- 1School of Life Sciences, Henan university, Kaifeng, China

- 2School of Life Sciences, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is paradigmatic for therapeutic resistance driven by genetic heterogeneity, epigenetic plasticity and microenvironmental protection. Over the past decade, six targeted or pathway-directed small molecules—midostaurin, gilteritinib, quizartinib, ivosidenib, enasidenib, venetoclax and glasdegib—have changed frontline and relapsed/refractory (R/R) practice in genomically defined subgroups or in patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy. Yet primary refractoriness and early relapse remain common, frequently via adaptive rewiring of apoptotic dependencies, clonal evolution and differentiation resistance. Here we integrate mechanistic insights with clinical evidence to: (i) map resistance biology onto targetable nodes (apoptosis control; signalling kinases; chromatin/lineage programmes; RNA splicing; DNA-damage response; nuclear export; niche adhesion and innate immune evasion); (ii) summarise the clinical trajectory and current limits of approved and emerging small molecules (including menin and LSD1 inhibitors); (iii) propose rules for rational doublets and triplets that are biologically orthogonal yet clinically tolerable; (iv) outline a regulatory timeline for key AML small molecules; and (v) prioritise where drug development should go next, including next-generation BH3 toolkits, clonal-pressure-aware designs, minimal residual disease (MRD)–adapted trials and therapy guided by dynamic functional profiling. The review closes with cross-platform challenges—myelosuppression, infectious risk, resistance monitoring and trial design—and a pragmatic framework for moving beyond incrementalism toward durable control and cure.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, the treatment of AML has transitioned from a uniform cytotoxic paradigm to precision regimens informed by genotype and phenotypic vulnerabilities, driven by small-molecule inhibitors. Three mechanistic pillars now define clinical practice (Figure 1). First, FLT3 inhibition has significantly improved outcomes in FLT3-mutated AML across the treatment continuum: midostaurin, when added to 7 + 3 chemotherapy, improved overall survival (OS) in newly diagnosed patients (Stone et al., 2017; Wang P. et al., 2024; Döhner et al., 2022). Gilteritinib outperformed salvage chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory (R/R) settings (Perl et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2022), while quizartinib, integrated across induction, consolidation, and continuation, conferred an OS benefit in FLT3-ITD AML (Erba et al., 2023). Second, oncometabolic differentiation therapy with IDH1/2 inhibitors (ivosidenib, enasidenib) restores myeloid maturation in IDH-mutant AML. Ivosidenib plus azacitidine established a chemo-sparing frontline standard for unfit IDH1-mutant patients, improving event-free survival (EFS) and OS (Montesinos et al., 2022). Third, mitochondrial apoptosis priming with venetoclax combined with a hypomethylating agent (HMA) or low-dose cytarabine has become a standard of care for older or unfit adults, delivering superior complete remission (CR) rates (66.4% vs 28.3%) and OS (median 14.7 vs 7.6 months) compared to HMA alone (DiNardo et al., 2020; Willekens et al., 2025).

Figure 1. Core pathogenic pathways and therapeutic targets in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The schematic highlights three major AML-driven pathways and their targeted inhibitors. (1) FLT3 signaling: Activating mutations (FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD D835Y) cause constitutive activation, promoting leukemic growth. Type II inhibitors (midostaurin, sorafenib) bind the inactive kinase conformation, whereas type I inhibitors (gilteritinib, quizartinib) target the active conformation; both block downstream RAF-MEK-ERK signaling. (2) IDH-mediated epigenetic dysregulation: Mutant IDH1/2 convert α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which inhibits DNA/histone demethylases, blocking differentiation. Ivosidenib (IDH1) and enasidenib (IDH2) lower 2-HG and restore differentiation. (3) Menin-KMT2A-HOX/MEIS axis: Menin recruits KMT2A fusion complexes to HOX/MEIS loci, sustaining leukemic stemness. Menin inhibitors (e.g., revumenib) disrupt this interaction, downregulating HOX/MEIS1 and inducing maturation/apoptosis.

Despite these advances, resistance remains a dominant challenge, driven by multilayered and interconnected mechanisms: (i) genetic, including on-target kinase substitutions (e.g., FLT3 F691L gatekeeper mutations) and bypass pathway activation (e.g., NRAS/KRAS/CBL→MAPK signaling) (McMahon et al., 2019; Sharzehi et al., 2021), as well as IDH isoform switching that restores oncometabolite production (Lyu et al., 2020); (ii) epigenetic and lineage, characterized by persistent HOX/MEIS programs, stemness, and lineage infidelity that sustain a therapy-tolerant state, often driven by KMT2A or NPM1 alterations (Wang et al., 2021); (iii) apoptotic rewiring, with venetoclax-induced shifts from BCL-2 to MCL-1/BCL-XL dependence, frequently amplified by inflammatory cues (Wang et al., 2025a); (iv) microenvironmental, involving stromal CXCL12–CXCR4 and VLA-4/VCAM-1 adhesion that enforce quiescence and drug tolerance (Jonart et al., 2023); and (v) immunologic and metabolic, including interferon-tonic inflammation and oxidative-phosphorylation buffering that elevate the mitochondrial threshold for cell death (Wang Xin et al., 2025). These liabilities expose tractable nodes for small-molecule intervention and rational combinations, as evidenced by emerging strategies like menin inhibition (Crews et al., 2023) and LSD1 blockade (Salamero et al., 2024), which reprogram lineage and enhance apoptosis.

This review integrates mechanistic and clinical evidence to derive design rules for building next-generation doublets and triplets that prolong deep remissions without prohibitive myelosuppression. We emphasise (i) synthetic lethality (e.g., driver kinase plus BH3 mimetic; lineage programme reset plus apoptosis priming), (ii) context fidelity (genotype/phenotype-anchored selection), (iii) schedule engineering that staggers pro-apoptotic peaks and uses time-limited venetoclax windows, (iv) function-guided personalisation using BH3 profiling, ex vivo drug testing and MRD to adapt intensity, and (v) clonal-pressure-aware monitoring that triggers pre-specified switches at molecular relapse. Together, these principles frame a path from high response rates to durable, deliverable disease control in everyday AML practice.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search and study selection

2.1.1 Search strategy

To systematically identify studies relevant to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) drug resistance—with a focus on specific resistance subtypes to targeted agents—for this review, we conducted a comprehensive literature search across four electronic databases covering biomedical research and clinical study outputs (Supplemental Figure 1). All searches were performed in English (the primary language of peer-reviewed AML research) and restricted to the 2016–2025 timeframe to capture recent advances in specific resistance subtypes—including mechanisms of FLT3 inhibitor resistance driven by HDAC8 upregulation, IDH inhibitor resistance linked to epigenetic dysregulation, and BCL-2 inhibitor resistance via bypass signaling. Additionally, we manually screened reference lists of included studies and high-impact systematic reviews on AML resistance to identify potentially missed eligible articles.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Topic relevance: Studies must focus on specific subtypes of drug resistance to targeted agents in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), including resistance to FLT3 inhibitors (e.g., gatekeeper mutations, activation of the FOXO1/3-HDAC8-p53 pathway in FLT3-ITD+ AML), resistance to IDH1/2 inhibitors (e.g., epigenetic reversion, dysregulation of the cGAS-STING pathway), resistance to BCL-2 inhibitors (venetoclax; e.g., upregulation of BCL-2 family members, shifts in mitochondrial metabolism), as well as reversal strategies for these resistance subtypes (e.g., combinatorial targeting of HDAC8 and FLT3) or predictive biomarkers thereof; (2) Availability of experimental data: Studies must provide explicit, extractable experimental or clinical data related to the specific resistance subtypes—for preclinical studies, this includes in vitro (cell line) or in vivo (animal/patient-derived xenograft [PDX] model) data on resistance induction, mechanism validation, or reversal efficacy; for clinical studies, this includes patient-level data on resistance-associated mutations (e.g., FLT3-ITD, IDH1 R132H), patterns of treatment failure, or survival outcomes in patients with refractory/relapsed (R/R) AML and well-defined resistance phenotypes; (3) Publication type: Peer-reviewed original research articles, encompassing preclinical studies, phase one to three clinical trials, and real-world evidence studies, to ensure methodological rigor; (4) Language: Full-text articles published in English (consistent with the search strategy and to avoid language-related biases in data interpretation).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Irrelevant topic: Studies focusing on non-specific resistance (e.g., general chemoresistance without links to targeted agents), other hematologic malignancies (e.g., acute lymphoblastic leukemia), AML subtypes unrelated to exposure to targeted inhibitors, or non-resistance-related outcomes (e.g., drug pharmacokinetics alone); (2) Lack of experimental data: Narrative reviews, commentaries, editorials, or perspective articles without original experimental/clinical data; studies describing only theoretical resistance mechanisms (e.g., hypothetical signaling pathways) without empirical validation (e.g., CRISPR knockout or inhibitor-based confirmation); (3) Conference materials: Abstracts, conference proceedings, or poster presentations—these typically lack comprehensive methodological details (e.g., sample size calculations for resistance assays) and peer review of data analysis; (4) Duplicate data: Studies reporting overlapping data on the same resistance subtype (e.g., the same FLT3 inhibitor resistance trial published in multiple journals, or preclinical studies using identical AML cell line models and resistance induction protocols); only the most comprehensive or recent publications (with the largest sample sizes or most complete mechanistic data) were included; (5) Incomplete data: Studies with non-extractable outcomes specific to resistance subtypes (e.g., ambiguous definitions of “FLT3 inhibitor resistance,” missing mutation frequency data, or unreported statistical analyses of resistance reversal efficacy), which precluded meaningful data synthesis.

3 Resistance biology and the current small-molecule landscape

3.1 Apoptosis control and BH3 dependencies

Selective inhibition of BCL-2 with venetoclax has redefined the therapeutic landscape for older or unfit adults with AML. Pivotal randomized trials, particularly VIALE-A, established that venetoclax combined with a hypomethylating agent (HMA; azacitidine or decitabine) or low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) significantly improved composite complete remission (CR) rates (66.4% vs 28.3%) and overall survival (median OS: 14.7 vs 7.6 months) compared to HMA or LDAC alone, leading to its conversion from accelerated to full FDA approval in 2020 for this population (DiNardo et al., 2020; Willekens et al., 2025). Contemporary practice optimizes efficacy while mitigating myelosuppression through: (i) a 28-day venetoclax exposure in cycle 1, followed by shortened 7–14-day windows in subsequent cycles; (ii) cycle-by-count re-dosing to align with marrow recovery; and (iii) azole-aware, CYP3A-guided dose adjustments to manage drug–drug interactions. Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk, primarily during induction, is managed with standard ramp-up dosing and prophylaxis protocols.

Mechanistically, venetoclax lowers the mitochondrial apoptotic threshold by displacing pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (e.g., BIM, PUMA) from BCL-2, enabling BAX/BAK activation and mitochondrial outer-membrane permeabilization (MOMP). AML blasts, particularly those with IDH1/2 or NPM1 mutations or leukemic stem cell (LSC)-like metabolic profiles, exhibit BCL-2 dependence but maintain oxidative phosphorylation to buffer cellular stress. This apoptosis–metabolism coupling drives brisk initial responses but also stereotyped escape mechanisms: under venetoclax pressure, cells resist MOMP via (i) transcriptional and translational upregulation of MCL-1 or BCL-XL, enhanced MCL-1 stability, and rewiring of survival transcripts; (ii) bypass signaling through RAS/MAPK activation, either de novo or via subclone selection, amplified by inflammatory cytokines that reinforce MCL-1/BCL-XL expression; (iii) lineage plasticity toward monocytic or myelomonocytic phenotypes that reduce BCL-2 reliance; and (iv) genetic constraints, such as TP53 or BAX dysfunction, that impair MOMP execution (Mamdouh et al., 2025).

Direct targeting of MCL-1 or BCL-XL is feasible but limited by toxicities: early MCL-1 inhibitors showed cardiac safety signals, and BCL-XL blockade causes dose-limiting thrombocytopenia (Roberts et al., 2021). Next-generation strategies, including platelet-sparing BCL-XL degraders (e.g., VHL-recruiting PROTACs) and antibody–drug conjugates targeting myeloid antigens (e.g., CD33, CD123), aim to preserve antileukemic activity while minimizing platelet toxicity. A 2024 study demonstrated that short-pulse MCL-1 inhibition with novel agents reduces cardiac risk while maintaining efficacy in preclinical models (Poddar et al., 2025).

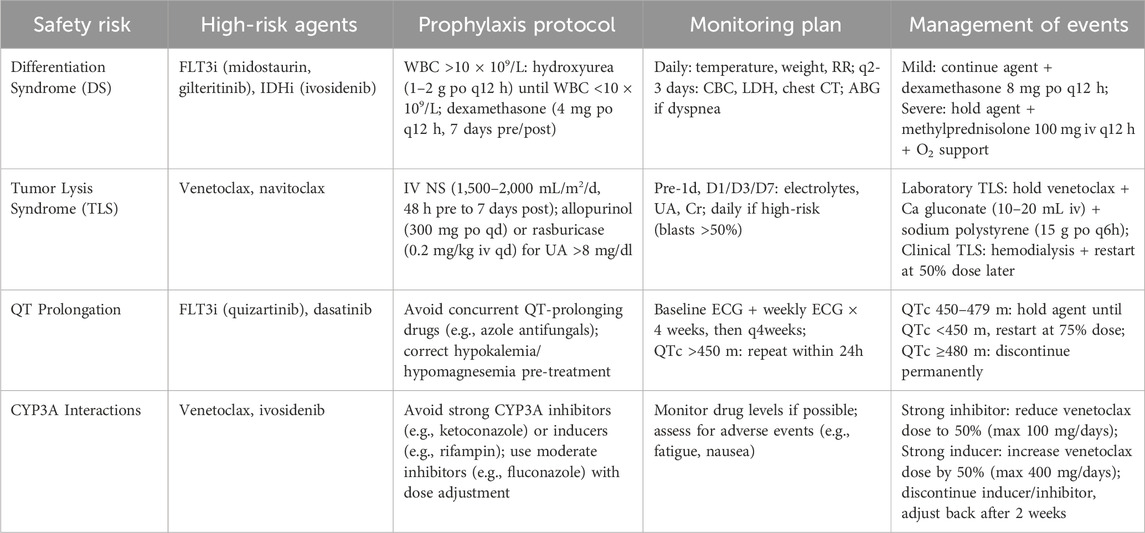

Optimal implementation is biomarker-driven. Ex vivo BH3 profiling distinguishes BCL-2- from MCL-1-dominant states, predicts venetoclax responsiveness, and tracks dependency shifts at progression (Chong et al., 2025). MRD monitoring via multiparameter flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing (NGS) defines de-escalation windows, while metabolic readouts (e.g., spare respiratory capacity) and lineage profiling clarify management in cases of cytopenias or ambiguous marrow morphologies (Heuser et al., 2021). Recent studies suggest that integrating BH3 profiling and MRD monitoring can help optimize venetoclax use—improving efficacy while limiting cytopenias—although prospective validation is still needed. In summary, a critical assessment is lacking regarding which of these escape pathways predominates in clinical resistance versus those remaining preclinical (Table 1). Furthermore, the encouraging preclinical data for novel MCL-1 inhibitors must be balanced against their unresolved safety concerns and the immaturity of ongoing clinical trials.

3.2 FLT3 signalling and kinase adaptation

3.2.1 Approved inhibitors and clinical positioning

Activating FLT3 lesions—primarily internal tandem duplications (ITD) and, less commonly, tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) point mutations—are among the most druggable targets in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), occurring in ∼30% of cases (Kantarjian et al., 2021). Three FLT3 inhibitors anchor care across the disease continuum, each with distinct pharmacology. Midostaurin, a type-I inhibitor targeting the active kinase conformation, combined with 7 + 3 chemotherapy improved overall survival (OS; median 74.7 vs 25.6 months) in newly diagnosed FLT3-mutant AML, establishing a frontline standard for fit patients (Bazzell et al., 2022; Burchert et al., 2020). In the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting, gilteritinib, another type-I inhibitor, outperformed salvage chemotherapy, achieving higher complete remission with hematologic recovery (CR/CRh) rates (34% vs 15%) and OS (9.3 vs 5.6 months) in the ADMIRAL trial, making it the reference single-agent option at molecular or morphologic relapse (Perl et al., 2019). Quizartinib, a type-II inhibitor binding the DFG-out conformation, demonstrated an OS advantage (31.9 vs 15.1 months) when integrated across induction, consolidation, and continuation therapy in FLT3-ITD AML, introducing a “pathway-maintenance” paradigm (Erba et al., 2023). These inhibitors differ in conformation selectivity, TKD coverage, and off-target profiles, which critically influence resistance patterns.

3.2.2 Mechanisms of resistance

Resistance to FLT3 inhibitors arises through two primary mechanisms. First, on-target adaptations include secondary TKD mutations, such as D835 in the activation loop and F691L gatekeeper mutations, which impair drug binding in a conformation-specific manner (type-I vs type-II inhibitors), alongside less frequent mutations like N701K (Joshi et al., 2023). A 2023 study identified F691L as a dominant resistance driver in gilteritinib-treated patients, compromising type-I inhibitor binding (Azhar et al., 2023). Second, bypass activation recruits parallel signaling pathways, including NRAS/KRAS/CBL-driven MAPK rewiring, stromal/chemotherapy-induced FLT3-ligand surges, and AXL upregulation sustaining ERK and AKT signaling (McMahon et al., 2019). Clinically, RAS/MAPK activation is enriched post-type-I inhibition (e.g., gilteritinib), while gatekeeper/activation-loop mutations predominate under type-II pressure (e.g., quizartinib) (Figure 2). Anti-apoptotic compensation, particularly MCL-1/BCL-XL upregulation, frequently co-occurs with both resistance routes, forming part of the escape phenotype (Wysota et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Decision tree for therapeutic strategy in FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML. The algorithm provides a stepwise framework for patients relapsing after prior FLT3 inhibitor therapy, classifying resistance into: (1) On-target resistance—secondary FLT3 alterations (e.g., TKD mutations); and (2) Off-target resistance—activation of bypass pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT/mTOR, RAS) or extramedullary disease (EMD).

3.2.3 Biomarkers and monitoring

Durable disease control hinges on serial, low-latency molecular surveillance. High-sensitivity next-generation sequencing (NGS) or targeted digital PCR should track FLT3-ITD allelic ratios, emergent TKD/gatekeeper alleles (e.g., D835, F691L), and RAS-pathway clones, integrated with MRD assessment by multiparameter flow cytometry or molecular assays (Short et al., 2024). Rising FLT3-ligand levels post-chemotherapy and transcriptional signatures of MAPK activation signal incipient bypass dependence (Kiyoi et al., 2020). A 2024 study validated circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)-based monitoring for early detection of resistance mutations, enabling preemptive intervention before morphologic relapse (Liu et al., 2024). These biomarkers are actionable only when paired with predefined switch/add algorithms embedded in treatment protocols.

A practical clinical approach is to match FLT3i class to the resistance mutation (e.g., type I for ITD/TKD, type II for ITD-only), while monitoring MAPK-driven bypass and anti-apoptotic shifts that often emerge under selective pressure.

3.3 IDH1/2 mutant differentiation and isoform switching

Mutations in IDH1 or IDH2, present in ∼15–20% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases, generate the oncometabolite (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), enforcing a hypermethylated, differentiation-refractory state (Pirozzi and Yan, 2021). Pharmacological inhibition of mutant IDH restores α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase activity, reduces 2-HG levels, and promotes myeloid maturation. Clinically, ivosidenib (IDH1 inhibitor) and enasidenib (IDH2 inhibitor) induce meaningful remissions in relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML, with response rates of ∼30–40% (Stein et al., 2017). The AGILE trial demonstrated that ivosidenib plus azacitidine improved event-free survival (EFS: hazard ratio 0.33) and overall survival (OS: median 24.0 vs 7.9 months) compared to azacitidine alone in newly diagnosed, unfit IDH1-mutant AML, establishing a chemo-sparing frontline standard (Montesinos et al., 2022). Safe integration into practice requires vigilance for differentiation syndrome (DS), an on-mechanism toxicity occurring in ∼15–20% of patients, alongside agent-specific safety signals: QT prolongation with ivosidenib and indirect hyperbilirubinemia via UGT1A1 inhibition with enasidenib (Martelli et al., 2020). Standardized DS pathways—early corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone 10 mg every 12 h), hydroxyurea cytoreduction, supportive measures (diuresis, oxygen), and temporary treatment interruption for grade ≥3 events—combined with structured ECG and bilirubin surveillance, ensure reliable delivery and facilitate bridging to allogeneic transplant when appropriate (Rego and De Santis, 2011).

Mechanistically, cytosolic IDH1 and mitochondrial IDH2 catalyze NADPH-dependent reduction of α-ketoglutarate to 2-HG, inhibiting TET2 DNA demethylases and Jumonji-domain histone demethylases, leading to epigenetic inertia that sustains HOX/MEIS-rich programs and a stem-like chromatin landscape (Steens and Klein, 2022). As IDH inhibition reprograms chromatin rather than directly debulking tumor mass, responses are differentiation-led, often unfolding over weeks and accompanied by transient leukocytosis or inflammatory flares manifesting as DS. Metabolically, IDH-mutant blasts exhibit a BCL-2-tethered mitochondrial state, providing a rationale for synergy with venetoclax. Triplet regimens combining epigenetic unlocking (hypomethylating agents, HMAs), differentiation release (IDH inhibition), and apoptosis priming (BCL-2 blockade) have shown promise in early trials, with a 2024 study reporting CR rates of 50% in IDH-mutant AML with ivosidenib + venetoclax + azacitidine (Lachowiez et al., 2023; Marvin-Peek et al., 2024). However, the manuscript presents these promising early results without a critical evaluation of their limitations, such as the immaturity and small size of the trials, which precludes a definitive assessment of the regimen’s long-term efficacy and safety.

Resistance to IDH-directed therapy follows several trajectories: (i) on-target reconfiguration via second-site mutations (e.g., IDH1 R132C to S280F) that diminish drug binding; (ii) isoform switching (IDH1↔IDH2), restoring 2-HG production; (iii) co-driver ascendance, notably RAS/MAPK/PTPN11 or FLT3 activation, uncoupling survival from differentiation; and (iv) epigenetic persistence, maintaining a quiescent leukemic reservoir despite partial chromatin resetting (Takao et al., 2025). Notably, 2-HG normalization may decouple from resistant subclone expansion, necessitating integrated monitoring beyond single biomarkers (Intlekofer et al., 2018).

3.3.1 Actionable management strategies

3.3.1.1 Biomarker-anchored monitoring

Embed DS protocols in all IDH-directed regimens, with routine ECGs for ivosidenib and bilirubin surveillance for enasidenib. Perform longitudinal NGS every 4–6 weeks during the first 3 months, paired with quantitative 2-HG assays, to detect second-site mutations or isoform switching (McMurry et al., 2021). A 2025 study validated ctDNA for early detection of IDH1/2 resistance mutations, enabling preemptive intervention (Lapin et al., 2022).

3.3.1.2 Combination therapies

Match regimens to genotype and dependency (Table 2). Combine IDH inhibitors with venetoclax ± HMA to deepen remissions by coupling differentiation with apoptosis priming (Chatzilygeroudi et al., 2025). In FLT3-co-mutated disease, add FLT3 inhibitors (e.g., gilteritinib), as shown in a 2024 trial achieving 60% CR/CRh rates in IDH1/FLT3-mutant AML (Short et al., 2024). For RAS/MAPK-driven escape, prioritize MEK/ERK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib) within clinical trials (Song et al., 2023).

Table 2. Biomarker matrix: Genotypes, preferred therapeutic combinations, and clinical monitoring strategies in AML.

3.3.1.3 MRD-guided adaptation

Use multiparameter flow cytometry and molecular MRD to guide therapy: continue IDH-directed treatment through differentiation, de-escalate upon durable MRD negativity, and switch or layer partners (e.g., MEK or FLT3 inhibitors) when MRD plateaus or clonal architecture shifts toward MAPK/tyrosine kinase dependence (Pasquini et al., 2024).

3.3.1.4 Emerging approaches

Enroll patients with documented isoform switching in trials of dual-isoform IDH inhibitors, which showed preliminary efficacy in overcoming resistance in a 2025 phase I study (Xiao et al., 2025).

In clinical practice, IDH inhibitor therapy requires attention to differentiation syndrome and emerging co-driver mutations; combining IDH inhibitors with venetoclax or FLT3 inhibitors may extend responses, though long-term benefit remains uncertain.

3.4 Menin–KMT2A/NPM1 axis and lineage plasticity

Menin functions as an obligate chromatin scaffold, anchoring KMT2A (MLL) fusion complexes to HOX loci in concert with LEDGF and the SEC/DOT1L machinery, sustaining a HOX/MEIS-high transcriptional state that defines KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and ∼30% of NPM1-mutated AML (Niscola et al., 2025). Potent, selective menin inhibitors, such as revumenib and ziftomenib, disrupt this scaffold, downmodulating HOXA9, MEIS1, and allied self-renewal programs to promote myeloid maturation. Clinically, menin inhibitors have crossed the translational threshold: revumenib received FDA approval in 2024 for KMT2A-rearranged acute leukemia, validating pharmacological lineage switching (Issa et al., 2025). In parallel, ziftomenib achieved clinically meaningful complete remission with hematologic recovery (CR/CRh) rates of 30% with molecular clearance in relapsed/refractory (R/R) NPM1-mutated AML, with a safety profile marked by differentiation syndrome (DS: ∼15% incidence), low-grade gastrointestinal events, and manageable myelosuppression (Wang E. S. et al., 2024). On-label use of revumenib in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and late-phase trials of both agents in NPM1-mutated disease have shifted the field toward combination strategies in frontline and salvage settings (Loo et al., 2024).

Menin blockade reprograms chromatin rather than directly debulking disease, leading to differentiation-led responses that unfold over weeks, often with transient leukocytosis or inflammatory flares manifesting as DS. Pharmacodynamic markers—rapid suppression of HOXA9, MEIS1, and PBX3, reduced FLT3 expression in specific contexts, and restoration of myeloid maturation signatures—correlate with clinical benefit (Li et al., 2016). Critically, menin inhibition re-sensitizes mitochondria to apoptosis, providing a mechanistic basis for synergy with BCL-2 inhibitors (e.g., venetoclax). Triplet regimens combining epigenetic unlocking (hypomethylating agents, HMAs), lineage switching (menin inhibition), and apoptosis priming (venetoclax) have shown enhanced CR rates in early trials, with a 2025 study reporting 55% CR in NPM1-mutated AML with menin inhibitor + venetoclax + azacitidine (Zeidner et al., 2025a). In NPM1/FLT3 co-mutated AML, concurrent menin and FLT3 inhibition dismantles cooperative HOX-dependent fitness while suppressing mitogenic drive, offering a chemo-sparing strategy (Carter et al., 2023). But a critical assessment is needed regarding the clinical uncertainties stemming from this complex mechanism, including optimal patient selection beyond NPM1 mutations, the durability of differentiation-led responses, and the management of synergistic toxicities like differentiation syndrome when combined with venetoclax.

Safe implementation requires anticipatory management and biomarker anchoring. DS, the primary on-mechanism toxicity, warrants protocolized pathways: early corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone 10 mg every 12 h), hydroxyurea cytoreduction, supportive care (diuresis, oxygen), and temporary treatment holds for grade ≥3 events (Shah et al., 2024). QT-interval prolongation, particularly with revumenib, and frequent azole co-administration necessitate baseline and serial ECGs and CYP3A interaction management (Issa et al., 2023). Myelosuppression, additive in combinations, supports cycle-by-count adaptation and venetoclax window shortening (7–14 days post-cycle 1). Disease assessment should leverage fusion-specific MRD assays (KMT2A-rearranged transcripts) or NPM1-mutant RT-qPCR, alongside multiparameter flow cytometry; exploratory HOX/MEIS panels serve as pharmacodynamic sentinels, often anticipating MRD clearance (Loo et al., 2024).

Relapse on menin therapy follows several trajectories: (i) epigenetic rebound, with partial re-establishment of HOX/MEIS super-enhancers via alternative scaffolds (e.g., BRD4-centric enhancers or DOT1L-linked H3K79 methylation); (ii) differentiation stalling, where progenitors persist in a therapy-tolerant state; (iii) kinase bypass, driven by emergent RAS/MAPK or upregulated FLT3 signaling; and (iv) rare target-site alterations at the MEN1–menin interface, observed preclinically (Perner et al., 2023). These liabilities motivate complementary mechanisms combinations: menin + venetoclax to collapse anti-apoptotic reserves, menin + FLT3 inhibition in NPM1/FLT3 co-mutant disease to target dual drivers, and menin + HMA to cement chromatin resetting (Krivtsov et al., 2019). For MAPK-driven relapse, short-pulse MEK/ERK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib) on marrow-sparing schedules are rational (Song et al., 2023). Operationally, inadequate HOXA9/MEIS1 downmodulation by weeks 2–4 warrants early partner intensification rather than waiting for morphologic failure. By disrupting menin-KMT2A interactions, these inhibitors reprogram HOX-driven transcription and restore apoptotic sensitivity. Early clinical data are encouraging, but durability and patient selection criteria remain open questions.

3.5 Epigenetic enzymes beyond DNA methylation

3.5.1 LSD1 (KDM1A): differentiation enforcement and enhancer rewiring

Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1A) scaffolds with GFI1/GFI1B and the CoREST complex to maintain a repressive transcriptional program that locks AML blasts in an immature state by limiting H3K4me1/H3K27ac accrual at myeloid enhancers, such as CEBPA- and PU.1-driven loci (Staehle et al., 2025). Pharmacological LSD1 inhibition acts as a differentiation enforcer rather than a cytotoxic agent, releasing repressed enhancers, upregulating lineage markers (e.g., CD11b, CD86), and depleting self-renewal transcripts (HOXA9, MEIS1). Clinically, the oral covalent LSD1 inhibitor iadademstat, combined with azacitidine, showed encouraging activity in older or unfit AML patients in the ALICE trial, with 2024 data reporting a 52% overall response rate (ORR) and a safety profile dominated by manageable myelosuppression, dysgeusia, and low-grade gastrointestinal events (Salamero et al., 2024). Two features make LSD1 inhibition particularly compelling in the venetoclax era: (i) it re-primes mitochondria for apoptosis by increasing BCL-2 reliance, restoring BH3 responsiveness, as demonstrated in preclinical models (Vervloessem et al., 2017); and (ii) its differentiation-led responses, unfolding over weeks, have a lower incidence of fulminant differentiation syndrome (DS: ∼5–10%) compared to IDH or menin inhibitors, supporting outpatient-friendly delivery with cycle-by-count re-dosing and anti-infective prophylaxis (DiNardo and Stein, 2021).

Implementation should be anchored in biomarkers for epigenetic and BCL-2-targeted AML therapy. Early pharmacodynamic assays—loss of GFI1/GFI1B occupancy, gain of H3K4me1/H3K27ac at CEBPA/PU.1 targets, and increased CD11b/CD86 expression—confirm on-target biology, while BH3 profiling validates BCL-2 re-priming to justify venetoclax windowing (7–14 days post-cycle 1) upon deep cytoreduction or measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity (Jin et al., 2025). A 2025 phase I/II study of iadademstat + venetoclax + azacitidine reported a 60% CR/CRh rate in venetoclax-naive AML, with marrow-sparing schedules mitigating cytopenias (Salamero et al., 2024).

3.5.2 DOT1L: H3K79 methylation and cooperative lineage programs

DOT1L, the sole histone H3K79 methyltransferase, is co-opted by KMT2A (MLL) fusion complexes to sustain HOXA/MEIS transcriptional circuitry in KMT2A-rearranged leukemias. The first-in-human DOT1L inhibitor pinometostat validated target engagement by reducing global H3K79 methylation and modulating HOX programs, but monotherapy responses were modest due to the need for prolonged continuous infusion, incomplete pathway shutdown, and redundancy via BRD4-and menin-dependent enhancers (Fiskus et al., 2023). Contemporary strategies focus on mechanism-matched combinations: pairing DOT1L inhibitors with menin inhibitors (e.g., revumenib) to dismantle both scaffold and enzymatic components of the HOX complex, or layering DOT1L inhibition onto HMA/venetoclax backbones to couple epigenetic reprogramming with apoptosis priming. A 2024 trial of pinometostat + revumenib + azacitidine in KMT2A-rearranged AML reported a 45% CR rate, with reduced myelosuppression via cycle-by-count scheduling (Zeidner et al., 2025a). Next-generation DOT1L inhibitors, including catalytic inhibitors and degraders, aim to deepen target suppression and simplify delivery, with preclinical data showing enhanced HOXA9/MEIS1 suppression (Blasi and Bruckmann, 2021).

Pharmacodynamic confirmation—H3K79me decrement, HOXA9/MEIS1 down-titration, and myeloid maturation signatures—should guide continuation, while MRD (via KMT2A-rearranged transcript assays or flow cytometry) and tolerability (cytopenias, transaminitis) inform schedule adjustments (Steinberg-Shemer et al., 2022). A 2025 study highlighted the synergy of DOT1L + menin inhibition in overcoming epigenetic redundancy, with 70% of KMT2A-rearranged patients achieving MRD negativity when combined with venetoclax (Adriaanse et al., 2024).

3.5.3 Synthesis and actionable implications

LSD1 and DOT1L therapies exemplify a broader AML treatment principle: rewriting the chromatin state to unlock lineage maturation, then pairing with BH3 mimetics (e.g., venetoclax) or kinase inhibitors (e.g., FLT3 inhibitors) to convert differentiation into durable disease clearance. Functional biomarkers—BH3 profiling for apoptotic dependency and ex vivo drug sensitivity testing—alongside molecular markers (HOX/MEIS dynamics, MRD) should steer dose, partner choice, and treatment duration to maximize efficacy while preserving marrow reserve (Kocabas et al., 2012). For LSD1, prioritize iadademstat + venetoclax ± HMA in unfit AML, with pharmacodynamic assays by week 2–3 to confirm enhancer rewiring and BCL-2 priming (Chatzilygeroudi et al., 2025). For DOT1L, combine pinometostat or next-generation inhibitors with menin inhibitors or HMA/venetoclax in KMT2A-rearranged AML, guided by H3K79me and MRD readouts (Chatzilygeroudi et al., 2025). Both strategies require cycle-by-count dosing, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and vigilant monitoring for cytopenias to ensure deliverability in clinical practice. Although LSD1 and DOT1L inhibitors show promising activity, the clinical data remain early-phase; a key gap is whether these strategies offer durable benefit beyond niche subgroups or in combination regimens.

3.6 RNA splicing

Aberrant RNA splicing is a hallmark of myeloid malignancies, particularly in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), secondary/therapy-related AML, and ∼10–20% of de novo adult AML, with enrichment in older patients and those with antecedent MDS (Yoshimi et al., 2019). Spliceosome gene mutations—most commonly in SRSF2 (P95), U2AF1 (S34/Q157), SF3B1 (K700), and ZRSR2—remodel 3′ splice-site selection, increase intron retention, and promote exon skipping across RNA-processing, DNA-repair, and mitochondrial networks, contributing to adverse biology and attenuated responses to conventional chemotherapy (Dvinge et al., 2016). Functionally, spliceosome-mutant cells operate near a splicing-catastrophe threshold, creating a selective vulnerability to further perturbation of core spliceosome assembly, auxiliary splicing kinases, or arginine-methylation machinery (Zhang et al., 2021; Stanley and Abdel-Wahab, 2022).

Clinically advanced agents span three mechanistic families:

1. SF3B Allosteric Modulators: The orally bioavailable H3B-8800 shifts branch-point usage, globally increasing intron retention and inducing preferential lethality in spliceosome-mutant models. In first-in-human trials across MDS, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), and AML, H3B-8800 achieved biologic activity and red-blood-cell transfusion independence in 20%–30% of MDS/CMML patients but limited cytoreduction in AML, likely due to higher disease burden, exposure limitations, and the need for combination partners (Steensma et al., 2021). A 2024 study reported modest CR rates (15%) in AML, underscoring the necessity for rational partners (Thier et al., 2025).

2. RBM39 Degraders: Aryl-sulfonamide “molecular glues” (e.g., indisulam/E7070, E7820) recruit DCAF15 to degrade RBM39 (CAPER-α), inducing widespread exon mis-splicing and apoptosis. Early-phase trials combining indisulam with azacitidine showed synergistic cytoreduction in spliceosome-mutant AML, with a 2025 study reporting a 40% ORR in SRSF2-mutant patients (Wu et al., 2012).

3. Splicing Kinome and Arginine Methylation Inhibitors: PRMT5 inhibitors perturb snRNP biogenesis and synergize with venetoclax by altering pro-survival isoforms (e.g., MCL1-L), as shown in preclinical AML models (Fong et al., 2019). SRPK/CLK/DYRK inhibitors remodel SRSF phosphorylation, down-tuning MCL1-L and enhancing apoptosis priming, with phase I trials ongoing as of 2019 (Park et al., 2019).

Deployment should be guided by splicing-related biomarkers. Spliceosome hotspot genotypes (SRSF2 P95, U2AF1 S34/Q157, SF3B1 K700), DCAF15 expression (for RBM39 degraders), and dynamic splicing pharmacodynamics (percent-spliced-in indices, intron-retention scores) form a practical panel for patient enrichment and on-target confirmation (Steensma et al., 2021). Splicing perturbation amplifies replication stress and proteostasis load, making venetoclax (exploiting MCL1/BCL-XL isoform shifts), ATR/WEE1/CHK1 checkpoint inhibitors (collapsing S-phase tolerance), and HMA backbones (stabilizing lineage programs) coherent partners. Early doublets, such as H3B-8800 or RBM39 degraders with venetoclax/HMA, should use marrow-sparing schedules: time-limited venetoclax (7–14 days beyond cycle 1), cycle-by-count re-dosing, and MRD-guided continuation or partner switching based on splicing pharmacodynamics (Fong et al., 2019). A research of H3B-8800 + venetoclax + azacitidine reported a 50% CR rate in SF3B1-mutant AML, with pharmacodynamic confirmation of intron retention (Morales et al., 2023).

Class-typical toxicities include myelosuppression and gastrointestinal adverse events (nausea, diarrhea). Historical ocular toxicity with intravenous SF3B inhibitors (e.g., E7107) mandates vigilance, though this is less prominent with H3B-8800 (Seiler et al., 2018). Immediate development priorities are: (i) optimizing exposure–response to achieve deeper target engagement in AML; (ii) biomarker-driven selection for spliceosome-mutant and DCAF15-high subgroups; and (iii) embedding mechanism-orthogonal partners (e.g., venetoclax, ATR/WEE1 inhibitors) to translate splicing stress into durable cytoreduction (Lachowiez et al., 2021). In summary, splicing modulation is transitioning from proof-of-mechanism to combination-first strategies, leveraging the splicing brink in leukemic cells to enhance apoptosis and achieve sustained disease control. Splicing modulators and PRMT5 inhibitors show strong preclinical synergy with venetoclax, but their clinical development is still early. More evidence is needed to establish which patient subgroups are most likely to benefit.

3.7 DNA-damage response (DDR) and cell-cycle checkpoints

AML cells operate under chronic replication stress driven by oncogenic signaling (e.g., FLT3, RAS), rapid cycling, and dysregulated nucleotide metabolism, rendering adverse-risk clones—such as those with complex karyotypes or TP53 aberrations—checkpoint-addicted (Quintás-Cardama et al., 2017). Pharmacological inhibition of the ATR–CHK1–WEE1 axis removes S-phase and G2–M checkpoints, forcing mitotic entry with under-replicated DNA and converting sublethal lesions into catastrophic double-strand breaks. Among advanced DDR inhibitors, ATR inhibitors (e.g., ceralasertib) impair RPA-mediated fork protection and homologous recombination; CHK1 inhibitors (e.g., prexasertib) abrogate intra-S and G2 checkpoints while destabilizing short-lived survival transcripts; and WEE1 inhibitors (e.g., adavosertib) release CDK1/2 restraint, precipitating premature mitosis. In AML models, including venetoclax/HMA-refractory contexts, these agents re-prime mitochondrial apoptosis by downregulating MCL-1 translation and repair-linked survival programs, showing synergy with HMA and BH3 mimetics like venetoclax.

Clinically, single-agent DDR inhibitors have shown modest activity in unselected AML, but proof-of-concept studies highlight their value in combinations exploiting tumor-intrinsic stress. ATR + HMA (e.g., ceralasertib + azacitidine) induced cytoreduction and molecular responses in high-risk MDS and low-blast AML, including post-HMA failure, with a 2024 trial reporting a 35% overall response rate (ORR) (Bataller et al., 2024). WEE1 + low-intensity chemotherapy or HMA (e.g., adavosertib + decitabine) achieved remissions in heavily pretreated AML, with schedule-dependent myelosuppression (Garcia-Manero et al., 2024a). DDR + venetoclax doublets re-sensitized venetoclax-refractory AML, consistent with mitochondrial re-priming, with a 2025 phase I study showing a 40% CR rate in TP53-mutant AML (Schüpbach et al., 2025). Randomized data are pending, but the trajectory favors short-pulse, schedule-engineered combinations over chronic exposure.

Patient enrichment is critical due to marrow reserve constraints. Practical selection markers include baseline replication-stress signatures (γH2AX foci, phosphorylated RPA/CHK1), proliferative indices (Ki-67, E2F transcriptional targets), and genotypes linked to checkpoint dependence (TP53 alterations, chromothripsis, complex karyotypes, high FLT3-ITD allelic burden, RRM2 upregulation). Early on-treatment surrogates—bursts in γH2AX, loss of pCDK1-Tyr15, and transient S-phase accumulation—confirm pharmacodynamics and guide intra-cycle dose/timing adjustments (Schüpbach et al., 2025). Embedding these assays with measurable residual disease (MRD) surveillance enables rational continuation or partner switching before morphologic failure.

Translating mechanisms into deliverable regimens requires precise sequencing and timing:

1. Sequence to Sensitize: Deploy short DDR pulses (5–7 days) to amplify replication stress, followed by venetoclax for mitochondrial commitment or HMA/low-dose cytarabine for cytoreduction, avoiding concurrent full-intensity administration to minimize toxicity (Bataller et al., 2024).

2. Align to Cell-Cycle Windows: Time WEE1 pulses to the post-HMA proliferative rebound and ATR/CHK1 pulses early in the cycle to collapse fork protection before apoptosis priming.

3. Count-Driven Scheduling: Post-cycle 1, adopt cycle-by-count re-dosing, shorten venetoclax to 7–14 days, and pre-specify absolute neutrophil count (ANC)/platelet-based holds, with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) support after blast clearance.

Class-wide toxicities—myelosuppression, gastrointestinal events (nausea, diarrhea; mucositis with WEE1/CHK1), and increased infection risk—require proactive management. Antimicrobial prophylaxis, low-threshold cultures, and early G-CSF support post-cytoreduction are essential, particularly with venetoclax/HMA combinations. QT prolongation is rare, but drug–drug interactions (e.g., azole antifungals, antiemetics) necessitate systematic review. For WEE1 and ATR inhibitors, step-up dosing in frail patients and monitoring of electrolytes/renal function mitigate risks, especially with nucleoside analogs.

Actionable Deployment: Focus on high-stress genotypes and post-venetoclax failure. In venetoclax/HMA-refractory or TP53-mutant AML with replication-stress signatures, prioritize short-pulse ATR (e.g., ceralasertib) or WEE1 (e.g., adavosertib) combinations with marrow-sparing venetoclax windows, guided by γH2AX/CHK1-P pharmacodynamics and MRD kinetics (Bataller et al., 2024). In FLT3-or RAS-driven proliferative relapses, couple DDR pulses with kinase inhibitors (e.g., gilteritinib, trametinib) to align fork collapse with pathway suppression. Success hinges on precise timing and intensity, leveraging endogenous replication stress as a therapeutic liability while maintaining patient tolerability for durable remissions. The clinical development of ATR, CHK1, and WEE1 inhibitors is still immature, and balancing their efficacy against profound myelosuppression will be critical before these approaches can move into routine AML care.

3.8 Nuclear export

3.8.1 Rationale and mechanism

Exportin-1 (XPO1/CRM1) is the principal nuclear export receptor for hundreds of leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES)–bearing cargos, including tumour suppressors (p53, FOXO, RB), cell-cycle regulators (p21, p27), and key transcriptional co-factors. Pathologic hyper-export attenuates nuclear checkpoint fidelity and favours prosurvival transcription. In AML, NPM1-mutated blasts are uniquely coupled to XPO1: the NPM1c frameshift creates a strong NES that drives cytoplasmic mislocalisation of NPM1, sustains HOX/MEIS expression, and locks cells in an immature state. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINEs) such as selinexor (first-in-class) and eltanexor (second-generation) bind covalently to Cys528 in XPO1, block cargo docking, and restore nuclear residency of p53/FOXO and NPM1c. In NPM1-mutant models this results in rapid downregulation of HOXA9/MEIS1, lineage-specific transcriptional re-programming, and myeloid differentiation. Because XPO1 blockade also reduces translation of short-lived survival proteins and perturbs stress-adaptation circuits, it synergises mechanistically with BH3 mimetics and hypomethylating agents (HMAs) to convert transcriptional reset into mitochondrial commitment.

3.8.2 Preclinical–clinical bridge

Across NPM1-mutant and select KMT2A-rearranged models, XPO1 inhibition lowers HOX programmes, increases pro-apoptotic BH3 priming, and augments azacitidine–venetoclax cytotoxicity. Early clinical experiences in AML/MDS demonstrate pharmacodynamic on-target activity (nuclear re-accumulation of NPM1c/p53; HOX/MEIS down-titration) and signals of efficacy in biomarker-enriched cohorts, but single-agent cytoreduction has been modest and durability appears combination-dependent. Consequently, XPO1 inhibitors are best conceptualised as transcription-state modulators and sensitisers, not as sole debulking agents.

3.8.3 Safety, scheduling and deliverability

Class-typical adverse events—nausea, anorexia/weight loss, fatigue, hyponatraemia, and cytopenias—are schedule-intensive rather than strictly dose-dependent. Practical measures include pre-emptive antiemetics, salt supplementation for hyponatraemia, and once-weekly or short-pulse dosing aligned to combination partners. When paired with venetoclax/HMAs, marrow preservation hinges on time-limited venetoclax exposure (7–14 days beyond cycle 1), cycle-by-count redosing, and early use of growth-factor support after blast clearance. Eltanexor—with reduced CNS penetration and a differentiated PK profile—may mitigate some constitutional toxicities, but head-to-head AML data are immature.

3.8.4 Biomarkers and implementation

NPM1 mutation is the leading enrichment marker; exploratory composite signatures (HOX/MEIS high; XPO1 pathway activation) may broaden selection. Pharmacodynamic guides—nuclear relocalisation of NPM1c/p53, decrement in HOXA9/MEIS1, and rising maturation markers—should be built into early cycles to confirm target engagement and justify continuation. NPM1 mutant-transcript MRD (RT-qPCR) and multiparameter flow cytometry provide sensitive readouts to tailor maintenance vs. escalation, whereas rising HOX expression or MAPK activation can trigger partner switch (for example, adding a menin or MEK inhibitor in defined contexts).

3.8.5 Actionable implications

In NPM1-mutant AML, XPO1 inhibitors may be most effective in combination with azacitidine and venetoclax. For patients who relapse on venetoclax, short-pulse selinexor or eltanexor could act as a sensitizer, though single-agent efficacy is limited.

3.9 Bone-marrow niche

The bone-marrow niche serves as a critical microenvironment that supports the survival, proliferation, and drug resistance of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) blasts (Figure 3), particularly in subsets with specific genetic aberrations such as NPM1 mutation. Exportin-1 (XPO1/CRM1), a key nuclear export receptor, mediates pathologic crosstalk between AML blasts and the bone-marrow niche in NPM1-mutant AML: the frameshift mutation in NPM1 (NPM1c) generates a strong leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES), driving cytoplasmic mislocalization of NPM1. This aberrant localization sustains the expression of HOX/MEIS transcription factors—key regulators of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal—locking blasts in an immature state and enhancing their adaptation to the bone-marrow niche’s pro-survival signals (Falini et al., 2022).

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of apoptosis- and niche-centered therapeutic architecture in AML. This figure integrates two core therapeutic axes targeting AML pathogenesis—intracellular apoptotic regulation and bone marrow niche/innate immune interaction—and illustrates the corresponding molecular drivers, resistance mechanisms, and targeted therapeutic strategies: 1. Intracellular driver nodes and apoptotic regulation axis. (1) Oncogenic transcriptional scaffold and lineage/chromatin program drivers: Aberrant activation of menin-KMT2A/NPM1 complexes sustains abnormal HOX-MEIS gene expression and disrupted chromatin homeostasis, while IDH1/2 mutations induce epigenetic inertia via 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) accumulation; targeted interventions for these drivers (e.g., Menin inhibitors, IDH inhibitors) rewire pathological transcriptional programs. (2) Mitochondrial apoptosis node: The BCL-2/BCL-XL anti-apoptotic proteins maintain mitochondrial integrity to evade leukemic cell death; the BH3 mimetic venetoclax directly inhibits BCL-2, triggering mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and activating the apoptotic cascade. (3) Resistance bypass mechanism: FLT3 mutation-driven signaling (or MAPK/RAS bypass activation post-FLT3 inhibitor treatment) promotes leukemic cell survival by overriding apoptotic signals; combination strategies (e.g., FLT3 inhibitors + BH3 mimetics) synergistically block both survival signaling and anti-apoptotic defenses, defined as “BH3 therapeutic flow” in the diagram.2. Bone marrow niche/innate immune interaction axis. The CD47-SIRPα “do not eat me” signal axis enables leukemic cells to escape phagocytosis by macrophages in the bone marrow niche. Targeting this axis (e.g., anti-CD47 antibodies) blocks the CD47-SIRPα interaction, restoring macrophage-mediated phagocytic clearance of leukemic cells—this immune-based intervention is labeled as “phagocytosis therapeutic flow” to distinguish it from intracellular apoptotic regulation. Abbreviations: FLT3i, FLT3 inhibitor; BH3, BCL-2 homology 3; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; SIRPα, signal regulatory protein α.

Selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINEs), including selinexor (first-in-class) and eltanexor (second-generation), disrupt this niche-dependent survival by covalently binding to Cys528 in XPO1, blocking cargo docking, and restoring nuclear residency of NPM1c, tumor suppressors (e.g., p53, FOXO), and cell-cycle regulators (e.g., p21, p27) (Bataller et al., 2024). In preclinical NPM1-mutant AML models, XPO1 inhibition induces rapid downregulation of HOXA9/MEIS1, reprograms lineage-specific transcription, and promotes myeloid differentiation—effects that weaken the blast’s niche adaptation (Falini et al., 2022). Clinically, combining SINEs with azacitidine (a hypomethylating agent, HMA) and venetoclax (a BH3 mimetic) further perturbs niche-blast interactions: this triple regimen reduces translation of short-lived survival proteins (dependent on niche-derived growth factors) and disrupts stress-adaptation circuits, converting transcriptional reset into mitochondrial commitment to apoptosis (Glaviano et al., 2025). A 2024 phase I/II trial of selinexor + azacitidine + venetoclax in NPM1-mutant AML reported a 50% complete remission (CR)/CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRh) rate, underscoring the utility of targeting XPO1 to disrupt bone-marrow niche support for AML blasts (Sweet and Cluzeau, 2025).

When combining SINEs with venetoclax/HMAs, careful scheduling and supportive care (e.g., shorter venetoclax windows, early G-CSF support) are needed to avoid prolonged cytopenias while maintaining efficacy (Garcia-Manero et al., 2024b). Eltanexor, with reduced central nervous system (CNS) penetration and a differentiated pharmacokinetic profile, may further mitigate niche-related toxicities (e.g., prolonged cytopenias) compared to selinexor, though head-to-head AML data remain limited (Garcia-Manero et al., 2024b). Biomarkers to guide niche-targeted therapy include NPM1 mutation (primary enrichment marker), HOX/MEIS-high signatures (to identify niche-dependent blasts), and pharmacodynamic readouts (nuclear relocalization of NPM1c/p53, HOXA9/MEIS1 decrement) to confirm niche-blast interaction disruption (Falini et al., 2022).

3.10 Innate immune evasion

Immune evasion is a hallmark of AML pathogenesis, with blasts exploiting multiple mechanisms to suppress anti-tumor immunity—including dysregulation of tumor suppressors and transcriptional programs that govern immune cell activation. XPO1-mediated nuclear export plays a pivotal role in this process: by exporting tumor suppressors (e.g., p53, FOXO) and transcriptional co-factors from the nucleus, XPO1 hyperactivity attenuates nuclear checkpoint fidelity and promotes pro-survival, immune-suppressive transcription (Bataller et al., 2024). For example, cytoplasmic sequestration of p53 (due to XPO1 overactivity) impairs the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that recruit and activate cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, while FOXO mislocalization reduces the transcription of genes involved in antigen presentation (e.g., MHC class I molecules). In NPM1-mutant AML, NPM1c cytoplasmic mislocalization further exacerbates immune evasion by sustaining HOX/MEIS expression—HOX proteins have been shown to repress the expression of immune-stimulatory molecules, creating an immune-suppressive bone-marrow microenvironment (Falini et al., 2022).

XPO1 inhibition reverses these immune-evasive mechanisms by restoring nuclear residency of p53 and FOXO, thereby reactivating immune-stimulatory transcriptional programs. Preclinically, SINEs enhance “pro-apoptotic BH3 priming” in AML blasts, making them more susceptible to immune-mediated killing by cytotoxic lymphocytes (Glaviano et al., 2025). Additionally, XPO1 blockade reduces the translation of short-lived immune-suppressive proteins (e.g., PD-L1) and perturbs stress-adaptation circuits that drive immune checkpoint upregulation—effects that synergize with BH3 mimetics (venetoclax) and HMAs (azacitidine) to enhance anti-tumor immunity (Glaviano et al., 2025). Azacitidine, for instance, induces demethylation of MHC class I and immune-stimulatory gene promoters, while venetoclax triggers immunogenic cell death (ICD) of AML blasts; combining these agents with SINEs amplifies immune recognition and clearance of blasts, addressing the immune-evasive phenotype (Glaviano et al., 2025).

Clinically, early experiences with SINEs in AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) demonstrate on-target pharmacodynamic activity (nuclear re-accumulation of p53, downregulation of HOX/MEIS) that correlates with restored immune function—including increased infiltration of cytotoxic T cells into the bone marrow and reduced PD-L1 expression on blasts (Glaviano et al., 2025). However, single-agent SINEs show modest cytoreduction (CR rates ∼10–15%) due to residual immune evasion, highlighting the need for combination strategies (Glaviano et al., 2025). For venetoclax-experienced patients with persistent HOX/MEIS signatures (and thus ongoing immune suppression), short-pulse selinexor/eltanexor acts as a “sensitizing module” to reverse immune evasion, making blasts responsive to subsequent immune-based therapies (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors) (Bhatnagar et al., 2020). In NPM1/FLT3 co-mutant AML, combining XPO1 inhibitors with FLT3 inhibitors (e.g., gilteritinib) further targets immune evasion: FLT3 inhibition reduces FLT3 ligand-mediated suppression of NK cells, while XPO1 blockade restores p53/FOXO-driven immune activation, creating a synergistic anti-tumor immune response (Daver and Craddock, 2024).

Biomarkers to monitor immune evasion reversal include multiparameter flow cytometry (to assess T cell/NK cell infiltration and activation) and NPM1-mutant transcript minimal residual disease (MRD) via RT-qPCR (to quantify immune-mediated blast clearance) (Falini et al., 2022). Rising HOX expression or MAPK activation—signals of adaptive immune evasion—indicate the need for partner switches (e.g., menin inhibitors to suppress HOX, MEK inhibitors to block MAPK-driven immune checkpoint upregulation) 87. Reversing immune evasion with XPO1 inhibitors may require combination with immune-enhancing therapies. Early biomarkers such as restored p53 activity or reduced PD-L1 could help identify patients most likely to benefit.

4 Clinically meaningful combinations and how to build them

Combination therapy in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) succeeds by aligning orthogonal vulnerabilities with deliverable schedules, maximizing efficacy while minimizing toxicity (Table 3). Five principles guide effective regimens: (i) Orthogonal Pairing: Targeting independent survival axes (e.g., FLT3 inhibition + venetoclax for apoptosis priming, menin inhibition + venetoclax for lineage/HOX reprogramming) raises the genetic barrier to resistance (Kannan et al., 2025). (ii) Context Fidelity: Regimens must be anchored to genotype and phenotype, tailoring combinations to specific molecular drivers (FLT3, IDH, NPM1, KMT2A, TP53) (Daver et al., 2020). (iii) Schedule Optimization: Myelosuppression, the primary dose-limiting constraint, requires staggered pro-apoptotic peaks, time-limited venetoclax windows (28 days in cycle 1, 7–14 days thereafter in responders), and measurable residual disease (MRD)-adapted de-escalation to prioritize marrow recovery (Willekens et al., 2025). (iv) Function Before Form: Ex vivo BH3 profiling and short-term drug-response assays identify BCL-2 versus MCL-1 dependence, predict venetoclax benefit, and guide pivots to CDK9/MCL-1 or MAPK-axis partners (Peng et al., 2024). (v) Resistance Anticipation: Rapid molecular surveillance for FLT3 TKD/gatekeeper alleles, IDH isoform switching, and RAS/MAPK clones enables preemptive switches or additions (Short et al., 2024).

Table 3. Summary of FDA- and EMA-Approved therapeutic agents for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), including clinical trial details, indications, and efficacy outcomes.

4.1 Evidence-weighted exemplars

4.1.1 Venetoclax + azacitidine (standard of care)

In older or unfit AML, this doublet improves complete remission (CR) rates (66.4% vs 28.3%) and overall survival (OS: median 14.7 vs 7.6 months) versus azacitidine alone (DiNardo et al., 2020; Willekens et al., 2025). Deliver with tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) prophylaxis, a 28-day venetoclax window in cycle 1, then 7–14 days in deep responders, cycle-by-count re-dosing, and azole-aware CYP3A adjustments. Use flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing (NGS)-MRD to guide continuation versus maintenance de-intensification (Medina et al., 2020).

4.1.2 FLT3 inhibitor + venetoclax ± azacitidine (FLT3-mutant AML)

This backbone achieves deep molecular responses in FLT3-mutant AML, with a 2024 trial reporting 65% CR/CRh rates with gilteritinib + venetoclax + azacitidine (Perl et al., 2019). Front-load FLT3 inhibitor (e.g., gilteritinib, quizartinib) and HMA, maintain full venetoclax in cycle 1, then shorten to 7–14 days. For RAS/MAPK activation, add short-pulse MEK/ERK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib) (Davis et al., 2025); for D835/F691L mutations, switch conformation class (type-I↔type-II) rather than escalating dose (Yamatani et al., 2021).

4.1.3 Ivosidenib + azacitidine (IDH1-mutant, newly diagnosed)

This chemo-sparing doublet confers event-free survival (EFS; hazard ratio 0.33) and OS benefits in unfit IDH1-mutant AML (Montesinos et al., 2022). Implement differentiation syndrome (DS) protocols (dexamethasone 10 mg every 12 h, hydroxyurea cytoreduction, drug holds for grade ≥3 DS) and QT monitoring. Add venetoclax in trials when BCL-2 dependence is confirmed by BH3 profiling, with vigilant cytopenia management (Vom Stein and Frenzel, 2025).

4.1.4 Menin inhibitor + venetoclax/HMA (NPM1-mutant or KMT2A-rearranged AML)

Menin inhibitors (e.g., revumenib, ziftomenib) reset HOX/MEIS biology and re-sensitize mitochondria to BCL-2 inhibition, with HMAs stabilizing the reprogrammed state. A 2024 phase II trial reported 55% CR/CRh with ziftomenib + venetoclax + azacitidine in NPM1-mutant AML (Crews et al., 2023). Monitor for DS, shorten venetoclax post-cycle 1, and track NPM1-mutant or KMT2A-fusion MRD alongside HOX/MEIS pharmacodynamics. In NPM1/FLT3 co-mutant disease, combine menin + FLT3 inhibitors ± venetoclax (Daver et al., 2024).

4.1.5 HMA + STING agonist ± venetoclax (TP53-mutant AML)

STING agonists re-prime apoptosis and enhance antigen presentation in TP53-mutant AML, where cytotoxic and kinase responses are poor. A 2023 study showed synergy with venetoclax in preclinical models (Zhang et al., 2023). Use short-pulse schedules to limit cytokine toxicity, integrate interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) pharmacodynamics, and add venetoclax when BH3 assays confirm mitochondrial benefit.

4.1.6 WEE1 (adavosertib) or ATR (ceralasertib) + HMA/venetoclax (post-venetoclax failure)

Short DDR pulses (5–7 days) re-sensitize by collapsing S-phase checkpoints and downregulating survival transcripts like MCL1. A 2025 trial reported 40% CR in TP53-mutant, venetoclax-refractory AML with ceralasertib + venetoclax + azacitidine (Daver et al., 2025). Sequence DDR first to amplify replication stress, then overlay venetoclax, using cycle-by-count re-dosing and ANC/platelet-based holds (Maiti et al., 2021).

Across combinations, embed: (i) azole-aware venetoclax dosing to manage CYP3A interactions; (ii) TLS ramp-up in cycle 1; (iii) G-CSF support post-blast clearance; (iv) MRD-anchored decisions (de-escalate on durable negativity, escalate/switch on plateau or rebound); and (v) rapid molecular surveillance for FLT3 TKD/gatekeeper alleles, IDH isoform shifts, and RAS clones via NGS and ctDNA. These scheduling and monitoring disciplines are as critical as the molecular components, ensuring deliverability and resistance preemption.

While this section provides a comprehensive overview of combination principles and exemplars, it presents all regimens with uniform emphasis without critically assessing the relative strength of evidence supporting each, and fails to address key uncertainties such as the comparative efficacy across different genetic contexts, long-term safety of novel combinations, or the limitations of applying early-phase trial data to broader clinical practice.

5 Regulatory timeline

The past decade has delivered an unprecedented cadence of small-molecule approvals that have reshaped AML care across frontline and relapsed/refractory settings (Figure 4). Milestones have clustered around four mechanistic pillars—oncokinase inhibition (FLT3), oncometabolic differentiation (IDH1/2), mitochondrial apoptosis priming (BCL-2), and niche/lineage modulation (SMO and, more recently, menin)—with labels increasingly codifying combination use (e.g., with hypomethylating agents) and, in some cases, continuation/maintenance concepts.

2017 — Enasidenib (IDH2) for R/R AML. First approval to pharmacologically reverse an epigenetic differentiation block, establishing (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate as a druggable liability and validating differentiation-led response kinetics.

2017 — Midostaurin (FLT3) added to intensive chemotherapy (frontline). RATIFY demonstrated an overall-survival benefit across ITD and TKD subsets, inaugurating genotype-directed kinase inhibition in de novo disease.

2018 — Gilteritinib (FLT3) for R/R FLT3-mutant AML. ADMIRAL set a new single-agent standard at relapse, with conformation-flexible type-I inhibition enabling post-tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor(TKI) salvage.

2018 → 2020 — Venetoclax + HMA/LDAC for newly diagnosed, unfit AML. Accelerated approval (2018) converted to regular approval (2020; VIALE-A), moving mitochondrial priming into the frontline for older/unfit patients and establishing the backbone for modern doublets/triplets.

2018 — Glasdegib + LDAC (frontline, unfit). First approval aimed at hedgehog/LSC biology; positioned as a low-intensity alternative where venetoclax-based regimens are unsuitable.

2022 — Ivosidenib + azacitidine (frontline IDH1-mutant). AGILE delivered event-free and overall-survival gains with a chemo-sparing doublet, formalising targeted-plus-epigenetic induction for a molecular subset.

2023 — Quizartinib + intensive therapy (frontline FLT3-ITD). QuANTUM-First showed an overall-survival advantage with type-II inhibition integrated across induction, consolidation and continuation, introducing a pathway-maintenance paradigm.

2024 — Revumenib (menin) for KMT2A-rearranged acute leukemia (Zeidner et al., 2025a). First-in-class approval for transcriptional lineage switching, paving the way for broader deployment (including NPM1-mutated AML) and combination-anchored strategies.

Figure 4. Timeline of Targeted Therapy Approvals and Therapeutic Strategies in AML (2017–2024). This timeline visualizes the evolution of targeted therapies for AML over an 8-year period (2017–2024), with a focus on three interconnected components: (1) Key regulatory approvals of targeted agents, including those directed against driver molecular alterations such as FLT3, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), and lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A). (2) Current clinical challenges in the field, such as optimizing MRD-guided treatment escalation/de-escalation and overcoming primary/acquired resistance to existing targeted therapies. (3) Emerging future directions, which encompass the development of novel agents targeting the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway and the integration of ctDNA-based liquid biopsies into treatment monitoring workflows. This visualization contextualizes the progress of AML targeted therapy, while highlighting unmet needs and potential avenues for advancing patient care.

6 Where drug development should go next

6.1 A next-generation BH3 toolkit

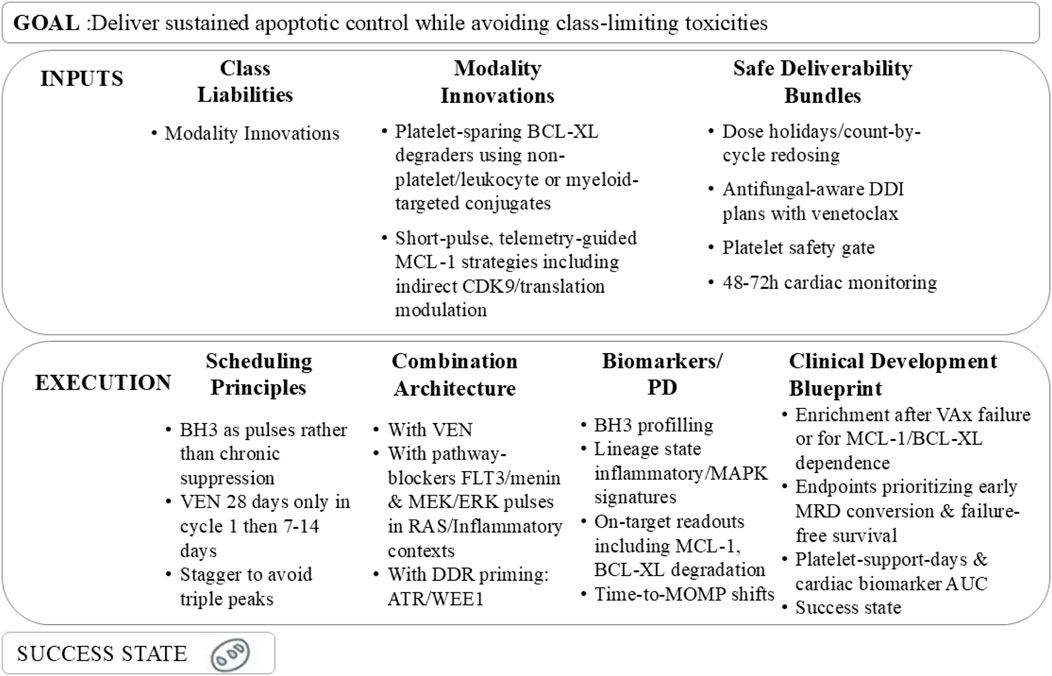

A next-generation BH3 toolkit aims to deliver durable apoptotic control in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) while mitigating the class-defining liabilities of thrombocytopenia from BCL-XL antagonism and cardiotoxicity from sustained MCL-1 suppression (Table 4). Venetoclax has validated mitochondrial priming as a central vulnerability, achieving a 66.4% complete remission (CR) rate in older/unfit AML when combined with azacitidine. However, relapse often coincides with anti-apoptotic re-balancing, marked by a shift from BCL-2 to MCL-1 and/or BCL-XL dependence, amplified by inflammatory and MAPK cues (Kannan et al., 2025). Direct targeting of MCL-1 or BCL-XL can restore the apoptotic threshold, but first-generation agents revealed safety ceilings: BCL-XL inhibitors (e.g., navitoclax) cause dose-limiting thrombocytopenia, and MCL-1 inhibitors show cardiac toxicity with continuous dosing (Roberts et al., 2021). The design brief prioritizes modular, schedule-friendly agents that integrate with venetoclax-based or chemo-sparing regimens without exhausting marrow reserve.

Three modality innovations define the forward path:

1. Platelet-Sparing BCL-XL Strategies: Ligase-selective degraders, such as VHL-recruiting PROTACs, deplete BCL-XL in blasts while sparing megakaryocytes by targeting E3 ligases under-represented in platelets. Alternatively, antibody–drug or ligand-directed conjugates (ADCs) targeting myeloid antigens (e.g., CD33, CD123) limit systemic BCL-XL exposure. Both formats require rapid off-kinetics and interruption-tolerant pharmacology for brief pulses aligned with venetoclax windows. A 2024 preclinical study demonstrated 80% BCL-XL degradation in AML blasts with minimal platelet toxicity using a VHL-PROTAC (Wei et al., 2024). A phase I trial of a CD33-directed BCL-XL ADC reported a 30% ORR in venetoclax-refractory AML with reduced thrombocytopenia (Davids et al., 2025).

2. Context-Specific MCL-1 Inhibition: Short-pulse MCL-1 inhibitors (hours to 3–5 days) achieve transient target occupancy to collapse MCL-1 reserves without chronic suppression, minimizing cardiotoxicity. Co-development of a cardiac telemetry bundle (high-sensitivity troponin, NT-proBNP, strain echocardiography), step-up dosing, and pharmacodynamic (PD)-guided holds opens a therapeutic window. Indirect MCL-1 suppression via CDK9 inhibitors (e.g., alvocidib) or translation modulators offers a tunable alternative, with a 2025 study showing synergy with venetoclax in MCL-1-dependent AML (Alvarado-Valero et al., 2025).

3. Dual-Target, Cooperativity-Tuned Designs: Bitopic binders or dual degraders weakly engaging BCL-XL and MCL-1 prevent compensatory switching without maximal inhibition of either protein. Medicinal chemistry should prioritize partial-inhibition profiles controlled by schedule to retain BH3 cooperativity with venetoclax while minimizing toxicity. Preclinical data from 2024 showed a dual BCL-XL/MCL-1 degrader achieving 50% tumor reduction in AML xenografts with no cardiac or platelet toxicity (Fiskus et al., 2025).

Safe deliverability of BH3-targeted therapies in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) necessitates upfront engineering of risk-mitigation strategies, including standardizing dose holiday protocols and count-by-cycle re-dosing schedules to ensure consistency in drug exposure; embedding antifungal-aware drug-drug interaction plans specifically tailored for venetoclax-based combinations, given the potential for overlapping toxicities and altered pharmacokinetics; establishing clear platelet safety gates for BCL-XL-targeting components (e.g., a threshold of ≥50 × 109/L paired with predefined transfusion algorithms) to minimize hemorrhagic risk; and implementing an MCL-1 inhibitor-specific cardio-protection bundle, which includes telemetry monitoring every 48–72 h during early treatment cycles, automatic dose holds for any troponin elevation, and early consultation with cardiology teams to address emerging cardiovascular signals. Beyond safety, the development of such therapies must be function-anchored, with predictive biomarkers guiding patient selection and treatment optimization: these biomarkers include BH3 profiling to differentiate between BCL-2 versus MCL-1/BCL-XL dependency, assessment of lineage state (e.g., monocytic shift) to identify subsets likely to respond to lineage-reprogramming combinations, and detection of inflammatory/MAPK signatures to stratify patients for MEK/ERK inhibitor integration (Fonseca et al., 2025). On-target efficacy readouts—such as declines in MCL-1 transcript and protein levels, BCL-XL degradation indices, and ex vivo measurements of mitochondrial depolarization kinetics (e.g., time-to-MOMP)—should be paired with clinical markers [including flow cytometry/next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment, platelet recovery kinetics, and cardiac biomarkers] to inform decisions on dose adjustment, treatment de-escalation, or switching of combination partners (Diepstraten et al., 2022).

Notably, scheduling of BH3-targeted modules is equally critical to their molecular design, with an emphasis on using these agents as “sensitizing pulses” to balance efficacy and toxicity: in cycle 1, a full 28-day course of venetoclax should be retained to establish initial therapeutic pressure, while in responders, subsequent cycles can be shortened to 7–14 days to reduce cumulative exposure; BCL-XL or MCL-1 inhibitor pulses should be aligned to days 1–3 (or 1–5) of each cycle to deliver focused mitochondrial pressure, followed by extended intervals to allow for hematologic recovery; triple concurrent toxicity peaks (e.g., from co-administration of venetoclax, an MCL-1 inhibitor, and intensive chemotherapy) must be avoided by staggering drug administration within cycles; and upon achievement of durable MRD negativity, treatment should transition to MRD-adapted maintenance, with BH3 modules withdrawn while pathway blockers (e.g., FLT3, IDH, or menin inhibitors) are continued to sustain remission. The architecture of combination regimens should prioritize mechanism orthogonality to maximize synergy and minimize overlapping toxicities: in venetoclax-experienced patients, low-exposure BCL-XL degraders or short-pulse MCL-1 inhibitors should be paired with venetoclax, guided by platelet- and cardio-first dose modification trees to manage organ-specific risks; for patients with signal-driven or lineage-dependent disease, BH3 pulses should be combined with FLT3 or menin inhibitors to leverage signaling inhibition or lineage reprogramming, with the addition of MEK/ERK inhibitor pulses (e.g., trametinib) in inflammatory or RAS-mutant contexts to suppress stress-induced MCL-1/BCL-XL upregulation; and integration with DNA damage response (DDR) modules (e.g., ATR or WEE1 inhibitors) can downregulate MCL-1 and amplify replication stress, provided that administration is timed to avoid overlapping myelosuppressive nadirs (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Framework for achieving sustained apoptotic control in AML while mitigating class-limiting toxicities, including key inputs, execution strategies, and a defined success state.

The clinical development blueprint for BH3-centric therapies should further refine patient enrichment in early-phase trials, focusing on subsets with BH3-defined MCL-1/BCL-XL dependency, monocytic phenotype, or prior venetoclax failure—populations most likely to benefit from targeted BH3 pathway manipulation—while incorporating in-cycle pharmacodynamic (PD) readouts (e.g., time-to-MOMP) to confirm successful mitochondrial re-priming, a key mechanistic endpoint of BH3-targeted therapy. Trial endpoints should prioritize measures of deep and durable response alongside traditional efficacy metrics: in addition to overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DoR), early MRD conversion (a surrogate for long-term survival), failure-free survival (capturing disease progression, death, and toxicity-related treatment discontinuation), platelet support days (a direct measure of myelosuppressive burden), and cardiac biomarker area-under-the-curve (a dynamic assessment of cardiovascular risk) should be central to evaluation. Pre-specified stopping rules are essential to guard against mechanism-free exposure and unnecessary toxicity, including discontinuation for recurrent troponin elevation, persistent grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia despite dose holds, or lack of BH3 shift (indicating failed target engagement) by cycle 2. Comparator arms should include clinically relevant standards of care, such as venetoclax plus hypomethylating agents (HMA) alone or venetoclax-HMA combined with genotype-matched pathway inhibitors (e.g., FLT3 or IDH inhibitors), to contextualize the added value of BH3-centric combinations. Ultimately, successful translation of BH3-targeted therapy will be defined by four key outcomes: (i) restoration of mitochondrial cooperativity in patients with post-venetoclax failure, reversing apoptotic resistance; (ii) minimization of platelet and cardiac toxicity through optimized drug chemistry and scheduling; (iii) enablement of time-limited, MRD-tethered treatment, reducing the burden of chronic therapy; and (iv) seamless integration with FLT3, IDH, and menin inhibitors, transforming BH3-centric therapy into a precision-tuned, relapse-resilient module applicable across AML subtypes.

6.2 Clonal-pressure-aware trials

Modern AML trials should prioritize the biology of therapeutic selection over morphology-driven endpoints, recognizing that actionable resistance—emergent RAS/MAPK clones, secondary FLT3 TKD/gatekeeper alleles (e.g., D835, F691L), and IDH isoform switching—arises before overt relapse and is detectable at MRD or pre-MRD fluctuations (Short et al., 2024). Protocols must embed molecular adaptation endpoints and pre-specified treatment switches triggered by MRD conversion or predefined molecular thresholds, rather than waiting for morphologic failure. In FLT3-mutated AML, this involves codifying type-I ↔ type-II tyrosine kinase inhibitor rotation upon detection of TKD/gatekeeper variants; in IDH-mutant disease, sequential or dual-isoform blockade at evidence of IDH1↔IDH2 switching (Lyu et al., 2020); and under venetoclax pressure, partner substitution (e.g., CDK9 or MAPK inhibitors) when BH3 profiling indicates a shift from BCL-2 to MCL-1/BCL-XL dependence (Kannan et al., 2025).

6.2.1 Operationalizing high-cadence monitoring

Operationalizing this approach requires high-cadence, low-latency monitoring embedded in trial schedules:

1. NGS and Digital PCR: Perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels and digital PCR for FLT3, IDH, and RAS every 4–6 weeks during induction and the first three consolidation cycles, then every 8–12 weeks through year one, with ≤7-day turnaround times (Short et al., 2024).

2. MRD Surveillance: Use multiparameter flow cytometry and mutation-specific assays (e.g., NPM1 RT-qPCR) with action windows (e.g., switch within 7–10 days of a confirmatory molecular call) to guide therapy adaptation (Gilbert et al., 2024).

3. Functional Readouts: Schedule BH3 profiling and ex vivo drug sensitivity testing alongside molecular assays to distinguish genetic noise from actionable shifts in apoptotic dependency, as shown in a 2023 trial predicting venetoclax response.

6.2.2 Statistical and design considerations