- Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, Malaysia

This article proposes the Political System Index (PSI), a non-normative framework for analysing political systems through Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory. Unlike conventional democracy indices that rely on normative benchmarks, the PSI views politics as an autopoietic communication system organised around the binary code government/opposition. It identifies six analytical components—code, function, medium, programme, structural coupling, and irritation—each operationalised through empirical proxies such as legislative output, implementation rates, and responsiveness to disturbances. By employing second-order observation, the PSI examines how political systems reproduce communication, process complexity, and adapt to environmental irritations without prescriptive judgements. This approach enables equivalence-based comparisons across diverse regimes, including non-democratic and hybrid systems, revealing functional coherence beyond liberal ideals. Ultimately, the PSI offers a theoretically grounded and empirically applicable instrument for observing how political communication sustains order, adaptation, and continuity within functionally differentiated societies.

Introduction

Niklas Luhmann (1927–1998) stands as one of the most intricate and influential theorists in modern sociology. His social systems theory reconceptualises society not as a network of individuals or institutions but as a constellation of functionally differentiated subsystems—such as politics, law, the economy, and the media. Each subsystem sustains itself autonomously through recursive communication, guided by binary codes and operational closure, which preserve its independence from external interference. From this self-referential standpoint, Luhmann articulates a non-normative vision of society that emphasises its continuous, emergent operations. This shift from actor-centred models to communication as the foundation of social reality fundamentally disrupts traditional understandings of organisation, agency, and social order.

Luhmann’s non-normative approach particularly challenges conventional political metrics, which often embed assumptions about ideal outcomes. Indices such as Polity IV (Marshall et al., 2019; Freedom House, 2025), and the Varieties of Democracy project (Lührmann et al., 2020; V-Dem Institute, 2025) evaluate systems through lenses of democracy, civil liberties, or institutional performance, presupposing alignment with liberal democratic ideals. Yet, from a systems-theoretical perspective, these tools obscure the political system’s core as an autopoietic network centred on the binary code of government/opposition, whose primary role lies in producing collectively binding decisions that manage societal complexity.

To address this gap, this article introduces the Political System Index (PSI), a non-normative observational framework that traces the political system’s self-reproduction as a communication network. By prioritising second-order observation—observing how observers within the system, such as government/opposition communications, deal with problems of the system and its environment—the PSI focuses on six interconnected components: code, function, medium, programme, structural coupling, and irritation. These are translated into empirical proxies, such as legislative success rates, implementation rates, and responses to disturbances, enabling equivalence-based comparative analysis across systems without normative judgements. Drawing on scholars such as King and Thornhill (2003), Opitz (2017), and Baxter (2013), the PSI complements existing indices by revealing internal systemic logic rather than external ideals.

The article follows a systematic structure in which the next section explores the theoretical foundations of political systems within Luhmann’s systems theory paradigm and justifies this choice over alternative systemic approaches. The third section critically analyses existing normative indices in political science, weighing their respective advantages and limitations. The fourth section outlines the methodology used in developing the Political System Index (PSI) and includes visual representations to enhance clarity. The fifth section discusses practical applications of the index, and the final section considers its potential challenges, limitations, and prospects for future research. Together, these sections establish a coherent progression from foundational concepts to methodological innovation, empirical application, and critical reflection.

Theoretical framework: the political system as autopoiesis

Building directly on Luhmann’s reconceptualisation of society as functionally differentiated subsystems, this section elaborates the political system’s distinct operations while justifying the choice of his theory over alternative systemic approaches. Luhmann’s framework is selected for its radical emphasis on communication as the elemental unit of social systems, enabling a strictly non-normative analysis that avoids anthropocentric or teleological assumptions inherent in other theories (Borch, 2011; King and Thornhill, 2003).

Unlike Parsons’s, 1951 structural-functionalism, which posits normative integration through the AGIL schema (adaptation, goal attainment, integration, latency) as essential for system equilibrium, Luhmann’s autopoiesis prioritises operational closure and binary coding, treating systems as self-reproducing through their operations without presupposing societal harmony or progressive goals. Similarly, Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba’s civic culture model embeds democratic norms by linking political stability to attitudinal orientations such as trust and participation (Almond and Verba, 1963), whereas Luhmann observes politics solely through government/opposition communications, irrespective of cultural or normative content. This decentring of actors and ideals makes Luhmann’s approach uniquely suited for the PSI, as it facilitates second-order observation—observing how observers within the system (for example, government/opposition communications observing other such communications) deal with problems of the system and its environment—without imposing external benchmarks (Moeller, 2011).

To enhance accessibility, key terms from Luhmann’s theory are defined inline upon first use and summarised in Table 1 for reference. In modern society, subsystems process overwhelming complexity by relying on binary codes that filter relevant communications: the economy distinguishes payment/non-payment, law separates legal/illegal, science divides true/false, and politics operates through government/opposition (Luhmann, 2012). This coding ensures operational closure—where systems rely on internal operations (communications) insulated from direct environmental inputs—while allowing cognitive openness to external influences, meaning systems can perceive and adapt to perturbations without losing autonomy (Luhmann, 2013; Stichweh, 1990). Such functional differentiation prevents any subsystem from dominating, fostering interdependence without hierarchy.

Within this model, the political system’s code of government/opposition selectively identifies communications that structure authority and contestation, such as those producing, distributing, or challenging decisions with binding force. This code underpins the system’s core function: generating collectively binding decisions that resolve societal undecidability and stabilise expectations in an uncertain world (Luhmann, 1990a,b; Thornhill, 2007). Far from pursuing normative goals such as equity or representation, these decisions enable coordination amid contingency, averting systemic paralysis (Borch, 2011). For instance, policies or laws serve this role by transforming ambiguity into enforceable norms.

Supporting these operations is the medium of power, a symbolically generalised communication form that loosely couples communications across contexts, much as money facilitates economic exchanges. Power conveys authority contingently and revocably, relying on the latent threat of force or violence—not as direct coercion but as a stabilising potential that makes compliance more probable (Luhmann, 1979; Thornhill, 2007). For example, the implicit possibility of legal sanctions or enforcement underpins power’s ability to connect decisions across societal spheres, ensuring flexibility in late-modern dynamics where coercion alone is insufficient (Schoeneborn, 2011; Baxter, 2013).

The programme complements this by providing contingent structures—such as constitutions, electoral rules, or party systems—that guide how government/opposition distinctions are applied in practice. Unlike fixed hierarchies, programmes adapt through internal debates or environmental shifts, allowing recalibration while safeguarding autopoietic continuity (Luhmann, 1990a,b; Opitz, 2024). This mutability highlights the system’s self-referential evolution, where rules are both enabling and revisable. Notably, while government/opposition is the primary code, it operationalises broader power dynamics, which Luhmann (1990a,b) frames as a foundational distinction in certain contexts, ensuring the PSI’s focus aligns with tangible political communications.

Although closed operationally, the political system engages its environment through irritation and structural coupling. Irritation occurs when external disturbances—such as crises or protests—are reconstructed internally as political communications, prompting responses without direct causation (Luhmann, 1986; Stenner, 2017). This selective processing maintains responsiveness while preserving boundaries. Structural coupling forms stable interconnections with other subsystems, such as politics and law via legislative-judicial interplay, or politics and media through policy dissemination (Luhmann, 1995, 2000; Seidl and Schoeneborn, 2010). These linkages facilitate mutual adaptation, ensuring that the political system evolves in tandem with societal differentiation.

Collectively, these components—code, function, medium, programme, structural coupling, and irritation—illuminate the political system as a self-sustaining communication network that reduces complexity through government/opposition dynamics. The PSI leverages this framework by mapping these elements to observable indicators, such as decision outputs and inter-system references, to facilitate empirical second-order observation (Opitz, 2017). This theoretical lens not only grounds the index but also sets the stage for critiquing how existing metrics overlook such internal operations.

Critique of existing political indices

Having established the political system as an autopoietic communication network within Luhmann’s framework, alongside contrasts with alternative systemic theories, it becomes evident why conventional indices have limitations despite their notable strengths. This section provides a balanced evaluation, first acknowledging the advantages of existing tools before critiquing their normative biases and identifying a theoretical gap grounded in empirical evidence.

Contemporary indices such as the Polity IV Project (Marshall et al., 2019), Freedom House’s Freedom in the World reports (Freedom House, 2025), and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Lührmann et al., 2020; V-Dem Institute, 2025) have significantly advanced comparative politics by offering standardised, data-rich frameworks that enable global rankings, trend analyses, and correlations with socioeconomic outcomes. For instance, these metrics have tracked waves of democratisation (Huntington, 1991), informed policy interventions in international organisations such as the United Nations, and facilitated empirical studies linking regime types to economic growth or conflict resolution (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Przeworski et al., 2000). Proponents highlight their utility in advocacy and accountability, aligning with human rights frameworks to promote liberal democratic ideals (Diamond, 1999; Lindberg, 2006).

However, while these advantages make such indices indispensable for certain purposes, they impose external normative standards rather than observing the system’s internal operations, leading to both theoretical and empirical shortcomings. Rooted in structural-functionalism or liberal theory, they prioritise ideals such as democratic consolidation or civil rights, which—while valuable for advocacy—diverge from systems theory’s emphasis on self-referential communication. This normative embedding not only shapes what these indices measure but also limits their ability to capture the political system’s autopoietic essence, defined by the government/opposition code.

Consider the Polity IV Project, which scores regimes on a scale from autocracy to democracy based on executive recruitment, authority constraints, and participation (Marshall et al., 2019). It assumes a progression toward democratic ideals, interpreting institutional changes as steps along this path. However, this teleological view conflates the system’s environment with its operations, treating democracy as an inherent goal rather than a contingent programme (Luhmann, 1995; King and Thornhill, 2003). Empirical evidence underscores this gap: resilient non-democracies such as Singapore achieve high economic performance and stability despite low Polity scores, suggesting that normative metrics overlook alternative communicative mechanisms—such as government/opposition dynamics—for decision-making coherence (Thornhill, 2007). Events like unrest or breakdowns are framed as external causes, ignoring how the system reconstructs them as irritations within its own code.

A parallel issue arises in Freedom House’s classification of countries as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free, derived from scores on political rights and liberties (Freedom House, 2025). By centring indicators such as electoral pluralism and judicial independence, it embeds liberal values that belong to moral or legal subsystems, not to the political core of binding decisions structured by government/opposition. This first-order observation evaluates outcomes against human rights norms, overlooking how authority circulates communicatively irrespective of such ideals (Luhmann, 1990a,b; Borch, 2011). Empirically, this leads to inconsistencies, such as underestimating the adaptive capacities of hybrid regimes where low freedom scores coexist with effective irritation processing—as seen in post-democratic adaptations in Europe (Blühdorn, 2019; Blühdorn and Butzlaff, 2018).

Even the more nuanced V-Dem Project, which disaggregates democracy into electoral, liberal, and participatory dimensions (Lührmann et al., 2020; V-Dem Institute, 2025), remains tethered to normative assumptions. Its focus on inclusivity and deliberation implies superior performance in egalitarian forms, yet this actor- and institution-centric approach misses autopoietic closure. Phenomena such as democratic backsliding are analysed as causal regressions rather than as internal adaptations to irritations within the government/opposition framework (Opitz, 2024). Case studies illustrate this limitation: V-Dem’s metrics struggle to explain the persistence of systems like China’s, where high decision outputs and structural couplings (for example, with the economy) sustain autopoiesis without democratic norms—highlighting a blind spot in communicative processes (Thornhill, 2007).

What unites these indices is their reliance on first-order observation: they apply predefined benchmarks to rank systems, blending system logic with societal aspirations. Systems theory, by contrast, advocates second-order observation to reveal how politics self-describes and adapts through its government/opposition code (Luhmann, 1995). Democracy or legitimacy thus emerges as programmes, not universals—contingent tools for applying government/opposition distinctions in specific contexts (Luhmann, 1990a,b; Moeller, 2006). This mismatch has broader implications: normative indices struggle to explain the resilience of non-democratic systems or the communicative coherence in hybrids, framing them as deficiencies rather than functional equivalents (Blühdorn, 2019). Empirical voids are evident in the literature, where systems-theoretic analyses uncover overlooked dynamics such as media-politics couplings in crisis responses (Opitz, 2017).

While acknowledging their utility in policy and accountability, this balanced critique underscores the need for alternatives such as the Political System Index (PSI). By observing internal operations—such as decision-making and irritation processing within the government/opposition code—the PSI fills this empirical and theoretical gap, offering a communication-focused lens applicable to hybrid and transitional contexts (King and Thornhill, 2003; Thornhill, 2007). This shift paves the way for its methodological construction, where theoretical components meet empirical proxies.

Methodology: constructing the Political System Index (PSI)

With the limitations of normative indices in mind, alongside their acknowledged strengths, the Political System Index (PSI) emerges as a methodological innovation aligned with systems theory’s second-order observation. It refrains from judging political quality and instead maps the system’s autopoietic reproduction through the code of government/opposition (Luhmann, 1995). This requires a precise delimitation: the political system is bounded not by institutions or actors, but by communications that recursively link to produce binding decisions, excluding psychic elements such as intentions or values from its core (Luhmann, 1990a,b; Thornhill, 2007; Borch, 2011). By focusing on these operations, the PSI bridges Luhmann’s abstraction with empirical tools, enabling cross-contextual insights while honouring operational closure.

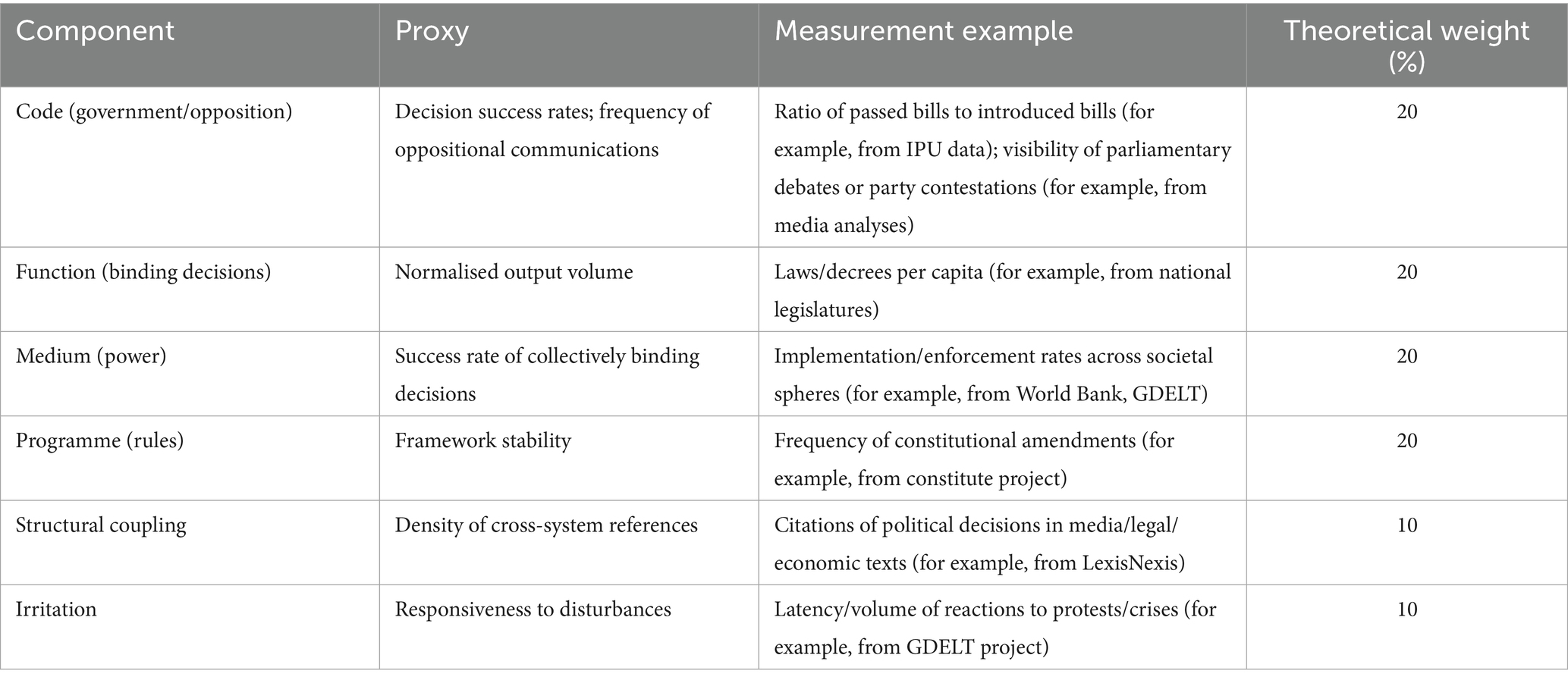

The index revolves around the six theoretical components outlined earlier, each operationalised through proxies that reflect communicative processes without normative overlay (see Table 2 for detailed proxies and weights). The code (government/opposition) is proxied by decision success rates—the ratio of enacted to proposed communications, such as passed legislation to introduced bills—highlighting the system’s selectivity in distinguishing authoritative outcomes from contestations (King and Thornhill, 2003). Additionally, to capture the tangible dynamics of the government/opposition code, a sub-proxy measures the frequency and visibility of oppositional communications (for example, parliamentary debates or party contestations, sourced from legislative records or media analyses), reflecting how the system processes alternatives internally.

Building on this, the function (collectively binding decisions) is captured by the normalised volume of outputs, such as laws, decrees, or treaties per capita, accounting for contextual scale. Higher volumes indicate active stabilisation of expectations, though without implying optimality (Luhmann, 1990a,b). The medium (power) is observed via the success rate of collectively binding decisions, measured by implementation or enforcement rates across societal spheres (for example, compliance with laws in economic, legal, or social domains, sourced from global databases such as World Bank indicators or GDELT). This proxy reflects power’s role as a symbolically generalised medium that connects authority across contexts, relying on the latent threat of force to ensure compliance (Luhmann, 1979; Thornhill, 2007).

The programme (institutional rules) is assessed through framework stability, proxied by the frequency of amendments to constitutions or electoral systems. Frequent changes denote adaptive recalibration, while rarity suggests enduring structures—both interpreted as internal adjustments rather than flaws (Opitz, 2024). This component underscores the programme’s role in regulating the government/opposition code without rigidity.

The next part addresses environmental dynamics by examining how the political system interacts with its surroundings. Structural coupling traces cross-system linkages and is measured through the density of references—for instance, political decisions cited in media, legal rulings, or economic reports—revealing interactions that are coordinated yet differentiated (Luhmann, 2000; Baxter, 2013). Irritation measures responsiveness by analysing the latency and volume of reactions to disturbances such as protests, which are treated as internally reconstructed triggers rather than external causes (Stenner, 2017). Together, these indicators ensure that the PSI captures the system’s adaptive capacity without resorting to causal assumptions.

To integrate these into a composite score, components are weighted to reflect their theoretical roles: code, function, medium, and programme at 20 per cent each, prioritising core reproductive processes; structural coupling and irritation at 10 per cent each, reflecting adaptive interactions (Luhmann, 2012). Indicators are normalised (0–100 via min–max or z-scores) for comparability, then aggregated weightily. High scores signal autopoietic robustness—strong communicative coherence—while low ones indicate vulnerabilities, all without prescriptive intent. This scoring enables equivalence-based comparisons, where systems are assessed on communicative functionality rather than normative hierarchies.

For instance, Table 3 presents hypothetical PSI scores for three countries (the United States, China, and Singapore), derived from publicly available proxies such as legislative data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), implementation rates from World Bank indicators, and media references from news archives. These illustrate how a liberal democracy (the United States) and non-democracies (China, Singapore) might exhibit similar robustness in certain components, highlighting functional equivalences often overlooked in normative indices.

Ultimately, the PSI serves as an observational diagnostic, tracing how systems navigate complexity through communication. This construction not only operationalises theory but also invites applications in comparative and crisis contexts.

Applications of the PSI

With the Political System Index (PSI) now constructed as a robust observational tool, its value extends beyond theory to practical empirical inquiry. Grounded in second-order observation—observing how government/opposition communications within the system process problems of the system and its environment—the index illuminates how political communication persists amid complexity and contingency, shifting focus from normative judgements to functional dynamics (Luhmann, 1995). This enables researchers to explore political systems not as static entities but as adaptive networks, revealing patterns often overlooked in traditional analyses.

A key application lies in comparative political research, where conventional typologies—democracy versus autocracy—impose hierarchical classifications. The PSI instead compares systems based on communicative equivalence: a parliamentary democracy and a one-party state might both exhibit strong decision outputs or irritation responses, despite differing institutional structures (King and Thornhill, 2003; Thornhill, 2007). This approach proves particularly useful for hybrid regimes that elude standard categories, highlighting their internal coherence through proxies such as programme stability or coupling density. For instance, drawing on the hypothetical scores in Table 3 (Methodology section), the United States (composite 74.0) shows moderate robustness with lower medium and irritation scores, potentially reflecting polarisation in implementation rates and crisis responses, while China (83.5) and Singapore (82.0) demonstrate higher autopoietic coherence through efficient code and function components. Such equivalence-based comparisons avoid normative rankings, instead emphasising how diverse systems achieve similar communicative functionality via government/opposition dynamics, as evidenced in studies of resilient authoritarianism.

The index also supports longitudinal studies, tracking systemic evolution over time. By applying PSI scores retrospectively—before and after events such as the COVID-19 pandemic—researchers can observe adaptations such as heightened legislative activity or media-policy linkages without causal attributions (Opitz, 2017). This temporal lens uncovers resilience as the maintenance of autopoiesis, offering insights into how systems recalibrate amid transitions or reforms. For example, pre- and post-pandemic data might reveal increased structural coupling scores in countries such as Germany, where policy-media interactions intensified, illustrating adaptive co-evolution without judging democratic quality.

In crisis contexts, the PSI reframes analysis from actor-driven failures to systemic reflexivity. A protest, for instance, gains relevance through its translation into political responses within the government/opposition code, measured by irritation latency (Stenner, 2017). This reveals cognitive openness while preserving closure, complementing resilience studies where high code-function scores signal sustained operations despite volatility (Baxter, 2013; Borch, 2011). Empirical applications could include analysing the 2020–2021 global protests, where PSI proxies such as reaction volume highlight varying irritation processing across systems.

Interdisciplinary extensions further amplify the PSI’s utility. In media studies, it can examine digital platforms as sources of irritation, such as viral campaigns prompting policy shifts (Tække, 2020). Legal scholars might map politics-law couplings via judicial references in decisions, preserving subsystem distinctions (Moeller, 2011; Luhmann, 2004). In technology sociology, algorithmic tools could emerge as novel irritants, analysed through responsiveness metrics.

Moreover, the PSI fosters meta-reflection on observation: as a scientific construct under the true/false code, it acknowledges its own contingencies and blind spots (Luhmann, 1995; Pires and Sosoe, 2021). While non-prescriptive, it can highlight operational asymmetries—such as weak irritation processing—for diagnostic purposes, informing indirect inquiries into adaptive capacities (Van Assche and Verschraegen, 2008; Campilongo et al., 2021).

In essence, the PSI equips a versatile framework for dissecting political communication landscapes, from comparisons to crises, through the lens of government/opposition dynamics. Yet, as with any observational tool, it encounters inherent challenges, which the following section addresses to maintain theoretical reflexivity.

Challenges and limitations

While the Political System Index (PSI) provides a theoretically coherent and empirically grounded alternative to normative political metrics, it is not without significant limitations. These stem from both practical issues—such as data availability and indicator design—and deeper epistemological tensions in applying autopoietic systems theory to measurable forms. As Luhmann cautioned, systems theory rejects the illusion of complete transparency in social observation (Baraldi et al., 2021), positioning the PSI as a contingent construct that highlights certain facets of political systems while inevitably obscuring others.

A primary methodological hurdle lies in operationalising abstract concepts such as the government/opposition code or the symbolic medium of power. For instance, proxies such as decision success rates and oppositional communication frequency may quantify formal outcomes but fail to capture nuanced communications, including strategic silences or informal negotiations that reflect systemic selectivity within the government/opposition framework. Similarly, the success rate of collectively binding decisions—used to measure the medium of power—may be distorted by institutional, cultural, or external factors, complicating its alignment with power’s role as a symbolically generalised medium reliant on the latent threat of force (Luhmann, 1979; Thornhill, 2007).

This challenge intensifies with irritation, which systems theory frames as the selective reconstruction of external disturbances rather than direct causation. Yet empirical indicators, such as the latency between protests and policy responses, often impose linear causality, reducing complex communicative transformations within the government/opposition code to simplistic temporal metrics. Structural coupling also resists quantification; measures such as references to political decisions in media or legal texts may overlook the depth or reflexivity of inter-system interactions, mistaking superficial mentions for meaningful co-evolution.

Beyond these conceptual issues, practical constraints arise from data limitations and contextual variability. Key sources—legislative records, implementation data, protest responses, or media archives—are frequently incomplete, biased, or inaccessible, particularly in authoritarian contexts, undermining the PSI’s reliability. Interpretations also vary: high constitutional amendments might indicate adaptability in one system but instability in another, while low implementation rates could signal systemic constraints or differing societal expectations, risking misleading comparisons without contextual nuance.

At a deeper level, the PSI introduces epistemological paradoxes. As a scientific tool operating under the true/false code, it observes political systems asymmetrically, reconstructing autopoiesis through inferences rather than direct access. This risks reification, where numerical scores imply stable entities rather than fluid, operationally contingent processes—contradicting systems theory’s emphasis on ongoing communication (Luhmann, 1995). The shift to the government/opposition code and revised proxies, such as implementation rates for the medium, aim to mitigate these issues but cannot fully resolve the inherent complexity of capturing communicative dynamics empirically.

The PSI’s non-normative approach, while theoretically consistent, may also limit its appeal to reform-oriented researchers and policymakers seeking evaluative tools. Its analytical detachment privileges observation over prescription, making it more suitable for theoretical and diagnostic inquiry than for advocacy or governance reform. Ultimately, these limitations do not undermine the PSI but instead underscore the necessity of reflexivity. As a second-order observation, it reveals communicative patterns sustaining political systems through government/opposition dynamics amid modern differentiation, deriving clarity from embracing observational complexity rather than pursuing unattainable completeness.

Conclusion and future directions

This article has introduced the Political System Index (PSI) as a theoretically grounded tool for observing political systems through Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory. Unlike normative indices—such as those evaluating democracy, legitimacy, or institutional quality—the PSI employs a non-normative, communication-centred approach. It redirects attention from what systems ought to achieve to how they function: autopoietically reproducing through the government/opposition code, generating binding decisions, and selectively responding to environmental complexity.

The PSI operationalises Luhmann’s core elements—code, function, medium, programme, structural coupling, and irritation—through empirical proxies that capture internal communicative processes while avoiding normative or institutional biases. By assigning equal weights (20% each) to code, function, medium, and programme, and 10% each to structural coupling and irritation, it measures tangible political dynamics while remaining true to systems theory. This framework enables second-order observation, allowing researchers to analyse how communications within the government/opposition code observe and interact with their environment, thereby emphasising structured communication over intentions or values.

By linking abstract theory to empirical practice, the PSI addresses the common critique of Luhmann’s work as conceptually sophisticated yet empirically elusive. It positions systems theory as a practical heuristic, revealing mechanisms through which political systems process contingency, maintain differentiation, and adapt without recourse to anthropocentric or teleological assumptions.

Yet, the PSI also underscores the limits of observation. As a scientific artefact operating under the true/false code, it cannot fully access the political system’s distinct logic. It offers no objective truth or prescriptive judgement, but rather a contingent schema that prioritises communication over content, structure over substance, and operations over intentions—reframing political analysis as the study of processes, not entities. The revised proxies, such as implementation rates for the medium and oppositional communication frequency for the code, enhance empirical precision yet remain constrained by data and interpretive challenges.

Future directions for research are manifold

First, empirical pilots across diverse contexts could refine the PSI, testing its sensitivity to crises or programme shifts while adjusting proxies for validity and reliability. Second, its architecture could be extended to other subsystems: for instance, developing a media index (information/non-information) or an economic index (payment/non-payment) to enable cross-domain analyses of co-evolution and structural coupling across law, science, or education. Third, computational methods—such as natural language processing for debate analysis, machine learning for irritation pattern detection, or network analysis for coupling density—could enhance its analytic depth while preserving theoretical rigour. Finally, the PSI invites epistemological reflection. As a form of third-order observation, it examines how observations themselves construct meaning, reminding researchers that all metrics, however sophisticated, are situated and selective.

In sum, the PSI reaffirms Luhmann’s enduring relevance amid global interdependence and epistemic flux. It provides a non-normative analytical tool to observe the improbable coherence of political systems through government/opposition communication, resonating with Luhmann’s insight that society endures not through ideals, but through the ongoing, selective operations of communication—stable yet always observing.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by a grant from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (grant no. GGPM-2023-036).

Acknowledgments

The author received institutional support from Institute of Ethnics Studies (KITA) in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used for translation, editing, and proofreading during the preparation of this manuscript. The author has carefully reviewed all AI-assisted outputs and take full responsibility for the content, accuracy, and integrity of the final manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown.

Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Baraldi, C., Corsi, G., and Esposito, E. (2021). Unlocking Luhmann: a keyword introduction to systems theory. (Translated by Carl Morgner.). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Baxter, H. (2013). Niklas Luhmann’s theory of autopoietic legal systems. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 9, 167–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134027

Blühdorn, I. (2019). The dialectic of democracy: modernisation, emancipation and the great regression. Democratisation 27, 389–407. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1648436

Blühdorn, I., and Butzlaff, F. (2018). Rethinking populism: peak democracy, liquid identity and the performance of sovereignty. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 22, 191–211. doi: 10.1177/1368431017754057

Campilongo, C. F., Amato, L. F.de, and Barros, M. A. L. L.de, eds. (2021). Luhmann and socio-legal research: an empirical agenda for social systems theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

Diamond, L. (1999). Developing democracy: toward consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Freedom House. (2025). Freedom in the world 2025: an uphill battle to safeguard rights. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2025/uphill-battle-safeguard-rights (Accessed October 27, 2025).

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The third wave: democratisation in the late twentieth century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

King, M., and Thornhill, C. (2003). Niklas Luhmann’s theory of politics and law. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lindberg, S. I. (2006). Democracy and elections in Africa. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and power. (Translated by Howard Davis, John Raffan, and Kathryn Rooney). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Luhmann, N.. (1986). “The autopoiesis of social systems.” In Sociocybernetic paradoxes: observation, control and evolution of self-steering systems, edited by F. Geyer and J. Zouwenvan der, 172–192. London: Sage.

Luhmann, N. (1990b). Political theory in the welfare state. (Translated by John Bednarz Jr.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems. (Translated by John Bednarz Jr. and Dirk Baecker.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2000). The reality of the mass media. (Translated by Kathleen Cross.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2012). Theory of society, vol. 1. (Translated by Rhodes Barrett.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2013). Theory of society, vol. 2. (Translated by Rhodes Barrett.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lührmann, A., Tannenberg, M., and Lindberg, S. I. (2020). Autocratisation surges—resistance grows: democracy report 2020. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem).

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., and Jaggers, K. (2019). Polity IV project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2018. Vienna, VA: Center for Systemic Peace.

Opitz, S. (2017). Simulating the world: the digital enactment of pandemics as a mode of global self-observation. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 20, 392–416. doi: 10.1177/1368431016671141

Opitz, C. (2024). Democratic innovations beyond the deliberative paradigm: a re-conceptualisation drawing on systems theory. Democratisation 31, 1695–1718. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2024.2340636

Pires, Á., and Sosoe, L. K. (2021). Epistemological and empirical challenges of Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory: an interview with professors Álvaro Pires and Lukas Sosoe. Rev. Direito GV 17:e2109.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schoeneborn, D. (2011). Organisation as communication: a Luhmannian perspective. Manag. Commun. Q. 25, 663–689. doi: 10.1177/0893318911405622

Seidl, D., and Schoeneborn, D.. (2010). Niklas Luhmann’s autopoietic theory of Organisations: contributions, limitations, and future prospects. IOU working paper no. 105. Zurich: University of Zurich, Institute of Organisation and Administrative Science.

Stenner, P. (2017). Liminality and experience: a transdisciplinary approach to the psychosocial. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tække, J. (2020). “Luhmann and digital media: observing the contingency of communication in the digital age” in Luhmann and digital humanities. ed. M. K. Madsen (Cham: Springer), 45–67.

Thornhill, C. (2007). Niklas Luhmann, Carl Schmitt and the modern form of the political. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 10, 499–522. doi: 10.1177/1368431007075966

Van Assche, K., and Verschraegen, G. (2008). The limits of planning: Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory and the analysis of planning and planning ambitions. Plan. Theory 7, 263–283. doi: 10.1177/1473095208094824

V-Dem Institute. (2025). Democracy report 2025: 25 years of autocratisation. Available online at: https://www.v-dem.net/documents/60/V-dem-dr__2025_lowres.pdf (Accessed October 27, 2025).

Keywords: Niklas Luhmann, social systems theory, autopoiesis, political system, second-order observation, functional differentiation, structural coupling, irritation

Citation: Endut R (2025) Observing the political system: designing a non-normative index based on Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1668208. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1668208

Edited by:

Jan-Erik Refle, Université de Lausanne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Bojan Vranic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaLucas Fucci Amato, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Dirk Baecker, Zeppelin University, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Endut. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ramze Endut, cmFtemVAdWttLmVkdS5teQ==

Ramze Endut

Ramze Endut