Abstract

Cancer is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, prioritizing the search for new therapies with improved toxicity profiles. Natural products, such as essential oils (EOs), are a valuable source of potential chemotherapeutic agents. Gomortega keule, a Chilean endemic tree, has traditional uses, but its cytotoxic potential remains unexplored. This study investigated the chemical composition and cytotoxic activity of Gomortega keule leaf EO. The chemical analysis revealed a unique profile rich in diterpenes (>50%), mainly phyllocladene (28.08%) and kaur-16-ene (19.74%), suggesting a distinct chemotype. The EO demonstrated potent cytotoxic activity against breast (MCF-7), prostate (PC-3), and colon (HT-29) cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 3.97, 2.43, and 9.76 μg/mL, respectively. Remarkably, the EO exhibited exceptional selectivity, proving significantly more toxic to cancer cells than to non-tumorigenic cells. Specifically, it achieved a Selectivity Index (SI) of 24.01 for breast cancer cells compared to normal MCF-10A cells. Crucially, this selectivity profile significantly outperformed standard chemotherapeutic agents (daunorubicin and 5-fluorouracil), which displayed high toxicity towards healthy cells in this model. The mechanism of action involves the selective induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to mitochondrial membrane depolarization (ΔΨm) and caspase activation, culminating in apoptotic cell death. These findings highlight G. keule EO as a promising source for developing selective cytotoxic agents.

1 Introduction

Malignant neoplasms represent one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Projections from the GLOBOCAN project estimate that the global cancer burden reached nearly 20 million new cases in 2022, a figure expected to rise to 35 million by 2050 (Bray et al., 2024). Within this landscape, colorectal cancer ranks as the third most common cancer in the world (Ferlay et al., 2012; World Health Organization, 2023). Meanwhile, breast cancer is the most diagnosed neoplasm in women, and prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed in men, both representing a significant portion of the global oncological burden in terms of incidence and mortality (Bray et al., 2024; Palshof et al., 2024; Zahed et al., 2024). Conventional therapies, such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, remain the mainstay of treatment. However, their efficacy is often limited by the appearance of significant adverse side effects and the development of chemoresistance, a phenomenon that contributes to therapeutic failure in approximately 90% of patients with metastatic disease (Fernandez-Muñoz et al., 2025). This limitation has prompted the search for alternative and complementary therapies, with a particular focus on natural products that may act as chemotherapeutic or chemopreventive agents with more favorable toxicity profiles.

In this context, natural products of plant origin have re-emerged as an invaluable source of new bioactive compounds (Sharma et al., 2022). For colorectal cancer, the use of compounds such as curcumin and resveratrol as adjuvants to improve the response to standard chemotherapy has been extensively investigated (Fernandez-Muñoz et al., 2025). Furthermore, essential oils (EOs) have shown promise as a therapeutic tool, with studies demonstrating their cytotoxic, antiproliferative, and antimetastatic effects on cell lines of this cancer type (Garzoli et al., 2022). The use of oils like lavender has even been explored to improve the quality of life for patients with a colostomy (Duluklu and Şenol Çelik, 2019). Similarly, in breast cancer, EOs have been the subject of numerous systematic reviews confirming their pharmacological activity. Compounds such as monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes have been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit cell proliferation (Mustapa et al., 2022). Specific studies, such as one conducted with Oliveria decumbens EO, have revealed not only pro-apoptotic effects but also a potent immunomodulatory effect, suggesting that its mechanism of action extends beyond direct cytotoxicity and may involve the activation of the host immune system (Jamali et al., 2020). Regarding prostate cancer, where the use of complementary and alternative medicines is particularly common among patients (Patterson et al., 2002), various natural products such as pomegranate extract, green tea, and curcumin have been studied (Klempner and Bubley, 2012). Recently, ethnopharmacological research has explored native South American plants; for example, the Fabiana imbricata EO, a Patagonian plant, has been shown to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species (Madrid et al., 2025).

Ethnopharmacological knowledge, which explores the traditional uses of medicinal plants, is a fundamental tool for guiding the discovery of new therapeutic agents (Manosroi et al., 2006). A notable example is found in southern Chile: G. keule (Mol.) Baillon, an endemic tree commonly known as Queule. This species, the sole representative of the Gomortegaceae family, is considered a botanical relict and an ancient lineage. It is an evergreen tree that can reach up to 30 m in height, with a discontinuous distribution in the Coastal Range between the Maule and Biobío regions (Muñoz-Concha and Garrido-Werner, 2011; Crowley, 2020). This tree not only holds great scientific interest but also has deep cultural roots in the cosmovision of the Mapuche people, where it is considered a sacred tree, a source of strength and energy (newen) (Torri, 2010). Its traditional use in popular medicine, including the preparation of beverages from its yellow fruits, has been well documented (Muñoz-Concha and Garrido-Werner, 2011; Crowley, 2020). Modern science has begun to validate this ancestral knowledge; on one hand, it has been demonstrated that its EOs possess potent antioxidant activity (Simirgiotis et al., 2013). On the other hand, its antifungal efficacy has been confirmed against phytopathogenic fungi (Becerra et al., 2010) and, more directly relevant to human health, against yeasts of the genus Candida (Montenegro et al., 2025). However, its cytotoxic potential remains largely unexplored. Building upon its rich ethnopharmacological history and its already validated biological activities, the present study aims to investigate the potential of Gomortega keule EO as a cytotoxic agent against prostate, colon, and breast cancer. Specifically, this work evaluates the oil’s cytotoxic and selective activity, and delves into its pro-apoptotic mechanism to offer the first comprehensive assessment of its value as a source of novel cytotoxic compounds.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Daunorubicin (CAS 23541-50-6), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; CAS 51-21-8), and 2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH; CAS 2997-92-4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions of these agents were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or sterile water according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For biological assays, the G. keule EO was dissolved in ethanol (absolute grade, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to create stock solutions. It is important to note that while dichloromethane was used as the solvent for GC/MS analysis to ensure optimal volatility for chemical profiling, ethanol was selected for cell culture experiments due to its lower cytotoxicity and compatibility with live-cell assays. The final concentration of ethanol in the culture medium never exceeded 0.1% (v/v) to ensure no interference with cell viability.

2.2 Plant material

Leaves of G. keule were collected during the winter (July 2024) near the locality of Taiguén (32°36′44″S 71°03′51″W), Talcahuano, Biobío Region, Chile, at an altitude of approximately 70 m a.s.l. Botanical identification and authentication was verified by Mr. Patricio Novoa, and a voucher specimen (GQ-0724) was deposited at the Natural Products and Organic Synthesis Laboratory of Universidad de Playa Ancha, Valparaíso, Chile. Once in the laboratory, the fresh leaves were selected for their uniformity and absence of damage, washed with distilled water to remove surface residues, and dried with absorbent paper. Subsequently, the material was divided into two batches for the corresponding analyses.

2.3 Preparation of Gomortega keule EO

The G. keule EO was obtained from 500 g of fresh leaves by hydrodistillation for 5 h, using a Clevenger-type apparatus. (Madrid et al., 2025). The resulting hydrolate was then purified by liquid-liquid partition in a separator funnel with three successive 10 mL portions of ethyl acetate Finally, the purified EO was stored at 4 °C pending further chemical and biological analysis.

2.4 Chromatographic analysis of volatile compounds

Two complementary analyses were performed to characterize the volatile profile: one on fresh leaves to capture the most volatile compounds and another on the extracted EO to determine its majority composition.

2.4.1 Analysis of fresh leaf volatiles by HS-SPME-GC/MS

2.5 g of fresh leaf fragments were placed in a headspace vial and equilibrated at 50 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fiber (50/30 µm DVB/Car-PDMS) was exposed to the headspace for 30 min to capture the volatile compounds. The fiber was desorbed in the gas chromatograph injector in splitless mode at 250 °C for 5 min.

2.4.2 EO analysis by GC/MS

The G. keule EO was diluted to 1% (v/v) in dichloromethane and homogenized by vortexing. Subsequently, 1 µL of the sample was injected for chromatographic analysis.

2.4.3 Chromatographic conditions, compound identification, and quantification

Both analyses were performed on a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 gas chromatograph coupled to an ISQ, LT mass spectrometer. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a Restek RTX-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 µm), using helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature of 40 °C for 1 min, followed by a ramp to 200 °C and held for 5 min, and a second ramp to 250 °C at 8 °C/min, holding for 5 min. The mass spectrometer operated in electron impact (EI) mode at 70 eV, performing a full scan over a mass range of 50–450 amu. The identification of volatile compounds was performed by comparing the obtained mass spectra with the NIST 2021 library, considering positive identifications for compounds with a Similarity Index (SI) greater than 800. Additionally, identities were confirmed by comparing the calculated Kovat Indices with those reported in the literature. Finally, the relative percentage composition of the EO components was calculated from the chromatographic peak areas using the area normalization method.

2.5 Cytotoxicity activity

2.5.1 Cells

Human cancer cell lines, MCF-7 (human mammary gland adenocarcinoma), HT-29 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma), PC-3 (human prostate adenocarcinoma) and normal human cell lines; CCD 841 CoN (colon epithelial), and MCF-10A (epithelial mammary gland) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). All tested cell lines were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and Ham’s F12 medium, containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were plated at a constant density to obtain identical experimental conditions in the different tests, thus to achieve a high accuracy of the measurements.

2.5.2 SRB bioassay

Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay was performed as already described (Silva et al., 2025). To assess cell viability, cells were seeded at 3 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were treated with the EO at concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 100 μg/mL for 72 h. Following treatment, cells were fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid, stained with 0.1% SRB, and then washed to remove unbound stain. The protein-bound stain was solubilized, and cell density was determined by measuring fluorescence at 540 nm. Daunorubicin and 5-fluorouracil were used as positive controls. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

2.5.3 Selectivity index

The selectivity index (SI) was determined by the ratio between the IC50 value of the cytotoxicity obtained for normal cells and the value found for a selected cancer cell line, as shown in Equation 1:

Where a SI > 3 was considered to belong to a selective sample (Moller et al., 2021).

2.5.4 Intracellular ROS generation

Intracellular ROS production was assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 16 × 104 cells/well in 500 µL of culture medium. The determination of ROS was performed following the methodology of Villena et al. (2021) using a fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). Briefly, cells were treated with the G. keule EO at concentrations of 5, 10, and 20 μg/mL for a total of 24 h. After treatment, cells were further incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, cells were harvested, rinsed, re-suspended in PBS and analyzed for 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence by flow cytometry (FacScalibur, Beckton Dickinson).

2.5.5 Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) were measured using the cationic fluorescent probe Rhodamine 123, as previously described (Villena et al., 2021). Briefly, exponentially growing cells were treated with G. keule EO as indicated in the figure legends. During the final 60 min of incubation, cells were labeled with 1 µM Rhodamine 123. After treatment, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, detached by trypsinization, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. The results are expressed as the percentage of cells retaining Rhodamine 123 fluorescence, which corresponds to the cell population with intact mitochondrial membrane potential.

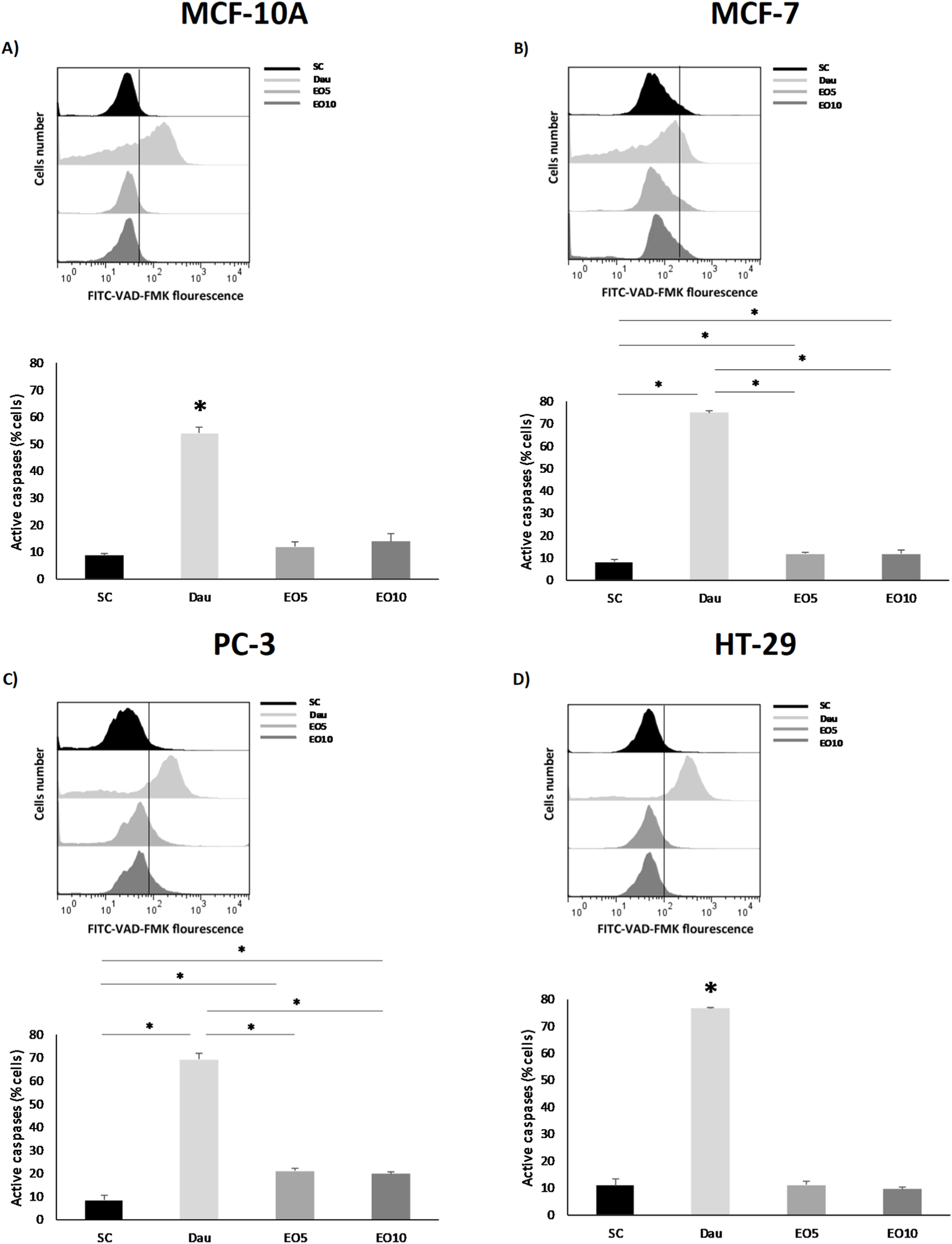

2.5.6 Measurement of caspase activity

Caspase activity, an indicator of apoptosis, was measured using the CaspACE™ FITC-VAD-FMK in situ marker (Promega, Santiago, Chile), as described previously (Jara-Gutiérrez et al., 2024). Cells were treated with the G. keule EO (5 and 10 μg/mL) for 48 h. During the final 20 min of the treatment, cells were incubated with the FITC-VAD-FMK reagent in darkness at room temperature. Following incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and pelleted by centrifugation (1500×g for 10 min). The resulting cell pellet was then resuspended in fresh PBS for immediate analysis by flow cytometry, with fluorescence detected using the FL3 filter. Results are expressed as the percentage of FITC-positive cells, representing the cell population undergoing apoptosis.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All in vitro assays were performed in three independent biological replicates, and each replicate was carried out in triplicate. The results are expressed as mean values ± Standard Deviation (SD). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Following the protocol described by Jara-Gutiérrez et al. (2024), and due to the non-parametric nature of the data, the results were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with a confidence level of 95% using STATISTICA 7.0 software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Profile of volatile compounds from fresh leaves (HS-SPME)

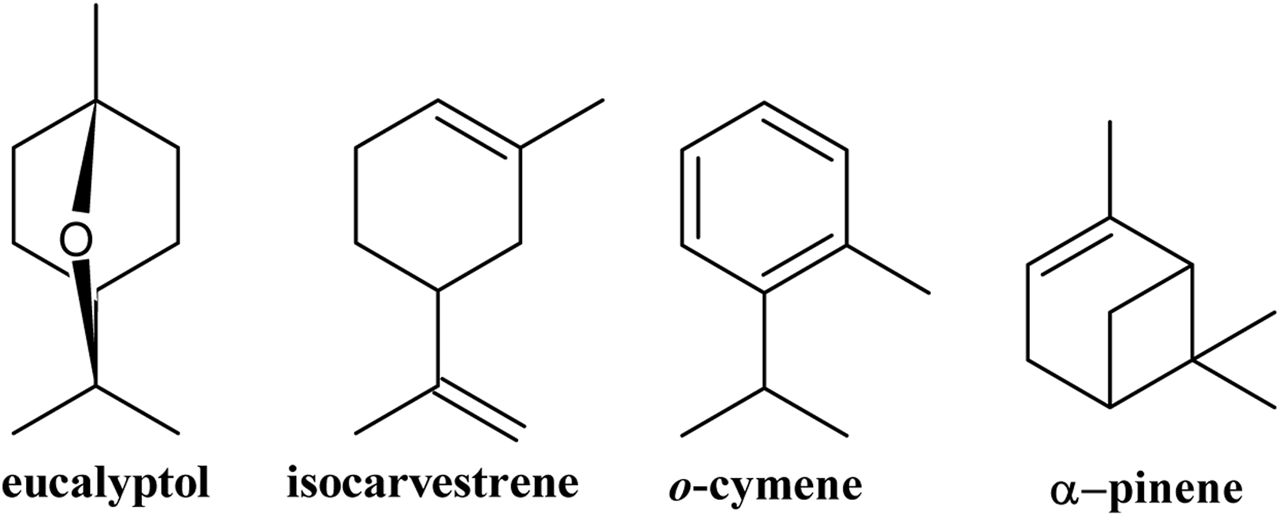

The HS-SPME analysis of fresh G. keule leaves identified a total of 10 compounds, which corresponded exclusively to hydrocarbon (60.84%) and oxygenated (35.71%) monoterpenes. Of these, the major components were eucalyptol (33.68%), o-cymene (25.28%), isocarvestrene (12.10%), and alpha-pinene (10.14%), as detailed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

TABLE 1

| N° | RT (min) | Components | % Areaa | RIa | RLb | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.09 | α-pinene | 10.14 | 930 | 930 | RL, MS, Co |

| 2 | 9.62 | Camphene | 0.50 | 941 | 941 | RL, MS, Co |

| 3 | 10.54 | Sabinene | 4.68 | 956 | 956 | RL, MS, Co |

| 4 | 10.64 | β-pinene | 7.18 | 970 | 970 | RL, MS, Co |

| 5 | 12.37 | o-cymene | 25.28 | 1014 | 1014 | RL, MS, Co |

| 6 | 12.50 | Isocarvestrene | 12.10 | 1026 | 1027 | RL, MS |

| 7 | 12.61 | Eucalyptol | 33.68 | 1033 | 1033 | RL, MS, Co |

| 8 | 14.58 | Dehydro-p-cymene | 0.96 | 1070 | 1070 | RL, MS, Co |

| 9 | 16.20 | Pinocarveol | 0.27 | 1133 | 1134 | RL, MS |

| 10 | 17.40 | 4-terpinenol | 1.76 | 1160 | 1160 | RL, MS, Co |

| Total identified | 96.55 | |||||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 35.71 | |||||

| Hydrocarbon monoterpenes | 60.84 |

SPME profile of the Gomortega keule leaves.

Experimental retention index for non-polar column.

Bibliographic retention index for non-polar column, MS, mass spectra.

FIGURE 1

Major volatile compounds present in the leaves of Gomortega keule.

This is the first time that volatiles emitted from the fresh leaves of G. keule have been reported, which contributes to the phytochemical knowledge of this ancestral tree.

3.2 Composition of Gomortega keule EO

The G. keule EO, extracted from its fresh leaves, was obtained with a yield of 1.22% (v/w) and is mainly composed of hydrocarbon diterpenes (54,77%), followed by hydrocarbon sesquiterpenes (18.81%), and oxygenated sesquiterpenes (9.95%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| N° | RT (min) | Components | % Areaa | RIa | RLb | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.54 | Viridiflorene | 1.24 | 1492 | 1493 | RL, MS |

| 2 | 7.81 | Not identified | 0.07 | |||

| 3 | 7.95 | Calamenene | 2.85 | 1516 | 1517 | RL, MS |

| 4 | 8.34 | α-calacorene | 7.69 | 1548 | 1548 | RL, MS |

| 5 | 8.53 | Diepicedrene-1-oxide | 0.33 | 1551 | 1551 | RL, MS |

| 6 | 8.61 | Not identified | 0.61 | |||

| 7 | 8.68 | Not identified | 0.89 | |||

| 8 | 9.00 | (−)-Spathulenol | 1.01 | 1574 | 1574 | RL, MS, Co |

| 9 | 9.14 | Globulol | 2.30 | 1580 | 1580 | RL, MS |

| 10 | 9.30 | Cubeban-11-ol | 0.99 | 1587 | 1588 | RL, MS |

| 11 | 9.33 | Not identified | 0.98 | |||

| 12 | 9.57 | Not identified | 0.28 | |||

| 13 | 9.78 | α-corocalene | 3.59 | 1605 | 1605 | RL, MS |

| 14 | 9.92 | Epicubenol | 0.86 | 1626 | 1627 | RL, MS |

| 15 | 10.17 | Not identified | 0.77 | |||

| 16 | 10.21 | Not identified | 0.43 | |||

| 17 | 10.47 | Not identified | 0.30 | |||

| 18 | 10.49 | Not identified | 0.39 | |||

| 19 | 10.75 | Not identified | 0.24 | |||

| 20 | 10.92 | Cadalene | 14.92 | 1643 | 1643 | RL, MS |

| 21 | 11.21 | Not identified | 0.13 | |||

| 22 | 11.58 | Not identified | 0.82 | |||

| 23 | 11.61 | Not identified | 0.79 | |||

| 24 | 12.25 | Not identified | 0.16 | |||

| 25 | 12.32 | Not identified | 0.25 | |||

| 26 | 12.59 | Not identified | 0.60 | |||

| 27 | 12.61 | Not identified | 0.36 | |||

| 28 | 13.01 | Not identified | 0.24 | |||

| 29 | 13.69 | Not identified | 0.44 | |||

| 30 | 13.72 | Not identified | 0.18 | |||

| 31 | 16.29 | Rimuene | 2.39 | 1884 | 1885 | RL, MS |

| 32 | 17.84 | Pimaradiene | 4.56 | 1930 | 1931 | RL, MS |

| 33 | 19.58 | Phyllocladene | 28.08 | 2012 | 2012 | RL, MS |

| 34 | 20.18 | Kaur-16-ene | 19.74 | 2040 | 2040 | RL, MS |

| 35 | 33.55 | Not identified | 0.42 | |||

| Total identified | 90.55 | |||||

| Total not identified | 9.45 | |||||

| Hydrocarbon sesquiterpenes | 30.29 | |||||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 5.49 | |||||

| Hydrocarbon diterpenes | 54.77 |

EO composition of Gomortega keule.

Experimental retention index for non-polar column.

Bibliographic retention index for non-polar column, MS, mass spectra.

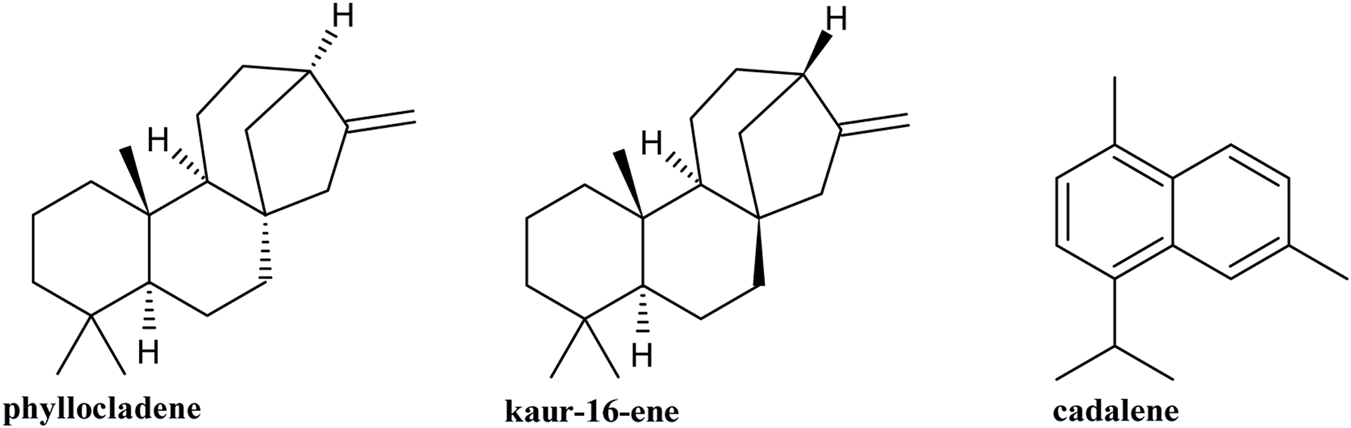

Fourteen compounds were identified in the G. keule EO, which corresponded to 90.55% of the total oil analyzed, and the main components were phyllocladene (28.08%), kaur-16-ene (19.74%), and cadalene (14.92%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Major compounds present in Gomortega keule EO.

The phytochemical analysis of G. keule leaves reveals a fascinating duality in its volatile compound profile, which is directly dependent on the analytical method used. The comparison between the profile obtained from fresh leaves by HS-SPME and the composition of the EO extracted by hydrodistillation shows drastic differences. Far from being contradictory, these results are complementary and offer a comprehensive view of the plant’s phytochemistry. HS-SPME analysis is a non-invasive and gentle technique that captures compounds emitted into the headspace at moderate temperatures. By its nature, this method is inherently biased towards more volatile, low-molecular-weight molecules (Souza-Silva, et al., 2015). Consequently, it is not surprising that the profile of the fresh leaves is exclusively dominated by monoterpenes (96.55%). This result represents the profile of volatiles that the leaf naturally emits into its environment, which could be related to ecological functions such as defense against herbivores or chemical communication. On the other hand, hydrodistillation is an exhaustive extractive method that uses high temperatures (100 °C) and steam entrainment over a prolonged period. This process forces the release of less volatile, higher-molecular-weight compounds stored in the plant’s glandular structures, such as sesquiterpenes and, notably, diterpenes (Siddiqui et al., 2024). The complete absence of the monoterpenes detected by SPME in the EO is a key finding, likely because these compounds, due to their extreme volatility and higher water solubility, were lost through evaporation or remained dissolved in the aqueous phase during the energetic distillation process (Masango, 2005). Thus, the two phytochemical profiles are not mutually exclusive: the HS-SPME analysis reveals the natural “aroma” of the fresh leaf, while the EO analysis shows the total content of stored semi-volatile and heavy metabolites. This distinction is fundamental. This study reveals significant differences in both the yield and the phytochemical profile of G. keule EO compared to previously published data, suggesting the existence of distinct chemotypes. Specifically, the obtained yield was 1.21% (v/w), an intermediate value between those reported by Becerra et al. (2010) (1.43%) and Montenegro et al. (2025) (0.99%). These variations in yield are expected and can be attributed to environmental and geographical factors that influence the production of secondary metabolites (Moghaddam et al., 2023; Dobhal et al., 2024; Jojić et al., 2024). However, the most notable difference lies in the chemical composition. Our EO is distinguished by a unique profile with a predominance of diterpenes (>50%), a very uncommon characteristic in EOs due to the high molecular weight and low volatility of these compounds (Wani et al., 2021). This profile contrasts sharply with the findings of Montenegro et al. (2025), whose oil was dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes (>60%), such as eucalyptol and 4-terpineol, with a minimal presence of diterpenes (<5%). Despite these differences, a point of structural connection exists: the study by Becerra et al. (2010) reported 20% kaurene, a diterpene that shares the same base skeleton as the kaur-16-ene identified in both our study and that of Montenegro et al. (2025). This combination of radically different phytochemical profiles with comparable extraction yields is the most compelling evidence for the existence of genetically determined chemotypes in G. keule (Martinelli et al., 2023).

3.3 Cytotoxic activity

The G. keule EO exhibited potent cytotoxic activity against all cancer cell lines tested, with the corresponding IC50 values presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Sample | Cell line | IC50 (µg/mL) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| G. Keule EO | MCF-7 | 3.97 ± 0.67 | 24.01a |

| PC-3 | 2.43 ± 0.73 | 20.30b | |

| HT-29 | 9.76 ± 1.03 | 5.06b | |

| CCD 841 CoN | 49.34 ± 0.33 | — | |

| MCF-10A | 95.32 ± 0.54 | — | |

| Daunorubicin | MCF-7 | 1.86 ± 0.05 | 1.15a |

| PC-3 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 9.14b | |

| HT-29 | 19.32 ± 0.50 | 0.62b | |

| CCD 841 CoN | 12.07 ± 0.40 | — | |

| MCF-10A | 2.13 ± 0.41 | — | |

| 5-FU | MCF-7 | 22.30 ± 0.20 | 0.15a |

| PC-3 | 16.42 ± 0.60 | 2.54b | |

| HT-29 | 8.90 ± 0.70 | 4.69b | |

| CCD 841 CoN | 41.71 ± 0.30 | — | |

| MCF-10A | 3.25 ± 0.23 | — |

Cytotoxicity (IC50) and selectivity index (SI) of Gomortega keule EO compared to standard drugs.

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). IC50: Concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50%. SI (Selectivity Index) = IC50 Normal Cell/IC50 Cancer Cell.

SI, calculated using MCF-10A, as the specific normal breast reference line.

SI, calculated using CCD, 841 CoN as the reference line.

The G. keule EO exhibited potent cytotoxic activity against breast (MCF-7), prostate (PC-3), and colon (HT-29) cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 3.97 ± 0.67, 2.43 ± 0.73, and 9.76 ± 1.03 μg/mL, respectively. All of these values are well below the 30 μg/mL threshold established by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) to consider an extract a promising candidate with cytotoxic potential (Canga et al., 2022). However, while potent cytotoxicity is a crucial first step, the true therapeutic potential of a compound lies in its ability to selectively target cancer cells while sparing healthy ones. This critical aspect is measured by the selectivity index (SI), where a value greater than 3 is considered indicative of meaningful selectivity (Mahmood et al., 2024).

To investigate this, we performed a tissue-specific comparison for breast cancer, evaluating the EO’s effect on the MCF-7 cancer line against its non-tumorigenic counterpart, the MCF-10A line. The outcome was remarkable, revealing an exceptional SI of 24.01, which confirms that the EO is profoundly more toxic to breast adenocarcinoma cells than to healthy epithelial cells from the same tissue. This favorable selectivity profile was not limited to breast cancer. The EO also showed a strong selective action against colon cancer (SI = 5.06) when comparing the HT-29 and CCD 841 CoN lines. For the PC-3 prostate cancer line, the CCD 841 CoN line served as the healthy control in the absence of a non-tumorigenic prostate line in our panel. Despite being a cross-tissue comparison, this test yielded a remarkably high SI of 20.30, further reinforcing the EO’s promising safety profile and its specific action against malignant cells.

To properly contextualize these findings, the EO’s performance was benchmarked against standard chemotherapeutic agents (Table 3). The G. keule EO exhibited an exceptional SI of 24.01 for breast cancer cells when compared to the tissue-specific normal line MCF-10A. In sharp contrast, the standard drugs showed significantly lower selectivity in this specific model. Daunorubicin presented an SI of 1.15, while 5-FU showed an SI of 0.15 against the MCF-10A line, due to their high toxicity towards healthy breast epithelial cells (IC50 values of 2.13 and 3.25 μg/mL, respectively). This remarkable difference highlights the G. keule EO as a promising candidate with a potentially superior safety profile and a wider therapeutic window compared to these conventional agents in this in vitro model.

It is important to acknowledge a specific limitation in our selectivity analysis regarding prostate cancer. The Selectivity Index (SI) for the PC-3 cell line was calculated using the non-tumorigenic colon epithelial line (CCD 841 CoN) as a reference, due to the unavailability of a specific normal prostate cell line in our panel. While this comparison provides a valid estimate of the oil’s general toxicity towards healthy epithelial cells, it constitutes a cross-tissue comparison. Therefore, the reported selectivity for prostate cancer should be interpreted with caution, as a tissue-specific model (e.g., using RWPE-1 or PNT cell lines) would provide a more precise assessment of the therapeutic window for this specific cancer type (Bello et al., 1997; Rumsby et al., 2011).

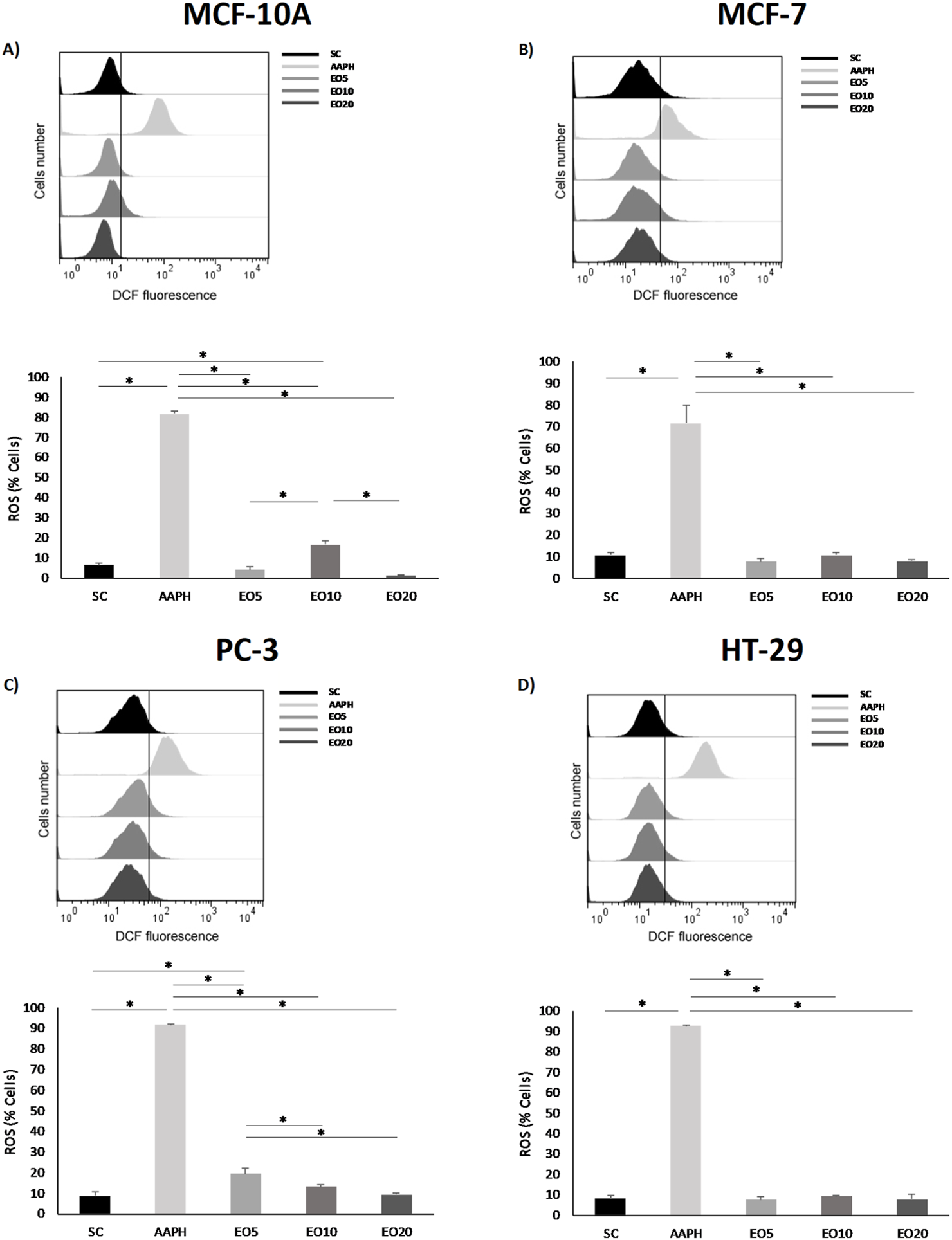

Building on these compelling activity and selectivity results, we sought to understand the underlying mechanism of action. A central finding is that the cytotoxic activity of the G. keule EO is directly associated with the induction of intracellular oxidative stress. To evaluate this, we utilized AAPH (2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride) as a positive control, given its well-established role as a peroxyl radical generator that mimics oxidative stress conditions. As shown in Figure 3, the treatment with G. keule EO induced a differential response in intracellular ROS levels. A significant and concentration-dependent increase was clearly observed in PC-3 cells (Figure 3C) compared to the solvent control (CS). In contrast, in MCF-7 and HT-29 cells (Figures 3B,D), ROS levels measured at 24 h remained comparable to the solvent control. This suggests that while oxidative stress appears to be a primary driver of cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells, the mechanism in breast and colon cancer cells may involve different kinetic profiles or alternative upstream triggers for the observed mitochondrial depolarization. To validate this, the MCF-10A cell line was strategically chosen for comparative flow cytometry studies precisely because of its high resistance (high IC50 value). This resilience made it the ideal negative control, allowing us to analyze cellular mechanisms like ROS production at EO concentrations that are lethal to cancer cells. This finding, which confirms that the pro-oxidant effect is a specific mechanism, aligns with a growing body of literature on the action of EOs. For instance, Kong et al. (2022) also documented that various EOs can alter the cellular redox balance to induce biological damage in target cells.

FIGURE 3

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was measured in nontumor breast cell line [(A) = MCF-10A] and cancer cell lines [(B) = MCF-7, (C) = PC-3 and (D) = HT-29] after being exposed for 24 h to three different concentrations of Gomortega keule EO. Treatments: EO5 = 5 μg/mL, EO10 = 10 μg/mL, and EO20 = 20 μg/mL. For ROS production control, 10 µM AAPH (AAPH) was used as a positive control and 0.1% ethanol as a solvent control (SC). (A–D) Show the mean percentage of cells with ROS production. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. *p < 0.05 compared to the solvent control (SC).

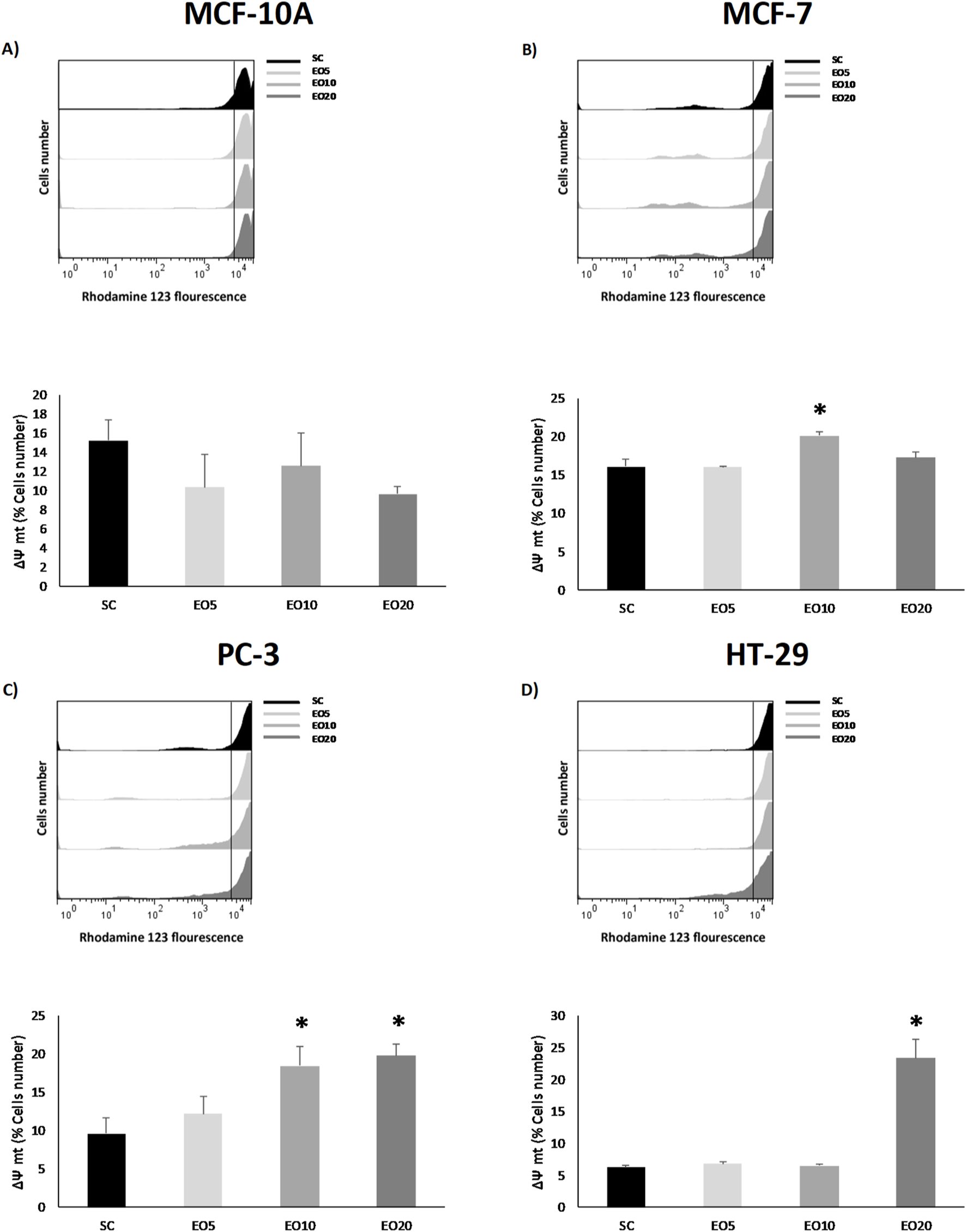

This oxidative stress often leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, a key event in apoptosis. In accordance with this, our results demonstrate a selective loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) only in the cancer cell lines (MCF-7, PC-3, and HT-29), as evidenced in Figure 4. This finding aligns perfectly with recent studies, such as that on Cinnamomum zeylanicum oil, which was also shown to inhibit melanoma cell proliferation by increasing ROS and causing mitochondrial membrane depolarization selectively in cancer cells, but not in normal human cells (PBMCs) (Cappelli et al., 2023). The loss of ΔΨm is a point-of-no-return in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, as it leads to the release of pro-apoptotic factors from the mitochondria into the cytosol (Blowman et al., 2018).

FIGURE 4

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was analyzed in nontumor [(A) = MCF-10A] and cancer cell lines [(B) = MCF-7, (C) = PC-3 and (D) = HT-29] after being exposed for 48 h to three different concentrations of Gomortega keule EO. Treatments: EO5 = 5 μg/mL, EO10 = 10 μg/mL, and EO20 = 20 μg/mL 0.1% ethanol was used as solvent control (SC). (A–D) show the mean percentage of cells retaining ΔΨm. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. *p < 0.05 compared to the solvent control (SC).

This release of mitochondrial factors activates the caspase cascade, which involves the executioner proteases of apoptosis. Indeed, our analysis confirmed the activation of caspases in the breast (MCF-7) and prostate (PC-3) cancer cell lines following treatment with EO (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Caspase activity was analyzed in nontumor [(A) = MCF-10A] and cancer cell lines [(B) = MCF-7, (C) = PC-3 and (D) = HT-29] after being exposed for 48 h to two different concentrations of Gomortega keule EO. Treatments: EO5 = 5 μg/mL and EO10 = 10 μg/mL. For caspase activation control, 1 µM daunorubicin (Dau) was used as a positive control and 0.1% ethanol as solvent control (SC). (A–D) Show the mean percentage of cells with active caspases. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. *p < 0.05 compared to the solvent control (SC).

This result is consistent with studies on other EOs, such as that of Origanum majorana, which also induces apoptosis in lung and epidermoid carcinoma cells through the activation of caspase-3/7 (Gökhan, 2022). It is interesting to note that, although the colon (HT-29) cell line also showed a loss of ΔΨm, significant caspase activation was not detected under the same conditions. This could suggest that, in this cell line, the oil induces a different type of cell death (such as necrosis or a caspase-independent apoptotic pathway) or that caspase activation occurs at a later time point than the one analyzed. Taken together, these results delineate a clear mechanism of action for G. keule EO: the induction of ROS leads to mitochondrial damage (loss of ΔΨm), which in turn triggers caspase activation and apoptotic cell death, at least in breast and prostate cancer cells. This apoptotic pathway is a hallmark of the cytotoxic properties reported for many EOs and their terpenoid components. For instance, frankincense extracts have also been shown to induce cancer cell-specific cytotoxicity by activating caspases and inducing PARP cleavage (Blowman et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2022). Crucially, the selectivity of these effects towards tumor cells further reinforces the therapeutic potential of this EO as a source of natural cytotoxic compounds. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that while the high abundance of diterpenes suggests they play a major role in the observed cytotoxicity, the G. keule EO is a complex mixture. High diterpene contents, although uncommon due to their low volatility (Ben Miri, 2025), have been reported in other species such as Euphorbia mauritanica, which also shares the presence of kaur-16-ene (Essa et al., 2021). Current literature suggests that the biological activity of EOs often results from the synergistic interaction of their major and minor constituents, producing a combined effect greater than the sum of individual compounds (Essa et al., 2021; Ben Miri, 2025). Therefore, the potent and selective activity reported here is attributed to the G. keule EO as a whole.

4 Conclusion

The present study characterizes a unique chemotype of Gomortega keule EO, distinguished by a high prevalence of diterpenes such as phyllocladene and kaur-16-ene, which differs notably from previous reports. This EO demonstrated potent cytotoxic activity against breast, prostate, and colon cancer cell lines. While the dominant diterpenes likely contribute to this effect, the observed activity is attributed to the EO as a complex mixture, suggesting potential synergistic interactions among its constituents. Mechanistically, the cytotoxic effect is driven by the selective induction of oxidative stress (ROS) in tumor cells, leading to mitochondrial membrane depolarization and subsequent caspase-dependent apoptosis. Crucially, our comparative analysis revealed that the G. keule EO possesses exceptional selectivity towards breast cancer cells (SI > 24) when compared to normal mammary epithelial cells (MCF-10A). This selectivity profile significantly outperforms that of standard chemotherapeutic agents like daunorubicin and 5-fluorouracil in this specific model. These findings validate the ethnopharmacological relevance of G. keule and highlight its potential as a promising source of bioactive compounds with selective cytotoxic properties.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

AMa: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. VS: Writing – original draft. AR: Writing – original draft. AMo: Writing – original draft. ES: Writing – original draft. JV: Writing – original draft. CJ-G: Writing – original draft. IM: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors thank FONDECYT Regular, Grant No. 1230311 from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) of Chile.

Acknowledgments

To the Beca Doctorado Nacional N◦ 21240311 from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) of Chile, Millennium Nucleus Bioproducts, Genomics and Environmental Microbiology (BioGEM), ANID-Milenio-NCN2023_054. The authors thank the Dirección General de Investigación de la Universidadde Playa Ancha for their support in the hiring of the technicians VS Pedreros for the“Apoyos tecnicos para laboratorios y grupos de investigacion UPLA 2025 (SOS Technician).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Becerra J. Bittner M. Hernández V. Brintrup C. Becerra J. Silva M. (2010). Actividad de aceites esenciales de Canelo, Queule, Bailahuén y Culén frente a hongos fitopatógenos. BLACPMA9 (3), 212–215.

2

Bello D. Webber M. M. Kleinman H. K. Wartinger D. D. Rhim J. S. (1997). Androgen responsive adult human prostatic epithelial cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus 18. Carcinogenesis18 (6), 1215–1223. 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1215

3

Ben Miri Y. (2025). Essential oils: Chemical composition and diverse biological activities: a comprehensive review. Nat. Prod. Comm.20 (1), 1–29. 10.1177/1934578X241311790

4

Blowman K. Magalhães M. Lemos M. F. L. Cabral C. Pires I. M. (2018). Anticancer properties of essential oils and other natural products. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2018, 3149362. 10.1155/2018/3149362

5

Bray F. Laversanne M. Sung H. Ferlay J. Siegel R. L. Soerjomataram I. et al (2024). Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74 (3), 229–263. 10.3322/caac.21834

6

Canga I. Vita P. Oliveira A. I. Castro M. Á. Pinho C. (2022). In vitro cytotoxic activity of African plants: a review. Molecules27 (15), 4989. 10.3390/molecules27154989

7

Cappelli G. Giovannini D. Vilardo L. Basso A. Iannetti I. Massa M. et al (2023). Cinnamomum zeylanicum blume essential oil inhibits metastatic melanoma cell proliferation by triggering an incomplete tumour cell stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (6), 5698.10.3390/ijms24065698

8

Crowley E. (2020). “Relatos sobre Saberes del Queule y el Zorro de Darwin,” in Chile: organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Concepcion, Chile: FAO y Ministerio del Medio Ambiente MMA.

9

Dobhal P. Purohit V. K. Chandra S. Rawat S. Prasad P. Bhandari U. et al (2024). Climate-induced changes in essential oil production and terpene composition in alpine aromatic plants. Plant Stress12, 100445. 10.1016/j.stress.2024.100445

10

Duluklu B. Şenol Çelik S. (2019). Effects of lavender essential oil for colorectal cancer patients with permanent colostomy on elimination of odor, quality of life, and ostomy adjustment: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs.42, 90–96. 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.08.001

11

Essa A. F. El-Hawary S. S. Abd-El Gawad A. M. Kubacy T. M. El-Khrisy E. E. D. A. Elshamy A. I. et al (2021). Prevalence of diterpenes in essential oil of Euphorbia mauritanica L.: detailed chemical profile, antioxidant, cytotoxic and phytotoxic activities. Chem. Biodivers.18 (7), e2100238. 10.1002/cbdv.202100238

12

Ferlay J. Steliarova-Foucher E. Lortet-Tieulent J. Rosso S. Coebergh J. W. (2012). Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer49 (6), 1374–1403. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027

13

Fernandez-Muñoz K. V. Sánchez-Barrera C. Á. Meraz-Ríos M. Reyes J. L. Pérez-Yépez E. A. Ortiz-Melo M. T. et al (2025). Natural alternatives in the treatment of colorectal cancer: a mechanisms perspective. Biomolecules15 (3), 326. 10.3390/biom15030326

14

Garzoli S. Alarcón-Zapata P. Seitimova G. Alarcón-Zapata B. Martorell M. (2022). Natural essential oils as a new therapeutic tool in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int.407. 10.1186/s12935-022-02806-5

15

Gökhan A. (2022). Evaluation of cytotoxic, membrane damaging and apoptotic effects of Origanum majorana essential oil on lung cancer and epidermoid carcinoma cells. Cyprus J. Med. Sci.7 (2), 201–206. 10.4274/cjms.2021.2021-142

16

Jamali T. Kavoosi G. Ardestani S. K. (2020). In-vitro and in-vivo anti-breast cancer activity of OEO (Oliveria decumbens vent essential oil) through promoting the apoptosis and immunomodulatory effects. J. Ethnopharmacol.248, 112313. 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112313

17

Jara-Gutiérrez C. Mercado L. Paz-Araos M. Howard C. Parraga M. Escobar C. et al (2024). Oxidative stress promotes cytotoxicity in human cancer cell lines exposed to escallonia spp. extracts. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.24 (1), 38. 10.1186/s12906-024-04341-4

18

Jojić A. A. Liga S. Uţu D. Ruse G. Suciu L. Motoc A. et al (2024). Beyond essential oils: diterpenes, lignans, and biflavonoids from Juniperus communis L. as a source of multi-target lead compounds. Plants13 (22), 3233. 10.3390/plants13223233

19

Klempner S. J. Bubley G. (2012). Complementary and alternative medicines in prostate cancer: from bench to bedside?Oncologist17 (6), 830–837. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0094

20

Kong A. S. Maran S. Yap P. S. Lim S. E. Yang S. K. Cheng W. H. et al (2022). Anti- and pro-oxidant properties of essential oils against antimicrobial resistance. Antioxidants11 (9), 1819. 10.3390/antiox11091819

21

Madrid A. Avola R. Graziano A. C. E. Cardile V. Russo A. (2025). Fabiana imbricata ruiz & pav. (solanaceae) essential oil analysis in prostate cancer cells: relevance of reactive oxygen species in proapoptotic activity. J. Ethnopharmacol.352, 120162. 10.1016/j.jep.2025.120162

22

Mahmood M. A. Abd A. H. Kadhim E. J. (2024). Assessing the cytotoxicity of phenolic and terpene fractions extracted from Iraqi Prunus arabica against AMJ13 and SK-GT-4 human cancer cell lines. F1000Res12, 433. 10.12688/f1000research.131336.3

23

Manosroi J. Dhumtanom P. Manosroi A. (2006). Anti-proliferative activity of essential oil extracted from Thai medicinal plants on KB and P388 cell lines. Cancer Lett.235 (1), 114–120. 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.021

24

Martinelli T. Fulvio F. Pietrella M. Bassolino L. Paris R. (2023). Silybum marianum chemotype differentiation is genetically determined by factors involved in silydianin biosynthesis. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants.32, 100442. 10.1016/j.jarmap.2022.100442

25

Masango P. (2005). Cleaner production of essential oils by steam distillation. J. Clean. Prod.13 (8), 833–839. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.02.039

26

Moghaddam H. H. Jafari A. A. Sefidkon F. Jari S. K. (2023). Influence of climatic factors on essential oil content and composition of 20 populations of Nepeta binaludensis jamzad from Iran. Appl. Biol. Chem.66 (1), 2. 10.1186/s13765-022-00750-6

27

Moller A. C. Parra C. Said B. Werner E. Flores S. Villena J. et al (2021). Antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity of essential oil and main components from leaves of aloysia Polystachya harvested in central Chile. Molecules26 (1), 131. 10.3390/molecules26010131

28

Montenegro I. Fuentes B. Silva V. Valdés F. Werner E. Santander R. et al (2025). Nanoemulsion of Gomortega keule essential oil: characterization, chemical composition, and anti-yeast activity against candida spp. Pharmaceutics17 (6), 755. 10.3390/pharmaceutics17060755

29

Muñoz-Concha D. Garrido-Werner A. (2011). Ethnobotany of Gomortega keule, an endemic and endangered Chilean tree. N. Z. J. Bot.49 (4), 509–513. 10.1080/0028825X.2011.614262

30

Mustapa M. A. Guswenrivo I. Zuhrotun A. Ikram N. K. K. Muchtaridi M. (2022). Anti-breast cancer activity of essential oil: a systematic review. Appl. Sci.12 (24), 12738. 10.3390/app122412738

31

Palshof F. K. Mørch L. S. Køster B. Engholm G. Storm H. H. Andersson T. M. L. et al (2024). Non-preventable cases of breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer in 2050 in an elimination scenario of modifiable risk factors. Sci. Rep.14 (1), 8577. 10.1038/s41598-024-59314-x

32

Patterson R. E. Neuhouser M. L. Hedderson M. M. Schwartz S. M. Standish L. J. Bowen D. J. et al (2002). Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, Colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J. Altern. Complement. Med.8 (4), 477–485. 10.1089/107555302760253676

33

Rumsby M. Schmitt J. Sharrard M. Rodrigues G. Stower M. Maitland N. (2011). Human prostate cell lines from normal and tumourigenic epithelia differ in the pattern and control of choline lipid headgroups released into the medium on stimulation of protein kinase C. Br. J. Cancer104 (4), 673–684. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606077

34

Sharma M. Grewal K. Jandrotia R. Batish D. R. Singh H. P. Kohli R. K. (2022). Essential oils as anticancer agents: potential role in malignancies, drug delivery mechanisms, and immune system enhancement. Biomed. Pharmacother.146, 112514. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112514

35

Siddiqui T. Khan M. U. Sharma V. Gupta K. (2024). Terpenoids in essential oils: Chemistry, classification, and potential impact on human health and industry. Phytomed. Plus4 (2), 100549. 10.1016/j.phyplu.2024.100549

36

Silva V. Muñoz E. Ferreira C. Russo A. Villena J. Montenegro I. et al (2025). In vitro and in silico cytotoxic activity of isocordoin from Adesmia balsamica against cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26 (5), 2238. 10.3390/ijms26052238

37

Simirgiotis M. J. Ramirez J. E. Schmeda Hirschmann G. Kennelly E. J. (2013). Bioactive coumarins and HPLC-PDA-ESI-ToF-MS metabolic profiling of edible queule fruits (Gomortega keule), an endangered endemic Chilean species. Food Res. Int.54 (1), 532–543. 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.07.022

38

Souza-Silva É. A. Jiang R. Rodríguez-Lafuente A. Gionfriddo E. Pawliszyn J. (2015). A critical review of the state of the art of solid-phase microextraction of complex matrices I. Environmental analysis. TRAC71, 224–235. 10.1016/j.trac.2015.04.016

39

Torri M. C. (2010). Medicinal plants used in mapuche traditional medicine in Araucanía, Chile: linking sociocultural and religious values with local heath practices. Complement. Health Pract. Rev.15 (3), 132–148. 10.1177/1533210110391077

40

Villena J. Montenegro I. Said B. Werner E. Flores S. Madrid A. (2021). Ultrasound assisted synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of known 2′, 4′-dihydroxychalcone derivatives against cancer cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol.148, 111969. 10.1016/j.fct.2021.111969

41

Wani A. R. Yadav K. Khursheed A. Rather M. A. (2021). An updated and comprehensive review of the antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents with special focus on their mechanism of action against various influenza and coronaviruses. Microb. Pathog.152, 104620. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104620

42

World Health Organization (2023). Cáncer colorrectal. Available online at: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer (Accessed October 1, 2025).

43

Zahed H. Feng X. Sheikh M. Bray F. Ferlay J. Ginsburg O. et al (2024). Age at diagnosis for lung, Colon, breast and prostate cancers: an international comparative study. Int. J. Cancer154 (1), 28–40. 10.1002/ijc.34671

Summary

Keywords

apoptosis, cytotoxic activity, diterpenes, essential oil, Gomortega keule

Citation

Madrid A, Silva V, Russo A, Moller AC, Sánchez E, Villena J, Jara-Gutiérrez C and Montenegro I (2025) Selective cytotoxicity of Gomortega keule essential oil through a ROS-mediated pro-apoptotic mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1722619. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1722619

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

27 November 2025

Accepted

27 November 2025

Published

08 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Jie Liu, Zunyi Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Hianara Aracelly Bustamante, Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile

Enrique Werner, Universidad del Bio-Bio - Sede Chillan, Chile

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Madrid, Silva, Russo, Moller, Sánchez, Villena, Jara-Gutiérrez and Montenegro.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alejandro Madrid, alejandro.madrid@upla.cl; Iván Montenegro, ivan.montenegro@uv.cl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.