- The Loss, Crisis, and Resilience in a Multicultural Lens Research Lab, Faculty of Psychology, Achva Academic College, Shikmim, Israel

Introduction

Coping with grief after loss has been at the forefront of concerns amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (1–3). In a recent study (4), it was estimated that due to the pandemic more than 1.5 million children globally lost a caregiver. Childhood bereavement may profoundly impact child development (5). It is associated with heightened risks of impaired academic and social performance (6), mental health issues (7, 8), substance use disorders (9), and higher mortality rates (10). Yet children are at risk of receiving no post-loss support (11–13), as in many countries there are no structured, official guidelines regarding different caregivers' roles. Scholars have thus advocated the need to define and clarify the roles of teachers and other school staff, such as SMPs (14).

This paper draws upon the well-established concepts of Winnicott, who significantly contributed to the field of child development. Applying Winnicott's perspective on the role of the caregiver dyad (i.e., parents), I would suggest an analogy between the father-mother role (when supporting the evolving infant's development) and the dyadic SMP-teacher role, to conceptualize what I believe should be the role of each of these two entities when working together to support grieving children's development.

Childhood bereavement and caregivers' roles

According to childhood bereavement estimation models in the US, by age 18, one in 14 children (7.2%) will experience the death of a parent or sibling (15), and 90% will experience the death of a close friend or relative (5). A review (16) indicated that bereaved children are particularly vulnerable and that adequacy of care from those around the child is essential to their healthy development.

SMPs' role in the context of childhood bereavement

Scholars (5) argue that school mental-health professionals (SMPs) are well-suited to identify and support grieving students; to provide guidance to peers; and to offer teachers' training. Yet instances of loss and trauma are constantly occurring worldwide, resulting in SMPs facing continuous stress and emotional overload (17), potentially preventing them from being available to bereaved children and turning teachers into the main school caregivers.

Teacher's role in the context of childhood bereavement

Seventy percent of American teachers reported having at least one grieving student in their classroom (18). Although school-based support has been found to facilitate grieving students' adjustment both in the US (5) and Europe (19, 20), school support is not coordinated (21). In fact, the question regarding teachers' role is controversial. On the one hand, the school is argued to be a “secure secondary family,” and that educators are well-placed to monitor mental health, and support academic and social issues (22–25). On the other hand, studies showed (14) that although most teachers recognized the need to acknowledge children's grief, they claimed that they were not trained to do so, and were overloaded with pedagogical tasks. Hence, a “crisis plan,” for which the entire school personnel team is trained and prepared to implement, is needed (26). Yet, to build such a plan, conceptualizations must be formulated about the different roles of different school personnel in order to best integrate these role expectations into practice.

Winnicott's viewpoint on caregivers' roles

D.W. Winnicott, a British pediatrician, made significant contributions to the field of child development. A well-known metaphor developed by Winnicott is the “holding environment”—the emotional and physical space provided by the caregiver, typically the mother, protecting the baby by holding him/her in her arms. The caregiver provides an environment that literally and figuratively holds the child, enabling the infant to feel safe. A holding space therefore means being fully present, as one sits with another through a difficult time.

In terms of who provides a holding environment for whom, scholars (27, 28) have argued that, according to Winnicott (29), the father's role with the newborn is protecting the mother-child relationship. He provides a secure environment for the mother, enabling her to provide a nurturing environment for the baby. The father can offer both physical (practical) support, and emotional support, allowing the mother to cope better with motherhood's frustrations. In some cases, the father must provide parenting for the mother, if she is struggling with the demands of motherhood (30). Fathers can also serve as a “mother substitute,” providing the baby with sensitive and responsive care, if the mother needs a respite. Eventually, a strong relationship between the father and mother provides the infant with security—a “rock to which he can cling” (29).

I thus wish to argue that, in the school setting, the role of the SMP should be similar to that of the father, in accordance with Winnicott's claim that “as the mother feels supported, she can better respond to the infant's needs.” Namely, the SMP should support the teacher so that the teacher can support the grieving student.

The voices of grieving students and their teachers

In my prior extensive research on issues of grief and childhood bereavement, and particularly among teachers1 (23, 24, 31–33), I have interviewed both teachers and students and noted that although SMPs are expected to provide support, the students themselves often don't want it. In fact, they tend to prefer to be supported by their teachers since they have prior relationship with them. Furthermore, considering the social stigma around requesting help from SMPs, students are sometimes reluctant to approach them at school, as opposed to teachers, with whom a conversation is perceived as “normal.” With regard to teachers, they often perceive their roles as child-supporters, yet they often say they need support themselves in order to continuously support their students. In a recent study teachers reported of three support needs when managing pediatric grief: knowledge—both theoretical and practical, acknowledgment of their own emotional coping, and support from mental health professionals in school (23). Other studies emphasized the need for clear policy and the importance of school community when managing pediatric grief in school (21, 34).

Discussion: who should support grieving children at school?

Grieving children have various support needs from school, such as support in academic and social challenges aroused by the grief that require long-term support (34). Similarly, teachers report of having various needs when supporting their grieving students (23). So, looking at the broader picture, what is the role of SMPs and teachers in the context of pediatric grief in school? Who and how should support grieving children in school?

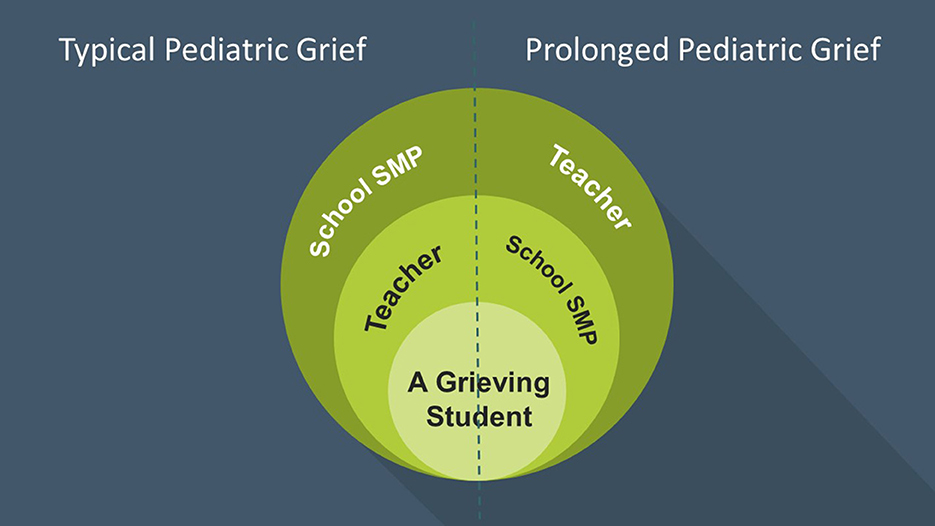

It seems that the most reasonable and effective way to help the grieving child is to provide a holding environment similar to that suggested by Winnicott: The SMPs should support the teachers by offering both practical and emotional support, so that the teachers can better support the grieving child. Nevertheless, as teachers are not trained to be therapists, this arrangement should only be applied in the context of “typical” grief reactions. If a child presents a prolonged grief (i.e., complicated grief), and/or needs extensive professional therapy, then the SMP would be the primary caretaker and the teacher the secondary one. This notion accords with Winnicott's claim that the father can also be a “primary caregiver” when needed.

Figure 1 illustrates the roles of SMPs and teachers in pediatric grief situations. In a “normal” grief situation the teacher envelops the grieving student while being enveloped by the SMP. In a “prolonged” grief situation, the situation is reversed.

This suggested model aligns with the claim that children are more likely to open up to a teacher they know and trust, as well as with studies showing the importance of school leadership supporting school personnel (35). Yet this model's innovation lies in its unique conceptualization drawn upon Winnicott's viewpoint, enabling a better use of resources when managing pediatric grief in schools.

Implications

This conceptualization has several implications. First, teachers should receive training focused on the child's understanding of death and the child's grief-needs, whereas SMPs should receive training focused not only on the child's understanding/needs but also on the teachers' needs in coping with supporting these students. The difference is analogous to that between being trained to become a therapist vs. being trained to become a supervisor. Another implication involves policy. Specifically, in most cases, SMPs should provide support to teachers, and teachers should provide support to students. This leads to a more economic management of grief in school and will also enable SMPs to be truly available in cases of “complicated grief.”

In conclusion, the conceptualized model may substantially contribute to the effective support of bereaved children at school. It may also promote policy changes that clarify caregivers' unique roles and practices, to optimally support grieving children's development.

Author contributions

RF-L: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This project was conducted in the Loss, Crisis and Resilience in a Multicultural Lens Lab.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Prior research was conducted after receiving Achva Academic College's ethic committee's approval (no. 153)

References

1. Frei-Landau R. When the going gets tough, the tough get - creative: Israeli Jewish religious leaders find religiously innovative ways to preserve community members' sense of belonging and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S568. doi: 10.1037/tra0000822

2. Kozato N, Mishra M, Firdosi M. New-onset psychosis due to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. (2021) 14:e242538. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242538

3. Moideen S, Thomas R, Kumar PS, Uvais NA, Katshu MZ. Psychosis in a patient with anti-NMDA-receptor antibodies experiencing significant stress related to COVID-19. Brain, Behav Immun Health. (2020) 7:100125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100125

4. Hillis SD, Unwin HJ, Chen Y, Cluver L, Sherr L, Goldman PS, et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. Lancet. (2021) 398:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8

5. Schonfeld DJ, Demaria TP. The role of school psychologists in the support of grieving children. School Psychol Quart. (2018) 33:361–2. doi: 10.1037/spq0000286

6. Brent DA, Melhem NM, Masten AS, Porta G, Payne MW. Longitudinal effects of parental bereavement on adolescent developmental competence. J Clin Child Adoles Psychol. (2012) 41:778–91. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.717871

7. Kaplow JB, Saunders J, Angold A, Costello EJ. Psychiatric symptoms in bereaved versus nonbereaved youth and young adults: a longitudinal epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2010) 49:1145–54. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201011000-00008

8. Margoob MA, Rather YH, Khan AY, Singh GP, Malik YA, Firdosi MM, et al. Psychiatric disorders among children living in orphanages—Experience from Kashmir. JK-Practitioner. (2006) 13:S53–S55.

9. Otowa T, York TP, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Hettema JM. The impact of childhood parental loss on risk for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders in a population-based sample of male twins. Psychiat Res. (2014) 220:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.053

10. Li J, Vestergaard M, Cnattingius S, Gissler M, Bech BH, Obel C, et al. Mortality after parental death in childhood: A nationwide cohort study from three Nordic countries. PLoS Med. (2014) 11:e1001679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001679

11. Albuquerque S, Santos AR. “In the same Storm, but not on the same Boat”: children grief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:638866. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638866

12. Shalev R, Dargan C, Abdallah F. Issues in the treatment of children who have lost a family member to murder in the Arab community in Israel. OMEGA-J Death Dying. (2021) 83:198–211. doi: 10.1177/0030222819846714

13. Weinstock L, Dunda D, Harrington H, Nelson H. It's complicated—adolescent grief in the time of COVID-19. Front Psychiat. (2021) 12:638940. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638940

14. Dyregrov A, Dyregrov K, Idsoe T. Teachers' perceptions of their role facing children in grief. Emot Behav Diffic. (2013) 18:125–134. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2012.754165

15. Burns M, Griese B, King S, Talmi A. Childhood bereavement: understanding prevalence and related adversity in the United States. Am J Orthopsychiat. (2020) 90:391–405. doi: 10.1037/ort0000442

16. Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. (2007) 370:1960–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9

17. Levkovich I, Ricon T. Understanding compassion fatigue, optimism and emotional distress among Israeli school counsellors. Asia Pacific J Counsel. (2020) 11:159–80. doi: 10.1080/21507686.2020.1799829

18. American Federation of Teachers. Grief in the Classroom. New York Life Foundation (2012). Available online at: https://www.newyorklife.com/assets/foundation/docs/pdfs/NYL-AFT-Bereavement-Survey.pdf

19. Dyregrov A, Dyregrov K, Lytje M. Loss in the family – A reflection on how schools can support their students. Bereav Care. (2020) 39:95–101. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2020.1828722

20. McLaughlin C, Lytje M, Holliday C. Consequences of childhood bereavement in the context of the British school system. Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. (2019).

21. Dimery E, Templeton S. Death, bereavement and grief: the role of the teacher in supporting a child experiencing the death of a parent. Practice. (2021) 3:146–65. doi: 10.1080/25783858.2021.1882263

22. Frei-Landau R. Lost When Facing Loss: Why Educate Teachers about Loss Death? [Video]. TEDx (2021). Available online at: https://www.ted.com/talks/dr_rivi_frei_landau_lost_when_facing_loss_why_educate_teachers_about_loss_and_death

23. Frei-Landau R, Mirsky C, Sabar-Ben-Yehoshua N. Teachers' coping with grieving children during the COVID-19 pandemic. In:Peleg O, Shalev R, Hadar E, , editors. Educational Counseling in Stressful Life Events, Crisis and Emergency. Pardes Publishing (2023).

24. Frei-Landau R, Abu-Much A, Sabar-Ben Yehoshua N. Religious meaning making of Muslim parents bereaved by homicide: Struggling to accept 'God's will' and longing for ‘Qayama' day. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e20246. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20246

25. Holland J, Wilkinson S. A comparative study of the child bereavement response and needs of schools in North Suffolk and Hull, Yorkshire. Bereavement Care. (2015) 34:52–8. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2015.1063858

26. Lytje M. The success of a planned bereavement response–a survey on teacher use of bereavement response plans when supporting grieving children in Danish schools. Pastoral Care Educ. (2017) 35:28–38. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2016.1256420

27. Faimberg H. The paternal function in Winnicott: The psychoanalytical frame. Int J Psychoanaly. (2014) 95:629–40. doi: 10.1111/1745-8315.12236

28. Reeves C. On the margins: The role of the father in Winnicott's writings. In: Donald Winnicott today. Routledge (2012). p. 358–85.

29. Winnicott DW. The theory of the parent-infant relationship. In:Winnicott DW, , editor. The maturational processes of the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development. International Universities Press (1960). p. 37–55. doi: 10.4324/9780429482410-3

30. Tuttman S. The father's role in the child's development in the capacity to deal with separation and loss. J Am Acad Psychoanaly. (1986) 14:309–22. doi: 10.1521/jaap.1.1986.14.3.309

31. Frei-Landau R, Tuval-Mashiach R, Silberg T, Hasson-Ohayon I. Attachment to god among bereaved Jewish parents: Exploring differences by denominational affiliation. Rev Relig Res. (2020) 62:485–96.

32. Frei-Landau R, Hasson-Ohayon I, Tuval-Mashiach R. The experience of divine struggle following child loss: the case of Israeli bereaved Modern-Orthodox parents. Death Stud. (2022) 46:1329–43.

33. Levitan F, Frei-Landau R, Sabar-Ben-Yehoshua NA. “I Just Needed a Hug”: culturally-based disenfranchised grief of Jewish ultraorthodox women following pregnancy loss. OMEGA-J Death Dying. (2022) doi: 10.1177/00302228221133864

34. Lytje M. Voices we forget—Danish students experience of returning to school following parental bereavement. OMEGA-J Death Dying. (2018) 78:24–42. doi: 10.1177/0030222816679660

Keywords: Winnicott, mental health, loss, pediatric grief, school-based support

Citation: Frei-Landau R (2023) Who should support grieving children in school? Applying Winnicott's viewpoint to conceptualize the dyadic roles of teachers and school mental-health professionals in the context of pediatric grief. Front. Psychiatry 14:1290967. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1290967

Received: 08 September 2023; Accepted: 19 October 2023;

Published: 06 November 2023.

Edited by:

Mushtaq Ahmad Margoob, Government Medical College (GMC), IndiaReviewed by:

Stella Laletas, Monash University, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Frei-Landau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rivi Frei-Landau, cml2aXBzeUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Rivi Frei-Landau

Rivi Frei-Landau