- 1Government Science Study Program, Department of Social and Political Science, Universitas Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

- 2Government Management Study Program, Universitas Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

This study aims to examine how the pattern of disinformation spread on social media to candidates in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election. This research uses a qualitative method with a case study approach. The findings of this study explain that in the 2024 elections in Indonesia, social media had a significant role in spreading disinformation. Each candidate becomes a victim of disinformation attacks on social media by attacking from the side of character assassination and political issues. Then, the pattern of disinformation in the 2024 elections was more dominant on social media channels that supported the emergence of video and text characters, such as Facebook, YouTube, and Tiktok. Furthermore, the spread of disinformation to candidates harms their participation in the 2024 elections. This research implies that digital technology intervention significantly influences candidates in election contestation. Moreover, social media has become a sophisticated facility for spreading disinformation by political actor teams to utilize as a form of electoral attack effort.

1 Introduction

The Indonesian presidential and vice presidential elections was held on February 7, 2024 (KPU RI, 2023b). According to Law Number 7 of 2017 concerning general elections, it states candidate pairs are proposed by political parties or a coalition of political parties participating in the election that meet the requirements of obtaining at least 20% (20%) of the total seats in the People's Representative Council (DPR) or obtaining 25% (25%) of valid votes nationally in the previous DPR member elections. In the 2024 presidential election, three candidate pairs meet the competition requirements. Candidate pair number one, Anies Baswedan with Muaimin Iskandar, who was supported by the National Democratic Party (Nasdem), the National Awakening Party (PKB) and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS). Then, candidate pair number two, Prabowo Subianto with Gibran Rakabuming Raka, supported by the Gerindra Party, the National Mandate Party (PAN), the Golkar Party, and the Democratic Party. Next, candidate pair number three, Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD, were supported by the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) and the United Development Party (PPP) (KPU RI, 2023a).

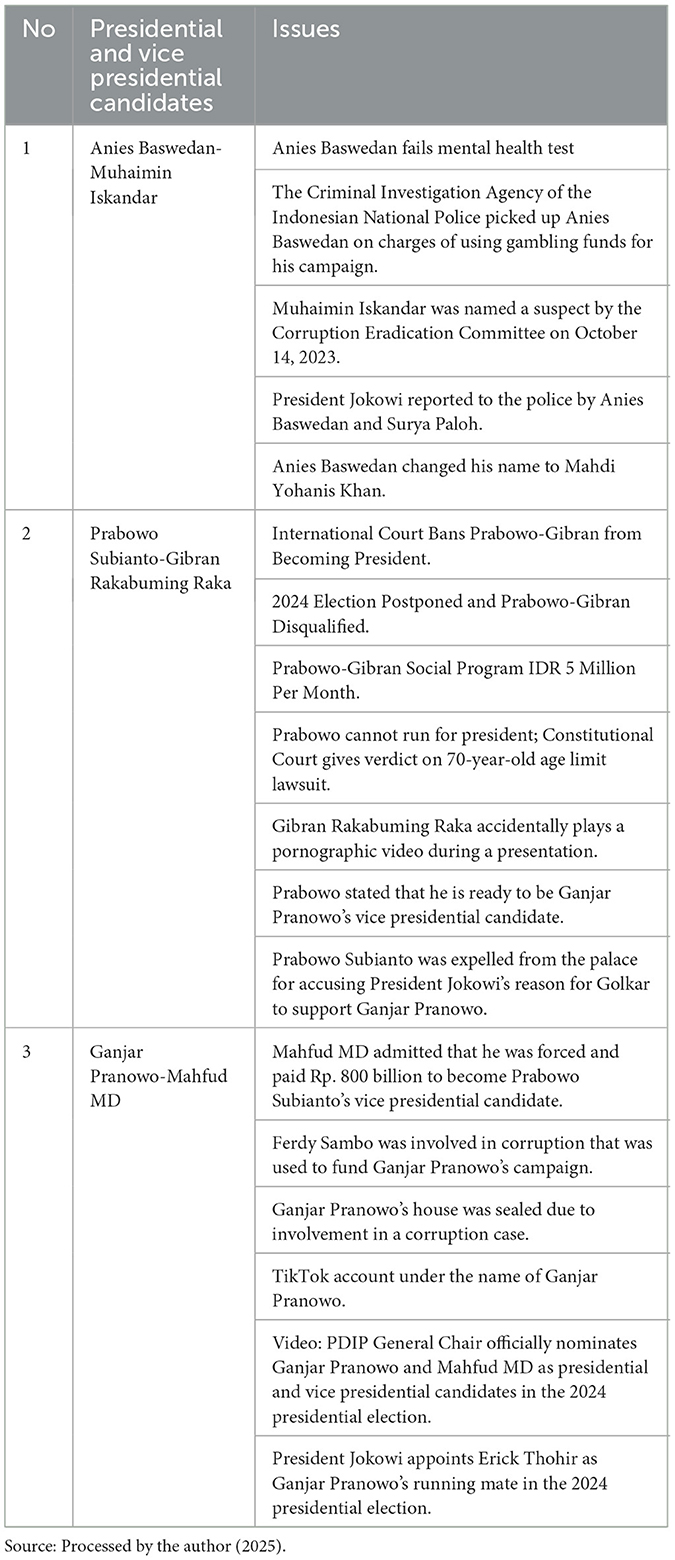

Furthermore, the 2024 election campaign period officially begins on November 28, 2023, and continues until February 10, 2024, for both presidential and vice presidential candidates and legislative candidates (Wibawana, 2024). However, a significant problem is the massive spread of disinformation or hoaxes on digital media, especially social media, related to the 2024 presidential and vice presidential elections. Figure 1 shows the trend of increasing hoax information on social media from July 2023 to December 2024.

Figure 1. The trend in the number of hoax information related to the 2024 election. Source: Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika (2024).

The data in Figure 1 shows an increasing trend in disinformation spread on social media from July to December 2023. Minister of Communication and Information Budi Arie Setiadi stated that as of Tuesday (02/01/2024), he had handled 203 election disinformation issues with a total distribution on digital platforms of 2,882 contents. In detail, the Ministry of Communication and Information has identified 1,325 contents on the Facebook platform, 947 contents on the X platform, 198 contents on the Instagram platform, 342 contents on the TikTok platform, 36 contents on the Snack Video platform and 34 contents on the Youtube platform (Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika, 2024). This data explains that in the 2024 election, digital media played a very significant role in spreading disinformation, which, of course, disrupted the democratic party process in Indonesia.

The world of electoral politics has entered a new era mediated by social media, where politicians and political parties conduct permanent campaigns without geographical or time limitations using social media. Information related to them can be directly disseminated on personal social networks or through other people who share it, which increases their popularity in cyberspace (Subekti et al., 2022). However, the other side of social media's role in electoral politics is very concerning, especially as a facility for spreading disinformation that tries to attack candidates. The spread of political disinformation on social media platforms has generally been considered a threat to the democratic system and national security (Power Wogu et al., 2020; Cano-Orón et al., 2021).

Therefore, it is very important to discuss the pattern of disinformation dissemination to candidates in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election. This is because disinformation in elections has a very negative impact, namely, political polarization and fragmentation. Furthermore, disinformation also causes elections to lose constructive discussions between political contestants. This study is an effort to identify the problems that arise from social media in the election, which can then be resolved to impact the Indonesian democratic process positively. More than that, it is also fundamental to identify the dissemination of disinformation that affects the electability of presidential and vice presidential candidates. Therefore, this study aims to explain the pattern of disinformation dissemination on social media to candidates in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election.

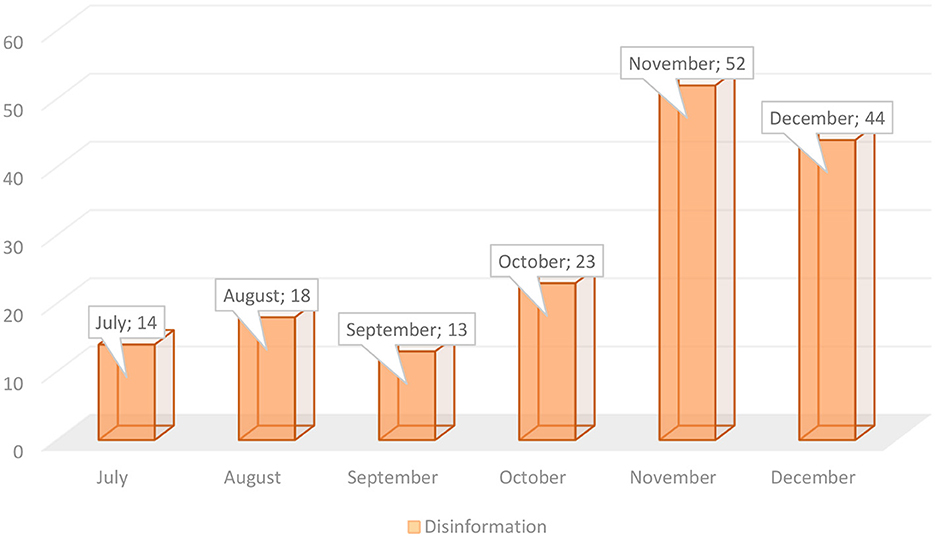

Several previous studies have studied the topic of disinformation in elections. A previous research search using the Scopus database found 16 articles from 2018 to 2024 that discussed this topic from various perspectives. Then, Vosviewer software was used to help analyze and visualize the density of discussion of these articles. Vosviewer is a software tool for building and visualizing bibliometric networks. For example, these networks can include journals, researchers, or individual publications and can be built based on citations, bibliographic mergers, co-citations, or co-authorship relationships. Vosviewer also offers text mining functionality that can be used to construct and visualize co-occurrence networks of important terms extracted from scientific literature (Eck and Waltman, 2013).

Figure 2 shows the density of research on disinformation in elections from 2018 to 2024, indexed by Scopus. The principle of Vosviewers analysis with this density feature is that the research perspective can be recognized from the keywords highlighted in yellow. The denser the keywords surrounded by yellow, the more research has used that perspective as the focus of discussion. Conversely, if the yellow color is not too dense on the keywords, then it has not been discussed much in research. Therefore, these keywords can be used as a novelty offer in further research in the context of that research topic (Eck and Waltman, 2010).

Figure 2. Visualization of research density on disinformation in elections. Source: Processed by the author using Vosviewers software (2024).

The data in Figure 2 shows that keywords such as fake news, election, social media, democracy, and polarization have become the focus of discussion in research on disinformation in elections. Meanwhile, the keywords disinformation strategies, digital media, Facebook, and political parties are not too dense in yellow around them, so few studies still take this perspective. Therefore, this study takes a position to offer novelty in the discussion of disinformation in elections from the perspective of strategic patterns of its spread on social media and its impact on candidates.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Disinformation in the age of social media

Disinformation, in general, is intentionally misleading information and has the function of misleading someone. This is the deliberate creation and/or dissemination of information that is known to be false (Fallis, 2014). Therefore, the intention to deceive and factuality are the main things (Chaves and Braga, 2019). Furthermore, disinformation must be distinguished from “misinformation” and “fake news.” The boundaries are sometimes blurred, and the terms are used interchangeably or interchangeably. Misinformation means wrong information. The information is wrong, but the person spreading it believes it is true. The dissemination of information is done for good purposes, meaning there is no tendency to harm others. Meanwhile, in malinformation, the information is true. Unfortunately, the information is used to threaten the existence of a person or group of people with a specific identity. Malinformation can be categorized as hate speech. The targets can be adherents of minority religions or those with different sexual orientations (Guess and Lyons, 2020; Carral et al., 2023; Benaissa Pedriza, 2021).

A “disinformation operation” is the dissemination of false information. Incorrect or misleading information and/or content is disseminated to influence voters' minds, actions, or tendencies (Hansen and Lim, 2019). Often, the information is made in such a way that it resembles credible news. While disinformation has long been used for political purposes, the Internet, social media, and public platforms as tools to spread such information have particularly empowered such operations. False or misleading information (in written image or video form) exploits the fact that it is often passed without filtering or review from one screen to another in seconds (Cano-Orón et al., 2021). Disinformation can range from stories, for example, that Pope Francis endorsed Donald Trump in the 2016 election, to false information that polling stations are closed (Pérez-Curiel and Rivas-de-Roca, 2022).

In this complex digital landscape, social media advertising has operated as an opaque means of disseminating information. Through this tool, companies can send their ads to specific social media audiences so that only they see the message (Tufekci, 2015; Woolley and Howard, 2016). The capacity of social networking sites to segment audiences is based on the digital footprint left by users on the site (Kim et al., 2018). In line with this, several researchers have raised the need to follow up on sponsored content due to its potential to spread disinformation (Gray et al., 2020). In the case of Facebook in particular, several researchers have shown how this platform has been used to divide the population and provide misinformation, especially in the case of paid advertising by the Russian Internet Research Agency in the United States (Ribeiro et al., 2019; Lukito, 2020). Social networking sites are very attractive to advertisers. The business model of these sites, of which Facebook is the paradigm, has been built on their advertising services (Kreiss and Mcgregor, 2018; Dommett and Power, 2019). This issue of social media accountability is part of a broader debate in search of solutions to an increasingly polarized, uninformed, and fragmented network ecosystem (Bakir and McStay, 2018).

Online/social/internet platforms have fundamentally changed the information environment by offering new channels for disinformation. Several characteristics of this new information environment make “digital disinformation” different from traditional disinformation. First, on these platforms, there is an endless flow of news, opinions, emotions, reactions, images, videos, online services, and so on (between people and their peers). Individuals are not just consumers of information but also creators. Second, digital disinformation makes digital behavior traceable across online/social/internet platforms. “Like,” “react,” “share,” “post and repost,” “tweet and re-tweet,” “review,” and so on amplify the content of information regardless of whether the information is true or false.

Third, the content on online/social/internet platforms is a mixture of facts, personal and professional information, lies, opinions, and emotions, which can exaggerate and influence the content. Bots, fake accounts, fake authors, fake followers, trolls, and “like” factories further disseminate true and false information. Other types of technological amplification on these online/social/internet platforms are algorithms, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automation. Fourth, truth has become indistinguishable from false information on these online/social/internet platforms (Bargaoanu and Radu, 2018).

2.2 Digital media ecology

The concept of media ecology was first introduced by figures such as Neil Postman and Marshall McLuhan, who viewed media not merely as a means of communication, but as a symbolic environment that shapes the way people think, act, and interact in society. In work Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, stated that “the medium is the message,” emphasizing that the characteristics of the media itself are more important than the content it carries, because the media changes perceptions, social structures, and power relations (McLuhan, 1994). Then, it expanded on this understanding by emphasizing that each type of media creates a unique cognitive ecosystem, which ultimately influences cultural development and the way humans perceive reality (Postman, 1970).

In its development, the concept of media ecology has expanded into the digital context, giving rise to the term Digital Media Ecology. Digital media ecology refers to the communication environment formed by interconnected digital media networks that influence human social, political, and cultural behavior in more complex ways. Levinson (2020) argues that McLuhan's ideas must be reinterpreted in the context of the twenty-first century, where digital technologies, such as the internet, social media, and algorithms, have become dominant forces in shaping the dynamics of information and communication. Meanwhile, Fuller (2005) views digital media as a material, dynamic, and interactive ecological system, emphasizing the importance of analyzing the relationships between humans, machines, and cultural practices within an interconnected system.

Within the framework of Digital Media Ecology, several key components interact with one another. The first is technology, which includes hardware and software such as social media algorithms, digital platforms, and communication infrastructure that serve as the primary medium for information exchange (Couldry and Hepp, 2022). Second is digital content, whether in the form of text, images, audio, or video, which serves as the primary material in the digital communication process and is continuously produced and consumed on a massive scale (Jenkins et al., 2013). Third are users, who in the digital context act as prosumers—that is, both producers and consumers of information (Bruns, 2008). The active role of users in generating meaning and participating in the media ecosystem creates a two-way communication dynamic not found in traditional media. Fourth is the network, which is the structure of relationships between individuals, institutions, and the media itself, forming a fluid and complex global communication space (Castells, 2013).

Various key concepts emerge from this digital media ecology. One of these is convergence culture, which describes the convergence of old and new media, as well as collaboration between professional producers and ordinary users. This convergence creates a new media landscape that is more participatory and dynamic (Jenkins, 2006). Additionally, participatory media has become a key feature of the digital ecosystem, where users are no longer passive but actively involved in the production and dissemination of information (Carpentier, 2011). The role of algorithms is also increasingly prominent as digital mediation agents. Algorithms not only determine the order of content users see but also shape perceptions of the world and limit discursive space through processes that are hidden and non-transparent (Gillespie, 2014).

3 Methodology research

This study uses a qualitative method. The qualitative method is an attempt to rationalize and interpret the reality of life based on what the researcher understands (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). This study uses content analysis to discuss disinformation on social media targeting candidates in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election. Content analysis is an analytical approach that focuses on interpreting and describing topics and themes that appear in communication content in a meaningful way when framed based on the research objectives (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

3.1 Data collection and source

The data collection technique used in this study is literature. Therefore, this study utilizes data sources obtained from credible and reputable online news sources, such as Tirto.id, Drone Emprite publication, Kompas.com, Kompasiana.com, Tempo.co, and government and non-governmental organization (NGO) websites relevant to the research topic. Then, the data is elaborated with the findings of previous relevant journal articles. The selection of data in this study was based on its relevance to the case under investigation, namely disinformation on social media in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election. Then, in validating the data for this study, triangulation was employed, which involves the use of multiple data sources to facilitate comparisons and obtain objective data. The data analyzed were in the form of images, tables, and narrative statements obtained from research data sources.

3.2 Data analysis

This study uses a content analysis to examine disinformation on social media during the 2014 Indonesian presidential election. Therefore, the stages carried out in analyzing the data of this research. First, Data Identification: The types of data analyzed in this study are social media content and written documents. Second, Code Development: identifying and defining categories relevant to the topic of this study. Third, Coding: applying codes to the data based on the findings that have been identified. Fourth, Interpretation: review the codes and interpret the results to identify patterns, themes, and deeper insights. Fifth, Drawing Conclusions: Draw conclusions based on the identified findings and connect them to the research questions.

4 Result

4.1 Disinformation issues

The Presidential and Vice Presidential Election is a competition for political actors (Political Parties, presidential and vice presidential candidates), in which there is also an information battle. In the election process, the dissemination of information and data is massive. Amid the onslaught of information, there is a widespread emergence of fake news or disinformation that disrupts the dignity of the election as an instrument of democracy. There is a political shift from the era of objective truth to lies (post-truth politics) (Hannan, 2018). In elections, it is not important whether the information conveyed is true, but what is important is how the message or narrative can be conveyed repeatedly so that it can influence a person's mind in determining their right to vote. In communication, a known bullet theory assumes that a communicator can shoot such magical communication bullets at a helpless audience (Mauk and Grömping, 2023).

In the context of the 2024 Indonesian presidential and vice presidential elections, the spread of disinformation is massive. The 2024 Presidential and Vice Presidential Elections in Indonesia are not only an important momentum in the democratic process but also pose significant challenges related to disinformation. This phenomenon is a major focus because of its substantial influence on the political process, public opinion, and the integrity of the general election. In an era where technology and social media provide freedom for anyone to spread information, disinformation, and hoaxes have become a serious threat to the integrity of the democratic process, especially in the context of the 2024 General Elections.

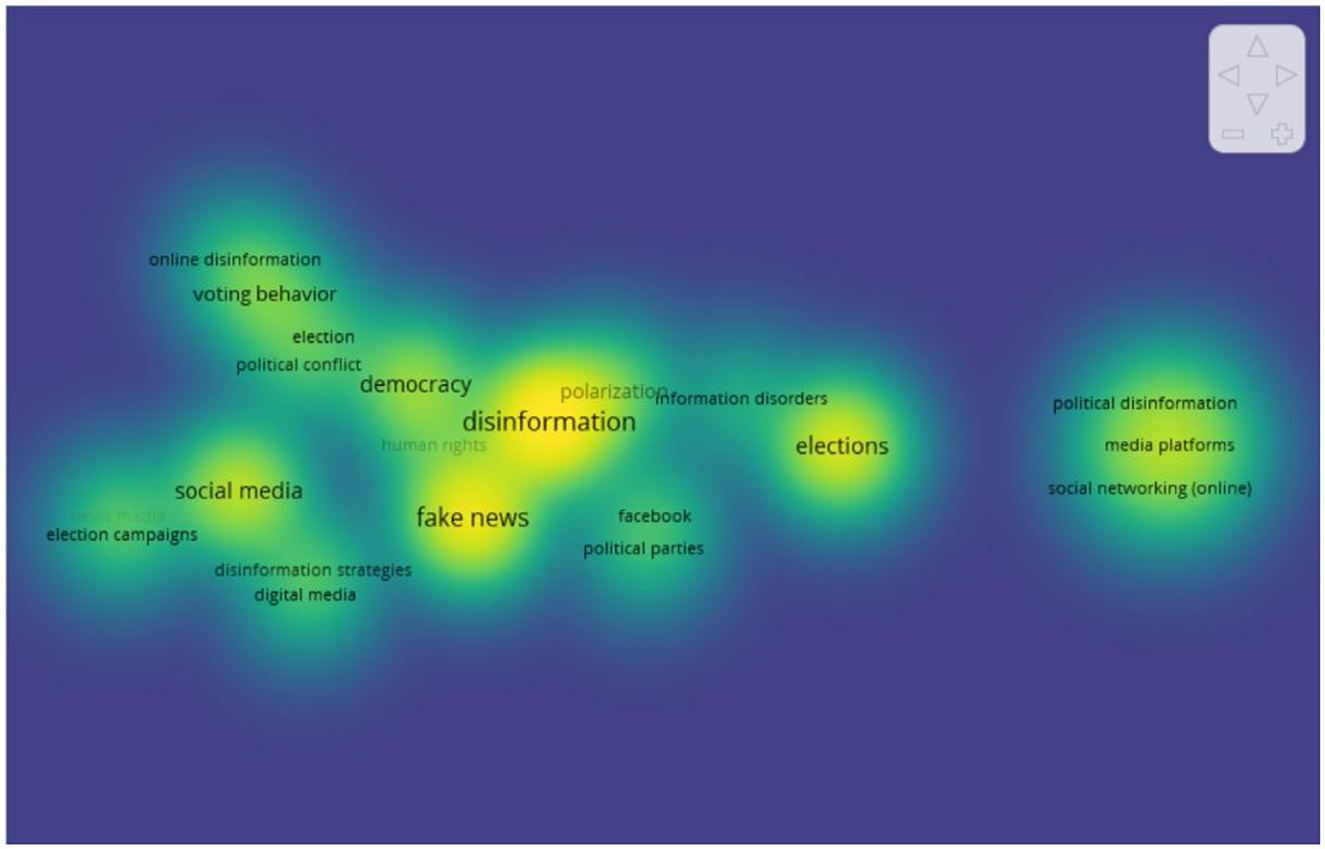

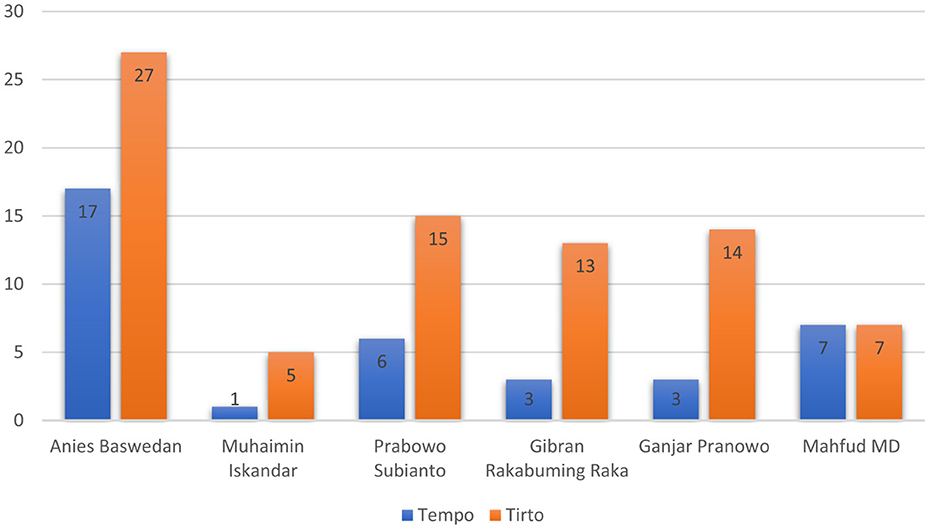

Figure 3 shows the number of disinformation issues aimed at the 2024 Indonesian presidential and vice presidential candidates. Figure 3 shows data from Tempo and Tirto taken throughout June-November 2023. Data from Tirto, from around 240 fact-check articles (40 articles per month) during that period, showed 71 articles about fact-checking related to the election. For Tempo, there were 30 fact-check articles related to the election. Then, from these articles, Tirto recorded 102 hoax uploads about the election discussed in the 71 Tirto fact-check articles above. At the same time, 41 hoax uploads about the election were discussed in 30 Tempo articles (Akbar, 2024).

Figure 3. Number of disinformation issues to candidates. Source: Akbar (2024).

Based on the data, it was found that the Presidential candidate was more often “targeted” than the Vice Presidential candidate. Anies Baswedan, Presidential candidate number 01, was most often mentioned in various disinformation content. Of the 71 Tirto fact-check articles, 27 or 38% were related to Anies Baswedan. Meanwhile, on the Tempo fact-check channel, Anies Baswedan was reported 17 times (around 55.67%) out of 30 articles.

Of the total, Prabowo Subianto and Ganjar Pranowo were seen following Anies Baswedan, both in Tirto and Tempo fact-checks. The Vice Presidential candidates tended to be less discussed than the Presidential candidates, except for Gibran Rakabiming Raka (Vice Presidential candidate number 2), whose number was only one number below Ganjar Pranowo (Presidential candidate number 3). The large amount of disinformation about Gibran Rakabuming Raka is perhaps related to his controversial nomination process, such as the aftermath of the amendment to the Law on Elections, and the Election Organizer Honorary Council (DKPP) which sentenced the Chairman of the General Election Commission (KPU) Hasyim Asy'ari and six other members of violating the code of ethics for accepting Gibran Rakabuming Raka's registration as a candidate for Vice President in the 2024 Election. In addition, there is the Constitutional Court Honorary Council (MKMK) which previously stated that the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court (MK) Anwar Usman (Gibran Rakabuming Raka's uncle) was proven to have committed serious violations of the code of ethics and the behavior of constitutional judges in deciding on the amendment to the Election Law (Akbar, 2024).

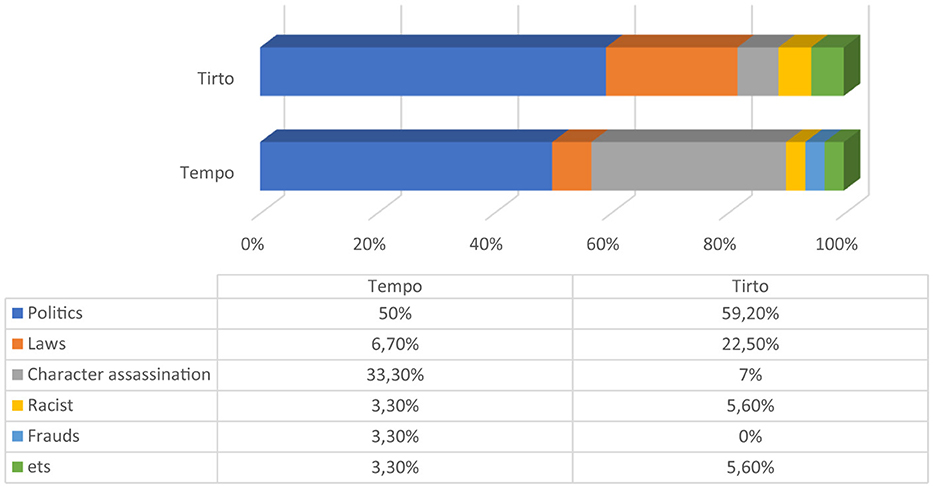

Looking at the classification of issues from Tirto's fact-checking articles in Figure 4, the most were about political issues. Of the total 71 fact-checking articles in Tirto related to the 2024 Election issue, 42 of them focused on political issues, followed by legal issues (such as disqualification, bribery, and corruption), character assassination, ethnicity, religion, race, and inter-group conflicts (SARA), with the remaining issues accounting for the rest. In Tempo, half of the 30 Tempo fact-checking articles related to the 2024 Election discussed hoaxes that touched on political issues. However, the percentage of disinformation with the theme of character assassination of presidential and vice presidential candidates was found to be higher, especially in Tempo sources. Considering the period from June to November 2023, which is primarily the preparation period for determining presidential and vice presidential candidates, it is not surprising that many hoaxes are found around political issues. Especially related to the determination of candidate pairs or support from several parties for certain presidential candidates.

Figure 4. Classification of disinformation issues. Source: Processed by the author based on tempo and tirto data (2025).

The data in Table 1 shows the disinformation narratives aimed at the candidates. The data found that the candidate pair Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar were more frequently targeted with disinformation narratives involving character assassination. The character assassination in question is the narrative attacking the person, starting from accusations of mental health, being arrested by the police, and being a suspect by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). Then, candidate pair number 02, Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka, were more attacked with narratives regarding political issues. The narratives include being prohibited from running for president and vice president, being disqualified, and working on programs when elected, among others. Meanwhile, candidate pair number 03, Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD, were attacked with two narratives, namely politics and character assassination.

The problem is that, according to a survey conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Safer Internet Lab (SAIL), more than 42% of Indonesians believe in disinformation about the 2024 election. CSIS and SAIL surveyed from September 4 to September 10, 2023, with a sample of 1,320 respondents spread across 34 provinces, yielding a margin of error of approximately 2.7% at a 95% confidence level. Researchers tested false information verified as false or fake news by the CekFakta Coalition. This information is often presented repeatedly or has a clear pattern. Arya also revealed several false facts that were asked of respondents, such as the existence of deception of the number of voters, KPU members who were not neutral, ballots that had been marked, ballots that had been stolen, fake ID cards in the election, Chinese foreign workers as voters, and the 2024 election being postponed (Galuh, 2023).

4.2 Disinformation spread patterns

Discussing the digital realm and public sentiment, Associate Professor of Public Policy and Management program at Monash University Indonesia, Ika Karlina Idris, explained that social media is a marketplace of attention, where content creators, buzzer deployment, and advertising spending efforts are carried out to get attention from netizens. If someone feels that the value of the content presented is suitable, including disinformation and misinformation, the content has the potential to shape the perception of the content user (Tempo.co, 2022).

Finally, because they have paid attention to the content, it is at the top of their minds, and people tend to get trapped in a “filter bubble” because they are increasingly exposed to similar content. In the context of the Election, the use of the digital realm as a “weapon” for spreading information is now increasingly massive. A striking difference occurred between the 2019 Election and the 2024 Election, namely the increasing number of micro-influencers or accounts with minimal followers. In 2019, the main echoers tended to be large accounts, then amplified by other small accounts. However, in 2024, social media algorithms (such as TikTok) allow small accounts to perch on the For Your Page (FYP) homepage with great exposure potential (Tempo.co, 2024).

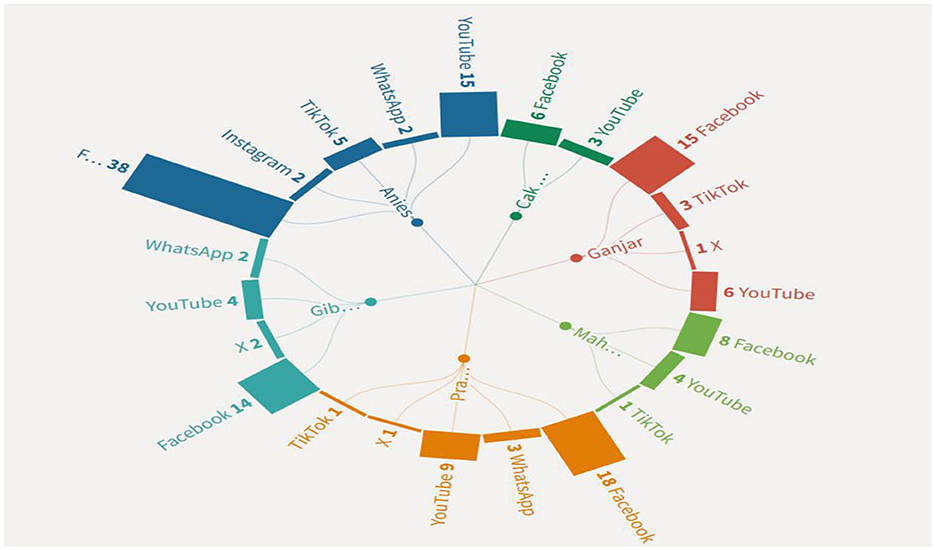

Regarding the large number of new voters from Gen Z in the 2024 Election and the rampant disinformation, Wawan Heru Suyatmiko, Deputy Secretary General of Transparency International Indonesia, said that being technologically literate is important. However, this must be accompanied by political awareness, which he said is still a big question mark in Indonesia. New voters, according to him, need to be historically literate and study the track record of each candidate, be it for president, vice president, or members of the council. In addition, he emphasized that new voters must also be open to the existing facts so that they can avoid believing post-truth information (Galuh, 2023). Figure 5 shows disinformation attacking presidential and vice presidential candidates in the 2024 general election—data processed from fact-checking articles conducted by Tirto and Tempo from June to November 2023.

Figure 5. Distribution of disinformation for candidates. Source: Akbar (2024).

Disinformation, or often referred to as hoaxes, has become a recurring problem in the 2024 Election, as happened in the 2019 Election. The Indonesian Anti-Slander Society (Mafindo) noted that 2,330 hoaxes were circulating throughout 2023. Of that number, 1,292 hoaxes, or around 55% of the total hoaxes, were identified as political hoaxes. This figure has doubled compared to similar hoaxes found during the 2019 Election, which was 644 hoaxes. Furthermore, according to Mafindo data, all presidential and vice presidential candidate pairs are the main targets of political hoaxes. Hoaxes about them are positive (exaggerating the candidate), and some are negative (attacking or slandering the candidate) (Mafindo, 2024).

The data in Figure 5 shows that Facebook is the most widely used social media platform for spreading disinformation to candidates in the 2024 election. Then followed by other social media such as YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter. The data in Figure 5 confirms that all candidates, both presidential and vice presidential candidates, received their hoax attacks. The difference is only in the intensity of the hoaxes on each social media. Anies Baswedan, Prabowo Subianto, Ganjar Pranowo, and Mahfud MD received the most disinformation attacks on Facebook, while Muhaimin Iskandar was higher on YouTube.

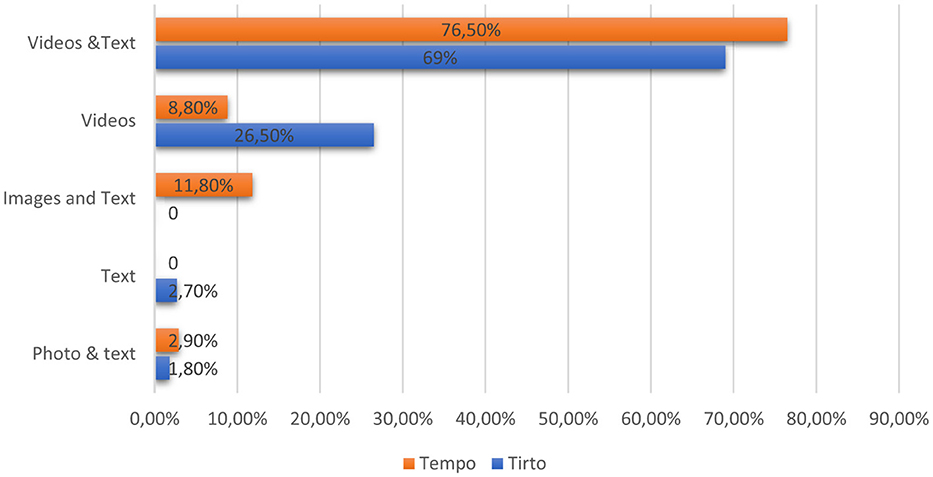

Minister of Communication and Information (Menkominfo) Budi Arie Setiadi said that hoaxes with the issue of the 2024 General Election increased almost 10 times in the past year. Budi said the increase in hoaxes related to the election issue was increasingly significant in July 2023 and continued to increase until October 2023. Even in the latest data from the Ministry of Communication and Information for October 27, 2023, three new hoaxes were found, indicating that the spread of hoaxes related to the election was heating up. The spread of false information related to the five-yearly democratic party was mostly found through social media, especially on Facebook, the first social media created by Meta Group. However, hoaxes related to the election were also found on social media such as TikTok, YouTube, SnackVideo, Twitter, and Instagram (Tempo.co, 2023). In line with this, the data in Figure 6 shows the format of disinformation spread through these social media.

Figure 6. Disinformation formats on social media. Source: Processed by the author based on tempo and tirto data (2025).

Figure 6 shows that the most dominant disinformation format spread through social media in the 2024 election based on data from Tempo and Tirto id is video format accompanied by text. This explains that the younger social media channels that spread this format are Facebook, YouTube and TikTok. While other formats are also seen such as videos, images accompanied by text and so on. Hoax is false or misleading information that is spread intentionally or unintentionally to deceive, influence opinion, or create confusion among the public. These fake attacks often appear in various forms, including fake news, images or videos that are edited very convincingly but contain false information, and information disturbances. There are three categories of information disturbances, namely misinformation (the unintentional spread of wrong information), disinformation (the spread of false information with malicious intent), and malinformation (the deliberate use of information to harm others) (Kompasiana, 2024b).

Furthermore, a manufacturer of antivirus products and software, Kaspersky, issued a warning about the dangers of the circulation of deepfake content ahead of the election. Deepfake is video and audio content that has been manipulated using artificial intelligence. As quoted from the Antara news agency on October 9, 2023, Genie Sugene Gan, Head of Government Affairs and Public Policy for Kaspersky for the Asia-Pacific, Japan, Middle East, Turkey and Africa Region, said: “Digital threats in the form of SMS, phishing emails, fake videos, and malicious sites must be anticipated during the election season in Indonesia next year. It is also important for people here to be aware of malicious content that they may encounter online during this period.” Antara also wrote that Kaspersky revealed that there was significant demand for deepfake creation. The price of a deepfake video per minute, according to Kaspersky, ranges from 300 to 20,000 US dollars, or around Rp. 4.7 million to Rp. 316 million (Galuh, 2023).

4.3 The impact of disinformation

In the internet era, socio-political polarization has become a major threat to democracy. This phenomenon, exacerbated by social media algorithms, causes differences of opinion and stops constructive discussions. When people are trapped in a filter bubble, they tend to only receive information that supports their beliefs and do not have the opportunity to see other perspectives. This causes a disorderly discussion space, where different opinions are often seen as threats rather than opportunities to speak (Kompasiana, 2024a).

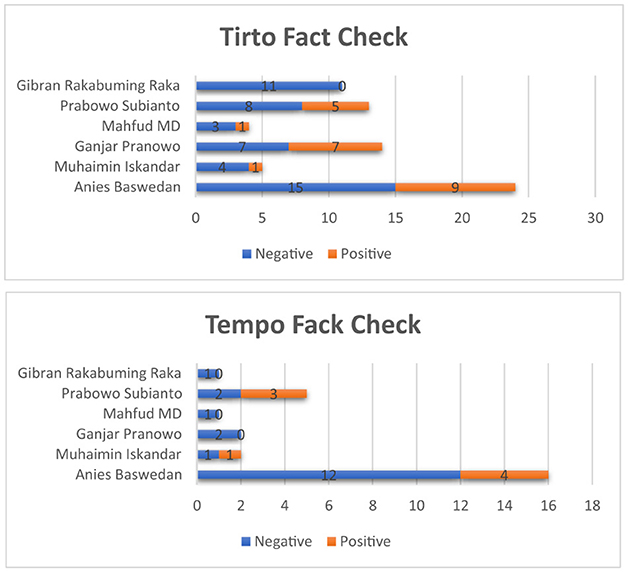

In addition, disinformation that spreads on social media only makes things worse. Disinformation spreads faster than the truth, especially stories that contain emotions such as fear or anger. The polarization driven by this disinformation affects the social relations of communities and individual political choices. Basically, differences of opinion are needed to promote new policies. However, political and social stability can be disrupted when disagreements develop into unresolvable conflicts. Indonesia, as a principled country, needs a more rational way to deal with these differences. Uncontrolled polarization can cause differences that are difficult to bridge and threaten social balance (Kompasiana, 2024a). The data in Figure 7 shows sentiment toward candidates in the 2024 election due to the spread of disinformation.

Figure 7. Sentiment of disinformation for candidates. Source: Akbar (2024).

In terms of sentiment toward the presidential and vice presidential candidates, most of the disinformation posts analyzed by Tirto were negative. For Anies Baswedan, the most talked about a presidential candidate in disinformation posts, 62.5% of the content was negative, or 15 topics. Meanwhile, the remaining 9 topics, or 37.5%, were positive. An example of a positive hoax claim related to Anies Baswedan is the claim of a crowd of residents in Kalimantan welcoming Anies. This claim circulated in August 2023. This video turned out to be a recording of the Regional Jamboree event held by Yamaha RX-King Indonesia, the Special Region of Yogyakarta Board (kompas.com, 2023).

Ganjar Pranowo was the second most discussed, with 14 disinformation topics. Interestingly, the number of disinformation topics with positive sentiment toward Ganjar Pranowo was balanced with his negative sentiment. Prabowo Subianto then followed with 13 disinformation topics, with a proportion of 8 topics with negative sentiment, and 5 topics with positive sentiment in the period June-November 2023. A similar trend was also seen in Tempo's disinformation uploads based on the topics and number of media fact-check articles. Of the total 30 hoaxes, most, 73.3%, contained negative sentiment toward the presidential/vice presidential candidates, and 26.6% contained positive sentiment. The circulation of disinformation has, in fact, had an impact on the sentiment reaped by the presidential candidates. Based on the data in Figure 5, it was found that the number of hoaxes targeting Anies Baswedan is directly proportional to his negative sentiment.

According to Drone Emprit's monitoring of online media and social media throughout June-November 2023, the percentage of negative sentiment received by Anies Baswedan was always fatter than that of Ganjar Pranowo and Prabowo Subianto. In June 2023, 25% of conversations about Anies in online media and social media tended to be negative, 57% were positive, and the rest were neutral. As a comparison, negative sentiment toward Prabowo and Ganjar was only 5% and 2%, respectively. However, this was reversed when entering the candidate debate period. Drone Emprit founder Ismail Fahmi stated that based on the results of the analysis of netizen conversation service providers on social media, presidential candidate number 1, Anies Baswedan, was the most discussed on social media compared to presidential candidate number 2, Prabowo Subianto and presidential candidate number 3, Ganjar Pranowo. The results of Drone Emprit's analysis showed that netizen conversations on Twitter or X regarding Anies Baswedan reached 61 thousand, while Prabowo 40 thousand, and Ganjar 42 thousand (Tempo.co, 2024).

5 Discussion

According to Starbird et al. (2019), disinformation is defined as intentionally planted and/or disseminated inaccurate or misleading content for a specified aim, frequently political advantage. Disinformation often operates as a campaign rather than just a single story or content. Disinforming campaigns frequently involve the efforts of “unwitting agents,” who might not be completely aware of their participation, even if they are usually started by witting actors or “agents.” Drawing on this knowledge, Rid (2020) emphasizes how disinformation campaigns can be incorporated into and utilized by otherwise natural political activism. Recent work has additionally highlighted the participatory nature of modern propaganda and conceptualized online disinformation as taking place through collaborations between witting agents and unwitting crowds (Wanless and Berk, 2021; Asmolov, 2019).

Regarding the sources of disinformation, fake news usually increases exponentially during election seasons (Waisbord, 2018). As stated by Shin et al. (2017), during the 2012 US elections, false information was widely spread via Twitter, especially among politically polarized voters. The 2016 US elections are another clear example of misinformation originating from social media. Still, in that case, it was also largely orchestrated by foreign powers that managed to influence the election campaign in an unwanted way (Jamieson, 2020).

However, in the 2020 US elections, the sources of disinformation that attracted the most attention of fact-checkers were those represented by social network users, the candidates themselves, and the traditional media. Therefore, in this case, no foreign power following a planned and sustained disinformation strategy over time was involved, in accordance with the concept of “organized disinformation” used in international relations. In the 2020 election, the only messages analyzed by international fact-checkers that came from institutional sources were those issued by the White House itself (Ferrara et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2021).

Research from Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) explains that In the aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election, it was alleged that disinformation might have been pivotal in the election of President Trump. Likewise, research from Benaissa Pedriza (2021) explains that the most widely used to spread misleading messages is social media, which is 67.4%. Candidates rely on using classic disinformation strategies through traditional media, although the highest level of disinformation occurs when conspiratorial disinformation is spread through social media. In line with this, the findings of this study also explain that in the 2024 election in Indonesia, social media had a significant role in the spread of disinformation. Each candidate becomes a victim of disinformation attacks on social media by attacking various issues, ranging from character assassination and political issues. Meanwhile, research from Rossini et al. (2021) two classic tactics used by candidates and their campaign team members during the 2020 election campaign in the United States are praising the candidate's goodness and spreading false claims against political opponents. Research from Cano-Orón et al. (2021) explains that actors who implemented disinformation strategies were not limited to extreme right groups in the ideological spectrum of major national political parties during the campaign leading up to the Spanish general election in 2019.

Furthermore, research from Dan et al. (2021) explains that the ease of technology plays a central role in the construction and spread of disinformation. Audio-visual cues make disinformation more credible and can help embed false storylines realistically in the digital media ecology. As audio-visual manipulation and engineering techniques become more widespread and accessible to everyone, future research should consider the modalities of disinformation, their long-term effects, and their embedding in a fragmented media ecology. This is different from the findings of this study which found that the pattern of disinformation that occurred in the 2024 election was more dominant on social media channels that support the emergence of video and text characters such as Facebook, Youtube and Tiktok. This is confirmed by the highest form of disinformation format, which is video accompanied by text.

According to a study by Shearer (2018), social networks are the channel preferred to become informed for the majority of Americans in a percentage of 20% compared to 16% of citizens who turn to print media. A situation that was used during the 2016 US general election to turn social networks into channels for the massive distribution of fake news and to transform them into a powerful propaganda instrument (Journell, 2017). According to a study carried out by Paniagua et al. (2020) on the disinformation reported during the 2019 general election in Spain, the main hoaxes detected by fact-checkers came mostly from social networks (Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp). Only a small number came from websites identified as well-known disinformation sites, while the rest came from partisan or satirical websites (Molina-Cañabate and Magallón-Rosa, 2021). In their study on the 2019 presidential election in Uruguay, they also found that social networks were the channel through which the greatest volume of disinformation was distributed (Facebook reached 44% above Twitter (2.9%) and WhatsApp (19.6%); the three of them represented 86.6% of the total disinformation).

Furthermore, this study found a negative impact of disinformation on candidates in their participation in the 2024 election. The negative impact is in the form of a bad image of candidates in society, this is because most Indonesian people still believe in disinformation spread in society. According to research from Facciani et al. (2023) explains that the spread of disinformation and information in Indonesia and Malaysia has caused socio-political divisions and mass protests. Indonesian society is at a level where it cannot distinguish between real and unreal information, while Malaysian society has a slightly greater ability to do so.

6 Conclusion

This study concludes that in the 2024 election in Indonesia, social media played a significant role in the spread of disinformation. Each candidate became a victim of disinformation attacks on social media by attacking from the side of character assassination and political issues. Then, the pattern of disinformation that occurred in the 2024 election was more dominant on social media channels that support the emergence of video and text characters, such as Facebook, YouTube and Tiktok. This is confirmed by the highest form of disinformation format, which is video accompanied by text. Furthermore, the spread of disinformation to candidates has a negative impact on their participation in the 2024 election. The negative impact is in the form of a bad image of the candidate in the eyes of the public.

Based on this, it is the basis of the argument of this study that digital technology intervention is very significant in influencing candidates in the election contest. More than that, social media is a sophisticated facility for the spread of disinformation to be utilized by the political actor team as a form of electoral attack effort. Then, this study has limitations it only focuses on issues, patterns of distribution and the impact of disinformation but has not discussed in more depth its influence on candidate electability. Therefore, recommendations for further research to be able to focus on this through quantitative method facilities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DS: Methodology, Conceptualization, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MY: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation. MW: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Universitas Jambi for providing this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akbar, A. (2024). Hoaks Pilpres: Anies Diburu, Masyarakat Dibohongi. Available online at: https://tirto.id/hoaks-pilpres-anies-diburu-masyarakat-dibohongi-gWeH (Accessed January 16, 2025).

Allcott, H., and Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. J. Econ. Perspect. 31, 211–236. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Asmolov, G. (2019). The effects of participatory propaganda: from socialization to internalization of conflicts. J. Des. Sci. 6:122. doi: 10.21428/7808da6b.833c9940

Bakir, V., and McStay, A. (2018). Fake news and the economy of emotions. Digit. J. 6, 154–175. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2017.1345645

Bargaoanu, A., and Radu, L. (2018). Fake news or disinformation 2.0-some insights into Romanians' digital behaviour. Romanian J. Eur. Aff. 18, 24.

Benaissa Pedriza, S. (2021). Sources, channels and strategies of disinformation in the 2020 US election: social networks, traditional media and political candidates. Journal. Media 2, 605–624. doi: 10.3390/journalmedia2040036

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From Production to Produsage, Vol. 45. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

Cano-Orón, L., Calvo, D., López García, G., and Baviera, T. (2021). Disinformation in Facebook Ads in the 2019 Spanish General Election Campaigns. Media Commun. 9, 217–228. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i1.3335

Carpentier, N. (2011). Media and Participation: A Site of Ideological-Democratic Struggle. Bristol: Intellect.

Carral, U., Tuñón, J., and Elías, C. (2023). Populism, cyberdemocracy and disinformation: analysis of the social media strategies of the french extreme right in the 2014 and 2019 European elections. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-01507-2

Chaudhry, H. N., Javed, Y., Kulsoom, F., Mehmood, Z., Khan, Z. I., Shoaib, U., et al. (2021). Sentiment analysis of before and after elections: twitter data of U.S. election 2020. Electronics.10:2082. doi: 10.3390/electronics10172082

Chaves, M., and Braga, A. (2019). Theagendaof Disinformation: ‘Fake News' and Membership Categorization Analysis in the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Elections. Brazil. Journal. Res. 15, 474–495. doi: 10.25200/BJR.v15n3.2019.1187

Couldry, N., and Hepp, A. (2022). “Media and the social construction of reality,” in The Oxford Handbook of Digital Media Sociology (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 27–39.

Dan, V., Paris, B., Donovan, J., Hameleers, M., Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., et al. (2021). Visual mis-and disinformation, social media, and democracy. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 98, 641–664. doi: 10.1177/10776990211035395

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dommett, K., and Power, S. (2019). The political economy of facebook advertising: election spending, regulation and targeting online. Politic. Q. 90, 257–265. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12687

Eck, N. J. V., and Waltman, L. (2013). VOSviewer Manual, vol. 1 (Leiden: Univeristeit Leiden), 1–53.

Eck, N. V., and Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84, 523–538. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Facciani, M., Idris, I. K., and Weninger, T. (2023). Comparison of news literacy, media consumption, and trust between Indonesia and Malaysia. Asian J. Media Commun. 7:83100. doi: 10.20885/asjmc.vol7.iss2.art2

Fallis, D. (2014). “The varieties of disinformation BT,” in The Philosophy of Information Quality, eds. L. Floridi and P. Illari (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 135–161.

Ferrara, E., Chang, H., Chen, E., Muric, G., and Patel, J. (2020). Characterizing social media manipulation in the 2020 us presidential election. First Monday. 25:132. doi: 10.5210/fm.v25i11.11431

Fuller, M. (2005). Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Cambridge: MIT press.

Galuh, L. (2023). Survei: Hampir 50% Warga Percaya Disinformasi Pemilu 2024. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/id/survei-hampir-50-persen-warga-percayadisinformasi-pemilu-2024/a-67153067 (Accessed January 18, 2025).

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. Media Technol. Essays Commun. Material. Soc. 167:167. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262525374.003.0009

Gray, J., Bounegru, L., and Venturini, T. (2020). ‘Fake News' as Infrastructural Uncanny. New Media Soc. 22, 317–341. doi: 10.1177/1461444819856912

Guess, A. M., and Lyons, B. A. (2020). Misinformation, Disinformation, and Online Propaganda. Social Media Democr. State Field Prospect. Reform 10, 10–33. doi: 10.1017/9781108890960.003

Hannan, J. (2018). Trolling ourselves to death? Social media and post-truth politics. Eur. J. Commun. 33, 214–226. doi: 10.1177/0267323118760323

Hansen, I., and Lim, D. J. (2019). Doxing democracy: influencing elections via cyber voter interference. Contempor. Polit. 25, 150–171. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2018.1493629

Hsieh, H-. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Jamieson, K. H. (2020). Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President: What We Don't, Can't, and Do Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., and Green, J. (2013). Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Journell, W. (2017). Fake news, alternative facts, and trump: teaching social studies in a post-truth era. Soc. Stud. J. 37, 8–21.

Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika (2024). Jaga Ruang Digital, Menkominfo: Kami Tangani 203 Isu Hoaks Pemilu 2024. Available online at: https://www.kominfo.go.id/content/detail/53920/siaran-pers-no-03hmkominfo012024-tentang-jaga-ruangdigital-menkominfo-kami-tangani-203-isu-hoaks-pemilu-2024/0/siaran_pers (Accessed January 18, 2025).

Kim, Y. M., Hsu, J., Neiman, D., Kou, C., Bankston, L., Kim, S. Y., et al. (2018). The stealth media? Groups and targets behind divisive issue campaigns on facebook. Polit. Commun. 35, 515–541. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2018.1476425

kompas.com (2023). [HOAKS] Video Kerumunan Di Kalimantan Dukung Salah Satu Capres. Available online at: https://www.kompas.com/cekfakta/read/2023/08/19/171737282/hoaks-video-kerumunan-di-kalimantan-dukung-salah-satu-capres (Accessed January 16, 2025).

Kompasiana (2024a). Ketegangan Polarisasi Dan Disinformasi Dalam Pesta Demokrasi Digital Pada Pemilu 2024. Available online at: https://www.kompasiana.com/deatanyy1858/6783d83034777c13f217cb52/ketegangan-polarisasi-dan-disinformasidalam-pesta-demokrasi-digital-pada-pemilu-2024 (Accessed January 17, 2025).

Kompasiana (2024b). Pengaruh Hoaks Terhadap Elektabilitas Pasangan Calon Anies-Imin Di Masa Pemilu. Available online at: https://www.kompasiana.com/irennegrace/66f4071fed6415133b510592/pengaruh-hoaks-terhadap-elektabilitas-pasangan-calonanies-imin-di-masa-pemilu (Accessed January 30, 2025).

KPU RI (2023a). KPU Tetapkan Tiga Pasangan Calon Presiden Dan Wakil Presiden 2024. Available online at: https://www.kpu.go.id/berita/baca/12081/kpu-tetapkantiga-pasangan-calon-presiden-dan-wakil-presiden-pemilu-2024 (Accessed January 17, 2025).

KPU RI (2023b). Tahapan Dan Jadwal Penyelenggaraan Pemilu Tahun 2024. Available online at: https://infopemilu.kpu.go.id/Pemilu/Peserta_pemilu (Accessed January 17, 2025).

Kreiss, D., and Mcgregor, S. C. (2018). Technology firms shape political communication: the work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google with campaigns during the 2016 U.S. presidential cycle. Polit. Commun. 35, 155–177. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1364814

Levinson, N. S. (2020). Technology and Development in International Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lukito, J. (2020). Coordinating a multi-platform disinformation campaign: internet research agency activity on three U.S. social media platforms, 2015 to 2017. Polit. Commun. 37, 238–255. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1661889

Mafindo (2024). Siaran Pers Mafindo: Hoaks Politik Meningkat Tajam Jelang Pemilu 2024, Ganggu Demokrasi Indonesia. Available online at: https://mafindo.or.id/2024/02/02/siaran-pers-mafindo-hoaks-politik-meningkat-tajam-jelang-pemilu-2024-ganggudemokrasi-indones (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Mauk, M., and Grömping, M. (2023). Online disinformation predicts inaccurate beliefs about election fairness among both winners and losers. Comp. Polit. Stud. 57, 965–998. doi: 10.1177/00104140231193008

Molina-Cañabate, J. P., and Magallón-Rosa, R. (2021). Desinformación y Fact-Checking En Las Elecciones Uruguayas de 2019. El Caso de Verificado Uruguay. Perspectivas de La Comunicación 14, 89–112. doi: 10.4067/S0718-48672021000100089

Paniagua, F., Seoane Pérez, F., and Magallón, R. (2020). An anatomy of the electoral hoax: political disinformation in Spain's 2019 general election campaign. CIDOB d'Afers Internacionals 124, 123–145.

Pérez-Curiel, C., and Rivas-de-Roca, R. (2022). Exploring populism in times of crisis: an analysis of disinformation in the european context during the US elections. Journal. Media 3, 144–156. doi: 10.3390/journalmedia3010012

Postman, L. (1970). “Experimental analysis of learning to learn,” in Presidential Address to the Western Psychological Association in 1968, BT—Psychology of Learning and Motivation Spence, vol. 3, eds. G. H. Bower and J. Taylor (Cambridge: Academic Press), 241–297.

Power Wogu, I. A., Njie, S. N. N., Katende, J. O., Ukagba, G. U., Edogiawerie, M. O., Misra, S., et al. (2020). The social media, politics of disinformation in established hegemonies, and the role of technological innovations in 21st century elections: The road map to US 2020 presidential elections. Int. J. Electron. Govern. Res. 16, 65–84. doi: 10.4018/IJEGR.2020070104

Ribeiro, F. N., Saha, K., Babaei, M., Henrique, L., Messias, J., Benevenuto, F., et al. (2019). “On microtargeting socially divisive ads: a case study of russia-linked ad campaigns on facebook,” in Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAT*'19 (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 140–149.

Rid, T. (2020). Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rossini, P., Stromer-Galley, J., and Korsunska, A. (2021). More than ‘Fake News'? The media as a malicious gatekeeper and a bully in the discourse of candidates in the 2020 US presidential election. J. Lang. Polit. 20, 676–695. doi: 10.1075/jlp.21033.ros

Shearer, E. (2018). Social Media Outpaces Print Newspapers in the U.S. as a News Source. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/12/10/social-media-outpaces-print-newspapers-in-the-u-s-as-a-news-source/ (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Shin, J., Jian, L., Driscoll, K., and Bar, F. (2017). Political rumoring on Twitter during the 2012 US presidential election: rumor diffusion and correction. New Media Soc. 19, 1214–1235. doi: 10.1177/1461444816634054

Starbird, K., Arif, A., and Wilson, T. (2019). “Disinformation as collaborative work: surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations,” in Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3 (New York, NY: ACM), 1–26.

Subekti, D., Nurmandi, A., and Mutiarin, D. (2022). Mapping publication trend of political parties campaign in social media: a bibliometric analysis. J. Polit. Market. 24, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2022.2104424

Tempo.co (2022). Literasi Digital Ala Pemerintah. Available online at: https://www.tempo.co/kolom/penghentian-hoaks-dan-apa-manfaat-literasi-digital-pemerintah-jokowi839864 (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Tempo.co (2023). Facebook Terbanyak Muat Hoaks Pemilu, Budi Arie: Ada Disinformasi Prabowo and Ganjar. Available online at: https://www.tempo.co/sains/facebookterbanyak-muat-hoaks-pemilu-budi-arie-ada-disinformasi-prabowo-ganjar-127680 (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Tempo.co (2024). Drone Emprit Sebut Anies Paling Banyak Diperbicangkan Dan Dapat Sentimen Positif Tertinggi Usai Debat. Available at: https://www.tempo.co/politik/drone-emprit-sebut-anies-paling-banyak-diperbicangkan-dan-dapatsentimen-positif-tertinggi-usai-debat-100291 (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Tufekci, Z. (2015). Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: emergent challenges of computational agency. J. Telecommun. High Tech Law 13, 203–216.

Waisbord, S. (2018). The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Commun. Res. Pract. 4, 17–34. doi: 10.1080/22041451.2018.1428928

Wanless, A., and Berk, M. (2021). Participatory propaganda: the engagement of audiences in the spread of persuasive communications. Soc. Media Soc. Order 2021, 111–139. doi: 10.2478/9788366675612-009

Wibawana, W. A. (2024). Masa Kampanye Pemilu 2024 Sampai Kapan? Simak Lagi Jadwalnya. Available at: https://news.detik.com/pemilu/d-7173105/masa-kampanyepemilu-2024-sampai-kapan-simak-lagi-jadwalnya (Accessed January 25, 2025).

Keywords: social media, disinformation, candidate, Indonesia, presidential election

Citation: Subekti D, Yusuf M, Saadah M and Wahid M (2025) Social media and disinformation for candidates: the evidence in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1625535. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1625535

Received: 09 May 2025; Accepted: 23 June 2025;

Published: 17 July 2025.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Sulaimon Adigun Muse, Lagos State University of Education LASUED, NigeriaArif Zainudin, Universitas Pancasakti Tegal, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Subekti, Yusuf, Saadah and Wahid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dimas Subekti, ZGltYXNzdWJla3RpMDVAdW5qYS5hYy5pZA==

Dimas Subekti

Dimas Subekti M. Yusuf1

M. Yusuf1