- 1Biomedical focus, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

- 2Knoebel Institute of Healthy Aging, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

- 3Center for Advanced Biosensing Engineering (CABE), Deparment of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

Amino acid metabolism is an important vulnerability in cancer. Established strategies such as arginine depletion, glutaminase inhibition, tryptophan-kynurenine modulation, and methionine restriction have shown that these pathways can be targeted in patients. At the same time, clinical trials reveal two consistent challenges: tumors can adapt by redirecting their metabolism, and reliable biomarkers are needed to identify patients who are most likely to benefit. Recent studies point to additional amino acids with translational potential. In pancreatic cancer, histidine and isoleucine supplementation has been shown in preclinical models to be selectively cytotoxic to tumor cells while sparing normal counterparts. In glioblastoma, threonine codon-biased protein synthesis programs that support growth; in other contexts, lysine breakdown suppresses interferon signaling through changes in chromatin structure; and alanine released from stromal cells sustains mitochondrial metabolism and therapy resistance. These dependencies are closely tied to amino acid transporters, which act as both nutrient entry points and measurable biomarkers. In this review, we summarize current evidence on histidine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine, and alanine as emerging metabolic targets, and discuss opportunities and challenges for clinical translation, with emphasis on transporter biology, biomarker development, and therapeutic combinations.

1 Introduction

Amino acids play a central role in cancer metabolism, serving as building blocks for protein synthesis and regulators of signaling, redox balance, and immune function (Liu et al., 2024). They are often classified as essential, non-essential, or conditionally essential, and further grouped by structural or metabolic features such as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs: leucine, isoleucine, valine), aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine, tyrosine), and sulfur-containing amino acids (methionine, cysteine). These categories are associated with distinct biological roles in cancer research. For example, BCAAs activate mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), a growth pathway that senses nutrient availability (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). Serine, glycine, and methionine feed one-carbon (1C) metabolism, which provides nucleotides for DNA synthesis and supports epigenetic regulation (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017), while arginine and tryptophan regulate immune responses via T-cell activity and kynurenine–aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling (Carpentier et al., 2024; Ghorani et al., 2023).

Disruptions in amino acid pathways are a hallmark of cancer. Cancer cells reprogram amino acid uptake and utilization to sustain biomass accumulation, maintain antioxidant defenses, and promote growth signaling (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). These adaptations create differences in tumor and normal tissues that can be therapeutically exploited. Clinical studies have already established proof-of-concept. For example, arginine depletion has shown activity in tumors deficient in argininosuccinate synthase 1 (ASS1) (Chan et al., 2021; Chan et al., 2022; Szlosarek et al., 2021), the enzyme that enables cells to synthesize arginine de novo. Glutaminase inhibitors, which block the enzyme responsible for converting glutamine into glutamate and feeding the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, have been evaluated in glutamine-dependent cancers, both as single drug therapy and in rational drug combinations (Patel et al., 2024; Wicker et al., 2021; DiNardo et al., 2024). Similarly, inhibition of tryptophan catabolism through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), enzymes that degrade tryptophan to kynurenine, has been explored to restore antitumor immunity (Wu et al., 2023; Zakharia et al., 2021). These studies establish the feasibility of targeting amino acid metabolism in patients and demonstrate two recurring challenges: tumors can rewire their metabolism in ways that allow them to escape treatment, and the lack of reliable biomarkers makes it difficult to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from treatment (Akinlalu et al., 2025; Balamurugan et al., 2025; Rasuleva et al., 2023; Rasuleva et al., 2021). Recent advances have begun to address these limitations, with ASS1 loss used as a biomarker for arginine deprivation (Carpentier et al., 2024), kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratios to monitor IDO/TDO inhibition (Wu et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2022), and circulating metabolites or amino acid-based positron emission tomography (PET) tracers to confirm drug activity (Galldiks et al., 2023). These developments represent important steps toward more precise, biomarker-guided use of amino acid therapies.

In parallel, new amino acid targets have come into focus. In pancreatic cancer, histidine and isoleucine supplementation are selectively cytotoxic to cancer cells while sparing non-malignant counterparts (Akinlalu et al., 2024). In glioblastoma (GBM), threonine drives tumor growth by fueling codon-biased protein synthesis through transfer RNA (tRNA) modifications mediated by the enzyme YRDC (Wu et al., 2024). Lysine catabolism promotes immune evasion by altering histone modifications (crotonylation) that suppress interferon signaling (Yuan et al., 2023). Alanine released by stromal fibroblasts fuels mitochondrial metabolism in cancer cells, enabling survival and resistance to therapy (Zhu et al., 2023; Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022).

Importantly, these emerging amino acid targets are linked to their associated transporters that act as nutrient gateways and functional biomarkers. The L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; gene name SLC7A5) mediates uptake of histidine, isoleucine, and threonine (Bo et al., 2021). The cationic amino acid transporter 1 (CAT1; gene name SLC7A1) transports lysine and contributes to immune regulation (You et al., 2022). The sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2; gene name SLC38A2) facilitates the uptake of alanine (Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022). Advances in transporter inhibitors (Bo et al., 2021; Lyu et al., 2023), metabolic imaging using amino acid PET tracers (Galldiks et al., 2023; Jakobsen et al., 2023), and studies linking transporter activity to immune regulation (Bo et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2023) underscore their central role in clinical translation.

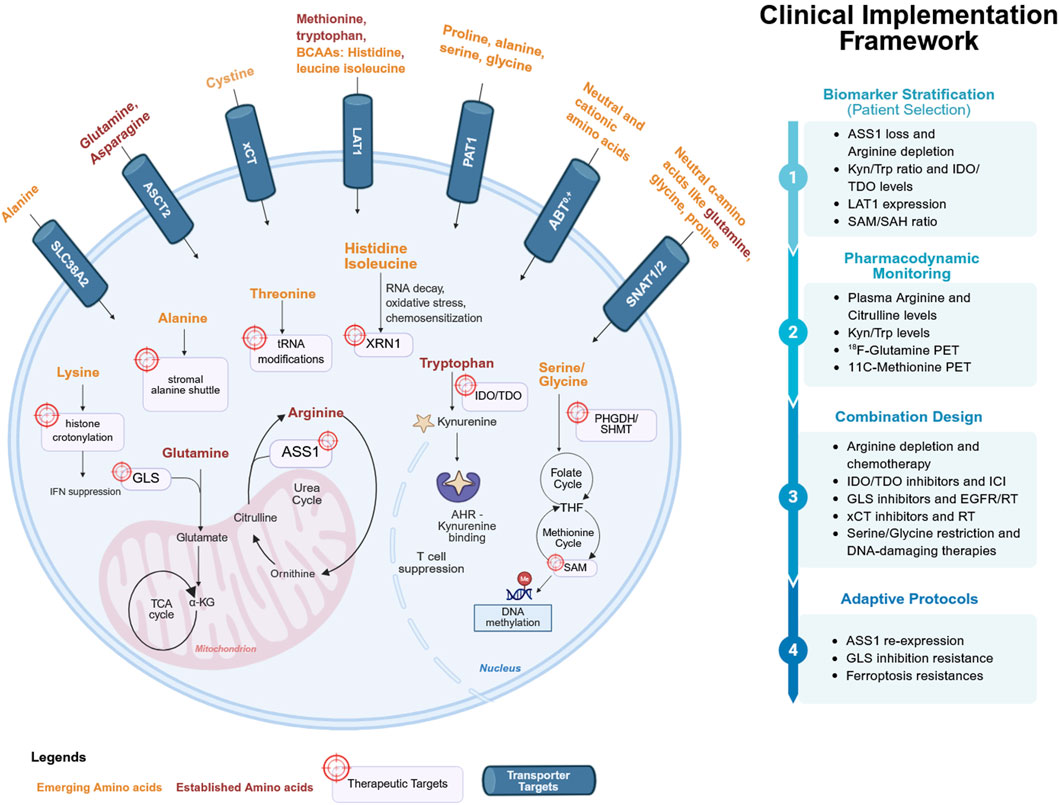

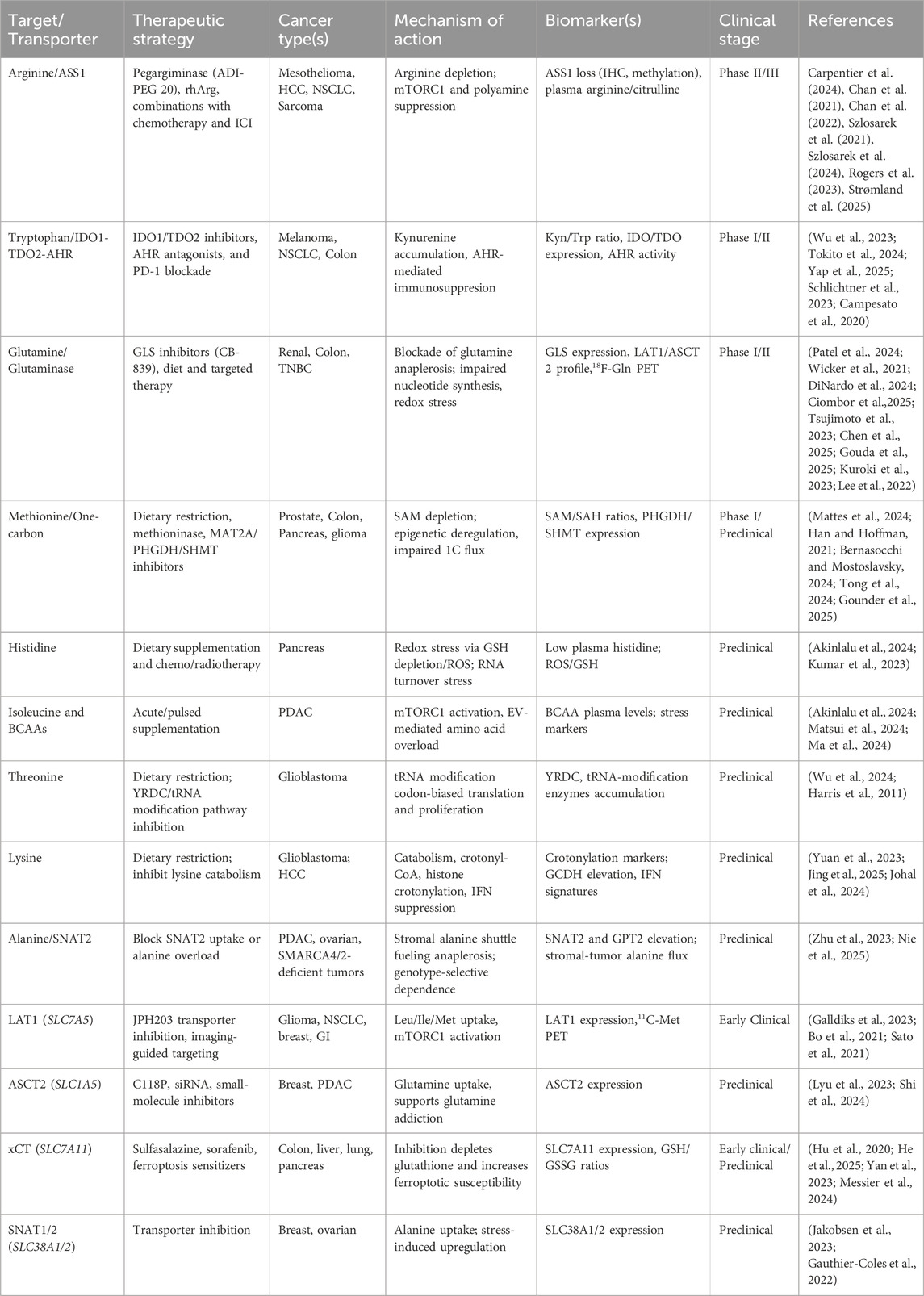

Here, we focus on histidine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine, and alanine as emerging metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer. We emphasize their mechanism, associated transporters, and translational relevance. Drawing on lessons from established amino acid interventions, we outline the opportunities and challenges that will shape the clinical development of these emerging strategies (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Amino acid metabolism and transporters as therapeutic targets in cancer. The cellular pathway illustrates the tumor cell with established dependencies (arginine, glutamine, tryptophan, methionine, asparagine; red) and emerging amino acids (histidine, proline, serine–glycine, aspartate, branched-chain amino acids, threonine, lysine, alanine; orange). Transporters (LAT1, ASCT2, xCT, SLC6A14, SNAT1/2, PAT1; blue) are localized at the plasma membrane. Arrows represent nutrient influx and metabolic pathways, with icons denoting therapeutic interventions (enzyme depletion, pharmacologic inhibitors, dietary restriction, transporter blockade). The clinical implementation framework emphasizes biomarker stratification, pharmacodynamic monitoring, combination design, and adaptive protocols, reflecting how amino acid biology is translated into precision oncology. Figure was created in Biorender. Akinlalu, A. (2025).

Table 1. Established and emerging amino acid dependencies and transporter targets in cancer. The table summarizes mechanisms, transporters, biomarkers, strategies, and evidence tiers for the four established pathways (arginine, glutamine, tryptophan, methionine) and five emerging amino acid cancer therapy, histidine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine and alanine. Transporters central to these targets are shown as both therapeutic entry points and functional biomarkers.

2 Emerging amino acids in cancer therapy

2.1 Histidine

Histidine is an essential amino acid with unique chemical properties. Its imidazole side chain can buffer protons and bind metals, giving histidine a central role in pH balance and metal-dependent enzymatic reactions (Kessler and Raja, 2023). Historically, histidine has not been considered a major driver of cancer metabolism. However, recent work in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has highlighted histidine as a potential therapeutic target.

Our recent study (Akinlalu et al., 2024) demonstrated that histidine combined with isoleucine induces selective cytotoxicity in PDAC. Across in vitro cell culture models and in vivo nude mice xenografts, supplementation with these two amino acids reduced PDAC cell viability while sparing non-malignant counterparts. This selectivity suggests an intrinsic sensitivity to histidine-isoleucine overload, likely linked to altered amino acid handling by tumor cells. The study also pointed to the mRNA exonuclease XRN1 as a possible mechanism: when histidine and isoleucine accumulated, RNA processing was perturbed, adding to cellular stress. Rather than starving tumors of nutrients, this approach overloads them with amino acids they cannot manage, leading to metabolic crisis and cell death.

A complementary study (Kumar et al., 2023) independently showed that histidine supplementation disrupts tumor metabolic balance through a different mechanism. In PDAC models, histidine overload depleted amino acids required for glutathione synthesis, leading to loss of redox homeostasis, accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, and oxidative stress. This sensitized tumors to gemcitabine; exogenous glutathione rescued the effect, confirming the oxidant-antioxidant mechanism. These data suggest two converging mechanisms in PDAC: interference with RNA processing when histidine is paired with isoleucine, and induction of oxidative stress when histidine is used alone. Both selectively stress PDAC cells over normal tissues. While these preclinical findings are compelling, their current limitation lies in model specificity, as most evidence arises from xenograft and cell-line systems. Independent confirmation in patient-derived models and pharmacokinetic studies will be necessary to determine whether histidine modulation is feasible and safe in clinical settings.

Translationally, histidine could be explored as an adjuvant to chemotherapy, as a co-supplement with isoleucine to induce direct cytotoxicity, or in combination with therapies that generate oxidative stress. Recent studies show that PDAC tumors exhibit abnormal histidine uptake and catabolism mediated by histidine ammonia-lyase (HAL), which may contribute to reduced circulating histidine levels and increased oxidative stress (Kumar et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2025; McDonnell et al., 2025). Although stromal barriers in PDAC may limit direct correspondence between plasma and intratumoral metabolites, these observations suggest that HAL expression or activity within the tumor, and possibly systemic histidine availability, may serve as exploratory biomarkers for identifying patients most likely to benefit from histidine-based interventions.

2.2 Isoleucine

Isoleucine is one of the BCAAs, along with leucine and valine. BCAAs support protein synthesis, activate mTORC1, and influence immune function (Dimou et al., 2022). In PDAC cells, proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles (EVs) suggests that tumor cells actively dispose of isoleucine and histidine, consistent with intracellular accumulation being stressful (Akinlalu et al., 2024). Re-supplementation of isoleucine, alone or with histidine, overwhelmed PDAC cells and triggered necrotic death, while non-malignant cells tolerated supplementation (Akinlalu et al., 2024).

Clinically, isoleucine supplementation may be feasible because BCAA-enriched nutrition is used in perioperative and supportive care for cancer patients. Meta-analyses and randomized trials in gastrointestinal cancers report improved nitrogen balance, fewer infections, and better postoperative recovery with BCAAs (Matsui et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024). This safety profile suggests that controlled isoleucine supplementation could be integrated into therapeutic regimens. However, dosing will require careful monitoring to avoid systemic imbalance. While short pulses of high isoleucine may selectively stress tumors, prolonged elevation of circulating BCAAs could increase the risk of side effects, such as insulin resistance or neurological complications (Shah et al., 2024; De Simone et al., 2013).

2.3 Threonine

Threonine is essential for protein synthesis and one-carbon metabolism (Tang et al., 2021). In GBM, one of the most aggressive brain tumors, threonine plays a distinct role in translational control, growth and survival (Wu et al., 2024). Wu et al. (2024) demonstrated that GBM cells accumulate unusually high levels of threonine, which fuels a specific tRNA modification (Wu et al., 2024). The enzyme YRDC (YrdC domain–containing protein) uses threonine to generate N6-threonylcarbamoyl adenosine (t6A), a modification found on tRNAs that decode ANN codons (Perrochia et al., 2013; Harris et al., 2011). This modification skews protein translation toward mitosis-related and proliferative proteins, giving GBM cells a growth advantage. When threonine availability was reduced or YRDC was inhibited, GBM cells showed impaired t6A modification, reduced protein synthesis, and suppressed proliferation. In mouse models, dietary threonine restriction significantly slowed tumor growth, validating threonine as a nutrient that sustains GBM progression (Wu et al., 2024).

For clinical translation, two approaches may be explored. First, dietary modulation, where controlled threonine restriction could selectively stress tumors with high translational demand while sparing normal tissues. Second, pharmacological inhibition of YRDC or related enzymes in the tRNA modification pathway. Such drugs could directly impair the codon-biased translation mechanism that GBM depends on. Although this modification has been observed in a subset of GBM models, potential biomarkers may include YRDC enzymatic activity, high t6A modification levels in tumor RNA, or metabolic features of threonine accumulation. Because these findings are still limited, larger patient studies will be needed to validate these biomarkers and to determine which tumors are most likely to respond to threonine-targeted therapy. Moreover, while threonine availability has been mechanistically linked to YRDC-dependent translation and tumor growth, this evidence comes from GBM models and tumor subtypes. Whether similar vulnerabilities occur across other tumor types or in patients remains uncertain, demonstrating the need for broader validation and biomarker-guided trial designs.

2.4 Lysine

Lysine is an essential amino acid that serves as both a protein building block and a site for multiple post-translational modifications, including acetylation, ubiquitination, and methylation (Wang and Cole, 2020). In GBM, excess lysine breakdown produces crotonyl-CoA, which drives histone crotonylation and suppresses type I interferon signaling (Yuan et al., 2023). This epigenetic silencing weakens immune surveillance by reducing cytotoxic T cell infiltration into tumors. Limiting lysine availability, through dietary restriction or inhibition of catabolic enzymes, lowers crotonyl-CoA levels, restores interferon pathways, and enhances the response to immunotherapy. These findings place lysine metabolism at the center of a metabolic–epigenetic control that tumors exploit to hide from the immune system.

Also, lysine modulation can act in multiple directions depending on tumor type and context. In another GBM study, restricting lysine or using lysine mimics that compete with its metabolic functions enhanced the efficacy of standard chemotherapy, demonstrating the value of nutrient limitation approaches (Jing et al., 2025). Conversely, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), lysine transporter-mediated uptake improved the effects of targeted therapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI), indicating that in some tumors, additional lysine may tip the balance toward improved immune activity (Chang et al., 2025). Meanwhile, systemic studies in mice have shown that lysine restriction is physiologically tolerable and can reduce the buildup of harmful lysine catabolites, further supporting the safety of metabolic modulation (Johal et al., 2024).

These results illustrate that lysine-based therapies cannot be viewed through a single lens of “restriction” or “supplementation”. Instead, lysine represents a flexible metabolite whose impact depends on the interplay between tumor metabolism, the immune microenvironment, and therapy context. Other lysine-derived modifications, including succinylation and lactylation, are gaining attention as regulators of gene expression and immune signaling, pointing to additional therapeutic targets in lysine metabolism.

For clinical translation, lysine restriction may be advantageous in tumors that exploit catabolism to evade immunity, while supplementation could enhance therapy in settings where immune cells compete with tumors for lysine. Future clinical translation will require careful patient selection, biomarker development, and context-specific strategies that account for this duality.

2.5 Alanine

Alanine, a non-essential amino acid, is increasingly recognized as a fuel in the metabolic cooperation between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Beyond its traditional role in the glucose-alanine cycle between muscle and liver, alanine has been shown to act as a stromal-derived nutrient that sustains tumor mitochondrial metabolism (Parker et al., 2020). In PDAC, pancreatic stellate cells release alanine into the tumor microenvironment, which is subsequently imported by cancer cells and converted to pyruvate (Be et al., 2019). Pyruvate replenishes the TCA cycle through anaplerosis, the process of refilling depleted metabolic intermediates. This exchange allows PDAC cells to preserve oxidative phosphorylation and biosynthetic activity under nutrient stress, demonstrating alanine as a central metabolite in stromal-tumor metabolic crosstalk.

Alanine dependence has also been observed in other cancers with defined genetic backgrounds. In ARID1A-mutant ovarian cancers, where loss of the ARID1A chromatin-remodeling gene rewires metabolic programs, tumor cells show heightened reliance on alanine uptake (Nie et al., 2025). Blocking this uptake impaired tumor growth in preclinical models, revealing a genotype-selective vulnerability. Similarly, in SMARCA4/2-deficient tumors, which lack components of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, exogenous alanine overload demonstrated cytotoxicity (Zhu et al., 2023). Supplementation with alanine disrupted metabolic balance and induced cell death in cell cultures and xenograft models (Zhu et al., 2023). These findings suggest that the role of alanine in cancer is not uniform but shaped by tumor genotype, with certain mutations conferring heightened susceptibility. A notable strength of these studies is the integration of metabolic tracing and co-culture systems, which reveal real-time nutrient exchange between stromal and cancer cells. However, translating these observations remains challenging, as stromal heterogeneity and tissue architecture may alter alanine dynamics in vivo.

Clinically, targeting alanine metabolism presents dual opportunities. One approach is to inhibit alanine uptake by blocking sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2; SLC38A2), which mediates alanine import. Early studies indicate that pharmacological inhibition of SNAT2 suppresses tumor growth and can synergize with inhibitors of glucose metabolism (Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022). Alternatively, in specific genetic contexts such as SMARCA4/2 deficiency, alanine supplementation itself may be leveraged to overwhelm tumor metabolic capacity, a strategy that contrasts with nutrient-depletion approaches.

3 Amino acid transporters as targets and functional biomarkers

3.1 LAT1 (SLC7A5)

L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) mediates the uptake of large neutral amino acids such as, leucine, and threonine (Scalise et al., 2018a). LAT1 is frequently overexpressed in solid tumors, including pancreatic, breast, and brain cancers (Sato et al., 2021; Okano et al., 2020). High LAT1 expression correlates with poor prognosis and resistance to standard therapies, reflecting its role in fueling mTORC1 signaling (Shibasaki et al., 2023). Pharmacological inhibitors of LAT1, such as JPH203, have entered early-phase clinical testing and demonstrated manageable safety profiles with preliminary signs of antitumor activity (Bo et al., 2021; Okano et al., 2020). More recent studies suggest that LAT1 also modulates the tumor immune microenvironment by controlling the amino acid supply to both tumor cells and infiltrating lymphocytes, making it a potential dual-purpose target (Zhao et al., 2025).

3.2 ASCT2 (SLC1A5)

The alanine/serine/cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2; gene name SLC1A5) primarily mediates glutamine uptake but also transports neutral amino acids. While glutamine metabolism is well established in cancer, ASCT2 is a vital target in nutrient uptake. Inhibitors such as C118P block ASCT2-mediated transport and demonstrate antitumor efficacy in preclinical breast cancer models (Lyu et al., 2023). Recent structural studies have improved the understanding of ASCT2’s substrate-binding dynamics, allowing for new inhibitors with greater selectivity. Because ASCT2 expression can be detected via immunohistochemistry or transcriptomic profiling, it is also being evaluated as a biomarker for glutamine dependence in patient tumors (Lyu et al., 2023; Garibsingh et al., 2021).

3.3 xCT (SLC7A11)

The cystine/glutamate antiporter (xCT; gene name SLC7A11) imports cystine in exchange for glutamate, coupling amino acid transport to redox homeostasis through glutathione synthesis (Hu et al., 2020). Overexpression of xCT protects tumors from oxidative stress but also creates therapeutic opportunities: targeting xCT sensitizes cancers to radiotherapy and ferroptosis-inducing agents (He et al., 2025; Yan et al., 2023). Recent work has shown that xCT levels predict response to radiotherapy in colorectal cancer liver metastases, highlighting its value as both a target and a clinical biomarker (He et al., 2025). Additionally, inhibitors of xCT are being explored in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, where depletion of cystine may amplify T cell–mediated oxidative killing (He et al., 2025; Messier et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2021).

3.4 SNAT2 (SLC38A2)

The sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2; gene name SLC38A2) regulates transport of alanine and other small neutral amino acids. SNAT2 expression is upregulated in nutrient-stressed tumors and correlates with therapy resistance (Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022). In ovarian cancers with ARID1A mutations, reliance on SNAT2-mediated alanine uptake has been identified as a selective vulnerability (Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022). Pharmacological inhibitors of SNAT2 are in preclinical development and demonstrate synergy with glucose metabolism inhibitors, demonstrating their role as a metabolic checkpoint (Jakobsen et al., 2023; Gauthier-Coles et al., 2022).

3.5 CAT1 (SLC7A1)

The cationic amino acid transporter 1 (CAT1; gene name SLC7A1) imports positively charged amino acids such as lysine and arginine. Recent studies link CAT1 to immune regulation, showing that lysine transport influences epigenetic programs that modulate interferon responses (You et al., 2022). In GBM, upregulation of lysine transport enhances histone crotonylation, leading to suppression of type I interferon signaling and immune evasion (Yuan et al., 2023). Although CAT1 has not yet been the focus of clinical trials, its role in metabolic–epigenetic reprogramming highlights its translational potential.

3.6 Transporters as imaging and circulating biomarkers

Amino acid transporters also provide opportunities for non-invasive imaging and biomarker development. Radiolabeled amino acid analogs such as 18F-fluoroethyltyrosine (FET) and 11C-methionine are used in PET to visualize transporter activity in vivo (Galldiks et al., 2023). Recent studies explore the use of LAT1-specific tracers to monitor tumor metabolism and treatment response dynamically (Achmad et al., 2025). In parallel, circulating metabolite profiles, such as plasma amino acid ratios, are being tested as functional markers of transporter activity, offering accessible biomarkers for patient selection in clinical trials (Chan et al., 2021; Zakharia et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2025).

3.7 Clinical and safety considerations for amino acid transporter-targeted therapies

As amino acid transporters continue to emerge as therapeutic targets, it is important to consider their functions in normal physiology to ensure treatment safety. Most of these transporters are not tumor-specific; they are also expressed in healthy tissues that rely on continuous amino acid exchange. LAT1, for example, is highly active at the blood–brain barrier and placenta, mediating the transfer of large neutral amino acids essential for brain and fetal development (Ohgaki et al., 2017). ASCT2 and SNAT1/2 regulate the movement of neutral amino acids across liver, muscle, and kidney cells, contributing to energy metabolism and osmotic balance (Scalise et al., 2018b; Ge et al., 2018), while xCT maintains antioxidant defense by exchanging cystine and glutamate in many epithelial tissues (Martis et al., 2020). Because of these physiological roles, broad or prolonged inhibition of these transporters can potentially cause nutrient imbalance, neurotoxicity, or organ dysfunction if monitoring is inadequate or drug exposure is not properly controlled. Early clinical and preclinical studies indicate that transporter inhibitors can be administered safely when dosing is well managed, but they also highlight the need for continuous safety assessment given the essential metabolic functions of these proteins. Emerging strategies such as tumor-targeted delivery systems, intermittent or adaptive dosing, and combination therapies are being developed to minimize systemic exposure while maintaining anti-tumor activity. Although transporter-targeting strategies such as LAT1 and ASCT2 inhibition show reproducible metabolic effects, clinical translation is constrained by transporter redundancy and expression in normal organs. These factors complicate dose optimization and emphasize the need for transporter-selective or tumor-targeted approaches. Integrating transporter biology with pharmacokinetic monitoring in future trials will be crucial for translating these approaches safely into clinical use.

4 Oncogenic regulation, opportunities and challenges for clinical translation

4.1 Oncogenic regulation of amino acid metabolism and transporters

Amino acid metabolism and transporter activity are tightly linked to oncogenic signaling. Many of the enzymes and transporters discussed in this review are directly regulated by transcription factors that coordinate nutrient use with cell growth and stress response. MYC (myelocytomatosis oncogene), one of the most studied oncogenes, increases the expression of several amino acid transporters, including ASCT2 and LAT1, to enhance amino acid uptake and sustain mTORC1 activity (Hansen et al., 2015). YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif), the downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway, also stimulate amino acid transport by upregulating LAT1, which promotes leucine uptake and mTORC1 signaling, especially under nutrient-limited conditions (Hansen et al., 2015; Bertolio et al., 2023). In addition, mutant p53 (tumor protein p53) reprograms amino acid metabolism by promoting serine–glycine synthesis and LAT1/CD98 expression, while repressing xCT through interaction with NRF2 (nuclear related factor 2), thereby altering redox balance and nutrient handling (Tombari et al., 2023). These oncogenic influences show that metabolic rewiring is not a passive adaptation to nutrient stress but a genetically driven feature of tumor progression. Recognizing how oncogenic drivers shape amino acid dependencies can guide both biomarker development and inform the design of pathway-specific therapeutic combinations.

4.2 Opportunities for translational targeting

4.2.1 Biomarker-driven patient selection

Clinical experience with arginine and tryptophan has shown that amino acid metabolism is most effectively targeted when linked to biomarkers, such as ASS1 loss for arginine or the kynurenine/tryptophan ratio for tryptophan catabolism. For emerging amino acids, parallel opportunities exist: plasma histidine depletion or high expression of histidine ammonia-lyase (HAL) may predict response to histidine–isoleucine supplementation; YRDC catalytic activity or elevated tRNA modification signatures could identify threonine-dependent glioblastomas; lysine-crotonylation signatures or GCDH overexpression may stratify patients for lysine restriction; and transporter expression, such as SNAT2 for alanine or LAT1 for histidine/isoleucine/threonine, could provide functional markers of dependency.

4.2.2 Exploiting nutrient surplus as a therapeutic target

Most metabolic therapies have focused on nutrient deprivation, such as starving tumors of arginine or methionine. By contrast, histidine and isoleucine supplementation demonstrate that amino acid supplementation can selectively induce tumor stress. This conceptual shift broadens the therapeutic approach, allowing tumors’ own metabolic vulnerabilities (such as amino acid export or catabolic upregulation) to be used against them.

4.2.3 Combination therapies and synergy

Just as glutaminase inhibition has shown greatest promise in combination with radiation or chemotherapy, emerging amino acid strategies may synergize with existing treatments. Histidine supplementation enhances gemcitabine activity by disrupting redox balance, lysine restriction boosts immune checkpoint blockade by reactivating interferon pathways, and alanine modulation sensitizes tumors to mitochondrial stress and chemotherapy. Rationally designed combinations could overcome the limited durability seen with single therapies.

4.2.4 Transporters as tractable drug targets and imaging tools

LAT1, SNAT2, and CAT1 represent pharmacologically accessible points that couple extracellular nutrient supply with tumor growth. Notably, transporter activity can also be visualized non-invasively through PET tracers, enabling real-time monitoring. This dual role, both as targets and biomarkers, strengthens the translational case for amino acid–based therapies.

4.3 Challenges

4.3.1 Tumor microenvironment metabolism and therapy resistance

Amino acid metabolism in tumors represents a network shared between cancer cells, stromal fibroblasts, and immune populations within the tumor microenvironment (TME). This metabolic cooperation shapes both nutrient access and treatment response. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can secrete alanine, sustaining oxidative metabolism in pancreatic tumors during nutrient stress (Sousa et al., 2016), while aspartate-glutamate exchange between stromal and tumor cells buffers redox status and supports biosynthesis (Be et al., 2019). Within the immune compartment, depletion of tryptophan by IDO1/TDO2 and arginine by myeloid cells suppresses T-cell proliferation and effector function (Günther et al., 2019). Beyond these established pathways, emerging amino acid dependencies, such as those involving histidine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine, or alanine, may further influence the TME by modifying oxidative balance, nutrient signaling, and stress adaptation. Integrating these newer observations with known mechanisms suggests that tumors exploit a flexible amino acid economy in which both stromal support and immune suppression converge to sustain growth. This metabolic reciprocity explains why amino acid-targeted interventions often show context-dependent efficacy and demonstrates the need for therapeutic strategies that account for tumor microenvironmental nutrient exchange, immune cell competition, and tumor metabolic plasticity. These tumor-stromal-immune exchanges illustrate the multifactorial nature of amino acid metabolism in the TME, setting the stage for broader challenges in clinical translation. Collectively, the studies reviewed provide valuable mechanistic insight but vary in translational depth. Many rely on metabolic or xenograft models that simplify the TME, whereas patient-derived organoids and isotope tracing in clinical samples remain limited. These methodological differences partly explain why results are sometimes inconsistent across tumor types. Recognizing these constraints allows a more accurate assessment of which amino-acid pathways are most actionable in patients.

4.3.2 Metabolic plasticity and adaptive resistance

Experience with arginine and glutamine has shown how tumors adapt when a single nutrient pathway is blocked, rerouting flux through compensatory pathways. Emerging strategies will face similar resistance: tumors may adjust transporter expression, shift metabolic routing, or draw on stromal support to bypass amino acid targeting.

4.3.3 Balancing systemic safety with tumor selectivity

Unlike small-molecule inhibitors with defined targets, dietary or metabolic interventions risk perturbing systemic amino acid pools. Although preclinical studies suggest that histidine, isoleucine, and threonine interventions are tolerated, long-term effects on protein synthesis, immune function, and normal tissue homeostasis must be carefully evaluated.

4.3.4 Heterogeneity of tumor microenvironment

Alanine exemplifies how stromal fibroblasts supply tumors with metabolic support. This highlights a challenge: vulnerabilities may not arise from tumor cells alone but from the interaction between tumor and microenvironment. Therapies will need to consider this complexity, as targeting stromal-tumor nutrient exchange is inherently more difficult than inhibiting tumor-intrinsic enzymes.

4.3.5 Limited clinical data and trial design hurdles

While arginine and glutamine have advanced into randomized trials, most emerging amino acid strategies remain in early preclinical stages. Translating them will require innovative trial designs, such as adaptive protocols that pivot therapy upon biomarker-detected resistance, as well as careful patient selection to ensure only biomarker-positive patients are enrolled.

4.4 Future direction

The successful translation of emerging amino acid therapies will depend on a precision-guided approach. This means linking basic mechanistic insights with reliable biomarkers, designing smart treatment combinations, and selecting patients based on their genetic or metabolic profile. For example, methionine restriction is being tested with radiation therapy, and arginine depletion is used in patients whose tumors lack ASS1. In the same way, new amino acid strategies must align the biology of each target with matching biomarkers and treatment designs. Equally important, future progress will require integrating these mechanistic findings with carefully designed clinical studies that address current limitations in model relevance, patient selection, and biomarker validation. Combining metabolic profiling with functional assays in patient-derived systems will help distinguish true causal dependencies from correlative observations, ensuring that only the most actionable pathways advance into clinical testing. Incorporating transporter biology, monitoring plasma metabolite levels, and building rational combinations with existing therapies will be key to moving these approaches from preclinical promise to real clinical benefit.

5 Conclusion

Amino acid metabolism is a promising frontier in cancer research. Established interventions such as arginine depletion, glutaminase inhibition, tryptophan catabolism blockade, and methionine restriction have demonstrated both the feasibility and the complexity of targeting metabolic pathways in patients. Building on these lessons, recent discoveries highlight histidine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine, and alanine as new amino acid dependencies with translational potential. Each of these amino acids introduces distinct mechanisms, from selective cytotoxicity and redox imbalance to translational control, epigenetic reprogramming, and stromal–tumor nutrient exchange. Notably, these new targets are closely tied to amino acid transporters such as LAT1, CAT1, and SNAT2, which function as metabolic gateways and potential therapeutic targets or imaging biomarkers. This dual role strengthens the rationale for incorporating transporters into biomarker-driven clinical strategies. Opportunities include exploiting nutrient surplus, pairing amino-acid modulation with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy, and deploying functional biomarkers for patient selection. Challenges include metabolic plasticity, microenvironmental heterogeneity, and the need for careful trial design to balance systemic safety with tumor selectivity. Looking forward, progress will depend on precision-oriented implementation that combines mechanistic insight with biomarker development and rational therapeutic combinations. By aligning amino acid mechanisms with transporter targeting, metabolic imaging, and patient selection, the field can move closer to translating emerging amino acid dependencies into durable clinical benefit. Ultimately, integrating these strategies into precision oncology frameworks has the potential to expand treatment options and improve outcomes for patients with some of the most difficult-to-treat cancers.

Author contributions

AA: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. EO: Validation, Writing – review and editing. TG: Validation, Writing – review and editing. DS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R21CA270748) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM128729) of National Institutes of Health to DS, National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER Award (#2236885) to DS, Advance Industries Grant award from Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade to DS.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Achmad, A., Hanaoka, H., Holik, H. A., Endo, K., Tsushima, Y., and Kartamihardja, A. H. S. (2025). LAT1-specific PET radiotracers: development and clinical experiences of a new class of cancer-specific radiopharmaceuticals. Theranostics 15, 1864–1878. doi:10.7150/THNO.99490

Akinlalu, A., Flaten, Z., Rasuleva, K., Mia, M. S., Bauer, A., Elamurugan, S., et al. (2024). Integrated proteomic profiling identifies amino acids selectively cytotoxic to pancreatic cancer cells. Innov. Camb. (Mass) 5, 100626. doi:10.1016/J.XINN.2024.100626

Akinlalu, A., Gao, T., Gao, S., and Sun, D. (2025). Collective attributes of extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for cancer detection. Cancer Detect. Diagnosis, 357–363. doi:10.1201/9781003449942-44

Balamurugan, R. S., Asad, Y., Gao, T., Nawarathna, D., Tida, U. R., and Sun, D. (2025). Automating the amino acid identification in elliptical dichroism spectrometer with machine learning. PLoS One 20, e0317130. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0317130

Bertero, T., Oldham, W. M., Grasset, E. M., Bourget, I., Boulter, E., Pisano, S., et al. (2019). Tumor-stroma mechanics coordinate amino acid availability to sustain tumor growth and malignancy. Cell Metab. 29, 124–140.e10. doi:10.1016/J.CMET.2018.09.012

Bernasocchi, T., and Mostoslavsky, R. (2024). Subcellular one carbon metabolism in cancer, aging and epigenetics. Front. Epigenetics Epigenomics 2, 1451971. doi:10.3389/FREAE.2024.1451971

Bertolio, R., Napoletano, F., and Del Sal, G. (2023). Dynamic links between mechanical forces and metabolism shape the tumor milieu. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 84, 102218. doi:10.1016/J.CEB.2023.102218

Bo, T., Kobayashi, S., Inanami, O., Fujii, J., Nakajima, O., Ito, T., et al. (2021). LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 sensitizes cancer cells to radiation by enhancing radiation-induced cellular senescence. Transl. Oncol. 14, 101212. doi:10.1016/J.TRANON.2021.101212

Campesato, L. F., Budhu, S., Tchaicha, J., Weng, C. H., Gigoux, M., Cohen, I. J., et al. (2020). Blockade of the AHR restricts a Treg-macrophage suppressive axis induced by L-Kynurenine. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 4011–11. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17750-z

Carpentier, J., Freitas, M., Morales, V., Bianchi, K., Bomalaski, J., Szlosarek, P., et al. (2024). Overcoming resistance to arginine deprivation therapy using GC7 in pleural mesothelioma. iScience 28, 111525. doi:10.1016/J.ISCI.2024.111525

Chan, S. L., Cheng, P. N. M., Liu, A. M., Chan, L. L., Li, L., Chu, C. M., et al. (2021). A phase II clinical study on the efficacy and predictive biomarker of pegylated recombinant arginase on hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs 39, 1375–1382. doi:10.1007/s10637-021-01111-8

Chan, P. Y., Phillips, M. M., Ellis, S., Johnston, A., Feng, X., Arora, A., et al. (2022). A phase 1 study of ADI-PEG20 (pegargiminase) combined with cisplatin and pemetrexed in ASS1-negative metastatic uveal melanoma. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 35, 461–470. doi:10.1111/PCMR.13042

Chang, Y., Wang, N., Li, S., Zhang, J., Rao, Y., Xu, Z., et al. (2025). SLC3A2-Mediated lysine uptake by cancer cells restricts T-cell activity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 85, 2250–2267. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-24-3180

Chen, J., Zhao, L., Li, W., Wang, S., Li, J., Lv, Z., et al. (2025). Glutamine-driven metabolic reprogramming promotes CAR-T cell function through mTOR-SREBP2 mediated HMGCS1 upregulation in ovarian cancer. J. Transl. Med. 23, 803–817. doi:10.1186/s12967-025-06853-0

Ciombor, K. K., Bae, S. W., Whisenant, J. G., Ayers, G. D., Sheng, Q., Peterson, T. E., et al. (2025). Results of the phase I/II study and preliminary B-cell gene signature of combined inhibition of glutamine metabolism and EGFR in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 31, 1437–1448. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-3133

De Simone, R., Vissicchio, F., Mingarelli, C., De Nuccio, C., Visentin, S., Ajmone-Cat, M. A., et al. (2013). Branched-chain amino acids influence the immune properties of microglial cells and their responsiveness to pro-inflammatory signals. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1832, 650–659. doi:10.1016/J.BBADIS.2013.02.001

Dimou, A., Tsimihodimos, V., and Bairaktari, E. (2022). The critical role of the branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) catabolism-regulating enzymes, branched-chain aminotransferase (BCAT) and branched-chain α-Keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKD), in human pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 4022. doi:10.3390/IJMS23074022

DiNardo, C. D., Verma, D., Baran, N., Bhagat, T. D., Skwarska, A., Lodi, A., et al. (2024). Glutaminase inhibition in combination with azacytidine in myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 1b/2 clinical trial and correlative analyses. Nat. Cancer 5 (5), 1515–1533. doi:10.1038/s43018-024-00811-3

Ducker, G. S., and Rabinowitz, J. D. (2017). One-carbon metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 25, 27–42. doi:10.1016/J.CMET.2016.08.009

Galldiks, N., Lohmann, P., Fink, G. R., and Langen, K. J. (2023). Amino acid PET in neurooncology. J. Nucl. Med. 64, 693–700. doi:10.2967/JNUMED.122.264859

Garibsingh, R. A. A., Ndaru, E., Garaeva, A. A., Shi, Y., Zielewicz, L., Zakrepine, P., et al. (2021). Rational design of ASCT2 inhibitors using an integrated experimental-computational approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2104093118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2104093118

Gauthier-Coles, G., Bröer, A., McLeod, M. D., George, A. J., Hannan, R. D., and Bröer, S. (2022). Identification and characterization of a novel SNAT2 (SLC38A2) inhibitor reveals synergy with glucose transport inhibition in cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 963066. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.963066

Ge, Y., Gu, Y., Wang, J., and Zhang, Z. (2018). Membrane topology of rat sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2). Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 1860, 1460–1469. doi:10.1016/J.BBAMEM.2018.04.005

Ghorani, E., Swanton, C., and Quezada, S. A. (2023). Cancer cell-intrinsic mechanisms driving acquired immune tolerance. Immunity 56, 2270–2295. doi:10.1016/J.IMMUNI.2023.09.004

Gouda, M. A., Voss, M. H., Tawbi, H., Gordon, M., Tykodi, S. S., Lam, E. T., et al. (2025). A phase I/II study of the safety and efficacy of telaglenastat (CB-839) in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open 10, 104536. doi:10.1016/J.ESMOOP.2025.104536

Gounder, M., Johnson, M., Heist, R. S., Shapiro, G. I., Postel-Vinay, S., Wilson, F. H., et al. (2025). MAT2A inhibitor AG-270/S095033 in patients with advanced malignancies: a phase I trial. Nat. Commun. 16, 423. doi:10.1038/S41467-024-55316-5

Günther, J., Däbritz, J., and Wirthgen, E. (2019). Limitations and off-target effects of tryptophan-related IDO inhibitors in cancer treatment. Front. Immunol. 10, 1801. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01801

Guo, C., You, Z., Shi, H., Sun, Y., Du, X., Palacios, G., et al. (2023). SLC38A2 and glutamine signalling in cDC1s dictate anti-tumour immunity. Nature 620, 200–208. doi:10.1038/S41586-023-06299-8

Han, Q., and Hoffman, R. M. (2021). Lowering and stabilizing PSA levels in advanced-prostate cancer patients with oral methioninase. Anticancer Res. 41, 1921–1926. doi:10.21873/ANTICANRES.14958

Hansen, C. G., Ng, Y. L. D., Lam, W. L. M., Plouffe, S. W., and Guan, K. L. (2015). The hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell Res. 25 (12), 1299–1313. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.140

Harris, K. A., Jones, V., Bilbille, Y., Swairjo, M. A., and Agris, P. F. (2011). YrdC exhibits properties expected of a subunit for a tRNA threonylcarbamoyl transferase. RNA 17, 1678–1687. doi:10.1261/RNA.2592411

He, J., Zhang, Y., Luo, S., Zhao, Z., Mo, T., Guan, H., et al. (2025). Targeting SLC7A11 with sorafenib sensitizes stereotactic body radiotherapy in colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Drug Resist. Updat. 81, 101250. doi:10.1016/J.DRUP.2025.101250

Hu, K., Li, K., Lv, J., Feng, J., Chen, J., Wu, H., et al. (2020). Suppression of the SLC7A11/glutathione axis causes synthetic lethality in KRAS-Mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Invest 130, 1752–1766. doi:10.1172/JCI124049

Huang, X., Zhang, F., Wang, X., and Liu, K. (2022). The role of indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase 1 in regulating tumor microenvironment. Cancers 14 (14), 2756. doi:10.3390/CANCERS14112756

Jakobsen, S., Petersen, E. F., and Nielsen, C. U. (2023). Investigations of potential non-amino acid SNAT2 inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1302445. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1302445

Jing, Y., Kobayashi, M., Shoulkamy, M. I., Zhou, M., Thi Vu, H., Arakawa, H., et al. (2025). Lysine-arginine imbalance overcomes therapeutic tolerance governed by the transcription factor E3-lysosome axis in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 16 (1), 2876–20. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56946-z

Johal, A. S., Al-Shekaili, H. H., Abedrabbo, M., Kehinde, A. Z., Towriss, M., Koe, J. C., et al. (2024). Restricting lysine normalizes toxic catabolites associated with ALDH7A1 deficiency in cells and mice. Cell Rep. 43, 115069. doi:10.1016/J.CELREP.2024.115069

Kessler, A. T., and Raja, A. (2023). Biochemistry, histidine. StatPearls. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538201/ (Accessed September 28, 2025).

Kumar, N., Rachagani, S., Natarajan, G., Crook, A., Gopal, T., Rajamanickam, V., et al. (2023). Histidine enhances the anticancer effect of gemcitabine against pancreatic cancer via disruption of amino acid homeostasis and oxidant-antioxidant balance. Cancers (Basel) 15, 2593. doi:10.3390/CANCERS15092593

Kuroki, K., Rikimaru, F., Kunitake, N., Toh, S., Higaki, Y., and Masuda, M. (2023). Efficacy of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, arginine, and glutamine for the prevention of mucositis induced by platinum-based chemoradiation in head and neck cancer: a phase II study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 57, 730–734. doi:10.1016/J.CLNESP.2023.08.027

Lee, C. H., Motzer, R., Emamekhoo, H., Matrana, M., Percent, I., Hsieh, J. J., et al. (2022). Telaglenastat plus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase II ENTRATA trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 3248–3255. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0061

Liu, X., Ren, B., Ren, J., Gu, M., You, L., and Zhao, Y. (2024). The significant role of amino acid metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal 22, 380. doi:10.1186/S12964-024-01760-1

Lyu, X. D., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Wei, Y. C., Han, Y., Li, X., et al. (2023). A novel ASCT2 inhibitor, C118P, blocks glutamine transport and exhibits antitumour efficacy in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 15, 5082. doi:10.3390/cancers15205082

Ma, Y., Zhao, X., Pan, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., and Ge, S. (2024). Early intravenous branched-chain amino acid-enriched nutrition supplementation in older patients undergoing gastric surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Nutr. J. 23, 137. doi:10.1186/S12937-024-01041-0

Martis, R. M., Knight, L. J., Donaldson, P. J., and Lim, J. C. (2020). Identification, expression, and roles of the cystine/glutamate antiporter in ocular tissues. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 4594606. doi:10.1155/2020/4594606

Matsui, R., Sagawa, M., Inaki, N., Fukunaga, T., and Nunobe, S. (2024). Impact of perioperative immunonutrition on postoperative outcomes in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 16, 577. doi:10.3390/NU16050577

Mattes, M. D., Koturbash, I., Leung, C. N., Geraldine, S., and Jacobson, M. M. (2024). A phase I trial of a methionine restricted diet with concurrent radiation therapy. Nutr. Cancer 76, 463–468. doi:10.1080/01635581.2024.2340784

McDonnell, D., Afolabi, P. R., Niazi, U., Wilding, S., Griffiths, G. O., Swann, J. R., et al. (2025). Metabolite changes associated with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 17, 1150. doi:10.3390/cancers17071150

Messier, T., Gibson, V., Bzura, A., Dzialo, J., Poile, C., Stead, S., et al. (2024). Abstract 384: SLC7A11 modulates sensitivity to the first-in-class mitochondrial peroxiredoxin 3 inhibitor thiostrepton (RSO-021) via a ferroptosis independent pathway. Cancer Res. 84, 384. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-384

Nie, H., Liao, L., Zielinski, R. J., Gomez, J. A., Basi, A. V., Seeley, E. H., et al. (2025). Selective alanine transporter utilization is a therapeutic vulnerability in ARID1A-Mutant ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 85, 3471–3489. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-25-0654

Ohgaki, R., Ohmori, T., Hara, S., Nakagomi, S., Kanai-Azuma, M., Kaneda-Nakashima, K., et al. (2017). Essential roles of L-Type amino acid transporter 1 in syncytiotrophoblast development by presenting fusogenic 4F2hc. Mol. Cell Biol. 37, e00427. doi:10.1128/MCB.00427-16

Okano, N., Naruge, D., Kawai, K., Kobayashi, T., Nagashima, F., Endou, H., et al. (2020). First-in-human phase I study of JPH203, an L-type amino acid transporter 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 38, 1495–1506. doi:10.1007/S10637-020-00924-3

Parker, S. J., Amendola, C. R., Hollinshead, K. E. R., Yu, Q., Yamamoto, K., Encarnación-Rosado, J., et al. (2020). Selective alanine transporter utilization creates a targetable metabolic niche in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 10, 1018–1037. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0959

Patel, R., Cooper, D. E., Kadakia, K. T., Allen, A., Duan, L., Luo, L., et al. (2024). Targeting glutamine metabolism improves sarcoma response to radiation therapy in vivo. Commun. Biol. 7 (7), 608–614. doi:10.1038/s42003-024-06262-x

Perrochia, L., Crozat, E., Hecker, A., Zhang, W., Bareille, J., Collinet, B., et al. (2013). In vitro biosynthesis of a universal t6A tRNA modification in archaea and eukarya. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1953–1964. doi:10.1093/NAR/GKS1287

Rasuleva, K., Elamurugan, S., Bauer, A., Khan, M., Wen, Q., Li, Z., et al. (2021). β-Sheet richness of the circulating tumor-derived extracellular vesicles for noninvasive pancreatic cancer screening. ACS Sens. 6, 4489–4498. doi:10.1021/acssensors.1c02022

Rasuleva, K., Jangili, K. P., Akinlalu, A., Guo, A., Borowicz, P., Li, C. Z., et al. (2023). EvIPqPCR, target circulating tumorous extracellular vesicles for detection of pancreatic cancer. Anal. Chem. 95, 10353–10361. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.3c01218

Rogers, L. C., Kremer, J. C., Brashears, C. B., Lin, Z., Hu, Z., Bastos, A. C. S., et al. (2023). Discovery and targeting of a noncanonical mechanism of sarcoma resistance to ADI-PEG20 mediated by the microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 3189–3202. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2642

Sato, M., Harada-Shoji, N., Toyohara, T., Soga, T., Itoh, M., Miyashita, M., et al. (2021). L-type amino acid transporter 1 is associated with chemoresistance in breast cancer via the promotion of amino acid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 589–11. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80668-5

Saxton, R. A., and Sabatini, D. M. (2017). mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 168, 960–976. doi:10.1016/J.CELL.2017.02.004

Scalise, M., Galluccio, M., Console, L., Pochini, L., and Indiveri, C. (2018a). The human SLC7A5 (LAT1): the intriguing histidine/large neutral amino acid transporter and its relevance to human health. Front. Chem. 6, 243. doi:10.3389/fchem.2018.00243

Scalise, M., Pochini, L., Console, L., Losso, M. A., and Indiveri, C. (2018b). The human SLC1A5 (ASCT2) amino acid transporter: from function to structure and role in cell biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 6, 96. doi:10.3389/fcell.2018.00096

Schlichtner, S., Yasinska, I. M., Klenova, E., Abooali, M., Lall, G. S., Berger, S. M., et al. (2023). L-Kynurenine participates in cancer immune evasion by downregulating hypoxic signaling in T lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology 12, 2244330. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2023.2244330

Shah, H., Gannaban, R. B., Haque, Z. F., Dehghani, F., Kramer, A., Bowers, F., et al. (2024). BCAAs acutely drive glucose dysregulation and insulin resistance: role of AgRP neurons. Nutr. and Diabetes 14 (1), 40–14. doi:10.1038/s41387-024-00298-y

Shi, J., Pabon, K., Ding, R., and Scotto, K. W. (2024). ABCG2 and SLC1A5 functionally interact to rewire metabolism and confer a survival advantage to cancer cells under oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 107299. doi:10.1016/J.JBC.2024.107299

Shibasaki, Y., Yokobori, T., Sohda, M., Shioi, I., Ozawa, N., Komine, C., et al. (2023). Association of high LAT1 expression with poor prognosis and recurrence in colorectal cancer patients treated with oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2604. doi:10.3390/IJMS24032604

Sousa, C. M., Biancur, D. E., Wang, X., Halbrook, C. J., Sherman, M. H., Zhang, L., et al. (2016). Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 536 (536), 479–483. doi:10.1038/nature19084

Strømland, P. P., Bertelsen, B. E., Viste, K., Chatziioannou, A. C., Bellerba, F., Robinot, N., et al. (2025). Effects of metformin on transcriptomic and metabolomic profiles in breast cancer survivors enrolled in the randomized placebo-controlled MetBreCS trial. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 16897–13. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-01705-9

Szlosarek, P. W., Wimalasingham, A. G., Phillips, M. M., Hall, P. E., Chan, P. Y., Conibear, J., et al. (2021). Phase 1, pharmacogenomic, dose-expansion study of pegargiminase plus pemetrexed and cisplatin in patients with ASS1-deficient non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 10, 6642–6652. doi:10.1002/CAM4.4196

Szlosarek, P. W., Creelan, B. C., Sarkodie, T., Nolan, L., Taylor, P., Olevsky, O., et al. (2024). Pegargiminase plus first-line chemotherapy in patients with nonepithelioid pleural mesothelioma: the ATOMIC-meso randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 10, 475–483. doi:10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2023.6789

Tang, Q., Tan, P., Ma, N., and Ma, X. (2021). Physiological functions of threonine in animals: beyond nutrition metabolism. Nutrients 13 (13), 2592. doi:10.3390/NU13082592

Tokito, T., Kolesnik, O., Sørensen, J., Artac, M., Quintela, M. L., Lee, J. S., et al. (2024). Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab as first-line treatment for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with high levels of programmed death-ligand 1: a randomized, double-blind phase 2 study. BMC Cancer 23, 1–11. doi:10.1186/S12885-023-11203-8/FIGURES/3

Tombari, C., Zannini, A., Bertolio, R., Pedretti, S., Audano, M., Triboli, L., et al. (2023). Mutant p53 sustains serine-glycine synthesis and essential amino acids intake promoting breast cancer growth. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 6777–21. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42458-1

Tong, H., Jiang, Z., Song, L., Tan, K., Yin, X., He, C., et al. (2024). Dual impacts of serine/glycine-free diet in enhancing antitumor immunity and promoting evasion via PD-L1 lactylation. Cell Metab. 36, 2493–2510.e9. doi:10.1016/J.CMET.2024.10.019

Tsujimoto, T., Wasa, M., Inohara, H., and Ito, T. (2023). L-Glutamine and survival of patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy. Nutrients 15 (15), 4117. doi:10.3390/NU15194117

Wang, Z. A., and Cole, P. A. (2020). The chemical biology of reversible lysine post-translational modifications. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 953–969. doi:10.1016/J.CHEMBIOL.2020.07.002

Wicker, C. A., Hunt, B. G., Krishnan, S., Aziz, K., Parajuli, S., Palackdharry, S., et al. (2021). Glutaminase inhibition with telaglenastat (CB-839) improves treatment response in combination with ionizing radiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma models. Cancer Lett. 502, 180–188. doi:10.1016/J.CANLET.2020.12.038

Wu, C., Spector, S. A., Theodoropoulos, G., Nguyen, D. J. M., Kim, E. Y., Garcia, A., et al. (2023). Dual inhibition of IDO1/TDO2 enhances anti-tumor immunity in platinum-resistant non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer and Metabolism 11 (11), 7–22. doi:10.1186/S40170-023-00307-1

Wu, X., Yuan, H., Wu, Q., Gao, Y., Duan, T., Yang, K., et al. (2024). Threonine fuels glioblastoma through YRDC-Mediated codon-biased translational reprogramming. Nat. Cancer 5, 1024–1044. doi:10.1038/S43018-024-00748-7

Wu, H., Zhang, Q., Cao, Z., Cao, H., Wu, M., Fu, M., et al. (2025). Integrated spatial omics of metabolic reprogramming and the tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. iScience 28, 112681. doi:10.1016/J.ISCI.2025.112681

Xu, F., Guan, Y., Xue, L., Zhang, P., Li, M., Gao, M., et al. (2021). The roles of ferroptosis regulatory gene SLC7A11 in renal cell carcinoma: a multi-omics study. Cancer Med. 10, 9078–9096. doi:10.1002/cam4.4395

Yan, Y., Teng, H., Hang, Q., Kondiparthi, L., Lei, G., Horbath, A., et al. (2023). SLC7A11 expression level dictates differential responses to oxidative stress in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 3673–15. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39401-9

Yap, T. A., Rixe, O., Baldini, C., Brown-Glaberman, U., Efuni, S., Hong, D. S., et al. (2025). First-in-human phase 1 study of KHK2455 monotherapy and in combination with mogamulizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer 131, e35939. doi:10.1002/CNCR.35939

You, S., Zhu, X., Yang, Y., Du, X., Song, K., Zheng, Q., et al. (2022). SLC7A1 overexpression is involved in energy metabolism reprogramming to induce tumor progression in epithelial ovarian cancer and is associated with immune-infiltrating cells. J. Oncol. 2022, 5864826. doi:10.1155/2022/5864826

Yuan, H., Wu, X., Wu, Q., Chatoff, A., Megill, E., Gao, J., et al. (2023). Lysine catabolism reprograms tumour immunity through histone crotonylation. Nature 617 (617), 818–826. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06061-0

Zakharia, Y., McWilliams, R. R., Rixe, O., Drabick, J., Shaheen, M. F., Grossmann, K. F., et al. (2021). Phase II trial of the IDO pathway inhibitor indoximod plus pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with advanced melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, e002057. doi:10.1136/JITC-2020-002057

Zhao, Y., Pu, C., Liu, K., and Liu, Z. (2025). Targeting LAT1 with JPH203 to reduce TNBC proliferation and reshape suppressive immune microenvironment by blocking essential amino acid uptake. Amino Acids 57, 27–16. doi:10.1007/s00726-025-03456-3

Zhu, X., Fu, Z., Chen, S. Y., Ong, D., Aceto, G., Ho, R., et al. (2023). Alanine supplementation exploits glutamine dependency induced by SMARCA4/2-loss. Nat. Commun. 14, 2894. doi:10.1038/S41467-023-38594-3

Glossary

1C One carbon

AA Amino acid

ADI-PEG 20 Pegylated arginine deiminase

AHR Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

ALT2/GPT2 Alanine Aminotransferase 2 (Glutamic-Pyruvic Transaminase 2)

ASCT2 (SLC1A5) Alanine-Serine-Cysteine Transporter 2

ASS1 Argininosuccinate Synthase 1

BCAAs Branched-Chain Amino Acids

CAT1 (SLC7A1) Cationic amino acid transporter 1

EVs Extracellular vesicles

GBM Glioblastoma (glioblastoma multiforme)

GCDH Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase

GLS Glutaminase

GSH Reduced glutathione (GSSG = oxidized glutathione)

HCC Hepatocellular carcinoma

HAL Histidine ammonia-lyase

ICI Immune checkpoint inhibitor

IDO1/TDO2 Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1/Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase 2

IHC Immunohistochemistry

Kyn/Trp Kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio

LAT1 (SLC7A5) L-type amino acid transporter 1

mTORC1 Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

NSCLC Non-small cell lung cancer

PD-1 Programmed cell death protein 1

PDAC Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

PET Positron emission tomography

ROS Reactive oxygen species

SLC Solute carrier (transporter family prefix)

SNAT2 (SLC38A2) Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 2

TCA cycle Tricarboxylic acid cycle

t6A N6-threonylcarbamoyl adenosine (tRNA modification)

Trp Tryptophan

xCT (SLC7A11) Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter

XRN1 5′→3′exoribonuclease 1

YRDC YrdC-domain–containing protein (enzyme for t6A formation)

Keywords: amino acid metabolism, cancer therapy, nutritional intervention, dietary modulation, metabolic targeting, amino acid transporters, glutaminase inhibition, SLC transporters

Citation: Akinlalu A, Ogberefor E, Gao T and Sun D (2025) Targeting emerging amino acid dependencies and transporters in cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1717414. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1717414

Received: 01 October 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Maurizio Ragni, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Gisele Monteiro, University of São Paulo, BrazilGiannino Del Sal, University of Trieste, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Akinlalu, Ogberefor, Gao and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dali Sun, ZGFsaS5zdW5AZHUuZWR1

Alfred Akinlalu

Alfred Akinlalu Emmanuel Ogberefor

Emmanuel Ogberefor Tommy Gao

Tommy Gao Dali Sun

Dali Sun