Abstract

Shadi Hamid, in his book “The Problem of Democracy, advocates for the promotion of minimalist democracy for the Middle East. Can minimalist democracy respond to the aspirations of the Arab public? Using data from the Arab Barometer (2018) survey, I emphasize that many citizens of Arab countries define democracy by its expected economic outcomes. Whether minimalist democracy can spur economic development is a puzzle. Literature on democratization and economic growth is inconclusive. In the Middle East and North Africa region, ballot box alone may not overcome significant barriers, such as overriding interest groups and corruption, to spur development. Democratic openings in the region often failed to promote expected economic growth. Therefore, while minimalist democracy would be an improvement for the current standards of governance in the region, it may fail to respond to the aspirations of the masses, making authoritarian reversion a likely outcome.

Introduction

Democracy has been a contested term since the time of the ancient Greeks (Russell, 1945, p. 190). In recent decades, the main debate is about whether procedural (minimalist) or substantive definitions are more appropriate for classifying and analyzing different regime types (Robinson, 2006, p. 517).1Hamid (2022), in his book The Problem of Democracy, advocates for a minimalist definition of democracy for the Arab Middle East from the perspective of democracy promotion. While support for Arab authoritarian regimes undermines American interests, supporting democratic minimalism would be beneficial for both the US and host countries.

Hamid (2022, p. 44) argues that his goal is to sever a democracy’s performance indicators from the question of whether it is worth supporting. He defines democratic minimalism as a “de-instrumentalized” version of the democratic idea and separates it from liberalism (2022, p. 44). Democracy represents the preferences of majorities or pluralities, whereas liberalism prioritizes individual freedoms, personal autonomy, and social progressivism (Hamid, 2022, p. 6). If democracy is a form of government, liberalism is a form of governing (Hamid, 2022, p. 17).

While cross-national studies indicate that US foreign assistance has a positive impact on democracy building (Finkel et al., 2007, p. 436), democracy promotion programs towards the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region often focused on fulfilling the security imperatives of the United States and the recipient regimes (Snider, 2022, p. 8–9), potentially explaining why assistance programs did not necessarily lead to sustainable forms democratic governance. Even before the 9/11 attacks and the rise of radical terrorism, global powers had been more willing to accept the prevalence of authoritarianism in the MENA than elsewhere in the world (King, 2009, p. 90). Amidst this bleak outlook, Hamid’s The Problem of Democracy offers a fresh and citizen-oriented argument on democracy promotion.

Research methodology

In this essay, I argue that, while Hamid’s contribution to the existing debates is quite valuable, his conceptualization nevertheless risks creating disconnections between the aspirations of the Arab public, which associates democracy with economic well-being, and the US foreign policy perspective that Hamid seeks to influence. I first review procedural and substantive definitions of democracy. Then I map out the current standing of Arab MENA countries through employing V-Dem’s Elected officials index (procedural) and liberal component index (substantive).

Using Arab Barometer (2018, Wave V),2 I emphasize that many citizens of Arab countries define democracy by its expected economic outcomes. However, whether minimalist democracy can spur economic growth, particularly in the MENA region, is questionable. First, minimalist democracies may fail to overcome critical institutional barriers to spur development. Second, democratic openings in the MENA region, which concurred with Islamist parties in power, did not necessarily produce higher levels of growth. As Tunisian case indicates, the inability to produce development under democratization phase can frustrate masses, which can increase the likelihood of reversion back to an authoritarian rule.

Defining democracy

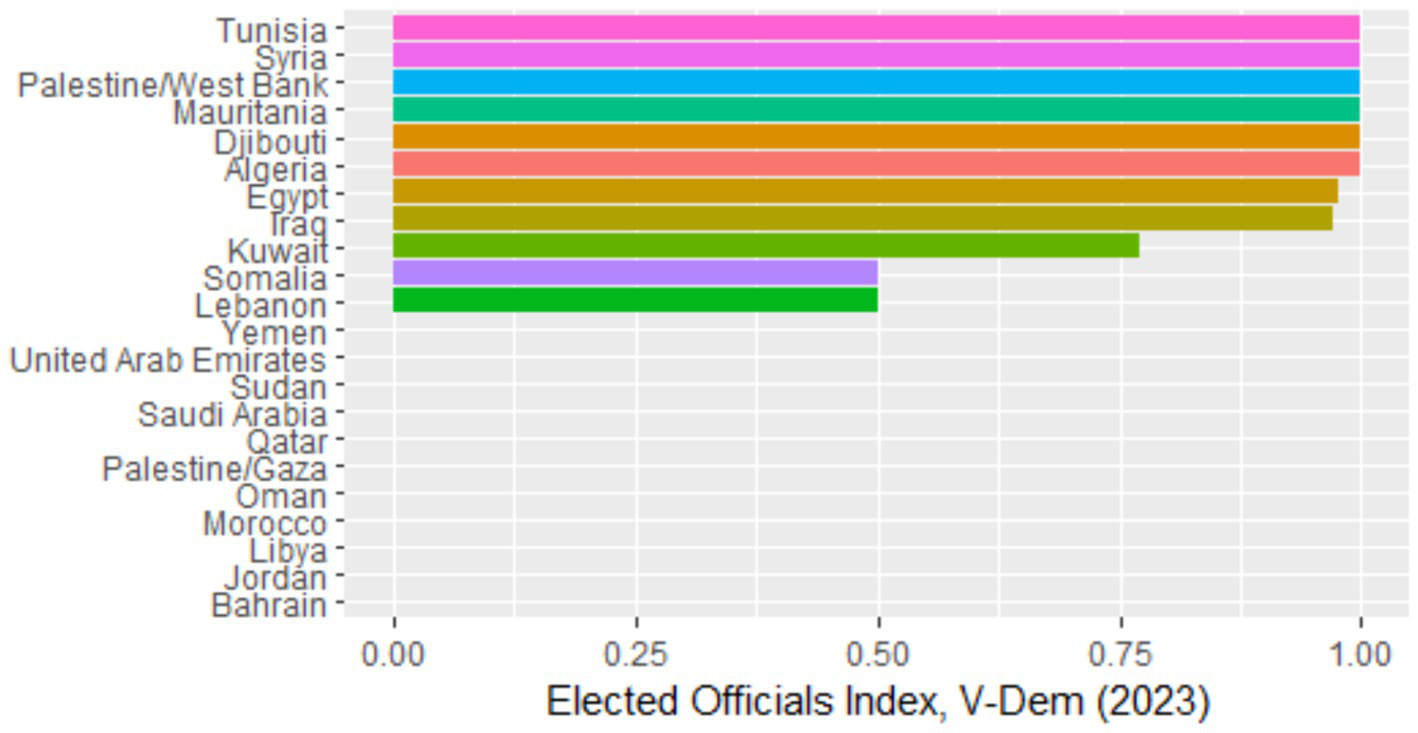

Procedural or minimalist definitions of democracy focus exclusively on elections, without reference to the kinds of outcomes that they produce (Cheibub et al., 2010, p. 8). Cheibub et al. (2010, p. 3) definition emphasizes popular election with multi-party competition and alternation of power. Dahl (1971) conceptualization of polyarchy3 consists of open contestation and participation. In a similar vein, Schumpeter’s definition emphasizes democracy’s procedural elements: “that institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of competitive struggle for people’s vote” (Hamid, 2022, p. 45). V-Dem’s Elected Officials Index also conceptualizes a minimalist form of democracy, as it focuses on whether the chief executive and the legislature are elected.4Figure 1 displays the distribution of Elected Officials Index for Arab Middle Eastern countries:

Figure 1

Elected officials index, V-Dem (2023).

As Figure 1 indicates, 6 out of 22 Arab MENA countries have a complete (1) Elected Officials Index, whereas 11 countries have the lowest Elected Officials Index (0). For the Arab MENA, the mean Elected Officials Index is 0.44 with a standard deviation value is 0.47. In comparison, the global average is 0.83, with a standard deviation value of 0.36.

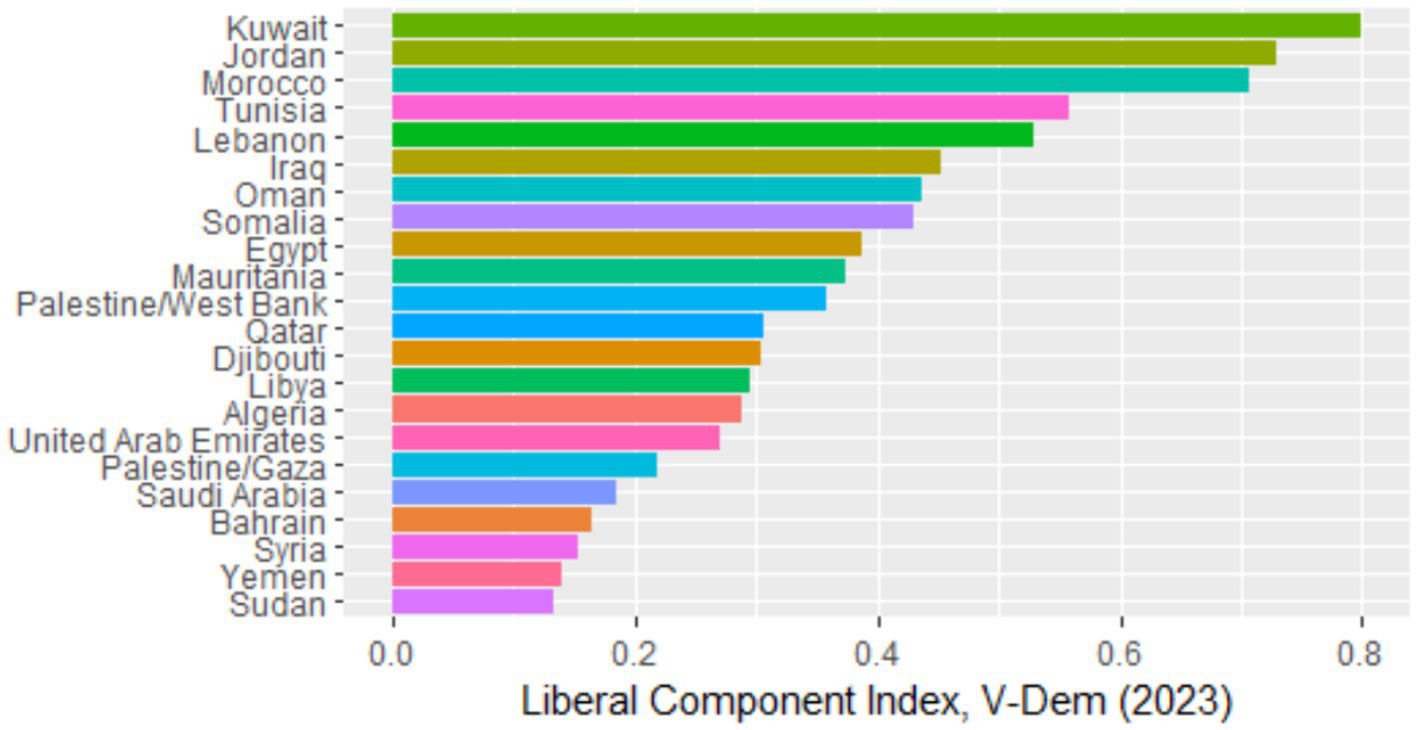

Substantive definitions emphasize that institutions are necessary but not sufficient conditions to characterize a political regime (Cheibub et al., 2010, p. 8). Democracies ought to bring something more than elections. According to William Easterly, scholars have put too much emphasis on majority voting as the definition of democracy while neglecting unalienable rights and the consent of the governed (Easterly, 2014, p. 143). Although majority voting might be necessary, it is certainly not sufficient. Rueschemeyer et al. (1992, p. 41) define democracy as a system in which the “disadvantaged many have, as citizens, a real voice in the policy making process,” and focus on class struggles and the resulting push for social equality. Mainwaring et al. (2007) emphasize that democracies must protect political and civil rights, and elected authorities under democracies must exercise real governing power. Freedom House employs indices of political rights and civil liberties to define democracy (Cheibub et al., 2010, p. 8). V-Dem’s Liberal component index measures the level of individual and minority rights protection against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority (Coppedge et al., 2023). Figure 2 shows the distribution of Liberal component index5 for Arab countries (2023):

Figure 2

Liberal component index, V-Dem (2023).

As Figure 2 indicates, there is a significant variation in the liberal component index within the region. The mean liberal component index for Arab MENA countries is 0.37 with a standard deviation value of 0.19. The global mean is 0.59 with a standard deviation of 0.36. Some countries, such as Jordan and Morocco, which have the lowest Elected Officials Index (Figure 1) have relatively high Liberal Component Index. Syria and Algeria, which have the highest Elected Officials Index, have relatively low levels of Liberal Component Index. Therefore, while there are significant within country differences between Elected Officials and Liberal Component Index, Arab countries continue to lag the global average.

Debates on substantive and procedural forms of democracy are primarily motivated by concerns about classification and making inferences. Especially in the past three decades, many countries that initiated transitions have not fully consolidated their democracies (Schedler, 1998; Carothers, 2002). Applying the concept of democracy to cases for which it is not appropriate can lead to “conceptual stretching,” as the term loses its relevance for identifying regime types (Sartori, 1970). Following this logic, some scholars argue that employing more substantive definitions can provide a more effective toolkit to analyze and classify these regimes. One approach is adding adjectives to the term democracy to emphasize specific (or defunct) features of democracies (Collier and Levitsky, 1997, p. 437–438). When conducting inferential analyzes, however, the analysis will be unreliable if substantive elements of democracy relate to either dependent or independent variables (Cheibub et al., 2010, p. 28). For instance, if the absence of civil wars is a component of a democracy index, then a test between civil wars and democracy index will produce spurious outcomes. Substantive definitions can be more receptive to ideological influence (Munck et al., 2007, p. 477) as they rely more on subjective expert perspectives. Yet another concern is whether definitions of democracy can accurately capture the ideas and aspirations of people subject to its governance.

Democracy in the Middle East

In the Middle East, democratization initiatives of the US were frequently trumped by economic and security objectives (Levitsky and Way, 2006, p. 382). Authoritarian leaders in the region use liberal covers, such as gender quotas for already weak parliaments, to garner domestic and international legitimacy while denying the freedoms of association, assembly, and expression (Hamid, 2022, p. 200, 234). American support for these authoritarian leaders in the pursuit of stability paradoxically fuels the cycle of instability (Hamid, 2022, p. 24). For instance, as the Arab uprising developments indicate, the autocrat countries in the region can use their linkage and leverage to block democratization attempts in neighboring countries (Tansey et al., 2017, p. 1240–1245; Abrams, 2017, p. 100).

Hamid specifically makes the case for building minimalist democracies in the Middle East. Because Islam has retained an outsized role in public life (Hamid, 2022, p. 59), it conflicts with liberal values such as gender equality and criticizing religious texts (Hamid, 2022, p. 26, 82). The inability and unwillingness of Western powers to acknowledge these tensions has led to misplaced and unrealistic expectations about what the Middle East can become (Hamid, 2022, p. 27). As Rashid Rida emphasized, “popular participation is the closest thing to a solution for preventing twin despotism of religious and political despotism, and colonial dominance” (Hamid, 2022, p. 20).

Democratization can help countries to solve conflicts related to identity through peaceful means (Mazzuca and Munck, 2014, p. 1230). For instance, a democracy-first perspective would encourage political opening and discourage repression wherever possible, through either positive incentives or punitive measures (Hamid, 2022, p. 30). This would be particularly welcome in the Middle East and other Muslim-majority countries, which accommodate competing conceptions of Islam’s role in public life, often contributing to perennial conflict, ideological polarization, and the rise of repressive regimes (Hamid, 2022, p. 18, 19, 21). Democracy, through removing unpredictability, provides the means of regulating existing conflicts through peaceful alterations of power (Hamid, 2022, p. 54). Furthermore, democracy can facilitate political pluralism, which can lead to religious pluralism (Hamid, 2022, p. 75). Nevertheless, what remains ambiguous is whether such a minimalist practice of democracy can satisfy the demands of the Arab public.

Hamid’s fresh conceptualization is grounded in a policy-oriented framework. However, a weakness of his approach is that he does not consider the “demand” side of democratization, or the type of social contract that Arab citizens want. In analyzing the limitations of Democracy Aid programs in the Middle East, Erin Snider (2022, p. 29) emphasizes that “What international actors would see as imperative to supporting democracy was often at odds with local perspectives … and the reality of the political environment itself.” A particular example is that, irrespective of citizen demands, the US foreign aid bureaucracy would privilege market reform and democracy as one and the same (Snider, 2022, p. 100).

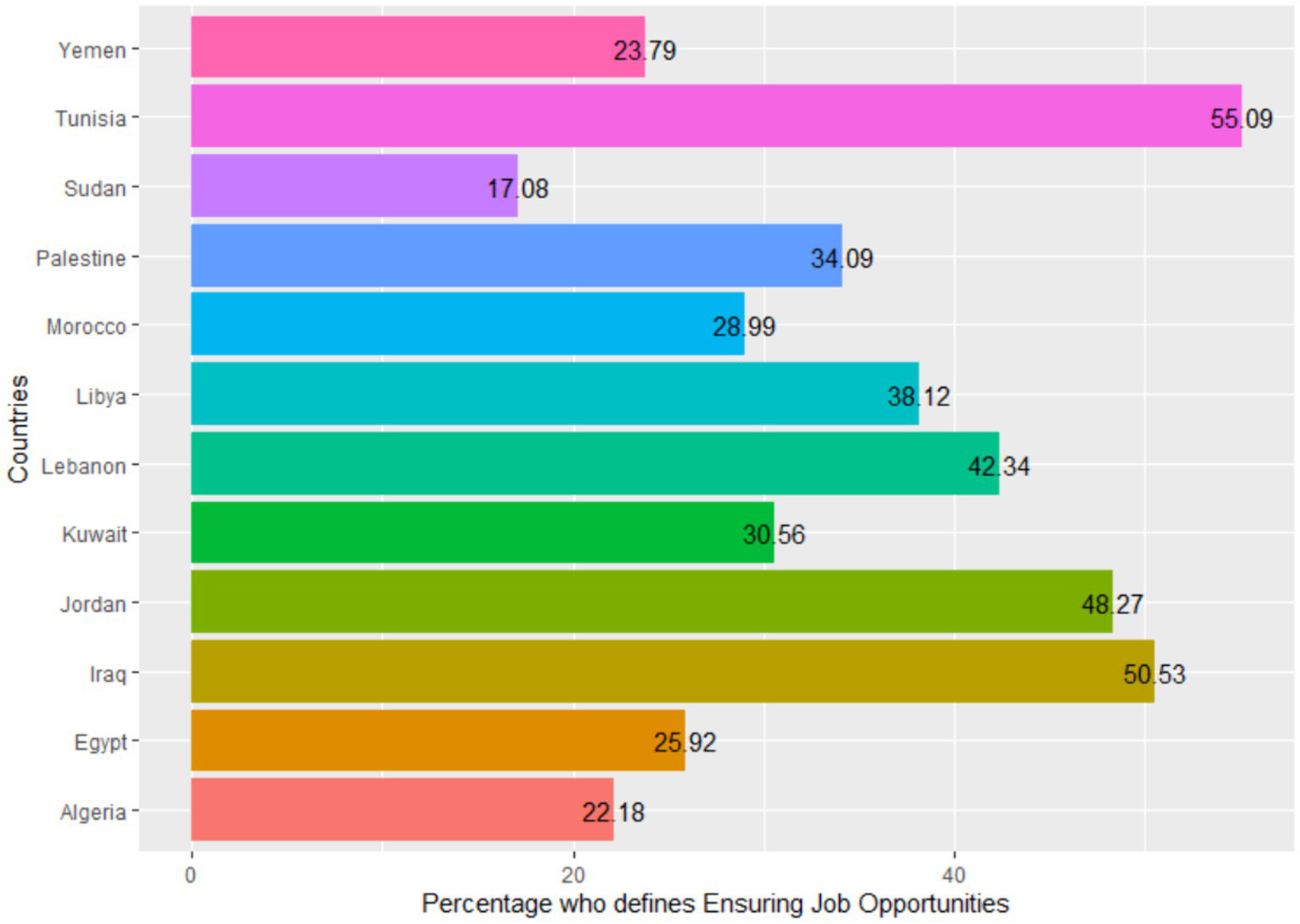

Any analysis of democracy that fails to consider what citizens want is incomplete. In a 2018 survey, the Arab Barometer asked respondents to indicate the most essential characteristic of democracy among the following options: “government ensures law and order,” “media is free to criticize the things that government does,” “government ensures job opportunities for all,” and “multiple parties compete fairly in election.” Figure 1 displays the percentages of respondents in different Arab countries who chose “government ensures job opportunities for all.”

According to Tessler (2011, p. 110), “economic issues are central to the way that many Arab citizens think about governance.” As Figure 3 indicates, a significant portion of Arab citizens primarily associate democracy with job creation.6 This includes Arab citizens with different ideological orientations, including those who prefer a greater role of Islam in public life7. In Iraq and Tunisia, which were among the more democratic regimes in 2018, majorities chose ensuring job opportunities. The percentages were lower in Algeria, Sudan, and Yemen, where pluralities preferred ensuring law and order. However, the responses from these civil-war-ridden countries do not negate the importance of job creation in Arab citizens’ preference for democracy.

Figure 3

Percentage of respondents who chose ensuring job opportunities as the most essential characteristic of a democracy (Weighted), Arab Barometer (2018, Wave V).

In many new democracies and developing countries, citizens may indicate support for democracy while maintaining attitudes that may be contested with the classical definitions of democracy (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007, p. 640). Many Arab citizens of Middle Eastern countries prefer democracies, but expect specific outcomes from democratic governance. Socio-economic grievances constituted a major factor for 2011 Arab uprising protests (Dalacoura, 2012, p. 66). As Sadiki and Saleh (2023, p. 1465) stated, “Freedom and dignity, so intertwined in the vocalized imaginaries of Arab Spring protestors, are not reducible to constitutional guarantees of rights. Nor are they assured through election laws, no matter how progressive in their multi-partism or gender parity.” By focusing mainly on a minimalist perspective and not considering the economic considerations of many Arab citizens, Hamid’s approach risks creating a gap between the priorities of the US foreign policy establishment and those of the Arab public. This can be quite consequential for scholars, as the American foreign policy establishment’s priorities—in particular, its democratization agenda—can heavily influence the research agenda of Middle East politics (Anderson, 2006, p. 209).

One can argue that although minimalist democracy may not immediately respond to the aspirations of masses, in the long turn it can generate potential benefits, such as economic development. In the next section, I focus on the puzzle of democracy and economic growth. I first examine main debates on democracy and development, then I turn my attention to specific dynamics within MENA countries.

Democracy and development

Scholars debate about the impact of democratic institutions on growth (Helliwell, 1994; Boix and Stokes, 2003, p. 538; Brancati, 2014, p. 1509; Przeworski and Limongi, 1993). According to an institutionalist perspective, democratization creates inclusive institutions, which can enhance property rights and therefore produce economic growth (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2013). However, the type of institutions that systematically correlate with economic growth are still unidentified (Robinson, 2006; Munck et al., 2007, p. 475). Therefore, whether democratic minimalism can produce economic development is a puzzle.

On one hand, elections can provide mechanisms of accountability. For instance, a ruling majority can establish wider economic and political rights and public services that support sustained economic growth for all (Easterly, 2014, p. 168).8 This could prevent the elite from expropriating the lands of the majority. Furthermore, democracy can induce politicians to professionalize the bureaucracy and abandon clientelism (Mazzuca and Munck, 2014, p. 1236). On the other hand, elections are not necessarily a panacea guaranteeing good governance. In fact, they can easily incorporate elements of clientelism, vote buying, and corruption (De Miguel et al., 2015; O'Donnell, 1993, p. 1359–1,361; Salloukh et al., 2015, p. 174–175). Public administration under democratization can end up serving particularistic ends rather than public goods (Mazzuca and Munck, 2014, p. 1234). These factors can create more dissatisfaction with the regime. For instance, in the Middle East, when citizens see wasta, they consider that their countries are less democratic (Ridge, 2023, p. 136).

Analyzing a global dataset, Brunkert et al. (2019, p. 7) find that deficient democracies do not consistently outperform autocracies in their ability to provide public goods. Latin American case studies indicate that elections under weak horizontal accountability, atomized society and inefficient state apparatus fail to respond to socio-economic needs of masses, and ultimately lead to the loss of prestige of the democratic government, its institutions and actors (O'Donnell, 1993, 1364–1365). The high likelihood of reverting back to authoritarian rule, coupled with the potential for economic crises, may pursue parties in new democracies to focus on maximizing office rather than reforming institutions for the sake of maintaining political power (Lupu and Riedl, 2013, p. 339–1365). Mere rotation of power, even under a constitutional framework, does not guarantee that democratization can satisfy the aspirations of the public.

This is particularly the case for Arab citizens, who tend to ascribe an economic understanding to the concept. Middle Eastern countries economically stagnated in the postcolonial era (1960–2019) compared to East Asian, Pacific, South Asian, Latin American, Caribbean, European, and Central Asian countries (Cammett et al., 2023, p. 306). Cronyism and corruption were two major factors that contributed to this stagnation (Cammett et al., 2023, p. 330). Unlike East Asian republics, Arab republics may not be able to sustain developmental growth under prevalent corruption9 (King, 2009, p. 205–206). Powerful interest groups, which are formed by “pre-reform economic elites,” lobby for state intervention in industries that benefit themselves, which often produce policy choices with little regard to public interests (Nabli et al., 2008, p. 120). They have often proved to be resilient to the reform process, including when reforms were designed to limit their rent-seeking opportunities (Nabli et al., 2008, p. 124). The Tunisian experience suggests that political openings may fail to yield significant economic development in the short term (Nabli and Nugent, 2023, p. 287). Given that political parties in the region already tend to be weak (Hamid, 2022, p. 206; Lust, 2023, p. 182), they may struggle in implementing policy platforms that can respond to their electorate’s electoral demands (Mutlu and Yasun, 2024, p. 10). A minimalist democracy may fail to challenge the economic status quo, as key groups, such as microentrepreneurs, young and unemployed citizens, may continue to lack access to formal finance, markets or government support programs.

Elected governments’ survival depends on their ability to deliver. The most successful democracies have experienced stable economic growth, which have enhanced their legitimacy (Diamond et al., 1987, p. 8). According to Przeworski et al. (2000), three consecutive years of economic recession decrease the odds of democratic survival substantively. A core part of Hamid’s analysis focuses on the role of Islamist parties, which tend to win elections in the region. Autocrats in the region tend to perceive Islamist parties as existential threats to be repressed, which contributes to de-democratization (Hamid, 2022, p. 86). Furthermore, American policymakers shared an instinctive distrust of Islamists, which can explain their disinclination to support electoral reform in the region (Hamid, 2011, p. 23). As Yildirim (2016, p. 232) emphasizes, the economic empowerment of the marginalized Islamic periphery may offer the most viable path to democratization. Given the key role of Islamist parties in democratization, especially their pervasiveness in the early elections, it makes sense to discuss their performance on economy, which is a key issue that the Arab electorate cares deeply about.

Islamist parties’ electoral success and economic development

Another of Hamid (2022, p. 191) suggestions is that the electoral success of Islamists is dependent on their charity and social service activities. The Washington Consensus or “structural adjustment” model, which was supported by the World Bank and the IMF in the 1980s and 1980s, emphasized “macroeconomic stability, trade and price liberalization, privatization, and competition as key ingredients for rapid economic growth” (Galal, 2008, p. 1). Islamist parties gained significant popularity as the Washington Consensus led to the withdrawal of the Arab states from social service provision (Cammett et al., 2023, p. 323–324). The subsequent vacuum was filled by Islamists who engaged in extensive social service provision and attacked the prevalent corruption in government and society with calls to piety (King, 2009, p. 12; Lee and Shitrit, 2023, p. 221).

However, the conducting charity in an authoritarian framework is qualitatively very different than governing the country, such as developing and implementing fiscal programs. Hamid analyzes Islamist parties’ governance experiences in Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, and Tunisia, focusing on the period from late 1980s up until the contemporary era. I am interested in understanding the performance of economy under their proximity to power. In none of the cases Islamist parties managed to govern their countries without significant impediments. In fact, in three the authority of Islamist parties was quite curtailed. In Morocco and Jordan, the monarch significantly limited the authority of parliament. In Egypt, Constitutional Court put barriers in front of Morsi government. Only in Tunisia Islamists enjoyed some autonomy to pursue their economic agenda, although Islamists always remained a part of fragile coalitions. However, one can still examine whether Islamist parties’ proximity to power could correlate with growth. Table 1 displays the percentage of economic growth in four critical countries (Egypt, Morocco, Jordan and Tunisia) based on World Bank data10 in comparison with decade-average growth levels.

Table 1

| Country | Islamist Period | Islamist period growth | 1990s Growth | 2000s Growth | 2010s Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | 2011–2013 | −0.22% | 2.15% | 2.89% | 1.63% |

| Jordan | 1989–1992 | −3.7% | 0.20% | 3.18% | −2.1% |

| Morocco | 2011–2021 | 1.66% | 1.67% | 3.49% | 2.17% |

| Tunisia | 2011–2019 | 0.67% | 3.31% | 3.34% | 0.8% |

Growth patterns in selected countries.

For Tunisia, I exclude period after 2019, as subsequent governments were mostly filled by technocrats. The growth level between 2011 and 2014, when Ennahda was the head of the TROIKA coalition, was 0.3%.

As Table 1 illustrates, Islamist party’s proximity to power does not necessarily lead to increase in economic growth. The average growth for Egypt between 2011 and 2013, when Islamist Mohamed Morsi led the presidency, was −0.22. In comparison, in 1990s, 2000s and 2010s Egypt experienced positive growth. In Jordan, the average growth level was −0.37% between 1989 and 1992, when a brotherhood member led the parliament and brotherhood was a part of the cabinet. Although Jordan’s income level declined in 2010s, it was still better than the performance of 1989–1992 coalition. In Morocco, the growth level was 1.66% between 2011 and 2021, when the brotherhood was a part of coalition governments. In Morocco, the coalition period managed to catch up with growth levels in 1990s but it fell behind levels in both 2000s and 2010s. Finally, in Tunisia, where the Islamist Ennahda had the biggest policy space in comparison to other country-cases, the growth level remained at 0.7%, which is significantly lower than the growth levels in 1990s and 2000s.

One could expect Islamist parties to be more successful in spurring development, given their market oriented, liberal approach to economy (Salem, 2020; Yildirim, 2016) and closer proximity to voters (Carkoglu et al., 2019, p. 17). Some of the causes of low growth can be attributed to stagnation in post Arab uprising era, as Tunisia’s economy shrank by −3.27% in 2011, whereas Egypt’s economy shrank by −0.46%. Furthermore, Islamist governance can have external impediments to growth, such as international lenders or regional powers being reluctant to cooperate (Hamid, 2022, p. 120; Tansey et al., 2017, p. 1226).

Regardless of causal dynamics, these findings point out to the discrepancy between social service provision through civil society and governing the country. Islamist parties can be quite successful in distributing resources in their neighborhoods, but they may still lack necessary skills or luck to bring economic development. This dynamic can explain why Islamist parties’ support diminish over time, especially following the initial transition elections (Abrams, 2017, p. 232). For instance, millions of Egyptians, many of whom had voted for Morsi, took to the streets to show their discontent, opening the path for the military coup (Masoud, 2023, p. 422). In both Morocco and Tunisia, the popularity of Islamist parties plummeted when they were unable to provide lasting solutions to socioeconomic issues (Zerhouni and Maghraoui, 2023, p. 682–683; Mutlu and Yasun, 2024). In Tunisia, a public that had become disillusioned with socioeconomic outcomes of revolution became receptive to populist messages of President Saied (Souilmi, 2023, p. 1437; Mutlu and Yasun, 2024).

Voters in democratizing countries tend to have more pressing material needs, where economic circumstances also tend to be more volatile (Mainwaring, 2022, p. 262). When facing a choice between economic interests and democratic principles, they may choose the undemocratic option (Svolik, 2019, p. 27–28). Under these circumstances, what the US or Western foreign policy establishment can do to salvage a democracy is very limited. As Mainwaring (2022, p. 230) indicates, “they [The EU and the US] have little capacity to thwart incremental executive takeovers.” For instance, despite spending millions of dollars for Tunisia’s development programs, the US could not prevent Kais Saied’s constitutional coup (Yerkes, 2023, p. 1358–1367). His office-aggrandizing reforms may have found a safe haven as the rule of law and generous economic policies are more popular than electoral democracy (Ridge, 2022, p. 1551).

In the MENA region, it is common for social groups, whether based on ethnicity, sectarianism, partisan or tribal ties to capture state institutions to benefit themselves rather than society (Lust, 2023, p. 156). For instance, decentralization reforms in Morocco and Jordan ultimately led to “elite capture,” as the local elite used these reforms to enhance their authority further (Clark, 2018). Therefore, when evaluating the suitability of different forms of democracy, it is also important to consider the local context, including tribes,11 which continue to be the main features of local society and culture (Wien, 2021, p. 479).12 Another factor is ethnic diversity, as the MENA region includes sizable Amazigh, Kurdish, and other minorities.13

Different forms of democracy carry different ramifications for the local context. A substantive approach would pay special attention to tribal decision-making processes to contextualize their effect on specific ends. A minimalist approach would focus on the integration of different groups to contestation and voting. Both large-N and small case study research would be beneficial to understand how different forms of democracy interact under diverse local contexts.

The problem of conceptual stretching

For a very long time, scholars of Middle East politics had been frustrated that transitologists had systematically ignored cases from the MENA region (Schedler, 1998, p. 5). Hamid’s innovative perspective in The Problem of Democracy puts the MENA region on spotlight regarding the role of external actors in democratization. Furthermore, it responds to a growing call for linking structural factors to democratization (Haggard and Kaufman, 2016, p. 129). His minimalist perspective makes sense, given that the primary audience happens to be Western and particularly American policy makers (Hamid, 2022, p. 149). A minimalist democracy would be an improvement for democratic standards in many countries in the region.

However, despite its merits, applying a minimalist perspective can create significant gaps between the expectations of the public and those of policy makers and scholars, as the public tends to think of democracy in terms of its economic outcomes. In other words, borrowing the term from Collier and Levitsky (1997), using a minimalist conceptualization of democracy can lead to conceptual stretching when the public is made up of “democrats with adjectives” (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007, p. 642), referring to democracy based on its specific economic outcomes.

A minimalist form of democracy may fail to overcome critical institutional barriers to produce economic growth. The type of institutions that produce economic growth remain ambiguous. Furthermore, elections can easily incorporate elements of clientelism, vote buying, particularism, and corruption, dynamics often associated with poor governance. In the Middle East, democratic openings, which concurred with Islamists getting proximity to power, did not produce notable increase in GDP per capita. Nevertheless, Hamid’s innovative work offers an excellent opportunity to rethink these factors in light of the role of external powers.

Statements

Author contributions

SY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ This debate also relates to the methodological concerns about whether dichotomous or continuous measurements are more appropriate (Collier and Adcock, 1999; Munck and Synder 2007, p. 476).

2.^ Arab Barometer is a non-partisan research network that has been conducting nationally representative face-to-face public opinion surveys on probability samples across the Arab world since 2006 (Arab Barometer, 2018, p. 14).

3.^ According to Dahl, polyarchy is the regime type closest to ideal democracy.

4.^ This index attempts to measure “(a) whether the chief executive is elected, either directly elected through popular elections or indirectly through a popularly elected legislature that then appoints the chief executive; and (b) whether the legislature, in presidential systems with a directly elected president that is also chief executive, is directly or indirectly elected” (V-Dem Codebook v.13, p. 52).

5.^ The liberal principle of democracy emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights. It focuses on factors such as constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances (V-Dem Codebook v.13, p. 54).

6.^ “Government ensures job opportunities for all” option is more popular among the youngest cohort (36%) in comparison to other cohorts (35.1%) in aggregated scores.

7.^ Arab Barometer (2018, Wave V) asked respondents whether they agree, disagree, strongly agree or strongly disagree with the statement “Religious practice is a private matter and should be separated from socio-economic life.” The percentage of Arab citizens who strongly agree with this statement and associate democracy with government ensuring jobs is 39%. The percentage of Arab citizens who strongly disagree with this statement and associate democracy with government ensuring jobs is 32%.

8.^ This model, to a certain extent, resembles the “consensus” transition dynamic in South Africa where majority control secured black South Africans their rights and liberties (Riedl, 2022, p. 110–115).

9.^ East Asian countries have limited resource-derived rents, which removed a source of conflict over state control and contributed to political stability. Furthermore, in East Asian countries corruption has been concentrated at the top echelon of power while decisions were implemented by a competent state bureaucracy (Noland and Pack, 2008, p. 95–96). Therefore, it may not be possible for Arab republics to obtain levels of growth under ongoing corruption like the success of East Asian countries.

10.^ I exclude Algeria, as Islamists’ victory in 1994 election’s initial round led to a brutal civil war.

11.^ According to a widely recognized definition, a tribe is a “localized group in which kinship is the dominant idiom of organization, and whose members consider themselves culturally distinct (Tapper, 1983, p. 9).”

12.^ In some country settings, such as Iraq, tribe is incorporated into the formal political structure (Choucair-Vizoso, 2023). In others, such as Yemen, tribes consider their territories “state within the state” and are willing to employ their authority to enforce their rule, including through physical force (Phillips, 2023, p. 908).

13.^ For instance, Arab Barometer survey research (Wave VII, 2021–2022) indicates significant ethnic variation in a diverse set of countries such as Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia and Iraq.

References

1

Abrams E. (2017). Realism and democracy: American foreign policy after the Arab spring. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2

Acemoglu D. Robinson J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Surry Hills, NSW: Currency Press.

3

Anderson L. (2006). Searching where the light shines: studying democratization in the Middle East. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.9, 189–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.072004.095345

4

Arab Barometer (2018). Arab barometer wave V. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

5

Boix C. Stokes S. C. (2003). Endogenous democratization. World Polit.55, 517–549. doi: 10.1353/wp.2003.0019

6

Brancati D. (2014). Pocketbook protests: explaining the emergence of pro-democracy protests worldwide. Comp. Pol. Stud.47, 1503–1530. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512603

7

Brunkert L. Kruse S. Welzel C. (2019). A tale of culture-bound regime evolution: the centennial democratic trend and its recent reversal. Democratization26, 422–443. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1542430

8

Cammett M. Diwan I. Heydemann S. (2023). “The political economy of development in the Middle East” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 115–129.

9

Carkoglu A. Krouwel A. Yıldırım K. (2019). Party competition in the Middle East: spatial competition in the post-Arab spring era. Br. J. Middle East. Stud.46, 440–463. doi: 10.1080/13530194.2018.1424620

10

Carothers T. (2002). The end of the transition paradigm. J. Democr.13, 5–21. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0003

11

Cheibub J. A. Gandhi J. Vreeland J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice143, 67–101. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2

12

Choucair-Vizoso J. (2023). “Iraq” in The middle east. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 471–501.

13

Clark J. A. (2018). Local politics in Jordan and Morocco: Strategies of centralization and decentralization. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

14

Collier D. Adcock R. (1999). Democracy and dichotomies: a pragmatic approach to choices about concepts. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.2, 537–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.537

15

Collier D. Levitsky S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Polit.49, 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

16

Coppedge M. Gerring J. Knutsen C. H. Lindberg S. I. Teorell J. Altman D. et al . (2023). “V-Dem codebook v13” varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute.

17

Dahl R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: participation and opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

18

Dalacoura K. (2012). The 2011 uprisings in the Arab Middle East: political change and geopolitical implications. Int. Aff.88, 63–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01057.x

19

De Miguel C. Jamal A. A. Tessler M. (2015). Elections in the Arab world: why do citizens turn out?Comp. Pol. Stud.48, 1355–1388. doi: 10.1177/0010414015574877

20

Diamond L. Lipset S. M. Linz J. (1987). Building and sustaining democratic government in developing countries: some tentative findings. World Affairs150, 5–19.

21

Easterly W. (2014). The tyranny of experts: Economists, dictators, and the forgotten rights of the poor. New York: Basic Books.

22

Finkel S. E. Pérez-Liñán A. Seligson M. A. (2007). The effects of US foreign assistance on democracy building, 1990–2003. World Polit.59, 404–439. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100020876

23

Galal A. (2008). “Comparative assessment of industrial policy in selected MENA countries: an overview” in Industrial policy in the Middle East and Africa. ed. GalalA.. 1st ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–11.

24

Haggard S. Kaufman R. R. (2016). Democratization during the third wave. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.19, 125–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042114-015137

25

Hamid S. (2011). The struggle for Middle East democracy. Cairo Rev. Glob. Affairs23, 18–29.

26

Hamid S. (2022). The problem of democracy: America, the Middle East, and the rise and fall of an idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

27

Helliwell J. F. (1994). Empirical linkages between democracy and economic growth. Br. J. Polit. Sci.24, 225–248. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400009790

28

King S. J. (2009). The new authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

29

Lee R. Shitrit L. B. (2023). “Religion, society and politics in the Middle East” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 197–231.

30

Levitsky S. Way L. A. (2006). Linkage versus leverage. Rethinking the international dimension of regime change. Comp. Polit.38, 379–400. doi: 10.2307/20434008

31

Lupu N. Riedl R. B. (2013). Political parties and uncertainty in developing democracies. Comp. Pol. Stud.46, 1339–1365. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453445

32

Lust E. (2023). “States and institutions” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 155–197.

33

Mainwaring S. (2022). “Why democracies survive in hard places” in Democracy in hard places. eds. MainwaringS.MasoudT.. 1st ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 228–269.

34

Mainwaring S. Brinks D. Pérez-Liñán A. (2007). “Classifying political regimes in Latin America, 1945–2004” in Regimes and democracy in Latin America: Theories and methods. ed. MunckG. L. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

35

Masoud T. (2023). “Egypt” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 403–442.

36

Mazzuca S. L. Munck G. L. (2014). State or democracy first? Alternative perspectives on the state-democracy nexus. Democratization21, 1221–1243.

37

Munck G. L. Snyder R. (2007). Passion, craft, and method in comparative politics. Baltimore: JHU Press.

38

Mutlu B. E. Yasun S. (2024). Weak party system institutionalization and autocratization: evidence from Tunisia. Democratization, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2024.2376633

39

Nabli M. K. Keller J. Nabli M. K. Nassif C. Silva-Jauregui C. (2008). “The political economy of industrial policy in the Middle East and North Africa” in Industrial policy in the Middle East and Africa. ed. GalalA.. 1st ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 109–137.

40

Nabli M. K. Nugent J. B. (2023). Tunisia's economic development: Why better than most of the Middle East but not East Asia. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

41

Noland M. Pack H. (2008). “The east Asian industrial policy experience” in Industrial policy in the Middle East and Africa. ed. GalalA.. 1st ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 81–109.

42

O'Donnell G. (1993). On the state, democratization and some conceptual problems: a Latin American view with glances at some Postcommunist countries. World Dev.21, 1355–1369. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(93)90048-E

43

Phillips S. G. (2023). “Yemen” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 893–907.

44

Przeworski A. Limongi F. (1993). Political regimes and economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 7, 51–69.

45

Przeworski A. (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

46

Ridge H. M. (2022). Dismantling new democracies: the case of Tunisia. Democratization29, 1539–1556. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2022.2093346

47

Ridge H. M. (2023). Wasta and democratic attitudes in the Middle East. Middle East Law Govern.1, 1–27. doi: 10.1163/18763375-20231409

48

Riedl R. B. (2022). “Africa’s democratic outliers: success amid challenges in Benin and South Africa” in Democracy in hard places. eds. MainwaringS.MasoudT.. 1st ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 94–127.

49

Robinson J. A. (2006). Economic development and democracy. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.9, 503–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.092704.171256

50

Rueschemeyer D. Stephens E. H. Stephens J. D. (1992). Capitalist development and democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

51

Russell B. (1945). A history of Western philosophy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

52

Sadiki L. Saleh L. (2023). Crisis of democratisation in the Maghreb and North Africa. J. North Afr. Stud.28, 1317–1323. doi: 10.1080/13629387.2023.2207225

53

Salem M. B. (2020). “God loves the rich.” the economic policy of Ennahda: liberalism in the Service of Social Solidarity. Pol. Rel.13, 695–718. doi: 10.1017/S1755048320000279

54

Salloukh B. F. Barakat R. Al-Habbal J. S. Khattab L. W. Mikaelian S. (2015). The politics of sectarianism in postwar Lebanon. Chicago: Pluto Press.

55

Sartori G. (1970). Concept Misformation in comparative politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.64, 1033–1053. doi: 10.2307/1958356

56

Schedler A. (1998). What is democratic consolidation?J. Democr.9, 91–107. doi: 10.1353/jod.1998.0030

57

Schedler A. Sarsfield R. (2007). Democrats with adjectives: linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. Eur J Polit Res46, 637–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00708.x

58

Snider E. A. (2022). Marketing democracy: The political economy of democracy aid in the Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

59

Souilmi H. (2023). A tale of two exceptions: everyday politics of democratic backsliding in Tunisia. J. North Afr. Stud.28, 1425–1443. doi: 10.1080/13629387.2023.2207226

60

Svolik M. W. (2019). Polarization versus democracy. J. Democr.30, 20–32. doi: 10.1353/jod.2019.0039

61

Tansey O. Koehler K. Schmotz A. (2017). Ties to the rest: autocratic linkages and regime survival. Comp. Pol. Stud.50, 1221–1254. doi: 10.1177/0010414016666859

62

Tapper R. (1983). The Conflict of Tribe and State in Iran and Afghanistan (London: Croom Helm, 1983), p.4.

63

Tessler M. (2011). Public opinion in the Middle East: Survey research and the political orientations of ordinary citizens. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

64

Wien P. (2021). Tribes and tribalism in the modern Middle East: introduction. Int. J. Middle East Stud.53, 471–472. doi: 10.1017/S002074382100074X

65

Yerkes S. (2023). US democracy promotion in the Maghreb: much ventured, little gained. J. North Afr. Stud.28, 1345–1372. doi: 10.1080/13629387.2023.2203467

66

Yildirim A. K. (2016). Muslim democratic parties in the Middle East: Economy and politics of Islamist moderation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

67

Zerhouni S. Maghraoui D. (2023). “Morocco” in The Middle East. ed. LustE.. 16th ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 669–695.

Summary

Keywords

democratization, development, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), institutions, Islamism and democratization

Citation

Yasun S (2024) Democracy with adjectives? Economic development and democracy in the Middle East. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1414973. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1414973

Received

09 April 2024

Accepted

12 August 2024

Published

29 August 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Ilia Murtazashvili, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Reviewed by

Syeda Naushin, University of Malaya, Malaysia

Pablo Paniagua, King’s College London, United Kingdom

Hannah Ridge, Chapman University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Yasun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Salih Yasun, yasuns@vmi.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.