Abstract

Whether the leader role and platform jointly structure campaign discourse remains unsettled in hybrid media environments. This study analyzes a balanced corpus of 340 leader-authored statements from Albania’s 2025 parliamentary election to test how four content dimensions: function, tone, frames, and focus, vary by leader role (incumbent vs. opposition), platform [television (TV) vs. Facebook], and their interaction. This study uses validated typologies to code statements, modeling functions and frames with multinomial logit, tone with ordered logit, and focus with binary logit. The models include a leader role × platform term and controls for message length and campaign phase. The results report effects as predicted probabilities and average marginal effects. Findings refine functional theory under hybrid media conditions. Defenses are rare, and near parity between acclaims and attacks reflects offsetting tendencies by leader role. Leader role conditions platform differences rather than producing uniform platform effects. Overall policy focus is higher on television, and the platform effect on focus reverses by leader role (policy emphasis increases for the incumbent on Facebook and decreases for the opposition on Facebook). Framing mirrors these logics: the opposition emphasizes anticorruption on Facebook, the incumbent increases economic framing online, and integration remains the incumbent’s dominant frame without a platform shift. Temporal probes show modest late-campaign increases in television attacks and conflict without altering the core leader’s role through platform patterns. By integrating four content dimensions within a single, leader-constant, cross-platform design, the study demonstrates that platform effects are conditional on leader role. Results advance accounts of hybrid media and provide replicable evidence from a leader-centric, polarized context, with implications for theory, campaign strategy, and media practice.

1 Introduction

Campaign discourse is a defining feature of electoral competition because it shows how political actors attempt to secure voter support by claiming credit, assigning blame, and shaping interpretive narratives about governance and opposition (Benoit, 2007; Lau et al., 2007). Classical accounts of campaign strategy emphasize recurring communicative patterns, most prominently the balance among acclaims, attacks, and defenses, and link these choices to incumbency status and the strategic environment (Benoit, 2007, 2017). At the same time, contemporary campaigning increasingly unfolds in hybrid media systems, where legacy outlets and candidate-controlled platforms coexist and interpenetrate, and where political actors learn to exploit different media “logics” for attention, persuasion, and mobilization (Chadwick, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Strömbäck, 2008). This article addresses a central puzzle at the intersection of these literatures: Do platform differences in campaign discourse operate uniformly, or are they conditional on who is speaking, specifically, whether the speaker is an incumbent or an opposition leader? A large body of research documents role-based asymmetries (incumbents acclaim more; challengers attack more) and platform-based differences (candidate-controlled channels can be more personalized, curated, and emotionally charged) (Benoit, 2007; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Stier et al., 2018; Van Aelst et al., 2012). Yet studies often examine role effects and platform effects separately, and cross-platform comparisons frequently struggle with a core inferential problem: platforms are not randomly assigned, and “platform effects” can be confounded by different speakers, different message types, and different selection processes. As a result, it remains unsettled whether hybrid media environments produce general platform signatures (e.g., “social media is more negative”) or whether platforms amplify role-specific incentives (e.g., incumbents curate a positive record online while challengers intensify critique).

To clarify this question, the study integrates four dimensions widely used to characterize campaign communication: (1) message function (acclaim, attack, defense) from functional theory (Benoit, 2007, 2017), (2) tone (negative, neutral, positive) (Geer, 2006; Haselmayer, 2019), (3) primary framing (conflict, economic, anticorruption, integration, none/other) (Entman, 1993; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000), and (4) focus (policy vs. character), a key indicator in research on personalization and leader-centered competition (Karvonen, 2010; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012). Bringing these dimensions into a single framework allows the analysis to connect how leaders speak (strategy and tone) to what lens they emphasize (frames) and what kind of appeal they prioritize (policy vs. character).

This study examines leader-authored campaign communication across television and Facebook during Albania’s 2025 parliamentary election, comparing an incumbent leader with an opposition leader. Albania is a useful case because electoral competition is strongly leader-centered and campaigning unfolds in a hybrid media environment where both broadcast exposure and candidate-controlled online communication remain politically salient. More detailed contextualisation of the Albanian case is provided in Section 3.1, and the methodological procedures are detailed in Section 3.6.

The article makes three contributions. First, it integrates function, tone, frames, and focus in one analysis rather than treating these features separately, enabling a more complete account of campaign discourse. Second, it demonstrates that platform effects are conditional on leader role, helping to explain why existing findings on online negativity and personalization can appear inconsistent across contexts. Third, it extends comparative evidence on campaign communication in hybrid media systems by providing replicable findings from a leader-centric, polarized electoral context. These contributions also extend prior evidence on Albanian digital campaigning by shifting from municipal-level engagement outcomes to national-level cross-platform message content.

Licenji (2023) examined candidate-managed Facebook and Instagram activity during the 2023 Tirana municipal campaign and related engagement indicators (e.g., likes, shares, follower growth, engagement rate) to electoral performance. Municipal contests typically foreground local performance and proximity appeals, whereas parliamentary contests elevate national governance claims, partisan conflict, and broader issue agendas. The present study extends this municipal baseline by shifting from engagement outcomes to message content and by comparing leader-authored statements across television and Facebook during the 2025 parliamentary campaign.

The results show that defenses remain rare and that the pooled balance between acclaims and attacks reflects offsetting tendencies by role: incumbent discourse is more acclaim-oriented, while opposition discourse is more attack-oriented. Crucially, platform differences are not uniform. The incumbent’s Facebook communication is more affirmative and more policy-focused than their televised discourse, whereas the opposition’s Facebook communication concentrates attacks and character-centered critique relative to television. Framing follows the same conditional logic: the opposition’s anticorruption emphasis is especially salient on Facebook, while the incumbent’s economic framing increases online, and integration remains the incumbent’s dominant theme without a strong platform shift.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews scholarship on campaign strategy, framing, personalization, and hybrid media and develops the research questions and hypotheses. Section 3 presents the research design, case context, corpus construction, coding and reliability procedures, and modelling strategy. Section 4 reports results. Section 5 interprets the findings in light of theory and alternative explanations. Section 6 concludes with a concise summary, contributions, implications, and limitations.

2 Campaign discourse as strategic communication

Election campaigns constitute strategic contests in which political actors compete for support by claiming credit, assigning blame, and defining opponents. Scholarship often analyzes campaign discourse across four dimensions: strategic function, tone, framing, and focus (Benoit, 2007; Entman, 1993; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). Hybrid media systems combine legacy outlets with candidate-controlled platforms, and professionalized, data-driven campaign practices intensify strategic calibration across venues, especially in polarized, leader-centric democracies (Blumler and Kavanagh, 1999; Chadwick, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Hersh, 2015; Kreiss, 2016; Stier et al., 2018).

2.1 Functional theory: acclaims, attacks, and defenses

Political context and media environment shape campaign discourse across democracies. Transitional democracies often exhibit strong personalization and leader-centric appeals, and the prevalence and consequences of negativity vary across institutional settings (Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012; Lau et al., 2007; Voltmer, 2013). At the same time, personalization and polarization are now widespread in many established democracies, so the key moderating factors are not regime type alone but the interaction of institutions, polarization, and media incentives (Haselmayer, 2019; McCoy and Somer, 2019; Nai, 2020). Functional theory distinguishes acclaims, attacks, and defenses and predicts systematic role differences: incumbents typically emphasize acclaims, challengers rely more on attacks, and defenses remain rare (Benoit, 2007, 2017; Benoit and Sheafer, 2006; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010). However, the acclaim–attack balance is not fixed. Institutional arrangements, polarization, and media incentives shape when negativity pays and how strongly campaigns personalize around leaders (Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Lau et al., 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012; Voltmer, 2013; Nai and Walter, 2015). These conditions characterize many transitional democracies and are also increasingly visible in several established democracies, where personalization and affective polarization have intensified (Haselmayer, 2019; McCoy and Somer, 2019; Nai, 2020).

2.2 Tone and the deployment of negativity

Tone captures the evaluative valence of campaign messages-positive, neutral, or negative, and remains conceptually distinct from function (Geer, 2006; Haselmayer, 2019). Comparative research links greater negativity to challenger status, ideological extremity, and polarized or close contests, while platform engagement dynamics can privilege emotive and confrontational content online (Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; Valli and Nai, 2022; Stier et al., 2018; Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2023). Meta-analytic work finds heterogeneous and context-dependent effects of negative campaigning, including risks of backlash and cynicism (Lau et al., 2007; Haselmayer, 2019).

2.3 Frames salient in Albania’s campaign context

In Albania’s electoral discourse, four frames repeatedly structure campaign rhetoric: conflict, economic, anticorruption, and integration. Conflict frames depict elections as high-stakes, often zero-sum contests and are linked to increased cynicism when strategy coverage prevails (Cappella and Jamieson, 1997; Voltmer, 2013). Economic frames emphasize jobs, growth, prices, and fiscal consequences; anticorruption frames foreground integrity, rule of law, and wrongdoing; and integration frames emphasize European alignment and international positioning (Elbasani, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015; Voltmer, 2013). Patterns of use are actor conditioned: oppositions frequently mobilize anticorruption to delegitimize incumbents, while incumbents tend to claim credit on the economy or integration (Elbasani, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015; Voltmer, 2013). Frames often cooccur with functions (e.g., anticorruption attacks and economic acclaims), linking what is emphasized to how it is deployed and how responsibility and policy support are shaped (de Vreese, 2005; Matthes and Kohring, 2008; Geise and Maubach, 2024). Platform dynamics also modulate visibility: conflictual and scandal-oriented frames travel well in attention seeking, engagement driven environments, whereas economic and integration frames often scaffold incumbents’ credit claiming (Stier et al., 2018). In the Western Balkans, EU integration often supplies an incumbent friendly achievement frame, whereas anticorruption remains a versatile opposition frame, two templates that regularly co-occur with functional choices (economic acclaims and anticorruption attacks) (de Vreese, 2005; Elbasani, 2013; Matthes and Kohring, 2008; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015).

2.4 Focus: policy versus character in personalized competition

Focus distinguishes policy-focused appeals (issues, performance, plans) from character-focused appeals (traits, integrity, leadership style). Work on personalization and the presidentialization of parliamentary systems documents a leader centered shift in mediated competition (Karvonen, 2010; Poguntke and Webb, 2005; Van Aelst et al., 2012). Character appeals can engage audiences and provide heuristics about competence or empathy, but overemphasis risks crowding out substantive policy debate; the balance varies with leader role, platform incentives, and media logics (Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012). Candidate controlled channels typically accentuate personal narrative and identity building, whereas broadcast formats elicit policy justifications alongside conflict worthy moments, reinforcing systematic cross platform differences (Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Klinger and Svensson, 2015). Personalization pressures are platform sensitive: candidate-controlled channels afford identity building and intimacy cues, while broadcast formats incentivize policy justification and institutional accountability (Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Strömbäck, 2008).

2.5 Platform logics in a hybrid media system

The hybrid media thesis holds that legacy and digital media coexist and interpenetrate, each governed by distinct logics that political actors learn to exploit (Chadwick, 2013). A platform-first view shows how algorithms, interaction tools, and datafication routines affect the style and targeting of messages, even from the same messenger (Bossetta, 2018; Hersh, 2015; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Kreiss, 2016). Television, shaped by journalistic norms and heterogeneous audiences, encourages policy justification while amplifying conflict-worthy soundbites (Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Strömbäck, 2008). Social media afford direct access, format control, and rapid feedback, encouraging curation, personalization, and emotional expression (Bossetta, 2018; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Klinger and Svensson, 2015). Candidate-controlled channels often emphasize acclaims and identity-building, although engagement incentives can also elevate negativity online (Stier et al., 2018; Klinger et al., 2023). Therefore, even when the messenger remains constant, there are expected systematic cross-platform differences in function, tone, framing, and focus (Lilleker et al., 2017). Theory expects leader role to condition platform differences rather than produce uniform effects.

2.6 Integrative framework and research gap

Synthesizing these strands yields a simple framework. Two conditions, leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) and platform (television vs. social media), jointly shape four content outcomes: function (acclaim, attack, defense), tone (positive, neutral, negative), primary frame (conflict, economic, anticorruption, integration, none), and focus (policy vs. character). In polarized settings, oppositions have stronger incentives to attack and invoke conflict or anticorruption themes, whereas incumbents are more likely to emphasize acclaims tied to economic performance or integration achievements (Benoit, 2007; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015). Platform logics further shape these patterns: social media favor curated, personalized styles, while television favors policy justification with conflict-driven contrasts (Chadwick, 2013; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014). Despite substantial theorizing, leader-authored cross-platform analyses that examine function, tone, frames, and focus together remain scarce, particularly in transitional, polarized democracies, so it is uncertain whether canonical patterns (acclaims ≥ attacks; defenses rare; policy > character) generalize to leader-centric hybrid systems (Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Elbasani, 2013; McCoy and Somer, 2019; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015). This gap leaves open questions about the interplay of strategy, tone, framing, and focus under varying media logics.

To address these gaps, the current study integrates all four content dimensions within a single, leader-constant, cross-platform design. The framework expects platform effects to depend on leader role: incumbents will lean more toward acclaims and economic/integration frames, whereas challengers will amplify attacks and conflict/anticorruption frames, especially under high polarization (Benoit and Sheafer, 2006; Elbasani, 2013; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; McCoy and Somer, 2019; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015).

2.7 Research questions and hypotheses

Building on functional theory, framing, personalization, and hybrid media research, this article asks two research questions about leader-authored campaign communication across television and Facebook:

RQ1: How do leader-authored campaign messages vary in function, tone, framing, and focus, and to what extent do leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) and platform (television vs. Facebook) condition these features in a polarized, hybrid media environment?

RQ2: Do platform-conditioned patterns change over the course of the campaign? Specifically, do attacks, conflict/anticorruption frames, and character-focused appeals become more salient as election day approaches?

To evaluate the expectations implied by these questions, the study tests the following hypotheses:

H1 (baseline distribution of functions). Absent conditioning on the leader role or platform, campaign discourse will exhibit the canonical hierarchy: defenses are least frequent, and acclaims are at least as frequent as attacks (Benoit, 2007, 2017; Benoit and Sheafer, 2006).

H2 tests how leader role conditions strategy and tone. Conditional on the leader role, opposition discourse will be more attack-oriented (vs. acclaim) and more negative in tone, whereas incumbent discourse will be more acclaim-oriented and positive in tone; under hybrid media logics, platform may further condition these differences (Chadwick, 2013; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; Geer, 2024; Haselmayer, 2019; Valli and Nai, 2022).

H3 focuses on the role and frames of the leader. Relative to incumbents, opposition discourse will more frequently employ conflict and anticorruption frames, whereas incumbent discourse will more frequently employ economic and integration frames (Cappella and Jamieson, 1997; Elbasani, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000).

H4 (focus: policy vs. character, with platform conditioning). Policy-focused appeals will predominate overall, yet character-focused content, especially character-based criticism, will appear more often in opposition discourse; hybrid media logics of curation and engagement imply that platform conditions this difference (Chadwick, 2013; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Karvonen, 2010; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012).

H5 focuses on the differences between platforms and the role of the leader. Cross-platform differences are expected across outcomes. Social media will feature more personalized (character-focused) appeals and, conditional on leader role, a different balance of acclaims and attacks than television; broadcast settings will feature more conflict-framed appeals in line with news values (Chadwick, 2013; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Lilleker et al., 2017; Stier et al., 2018). The expectation that broadcast carries more conflict-framed content is also consistent with well-established news values that prioritize conflict and ‘bad news’ in agenda construction (Galtung and Ruge, 1965; Harcup and O’Neill, 2017).

Accordingly, this study probes whether late-campaign periods exhibit higher shares of attacks, conflict/anticorruption frames, and character-focused appeals, consistent with observed late surges in negative advertising and research on the timing of negativity effects (Wesleyan Media Project, 2018; Krupnikov, 2014).

3 Methodology

3.1 Context and case selection

The analysis centers on Albania’s 2025 parliamentary election, a contest taking place in a political environment where competition is strongly leader-centered and party organizations are highly centralized around their national leaders (Poguntke and Webb, 2005; Karvonen, 2010; Passarelli, 2019). This leader-centric structure makes the incumbent–opposition contrast especially salient for campaign strategy because public responsibility, credit-claiming opportunities, and blame attribution are concentrated on the top leadership rather than dispersed across multiple competing party figures. The campaign therefore provides an analytically tractable setting for examining how leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) conditions communicative strategy and how this interacts with platform (television vs. Facebook). Substantively, Albania is also a case where the issue environment maps closely onto the framing categories used in the analysis. Across Western Balkan contexts, anticorruption contestation and integrity claims are common instruments of opposition accountability, while incumbents often foreground governance performance through economic narratives and claims about international alignment and European integration (Elbasani, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015; McCoy and Somer, 2019). These recurrent axes of competition correspond directly to the study’s primary frames (anticorruption, economic, integration, and conflict), enabling a theoretically meaningful link between what leaders emphasize (frames) and how they deploy those emphases (functions and tone). Albania is therefore a demanding and informative test case: leader-centric competition and a polarized hybrid media environment amplify incentives for both curated self-presentation and conflictual contrasts (Licenji and Hoxha, 2024). Albania’s media landscape further strengthens the value of a cross-platform design. Television retains broad reach and agenda-setting influence, while Facebook functions as a major candidate-controlled channel that enables direct, curated communication and rapid response (Chadwick, 2013; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014). Long-standing features of the media and political environment-political parallelism, concentrated ownership, and recurring concerns about political influence over news agendas-intersect with digital uptake to shape campaign communication incentives and the balance between gatekept and candidate-controlled visibility [Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Londo, 2021; Media Ownership Monitor (MOM) Albania, 2023; IREX, 2024]. Audience indicators point to very high internet and smartphone penetration alongside near-universal television access, underscoring the empirical salience of both channels during the campaign period (INSTAT, 2024; International Telecommunication Union, 2024). In the run-up to the election, parties endorsed a voluntary Code of Conduct on digital campaigns, reflecting recognition of platforms’ centrality and the need for baseline norms (International IDEA, 2025a,b). Taken together, these features make Albania a theoretically informative “most-likely” case for observing role-conditioned platform repertoires in campaign discourse.

3.2 Design and scope

This study uses a quantitative content-analytic design to examine leader-authored campaign discourse on television (TV) and Facebook during the legally defined 2025 campaign window (early April through 11 May 2025). This dual-channel focus aligns with evidence that, in hybrid media systems, legacy broadcast outlets retain mass reach and gatekeeping influence, while candidate controlled social platforms enable direct, personalized appeals (Chadwick, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013). The sampling frame mirrored audience indicators showing high rates of internet use (including smartphone access) alongside televisions near universal household presence (INSTAT, 2024; International Telecommunication Union, 2024).

This study focuses on Facebook because it is a central channel for leader-authored campaign communication in Albania and supports comparatively substantive textual captions that can be meaningfully analyzed alongside TV transcripts. Verified leader pages also make authorship and sourcing transparent, enabling a leader-constant sampling frame. At the same time, this study does not treat Facebook as a proxy for all digital campaigning: platform affordances differ, and dynamics on video-first platforms such as TikTok or Instagram Reels may diverge. This study therefore interprets the results as a Facebook-versus-television comparison within a hybrid media system and treats multi-platform extensions as an important direction for future research.

3.3 Corpus construction

A near-census capture protocol mitigated selection bias and supports replication (Neuendorf, 2017). The analysis uses the statement as the unit of analysis. Eligible items included leader-authored, campaign-relevant speech aired on TV (e.g., rally clips, interviews, debate excerpts) and leader-authored, campaign-relevant text posted on the leaders verified Facebook pages (issues, pledges, contrasts). The corpus excludes Facebook posts without original leader text (pure reshares) and TV items consisting solely of anchor commentary without direct leader quotations. For Facebook posts that combine text and video, coders merged the caption and transcript and treated them as a single unit. For TV, coders transcribed the leader’s spoken segment as a single unit and excluded adjacent anchor commentary. The protocol removed cross-outlet duplicates and retained near-duplicates only when substantive expansions or platform-specific tailoring appeared.

Native-speaker coders coded content in the original language. Coders transcribed speech verbatim and normalized orthography without altering meaning. Emojis, hashtags, and URLs remained when semantically informative (e.g., #anticorruption) and were removed otherwise. The dataset stores timestamps and source metadata (platform, outlet/program, URL or permalink) to ensure traceability. The sampling frame covered verified Facebook pages and national TV news/talk formats operating during the official campaign window. The protocol excluded items that failed the eligibility criteria or consisted solely of imagery without text or speech. The corpus logs all inclusion/exclusion decisions to support audit and replication.

A balanced corpus sampling strategy (85 statements per leader role × platform cell; total N = 340) ensures comparability across conditions and enables valid role-by-platform contrasts. The analytical strategy matches statistical models to each outcome’s measurement level: multinomial logistic regression for nominal outcomes (function and frames), ordered logit for ordinal outcomes (tone), and binary logit for dichotomous outcomes (focus) (Agresti, 2002; Long and Freese, 2014). To equalize cell sizes, the procedure drew a uniform random sample without replacement when a cell exceeded the target; when a cell matched the target, the procedure retained all items. The resulting dataset includes N = 340 statements (170 per leader; 85 per leader role × platform cell). Supplementary File 3 (Sources) lists the verified Facebook handles and TV outlets/programs included.

Balancing the leader role × platform cells strengthen comparability by preventing differences in communication volume from driving the estimates. The models therefore compare content distributions within each condition rather than reflecting overall message volume. This choice trades some representativeness of real-time campaign output for inferential clarity about strategy. Accordingly, the analysis interprets results as differences in message content conditional on platform use, not as claims about who communicated more or which platform dominated the campaign agenda. The corpus log retains the full near-census pool and documents original volumes, enabling robustness checks with the unbalanced pool or volume-weighted estimates.

3.4 Operationalization of study variables

The study operationalized all variables at the statement level using validated typologies in political communication, with minimal context specific adaptations to preserve content validity (Benoit, 2007, 2017; de Vreese, 2005; Entman, 1993; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). Coders read each unit (transcript with caption, where applicable) in full and coded for the dominant communicative thrust; decision rules enforced mutual exclusivity where required and established boundaries among adjacent constructs (Neuendorf, 2017; Riffe et al., 2019). Coders assigned one of three categories to function: acclaim (positive self-presentation/credit claiming), attack (criticism of an opponent), or defense (refutation of prior criticism), with salience, span, and argumentative purpose guiding classification when multiple acts co-occurred (Benoit, 2007, 2017).

Tone captured overall evaluative valence-negative, neutral, or positive-and the study treated tone as distinct from function (Geer, 2006; Lau et al., 2007).

Primary frame identified the dominant thematic lens-conflict, economic, anticorruption, integration, or none/other-with coding anchored in problem definition and causal diagnosis rather than keyword counts (de Vreese, 2005; Entman, 1993; Matthes and Kohring, 2008; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). These categories operationalize deductive frames rather than inductive topics. The coding scheme therefore follows a theory-driven logic to preserve interpretability and to test hypotheses using established typologies. Unsupervised text-as-data methods (e.g., topic models or embedding-based clustering) can recover latent clusters of co-occurring terms, but such clusters do not necessarily map one-to-one onto frame constructs, especially in leader-constant corpora and non-English text where topics may reflect names, events, or stylistic markers as much as thematic framing (Grimmer and Stewart, 2013). Future work can directly compare this deductive frame set to inductive topics as a robustness extension, scaling the approach to larger multi-election corpora in line with recent work on dynamic political marketing systems (Kübler et al., 2025).

Focus distinguished policy focused appeals (positions, performance, plans, pledges) from character focused appeals (competence, integrity, empathy, leadership), with a dominant focus assigned when both were present (Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012).

Function and tone capture the evaluative act (acclaim/attack/defense; positive/neutral/negative), whereas frames capture the dominant substantive lens through which a message defines a problem or emphasizes an issue domain. Coders coded the four dimensions independently: each statement receives a function, a tone code, a primary frame, and a policy-versus-character focus. To prevent conflating negative topics with negative strategy, coders followed a fixed decision sequence. First, coders identified the dominant target and argumentative purpose (function: praise/credit-claiming vs. criticism vs. rebuttal). Second, they coded overall valence (tone) of the statement. Third, they identified the primary frame based on the dominant problem definition and causal diagnosis rather than keywords or evaluative language (e.g., anticorruption when integrity/corruption is the core problem; conflict when politics is presented primarily as confrontation/competition). Finally, coders assigned the dominant focus (policy vs. character) when both elements co-occurred. Under this scheme, an anticorruption-themed message can be an acclaim, an attack, or a defense, and conflict framing can occur in both acclaims and attacks.

Table 1 summarizes variable coding and baselines. Supplementary File 9 (Codebook) presents the full codebook including measurement decisions, boundary rules, and anonymized examples for each category, and Supplementary File 2 reports reliability statistics.

Table 1

| Block | Variable | Type | Levels/codes | Used in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV | Function | Nominal | 1 = Acclaim, 2 = Attack, 3 = Defense | H1, H2, H5 (MN Logit) |

| DV | Tone | Ordered | 1 = Negative, 2 = Neutral, 3 = Positive | H2, H5 (Ordered logit) |

| DV | Primary frame | Nominal | 1 = Conflict, 2 = Economic, 3 = Anticorruption, 4 = Integration, 5 = None/Other | H3, H5 (MN Logit) |

| DV | Focus | Binary | 1 = Policy, 0 = Character | H4, H5 (Logit) |

| Focal | Leader role | Binary | 0 = Incumbent, 1 = Opposition | All models |

| Focal | Platform | Binary | 0 = TV, 1 = Facebook | All models |

| Moderator | Leader × Platform | Interaction | Leader role × Platform | H2–H5 |

| Controls | Message length | Numeric | Total word count | H2–H5 |

| Controls | Campaign phase | Ordinal | 1 = Early (1–17 Apr); 2 = Mid (18–30 Apr); 3 = Late (1–10 May) | H2–H5 |

Variable definitions and coding scheme (outcomes, focal predictors, moderator, and controls).

See Supplementary File 9 (B2) for the complete variable dictionary, numeric codes, and examples; reliability statistics appear in Supplementary File 2.

3.5 Focal predictors, moderator, and controls

Leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) and platform (TV vs. Facebook) served as focal predictors. A leader role by platform interaction tested whether platform differences were leader role–conditioned in line with hybrid media expectations (Chadwick, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014). All models include two controls: message length (total word count) and campaign phase. To capture temporal dynamics within the campaign window, the study discretized phase ex ante as Early (1–17 April 2025), Mid (18–30 April 2025), and Late (1–10 May 2025). Phase was defined ex ante to match the official campaign window: Early (1–17 April 2025), Mid (18–30 April 2025), Late (1–10 May 2025); election-day items (11 May) were flagged where applicable (OSCE/ODIHR, 2025).

3.6 Methods: corpus, coding, and analytical strategy

This section summarizes the data, coding, and modelling procedures used to compare leader-authored statements across television and Facebook during the official campaign period. Using a balanced corpus of 340 leader-authored statements (85 per leader role × platform cell) from the official campaign period, the analysis applies a theory-driven coding scheme for function, tone, frames, and focus and estimates generalized linear models with leader role, platform, and their interaction, controlling for message length and campaign phase. Human coders conducted the content analysis. The study trained two native-language coders on a pilot subset to calibrate decision rules (Neuendorf, 2017). Training emphasized discriminating function from tone, identifying the dominant focus when multiple elements co-occurred, and applying frame definitions to context-specific language. Following training, coders independently double-coded a random 15–20% overlap of the full corpus. The study used Krippendorff’s alpha (α) as the principal reliability coefficient for nominal variables, given its suitability for content analysis and its accommodation of coder disagreement and missingness (Krippendorff, 2013). Consistent with established standards, the study treated α ≥ 0.80 as the target for acceptable reliability, with values ≥ 0.67 considered minimally acceptable for tentative conclusions (Krippendorff, 2013; Neuendorf, 2017). The study also reported percent agreement as a descriptive complement (Lombard et al., 2002). After estimating reliability, coders adjudicated discrepancies through discussion to produce a single reconciled code per item; because reconciliation occurred after computing α, it did not inflate reliability estimates. The combination of coder training, codebook specificity, and reliability thresholds supports replicability and measurement consistency (Riffe et al., 2019). Supplementary File 9 documents a step-by-step coding workflow, audit trail fields, and the adjudication protocol (Sections B4–B5).

3.7 Analytical strategy and model adequacy

Analyses proceeded in two stages. First, the study summarizes each outcome by leader role and platform using cross-tabulations and evaluates bivariate associations with chi-squared tests when expected cell counts are adequate; for sparse tables, the study uses Fisher’s exact test (Agresti, 2002; Fisher, 1922).

Second, the study estimates generalized linear models matched to each outcome’s measurement level: multinomial logit for nominal outcomes (function and primary frame), ordered logit for the ordinal outcome (tone), and binary logit for the dichotomous outcome (focus) (Agresti, 2002; Long and Freese, 2014). Baselines and coding decisions are held constant across results: Function baseline = Acclaim; Frame baseline = Anticorruption; tone ordered from negative to neutral to positive; Focus coded policy = 1 (character = 0).

All models include leader role, platform, and a leader role × platform interaction, alongside message length and campaign phase as controls. The study reports robust (Huber–White) standard errors; Supplementary File 1 additionally reports cluster-robust standard errors clustered by outlet/program (Huber, 1967; White, 1980; Cameron and Miller, 2015).

For tone models, the proportional-odds assumption is tested using the Brant test; when diagnostics indicate non-parallel slopes, the study estimates partial proportional-odds models (Brant, 1990; Williams, 2006). For multinomial models, the independence-of-irrelevant-alternatives (IIA) assumption is probed using Hausman–McFadden and Small–Hsiao tests; robustness checks examine alternative baselines and principled category collapsing, with Supplementary File 1 noting the known fragility of IIA diagnostics (Hausman and McFadden, 1984; Small and Hsiao, 1985; Rouwendal, 2018). For binary and ordered models, the study inspects global fit indices, AIC, BIC, McFadden’s pseudo R2, and variance inflation factors (VIFs), interpreted with caution (Akaike, 1974; Schwarz, 1978; McFadden, 1974; O’Brien, 2007).

Results are reported as predicted probabilities and average marginal effects, holding controls at their observed means (Williams, 2012; Long and Freese, 2014). Supplementary File 9 provides compact model equations, the mapping from coded variables to statistical models, and a Stata replication skeleton (Sections B7–B10).

3.8 Ethics, and transparency

The study relies exclusively on publicly available campaign communication (broadcast segments containing leader quotations and posts from verified Facebook pages). No private, sensitive, or non-public personal data were collected. To support transparency and replication, Supplementary File 2 provides the codebook and reliability documentation, Supplementary File 3 lists outlets/programs and verified handles, and Supplementary File 9 documents the coding workflow and replication skeleton. Limitations and future research are discussed in Section 6.4.

4 Results

Analyses drew on a balanced corpus of 340 leader authored statements (170 per leader; 85 per leader role by platform cell) produced during the campaign window. Coders coded each statement for function, tone, primary frame, and focus. The analysis modeled outcomes with generalized linear specifications matched to measurement scale: multinomial logit for function and primary frame (with theory consistent baselines), ordered logit for tone, and binary logit for focus (the Brant test was applied; partial proportional odds models were estimated where diagnostics indicated non parallel slopes; Brant, 1990; Williams, 2006). Leader role (incumbent vs. opposition), platform (TV vs. Facebook), and their interaction served as focal terms; the models include message length and campaign phase as controls. Estimation proceeded by maximum likelihood with robust (Huber–White) standard errors (Huber, 1967; White, 1980).

Figures 1–4 visualize the interaction patterns with model-based predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence intervals where applicable), complementing the full coefficient tables in the appendices.

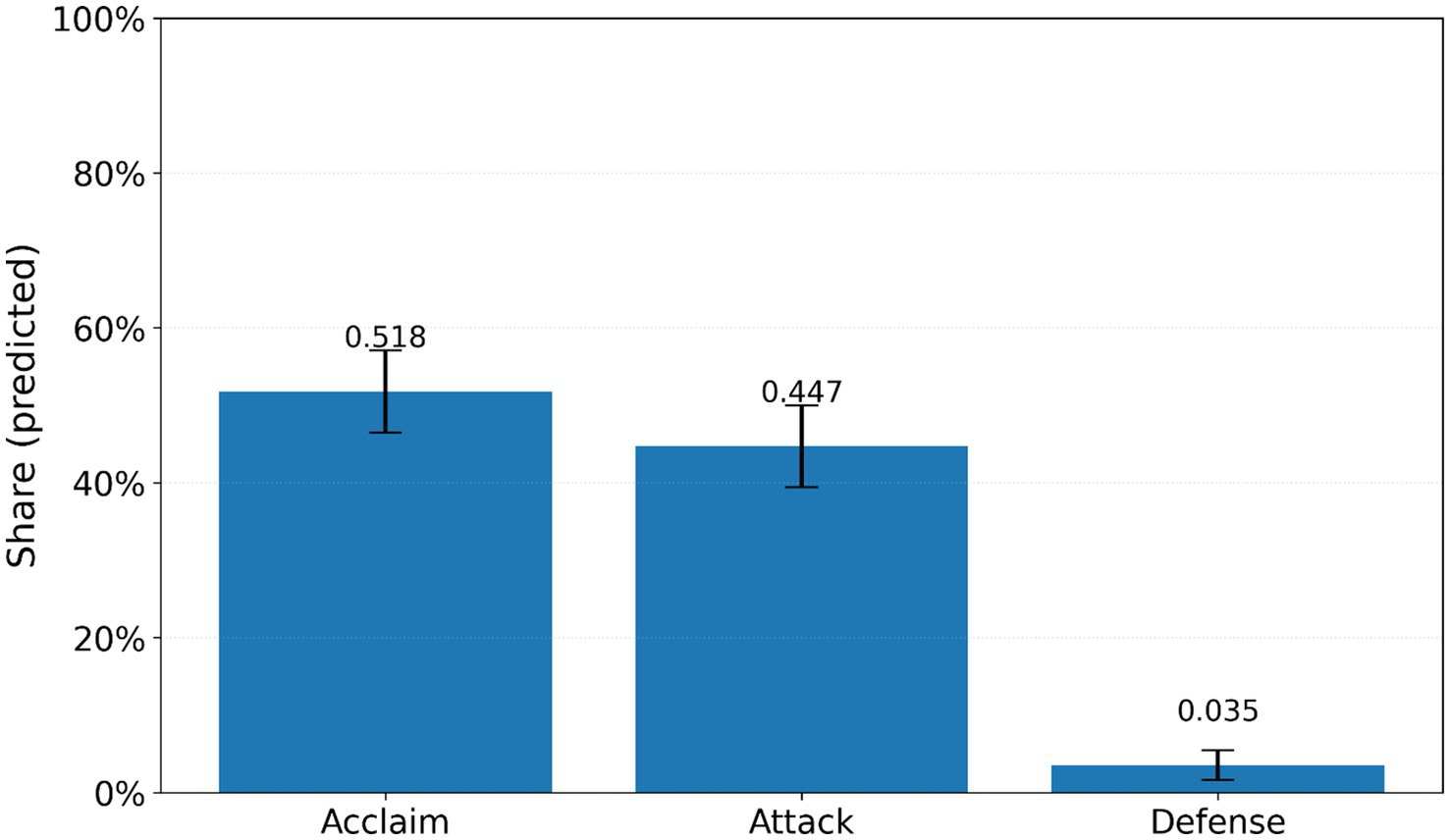

Figure 1

Message functions (pooled). Bars show model-based predicted probabilities from an intercept-only multinomial logit of message function (Acclaim, Attack, Defense) estimated on the pooled corpus (N = 340). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for the pooled probabilities.

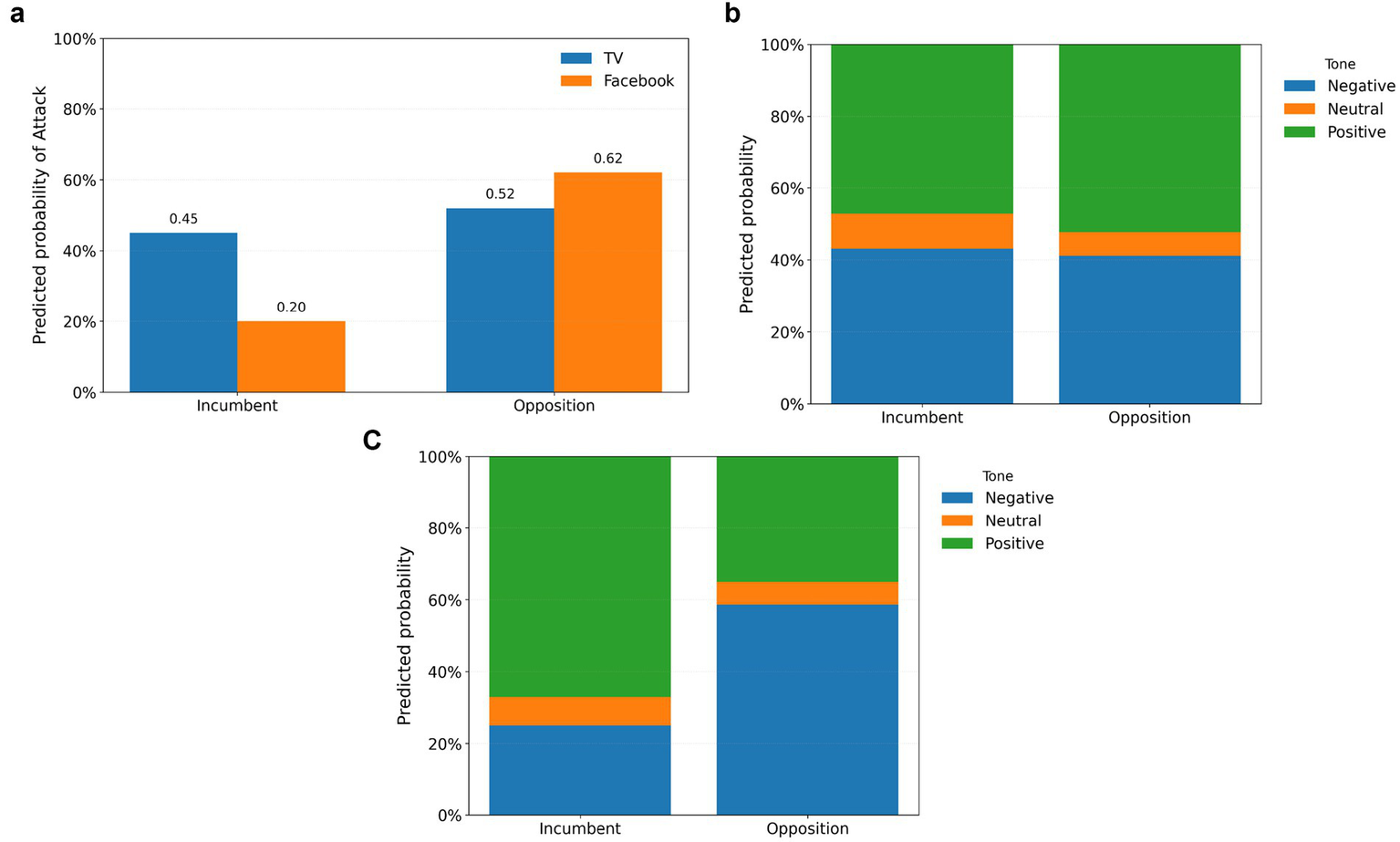

Figure 2

(a) Attack probability by leader role × platform. Bars report model-based predicted probabilities that a statement performs an attack (vs. acclaim/defense) by leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) and platform (TV vs. Facebook), holding controls at their reference values/means as in the estimation output. (b) Tone on TV (predicted). Stacked bars report predicted probabilities of negative, neutral, and positive tone for incumbent and opposition statements on television, derived from the ordered-response tone model. (c) Tone on Facebook (predicted). Stacked bars report predicted probabilities of negative, neutral, and positive tone for incumbent and opposition statements on Facebook, derived from the ordered-response tone model.

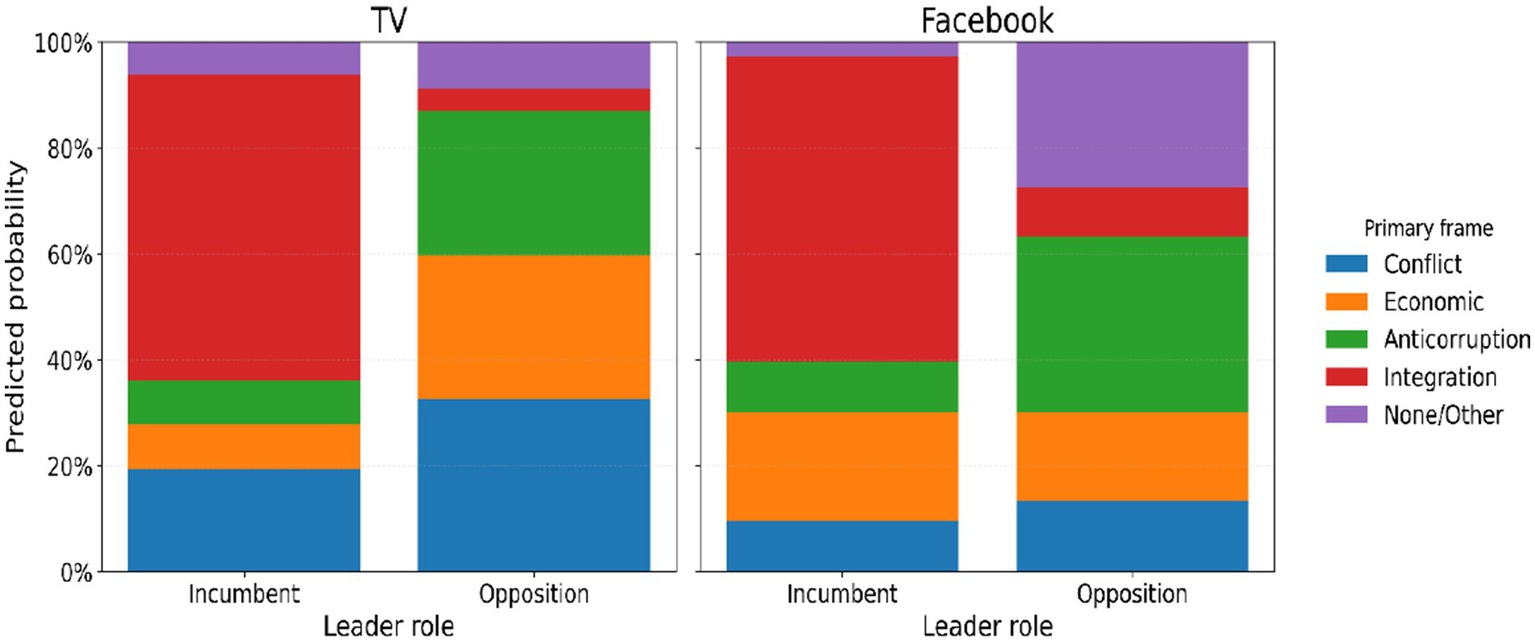

Figure 3

Primary frame distribution by leader role and platform (predicted). Stacked bars report predicted probabilities of the dominant frame (Conflict, Economic, Anticorruption, Integration, None/Other) by leader role within each platform (TV vs. Facebook), derived from the multinomial frame model.

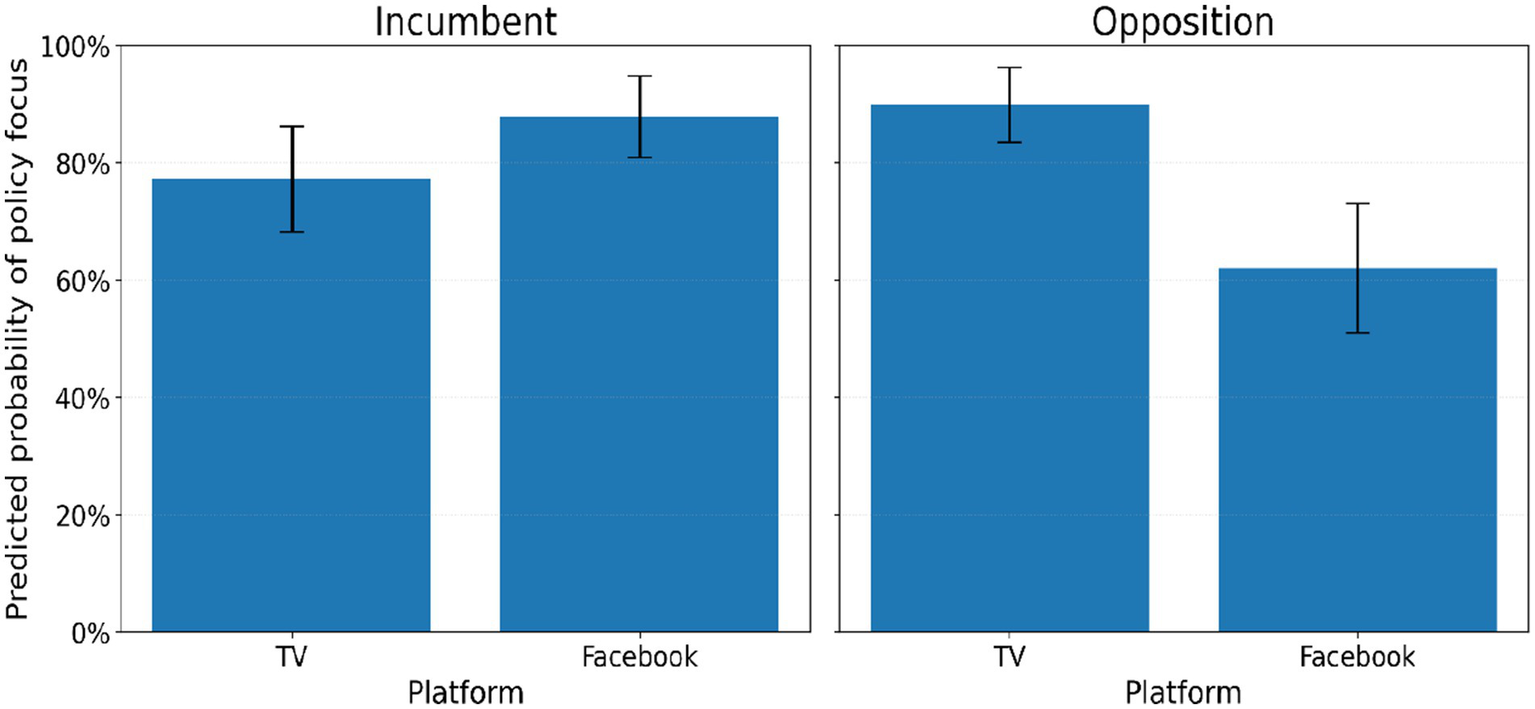

Figure 4

Policy focus by platform within leader role (predicted probabilities with 95% confidence intervals). Bars report model-based predicted probabilities that a leader-authored statement emphasizes policy (vs character), separately for incumbents and opposition leaders and for TV versus Facebook. Confidence intervals reflect uncertainty in the predicted probabilities (controls held at their reference values/means as in the prediction table).

As above, the analysis held baselines and coding constant: it uses Acclaim as the function baseline and Anticorruption as the frame baseline; it orders tone from negative to neutral to positive; and it codes policy focus as 1.

Diagnostics indicated no material violations. For tone, the proportional odds assumption held in pooled models, with relaxations applied where warranted. The Hausman–McFadden and Small–Hsiao tests did not reject the IIA assumption (Brant, 1990; Williams, 2006; Hausman and McFadden, 1984; Small and Hsiao, 1985; Agresti, 2002; Long and Freese, 2014).

4.1 Distribution of message functions (H1)

Functional theory predicts more acclaims than attacks, with defenses least frequent (Benoit, 2007, 2017; Benoit and Sheafer, 2006). In the pooled corpus (N = 340), acclaims and attacks occupied broadly comparable shares, with defenses rare (acclaims 51.8%, attacks 44.7%, defenses 3.5%). In the intercept only model, the defense versus acclaim contrast was strongly negative (z = −9.00, p < 0.001), confirming that leaders used defenses least often. By contrast, the attack versus acclaim contrast was negative but not statistically distinguishable from zero (z = −1.32, p = 0.186), indicating that the pooled share of attacks and acclaims was statistically similar. Leader specific descriptives clarify the aggregate pattern: among the incumbent (PS), acclaims predominated over attacks (61.8% versus 32.9%), with defenses at 5.3%; among the opposition (PD), attacks were more common than acclaims (56.5% versus 41.8%), with defenses at 1.8%. The absence of a pooled difference between acclaims and attacks therefore reflects role conditioned structures consistent with functional theory’s incumbency logic (Benoit, 2007; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010). Supplementary File 4 (H1 Function) provides full estimates and observed distributions.

Conclusion (H1). Taken together, the baseline picture is of a campaign that praises and criticizes in almost equal measure, not because the strategies are equally preferred, but because each leader leans in a different direction. The incumbent speaks in the language of credit claiming, the opposition in the language of critique; when pooling their voices, acclaims and attacks converge and defenses recede to the margins. This offsetting structure is consistent with functional theory’s incumbency logic and sets up the next step of the analysis, which examines leader role explicitly alongside the platform in H2 (Benoit, 2017; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010).

4.2 Leader role conditioned tone and strategy (H2)

Theory expects opposition discourse to be more attack-oriented and negative in tone, whereas it expects incumbent discourse to be more acclaim-oriented and positive, leader role conditioning any platform differences.

Function: Model-based predictions show a clear crossover between leader roles and platforms. For the incumbent, the probability of an attack is markedly lower on Facebook than on television (approximately 0.45 on TV to 0.20 on Facebook). For the opposition, the probability of an attack is higher on Facebook than on television (≈ 0.52 on TV to ≈ 0.62 on Facebook). Substantively, moving from television to Facebook reduces the incumbent’s predicted attack probability by about 25 percentage points (≈ 0.45 to ≈ 0.20) and increases the opposition’s predicted attack probability by about 10 points (≈ 0.52 to ≈ 0.62). The leader role by platform interaction is statistically significant (p = 0.001), indicating that platform differences depend on who is speaking (Figure 2; Supplementary File 9, H2 Function and Tone).

Tone: The tone results align with this pattern. The pooled ordered logit estimates the Facebook platform to a modestly more positive tone (p = 0.007), but this average masks a significant leader role through platform interaction (p = 0.001). Substantively, the incumbent becomes more positive on Facebook (p = 0.013), whereas the opposition becomes more negative on Facebook (p = 0.046) (Figures 2b,c; Supplementary File 9, H2 Function and Tone).

Conclusion (H2). The evidence supports H2. Incumbency advantages in credit claiming and reputation management manifest in fewer attacks and a more positive profile for the incumbent on Facebook. The opposition, by contrast, concentrates attacks and has a negative tone online while maintaining high attack levels on television. In short, platform effects are not uniform; they amplify leader role asymmetries in a hybrid media environment.

4.3 Leader role and frames (H3)

Guided by H3, the expectation was that the opposition would lean more on conflict and anticorruption, whereas incumbents would emphasize economics and integration. The analysis estimated the primary frame with a multinomial logit (baseline: Anticorruption) including leader role, platform, their leader role by platform interaction, and the study controls.

The pattern is straightforward. For the opposition, the use of anticorruption is higher on Facebook than on television (about 0.33 on Facebook versus 0.27 on television). For the incumbent, the economic frame is more frequent on Facebook than on television (about 0.20 on Facebook versus 0.09 on television). Substantively, moving from television to Facebook increases predicted economic framing by about 11 percentage points for the incumbent (≈ 0.09 to ≈ 0.20) and increases predicted anticorruption framing by about 6 points for the opposition (≈ 0.27 to ≈ 0.33). The leader role by platform interaction for Economic (versus Anticorruption) is statistically significant (p = 0.043), consistent with a crossover: incumbents tilt toward economic framing online, while the opposition concentrates on anticorruption online. The integration frame remains the incumbent’s dominant theme overall, with no meaningful platform shift in the predicted probabilities (Figure 3; Supplementary File 6, H3 Frames).

Conclusion (H3). These estimates provide partial support for H3. The anticipated emphasis of the opposition on anticorruption and the incumbent’s specific increase in economic framing are evident, but there is no systematic shift in integration across platforms. Integration nonetheless remains the leading incumbent frame.

4.4 Focus: policy versus character (H4)

The focus analysis investigates whether leaders prioritize policy or character differently across platforms, conditional on their role. H4 expects that policy-focused content to predominate overall, that character focused appeals would be relatively more common in opposition discourse, and that the platform would condition this difference. The analysis modeled policy versus character focus (policy = 1; character = 0) with binary logistic regression on the 339 statements with non-missing focus codes. Leader specific models assessed the association of platform (Facebook versus television) with the odds of policy focus, controlling for word count and campaign phase; a pooled model included leader role and the leader role × platform interaction. A pronounced asymmetry emerges. For the opposition, Facebook is associated with a sharp reduction in the odds of policy focus (odds ratio = 0.21, p < 0.001), indicating a shift toward personalized, character-oriented messaging on the challenger’s social feed. For the incumbent, the association points in the opposite direction: the point estimate suggests higher odds of policy focus on Facebook (odds ratio ≈ 2.15), but this effect falls short of conventional significance thresholds (p ≈ 0.08). In the pooled model, the leader role × platform interaction is large and significant (odds ratio ≈ 0.10, p < 0.001), confirming that the platform–focus link differs systematically by leader role.

Predicted probabilities (with controls set to their means) summarize the pattern: for the incumbent, policy focus is high on both platforms but somewhat higher on Facebook (≈0.88) than on television (≈0.78); for the opposition, policy focus is markedly lower on Facebook (≈0.63) than on television (≈0.90) (Figure 4; Supplementary File 7, H4 Focus). This pattern corresponds to about a 10-point increase in predicted policy focus for the incumbent when moving from television to Facebook (≈ 0.78 to ≈ 0.88) and about a 27-point decrease for the opposition (≈ 0.90 to ≈ 0.63).

Conclusion (H4). Policy focused appeals predominate overall, and platform differences in focus are clearly conditioned by leader role. On Facebook, opposition discourse becomes substantially more character focused, whereas the incumbent’s content tilts more toward policy, although this latter pattern is suggestive rather than statistically definitive. This configuration accords with hybrid media expectations: curated, leader-controlled channels facilitate record based messaging for incumbents, while engagement seeking dynamics encourage challengers’ personalized critique (Chadwick, 2013; Karvonen, 2010; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012).

4.5 Platform differences (H5)

H5 anticipated that platform logics would shape content. Pooled models reveal a consistent platform signature across outcomes.

Function: The pooled models link Facebook to a lower likelihood of attack relative to acclaim (log odds approximately −1.27, p < 0.001). Platform averaged predicted distributions were: television-Acclaim 0.469, Attack 0.496, Defense 0.035; Facebook-Acclaim 0.576, Attack 0.412, Defense 0.012. Thus, attacks were more likely on television, whereas acclaims were more likely on Facebook; defenses were rare overall and lowest on Facebook.

Tone: The pooled ordered logit model indicated a positive platform main effect (coefficient = +0.86, p = 0.007) alongside a negative leader role by platform interaction (coefficient = −1.51, p = 0.001), consistent with the role conditioned offsets documented in H2. Averaged across leader roles, the platform difference was modest: television-Negative 0.421, Neutral 0.082, Positive 0.497; Facebook—Negative 0.418, Neutral 0.072, Positive 0.511.

Frames: Platform averaged predictions showed the expected contrast: television-Conflict 0.246, Economic 0.182, Anticorruption 0.177, Integration 0.324; Facebook-Conflict 0.114, Economic 0.185, Anticorruption 0.209, Integration 0.336. Conflict was therefore higher on television, whereas anticorruption and integration were relatively more prominent on Facebook.

Focus: Platform averaged predictions indicated a lower probability of policy focus on Facebook (0.758) than on television (0.836), consistent with online personalization pressures. At the same time, the pooled leader role by platform interaction was large and significant (log odds approximately −2.35; odds ratio approximately 0.10; p < 0.001), mirroring H4’s role conditioned reversal (policy focus increases for the incumbent on Facebook and decreases for the opposition on Facebook).

Conclusion (H5). Overall, the results support H5. Relative to television, Facebook carries more acclaims, a slightly more positive overall tone (after averaging over leader-role off) sets and greater salience of anticorruption and integration frames, while television contains more attacks and more conflict framing. Crucially, these platform differences are not uniform: the leader role by platform moderator is central, with platform contrasts often amplified or reversed across incumbent and opposition discourse-consistent with hybrid media dynamics in polarized contexts (Chadwick, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014).

Finally, the analysis examined RQ2 by testing platform by campaign phase interactions. The analysis observed only modest late campaign increases in attacks and conflict framing on television; these temporal shifts did not alter the core leader role by platform patterns. In other words, platform differences remained largely stable over time, even as attacks and conflict marginally intensified late in the campaign (RQ2).

5 Discussion

This study examined how leader role and platform jointly shape campaign discourse across function, tone, frames, and focus in a hybrid media environment. The findings synthesize insights from functional theory, personalization, and hybrid media research and specify when and for whom platform differences materialize.

First, leader role asymmetries are fundamental. As predicted, defenses are rare, and the aggregate balance between acclaims and attacks reflects offsetting tendencies by incumbents and challengers (H1). Incumbents emphasize promotion and credit-claiming, whereas the opposition prioritizes contrast and critique-patterns consistent with functional theory and incumbency advantages in comparative work (Benoit, 2007, 2017; Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; Geer, 2024).

Second, the platform moderates these leader role strategies in systematic, leader role–conditioned ways. Facebook operates as a curation space for incumbents, supporting a more affirmative, policy-centered presentation, while the opposition uses the same channel to intensify attacks and personalization. By contrast, TV bears the imprint of journalistic gatekeeping and conflict news values, which elevate attacks and conflict-framed content relative to curated social feeds (H2, H5; Chadwick, 2013; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014; Klinger and Svensson, 2015; Stier et al., 2018). These results caution against attributing negativity or personalization to platforms per se; rather, platform effects depend on who speaks and where.

Continuity and change across electoral levels. Reading the 2025 parliamentary results alongside the earlier municipal case (Licenji, 2023) clarifies how this article extends prior Albanian evidence. The municipal study documented intensive candidate-controlled social media use and its association with engagement outcomes, while the present study maps cross-platform message content across television and Facebook under two leader roles. In the parliamentary campaign, the results indicate that leaders exert greater control over Facebook than television, consistent with the idea of social media as a curated channel, while television exposure remains shaped by journalistic selection and news values. At the same time, the parliamentary campaign features substantial salience of conflict and anticorruption cues. These observations are suggestive rather than a strict longitudinal comparison, but they help specify what may generalize across electoral levels (platform control incentives) and what may vary with election type and national-level stakes. Several mechanisms plausibly drive these role-conditioned platform shifts. Facebook grants leaders high message control and distribution autonomy relative to television, which allows incumbents to foreground governance performance, policy plans, and credit-claiming without journalistic interruption or adversarial questioning. The same controlled environment also supports selective self-presentation and supporter mobilization through curated issue emphasis and symbolic displays. Challengers often gain leverage on Facebook by mobilizing attention around leader-centered critique and by using attack-oriented posts that travel easily through interpersonal sharing and algorithmic ranking. Television imposes different incentives: journalistic gatekeeping, balance norms, and conflict news values raise the visibility of confrontation, which pushes discourse toward attacks and conflict cues even when leaders pursue other frames. Hybrid circulation across channels can further reinforce these incentives, because leaders can seed Facebook content that later appears on television and can clip television appearances for redistribution online.

Alternative explanations may also contribute. Campaign events and agenda shocks can shift tone and topic independent of platform logic; staffing decisions and message discipline can change within campaigns; and platform governance or engagement incentives may nudge communicators toward particular styles. The models control for campaign phase and message length, but the design cannot directly observe internal strategy decisions or platform ranking dynamics. These constraints encourage interpreting the estimates as systematic role-conditioned patterns rather than definitive causal effects of platform exposure.

Third, framing aligns with these logics. Television accentuates conflict whereas anticorruption and integration frames are relatively more prominent on Facebook after accounting for leader role (H3, H5). This configuration matches the dual pressures of integrity contestation by oppositions and credit-claiming by incumbents in Europeanizing contexts (Cappella and Jamieson, 1997; Elbasani, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). The expected platform shift in integration is not universal, however, underscoring that some frames are more leader role–anchored than platform-driven.

Finally, platform effects on tone and focus are conditional rather than uniform. Averaged across actors, Facebook tilts discourse slightly more positive, yet this masks a crossover: positivity rises for the incumbent and falls for the opposition (H2). An analogous asymmetry holds for focus: incumbents use Facebook to foreground policy rationales, whereas challengers shift toward leader-centered, character-focused critique (H4). In short, the same medium enables different strategic payoffs depending on incumbency status, clarifying why prior evidence on “social media negativity” and “personalization” appears inconsistent across cases (Karvonen, 2010; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Van Aelst et al., 2012). Phase probes indicate modest late-campaign increases in attacks and conflict on TV without reversing the core leader role × platform patterns (RQ2).

6 Conclusion

This article examined whether and how leader role and platform jointly structure campaign discourse in a hybrid media environment. Using a leader-constant, cross-platform design, it compared leader-authored communication on television and Facebook during Albania’s 2025 parliamentary campaign across four content dimensions: function, tone, frames, and focus.

6.1 Summary of findings

This study shows that leader role and platform jointly structure campaign discourse in a hybrid media environment. Across function, tone, frames, and focus, platform differences are not uniform: they often depend on whether the communicator is an incumbent or an opposition leader. The results are consistent with a role-conditioned pattern in which incumbents use Facebook more for affirmative, policy-oriented and record-based communication, while challengers use Facebook more for personalized critique, alongside television’s continued tendency to foreground conflict.

6.2 Contributions

The article contributes to research on campaign communication in three ways. First, it refines functional theory under hybrid media conditions by showing that platform effects are conditional on leader role rather than additive: the same platform affords different strategic repertoires depending on incumbency. Second, by integrating function, tone, framing, and focus within a single leader-constant, cross-platform design, the study links strands of scholarship that are often examined in isolation. Third, it extends comparative knowledge on campaigning in leader-centric and polarized contexts by mapping how candidate-controlled and mediated venues distribute credit-claiming, blame, and issue emphases across the campaign. Taken together, these contributions clarify why claims that “social media campaigns” are uniformly more negative or more personalized can be misleading: the same platform can support different strategic repertoires depending on whether the speaker is an incumbent or an opposition leader. For research on electoral behaviour and party competition, leader role therefore provides a key scope condition for interpreting cross-platform differences rather than treating them as platform-invariant traits.

6.3 Implications

The findings have implications for campaign politics, party strategy, and electoral competition, while also highlighting consequences for citizens’ information environments.

Electoral behaviour (information environments): If the opposition uses Facebook disproportionately for personalized critique and anticorruption attacks while incumbents use it for curated credit-claiming and policy presentation, voters’ perceptions may become more asymmetric and platform-dependent-with some audiences receiving primarily critical, character-centered narratives and others receiving primarily affirmative, policy-centered narratives. This fragmentation can matter for how voters evaluate responsibility and performance, and it may reinforce selective exposure and affective polarization, depending on which channel voters rely on most.

Campaign politics (hybrid-media repertoires): Practically, the results suggest that campaigns should treat platforms as parts of a role-specific communication portfolio rather than as interchangeable outlets. Candidate-controlled platforms can be used to consolidate a preferred narrative and manage tone, but television continues to operate under gatekeeping and conflict-oriented selection pressures that can elevate confrontation and conflict framing. In hybrid systems, strategic communication is therefore about designing cross-platform flows-what is seeded online, what is amplified on television, and how each venue is used to reach distinct audiences.

Party strategy and competition: The study highlights how party competition in leader-centered systems can be organized around distinct strategic packages: incumbents tend to pair credit-claiming with economy/integration narratives, while challengers pair critique with anticorruption and character-oriented appeals. This has implications for how parties pursue issue ownership and reputational competition, and for how oppositions attempt to overcome incumbency advantages in visibility and credibility. More broadly, the results suggest that competitive dynamics may intensify personalization online not because parties uniformly “go personal,” but because challengers, in particular, may find personal critique and anticorruption narratives especially advantageous in engagement-driven environments.

Across electoral behaviour, campaign practice, and party competition, the broader implication is that hybrid campaigning operates as a segmented portfolio rather than a simple “online vs. offline” divide. Platforms do not impose one campaigning style; instead, they enable role-specific allocations of rhetorical tasks (credit-claiming, critique, policy justification, character signalling). Assessments of democratic consequences, such as informational fragmentation, personalization, or antagonism-therefore need to consider not only which platform is used, but also which actors dominate that platform and for what strategic purposes.

6.4 Limitations and future research

This study’s leader-constant, cross-platform design strengthens inference about how the same political actors adapt campaign messages across television and Facebook, but several limitations qualify the conclusions and point to clear avenues for future research. First, the analysis covers one parliamentary election in a highly personalized and polarized setting and compares two principal leaders. While this provides strong leverage for within-leader cross-platform contrasts, it also limits generalizability and cannot fully disentangle leader-role effects (incumbent vs. opposition) from leader-specific communication styles. The findings should travel most readily to contexts that combine (a) leader-centered competition, (b) television’s continued reach and gatekeeping influence, and (c) Facebook’s role as a primary candidate-controlled channel. Party-centered systems with weaker personalization, coalition-oriented campaigns, or contexts where Instagram/TikTok dominate online campaigning may produce different role–platform dynamics and therefore require separate tests.

Second, the platform scope is restricted to television and Facebook. Hybrid-media campaigning increasingly spans multiple environments with distinct affordances (e.g., short-form video, remixability, influencer ecosystems), and these differences may alter the incentives for negativity, personalization, and frame selection. Future research should extend the design to additional platforms (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, YouTube) and explicitly examine cross-platform circulation, including how messages seeded on social media are amplified on television (or vice versa), and how platform-specific formats shape the balance between policy-oriented and character-centered appeals.

Third, the design is observational. Although the analysis documents systematic patterns consistent with hybrid-media expectations, it cannot conclusively attribute differences to platform “logics” rather than to campaign-event timing, agenda shocks, strategic decisions by campaign staff, or platform pressures and ranking dynamics. Event-study approaches around exogenous shocks, quasi-experimental comparisons, and survey/field/online experiments could increase causal leverage on when and why leaders shift between acclaims, attacks, defenses, and frames across venues.

Fourth, the study maps communication strategies but does not assess persuasive effectiveness. Content patterns show how leaders allocate functions, tone, frames, and focus across platforms, but claims about “what works” require outcome data linking content to exposure and voter response. Future work could connect message features to (a) exposure and engagement metrics, and (b) electoral indicators such as time-varying poll series, prediction markets, or validated behavioural measures, while modelling potential feedback loops among candidates, media attention, and voters (Kübler et al., 2025).

Fifth, temporal generalizability remains an open question. The 2025 parliamentary campaign offers a snapshot under conditions of high polarization and mature Facebook penetration; earlier or later contests may shift the balance across functions, frames, and tone as parties respond to changing stakes and evolving platform environments. Extending the design to multiple Albanian elections (municipal and parliamentary) and to additional countries would strengthen external validity, clarify whether role-conditioned platform patterns persist over time, and reduce leader-specific confounds.

Finally, measurement constraints should be acknowledged. Human coding and reliability procedures mitigate but do not eliminate measurement error, and rare categories (notably defenses) reduce statistical power for some contrasts. A complementary robustness and scaling extension would triangulate the deductive coding scheme with inductive text-as-data approaches. Because unsupervised methods (e.g., topic models) group language by co-occurrence rather than by framing logic, they may recover different issue clusters than theory-driven frame categories (Grimmer and Stewart, 2013). Combining manual coding with computational models would allow direct comparison between inductive topics and the deductive frame set and would enable scaling to larger, multi-election corpora.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study have been deposited in Zenodo and will be made publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18375319 upon publication of the article. Replication files (analysis code and supporting materials) will be available in the same repository. Additional supporting materials are included in the article’s Supplementary material (Supplementary Files 1–6, 9). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the invaluable contribution of the two native-language coders, whose careful work in developing the codebook and coding the corpus greatly improved the quality of the dataset. Any remaining errors are the author’s own.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2026.1754813/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary FILE 1Variable definitions and coding scheme. Variable definitions, coding scheme, and measurement levels for all outcomes, focal predictors, moderators, and controls used in the analysis. The table reports category labels, coding decisions, and the hypotheses in which each variable is employed.

Supplementary FILE 2Descriptive statistics by leader role and platform. Descriptive statistics for message function, tone, primary frame, and focus, disaggregated by leader role (incumbent vs. opposition) and platform (television vs. Facebook). Entries report observed proportions within each leader–platform cell.

Supplementary FILE 3Distribution of message functions (H1). Distribution of campaign message functions (acclaim, attack, defense) in the pooled corpus and by leader role. Results correspond to Hypothesis 1 and illustrate the baseline structure of campaign discourse prior to conditioning on platform.

Supplementary FILE 4Leader role × platform effects on message function and tone (H2). Multinomial logit (function) and ordered logit (tone) estimates testing leader role × platform interactions. The table reports coefficients and standard errors for Hypothesis 2; substantive effects are interpreted using predicted probabilities shown in Figures 2a–c.

Supplementary FILE 5Leader role × platform effects on framing (H3). Multinomial logit estimates of primary frame choice (conflict, economic, anticorruption, integration, none/other) by leader role, platform, and their interaction.

Supplementary FILE 6Leader role × platform effects on focus (policy vs. character) (H4). Binary logit estimates of message focus (policy = 1, character = 0) by leader role, platform, and their interaction. Results correspond to Hypothesis 4 and demonstrate role-conditioned reversals in platform effects; predicted probabilities are reported in Figure 4.

Supplementary FILE 7Platform-averaged effects across outcomes (H5). Platform-averaged model estimates comparing television and Facebook across message function, tone, framing, and focus. Results test Hypothesis 5 and summarize general platform signatures prior to conditioning on leader role.

Supplementary FILE 8Predicted probabilities by leader role × platform. Model-based predicted probabilities for message function, tone, primary frame, and focus by leader role and platform, holding controls at their observed means. This table provides the substantive interpretation of the interaction effects reported in Tables 4–6.

Supplementary FILE 9Robustness checks and alternative specifications. Robustness checks for all main models, including alternative baselines, clustered standard errors, and sensitivity to specification choices. The table confirms that the substantive conclusions are stable across model variants.

References

1

Agresti A. (2002). Categorical data analysis. 2nd Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

2

Akaike H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control19, 716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

3

Alonso-Muñoz L. Casero-Ripollés A. (2023). The appeal to emotions in the discourse of populist political actors from Spain, Italy, France and the United Kingdom on twitter. Front. Commun.8:1159847. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1159847

4

Benoit W. L. (2007). Communication in political campaigns. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

5

Benoit W. L. (2017). Meta-analysis of research on the functional theory of political campaign discourse. Speaker Gavel54, 7–50.

6

Benoit W. L. Sheafer T. (2006). Functional theory and political discourse: televised debates in Israel and the United States. Polit. Commun.23, 273–294. doi: 10.1080/10584600600808919

7

Blumler J. G. Kavanagh D. (1999). The third age of political communication: influences and features. Polit. Commun.16, 209–230. doi: 10.1080/105846099198596

8

Bossetta M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: comparing political campaigning on Facebook, twitter, Instagram, and snapchat in the 2016 U.S. election. J. Mass Commun. Q.95, 471–496. doi: 10.1177/1077699018763307

9

Brant R. (1990). Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics46, 1171–1178. doi: 10.2307/2532457,

10

Cameron A. C. Miller D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster robust inference. J. Hum. Resour.50, 317–372. doi: 10.3368/jhr.50.2.317

11

Cappella J. N. Jamieson K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: the press and the public good. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

12

Chadwick A. (2013). The hybrid media system: politics and power. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

13

de Vreese C. H. (2005). News framing: theory and typology. Inf. Des. J.13, 51–62. doi: 10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre

14

Elbasani A. (2013). European integration and transformation in the Western Balkans: Europeanization or business as usual?London, UK: Routledge.

15

Elmelund-Præstekær C. (2010). Beyond American negativity: toward a general understanding of the determinants of negative campaigning. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev.2, 137–156. doi: 10.1017/S1755773909990269

16

Enli G. S. Skogerbø E. (2013). Personalized campaigns in party-centred politics: twitter and Facebook as arenas for political communication. Inf. Commun. Soc.16, 757–774. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330

17

Entman R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun.43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

18

Esser F. Strömbäck J. (2014). Mediatization of politics: understanding the transformation of Western democracies. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

19

Fisher R. A. (1922). On the interpretation of χ2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc.85, 87–94.

20

Galtung J. Ruge M. H. (1965). The structure of foreign news: the presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. J. Peace Res.2, 64–91. doi: 10.1177/002234336500200104

21

Geer J. G. (2006). In defense of negativity: attack ads in presidential campaigns. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

22

Geer J. G. (2024). In defense of negativity (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

23

Geise S. Maubach K. (2024). Catch me if you can: how episodic and thematic multimodal news frames shape policy support by stimulating visual attention and responsibility attributions. Front. Commun.9:1305048. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1305048

24