- 1Department of Physiological Psychology, University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany

- 2Center of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology, University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany

A commentary on

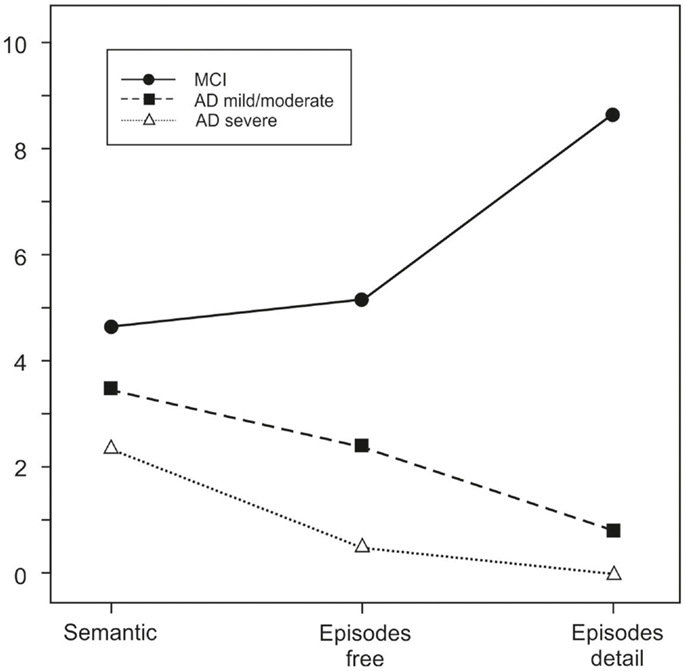

Memory is the key to our life. Already in 1870, the famous physiologist Hering (1) stated in a booklet that memory “connects innumerable single phenomena into a whole, and just as the body would be scattered like dust in countless atoms if the attraction of matter did not hold it together so consciousness – without the connecting power of memory – would fall apart in as many fragments as it contains moments” (p. 12; my translation). With this statement, he emphasized that healthy human beings are able to mentally travel in time and that in their presence they can learn from their past to find optimal solutions for their future. It is known that this capacity needs time, brain maturation, and the establishment of an autonomous self (including theory of mind abilities and the ability to show empathy) in order to develop and persist (2). Adults consequently cannot consciously remember events that had occurred prior to the age of 3–4 years (3–6). On the other hand, in dementia the ability to travel back in time deteriorates and then gets lost totally (7). The deterioration of episodic–autobiographical memory [cf. the Figure in Ref. (8), or Figure 3 in Ref. (9)] is accompanied by a reduction in emotional colorization of retrieved events – the descriptions become more fact-like, are less detailed, and are reproduced without corresponding affect (10) (Figure 1). The reduced emotional impact on behavior in old people extends to a number of everyday situations (11) and may lead to retrieval deficits especially in situations guiding retrieval.

Figure 1. Production of semantic and episodic–autobiographical details in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD mild/moderate), and severe Alzheimer’s disease (AD severe). Data from Seidl et al. (10).

The interaction between memory and emotion across the life span was the topic of a nicely designed experiment by Kinugawa et al. (12). A “what, where, and when” paradigm was used that allowed measuring content and temporal and spatial context of an event by combining the presentation of visual scenes with a context story with an emotionally arousing content. Participants were divided into three groups of 17, 16, and 8 volunteers with mean ages of 27, 55, and 79 years, and tested with this paradigm. The principal outcome was that the old compared to the young group was poorer in recall and had in addition a lower working memory performance and less anxiety as measured by state and trait anxiety scales. These results add to a number of related ones, demonstrating that older people recruit more brain regions to perform a given task (13), have a less sharp differentiation between explicit and implicit memory processing (14), and perceive life processes as speeding up with age (15). Furthermore, it was found that old people have a higher tendency to forget negative emotional memories, compared to positive or neutral ones (16).

Already in the year 2005, Drachman (17) in an editorial highlighted the manifold brain changes in the elderly (e.g., neuronal loss, white matter loss, volume shrinkage, sulcal widening, reduction of synaptic density), which probably account for the intellectual decline found with increasing age. Drachman wrote: “Using the standard age correction for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), to obtain an IQ score of 100 at age 75, one need to answer only half as many questions correctly as at age 21!” (p. 2005). Though the neuronal and intellectual decline may not be universal (18), it still affects the great majority of old people (19). Conventional mental training may be a much less effective counteractive treatment (20) than physical exercise (21, 22). The new episodic memory task proposed by Kinugawa et al. might nevertheless be apt to induce new attempts not only to assess, but also to train memory in older people. The authors themselves suggest a number of possible approaches for future research in this direction.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Hering E. Ueber das Gedächtnis als eine allgemeine Funktion der organisierten Materie. Vortrag gehalten in der feierlichen Sitzung der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien am XXX. Mai MDCCCLXX. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft (1870).

2. Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A. Memory, autonoetic consciousness, and the self. Conscious Cogn (2011) 20:16–39. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.005

3. Harpez-Rotem I, Hirst W. The earliest memory in individuals raised in either traditional and reformed Kibbutz or outside the Kibbutz. Memory (2005) 13:51–62. doi:10.1080/09658210344000567

4. Wang Q. Culture effects on adult’s earliest childhood recollection and self-description: implications for the relation between memory and the self. J Pers Soc Psychol (2001) 81:220–33. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.220

5. Peterson C, Hou Y, Wang Q. “When I was little”: childhood recollections in Chinese and European Canadian grade school children. Child Dev (2009) 80:506–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01275.x

6. Bauer PJ, Larkina M. Childhood amnesia in the making: different distributions of autobiographical memories in children and adults. J Exp Psychol Gen (2014) 143:597–611. doi:10.1037/a0033307

7. Hehman JA, German TP, Klein SB. Impaired self-recognition from recent photographs in a case of late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Cognit (2005.) 23:118–24. doi:10.1521/soco.23.1.118.59197

8. Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A. Amnesic disorders. Lancet (2012) 380:1429–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61304-4

9. Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A. Autonoetic consciousness and the self. In: Cavanna AE, Nani A, editors. Consciousness: States, Mechanisms and Disorders. New York: Nova Science Publishers (2012). p. 85–110.

10. Seidl U, Markowitsch HJ, Schröder J. Die verlorene Erinnerung. Störungen des autobiographischen Gedächtnisses bei leichter kognitiver Beeinträchtigung und Alzheimer-Demenz. In: Welzer H, Markowitsch HJ editors. Warum Menschen sich erinnern können. Fortschritte in der interdisziplinären Gedächtnisforschung. Stuttgart: Klett (2006). p. 286–302.

11. Brand M, Markowitsch HJ. Aging and decision making: a neurocognitive perspective. Gerontology (2010) 56:319–24. doi:10.1159/000248829

12. Kinugawa K, Schumm S, Pollina M, Depre M, Jungbluth C, Doulazmi M, et al. Aging-related episodic memory decline: are emotions the key? Front Behav Neurosci (2013) 7:2. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00002

13. Berlingeri M, Danelli L, Bettini G, Sherna M, Paulesu E. Reassessing the HAROLD model: is the hemispheric asymmetry reduction older adults a special case of compensatory-related utilisation of neural circuits? Exp Brain Res (2013) 224:393–410. doi:10.1007/s00221-012-3319-x

14. Dennis NA, Cabeza R. Age-related dedifferentiation of learning systems: an fMRI study of implicit and explicit learning. Neurobiol Aging (2010) 32:2318.e17–30. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.004

16. Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: the forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J Exp Psychol Gen (2003) 132:310–24. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310

17. Drachman DA. Do we have brain to spare? Neurology (2005) 64:2004–5. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000166914.38327.BB

18. den Dunnen WA, Brouwer WH, Bijard E, Kamphuis J, van Linschoten K, Eggens-Meijer E, et al. No disease in the brain of a 115-year-old woman. Neurobiol Aging (2008) 29:1127–32. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.010

19. Whittle C, Corrada MM, Dick M, Ziegler R, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Paganini-Hill A, et al. Neuropsychological data in nondemented oldest old: the 90+ study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol (2007) 29:290–9. doi:10.1080/13803390600678038

20. Owen AW, Hampshire A, Grahn JA, Stenton R, Dajani S, Burns AS, et al. Putting brain training to a test. Nature (2010) 465:775–9. doi:10.1038/nature09042

21. Anderson BJ, Greenwood SJ, McCloskey D. Exercise as an intervention for the age-related decline in neural metabolic support. Front Aging Neurosci (2010) 2:30. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2010.00030

Keywords: empathy, autobiography, time, neuronal changes, intellect

Citation: Markowitsch HJ (2014) Memory, emotion, and age: the work of Kinugawa et al. (2013). Front. Psychiatry 5:58. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00058

Received: 28 April 2014; Paper pending published: 11 May 2014;

Accepted: 12 May 2014; Published online: 27 May 2014.

Edited and reviewed by: Carmen Sandi, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright: © 2014 Markowitsch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:aGptYXJrb3dpdHNjaEB1bmktYmllbGVmZWxkLmRl

Hans J. Markowitsch

Hans J. Markowitsch