Abstract

Introduction:

Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) can enhance graft-versus-leukemia (GvL) effects following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the optimal integration of azacitidine (Aza) with DLI in children remains uncertain.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed 16 pediatric AML patients (≤18 years) treated at Fundeni Clinical Institute between 2016 and 2024 who received DLI in combination with azacitidine (75 mg/m2/day for 7 days every 4 weeks) after HSCT. DLI was administered prophylactically or preemptively based on mixed donor chimerism (MDC), measurable residual disease (MRD) positivity, or high-risk cytogenetics, or therapeutically for post-transplant relapse, with or without chemotherapy. Outcomes assessed included overall survival (OS), donor chimerism, relapse rate, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Results:

After a median follow-up of 46.5 months, five patients received prophylactic/preemptive DLI and eleven received therapeutic DLI (seven with chemotherapy, four without). All patients in the prophylactic/preemptive group achieved full donor chimerism and MRD negativity, with an OS of 80% at 2.7 years. In the therapeutic group, median OS was 23.8 months with chemotherapy and 13.8 months without. OS differences between groups were not statistically significant (p = 0.384). Acute GVHD occurred in two patients (12.5%) in the therapeutic + chemotherapy subgroup; no chronic GVHD or non-relapse mortality was observed.

Conclusion:

Azacitidine combined with DLI is feasible and safe in pediatric AML after HSCT, particularly when applied prophylactically or preemptively to restore donor chimerism or eradicate MRD. Therapeutic use in overt relapse remains challenging and provides limited benefit. Prospective multicenter studies are needed to define optimal timing, dosing, and combination strategies for integrating azacitidine with DLI in this high-risk pediatric population.

1 Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in children is a rare but aggressive hematologic malignancy, representing approximately 15%–20% of childhood leukemias. Despite advances in chemotherapy and supportive care, long-term survival remains suboptimal for high-risk or relapsed disease (Egan and Tasian, 2023; Dholaria and Savani, 2020; Chorão et al., 2023). Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) offers the only curative strategy for many patients, providing both a source of healthy hematopoiesis and the critical graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect mediated by donor immune cells (Koreth et al., 2009; Bejanyan et al., 2015; Accorsi Buttini et al., 2024).

However, relapse remains the leading cause of treatment failure after HSCT in pediatric AML, with reported rates ranging from 20% to 40% (Bader et al., 2024). Relapse post-HSCT carries a dismal prognosis, emphasizing the need for effective strategies to prevent and treat recurrence (Zuanelli Brambilla et al., 2020; Castagna et al., 2016; Cluzeau et al., 2023).

Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) is well characterized in adult AML, but pediatric-specific data remain sparse, particularly regarding its integration with hypomethylating agents such as azacitidine. In adults, DLI is used preemptively for mixed donor chimerism (MDC) or measurable residual disease (MRD) positivity, prophylactically in high-risk patients, or therapeutically for relapse (Kolb et al., 1990; van Rhee et al., 1997; Rettinger et al., 2011; Pulsipher et al., 2015). Azacitidine has immunomodulatory properties, promoting the expansion and functional restoration of regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby enhancing the GVL effect while mitigating graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) risk (Sockel et al., 2011; ClinicalTrials.gov, 2025; Loke et al., 2021). Recent pediatric reports suggest feasibility, but optimal timing, dosing, and integration strategies remain undefined (Peters et al., 2024; Craddock et al., 2016; Admiraal et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2024; Hussain et al., 2021; Bejanyan et al., 2015).

Against this backdrop, we conducted a retrospective analysis to evaluate the outcomes of pediatric patients with AML undergoing DLI combined with azacitidine after HSCT at our center.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and patients

Single-center retrospective study at Fundeni Clinical Institute, including pediatric patients (≤18 years) with AML undergoing allo-HSCT followed by DLI and Aza (2016–2024). MDC was defined as 5%–95% donor cells by short tandem repeats (STR) analysis, per EBMT guidelines (Bader et al., 2024), while measurable residual disease (MRD) was considered positive at levels above 0.01% in bone marrow, by flow cytometry. All patients were GVHD-free and off immunosuppression at DLI.

2.2 Transplant procedures

Donor types included matched sibling donors (MSD), matched unrelated donors (MUD), and haploidentical. Conditioning regimens were myeloablative conditioning (MAC) or reduce intensity conditioning (RIC). Grafts were predominantly peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC).

2.3 DLI procedures

Indications for DLI included prophylactic or preemptive use—such as MRD positivity, MDC, or high-risk cytogenetics—and therapeutic use for disease relapse. All patients received azacitidine at a dose of 75 mg/m2/day for 7 consecutive days every 4 weeks prior to DLI. The administered DLI doses were 1 × 105/kg, 1 × 105/kg, 5 × 105/kg, 1 × 106/kg, and 1 × 107/kg CD3+ cells. MRD and chimerism monitoring was performed at 1 month and subsequently at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after transplantation, as well as whenever clinically indicated. MRD and chimerism were assessed before the first DLI dose; thereafter, chimerism was evaluated prior to each DLI, while MRD was monitored every 3 months. Relapsed patients who received therapeutic DLI in combination with chemotherapy were treated using either the FLAG, GLAG-M or DCAG protocols, along with intrathecal chemotherapy and, in some cases, radiotherapy (e.g., following orchiectomy). Patients who received therapeutic DLI without preceding chemotherapy were those experiencing either very early relapse or such extensive relapse after HSCT that administering chemotherapy would have posed a life-threatening risk.

2.4 Outcome and follow-up

Primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and complete donor chimerism. Secondary outcomes: GVHD and relapse. Follow-up was measured from HSCT.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were assessed for normality (Shapiro–Wilk). Normally distributed data were analyzed with ANOVA; non-normally distributed data with Kruskal–Wallis. Survival analysis used Kaplan–Meier/log-rank tests. Hazard ratios were estimated by Cox regression. Correlations were assessed by Spearman rank. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

2.6 Results ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institute (protocol code 36105, 29.08.2025). Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians for participation and publication of de-identified data.

3 Results

3.1 Patients’ characteristics

Sixteen patients (11M:5F), median age 10 years. Donor types: 10 MUD, 3 MSD, 3 haploidentical. Grafts: 15 PBSC, 1 BM. Twelve patients received MAC, 4 RIC for haploidentical HSCT. Median follow-up: 46.5 months (range 5–84) (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Parameter | All patients n = 16 |

Prophylactic/preemptive DLI n = 5 | Therapeutic DLI with chemotherapy n = 7 | Therapeutic DLI without chemotherapy n = 4 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – mean ± SD, years | 9.19 ± 5.47 | 7.00 ± 6.33 | 8.57 ± 5.86 | 11.25 ± 4.50 | 0.713 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (36.4%) | 4 (36.4%) | 0.296 |

| FAB classification | |||||

| M0-2 | 7 | 2 (28.6%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.954 |

| M4-5 | 9 | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| MLL status | |||||

| Positive | 4 | 3 (75.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.081 |

| Negative | 12 | 2 (16.7%) | 6 (50.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Donor type | 0.201 | ||||

| MSD | 3 | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| MUD | 7 | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (28.6%) | 2 (28.6%) | |

| MMUD | 3 | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| HAPLO | 3 | 0 (0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.218 | ||||

| MAC | 12 | 5 (41.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| RIC | 4 | 0 (0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | |

| Time from HSCT to DLI – median (IQR), months | 7.82 (10.54) | 8.28 (7.31) | 7.36 (26.63) | 7.66 (16.84) | 0.663 |

| No. of DLI – median (IQR) | 4 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (1) | 4 (3) | 0.356 |

| Pre-DLI chimerism– median (IQR) | 87.5% (34%) | 91% (24%) | 100% (27%) | 61% (54.75%) | 0.062 |

| Post-DLI chimerism– median (IQR) | 100% (7.75%) | 100% (6%) | 100% (7%) | 68% (74.50%) | 0.231 |

| Post-DLI acute GVHD | |||||

| No | 14 | 5 (37.5%) | 5 (37.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.230 |

| Yes | 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

Patients’ characteristics.

Abbreviations: DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; FAB, French-American-British; HAPLO, haploidentical donor; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MAC, myeloablative conditioning regimen; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MSD, matched sibling donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning regimen; SD, standard-deviation.

3.2 Prophylactic/preemptive DLI

Five patients (3M/2F) received prophylactic/preemptive DLI. Median time to first DLI was 280 days. All achieved 100% donor chimerism and MRD negativity. OS at 2.7-years follow-up was 80%.

3.3 Therapeutic DLI (n = 11)

7 received chemotherapy prior to DLI, 4 did not. Median OS: 23.8 months (with chemotherapy) vs. 13.8 months (without). Two cases of acute GVHD (skin grade II, later progressing to gut/liver grade IV) occurred only in the chemotherapy group. No chronic GVHD or non-relapse mortality observed.

3.4 Statistical analyses

We performed both univariate and multivariate analyses to identify variables of potential statistical significance within our patient cohort.

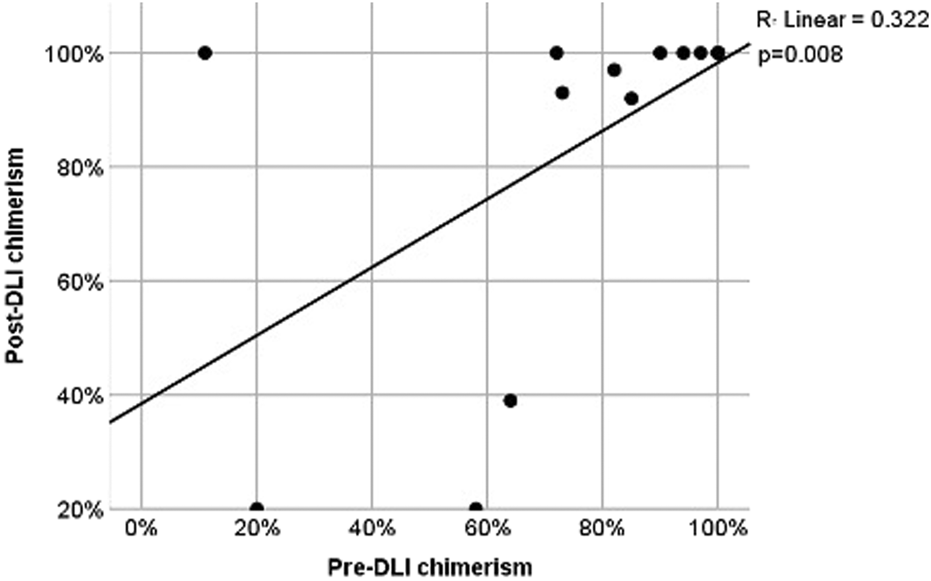

3.5 Pre - and post-DLI chimerism

The correlation between chimerism levels before and after DLI was positive and moderate-to-strong (r = 0.640). However, this correlation may reflect both baseline variability and treatment-related changes, and therefore should be interpreted with caution. This association was statistically significant (p = 0.008), indicating that higher pre-DLI chimerism values tended to be associated with higher post-DLI chimerism values (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Scatter plot for pre- and post-DLI chimerism. Comparisons of OS and PFS were performed among three groups according to DLI indications: prophylactic/preemptive, therapeutic without chemotherapy, and therapeutic with chemotherapy.

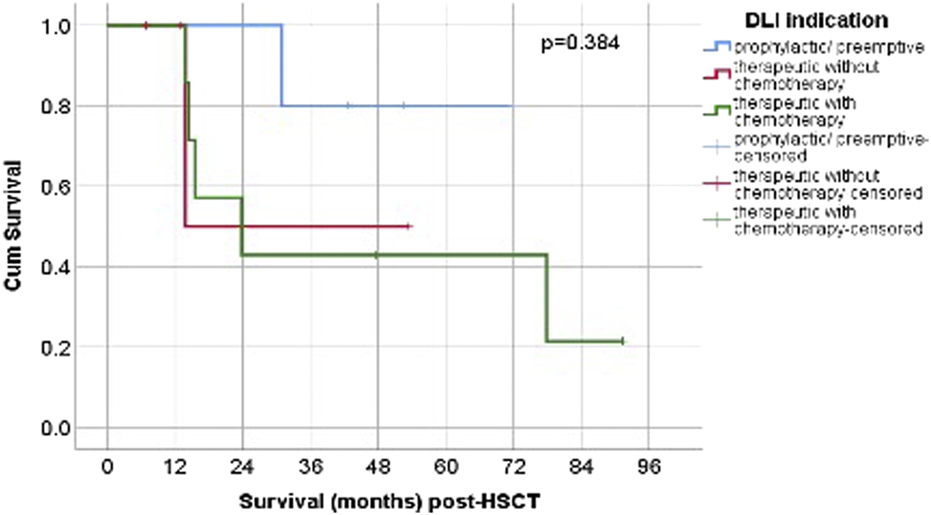

The Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 2) show that patients in the prophylactic/preemptive group maintained higher cumulative survival probabilities over time compared to the therapeutic groups, particularly after the first 20 months post-HCT.

FIGURE 2

Post-HSCT OS according to DLI. Abbreviations: p/p = prophylactic/preemptive; n = number; chemo- = without chemotherapy, chemo+ = with chemotherapy.

The log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test revealed no statistically significant difference in survival distributions among the three groups (p = 0.384). While the graphical trends suggest clinical differences in long-term outcomes, these were not statistically confirmed, possibly due to limited sample size, variability in follow-up, and the proportion of censored cases.

The median survival time after DLI for the therapeutic without chemotherapy group, was 13.81 months (95% CI could not be estimated, 3/4 censored), and for the therapeutic with chemotherapy group, the median was 23.84 months (95% CI 2.49-45.18, 2/7 censored). The median OS for prophylactic/preemptive was not reached during follow-up.

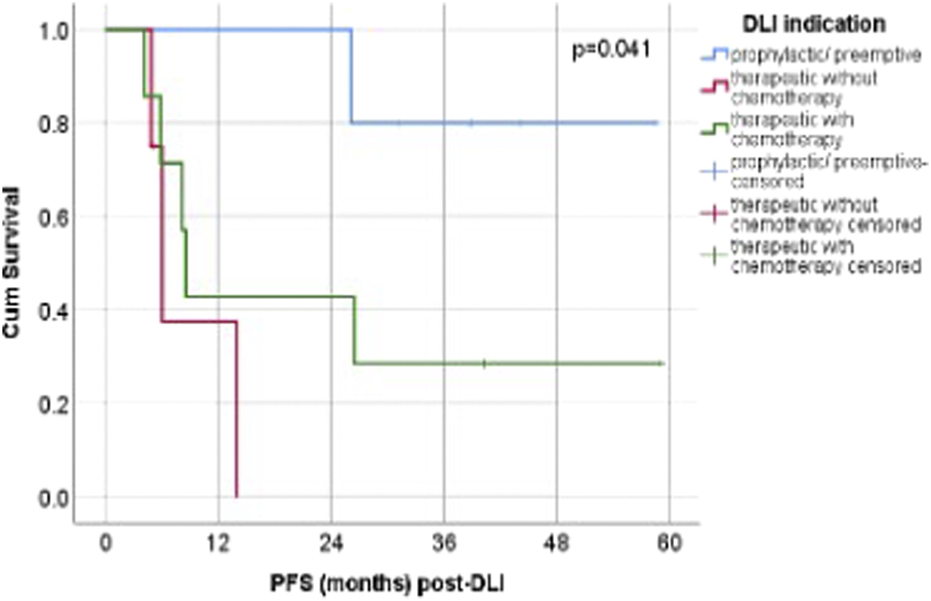

The highest median OS was observed in the prophylactic/preemptive group and was not reached during follow-up. Among the therapeutic groups, the highest median OS was seen in patients who received chemotherapy (23.84 months, 95% CI 2.49-45.18 months), compared to without chemotherapy (13.81 months, 95% CI could not be estimated) (p = 0.384) (Figure 3). Although this difference did not reach statistical significance, patients receiving prophylactic/preemptive DLI demonstrated better survival, particularly beyond the first year post-HSCT. This lack of statistical significance may be related to the limited sample size, variability in follow-up, and the proportion of censored cases.

FIGURE 3

Post-DLI PFS according to DLI. Abbreviations: p/p = prophylactic/preemptive; n = number; chemo- = without chemotherapy, chemo+ = with chemotherapy.

The Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 3) demonstrate a visible separation between the three indication groups, with the prophylactic/preemptive group maintaining the highest probability of survival over time, followed by the therapeutic + chemotherapy group, and lastly the therapeutic without chemotherapy group. In the prophylactic/preemptive cohort, survival probability remained relatively high and stable for an extended period. The curve’s plateau indicate that a substantial proportion of patients are alive and disease-free at the last follow-up. The therapeutic without chemotherapy group displayed an earlier drop in survival probability, reflecting poorer outcomes with DLI alone. The therapeutic + chemotherapy group showed intermediate outcomes, with an initial decline in survival probability but a more gradual slope thereafter, reflecting effective disease debulking prior to DLI in some cases.

Despite these differences, the log-rank test confirmed that the observed separation was not statistically significant (p = 0.384). Nevertheless, the pattern supports the hypothesis that earlier prophylactic/preemptive DLI may be associated with improved survival compared with therapeutic use in overt relapse.

Regarding progression-free survival (PFS), patients who received prophylactic or preemptive DLI did not reach a median PFS (not estimable). Among patients treated therapeutically without concomitant chemotherapy, the median PFS was 6.05 months (95% CI 4.28–7.82; 1/4 censored), whereas in the group receiving therapeutic DLI combined with chemotherapy, the median PFS was 8.55 months (95% CI 7.54–9.56; 2/7 censored).

A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of individual variables on the hazard of death or disease relapse, providing an estimate of their relative risk while accounting for time-to-event data.

In the Cox regression analysis (Table 2), the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with survival outcomes. Patients who developed acute GVHD had a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.640 (95% CI, 0.338–7.943; p = 0.539) compared with those who did not. The confidence interval was wide and crossed 1.0, reflecting substantial variability in the estimate and suggesting that any potential effect of acute GVHD on survival is uncertain. These results imply that, in this cohort, the development of acute GVHD post-DLI did not have a measurable or consistent impact on overall prognosis and should be interpreted cautiously, particularly given the likely influence of limited sample size.

TABLE 2

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Sex | ||

| F | Reference | |

| M | 6.084 (0.753-49.177) | 0.090 |

| Age | 1.143 (0.979-1,335) | 0.091 |

| DLI indication | ||

| Prophylactic/preemptive | Reference | |

| Therapeutic without chemotherapy | 14.321 (1.309-156.710) | 0.029 |

| Therapeutic with chemotherapy | 5.992 (0.694-51.738) | 0.104 |

| FAB classification | ||

| M0-2 | Reference | |

| M4-5 | 0.855 (0.228-3.215) | 0.817 |

| MLL status | ||

| Negative | Reference | |

| Positive | 0.295 (0.036-2.385) | 0.252 |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| RIC | Reference | |

| MAC | 0.211 (0.046-0.965) | 0.045 |

| Acute GVHD post-DLI | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.640 (0.338-7.943) | 0.539 |

Univariate Cox Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting Outcome After DLI. Abbreviation: DLI, Donor Lymphocyte Infusion, HR, Hazard Ratio, CI, Confidence Interval, FAB, French-American-British classification, RIC, Reduced Intensity Conditioning, MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning, GVHD, Graft-versus-Host Disease.

MLL rearrangement status was not associated with a statistically significant effect on survival. Patients with MLL-positive disease had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.295 (95% CI, 0.036–2.385; p = 0.252) compared with MLL-negative patients. Although the point estimate suggests a possible reduction in risk, the wide confidence interval crossing 1.0 reflects considerable uncertainty, indicating that the result is not statistically reliable. These findings suggest that MLL rearrangement did not exert a consistent influence on survival and should be interpreted cautiously, particularly in light of the limited sample size.

In the Cox regression analysis, sex did not emerge as a statistically significant predictor of survival. Males had a hazard ratio (HR) of 6.084 (95% CI, 0.753–49.177) compared with females, with a p-value of 0.090. Although this indicates a possible trend toward higher mortality risk in males, the association did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p < 0.05). The very wide confidence interval suggests substantial variability in the estimate, most likely attributable to the limited sample size or small number of events. Accordingly, while the data may hint at a potential sex-related difference in outcome, this finding should be interpreted with caution and regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive.

In univariate analysis, the indication for donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) was significantly associated with the studied outcome. Patients who received therapeutic DLI without prior chemotherapy had a markedly increased hazard compared to those receiving prophylactic or preemptive DLI, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 14.321 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.309–156.710; p = 0.029), indicating a statistically significant higher risk. These results indicate that the type of DLI indication may substantially influence outcomes.

4 Discussion

Our retrospective analysis of pediatric AML patients undergoing DLI with azacitidine after HSCT demonstrates encouraging results, particularly in the prophylactic/preemptive setting, where we observed an overall survival (OS) of 80% and durable full donor chimerism. In the therapeutic DLI group, outcomes were less favorable, reflecting the well-documented challenges of treating overt relapse post-HSCT.

These findings are consistent with previous pediatric and adult studies that have explored the role of DLI, often in combination with hypomethylating agents, for relapse prevention or treatment after allogeneic transplantation.

For instance, Rettinger et al. (2017) showed that preemptive immunotherapy guided by chimerism could prevent relapse in pediatric AML, reporting sustained remissions in patients with early interventions. Similarly, Bellucci et al. (2002) demonstrated that prophylactic DLI could enhance immune reconstitution and sustain remission in multiple myeloma, establishing a mechanistic precedent that has since been explored in AML.

The combination of azacitidine with DLI has gained traction due to its potential to mitigate T-cell exhaustion and enhance the GVL effect without significantly increasing GVHD risk. Li et al. (2022), in a meta-analysis, concluded that this approach is effective in patients with relapsed AML and MDS after HSCT, aligning with our observation that azacitidine plus DLI is well tolerated and achieves complete donor chimerism in a substantial proportion of patients.

In the pediatric setting, Huschart et al. (2021) reported the feasibility and safety of azacitidine with prophylactic DLI in high-risk pediatric AML, similar to our cohort’s favorable outcomes in the preemptive group. More recently, Booth et al. (2023) highlighted improved survival and bone marrow T-cell repertoire diversification with azacitidine plus prophylactic DLI, underscoring the immunologic rationale behind this approach.

Our therapeutic DLI group, where patients received DLI primarily for frank relapse, had an OS of 45.4%, mirroring outcomes reported by Kharfan-Dabaja et al. (2018) who found comparable long-term survival between DLI and second HSCT in adult AML patients. However, our data emphasize the superior outcomes achieved when DLI is used preemptively rather than in overt relapse, consistent with findings from Guillaume et al. (2021) and Caldemeyer et al. (2017) who reported higher long-term survival rates in mixed-chimeric or high-risk populations treated preemptively.

GVHD remains a concern with DLI, particularly after multiple infusions or in the setting of unrelated/haploidentical donors. In our study, significant GVHD developed in only two patients (12.5%), which is comparable to the incidence rates of 10%–20% reported in large series (e.g., Suryaprakash et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023), suggesting that careful patient selection, monitoring, and concurrent azacitidine may mitigate GVHD risk.

Finally, the emergence of FLT3 inhibitors and novel immunotherapeutics offers future avenues for combination with DLI. As noted by Najima (2023) and Kreidieh et al. (2022), integrating targeted agents may further improve outcomes, especially in FLT3-mutated cases, a subgroup also represented in our cohort.

Donor lymphocyte infusion in pediatric AML is a fairly niche area and most publications are case reports, small case series, or retrospective registry analyses, because DLI is more studied in adult AML or in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia/relapse settings. In Table 3 is a list of peer-reviewed articles specifically addressing DLI in pediatric AML, including mixed chimerism or progressive mixed chimerism.

TABLE 3

| Study | No of patients | Indication of DLI | Survival rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bader et al. (2004) | 81 | Prophylactic (CC, MC) | 52% EFS at 3 years | GvHD, TRM Multicenter trial |

| Rettinger et al. (2011) | 71 | Preemptive | GvHD (75%) Multicenter trial |

|

| Gefen et al. (2013) | 2 | Therapeutic | 0% | GvHD, AML subset |

| Rujkijyanont et al. (2013) | 16 | Prophylactic (MC) | GvHD, AML subset | |

| Gozdzik et al. (2015) | 11 | Prophylactic, preemptive, therapeutic | GvHD, AML subset | |

| Huschart et al. (2021) | 11 | Prophylactic | 100% | GvHD (10%), mFU 17months |

| Booth et al. (2023) | 17 | Prophylactic | 88.2% | GvHD |

Selected studies of DLI in pediatric AML.

In this cohort of studies examining donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) across various indications, both prophylactic and therapeutic approaches demonstrate heterogeneous outcomes with respect to survival and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) incidence. Bader et al. (2004) reported a 52% event-free survival (EFS) at 3 years in a multicenter trial of 81 patients receiving prophylactic DLI and more recent analyses, such as Huschart et al. (2021) and Booth et al. (2023), demonstrated high survival rates (up to 100% and 88.2%, respectively) with prophylactic DLI, accompanied by relatively low GvHD incidence, highlighting potential improvements in patient selection, dosing strategies, and supportive care over time. Collectively, these studies illustrate that while prophylactic and preemptive DLIs can confer survival benefits, their statistical impact on GvHD incidence and overall outcomes is strongly influenced by timing, patient population, and sample size, emphasizing the need for larger, controlled studies to determine optimal DLI strategies.

This study represents one of the largest pediatric single-center series evaluating DLI combined with azacitidine post-HSCT. We observed durable remission and chimerism correction with prophylactic/preemptive DLI, while therapeutic DLI for overt relapse remained less effective.

Our findings align with prior pediatric series (Rettinger et al., 2017; Huschart et al., 2021; Booth et al., 2023), highlighting the feasibility and safety of azacitidine + DLI, particularly in the preemptive setting. Adult studies (Loke et al., 2021; Craddock et al., 2016) also support its role in relapse prevention, though outcomes in overt relapse remain modest. The low incidence of GVHD in our cohort suggests that azacitidine may help balance GVL and GVHD.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective design carries an inherent risk of selection bias and unmeasured confounding. The small sample size and absence of a control group reduce statistical power and increase the likelihood of type II error. In addition, the limited number of events did not allow for reliable multivariable modeling. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Larger prospective multicenter studies are required to optimize timing, dosing, and integration with novel agents (e.g., FLT3 inhibitors, venetoclax).

5 Conclusion

In summary, our findings indicate that the combination of azacitidine and donor lymphocyte infusion is safe and feasible in pediatric AML following allogeneic HSCT, with the most favorable outcomes seen when applied prophylactically or preemptively to stabilize donor chimerism and control MRD. While the data point toward a potential clinical benefit, the study was not powered to establish definitive efficacy, and the results should be interpreted in light of the cohort’s limited size and inherent heterogeneity.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institution. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CJ: Writing – original draft, Data curation. II: Software, Writing – original draft. AS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. IA: Data curation, Writing – original draft. MC: Data curation, Writing – original draft. DP: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. IC: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. AI: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. AdC: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. AC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish. We thank the nursing staff and laboratory teams at Fundeni Clinical Institute for their contributions to patient care and monitoring.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer BA declared a past co-authorship with the author AC to the handling editor at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Aza, azacitidine; CLAG-M, cladribine, cytarabine, G-CSF, mitoxantrone; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; DCAG, decitabine, cytarabine, aclarubicin, G-CSF; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; FLAG, fludarabine, cytarabine, G-CSF; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MDC, mixed donor chimerism; MRD, measurable residual disease; OS, overall survival; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning.

References

1

Accorsi Buttini E. Doran C. Malagola M. Radici V. Galli M. Rubini V. et al (2024). Donor lymphocyte infusion in the treatment of post transplant relapse of acute myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes significantly improves overall survival: a French–Italian experience of 134 patients. Cancers16, 1278. 10.3390/cancers16071278

2

Admiraal R. Nierkens S. de Witte M. A. Petersen E. J. Fleurke G. J. Verrest L. et al (2017). Association between anti-thymocyte globulin exposure and survival outcomes in adult unrelated haemopoietic cell transplantation: a retrospective, pharmacodynamic cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol.4 (4), e183–e191. 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30029-7

3

Bader P. Kreyenberg H. Hoelle W. Dueckers G. Kremens B. Dilloo D. et al (2004). Increasing mixed chimerism defines a high-risk group of childhood acute myelogenous leukemia patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation where pre-emptive immunotherapy may be effective. Bone Marrow Transpl.33, 815–821. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704444

4

Bader P. Kreyenberg H. Bacigalupo A. (2024). “Documentation of engraftment and chimerism after HCT,” in The EBMT handbook: hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies. SuredaA.CorbaciogluS.GrecoR.8th ed. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer). 10.1007/978-3-031-44080-9_21

5

Bejanyan N. Haddad H. Brunstein C. (2015). Alternative donor transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Med.4 (6), 1240–1268. 10.3390/jcm4061240

6

Bejanyan N. Weisdorf D. J. Logan B. R. Wang H. L. Devine S. M. de Lima M. et al (2015). Survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia relapsing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a center for international blood and marrow transplant research study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl.21 (3), 454–459. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.11.007

7

Bellucci R. Alyea E. P. Weller E. Chillemi A. Hochberg E. Wu C. J. et al (2002). Immunologic effects of prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusion after allogeneic marrow transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood99, 4610–4617. 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4610

8

Booth N. Mirea L. Huschart E. Miller H. Salzberg D. Campbell C. et al (2023). Efficacy of azacitidine and prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusion after HSCT in pediatric patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: a retrospective pre-post study. Transpl. Cell. Ther.29, 330.e1–330.e7. 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.02.009

9

Caldemeyer L. E. Akard L. P. Edwards J. R. Tandra A. Wagenknecht D. R. Dugan M. J. (2017). Donor lymphocyte infusions used to treat mixed-chimeric and high-risk patient populations in the relapsed and nonrelapsed settings after allogeneic transplantation for hematologic malignancies are associated with high five-year survival if persistent full donor chimerism is obtained or maintained. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl.23, 1989–1997. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.07.007

10

Castagna L. Sarina B. Bramanti S. Perseghin P. Mariotti J. Morabito L. (2016). Donor lymphocyte infusion after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transfus. Apher. Sci.54 (3), 345–355. 10.1016/j.transci.2016.05.011

11

Chorão P. Montoro J. Balaguer-Roselló A. Guerreiro M. Villalba M. Facal A. et al (2023). T cell-depleted peripheral blood versus unmanipulated bone marrow in matched sibling transplantation for aplastic anemia. Transpl. Cell. Ther.29, 322.e1–322.e5. 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.01.016

12

ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Azacitidine combined with donor lymphocyte infusion for prevention of recurrence after haploidentical HSCT in high-risk AML. NCT06754540. Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06754540 (Accessed on August 15, 2025).

13

Cluzeau T. Sebert M. Loschi M. Adès L. Thepot S. Carre M. et al (2023). Phase I/II clinical trial evaluating azacitidine + venetoclax + donor lymphocyte infusion in post-transplant relapse MDS/AML: preliminary results of VENTOGRAFT, a GFM study. Blood142 (Suppl. 1), 3246. 10.1182/blood-2023-178021

14

Craddock C. Labopin M. Robin M. Finke J. Chevallier P. Yakoub-Agha I. et al (2016). Clinical activity of azacitidine in patients who relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica101 (7), 879–883. 10.3324/haematol.2015.140996

15

Dholaria B. Savani B. N. (2020). Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation after CAR T-cell therapy: safe, effective and contentious. Br. J. Haematol.189 (1), 21–23. 10.1111/bjh.16262

16

Egan G. Tasian S. K. (2023). Relapsed pediatric acute myeloid leukaemia: state-of-the-art in 2023. Haematologica108 (9), 2275–2288. 10.3324/haematol.2022.281106

17

Gefen A. Weyl-Ben-Arush M. Khalil A. Arad-Cohen N. Porat I. Zaidman I. (2013). Donor lymphocyte infusions in pediatric patients with malignant and non-malignant diseases after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a single center experience. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl.19 (2), S247. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.11.323

18

Gozdzik J. Rewucka K. Krasowska-Kwiecien A. Pieczonka A. Debski R. Zaucha-Prazmo A. et al (2015). Adoptive therapy with donor lymphocyte infusion after allogenic hematopoietic SCT in pediatric patients. Bone Marrow Transpl.50, 51–55. 10.1038/bmt.2014.200

19

Guillaume T. Thépot S. Peterlin P. Ceballos P. Bourgeois A. L. Garnier A. et al (2021). Prophylactic or preemptive low-dose azacitidine and donor lymphocyte infusion to prevent disease relapse following allogeneic transplantation in patients with high-risk acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Transpl. Cell. Ther.27, 839.e1–839.e6. 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.06.029

20

Huschart E. Miller H. Salzberg D. Campbell C. Beebe K. Schwalbach C. et al (2021). Azacitidine and prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusions after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for pediatric high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol.38, 154–160. 10.1080/08880018.2020.1829220

21

Hussain S. A. Khan A. N. Thammineni V. S. Riaz M. N. Shahzad M. Pulipati P. et al (2021). Outcomes with preemptive donor lymphocyte infusions after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol.39 (15 Suppl), e19014. 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.e19014

22

Kharfan-Dabaja M. A. Labopin M. Polge E. Nishihori T. Bazarbachi A. Finke J. et al (2018). Association of second allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant vs donor lymphocyte infusion with overall survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia relapse after first transplant. JAMA Oncol.4 (9), 1245–1253. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2091

23

Kolb H. J. Mittermüller J. Clemm C. Holler E. Ledderhose G. Brehm G. et al (1990). Donor leukocyte transfusions for treatment of recurrent chronic myelogenous leukemia in marrow transplant patients. Blood76, 2462–2465. 10.1182/blood.V76.12.2462.2462

24

Koreth J. Schlenk R. Kopecky K. J. Honda S. Sierra J. Djulbegovic B. et al (2009). Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. JAMA301, 2349–2361. 10.1001/jama.2009.813

25

Kreidieh F. Abou Dalle I. Moukalled N. El-Cheikh J. Brissot E. Mohty M. et al (2022). Relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia: an overview of prevention and treatment. Int. J. Hematol.116, 330–340. 10.1007/s12185-022-03416-7

26

Li X. Wang W. Zhang X. Wu Y. (2022). Azacitidine and donor lymphocyte infusion for patients with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a meta-analysis. Front. Oncol.12, 949534. 10.3389/fonc.2022.949534

27

Loke J. Vyas H. Craddock C. (2021). Optimizing transplant approaches and post-transplant strategies for patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Oncol.11, 666091. 10.3389/fonc.2021.666091

28

Najima Y. (2023). Overcoming relapse: prophylactic or pre-emptive use of azacitidine or FLT3 inhibitors after allogeneic transplantation for AML or MDS. Int. J. Hematol.118, 169–182. 10.1007/s12185-023-03596-w

29

Peters D. T. Chang C. Snow A. Buhlinger K. M. Patel B. Dawson S. et al (2024). Azacitidine and venetoclax with or without donor lymphocyte infusion in relapsed AML post allo-HSCT: a single-institution retrospective study. Blood144 (Suppl. 1), 1481. 10.1182/blood-2024-193668

30

Pulsipher M. A. Langholz B. Wall D. A. Schultz K. R. Bunin N. Carroll W. et al (2015). Risk factors and timing of relapse after allogeneic transplantation in pediatric ALL: for whom and when should interventions be tested?Bone Marrow Transplant.50 (9), 1173–1179. 10.1038/bmt.2015.103

31

Rettinger E. Willasch A. M. Kreyenberg H. Borkhardt A. Holter W. Kremens B. et al (2011). Pre-Emptive immunotherapy in childhood acute myeloid leukemia for patients showing evidence of mixed chimerism after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood118 (20), 5681–5688. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348805

32

Rettinger E. Merker M. Salzmann-Manrique E. Kreyenberg H. Krenn T. Dürken M. et al (2017). Preemptive immunotherapy for clearance of molecular disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow. Transplant.23 (1), 87–95. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.10.006

33

Rujkijyanont P. Morris C. Kang G. Gan K. Hartford C. Triplett B. et al (2013). Risk-adapted donor lymphocyte infusion based on chimerism and donor source in pediatric leukemia. Blood Cancer J.3, e137. 10.1038/bcj.2013.39

34

Schroeder T. Stelljes M. Christopeit M. Esseling E. Scheid C. Mikesch J. H. et al (2023). Azacitidine, lenalidomide and donor lymphocyte infusions for relapse of myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia after allogeneic transplant: the Azalena-trial. Haematologica108, 3001–3010. 10.3324/haematol.2022.282570

35

Sockel K. Wermke M. Radke J. Kiani A. Schaich M. Bornhäuser M. et al (2011). Minimal residual disease-directed preemptive treatment with azacitidine in patients with NPM1-mutant acute myeloid leukemia and molecular relapse. Haematologica96 (10), 1568–1570. 10.3324/haematol.2011.044388

36

Suryaprakash S. Sun Y. Tang L. Keerthi D. Qudeimat A. Talleur A. C. et al (2023). Risk-adapted donor lymphocyte infusion after hematopoietic cell transplant in pediatric and young adult patients is associated with low risk of graft versus host disease. Blood142 (Suppl. 1), 7042. 10.1182/blood-2023-182639

37

Tan J. L. Curtis D. J. Muirhead J. Swain M. I. Fleming S. A. Cirone B. et al (2024). CD34 chimerism directed donor lymphocyte infusion with or without azacitidine results in reduced relapse and superior overall survival when full donor chimerism is achieved in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients with acute myeloid leukaemia/myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk.24 (11), e852–e860. 10.1016/j.clml.2024.07.006

38

van Rhee F. Szydlo R. M. Hermans J. Devergie A. Frassoni F. Arcese W. et al (1997). Long-term results after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase: a report from the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant.20 (7), 553–560. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700933

39

Yang L. Lai X. Yang T. Lu Y. Liu L. Shi J. et al (2023). Prophylactic versus preemptive modified donor lymphocyte infusion for high-risk acute leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a multicenter retrospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant.59, 85–92. 10.1038/s41409-023-02137-7

40

Zuanelli Brambilla C. Ruiz J. D. Lobaugh S. M. Dahi P. B. Young J. W. Gyurkocza B. et al (2020). Long-term survival in patients with AML or MDS relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: importance of second cell therapy. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant.26 (3 Suppl), S97–S98. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.12.598

Summary

Keywords

donor lymphocyte infusion, azacitidine, pediatric acute myeloid leukemia, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, graft-versus-leukemia, graft-versus-host disease

Citation

Bica AM, Marcu AD, Jercan CG, Iordan I, Serbanica AN, Avramescu I, Colita M, Popa DC, Constantinescu I, Ichim AM, Colita A and Colita A (2026) Donor lymphocyte infusion combined with azacitidine after allogeneic HSCT in pediatric AML: a single-center retrospective analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1727492. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1727492

Received

17 October 2025

Revised

18 November 2025

Accepted

28 November 2025

Published

08 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Bica, Marcu, Jercan, Iordan, Serbanica, Avramescu, Colita, Popa, Constantinescu, Ichim, Colita and Colita.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cristina Georgiana Jercan, cristina.jercan@umfcd.ro

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.