- 1Department of Psychiatry, Jawahar Lal Nehru Memorial Hospital, Kashmir, India

- 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Kelaniya, Ragama, Sri Lanka

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Psychosis Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 4Department of Psychiatry, College of Medical Sciences, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi, Nigeria

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 6Department of Mental Health, Heim Pal National Pediatric Institute, Budapest, Hungary

- 7Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary

- 8Fortis Hospital, New Delhi, India

- 9Mental Health Unit, Hospital School of the University Fernando Pessoa, Gondomar, Portugal

- 10Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal

- 11Consultant Geriatric Psychiatrist, APOLLO Multispecialty Hospitals, Kolkata, India

Suicide is a global health issue that needs to be addressed. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an increased mental health burden. Stigma has obstructed efforts to prevent suicide as individuals who need urgent support do not seek appropriate help. The influence of stigma is likely to grow in tandem with the COVID-19 pandemic. The stigmatization of persons with mental illnesses is widespread worldwide, and it has substantial effects on both the individual and society. Our viewpoints aim to address the probable link between stigma and suicide in the wake of the current pandemic and propose ideas for reducing suicide-related stigma.

Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death globally, with this trend being more pronounced in younger people and low and middle income countries (LMIC). According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), over 77% of suicide deaths worldwide occur in LMIC, with more than 700,000 suicide deaths reported in 2019 and 173,347 in India alone (1). Suicide is thus considered a global public health concern.

COVID-19 pandemic was the most pressing issue faced in the 2020–2022 period, and it had a detrimental effect on communities, including patients and healthcare workers. Pandemics are not just medical experiences; they cause interference in nearly all biopsychosocial dimensions. According to the WHO, until May 18, 2022, there have been approximately 523 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and the disease has caused the death of more than 6.27 million people worldwide. LMICs have suffered more intensely with the pandemic, accounting for many cases and deaths. For instance, the death count in Brazil surpassed 665,000 and 325,000 in Mexico; in India, the number is approximately 520,000, and in Iran, more than 141,000 have died due to COVID-19 (2). In addition to the impact of the virus on the mental health of affected populations, social distancing, quarantine and other similar measures used to control the spread of the virus also imposed significant negative psychosocial consequences such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression (3).

The mental health burden has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and communities worldwide require additional psychosocial support. This paper highlights the stigma and discrimination associated with suicides in COVID-19 and how it plays a core role in managing suicidal risk in the community.

COVID-19: The Potential Risk of Suicide

There is debate about the increase in suicidal ideations after the beginning of COVID-19. A multicenter study in 21 countries reported that the numbers have remained unchanged or declined in the early pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period in high-income and upper-middle-income countries (4). According to a systematic review of many studies about suicidal behavior related to the COVID-19 pandemic from November 2019 to September 2020 that included 120,076 persons, there has been an increase in suicidal ideation rates in comparison with the period before the pandemic, with a pooled prevalence of approximately 12% (5). The same study described several risk factors associated with suicidal ideation during the pandemic, including quarantine, loneliness, sleep issues, poor social support, and mental and physical exhaustion (5). Social distancing and subsequent social isolation, economic problems due to lockdown policies and unemployment, social stigma and discrimination, fear of the virus, stress, and the burden of work that some professionals have experienced have also been pointed out as potential factors associated with suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic (6). Certain vulnerable groups are at an increased risk of suicide and other self-harm related behavior, such as the elderly, persons with mental disorders, healthcare professionals, the homeless, and migrant workers (6). During the pandemic, they should be the target of specific preventive measures by the services.

Stigma and Suicide

Stigma is a profoundly discrediting attribute and encompasses several components, i.e., labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination (7, 8). Stigma can also be classified into public stigma and self-stigma (9). The former refers to the general population’s reaction toward people with devalued characteristics, while the latter occurs when people with these devalued characteristics endorse the public attitudes and experience the negative consequences themselves. Stigma has been shown to display deleterious effects; for example, it has been shown to harm the self-esteem of those with mental illness (10). Public stigma may lead to social rejection, which leads to inequality in employment, access to health care and social participation (11). Stigma may be reduced by three approaches, i.e., protesting, education, and avoiding isolation (12). By protesting against inaccurate information held toward the devalued individuals, educating with the correct information and increasing contact between the public and the devalued individuals, the stigma is likely to diminish in certain settings.

The stigmatization of people with mental disorders is prevalent worldwide and leads to severe consequences for both the individual and broader society. Stigma in itself has a bidirectional relationship with mental illness and suicidality. Furthermore, patients with mental illnesses often face stigmatization, while on the other hand, stigma can precipitate mental illness and suicide (13). In addition, suicide is associated with stigma, which can manifest not only in suicide survivors but also in family members and close friends of victims of suicide. Thus, stigma may bring an additional burden to an already distressed individual, imposing stereotypes, distrust, a bad reputation, and a mark of disgrace, which can be produced by external members of the society or by the person her/himself (14). Suicide has also been equated with crime, punishment or sin, perpetuating stigma and impairing help-seeking (15). Stigma can lead to demoralization, feelings of isolation, loneliness, and hopelessness, leading to an increased risk of suicide (16). Also, legislation in certain nations criminalizing suicide is responsible for increasing stigma. Considering that stigma is also associated with ignorance and negative attitudes toward a specific phenomenon, it is essential to educate the public about suicide, associated factors, treatment and preventive strategies, and stimulate seeking care for those in need during the COVID-19 pandemic (16). It has been observed that financial crisis, unemployment, and poverty are the most prominent risk factors for suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic (17, 18).

COVID-19 and Associated Stigma

Isolation, physical distancing, lockdown and unemployment can be very demanding. COVID-19 has been an “infodemic” where misinformation and fake news have led to fear and stigma that add to the current crisis (19). There have been concerns about stigma and discrimination in previous pandemics, and COVID-19 is no exception. Multiple reasons have been attributed, such as improper information about the spread of disease and increased fear and anxiety. This is further aggravated by measures like isolation and physical distancing, which are essential for preventing the spread of disease. The risk of losing a loved one can be extrapolated to social and moral circumstances, which can further cause stigma. However, the actual origin of stigma is complex and may extend beyond concepts such as social disability or moral transgressions (20).

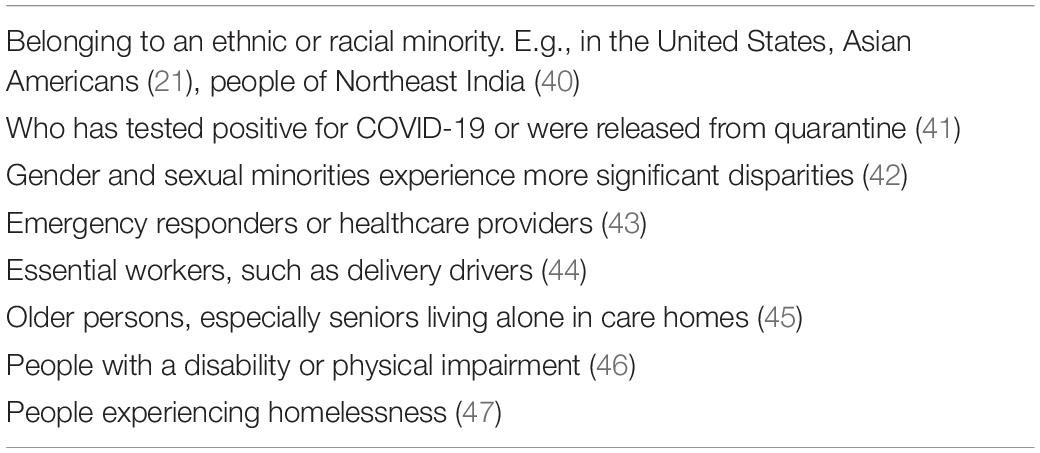

Public health emergencies, such as this pandemic, are stressful for people and communities. Fear and anxiety about the disease could lead to social stigma, labeling, stereotyping, discrimination and other negative behaviors toward others. For example, stigma and discrimination can occur when people link a disease, such as COVID-19, with a population, community, or ethnicity (21). Stigma can also happen after a person has recovered from COVID-19 or been released from home isolation or quarantine. Identified factors related to stigma in the pandemic have been listed in Table 1.

Heightened Stigma Leading to Suicidal Behavior

The social and economic hardships during this pandemic have negatively affected psychological wellbeing. The pandemic has been thought to have increased the risk of suicide among the frontline workers, elderly, migrants, homeless, poor, persons with mental disorders, and substance use disorders (22). The fear of COVID-19 infection, social boycott and loneliness during the quarantine were significant risk factors for suicidal behavior (23). Stigma leads to social isolation and discriminatory behaviors and undermines social cohesion in society, limiting opportunities for social interaction. Durkheim’s theory suggests that a breach in an individual relationship with society is a significant risk factor for suicide, and social integration has an inverse relation with the suicide rate (24). A study assessing the role of stigma in suicidal behaviors related to the interpersonal theory reported an indirect relationship between stigma to suicide-related perceptions (25). Further, the perceived burdensomeness and felt stigma contribute to suicide risk in vulnerable individuals (25).

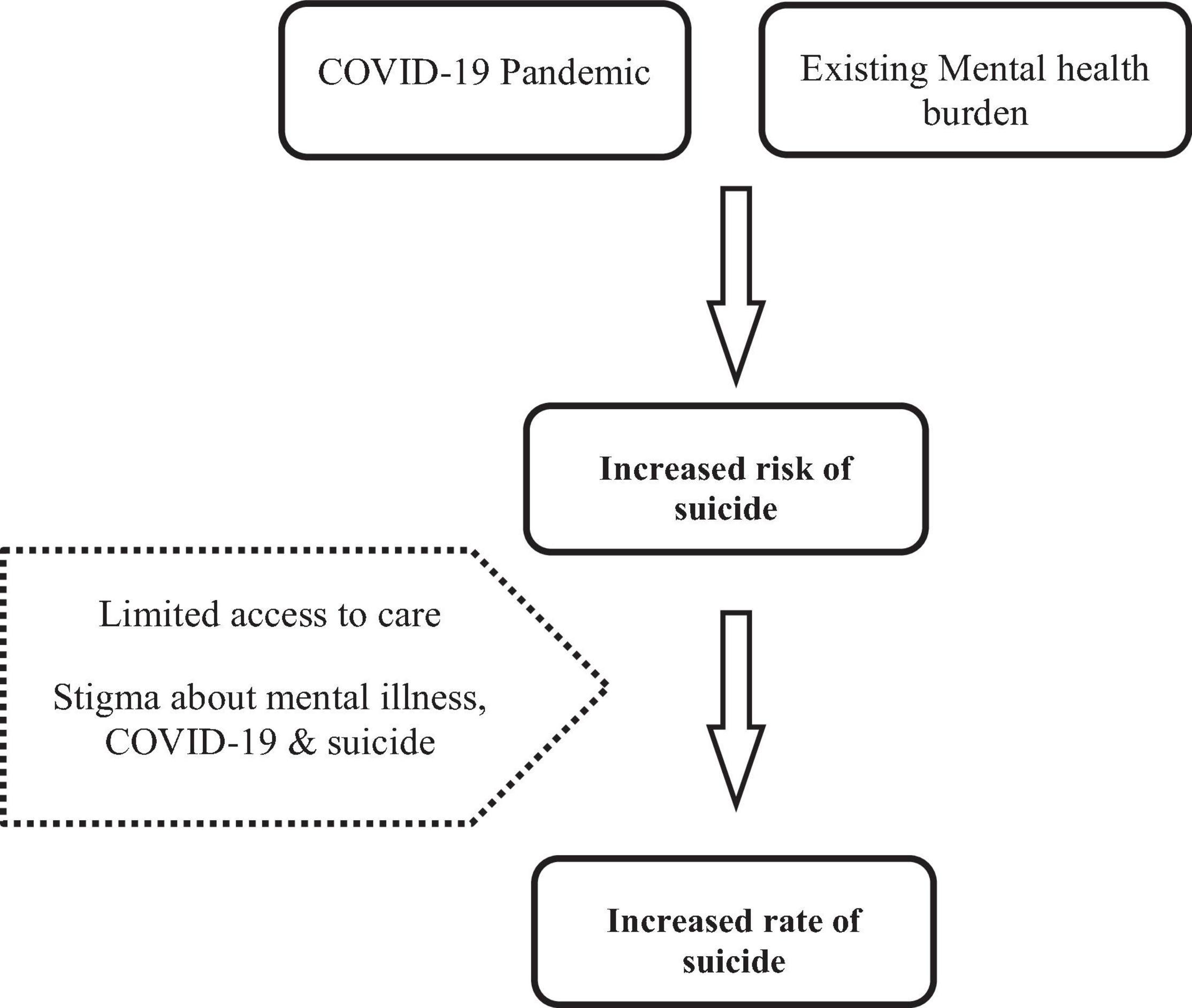

Stigma instills feelings of hopelessness, loneliness, anxiety, and anger in people who have experienced it, making them more prone to self-harming behaviors. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with recognized psychiatric problems might be unable to take their medications, causing symptoms to worsen and an increased risk of self-harm (26). Domestic and intimate partner violence has escalated due to the pandemic, resulting in psychological suffering and thoughts of self-harm among vulnerable couples (27). A recent study in Bangladesh reported that several factors, including the death of family members due to COVID-19, financial distress, domestic violence, alcohol consumption, social isolation, inaccurate information, stigma, and pandemic-related fear, ignited fear of suicidality (28). Figure 1 shows a proposed relationship between stigma and suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since suicide is a complex and multidimensional problem, recognition and knowledge from various approaches help us explore the problem and contribute to meaningful intervention strategies (29).

Empirical Findings on Stigma During the COVID-19 Pandemic

An adapted version of the Chronic Illness Anticipated Stigma Scale found that those who anticipated higher COVID-19 stigma and endorsed COVID-19 stereotypes to a greater degree would be less likely to seek a COVID-19 test (30). The Social Impact Scale (SIS), a widely used 24-item measure of stigmatization used for patients with medical conditions and infectious diseases such as HIV, has been used (31). It was found that COVID-19 patients experienced stigma, social rejection, financial insecurity, internalized shame and social isolation. They also showed that depressive symptoms were positively associated with overall stigma levels (31).

Reducing Stigma

Given these deleterious effects of stigma, more actions should be implemented to reduce the effect of stigma on individuals with suicidal behavior, enabling them to seek help. To date, evidence shows that mass media campaigns and reporting of suicide can modify beliefs and attitudes toward suicide (32). On the other hand, interventions including social contact and education effectively reduce stigma, which would hopefully reduce the risk of suicide (33).

Since the psychiatrists have a significant role in providing mental health services, early-career psychiatrists (E) are in the frontline; they play leadership roles in health care development and suicide prevention (34). They have first-hand experience observing the deleterious impact of stigma on a suicidal individual, from help-seeking to treatment completion. Moreover, since the beginning of the pandemic, trainees and young specialists have been regularly redeployed to critical care units or COVID wards in addition to their work on psychiatric services. Suicide prevention training in ECPs, especially in the COVID-19 crisis, would add to the mental healthcare delivery package (35). ECPs are uniquely positioned to bring together knowledge regarding the pathophysiology and epidemiology of COVID-19 as medical doctors, a sound understanding of suicide and other mental health issues, and a comprehensive approach to stigma as psychiatrists, with an active, clear, and straightforward approach and informative presence in the social media (36).

Therefore, ECPs need to have a prominent role in the fight against COVID-19 and suicide-related stigma, informing, teaching, promoting research, and influencing public policies (37). This can serve as an integral suicide prevention approach during the present crisis, subject to further research. Moreover, ECPs can help screen for mental health conditions in at-risk individuals, such as recovered individuals, health care workers, and close contacts.

Organizing support networks for at-risk individuals may provide powerful stress-buffering effects at an interpersonal level (38). Educating frontline staff who care for individuals with COVID-19 about stigma and providing care and support to the staff may also help reduce stigma and its associated effects such as burnout and work stress. At the community level, ECPs should adopt educational approaches to debunk unscientific beliefs surrounding COVID-19 and to publicize the nature of stigma on COVID-19, mental illness and suicide through mass media campaigns. Activities such as giving a voice to stigmatized COVID-19 survivors will enhance the public understanding of the impact of stigma, reducing discrimination by the general public. Advocacy interventions to seek support and recognition from policy developers on measures to minimize inequalities faced by the stigmatized individuals are essential. ECPs should research the complex relationship between COVID-19 related stigma and suicide and provide more scientific evidence to implement interventions. Lived experiences of suicide survivors, stigmatized frontline health workers, and ECPs themselves matter to shape health and policy interventions (39).

Intervention

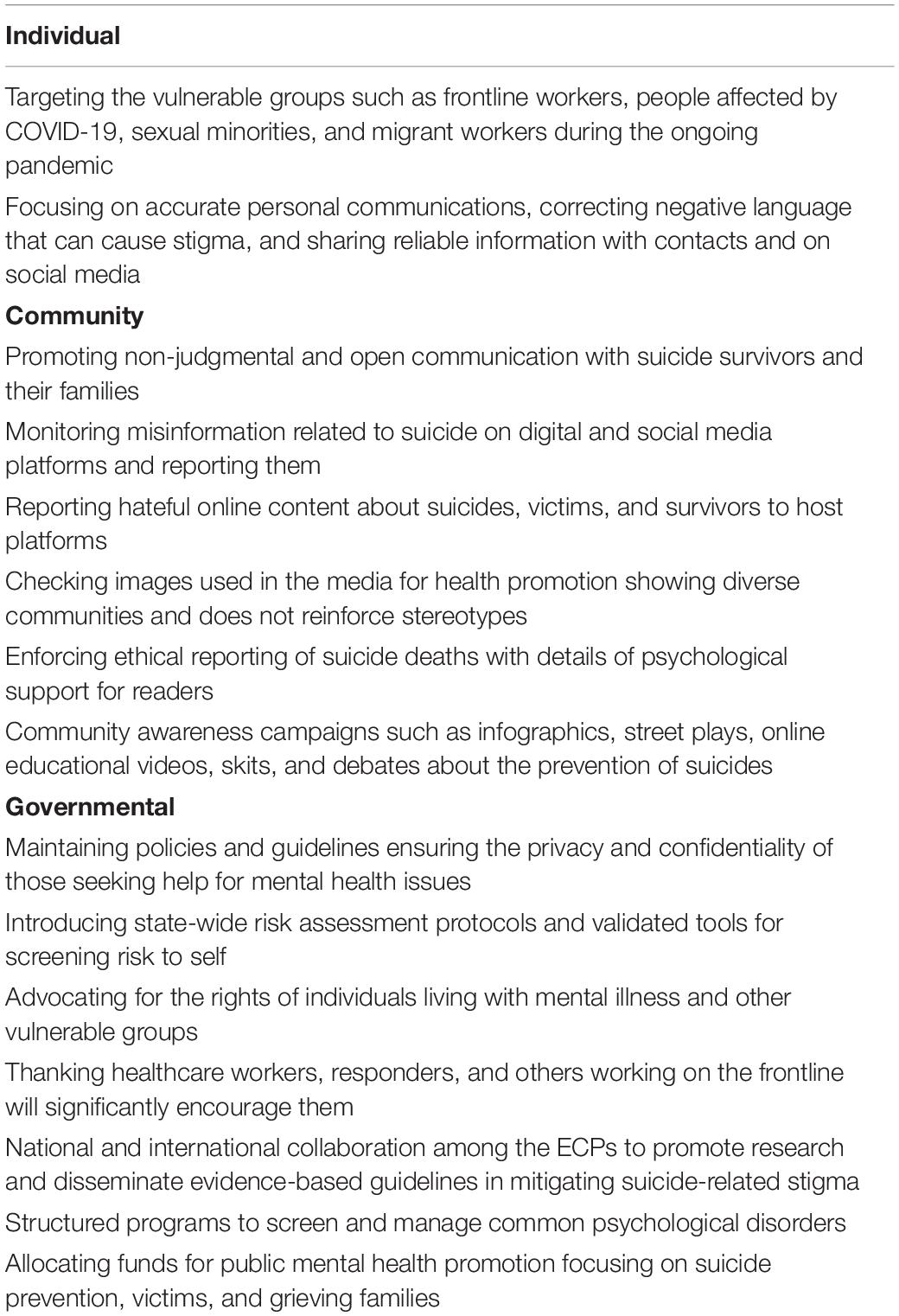

Finally, targeted interventions and a collaborative approach are required at various levels: individual, community and governmental. Suggested recommendations at each level are provided below in Table 2. By implementing these strategies, COVID-19 and suicide-related stigma could be addressed, reducing suicide risk in the community.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SS conceptualized and wrote the first draft. All other authors contributed equally to critical revision and writing of the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization [WHO]. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. Genova: World Health Organization (2019).

2. Covid-19 Data Explorer. Our World in Data. (2022). Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer (accessed May 18, 2022).

3. Cavicchioli M, Ferrucci R, Guidetti M, Canevini MP, Pravettoni G, Galli F. What will be the impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on psychological distress? Considerations based on a systematic review of pandemic outbreaks. Healthcare. (2021) 9:101. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010101

4. Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, DelPozo-Banos M, Arya V, Analuisa-Aguilar P, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:579–88. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2

5. Farooq S, Tunmore J, Ali W, Ayub M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 306:114228. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114228

6. Pinto S, Soares J, Silva A, Curral R, Coelho R. COVID-19 Suicide Survivors—A Hidden Grieving Population. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:626807. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.626807

7. Goffman E. Stigma and social identity. In: V Bacigalupo, J Bornat, B Bytheway, J Johnson, S Spurr editors. Underst Care, Welf Community A Reader. Milton Park: Routledge (2005). p. 143–5.

8. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. (2001) 27:363–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

9. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self–stigma of mental illness: implications for self–esteem and self–efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2006) 25:875–84. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875

10. Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. (2001) 52:1621–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621

11. Tyler I, Slater T. Rethinking the sociology of stigma. Sociol Rev. (2018) 66:721–43. doi: 10.1177/0038026118777425

12. Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. (2002) 9:35–53. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35

13. Shrivastava A, Bureau Y, Rewari N, Johnston M. Clinical risk of stigma and discrimination of mental illnesses: need for objective assessment and quantification. Indian J Psychiatry. (2013) 55:178. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111459

14. Sudak H, Maxim K, Carpenter M. Suicide and stigma: a review of the literature and personal reflections. Acad Psychiatry. (2008) 32:136–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.136

16. Nathan NA, Nathan KI. Suicide, stigma, and utilizing social media platforms to gauge public perceptions. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 10:947. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00947

17. Bhuiyan AKMI, Sakib N, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Mamun MA. COVID-19-related suicides in bangladesh due to lockdown and economic factors: case study evidence from media reports. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2020) 19:2110–5. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00307-y

18. Mamun MA, Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty?–The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028

19. Gupta A, Li H, Farnoush A, Jiang W. Understanding patterns of COVID infodemic: a systematic and pragmatic approach to curb fake news. J Bus Res. (2022) 140:670–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.032

20. Badrfam R, Zandifar A. Stigma Over COVID-19; New Conception Beyond Individual Sense. Arch Med Res. (2020) 51:593. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.006

21. Gutierrez AM, Schneider SC, Islam R, Robinson JO, Hsu RL, Canfield I, et al. Experiences of stigma in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma Health. (2022). doi: 10.1037/sah0000354

22. Banerjee D, Kosagisharaf JR, Rao TSS. ‘The dual pandemic’of suicide and COVID-19: a biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 295:113577. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577

23. Dsouza DD, Quadros S, Hyderabadwala ZJ, Mamun MA. Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113145. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145

24. Kim HHS, Jung JH. Social isolation and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national analysis. Gerontologist. (2021) 61:103–13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa168

25. Khazem LR, Anestis MD, Gratz KL, Tull MT, Bryan CJ. Examining the role of stigma and disability-related factors in suicide risk through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 137:652–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.007

26. Demir B, Guneysu E, Sancaktar M, Sahin SK, Elboga G, Altindag A. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medication adherence in psychiatric disorders. Medicine. (2021) 10:720–4. doi: 10.5455/medscience.2021.02.049

27. Gautam S, Setu S, Khan MGQ, Khan MB. Analysis of the health, economic and environmental impacts of COVID-19: the Bangladesh perspective. Geosyst Geoenviron. (2022) 1:100011. doi: 10.1016/j.geogeo.2021.100011

28. Rahman ME, Al Zubayer A, Al Mazid Bhuiyan MR, Jobe MC, Ahsan Khan MK. Suicidal behaviors and suicide risk among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e05937. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05937

29. Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, O’Connor RC, Oquendo MA, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Prim. (2019) 5:74. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0121-0

30. Earnshaw VA, Brousseau NM, Hill EC, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Fox AB. Anticipated stigma, stereotypes, and COVID-19 testing. Stigma Health. (2020) 5:390–3. doi: 10.1037/sah0000255

31. Yuan Y, Zhao YJ, Zhang QE, Zhang L, Cheung T, Jackson T, et al. COVID-19-related stigma and its sociodemographic correlates: a comparative study. Glob Health. (2021) 17:54. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00705-4

32. Niederkrotenthaler T, Braun M, Pirkis J, Till B, Stack S, Sinyor M, et al. Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2020) 368:m575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m575

33. Rüsch N, Zlati A, Black G, Thornicroft G. Does the stigma of mental illness contribute to suicidality? Br J Psychiatry. (2014) 205:257–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.145755

34. Alkasaby MA, Philip S, Agrawal A, Jakhar J, Ojeahere MI, Ori D, et al. Early career psychiatrists advocate reorientation not redeployment for COVID-19 care. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021). [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/00207640211057734

35. Enara A, Banerjee D, Tripathi A. Early career psychiatry section-world association of social psychiatry-history and future directions. Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 3:230–3.

36. Koh S, Cattell GM, Cochran DM, Krasner A, Langheim FJP, Sasso DA. Practitioner’s comer: psychiatrists’ use of electronic communication and social media and a proposed framework for future guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. (2013) 19:254–63. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000430511.90509.e2

37. Ransing R, Adiukwu F, Pereira-Sanchez V, Ramalho R, Orsolini L, Teixeira ALS, et al. Mental health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a conceptual framework by early career psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102085. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102085

38. Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2004) 27:392–401. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.392.401

39. Schlichthorst M, Ozols I, Reifels L, Morgan A. Lived experience peer support programs for suicide prevention: a systematic scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2020) 14:65. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00396-1

40. Chanu MO, Sharad S. Inter group perception and experience exploration in the lives of Northeasterners NE in India. Def Life Sci J. (2021) 6:20–9. doi: 10.14429/dlsj.6.16657

41. Imran N, Afzal H, Aamer I, Hashmi A, Shabbir B, Asif A, et al. Scarlett letter: a study based on experience of stigma by COVID-19 patients in quarantine. Pakistan J Med Sci. (2020) 36:1471. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.7.3606

42. Solomon DT, Morey KE, Williams CJ, Grist CL, Malesky LA. COVID-19 health behaviors in a sexual minority sample: the impact of internalized stigma. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. (2021) 8:159–71. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000466

43. Teksin G, Uluyol OB, Onur OS, Teksin MG, Ozdemir HM. Stigma-related factors and their effects on health-care workers during COVID-19 pandemics in Turkey: a multicenter study. Med Bull Sisli Etfal Hosp. (2020) 54:281. doi: 10.14744/SEMB.2020.02800

44. Mejia C, Pittman R, Beltramo JMD, Horan K, Grinley A, Shoss MK. Stigma & dirty work: in-group and out-group perceptions of essential service workers during COVID-19. Int J Hosp Manag. (2021) 93:102772.

45. Fraser S, Lagacé M, Bongué B, Ndeye N, Guyot J, Bechard L, et al. Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing. (2020) 49:692–5.

46. Sharpe D, Rajabi M, Chileshe C, Joseph SM, Sesay I, Williams J, et al. Mental health and wellbeing implications of the COVID-19 quarantine for disabled and disadvantaged children and young people: evidence from a cross-cultural study in Zambia and Sierra Leone. BMC Psychol. (2021) 9:79. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00583-w

Keywords: suicide, stigma, COVID-19, mental health, psychiatry

Citation: Shoib S, Chandradasa M, Saeed F, Armiya’u AY, Roza TH, Ori D, Jakhar J, Rodrigues-Silva N and Banerjee D (2022) Suicide, Stigma and COVID-19: A Call for Action From Low and Middle Income Countries. Front. Psychiatry 13:894524. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.894524

Received: 11 March 2022; Accepted: 09 June 2022;

Published: 01 July 2022.

Edited by:

Christos Theleritis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Marinos Kyriakopoulos, King’s College London, United KingdomFlorian Riese, University of Zurich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2022 Shoib, Chandradasa, Saeed, Armiya’u, Roza, Ori, Jakhar, Rodrigues-Silva and Banerjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sheikh Shoib, U2hlaWtoc2hvaWIyMkBHbWFpbC5jb20= orcid.org/0000-0002-3739-706X; Fahimeh Saeed, RmEuc2FlZWRAdXN3ci5hYy5pcg== orcid.org/0000-0002-0214-3887

Sheikh Shoib

Sheikh Shoib Miyuru Chandradasa

Miyuru Chandradasa Fahimeh Saeed

Fahimeh Saeed Aishatu Yusha’u Armiya’u

Aishatu Yusha’u Armiya’u Thiago Henrique Roza

Thiago Henrique Roza Dorottya Ori

Dorottya Ori Jitender Jakhar

Jitender Jakhar Nuno Rodrigues-Silva

Nuno Rodrigues-Silva Debanjan Banerjee

Debanjan Banerjee