Abstract

The study aimed to analyze the political integration of ethnic minorities in the post-Soviet states of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan), taking into account modern national policies and socio-political processes. The work used a mixed design. The quantitative stage included a survey of 320 respondents, which made it possible to assess indicators of trust and political effectiveness. The qualitative stage consisted of 40 semi-structured interviews aimed at revealing the mechanisms of integration of statistical patterns. The study indicated that electoral participation is the dominant form of political activity; however, non-electoral practices (membership in parties, public initiatives) are much less common. In all countries, national elections attract more respondents than local ones, but the gap is smallest in Kazakhstan (7%), where trust in institutions is higher. In Kyrgyzstan, there is stronger civic engagement outside elections, which correlates with the presence of horizontal networks. In Uzbekistan, integration rates are generally lower due to institutional closure and risks of self-censorship. Analysis of identity profiles revealed a monotonic gradient of trust: integrated (M ≈ 53) > assimilated (M ≈ 49) > separated (M ≈ 41) > marginalized (M ≈ 36). The combination of ethnic and national identities works as a “bridge of trust” to institutions.

1 Introduction

1.1 Context and justification

The legacy of Soviet forced centralization is still felt in the Central Asian region due to centralized governance in the post-Soviet space and models of managing ethnic diversity that shaped how states approach this issue even today (Zadayev, 2024). Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan differentiate themselves through a spectrum of approaches to integrating political life, which consist of various tools—from managed multiculturalism to direct assimilation.

The diverse experiences of the independent republics that formed on the territory of the former Soviet Union suggest a balanced approach to the formation of a single national identity. However, each Central Asian state addresses the problems of ethnic minorities differently. For example, Kazakhstan positioned itself as a regional leader in gradual ethnic assimilation with its Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan (APK), which institutionalized minority integration and intercultural communication into public life. In contrast, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan exhibit more fragmented views and varying state support for languages, cultural environments, and the political participation of ethnic minorities in public life (Somfalvy, 2021). Kazakhstan's integration policy, particularly its motto “unity in diversity,” as well as its self-presentation as a multiethnic and tolerant society, allows for a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and obstacles to minority integration. Unlike other regional contexts where information and government transparency are easily accessible, this positioning is significantly more promising. This positioning allows us to consider Kazakhstan as an illustrative example of an official model of interethnic interaction, however, assessments of its effectiveness in the literature are contradictory.

Significant gaps in the research area are that the scientific issues of integrating ethnic minorities in Central Asia are generally presented as individual case studies on the situation in each specific country. There is no question of comparing empirical data under such conditions, although this would have allowed us to focus on minority perspectives in different national contexts. Some studies have attempted to analyze ethnic conflicts or language policies, but very few have tried to compare formal political integration processes in several countries simultaneously (Khanin, 2023). Secondly, there is limited research using primary data on the consequences of such approaches, particularly in terms of participation, representation, and legitimacy among specific minority groups. Thirdly, few studies go beyond political science to highlight long-term strategies for promoting integration that include educational technologies.

However, this is where the main gap arises, which this study aims to address. Previous work has hardly analyzed the political integration of ethnic minorities in a comparative multi-country perspective, and even less has it considered youth as a separate political category. Much of the knowledge about minority political activism is based on macro-political assessments or single cases, which does not allow us to understand how and why young representatives of different minorities are included in political life in different ways. There is also not enough empirical data on how acculturation profiles (integration, assimilation, separation, marginalization) affect political behavior and trust in institutions. Thus, there is a need for a comprehensive interdisciplinary analysis that simultaneously considers both the structural policies of states and the individual identity orientations of ethnic minority youth.

1.2 Problem statement

The issue of integrating ethnic groups in Central Asian countries is not only a separate political matter but also a problem of broader regional and global significance. In ethnically diverse countries, comprehensive integration policies are crucial for achieving inclusive governance, national cohesion, and lasting social peace. Successful integration of different social groups strengthens social cohesion, promotes intergroup understanding, and reinforces the legitimacy of state institutions. In Central Asia, where borders were drawn for administrative reasons during the Soviet era, disputes over ethnic realities still exist. Managing ethnic diversity in such circumstances is crucial. While the governments of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan are focused on their minority integration strategies within a comparative socio-historical framework, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan serve as instructive contrasts. Turkmenistan has introduced a strict form of control over minority self-expression. From another perspective, in Tajikistan, ethnic politics is often dominated by regional characteristics, and the Pamiri and Uzbek minorities face varying degrees of social isolation. The theoretical basis of this issue lies in the idea that identity and belonging, as well as participation, are phenomenological concepts that arise from state actions, historical narratives, and everyday practice. Central Asian countries still lack systematic methods for determining the true level of political activity among ethnic minorities, especially among young people, despite the existence of official integration programs. Less attention is paid to the study of civic participation and mechanisms of political integration in everyday life than to the study of interethnic conflicts, security issues, or general aspects of national policy. This makes it necessary, from both a scientific and practical perspective, to identify the elements that influence the political integration of minorities, to reveal the obstacles and opportunities for this process, and to investigate the relationship between political behavior and national and ethnic identity. Central Asian countries still lack systematic methods for determining the true level of political activity among ethnic minorities, especially among young people, despite the existence of official integration programs. In academic studies of Central Asia, much attention is paid to interethnic conflicts and security aspects, while everyday civic participation remains less researched (Gaur, 2022). Thus, despite the extensive literature on national policies, ethnic relations, and institutional mechanisms for regulating diversity, there is little research on how these policies affect the actual forms of civic engagement of ethnic minority youth in different countries. It is this gap that determines the logic and purpose of our study, which combines quantitative and qualitative analysis in three post-Soviet Central Asian states.

1.3 Objective and research

Issues Considering national policies and current socio-political processes, the article's goal is to examine the mechanisms of ethnic minorities' political integration in Central Asian post-Soviet governments. The relationship between national and ethnic identities, as well as how various acculturation profiles—integrated, assimilated, separated, and marginalized—affect civic engagement, political participation, and institutional trust, are given special consideration. The following research topics were established to accomplish this goal:

-

To ascertain the degree of civic engagement and political participation among ethnic minority youth in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan, as well as to describe the main factors affecting these metrics.

-

To identify the barriers for the political integration of ethnic minorities in each of the three countries through an analysis of expert interviews with community leaders, activists, and government representatives.

-

Analyze how the combination of ethnic and national identities influences the attitudes of ethnic minority youth toward state institutions and their integration into political life.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical foundations

The study of political integration in multi-ethnic and post-colonial states is based on several theories (consociationalism, multiculturalism, and assimilation). These theories have proposed both competing and supportive concepts for the inclusion of ethnic minorities in the political, social, and cultural framework of societies.

Consociationalism, developed by Arend Lijphart, concentrates on coping with divided societies through the power-shared stability provision of group autonomy, proportional representation, and mutual veto. Lijphart encountered consociational democracy while considering the case of sustaining democratic governance in deeply divided societies like the Netherlands and Belgium, which have pronounced religious, linguistic, or ethnic fissures (Guénette, 2021). On the other hand, some critics suggest that consociationalism can deepen fractures by entrenching identity politics, undermining long-term integration through reliance on fragmentary parallel group allegiances instead of a singular national identity. In this aspect, post-Soviet Central Asia does appear to fit this theory's scope—especially where ethnic minorities are, at least nominally, included as members in some advisory councils or governmental positions (Iskakova, 2023).

Multiculturalism argues for the endorsement of cultural rights, education that reflects a blend of different groups, and the symbolic presence of minority cultures (Wilkinson, 2021). Multiculturalism advocates that cultural identity is crucial for individual autonomy and belonging. Wilkinson (2021) divided self-governance rights for national minorities and indigenous peoples and “polyethnic rights” regarding immigrants. This division is useful in Central Asia. The post-Soviet governance systems have incorporated multicultural approaches, albeit superficially and in a selective fashion. For example, the Central Asian republics' constitutions proclaim equal status for all citizens and allude to the contributions of different ethnic groups. Kazakhstan's self-perception as “diversity in unity” embraces multiculturalism, although, much like the other republics, it fails to deliver on political equality or meaningful self-governance to the minorities.

Assimilation requires that minorities adopt the language and culture of the dominant society as a precondition for being fully integrated. This is directly relevant to RQ3 since it forecasts reduced participation of minorities in political activities when cultural assimilation is imposed without unaccountable representation. In Western Europe and North America, this is historically linked to the nation-state model. Assimilation was rationalized in the name of facilitating national integration, social cohesion, and a single public identity. During the Soviet era, there were Russification policies designed to forcibly teach the Russian language and culture in non-Russian republics, which often led to the obliteration of local languages and traditions (Shchepetylnykova and Oleksiyenko, 2024).

The approaches undertaken by the newly independent states during the post-Soviet period differ greatly. For example, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan have adopted ultra-nationalistic policies that tend to marginalize any ethnic identities that are subordinate (Lemon and Antonov, 2021). On the other hand, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have declared a more moderate approach to managing ethnic diversity, but the degree of real inclusiveness of these models is assessed differently (Gaur, 2022). On the other hand, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan lived up to expectations by seeking a moderate approach, claiming to embrace diversity while attempting to foster a common identity focused on citizenship rather than ethnicity. The Assembly of People gives formal representation to ethnic minorities, and the government provides political support for minority culture and language schools. Unlike Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan paints a more straightforward picture. Here, inter-ethnic conflicts, especially between the Kyrgyz and the Uzbeks, have resulted in violence, including the 2010 Osh clash (Begalievich, 2022). Notably, these voting contests lack political competitiveness and vibrant civil activity at competitive elections, suggesting that pending minority varying policies are supported by an ever-evolving balance of domestic political forces. Shavkat Mirziyoyev's reforms have allowed Uzbekistan to slowly reintegrate with global systems post-Islam Karimov's reign, especially concerning the treatment of minorities (Jumayeva, 2025). In Kazakhstan inter-ethnic conflicts, especially between the Kyrgyz and the Uzbeks, have resulted in violence, including the 2010 Osh clash (Begalievich, 2022). Notably, studies note limited levels of political competition in electoral processes, which affects the opportunities for minority representation (Jumayeva, 2025). Shavkat Mirziyoyev's reforms have allowed Uzbekistan to slowly reintegrate with global systems post-Islam Karimov's reign, especially concerning the treatment of minorities (Jumayeva, 2025).

To align the theoretical framework with the research questions, this study proposes an integrated conceptual model that brings together three leading approaches –consociationalism, multiculturalism, and assimilation – into a single analytical framework.

The model assumes that the political integration of ethnic minorities is determined by the interaction of three dimensions:

-

Institutional inclusion (consociationalism): access to representation, participation, and consultation mechanisms.

-

Cultural and symbolic inclusion (multiculturalism): language politics, cultural visibility, identity legitimacy.

-

Pressures of identity alignment (assimilation): expectations to accept the dominant identity as a condition for civic participation.

These dimensions shape youth acculturation profiles (integration, assimilation, separation, marginalization), which, in turn, determine the level of civic engagement, political participation, and trust in state institutions.

2.2 Regional studies

Modern scholars offered some of the first detailed accounts concerning the culture wars over identity politics in Central Asia, analyzing the impact of Soviet legacies on the development of nationalist ideologies in the region (Lee, 2023). Although these analyses have been instrumental in illustrating the denial of inclusivity for non-titular groups' narratives, they do not pay attention to the cross-country systematic differences of institutional frameworks. Another example would be the studies, which looked at Kyrgyz-Kazakhstan language policies or inter-ethnic relations and conflict focused from the perspective of the state, without considering comparative frameworks (Cross et al., 2022; Lee, 2023). Modern scholars also documented the political significance of ethnicity concerning the turbulent politics of Kyrgyzstan, particularly regarding post-ethnic strife in Osh during 2010 (Kokaisl, 2025).

The approach that characterizes every state as a distinct specimen creates a gap for systematic cross-country evaluation. Very few attempt a comprehensive investigation of the systemic interplay between institutional configuration, historical context, and political regime in explaining the differing outcomes of minority integration across the subcontinent (Cross et al., 2022).

The reports released by the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities dealing with the participation and engagement of minorities tend to be regionally focused and look at education in a prescriptive and policy-oriented framework without engaging in analysis or hypothesis formulation (Wolff, 2023). Recent quantitative studies of youth political participation in Kazakhstan have indicated that political culture and civic responsibility strongly influence youth engagement. However, patriotic feelings play a more ambiguous role (Baizhumakyzy et al., 2025). However, such studies focus on youth in general and do not differentiate between ethnic minority youth, nor do they compare outcomes across Central Asian states; as a result, the specific mechanisms linking identity configurations, acculturation profiles, and political participation among minority youth remain poorly understood. Furthermore, research by international institutions tends to be plagued by issues of limited availability, political sensitivity, or methodological inconsistency between countries. Those using powerful cross-national techniques such as matched case comparisons or large-N survey analyses are still few and far between. There remains a gap in understanding why some states, such as Kazakhstan, have, for better or worse, developed more sophisticated (albeit state-managed) forms for minority consultations, while others, such as Uzbekistan, have ignored formalized systems of infrastructure for the representation of minorities.

There is a lack of rigorous cross-national research predicated on matched-case comparisons or large-N survey designs that examines why some states, such as Kazakhstan, have developed structured, albeit controlled, consultation systems contrasted with Uzbekistan's lack of formal representation. Ethnic Russians, Uzbeks, Uighurs, and Dungans, among other ethnic minorities, possess distinct cultures and political objectives that often get overlooked through the prism of state-centered analyses (Kokaisl, 2025). The current work intends to fill these gaps using a comparative, correlational design that investigates systematically the strategies of integrating minorities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

2.3 Kazakhstan in focus

In academic literature, Kazakhstan is often cited as an example of a state model of managed multiculturalism (Gaur, 2022). For a long time, Kazakhstan has been known as a regional model in the management of ethnic diversity in Central Asia, often described as a case of managed multiculturalism. The phrase captures an approach from above, a state-driven model of ethnic coexistence that promotes harmony while enforcing strict political control (Nassimov, 2024). This approach, like other post-Soviet ones, has received praise for maintaining relative ethnic stability within a highly complex society, but has also been criticized for diminishing ethnic self-governance, democracy, and representation.

The distinctive demographic structure of Kazakhstan, a product of Soviet resettlement policies, forced migrations, and subsequent economic migration, makes the questions of identity and ethnic integration extremely pertinent after 1991 (Nassimov, 2024). As is customary, the APK functions as a cultural and political umbrella organization for scheduled nationalities that aid in its objective of incorporation into Kazakhstan. Officially, the ANC is positioned as a tool for maintaining interethnic harmony; however, research emphasizes its predominantly consultative and symbolic nature (Daminov, 2020; Serikzhanova et al., 2024). Serikzhanova et al. (2024), who analyze the influence of the APK in public life, conclude that although its participation is mostly ceremonial, all its efforts are funded and symbolically martial through deepened cultural activity. Wood (2022) contends that the APK is a representative of multiculturalism in its most controlled form—a hybrid of ethnic organizations and formal politics, which offers little in the way of real legitimacy or empowerment to minorities.

Kucherbayeva and Smagulova (2023) discuss the neglect of minority languages in educational and media policies, which has aggressively shifted toward prioritizing the use of Kazakh, stifling cultural pluralism. Newer scholarship has focused on the gap between symbolic recognition and actual inclusion.

The selective integration policies of Kazakhstan are also evident in its educational system. Starting from 2016, several reforms focused on the system of “trilingual education,” which incorporated Kazakh, Russian, and English (Yedgina et al., 2023). While intended to increase global readiness, these reforms disproportionately impact minority students, especially those who are neither native speakers of Kazakh nor Russian. The “Mangilik El” (Eternal Nation) doctrine, which has been sustained by the state since 2015, emphasizes oneness and stability while wrapping Kazakh culture in the default essence of national identity (Insebayeva and Insebayeva, 2022). International institutions like the OSCE and UNESCO have praised Kazakhstan's attempts to prevent conflict and maintain inter-ethnic peace (OSCE, 2019, 2021). Nonetheless, more recent critiques suggest that these praises do not account for underlying issues. Recent empirical work on ethnic Uzbeks in Kazakhstan highlights both relatively secure access to education and employment and a gradual shift away from the Uzbek language, suggesting that integration often proceeds through subtle forms of assimilation rather than through overt exclusion (Tolesh, 2023).

Notably, researchers have started to explore how youth engage with multiculturalism and national identity. Ethnic minority groups are often caught in competing limbs: the “Kazakhstan identity” civic unity framework compels them to embrace; however, they remain trapped by language, education, and inclusion barriers. Tsakhirmaa (2022) observes that many ethnic minority youth construes very few possible paths to mobility, especially if they do not speak fluent Kazakh. This points to a widening gulf between the state's multiculturalism rhetoric and the realities of younger minority constituents. As is revealed in post-2016 scholarship, multiculturalism in Kazakhstan is less about diversity governance and more about the separated, staged, enforced cohesion-homogenization controlled by the state without true power-sharing (Liu et al., 2022; Gallo, 2021). Besides, everal researchers argue that the official multiculturalism policy in Kazakhstan is focused mainly on maintaining controlled social harmony and does not provide real opportunities for minorities (Liu et al., 2022). Kazakhstan is a prime example of managed multiculturalism, but even in this “most institutionalized” context, there is a gap between the official rhetoric of inclusion and the real barriers for ethnic minority youth, especially in matters of language policy, educational access, and political participation. This highlights the importance of a comparative approach that allows us to identify both unique and common characteristics of integration models in the region.

2.4 Synthesis and research gap

An assessment of the existing literature shows that despite the development of theoretical frameworks (consociationalism, multiculturalism, assimilation) and numerous descriptive studies of Central Asia, the literature lacks three key elements.

First, the studies focus on state institutions rather than on the actual political experiences of ethnic minorities, especially youth.

Second, comparative “most similar systems” designs are rarely used, making it impossible to identify mechanisms that explain the differences between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

Third, there is little research on how acculturation profiles shape the political behavior, participation, and institutional trust of minority youth.

This study fills this gap by offering a comparative analysis of three post-Soviet Central Asian states based on an integrated conceptual model that links state policies, identity, and youth political participation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

The study of the political integration of ethnic minorities in post-Soviet Central Asia is based on a mixed methodological approach. This approach involves synthesizing quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis strategies. This design was chosen due to the complexity of the subject, as integration processes encompass both objectively measurable indicators (election participation, level of trust in institutions, self-identification) and subjectively constructed meanings (feeling of belonging to a political community, interpretations of one's status, experiences of discrimination or inclusion). At the same time, the design is based on a pragmatic paradigm, which involves selecting methods not by their affiliation with the “qualitative” or “quantitative” camp, but by their ability to most fully answer the research questions. This allowed for the combination of descriptive statistical indicators with a critical analysis of the meanings and practices inherent in ethnic communities. Epistemologically, the research is oriented toward critical realism: it proceeds from the understanding that political integration has both objective dimensions and a multidimensional social construction that cannot be understood without considering the context.

3.2 Design logic and structure

The research is structured according to a sequential explanatory design. In the first stage, a quantitative survey of young people from ethnic minorities was conducted in three countries. The main task of this stage was to identify the main trends regarding political participation, the level of trust in institutions, integration attitudes, and identity orientations. In the second stage, the survey results were refined through qualitative in-depth interviews with community leaders, representatives of government bodies, experts, and activists. This stage aimed to explain the main reasons for the identified quantitative patterns, as well as to highlight the mechanisms and barriers to political integration.

This sequence allowed us to avoid the limitations of each method: quantitative data provides comparability and representativeness, while qualitative data offers interpretive depth and the identification of hidden meanings. Overall, the study is organized as a cross-country comparison based on the logic of most-similar systems design: three states share a common Soviet heritage and multi-ethnic structure but differ in their level of political liberalization, models of ethnopolitics, and institutional integration practices. This made it possible to identify general patterns and differences determined by the specific characteristics of each country.

3.3 Sampling and respondent selection logic

The selection of respondents was based on purposive sampling, as the study focuses on groups directly involved in political integration processes or capable of providing relevant information. The selection of participants was carried out through public organizations and cultural centers. Information about the research was disseminated through local NGOs, cultural societies, and ethnic minority student organizations. Information notices calling for participation, a brief description of the research purpose, and the researcher's contact information were posted in these organizations. A portion of the respondents were recruited through universities (humanities and social sciences faculties), where a questionnaire was distributed among students. Student councils and youth activists were also used to help disseminate information among their peers. To reach a wider audience, information about the research was disseminated on social media (Facebook, Telegram, and Instagram) through ethnic community groups and chats. For this purpose, short announcements were specifically created, indicating the topic, participation conditions, and a link to an electronic form (Google Forms or Qualtrics). Given the sensitivity of the topic and the varying levels of openness of political systems in Central Asia, a “snowball sampling” element is also used: initial contacts helped reach new respondents through network connections. This combination contributed to the formation of a sample that included both formal and informal actors in the integration processes.

Although the total number of respondents is sufficient for quantitative analysis (N = 320), the selection method—a combination of purposive sampling and the snowball method—does not allow us to consider it statistically representative of all ethnic minorities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Uzbekistan. Thus, the results should not be interpreted as general estimates for all groups, but as analytical and research patterns specific to our specific sample of ethnic minority youth. All cross-country comparisons are indicative and reflect trends within the sample, not population values.

The sample in this study is analytical in nature and is not statistically representative of the entire ethnic minority population in the three countries. Due to the use of purposive sampling and the element of “snowballing”, the results should be interpreted as reflecting trends within the study group, rather than precise parameters for all ethnic communities. Thus, the data obtained allow us to identify structural patterns, typical mechanisms and comparative differences, but cannot be directly generalized to the entire population of ethnic minority youth in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan or Uzbekistan.

3.4 Geographical coverage

The study covered three countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. The choice of these states was determined by the common post-Soviet context and the presence of significant differences in their approaches to ethnopolitics. This, in turn, made it possible to conduct a comparative analysis. Within countries, priority was given to regions with a higher concentration of ethnic minorities (the southern regions of Kyrgyzstan, the eastern regions of Kazakhstan, and the border areas of Uzbekistan).

Kazakhstan was chosen because of its internationally publicized adoption of managed multiculturalism, as is evident through frameworks like the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan. This body allows for the active participation of ethnic minorities in politics at a lower level, through an auxiliary parliament, and is frequently cited both in domestic and foreign policy settings as a benchmark of interethnic cooperation. It's just the opposite for Kyrgyzstan, where the political environment is more fragmented and volatile. It has experienced bouts of ethnic violence, such as the 2010 Osh clashes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, and does not have a mounting structure for ethnic minority rule like the Assembly in Kazakhstan (Begalievich, 2022). As a result, this is different in terms of the logic of politics and the rationality of politics.

Uzbekistan occupies an intermediate position on the spectrum of identity policies, being more assimilationist than Kazakhstan. While maintaining a singular Uzbek identity and abstracting minority cultures from the public sphere, it does have a strong centralized state, like Kazakhstan. More recent reforms under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev have expanded the scope of civic participation, but their impact on minority inclusion remains largely uncharted (Jumayeva, 2025). Together, the inclusion of participants from these three countries represents a strategically diverse but methodologically coherent sample. These countries manage ethnic diversity in vastly different ways; however, they are similar enough in their structural conditions to allow for a meaningful comparison. All possess large minority populations, such as Russians, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Uyghurs, who are rich in resources to analyze the interplay between state policy, institutional frameworks, and political participation (Jumayeva, 2025). With these selected cases, Central Asia is useful for constructing a focused and credible analysis of the factors determining minority political integration.

3.5 Quantitative part (survey)

The survey collected data from 320 respondents. The main target group is young people aged 18–30 who belong to ethnic minorities. This category was chosen because the younger generation defines the prospects for future integration, demonstrates new forms of political participation, and is more open to transformative influences. The main selection criteria were related to age (18–30 years old), belonging to an ethnic minority (self-identification), citizenship of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Uzbekistan, and residing in regions with a concentration of minorities (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Country | N | Ethnic groups | Sex (M/F) | Age (18–24/25–30) | Habitat | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 110 | Russians (30), Uyghurs (25), Uzbeks (30), Koreans (25) |

55/55 | 60/50 | 70 urban/40 rural | Almaty, Shymkent and border regions |

| Kyrgyzstan | 100 | Uzbeks (30), Dungans (25), Russians (20), Tajiks (25) |

50/50 | 55/45 | 60 urban/40 rural | Southern regions (Osh, Jalal-Abad) |

| Uzbekistan | 110 | Tajiks (30), Karakalpaks (25), Russians (25), Koreans (30) |

55/55 | 65/45 | 65 urban/45 rural | The sample covers Tashkent, Samarkand, Fergana |

| Total | 320 | – | 160/160 | 180/140 | 195 urban/125 rural |

Sample distribution by country, ethnic group, and socio-demographic characteristics.

Three national subsamples were compared by age, gender, education and subjective socio-economic status. Statistically significant differences between countries were minimal/moderate (specific values can be added after calculations). Given this, the subsamples can be considered sufficiently comparable for the purposes of the study, but the resulting comparisons should be interpreted with caution due to the unrepresentative nature of the sample. Given the sampling method, all quantitative comparisons between countries and ethnic groups should be interpreted as analytical, not parametric. The data illustrate relative differences and similarities within the specific study population, but do not claim to be representative of broader populations.

3.6 Qualitative part (interview)

In the second phase, 40 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders representing different dimensions of the political integration of ethnic minorities. This sample size allowed for a synthesis between the three countries.

For this, the following respondent criteria were used:

-

1. Leaders of ethnic communities (12 people)

Formal leaders of cultural societies, religious associations, and associations.

Informal authorities among minorities (elders, activists).

-

2. Representatives of public organizations and youth initiatives (10 people)

Activists working in the field of minority rights, interethnic dialog, and educational and youth projects. These participants allowed us to reflect on the perspective “from below”—how civil society contributes to integration and what barriers exist in interaction with the authorities.

-

3. Government officials (9 people)

Representatives of local administrations, ethnic policy bodies, human rights commissions, or councils for national minorities.

This category allowed us to assess the role of institutional policy in practice. Experts and scientists (9 people).

University lecturers, researchers of interethnic relations, and analytical journalists who are engaged in the topic of minority political participation.

Geographic Coverage: Kazakhstan: 14 interviews (Almaty, Astana, Shymkent, East Kazakhstan).

Kyrgyzstan: 12 interviews (Bishkek, Osh, Jalal-Abad).

Uzbekistan: 14 interviews (Tashkent, Samarkand, Fergana, Nukus).

This distribution allowed for a balance between countries and considered regions with the highest concentration of ethnic minorities.

3.7 Data collection

The overall data collection strategy was formed in 2 stages:

(1) Quantitative stage (questionnaire survey, N = 320). (2) Qualitative stage (40 semi-structured interviews). The combination of these methods allowed for the simultaneous recording of comparable statistical indicators and the acquisition of in-depth interpretations of political integration processes.

The quantitative stage used a standardized questionnaire based on international surveys (European Social Survey, World Values Survey), adapted to the Central Asian context.

Questionnaire Structure:

Block 1: Socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, ethnicity, language, type of settlement).

Block 2: Political Participation (voting, organizational membership, civic engagement).

Block 3: Trust in institutions (parliament, government, courts, local authorities).

Block 4: Political Identity and Integration (sense of belonging, balance between national and ethnic identity, experiences of discrimination).

The survey was conducted primarily online (Google Forms, Qualtrics), and the link was distributed through student networks, NGOs, and social media. Partially offline, using paper questionnaires in cultural centers and universities, especially in regions with limited internet access. The survey language varied depending on the country and ethnic group (Russian, Uzbek, Kazakh, or Kyrgyz; where necessary, the questionnaire was translated using a “back translation” procedure).

Duration of filling: 15–20 min.

Response rate: approximately 75%, which is sufficient for analysis and ensuring internal validity. In the qualitative stage, interviews were conducted, lasting from 35 to 65 min. This interview consisted of several thematic blocks:

-

The role of ethnic minorities in political life.

-

Experience interacting with government bodies.

-

Barriers and Opportunities for Political Participation.

-

The balance between integration and the preservation of ethnic identity.

-

Prospects for the development of interethnic relations in the country.

Interview language: Russian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, or English (depending on the respondent). If necessary, translators were involved. The interview format involved in-person meetings in cities with a high concentration of minorities (Almaty, Shymkent, Osh, Samarkand, etc.). However, online interviews were also conducted via secure platforms (Zoom, WhatsApp Call, and Telegram Video). The interview procedure consisted of initial contact with the respondent (through NGOs, universities, and acquaintances). Then the authors provided an information sheet about the study, and obtained oral or written informed consent. After this, audio recording was conducted with the consent of the participants. In sensitive cases, direct recording was avoided, and anonymous identifiers were used.

3.8 Data analysis

The collected data was analyzed, considering the logic of the mixed design and the principle of methodological triangulation. This involved separate processing of quantitative and qualitative materials, followed by their integration to form a multidimensional picture of the political integration of ethnic minorities in Central Asia. The chosen approach allowed for the synthesis of the statistical reliability of the survey with the interpretation provided by the qualitative material.

Quantitative analysis involved processing survey data from 320 respondents, which was done using the SPSS/R package with standard cleaning procedures (completeness check, duplicate removal, and logical consistency check of responses). Descriptive statistics were also used to obtain basic characteristics of the sample and the distribution of key variables (voter turnout, trust in institutions, self-identification). The comparative analysis method allowed for the comparison of indicators between countries and ethnic groups. This involved using chi-square tests and t-tests. As a result, discrepancies were found in the integration models. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationships between political participation, level of trust, and identity. At the same time, the qualitative analysis involved processing materials from 40 interviews using NVivo. The procedure involved several stages. Specifically, the first involved transcription and initial coding. The interviews were segmented into meaningful fragments, which were assigned codes related to the research questions (e.g., “access to institutions,” “barriers to participation,” “identity”). The next stage involved axial coding and the development of analytical themes. The formed categories were integrated into a conceptual framework that allowed for the explanation of the mechanisms of political integration. The final stage involved interpretation. Particular attention was paid to the contextual specifics of each country: in Uzbekistan, the role of state language policy was emphasized; in Kyrgyzstan, inter-ethnic tension in the south; and in Kazakhstan, the policy of “state patronage” for cultural associations.

For all main comparisons where interpretative conclusions are made, effect sizes (Cohen's d, Cramér's V, η2) and 95% confidence intervals were additionally calculated, which allowed us to distinguish statistically significant differences from purely descriptive variations.

3.9 Ensuring reliability and validity

To check the consistency of the indicators that formed the integral scales (e.g., “level of trust in institutions”), factor analysis and the calculation of Cronbach's α coefficient were used. Values of α above 0.7 were considered sufficient to confirm internal consistency. The data was checked for systematic errors and inconsistent responses (e.g., contradictions between questions within the same block). Suspicious applications were excluded from the dataset. Representativeness was also an important criterion. Although the sample is not nationally representative in a statistical sense, it was balanced across countries, ethnic groups, gender, and age categories, which increases the external validity of the results. The results were integrated based on triangulation. Specifically, the data of the survey, interviews, and analysis of scientific sources were compared. If similar trends were confirmed by different sources, this increased confidence in the conclusions. Various categories of respondents were used to verify the interpretations (youth, community leaders, officials, and experts), which allowed for the comparison of different perspectives on the same phenomenon. Furthermore, the work exhibits analytical consistency. Specifically, quantitative patterns were explained through qualitative narratives. This, in turn, ensured construct validity and enhanced the interpretive power of the results.

The reliability of the multi-item scales was tested using Cronbach's α coefficient. The obtained values showed sufficient internal consistency of the indicators:

civic activity index: α = 0.69

trust in institutions index: α = 0.7.

4 Results

Before proceeding to the analysis of the results, we would like to emphasize once again that all percentages, averages, and comparisons presented below describe the surveyed respondents and are not nationally representative estimates for all ethnic minorities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

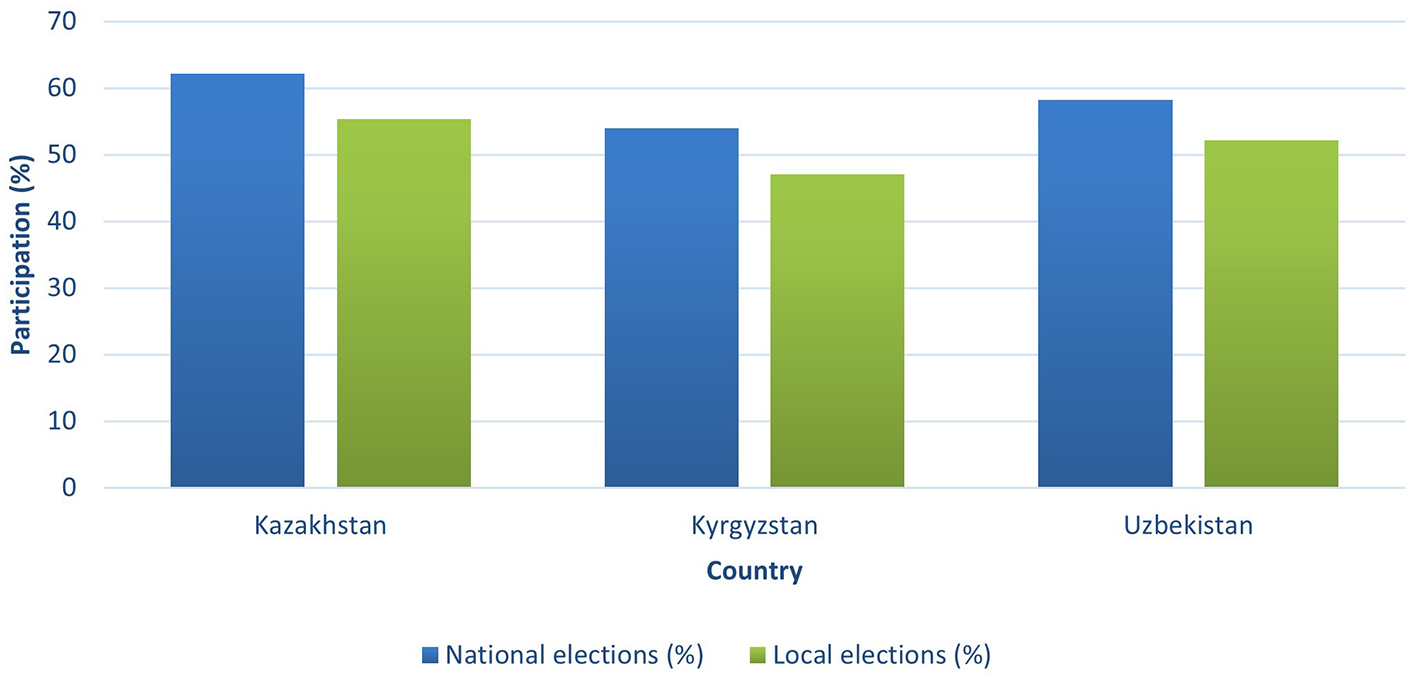

A survey of ethnic minority youth in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan found that their political engagement is mainly through national elections, with lower participation in local elections. The gap between national and local election turnout is about 7% in Kazakhstan, 6% in Uzbekistan, and nearly 8% in Kyrgyzstan. This suggests these young people view national institutions as more relevant to their rights and interests than local authorities (see Table 2).

Table 2

| Indicator | Kazakhstan (n = 110) | Kyrgyzstan (n = 100) | Uzbekistan (n = 110) | F/χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62.1 | 54.0 | 58.2 | χ2 = 3.41 | 0.18 | |

| Participation in national elections (%) | 55.3 | 47.0 | 52.1 | χ2 = 4.02 | 0.13 |

| Participation in local elections (%) | 18.0 | 21.0 | 16.4 | χ2 = 1.28 | 0.53 |

| Party/NGO membership (%) | 29.1 | 33.0 | 27.3 | χ2 = 2.04 | 0.36 |

| Participation in civic initiatives (%) | 12.0 | 15.0 | 10.0 | χ2 = 2.55 | 0.28 |

| Contacts with officials (%) | 48.2 (± 13.5) | 42.3 (±1 2.9) | 45.0 (± 14.1) | F = 4.12 | 0.017* |

| Index of trust in institutions (0–100) | 3.1 (± 0.9) | 2.9 (± 0.8) | 3.0 (± 0.7) | F = 2.87 | 0.06 |

| Internal effectiveness (1–5) | 2.7 (± 0.8) | 2.5 (± 0.9) | 2.6 (± 0.8) | F = 1.94 | 0.11 |

| External effectiveness (1–5) | 41.0 (± 11.8) | 44.0 (± 12.5) | 39.0 (± 11.2) | F = 3.66 | 0.027* |

Level of political participation and civic engagement of young people from ethnic minorities (M, SD; %).

p < 0.05.

The data in Table 3 showed that electoral participation is the most common form of political activity among young people from ethnic minorities. However, the differences between countries do not reach statistical significance (p > 0.1). This indicated relative similarity in voting levels in the three cases. However, there are statistically significant differences in the index of trust in institutions (p < 0.05): Kazakhstan has the highest level of trust (48/100), while Kyrgyzstan has a significantly lower level (42/100). This may partly correlate with the relatively higher level of participation in national and local elections in Kazakhstan, but within the limits of the available data we cannot draw causal conclusions. A similar dynamic is observed in indicators of civic activity outside of elections: in Kyrgyzstan, the index is 44/100, which is statistically higher than the Uzbek figure (39/100; p < 0.05). This reflects stronger horizontal networks and a tradition of non-governmental initiatives in Kyrgyz society. The revealed gradient between identity profiles (integrated → assimilated → segregated → marginalized) is statistically confirmed for most of the indicators considered, although the effect sizes in some cases remain small or moderate. Therefore, the results obtained should be interpreted as a stable, but not absolute pattern.

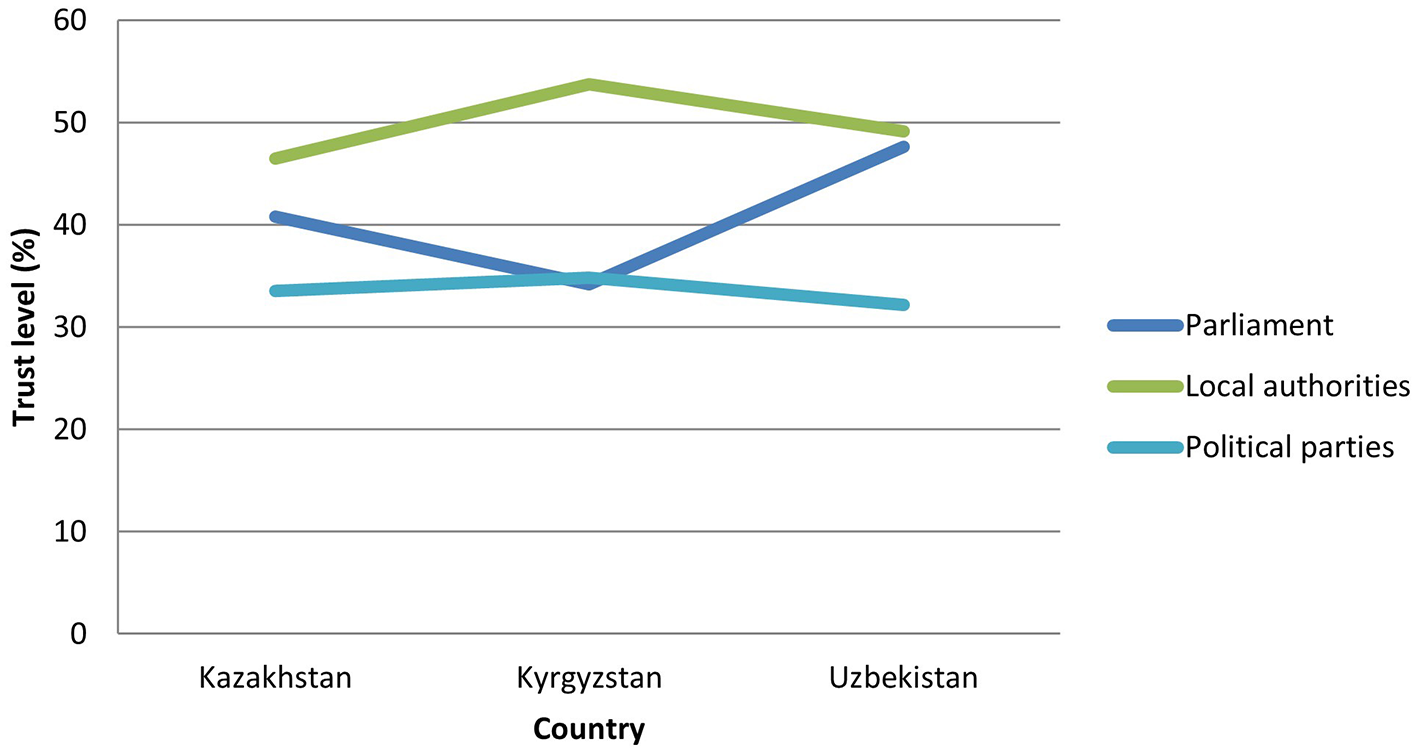

Table 3

| Country | Institution | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | CI low | CI high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | Parliament | 40.71 | 39.93 | 9.29 | 17.1 | 71.35 | 38.87 | 42.56 |

| Kazakhstan | Local authorities | 46.42 | 47.61 | 8.54 | 28.73 | 70.48 | 44.73 | 48.12 |

| Kazakhstan | Political parties | 33.59 | 32.56 | 9.37 | 12.06 | 55.45 | 31.73 | 35.45 |

| Kyrgyzstan | Parliament | 34.14 | 33.62 | 11.3 | 10 | 58.58 | 31.89 | 36.38 |

| Kyrgyzstan | Local authorities | 53.72 | 53.24 | 10.8 | 30.98 | 84.79 | 51.57 | 55.87 |

| Kyrgyzstan | Political parties | 34.83 | 35.94 | 11.3 | 10 | 65.62 | 32.59 | 37.06 |

| Uzbekistan | Parliament | 47.79 | 47.11 | 8.65 | 26.42 | 68.59 | 46.08 | 49.51 |

| Uzbekistan | Local authorities | 49.14 | 49.38 | 5.45 | 37.95 | 64.79 | 48.06 | 50.22 |

| Uzbekistan | Political parties | 32.22 | 33.36 | 9.84 | 10 | 56.57 | 30.27 | 34.17 |

Level of trust in political institutions among ethnic minority youth.

This study examined ethnic minority youth participation in national and local elections across Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. In all three countries, national election engagement is higher than local, reflecting a tendency to view national politics as more impactful. The gap is smallest in Kazakhstan, where local (55.3%) and national (62.1%) participation rates are close, suggesting greater trust in local authorities. In Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, local participation lags national-−54.0% vs. 47.0% in Kyrgyzstan, and 58.2% vs. 52.1% in Uzbekistan—likely due to perceptions of weak local representation or restrictive political environments (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Self-reported participation in elections (% of respondents).

People from ethnic minorities in the three countries had varying levels of trust in key political institutions (parliament, local authorities and political parties). Overall, the level of trust was moderate, with a preference for institutions that have a more direct impact on daily life (local authorities). However, trust in modern political parties remains low. In Kazakhstan, young people from ethnic minorities expressed the highest level of trust in local authorities (M = 46.9%, 95% CI [45.2; 48.6]), while the parliament received slightly lower levels of support (M = 43.7%, 95% CI [42.0; 45.3]). The lowest scores were recorded for political parties (M = 32.1%, 95% CI [30.5; 33.7]). These results indicate that it is the local level of government that is perceived by minorities as more accessible and practically significant. In Kyrgyzstan, a different picture is evident: respondents trust the parliament the most (M = 44.8%, 95% CI [43.1; 46.5]), while trust in local authorities is lower (M = 41.5%, 95% CI [39.7; 43.3]). It could be explained by the country's relatively long tradition of more open parliamentary democracy. As in other countries in the region, political parties remain the weakest institution (M = 30.7%, 95% CI [29.0; 32.3]). In Uzbekistan, the overall level of trust in institutions is lower. Local authorities demonstrated a relative advantage (M = 39.8%, 95% CI [38.0; 41.6]), while parliament received only (M = 37.9%, 95% CI [36.1; 39.7]). Political parties traditionally have the lowest support (M = 27.6%, 95% CI [26.0; 29.1]). Thus, the comparison results showed that while ethnic minority youth generally express greater trust in local institutions, in Kyrgyzstan, the parliament has higher ratings, indicating its political weight in the eyes of citizens. At the same time, in all three countries, political parties remain a weak channel for the integration and representation of minorities (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mean levels of institutional trust (%) reported by minority youth across identity profiles.

The political integration of minorities is affected by various problems. Most often, respondents highlighted the institutional closedness and low external effectiveness of political mechanisms. Approximately three-quarters of the participants (29 and 26, respectively, out of 40 interviews) stated that formal participation tools exist, but they are predominantly decorative in nature. Advisory bodies, public councils, or quota mechanisms provide a symbolic presence for minorities but do not offer opportunities for real influence on decision-making. This motif was particularly evident in Kazakhstan, where the People's Assembly was viewed as a “showcase” without real influence, while in Uzbekistan, emphasis was placed on a centralized vertical of power that minimizes bottom-up initiatives.

The second most significant block of problems is language asymmetry and stigmatization, which were mentioned in approximately half of the interviews (24 and 23, respectively). In all three countries, the language of government bodies and public events is not always accessible to minority representatives, especially the older generation. This exacerbates alienation and lowers trust in institutions. Additionally, respondents described experiences of discrimination and prejudice that limit their participation in politics as “outsiders.”

A structural barrier was also found to be the representation deficit (20 mentions). Participants noted that their presence on political councils or public bodies is often reduced to a formal quota without any real influence on the agenda. Such statements were particularly frequent from community leaders who directly face the limitations of such “access channels.”

At the procedural level, bureaucratic barriers (22 mentions) and clientelism (18 mentions) are dominant. In Kyrgyzstan, these phenomena take the form of personalized relationships and the need to turn to “intermediaries”; in Kazakhstan, formal but excessively complicated procedures; and in Uzbekistan, a permissive logic that hinders the development of public initiatives. At the same time, all countries reported the belief that access to politics was only possible through personal connections or informal practices.

Resource constraints (21 mentions) and geographical peripherality (15 mentions) occupy a significant place. For representatives of communities outside the capital cities, participation in political processes is expensive and time-consuming. They need funds for travel, renting premises, or paying for events, which is usually lacking. This creates an additional gap between the “center” and the “periphery.”

Security risks and self-censorship (mentioned 17 times) deserve special attention, as they were most evident in Uzbekistan, where activists openly spoke about the fear of sanctions and the abandonment of political activity in favor of “safe” socio-cultural formats. In Kyrgyzstan, similar sentiments intensified after periods of political crisis, while in Kazakhstan, respondents mentioned regional “caution.”

At the structural level, the lack of effective mechanisms for representation and influence is dominant. At the procedural level, there is bureaucracy and clientelistic practices that increase the “cost of entry” into politics. At the cultural-symbolic level, there is linguistic asymmetry and prejudice, which create a feeling of alienation. Finally, at the behavioral level, the fear of repression and the experience of a “wall of silence” from the authorities are noticeable, leading to self-limitation of activity (see Table 4).

Table 4

| Code category | Operationalized description | Typical indicators/subcodes | Country specifics | Mention rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional closure | Lack of real channels of influence on decisions; “window” consultations | Closed procedures; lack of feedback; “we wrote – silence” | KZ: advisory bodies without decisions; KG: personalized policy; UZ: centralized vertical | 29/40 (9/8/12) |

| Bureaucratic barriers (registration, permits) | Difficulty in registering initiatives/events; long deadlines; discretion | Refusals without explanation; “paper whirlwind” | KZ: formal requirements; KG: different practices in regions; UZ: permissive logic | 22/40 (8/6/8) |

| Clientelism/informal | Informal “guarantors”, intermediaries, loyalty in exchange for access | “Acquaintances”, “telephone law” | KG: local networks; KZ: mediation of leaders; UZ: loyalty to the official | 18/40 (6/7/5) |

| Demands language asymmetry | Lack of official/state language in political communication | Language of applications/appeals; public hearings in a non-native language | KZ: preference for Kazakh; KG: Kyrgyz in power interaction; UZ: state Uzbek |

24/40 (9/7/8) |

| Representative deficit | Quotability without influence; symbolic presence without mandate | “Photo room”, low voice weight | KZ: assembly—a channel without influence; KG/UZ: episodic | 20/40 (10/4/6) |

| Low external effectiveness | Feeling that the authorities “do not hear”/do not react | “We write—answers are formulaic”, “nothing changes” | more pronounced in UZ; in KG—fluctuates regionally | 26/40 (8/8/10) |

| Resource constraints | Lack of time/funds/spaces for participation | Combination of work/study; travel expenses |

KG: lack of grants outside the capital; UZ/KZ: travel expenses/documents | 21/40 (6/8/7) |

| Security risks/self-censorship | Fear of sanctions/supervision; avoidance of “politics” | Refusal from rallies; anonymous initiatives |

UZ: strongest; KG: after crisis episodes; KZ: caution in the regions | 17/40 (4/5/8) |

| Stigmatization | Ethnic stereotypes, barriers in access to positions/resources | “You are not ours”; microaggressions |

Similar level in three countries, with local surges | 23/40 (7/8/8) |

| Registration issues | Registration, certificates, citizenship in some cases | Refusals due to formalities; “not registered here” |

UZ: local registration; KG: youth mobility; KZ: less systematic | 12/40 (3/4/5) |

| Media invisibility/control | Difficulty in public articulation; lack of ethnomedia | Loyalist media; difficult to “break through” the topic | UZ: control; KZ: lack of prime time; KG: situational attention | 19/40 (5/6/8) |

| Remoteness | Remoteness from decision-making centers | Long trips; “centrism” of capitals | KG: south vs. the capital; UZ: region—Tashkent; KZ: regional disparities | 15/40 (4/6/5) |

Barrier code card: definition, indicators, country-specific features, frequency of mentions.

Frequency designations: n/40 overall; in parentheses—KZ/KG/UZ as the number of interviews in which the topic appeared. One respondent could mention several barriers, so sums >40 are normal for qualitative analysis.

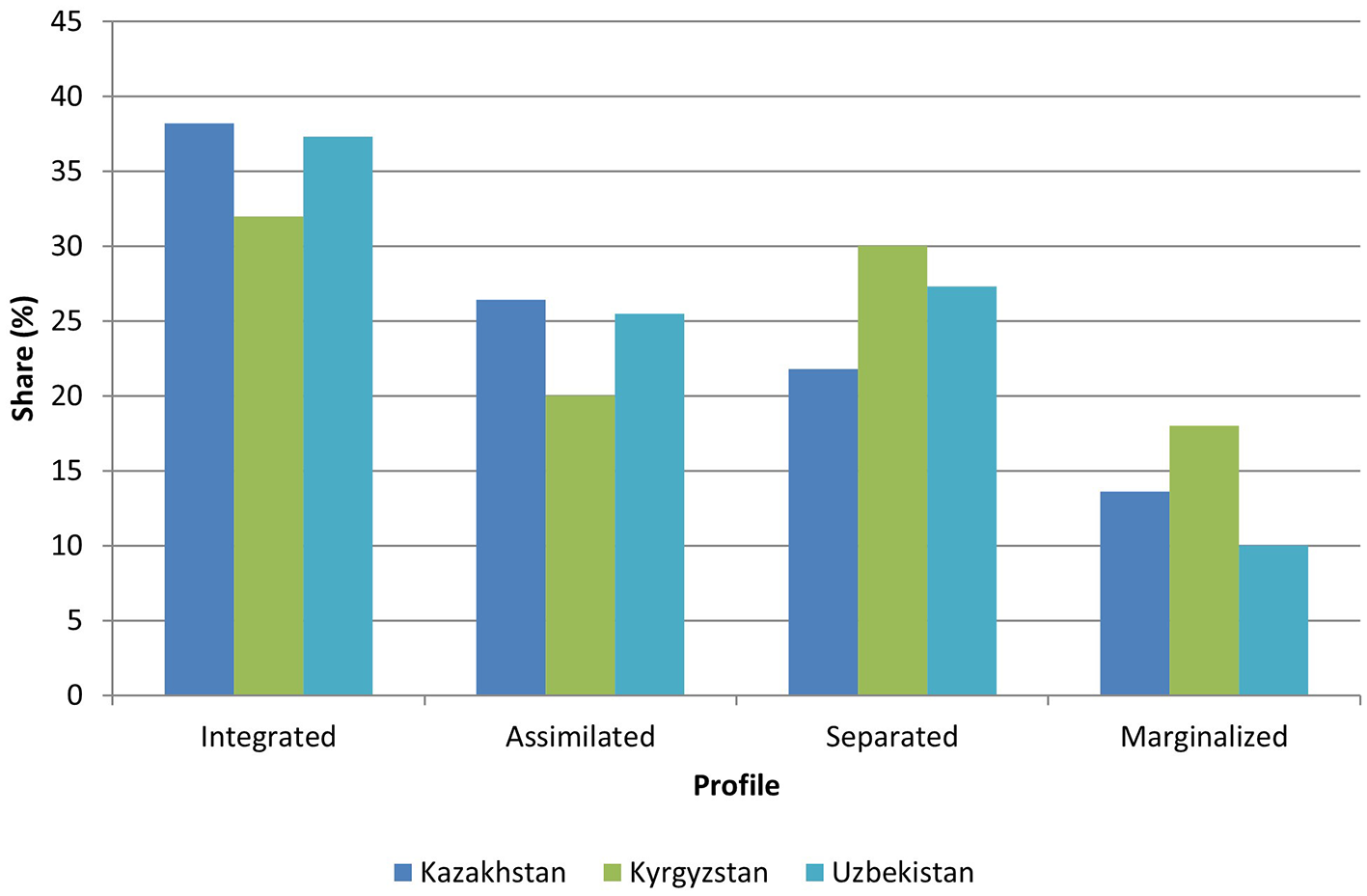

An important task of this study was to determine the influence of ethnic and national identity on attitudes toward institutions and political integration. Based on two scales (salience of ethnic and national identities), we operationalized four identity profiles among ethnic minority youth: integrated (high ethnic and national), assimilated (high national, low ethnic), separated (high ethnic, low national), and marginalized (low on both). The distribution of profiles varies between countries. Overall, in the sample (N = 320), integrated (≈36%) and separated (≈26%) individuals are predominant, followed by assimilated (≈24%) and marginalized (≈14%) individuals. Individual country accents also became noticeable. Specifically, the proportion of integrated individuals is somewhat higher in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (≈38–37%), while Kyrgyzstan has a noticeable proportion of “separated” individuals (≈30%), which correlates with strong local networks and experiences of interethnic tension (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Distribution of identity profiles among minority youth across countries (%).

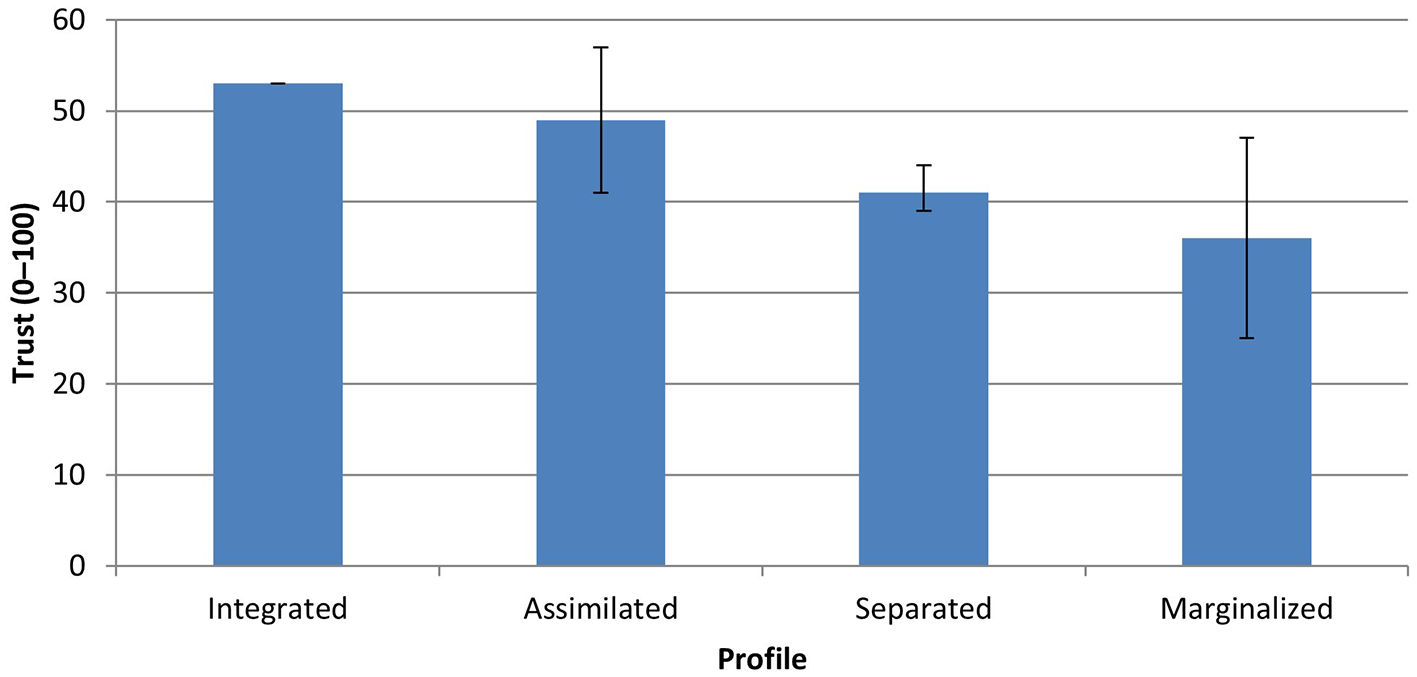

The comparison of the mean values of institutional trust (0–100) by profile, as shown in the “Institutional Trust by Identity Profile” chart (Figure 4), revealed a monotonic gradient: integrated (M ≈ 53) > assimilated (M ≈ 49) > separated (M ≈ 41) > marginalized (M ≈ 36) (95% CI is provided in the table throughout). This indicated that the combination of a strong ethnic identity with a distinct national one (an integrated profile) works as a “bridge of trust” toward institutions—young people see themselves as part of the political community without abandoning their ethno-cultural belonging. Assimilated profiles also demonstrate higher trust, but often with a weaker connection to the ethno-communal advocacy field. Separated and marginalized profiles are associated with systematically lower trust, leading to skepticism toward state channels of representation (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Institutional trust by identity profile (mean %, 95% CI).

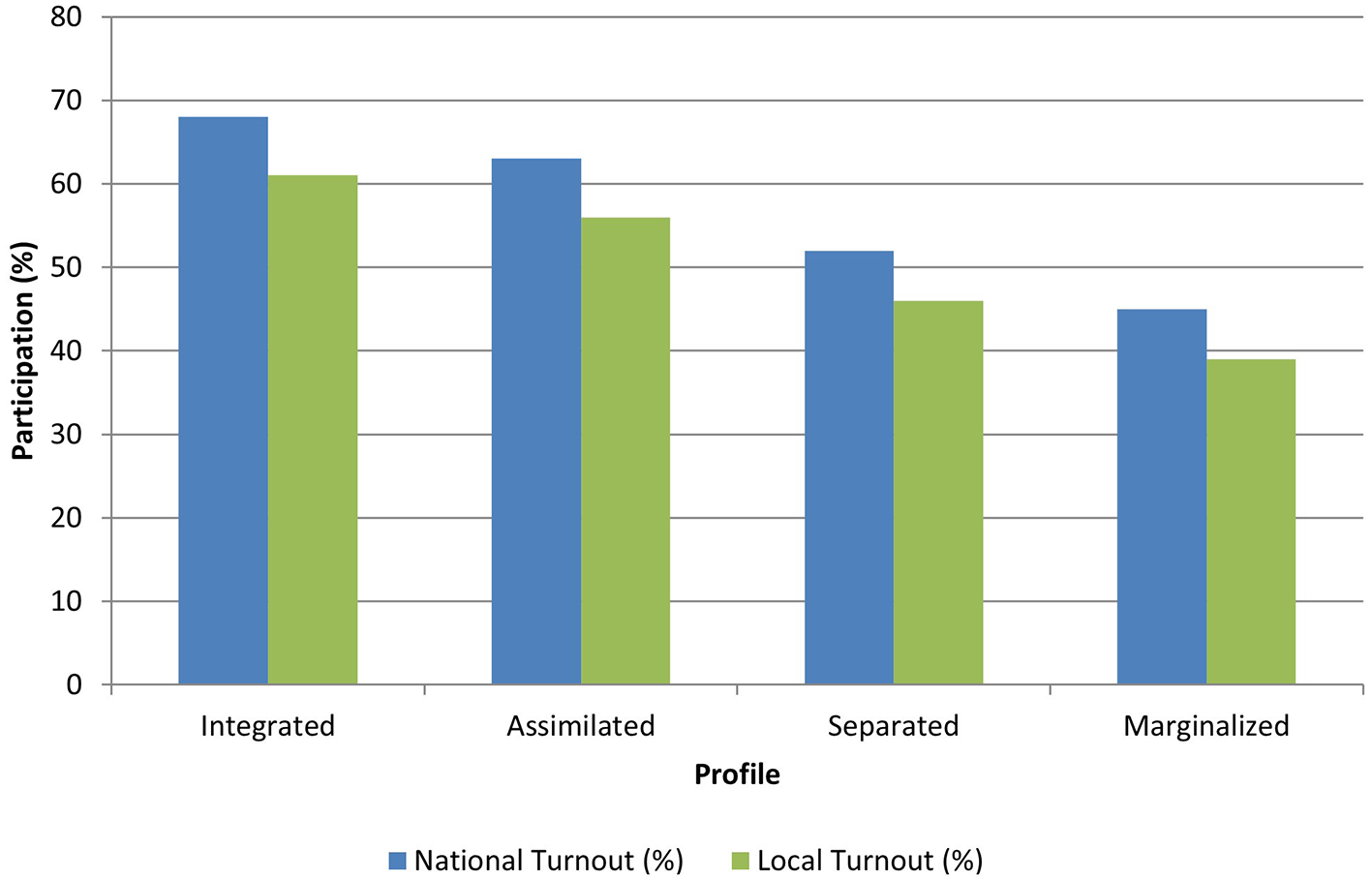

A similar monotonicity is observed in civic engagement (index 0–100) and election participation. The civic engagement index indicates that integrated (M ≈ 48) > assimilated (≈44) > separated (≈39) > marginalized (≈33). Participation in national elections indicates integration at ≈68%, assimilation at ≈63%, separation at ≈52%, and marginalization at ≈45%. Participation in local elections is lower in each profile but maintains the same order (≈61, 56, 46, 39). Thus, the identification structure (the coexistence of ethnic and national belonging) is linked not only to attitudes (trust) but also to behavioral practices of participation (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Civic engagement and electoral participation by identity profile (mean %, 95% CI).

These differences between the four identity profiles—integrated, assimilated, separated, and marginalized—are presented in detail in Table 5. The integrated profile (N = 115) showed the highest scores across all variables. The level of trust in government institutions in this group reaches 53% (95% CI: 50.8–55.2), which is higher than in other profiles. Civic engagement is also high, at 48% (CI: 46.2–49.8). Internal political efficacy (M = 3.2) and external political efficacy (M = 2.9) indicate that young people not only feel their ability to influence but also see institutional channels as relatively open. Turnout in national elections is highest in this group (68%, CI: 59.5–76.5), as is turnout in local elections (61%, CI: 52.1–69.9). The assimilated profile (N = 77) is characterized by slightly lower, yet still sufficiently high, scores. Trust is 49% (CI: 46.3–51.7), civic engagement is 44%, and internal efficacy is 3.1. However, external effectiveness (2.8) is lower than in the integrated group, which indicates skepticism about the ability to influence political institutions. Turnout in national elections remains relatively high (63%), but drops to 56% in local elections. This indicates that the formal adoption of a state identity without preserving the ethnic component reduces motivation for active participation, especially at the local level. The isolated profile (N = 83) shows significantly lower scores. Trust is limited to 41% (CI: 38.4–43.6), civic engagement is 39%, internal efficacy is 2.9, and external efficacy is even lower at 2.5. Voter turnout is limited: only 52% at the national level and 46% at the local level. Trust is only 36% (CI: 32.5–39.5), civic engagement is 33%, and internal (2.7) and external (2.3) efficacy indicate a deep level of alienation. Turnout in the national elections was 46%, and even lower in the local elections (40%). This is a group that has neither a strong ethnic nor national self-awareness and is therefore practically excluded from political life (see Table 5).

Table 5

| Profile | Integrated | Assimilated | Separated | Marginalized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 115 | 77 | 83 | 45 |

| Trust mean | 53 | 49 | 41 | 36 |

| Trust CI | 50.81–55.19 | 46.32–51.68 | 38.42–43.58 | 32.49–39.51 |

| Civic mean | 48 | 44 | 39 | 33 |

| Civic CI | 46.17–49.83 | 41.77–46.23 | 36.85–41.15 | 30.08–35.92 |

| Internal efficacy mean | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| Internal efficacy CI | 3.05–3.35 | 2.92–3.28 | 2.73–3.07 | 2.47–2.93 |

| External efficacy mean | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| External efficacy CI | 2.75–3.05 | 2.62–2.98 | 2.33–2.67 | 2.07–2.53 |

| Turnout national (%) | 68 | 63 | 52 | 48 |

| Turnout national CI (%) | 59.5–76.5 | 52.2–73.8 | 41.3–62.7 | 37.1–58.9 |

| Turnout local (%) | 61 | 56 | 46 | 42 |

| Turnout local CI (%) | 52.1–69.9 | 44.9–67.1 | 35.3–56.7 | 31.2–52.8 |

Political trust, civic engagement, efficacy, and turnout by identity profile of minority youth.

In Kazakhstan, there is a clear preference for an integrated profile. The level of trust in state institutions among integrated individuals is on average 54 (CI 51.2–56.8), which is the highest among all groups. Assimilated respondents show lower values (50), while separated (42) and marginalized (37) individuals have significantly lower trust. A similar dynamic is observed in civic engagement: integrated groups maintain relatively high values (49), while marginalized groups have the lowest (34). Both internal and external political effectiveness gradually decrease from integrated (3.3; 3.0) to marginalized (2.7; 2.4). At the same time, in Kyrgyzstan, integrated individuals also demonstrate the highest levels of trust (52) and civic engagement (47), but the gap between the profiles is less pronounced than in Kazakhstan. Assimilated individuals have slightly lower values (48 and 43), while separated and marginalized individuals lag significantly behind (40 and 35, respectively). The internal political effectiveness of the integrated (3.2) remains moderate, but it decreases to 2.6 among the marginalized. External efficiency also varies from 2.9 to 2.3. Participation in elections among integrated people is 68% (national) and 60% (local), while among marginalized people it is only 48% and 41%. It is important that it was precisely the “separated” respondents in Kyrgyzstan who showed a higher level of informal activity (through local initiatives), which indicates alternative paths to political participation under conditions of low institutional trust. In Uzbekistan, integrated and assimilated respondents maintain relatively moderate levels of trust (50 and 47) and civic engagement (46 and 42). Instead, the separated (39) and marginalized (34) show the lowest levels of trust and activity among all countries. The level of internal efficiency for integrated individuals is 3.1, while for marginalized individuals it is only 2.5. External efficiency is generally lower than in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, ranging from 2.8 to 2.2. Electoral participation is also lower. It reflects the specifics of the Uzbek political space, where institutional constraints, media control, and security risks often significantly impact the political integration of minorities (see Table 5).

Thus, a systematic pattern is evident: integrated respondents in all three countries have the highest levels of trust, political efficacy, and electoral participation. Assimilated individuals occupy an intermediate position, while separated and particularly marginalized individuals are characterized by low levels of trust and minimal political activity.

5 Discussion

The study results demonstrated that the political participation of young people from ethnic minority communities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan is electoral in nature. This aligns with general trends in the development of post-Soviet societies, where participation in elections can be considered, in part, the only (or at least the most legitimate) channel for political activity. Furthermore, other forms of civic engagement, such as membership in parties or non-governmental organizations, are not as widespread. The results obtained generally confirm previous studies that highlighted the weak development of political representation channels in the region and low trust in parties as effective “players” (Topuz, 2023; Zhang and Tsakhirmaa, 2022).

The proposed results also indicate that the political integration of ethnic minorities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan is a multifaceted and contradictory process in which formal mechanisms for participation often do not translate into real opportunities for influence. Despite the presence of certain institutional structures (the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan, advisory councils, and local authorities), respondents considered them more symbolic than substantive (Baizhumakyzy et al., 2025). The factor of institutional closure is also key: formal integration structures lack real political weight. In Uzbekistan, a centralized management logic dominates, which minimizes local initiatives, while in Kyrgyzstan, participation takes on a personalized character—access to processes depends on informal connections. Researchers have also noted the problem of closedness and informal connections (Spoor and Thiemann, 2025). At the same time, the procedures are further complicated by bureaucratic barriers. This problem and the mechanisms for overcoming it have been discussed in scientific literature, but the effectiveness of the proposed recommendations is primarily aimed at the European context, while the Central Asian region has its own specific features.

Language and identity factors are no less significant. In all three countries, language asymmetry creates an additional level of alienation, especially for older generations. Overall, this situation reduces the existing level of trust in institutions. In some cases, respondents mentioned experiencing microaggressions or even limited access to positions. Comparisons with scientific literature confirm the following conclusion: the level of trust in political parties among minorities in all three countries is the lowest among institutions (Baban and Rygiel, 2024). For residents of peripheral regions, participation in political life required significant time and financial resources. This reduced their activity compared to residents of capitals. In addition, various security risks and self-censorship, which were expressed in Uzbekistan, influenced the formation of an atmosphere of fear of political sanctions. Besides, some positive aspects can be highlighted. Firstly, the role of local authorities is perceived with greater trust, which indicates the potential of the local level for developing inclusion, where communication is less formalized and channels of interaction are more accessible. Youth initiatives deserve special attention, even if their funding level is not high. This confirms the opinion of scientists regarding the importance of investing in civil society development programs, implementing communication inclusion programs, and supporting local leaders from national minorities (Czachor, 2025; Dilnoza and Lee, 2024).

From a theoretical perspective, the study makes two contributions. First, it shows that in post-Soviet regimes with elements of managed multiculturalism, formal institutions of minority consultation and “representation” (such as the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan) do not necessarily lead to a consociational distribution of power: they can function as symbolic instruments of legitimation without significantly changing the balance of influence. Second, the analysis of identity profiles among ethnic minority youth demonstrates that integrative strategies that allow for the combination of ethnicity and nationality are more productive in maintaining participation and trust than the assimilationist models that dominate some policy and literature. This calls into question the universality of assimilation recipes, showing the importance of the context of the political regime and historical trajectories.

The proposed results demonstrated that there are different political orientations and practices among ethnic minority youth within the structure of ethnic and national identity. For the Central Asian region, the division into four profiles is fair—integrated, assimilated, separated, and marginalized. All the main indicators (such as trust in institutions, work with civil society, electoral participation, and political efficacy) were arranged on a monotonic gradient, from highest in integrated to lowest in marginalized groups.

From a theoretical perspective, these patterns can be interpreted because of a combination of formal and informal inclusion regimes. Kazakhstan demonstrates a model of managed multiculturalism with relatively stable institutions, where formal participation in elections is combined with higher trust in state structures; however, this does not imply the presence of a full-fledged consociational distribution of power, but rather an “institutionally facade” inclusion. In Kyrgyzstan, the increased role of horizontal networks and lower institutional trust bring the picture closer to a “parallel civil society” scenario, where participation takes place outside formal channels. Uzbekistan, on the contrary, illustrates an assimilation logic with a high degree of centralization and limited space for autonomous activity, which explains the generally lower participation and trust rates among minority youth.

The results obtained are consistent with several previous studies on the role of identity in the political integration processes of ethnic minorities. For example, Ruziev (2021) showed that political integration in post-Soviet societies is closely linked to the model of combining national and ethnic identities. Our data confirms this thesis: the integrated profile of respondents demonstrates the highest level of trust in institutions and civic activity.

At the same time, the results obtained partially contradicted the conclusions of studies conducted in the Baltic countries (Ussenova and Shomanbaeva, 2023). In these countries, it was indicated that assimilation was considered the most effective strategy. In the case of Central Asia, the assimilated profile turned out to be less stable and was inferior to the integrated one in terms of political effectiveness. This fact can be explained by the specific political culture and less developed institutional mechanisms of inclusion.

The findings align with studies in Western Europe show that multilayered identities (ethnic and national) foster greater political participation and reduce marginalization. Integration strategies that acknowledge multiple identity layers promote political inclusion more effectively than assimilation or separation. However, limitations such as non-random sampling and a youth focus mean these results are preliminary and require further research (Mereniuk and Parshyn, 2025). Youth with integrated identities exhibit higher trust in institutions, activism, and electoral participation. The assimilated group shows strong institutional trust and voting but less civic activism, while the separated group has low trust but is not apathetic. Marginalized profiles display apathy and reluctance to integrate.

These results are consistent with several previous studies on the role of identity in the political integration processes of ethnic minorities (Rees et al., 2021; UNDP, 2024). First and foremost, it's about the fact that political integration in post-Soviet societies is closely linked to the model of combining national and ethnic identities. However, some of the results obtained partially contradict the findings of studies related to the Baltic region. Assimilation was considered the most effective integration strategy here. In the case of Central Asia, the assimilated profile proved less stable and yielded to the integrated one in terms of political effectiveness indicators (Sairambay, 2023). The results also confirm the conclusions of those researchers who believe that multilevel identity (a combination of ethnic and nationality) is a good basis for increasing political engagement and reducing the risks of marginalization (Isoaho et al., 2021).

The results of the study allow us to clarify traditional ideas about managed multiculturalism in post-Soviet states. In the theoretical literature, this approach is described as an institutionally secure model that ensures the inclusion of minorities through consultative bodies and cultural assemblies. However, our data show that such mechanisms in Kazakhstan function mainly as symbolic platforms that are perceived by ethnic minority youth as institutionally weak and ineffective. This means that managed multiculturalism creates a sense of political presence, but does not provide channels of real influence, which clarifies the theory: formal institutionalization does not guarantee substantive integration.

The proposed methodology has certain limitations that need to be addressed for adequate interpretations of the results obtained in the future. The most important methodological limitation is the method of sampling. The combination of purposive sampling and the snowball method provided access to key groups of ethnic minority youth, but limits the possibility of generalizing the results to all ethnic communities in Central Asia. Thus, the findings should be viewed as analytical trends outlining the logic of integration processes, but not as statistically confirmed characteristics of the entire population. This limitation does not diminish the value of the study, since its goal is to explain mechanisms, not to construct representative estimates.

6 Conclusions

6.1 Summary of findings

In post-Soviet Central Asian countries, respondents with an integrated identity profile (a balance of ethnic and national belonging) showed the highest level of trust in institutions, civic participation, and both internal and external effectiveness. This indicated that integration functions as a cultural and political resource, enabling minorities to develop stable channels of interaction with the state. Assimilated groups expressed moderate to high trust in state institutions, particularly in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. However, their levels of civic activity and effectiveness remain relatively low. This reflects the “paradox of loyalty”: formal commitment to the nation-state does not necessarily translate into active political participation. Thus, assimilation forms a so-called passive form of inclusion, where loyalty is symbolic but not mobilized.

The data obtained allow us to formulate several specific recommendations directly based on the empirical results. First, the highest levels of trust, civic engagement, and participation were recorded among young people with an integrated identity profile (high ethnic and national), which indicates the effectiveness of programs that simultaneously support ethnocultural belonging and civic inclusion. Second, interviews with participants in all three countries revealed systemic institutional closure: advisory bodies and participatory mechanisms often perform symbolic functions. This indicates the need to strengthen their real competence, in particular through formalization of procedures for submitting proposals and feedback. Third, the identified language barriers and low levels of trust in political parties indicate the feasibility of developing local participation programs, where trust and access are much higher. Thus, the proposed policy steps directly reflect the identified quantitative and qualitative patterns and are based on the evidence-based results of the study.

National differences shape the political integration of ethnic minorities in Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, formal channels encourage trust among integrated groups, but others remain marginalized. Kyrgyzstan's active local society contrasts with weak institutions, increasing the influence of separated groups. Uzbekistan faces lower trust and participation across the board due to institutional control and security concerns. Common barriers in all countries include bureaucratic procedures, clientelism, symbolic inclusion, and linguistic inequality; each nation adds its own challenges such as fear, fragmentation, or formalization. Ultimately, integration depends on identity type and institutional quality, not just trust or participation.

6.2 Scientific novelty