Abstract

Objective:

To systematically evaluate the efficacy and safety of specific external traditional Chinese medicine therapies (SETCM therapies) versus conventional non-SETCM therapy interventions for improving swallowing function, nutritional status, and reducing complications in adult patients with post-stroke dysphagia (PSD), based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods:

A comprehensive search was conducted from inception to present across Chinese [(China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform (WFSD), Chinese Biology Medicine Database (CBM)] and international databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library). RCTs investigating validated SETCM therapy modalities (e.g., herbal patches, iontophoresis, compresses, and fumigation) for PSD were included. All herbal components were taxonomically validated using the Kew Medicinal Plant Names Service (MPNS). The control group received conventional therapy (rehabilitation, nursing, and medication). The experimental group received SETCM therapies alone or combined with conventional care. The risk of bias in eligible studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. A meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4. Stratified subgroup analyses were conducted based on stroke lesion location (supratentorial vs. brainstem) and intervention type.

Results:

Twenty-five RCTs (n = 2,159 patients; SETCM therapies group = 1,152, control group = 1,007) were included. The meta-analysis demonstrated significantly greater benefits in the SETCM therapies group for: overall response rate (OR = 3.28, 95% CI [2.49, 4.31]); overall cure rate (OR = 2.36, 95% CI [1.84, 3.02]); water swallowing test (WST) score (MD = −0.65, 95% CI [−1.23, −0.06]); and SWAL-quality-of-life (SWAL-QOL) score (MD = 25.61, 95% CI [20.54, 30.67]). The SETCM therapies group also demonstrated superior results in videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) scores, modified Barthel index (MBI), serum albumin (ALB), prealbumin (PA), gugging swallowing screen (GUSS), activities of daily living (ADL), and functional dysphagia scale (FDS) scores, nasogastric tube removal success rate, as well as lower Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) scores, reduced aspiration incidence, and shorter nasogastric tube indwelling time. Safety analysis (three studies) reported mild skin irritation (erythema and pruritus) in 2.1% of cases.

Conclusion:

SETCM therapies significantly improved swallowing function, nutritional status, and clinical outcomes in patients with PSD. Efficacy exhibited neuroanatomical specificity: Acupoints are preferred for cerebral hemisphere lesions, while herbal iontophoresis is the best choice for brainstem involvement. These findings support the integration of targeted SETCM therapies into PSD rehabilitation. However, the evidence is limited by methodological biases, necessitating high-quality RCTs for confirmation.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier CRD42024599344.

1 Introduction

Stroke, a prevalent neurological disorder resulting from the narrowing, obstruction, or rupture of cerebral blood vessels, is characterized by high morbidity and severe sequelae, significantly impairing patients’ quality of life (Dou, 2009). Among its complications, post-stroke dysphagia (PSD) ranks as one of the most frequent (Martino et al., 2005), with an incidence rate as high as 81% (Alamer et al., 2020). Crucially, a history of stroke is a well-established risk factor for dysphagia (Mourão et al., 2016). Although approximately 60% of patients regain partial swallowing function within 3 months, 11%–50% exhibit persistent dysfunction at 6 months (Song et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2020). This dysfunction is closely associated with impaired respiratory function (Song et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2020), increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia by 3.8-fold and mortality by 11%–16% (Umay et al., 2022; Chang et al., 2022), thereby hindering rehabilitation (Han et al., 2020).

Current modern medical treatments for PSD primarily include oral sensory stimulation training, oral motor exercises, and physical therapy (Hui and Zhang, 2025). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has accumulated extensive experience in managing PSD, achieving favorable outcomes through methods such as swallowing rehabilitation training, oral herbal medicine administration, and acupoint pressure/massage. Although diverse therapeutic approaches for dysphagia exist, the clinical effectiveness of their individual or combined application remains unclear (Yang and Do, 2022). Furthermore, the high cost of treatment imposes a substantial burden on families and the healthcare system (Qureshi et al., 2022).

Consequently, identifying an economical, convenient, effective, and clinically feasible treatment modality capable of enhancing swallowing ability, improving nutritional intake, reducing complications, and facilitating recovery in PSD patients holds significant practical importance. In recent years, guided by TCM meridian theory and the concepts of Qi and blood, and integrated with modern medical technology, research exploring the mechanisms of transdermal drug delivery via acupoints has gained momentum. Specific external traditional Chinese medicine therapies (SETCM therapies), recognized as noninvasive and safe interventions, have consequently garnered increasing attention, offering novel perspectives for PSD rehabilitation (Zheng et al., 2024; Li, 2023). SETCM therapies refer to standardized interventions using pharmacopeia-defined herbal formulations applied via specific modalities (e.g., patching and iontophoresis) at anatomically targeted sites. High-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating SETCM therapies for PSD have emerged, progressively focusing on evaluating their efficacy. However, this specific dimension has not been adequately explored in previous meta-analyses, highlighting an urgent need to synthesize the latest evidence using evidence-based medicine (EBM) methodologies.

Therefore, this systematic review assessed RCTs comparing SETCM therapy interventions with non-SETCM therapy controls in adult PSD patients, with a focus on swallowing function, nutritional status, and complications. The aims were to provide more reliable EBM evidence for clinical practice, explore the potential clinical utility of SETCM therapies in PSD management, and thereby offer valuable references for clinicians and rehabilitation therapists.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study registration

This study adhered to international guidelines for conducting and reporting meta-analyses concerning the selection and utilization of research methodologies. The study protocol was prospectively registered on the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/), registration number CRD42024599344.

2.2 Literature search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across eight electronic databases. Chinese literature databases included China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Biology Medicine disc (SinoMed/CBM), VIP Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), and Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform (WFSD). International literature databases included PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The search aimed to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating specific external traditional Chinese medicine (SETCM) therapy interventions for post-stroke dysphagia (PSD). The search timeframe generally spanned from the inception of each database to the latest available date to ensure the inclusion of the most recent research. Search terms incorporated both medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text words in Chinese and English: Dysphagia: (“Dysphagia” OR “Swallowing Disorders” OR “Deglutition Disorders” OR “Pseudobulbar Palsy” OR “Oropharyngeal Dysfunction”) Stroke: (“Stroke” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident” OR “Brain Infarction” OR “Cerebral Embolism” OR “Cerebral Ischemia”) SETCM therapy interventions: (“External Traditional Chinese Medicine” OR “Chinese Herbal Patch” OR “Iontophoresis” OR “Hot Compress” OR “Cold Compress” OR “Fumigation” OR “Herbal Steam” OR “Herbal Wash”).

Search strategies utilized Boolean operators (AND, OR), wildcards, and proximity operators where appropriate, combining MeSH terms and free-text keywords. Manual searches of relevant specialized journals and efforts to locate unpublished studies (grey literature) were also performed when necessary.

2.3 Definition, component standardization, and taxonomic validation of SETCM therapy interventions

SETCM therapies are standardized interventions using pharmacopeia-defined herbal formulations applied via specific methods (e.g., patching and iontophoresis) to anatomically defined target sites (typically acupoints). For all included primary studies, detailed information regarding the specific SETCM therapy interventions (including, but not limited to, herbal patching, iontophoresis, fumigation, and medicated stick application) was systematically extracted and re-examined. This encompassed the botanical components, preparation methods, and quality control standards (where mentioned). The botanical names of all reported medicinal plant species were subjected to systematic taxonomic validation using authoritative international databases (Rivera et al., 2014). The Consensus on Phytovigilance for Medicinal Plants (ConPhyMP) tool was employed to evaluate all included studies (Heinrich et al., 2018). This assessment covered: botanical names (scientific name, family, and genus), the plant parts used, functional components, pharmacological effects, mechanism of action, etc.

2.4 Literature inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.4.1 Inclusion criteria

2.4.2 Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

(1) Dysphagia caused by other underlying conditions (e.g., neurological disorders, head/neck cancer, or congenital abnormalities);

(2) Animal studies, case reports, conference abstracts, reviews, or non-research articles;

(3) Studies where the full text was unavailable or original data were incomplete/unrecoverable;

(4) Studies with major methodological flaws (e.g., lack of randomization and absence of a control group) or meeting any of the following conditions:

a. “High risk” of bias: Studies rated as “high risk” in ≥2 key domains (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding) using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool;

b. Insufficient data integrity: Missing data for critical outcome measures where authors could not be contacted for clarification.

(Note: Studies rated as “unclear risk” in only one domain (e.g., allocation concealment) were retained due to the current limited availability of high-quality RCTs in the PSD field. The potential influence of these studies on conclusions was assessed via sensitivity analysis.)

(5) Patients with psychiatric disorders or severe communication barriers affecting informed consent;

(6) Studies lacking predefined primary/secondary outcomes or employing non-standardized assessment tools;

(7) Studies involving duplicate publication or overlapping datasets with prior publications.

2.5 Literature screening and data extraction

Literature screening: Two independent researchers performed the literature search and initial screening based on the predefined search strategy. EndNote 20 was used for reference management (including import, organization, merging, and deduplication). Initial screening involved excluding clearly irrelevant records based on titles and abstracts. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were then retrieved and scrutinized to determine eligibility. Attempts were made to contact authors for missing data from potentially eligible studies; studies were excluded if no response was received. Results from both initial and full-text screening underwent cross-checking by both researchers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer.

Data extraction: Extracted data encompassed: (1) basic study information (authors, year, and journal); (2) patient baseline characteristics (sample size, age, gender, stroke type/location, and time since stroke); (3) intervention details (SETCM therapy type, specific herbs/formulations [validated taxonomically], preparation, dosage, frequency, duration, and concurrent therapies); (4) control intervention details; (5) outcome measures (primary and secondary, as defined in Table 1, including measurement time points and scales used); and (6) quality assessment data. To standardize efficacy assessment, the end of the intervention period was selected as the primary observation endpoint. Continuous outcome data were recorded as mean ± standard deviation ( 7± s). Missing data were requested from the original authors; if unavailable, they were documented as missing.

TABLE 1

| PICOS | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Adult patients (>18 years old) diagnosed with post-stroke dysphagia (PSD) according to established diagnostic criteria (e.g., criteria from the 4th National Cerebrovascular Disease Conference), with stroke confirmed by CT or MRI |

| Intervention | Experimental group receiving validated external traditional Chinese medicine therapies (SETCM therapies) alone (e.g., herbal patching, TCM iontophoresis, hot compress, fumigation, fumigation-wash, wash-soak, herbal hot compress, cold compress) or SETCM therapies combined with conventional care |

| Comparison | Control group receiving non-SETCM therapy interventions: conventional therapy (e.g., medication), conventional nursing care, or conventional rehabilitation training |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Overall response rate (defined as the percentage of cases achieving comprehensive cure, marked improvement, or improvement); Cure rate (defined as the percentage of cases achieving cure status); Water swallowing test (WST) score; Swallow quality-of-life questionnaire (SWAL-QOL) score; Complication incidence rate. Secondary outcomes: Videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) score; Modified Barthel index (MBI) score; Gugging swallowing screen (GUSS) score; Activities of daily living (ADL) score; Nasogastric tube indwelling duration; Feeding tube removal success rate; Nutritional risk screening 2002 (NRS 2002) score; Fujishima dysphagia scale (FDS) score; Nutritional biomarkers: Serum albumin (ALB), Prealbumin (PA); Safety data: Incidence of skin reactions/systemic adverse events |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) |

PICOS strategy—inclusion criteria.

Note: P: population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome; S: study design; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

2.6 Assessment of methodological quality (risk of bias)

The methodological quality (risk of bias) of included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 2) for randomized trials. The assessment comprised two parts. In the Descriptive assessment, Detailed descriptions of study methodology relevant to each bias domain were recorded to support the judgment of risk. In the Judgment of Risk assessment, each domain was judged as “Low risk,” “High risk,” or “Unclear risk” of bias.

The specific bias domains evaluated were: Selection Bias: Random sequence generation, Allocation concealment; Performance Bias: Blinding of participants and personnel; Detection Bias: Blinding of outcome assessment; Attrition Bias: Incomplete outcome data; Reporting Bias: Selective outcome reporting; Other Bias: Any other potential sources of bias not covered above.

Disagreements in judgments were resolved through consensus discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of the extracted outcome data were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.4.1, provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. Heterogeneity among studies for each clinical outcome was assessed using the chi2 test (Q statistic) and quantified using the I2 statistic. A significance level of P > 0.10 for the chi2 test indicated acceptable heterogeneity, warranting the use of a fixed-effects model (FEM) for meta-analysis. Conversely, a chi2 test result of P ≤ 0.10 indicated significant heterogeneity, leading to the use of a random-effects model (REM) for meta-analysis. The magnitude of heterogeneity was interpreted based on I2 values: I2 ≤ 25% indicated low heterogeneity, I2 > 50% indicated moderate heterogeneity, and I2 > 75% indicated substantial heterogeneity. Where significant heterogeneity was present, sensitivity analyses were conducted using the study removal method to identify potential sources and exclude studies contributing excessively to heterogeneity. For continuous outcomes, results were pooled using the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk (RR) with 95% CI was used. Results were presented using forest plots. Publication bias was assessed visually using inverted funnel plots plotting the RR (for dichotomous outcomes) or SMD (for continuous outcomes) against its standard error (SE). Two predefined subgroup analyses were performed: (a) stratified by SETCM therapy intervention type (herbal patching, TCM iontophoresis, medicated stick application); and (b) stratified by stroke lesion location (supratentorial [cerebral hemisphere] vs. brainstem). Studies not reporting specific lesion location were excluded from the latter subgroup analysis.

2.8 GRADE assessment of evidence quality

Two independent researchers assessed the quality of evidence (certainty) for each outcome measure using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Guyatt et al., 2011). Assessments were conducted using the online GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT; https://gradepro.org). The quality of evidence for each outcome was downgraded based on five domains: Risk of bias across included studies; Inconsistency: Unexplained heterogeneity in results; Indirectness: Indirectness of population, intervention, comparator, or outcome; Imprecision: Wide confidence intervals or small sample size; Publication bias: Evidence of publication bias. The initial quality rating for RCTs is “High.” Evidence quality was then categorized as High: No downgrading (we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate); Moderate: Downgraded by one level (we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely close to the estimate, but there is a possibility of being substantially different); or Low: Downgraded by two levels (our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate). Very low: Downgraded by three levels (we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely substantially different from the estimate).

Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening results and characteristics of included studies

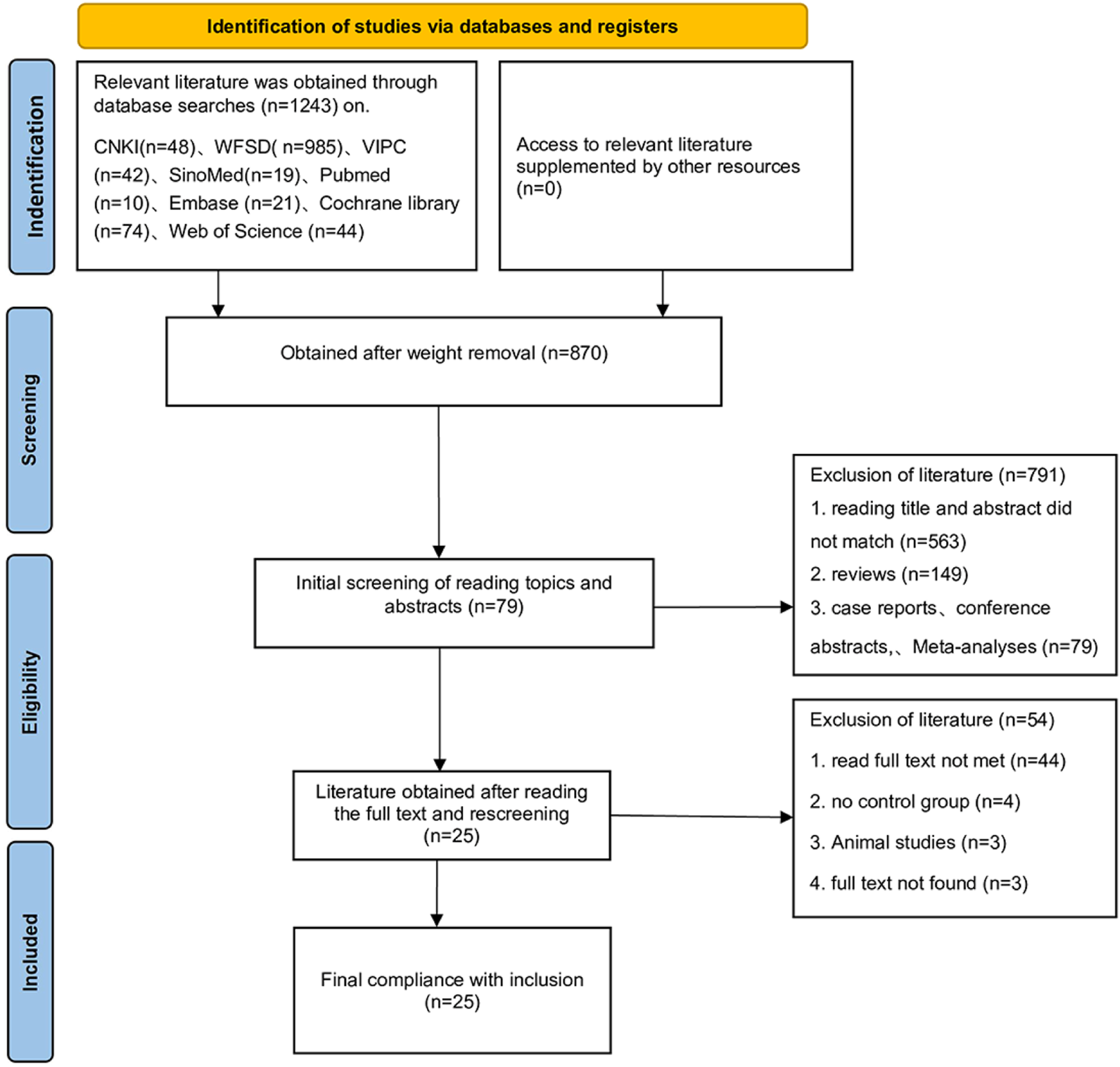

The initial search identified 1,243 potentially relevant records. After removing 373 duplicate publications, 870 unique records remained. Screening of titles and abstracts excluded 791 records, leaving 79 articles for full-text assessment. Following full-text review, 54 articles were excluded, resulting in the final inclusion of 25 published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The study selection process is detailed in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2. These 25 RCTs enrolled a total of 2,245 participants. Regarding the specific SETCM therapy modalities employed: 16 studies utilized acupoint herbal patching, two studies utilized herbal fumigation, two studies utilized TCM iontophoresis, two studies utilized medicated herbal stick application, and two studies utilized acupoint stimulation with herbal ice-cotton swabs. One study utilized targeted drug delivery therapy. Concerning the intervention durations: 15 studies implemented an intervention period of approximately 4 weeks, six studies implemented an intervention period of 3 weeks, and four studies implemented an intervention period of 2 weeks. The results of the included studies indicated that there were no significant differences in baseline measure scores between the experimental (SETCM therapies) and control groups across all studies (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, outcome measure scores improved significantly compared to baseline within both groups (P < 0.05). The improvement observed in the experimental (SETCM therapies) group was significantly greater than that in the control group (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flow chart.

TABLE 2

| Author(s) | Year | Sample size | Age | Days | Outcome indicator | Intervention measures | Stroke location | Herbal medicine used | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | Operational area | ||||||||

| Tang and Liu (2024) | 2024 | 34/34 | 64.18 ± 8.09/64.28 ± 8.14 | 30 days | ⑥⑪ ⑫ ⑬ ⑭ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Yu and Wu (2024) | 2024 | 75/75 | 45–78/42–80 | 28 days | ①②④⑤ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Supratentorial | Pinelliae Rhizoma Praeparatum,Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Notoginseng Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Asari Radix et Rhizoma |

| Wang and Sun (2023) | 2023 | 15/15 | 58–82/59–80 | 28 days | ③⑤⑦⑧⑨ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus, Borneolum Syntheticum |

| Zhu et al. (2023) | 2023 | 32/32 | 77.72 ± 7.87/80.75 ± 6.77 | 21 days | ①② | targeted transdermal medication+ rehabilitation |

Rehabilitation | Dazhui point and Shenshu point | Supratentorial | Rehmanniae Radix Praeparata, Morindae Officinalis Radix, Corni Fructus, Dendrobii Caulis, Cistanches Herba, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Schisandrae Chinensis Fructus, Cinnamomi Cortex, Poria, Ophiopogonis Radix, Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Polygalae Radix |

| Yu and Qiu (2023) | 2023 | 40/40 | 54–77/53–77 | 30 days | ⑥⑪ ⑬ ⑭ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Wang et al. (2023b) | 2023 | 50/50 | 20–75/20–75 | 14 days | ①②③④ | Acupoint application + medication | Medication | Renying point, Lianquan point, and Fengfu point | Supratentorial | Persicae Semen, Carthami Flos, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Paeoniae Radix Rubra, Rehmanniae Radix, Scrophulariae Radix, Platycodonis Radix, Aurantii Fructus, Borneolum Syntheticum, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma |

| Xu (2022) | 2022 | 60/60 | 45–93/46–93 | 30 days | ⑪ ⑬ ⑭ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Shi et al. (2022) | 2022 | 66/66 | 46–74/43–73 | 30 days | ①②⑫ | Herbal fumigation + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | neck | Unspecified | Cinnamomi Cortex, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma, Poria, Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma, Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix, Eucommiae Cortex, Rehmanniae Radix, Chuanxiong Rhizoma, Paeoniae Radix Rubra, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Saposhnikoviae Radix, Gentianae Macrophyllae Radix, Taxilli Herba |

| Zhou et al. (2022) | 2022 | 75/75 | 33–69/32–65 | 21 days | ①②③④ | Acupoint application + conventional treatment+ rehabilitation |

Conventional treatment + rehabilitation | Renying point, Lianquan point, and Fengfu point | Supratentorial | Persicae Semen, Carthami Flos, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Paeoniae Radix Rubra, Rehmanniae Radix, Scrophulariae Radix, Platycodonis Radix, Aurantii Fructus, Borneolum Syntheticum, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma |

| Jiao (2022) | 2022 | 40/40 | 53–73/52–74 | 28 days | ③⑤⑥ | Acupoint application + conventional treatment | Conventional treatment | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Wu et al. (2021) | 2021 | 40/40 | 47–83/46–81 | 30 days | ①⑧⑩ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Dong et al. (2021) | 2021 | 46/46 | 52–78/51–79 | 28 days | ①⑧⑨ | Acupoint application + conventional treatment+ rehabilitation |

Conventional treatment +rehabilitation |

Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Shao and Chen (2020) | 2020 | 53/53 | 40–79/41–77 | 28 days | ①②③④⑪ | Herbal medicine stick treatment + conventional treatment | Conventional treatment | Posterior palatal arch, soft palate, pharyngeal palatal arch, posterior pharyngeal wall, and root of tongue | Supratentorial | Moschus, Menthae Haplocalycis Herba, Styrax, Borneolum Syntheticum |

| Zheng et al. (2019) | 2019 | 42/42 | 62.6 ± 7.5/63.4 ± 7.9 | 14 days | ①②③ | Acupoint application + electrical stimulation+ rehabilitation |

Electrical stimulation + rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, Lianquan point, and Futu point | Supratentorial | Moschus, Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma, Styrax, Bovis Calculus, Bufonis Venenum, Cinnamomi Cortex, Borneolum Syntheticum |

| Hu (2019) | 2019 | 61/61 | 65.3 ± 12.2/65.3 ± 12.2 | 30 days | ①②③④⑤⑦⑧⑨⑩ | Acupoint application + conventional treatment | Conventional treatment | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Zhou et al. (2018) | 2018 | 40/40 | 36–72/38–70 | 21 days | ①③④ | Herbal medicine stick treatment + conventional treatment | Conventional treatment | Herbal medicine stick treatment + conventional treatment | Brainstem | Bombyx Batryticatus, Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Moschus, liquor |

| Luo et al. (2018) | 2018 | 35/35 | 43–82/39–85 | 14 days | ①②④ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Lianquan point | Supratentorial | Kansui Radix, Sinapis Semen, Ephedrae Herba, Asari Radix et Rhizoma |

| Ma et al. (2021) | 2018 | 55/55 | 64.3 ± 11.2/63.5 ± 11.4 | 20 days | ①②③④⑤⑮ | Acupoint application + conventional treatment +rehabilitation |

Conventional treatment + rehabilitation | Lianquan point, Bilateral Gongxue points, and Bilateral Renying points | Unspecified | Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Notoginseng Radix et Rhizoma Pulvis |

| Xu and Zhao (2016) | 2016 | 33/33 | 35–77/34–75 | 28 days | ①② | Herbal fumigation + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Neck | Unspecified | Cinnamomi Cortex, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma, Poria, Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma, Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix, Eucommiae Cortex, Rehmanniae Radix, Chuanxiong Rhizoma, Paeoniae Radix Rubra, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Saposhnikoviae Radix, Gentianae Macrophyllae Radix, Taxilli Herba |

| Que and Bian (2016) | 2016 | 43/43 | 66.88 ± 12.33/65.93 ± 12.61 | 20 days | ①②③ | Herbal medicine stick Treatment + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Both palatal arches, posterior pharyngeal wall, posterior root of the tongue, Jinjin points, and Yuyi points | Mixed | Pheretima, Carthami Flos, Liquidambaris Fructus, Menthae Haplocalycis Herba, Borneolum Syntheticum |

| Lai (2015) | 2015 | 50/50 | 44–75/45–72 | 30 days | ① | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Fengchi point, Hegu point, and Jinjin point |

Unspecified | Astragali Radix, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Paeoniae Radix Rubra, Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma, Chuanxiong Rhizoma, Carthami Flos, Persicae Semen, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma |

| Lin et al. (2014) | 2014 | 30/29 | 60.47 ± 8.07/61.10 ± 9.23 | 30 days | ①②⑤ | Herbal medicine stick treatment + medication+ rehabilitation |

Medication + rehabilitation | Uvula, bilateral palatopharyngeal arches, soft palate, and posterior root of tongue | Brainstem | Arisaema Praeparatum, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Citri Exocarpium Rubrum, Bambusae Caulis in Taenias, Persicae Semen, Aurantii Fructus Immaturus, Carthami Flos, Poria, Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma |

| Zhao et al. (2012) | 2012 | 23/23 | 35–84/35–84 | 30 days | ①⑮ | Acupoint application + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Tiantu point, Renying point, and Lianquan point | Unspecified | Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, Pinelliae Rhizoma, Arisaematis Rhizoma Preparatum, Borneolum Syntheticum, Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus |

| Zhao et al. (2008) | 2008 | 35/35 | 48–69/50–68 | 20 days | ①② | TCM iontophoresis + rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Lianquan point, Tiantu point, Fengfu point, Fengchi point, Yifeng point, and Hegu point |

Brainstem | Moschus, Borneolum Syntheticum |

| Huang (2007) | 2007 | 50/50 | 45–74/40–75 | 15 days | ④ | TCM iontophoresis + medication | Medication | Fengfu point, Lianquan point | Brainstem | - |

Baseline characteristics of included studies and details of SETCM therapy interventions.

Notes:

Outcomes assessed: ① Overall response rate; ② Cure rate; ③ Water swallowing test (WST) score; ④ Videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) score; ⑤ Swallow quality-of-life questionnaire (SWAL-QOL) score; ⑥ Post-intervention aspiration rate; ⑦ Modified Barthel index (MBI) score; ⑧ Serum albumin (ALB); ⑨ Prealbumin (PA); ⑩ Nutritional risk screening 2002 (NRS 2002) score; ⑪ Gugging swallowing screen (GUSS) score; ⑫ Activities of daily living (ADL) score; ⑬ Nasogastric tube indwelling duration; ⑭ Feeding tube removal success rate; ⑮ Fujishima dysphagia scale (FDS) score. (See main text for abbreviation definitions).

Stroke lesion location classification:

Supratentorial: Lesions involving cortical/subcortical structures.

Brainstem: Lesions involving medullary/pontine structures.

Mixed/Unspecified: Excluded from lesion location-based efficacy analysis.

3.2 Development of a standardized SETCM therapy intervention database

This study successfully established a standardized database for specific external traditional Chinese medicine therapy (SETCM therapy) interventions. Specifically, through authoritative databases (MPNS v7.3+, POWO) and the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 Edition), rigorous taxonomic validation and name standardization were performed on all medicinal plant species reported in the primary studies, ensuring the accuracy of the botanical origins of the herbs used. These validation results have been compiled and summarized in Table 3: Standardized botanical information.

TABLE 3

| Medicinal Material (Chinese) | Latin name (ChP 2020) | Citrus | Specific Epithet | Named person's initials | Family | Part used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajitian | Morindae Officinalis Radix | Morinda | officinalis | How | Rubiaceae | Dried root (Radix) |

| Fuzi | Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata | Aconitum | carmichaelii | Debx. | Ranunculaceae | Processed daughter root |

| Jiangcan | Bombyx Batryticatus | Bombyx | mori | Linnaeus | Bombycidae | Dried larva killed by Beauveria bassiana |

| Jiezi | Sinapis Semen | Sinapis | alba | L. (Carl Linnaeus) | Brassicaceae | Dried ripe seed (Semen) |

| Bingpian | Borneolum Syntheticum | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Synthetic | Crystalline product from Cinnamomum branches |

| Bohe | Menthae Haplocalycis Herba | Mentha | haplocalyx | Briq. | Lamiaceae | Dried aerial part (Herba) |

| Baizhu | Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma | Atractylodes | macrocephala | Koidz. | Asteraceae | Dried rhizome (Rhizoma) |

| Chuanxiong | Chuanxiong Rhizoma | Ligusticum | chuanxiong | Hort. | Apiaceae | Dried rhizome (Rhizoma) |

| Chuanbeimu | Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus | Fritillaria | cirrhosa | D.Don | Liliaceae | Dried bulb (Bulbus) |

| Dannanxing | Arisaema cum Bile | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Araceae | Bile-processed tuber of Arisaema |

| Dilong | Pheretima | Pheretima | aspergillum | (E.Perrier) | Megascolecidae | Eviscerated dried body (Lumbricus) |

| Dihuang | Rehmanniae Radix | Rehmannia | glutinosa | Libosch. | Scrophulariaceae | Dried root tuber (Radix) |

| Duzhong | Eucommiae Cortex | Eucommia | ulmoides | Oliv. | Eucommiaceae | Dried bark (Cortex) |

| Fangfeng | Saposhnikoviae Radix | Saposhnikovia | divaricata | (Turcz.)Schischk. | Apiaceae | Dried root (Radix) |

| Fuling | Poria | Poria | cocos | (Schw.) Wolf | Polyporaceae | Dried sclerotium (Sclerotium) |

| Fuzi | Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata | Aconitumm | carmichaelii | Debx. | Ranunculaceae | Dried daughter root (Radix Aconiti Lateralis) |

| Gansui | Kansui Radix | Euphorbia | kansui | T.N.Liou ex T.P.Wang | Euphorbiaceae | Dried root tuber (Radix) |

| Gancao | Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma | Glycyrrhiza | uralensis | Fisch. | Fabaceae | Dried root and rhizome (Radix et Rhizoma) |

| Honghua | Carthami Flos | Carthamus | tinctorius | L.(Carl Linnaeus) | Asteraceae | Dried flower (Flos) |

| Huangqi | Astragali Radix | Astragalus | membranaceus | (Fisch.) Bge. | Fabaceae | Dried root (Radix) |

| Jiegeng | Platycodonis Radix | Platycodon | grandiflorum | (Jacq.)A.DC. | Campanulaceae | Dried Root (Radix Platycodi) |

| Juhong | Citri Exocarpium Rubrum | Citrus | reticulata | Blanco | Rutaceae | Dried Pericarp (Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae) |

| Lulu tong | Liquidambaris Fructus | Liquidambar | formosana | Hance | Hamamelidaceae | Dried Resin (Resina Liquidambaris) |

| Mahuang | Ephedrae Herba | Ephedra | sinica | Stapf | Ephedraceae | Dried Herbaceous Stem (Herba Ephedrae) |

| Maidong | Ophiopogonis Radix | Ophiopogon | japonicus | (L. f.) Ker-Gawl. | Liliaceae | Dried Root Tuber (Radix Ophiopogonis) |

| Niuxi | Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix | Achyranthes | bidentata | Bl. | Amaranthaceae | Dried Root (Radix Achyranthis) |

| Qinjiao | Gentianae Macrophyllae Radix | Gentiana | macrophylla | Pall. | Gentianaceae | Dried Root (Radix Gentianae) |

| Renshen | Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma | Panax | ginseng | C.A.Mey. | Araliaceae | Dried Root (Radix Ginseng) |

| Roucongrong | Cistanches Herba | Cistanche | deserticola | Y.C.Ma | Orobanchaceae | Dried Fleshy Stem with Scales (Herba Cistanches) |

| Rougui | Cinnamomi Cortex | Cinnamomum | cassia | Presl | Lauraceae | Dried Bark (Cortex Cinnamomi) |

| Sanqi | Notoginseng Radix et Rhizoma | Panax | notoginseng | (Burk.) F. H. Chen | Araliaceae | Dried Root (Radix Notoginseng) |

| Sangjisheng | Taxilli Herba | Taxillus | chinensis | (DC.)Danser | Loranthaceae | Dried Stem with Leaves (Ramulus Taxilli) |

| Shanzhuyu | Corni Fructus | Cornus | officinalis | Sieb. et Zucc. | Cornaceae | Dried Flesh of Fruit (Fructus Corni) |

| Shichangpu | Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma | Acorus | tatarinowii | Schott | Araceae | Dried Rhizome (Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii) |

| Shihu | Dendrobii Caulis | Dendrobium | nobile | Lindl. | Orchidaceae | Dried Stem (Caulis Dendrobii) |

| Shexiang | Moschus | Moschus | berezovskii | Flerov | Cervidae | Dried Secretion from Scent Gland (Moschus) |

| Suhexiang | Styrax | Liquidambar | orientalis | Mill. | Hamamelidaceae | Resin from Trunk (Styrax Liquidambaris) |

| Taoren | Persicae Semen | Prunus | persica | (L.)Batsch | Rosaceae | Dried Ripe Seed (Semen Persicae) |

| Wuweizi | Schisandrae Chinensis Fructus | Schisandra | chinensis | (Turcz.)Baill. | Magnoliaceae | Dried Ripe Fruit (Fructus Schisandrae) |

| Xixin | Asari Radix et Rhizoma | Asarum | heterotropoides | Fr.Schmidt | Aristolochiaceae | Dried Root and Rhizome (Radix et Rhizoma Asari) |

| Xuanshen | Scrophulariae Radix | Scrophularia | ningpoensis | Hemsl. | Scrophulariaceae | Dried Root (Radix Scrophulariae) |

| Yuanzhi | Polygalae Radix | Polygala | tenuifolia | Willd. | Polygalaceae | Dried Root (Radix Polygalae) |

| Zhiqiao | Aurantii Fructus | Citrus | aurantium | L. (Carl Linnaeus) | Rutaceae | Dried Immature Whole Fruit (Fructus Immaturus Aurantii) |

| Zhishi | Aurantii Fructus Immaturus | Citrus | aurantium | L. (Carl Linnaeus) | Rutaceae | Dried Nearly Mature Halved Fruit (Fructus Aurantii) |

| Zhuru | Bambusae Caulis in Taenias | Bambusa | tuldoides | Munro | Poaceae | Shavings from Middle Stem Layer (Caulis Bambusae in Taeniam) |

| Danggui | Angelicae Sinensis Radix | Angelica | sinensis | (Oliv.) Diels | Apiaceae | Dried Root (Radix Angelicae Sinensis) |

| Chishao | Paeoniae Radix Rubra | Paeonia | lactiflora | Pall. | Ranunculaceae | Dried Root (Radix Paeoniae Alba) |

| Niuhuang | Bovis Calculus | Bos | taurus domesticus | Gmelin | Bovidae | Dried Gallstone (Calculus Bovis) |

| Chansu | Bufonis Venenum | Bufo | bufo gargarizans | Cantor | Bufonidae | Lyophilized Parotoid Gland Secretion (Venenum Bufonis) |

Standardized botanical information table.

The ConPhyMP tool for plant monitoring of medicinal plants was used to conduct a comprehensive assessment of all included studies and to formulate standardized intervention measures. This assessment covered key elements, including botanical names (scientific name, family, and genus), plant parts used, functional components, pharmacological effects, mechanism of action, etc. Based on this assessment, Table 4: Characteristic metabolites of herbs used were established, clearly presenting the correspondence between each standardized plant entity and its functional components.

TABLE 4

| Latin name (ChP 2020) | Functional ingredient | Chemical class | Pharmacopoeial content requirement (ChP 2020) | Pharmacological Effect(s) | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morindae Officinalis Radix | Physicion, Rubiadin | Anthraquinones | Not specified | Anti-osteoporotic | Promotes osteoblast differentiation; Inhibits RANKL/OPG pathway | Ru et al. (2014), Chen et al. (2023) |

| Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata | Aconitine, Mesaconitine | Diterpenoid Alkaloids | Diester-diterpenoid alkaloids ≤0.015% | Cardiotonic, Analgesic | Activates Na+ channels; Enhances myocardial contractility | Ru et al., 2014; Gupta (2020) |

| Bombyx Batryticatus | Fibroin, Sericin | Structural Proteins | Total ash ≤7.0% | Antioxidant, Hypoglycemic | Scavenges ROS; Activates PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Sinapis Semen | Sinalbin | Glucosinolates | Not specified | Antibacterial, Anti-inflammatory | Hydrolyzes to generate phenethyl isothiocyanate; Inhibits NF-κB pathway | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Pinelliae Rhizoma | β-Sitosterol, Cavidine | Sterols, Alkaloids | Not specified | Antitumor (Lung cancer) | Induces G2/M phase arrest in cancer cells; Inhibits EGFR phosphorylation | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Borneolum Syntheticum | d-Borneol | Monoterpenoids | Borneol (C10H18O) ≥55.0% | Penetration enhancer, Anti-inflammatory | Enhances blood-brain barrier permeability; Inhibits COX-2 expression | Gupta (2020) |

| Menthae Haplocalycis Herba | Menthol, Menthone | Monoterpenoids | Volatile oil ≥0.8% | Antispasmodic, Antibacterial | Blocks calcium channels; Inhibits acetylcholine release | Ru et al. (2014) |

| Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma | Atractylenolide III | Sesquiterpene Lactones | Not specified | Anti-inflammatory, Immunomodulatory | Inhibits TNF-α/IL-6 secretion; Modulates Th1/Th2 balance | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Chuanxiong Rhizoma | Z-Ligustilide, Senkyunolide | Phthalides | Ferulic acid ≥0.10% | Antithrombotic, Neuroprotective | Inhibits TXA2 synthesis; Reduces cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus | Peimine, Peimisine | Steroidal Alkaloids | Total alkaloids ≥0.080% | Antitussive, Expectorant | Inhibits airway sensory C-fibers; Reduces substance P release | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Arisaema cum Bile | Taurine, Cholic Acid | Bile Acids | Not specified | Antipyretic, Anticonvulsant | Modulates GABA_A receptors; Inhibits glutamate excitotoxicity | Gupta (2020) |

| Pheretima | Lumbrokinase | Protease | Not specified | Thrombolytic, Anticoagulant | Degrades fibrinogen; Inhibits platelet aggregation | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Rehmanniae Radix | Catalpol, Acteoside | Iridoid Glycosides | Catalpol ≥0.20% | Hypoglycemic, Anti-inflammatory | Activates GLUT4 translocation; Inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Saposhnikoviae Radix | Prim-O-Glucosylcimifugin | Chromones | Not specified | Antiallergic, Analgesic | Blocks histamine H1 receptors; Inhibits TRPV1 channel activation | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Poria | Pachymic Acid, Poriacosides | Triterpenoids | Not specified | Diuretic, Immunomodulatory | Inhibits renal tubular Na+-K+-ATPase; Enhances macrophage phagocytosis | Ru et al. (2014), Luo et al. (2024) |

| Kansui Radix | Kansuinin A | Diterpenoids | Not specified | Purgative, Antitumor | Activates enteric plexus NK1 receptors; Induces watery diarrhea | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma | Glycyrrhizin, Liquiritigenin | Triterpenoids, Flavonoids | Glycyrrhizic acid ≥2.0% | Antiulcer, Hepatoprotective | Inhibits 11β-HSD2; Reduces cortisol catabolism | Ru et al. (2014), Cao et al. (2022) |

| Carthami Flos | Hydroxysafflor yellow A | Chalcones | Not specified | Anti-myocardial ischemia, Anticoagulant | Inhibits PAF receptors; Reduces calcium influx | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Astragali Radix | Astragaloside IV, Calycosin | Saponins, Isoflavones | Astragaloside IV ≥ 0.040% | Immunostimulant, Antioxidant | Activates Nrf2 pathway; Enhances SOD activity | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Platycodonis Radix | Platycodin D | Triterpenoid Saponins | Not specified | Expectorant, Anti-inflammatory | Stimulates respiratory mucus secretion; Inhibits COX-2/PGE2 pathway | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Citri Exocarpium Rubrum | Hesperidin, Nobiletin | Flavonoids | Hesperidin ≥3.0% | Antioxidant, Digestive stimulant | Scavenges free radicals; Enhances gastrointestinal myenteric plexus activity | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Liquidambaris Fructus | Gallic Acid, Ellagic Acid | Phenolic Acids | Not specified | Antibacterial, Anti-inflammatory | Inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase; Blocks TLR4/MyD88 signaling | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Ephedrae Herba | Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine | Alkaloids | Ephedrine ≥0.80% | Antiasthmatic, Diaphoretic | Agonizes β2-adrenergic receptors; Activates sweat gland Na+ channels | He et al. (2023) |

| Ophiopogonis Radix | Ophiopogonin D | Steroidal Saponins | Not specified | Anti-myocardial ischemia, Immunomodulatory | Enhances SOD activity; Inhibits TNF-α/IL-1β production | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix | β-Ecdysone, Inokosterone | Phytosterols | Not specified | Anti-arthritic, Osteogenic | Inhibits MMP-13 expression; Promotes osteoblast RUNX2 activation | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Gentianae Macrophyllae Radix | Gentiopicroside | Iridoids | Not specified | Anti-inflammatory, Hepatoprotective | Inhibits TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway; Attenuates hepatic fibrosis | Ru et al. (2014) |

| Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma | Ginsenoside Rg1, Rb1 | Triterpenoid Saponins | Total saponins ≥0.30% | Anti-fatigue, Neuroprotective | Enhances mitochondrial complex I activity; Inhibits Aβ42 aggregation | Ru et al. (2014), Cao et al. (2022) |

| Cistanches Herba | Echinacoside | Phenylethanoid Glycosides | Echinacoside ≥0.30% | Aphrodisiac, Neuroprotective | Promotes NO/cGMP pathway; Inhibits tau protein hyperphosphorylation | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Cinnamomi Cortex | Cinnamaldehyde, Coumarin | Phenylpropanoids | Cinnamaldehyde ≥75.0% | Hypoglycemic, Antibacterial | Activates AMPK/GLUT4 pathway; Disrupts microbial cell membranes | Ru et al. (2014), He et al. (2023) |

| Notoginseng Radix et Rhizoma | Notoginsenoside R1 | Triterpenoid Saponins | Ginsenoside Rg1 ≥ 0.20% | Hemostatic, Antithrombotic | Activates P2Y12 receptors; Promotes platelet aggregation | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Taxilli Herba | Quercetin, Avicularin | Flavonoids | Not specified | Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | Inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation; Scavenges hydroxyl radicals | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Corni Fructus | Loganin, Cornuside | Iridoid Glycosides | Morroniside ≥0.20% | Hypoglycemic, Nephroprotective | Inhibits α-glucosidase; Reduces glomerular mesangial cell proliferation | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma | β-Asarone | Phenylpropanoids | Not specified | Antiepileptic, Neuroprotective | Enhances GABAergic neurotransmission; Inhibits NMDA receptor overactivation | Ru et al. (2014) |

| Dendrobii Caulis | Dendrobine, Nobilonine | Alkaloids | Not specified | Immunomodulatory, Antitumor | Activates NK cell cytotoxicity; Induces cancer cell apoptosis | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Moschus | Muscone | Macrocyclic Ketones | Muscone ≥2.0% | Cardiotonic, Anti-inflammatory | Activates cardiomyocyte L-type calcium channels; Inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome | He et al. (2023) |

| Styrax | Styrax | Resin | Total vanillic acid ≥27.0% | Antibacterial, Expectorant | Disrupts bacterial biofilms; Stimulates respiratory ciliary motility | He et al. (2023) |

| Persicae Semen | Amygdalin | Cyanogenic Glycosides | Not specified | Antitumor, Anti-fibrotic | Inhibits TGF-β1/Smad pathway; Blocks EMT process | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Schisandrae Chinensis Fructus | Schisandrin B | Lignans | Schisandrin A ≥0.40% | Hepatoprotective, Antioxidant | Enhances GSH synthesis; Inhibits CYP450 enzyme activity | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Asari Radix et Rhizoma | Asarinin, Sesamin | Lignans | Volatile oil ≥2.0% | Analgesic, Anti-inflammatory | Inhibits COX-2/PGE2 pathway; Blocks TRPA1 nociceptive receptors | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Scrophulariae Radix | Harpagoside | Iridoid Glycosides | Harpagoside ≥0.050% | Anti-inflammatory, Immunosuppressive | Inhibits NF-κB activation; Reduces Th17 cell differentiation | Cao et al. (2022) |

| Polygalae Radix | Tenuifolin | Saponins | Not specified | Antidepressant, Neuroprotective | Upregulates BDNF/TrkB pathway; Inhibits MAO-A activity | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Aurantii Fructus | Synephrine, Naringin | Alkaloids, Flavonoids | Synephrine ≥0.30% | Digestive stimulant, Pressor | Agonizes α1-adrenergic receptors; Enhances gastrointestinal motility | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Bambusae Caulis in Taenias | Bambooside A | Flavonoid Glycosides | Not specified | Antioxidant, Antitussive | Scavenges superoxide anions; Inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Angelicae Sinensis Radix | Z-Ligustilide, Ferulic Acid | Phthalides, Phenolic Acids | Ferulic acid ≥0.050% | Hematopoietic, Anticoagulant | Promotes EPO secretion; Inhibits platelet TXA2 synthesis | Choi et al. (2022) |

| Paeoniae Radix Rubra | Paeoniflorin | Monoterpene Glycosides | Paeoniflorin ≥1.8% | Antispasmodic, Anti-inflammatory | Inhibits PGE2 synthesis; Blocks calcium influx | Ru et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2022) |

| Bovis Calculus | Cholic Acid, Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid | Bile Acids | Cholic acid ≥13.0% | Antipyretic, Anticonvulsant | Activates FXR receptors; Inhibits TLR4/NF-κB pathway | He et al. (2023) |

| Bufonis Venenum | Bufalin, Cinobufagin | Steroidal Lactones | Cinobufagin ≥6.0% | Antitumor, Cardiotonic | Inhibits Na+/K+-ATPase; Activates JNK apoptotic pathway | Chen et al. (2023) |

Characteristic metabolite of herbs used.

Collectively, these two tables form the core output of the scientific definition, component standardization, and taxonomic validation of SETCM therapy interventions in this study, providing a reliable, consistent foundation for subsequent analyses (such as efficacy evaluation and mechanistic exploration).

3.3 Quality assessment (risk of bias) of included studies

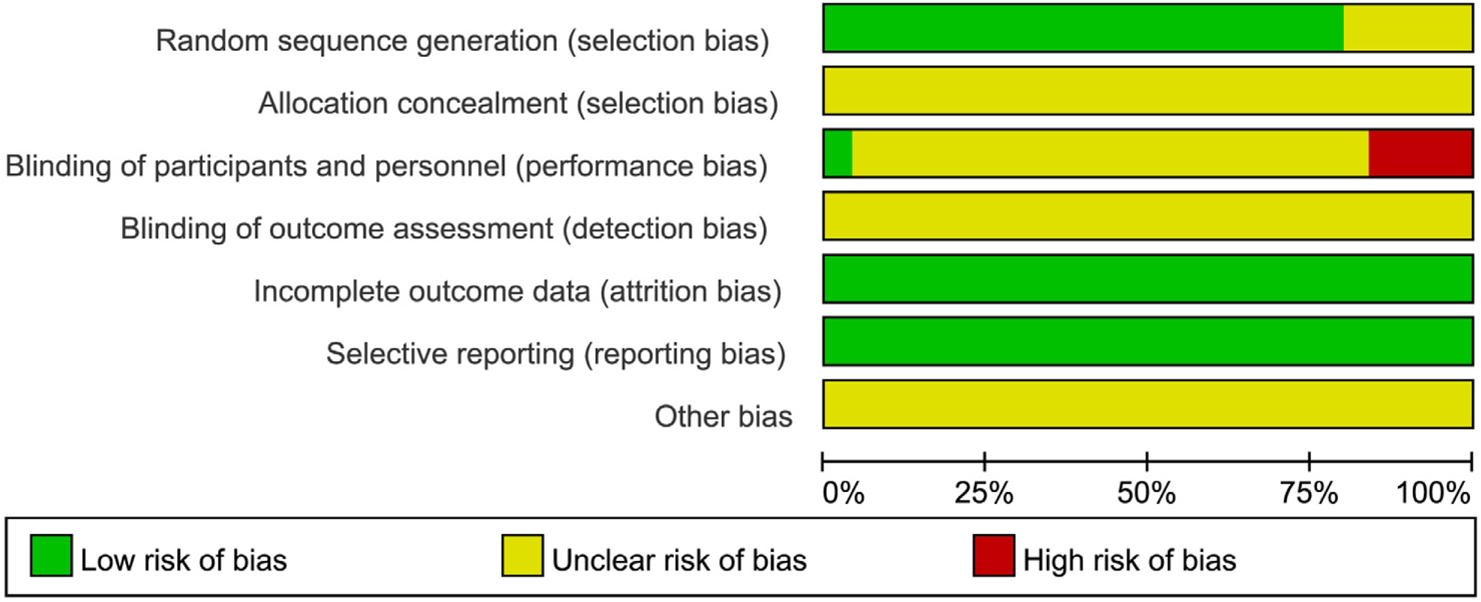

All 25 included studies (Heinrich et al., 2018; Guyatt et al., 2011; Tang and Liu, 2024; Yu and Wu, 2024; Wang and Sun, 2023; Zhu et al., 2023; Yu and Qiu, 2023; Wang FQ. et al., 2023; Xu, 2022; Shi et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Jiao, 2022; Wu et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2021; Shao and Chen, 2020; Zheng et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2021; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Que and Bian, 2016; Lai, 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2008) were published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving patients with PSD. The risk of bias across seven domains was rigorously assessed using the Cochrane RoB 1.0 tool, with complete study-level judgments detailed in Table 5. The risk of bias assessment was as follows: Randomization: Five studies (Ma et al., 2021; Lai, 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2008) did not mention a specific randomization scheme (Unclear risk), while the remainder described randomization methods (Low risk). Allocation concealment: No studies provided sufficient information (Unclear risk). Blinding: Four studies (Wu et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2018; Lai, 2015; Zhao et al., 2012) did not implement blinding (High risk); One study (Tang and Liu, 2024) implemented blinding (Low risk); the remainder were Unclear risk. Attrition bias: All studies reported no dropouts (Low risk). Reporting bias: No selective reporting was detected (Low risk). Other bias: Insufficient data (Unclear risk). See Figures 2, 3. Although the 25 included RCTs collectively showed positive efficacy signals, significant methodological limitations existed: Allocation concealment was inadequately described in all studies (100% “Unclear risk”); Blinding of participants and personnel was High risk in 16% of studies (4/25); Blinding of outcome assessment was Unclear risk in 92% of studies (23/25). These deficiencies, particularly the lack of allocation concealment and blinding, may introduce selection bias and performance/detection bias, potentially inflating the observed treatment effects.

TABLE 5

| Author(s) | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tang and Liu (2024)

Heinrich et al. (2018) |

Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Yu and Wu (2024) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Wang and Sun (2023) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Zhu et al. (2023) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Yu and Qiu (2023) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Wang et al. (2023b) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Xu (2022) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Shi et al. (2022) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Zhou et al. (2022) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Jiao (2022) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Wu et al. (2021) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Dong et al. (2021) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Shao and Chen (2020) | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Zheng et al. (2019) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

|

Zhou et al. (2018)

Shao and Chen (2020) |

Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Luo et al. (2018) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Ma et al. (2021) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Xu and Zhao (2016) | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Que and Bian (2016) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

|

Lai (2015)

Xu and Zhao (2016) |

Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Lin et al. (2014) | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Zhao et al. (2012) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Zhao et al. (2008) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Huang (2007) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Yuan et al. (2024) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

Bias risk assessment table.

FIGURE 2

Results of the risk of bias assessment of the included literature.

FIGURE 3

Summary of the risk of bias of the included literature.

3.4 Safety monitoring and adverse event reporting

This study systematically extracted and re-evaluated all reported adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) from the included primary studies (n = 25 RCTs). Safety data were categorized and graded according to the US National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE v5.0). The specific process was as follows.

3.4.1 AE/SAE extraction and verification

Two researchers independently extracted explicitly reported AEs/SAEs from each study, including event type, number of occurrences, severity, causality relationship to the study intervention, and management measures. For vaguely described events (e.g., “local discomfort”), the original authors were contacted for clarification, and if details were unobtainable, the event was marked as “Unspecified.”

3.4.2 CTCAE v5.0 standardized classification

All AEs were classified by organ system and graded for severity into five levels:

Grade 1 (Mild): Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; intervention not indicated. Grade 2 (Moderate): Minimal, local, or noninvasive intervention indicated. Grade 3 (Severe): Hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care activities of daily living (ADL). Grade 4 (Life-threatening): Urgent intervention indicated. Grade 5 (Death): Death related to AE.

3.4.3 Safety analysis results

Only three studies (12% of included studies) reported AEs. All reported events were local skin reactions, with a cumulative occurrence of 24 cases (Total sample size N = 2,159), yielding an overall incidence rate of 2.1%. The detailed classification is as follows (Table 6).

TABLE 6

| Organ system | Type of AE | CTCAE terminology | Severity | Number of occurrences | Source of study | Did it lead to the interruption of the intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and subcutaneous tissues | Localized erythema | Rash maculo-papular | Grade 1 | 12 | Yu Mengyan, 2023 | No |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissues | Pruritus | Pruritus | Grade 1 | 8 | Shao Tingting, 2020 | No |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissues | Contact dermatitis | Dermatitis contact | Grade 2 | 4 | Zhu Huazhen, 2023 | Yes (2 cases with patch suspension) |

Adverse events associated with external herbal treatment method (classified according to CTCAE v5.0).

Key Findings: The only reported AE type: Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (100%). Severity distribution:

Grade 1 (83.3%, n = 20): Transient erythema/pruritus; resolved spontaneously without intervention.

Grade 2 (16.7%, n = 4): Contact dermatitis; required temporary intervention suspension and topical corticosteroid application.

No SAEs reported: No Grade 3–5 events or systemic reactions (e.g., allergy, hepatic/renal dysfunction) occurred.

3.4.4 Evidence limitations

Incomplete reporting: 88% of studies (22/25) failed to describe AE monitoring procedures or explicitly state “no adverse reactions observed.”

Unclear causality: No studies provided laboratory-confirmed causal links (e.g., patch testing) between AEs and specific herbal constituents/excipients.

Lack of long-term safety data: All studies omitted follow-up for delayed reactions (>4 weeks post-intervention). Most (88%) studies lacked prospective safety monitoring protocols, precluding definitive conclusions about long-term tolerability.

3.5 Meta-analysis results

3.5.1 Meta-analysis of overall response rate

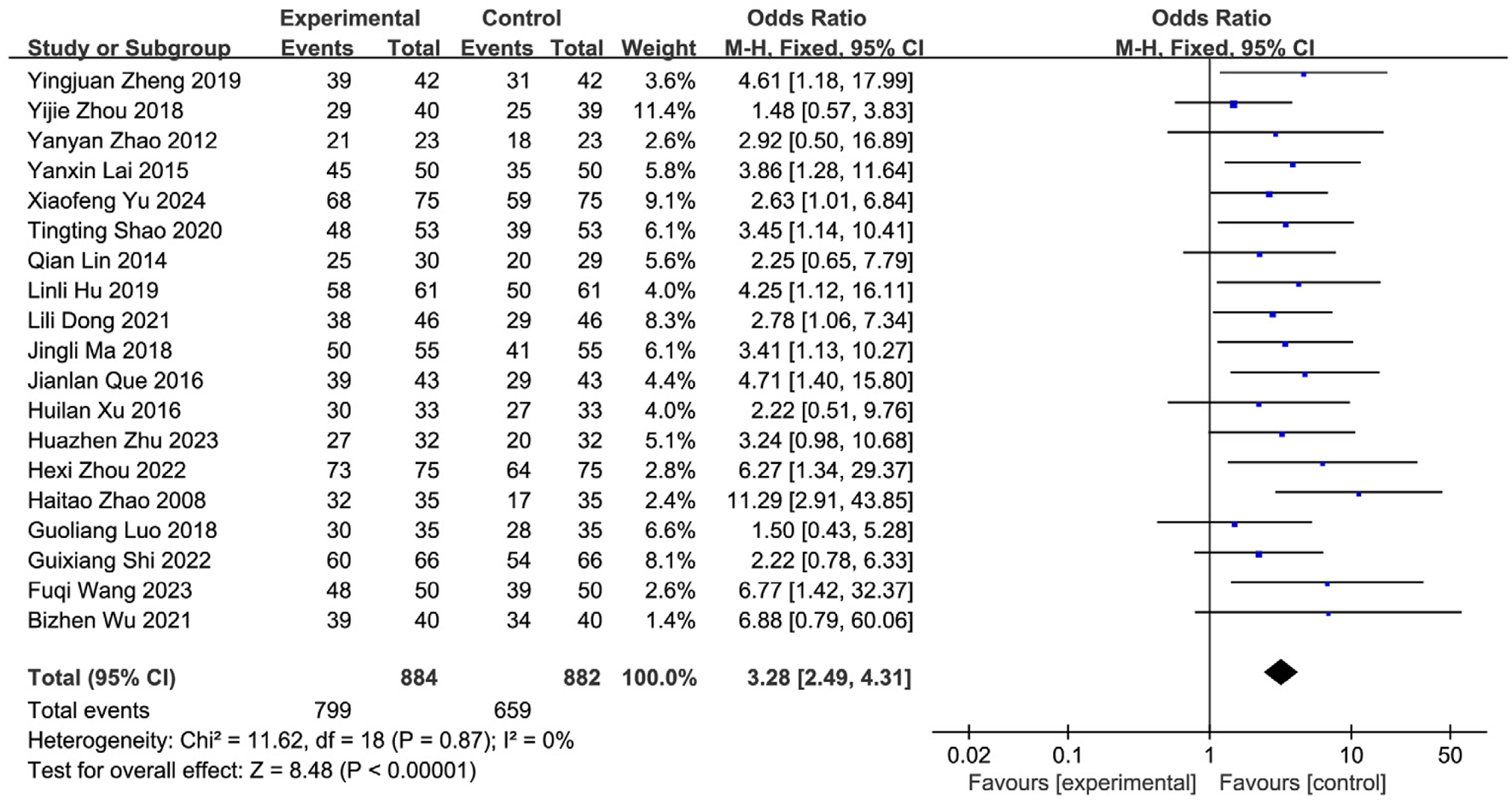

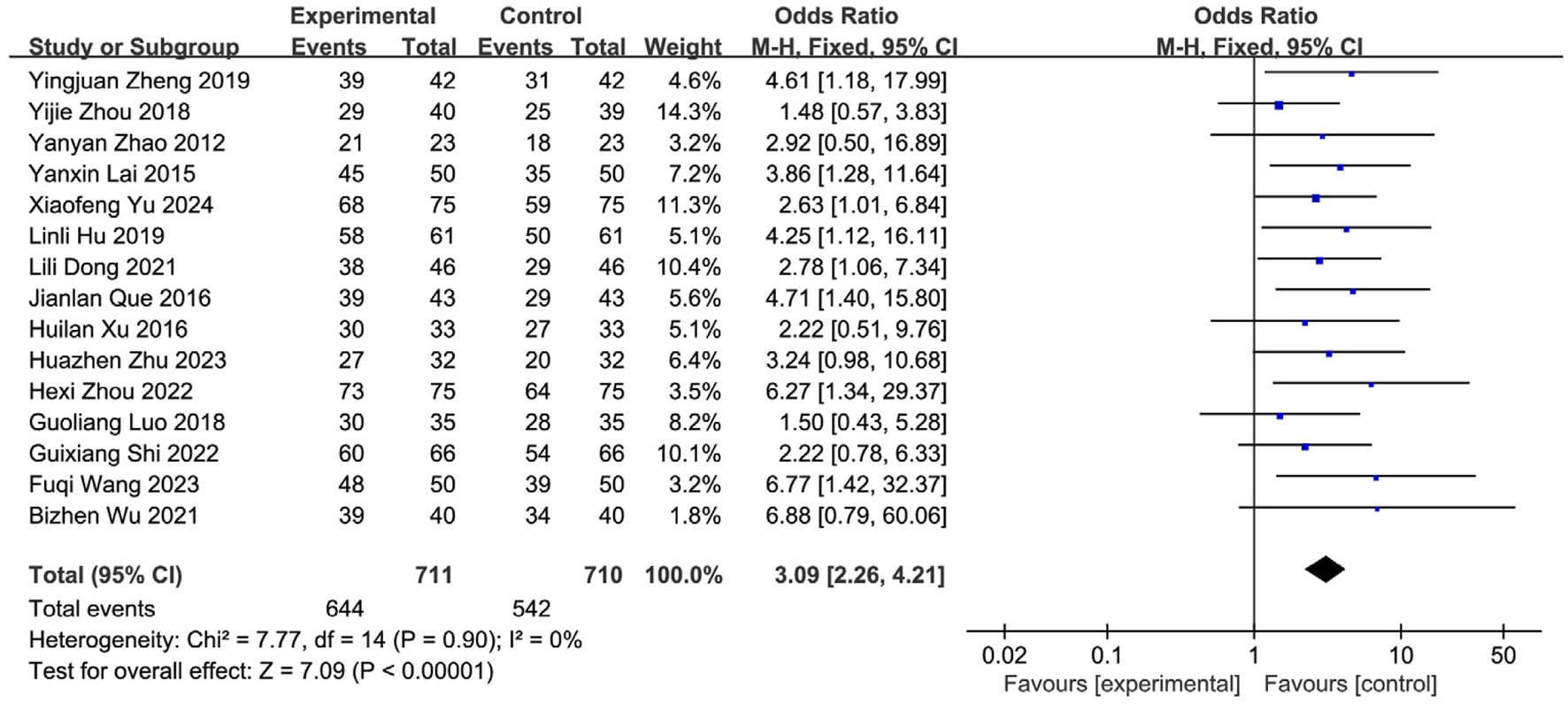

Nineteen studies (Yu and Wu, 2024; Zhu et al., 2023; Wang FQ. et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2021; Shao and Chen, 2020; Zheng et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2021; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Que and Bian, 2016; Lai, 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2008; Huang, 2007) reported the post-treatment clinical overall response rate, involving 1,766 patients (SETCM therapies group: n = 884, effective cases = 799; Control group: n = 882, effective cases = 659). Heterogeneity testing (I2 = 0%, P = 0.87) indicated homogeneity among the selected studies, warranting the use of a fixed-effects model (FEM) for meta-analysis. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the overall response rate between the SETCM therapies group and the control group [OR = 3.28, 95% CI: (2.49, 4.31), P < 0.00001]. This indicates that the application of SETCM therapies significantly improved the clinical overall response rate compared to the control group (Figure 4). Sensitivity analysis, excluding three studies (Shao and Chen, 2020; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Huang, 2007) rated as high risk for performance bias (blinding of participants), showed that the direction and statistical significance of the pooled effect estimate remained materially unchanged [OR = 3.09, 95% CI: (2.26, 4.21), P < 0.00001], demonstrating the robustness of the meta-analysis results (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4

Meta-analysis of the total clinical effectiveness rate of the 19 studies of SETCM therapies for PSD included.

FIGURE 5

Sensitivity analysis of the total clinical effectiveness rate of the 15 studies of SETCM therapies for PSD included.

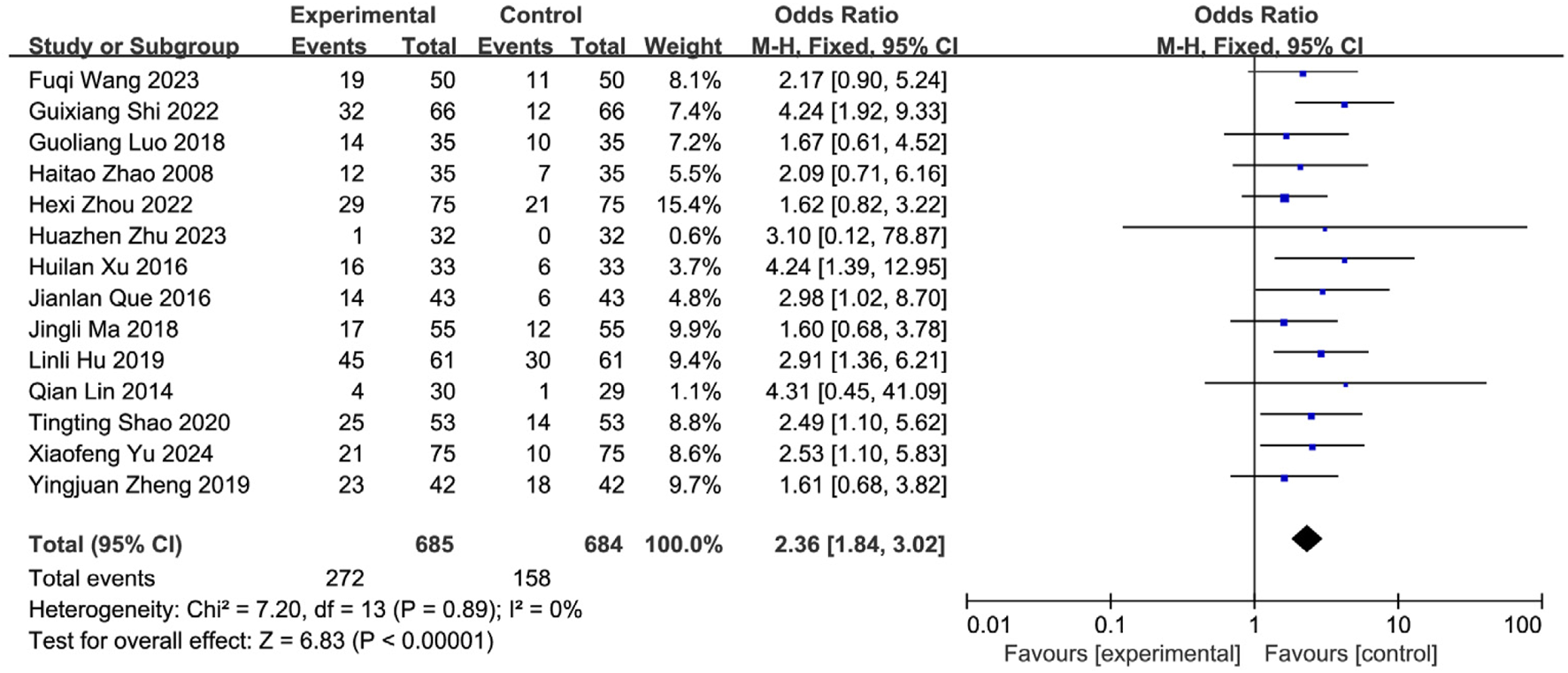

3.5.2 Meta-analysis of cure rate

Fourteen studies (Yu and Wu, 2024; Zhu et al., 2023; Wang FQ. et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Shao and Chen, 2020; Zheng et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2021; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Que and Bian, 2016; Lai, 2015; Zhao et al., 2012; Huang, 2007) reporting the post-treatment clinical cure rate were included, involving 1,369 patients (SETCM therapies group: n = 685, cured cases = 272; Control group: n = 684, cured cases = 158). Heterogeneity testing (I2 = 0%, P = 0.89) indicated homogeneity among the selected studies, warranting the use of an FEM for meta-analysis. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the cure rate between the SETCM therapies group and the control group [OR = 2.36, 95% CI: (1.84, 3.02), P < 0.00001]. This indicates that the application of SETCM therapies significantly improved the clinical cure rate compared to the control group (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6

Meta-analysis of the cure rate of the 14 included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

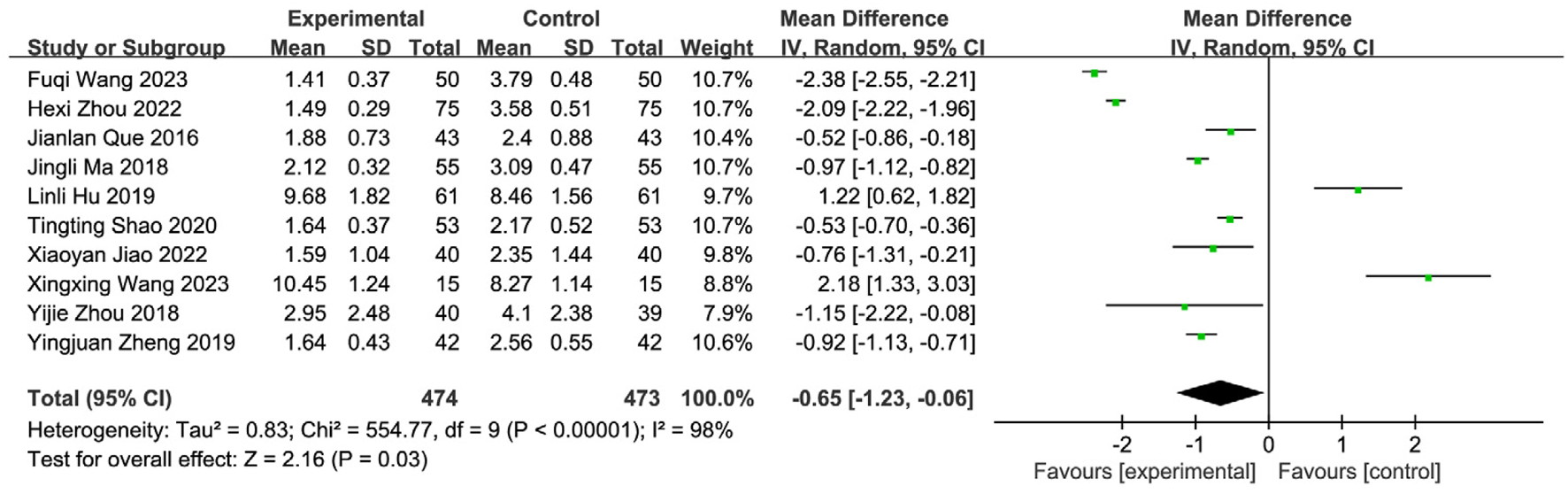

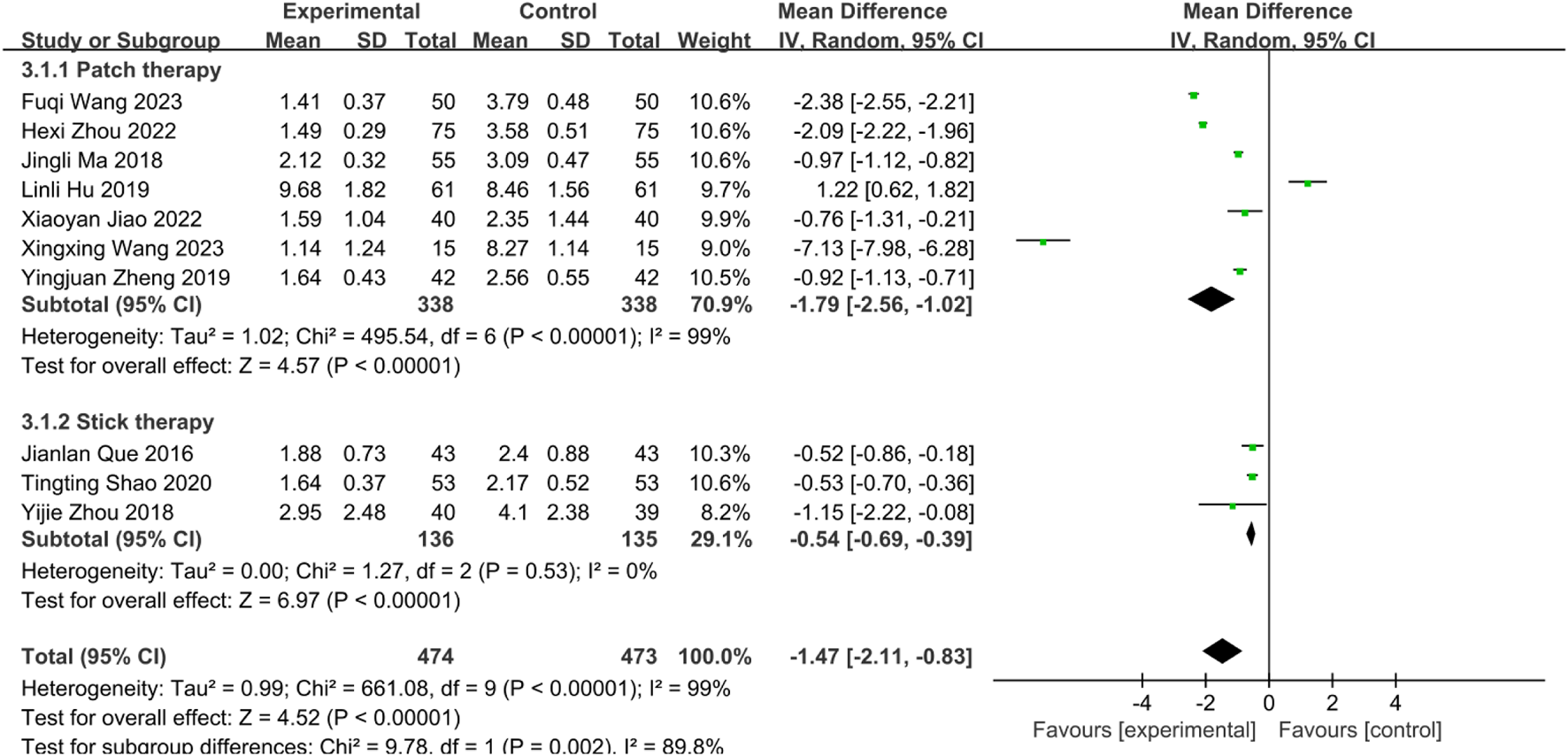

3.5.3 Meta-analysis of water swallowing test (WST) scores

Ten studies (Wang and Sun, 2023; Wang FQ. et al., 2023; Jiao, 2022; Shao and Chen, 2020; Zheng et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Que and Bian, 2016; Lai, 2015) reported post-treatment WST scores, involving 947 patients (SETCM therapies group: n = 474; Control group: n = 473). Overall heterogeneity testing indicated substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, P < 0.00001). Sequential removal of individual studies failed to significantly reduce heterogeneity, suggesting intervention modality as a primary source. A random-effects model (REM) was employed for meta-analysis. Results demonstrated that SETCM therapies significantly reduced WST scores compared to controls [MD = −0.65, 95%CI: (−1.23, −0.06), P = 0.03] (Figure 7). High heterogeneity likely originated from variations in intervention type, duration, assessment timing, and combination therapies.

FIGURE 7

Meta-analysis of WST scores of 10 included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

Subgroup analysis by intervention type revealted significant residual heterogeneity (I2 = 89.8%, P = 0.002), necessitating REM. Results showed: Herbal patching: Significantly reduced WST scores [MD = −1.79, 95%CI: (−2.56, −1.02), P < 0.00001]. Medicated stick stimulation: Significantly reduced WST scores [MD = −0.54, 95%CI: (−0.69, −0.39), P < 0.00001] (Figure 8). While all subgroups demonstrated efficacy, unresolved heterogeneity suggests contributions from technical factors (operator skill, application site, session duration, intervention timing).

FIGURE 8

Subgroup analysis of WST scores of 10 included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

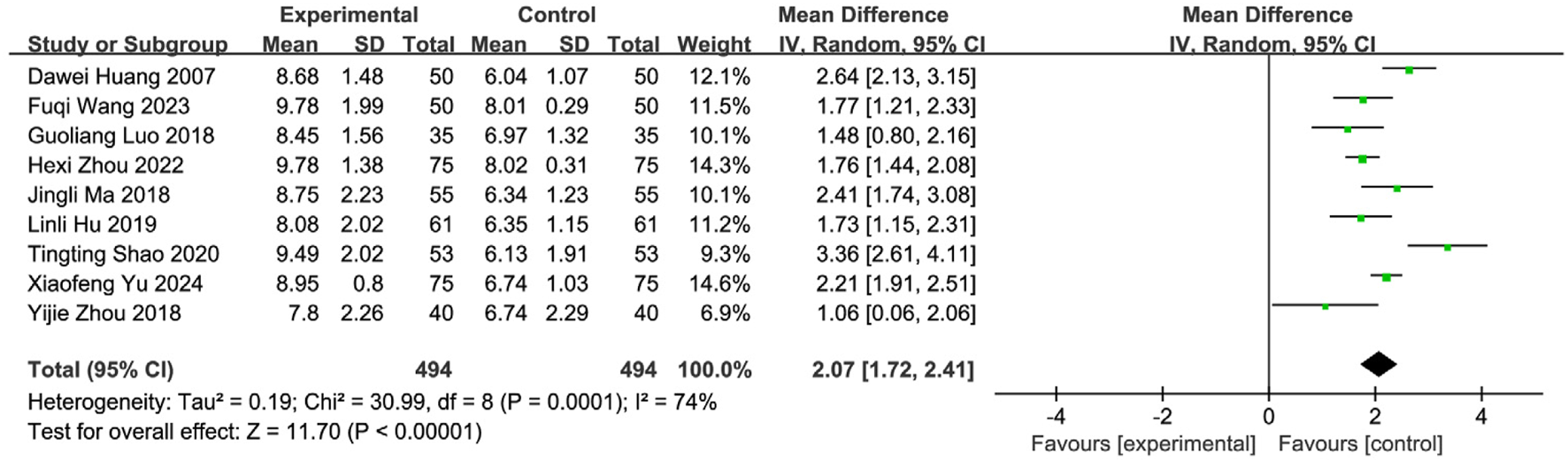

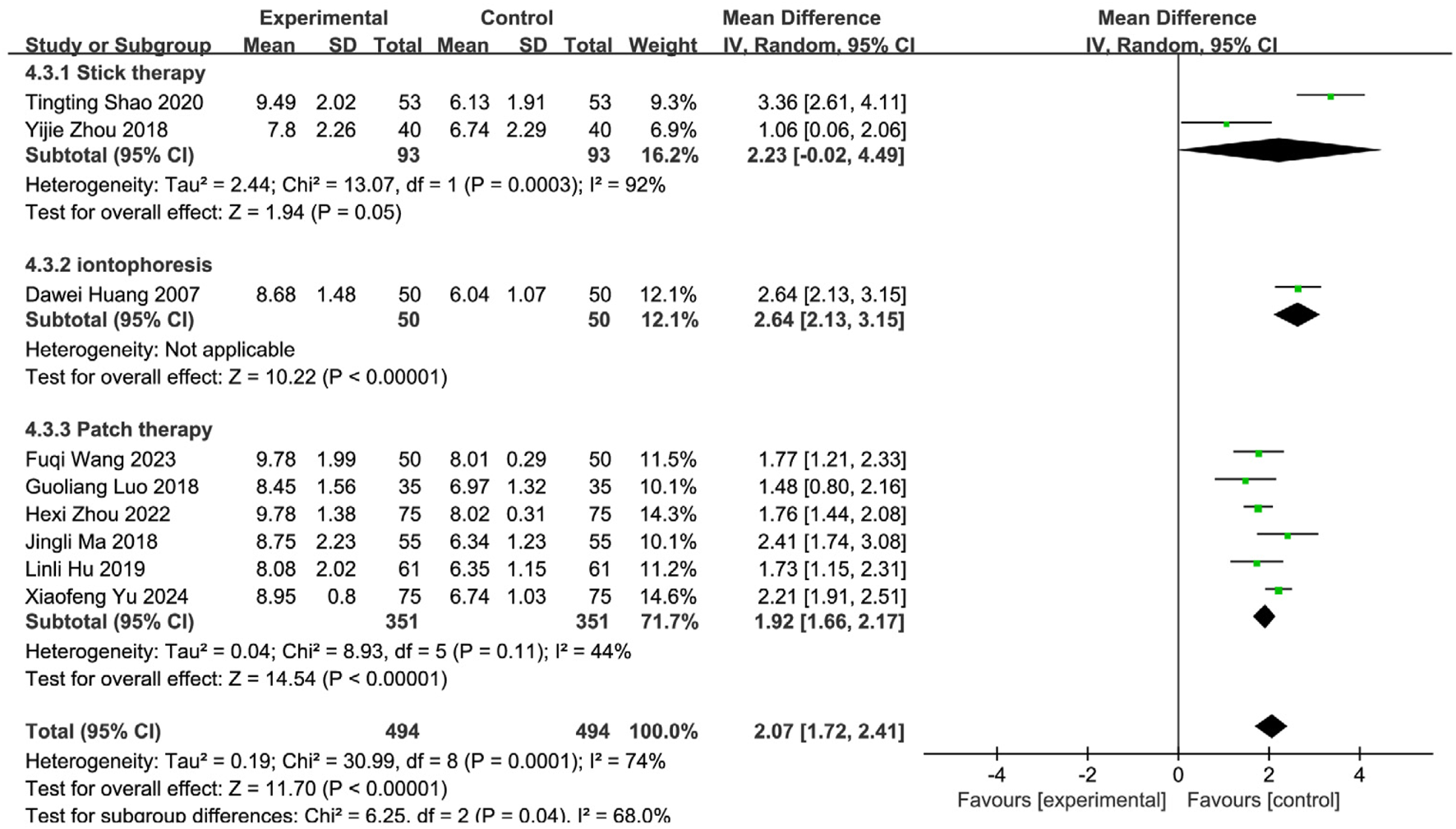

3.5.4 Meta-analysis of videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) scores

Nine studies (Yu and Wu, 2024; Wang FQ. et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2022; Shao and Chen, 2020; Zhou et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2021; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Yuan et al., 2024) involving 988 PSD patients (SETCM therapies: n = 494; Control: n = 494) evaluated swallowing function using VFSS scores. Random-effects meta-analysis indicated SETCM therapies significantly improved VFSS scores versus controls [MD = 2.07, 95%CI (1.72, 2.41), Z = 11.70, P < 0.00001], with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 74%, P = 0.0001; Figure 9). Subgroup analysis by intervention type (Figure 10).

FIGURE 9

Meta-analysis of VFSS scores of nine included studies examining SETCM therapies for PSD.

FIGURE 10

Subgroup analysis of VFSS scores of nine included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

Medicated stick (two studies): Moderate improvement [MD = 2.23, 95%CI (−0.02, 4.49)], high heterogeneity (I2 = 92%, P = 0.0003). Iontophoresis (one study): Significant improvement [MD = 2.64, 95%CI (2.13, 3.15)]. Herbal patching (six studies): Consistent improvement [MD = 1.92, 95%CI (1.66, 2.17)], moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 44%, P = 0.11). Subgroup differences were significant (P = 0.04, I2 = 68.0%), confirming that intervention type partially explained heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis identified three influential studies (Yu and Wu, 2024; Shao and Chen, 2020; Yuan et al., 2024) (potential confounders: patient age, operator technique, treatment duration/timing). Their exclusion reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 19%, P = 0.29). Fixed-effects analysis affirmed robust efficacy [MD = 1.75, 95%CI (1.55, 1.98), Z = 15.95, P < 0.00001; Figure 11]. SETCM therapies significantly enhanced VFSS scores and accelerated swallowing recovery.

FIGURE 11

![Forest plot showing mean differences between experimental and control groups across six studies. Each study lists means, standard deviations, and sample sizes. Confidence intervals are indicated with horizontal lines. The overall effect size is 1.76, favoring the experimental group, with a 95% confidence interval of [1.55, 1.98]. The plot indicates low heterogeneity with an I-squared value of 19%.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g011.webp)

SETCM therapy sensitivity analysis of VFSS scores of six included studies of the treatment of PSD.

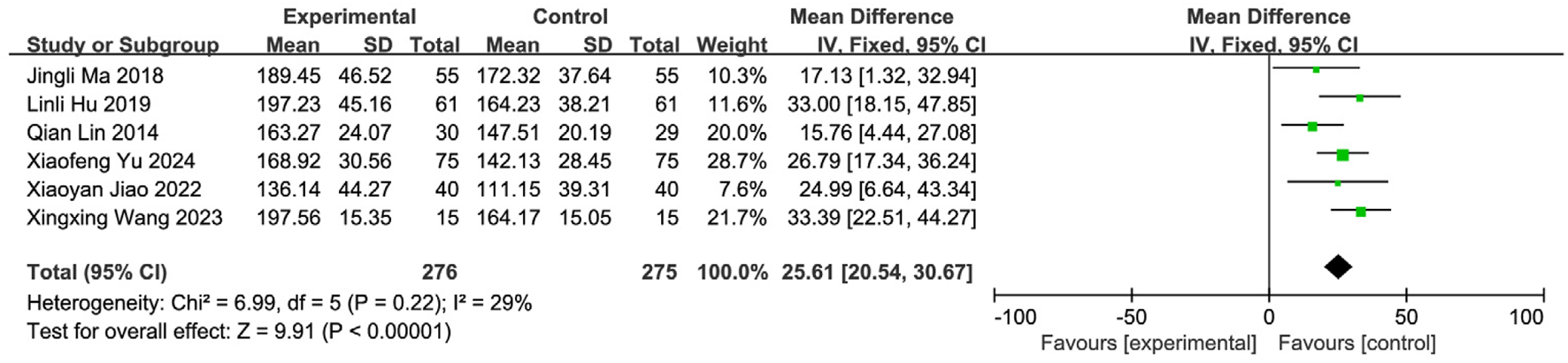

3.5.5 Meta-analysis of SWAL-QOL scores

Six studies (Yu and Wu, 2024; Wang and Sun, 2023; Jiao, 2022; Zhou et al., 2018; Xu and Zhao, 2016; Zhao et al., 2012) reported SWAL-QOL scores, involving 551 patients (SETCM therapies: n = 275; Control: n = 276). Heterogeneity testing (I2 = 29%, P = 0.22) indicated homogeneity, supporting an FEM. Meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the SETCM therapies group [MD = 25.61, 95%CI (20.54, 30.67), Z = 9.91, P < 0.00001], indicating SETCM therapies significantly reduced SWAL-QOL scores (i.e., improved quality of life) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12

Meta-analysis of SWAL-QOL scores of six included studies of the treatment of PSD using SETCM therapies.

3.5.6 Meta-analysis of post-intervention aspiration

Three studies (Tang and Liu, 2024; Yu and Qiu, 2023; Jiao, 2022) reported aspiration events, involving 228 patients (SETCM therapies: n = 114, aspiration = 6; Control: n = 114, aspiration = 20). Homogeneity was confirmed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.87), warranting an FEM. SETCM therapies significantly reduced aspiration risk [OR = 0.21, 95%CI (0.08, 0.59), Z = 2.96, P = 0.003] (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13

![Forest plot displaying the odds ratios from three studies comparing experimental and control groups. The studies are Mengyan Yu 2023, Xiaoyan Jiao 2022, and Xuemei Tang 2024. Each study shows events and weights. The studies cumulatively favor the experimental group with an overall odds ratio of 0.21, 95% CI [0.08, 0.59]. Heterogeneity is minimal, and the overall effect is significant.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g013.webp)

Meta-analysis of misabsorption rates of three included studies on the treatment of PSD by SETCM therapies.

3.5.7 Supplementary meta-analyses: Activities of daily living

3.5.7.1 MBI score meta-analysis

Two studies (Wang and Sun, 2023; Zhou et al., 2018) reported MBI scores (n = 152; SETCM therapies:76, Control:76). Homogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.72) supported FEM. SETCM therapies significantly improved MBI scores [MD = 12.71, 95%CI (9.68, 15.73), Z = 8.23, P < 0.00001], indicating enhanced daily living independence (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14

Meta-analysis of MBI scores of two included studies on the treatment of PSD by SETCM therapies.

3.5.7.2 ADL score meta-analysis

Two studies (Tang and Liu, 2024; Shi et al., 2022) reported ADL scores (n = 200; SETCM therapies:100, Control:100). Homogeneity (I2 = 12%, P = 0.29) supported FEM. SETCM therapies significantly improved ADL scores [MD = 16.57, 95%CI (12.16, 20.98), Z = 7.36, P < 0.00001], confirming better self-care capacity (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15

Meta-analysis of two included studies reporting ADL scores for treatment of PSD with SETCM therapies.

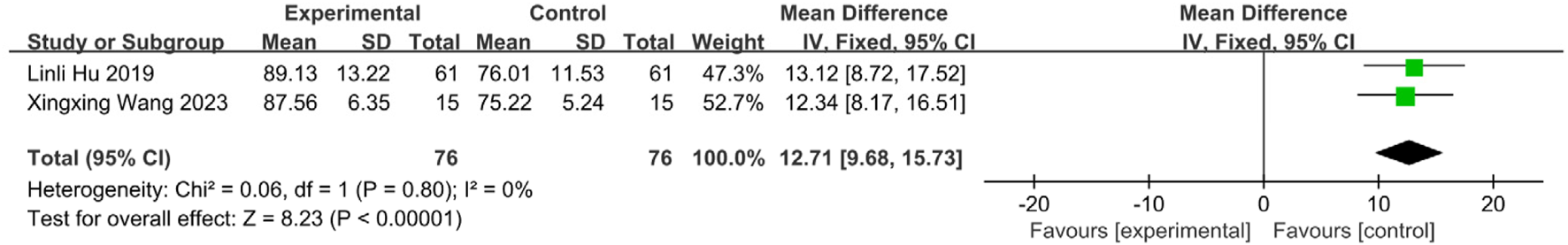

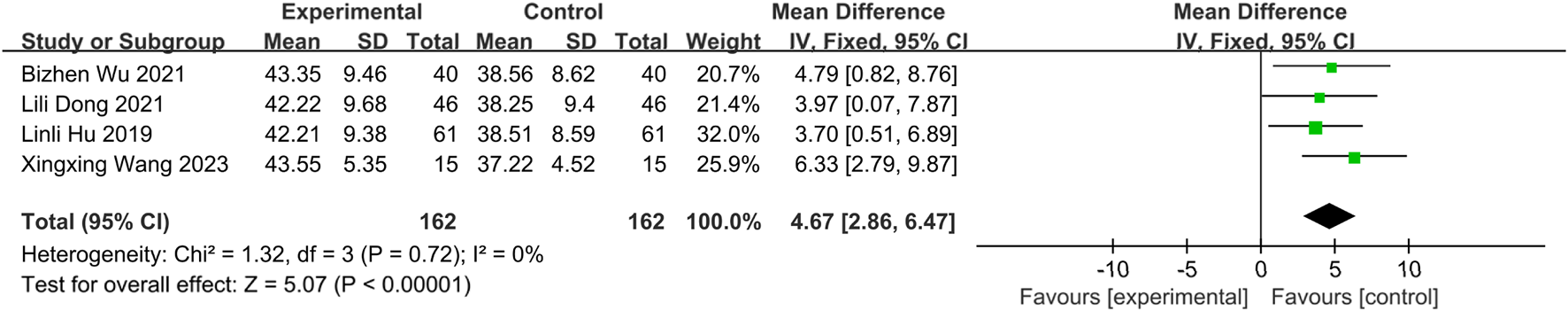

3.5.8 Meta-analysis of serum albumin (ALB) levels

Four studies (Wang and Sun, 2023; Wu et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2018) involving 324 patients (intervention: n = 162; control: n = 162) reported serum albumin (ALB) levels. Homogeneity was confirmed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.72), and an FEM was applied. Results demonstrated significantly higher ALB levels in the intervention group than in the controls [MD = 4.67, 95% CI (2.86, 6.47), Z = 5.07, P < 0.00001], indicating that SETCM therapies increase serum albumin concentrations in patients with PSD (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16

Meta-analysis of four included studies of ALB levels for SETCM therapy treatment of PSD.

3.5.9 Meta-analysis of prealbumin (PA) levels

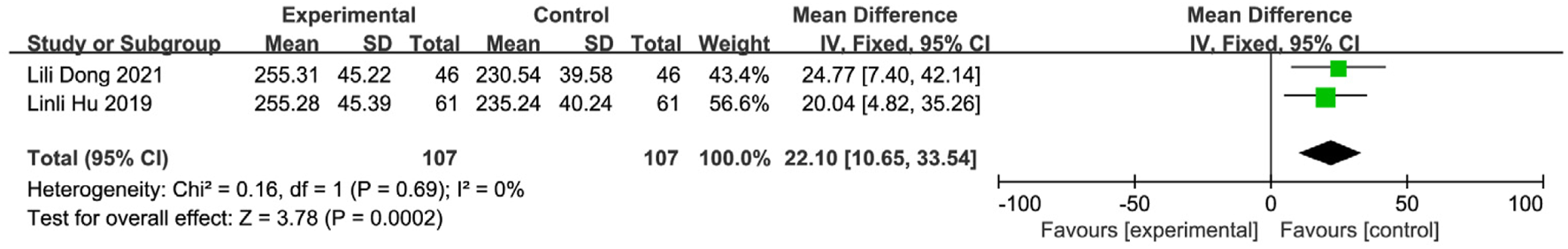

Three studies (Wang and Sun, 2023; Dong et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2018) involving 244 patients (intervention: n = 122; control: n = 122) reported prealbumin (PA) levels. Significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 64%, P = 0.06), necessitating a random-effects model (REM) (Figure 17). Sensitivity analysis identified Wang Xingxing’s study (Wang and Sun, 2023) as the source of heterogeneity; its exclusion resulted in homogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.69). The observed heterogeneity likely originated from the relatively small sample size in Wang and Sun (2023), which may compromise statistical power. An FEM was applied to the remaining two homogeneous studies. Results showed a statistically significant increase in PA levels for the intervention group [MD = 22.10, 95% CI (10.65, 33.54), Z = 3.78, P = 0.0002], demonstrating that SETCM therapies elevate prealbumin levels in PSD patients (Figure 18).

FIGURE 17

![Forest plot showing the mean differences between experimental and control groups in three studies by Lili Dong 2021, Linli Hu 2019, and Xingxing Wang 2023. The mean differences and 95% confidence intervals are presented for each study, with a pooled estimate at the bottom: 30.75 [12.76, 48.74]. The plot indicates heterogeneity with Tau squared equals 159.21, Chi squared equals 5.51, degrees of freedom equals 2, P equals 0.06, and I squared equals 64%. A test for overall effect shows Z equals 3.35, P equals 0.0008, favoring the experimental intervention.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g017.webp)

Meta-analysis of three included studies on PA levels during SETCM therapy treatment of PSD.

FIGURE 18

Sensitivity analysis of two included studies on PA levels during SETCM therapy treatment of PSD.

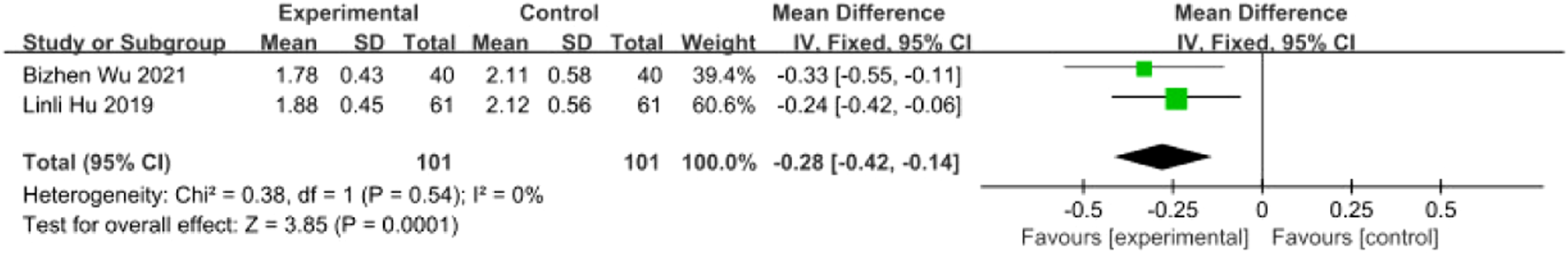

3.5.10 Meta-analysis of NRS2002 scores

Two studies (Wu et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2018) involving 202 patients (intervention: n = 101; control: n = 101) reported Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) scores. Homogeneity was confirmed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54), supporting an FEM. Results revealed a statistically significant reduction in nutritional risk scores for the intervention group [MD = −0.28, 95% CI (−0.42, −0.14), Z = 3.85, P = 0.0001], suggesting that SETCM therapies mitigate malnutrition risk in PSD patients (Figure 19).

FIGURE 19

Meta-analysis of two included studies of SETCM therapy treatment of PSD, Meta-analysis of literature NRS2002 scores.

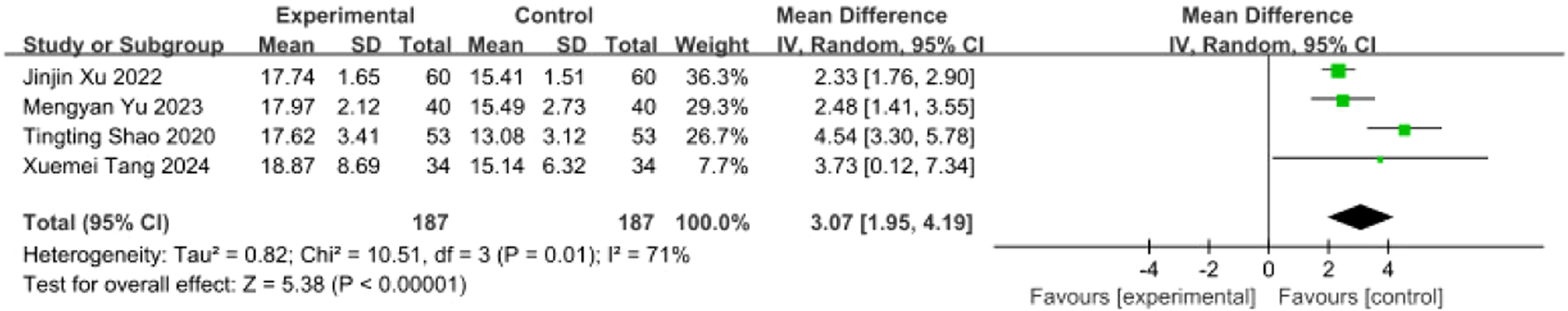

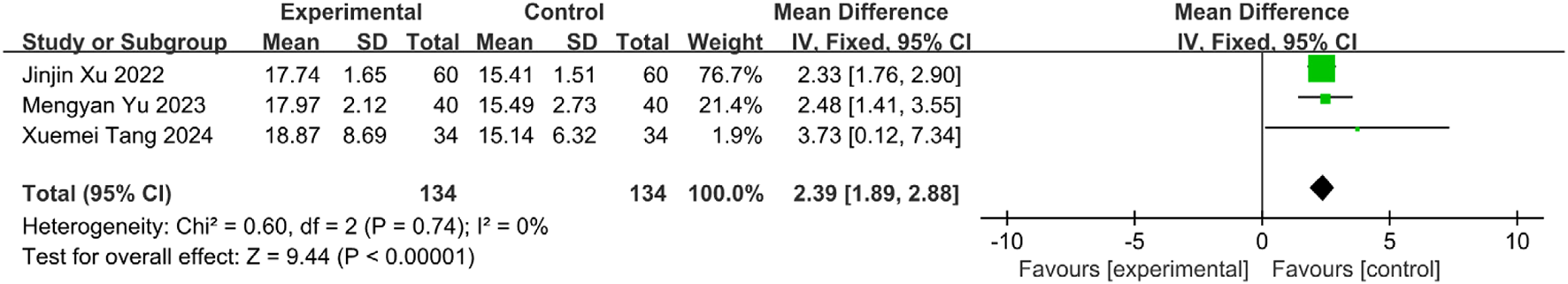

3.5.11 Meta-analysis of GUSS scores

Four studies (Tang and Liu, 2024; Yu and Qiu, 2023; Xu, 2022; Shao and Chen, 2020) involving 374 patients (intervention: n = 187; control: n = 187) reported GUSS scores. Heterogeneity testing indicated substantial variability among studies (I2 = 71%, P = 0.01), warranting a random-effects model (REM) for meta-analysis (Figure 20). Sensitivity analysis via sequential exclusion revealed that removal of Shao Tingting’s study (Shao and Chen, 2020) significantly reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.74). This observed heterogeneity likely stemmed from divergent intervention protocols in Shao and Chen (2020), which increased the dispersion of effect estimates. The remaining three homogeneous studies were analyzed using an FEM. Results demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in GUSS scores for the intervention group [MD = 2.39, 95% CI (1.89, 2.88), Z = 9.44, P < 0.00001], indicating that SETCM therapies significantly enhance swallowing function in PSD patients (Figure 21).

FIGURE 20

Meta-analysis of GUSS scores from four included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

FIGURE 21

Sensitivity analysis of GUSS scores from three included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

3.5.12 Meta-analysis of enteral nutrition tube duration

Three studies (Tang and Liu, 2024; Yu and Qiu, 2023; Xu, 2022) involving 268 patients (intervention: n = 134; control: n = 134) reported enteral nutrition tube duration. Heterogeneity testing confirmed homogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.72), supporting an FEM. Results showed a statistically significant reduction in tube duration for the intervention group [MD = −2.83, 95% CI (−3.25, −2.41), Z = 13.19, P < 0.00001], indicating that SETCM therapies shorten enteral nutrition dependency in PSD patients (Figure 22).

FIGURE 22

![Forest plot showing mean differences between experimental and control groups across three studies: Jinjin Xu 2022, Mengyan Yu 2023, and Xuemei Tang 2024. The plot demonstrates statistical significance favoring the experimental group, with a total mean difference of -2.83 and a 95% confidence interval of [-3.25, -2.41]. Heterogeneity is low with Chi² = 0.65, df = 2, P = 0.72, and I² = 0%. Overall effect significance is Z = 13.19, P < 0.00001.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g022.webp)

Meta-analysis of gastric tube retention duration of three included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD.

3.5.13 Meta-analysis of tube removal success rate

Three studies (Tang and Liu, 2024; Yu and Qiu, 2023; Xu, 2022) involving 268 patients (intervention: n = 134; control: n = 134) reported tube removal success rates. Homogeneity was confirmed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.82), and an FEM was applied. Results demonstrated a statistically significant increase in success rates for the intervention group [OR = 4.56, 95% CI (2.44, 8.53), Z = 4.76, P < 0.00001], indicating that SETCM therapies improve enteral nutrition tube removal outcomes in PSD patients (Figure 23).

FIGURE 23

![Forest plot showing odds ratios for three studies: Jinjin Xu 2022, Mengyan Yu 2023, and Xuemei Tang 2024. The experimental groups had significantly higher events compared to control groups. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each study are displayed: Jinjin Xu 6.33 [1.73, 23.23], Mengyan Yu 3.81 [1.45, 10.02], Xuemei Tang 4.34 [1.49, 12.65]. The total odds ratio is 4.56 [2.44, 8.53]. Heterogeneity is low with Chi² = 0.39, I² = 0%. Overall effect test Z = 4.76, P < 0.00001.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g023.webp)

Gastric tube removal success rates reported in three included studies on SETCM therapies for PSD. Meta-analysis of gastric tube removal success rates in the literature.

3.5.14 Meta-analysis of FDS scores

Two studies (Xu and Zhao, 2016; Zhao et al., 2008) involving 156 patients (intervention: n = 78; control: n = 78) reported functional dysphagia scale (FDS) scores. Heterogeneity testing confirmed homogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.50), supporting an FEM. Results demonstrated statistically significant between-group differences [MD = 2.25, 95% CI (1.79, 2.72), Z = 9.51, P < 0.00001], indicating that SETCM therapies improve swallowing function in PSD patients (Figure 24).

FIGURE 24

![Forest plot showing the effect size of two studies, Jingli Ma 2018 and Yanyan Zhao 2012, comparing experimental and control groups. Mean differences with 95% confidence intervals are given: 2.07 [1.37, 2.77] and 2.39 [1.77, 3.01] respectively. The overall effect is 2.25 [1.79, 2.72]. Heterogeneity indicates Chi² = 0.45, df = 1 (P = 0.50); I² = 0%. The test for overall effect shows Z = 9.51 (P < 0.00001). Results favor the experimental group.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635090/xml-images/fphar-16-1635090-g024.webp)

Meta-analysis of FDS dysphagia efficacy score reported by two included studies of SETCM therapies for PSD hemispheres.

3.5.15 Stratified efficacy analysis by stroke location and intervention modality

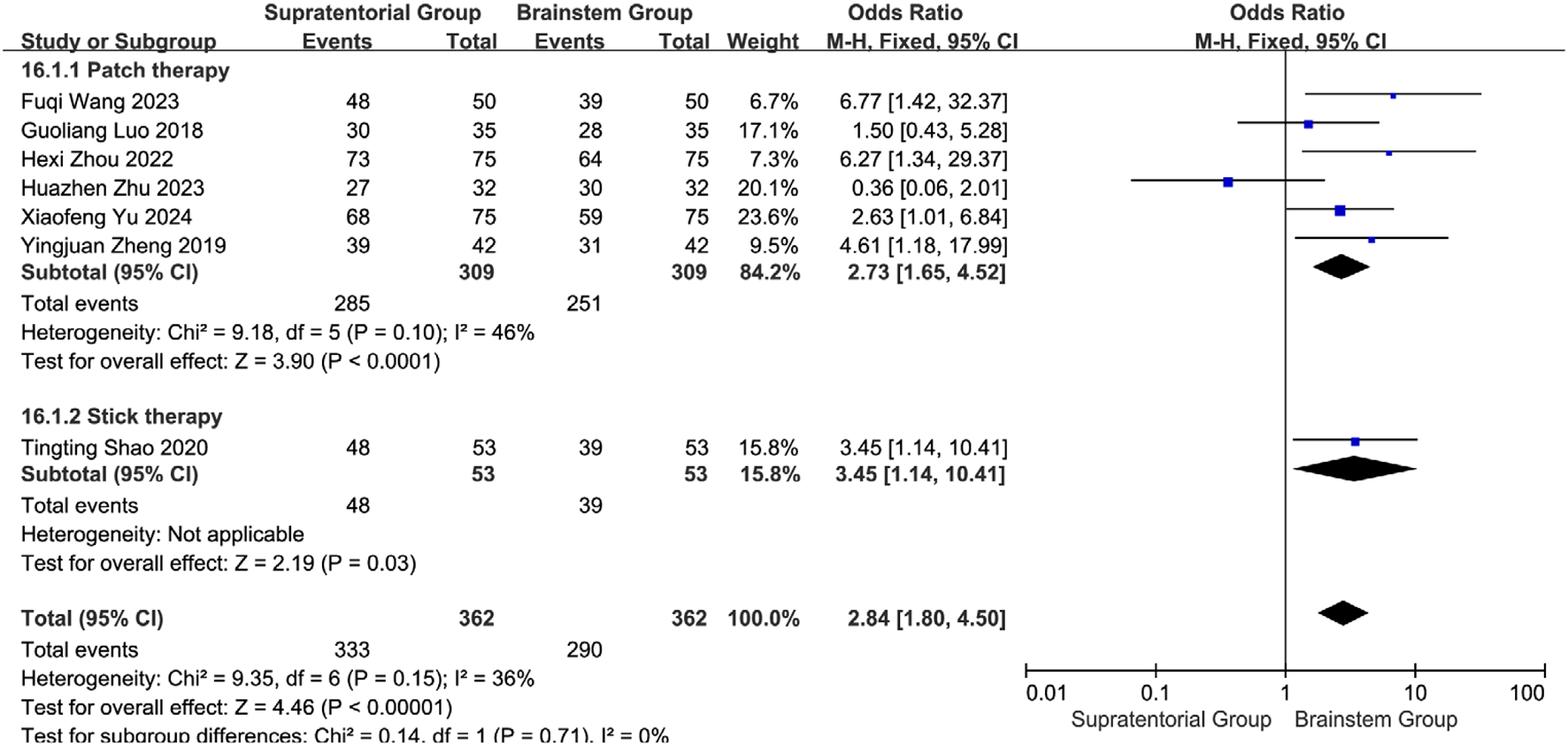

Considering potential effect variations across interventions and lesion locations, efficacy outcomes were stratified by stroke site (supratentorial vs. brainstem) and intervention type. Supratentorial subgroup analysis: Acupoint application showed significant efficacy: Pooled OR = 2.73 (95% CI: 1.65–4.52, P < 0.0001) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 46%, P = 0.10). Wang Fuqi (2023): OR = 6.77 [1.42, 32.37]; Yu Xiaofeng (2024): OR = 2.63 [1.01, 6.84] Medicated stick therapy demonstrated complementary efficacy: Shao Tingting (2020) OR = 3.45 (P = 0.03), with no statistical difference versus acupoint application (subgroup difference: P = 0.71). Overall effect: OR = 2.84 (95% CI: 1.80–4.50, P < 0.00001), supporting acupoint application as primary therapy for supratentorial lesions (Figure 25).

FIGURE 25

Subgroup analysis of the efficacy of different interventions in patients with stroke foci located in the cerebral hemispheres.

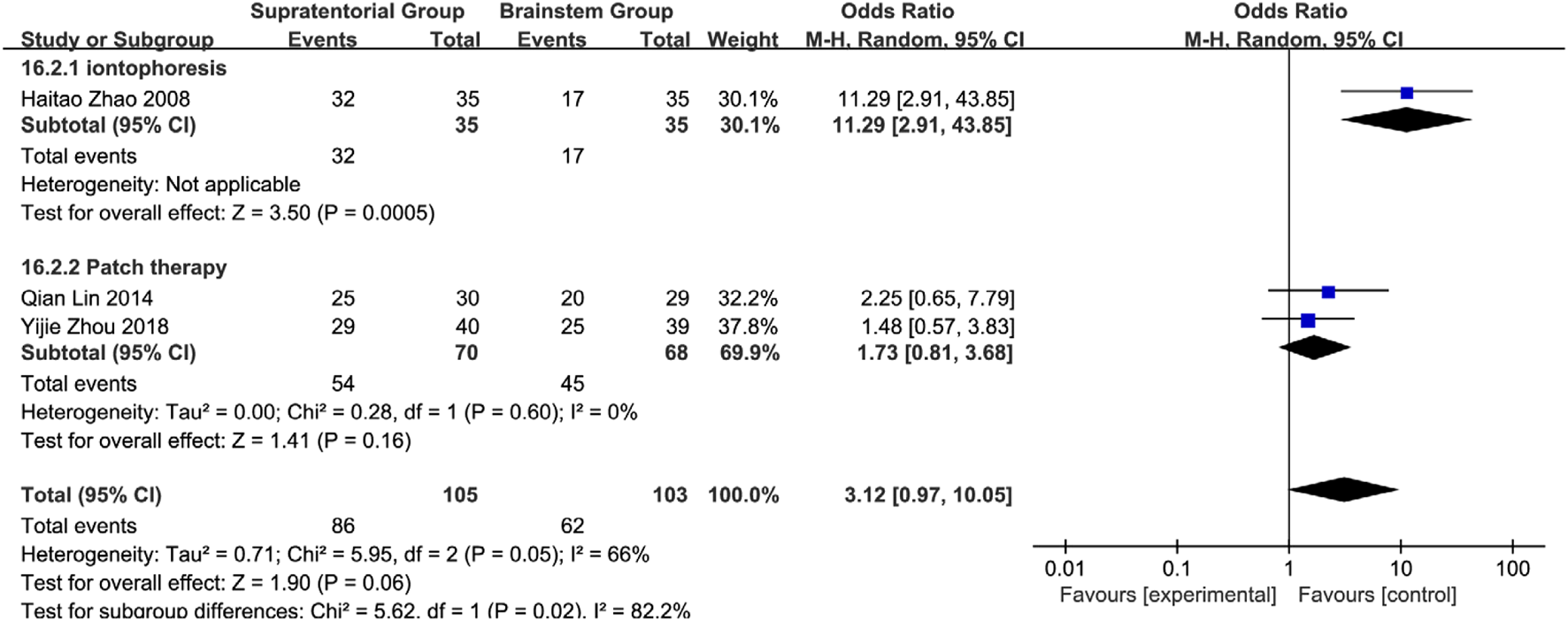

Brainstem subgroup analysis: Iontophoresis: OR = 11.29 (95% CI: 2.91–43.85, P = 0.0005); Acupoint application: OR = 1.73 (95% CI: 0.81–3.68, P = 0.16; I2 = 0%). Overall effect: Pooled OR = 3.12 (95% CI: 0.97–10.05, P = 0.06) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 66%). Subgroup comparison: Iontophoresis showed 6.52-fold superiority over acupoint application (RR = 6.52, 95% CI: 1.35–31.48; subgroup difference: P = 0.02, I2 = 82.2%), indicating its preferential use for brainstem lesions (Figure 26). Efficacy exhibited neuroanatomical specificity: Acupoints are preferred for cerebral hemisphere lesions, while herbal iontophoresis is the best choice for brainstem involvement. This confirms that there is no universal intervention for all PSD mechanisms and establishes the first evidence-based framework for personalized SETCM therapy application.

FIGURE 26

Subgroup analysis of the efficacy of different interventions in patients with stroke foci located in the brain stem.

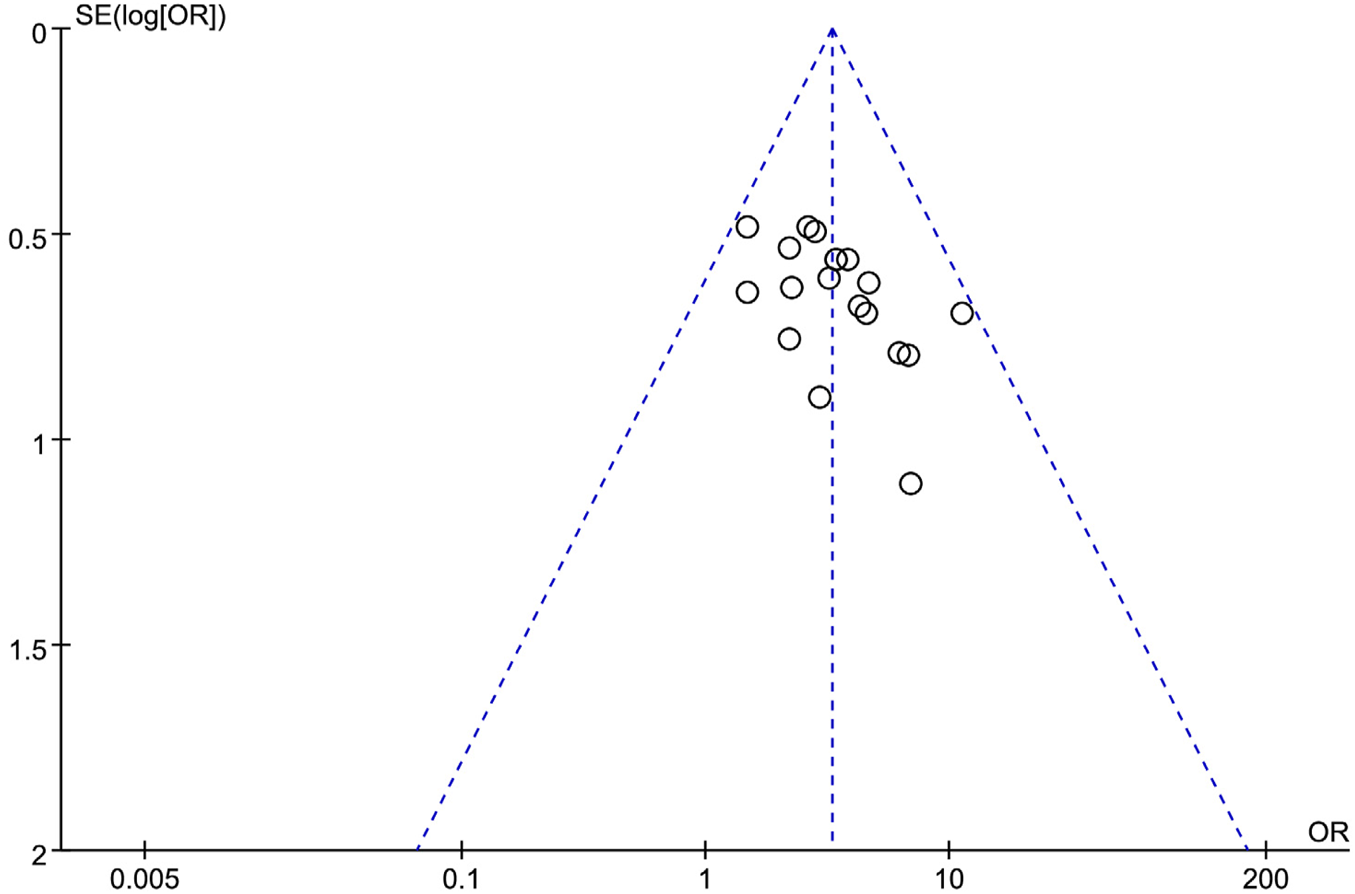

3.6 Publication bias analysis