- Center for Asian Studies, National University of San Marcos, Lima, Peru

Introduction: This study examines the effects of China’s rule-of-law reforms and anti-corruption measures under Xi Jinping on economic performance, using China as a benchmark to compare with seven Latin American countries. It aims to explain how different institutional trajectories shape governance quality and long-term growth.

Methods: The analysis draws on two decades of panel data and employs fixed and random effects models with interaction terms to investigate how improvements in corruption control and the rule of law influence economic performance. China is systematically compared with selected Latin American countries to highlight divergent institutional dynamics.

Results: The results show that China’s state-led institutional reforms have strengthened bureaucratic efficiency, policy coordination, and investment conditions, fostering sustained economic expansion. In contrast, Latin America’s fragmented institutions, weak enforcement of legal frameworks, and persistent corruption limit the effectiveness of governance reforms, constraining economic growth.

Discussion: By systematically comparing China and Latin America, this study contributes to comparative political economy by demonstrating how targeted, state-driven institutional reforms can shape governance quality and long-term developmental trajectories.

1 Introduction

Since Xi Jinping assumed leadership in 2012, China has undertaken a sweeping set of institutional reforms aimed at consolidating party discipline, reducing corruption, and reinforcing the rule of law as central pillars of governance. It should be noted that this does not refer to the Western liberal conception of the rule of law, emphasizing judicial independence and individual rights. In the Chinese context, “rule of law” refers to the strengthening of legal and institutional frameworks to ensure governance consistency, policy enforcement, and state accountability within a Party-led system (Peerenboom, 2002; He, 2018). These reforms have been analyzed in depth in recent scholarship, as well as in the present study (Valdiglesias, 2022), highlighting how anti-corruption campaigns and legal restructuring have contributed to institutional capacity, bureaucratic efficiency, and long-term economic stability.

The anti-corruption campaign, led by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) and later complemented by the National Supervisory Commission (NSC) under the Liuzhi system, has sanctioned millions of officials across various administrative levels, including some high-ranking cadres, signaling an unprecedented reach in Chinese governance. However, several scholars (Yuan, 2020; Zhang, 2024; Santos, 2022; Staiano, 2019) note that enforcement remains selective, and not all officials are equally affected, particularly at the very top of the Party hierarchy. Independent media reports also corroborate high-profile cases, such as the investigation of senior officials, demonstrating both the breadth and the political selectivity of the campaign.

These efforts collectively reflect reforms to rebuild institutional credibility, increase bureaucratic efficiency, and foster long-term economic stability. By integrating these developments into a comparative analytical framework, this study situates China’s experience within broader debates on governance and development, offering insights into how comprehensive institutional reforms—anchored in anti-corruption and legal restructuring—can improve state capacity and influence economic outcomes over time.

Although China and Latin America differ in their political regimes, they remain analytically comparable because both represent middle-income contexts where state capacity, institutional quality, and rule-of-law reforms have been central to development debates. Comparing China with high-income economies would obscure these dynamics due to structural gaps in income level, administrative traditions, and historical trajectories. In contrast, Latin America provides a more suitable counterfactual: both regions faced similar challenges—corruption, uneven bureaucratic capacity, and politicized legal institutions—but followed sharply different reform paths. This contrast allows the study to identify how divergent models of state-led institutional reform shape corruption control, rule-of-law strength, and ultimately economic performance.

Recent studies have begun to directly examine the linkages between anti-corruption measures, legal institutionalization, and economic growth. For example, Liu and Liu (2025) analyze how integrity transitions promote economic growth; Bojanic (2014) investigates the effect of coca cultivation and FDI on corruption in Bolivia; Mugellini et al. (2021) assess public sector reforms and their impact on corruption levels; and Shen et al. (2026) explore how anti-corruption shocks and political incentives affect regional economic development. While these studies provide valuable insights, they generally focus on specific regions or mechanisms. This study builds on this literature by integrating anti-corruption campaigns and legal reforms in China and comparing them with Latin American contexts to assess broader patterns of institutional quality and long-term economic growth.

This study examines whether and how China’s anti-corruption measures and legal reforms have strengthened institutional quality to promote long-term economic growth. It contrasts China’s institutional trajectory with that of seven Latin American countries, analyzing how differences in corruption control and rule-of-law enforcement have led to divergent economic outcomes. Beyond this comparative analysis, the paper explores the broader theoretical and policy lessons that China’s experience offers for other emerging economies aiming to enhance institutional quality and achieve sustainable development.

The objective of this study is to analyze the mechanisms through which China’s anti-corruption measures and legal-institutional reforms have shaped long-term economic growth by reinforcing institutional quality. In parallel, the research compares China’s institutional trajectory with Latin American countries, highlighting how differences in corruption control, and the rule of law translate into divergent economic outcomes. Building on this comparative perspective, the study further aims to distill theoretical and policy lessons from China’s experience that can inform strategies to strengthen institutions and promote sustainable growth in other emerging economies.

By systematically comparing China and Latin America, this study contributes to political science and comparative political economy by examining how improvements in anti-corruption policy and the rule of law shape governance effectiveness and long-term economic growth. It develops an integrated conceptual and empirical framework that links institutional coherence, anti-corruption strategies, and legal reforms to sustainable development outcomes. By identifying contrasting institutional trajectories, the study provides practical insights for policymakers seeking to strengthen governance quality and promote stable, long-term growth in emerging economies (Tutuncu and Bayraktar, 2024).

1.1 Theoretical foundations

Institutional theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the link between governance structures and economic outcomes. Following Acemoglu et al. (2001), corruption undermines institutional effectiveness by distorting incentives, weakening rule enforcement, and diverting resources from productive uses. In this view, corruption is not an isolated pathology but a systemic feature of extractive institutions, where political elites exploit public resources for private gain. Such institutional weaknesses increase transaction costs, reduce investor confidence, and ultimately constrain economic growth.

Corruption operates through multiple channels. First, it erodes the rule of law by normalizing informal payments, favoritism, and selective enforcement of regulations. Second, it distorts markets by privileging politically connected actors while discouraging competition and innovation. Third, it undermines public trust in governance, reducing citizens’ willingness to comply with formal rules and fueling cycles of informality and inefficiency. These effects are cumulative: they weaken state capacity, create uncertainty for economic actors, and reduce the effectiveness of policy interventions (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Rose-Ackerman, 1999).

The literature on corruption also highlights contrasting perspectives. Some scholars, particularly within the “grease the wheels” hypothesis, argue that in highly inefficient bureaucracies’ corruption may act as a substitute for poor regulation, allowing firms to bypass cumbersome procedures and accelerate decision-making (Leff, 1964; Méon and Weill, 2010). However, the dominant view in political economy stresses that while corruption may provide short-term relief in rigid institutional settings, in the long run it entrenches inefficiency, reinforces inequality, and deters innovation (Tanzi, 1998; Mauro, 1995). This debate underscores the importance of contextual analysis: the economic consequences of corruption depend on broader institutional configurations, making comparative approaches particularly valuable.

Inclusive institutions, as theorized by North (1990) and expanded by Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), are characterized by accountability, transparency, and broad-based participation in economic and political processes. They secure property rights, enforce contracts, and ensure the predictability of rules—all essential for long-term planning and investment. By contrast, extractive institutions concentrate power and resources in the hands of a narrow elite, facilitating corruption and rent-seeking behaviors that undermine growth. From this perspective, the rule of law emerges as a critical pillar of inclusivity: strong legal systems not only safeguard rights but also constrain arbitrary authority and enhance state legitimacy.

Empirical studies provide further support for these theoretical claims. La Porta et al. (1998) demonstrate that countries with strong legal traditions protecting investor rights exhibit higher growth trajectories. Mauro (1995) finds that corruption reduces investment and growth by introducing uncertainty and inefficiency into economic systems. More recently, Acemoglu et al. (2012) argue that the interaction between political and economic institutions explains divergent development paths: inclusive institutions foster innovation and sustained growth, while extractive ones produce volatility and stagnation.

This literature offers a relevant lens for analyzing institutional capacity improvement. China’s recent anti-corruption campaigns and its broader legal-institutional reforms can be seen as attempts to strengthen institutional capacity, improve accountability, and increase institutional predictability. While these reforms are centralized and state-led, they have targeted critical sectors—such as infrastructure, finance, and technology—where corruption previously generated significant inefficiencies. By contrast, many Latin American countries continue to face weak rule of law, and inconsistent enforcement, which limit the economic growth (Robinson, 2018; Lopez and Alvarez, 2018; Fuentes and Peerally, 2022).

Although China and Latin America have very different political systems—China with a centralized, meritocratic “selectocracy” (Yao, 2018) and Latin American countries with pluralistic and competitive elections (Levitsky and Way, 2010)—a meaningful comparison is possible when focusing on specific governance mechanisms, such as corruption control and rule of law, and their effects on economic growth. China’s reforms have improved state capacity and economic performance, whereas entrenched corruption and limited enforcement constrain growth in Latin America (Evans, 1995; Fukuyama, 2014).

Despite political differences, China and Latin America share institutional and structural commonalities such as challenges in corruption control that allow for meaningful comparative analysis (Staiano, 2019; Miao, 2022; Wong et al., 2020). Both regions rely on development strategies and face similar constraints in promoting accountability. These parallels provide a basis for examining how targeted institutional reforms can influence economic growth, offering insights for policymakers seeking to enhance governance quality and promote stable, long-term growth in emerging economies (Tutuncu and Bayraktar, 2024).

1.2 Institutional and anti-corruption reforms under xi Jinping

Anti-corruption and legal reforms in China are not entirely new phenomena. Since the post-Mao reform era, successive administrations, including those of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, had implemented various mechanisms to address corruption, such as regulatory frameworks, disciplinary procedures within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and limited legal reforms aimed at controlling misconduct in the bureaucracy (정수아, 2021; Yuen, 2014). These earlier efforts, however, were often sporadic, and lacked systematic enforcement across all levels of government. They primarily targeted blatant abuses of office or political rivals, and the institutional capacity to monitor, punish, and prevent corruption remained relatively weak (Yuen, 2014; Chen, 2014).

The Xi Jinping administration, which began in 2012, represents a notable departure from these earlier approaches. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign is characterized by its unprecedented scope and intensity, targeting both high-ranking “tigers” and lower-level “flies,” thereby signaling a commitment to both vertical and horizontal enforcement (Fabre, 2017; Wang and Zeng, 2016). A defining feature of this campaign is the integration of disciplinary measures with formal legal instruments, including the systematic application of Liuzhi detention, administrative sanctions, and criminal investigations (Mushkat and Mushkat, 2020; Valdiglesias, 2024). This represents a clear institutionalization of anti-corruption practices, moving beyond ad hoc or politically selective measures that were more typical of previous regimes (Dong, 2025).

The reforms under Xi also emphasize procedural rigor and consistency. Enforcement is no longer purely discretionary; it follows structured guidelines designed to increase transparency and predictability within the party and government bureaucracy (Ionescu, 2018). At the same time, the campaign strengthens internal accountability by embedding anti-corruption norms directly into party governance, thereby enhancing institutional quality and reinforcing the legal and political framework of China’s state apparatus (Dong, 2025; Brown, 2018).

It is important to note, however, that the campaign serves multiple purposes. While it contributes to stronger institutional oversight, it also consolidates political stability by targeting officials who may resist policy directives, creating a dual effect of reform and political control (Chen, 2014; Yuen, 2014). Nevertheless, when compared to many Latin American countries and other regions of the world, where anti-corruption enforcement tends to be sporadic, or heavily politicized, Xi’s approach is distinctly systematic and institutionally embedded. This distinction underscores why China’s control of corruption has improved in parallel with the campaign, providing a more solid foundation for economic growth and policy implementation (Yuen, 2014; Brown, 2018).

1.3 Literature review and hypothesis

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has implemented a series of institutional reforms aimed at consolidating CCP control while enhancing technological capacity and economic resilience. Scholars largely agree that these reforms reflect a deliberate recalibration of the Chinese political economy toward improved state institutional quality (Zhao, 2022; Fiol-Mahon, 2018). Goldstein (2020) emphasizes that Xi’s institutionalization project prioritizes policy coherence and bureaucratic efficiency, reflecting a dual strategy of elite consolidation and targeted institutional disciplining. Yuan (2020) similarly argues that these reforms sought to dismantle entrenched patronage networks, whereas Zhang (2024) highlights the selective enforcement that improves bureaucratic transparency and efficiency but preserves elite power. Li (2020) frames anti-corruption campaigns as simultaneously enhancing legitimacy and economic coordination.

However, these interpretations raise critical questions about the trade-offs inherent in China’s model. While Staiano (2019) and Fiol-Mahon (2018) note that clearer legal frameworks reduce regulatory uncertainty and facilitate high-tech economic activity, Santos (2022) and Zhao (2022) point out that progress in the rule of law is partial and asymmetrical, favoring actors aligned with state priorities. This tension suggests that institutional improvements may not uniformly translate into broad-based economic benefits, a nuance often overlooked in the literature.

China’s reforms are closely linked to its broader economic transformation toward technological innovation and domestic consumption. Scholars highlight CCP strategies targeting AI, 5G, and green technologies as part of endogenous innovation efforts (Santos, 2022; Zhang, 2024). Zheng (2025) notes that these initiatives also serve as buffers against external shocks, including trade conflicts. Nevertheless, critiques underscore persistent inefficiencies, particularly related to preferential treatment of SOEs (Fiol-Mahon, 2018; Fan et al., 2019), highlighting the tension between political control and market efficiency. Redistributive policies, such as social welfare expansion, simultaneously enhance legitimacy while reinforcing state-led developmental strategies (Chen, 2017; Li, 2020). This ambivalence points to a key theoretical question: to what extent can institutional strengthening coexist with elite-preserving governance without generating inefficiencies?

In contrast, Latin American countries face enduring challenges of corruption and weak rule of law. Robinson (2018) argues that discontinuities in governance undermine investment and innovation, while Ceobanu (2019) and Lopez and Alvarez (2018) link structural institutional weaknesses to the region’s reliance on low-complexity, resource-based exports. Empirical evidence reinforces this divergence: Topolewski (2025) finds that institutional reforms in Latin America yield only modest growth effects, while Panzabekova et al. (2024) associate corruption with chronic underinvestment and public service deficiencies. Ahmed et al. (2025) further show that pervasive corruption systematically undermines economic growth. These findings collectively indicate that, unlike China’s targeted and coherent reforms, Latin American efforts often fail due to fragmented enforcement, weak institutional capacity, and the persistence of informal economies (Bermúdez et al., 2024; Mamo et al., 2024).

The literature also identifies potential avenues for institutional improvement. De Almeida et al. (2024) and Shamugia (2025) demonstrate that better governance is positively correlated with higher growth, while Onafowora and Owoye (2024) stress the importance of regulatory coherence for sustaining these gains. Yet, the literature remains limited in explaining why institutional reforms succeed in some contexts (e.g., China) but not others (e.g., Latin America), leaving a critical gap this study aims to address. Xu (2025) and Fang et al. (2025) provide a nuanced perspective on China, showing that anti-corruption campaigns can reallocate informal rents and shape public perceptions, highlighting the complex interplay between performance legitimacy, institutional reform, and economic outcomes.

Finally, the global dimension of China’s reforms, exemplified by initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (Nedopil, 2023), suggests that institutional effectiveness extends beyond domestic policy, influencing trade and infrastructure development internationally. Acemoglu (2025) frames China’s model as extractive yet effective in driving economic upgrading, contrasting sharply with Latin America, where normative commitments to participatory governance often falter due to weak enforcement and fragmented institutions. This contrast underscores the central research puzzle: how differences in institutional coherence, rule enforcement, and elite strategies shape divergent growth trajectories across emerging economies.

This study hypothesizes that China’s institutional reforms under Xi Jinping—particularly the implementation of rigorous anti-corruption campaigns and the strengthening of the rule of law—have substantially enhanced institutional quality, thereby promoting long-term economic growth through more efficient resource allocation, higher investment, and greater policy predictability. In contrast, persistent corruption and weak rule-of-law enforcement in Latin America continue to undermine institutional effectiveness, limiting sustainable economic performance. These divergent institutional trajectories underscore the critical role of governance capacity in shaping economic outcomes and highlight the importance of coherent and enforceable institutions for achieving durable development in emerging economies.

2 Method

Building on the theoretical foundations, this study adopts a comparative, empirical approach to examine how corruption control and rule of law influence economic growth. To ensure comparability among variables, for the regression, the GDP is the indicator for economic growth. Although China and Latin America differ politically, focusing on these governance mechanisms allows for meaningful comparison while accounting for differences in enforcement capacity and institutional structure. This alignment ensures coherence between theoretical foundations and empirical design.

2.1 Research design

The methodological strategy is structured around two analytical modules. The first examines the impact of Corruption Control on GDP: Examining associations between variations in anti-corruption measures and GDP across different governance contexts. The second focuses on the influence of Rule of Law on Economic Outcomes: Assessing how variations in the quality of legal institutions are associated with economic performance.

Both Control of Corruption and Rule of Law are treated as primary measures of governance, explicitly analyzed as independent variables. GDP is included as the dependent indicator of economic performance. By modeling governance indicators separately, the analysis captures the potentially independent and context-dependent relationships between institutional quality and economic outcomes, ensuring that both dimensions—governance and economic performance—are systematically evaluated assessed within the model.

2.2 Sample selection

The study focuses on China as benchmarking and seven representative Latin American economies: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. These countries were selected to maximize cross-sectional variation in institutional quality, governance structures, and economic performance. Economic and governance indicators are drawn from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), providing reliable, comparable, and validated measures. Moreover, anti-corruption enforcement in China (2018–2024) was measured using official CCDI data on investigations.

2.3 Data structure and variables

The empirical analysis relies on a 20-year country-level panel dataset (2003–2022), which is appropriate for the study’s objective of assessing nationwide institutional reforms rather than their intra-country implementation. Because corruption control and rule-of-law frameworks in both China and Latin America are designed and enforced primarily at the central government level, country-level indicators capture the relevant institutional shifts that motivate this comparison. While recognizing subnational heterogeneity, the focus here is on macro-institutional trajectories and their aggregate economic effects. Variables are operationalized as follows:

• Dependent Variable (EGit): Annual GDP of country i at time t.

• Independent Variables:

• Control of Corruption: WGI index measuring effectiveness of anti-corruption policies.

• Rule of Law: WGI index assessing trust in societal rules, contract enforcement, property rights protection, and judicial quality.

• Dummy: Region-specific interactions (DummyLatamVariable) is included to contrast Latin American relationships between institutional quality and economic outcomes with China, which serves as the benchmarking reference.

• Interaction Terms: DummyLatamxControlofCorruption/DummyChinax ControlofCorruption. These interaction terms evaluate whether the impact of corruption on growth depends on the regional context.

• Control Variables (CVit): Capital formation, labor force, etc.

2.4 Econometric strategy

To rigorously examine these associations, the study applies Random Effects (RE) panel data models (Equations 1 and 2), which allow for both within- and between-country variation while assuming no correlation between unobserved effects and explanatory variables. Model selection was guided by the Hausman (1978) test, which indicated that the RE specification is the most appropriate and efficient for this dataset.

Equations:

Control of corruption:

Rule of law:

In our panel models, China serves as the benchmark, with the intercept reflecting expected economic performance in China, while the Latin America dummy captures baseline differences relative to China. Interaction terms (Latin America × Control of Corruption, Latin America × Rule of Law) capture the additional, region-specific effects of governance variables on economic performance, highlighting how these institutional factors operate differently in Latin America compared to China.

Robustness and sensitivity checks—including FE and RE model comparisons, diagnostics for multicollinearity, heteroskedasticity, and autocorrelation, as well as subsample analyses by region and governance level—ensure empirical rigor and the reliability of observed associations without implying direct causality, while also verifying that the observed effects of governance and institutional quality are consistent across different model specifications, samples, and regional contexts.

By embedding these interactions and using panel methods with time and country fixed effects, the methodology aligns empirical analysis with theory, testing whether China’s institutional reforms are associated with higher economic performance, whether persistent institutional weaknesses in Latin America limit growth, and whether differences in institutional effectiveness explain regional variations, emphasizing the conditional and context-dependent nature of governance on development outcomes.

To determine the most appropriate estimation strategy, both fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models were initially estimated. A Hausman (1978) test indicated that the random effects specification is more suitable for this panel dataset, as it provides consistent and efficient estimates while capturing both within- and between-country variation. Accordingly, the RE model is presented as the main analysis, while the FE results are included in the Supplementary Material for robustness checks, ensuring transparency without overloading the main text.

3 Results

Figure 1 shows GDP growth patterns for seven Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, based on data from the World Bank (2024). Argentina’s growth has been highly volatile, with strong expansions between 2003 and 2007 (average above 9%) and sharp contractions in the 1980s and early 2000s. Brazil experienced growth in the early 2000s, largely supported by resource exports, followed by recessions in 2015–2016. Chile’s growth has been relatively stable, particularly during the 1990s and 2000s, but slowed after 2014, reflecting challenges in reducing reliance on mineral exports.

Figure 1. Real GDP growth of selected Latin American countries. Prepared with data taken from World Development Indicators (2024), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

Colombia, Mexico, and Peru display alternating periods of expansion and contraction, influenced by external shocks, domestic policy, and structural factors. Venezuela exhibits extreme volatility, with growth during oil booms and severe contractions amid political and economic crises. These patterns highlight differences in economic resilience across countries, suggesting potential links to governance indicators.

Figure 2 illustrates China’s remarkable economic growth over the past decades, with sustained high rates following market reforms in the late 1970s. From 1980 to 2023, China consistently outperformed most Latin American countries, achieving double-digit growth on several occasions during the 1980s and 1990s. This performance reflects the effects of economic liberalization, large-scale infrastructure development, industrialization, export-led growth, and more recently, investment in innovation and technology. China’s long-term high growth has helped the country avoid the “middle-income trap” that many Latin American countries face, which occurs when growth slows after reaching middle-income levels due to structural challenges such as low innovation, lack of diversification, and inadequate education systems.

Figure 2. Real GDP growth of China. Prepared with data taken from World Development Indicators (2024), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

The consistent and high economic growth of China is a key factor that may help it escape the “middle-income trap” that many Latin American countries are struggling with. The “middle-income trap” refers to the phenomenon in which a country experiences rapid economic growth, but after reaching middle-income levels, growth stagnates due to structural challenges such as low innovation, lack of diversification, and inadequate education systems. While many Latin American countries have faced stagnation after reaching middle-income status, China has continuously reformed its economy, transitioning from low-cost manufacturing to more advanced, technology-driven sectors. Additionally, China has heavily invested in infrastructure and innovation, allowing it to remain competitive on a global scale.

3.1 The impact of control of corruption on economic growth

Figure 3 shows China’s steady improvement in controlling corruption, with a score of 55.19 in 2023. Higher values of this indicator denote better control of corruption (range: 0 = weak control, 100 = strong control). These governance gains have supported sustained economic growth by fostering a favorable business environment, attracting foreign investment, and enhancing productivity. In contrast, many Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, continue to face higher corruption levels, which coincide with volatile growth. Chile performs relatively better, but China’s consistent anti-corruption efforts have been a key factor in its long-term economic stability.

Figure 3. Performance of the control of corruption of China and selected Latin American countries. Higher values indicate better control of corruption (0 = weak control, 100 = strong control). Prepared with data from World Development Indicators (2024), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

In Table 1, the control of corruption variable shows positive and statistically significant coefficients (0.019 for the Latam dummy), indicating that better corruption control is associated with higher economic performance in both regions. The small standard errors and high t-statistics confirm that this relationship is statistically significant in the random effects model. The positive coefficient highlights a strong link between improved governance and higher economic performance, suggesting that reducing corruption can foster a more conducive environment for sustainable development.

Interactions of the Latam and China dummies with control of corruption are also positive and significant, showing that both regions benefit similarly from improved governance. However, the Latam dummy itself has a negative coefficient (−26.17), reflecting structural, economic, and political challenges in Latin America compared to China, rather than an inherent limit to economic development.

3.2 The impact of rule of law on economic growth

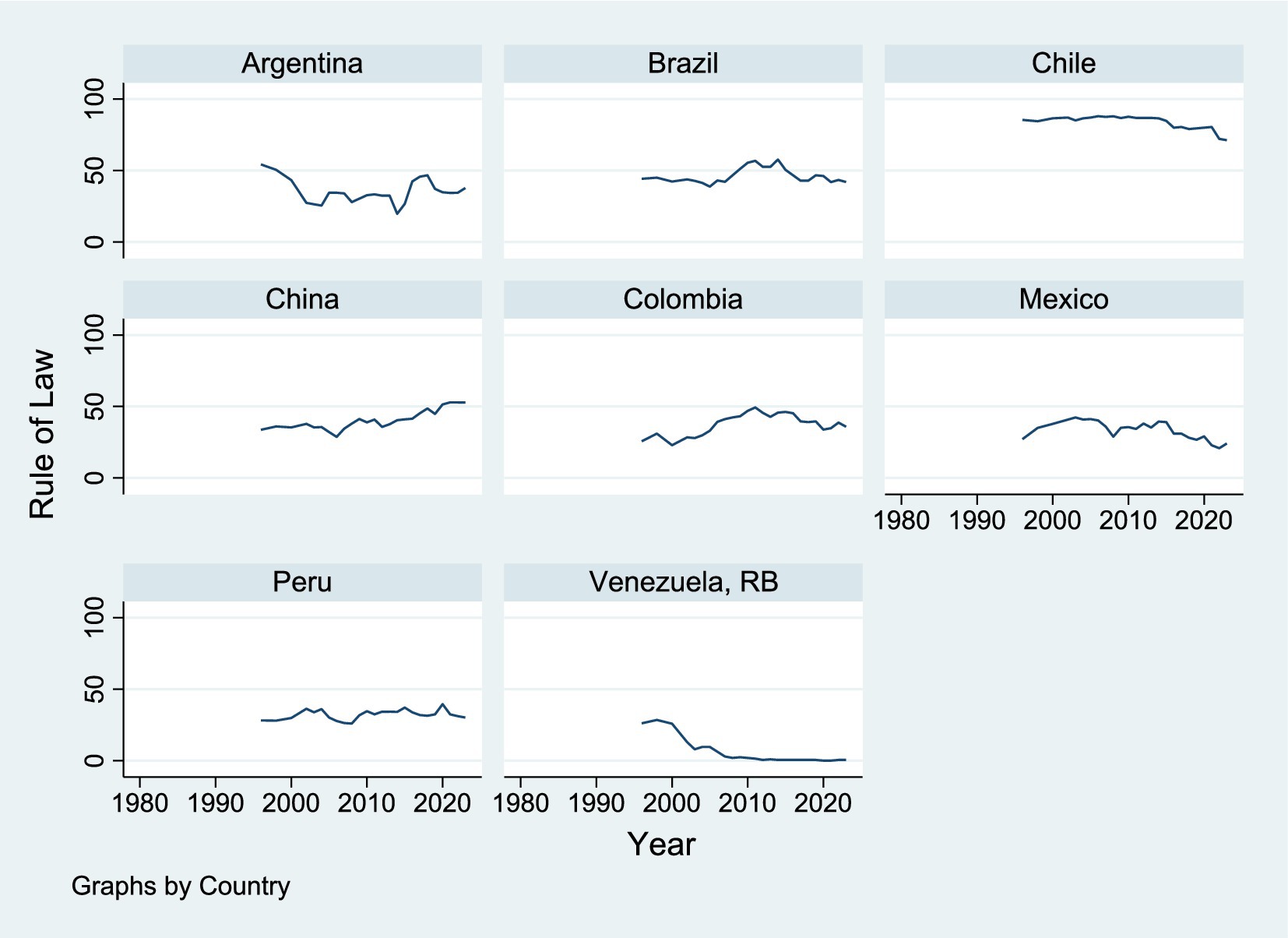

In Figure 4, China’s steady improvement in the Rule of Law, with a score of 52.83 in 2023, has supported its economic growth by providing a more stable legal environment that fosters investment, innovation, and industrialization. Higher values of this indicator denote stronger adherence to the Rule of Law (range: 0 = weak, 100 = strong). In contrast, many Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, face significant challenges in this area, with fluctuating or low Rule of Law scores that hinder investor confidence and economic stability. While Chile performs relatively better in terms of legal frameworks, it still faces limitations compared to China’s robust legal infrastructure. Indeed, China’s stronger legal environment has played a crucial role in sustaining its rapid economic expansion, while Latin American countries need to improve their legal systems to achieve similar growth.

Figure 4. Performance of the rule of law of China and selected Latin American countries. Higher values indicate stronger rule of law (0 = weak, 100 = strong). Prepared with data from World Development Indicators (2024), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

In Table 2, the Rule of Law variable has a positive coefficient of 0.008 in the Dummy Latam model. However, this coefficient is not statistically significant, as the standard error is relatively large (0.009). This suggests that, within this random effects model, the relationship between the quality of legal enforcement and economic performance is not a strong determinant in the sample used. As previously noted, in the short term, economies may experience slowdowns due to reforms aimed at achieving long-term development. While improving the Rule of Law enhances institutional quality, such reforms often require time to take full effect.

Initially, as legal frameworks are strengthened and institutional changes are implemented, businesses and markets may face adjustments that temporarily hinder growth. These challenges are generally viewed as necessary trade-offs to ensure a more sustainable and stable economic environment in the future. Therefore, although the Rule of Law might not immediately drive economic growth, its long-term benefits can outweigh short-term disruptions, fostering a more robust economic foundation.

In China, improvements in the Rule of Law primarily aim to strengthen institutions. Legal reforms are framed as efforts to improve governance and justice, while simultaneously centralizing power through legal structures to ensure greater control over economic processes, supporting long-term stability and development. These reforms are strategically designed to maintain control while promoting economic development, with legal advancements often serving as a tool to reinforce the party’s legitimacy and secure its leadership in the face of domestic and international challenges.

Regarding the Latam dummy, it shows a negative and significant coefficient of −30.5, indicating that, after controlling for other factors, economic development in Latin America is substantially lower than in China, which serves as the benchmark. This difference reflects institutional challenges in Latin America, including weaknesses that limit the effectiveness of reforms such as strengthening the Rule of Law. The magnitude underscores the significant barriers Latin America faces in achieving sustained economic development.

These institutional shortcomings hinder the implementation of effective reforms. While the Rule of Law is critical for fostering a predictable environment—ensuring property rights, enforcing contracts, and minimizing corruption—many Latin American countries lack strong and reliable legal frameworks. This creates uncertainty that deters both domestic and foreign investment and constrains economic dynamism.

China’s development strategy relies on a strong state role in directing economic activity, providing incentives for growth, and investing in infrastructure and innovation. Legal and institutional reforms focus on creating a stable environment for economic development, securing property rights, enhancing business regulations, and improving contract enforcement, thereby fostering confidence in the economy. In this context, China functions as a benchmark, illustrating how coordinated state-led reforms can drive sustained development.

The interaction between Latin America and Rule of Law has a negative but small coefficient (−6.00e−03), indicating that improvements in the Rule of Law in the region have not translated into significant economic gains in this model. This may reflect the complex environment in which institutional reforms operate, where corruption, inequality, and inadequate infrastructure counteract potential benefits.

For China, the interaction of Rule of Law is positive but not statistically significant, suggesting that economic development has been driven more by strategic state-led policies and structural reforms than by strict enforcement of legal frameworks. China’s approach demonstrates that robust economic performance can coexist with a unique institutional and legal design, emphasizing the conditional and context-dependent effects of governance on development.

As noted, China’s reforms in the Rule of Law aim to strengthen institutions. Although these reforms may temporarily constrain economic development due to short-term adjustments, they are designed to enhance institutional quality over the long term. By consolidating state capacity, improving governance structures, and establishing a predictable legal and regulatory framework, these measures create a robust institutional foundation that supports sustained economic expansion and long-term development.

3.3 Complementary overview: anti-corruption measures in China

In addition to the governance indicators discussed earlier, it is useful to complement the analysis with official data on anti-corruption measures conducted by the disciplinary organs of the CCP. Table 3 presents a summary of the number of investigations, punishments, and detention cases (liuzhi) from 2018 to 2024. The table also includes four categories of disciplinary measures, ranging from minor misconduct to serious criminal cases, providing a detailed overview of the CCP’s enforcement activities over this period.

Notably, China has significantly increased the intensity of its anti-corruption measures in recent years, with rising numbers of investigations, punishments, and detentions. This trend highlights the growing rigor and institutionalization of the CCP’s anti-corruption campaign. In contrast, many Latin American countries and other regions of the world continue to rely primarily on perception-based indicators, and anti-corruption enforcement tends to be less systematic. This difference underscores the distinct state-led approach adopted in China compared to other regions.

Importantly, governance indicators such as corruption control are analyzed in detail alongside economic growth, providing a nuanced view of institutional effectiveness. While these governance measures are treated as exogenous variables in the empirical models, their variation is carefully examined to capture both the intensity and scope of anti-corruption efforts, particularly in China. This approach allows for a richer understanding of how institutional quality interacts with economic performance, highlighting the contrast between systematic, state-led enforcement in China and the often perception-based measures observed in Latin America.

4 Discussion

The findings broadly reinforce existing scholarship while offering new comparative insights into how institutional reforms shape economic performance in China and Latin America. Similar to Zhao (2022) and Fiol-Mahon (2018), the results confirm that China has achieved notable institutional improvements, particularly in strengthening its legal framework and reducing corruption. When contrasted with the weaker institutional performance of Latin American countries, China’s systematic and state-led reforms stand out as key drivers of its sustained economic growth. By directly comparing these trajectories, this study advances the literature by empirically evaluating how governance capabilities condition economic outcomes across different political contexts—a central contribution of this paper.

Consistent with Goldstein (2020), our findings underscore that China’s anti-corruption strategy has emphasized institutionalization within the CCP as a foundational step before broader governance reforms. This sequencing, which prioritizes internal discipline and bureaucratic stability, emerges in our results as a critical mechanism supporting long-term economic expansion. By embedding these dynamics within a comparative framework, our study contributes to debates on state capacity by showing how China’s experience may serve—at least partially—as an institutional benchmark for developing countries, particularly in Latin America where enforcement capacity remains limited.

Our results also correspond with Yuan (2020) and Zhang (2024), particularly regarding the short-term effects of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. While earlier studies highlight mixed economic impacts in the short run, our analysis demonstrates that these reforms build crucial foundations for transparency and efficiency within the bureaucracy. These findings strengthen the theoretical claim that the sequencing of institutional reforms—beginning with discipline and anti-corruption—can reinforce administrative efficiency and foster long-term, innovation-driven economic growth.

In line with Santos (2022) and Zhao (2022), the study confirms that improvements in the rule of law may not immediately translate into measurable growth effects. The gradual nature of legal institutionalization explains this temporal lag. However, our analysis reinforces the argument that a predictable legal environment remains essential for long-term investment, innovation, and productivity. By linking rule-of-law reforms to developmental trajectories, the study contributes to the literature connecting institutional quality not only to short-term governance outcomes but to broader structural transformations.

Our results also resonate with Robinson (2018), particularly regarding Latin America’s persistent institutional weaknesses. Deficiencies in corruption control, legal enforcement, and political stability constrain the region’s capacity for sustained economic growth. Despite recurrent reform attempts, weak enforcement and institutional fragmentation undermine efforts to build stable, transparent governing systems. These comparative findings emphasize that China’s success depends not only on policy design but on institutional coherence—something many Latin American democracies struggle to maintain.

This study confirms key insights from Fiol-Mahon (2018), Goldstein (2020), Yuan (2020), Zhang (2024), Santos (2022), Zhao (2022), and Robinson (2018), while extending the literature in three meaningful ways. First, it integrates separate debates on corruption, legal reforms, and economic performance into a single comparative framework. Second, it introduces a dynamic, long-term perspective on institutional reform by analyzing how anticorruption and rule-of-law improvements cumulatively affect growth. Third, it provides empirical evidence supporting the theoretical argument that institutional coherence and enforcement capacity—not merely the presence of formal reforms—determine whether governance improvements translate into sustained development.

These findings have relevant implications for policymakers. The Chinese case illustrates that the effectiveness of anti-corruption reforms depends not only on legal changes but also on enforcement consistency, bureaucratic discipline, and political commitment. In Latin America, persistent institutional fragmentation weakens the credibility and sustainability of reforms, reducing their economic impact. Improving governance thus requires strengthening monitoring mechanisms, depoliticizing enforcement agencies, and ensuring predictable rule-of-law frameworks. Socially, enhanced transparency and legal stability can increase citizen trust, reduce inequality, and promote a more inclusive developmental model.

This study has several limitations. First, the econometric specification relies on a basic Solow-type growth framework, which restricts the inclusion of a broader set of macroeconomic controls. As a result, standard variables such as interest rates, inflation, unemployment, population growth, trade openness, or political indicators are not incorporated, which may lead to omitted-variable bias. Second, the analysis uses official Chinese data to approximate anti-corruption efforts; however, these figures may contain biases due to the limited transparency and lack of independent verification in China.

Future studies should expand the country sample to include other emerging economies and incorporate additional governance dimensions such as political stability, bureaucratic quality, education, and public health. Further research could also explore the long-term institutional effects of anticorruption reforms in transitioning regimes, offering deeper insights into how governance transformations shape sustainable development.

China’s governance model represents an alternative path to development, distinct from the democratic pluralistic model common in much of the developing world. Its centralized, state-led approach has produced notable institutional improvements and sustained economic growth, raising questions about whether authoritarianism can foster stability and development. For countries with fragmented institutions, weak rule of law, or inconsistent policy enforcement, China’s experience offers valuable insights into the trade-offs between political structure and effective governance, highlighting that alternative models may be worth considering when conventional approaches fail to deliver sustainable outcomes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Peru, under its institu-tional research support program: R.R. N.° 005446-2025-R/UNMSM and Project number D25123681 – Project type: PCONFIGI, 2025.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1718532/full#supplementary-material

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown Business.

Acemoglu, Daron. (2025). Institutions, technology and prosperity. NBER Working Paper No. w33442, Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5130534

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 91, 1369–1401. doi: 10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J., and Thaicharoen, Y. (2012). Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: Volatility, crises and growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 49–123. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00208-8

Ahmed, M. Y., Abdullahi, A. M., and Hussein, H. A. (2025). The dual impact of corruption: how perceptions and experiences shape political participation in Somalia – an empirical study. Cogent Soc. Sci. 11. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2025.2504130

Bermúdez, P., Verástegui, L., Nolazco, J. L., and Urbina, D. U. (2024). Effects of corruption and informality on economic growth through productivity. Economies 12:268. doi: 10.3390/economies12100268

Bojanic, A. (2014). The effect of coca and FDI on the level of corruption in Bolivia. J. Inst. Econ. 10, 123–145. doi: 10.1007/s40503-014-0011-5

Brown, K. (2018). The anti-corruption struggle in xi Jinping's China: an alternative political narrative. Asian Aff. 49, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/03068374.2018.1416008

Ceobanu, A. M. (2019). Social inequality in Latin America: institutions, policies, and trends. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 61, 15–38.

Chen, D. (2017). Local distrust and regime support: sources and effects of political trust in China. Polit. Res. Q. 70, 314–326. doi: 10.1177/1065912917691360

Chen, G. (2014). The “tigers” in xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign. East Asian Policy. 6, 30–40. doi: 10.1142/S1793930514000245

De Almeida, S. J., Esperidião, F., and De Moura, F. R. (2024). The impact of institutions on economic growth: evidence for advanced economies and Latin America and the Caribbean using a panel VAR approach. Int. Econ. 178:100480. doi: 10.1016/j.inteco.2024.100480

Dong, L. (2025). “Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign and political consolidation” in China's path to global status: governance (Berlin: Springer).

Evans, P. (1995). Embedded autonomy: states and industrial transformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fabre, G. (2017). Xi Jinping's challenge: what is behind China's anti-corruption campaign? J. Self-Govern. Manag. 5, 7–28. doi: 10.22381/JSME5220171

Fan, C., Wei, O., Li, T., Yan, S., and Wensheng, M. (2019). Elderly health inequality in China and its determinants: a geographical perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16162953

Fang, M., Lai, W., and Xia, C. (2025). Anti-corruption and political trust: evidence from China. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 234:107015. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2025.107015

Fiol-Mahon, A. (2018). Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign: The hidden motives of a modern-day Mao. Philadelphia: FPRI: Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Fuentes, C. D., and Peerally, J. A. (2022). “Transforming innovation Systems for Sustainable Development Challenges: a Latin American perspective” in The emerald handbook of entrepreneurship in Latin America (Leeds: Emerald).

Fukuyama, F. (2014). Political order and political decay: From the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Goldstein, A. (2020). China's grand strategy under xi Jinping: reassurance, reform, and resistance. Int. Secur. 45, 164–201. doi: 10.1162/isec_a_00383

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification Tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271. doi: 10.2307/1913827

He, B. (2018). The Chinese legal system: global perspectives and comparative analysis. Cambridge: Routledge.

Ionescu, L. (2018). Does xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign really support clean and transparent government and market efficiency? Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 10, 167–173. doi: 10.22381/GHIR10120188

La Porta, R., López-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. J. Polit. Econ. 106, 1113–1155. doi: 10.1086/250042

Leff, N. H. (1964). Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. American Behavioral Scientist, 8, 8–14. doi: 10.1177/00027642640080030

Levitsky, S., and Way, L. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: hybrid regimes after the cold war. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, T. (2020). Economic restructuring and innovation in China under xi Jinping. Technol. Innov. Econ. Growth 15, 90–105.

Liu, H., and Liu, Y. (2025). Did the integrity transition promote economic growth? Empirical research based on the perspective of anti-corruption approaches. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 80:104156. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2025.104156

Lopez, T., and Alvarez, C. (2018). Entrepreneurship research in Latin America: a literature review. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 31, 736–756. doi: 10.1108/ARLA-12-2016-0332

Mamo, D. K., Ayele, E. A., and Teklu, S. W. (2024). Modelling and analysis of the impact of corruption on economic growth and unemployment. Oper. Res. Forum 5:36. doi: 10.1007/s43069-024-00316-w

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 681–712. doi: 10.2307/2946696

Méon, P.-G., and Weill, L. (2010). Is corruption an efficient grease? World Development, 38, 244–259. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.004

Miao, Y. (2022). Análisis de las similitudes y diferencias en América Latina—comentario del libro Latin American Politics and Development. Revista Científica Cultura, Comunicación y Desarrollo 7, 22–25. Available online at: https://rccd.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/aes/article/view/386.

Mugellini, G., Rossi, F., and Tanzi, V. (2021). Public sector reforms and their impact on the level of corruption: a systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 17:e1173. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1173

Mushkat, M., and Mushkat, R. (2020). Combatting corruption in the "Era of Xi Jinping": a law and economics perspective. Hast. Int. Comp. Law Rev. 43, 137–212. Available online at: https://repository.uclawsf.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol43/iss2/3

Nedopil, C. (2023). China Belt and road initiative (BRI) investment report 2023. Nathan: Griffith University.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onafowora, O. A., and Owoye, O. (2024). Trade openness, governance quality, and economic growth in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int. Econ. 179:100527. doi: 10.1016/j.inteco.2024.100527

Panzabekova, A. Z., Fazylzhan, D., and Imangali, Z. G. (2024). Analyzing the relationship between corruption and socio-economic development in Kazakhstan’s regions. R-Economy 10, 455–474. doi: 10.15826/recon.2024.10.4.028

Peerenboom, R. (2002). China’s long march toward the rule of law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, J. (2018). Policy mobilities as comparison: urbanization processes, repeated instances, topologies. Rev. Adm. Publica 52, 221–243. doi: 10.1590/0034-761220180126

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government: Causes, consequences, and reform. Cambridge University Press. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=es&lr=&id=GGSSCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR17&dq=Rose-Ackerman,+S.+(1999).+Corruption+and+government:+Causes,+consequences,+and+reform.+&ots=PfBXxf5Oy_&sig=1WAbEwhM6VOnpM3g_S5dZmMTd0M

Santos, D. (2022). Domestic stability and economic growth: China’s foreign policy under xi Jinping’s administration (2013-2022). Int. J. Bus. Adm. doi: 10.5430/ijba.v13n5p1

Shamugia, E. (2025). Rule of law and economic performance: a meta-regression analysis. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 87:102677. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2025.102677

Shen, X., Wang, L., and Zhou, Q. (2026). Anti-corruption shocks, political incentives, and regional economic development i n a developmental state. J. Dev. Econ. 158:103606. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2025.103606

Staiano, M. F. (2019). “La relaciones internacionales entre China y América Latina: encontrando un camino común hacia un nuevo orden mundial” in Anuario en Relaciones Internacionales del IRI, 2019 (La Plata: Instituto de Relaciones Internacionales).

Tanzi, V. (1998). Corruption around the world: Causes, consequences, scope, and cures. IMF Staff Papers, 45, 559–594. doi: 10.2307/3867585

Topolewski, Ł. (2025). An empirical analysis of the impact of institutions on economic growth: evidence from Latin American countries. Argum. Oecon. 54, 126–136. doi: 10.15611/aoe.2025.1.08

Tutuncu, A., and Bayraktar, Y. (2024). The effect of democracy and corruption paradox on economic growth: MINT countries. Econ. Change Restruct. 57, 148–170. doi: 10.1007/s10644-024-09726-6

Valdiglesias, J. (2024). Structural changes on the Chinese global foreign aid expenditure. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. doi: 10.1007/s41111-024-00258-y

Wang, Z., and Zeng, J. (2016). Xi Jinping: the game changer of Chinese elite politics? Contemp. Polit. 22, 469–486. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2016.1175098

Wong, S. A., Valverde, I., and Silva, C. A. (2020). Dynamics of the relation between Latin America and China: cluster analysis, 2005–2018. Online J. Mundo Asia Pac. 9, 5–27. doi: 10.17230/map.v9.i16.01

World Bank. (2024). World development indicators (WDI). Available online at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Xu, Z. (2025). Assessing the efficacy of China’s anti-corruption drive: insights from consumer expenditure patterns. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 88:102680. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2025.102680

Yao, Y. (2018). An anatomy of the Chinese selectocracy. China Econ. J. 11, 228–242. doi: 10.1080/17538963.2018.1516274

Yuan, H. (2020). China’s economic model under xi Jinping: prospects and challenges. Asian Dev. Policy Rev. 14, 112–130.

Yuen, S. (2014). Disciplining the party: xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign and its limits. China Perspect. 2014, 41–47. doi: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.6542

Zhang, M. (2024). Measurement and influencing factors of regional economic resilience in China. Sustainability 16:3338. doi: 10.3390/su16083338

Zhao, S. (2022). China's big power ambition under xi Jinping: narratives and driving forces. Cambridge: Routledge.

Zheng, H. (2025). Crisis-driven governance reforms: An analytical framework of institutional capacity, leadership, and collaboration in global governance. Chinese Public Administration Review. doi: 10.1177/15396754251335231

정수아. (2021). Xi Jinping's anti-corruption policy: Succession and Development from Deng's Era. s-space.snu.ac.kr. Available online at: https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/handle/10371/176397

Keywords: control of corruption, rule of law, economic growth, China, Latin America

Citation: Valdiglesias J (2025) From governance to growth: comparative insights on institutional reforms in China and Latin America. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1718532. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1718532

Edited by:

Stacey M. Mitchell, Georgia State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Antonio Bojanic, Tulane University, United StatesAisi Zhang, Xi'an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2025 Valdiglesias. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jhon Valdiglesias, anZhbGRpZ2xlc2lhc29AdW5tc20uZWR1LnBl

Jhon Valdiglesias

Jhon Valdiglesias