- 1Department of Social and Community Health, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

- 2Māori Studies and Pacific Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Background and Objectives: The intergenerational impacts of parental exposure to violence during childhood and adulthood have largely been investigated separately. This limits our understanding of how cumulative violence exposure over a lifespan elevates the risk of subsequent generation's maladjustment. To address this, we examined if parental exposure to violence during childhood and during adulthood was associated with increased emotional-behavioural and school difficulties among the children of these parents. Further, we examined if parental exposure to cumulative violence increased the odds of their children experiencing difficulties.

Participants and Setting: 705 participants (354 mothers and 351 fathers) from the 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey, a population-based study conducted in New Zealand between March 2017 and March 2019.

Methods: Multivariable logistic regressions were conducted to ascertain the impact of parental exposure to violence on children's outcomes after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics. The impact of parental cumulative violence exposure on children's outcomes was also explored.

Results: Findings indicated that children of parents who had histories of exposure to violence during childhood were at increased risk for experiencing emotional-behavioural or school difficulties. However, where parents reported a history of childhood abuse but not adult experience of violence, their children had similar odds of experiencing difficulties as the children of parents who had not been exposed to any violence in their lifetime. Children of parents who had been exposed to violence only during adulthood were at higher risk of experiencing emotional-behavioural difficulties compared with children of parents with no violence exposure. Children of parents with histories of exposure to violence during both childhood and adulthood had the highest prevalence of experiencing emotional/behavioural and school difficulties.

Conclusion: These findings highlight the intergenerational impacts of violence exposure and the complex intersections between parents' and children's life experiences. Our findings suggest the need for violence prevention initiatives to foster the development of safe, stable and nurturing relationships and to expand services for parents already exposed to violence to build resilience and to break the inter-generational cycle of disadvantage.

Introduction

Intergenerational impacts of violence exposure refer to how parental exposure to violence during childhood or adulthood affects their children. Research in this area has often focussed on childhood exposure as a risk factor for later risk of violence perpetration (often called “intergenerational transmission” of violence). However, there is also a need to investigate other intergenerational impacts that may occur. Research has shown that the consequences of childhood exposure to violence affects people's social, economic, and physical chances throughout the lifespan (1), and may lead to multiple and complex experiences of disadvantage, including higher likelihood of repeat victimisation and exposure to violence in adulthood (2, 3).

Additionally, there is evidence that childhood exposure to violence can create negative outcomes for successive generations (4). For example, it has been documented that parental exposure to violence during childhood has implications for their later parenting practices (5). Similarly, parent's exposure to violence during adulthood is associated with adverse outcomes for their children. For example, intimate partner violence (IPV), one of the most common forms of violence, has negative consequences not only for individuals subjected to violence but also for children of those affected (6). This includes negative effects on children's intellectual (7) emotional, behavioural and social development (6), as well as on their academic performance (8). Most studies exploring intergenerational impacts of violence have explored the effects of parent's exposure to IPV, but fewer have examined how parent's exposure to violence by non-partners impacts on their children. As with IPV, non-partner violence can include physical or sexual violence, and can be perpetrated by a range of individuals, including other family members (non-partners), acquaintances or strangers.

Further, the intergenerational impacts of parental exposure to violence during childhood and adulthood have largely been investigated separately (9). This has limited our understanding of how cumulative violence exposure over a lifespan elevates the risk of subsequent generation's maladjustment. The limited research that has been conducted on intergenerational impacts suggests that parental exposure to violence as a child along with IPV exposure as an adult exacerbates the likelihood of negative outcomes for subsequent children. Another gap in the literature is that the majority of research on adult exposure to violence has either focused on the effects of IPV on the mothers as victims and fathers as perpetrators and the outcomes for their children (9). At present, there is a paucity of evidence exploring how fathers' experience of violence impacts on their children. While both men and women can be victims as well as perpetrators, differences between men's and women's experiences of violence have been noted. For example, women are more likely to experience physical and mental health problems as the consequence of violence exposure than men (10, 11). Male-perpetrated IPV has also been shown to be more injurious for women and result in more severe short and long term sequalae (12). Consequently, women are also more likely to be killed as a result of IPV (13, 14).

The field would also benefit from additional exploration of intergenerational impacts beyond consideration of children's externalising and internalising problems, two of the most consistently documented factors related to parental exposure to violence (5, 14, 15). More specifically, the impact of parental exposure to violence on children's educational outcomes is understudied and less understood (5, 16, 17). Finally, critical reviews have called attention to methodological limitations of research in this field (12), such as the fact that most studies on violence exposure are drawn from service data (e.g., from clients accessing mental health services or child protective agency records). These samples represent only a proportion of violence exposure, i.e., include only cases that comes to the attention of the authorities (13), so their results may not be generalizable to the whole population or to unreported cases of abuse. Data from population-based samples are required to further validate these findings.

Current Study

Using data from a large population-based study in New Zealand we examine if parental exposure to violence during childhood and during adulthood (violence by an intimate partner and/or a non-partner) is associated with increased levels of emotional-behavioural and school difficulties among the children of these parents. Further, we examine if parental exposure to cumulative violence increases the odds of their children experiencing difficulties.

Materials and Methods

The data reported are from the 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey/He Koiora Matapopore, a population based study conducted in three regions (Waikato, Northland and Auckland) in New Zealand between March 2017 and March 2019. Full details of the study methods are published elsewhere (15) but are summarised briefly here. Eligibility requirements for participants were: age 16 years and over, speaking conversational English, sleeping in the property at least four nights a week on average and living at the property for at least 1 month prior to data collection. Both women and men were recruited for the study.

Sampling Method

Meshblocks (the smallest geographical unit used for census surveys) were selected by Stats NZ. Within each meshblock, a random starting point was identified and every second and sixth house within the meshblock was selected. Non-residential and short-term residential properties, rest homes and retirement villages were excluded. Specific meshblocks were allocated to each gender for safety reasons. In addition, only one randomly selected person per household could participate in the study.

Data Collection

Data was collected through face-to-face interviews using the WHO Multi-Country Study on Violence Against Women (VAW) questionnaire (16). The instrument was adapted to include men and was pre-tested with a convenience sample before the actual data collection started. Questions on childhood exposure to violence was taken from the Adverse Childhood Experience study questions used by the USA Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (17). Comprehensive training of all interviewers was conducted to ensure valid data collection and the safety of interviewers and respondents. For quality assurance purposes regular meetings, audits and reviews of completed interviews were conducted. Interviews were conducted privately with no one aged 2 years or over present. All respondents provided written consent prior to interview.

Study Sample

The final sample size for the 2019 New Zealand family violence study was 2,887 and consisted of 1,423 men and 1,464 women who completed interviews. Those who agreed to participate represented over 60% of eligible individuals (63.7% women, 61.3% men).

Representativeness

The ethnicity, marital status, average personal income, and deprivation level distribution of the original sample were closely comparable to the general population, however, the sample was under-represented for younger respondents (ages 16–29) and slightly over-represented for those over 60 years of age (15).

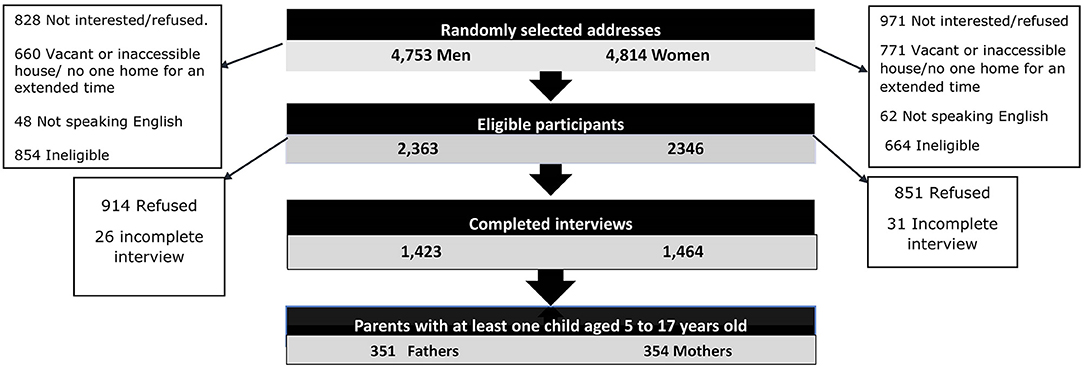

This study uses data from 354 women (mean age = 42.0 years, SD = 7.0) and 351 men (mean age = 45.1 years, SD 7.4) who had at least one child aged 5–17 years old at the time of interview. Figure 1 documents households approached, contacted and the recruitment outcomes at the individual level. Demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2.

Measures and Variables

Information on children's emotional-behavioural and school difficulties were collected from the parent (respondent) only. Respondents were instructed to consider their children aged 5–17 years when answering questions concerning children's outcomes.

Main Outcomes of Interest

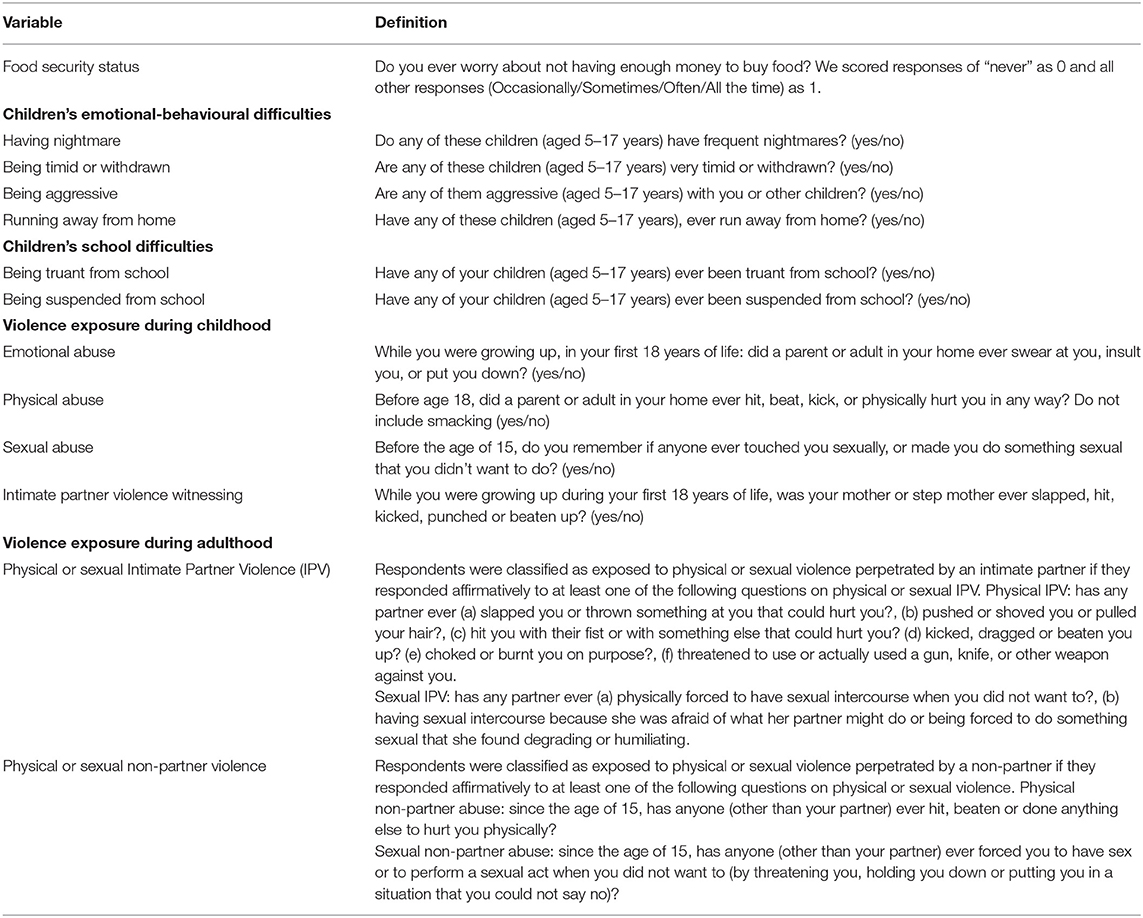

The main outcomes of interest for the current study were child emotional-behavioural and school difficulties reported by their parents (respondents). To measure emotional/behavioural difficulties, four items were used: child emotional difficulties (two items): having nightmares; being timid or withdrawn; and child behavioural difficulties (two items): being aggressive; running away from home. A binary variable was created to measure child experience of any emotional-behavioural difficulties (any / none). Two items were used to measure school difficulties: being truant; being suspended from school. A binary variable was created to measure child's school difficulties (any/none). Don't know or can't remember were treated as missing data. Exact questions wording and response options are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Definition of food security, children's emotional-behavioural and school difficulties, and parental violence exposure during childhood and adulthood, the 2019 family violence study.

Exposures of Interest

The main exposure variables in the current investigation were parental exposure to violence during childhood and adulthood. In this study, we defined exposure to violence during childhood as being directly subject to violence or being exposed to violence against their mother/stepmother. Based on this, exposure to four types of violence during childhood were included: direct experience of psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse and witnessing IPV against mother or step-mother. A binary variable called CAN (child abuse and neglect) was created to measure any violence exposure during childhood vs. none.

Exposure to violence during adulthood included exposure to two types of violence: physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner (IPV) and physical and or sexual violence by a non-partner. A binary variable was created to measure any physical or sexual violence exposure during adulthood vs. none (Table 1).

Cumulative violence exposure was defined by combining the two derived binary variables (exposure to at least one type of violence during childhood and exposure to at least one type of violence during adulthood). Four groups were defined: those with no violence exposure during childhood and adulthood, those with violence exposure only during childhood, those with violence exposure only during adulthood, and those with violence exposure during both childhood and adulthood.

Socio-demographic Factors

Sociodemographic variables were used to explore prevalence rates of reported child emotional-behavioural and school difficulties among sub-populations and as potential confounders in the multivariable analyses (18–21). These variables included parental ethnicity (European, Māori, Pacific, Asian, MELAA [Middle East or Latin American or African]) and food security status (secure, insecure). Since there were too few MELAA respondents who had children aged 5–17 (n = 4 women and n = 7 men), this ethnic group was dropped from the analyses. The definition for food security status is presented in Table 1.

Analytic Procedure

Analyses were conducted with Stata 15 SE (22). In all analyses, the complex sampling design has been allowed for through use of the Survey Data Analysis programs in Stata/SE, which allows for stratification by sample location (region), clustering by PSUs, and weighting of data to account for the number of eligible participants in each household.

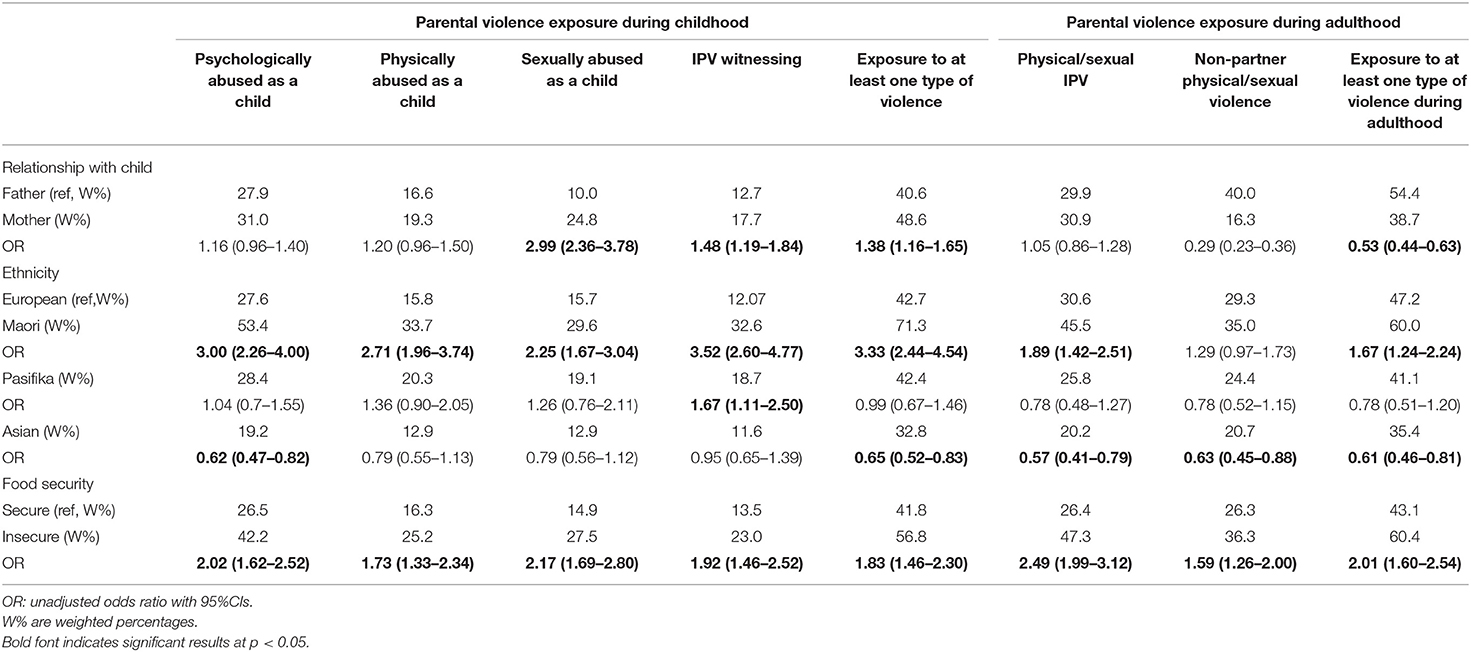

Descriptive statistics including frequency and weighted percentages were reported for the outcome variables (parental report of child's emotional-behavioural and school difficulties) and for each parental socio-demographic and violence exposure variable for the study sample (Tables 2, 3). Prevalence rates (weighted percentages) of the outcome variables were also estimated across socio-demographic sub-groups (gender, ethnicity, food security status) and violence exposure variables (Table 2). Univariate logistic regression was used to investigate association between (a) parental socio-demographic characteristics and reports of child outcomes, (b) parental report of violence exposure during childhood and adulthood and child outcomes, and (c) parental report of violence exposure during their childhood and their adulthood. Odds ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals.

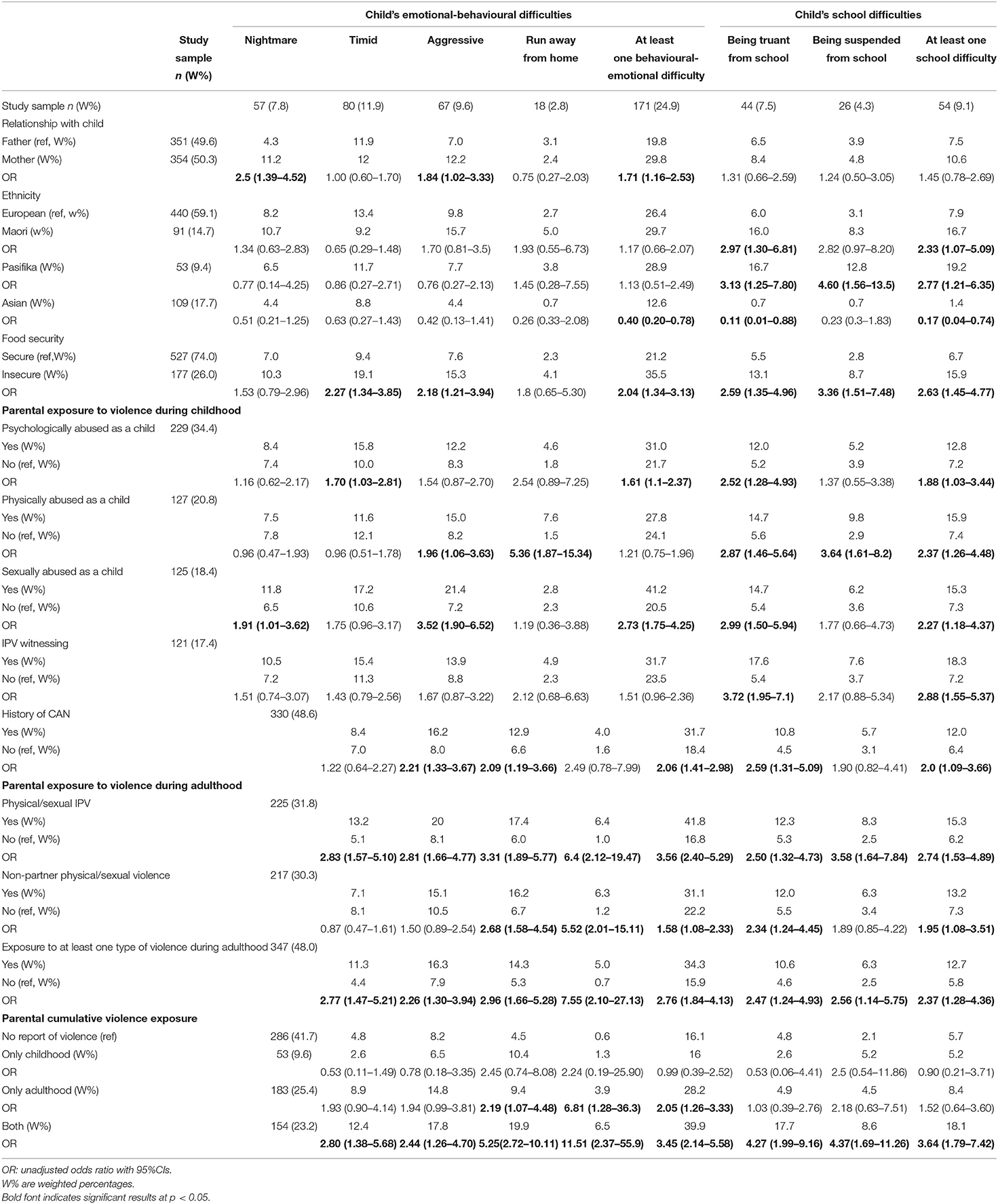

Table 2. Child's emotional-behavioural and school difficulties by parental socio-demographic characteristics and parental violence exposure, from the 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Study.

To understand the impact of each type of parental violence exposure during childhood and adulthood on their children's outcomes, a series of multivariable logistic regressions were conducted with exposure variables entered one by one into logistic regression analyses after adjusting for those socio-demographic characteristics that had a significant association with children's outcomes at the univariate level (e.g., parent's gender, ethnicity, and food security status). The results were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% CIs (Table 5). We sought to control for the effect of socio-demographic characteristics because of the known association between child outcomes and socio-demographics characteristics.

A multivariable logistic regression was also conducted to investigate the impact of parental cumulative violence exposure adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics (Table 5). Finally, to determine whether there were any gender differences in the association between each parental exposure variable and child outcomes, multivariable logistic regression models were conducted with each exposure variable, gender and interaction terms (between each exposure and gender) included. These regression models were also adjusted for socio-demographic variables. As no significant interaction effects were found, the results of multivariable logistic regression in Table 5 were not stratified by gender. However, due to the gender-based nature of violence discussed in literature (10, 11, 23) and to explore any gender differences which could not be captured by interaction terms, multivariable analyses stratified by gender are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics and Prevalence of Parental Exposure to Violence During Childhood and/or Adulthood

Mothers constituted half of the study sample (50.3%). Respondents ranged in age from 20 to 71 years, mean = 43.5, SD = 7.4 (fathers ranged in age from 24 to 71 years, mean = 45.1, SD = 7.4 and mothers ranged in age from 20 to 56 years, mean = 42, SD = 7.0). The majority of the study sample (95.4%) were aged over 30. Those who identified as European constituted 59.1% of the sample, Māori 14.7%, Pasifika 9.4%, and Asian 17.7%. Over one quarter of the sample (26%) were classified as food insecure (Table 2).

Almost half of the study sample (parents) reported at least one type of violence exposure during their childhood (48.6%). The same proportion (48%) reported exposure to at least one type of violence during adulthood. Psychological abuse during childhood was the most prevalent childhood violence exposure and was reported by almost one third of the study sample (34.4%), followed by child physical abuse reported by one-fifth (20.8%) of the sample. Sexual abuse during childhood was reported by 18.4% of parents (24.8 % of mothers; 10% of fathers) and IPV witnessing was reported by 17.4% of parents (17.7% of mother; 12.7% of fathers) (Table 3). Exposure to physical or sexual violence by either a partner or non-partner were both reported by almost 30% of parents. Regarding cumulative violence exposure, 41.7% of parents reported no exposure to violence during childhood or adulthood. Less than ten percent (9.6%) of parents reported exposure to violence only during childhood and one quarter (25.4%) reported exposure to violence only during adulthood. Those parents who reported exposure to violence during both childhood and adulthood constituted 23.2% of the study sample (Table 2).

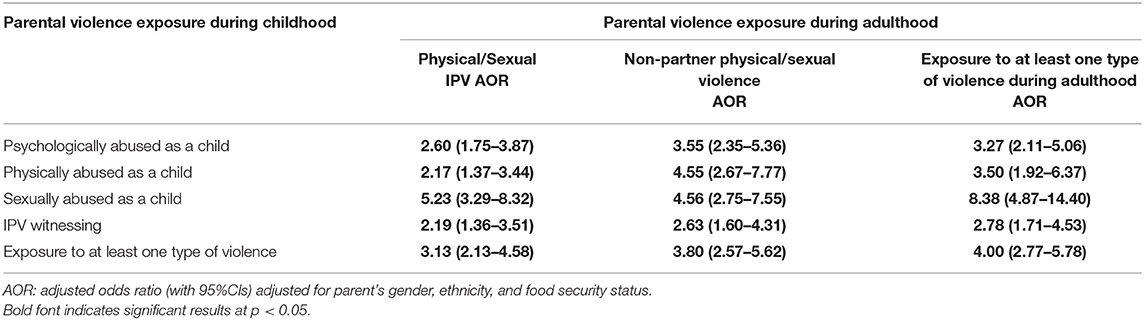

Mothers were more likely to report exposure to violence during childhood and were less likely to report exposure to non-partner violence during adulthood compared with fathers. Māori respondents were more likely to report exposure to violence during childhood and/or adulthood. Those identified as food insecure were more likely to report exposure to violence during childhood and/or adulthood (Table 3). Exposure to violence during childhood (any type) was significantly associated with exposure to violence during adulthood (any type) with AORs ranging from 2.17 (95% CI: 1.37–3.44) (for exposure to physical abuse as a child and exposure to physical and/or sexual IPV) to 8.38 (95% CI: 4.87–14.40) (for exposure to sexual abuse as a child and exposure to at least one type of violence during adulthood) (Table 4). Supplementary Table 1 shows these associations for mothers and fathers separately.

Table 4. Multivariable analyses: association between parental violence exposure during childhood and during adulthood.

Prevalence and Pattern of Child Emotional-Behavioural Difficulties as Reported by Parents

The most prevalent emotional-behavioural difficulty reported by parents was of a child being timid or withdrawn (11.9 %), followed by a child being aggressive with other children or parents (9.6%). A child having nightmares was reported by 7.8% of parents and a child running away from home was reported by 2.8% of parents. In general, one quarter of parents reported that their children aged 5–17 had at least one emotional-behavioural difficulty (Table 2). Mothers were more likely to report their children had at least one emotional-behavioural difficulty compared with reports from fathers (OR 1.71, 95% CI: 1.16–2.53). Those who identified as Asian were less likely to report that their child had at least one emotional-behavioural difficulty compared with those who identified as European (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20–0.78). Other differences between ethnic groups were not significant. Those who identified as food insecure were more likely to report that their children had at least one emotional-behavioural difficulty (OR 2.59, 95% CI:1.35–4.96).

Parental Exposure to Violence During Childhood and Adulthood and Their Reports of Their Children's Emotional-Behavioural Difficulties

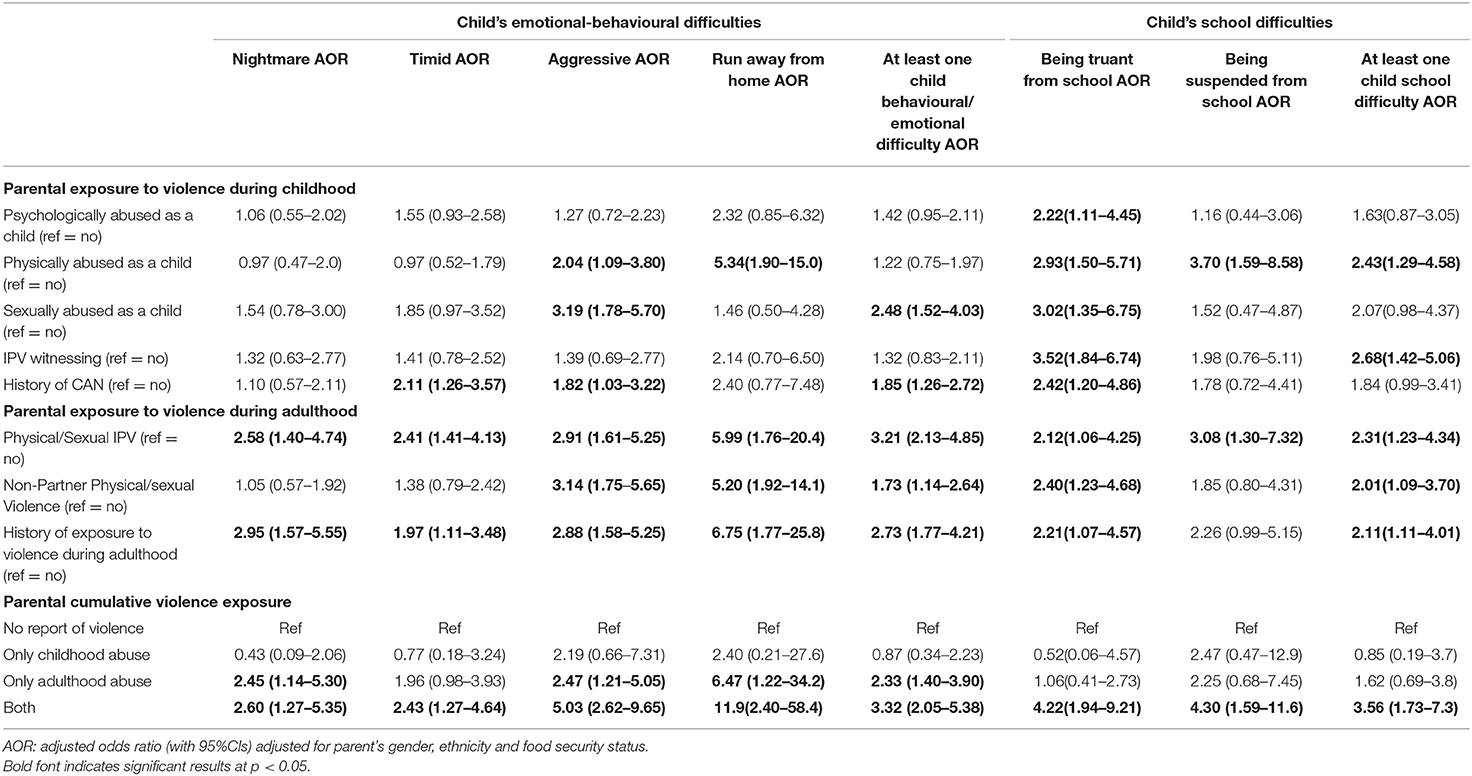

Parents with a history of CAN were more likely to report that they had a child who was timid (AOR 2.11, 95%CI: 1.26–3.57) or aggressive (AOR 1.82, 95%CI: 1.03–3.22) compared with parents with no history of CAN. In general, parents with a history of CAN were more likely to report that they had a child with at least one emotional-behavioural difficulty (AOR 1.85, 95%CI: 1.26–2.72) (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariable analyses: association between parental exposure to violence and child's emotional-behavioural and school difficulties.

Parents exposed to IPV were more likely to report that they had a child with any type of emotional-behavioural difficulty, with AORs ranging from 2.41 (95% CI: 1.41–4.13) for a child being timid to 5.99 (95%CI: 1.76–20.37) for a child running away from home. Parents with exposure to non-partner violence during adulthood were more likely to report that they had a child who had been aggressive (AOR 3.14, 95% CI: 1.75–5.65) or run away from home (AOR 5.20, 95% CI: 1.92–14.1). Parents with any exposure to violence during adulthood (by an intimate partner or non-partner) were more likely to report that they had a child with any type of emotional-behavioural difficulty, with AORs ranging from 1.97 (95%CI: 1.11–3.48) for being timid to 6.75 (95%CI: 1.77–25.78) for running away from home. Parents who had been exposed to violence during adulthood had increased odds of reporting that they had a child with at least one emotional-behavioural problem (AOR 2.73, 95%CI: 1.77–4.21) (Table 5).

Parents with no history of abuse during childhood and/or adulthood had lower rates of reporting that their children experienced emotional-behavioural difficulties (Table 2). Parents who had been exposed to only violence in childhood did not report that their children had more emotional-behavioural difficulties compared to parents without any history of violence exposure during childhood and adulthood. However, parents with violence exposure only during adulthood had higher odds of reporting emotional-behavioural problems for their children, ranging from 1.96 (95% CI: 0.98–3.93) for being timid to 6.47 (95% CI: 1.22–34.22) for running away from home after adjusting for socio-demographic factors. Similarly, parents who reported that they had a history of violence exposure during both childhood and adulthood had higher odds of reporting that they had a child with emotional-behavioural difficulties compared with parents with no history of violence exposure (Table 5). The results of multivariable analyses stratified by parent's gender are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 3. The associations show similar patterns for mothers and fathers, however the associations were stronger for mothers.

Prevalence and Pattern of Parental Reports of Child School Difficulties

Having a child who was truant from school was reported by 7.5 % of parents. Having a child who was suspended from school was less common and was reported by 4.3% of parents. In general, 9.1% of parents reported that they had a child with at least one school difficulty. Those who identified as Māori or Pasifika were more likely to report that their children had at least one school difficulty (OR 2.33, 95% CI: 1.07–5.09 for Māori; OR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.21–6.35 for Pasifika) compared with those who identified as European. Those who identified as Asian were less likely to report at least one school-related problem compared with those who identified as European (OR 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04–0.74) (Table 2). Those who identified as food insecure were more likely to report at least one school difficulty compared with those who identified as food secure (OR 2.63, 95% CI: 1.45–4.77). No significant association was found between gender of parent and child school difficulties.

Parental Violence Exposure During Childhood and Adulthood and Their Reports of Their Children's School Difficulties

Parents who were exposed to any type of violence during childhood (psychological, physical, or sexual abuse or IPV witnessing) were more likely to report that they had a child who had been truant from school (ranging from AOR 2.22, 95% CI: 1.11–4.45 for parents with exposure to child psychological abuse to AOR 3.53, 95% CI: 1.84–6.74 for parents who had witnessed IPV as a child). Parents who were physically abused during childhood were also more likely to report that they had a child who had been suspended from school (AOR 3.70, 95% CI: 1.59–8.58) (Table 5).

Parents who had been exposed to any type of violence during adulthood (by an intimate partner or non-partner) were also more likely to report that they had a child who had been truant from school (range: AOR 2.12, 95% CI: 1.06–4.25 for parents exposed to physical and/or sexual IPV to AOR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.23–4.68 for parents exposed to non-partner physical and/or sexual violence). Parents who reported exposure to physical/sexual IPV were also more likely to report that they had a child who had been suspended from school (AOR 3.08, 95% CI: 1.30–7.32) (Table 5).

Only parents who reported that they had been exposed to both violence during childhood and violence during adulthood reported that their children had more school difficulties compared with parents with no history of violence exposure during childhood and adulthood (AOR 3.56, 95% CI: 1.73–7.31 for at least one child school difficulty) (Table 5). The results of multivariable analyses stratified by parent's gender are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 3. As with emotional-behavioural difficulties, the associations show similar patterns for mothers and fathers, however the associations were stronger for mothers.

Discussion

In this New Zealand cohort of parents of children aged 5–17 years old, parental exposure to violence during childhood and adulthood was prevalent. Almost half of the study sample (parents) (48.6%) retrospectively reported exposure to violence during their childhood and the same proportion (48%) reported exposure to violence during their adulthood life. Parental exposure to violence during childhood and adulthood was more likely to be reported by those who were identified as Māori and those who identified as food insecure. Ethnic differences might be due to experiences of colonisation, and historical and cumulative trauma (24). Mothers were more likely to report exposure to sexual abuse as a child and to report having witnessed IPV against their mother/stepmother.

Parents who reported exposure to violence during childhood were also more likely to report exposure to violence during adulthood (experience of both IPV and non-partner violence). Specifically, parents who reported exposure to at least one type of violence during childhood were four times more likely to report exposure to at least one type of violence during adulthood. This finding is consistent with evidence indicating that children who have been exposed to maltreatment are at increased risk of continued maltreatment by others (25–27). The findings also support evidence from smaller studies, primarily conducted with shelter or refuge samples (28) showing that women who experience physical or sexual abuse in childhood were more likely to report adult experiences of IPV.

In general, children of parents with histories of exposure to violence during childhood were at increased risk for experiencing emotional-behavioural or school difficulties. These findings are consistent with previous studies (5, 9). However, where parents reported a history of childhood abuse but not adult experience of violence, their children had similar odds of experiencing difficulties to the children of parents who had not been exposed to any violence in their lifetime. Such results highlight an opportunity for effective early intervention to limit or ameliorate the impact of violence exposure during childhood by preventing experience of violence in adulthood and to ultimately break the intergenerational cycle of violence and disadvantage. Suggestions for way to interrupt these cycles of violence come from work on fostering resilience, which outlines ways in which individuals can be supported to develop a “density and diversity of assets and resources” that can help them overcome violence exposure. These suggestions include helping individuals to build strengths, such as the development of emotional regulation, and interpersonal and meaning-making skills. It also includes assisting people to develop resources and assets through providing opportunities to connect with supportive environments, such as with nurturing schools and community organisations. Enhancing networks that support cultural connexion and strength can also foster the development of resilience (24, 29–31). Development and implementation of these supportive cultural strategies may be especially important as our research, and other research, indicates that Māori students are more likely to be stood down, suspended, and excluded from schools than any other ethnic group (32).

Children of parents who had been exposed to violence only during adulthood were at higher risk of experiencing emotional-behavioural difficulties compared with children of parents with no violence exposure. This is consistent with other studies which have reported that experience of violence in intimate relationships is associated with poorer outcomes for their children (8, 9, 26, 33). It is reasonable to postulate that the abusing partner might undermine their partner's parenting ability, which in turn could hinder the development of effective child-parent relationships and functioning of their children (5, 9, 26). Strategies to resolve such difficulties include identifying who is the non-abusing parent and supporting them to be a safe, secure attachment for the child(ren). It is also likely that children who live in homes where IPV occurs are more likely to be directly abused and neglected (27, 34) which increases their likelihood of experiencing difficulties at home and/or at school (27). Both of these points highlight the importance of developing strategies that contain, challenge and change the behaviour of the person using violence (14), and that work to resolve these abusive behaviours before seeking to reestablish a relationship between the parent and child (35, 36).

Children of parents with histories of exposure to violence during both childhood and adulthood had the highest prevalence of experiencing emotional/behavioural and school difficulties. This indicates that cumulative violence exposure throughout the lifespan is associated with poorer outcomes compared with exposures to violence at a single point in life. A possible explanation for this finding could be that those with cumulative violence exposure are more likely to suffer from serious mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and complex PTSD which in turn would have an impact on their child rearing (9, 37). Indeed, long-lasting relational effects of exposure to violence during childhood such as a range of physical and psychological morbidities, exacerbated by cumulative traumatic experiences as an adult can impede the capacity of parents to nurture and care for children, leading to ‘intergenerational cycles’ of trauma (38).

Parents with a history of violence are also more likely to have multiple socio-economic challenges, including unintended pregnancies (39), antenatal and postnatal depression (40), contact with the justice system and low employment (41) which can also preclude the capacity of parents to nurture and care for children (38). Our findings support other studies reporting that experience of multi forms of violence is associated with greater adverse impacts (9, 25, 37). These findings highlight the intergenerational impacts of family violence and the complex intersections between parents' and children's life experiences. However, it is important to note that many children of parents with previous exposure to violence (either during childhood or adulthood or both) were not identified as having emotional-behavioural and/or school difficulties. It is possible that some parents may under-report difficulties that children are experiencing, but equally possible that some families, schools and health services are effectively supporting these children. Resilience research has shown that family support and extra-family links, school and peer support have all been correlated with greater resiliency and better functioning in children exposed to violence (42, 43). Research utilising Māori and Indigenous knowledge has also demonstrated how these approaches can strengthen whānau (family) resilience (44, 45).

Implications

For those children who are experiencing emotional-behavioural and school difficulties, these findings highlight the importance of screening for violence exposure with the children and with the children's families (e.g., in before school checks to identify children's needs). This would support the identification of those most in need of intervention and provide the opportunity to deliver supportive strategies and guided referrals as indicated. Early screening may bring us closer to identifying youth at an earlier phase in their lifespan, which could provide opportunities to mitigate the effects of violence exposure and reduce their risk of subsequent victimisation. Enhancing positive, supportive relationships between parents and children and between parents and other adults could be a key prevention strategy for interrupting the cycle of child maltreatment. This in turn would have benefits for subsequent generations.

Strengths

The strengths of this study include the large general population cohort, the assessment of multiple violence exposures over the lifespan using standardised measures, inclusion of exposure to both partner and non-partner violence during adulthood, assessment of a wide range of emotional-behavioural and school difficulties among children, and inclusion of both mothers and fathers.

Limitations

Using parental report of child outcomes may introduce bias. This may come from many sources, including parental cultural knowledge and perceptions of child behaviours, or parent's feelings of shame or stigma. Use of multiple informants, e.g., teachers, would be beneficial to validate parent's reports of children's difficulties. Due to these limitations, it is likely that our prevalence estimates underreport the extent of child difficulties. It is also plausible that we may have missed the most serious cases as individuals with severe problems are less likely to participate in population-based studies like this. No casualty can be inferred. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms through which parental exposure to violence results in children's difficulties, and if this exposure has a differential effect for boys vs. girls. More importantly, further research on factors that mitigate the negative impacts of parental exposure to violence on their children's outcomes is urgently required. Future studies could expand this work by exploring the impacts of other parental adversities on their children's well-being. Inclusion of data on the violence exposure of both parents (the parental dyad) would also assist in exploring if there are cumulative effects of this exposure on children.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that children are at risk of experiencing difficulties when their parents have been exposed to violence. These results suggest the need for expanded prevention services and parent support for those already exposed to the violence. Our findings indicate that difficulties experienced by a considerable number of young children could be reduced by stopping violence. The accumulation of risk within families (child abuse, IPV, non-partner violence) highlights the need for effective early intervention to limit or ameliorate the impact of violence across the lifespan, to build resilience and foster the development of safe, stable and nurturing relationships in order to break the inter-generational cycle ofdisadvantage.

Better support of parents with a history of violence in childhood, and/or adulthood has the potential to disrupt the intergenerational experiences of violence and profoundly influence the lives of children and families. Strengthening the capacity of mental health and school professionals to recognise and respond to family violence and building stronger evidence about effective and timely interventions involving the health and education sectors are critical priorities for safeguarding the health of future generations.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the confidentiality and sensitivity of the data and Māori data sovereignty. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ai5mYW5zbG93QGF1Y2tsYW5kLmFjLm56.

Ethics Statement

The study was reviewed by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (reference number 2015/018244). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in the study. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LH organized the database, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JF contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision of the study, and writing—review and editing. PG contributed to the conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing-review and editing. TM contributed to the funding acquisition and writing-review and editing. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study received funding from the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Contract number CONT-42799-HASTR-UOA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.771834/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Datta DS, Julian E, Shelley RB. Child Maltreatment, Violence, Offending, and Educational Outcomes: Review of the Literature, Institute for the Study of Social Change, Hobart: University of Tasmania, (2019). p. 1–127.

2. Fanslow J, Hashemi L, Gulliver P, McIntosh T. Adverse childhood experiences in New Zealand and subsequent victimization in adulthood: findings from a population-based study. Child Abuse Negl. (2021) 117:105067. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105067

3. Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung W, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. (2001) 358:450–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05622-7

4. Van Wert M, Anreiter I, Fallon BA, Sokolowski MB. intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: a transdisciplinary analysis. Gender Genome. (2019) 3:1–21. doi: 10.1177/2470289719826101

5. Greene CA, Haisley L, Wallace C, Ford JD. Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 80:101891. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891

6. Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggress Violent Behav. (2008) 13:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005

7. Huth-Bocks A, Levendosky A, Semel M. The direct and indirect effects of domestic violence on young children's intellectual functioning. J Fam Violence. (2001) 16:269–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1011138332712

8. Peek-Asa C, Maxwell L, Stromquist A, Whitten P, Limbos MA, Merchant J. Does parental physical violence reduce children's standardized test score performance? Ann Epidemiol. (2007) 17:847–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.06.004

9. Gartland D, Giallo R, Woolhouse H, Mensah F, Brown SJ. intergenerational impacts of family violence - mothers and children in a large prospective pregnancy cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. (2019) 15:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.08.008

10. Lagdon S, Armour C, Stringer M. Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2014) 5:1–12. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794

11. Williams JR, Ghandour RM, Kub JE. Female perpetration of violence in heterosexual intimate relationships: adolescence through adulthood. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2008) 9:227–49. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324418

12. Tjaden. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Wahington, DC: U.S Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Insitute of Justice (2000).

13. Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H. Female Victims of Violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics (2009).

14. Family Violence Death Review Committee. Fourth Annual Report: January 2013 to December 2013. The Health Quality & Safety Commission, Wellington (2014).

15. Fanslow J, Gulliver P, Hashemi L, Malihi Z, Mcintosh T. Methods for the 2019 New Zealand family violence study a study on the association between violence exposure health and well being. Kotuitui: N Z J Soc Sci Online. (2021) 16:196–209. doi: 10.1080/1177083X.2020.1862252

16. Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women: Initial Results on Prevalence. Health Outcomes and Women's Responses Arrows for change. Geneva: World Health Organization (2005).

17. Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:1038–44. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

18. Bromberger JT, Schott LL, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, Harlow SD, Montez JK. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and depressive symptom burden across 15 years of follow-up during midlife: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Arch Womens Ment Health. (2017) 20:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0747-4

19. Burneo-Garcés C, Cruz-Quintana F, Pérez-García M, Fernández-Alcántara M, Fasfous A, Pérez-Marfil MN. Interaction between socioeconomic status and cognitive development in children aged 7, 9, and 11 years: a cross-sectional study. Dev Neuropsychol. (2019) 44:1–16. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2018.1554662

20. Pérez-Marfil MN, Fernández-Alcántara M, Fasfous AF, Burneo-Garcés C, Pérez-García M, Cruz-Quintana F. Influence of socio-economic status on psychopathology in ecuadorian children. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:43. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00043

21. Jamieson LM, Koopu PI. Associations between ethnicity and child health factors in New Zealand. Ethn Dis. (2007) 17:84–91.

24. Pihama L, Smith LT, Evans-Campbell T, Kohu-Morgan H, Cameron N, Mataki T, et al. Investigating Māori approaches to trauma-informed care. J Indig Wellbeing. (2017) 2:18–31.

25. Hodges M, Godbout N, Briere J, Lanktree C, Gilbert A, Kletzka NT. Cumulative trauma and symptom complexity in children: a path analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2013) 37:891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001

26. Fredland N, McFarlane J, Symes L, Maddoux J. Exploring the association of maternal adverse childhood experiences with maternal health and child behavior following intimate partner violence. J Women's Health. (2018) 27:64–71. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5969

27. Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. (2008) 32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004

28. Parks SE, Kim KH, Day NL, Garza MA, Larkby CA. Lifetime self-reported victimization among low-income, urban women: the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adult violent victimization. J Interpers Violence. (2011) 26:1111–28. doi: 10.1177/0886260510368158

29. Grych J, Hamby S, Banyard V. The resilience portfolio model: understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychol Violence. (2015) 5:343–54. doi: 10.1037/a0039671

30. Dhunna S, Lawton B, Cram F. An affront to her mana: young māori mothers' experiences of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. (2018). doi: 10.1177/0886260518815712

31. Ketu-McKenzie MD. Ngā mea koaro o ngā wā tamarikitanga, te taumahatanga o aua mea me ētahi mahi whakaora hinegaro mo ngā wāhine Māori = Adverse childhood experiences, HPA axis functioning and culturally enhanced mindfulness therapy among Māori women in Aotearoa New ZealandMassey University: New Zealand (2019).

32. Education Count New New Zealand Ministry of Education. Stand-downs, Suspensions, Exclusions and Expulsions from School (2020). Available online at: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/indicators/main/student-engagement-participation/Stand-downs-suspensions-exclusions-expulsions#:~:text=Schools%20continue%20to%20suspend%20M%C4%81ori,rate%20(4.3%20per%201%2C000 (accessed September 6, 2021).

33. Kiesel LR, Piescher KN, Edleson JL. The relationship between child maltreatment, intimate partner violence exposure, and academic performance. J Public Child Welf. (2016) 10:434–56. doi: 10.1080/15548732.2016.1209150

34. Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. (2004) 28:771–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008

35. Bancroft RL, Silverman JG, Ritchie D. The Batterer as Parent. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications (2011).

36. Mandel D, Rankin H. Working with Men as Parents: Becoming Father-Inclusive to Improve Child Welfare Outcomes in Domestic Violence Cases. Columbus, OH: Family and Youth Law Center, Capital University Law School (2018).

37. Hooven C, Nurius P, Logan-Greene P, Thompson E. Childhood violence exposure: cumulative and specific effects on adult mental health. J Fam Viol. (2012) 27:511–22. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9438-0

38. Chamberlain C, Gee G, Harfield S, Campbell S, Brennan S, Clark Y, et al. Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: a scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0213460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213460

39. Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, Williamson DF, McMahon PM, Santelli JS, et al. Unintended pregnancy among adult women exposed to abuse or household dysfunction during their childhood. JAMA. (1999) 282:1359–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1359

40. Nagl M, Lehnig F, Stepan H, Wagner B, Kersting A. Associations of childhood maltreatment with pre-pregnancy obesity and maternal postpartum mental health: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:391. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1565-4

41. Borchers A, Lee RC, Martsolf DS, Maler J. Employment maintenance and intimate partner violence. Workplace Health Saf. (2016) 64:469–78. doi: 10.1177/2165079916644008

42. Yule K, Houston J, Grych J. Resilience in children exposed to violence: a meta-analysis of protective factors across ecological contexts. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2019) 22:406–31. doi: 10.1007/s10567-019-00293-1

43. Howell KH. Resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to family violence. Aggress Violent Behav. (2011) 16:562–9. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.001

44. Grice Jade Le, Braun Virginia, Wetherell Margaret. “What I reckon is, is that like the love you give to your kids they'll give to someone else and so on and so on”: Whanaungatanga and matauranga Maori in practice. N Z J Psychol. (2017) 46:88–97.

Keywords: intergenerational impact, parental violence exposure, emotional-behavioural difficulties, school difficulties, child's outcomes, New Zealand

Citation: Hashemi L, Fanslow J, Gulliver P and McIntosh T (2022) Intergenerational Impact of Violence Exposure: Emotional-Behavioural and School Difficulties in Children Aged 5–17. Front. Psychiatry 12:771834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.771834

Received: 09 September 2021; Accepted: 13 December 2021;

Published: 04 January 2022.

Edited by:

Veit Roessner, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, GermanyReviewed by:

Geilson Lima Santana, University of São Paulo, BrazilStefania Muzi, University of Genoa, Italy

Gerard Leavey, Ulster University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Hashemi, Fanslow, Gulliver and McIntosh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janet Fanslow, ai5mYW5zbG93QGF1Y2tsYW5kLmFjLm56

Ladan Hashemi

Ladan Hashemi Janet Fanslow

Janet Fanslow Pauline Gulliver1

Pauline Gulliver1