Abstract

The last decade has witnessed a rise in misinformation and disinformation. Countries and individuals have been impacted by both and Nigeria's elections have not been left out. Rhetoric has gone beyond being a tool for shaping public opinion, to one used to promote fear, divisiveness and violence, especially in countries with ethnic and religious diversity. During the 2019 Nigerian elections, rhetoric was used to spread misinformation and disinformation about opposing candidates and parties. The 2023 elections took it further, using specific narratives like “Lagos is Yoruba land” to amplify existing ethnic, religious, and political differences, during the elections in Lagos. Adopting Political Communication and Social Identity as theoretical framework and using a Thematic analysis, the study assessed the strategies used to package ethnic and religious rhetorics in the social media political posts on X (formerly) Twitter and Facebook concerning the 2023 Lagos Governorship elections and how this influenced other social media users. Findings indicate that there is a major gap in terms of the responsibilities of political actors to do no harm and how they used rhetorics in the 2023 election campaigns in Lagos State. The actors weaponised social and political identity majorly, using history, threats and shaming to achieve their aim. Additionally, the posts contained triggering words/phrases and this also reflected in the responses to some of the posts. The persistent use of ethnicity and negative identity based political rhetoric if left unchecked in future elections will resuscitate old wounds, deepen societal fractures, which can be traced to the early years of the country. This in turn threatens the development of strong democratic institutions as the electorate weigh self-preservation over exercising their rights to vote and participate in the process. The next election cannot be allowed to shift from democratic persuasion to cause even lower voter turnout through the use of fear.

1 Introduction

In 2017, Salil Shetty, the then secretary general of Amnesty International, stated that “… too many leaders have adopted a dehumanising agenda for political expediency, instead of fighting for people's rights.” He felt that the limits of what society finds acceptable “has shifted” and not for the better, especially with politicians constantly and boldly using “all sorts of hateful rhetoric based on people's identity: misogyny, racism and homophobia” (BBC, 2017). Amnesty International (2017) echoes this same perspective, calling it a “toxic, dehumanising ‘us vs. them' rhetoric,” which is creating and has indeed created a more divided world. This is quite visible in developing countries like Nigeria, where the first visible use of this brand of rhetoric was during the 2019 elections; politicians spread their messages using both traditional media and via the internet for faster and widespread dissemination. Since then, use of negative rhetoric has pervaded the Nigerian political communication space, causing more harm and damage. Indeed, there have been concerns about how to deal with the issue, which is one reason that inspired the paper.

Meanwhile, platforms where these rhetorics are disseminated are meant to create cohesion and not divide, providing citizens with necessary information to aid their daily decision making processes, choice of political candidates inclusive. These platforms hosted on the internet are generally perceived as enabling platforms for the free flow of information in any society, but this has come with a heavy price as it has been difficult controlling or regulating what gets uploaded and by whom. Despite some of its shortcomings, the internet has enabled responsible individuals to foster awareness of timely information, encourage political participation and engagement, where like-minded individuals are recruited for specific projects or mobilisation efforts and to protest bad policies and governance where needed to entrench accountability (Beacham et al., 2024, p. 5). Although these are positive functions, the internet has evolved, having many more digital media platforms and accompanied by a myriad of issues ranging from misinformation to disinformation, as well as fostering propaganda and dangerous ideologies and rhetoric (Olaniran and Williams, 2020, p. 77). Misinformation and disinformation have become tools used by political candidates and their supporters to “divide and conquer” political rivals and their followers and supporters in the Nigerian political space. While this may be present to varying degrees in developed societies, developing countries like Nigeria are in the thick of this menace, which has often degenerated into online fights among supporters of opposing candidates and political parties.

The challenges that come with using new media platforms for political communication possibly informs Hassan's (2023, p. 2) view that the digital space has become prolific for “manipulating” the mindsets of the public on important issues, while at the same time “mobbing” opposing views, especially in the civic and political space. It is an era that Lee (2019) described as the rise of “echo chambers” or “philtre bubbles.” Political candidates and or party chieftains are able to get supporters to their side using words that seem to align with that of their supporters. More and more individuals are focusing on news items and content that align with their preconceived views as opposed to being open to opposing perspectives. This has therefore led to a lot of partisan and polarising engagement with information/news items.

Asimakopoulos et al. (2025) have a slightly different view believing instead that these platforms hosted by the internet have lowered barriers in politics and political communication, increasing the number of people with access to share their views and thoughts on political inclinations and the state of governance in the country. This is instrumental when trying to influence the direction of governance.

Despite the positive outlook of Asimakopoulos et al. (2025), social networks have become tools wielded by some political enthusiasts, propagandists and strategists to intentionally fill the public sphere with twisted and or one-sided information, in a bid to either mislead participants or sway their cause of action. Lee describes these unreliable information as “digital wildfires” and posits that it is one of the greatest threats to governments and existing democracies anywhere. The lighters of these “digital wildfires” do this using audio visual and artificial intelligence tools, to instigate unsuspecting and sometimes expectant internet users. Kurten (2025) expresses concern that when these twisted and one-sided information, disinformation and divisive rhetoric flood the information ecosystem, the important guardrails of any democratic society becomes “eroded,” thus preventing a peaceful electoral process and doubt in election results amongst other things. These was the fate of the 2023 Presidential elections in Nigeria. The “digital wildfires,” which included threats to political opponents was such that the physical turn-out was low and there were pockets of violence across the country.

Digital wildfires as highlighted above include the use of conflict rhetoric and disinformation, the latter of which the European Commission (2021) describes as “verifiably false or misleading information that is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public, and may cause public harm.” But the authors believe the proponents of disinformation are not just focused on economic gain. There is a strategic component of disinformation, which highlighted by Kurten (2025) describes the concept as “intentional and often strategic use of false information.” Disinformation is tactically used to disrupt the belief systems of an audience and serve as an “offensive counterintelligence” that ends up deceiving and manipulating audiences to act or react in a specific way.

While the first definition establishes a financial reason for the use of disinformation as a strategy, the second definition highlights an intentional deception of the public or a specific set of people to more often than not achieve selfish objectives by “dividing or driving wedges” in the camp of their political opponents. The purveyors of disinformation usually have negative reasons for pushing out those kinds of information. But particularly worrisome is the point raised by McGonagle (Hassan, 2023, p. 2) that disinformation is often presented and perceived as “news.” Lee (2019, p. 16) states that disinformation is political and damages most times the credibility and integrity of “an agency, entity or individual” and even groups, especially traditional media platforms. News ideally were viewed as tools to help individuals make informed life decisions, but when what individuals consider as news is intentional falsehood or twisted truths, then the output of their life decisions need to be reevaluated (Oji et al., 2024).

The quality of those decisions becomes questionable with news dissemination becoming an allcomers affair, with many players venturing into online news dissemination as news bloggers, without the prerequisite training, making it difficult to differentiate between them and legit online news sources and platforms. With blogs like Instablog, Legit.com and social networks becoming increasingly popular with the Nigerian market, Hassan (2023) states that disinformation moves lightning fast nowadays, “across multiple outlets and in many languages.” In essence, there are no more barriers or hindrances to the spread of false or manipulated information.

The use of disinformation in politics has been harmful with Hassan pointing out that political consultants working for and representing various political parties and whom he refers to as “soldiers of mouth” disseminate a blend of truth and lies just to sway or persuade people in favour of the political interests they represent. He emphasises that these “interests” are “weaponizing” information both online and offline. The information then becomes a tool for engaging a “divide and conquer” position against those not aligned with the interests of the user. This view is supported by Kurten (2025) who states that misinformation let loose in any society unintentionally destroys what is real and considered to be truth, while disinformation further fractures the realities and perceptions of truth in the society, leveraging them for nefarious purposes. The authors agree with this view, considering that in its present state, the Nigerian information ecosystem makes it difficult to decipher what is truth and what is false.

Gomez's (2018, p. 3) perspective that political rhetorics (messages) have evolved into opportunities for political strategists, campaigners and mobilizers to “divide” by targeting members of other groups and accusing them of being responsible for certain social problems in that society or just painting the impression of an “us vs. them” is only too real. It appeals to a sense of “group identity” and makes some people feel like they are not in the “good group.” They have become opportunists taking advantage of negative rhetoric without a care for who or what is destroyed. Rhetoric in itself is not bad; it is persuasion, which has become inseparable from politics, widely used by politicians and other key players in the space to “argue for their ideologies and or views.” Using rhetoric, politicians and the players in the space try to make themselves distinct from their counterparts, in order to convince the electorate that they deserve their support and not the competition. The downside of this strategy is that it creates divisions which lasts longer than the period of use.

This rhetorical strategy of using or creating conflict has been encouraged by offline and online platforms, with traditional news outlets also scouring online platforms for trending issues and disseminating same, oftentimes without proper verification or screening, preferring to push the headlines even when they are sensational and can cause divisions in society. Gomez states that this strategy is not new, at least not in American politics where it was a common feature even in the 1960s. The only difference she states, is that the divisive rhetorics at play now is more “negative and less civil.” An example in Nigeria is the rumour that spread just prior to and during the 2019 Nigerian general election, which was that “Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari was dead and the person in his place is a clone, a man named Jubrin from Sudan.” Using altered pictures, the news backed up their claim. It pit ethnic tribes against each other and political parties as well.

Perhaps the greatest proponent for the quick spread of disinformation and all the “weaponised rhetorics” is what Olaniran and Williams (2020) describe as the lack of censorship, which would have been a barrier to just anybody being a disseminator of news, something which traditional media outlets have. With no “gates” or form of control, individuals can take news items and shape them into a “weapon” of sorts to achieve their aim, which is to cause a lack of cohesion or unity among those in opposition to their stance.

As a result of this gap in “censorship” and curtailing of the negative use of conflict or divisive rhetorics, the last elections especially in Lagos State was not exempt from its use. Till date, there is still some tension between the Yorubas and Igbos, who were the major players on the giving and receiving end of this brand of rhetoric. In order to understand the Yoruba-Igbo dynamic that played up during the last Governorship elections in Lagos, it is important to describe the composition of Nigeria and Lagos's socio-political and economic context.

History of this tension can be traced to the larger political tensions plaguing Nigeria. Adegbami and Uche (2015, p. 59) explain that Nigeria is home to over 300 ethnic groups, about a thousand dialects and a variety of religious beliefs and inclinations to mention a few differences. Their view is supported by United Nations (2024), with the country described as a multi-ethnic and culturally diverse country having an estimated population of over 200 million people (Africa's largest population) and estimated to reach 237, 526, 782 by the end of 2025. The country operating a Federal system of government has 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory. Despite the number of ethnic groups, most people are more familiar with the three major ethnic groups of Yoruba, Hausa/Fulani and Igbo, who have from inception been on a collision course as they have grappled for control of the country's political and economic resource. This has grown into what continues today to be a hydra-headed monster affecting the nation.

1.1 Problem statement

Divisive rhetorics thrive in politics because digital platforms give them audience. Digital platforms (particularly, but not only social media) are widely used by any number of political actors to sow discord and create tensions, with serious potential consequences. Winans (2019, p. 3) believes that divisive rhetoric is malicious, deceptive and all about creating division and confusion. It can be adjudged to be present in political campaigns or messages when the candidates forcefully question “the intentions, patriotism, and morality of their opponents” in order to divide the electorate and swing the votes in the favour of their preferred candidate.

Beacham et al. (2024) explain that political actors have become extremely good at “weaponizing” information and messages during campaign periods, to create controlled chaos in the camp of the opposition, but it often leads to division and polarity. It has become a norm for politicians and their cronies to use negative rhetorics during election campaigns and Nigeria is no exception. The challenge is that the effects linger long after the use. For instance the use of divisive rhetorics in the 2023 elections has led to the continued “strained relationship between the Yorubas and the Igbos in Lagos” (Salau, 2023, December 11). Surprisingly, it ends up preventing citizens or the electorate from voting based on competence as they end up driven by “identity politics.”

This study intends to analyse the strategies used to package ethnic and religious rhetorics in the social media political posts on X (formerly) Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook concerning the 2023 Lagos Governorship elections to assess how this influenced the replies of individuals to the posts. The specific questions the study will attempt to answer include:

-

What is the background of the players in and behind the rhetorics that played out during the Lagos Governorship elections in 2023?

-

What were the types of divisive rhetorical strategies and triggers embedded in the political messages used in the Lagos Governorship elections in 2023?

-

How did internet users respond to the rhetorical strategies used in the Lagos Governorship elections in 2023?

-

What was the focus of the responses to the rhetorical strategies used in the Lagos Governorship elections in 2023?

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical framework: political communication as warfare and social identity theory

Political communication has become much more than an avenue to deploy information and messages about a politician's plans, agenda and policies to the electorate. It has become a battleground and only the strongest survive; or more often than not, those who are able to deploy the strategies of rhetorics to their own advantage (Koliechkin et al., 2024). As such, Forest (2021) states that the “weaponisation of information” in order to get power and influence is not new. It springs from the Chinese general and military theorist Sun Tzu who stated that the greatest skill in warfare is “…to subdue the enemy without fighting [with physical weapons or before any weapon is used].” This weapon of rhetorics has been deployed over the centuries, where parties try to influence the opposing side to their point-of-view.

Influence warfare was evident throughout World War II, as Joseph Goebbels and the Nazi regime deployed propaganda for their own purposes. The United States under President Franklin D. Roosevelt also opened the Office of War Information in 1942, to among other things tackle the efforts of their enemy and what they were saying using “various psychological and information operations” and supporting and strengthening the resolve the US soldiers on the battlefront.

Forest (2021, p. 13) posits that the digital age has redefined the level of political influence both globally and within countries. The digital platforms have become the mainstay for disseminating propaganda and ideologies worldwide. This is because in Koliechkin et al.'s (2024) view, the modern political terrain is defined by communication strategies targeted towards changing the way the public thinks and behaves and has the ability to increase or decrease social tension. Speech and communication are therefore key in any political campaign.

As such, in political warfare there are those who leverage digital platforms and the loyalty of their followership to push others to attack people with different mindsets or views, and this can scatter and affect the level of unity and cohesiveness in any society and affect the level of trust that citizens and the electorate have in political institutions. It is about undermining the targets to achieve the objectives of the person behind the weaponised information. As Davis (2023) and Wolfsfeld (2022) (cited in Koliechkin et al., 2024, p. 18409) posit, these platforms have become pivotal in swinging the direction of conflicts' and determining the emotional texture with which people respond to political communication. Platform users tend to swing in the direction of posts or views whose frames align with their beliefs.

The framing of these political communication messages can “either mobilise the public or increase levels of anxiety and social polarisation and conflicts.” The messages when framed negatively or embedded with polarising content can exacerbate existing tensions and concerns in the society. Wang and Wang (2024) state that “framing” is an essential and integral part of political campaign strategies and in this instance political campaigns and messages on both traditional and online platforms are no exception. The way content, opinions and ideologies are packaged and deployed as “fact” influences how society received and responds to them.

Some of the tools used in packaging the messages include lies, provocation, and deployment of deepfake videos and fake social media accounts to gaslight people whose views differ from theirs and enhance controversial viewpoints. Other strategies deployed in this digital political warfare include behaviour signalling (e.g., swarming or band wagoning), trolling, gaslighting, and other means by which the target is provoked into having an emotional response that typically overpowers their ability to behave rationally or logically. Clickbait, memes, and rage bait (for example) are additional ways to influence others via the internet.

The reason why these strategies are worrisome is that they activate the mindsets and triggers of people with “philtre bubbles” and “echo chambers,” making it difficult for them to be objective about the information sent out. These “bubbles and chambers” are tied to the sense of identity or belief that individuals have about themselves in relation to others, especially their political parties. Their social thermometer or identity becomes instrumental to how they react to the political messages they are exposed to. The architects of these messages understand this and know how to prime these individuals such that they react in the way they want.

Social identity according to Aghabi et al. (2017, p. 4) gives individuals “a shared and collective representation” or perspective of who they are and what their behaviour should be as a member of a group, and in relation to those not in the group, generally referred to as “out-groups.” Social identity is often described as a social construct developed based on how factors such as circumstances, including threats, frustrations and social and economic factors in that society affect the individual. It can thus be inferred that the individual's sense of self and their behaviour is tied to these aforementioned factors. Based on the tenets of social identity theory, the members differentiate themselves from other groups, have a standard for relating to competition and responding to antagonism; this can often result into intergroup conflict and or violence.

Whether in competition or collaboration, humans are inherently social (Strindberg, 2020, p. 14), and they develop their ethics or sense of right and wrong based on the interactions with others. These interactions can grow into shared experiences and world views that promote cohesion and unity or cause friction and conflict as individuals form cliques based on these shared experiences and views.

Developed by Henri Tajfle and John Turner, the Social Identity theory focuses on how these social engagements translate into relationships and conflict management between groups. Aghabi et al. (2017, p. 6) describe four ways by which social identity is formed: categorisation, the level or hierarchy at which the individual fits into the group; in-group positivity—the type of positive emotions and feelings that being a member of the group gives the individual; intergroup comparison—how the individual ranks the group or weight assigned to the group vis a vis others based on a comparison of key factors and out-group hostility—the negative reactions and behaviours towards others they consider as non-members of their group and possibly illegitimate groups.

Studies like those of Jetten et al. (2015), Martin et al. (2017) and that by Vella et al. (2021), have shown that behaviour in a group is determined by how it boosts the self-worth or confidence of an individual and the feeling of belonging and meaning it gives them, whether in sports or in everyday activities. Thus, the individual(s) in not wanting to lose what they have such as the elitist nature of the Yoruba ethnic group are willing to do anything that aligns with the expectations and values of the group. However, it is important to point out that there are debates about whether or not the individual retains their ability to think and act for themselves, despite the influence of their group, given the level of conflict that happens and has occurred with terrorism and another example like the conflict between the Hutus and Tutsi's that resulted in genocide in Rwanda.

It is this issue referred to as “deindividuation” that throws up concern for what Gomez (2018) suggests is the manner in which politicians can use rhetoric to highlight and emphasise the supposed differences between their own “in-group and the out-group,” making it appear that the outgroup is a threat. The study by Gomez indicated that “blaming an opposing group does more harm than good.” It highlights that ascribing blame to a non-political group can affect how people perceive and behave towards the group being blamed. The reaction is not bound to be positive because it can trigger emotions which may disintegrate the situation even further.

Buttressing the dangers mentioned by Gomez, Kurten (2025) identifies four factors that could drive the use of social identity to divide and foster violence in a society. Polarised and politicised social identities is when the political actors use the social class or groups that citizens belong to as a means of distancing those not in the main group, making one group appear better than the other. Another factor is when one group feels they have lost their position or hierarchy in a political structure, then they begin to revolt, this can be seen in the narratives pushed by the Nigerian political parties All Peoples Congress (APC) and People's Democratic Party (PDP) every time one topples the other. It is a continuous debate by their supporters especially in the digital sphere. Political figures' use of violent rhetoric is the third; here in a bid to force people into aligning with their desires, political actors make threats both veiled and openly, an example being President Buhari's threat that blood would flow if he did not win the next election after he was defeated by the incumbent President Goodluck Jonathan. The last is the widespread push of misinformation about political situations and status quo on social media, given that traditional media platforms would investigate before publishing or airing the news.

Emphasising group conflict has been the pattern of politicians and parties to create distance between themselves and the opposition in the minds of the electorate. Because focusing on conflict can heighten awareness of social group differences, it can create a sense of threat to group status as played out in the Lagos Governorship elections when the focus moved from competence to ownership of Lagos and who was not entitled to contest for much less be the Governor of the state based on ethnicity—the ingroup being the Yorubas and the outgroup being the Igbos. It roused the anger of the citizens and caused fear and frustration between the groups—Yorubas and Igbos. This makes a case for Kurten who posits that “the combination of grievances and false narratives” can lead to violence, with no discrimination in terms of the victims. This makes it important to spotlight such preconditions in order to avoid and prevent further violence and anti-democratic behaviours.

At this point, SIT states that group identity and winning overcomes thoughtful deliberation (Miller and Conover, 2015; Mason, 2015, cited in Gomez, 2018), thus reducing the potential to cause a peaceful resolution to the issues. As it is, the effects of that rhetoric lingers in Lagos State 2 years after.

2.2 Political rhetoric and impact on persuasion of multi-ethnic voters during elections

Rhetoric refers to the use of words whether orally or in written form to persuade a group of people on a specific subject matter or issue. Indeed, Auerbach (2022) describes rhetoric as an art covering both speech and written content that communicates with the intention of persuading an audience to buy into the communicator's ideology or way of thinking. Reinhard (2024) has a slightly different view, pointing out that rhetoric is more than just the use of words as it can be used to “organise and maintain social order.” Given this perspective, rhetoric is then a weapon with the capacity to “build or destroy societies, create or stop change, and crucially work towards preserving civic life.”

Reinhard mentions that in politics rhetoric can be deployed by people in government or society and is a tool which has existed since the ancient Greeks and Romans. It has become a mainstay of campaigns especially political messages, where electoral candidates constantly take their time to intentionally draught arguments and phrase their ideas using words that would resonate with the electorate. As Auerbach explains it rhetoric can be both positive and negative; but good political rhetoric is factual and straightforward, presenting truthful and accurate information in a way that persuades audiences of the merits of their ideology or belief systems using both logic and emotions (Hoffman et al., 2021).

There are elements or tactics to rhetoric, which can be adjusted to determine how effective it is on the intended audiences (Blumenau and Lauderdale, 2022). Often times they circumvent the policies in place as oversight. Rhetorical elements can be used to make the opposing groups feel and look bad. There have been criticism that the use of rhetoric in political campaigns is a threat to the democratic institution as it inflames emotions and passion instead of promoting logical reasoning and deliberation. It can rouse emotions ranging from anger, happiness, pride, shame, excitement, sadness, disgust, fear, hope, to anxiety.

Examples of rhetorical elements include the use of populist rhetoric, highlighted by Atkins and Finlayson (2013), Bos et al. (2013), Hameleers et al. (2017), and Hameleers and Schmuck (2017); negative or ad hominem attacks highlighted by Lau et al. (2007); morality- and values-based appeals popularised by Jung (2020) and Nelson (2004); appeals based on expected costs and benefits of policy, highlighted by Jerit (2009) and Riker (1990); and the use of expert cues and endorsements, highlighted by Atkins and Finlayson (2013), Boudreau and MacKenzie (2014), and Dewan et al. (2014); Blumenau and Lauderdale (2022).

Khajavi and Rasti (2020) identified the use of acclaim, attack and defence as political persuasion strategies. In the use of acclaim, the political actor toots their achievements and qualifications to get public praise and support. In the use of attack, they highlight the weaknesses and incompetency of their political opponent, while for defence they make arguments against issues raised by their political opponents on their competency or qualifications.

The use of negative or adhominem language is similar to attack, as identified by Khajavi and Rasti, it is when a political party focuses on discrediting an opposing candidate. Sometimes, candidates or their supporters can use impolite or uncouth language to address the other parties and candidates. More worrisome is the use of polarising rhetoric that describes opinions that are not peaceful and can only lead to further division in the society. Here the intention is to bring groups in conflict with one another, and this affects their members as well. This can include attacks that border on questioning the legitimacy of one group to participate in the elections using factors such as religion, ethnicity and even age. It is an extreme form of rhetoric and this was used in the 2023 Governorship elections in Lagos, Nigeria.

According to Chambers (2009) and Dryzek (2010), while there is no clear-cut evidence to indicate how dangerous the use of some of these rhetorical tactics or devices are, they can still be harmful especially when they are used carelessly to make “vapid and vacuous” statements instead of helpful information. Chambers in his study mentioned that the responses of voters to political messages which are low in factual information and rich in “misinformation and disinformation” or what they termed “bombast and élan” would determine if the ability of voters to think logically or interact with information has dropped. Political rhetoric can induce powerful reactions from the recipients, often driven by the emotional.

In Nigeria a multi-ethnic society, this can have serious implications, with tensions already high due to bad governance and what some perceive to be a form of high-handedness and godfatherism in managing the country and states. As such, Wiwoloku (2022) believe in the likelihood of voters determining their choice of a candidate for any of the positions -Presidency or Governorship based on the ethnicity of the candidates, and the politicians and parties will also emphasise on this during their political campaigns. It implies that during elections, voters are more likely to respond to ethnic appeals embedded in political messages when choosing a candidate. This means that voters would focus on their social identity as in-members of a group, that is co-ethnic members when making a choice. In fact, Kulachai et al. (2023, p. 5) confirm this stating that social identity is one of the key factors influencing or determining how individuals' vote during election periods. The voters affiliation with certain political parties would determine not just who they vote for but how they react to the political rhetoric at play in the public sphere.

3 Materials and method

This study makes use of a qualitative content analysis to review both the initial posts and the responses to the controversial posts driven by ethnicity during the 2023 Governorship election period in Lagos, Nigeria.

Using the Braun and Clarke framework (Ahmed et al., 2025), initial data was collected by doing a sweep of X (formerly Twitter), and Facebook platforms for posts that specifically focused on the Governorship elections in Lagos State as this was the site of the controversial rhetoric. This did not yield posts that contained the controversial discourse that was becoming a buzz. It was then further narrowed down to specific posts that contained the parameters of “Lagosisnoman's land” and “YorubanotIgbo” especially within the context of the two major Governorship candidates for Lagos State at the time.

After examining more than 76 main posts, which turned up during the initial sweep (85% from X and 15% from Facebook), three posts were identified (two from X and one from Facebook) and served as the focus of the study based on the following parameters of inclusion which also ensured the exclusion of non-compliant posts—(a) only posts which were on the governorship elections in Lagos State; (b) the posts specifically covered the codes/subject matter “Lagosisnoman's land” and “YorubanotIgbo”; and (c) the posts had a traction of more than 20 direct responses to the content of the posts (other comments in relation to the direct responses were not considered valid). As a result n = 3. Other posts were left out of the study as they did not pull the same amount of traction as the selected posts and thus had fewer than 20 replies.

The thematic analysis was conducted based on the hashtag focus of the study and included the initial posts and only the direct comments made in response to the posts. Based on the selected posts, expanded themes were used to draw up the research questions and focused on the background of the major players in the posts, the types of rhetorical strategies and triggers used in the posts, types of responses to the strategies used and the core focus of the responses to the strategies.

The posts examined occurred between March 2023 and December of 2024 for three reasons. First, this was the peak of the messages and conversations on social media as it was about the time one of the public figures made the statement “Lagos is no man's land.” It also fell during the period of the 2023 (February 25 and March 11) elections and campaigns were still on-going. Additionally, the online debates persisted after the swearing in of the Presidential and Governorship election winners, following the fallout of the President's speech in May, which led to some major economic changes in the country felt up until December of 2024.

The sample size is small and the findings limited to the study.

The identities of those who responded were left out of the analysis due to the updated Nigeria Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc.) (Amendment) Act of 2024. The amendment has some clauses which criminalises certain posts subject to the interpretation of the law. As such, the authors do not want the research to be a point of concern for the social media users whose posts were used as in most of the messages they called out influential members of society who can make it a legal issue. The MAXQDA software was also used to analyse the data to find codes related to the main codes and sub-codes such as ethnicity/use of groups/mention of capacity/negative triggers- emotional descriptors such as hate, love, anger, etc.

4 Results and discussion

The results are discussed in two categories addressing (a) the main focus of each research question and with examples from both platforms; and (b) other information not captured by the research questions but useful in the assessment of the issue.

4.1 Background of the figures mentioned in the posts

While the posts were not selected based on the prominence of those involved in the discussion, a few names occurred based on their responses or comments on the subject matter. These include public figures—a public critic and one-time presidential aide established journalist and prominent member of the government, a one-time public office holder—all turned social media influencers. As expected, key contenders for the presidential posts in the said election also featured. Their disposition to the controversy, to posts fuelling hatred and violence was considered. These individuals were not necessarily referred to in a positive light, some of the statements were derogatory even.

“What B.O. actually meant was that Igbos residing in Lagos should not vote in elections. … Can you have a more primitive form of tribalism than that? Shame!”

The comments from respondents were based on some of the statements made by prominent Nigerians including some who neither claim to be Lagosian nor Yoruba, but who are supportive of the government.

“Respect us or leave! Don't stay in Lagos, and benefit from the leadership, infrastructure and economy Lagosians built over time, yet carry resentment towards them. You threaten violence and de-market Lagos on social media. You have options. Behave or relocate!” (@RO)

This was not helped by follow-up comments from another personality codenamed XYZ. It was quite lengthy:

“Let me open this short contribution by saying that I completely agree with the views expressed above by Pastor R O. Let us hope that those he is attempting to offer such wise counsel appreciate & accept it before it is too late. I am constrained to go further by saying that I also share the views of my dear friend, brother & colleague Omo Oba [means son of a kibg or royalty] xxx, who reflected the views and thoughts of millions of our fellow Yorubas when he expressed deep and legitimate concerns about the attempt by the Ibo community in Lagos to take over our land and claim it as theirs. This is something that they themselves would never tolerate members of any other ethnic nationality to attempt to do in the east and neither would any of us try it…”

The responses to these personalities were majorly negative as a result:

“I just remembered that Indian movie: ‘The three idiots.' To think of it that there three individuals have to an extent travelled to other places, have a little of a ‘useless education' and are still reasoning in this manner, is unbelievable.”

“You are a shame and a disgrace to the people you call children. You cannot end well.”

Some of the responses to the posts of these personalities were in visual form (memes) and very derogatory; some were curses as well:

-

Onikure was used—in English means: the person will not die well, a very painful curse.

-

Waka was also used—in English means: your mother in English, a very hurtful insult, especially when explained in the main local dialects.

The fact that specific individuals were identified as fanning the embers of bigotry during the 2023 Governorship elections and sometime afterwards aligns with the view of Koliechkin et al. (2024), that during political campaigns the influence warfare strategy is deployed to affect how the public thinks and behaves. While influence is important, it must be emphasised that the use of it has consequences, sometimes grave and beyond repair when left unchecked. The divisive, explosive and negative bent of the comments on social media is a fall-out of comments by individuals who should do better.

The background of the individuals called out based on their comments and statements on social media is cause for concern. In the mix was a public critic, a one-time presidential aide, established journalist and prominent member of the government, a one-time public office holder, all individuals who should know and do better, given their oath to provide information without bias or the intention to cause harm, and protect the unity of the country. They are aware or must have feigned ignorance of the consequences of their statements given that they have people who respect their every word and would act in accordance with whatever they say. This was evident in the responses of followers who agreed with their rhetorics and traded insults with dissenting parties online.

4.2 Divisive rhetorical strategies used in the posts

The authors identified the use of five rhetorical strategies, which are not necessarily negative but were deployed in such a way as to trigger divisive and negativity across both the X and Facebook posts. They include—ethnic-centricity or ethnic nationalism, scapegoating or blaming of the “victim” or recipient as the cause of the issue, use of history to drive the arguments of the political actors, use of fear or threat appeals and emotional arguments. There were some neutral comments, but no positive comments or responses. Sometimes, the comments were snide or sarcastic to make the argument.

Ethnic-Centricity was one of the main rhetorical strategies used in the posts and conversations around it. The identified posts in this category played on the sense of identity of the individuals, making it a form of in- vs. out-group situation, an idea that the theory of social identity thrives on. The posts/responses essentially framed Lagos as Yoruba land and nothing else.

Examples of such statements include:

“Let 2023 be the last time of Igbo interference in Lagos politics.”

“Lagos is fundamentally, principally, originally and organically a Yoruba land. The voters of the governorship election confirmed the facts. The matter of Lagos is finally settled. Intruders, beware!”

“Yoruba interests must be protected from interference.”

Also tied to the ethnic-centricity was a form of gatekeeping using culture—the respondents making culture the qualification to get into governance.

“Only Yorubas should rule Lagos. Period.”

Ethno-centricity is not bad in itself, as traditionally it was used to appeal to the shared sense of identity and heritage of a people, to spur them to act in unity to achieve a specific goal—usually positive, and example would be the one planet, no Plan B mantra of the United Nations and climate change activists. However, over time the persuasive tactic has transitioned into tools of division in the hands of influential men (majorly) who should be more responsible with the soft power at their disposal. This is important to note as Kurten (2025) states that using social identity to create a distinction between candidates in the minds of the electorate is a sure way to divide as opposed to uniting citizens and this can fan the embers of violence, which does not discriminate in terms of its victims.

Blaming others for the situation and their actions was another major strategy embedded in the responses. Social media users scapegoated the tribe on the receiving end of their “diatribe.” They assigned the blame of the situation and negative discourse to the Igbos, just to achieve their political aim. Examples of such statements are:

“IGBO are enablers of the IPOB [Independent People of Biafra] terrorists…they will know what life is like under terrorists.”

Some of the comments also ascribed blame to other parties like the Government and B.O as an extension of same, as being connected to the controversy.

“Calling on the FG to arrest those involved is a waste of time because it's their paid agents.”

“It's obvious B.O is the one who sponsored the terrorists on the Ndigbo in Lagos state.”

The social media users also anchored some of their arguments on history, both confirming and others using it to dispute their arguments. Some even posted the comments of respected figures in the history of Lagos State. References were also made to other similar cases outside the country.

“At the same time we shall ensure that every public servant in this state is adequately rewarded for his labour. Merit will be recognised regardless of language, colour or creed.—Lateef Jakande, Former Governor of Lagos 1979–1983.”

“The issue here is interesting: Who exactly are considered the indigenous people of Lagos?

is it the Benin people or Aworis indigene, who are often mixed with other tribes, of which there's non-existent of pure breeds living one. Could it be the British, or Portuguese? Because most individuals in Lagos migrated from other states. It's either they address it as a tribal matter, encompassing all ‘Yorubas,' which could potentially lead to a civil war and the separation of everyone. That's why we emphasize the importance of voting for people in all areas, not just for ‘presidential' and ‘gubernatorial' positions. It's crucial to know who creates our laws.”

“This is the same way Nigeria treated Ghana, but today, Ghana is better than Nigeria. We welcome their demand, but let's do it legally. You can't wake up overnight to eject people from their properties just to occupy them, it's the height of irresponsibility and cowardice.”

Fear appeal was another rhetorical strategy engaged by the social media netizens who responded. Words like “beware, intruders” were randomly and freely used by a few of them in their statements.

“Lagosians [sic] should be ready for ‘Monday sit at home' if they vote for Igbo as their governor.”

“Let's f***ing go! Civil war the sequel!”

There was a lot of out-group hostility (Aghabi et al., 2017) magnified across the posts on the two platforms. This affected the voters turn-out across centres in Lagos state and some other states as well, with many scared about the possibilities of being attacked if they voted against the in-group (Yorubas) as opposed to their choice (Premium Times, 2023, May 3). The report stated that only four states (all Northern) had more than 40% voter turn-out. This spells doom for efforts to onboard more electorate to participate in the democratic process through their votes, due to fear of reprisals.

The responders also tried to provoke emotional responses (possibly unintentionally) from others especially the Igbos reading their comments. There was a heavy dose of hate, bigotry, and xenophobic words.

Gomez (2018) mentioned that rhetoric can be used by individuals and political representatives to highlight and emphasise the supposed differences between their own “in-group and the out-group,” making it appear that the outgroup is a threat. With people still bearing scars from previous incidences over time, the reaction becomes explosive. The original posts by key influencers and majority of the responses from the followers or viewers of the posts were centred on how the Igbos (representing the out-group). were a threat to the Yorubas (representing the in-group). In fact, most of the comments are interspersed with a “we” vs. “them” outlook. It reflects what Gomez describes as the effect of group identity, where that identity and the desire to win or shine outweighs and overrides thoughtful consideration of others.

Gomez's view lends credence to Kurten's warning on the need to avoid such strategies which can cause supporters to make threats online and this can spill over into physical violence. There were videos online showing how this played out in Igbo dominated areas; with a few markets owned by Igbos combusting and burning in the thick of the conflict.

It indicated that the political strategies chosen by the political actors served as triggers that further damaged the trust between ethnic groups in Lagos state, which was delicate even before the elections.

4.3 Triggers embedded in the posts

Reinhard (2024) stated that rhetoric was a weapon, which if pulled was capable of “building or destroying societies, creating or stopping change, and preserving the stability of society.” The social media posts contained a number of triggering words/phrases embedded in their responses and posts. They focused a lot on ethnic identity (using the in-team vs. out-team) to drive their message and agenda, they talked a lot about the Igbos as interferers and busybodies, in some instances they were threatened with physical attacks, and then threatened with disenfranchisement.

Examples of statements with these triggers are:

“IGBO are enablers of the IPOB [Independent People of Biafra] terrorists…they will know what life is like under terrorists.”

The above statement is particularly triggering because in the last few years, there has been the recurring issue in some of the Southeast with member of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) restricting movement on specific days in the south east; and the group has been declared by the Nigerian government as a terrorist group, based on their activities and allegations of human rights violation.

“Was an Igbo person on the ballot? Trying to vote? Exercising right?”

“Redefine employment to exclude Igbos from all Yoruba states.”

A few of the Igbos responded, addressing the issue of disenfranchisement and just the general hate statements against them:

“Only if you have common sense, you will make a reasonable comment! Because, a Yoruba man named Abiola just won a sit in Abia State, the joy of Ndigbo over his victory was overwhelming! Even though 90% of our people sat at home on Saturday! They didn't ask him to go to Lagos and vote! Racial [sic] and hatred is you guys problem!”

“Constitution allows Nigerians to vote anywhere.”

“Igbos buy land, pay taxes. They are not intruders.”

“Yorubas in Bayelsa voted freely, but Igbos in Lagos were brutalised.”

“In Abia, a Yoruba man won and was celebrated. Nigeria must cleanse itself of Bigots.”

A few responses indicated that they felt that relocating or divesting their investments to other places in the Southeast and supporting the call for their own country was the way to go.

“SS–SE should leave Lagos and invest at home.”

“The only meeting where everybody is happy is ‘hate against the Igbos and maiming of the Igbos'. Use this energy to push for Igbos to leave Nigeria so that you and Yoruba people will build a better Nigeria void of Igbo interference.”

“Igbos are you people reading this epistle slowly… they've made it clear. You are no longer needed in SW. Start taking your investments back to the east before it[sic] too late…sell that land and rebuy in the east. Never ever take this warning for granted.”

4.4 Types of responses to the rhetorical strategies used

The embedded triggers worked. They generated heated responses. The responses to the original posts and the subject-matter in the original posts came in two categories—as logical and counter-arguments, using historical analysis and facts to back their claims on both sides of the divide, that is Lagos as no man's land and Lagos as Yorubaland; and emotional expressions with examples of disappointment, anger, disgust, forms of hate and expressions of jealousy. Generally, a lot of the responses had negative sentiments; with hardly any positive centred or neutral responses. There were also defiant and insult-laden statements from a few on the receiving end of the posts.

“This is a[sic] pure bigotry.”

“…fools in old body”

Some other emotionally charged responses included:

“God will punish you and your generation…b@stard!”

“Untimely de@th will befall you and your children.”

“Who are you than an old foool? What can you do? Both now and in 2027, what exactly can you do? Drive Nigerians out of Lagos or what? Why are you overrating yourself like you're important in anyway? People can do business and pay tax in Lagos but can't be part of governance? Foool.”

A few neutral comments simply gave responses not laced with insults or threats but expressing how they felt:

“What B.O actually meant was that Igbos residing in Lagos should not vote in elections. He calls them casting their votes as interference in Lagos politics. Can you have a more primitive form of tribalism than that? Shame!”

Some were expressions of disappointment at someone they respected—in this instance B.O, one of the personalities mentioned around the controversy:

“What kind of foolish tweet is this egbon?”

“Very unbecoming of you, sir. What would Dele Giwa have thought of you?”

Some had hints of violent threats, promising some form of reaction:

“they will react on this one…[a form of sarcasm]na [it is] when men begin to mount[gather] and challenge this animal[insult] now, na that time una go won act on it.”

4.5 Focus of discourse

The direction or focus of the responses was another factor assessed. Four items were considered—capacity, tribal sentiments, description of situation and proffering of solutions to the controversy.

In analysing the situation, a number of the social media users simply described the issue without any other emotional components.

“When you stayed in a place for 5–10 years you entitled to the rights and privileges…what is the meaning of Lagos is a Yoruba Land…? Black racism”

“This is insane, these people should not start what they cannot finish. Imagine if all other states embrace this concept. Everyone will become aliens in their own country.”

“History has shown us the consequences of allowing hatred and bigotry to fester, as seen in Rwanda. What began with inflammatory rhetoric led to devastating outcomes. We must learn from these lessons and act decisively.”

“In a sane society, this journalist would have resigned already & faced consequences for perpetuating igbophobia.”

“Obvious we've all been living in pretence in this country. Tribalism has eaten deep in our veins. May God help us.”

“This is hate speech, inciting violence.”

“I don't blame them. I blame bad politics, bad politicians and bad governance of decades that chose to develop some regions and leave some out for selfish reasons. This is the result.”

Although comments with solutions were not many, a few of those comments slipped past the emotionally charged responses:

“ …Instead, let us extend our hands in a gesture of camaraderie, seeking to bridge the chasm that has long stood between us. To any well-meaning Nigerian, the path to a better tomorrow lies not in fracturing our nation, but in unearthing the common ground that forms the bedrock of our shared identity. We must resist the siren call of division and conflict, choosing instead to stand shoulder to shoulder, united in our quest for a brighter future.”

“I call on the Nigerian government and relevant authorities to take immediate and strong action against those inciting such hatred and division. It is imperative to investigate, arrest, and prosecute individuals promoting ethnic discrimination and violence.”

“You're a journalist and you should know better. Stop fanning violence. “ – this in response to B.O's post.

There were also some comments which were representative of tribal sentiments

“That serve the dumb Igbos mingling with APC right.”

“Ibos contributed immensely to the development of Lagos. They are the should and spirit of real buying and selling in Lagos State. But they cross their boundary when they think they can control …they can put a king on the throne in that state because they aren't the sons of the soil.”

“Don't joke with Ibos. Yoruba have to deal with Ibos in the ‘language they understand.' Ibos, an extreme danger to Yorubaland and existence.”

There was not much talk around the capacity of the candidates before and after the elections. A few responses did make indirect references to the ability of the candidates as a possible criteria for the votes.

“Merit will be recognised regardless of language, colour or creed.”

“It is a national party with good plans and intention to rid Nigeria of backwardness.”

There were also a few responses from Yorubas speaking up against what appeared to be the “Igbo bashing.” However, they were few and miniscule compared to the other responses supporting the “anti-Igbo” and being Lagos citizens issue.

“Seriously, if we must protect Lagos like you said then it should be in a way that won't cause hatred. I have loved my life with Ibos and even have them as tenants. We have good people among them,…the same way we have tribalistic people amongst the Yorubas. Don't be biassed…not Ibo alone.”

“Yorubas kindly treat your Igbo brothers the way you want your fellow Yoruba brothers be treated in Igbo land, simple! All this people inciting you against each other, they won't be there when you need them even if they are Yoruba like you, it is that your Igbo brother next door.”

“It's sad that Nigeria has gotten to this stage…I can't put together my feelings in word. I'm super sad for my country. Ndi Igbo…I can assure you this is not the mindset of majority of the Yorubas. This is just some few bad heads (APC majorly) amongst us. We love you so much.”

The triggers and negative focus of the reactionary posts on the social media platforms emphasise the importance of Auerbach's (2022) view that although political rhetoric started as a means of persuasion towards an ideology, recent studies and news items show that the type of rhetoric now present in the political sphere is merely driving a wedge between the electorate, increasing polarisation and exacerbating tension. The Lagos tension has not eased—with an Oba in Lagos raising objections when an Igbo artist used the terminology “owambe” mainly ascribed to Yoruba people as the theme for his art exhibition. Comments online had begun stating that the said event would not hold, stating that other tribes wanted to claim what was not theirs. As the authors have highlighted, the division which sprung from the rhetorics around the “Lagosisnomansland” issue continues to spill into other issues even today.

4.6 Thematic analysis

A transparent NLP pipeline was used for the n = 3. The text was tokenized into individual words, and all urls, identifying markers, emojis and punctuation marks were left out to focus on just the linguistic content. Link words like prepositions and adverbs were removed since they do not contribute to the thematic meaning. The remaining tokens were stripped of grammatical forms of the same word and reduced to the meaningful concepts rather than inconsequential variations in the social media language use, with particular focus on ethnic terms, group identifiers, and capacity-related language.

Word cloud (Figure 1) and Frequency distribution (Table 1) were generated under this section.

Table 1

| Words | Freq | Freq % |

|---|---|---|

| Lagos | 188 | 1.83 |

| Yoruba | 128 | 1.25 |

| Not | 109 | 1.06 |

| People | 93 | 0.91 |

| Igbo | 83 | 0.81 |

| Igbos | 79 | 0.77 |

| Nigeria | 66 | 0.64 |

| Land | 65 | 0.63 |

| Man | 59 | 0.58 |

| State | 59 | 0.58 |

| Election | 56 | 0.55 |

| Go | 56 | 0.55 |

| Ethnic | 31 | 0.30 |

| Hate | 29 | 0.28 |

| Nigerian | 29 | 0.28 |

| Bayo | 27 | 0.26 |

| APC | 26 | 0.25 |

| Never | 26 | 0.25 |

| Yorubas | 26 | 0.25 |

| Country | 25 | 0.24 |

| Politic | 25 | 0.24 |

| Intruder | 24 | 0.23 |

| Governorship | 23 | 0.22 |

| Tribe | 23 | 0.22 |

Frequency count of ethnic-centric and divisive words.

Figure 1

Word cloud for posts across Twitter and Facebook (based on social media data, 2025).

Using MaxQda, a word cloud (Figure 1) was generated to highlight the most recurring or major descriptive words from the responses to identify if elements of the main codes “Lagosisnoman's land” and “YorubanotIgbo” and sub-codes such as ethnicity/use of groups/mention of capacity/negative triggers- emotional descriptors such as hate, love, anger were present.

Considering that the Governorship elections were meant to focus on electing a new Governor who would be the main driver or socio-economic development of the state, two things emerged from the word cloud which were of concern. There was a conspicuous absence of discussion centred around the capacity of the candidates and so the only reference to governance was the word development.

The second issue of concern was the level of diatribe that permeated the conversations responding to the original posts. While the original posts may have triggered certain feelings in individuals, the direction of the conversation indicated the use of negativity or negative adhominem—one of the rhetorical strategies earlier identified. Words like intruders, tribalism, bigotry, hatred, protest had pride of place on the word cloud.

4.7 Frequency of ethnic-centric words and divisive words

A frequency distribution of the most recurring words especially in order of ranking presented an overview of the following words. As mentioned earlier, words not relevant to the study like pronouns, adverbs, prepositions have been excluded from the frequency table. However, the words left all fall within the top 13 in terms of ranking out of 486.

The frequency table shows the core focus of the posts and responses across the two platforms and aligns with the word cloud as well. Ethnicity was a major component of the word frequency showing up in the top 20 words—Igbo, Igbos, ethnic and Yorubas.

Asides the ethnic-centred words, there were some words of concern which made it into the top 20—words like go, hate, and intruder, which emphasised the truly divergent or divisive range of responses to the different posts.

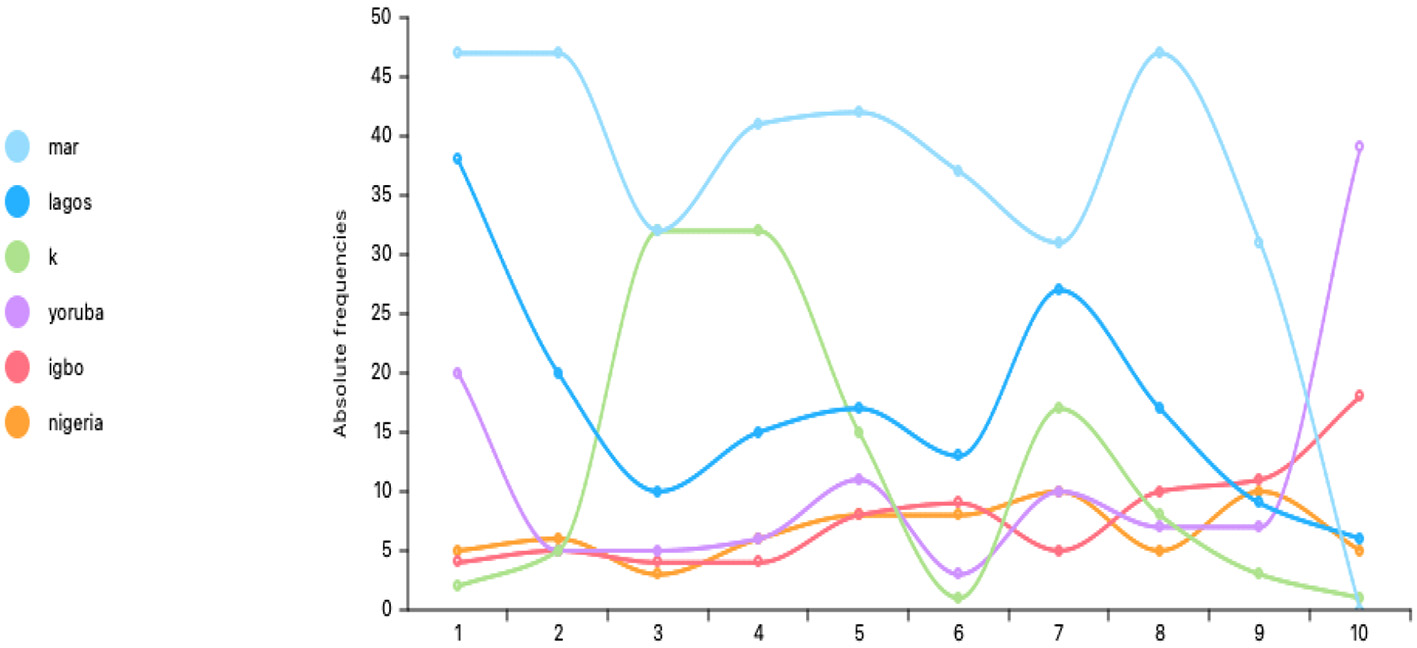

A word trend (Figure 2) was also generated for the ethnic words represented in the posts across both platforms.

Figure 2

Word trend for ethnic words used across the Twitter and Facebook posts (based on extracted social media data, 2025).

The resulting word cloud and frequency counts support earlier arguments by revealing patterns of in-group and out-group rhetoric consistent with the tenets of the Social Identity Theory that proponents or avid supporters of the in-group and out-group theory would use words that establish differences between groups. A lot of the words used in the posts and responses were identity driven, whether by ethnicity or even political party. This indicates that there is a high level of social categorisation that goes into how the electorate processed a lot of the information circulating during the Lagos Governorship elections. This indicated a high level of in-group (Yoruba) vs. out-group (Igbo) dynamics rather than neutral discourse during that period.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

The 2023 Lagos Governorship Elections demonstrated the deliberate use of hate speech and ethnic language to exacerbate tensions and galvanise voter emotion along identity lines. It depicted the prevalence of a high level of social identity politics, which flowed into the rhetorics during that period. Igbo communities were specifically targeted by political players and their supporters, who used ethnic affinities as a weapon to create exclusionary narratives that portrayed political engagement as a challenge to indigenous dominance. The study found that ethnic-centricity was one of the main rhetorical strategies used in the posts and conversations around it. The major ideas around the posts in this category was that they played on the sense of identity of the individuals, making it a form of in- vs. out-group situation.

The study indicated that social media posts contained a number of triggering words/phrases embedded in their responses and posts. They focused a lot on ethnic identity (using the in-team vs. out-team) to drive their message and agenda, they talked a lot about the Igbos as interferers and busybodies, in some instances they were threatened, and they were threatened with disenfranchisement. Another issue of concern was the level of bitter and abusive language that permeated the conversations responding to the original posts. While the original posts may have triggered certain feelings in individuals, the direction of the conversation indicated the use of negativity or negative adhominem—one of the rhetorical strategies earlier identified. Ethnicity was a major component of the word frequency showing up in the top 20 words—Igbo, Igbos, ethnic, and Yorubas. Asides the ethnic-centred words, there were some words of concern which made it into the top 20—words like go, hate, and intruder, which emphasised the truly divergent or divisive range of responses to the different posts.

The study concludes that the situation needs to be addressed; a number of authors reviewed say as much, decrying the possibilities that the situation could spiral into, especially with recent news headlines indicating that beyond the elections and swearing-in of winners of the 2023 elections, the issue of social identity, while not a negative in itself, but as emphasised and weaponised by political actors in 2023 continues to bring division. The approach of the actors in using this strategy is dangerous in the long-term as a divided polity is unable to build meaningful democratic institutions because the focus becomes identity as a benchmark for who is worthy or now worthy of contesting and being elected as opposed to capacity and ability to create sustainable and positive change.

Moreover, the fallouts of the divisive diatribe interspersed with violent (veiled and unveiled threats) was seen in the low turn-out at the election booths according to a Premium Times report of May 3, 2023. Political rhetorics are meant to persuade and inspire emotions around ideologies and belief systems focused on democratic principles and not inspire fear and negativity.

With the situation as is, there is need to integrate media and information literacy into political education and campaign for both political actors and the electorate, as this is needed to encourage all parties to treat the campaigns not as a battle but an opportunity to exchange ideas and persuade people without dovetailing into divisive diatribes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Caleb University, Ikorodu Imota Ethics Committee. There was no need for written informed consent to participate in this study from the participants' OR participants legal guardian/next of kin, as the names of those who commented on the platforms were intentionally left out due to the sensitive nature of some of the things written. Ethical approval was secured for the research. Additionally, the identities of the people who posted and commented were left out for confidentiality sake.

Author contributions

IA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BO: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BA: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

BA was employed by Telvida International Systems Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adegbami A. Uche C. I. N. (2015). Ethnicity and ethnic politics: an impediment to political development in Nigeria. Public Adm. Res.4, 59–67. doi: 10.5539/par.v4n1p59

2

Aghabi L. Bondokji N. Osborne A. Wilkinson K. (2017). Social Identity and Radicalisation: A Review of Key Concepts. Amman: West Asia-North Africa (WANA) Institute.

3

Ahmed S. K. Mohammed R. A. Nashwan A. J. Ibrahim R. H. Abdalla A. Q. Ameen B. M. M. et al . (2025). Using thematic analysis in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health6:100198. doi: 10.1016/j.glmedi.2025.100198

4

Amnesty International (2017). Politics of Demonisation Breeding Division and Fear. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2017/02/amnesty-international-annual-report-201617/ (Accessed June 15, 2025).

5

Asimakopoulos G. Antonopoulou H. Giotopoulos K. Halkiopoulos C. (2025). Impact of information and communication technologies on democratic processes and citizen participation. Societies15:40. doi: 10.3390/soc15020040

6

Atkins J. Finlayson A. (2013). ‘... A 40-year-old black man made the point to me': everyday knowledge and the performance of leadership in contemporary British politics. Polit. Stud.61, 161–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00953.x

7

Auerbach M. P. (2022). Political Rhetoric: Overview. Ipswich, MA: EBSCO Knowledge Advantage. Available online at: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/communication-and-mass-media/political-rhetoric-overview (Accessed June 24, 2025).

8

BBC (2017, February 22). Divisive political rhetoric a danger to the world, Amnesty says. BBC. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-39048293 (Accessed June 24, 2025).

9

Beacham A. Hafner-Burton E. M. Schneider C. J. (2024). The weaponization of information technologies and democratic resilience. IGCC Working Paper No 9, 3–51. Available online at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6f24q81x (Accessed July 05, 2025).

10

Blumenau J. Lauderdale B. E. (2022). The variable persuasiveness of political rhetoric. Am. J. Pol. Sci.68, 255–270. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12703

11

Bos L. van der Brug W. de Vreese C. (2013). An experimental test of the impact of style and rhetoric on the perception of right-wing populist and mainstream party leaders. Acta Polit.48, 192–208. doi: 10.1057/ap.2012.27

12

Boudreau C. MacKenzie S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. Am. J. Polit. Sci.58, 48–62. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12054

13

Chambers S. (2009). Rhetoric and the public sphere: has deliberative democracy abandoned mass democracy?Polit. Theory37, 323–350. doi: 10.1177/0090591709332336

14

Davis A. (2023). Political Communication: An Introduction for Crisis Times. John Wiley and Sons.

15

Dewan T. Macartan H. Daniel R. (2014). The elements of political persuasion: content, charisma and cue. Econ. J. 124, F257–F292. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12112

16

Dryzek J. S. (2010). Rhetoric in democracy: a systemic appreciation. Polit. Theory38, 319–339. doi: 10.1177/0090591709359596

17

European Commission (2021). Study on the Impact of New Technologies on Free and Fair Elections: A Literature Review. Available online at: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-12/Annex%20I_LiteratureReview_20210319_clean_dsj_v3.0_a.pdf (Accessed July 05, 2025).

18

Forest J. J. F. (2021). Political warfare and propaganda. J. Adv. Mil. Stud.12, 13–22. doi: 10.21140/mcuj.20211201001

19

Gomez K. S. (2018). Divide and conquer: examining the effects of conflict rhetoric on political support (Ph.D. thesis/dissertation). University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, United States. Available online at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5017 (Accessed June 20, 2025).

20

Hameleers M. Bos L. de Vreese C. (2017). Framing blame: toward a better understanding of the effects of populist communication on populist party prefernces. J. Elections Public Opin. Part.28, 380–398. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2017.1407326

21

Hameleers M. Schmuck D. (2017). It's us against them: a comparative experiment on the effects of populist messages communicated via social media. Inform. Commun. Soc.20, 1425–1444. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328523

22

Hassan I. (2023). Dissemination of disinformation on political and electoral processes in Nigeria: an exploratory study. Cogent Arts Humanit.10:2216983. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2023.2216983

23

Hoffman D. C. Lewis T. Waisanen D. (2021). The language of political genres: inaugural and state speeches of New York City Mayors and US Presidents. Proc. N. Y. State Commun. Assoc.2017:9.

24

Jerit J. (2009). How predictive appeals affect policy opinions. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 53. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25548126 (Accessed May 15, 2025).

25

Jetten J. Branscombe N. R. Haslam S. A. Haslam C. Cruwys T. Jones J. M. et al . (2015). Having a lot of a good things: multiple important group memberships as a source of self-esteem. PLoS ONE10:e0124609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124609

26

Jung J.-H. (2020). The mobilizing effect of parties' moral rhetoric. Am. J. Polit. Sci.64, 341–355. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12476

27

Khajavi Y. Rasti A. (2020). A discourse analytic investigation into politicians' use of rhetorical and persuasive strategies: the case of US election speeches. Cogent Arts Humanit.7:1740051. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1740051

28

Koliechkin V. Strunhar A. Hnatyuk M. Diakiv V. Shmilyk I. (2024) Verbal warfare: assessing how contemporary political rhetoric shapes societal dynamics. Lib. Pro. Int.44, 18408–18419. doi: 10.61707/ha5rpx23

29

Kulachai W. Lerdtomornsakul U. Homyamyen P. (2023) Factors influencing voting decision: a comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. 12:469 doi: 10.3390/socsci12090469

30

Kurten M. (2025, January 9). Why we fight for fractured truths – how misinformation fuels political violence in democracies. Mediawell. Available online at: https://mediawell.ssrc.org/research-reviews/why-we-fight-for-fractured-truths-how-misinformation-fuels-political-violence-in-democracies/ (Accessed June 24, 2025).

31

Lau R. R. Sigelman L. Rovner I. B. (2007). The effects of negative political campaigns: a meta-analytic reassessment. J. Polit.69, 1176–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00618.x

32

Lee T. (2019). The global rise of “fake News” and the threat to democratic elections in the USA. Public Adm. Policy22, 15–24. doi: 10.1108/PAP-04-2019-0008

33

Martin L. J. Balderson D. Hawkins M. K. Bruner M. W. (2017): The influence of social identity on self-worth, commitment, effort in school based youth sport. J. Sports Sci. 36, 326–332. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1306091

34

Mason L. (2015). I disrespectfully agree: the differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci.59, 128–145.

35

Miller P. R. Conover P. J. (2015). Red and blue states of mind partisan hostility and voting in the United States. Polit. Res. Q.68, 225–239.

36

Nelson T. E. (2004). Policy goals, public rhetoric, and political attitudes. J. Polit. 66. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00165.x

37

Oji O. R. Okeke V. Vincent O. S. Orisakwe O. S. Olemeforo E. I. (2024). Ethnic politics and democratic governance in Nigeria (2015–2023). Social Science Research Network (SSRN) [Preprint]. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4801981

38

Olaniran B. Williams I. (2020). “Social media effects: hijacking democracy and civility in civic engagement,” in Platforms, Protests and the Challenge of Networked Democracy, eds. JonesJ. and TriceM. (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 77–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36525-7_5

39

Premium Times (2023, May 3). Data story: details of Nigerians voting pattern in 2023 governorship elections. Premium Times. Available online at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/597121-data-story-details-of-nigerians-voting-pattern-in-2023-governorship-elections.html?tztc=1 (Accessed June 28, 2025).

40

Reinhard E. (2024). The rhetorical politics of political persuasion. Rutgers Camden News. Available online at: https://camden.rutgers.edu/news/rhetorical-politics-political-persuasion (Accessed June 9, 2025).

41

Riker W. H. (1990). “Heresthetic and rhetoric in the spatial model,” in Advances in the Spatial Theory of Voting, eds. EnelowJ. M. and HinichM. J. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press).

42