- Department of Assembly of People of Kazakhstan, Faculty of International Relations, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, Kazakhstan

Introduction: The aim of this study is to characterize the migration interaction between Kazakhstan and the Central Asian countries, as well as the Kazakh diaspora within them. To achieve this objective, key aspects of Kazakhstan’s new migration policy, as reflected in national legislation, were identified, as well as gaps in the new Migration Policy Concept of Kazakhstan.

Methods: Using statistical data from national statistical institutions, the World Bank, and the “Otandastar Fund” Society, the Kazakh diaspora was characterized in terms of its quantitative representation in each of the Central Asian countries. The relationship between the diaspora and the national population, as well as other diasporas, was analyzed, including the proportion of the Kazakh diaspora within the regional (Central Asian countries) and global context. Based on the analysis of official information from Kazakhstan’s diplomatic missions, the main areas of work with the Kazakh diaspora in each of the countries in the region were identified.

Results and discussion: It was shown that, despite a significant historical, ethnic, and mental commonality, migration processes between Kazakhstan and each of the Central Asian countries have their peculiarities. The activities of the diasporas and the organization of their interaction with the country of origin also have significant differences, as do the reasons for the decline in the Kazakh diaspora’s numbers in certain Central Asian countries. The modern development of international relations necessitates a revision of the concept of diaspora by adding additional characteristics to the ethnic component, allowing people from one country of origin to unite not only based on co-residence in another state but also through non-territorial association aimed at supporting the country of origin, particularly in scientific, business, economics and socially useful interests. The results of this study can form the basis for national laws, concepts, and programs in the field of migration and cooperation with the Kazakh diaspora in the Central Asian region, as well as for practical activities in this area.

1 Introduction

The voluntary or forced relocation of representatives of various peoples to new territories is an integral part of human life. By uniting in these territories for more successful adaptation and survival, such migration groups serve as a supporting resource for newcomers, an informal link between the host country and the country of national affiliation of the diaspora members or their ancestors, and may also become a subject capable of exerting influence on the host territory. This preservation and development of social ties by migrants that extend beyond the borders of the host country is defined as transnationalism (Rosenberg et al., 2016). In most cases, these will be ties with the country of origin, which, under conditions of expanding communication capabilities, are becoming an increasingly natural process. At the same time, such interaction and influence can be more or less successful, depending on a range of factors, including the size of the diaspora, its organization, and the initiative of its members. The more organized the diaspora is, the greater impact it has on the most important aspects of the lives of both its members and the host country, and the greater the reserve it represents for the country of origin. In the 21st century, diasporas are viewed as important actors in international relations between the country of origin and the host country, serving as an effective tool of “soft power” (Khama, 2020). From a political perspective, large diasporas are seen as capable of altering the balance of influence in global politics (Adamson and Han, 2024). This underscores the recognition of the role of diasporas at the international level, as one of the factors ensuring the achievement of the UN’s sustainable development goals (IOM, 2022). This approach is largely determined by the fact that the diaspora is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses not only political, but also social, cultural, humanitarian, anthropological, and other aspects (Dijkzeul and Fauser, 2024).

The concept of diaspora does not have a single definition. Originally, the word “diaspora” is of Greek origin and means “scattering,” and when applied to populations, it refers to a part of the population consisting of individuals from other countries (IOM, 2020). To explain its meaning, terms such as transnational communities are used, referring to groups of migrants and their descendants, highlighting key characteristics such as their presence in a country different from their country of origin, the maintenance of internal community ties, national identity or the identity of the country of origin (Grossman, 2019), the desire to preserve national identity, and maintain connections with the country of origin (Diasporas, 2024). Given that Kazakhstan’s population is ethnically diverse, with Kazakhs constituting an absolute majority (71%), it is important to distinguish between the terms “Kazakh diaspora” (based on ethnicity) and “Kazakhstan diaspora” (based on the country of origin) when discussing diasporas in Central Asian countries. The formation of diasporas is a direct result of population migration. At the same time, data on global migration is rather contradictory. Statistical data shows that, on a global scale, the number of migrants cannot be considered critical, as it represents about 3.6% of the total world population (IOM, 2024b). Therefore, it can be argued that most people prefer to live in their country of origin, with only one in thirty being a migrant. However, when considering this issue in dynamic terms, it is important to note that the number of migrants increased by 128 million from 1990 to 2020 (IOM, 2024b), indicating a steady upward trend. There is also a trend towards increasing gender imbalance, with a larger proportion of male migrants. At the same time, international remittance statistics show an increase in transfers between individuals linked by family or kinship ties, suggesting that labor migration is the main type of migration. It is also noteworthy that Europe and Asia continue to hold a dominant position as host regions, with approximately 61% of all migrants residing in these regions (IOM, 2024b). Central Asia, however, is characterized as a unique region in terms of migration processes. An important factor in the characterization of migration flows is the location of Central Asian countries along the so-called Silk Road. Historically, this region has served as a link between Europe and Asia, which led to the presence of a significant number of international migrants on its territory. However, beyond regional boundaries, Central Asian countries are largely countries of origin for host countries in other regions (Migration Data Portal, 2024).

When discussing the regional specifics of Kazakhstan and Central Asian countries as a whole, it is important to highlight the similarities in the causes of migration flows during their time within the unified political space of the former USSR and after its dissolution (EU DIF, 2024). During the Soviet period, one of the main causes of migration was the internal national policy of the USSR, which was essentially aimed at eradicating the national identities of the peoples of the union republics, followed by the socio-economic crisis of the 1990s that emerged after the dissolution of the USSR (Eschment and De Cordier, 2021). It should be noted that Kazakhstan’s independence not only influenced migration flows but also led to changes in the organization of interactions with Kazakh diasporas, which had primarily positive manifestations in the form of expanded cooperation aimed at supporting the diaspora’s efforts to preserve the national identity of its members, promote Kazakh culture in the host country, and encourage the study of the Kazakh language (Global Forum on Migration and Development, 2010). This interaction plays an important role for Kazakhstan itself, as the Kazakh diaspora, according to Forbes, is one of the largest global diasporas (Buchholz, 2022). In 2024, the number of Kazakh diaspora members worldwide, according to official data, exceeded 3 million people, while unofficial data suggests the number could be as high as four and a half million (The Astana Times, 2024). Thus, today, the task of restoring and developing national identity is a top priority among the tasks aimed at ensuring Kazakhstan’s national security. At the same time, the issue of repatriation often does not receive unequivocally positive responses from diaspora members (Shuval, 2000), even though, since gaining independence, repatriation policy has been one of the priority areas of Kazakhstan’s national policy (IOM, 2022). The preservation of national identity and globalization act as two opposing forces on the global stage. However, diasporas, gradually increasing their significance and influence in the field of international relations, are important actors capable of uniting both of these trends. Simultaneously, in the context of globalization, not only individual countries but also ethnically similar regions, sharing common political and economic interests while united by a shared history, cultural traditions, and mentality, play a significant role. The study presented in this article aims to characterize the regional migration processes involving Kazakhstan in the Central Asian region and to assess Kazakhstan’s interaction with the corresponding regional Kazakh diasporas, which represents an important step in understanding the role of the Kazakh diaspora as a whole.

1.1 Literature review

The analysis of academic literature dedicated to diaspora issues allows for the identification of several blocks that address different aspects of this phenomenon. The first aspect concerns the causes of migration processes and, as a consequence, the grouping of people based on their country of origin or that of their ancestors. In the context of globalization, populations are highly responsive to political, economic, and other changes that compel them to seek more comfortable living conditions, making migration policy inherently dynamic. The more unstable the domestic or global situation, the greater its influence on migration flows, necessitating a more timely and adequate response from government authorities. Depending on the orientation of this response, internal and external migration policies differ (Niemann and Zaun, 2023). The consequences of migration processes are also directly related to their causes, which determine the types of migration. The primary categories of migration include economic migration, which is largely voluntary, and humanitarian migration, which is forced and driven by events in the country of origin that prevent normal living conditions, such as armed conflict (Garcia-Zamor, 2017). Specifically, the reasons for migration often determine whether it is temporary or permanent in nature (Klingner, 2020). Although migration policy is an integral and important component of any state’s policy, it is often limited in its ability to influence the underlying causes of migration, although it can guide migration flows (Solano and Huddleston, 2022).

The formation of diasporas as a consequence of migration is characterized as a phenomenon with a more or less permanent nature. The primary focus of diaspora activities is to provide help and support to its members, including newcomers, which becomes particularly relevant in crisis situations, as migrants’ access to social protection institutions is often limited (Sebakwiye and Bidandi, 2024). When a diaspora reaches a sufficiently high level of internal organization, it transitions to a new stage of existence, becoming an independent actor influencing the host country (Bekzhanova et al., 2022). At the same time, the activities of a diaspora cannot be considered effective if they are limited to socio-political and economic engagement in the host country. The preservation of national identity requires maintaining effective links with the country of origin. There is mutual interest in this, as the country of origin may not only gain a reliable and effective partner in the diaspora for implementing “soft power” policies but also for addressing internal challenges. As noted in academic literature, a significant aspect of the state’s work with diasporas is encouraging the return of emigrants to their homeland, as people are the primary resource for any state. The repatriation of diaspora members, when possible, requires a multifaceted approach that addresses international legal and social aspects (Baizhuma et al., 2021). At the same time, such cooperation helps establish a global system of national interaction (Karassayev et al., 2022). This aspect is particularly important for Kazakhstan, where the pressing issue is ensuring internal stability amidst the diversity of ethnic groups residing on its territory. For example, concerns arise over the prevalence of Russian populations in certain regions in combination with Russia’s demands for their autonomy (Kumar, 2021). Addressing demographic issues through the stimulation of incoming migration flows is a common global practice (Green and Kadoya, 2015), but in order to preserve national identity, ensure national security, and strengthen the economy, the repatriation of indigenous populations and the engagement of the diaspora from among compatriots are critical. Kazakhstan’s migration policy is primarily focused on repatriation, as it enables the problem of ensuring the dominance of the titular population to be addressed in the shortest possible time. However, the issues of interaction with the Kazakh diaspora that has emigrated abroad since independence and the involvement of this diaspora in Kazakhstan remain unresolved.

The issue of Kazakh involvement in migration processes can be considered a distinct area of research related to migration studies and the role of diasporas. Notable steps already taken in this regard include studies focused on Kazakh migrants worldwide (Karassayev et al., 2022), the concept and role of Kazakh diasporas globally (Askhat, 2020), and research addressing Kazakhstan’s relations with other Central Asian countries as a whole (Karassayev et al., 2023). Thus, contemporary academic literature primarily focuses on general issues related to the causes, consequences, and potential influence on migration, as well as the role of diasporas in organizing cooperation with their countries of origin and their possible impact on the host country. However, the examination of migration issues and the specifics of diasporas from a regional perspective, particularly concerning ethnically related peoples such as those of Central Asia—who share geographically and geopolitically similar goals and have close economic and cultural ties—remains underexplored. Conducting research focused on the migration interaction between Kazakhstan and the Central Asian countries, as well as the Kazakh diaspora within them, is therefore a logical continuation of this research direction.

1.2 Problem statement

Migration is a logical response of populations to changes in living conditions. At the same time, the desire to preserve national identity, the need for communication, and the necessity of assistance in adapting to new environments lead to the formation of diasporas. In the modern world, the role of diasporas extends beyond merely enhancing the social adaptation of their members. Upon reaching a certain level of organization, a diaspora can become an autonomous actor both in the life of the host country and as a partner to the country of origin in addressing foreign policy objectives. Thus, the issue of interaction, cooperation, and mutual support should be considered a critical aspect of migration policy. Furthermore, migration policy can be examined both from a global and regional perspective, the latter being equally important as it reflects the details of ethnicities, mentalities, cultures, and languages within a region.

The goal of this research is to identify the features and assess the migration regional policy of Kazakhstan in the Central Asian region, as well as to characterize the Kazakh diaspora and the organization of interaction with it by the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The research framework involves the sequential resolution of the following tasks:

• Define the approaches to external migration policy in the Republic of Kazakhstan.

• Using quantitative indicators, determine the proportion of the Kazakh population in the Central Asian countries.

• Analyze the composition, activity, and development trends of Kazakh diasporas in individual Central Asian countries, and their interaction with the country of origin (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan).

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Conceptual basis of research

The formation of diasporas is not merely a consequence of migration flows but also reflects their prolonged historical nature. It is inseparable from migration processes, and the inevitability of the latter underscores the necessity of considering migration issues and the formation and activities of diasporas in tandem. Such an examination at the regional level allows for an assessment of the regional significance of individual entities within the region, their regional influence, as well as the identification of issues related to the determination of economic and social attractiveness and the role of these factors in shaping migration flows. This has determined the structure of the study, which includes questions aimed both at exploring migration policy and migration causes, as well as the features and role of the Kazakh diaspora in preserving national identity and in the sphere of institutional influence within the region.

2.2 Methodological research design

The study consisted of three stages, each aimed at addressing one of the tasks, which, in turn, contributed to the overall achievement of the research objective.

The first stage of the study focused on the task of characterizing Kazakhstan’s policy. A general characterization of the policy of interaction with the diaspora, as reflected in national migration legislation, is a crucial step in understanding the goals Kazakhstan sets in the field of migration at the current stage. This provides a basis for further evaluation of how well the regional migration policy aligns with these goals, as well as how interaction with Kazakh diasporas in the region is organized. This is due to the modern role of diasporas as influential actors in the politics and economy of the host country, as well as their potential role as partners for the country of origin in building relationships with the host country and developing political and economic ties, which effectively makes them instruments of “soft power.” The analysis was based on the following key documents: the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Population Migration” (Reference Control Bank of Normative Legal Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2002), the Concept of Migration Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2027 (Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022), and the National Development Plan of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2029 (Adilet, 2024).

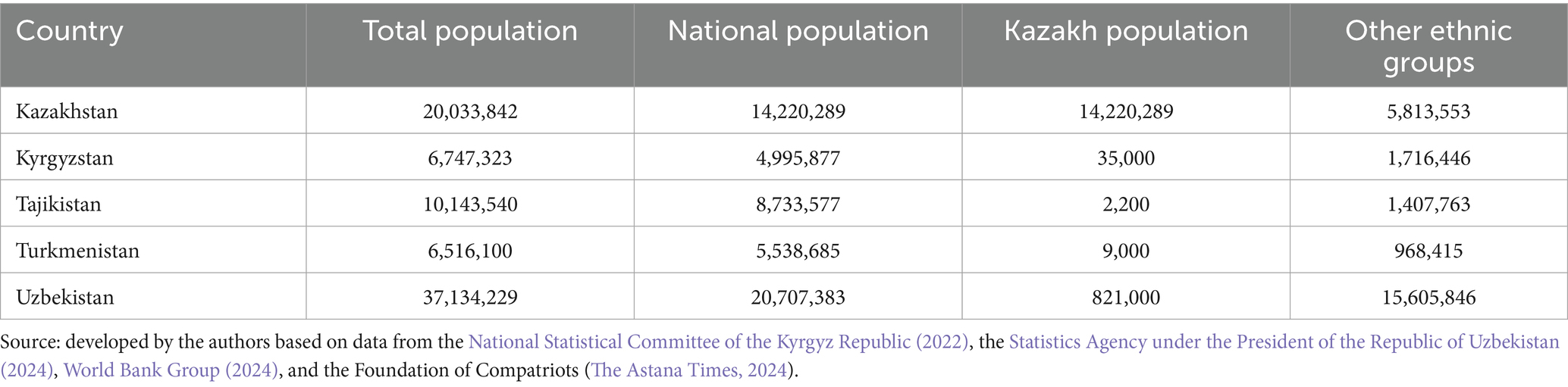

The second stage of the study focused on the demographic characterization of the region, specifically regarding the representation of Kazakh populations in each of the countries. At this stage, statistical data from sources such as the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (2022), the Statistics Agency under the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2024), the World Bank Group (2024), and the “Otandastar” Foundation (The Astana Times, 2024) were utilized. The evaluation included a comparison and characterization of data concerning the proportion of the national population in the Republic of Kazakhstan, the size of the Kazakh diaspora worldwide, and in the region, as well as the share of the Kazakh population in each of the countries in the region. Additionally, the ratio of the Kazakh population (size of the Kazakh diaspora) relative to the national population and other diasporas was assessed.

The third stage involved determining the role of the diaspora in the life of both the host country and the country of origin. To this end, data from the report “Return Migration” (IOM, 2020) were used. Further research was conducted on the activities of the Kazakh diaspora in Central Asian countries and the work of the Republic of Kazakhstan with its diaspora. For identifying key projects, the analytical report from the Strategic Development Center (2021) was used. Additionally, based on data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Kazakhstan (2024), the embassies of the Republic of Kazakhstan in Central Asian countries (Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Republic of Uzbekistan, 2024), and independent sources (Lahanuly, 2017), the possibility of preserving national culture, identity, and the study of the Kazakh language in each of the countries in the region was explored. This allowed for an assessment of the opportunities available to Kazakh populations that support the preservation of national identity and readiness for repatriation, conclusions regarding the influence of the Kazakh diaspora in each region, the formulation of preliminary recommendations, and the identification of directions for future research.

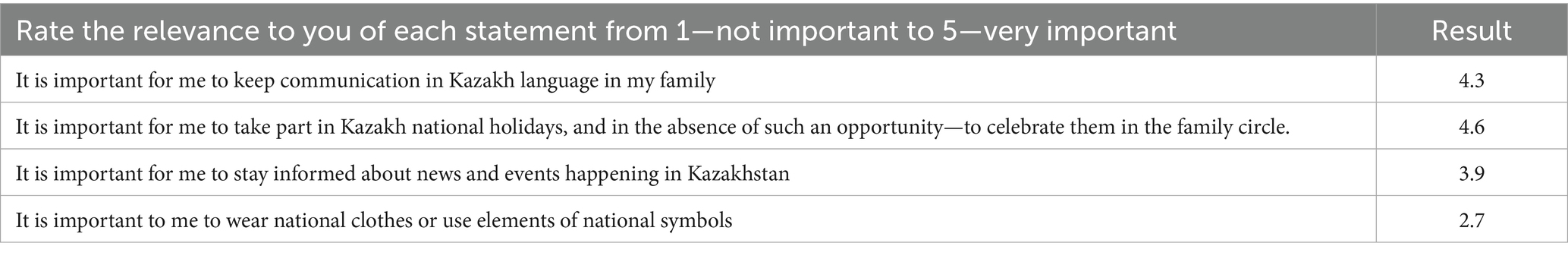

The fourth stage of the research consisted in conducting a questionnaire survey of ethnic Kazakhs and citizens of Kazakhstan living in Kyrgyzstan. The sample included 100 respondents. The purpose of the questionnaire was defined as the collection of primary quantitative and qualitative data to determine: the aspiration of respondents to preserve their national identity and their assessment of the effectiveness of state and non-state structures that provide assistance to Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan. The questionnaire was distributed via messengers, participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary.

The fifth stage of the research included the analysis of press materials for 2023–2024, devoted to the issues of organisation of work in the sphere of cooperation with the Kazakh diaspora of representatives of various institutions of Kazakhstan.

2.3 Research materials

The study was conducted using materials from open sources. These included regulatory and legal acts in the migration sector of the Republic of Kazakhstan (such as the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Population Migration” and the Concept of Migration Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2027), reports on the activities of the embassies of the Republic of Kazakhstan regarding their interaction with the Kazakh diaspora in Central Asian countries (Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Republic of Uzbekistan, 2024; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024), and official information from the Central Communications Service under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Central Communicate Service under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024). Official statistical data on migration were also utilized from the Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2024c), the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (2022), and the Statistics Agency under the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2024). Additionally, data from the analytical report of the Strategic Development Center of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Strategic Development Center, 2021), the “Return Migration” report (IOM, 2020), and reports from international institutions (IOM, 2024b; Migration Data Portal, 2024; World Bank Group, 2024) were also incorporated into the research, results of the questionnaire survey of representatives of ethnic Kazakhs and Kazakh citizens living in Kyrgyzstan; press materials for 2023–2024 regarding the institutional influence of Kazakhstan’s state structures on the Kazakh diaspora (DKN World News, 2024; Sattarov, 2022; The Astana Times, 2023).

2.4 Methodological tools

The study involved an analysis of the regulatory and programmatic documents of the Republic of Kazakhstan, identifying trends and gaps in the country’s work with the Kazakh diaspora. A demographic model of the Central Asian countries was developed to demonstrate the representation of the Kazakh diaspora in each of these countries, in quantitative relation to the national population and other diasporas. The research included an analysis of the functioning of specialized cultural institutions whose activities focus on supporting and promoting Kazakh culture, as well as an assessment of educational opportunities for Kazakh youth in Central Asian countries, specifically in terms of the possibility of studying national history, language, and culture, thereby contributing to the preservation of national identity.

2.5 Methodological limitations

Official and unofficial data regarding the size of the Kazakh diaspora exhibit some discrepancies. Furthermore, the size of the Kazakh diaspora fluctuates due to the active efforts of the government of the Republic of Kazakhstan aimed at enhancing the repatriation process. However, this does not significantly affect the percentage ratio between the Kazakh diaspora and the national population of the countries in the region, nor the size of other diasporas, which sufficiently reflects the overall distribution of Kazakhs across the Central Asian countries.

The distinction made in this study between the “Kazakhstani” and “Kazakh” diasporas remains a theoretical observation requiring further research, as the available statistical data do not allow for a characterization of the diaspora based on this criterion. Therefore, the term “Kazakh diaspora” used in this study does not exclude the possibility that individuals of other nationalities, whose country of origin is Kazakhstan, may be part of it.

3 Results

3.1 Migration policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan during the period of gaining independence

The preservation of national identity and the increase in the indigenous population are essential means of ensuring stable development, economic growth, and, ultimately, national security for any state. The national policy implemented by the former USSR, aimed at suppressing national identities, and the interethnic conflicts and economic crisis of the 1990s, led to massive emigration from the national republics. One of the foundational principles of the migration policy of independent Kazakhstan has been to encourage the return of members of the Kazakh diaspora to their country of origin. This approach is reflected in the national legislative framework on migration, with its core provisions outlined in the Reference Control Bank of Normative Legal Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2002). A key feature of this law, designed to facilitate the repatriation of Kazakhs, is the introduction of a special status—the “oralman” status (later clarified and replaced by the term “kandas”)—which guarantees support from the state for individuals moving to Kazakhstan for permanent residence. The conditions for obtaining this status include Kazakh ethnicity and residence outside Kazakhstan at the time of the country’s independence. This applies to both foreigners and stateless individuals. The law provides for measures to ensure employment for returning Kazakhs and the provision of social assistance. A separate law establishes quotas related to this, which are mandatory for all entities and organizations, regardless of ownership. The law also distinguishes between family and collective immigration, as well as individual immigration.

Further measures in the field of migration policy were outlined in the Concept of Migration Policy of Kazakhstan for the period until 2027, adopted in 2022 (Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022). When examining the migration situation in the country, the Concept identifies three main periods, the first of which (1991–2000) is characterized by a population outflow and a worsening demographic crisis. The primary migration corridor remains the Kazakhstan-Russia route (IOM, 2024b). However, it is worth noting that, on a global scale, Kazakhstan does not rank among the top 10 countries with the highest level of remittances within a single family (IOM, 2024b). This suggests that, despite certain economic challenges that encourage labor migration, they are not systemic enough to lead to a mass population exodus.

The government has implemented several measures aimed at stabilizing the situation, including a state program designed to support the Kazakh diaspora. Between 2001 and 2010, a positive trend in migration flows and favorable ethnic repatriation was observed, which was linked to an increase in Kazakhstan’s economic attractiveness. However, between 2011 and 2022 (the third period), negative migration flows once again prevailed. Moreover, more than a third of emigrants are of working age and possess higher or specialized technical education (Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022).

The issue of the return of the national population to their country of origin is a key component of Kazakhstan’s policy. This provision is not only declarative but is also supported by national programs aimed at assisting the repatriation of the Kazakh diaspora. One can speak of the state creating a foundation for working with these relevant diasporas, aimed at stimulating reverse migration. The continuity of this policy is reflected in the Concept of Migration Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2027, adopted in 2022. However, while acknowledging the government’s consistent efforts to stimulate reverse migration processes, it should be noted that the Concept does not consider the role of diasporas as influential actors in migration policy. The developers of such an important policy document as the Concept overlooked the issue of organizing cooperation with diasporas, which represents a significant gap in the formulation of tasks aimed at stimulating reverse migration. Additionally, the planning of migration policy and diaspora engagement cannot ignore changes in global politics and, therefore, requires flexible responses to shifts in the international situation.

An important aspect of repatriation, migration, and cooperation with diasporas is the consideration of the demographic characteristics of repatriates and emigrants. It is noteworthy that of the 8,758 ethnic Kazakhs who returned to Kazakhstan and received the status of kandas, the proportion of individuals of pensionable age constitutes a minority (9.9%). The remaining repatriates are predominantly of working age (59%), which can be viewed as a positive trend from the perspective of replenishing Kazakhstan’s population with individuals capable of contributing to the country’s development. At the same time, the educational level of repatriates shows a significant imbalance, with those holding higher education constituting only 17%. This situation could be rectified by placing greater emphasis on further professional training for minors among the repatriates, who represent 31.1% of the total (Central Communicate Service under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024). Simultaneously, the process of emigration is taking place, with the largest group consisting of individuals with higher education. For instance, in 2023, the vast majority of emigrants from Kazakhstan held either higher education (3,849 individuals) or secondary vocational education (3,882 individuals), while those with general or basic secondary education numbered 2,644 and 1,227, respectively (IOM, 2024a).

Thus, when discussing potential improvements to the Concept of Migration Policy, particularly from the perspective of stimulating reverse migration and working with diasporas, attention should be given to increasing the educational level of repatriates and creating attractive economic and career opportunities for highly educated and qualified individuals. If not through their repatriation, then through their involvement in economic, scientific, and other projects that contribute to solving issues related to the development of the national economy, science, and culture. Overall, the policy of engagement with the Kazakh and Kazakhstan diasporas abroad should become more active in harnessing the diaspora’s potential for the socio-economic development of the country of origin, as well as for preserving and strengthening national identity.

3.2 The demographic picture of Central Asian countries in terms of the representation of the Kazakh population

Despite the efforts of the state aimed at stimulating repatriation processes, the issue of emigration and addressing demographic problems through the return of Kazakhs to their homeland remains unresolved. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the population of Kazakhstan, which exceeds 20 million, is made up of more than 72 ethnic groups. Kazakhs constitute the majority, exceeding 14 million people (Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024b). As of 2022, between 5 and 7 million Kazakhs live outside Kazakhstan (IOM, 2022). This represents a vast human potential that, regardless of whether the choice is made to return to Kazakhstan or participate in the activities of Kazakh diasporas abroad, can have a significant impact on the development of Kazakhstan. In the countries of the Central Asian region, the Kazakh population is represented as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Total Kazakh population in relation to the total population, national population, and representatives of other ethnic groups in Central Asian countries in 2022–2024.

Thus, the largest number of Kazakhs relative to the total population is found in Uzbekistan (2.2%), followed by Kyrgyzstan (0.52%), Tajikistan (0.21%), and Turkmenistan (0.14%). To better assess the role of the Kazakh diaspora, the ratio of Kazakhs to representatives of other nationalities, excluding the national population, is more informative. In this regard, Uzbekistan’s indicator is 5%, Kyrgyzstan’s is 2%, Tajikistan’s is 0.16%, and Turkmenistan’s is 0.9%. Based on the data presented in Table 1, it can be concluded that these figures for Central Asia are relatively low. This situation is explained by data from the Migration Portal, which shows two main trends in Central Asian countries. First, Russia is the primary destination for migrants from Central Asia (63%). Second, within the Central Asian region, Kazakhstan primarily functions as a receiving country (Migration Data Portal, 2024).

At the same time, of the aforementioned 5 to 7 million Kazakhs living abroad (IOM, 2022), around 867,200 Kazakhs reside in Central Asian countries, which accounts for 12.4 to 17.2%. In theoretical terms, this represents a significant potential within the broader Kazakh diaspora. However, practical assessment of the Kazakh diaspora’s potential faces challenges due to the lack of reliable data. As noted in the report by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the lack of data on labor migrants who have left Kazakhstan makes such an assessment difficult, as a considerable number of them do not list employment as the primary purpose of their departure and often fail to register with consular services.

As an indirect indicator for evaluating the role of labor migrants from Kazakhstan (regardless of ethnic affiliation, meaning migrants from Kazakhstan, not specifically Kazakh migrants), the volume of remittances sent to Kazakhstan by individuals can be used. For instance, in the first quarter of 2023, Uzbekistan had the highest volume of remittances among Central Asian countries, followed by Kyrgyzstan (IOM, 2023a, 2023b).

The quantitative characteristics of the Kazakh diaspora highlight several fundamentally important features. First, the total number of Kazakhs in the global diaspora (5–7 million people) represents a population size that accounts for one-third to nearly half of Kazakhstan’s own Kazakh population (20,033,842 people in 2024). This potential, regardless of the intentions to return to the country of origin, cannot be ignored. Specifically, achieving sustainable development goals requires more active engagement with the Kazakh diaspora in areas such as investment, knowledge exchange, and cooperation in sectors that are considered critical at the national level, including digital technologies, innovation, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and cybersecurity.

An important aspect is the improvement of the situation in science and education, especially in terms of the connection between theory and practice, alignment with international standards, and internationalization, which necessitates the expansion of partnership programs. Special attention is given to attracting investors for the development of production sectors within the national economy, as well as increasing the number of export markets. The Kazakh diaspora could play a significant role in promoting Kazakh products in the markets of host countries. The tourism industry, with its significant economic and cultural potential, is another key area. However, the number of foreign tourists remains low, with about 90% of them coming from countries bordering Kazakhstan. Expanding target markets requires not only the improvement of local tourism infrastructure but also the promotion of Kazakh tourism products in foreign countries, where diaspora support can be particularly effective (Adilet, 2024).

Second, the regional representation of the Kazakh diaspora is quantitatively much smaller compared to the overall number of Kazakh diasporas worldwide. This is a result of Kazakhstan’s role as a receiving country in regional migration processes.

3.3 The Kazakh diaspora as an influence entity in Central Asian countries

The role of the diaspora is twofold: organizing interaction with the host country and organizing interaction with the country of origin of the diaspora members (IOM, 2020). Interaction with the country of origin is one of the key tools for influencing migration flows, particularly regarding repatriation issues, as well as maintaining the national identity of diaspora members and providing support for them. In contrast, interaction with the host country can be viewed as a tool of soft power in influencing bilateral relations between the country of origin and the host country. Thus, the diaspora is an important actor in the political affairs of the country of origin.

One of the characteristics of the Kazakh diaspora is its heterogeneity (Strategic Development Center, 2021). This statement can be fully agreed with, as, since Kazakhstan gained independence, there have been three distinct migration periods, each with its own reasons, contributing to the diaspora’s expansion with members from different backgrounds. The success of the Kazakh diasporas is also determined by their historical and, practically, genetic adaptability to nomadic life, leading to a high degree of adaptability (Strategic Development Center, 2021).

When providing a regional characterization of the Kazakh diaspora, it is important to consider the ethnic, historical, and cultural closeness of the peoples of Central Asia. From an adaptive perspective, this similarity can be seen as a foundation for increasing the diaspora’s potential as an influencing entity. However, when viewed from the perspective of Kazakhstan’s migration policy aimed at repatriating Kazakhs, this similarity reduces the factors supporting reverse migration, leaving only the economic factor and the political situation within the host country as effective. Therefore, increasing the attractiveness of return migration requires additional, consecutive measures by the government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. An important aspect of implementing such measures is their focus not only on Kazakh diasporas in Central Asian countries but also globally. Among the projects aimed at strengthening cultural, economic, educational, and other connections both within the host country and between the diaspora and Kazakhstan are the Qazaq House (Kazakh Cultural and Business House) project and the “Otandastar. Bolashakka Bagdar” project. Both projects share similar activities and are oriented toward developing cooperation with foreign partners in the fields of culture and business. Projects like “Turaq v auly” (focused on supporting repatriates in rural areas) and “Berek” (providing support to repatriates in urban areas) are directed at assisting repatriates (Strategic Development Center, 2021).

The Kazakh diaspora in Central Asian countries is not homogeneous in terms of its numerical composition. As of 2024, the largest Kazakh diaspora remains in the Republic of Uzbekistan. This situation is a historical consequence of the existence of the so-called “Kazakh belt,” formed by nomadic Kazakh tribes, in the northern part of the Republic of Tajikistan (Asia Terra, 2021). When discussing the dynamics of emigration processes, there is a noticeable trend toward a decline.

An important aspect of organizing the life of the Kazakh diaspora in Uzbekistan is the opportunity for Kazakh children to be educated in their native language. According to the Embassy of Kazakhstan, in 2024, there are 370 schools in Uzbekistan offering bilingual education (in Uzbek and Kazakh). More than 20 higher educational institutions in Uzbekistan have included the specialty “Kazakh Language and Literature” at the bachelor’s qualification level in their curricula (Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Republic of Uzbekistan, 2024). Thus, conditions are created and maintained to exert soft influence on the host country, primarily through the promotion of national culture and the development of national educational programs, which allows for influencing the upbringing of the younger generation in accordance with the needs of the country of origin.

It is important to highlight a particular feature of the Kazakh diaspora in Uzbekistan, which largely explains its size: the formation of Kazakh national groups in Uzbekistan as a result of natural historical processes, including those associated with the nomadic lifestyle. At the same time, it is essential not to underestimate the active efforts of both Kazakhstan and the diaspora itself, aimed at maintaining national identity.

The Kyrgyz Republic hosts the second-largest Kazakh diaspora. It is important to once again highlight the significant quantitative gap in the size of the Kazakh diaspora between the Republic of Uzbekistan and the other countries in the Central Asian region. A leading role in organizing interethnic cultural cooperation is played by the Abai Kunanbayev Kazakh Cultural Center. Additionally, in Kyrgyzstan, there is the public organization “Association of Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan” (Kazinform, 2022).

A significant step in the development of policies aimed at expanding educational opportunities for the youth from the Kazakh diaspora, preserving their national identity, and enhancing Kazakhstan’s soft power in the region, was the opening of a branch of the Kazakh National University named after Al-Farabi in the Kyrgyz Republic. The university’s educational program includes the study of the Kazakh language and the history of Kazakhstan (Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2024). It is also noteworthy that in 2024, Kyrgyzstan became one of the top five destination countries for emigrants from Kazakhstan (IOM, 2024b).

The Kazakh diaspora in Turkmenistan is also relatively small (around 9,000 people). However, in the 1990s, the Kazakh diaspora in Turkmenistan numbered up to 120,000 (Lahanuly, 2018). The process of repatriation of ethnic Kazakhs from Turkmenistan continues, with 9.2% of the 21.3 thousand repatriates in 2023 being ethnic Kazakhs (DARYO, 2024). Among the reasons for the mass repatriation are the lack of opportunities to study in the native language and domestic economic problems (Lahanuly, 2018). Additionally, the 2023 human rights review suggests that domestic policies have contributed to the mass departure of Kazakhs from Turkmenistan. Specifically, it notes the absence of positive actions from the Turkmen government to improve the human rights situation, address economic problems, and combat poverty (IOM, 2024b). Nonetheless, the Kazakh authorities are taking measures to organize cooperation with the diaspora, promote, and popularize national traditions and culture (Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in Turkmenistan, 2024). Given the fact that the composition of the Kazakh diaspora in Turkmenistan is aging rapidly (Lahanuly, 2018), an additional area of interaction should be the consideration of providing social assistance to its members.

When characterizing the Kazakh diaspora in the Republic of Tajikistan, it is important to note the significant decline in its size. In the 1990s, its population numbered 70,000, but by 2024, it exceeds only slightly more than 2,000. This outflow of Kazakh migrants was largely driven by the internal instability in Tajikistan (IOM, 2020). According to official data, in 2024, Kazakhstan ranks 15th in Tajikistan’s investment rating; however, there is no evidence linking this ranking to the activities of the Kazakh diaspora or its involvement in stimulating investment processes. The information from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Kazakhstan primarily addresses cultural aspects. Specifically, the Kazakh National Cultural Center “Baiterek” was established in Dushanbe to promote Kazakh culture, and cooperation between higher education institutions of the two countries is being developed (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024).

It is worth noting that, among the Central Asian countries, the Kazakh diaspora in Tajikistan is the smallest. However, its members are engaged in a wide variety of activities, ranging from work in state institutions to agricultural enterprises. This diversity in fields of activity, set against the backdrop of a relatively small overall population, means that the diaspora does not exert significant influence in any one area. Similarly, the sole functioning cultural center, “Baiterek,” does not reach all members of the diaspora. One of the pressing issues facing the Kazakh diaspora in Tajikistan is the younger generation’s lack of proficiency in the native language, as the primary education system does not offer alternatives for learning in Kazakh, restricting instruction to Tajik, Uzbek, and Russian (Lahanuly, 2017). While the opportunity to learn in Russian does provide Kazakh youth in Tajikistan with the possibility of further education at higher institutions in Kazakhstan or the Russian Federation, where education in Russian is also available, or in educational institutions in Tajikistan or Uzbekistan, it does not contribute to the development and preservation of national identity. Moreover, the lack of knowledge of the national language hinders further repatriation and may complicate integration into Kazakh society.

Thus, the regional analysis of migration processes and the functioning of Kazakh diasporas in the countries of Central Asia reveals a significant disproportion not only in the quantitative relationship, with 94.7% of the total Kazakh diaspora residing in Uzbekistan, but also in the approaches to diaspora engagement across the region. This primarily pertains to opportunities for education or, at the very least, the study of the Kazakh language. As the data presented above indicates, effective diaspora-related initiatives are organized only in Uzbekistan, while in the other countries of the region, efforts to maintain national identity are limited to the functioning of cultural centers. Furthermore, it is possible to conclude that historically established diasporas, such as those in the Republic of Uzbekistan, exhibit relative stability, whereas migration processes in the Republic of Turkmenistan are influenced by the economic situation, and in the Republic of Tajikistan, by internal political conditions, as noted earlier.

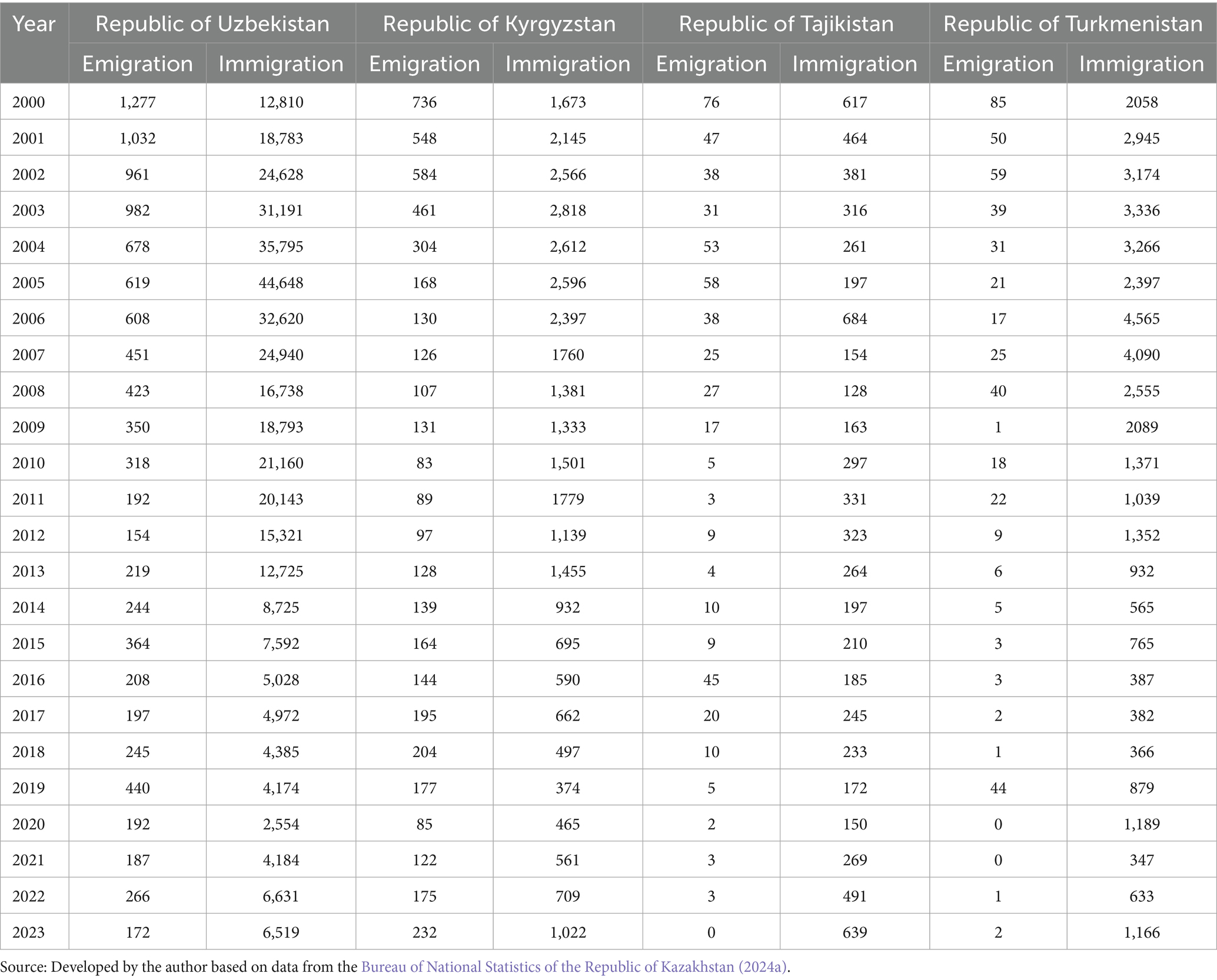

The potential for utilizing the Kazakh diaspora in the Central Asian region as a tool of soft power—encompassing political, economic, and cultural instruments—remains limited due to the significant predominance of immigration flows over emigration. The data presented in Table 2 demonstrate that, over the past two decades, Kazakhstan has been the primary recipient of migration within the Central Asian region. In relation to immigration flows, the replenishment of Kazakh diasporas in the region has been negligible, with the exception of Uzbekistan. It is also important to note that the trend of immigration dominance is characteristic of Uzbekistan as well.

Table 2. Immigration and emigration flows between the Republic of Kazakhstan, Republic of Uzbekistan, Republic of Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Tajikistan, and Republic of Turkmenistan.

It should be noted that the statistical data presented in the table do not provide information regarding whether they reflect the migration of ethnic Kazakh (by ethnicity) or Kazakh (by citizenship) populations, which precludes any conclusion about the national composition of the diaspora. At the same time, speaking about the general trend that could affect the size of the Kazakh diaspora, data from 2023 indicate that the difference in the number of repatriates (41.7% of the total number of immigrants) and emigrants of Kazakh nationality (39.4% of the total number of those who left Kazakhstan) is minimal (Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2024a).

Thus, the influence of the Kazakh diaspora on the Central Asian countries is limited by objective conditions, primarily because Kazakhstan itself serves as a regional immigration center. The number of emigrants from Kazakhstan to other Central Asian countries shows a steady decline. At the same time, the lack of statistical data on the demographic composition of diasporas, particularly regarding Kazakh emigrants from other countries, as well as the impact of birth rates within the diasporas themselves, prevents any definitive conclusions regarding their demographic development trends.

At the time of this study, evaluating the impact of the Kazakh diaspora on the economic situation of receiving countries, as well as its economic interaction with the country of origin (especially in relation to labor migrants), faces significant challenges, primarily due to the absence of objective statistical data. The lack of such data complicates the understanding of the real role the Kazakh diaspora plays in the economy and politics of the receiving countries. Meanwhile, the official information available on the websites of Kazakhstan’s embassies in Central Asian countries shows that the primary focus is on cultural aspects, while economic and political issues remain the prerogative of government structures. This approach limits the potential for utilizing the diaspora as a source of influence in the respective regions.

3.4 Preservation of national identity and the effectiveness of state and non-state structures in supporting the diaspora (on the example of questionnaire survey of ethnic Kazakhs and citizens of Kazakhstan living in Kyrgyzstan)

The study of the aspirations of ethnic Kazakhs and citizens of Kazakhstan living in Kyrgyzstan to preserve their national identity showed the following results (Table 3).

Table 3. Assessment of the importance of certain elements of national identity for ethical Kazakhs and citizens of Kazakhstan living in Kyrgyzstan (developed by the author on the basis of questionnaire survey of 100 respondents).

Thus, the elements related to national identity are mostly assessed by respondents as being important. At the same time, it should be noted that only 23 per cent of respondents indicated Kazakh as an exclusive language for home communication. 39% said that they mainly communicate in Kazakh. At the same time, 29 per cent use mainly Russian for home communication, and 9 per cent use Russian exclusively.

Regarding maintaining contact with family and friends in Kazakhstan, 12% indicated that such communication occurs daily, and 68%—at least monthly. 4% indicated that they have no contacts.

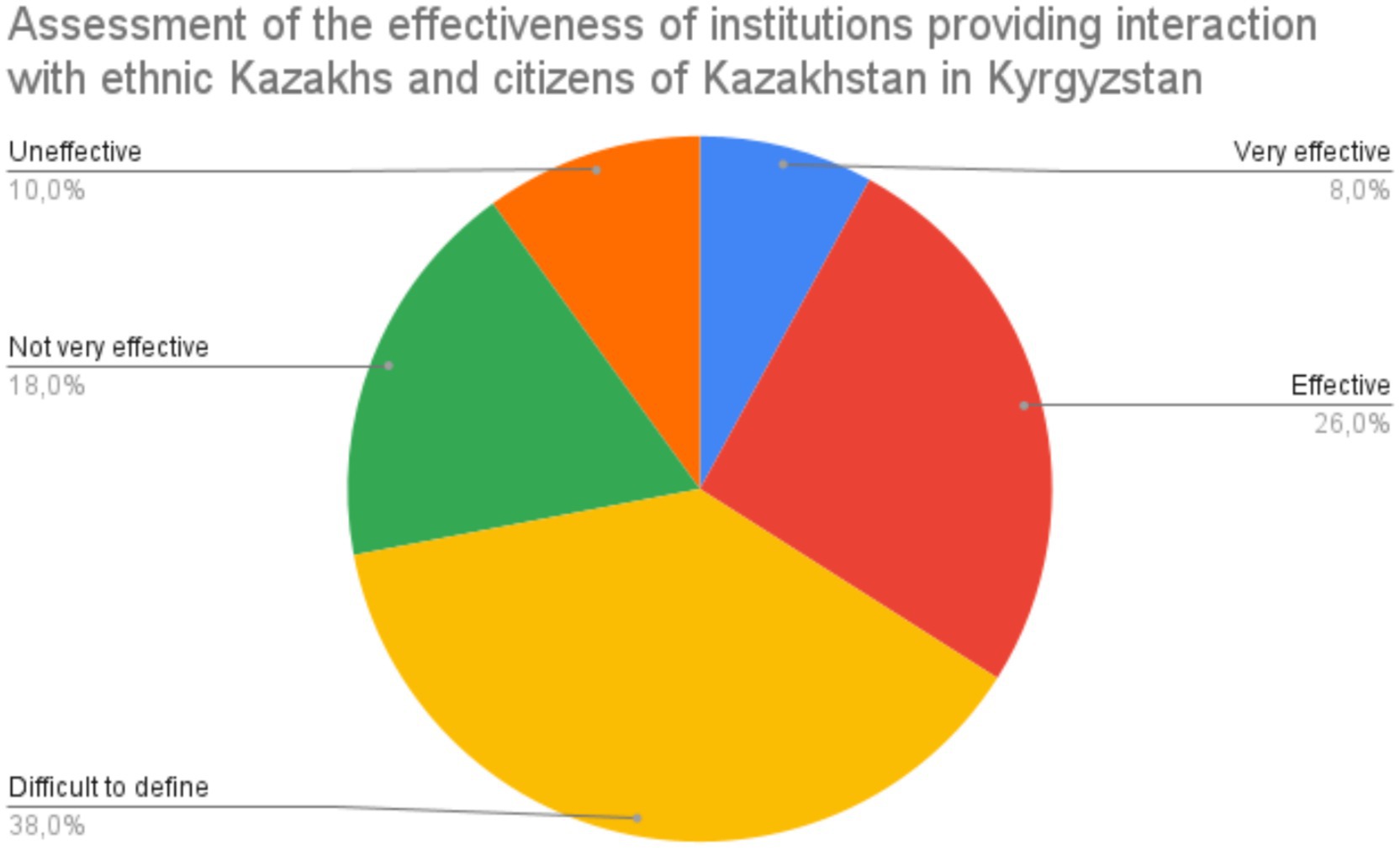

As for the respondents’ assessment of the activities of government structures (including diplomatic institutions) in providing support to members of the Kazakh diaspora in Kyrgyzstan, it was assessed by the respondents as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Assessments of the performance of state structures (including diplomatic institutions) in providing support to ethnic Kazakhs and citizens of Kazakhstan in Kyrgyzstan.

Thus, it can be concluded that there is a need to improve the effectiveness of institutions related to the provision of support to the Kazakh diaspora in Kyrgyzstan.

3.5 Press analyses of Kazakh diaspora activities and migration processes

The analysis of press analyses of the activities of the Kazakh diaspora and interaction with it by Kazakhstan’s institutions shows that today there is still a situation where ethnic Kazakhs remain dispersed across different regions. This requires a constant focus of attention by Kazakhstan’s state authorities on strengthening the unifying influence (Sattarov, 2022). Issues related to the need to unite Kazakhs regardless of their place of residence and the formation of their perception of Kazakhstan as their homeland are in the sphere of special attention of the President of Kazakhstan. The need to increase opportunities for Kazakhs living in other countries to learn the Kazakh language and to support their integration into local structures and communities is also emphasised (The Astana Times, 2023). Facilitating the organisation of professional and academic communities and the participation of members of the Kazakh diaspora in their work is seen as an important soft power tool (DKN World News, 2024). Thus, the attention of representatives of Kazakhstani institutions when considering the issue of assistance to Kazakh diasporas covers a wide range of issues. This approach should ensure a comprehensive impact on the development of Kazakh diasporas.

4 Discussion

When defining diaspora policy, the organization of interaction with the diaspora plays a crucial role, particularly from the perspective of the country of origin. As the study has shown, even within a single region, issues and challenges related to migration and diaspora activities can differ significantly. It is also important to highlight the need for expanding the tools for interaction between the diaspora and the country of origin. The development of modern communication technologies offers virtually unlimited opportunities in this regard. Academic literature emphasizes the special role of media resources and social networks in this process, as they allow for overcoming remnants of the Soviet approach to information dissemination and provide diaspora members with an informal version of events in the country of origin (Serikzhanova and Nurtazina, 2024).

At the same time, the study revealed that the current approach to organizing work with Kazakh diasporas in Central Asian countries is rather traditional, based on the establishment of cultural centers and the organization of events dedicated to national holidays. While the importance of such activities should not be underestimated, it is worth noting that more active use of modern technologies could serve as an important resource, as it allows for reaching a larger number of diaspora members regardless of their place of residence and field of activity. This approach would also facilitate feedback mechanisms, especially in situations where the receiving country faces internal issues, such as human rights concerns, or when the life circumstances of diaspora members prevent them from directly contacting consular institutions or other authorities of the country of origin for information and assistance.

In addition to direct communication with the authorities of the country of origin, attention must also be given to fostering cooperation between consular institutions and the diaspora itself, in order to ensure that Kazakh migrants receive first-level assistance from the diaspora. This is particularly relevant in situations where, as the study indicates, it is common for labor migrants to ignore the necessity of registering with consular authorities.

It is also important to agree that the concept of diaspora in the contemporary world is a dynamic phenomenon, which can be understood more broadly than just the presence and interaction of members of a single ethnic group in the territory of a host country. Ethnic characteristics of its members are still considered a leading feature of a diaspora (Askhat, 2020). At the same time, the migration situation of the 21st century differs significantly from that of the past, as the traditional concept of forced migration, which aimed at return and a form of restoration of the status quo, is being replaced by a new understanding of existence in the world, based on mobility (Mahmod, 2019). An example of such mobility is the notion of the “scientific diaspora,” understood as a community of researchers conducting studies across different parts of the world. Given the general policy orientation of the Republic of Kazakhstan toward the repatriation of Kazakh diaspora members, the issue of scientific mobility cannot be overlooked, as it also plays a key role in enhancing the scientific potential of the country of origin (Marmolejo-Leyva et al., 2015).

Migration policy is often grounded in the thesis of counteracting the so-called “brain drain.” However, this argument has also been challenged in academic literature. Specifically, a study conducted on the labor market in Australia revealed the lack of significant effectiveness in attempts to address the issue of attracting talented employees through foreign migrants (Tani, 2019). Therefore, the issue of repatriation should be viewed more broadly, not limited to the physical return of diaspora members, but also by expanding cooperation with its intellectual elite. Consequently, the policy of return to the country of origin is not the only possible option for strengthening the role of the diaspora. The very understanding of the diaspora can be extended to include national associations in various professional fields, even when the members of such a community are located in different territories. This approach significantly expands research opportunities that may be limited by economic and other constraints in the country of origin, while avoiding the loss of intellectual resources (Echeverría-King et al., 2022).

The increasing level of globalization and mobility is inevitable. Thus, the proposed approach should be expanded to other sectors, particularly the business sector. The size of the Kazakh diaspora relative to the total population of Kazakhstan, as shown in the study, justifies the appropriateness of such an approach. Despite repatriation being the main goal of migration policy, such a significant potential should not remain overlooked, as it represents an important tool of soft power and a means of strengthening ties between the country of origin and the host country.

5 Conclusion

The national policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan regarding its interaction with the Kazakh diaspora is primarily focused on ensuring repatriation. An important aspect of this policy is the preservation of national identity, which is facilitated through special repatriation conditions and the provision of state support to individuals of Kazakh nationality. At the same time, the official approach, despite the significant number of initiatives aimed at achieving this goal, overlooks an important aspect: interaction with the diaspora in the context of globalization. Understood as transnationalism, the support for maintaining connections between diaspora members and their country of origin is greatly enhanced by the development of modern technologies, which provide virtually unlimited communication opportunities. In situations where repatriation is not feasible, all possible avenues for cooperation should be utilized, especially those aimed at involving highly educated members of the Kazakh diaspora in the development of Kazakhstan’s science, economy, education, and culture.

When discussing the role of the Kazakh diaspora, two key characteristics should be highlighted. The first is the genetic trait of the Kazakh people, who have a history of nomadic life, which has fostered a high level of adaptability to new conditions. Moreover, when considering the Kazakh diaspora in Central Asian countries, it is important to take into account the shared history, culture, and mentality of the peoples of this region. However, one of the defining factors for the success of the Kazakh diaspora’s activities is the joint efforts with the Republic of Kazakhstan aimed at developing projects in a broad range of fields (business, culture, education), both in the host countries and in creating conditions for repatriates, as reflected in the Migration Policy Concept of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2027.

Special attention should be given to the inability of children from small diasporas to receive an education in the Kazakh language due to the lack of Kazakh schools. At the same time, modern technologies provide a wide range of opportunities to address this issue, including the option of online education.

The organization of cooperation with the Kazakh diaspora and the resolution of tasks aimed at stimulating repatriation processes cannot be considered in isolation from global political processes. The data presented in the study highlight a significant imbalance in the educational levels of emigrants and repatriates, with the predominant trend being the emigration of highly qualified personnel.

At the same time, in cases where the physical return of skilled professionals is not feasible, this issue can be addressed through alternative means in the context of globalization, primarily by strengthening communication with such representatives of the Kazakh diaspora and involving them in joint projects and other forms of cooperation. This approach will not only help mitigate the shortage of qualified personnel to some extent but also serve as a crucial direction for working with Kazakh diasporas in other countries in the region, with the goal of attracting investment. Such cooperation will also enhance Kazakhstan’s influence in the region through soft power methods, particularly through the further promotion of Kazakh culture, the development of the Kazakh language, the establishment of Kazakh educational institutions, and the expansion of joint business, scientific, and investment projects.

A further avenue for improving state-level interaction policy should be the identification of opportunities to leverage the intellectual and economic potential of members of the Kazakh and Kazakhstan diasporas, as well as expanding cooperation with Kazakhs living permanently in other countries by involving them in projects and programs. Existing government initiatives should be directed at the Kazakh and Kazakhstan diasporas to develop the potential of the Republic of Kazakhstan by increasing the attractiveness of educational, scientific, and IT programs, as well as opportunities for children and youth from Kazakh diasporas. At the same time, for example, it is important to expand the list of professions under the “Ata zholy” program for ethnic Kazakhs, going beyond the existing categories, and to implement the “digital nomads” project with the active participation and involvement primarily of members of the Kazakh diaspora.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. NK: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. UT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamson, F. B., and Han, E. (2024). Diasporic geopolitics, rising powers, and the future of international order. Rev. Int. Stud. 50, 476–493. doi: 10.1017/S0260210524000123

Adilet,. (2024). Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. On Approval of the National Development Plan of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2029 and invalidation of some decrees of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated July 30, 2024 № 611. Available online at: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U2400000611#z967 [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Asia Terra. (2021). Kazakhs in Uzbekistan. Available online at: https://m.asiaterra.info/pfotografy/kazakhi-uzbekistana-foto-umidy-akhmedovoj [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Askhat, G. (2020). Diaspora study as a tool to define ‘Kazakh diaspora’: international perspective. GRFDT 6, 5–11.

Baizhuma, G., Dukenbayeva, Z. O., Yensenov, K. A., Aubakirova, K. A., and Naimanbayev, B. R. (2021). History of Kazakh diaspora return to Kazakhstan from Mongolia (1991-2011). Astra Salvensis 1, 587–601.

Bekzhanova, R. Z., Koblandin, K. I., and Sergazin, Y. F. (2022). The role and significance of the diaspora community in politics, economy, and culture. Bull. L.N. Gumilyov Eur. Natl. Univ. Polit. Sci. Reg. Stud. Orient. Stud. 1, 134–142.

Buchholz, K. (2022). The world’s biggest diasporas. Forbes. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/katharinabuchholz/2022/11/11/the-worlds-biggest-diasporas-infographic/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2024a). Balance of external migration of the population of the Republic of Kazakhstan by country. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/upload/iblock/821/e60lp4ynix0repyd18tm3mv117idc69q/%D0%92%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%88%D0%BD%D1%8F%D1%8F%20%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F%20%D0%BF%D0%BE%20%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BC.xlsx [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2024b). Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan by individual ethnic groups, gender and type of locality at the beginning of 2024. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/upload/iblock/b94/qknokvkla7nlpijdw01h8n88ifbeufmz/%D0%91-18-07-%D0%93%20(%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B3)%20%D0%A24.xlsx [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2024c). Structure of external migration by individual ethnic groups, in per cent of the total number. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/industries/social-statistics/demography/publications/157454/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Central Communicate Service under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2024). More than 8.7 thousand ethnic Kazakhs have received the status of kandas since the beginning of 2024. Available online at: https://ortcom.kz/en/novosti/1721366899 [Accessed January 22, 2025]

DARYO (2024). Ethnic Kazakhs migrate from Turkmenistan to homeland. https://daryo.uz/en/2024/01/16/ethnic-kazakhs-migrate-from-turkmenistan-to-homeland [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Diasporas (2024). Migration data portal. Available online at: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/diasporas [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Dijkzeul, D., and Fauser, M. (2024). Diaspora organisations in international affairs. Online First Book Review, 1: 1–3. Available online at: https://www.ir-journal.com/storage/media/4316/01J45FPPK4BG1X88CXYMR2S4C2.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

DKN World News. (2024). Kazakh diaspora: cultural projects and successes in Japan. Available online at: https://dknews.kz/ru/v-mire/345481-kazahskaya-diaspora-kulturnye-proekty-i-uspehi-v?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Echeverría-King, L. F., Toro, R. C., Figueroa, P., Galvis, L. A., González, A., Suárez, V. R., et al. (2022). Organised scientific diaspora and its contributions to science diplomacy in emerging economies: the case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 7:893593. doi: 10.3389/frma.2022.893593

Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Kyrgyz Republic. (2024). Cultural and humanitarian cooperation. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa-bishkek/press/article/details/121090?directionId=_2253&lang=ru [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Republic of Uzbekistan. (2024). Cultural and humanitarian cooperation. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa-tashkent/activities/2278?lang=ru [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in Turkmenistan. (2024). Available online at: Cultural and humanitarian cooperation. https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa-ashgabat/activities/2247?lang=ru [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Eschment, B., and De Cordier, B. (2021). Introduction: ethnic, civic, or both? The ethnicities of Kazakhstan in search of an identity and homeland. Cent. Asian Aff. 8, 315–318. doi: 10.30965/22142290-12340010

EU DIF (2024). Diaspora engagement in EECA. Available online at: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/eastern-europe-central-asia/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Garcia-Zamor, J.-C. (2017). The global wave of refugees and migrants: complex challenges for European policy makers. Public Organ. Rev. 17, 581–594. doi: 10.1007/s11115-016-0371-1

Global Forum on Migration and Development (2010). Kazakhstan: Extended migration profile. Available online at: https://www.gfmd.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1801/files/pfp/mp/Kazakhstan_Extended_Migration_Profile_ru.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Green, D., and Kadoya, Y. (2015). Contact and threat: factors affecting views on increasing immigration in Japan. Policy Polit. 43, 59–93. doi: 10.1111/polp.12109

Grossman, J. (2019). Towards a definition of diaspora. Ethn. Racial Stud. 42, 1263–1282. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2018.1550261

IOM (2020). Return migration. International approaches and regional features of the Central Asia. Available online at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/Return-Migration-in-CA-RU.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

IOM. (2022). Analysis and recommendations (including gender-specific aspects) on relevant policy and institutions for interaction with the diaspora in Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://kazakhstan.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1586/files/documents/Analysis%20and%20Recomendations_EN_print.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

IOM (2023a). Kazakhstan: overview of the migration situation. Available online at: https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Quarterly%20Compilation%20Report%205%20%28Oct%20-%20Dec%202023%29_0.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

IOM. (2023b). Overview of the migration situation in Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Quarterly%20report%20DTM%20KAZ%20Q1%202023.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

IOM (2024a). Situation report on migration. Available online at: https://dtm.iom.int/dtm_download_track/59376?file=1&type=node&id=40676 [Accessed January 22, 2025]

IOM (2024b). World migration report. Available online at: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/msite/wmr-2024-interactive/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Karassayev, G., Kenzhebayev, G., Aminov, T., Duisen, S., and Shukeyeva, S. (2022). Relations between the Republic of Kazakhstan and Kazakhs abroad (1991–2000). Migrat. Lett. 19:5, 687–694.

Karassayev, G. M., Yensenov, K. A., Naimanbayev, B. R., Bakirova, Z. S., and Kabdrahmanova, F. K. (2023). Mutual cooperation of the Republic of Kazakhstan with the states of Central Asia in 1999–2000. Artículo de Investigación 10, 183–197. doi: 10.35588/rivar.v10i29.5820

Kazinform. (2022). The association of Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan celebrates its 30th anniversary. Available online at: https://www.inform.kz/ru/associaciya-kazahov-v-kyrgyzstane-otmechaet-30-letniy-yubiley_a3997938 [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Khama, N. K. (2020). Diaspora and foreign policy: a global perspective. Int. J. Polit. Sci. 6, 12–20. doi: 10.20431/2454-9452.0604002

Klingner, D. E. (2020). Migration and immigration. Public Integr. 22, 403–406. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2020.1747235

Kumar, A. (2021). Post-soviet minorities experience in Kazakhstan. JCAS, 28, 1–13. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Amit-Kumar-881/publication/381196075_Post-Soviet_Minorities_Experience_in_Kazakhstan/links/66629f0085a4ee7261ab2adc/Post-Soviet-Minorities-Experience-in-Kazakhstan.pdf [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Lahanuly, N. (2017). Kazakh youth in Tajikistan do not know their native language. Asatuk Radio. Available online at: https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhi-tajikistana-abdisattar-nurgaliev/28269094.html [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Lahanuly, N. (2018). Kazakh youth leave Turkmenistan. Asatuk Radio. Available online at: https://rus.azattyq.org/a/turkmenistan-kazakhi/29128090.html [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Mahmod, J. (2019). New online communities and new identity making: the curious case of the Kurdish diaspora. JECS 6, 34–43. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/245

Marmolejo-Leyva, R., Perez-Angon, M. A., and Russell, J. M. (2015). Mobility and international collaboration: case of the Mexican scientific diaspora. PLoS One 10:e0126720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126720

Migration Data Portal. (2024). Migration data in Central Asia. Available online at: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/regional-data-overview/central-asia [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Kazakhstan. (2024). Cooperation of the Republic of Kazakhstan with the Republic of Tajikistan. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa/press/article/details/548?lang=ru [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2022). On approval of the Concept of Migration Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2027. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/enbek/documents/details/383914?lang=ru [Accessed January 22, 2025]

National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (2022). Total population by nationality. Available online at: https://www.stat.gov.kg/en/opendata/category/312/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Niemann, A., and Zaun, N. (2023). Introduction: EU external migration policy and EU migration governance. JEMS 49, 2965–2985. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193710

Reference Control Bank of Normative Legal Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2002). About population migration. Available online at: http://law.gov.kz/client/#!/doc/341/rus/27.03.2002/5 [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Rosenberg, M.-A. S., Bougainville, D. M., and Mohammed, S. A. (2016). Trans nationalism: a framework for advancing nursing research with contemporary immigrants. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 39, E19–E28. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000108

Sattarov, D. (2022). About the Kazakh diaspora. Interview with Gulnara Mendikulova. Available online at: https://www.caa-network.org/archives/23917/o-kazahskoj-diaspore-intervyu-s-gulnaroj-mendikulovoj?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Sebakwiye, C., and Bidandi, F. (2024). How did refugees and migrants’ solidarity initiatives become an intervention for disaster and humanitarian response during the COVID–19 pandemic in Cape Town, South Africa? Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1346643. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1346643

Serikzhanova, A., and Nurtazina, R. (2024). Evolving political cultures in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan: trends and new paradigms. JECS 11, 1–24. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/1914

Shuval, J. T. (2000). Diaspora migration: definitional ambiguities and a theoretical paradigm. Int. Migr. 38, 41–57. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00127

Solano, G., and Huddleston, T. (2022). “Migration policy indicators” in Introduction to migration studies. ed. P. Scholten, IMISCOE Research Series (Cham: Springer), 389–407.

Statistics Agency under the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2024). Official web site. Available online at: https://stat.uz/en [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Strategic Development Center. (2021). Current state of work with the Kazakh diaspora abroad: main trends. Available online at: https://kisi.kz/ru/sovremennoe-sostoyanie-raboty-s-kazahskoj-diasporoj-za-rubezhom-osnovnye-trendy/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Tani, M. (2019). Migration policy and immigrants’ labor market performance. Int. Migr. Rev. 54, 35–57. doi: 10.1177/0197918318815608

The Astana Times (2023). Ostandar forum brings Kazakh nationals together. Available online at: https://astanatimes.com/2023/10/otandastar-forum-brings-kazakh-nationals-together/?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed January 22, 2025]

The Astana Times (2024). Kazakh diaspora: uniting across borders for cultural preservation and solidarity. Available online at: https://astanatimes.com/2024/05/kazakh-diaspora-uniting-across-borders-for-cultural-preservation-and-solidarity/ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

World Bank Group. (2024). Population total. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=TJ [Accessed January 22, 2025]

Keywords: diaspora, global population, international relations, migration, national identity, national minority, soft power, transnationalism

Citation: Nurbek K, Kalashnikova N and Turan U (2025) The Kazakh diaspora in Central Asia: preservation of national identity and institutional influence in the region. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1583799. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1583799

Edited by:

Paulo Afonso Brardo Duarte, Universidade Lusófona do Porto, PortugalReviewed by: