systematic review and clinical trial evidence.

The START/STOPP criteria have been shown to be more sensitive than Beers criteria in identifying inappropriate prescribing. The tool is easy to use and has several advantages over other tools. The sequential arrangement of the criteria by the physiological systems facilitates its application in everyday practice. Moreover, it also provides a list of potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIPs) by omission (START criteria) (Díaz Planelles et al., 2023). Based on the global population ranking, Pakistan is the sixth most populated country. Presently, the number of older adults is more than eight million, and by 2050, this number is expected to increase more than three times (Cassum et al., 2020). There is a great paucity of data on the magnitude of PIP in Pakistan.

The aim of the present study is to explore the prevalence of inappropriate prescribing in the Pakistani older adults population in light of STOPP criteria version 3 and to explore the factors that influence inappropriate prescribing. In this study, every STOPP criterion was used. The START criteria were not used because the purpose of this study was not to assess possible prescribing omissions issues.

Methodology

Study setting and design

A prospective observational study design was implemented in an 850-bed tertiary-care hospital of Karachi, Pakistan, providing a range of medical and surgical services to the residents of Karachi.

All patients aged 60 years and above admitted to the inpatient department of the hospital fulfilling the inclusion criteria, i.e., prescribed with at least one medication, were included in the study. To achieve the maximum number of hospitalized older adults patients, the study was conducted in the medicine, cardiology, nephrology, orthopedic, and surgical wards of the inpatient department. The wards were selected on the basis of the list of the wards provided by the hospital administration. The list was formulated on the basis of greater admissions of geriatric patients in the mentioned wards. Conversely, patients hospitalized for palliative care, acute conditions, terminal illnesses, intensive care, and short-term prognoses were excluded. Moreover, those who had incomplete medical records and were hospitalized for less than 72 h were also not included.

Study variables

The prevalence of PIMs was the dependent variable of the study, while gender, age groups, number of medications, and comorbidities were the independent variables.

Sample size calculation

Single population proportion formula was used to obtain the sample size for the study (Pourhoseingholi et al., 2013). The sample size was obtained with a 95% confidence interval (Z statistic corresponding to 95% confidence interval = 1.96) with precision (minimum effect size) of 0.05 and an expected prevalence of 64% (0.64), as reported by Mazhar et al. (2018). The calculated sample size was then adjusted for 20% participant loss (approximate). Hence, the final required sample size was approximately 425 older adults patients. A total of 450 samples were successfully obtained, achieving 105.8% of the intended sample size. Simple random sampling technique was then employed to select the study participants.

Data collection

Data were collected for a period of 1 year from 1 March 2023 to 1 March 2024. The demographic characteristics of the patients, along with their current and past medical diagnoses, comorbidity burden, current regular prescription medications, laboratory profiles and readings, and any history of drug allergies or intolerances, were thoroughly documented by the research pharmacist in a data abstraction sheet.

The comorbidity burden was measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (Charlson et al., 2022). A higher CCI score indicated greater comorbidity burden. The patients were split into three groups: namely, mild patients (those with CCI scores between 1 and 2), moderate patients (those with CCI scores between 3 and 4), and severe patients (those with CCI scores ≥5 and those without any comorbidity). A history of cardiac arrhythmia, peripheral vascular illness, cerebral vasculopathy, ischemic heart disease, or chronic heart failure was considered a cardio- and cerebrovascular disease of comorbidities in CCI. Diabetes mellitus, cancer, cerebrovascular accidents, hypertension, and coronary artery disease were among the comorbidities identified.

All medications prescribed to the patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were then classified by the pharmaceutical specialties as endorsed by the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Classification (ATC) system (Organization and Organization, 2000). The medications were classified up to the ATC level 5. Polypharmacy was defined as taking four or more medications.

The collected data were then assessed according to STOPP criteria version 3 to identify PIM (O’Mahony et al., 2023). The STOPP criteria are helpful in providing an explanation for why the medication is potentially inappropriate. The explanations were classified based on the indication of the medication and the medication used in the respective physiological system.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 was used to perform the statistical analysis. Demographic characteristics of the study participants were represented as descriptive statistics by calculating the median, interquartile ranges (IQR), and percentages with a 95% confidence interval. The relationship between each independent variable and the dependent variable (PIM) was examined using cross-tabulation in bivariate analysis, and a crude odds ratio was produced. The final multivariable logistic regression model then included variables found in the bivariate analysis with p < 0.25. To find the variables linked to PIMs, multivariable logistic regression analysis was used. The adjusted OR (aOR) and 95% CI were used to gauge the statistical association’s strength. After adjusting for other predictor variables in a model, the aOR shows how changes in one predictor variable affect the likelihood that a response variable will occur. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

Ethical consideration

The ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Jinnah University for Women (JUW/IERB/PHARM-ARA-013/2023). Similarly, prior approval was also obtained from the tertiary-care hospital where the study was conducted. Informed verbal consent was also obtained from the study participants.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 450 older adults patients were included in the study. The majority of the study population were men (55.3%) (n = 249). The median (IQR) age of the patients was 67 (74–64) years. More than 78% of the patients had a Charlson Comorbidity Index score greater than two. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were the most prevalent (49.6% and 33.8%) comorbidities. More than 2,800 medications were prescribed to the study participants, with the median (IQR) medication prescribed per patient being six (8–5). Moreover, more than 85% of the patients were prescribed more than four medications (Table 1).

Assessment of PIM using STOPP criteria version 3

STOPP criteria version 3 identified 388 PIMs among the study participants (Table 2). More than 50% of the patients had encountered PIM. Of the 255 patients, 63.9% (n = 163) had at least one PIM, followed by 24.3% (n = 62) having two PIMs, 4.5% (n = 22) having three PIMs, and 2% (n = 5) and 1.2% (n = 3) having four and five PIMs, respectively. The prevalence of the PIMs among the study participants, hence, was found to be 56.6%.

First-generation antihistamines as a first-line treatment for allergy or pruritus was the most frequent PIM (STOPP criterion D24) and was identified in 9.8% of the patients. Subsequently, NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) if eGFR < 50 ml/min/1.73 m2 (risk of deterioration in renal function) (STOPP criterion E4) had the most reported PIM in approximately more than 8% of the patients. Conversely, opioids in the patients with a history of fall (criterion K7) and sodium glucose co-transporter (SGLT2) inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin) with symptomatic hypotension (criterion J4) were the least observed. Figure 1 represents the most commonly identified STOPP criteria.

In terms of PIMs identified by the physiological systems as mentioned in the STOPP criteria, the majority of the PIMs were reported from the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system (18.2%, n = 71), followed by the coagulation system (13.4%, n = 52). Figure 2 illustrates the system-wise occurrence of the PIMs.

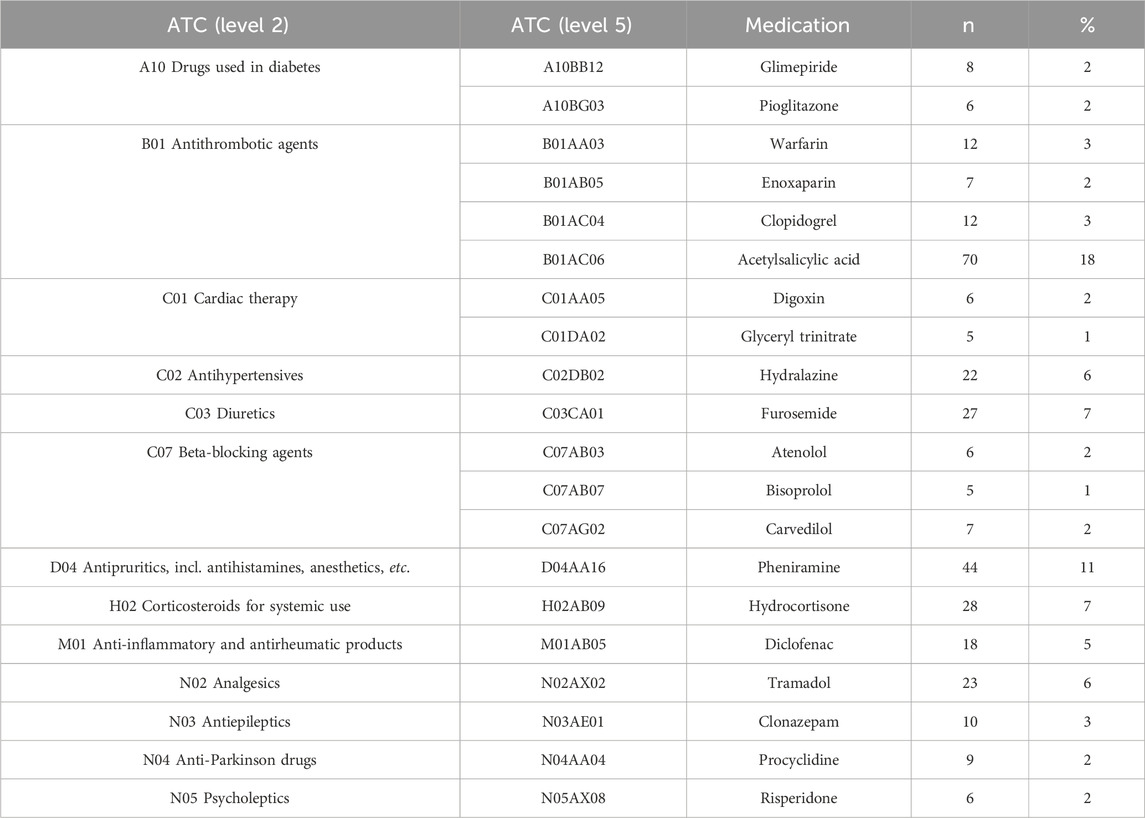

Of the total PIMs identified (n = 388), acetylsalicylic acid (B01AC06) (17%) was the most inappropriately prescribed, followed by pheniramine (R06AB05) (11%) and hydrocortisone (H02AB09) (7%). Table 3 highlights the twenty most frequently inappropriately prescribed medications as identified by the STOPP criteria.

Table 3. Top 20 medications being inappropriately prescribed by the STOPP criteria version 3 (n = 388).

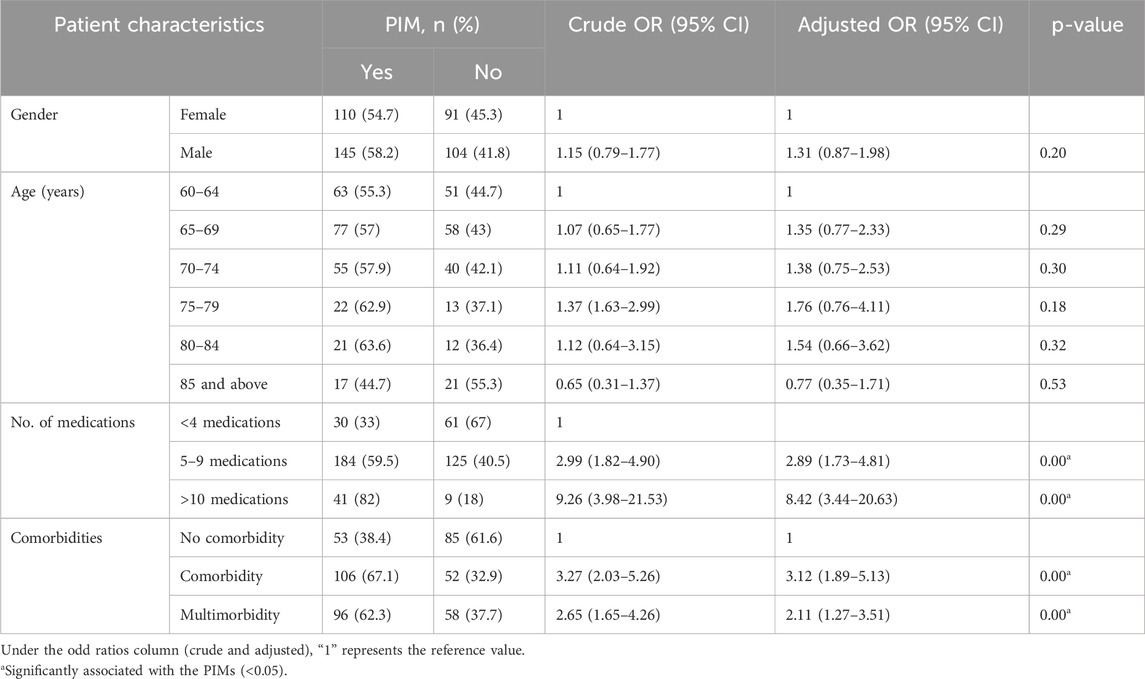

Factors associated with PIM according to STOPP criteria version 3

A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the factors associated with PIM according to STOPP criteria version 3 (Table 4). Among the participants, 54.7% of females and 58.2% of males were found to be using PIMs, and males were 1.31 times more prone to be using PIMs; however, the results were not significantly influenced (p = 0.20).

Age appeared to have a nuanced relationship with PIMs. Individuals aged 60–79 years showed higher odds of using PIMs, and this was not statistically significant (p = 0.18). In contrast, those aged 85 years and above had a lower likelihood of PIM use (adjusted OR = 0.77), suggesting that older age may not uniformly correlate with increased PIM usage.

A critical finding was the strong association between the number of medications taken and PIM use. Participants on 5–9 medications (adjusted OR = 2.89; 95% CI: 1.73–4.81) and those on more than 10 medications (adjusted OR = 8.42; 95% CI: 3.44–20.63) exhibited even higher odds of PIM use, and both were statistically significant (p < 0.001). This highlights the risk associated with polypharmacy in the older adults.

Similarly, the presence of comorbidities was significantly associated with PIM use. Individuals with comorbidities (adjusted OR = 3.12; 95% CI: 1.89–5.13) and those with multimorbidity (adjusted OR = 2.11; 95% CI: 1.27–3.51) indicated a strong association with the likelihood of being prescribed PIMs (p < 0.001). These results suggest that individuals with one or more comorbidities are significantly more likely to be prescribed PIMs.

Discussion

The present study is the first study conducted on the Pakistani older adults population to assess the prescription of inappropriate medications and its influencing factors in the older adults population using STOPP criteria version 3. A total of 450 patients aged 60 years and above were included in the study. Based on STOPP criteria version 3, more than 250 of the older adults patients were prescribed inappropriate medications, of which 63.9% (163) had been prescribed at least one PIM.

According to the STOPP criteria used in the study, the prevalence of PIMs in this study (56.6%) is consistent with findings from other research studies conducted in similar settings. For instance, a study by Mazhar et al. reported a prevalence of 64% in a similar demographic, reinforcing the notion that the older adults are particularly vulnerable to inappropriate prescribing practices due to polypharmacy and complex health needs (Mazhar et al., 2018). However, it is noteworthy that the PIMs in this study were identified using explicit STOPP criteria version 2 and the 2015 AGS Beers criteria. The data regarding inappropriate prescribing among the older adults in Pakistan are very scarce, and of the studies reported, very few have employed the STOPP criteria. The majority of the reported studies have employed the AGS Beers criteria (Chang et al., 2023; Sarwar et al., 2018). A study conducted in Larkana reported the prescribing of inappropriate medication in 22.6% of the patients using the 2015 AGS Beers criteria (Mangi et al., 2020). Comparatively, the findings of the present study are also consistent with those of the studies reported in the developed countries. A prospective cross-sectional study in Australia reported PIM prevalence to be 60% (Wahab et al., 2012). Similar prevalence rates were also reported in the studies conducted in Ireland, Brazil, and Israel (Hamilton et al., 2011; Nascimento et al., 2014; Frankenthal et al., 2013). However, some countries have also reported a lower prevalence rate, such as South Korea, Malaysia, and United Kingdom, ranging between 20.5% and 34.5% (Lee et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2012; Gallagher and O’Mahony, 2008). This variability may be attributed due to the presence of more robust systems for medication review, clinical decision support, and pharmacist involvement in medication management in these countries compared to those having high prevalence. This, ultimately, has a significant role in reducing inappropriate prescribing.

The findings of the present study report that 63.9% of the patients had received at least one PIM, which is very high in contrast to a study conducted on cardiac patients to identify PIM using the AGS Beer criteria, which reported that 26.4% patients received at least one PIM (Saqlain et al., 2020). Likewise, approximately 36.5% of the patients had at least one PIM in a study reported by Sarwar et al. The study was conducted in Lahore and, similar to the latter study, the 2015 AGS Beers criteria was used to assess the inappropriate prescribing (Sarwar et al., 2018).

The present finding is also alarming when compared to studies conducted other than in Pakistan, where the prevalence rate was reported to range from 35.4% to 55.4% (Awad and Hanna, 2019; Ryan et al., 2009; Abegaz et al., 2018). These prevalence rates have been evaluated using STOPP criteria version 1 and 2, respectively. This variation may be attributed to the utilization of version 3 of the STOPP criteria for the present study. STOPP criteria version 3 has an extended number of criteria. The comprehensiveness of version 3 is coupled with the evidence-based foundation; hence, it is more sensitive in detecting PIMs than its predecessors (Boland et al., 2023). This is also evident by the only study reported till date regarding the assessment of PIMs by STOPP criteria version 3. Similar to our findings, the study reported the detection of at least one PIM in 74% of the population compared to the 56% detected by version 2 of the STOPP criteria (Szoszkiewicz et al., 2024).

In terms of criterion, the most frequently reported criterion from the STOPP criteria was found to be prescribing of first-generation antihistamines for allergy or pruritus (9.8%). Of the first-generation antihistamines, pheniramine was the most inappropriately prescribed. Due to the strong significant anticholinergic effects of the first-generation antihistamines, they are considered potentially inappropriate and are recommended to be avoided in this vulnerable population by the American Geriatric Association (Cenzer et al., 2020). Moreover, second- and third-generation antihistamines are preferred for the management of allergy or pruritus in the older adults. Pheniramine is a first-generation antihistamine with significant anticholinergic effects. The STOPP criteria explicitly list first-generation antihistamines as PIMs, reflecting the consensus among geriatric experts regarding their risks in older adults patients. The results of the present study are in contrast with a similar study conducted in Taiwan, which reported a lower prevalence of antihistamine prescription in the older adults (Lai et al., 2009). This variability may be likely due to the use of different assessment tools, prescriber’s awareness regarding PIM, and the type of population being studied.

On the basis of physiological systems, the majority of the PIMs were reported from the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system (18.2%, n = 71), followed by the coagulation system (13.4%, n = 52). This finding is consistent with the known risks of medications such as NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, and antihypertensives in older adults patients with cardiovascular conditions, as well as the risks of anticholinergic drugs and benzodiazepines on cognitive function and fall risk. As a consequence, acetylsalicylic acid was found to be the most frequently inappropriately prescribed medication, followed by R06AB05 pheniramine. The high prevalence of acetylsalicylic acid as a PIM (17%) highlights the need for careful assessment of risk–benefit ratios in older adults patients in Pakistan. Although low-dose aspirin is often used for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events, its use in primary prevention is increasingly questioned, particularly in the older adults due to the risk of bleeding. In Pakistan, where access to advanced diagnostic and monitoring facilities may be limited, the risk of bleeding complications associated with the use of acetylsalicylic acid may be higher. The findings of the present study are consistent with the study reported in Malaysia, Belgium, and Portugal (Fahrni et al., 2019; Dalleur et al., 2012; Candeias et al., 2021). Compared to other studies (Parekh et al., 2019; Monteiro et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2024), benzodiazepines were not the most common PIM detected; however, clonazepam was found to be in the top ten medications being inappropriately prescribed in the present study.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis identified several independent factors significantly associated with PIM use. Notably, the number of medications prescribed emerged as a strong predictor. Prescribing of five or more medications was strongly associated with the increasing use of PIMs. In this study, over 85% of the participants were prescribed more than four medications, with a median of six medications per patient. This high rate of polypharmacy is consistent with that in previous research, indicating that the older adults often require complex medication regimens due to multiple comorbidities. This is evident by the study conducted in Austria where multimorbidity was the major risk factor for polypharmacy and, as a consequence, polypharmacy emerged in more than 50% of the patients (Schuler et al., 2008). Additionally, the risk of adverse effects is much higher in individuals with polypharmacy than in those prescribed fewer medications (Ahmed et al., 2014). Previous studies have also supported this finding and have emphasized the positive correlation of polypharmacy and PIMs (Steinman et al., 2006; Sayın et al., 2022; MacRae et al., 2021; Bhatt et al., 2019).

It can be a challenging task to prescribe in the older adults considering multiple diagnoses and the deterioration of their physiological conditions (Mangoni and Jackson, 2004; Milton et al., 2008). PIMs cannot be intervened without understanding the influence of comorbidity and multimorbidity on medication prescribing. In the present study, comorbidity and multimorbidity were remarkably associated with the use of PIMs. This is in agreement with the findings reported by Castillo-Páramo et al. (2014).

Although age-groups and gender were not significantly associated with the PIM use, it was found that males were more at risk to be prescribed inappropriate medications than females. This is in contrast to the previous findings where females were more likely to experience PIMs than males (Morgan et al., 2016; Bierman et al., 2007). Moreover, it is widely reported that increasing age is associated with increased risk of PIM (Zhu et al., 2024; Drusch et al., 2021). The same was observed in the present study; however, it was also observed that the risk of PIM use decreases in the individuals aged 85 years and above. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted in the United States (Jirón et al., 2016). Possible explanation for this variability in the present study could be the relatively small sample size in the age bracket of 85 years and above.

Limitations, strengths, and future directions

The present study provides valuable insights into PIM prevalence and the associated factors among older adults patients in Pakistan. However, it has limitations that warrant consideration. The observational design limits causal inferences regarding the relationships identified between the independent variables and PIM use. Furthermore, conducting the study at a single tertiary-care hospital may limit the generalizability of the findings to other health-care settings or regions within Pakistan.

Nevertheless, the study employed a prospective observational design, allowing for real-time data collection and minimizing recall bias, which is crucial in geriatric research. Furthermore, the use of STOPP criteria version 3 for identifying PIMs ensures that the assessment is based on established and validated guidelines tailored for the older adults. Last but not the least, the present study is the first that prospectively assessed inappropriate prescribing among the older adults in Pakistan using STOPP criteria version 3.

Future research should consider multicenter studies to capture a broader spectrum of prescribing practices across different health-care environments, especially in a country such as Pakistan. Longitudinal studies could also provide insights into how changes in medication regimens over time affect PIM prevalence and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The study’s findings highlight the alarmingly high rate of potentially inappropriate prescribing among the older adults population of Karachi, Pakistan. The findings highlight critical factors such as polypharmacy and comorbidity burden that contribute to this problem. Addressing these challenges through improved prescribing practices and systematic medication reviews will be essential for enhancing medication safety and overall health outcomes for the older adults in Pakistan. As the older adults population continues to grow, prioritizing appropriate pharmacotherapy will be crucial in mitigating risks associated with polypharmacy and ensuring better quality care for this vulnerable demographic.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jinnah University for Women (JUW/IERB/PHARM-ARA-013/2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HS: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing–original draft. SN: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, and writing–review and editing. HR: conceptualization, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing–review and editing. SJ: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, and writing–review and editing. HD: formal analysis, resources, and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the respondents for their contributions to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abegaz, T. M., Birru, E. M., and Mekonnen, G. B. (2018). Potentially inappropriate prescribing in Ethiopian geriatric patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disorders using START/STOPP criteria. PLoS ONE 13, e0195949. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195949

Abukhalil, A. D., Al-Imam, S., Yaghmour, M., Abushama, R., Saad, L., Falana, H., et al. (2022). Evaluating inappropriate medication prescribing among older adults patients in Palestine using the STOPP/START criteria. Clin. interventions aging 17, 1433–1444. doi:10.2147/CIA.S382221

Ahmed, B., Nanji, K., Mujeeb, R., and Patel, M. J. (2014). Effects of polypharmacy on adverse drug reactions among geriatric outpatients at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 9, e112133. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112133

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. (2015). American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63, 2227–2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702

Aubert, C. E., Streit, S., Da Costa, B. R., Collet, T. H., Cornuz, J., Gaspoz, J. M., et al. (2016). Polypharmacy and specific comorbidities in university primary care settings. Eur. J. Intern Med. 35, 35–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2016.05.022

Awad, A., and Hanna, O. (2019). Potentially inappropriate medication use among geriatric patients in primary care setting: a cross-sectional study using the Beers, STOPP, FORTA and MAI criteria. PLoS ONE 14, e0218174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218174

Bhatt, A. N., Paul, S. S., Krishnamoorthy, S., Baby, B. T., Mathew, A., and Nair, B. R. (2019). Potentially inappropriate medications prescribed for older persons: a study from two teaching hospitals in Southern India. J. Fam. Community Med. 26, 187–192. doi:10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_81_19

Bierman, A. S., Pugh, M. J. V., Dhalla, I., Amuan, M., Fincke, B. G., Rosen, A., et al. (2007). Sex differences in inappropriate prescribing among older adults veterans. Am. J. geriatric Pharmacother. 5, 147–161. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.06.005

Boland, B., Marien, S., Sibille, F.-X., Locke, S., Mouzon, A., Spinewine, A., et al. (2023). Clinical appraisal of STOPP/START version 3 criteria. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 14, 1149–1150. doi:10.1007/s41999-023-00839-1

Candeias, C., Gama, J., Rodrigues, M., Falcão, A., and Alves, G. (2021). Potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions in older adults patients receiving post-acute and long-term care: application of screening tool of older people’s prescriptions/screening tool to alert to right treatment criteria. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 747523. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.747523

Cassum, L. A., Cash, K., Qidwai, W., and Vertejee, S. (2020). Exploring the experiences of the older adults who are brought to live in shelter homes in Karachi, Pakistan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 20, 8. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1376-8

Castillo-Páramo, A., Clavería, A., Verdejo Gonzalez, A., Rey Gómez-Serranillos, I., Fernández-Merino, M. C., and Figueiras, A. (2014). Inappropriate prescribing according to the STOPP/START criteria in older people from a primary care setting. Eur. J. general Pract. 20, 281–289. doi:10.3109/13814788.2014.899349

Cenzer, I., Nkansah-Mahaney, N., Wehner, M., Chren, M. M., Berger, T., Covinsky, K., et al. (2020). A multiyear cross-sectional study of U.S. national prescribing patterns of first-generation sedating antihistamines in older adults with skin disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 182, 763–769. doi:10.1111/bjd.18042

Chang, C. T., Teoh, S. L., Rajan, P., and Lee, S. W. H. (2023). Explicit potentially inappropriate medications criteria for older population in Asian countries: a systematic review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 19, 1146–1156. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.05.017

Charlson, M. E., Carrozzino, D., Guidi, J., and Patierno, C. (2022). Charlson comorbidity index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 91, 8–35. doi:10.1159/000521288

Chen, L. L., Tangiisuran, B., Shafie, A. A., and Hassali, M. A. A. (2012). Evaluation of potentially inappropriate medications among older residents of Malaysian nursing homes. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 34, 596–603. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9651-1

Dalleur, O., Spinewine, A., Henrard, S., Losseau, C., Speybroeck, N., and Boland, B. (2012). Inappropriate prescribing and related hospital admissions in frail older persons according to the STOPP and START criteria. Drugs and aging 29, 829–837. doi:10.1007/s40266-012-0016-1

Díaz Planelles, I., Navarro-Tapia, E., García-Algar, Ó., and Andreu-Fernández, V. (2023). Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions according to the new STOPP/START criteria in nursing homes: a systematic review. Healthcare 11, 422. doi:10.3390/healthcare11030422

Drusch, S., Le Tri, T., Ankri, J., Zureik, M., and Herr, M. (2021). Decreasing trends in potentially inappropriate medications in older people: a nationwide repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 21, 621. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02568-1

Fahrni, M. L., Azmy, M. T., Usir, E., Aziz, N. A., and Hassan, Y. (2019). Inappropriate prescribing defined by STOPP and START criteria and its association with adverse drug events among hospitalized older patients: a multicentre, prospective study. PLoS ONE 14, e0219898. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219898

Frankenthal, D., Lerman, Y., Kalendaryev, E., and Lerman, Y. (2013). Potentially inappropriate prescribing among older residents in a geriatric hospital in Israel. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 35, 677–682. doi:10.1007/s11096-013-9790-z

Fulton, M. M., and Riley Allen, E. (2005). Polypharmacy in the older adults: a literature review. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 17, 123–132. doi:10.1111/j.1041-2972.2005.0020.x

Gallagher, P., and O’Mahony, D. (2008). STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill older adults patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing 37, 673–679. doi:10.1093/ageing/afn197

Hamilton, H., Gallagher, P., Ryan, C., Byrne, S., and O'Mahony, D. (2011). Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 171, 1013–1019. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215

Hanlon, J. T., and Schmader, K. E. (2013). The medication appropriateness index at 20: where it started, where it has been, and where it may be going. Drugs and aging 30, 893–900. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0118-4

Hudhra, K., García-Caballos, M., Casado-Fernandez, E., Jucja, B., Shabani, D., and Bueno-Cavanillas, A. (2016). Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescriptions identified by Beers and STOPP criteria in co-morbid older patients at hospital discharge. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 22, 189–193. doi:10.1111/jep.12452

Jirón, M., Pate, V., Hanson, L. C., Lund, J. L., Jonsson Funk, M., and Stürmer, T. (2016). Trends in prevalence and determinants of potentially inappropriate prescribing in the United States: 2007 to 2012. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 788–797. doi:10.1111/jgs.14077

Khatter, A., Moriarty, F., Ashworth, M., Durbaba, S., and Redmond, P. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of potentially inappropriate prescribing in middle-aged adults: a repeated cross-sectional study. Br. J. General Pract. 71, e491–e497. doi:10.3399/BJGP.2020.1048

Khezrian, M., McNeil, C. J., Murray, A. D., and Myint, P. K. (2020). An overview of prevalence, determinants and health outcomes of polypharmacy. Ther. Adv. drug Saf. 11, 2042098620933741. doi:10.1177/2042098620933741

Kojima, G., Bell, C., Tamura, B., Inaba, M., Lubimir, K., Blanchette, P. L., et al. (2012). Reducing cost by reducing polypharmacy: the polypharmacy outcomes project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 13, 818. e11–e15. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.019

Lai, H.-Y., Hwang, S.-J., Chen, Y.-C., Chen, T. J., and Chen, L. K. (2009). Prevalence of the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications at ambulatory care visits by older adults patients covered by the Taiwanese National Health Insurance program. Clin. Ther. 31, 1859–1870. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.08.023

Lavan, A. H., and Gallagher, P. (2016). Predicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 7, 11–22. doi:10.1177/2042098615615472

Lee, S.-J., Cho, S.-W., Lee, Y. J., Choi, J. H., Ga, H., Kim, Y. H., et al. (2013). Survey of potentially inappropriate prescription using STOPP/START criteria in Inha University Hospital. Korean J. Fam. Med. 34, 319–326. doi:10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.5.319

MacRae, C., Henderson, D. A., Mercer, S. W., Burton, J., De Souza, N., Grill, P., et al. (2021). Excessive polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in 147 care homes: a cross-sectional study. BJGP open 5. doi:10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0167

Mangi, A. A., Hammad, M. A., Khan, H., Arain, S. P., Shahzad, M. A., Dar, E., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the geriatric patients prescription for inappropriate medications frequency at Larkana Sindh Hospital in Pakistan. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 8, 1390–1394. doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.06.001

Mangoni, A. A., and Jackson, S. H. (2004). Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 6–14. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x

Mazhar, F., Akram, S., Malhi, S. M., and Haider, N. (2018). A prevalence study of potentially inappropriate medications use in hospitalized Pakistani older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 30, 53–60. doi:10.1007/s40520-017-0742-7

Milton, J. C., Hill-Smith, I., and Jackson, S. H. (2008). Prescribing for older people. Bmj 336, 606–609. doi:10.1136/bmj.39503.424653.80

Monteiro, C., Canário, C., Ribeiro, M. Â., Duarte, A. P., and Alves, G. (2020). Medication evaluation in Portuguese older adults patients according to beers, stopp/start criteria and EU (7)-PIM list–an exploratory study. Patient Prefer. adherence 14, 795–802. doi:10.2147/PPA.S247013

Morgan, S. G., Weymann, D., Pratt, B., Smolina, K., Gladstone, E. J., Raymond, C., et al. (2016). Sex differences in the risk of receiving potentially inappropriate prescriptions among older adults. Age Ageing 45, 535–542. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw074

Nascimento, M. M. G., Ribeiro, A. Q., Pereira, M. L., Soares, A. C., Loyola Filho, A. I. d., and Dias-Junior, C. A. C. (2014). Identification of inappropriate prescribing in a Brazilian nursing home using STOPP/START screening tools and the Beers' Criteria. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 50, 911–918. doi:10.1590/s1984-82502014000400027

O’Mahony, D., Cherubini, A., Guiteras, A. R., Denkinger, M., Beuscart, J. B., Onder, G., et al. (2023). STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 14, 625–632. doi:10.1007/s41999-023-00777-y

Organization, W. H., and Organization, W. H. (2000). Anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification index with defined daily doses (DDDs), 20. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.

Parekh, N., Ali, K., Davies, J. G., and Rajkumar, C. (2019). Do the 2015 Beers Criteria predict medication-related harm in older adults? Analysis from a multicentre prospective study in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 28, 1464–1469. doi:10.1002/pds.4849

Pourhoseingholi, M. A., Vahedi, M., and Rahimzadeh, M. (2013). Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from bed to bench 2013; 6. Hepatol. Bed Bench 6 (1), 14–17.

Ryan, C., O'Mahony, D., Kennedy, J., Weedle, P., and Byrne, S. (2009). Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish older adults population in primary care. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 68, 936–947. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03531.x

Saqlain, M., Ahmed, Z., Butt, S. A., Khan, A., Ahmed, A., and Ali, H. (2020). Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications use and associated risk factors among older adults cardiac patients using the 2015 American Geriatrics Society beers criteria. Drugs and Ther. Perspect. 36, 368–376. doi:10.1007/s40267-020-00747-5

Sarwar, M. R., Dar, A. R., Mahar, S. Y., Riaz, T., Danish, U., and Iftikhar, S. (2018). Assessment of prescribing potentially inappropriate medications listed in Beers criteria and its association with the unplanned hospitalization: a cross-sectional study in Lahore, Pakistan. Clin. interventions aging 13, 1485–1495. doi:10.2147/CIA.S173942

Sayın, Z., Sancar, M., Özen, Y., and Okuyan, B. (2022). Polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate prescribing and medication complexity in Turkish older patients in the community pharmacy setting. Acta Clin. Belg. 77, 273–279. doi:10.1080/17843286.2020.1829251

Scheen, A. (2014). Pharmacotherapy in the older adults: primum non nocere!. Rev. medicale Liege 69, 282–286.

Schuler, J., Dückelmann, C., Beindl, W., Prinz, E., Michalski, T., and Pichler, M. (2008). Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing in older adults internal-medicine patients in Austria. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 120, 733–741. doi:10.1007/s00508-008-1089-z

Steinman, M. A., Seth Landefeld, C., Rosenthal, G. E., Berthenthal, D., Sen, S., and Kaboli, P. J. (2006). Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 54, 1516–1523. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00889.x

Szoszkiewicz, M., Deskur-Śmielecka, E., Styszyński, A., Urbańska, Z., Neumann-Podczaska, A., and Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. (2024). Potentially inappropriate prescribing identified using STOPP/START version 3 in geriatric patients and comparison with version 2: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 13, 6043. doi:10.3390/jcm13206043

Topinková, E., Baeyens, J. P., Michel, J.-P., and Lang, P. O. (2012). Evidence-based strategies for the optimization of pharmacotherapy in older people. Drugs and aging 29, 477–494. doi:10.2165/11632400-000000000-00000

Wahab, M. S. A., Nyfort-Hansen, K., and Kowalski, S. R. (2012). Inappropriate prescribing in hospitalised Australian older adults as determined by the STOPP criteria. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 34, 855–862. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9681-8

Keywords: older adults, Pakistan, STOPP criteria version 3, polypharmacy, multimorbidity

Citation: Sadia H, Naveed S, Rehman H, Jamshed S and Dilshad H (2025) Enhancing medication appropriateness: Insights from the STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions) criteria version 3 on prescribing practices among the older adults in Pakistan. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1551819. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1551819

Received: 06 January 2025; Accepted: 26 February 2025;

Published: 20 May 2025.

Edited by:

Peter Crome, Keele University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Natasa Duborija-Kovacevic, University of Montenegro, MontenegroMuhammad Junaid Farrukh, UCSI University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Sadia, Naveed, Rehman, Jamshed and Dilshad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Halima Sadia, aGFsaW1hc2FkaWEwOTNAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Halima Sadia, orcid.org/0000-0001-6669-2458

Halima Sadia

Halima Sadia Safila Naveed

Safila Naveed Hina Rehman

Hina Rehman Shazia Jamshed

Shazia Jamshed Huma Dilshad

Huma Dilshad