While conventional wisdom argues that mass popular uprisings in authoritarian or hybrid regimes usually do not lead to veritable democratization, their aftermath is rarely a clear-cut return to the status quo ante or a decisive move to a new system of government, but rather a longer transitional period that is both politically ambiguous and in flux. Revolutionary moments provoke a range of impacts on institutional, relational, and normative-symbolic dynamics that allow for different outcomes—democratic gains and authoritarian reassembly—to occur simultaneously. Assessing the relationship between mass popular uprising and democratization thus requires taking a more nuanced, longitudinal approach that registers smaller-scale changes on a continuum of democracy-autocracy.

The articles in this Research Topic, stemming from the Horizon-Europe funded research consortium EMBRACE (“EMBRACing changE: Overcoming obstacles and advancing democracy in the European Neighbourhood”),1 seek to shed light on how diverse popular uprisings can lead to democratization by focusing on how bottom-up actors do or do not achieve smaller-scale democratic gains in the aftermath of mass mobilization. Building on the literature lying at the nexus of contentious politics, revolutionary theory, and democratization studies, we argue that post-uprisings periods are analytically relevant contexts that shape the opportunities and constraints for smaller-scale shifts that, longer-term, can aggregate to foster either democratic consolidation or authoritarian reversal. Taken together, these articles present one of the first efforts to systematically compare micro-level post-revolutionary democratization/autocratization processes in the European neighborhood.

Theorizing popular uprisings and reconfiguration

The theoretical point of departure for this Research Topic is the popular uprising itself and its processual, relational, and interactionist fluidity and ambiguity. We draw on the conceptual framework of Dobry (1983, 1986) and his theorizing of political crises as processes of multisectoral mobilization, or the simultaneous deployment of collective action by different sectors of the polity. For Dobry, multisectoral mobilization is characterized by fluidity in social relations along three dimensions: the unification of social space, the enlarged tactical interdependence of sectors (understood as sociopolitical networks and social groups), and structural uncertainty (Dobry, 1983, p. 409). New resources and political opportunities become available, and strategic interactions become unpredictable and highly contingent. This creates a complex chain of moves/counter-moves that are unbounded by normal structuring logics of action, alliance, and political possibility.

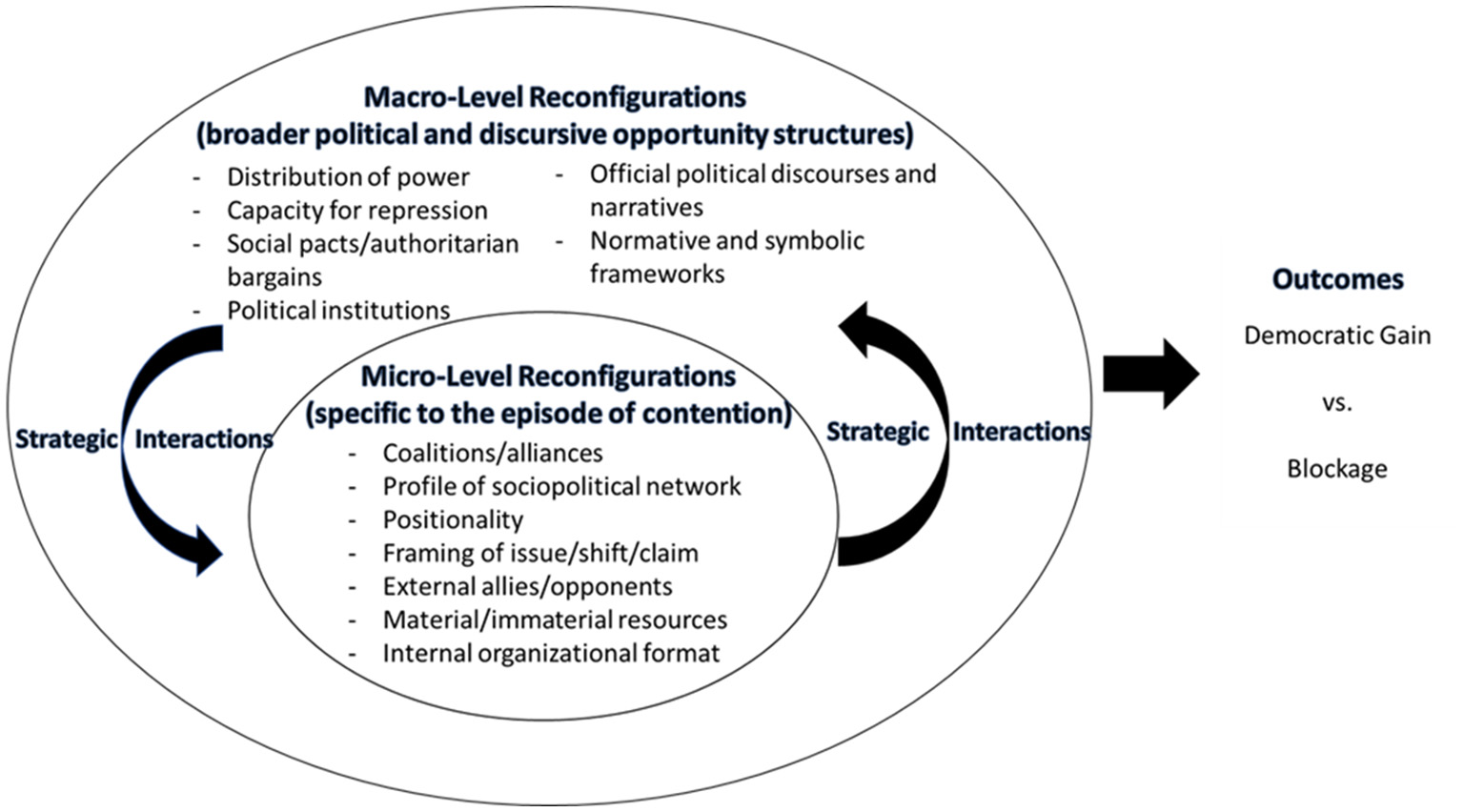

In conceiving popular uprisings and their aftermath, before the political order fully settles, as processes of multisectoral mobilization, our theoretical argument puts forth a concept of reconfigurations in institutional, relational, and discursive-symbolic terms. This concept draws from Ouaissa et al. (2021), in which reconfigurations are understood as dynamic change processes in political, economic, social, and cultural relations during and in the aftermath of uprisings. We argue that reconfigurations create possibilities for action/interaction that can be conflictual and/or cooperative, acting thus as the conditions that lead to either political openings or blockages. The reconfigurations, hence, act as both structures but are also shaped/re-shaped by interactions, implying a relational ontology. In this way, reconfigurations can both enable and block political change, acting as conditions underlying episodes of contentious politics that are not static but rather shaped and reshaped by strategic interactions. In this way, our approach (Figure 1) posits that the institutional, relational, and discursive fluidity of popular uprisings produce conditions for small-scale democratic advancement and set-back that must be placed in a longer-term and wider perspective in the evaluation of political outcomes.

Figure 1

Micro- and macro-level reconfigurations in post-uprising contexts.

Overview of the Research Topic

Building on ongoing discussions in this journal (Grimm et al., 2023), each article gathered here explores the mobilization efforts of social forces or bottom-up actors vying for changes or reforms that, contextually, can be characterized as democratic in nature. In his article on bottom-up anti-corruption reform efforts in the aftermath of the Georgian Rose Revolution, Aprasidze reveals how civil society actors were able to leverage institutional flux, positioning themselves within the new administration to push their reform agendas forward. Similarly, in their study comparing anti-corruption and judicial reform efforts on the part of bottom-up actors in Armenia following the Velvet Revolution, Paturyan et al. demonstrate how civil society actors with well-established expertise were able to influence reforms and contribute to democratic institution-building when they could be directly inserted in policy-making process, assuming a role of policy entrepreneurship. What these articles show is how political fluidity and reconfigured relations between authorities and bottom-up actors can allow well-trained, structured, and experienced civil society to lock in small-scale democratic gains by acting as both intermediaries and key policy advocates within post-revolutionary administrations.

However, in her study of broad mobilization advocating for transitional justice mechanisms in the aftermath of the 2011 Tunisia Revolution, Jmal finds that the need for “technical expertise” can also create exclusionary mechanisms. As she finds, while bottom-up actors, organized in a coordinated vertical coalition able to deploy pressure and resources at different levels, were quite successful in shaping the transitional justice approach initially, they ultimately found themselves sidelined and their vision replaced by politically expedient solutions. This finds echo in the case North Macedonia's 2015 mass mobilization, as investigated by Armakolas and Krstanovska. As they relate, while grassroots student movements and CSOs, organized in a broad horizontal coalition, were able to successfully mobilize to instigate democratic openings, the absence of defined organizational structures and the influence of European Union mediation of the transition—which prioritized quick agreements among political elites—ultimately reversed initial efforts at direct democratic inclusiveness.

This dynamic of fragmentation and its negative effect on securing democratic gains among mobilized bottom-up actors is also clearly visible in the contribution by Rennick and Žilović, which compares labor market contestation in Tunisia and Serbia. As they find, mobilization for market inclusion was able to be assuaged through piecemeal gestures; while such limited concessions effectively managed contestation—helping to stabilize the democratic transitions—they also contributed to organizational break-down and the inability to advance broader reform efforts. Likewise, in their article on violent repression of LGBTQI+ mobilization for equal rights during the Belgrade 2001 Pride parade, Vranić and Ilić find that fragmentation and internal struggles within the community, as well as the anti-nationalist and pro-democracy framing of their claims, both undermined the solidity of the coalition and limited the potential for collaboration with authorities. This resulted in significant setbacks to the advancement of identity rights in Serbia in the subsequent two decades. The final article of the Research Topic considers a more recent episode of social mobilization and its link to democratic gains. In her article on the mass protests calling for political resignations following tragic school shootings in Belgrade in May 2024, Jevtić observes the role of a polarized media landscape in the cadence and impact of the movement, but also, more broadly, instrumentalized political mobilization. She finds that the effectiveness of protestors depended more on the polarized media narratives than on the sheer size of demonstrations.

Taken together, the empirical studies here present compelling evidence of the continuous contests led by bottom-up actors over the direction and nature of political transition, even after mass mobilization recedes into the background. Collectively, the articles contribute to the literature linking popular uprising and democratic transition in two ways. First, we proffer an analytical framework that moves away from the transition process itself and path-dependent macro-structural features and offer new insights on the relational and interactionist dynamics underpinning the link between mass popular uprising and transitional outcomes. Second, in gathering empirical studies across different regime types and socio-cultural contexts, and notably the comparison between different European neighborhood democratization trajectories, we argue for a move away from typologies of popular uprising and demonstrate instead that contextual features of post-uprising transitional periods have explanatory power.

Statements

Author contributions

SR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The paper is part of the Horizon research project Embracing Change: Overcoming obstacles and advancing democracy in European Neighbourhood (EMBRACE) funded by the EU (Grant agreement: 101060809).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^More on EMBRACE can be found on https://embrace-democracy.eu/.

References

1

Dobry M. (1983). Mobilisations mulitsectorielles et crises politiques: un point de vue heuristique. Rev. Franç. Sociol.24, 395–419.

2

Dobry M. (1986). Sociologie des Crises Politiques: la Dynamique des Mobilisations Multisectorielles. Paris: Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques.

3

Grimm S. Hellmeier S. Dollbaum J. M. Dudouet V. (2023). Editorial: Pro-democracy movements in a comparative perspective. Front. Polit. Sci.5:1141635. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1141635

4

Ouaissa R. Pannewick F. Strohmaier A. (2021). Re-Configurations: Contextualising Transformation Processes and Lasting Crises in the Middle East and North Africa. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer.

Summary

Keywords

autocratization, bottom-up, contentious politics, democratization, mobilization, revolution

Citation

Rennick SA and Vranić B (2026) Editorial: Configurations for democratic, economic and policy shifts after popular uprisings in European neighbourhood. Front. Polit. Sci. 8:1776012. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2026.1776012

Received

26 December 2025

Accepted

20 January 2026

Published

06 February 2026

Volume

8 - 2026

Edited and reviewed by

Andrea De Angelis, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Rennick and Vranić.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Anne Rennick, s.rennick@arab-reform.net; Bojan Vranić, bojan.vranic@fpn.bg.ac.rs

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.