- 1Department of Psychiatry and Narcology, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia

- 2Residency in Psychiatry Program, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia

Background: The emergence of a new coronavirus strain caused the COVID-19 pandemic. While vaccines effectively control the infection, it’s important to acknowledge the potential for side effects, including rare cases like psychosis, which may increase with the rising number of vaccinations.

Objectives: Our systematic review aimed to examine cases of new-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of case reports and case series on new-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination from December 1st, 2019, to November 21st, 2023, using PubMed, MEDLINE, ClinicalKey, and ScienceDirect. Data extraction covered study and participant characteristics, comorbidities, COVID-19 vaccine details, and clinical features. The Joanna Briggs Institute quality assessment tools were employed for included studies, revealing no significant publication bias.

Results: A total of 21 articles described 24 cases of new-onset psychotic symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination. Of these cases, 54.2% were female, with a mean age of 33.71 ± 12.02 years. Psychiatric events were potentially induced by the mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in 33.3% of cases, and psychotic symptoms appeared in 25% following the viral vector ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. The mean onset time was 5.75 ± 8.14 days, mostly reported after the first or second dose. The duration of psychotic symptoms ranged between 1 and 2 months with a mean of 52.48 ± 60.07 days. Blood test abnormalities were noted in 50% of cases, mainly mild to moderate leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein. Magnetic resonance imaging results were abnormal in 20.8%, often showing fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity in the white matter. Treatment included atypical antipsychotics in 83.3% of cases, typical antipsychotics in 37.5%, benzodiazepines in 50%, 20.8% received steroids, and 25% were prescribed antiepileptic medications. Overall, 50% of patients achieved full recovery.

Conclusion: Studies on psychiatric side effects post-COVID-19 vaccination are limited, and making conclusions on vaccine advantages or disadvantages is challenging. Vaccination is generally safe, but data suggest a potential link between young age, mRNA, and viral vector vaccines with new-onset psychosis within 7 days post-vaccination. Collecting data on vaccine-related psychiatric effects is crucial for prevention, and an algorithm for monitoring and treating mental health reactions post-vaccination is necessary for comprehensive management.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier CRD42023446270.

1 Introduction

The end of 2019 was marked by an event that radically changed the lives of all humanity. The appearance of a new strain of coronavirus, subsequently termed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), led to a pandemic of the disease called COVID-19. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, as of October 2023, there have been 771,191,203 confirmed cases of COVID-19 globally, including 6,961,014 deaths (1).

As a result, there was a critical need to focus on vaccinating the population against SARS-CoV-2 infection, reducing the risk of severe disease and mortality. The first vaccine, the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine COMIRNATY (mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine), was approved by the WHO in December 2020. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization for COVID-19 vaccines and full approval for the Pfizer vaccine to control the pandemic. The WHO has also recommended other vaccines for COVID-19 produced by numerous pharmaceutical companies (2). Vaccines against COVID-19 differ in composition and mechanism of action, which may be relevant for their safety and efficacy (3). As of October 2023, the WHO reported a total of 13,516,185,809 vaccine doses administered (1).

Despite the widespread use and high effectiveness of vaccines in controlling COVID-19 infection, it is crucial to consider the possibility of side effects. To date, no vaccine can be claimed to be completely free of adverse events, but fortunately, the majority of them are either preventable or treatable (4). Most early side effects, such as fever, pain, myalgias, headaches, and local or injection side effects, are related to the immune response and are considered common (5). However, several studies have demonstrated cardiac, gastrointestinal, neurological, and psychiatric side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccines (6–10). The recent review describes 14 cases of altered mental states, psychosis, affective, and functional neurological disorders as psychiatric and neuropsychiatric adverse reactions to mRNA or vector-based COVID-19 vaccines (11). As the number of vaccinated people increases, so does the number of reported cases of rare vaccine-related side effects, such as psychosis. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to examine cases of new-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination with all types of vaccines. It is worth noting that our study is the first of its kind, and, in prospect, will help expand the understanding of rare and clinically significant side effects of COVID-19 vaccines.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

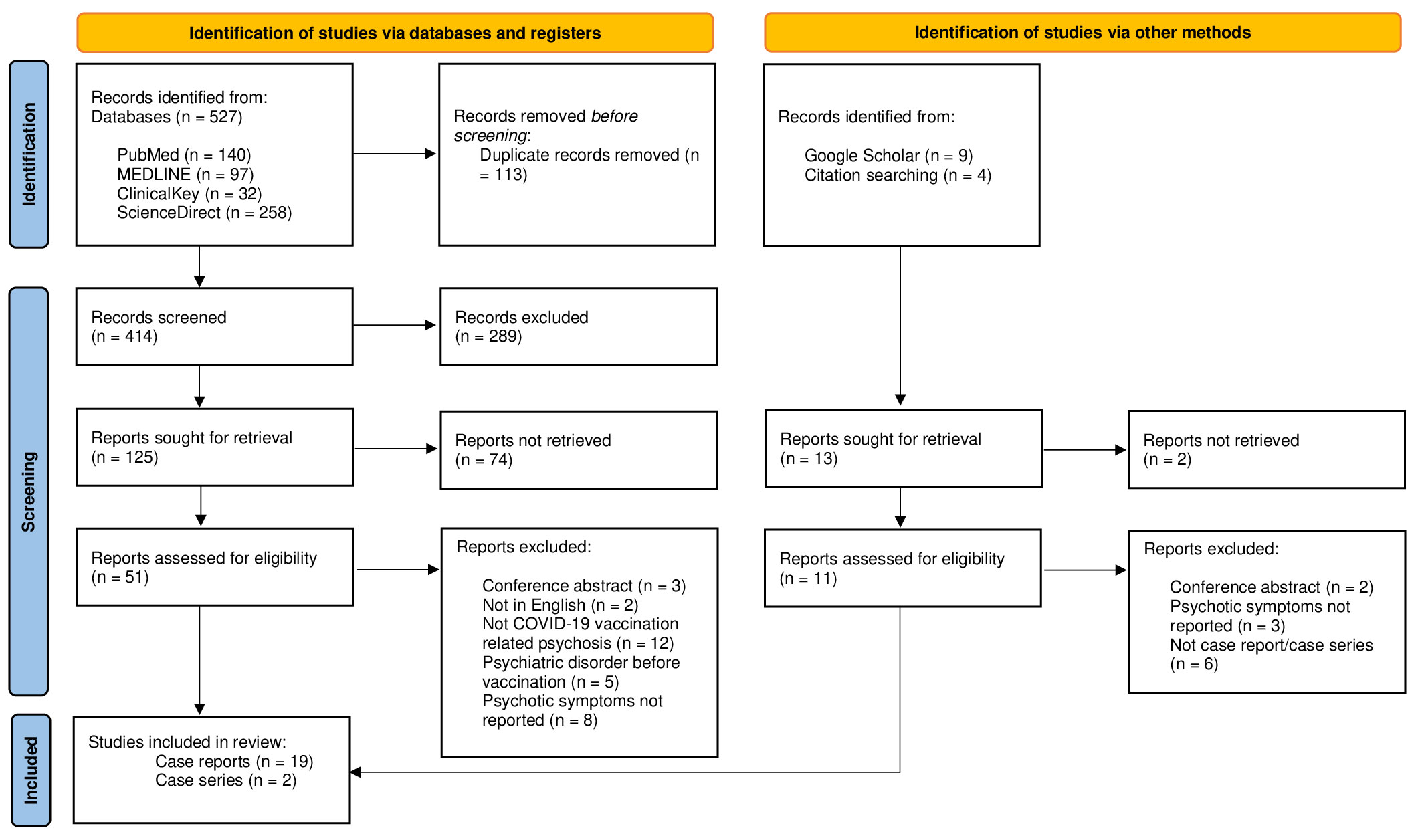

The present study systematically reviewed the case reports and case series of new-onset psychosis associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database with ID number: CRD42023446270. A systematic search was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (12).

2.2 Search strategy

For the review, the following databases for relevant English language literature were searched: PubMed, MEDLINE, ClinicalKey, and ScienceDirect. Studies were restricted to those published from December 1st, 2019 (the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak) to November 21st, 2023. A systematic search was carried out to select studies that corresponded to the inclusion and exclusion criteria using keywords, generic filters, and MeSH terms in the referred databases, following the PRISMA guidelines. The electronic database search was supplemented by a manual search of the reference lists of included articles and Google Scholar.

The following keywords for search strategy were used: COVID-19 vaccine* OR SARS-CoV-2 vaccine* OR coronavirus vaccine* OR mRNA vaccine* OR BNT162b2 vaccine* OR viral vector vaccine* OR ChAdOx1-S/nCoV-19 vaccine* OR Ad26.COV2.S vaccine* OR Whole-virion inactivated vaccine* OR BBV152 vaccine* AND psychosis OR psychotic disorders OR psychiatric disorders OR neuropsychiatric OR hallucinations OR mania OR delusions OR schizophrenia OR mental disorders OR psychomotor disorder OR confusion OR delirium OR agitation.

The following inclusion criteria were used: all studies conducted in primary, secondary, and tertiary care settings, with no restrictions on the location of the healthcare setting; eligible studies must include all patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine and exhibited psychotic symptoms according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V or the International Classification of Diseases 10/11, with no restrictions on gender, age, or race.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: reviews, clinical trials, letters to the editor, editorials, interviews, newspaper articles, comments, studies without sufficient data, duplicate sources, as well as studies with only a published abstract. Additionally, studies that included patients with diagnosed psychiatric disorders/psychotic symptoms before COVID-19 vaccination or patients with no history of COVID-19 vaccination were excluded.

2.3 Data extraction and analysis

The study selection process involved two stages: initially, two independent reviewers (M.L., L.R.) screened study titles, and then the full texts of the selected articles were independently assessed for eligibility. Articles failing to meet the inclusion criteria or those that were unavailable were excluded by the reviewers. The screening results and data extraction underwent verification by two additional reviewers (J.V., E.R.), who were not part of the initial screening and extraction process. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Reviewers extracted data from the primary studies in the following domains: 1) study characteristics (i.e., principal author, country, year of publication, study design), 2) characteristics of participants (i.e., age and gender), 3) comorbidities (i.e., history of somatic disorders), 4) characteristics of the COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., type and name, dose of vaccine after which psychotic symptoms appeared), 5) clinical characteristics (time to psychotic symptoms from vaccine administration, morbidity and/or diagnosis, laboratory findings and/or imaging, duration of psychotic episode, medications used, and outcome).

Descriptive analysis of the available information was performed using descriptive statistics to report demographics and clinical characteristics. Authors reported the onset and duration of symptoms as a range due to inconsistent and approximate reporting of this information across studies.

2.4 Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment tools were used for the case reports and case series included in our study (13, 14). The quality of the included studies was assessed by two authors, and conflicts were resolved by consensus. For case reports, JBI domains included eight questions, and for assessing case series, ten questions were used. Quality assessment was carried out in the following categories: 75-100% low risk; 50-74% moderate risk; <50% high risk.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics

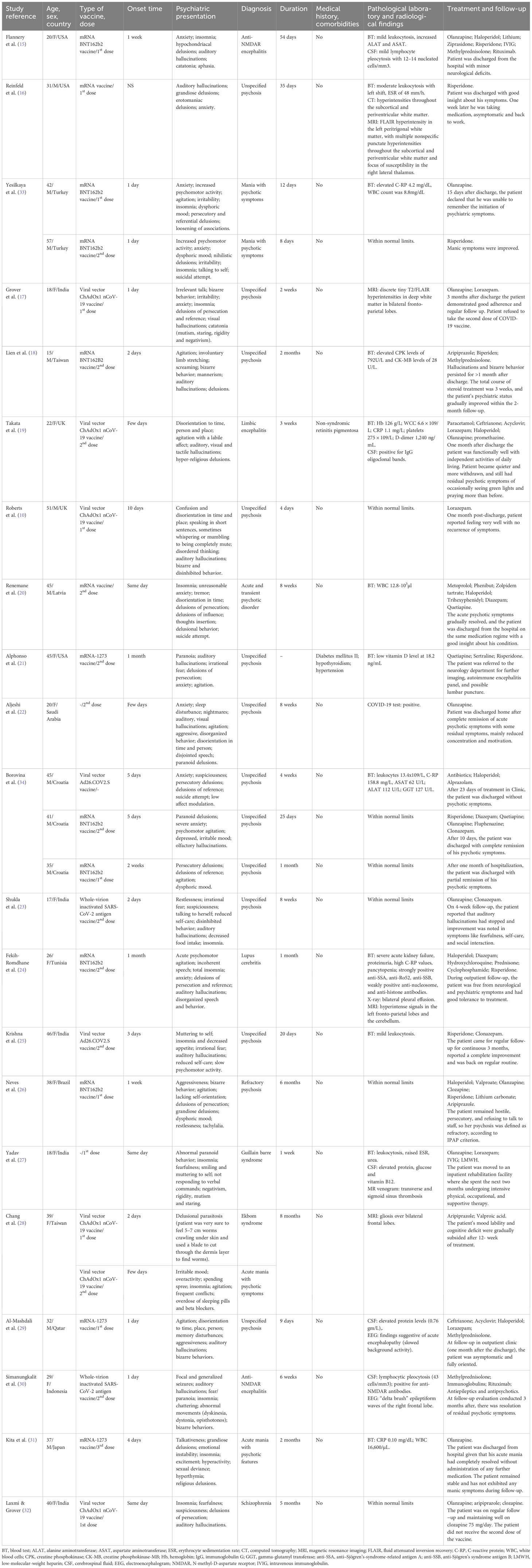

A total of 21 articles (10, 15–34) describing 24 cases of new-onset psychotic symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination were retrieved from PubMed, MEDLINE, ClinicalKey, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar (see Figure 1). All studies were in English, and the largest number of cases were reported in the United States of America (12%) and India (20%) (see Table 1).

3.2 Patients’ characteristics

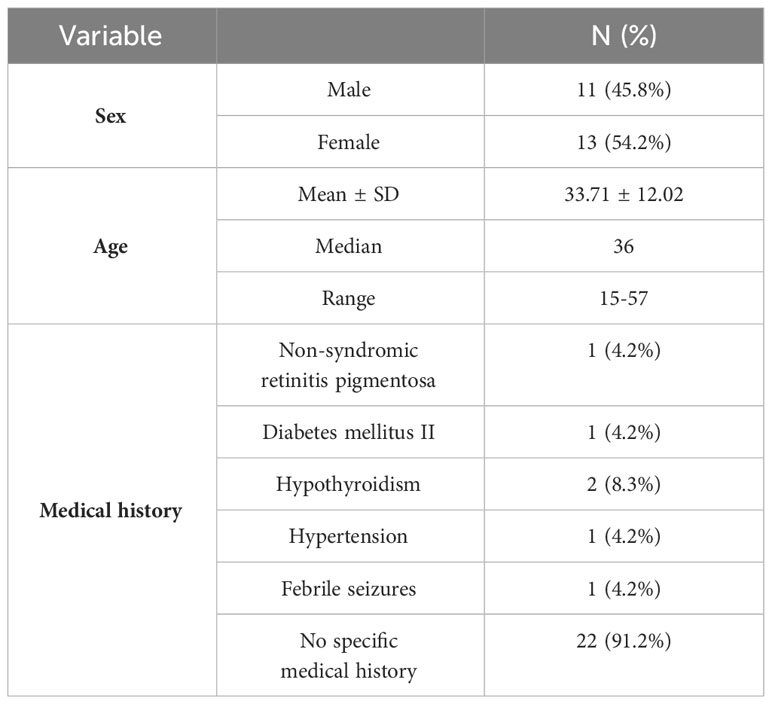

Out of the 24 cases, 13 were female (54.2%), and the mean age across all participants was 33.71 ± 12.02 years, with a median of 36 years. A total of 22 (91.2%) patients had no specific history of somatic illness and comorbidities (see Table 2).

Table 2 The demographic data and medical history of respondents with new-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination.

3.3 Vaccine characteristics

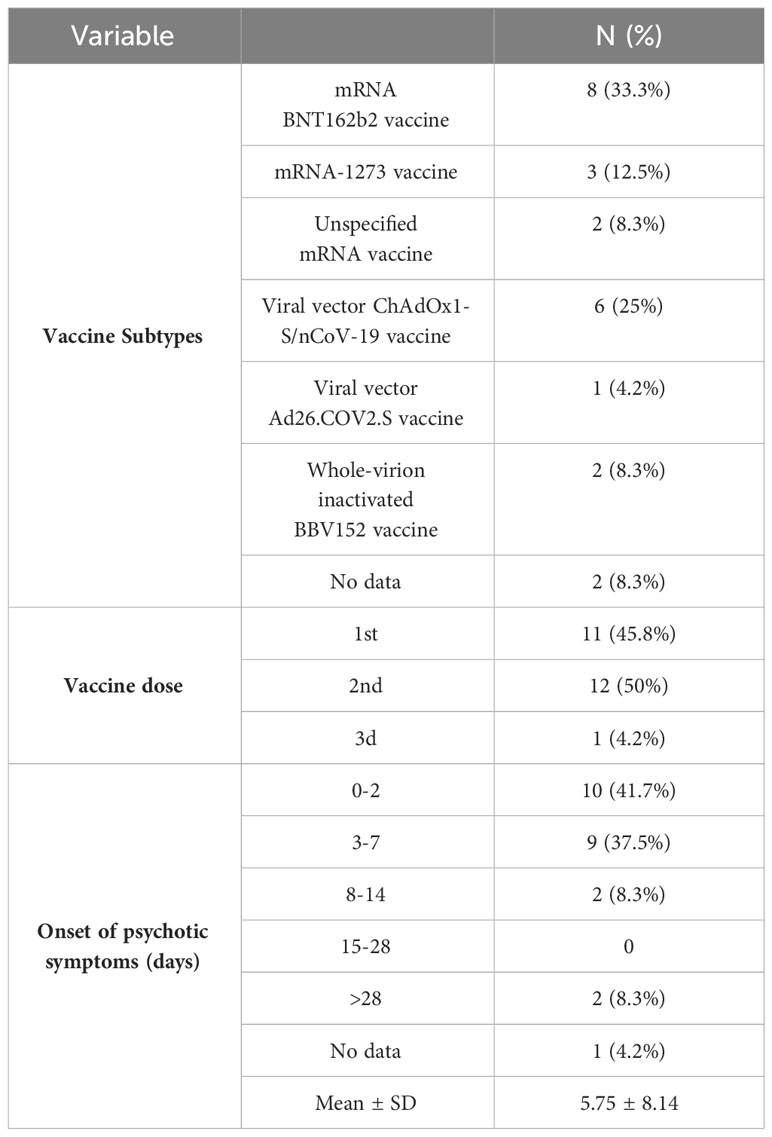

Administration of the mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine potentially induced adverse psychiatric events in 33.3% of cases, while psychotic symptoms appeared in 25% of cases following the viral vector ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. The mean time for the onset of psychotic symptoms was 5.75 ± 8.14 days, which, in most cases, was reported after the first (45.8%) or the second dose (50%), followed by the third dose (4.2%). There was no data on the onset of adverse events in 4.2% of cases (see Table 3).

Table 3 Characteristics of vaccines and onset of psychotic symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination .

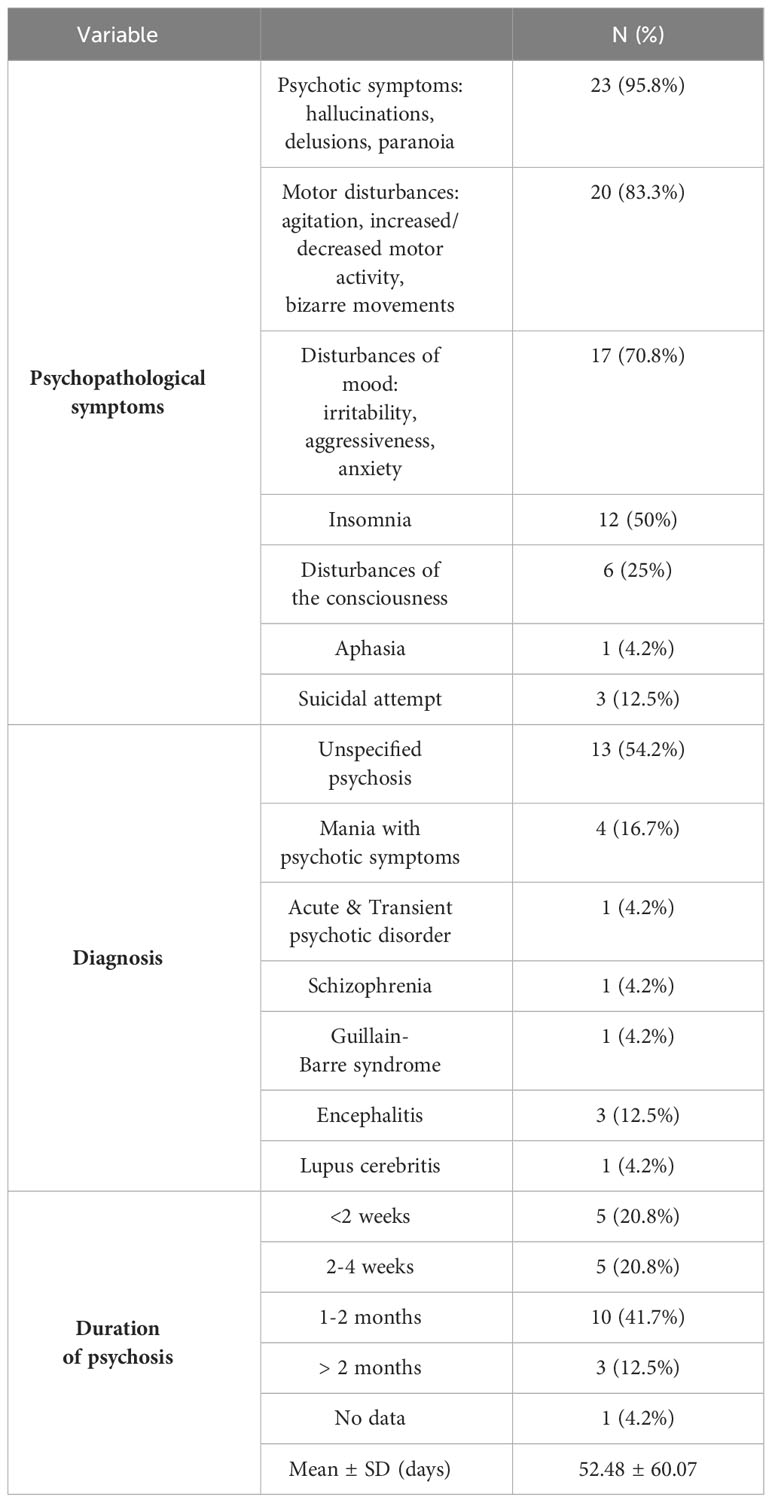

3.4 Clinical characteristics

Almost all reviewed cases (95.8%) presented with psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations (visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile) and delusions (mostly persecutory and delusions of reference). The most occurring form of hallucinations was auditory (54.2%), while visual hallucinations were present in 12.5% of cases. Motor disturbances, such as increased or decreased motor activity and bizarre behavior, were mentioned in 83.3% of cases. In 3 (12.5%) cases, a suicidal attempt was described. The largest number of patients presented with unspecified psychosis (54.2%), while mania with psychotic symptoms was detected in 16.7%. The duration of psychotic symptoms was mostly between 1 and 2 months (41.7%) with a mean of 52.48 ± 60.07 days. Details of patients’ clinical presentations are available in Table 4.

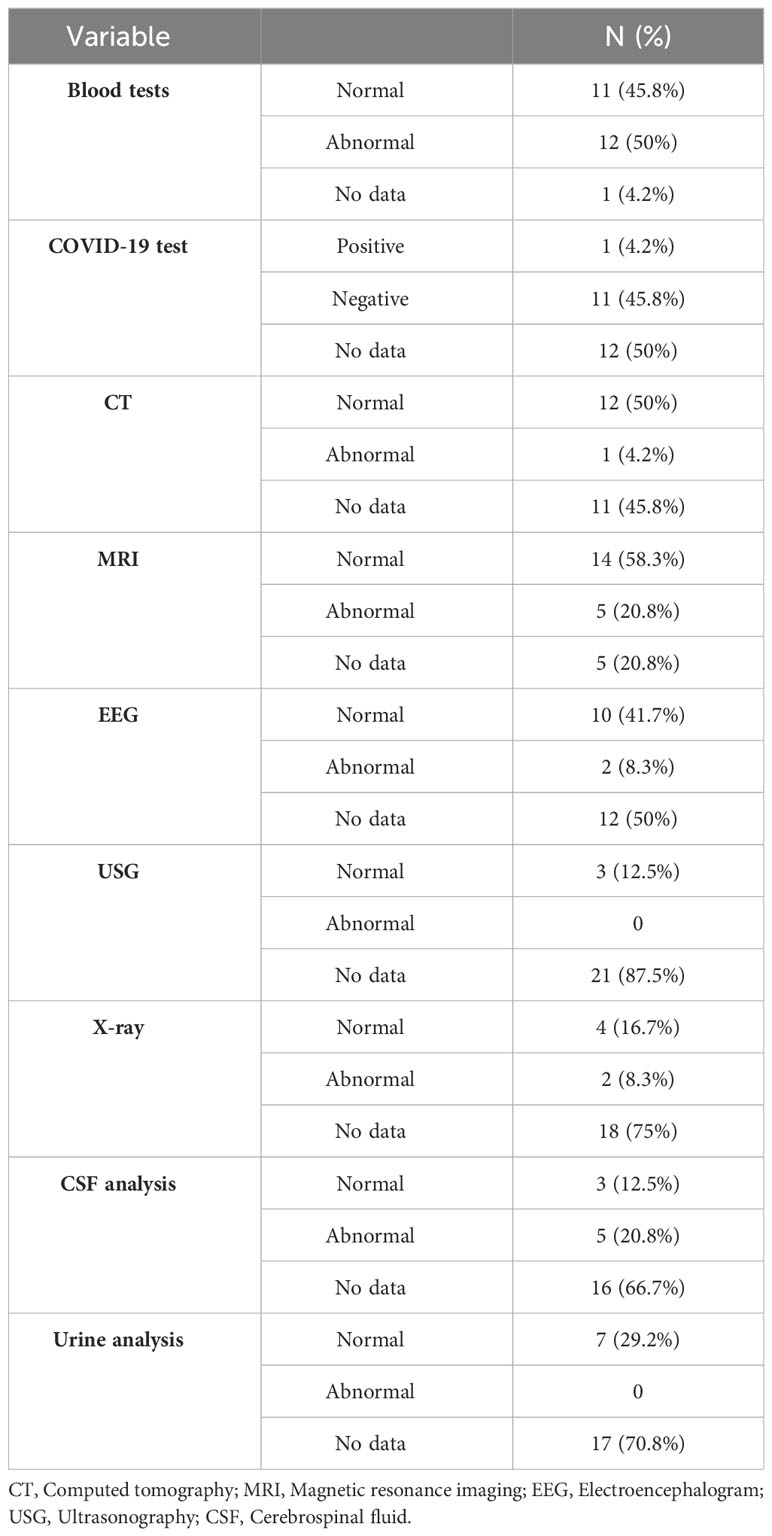

3.5 Laboratory and radiological findings

Results of laboratory and radiological tests were mostly available for blood tests and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Abnormalities in blood tests were described in 50% of cases, with the most common being mild to moderate leukocytosis and an elevated C-reactive protein (C-RP) level. MRI results were abnormal in 20.8%, and in most cases, they showed fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity in the white matter. In some cases, lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed elevated protein levels, lymphocytic pleocytosis, positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) oligoclonal bands, and high interleukin (Il)-1 beta. There was one case with a positive COVID-19 test (see Table 5).

3.6 Treatment and outcome

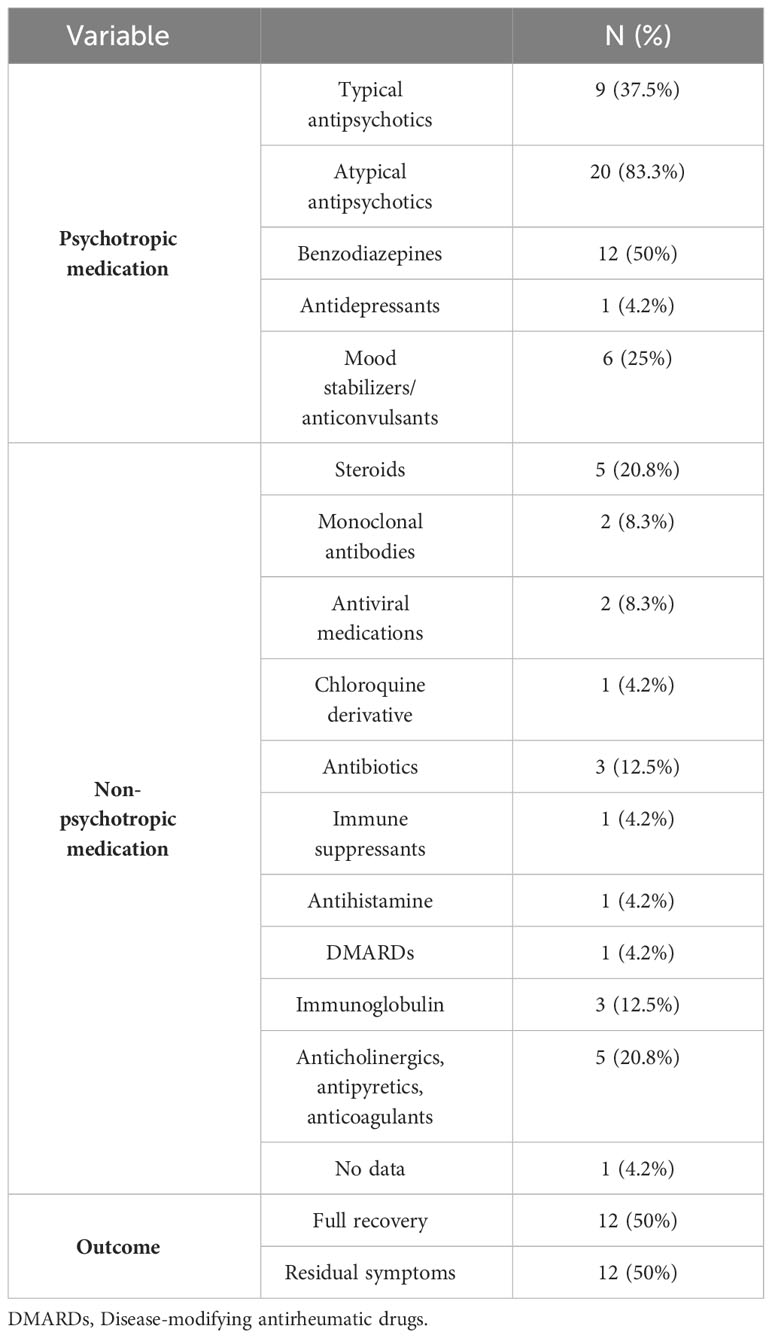

Almost all (83.3%) patients with psychotic symptoms received atypical antipsychotics for medical treatment, while typical antipsychotics were prescribed in 37.5% of cases, and benzodiazepines in 50% of cases. Additionally, 20.8% of patients received steroids, and 25% were prescribed antiepileptic medications. Overall, 12 patients made a full recovery (50%), while other 50% had residual symptoms such as decreased emotional expressions, low affect, or residual psychotic symptoms (see Table 6).

Table 6 Therapeutic approach and outcome for patients with new-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination.

3.7 Quality assessment

Nineteen case reports and two case series were assessed using the JBI checklist. All case reports (n = 19) had a low risk of bias, while both case series had a moderate risk of bias. Data are shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 2.

4 Discussion

The first COVID-19 vaccine was introduced in December 2020, marking the beginning of the fight against the pandemic (35). Currently, available vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are produced using one of the following technologies: (a) mRNA-based vaccines, (b) viral vector-based vaccines, (c) protein subunit vaccines, and (d) whole virus or inactivated virus vaccines (36–38). More than 13 billion vaccine doses have been administered to date, according to the World Health Organization (1).

Our study of published case reports indicates a marginal disparity in the onset of primary psychosis post-COVID-19 vaccinations between genders. Among the cases reviewed, 54.2% involved females, and 45.8% involved males. Previous cohort studies and reviews have reported an association between the female gender and a higher incidence of side effects following COVID-19 vaccination. These effects encompass typical local and systemic reactions, notably redness, swelling, fever, muscle pain, headache, or anaphylaxis (39, 40). However, a comprehensive systematic review assessing the global incidence of psychotic disorders revealed a cumulative frequency of 26.6 per 100,000 individuals, with men being at a higher risk for all psychotic disorders (41).

Based on the demographic data obtained, the average age of those susceptible to primary psychosis after vaccination is 36 years, with a range of 15 to 57 years. This observation is consistent with results from phase 3 randomized controlled trials and federally sponsored surveillance programs evaluating the safety and efficacy of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. These studies revealed that both injection-site and systemic adverse events were more prevalent among younger participants aged 18 to less than 65 years (42, 43). Nevertheless, it’s crucial to note the controversial comparison between common side effects following vaccination and rare side effects, such as primary psychosis. Additionally, previous studies indicate that the onset of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders commonly occurs between the ages of 15 and 35 years (44). It is crucial to emphasize that cases of post-vaccination psychosis necessitate careful follow-up for the potential development of schizophrenia.

In the majority of cases, applicants lacked a specific medical history pertaining to potential comorbidities. It is worth noting that in one of the described cases, a positive COVID-19 test was obtained. Previous studies have shown that individuals with documented comorbidities and a history of COVID-19 infection exhibit a statistically significant increase in adverse events following vaccination (45, 46).

The average duration of psychosis in the described cases was 52.48 ± 60.07 days. Most authors refrain from specifying a particular diagnosis according to any classification, instead presenting cases of unspecified psychosis characterized by several symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and insomnia. Although it is challenging to determine the nature of psychosis in these cases, whether it aligns more with organic mental disorders or within schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Guidelines for the treatment of psychosis and schizophrenia recommend starting treatment with antipsychotic medications, and the choice of antipsychotic drug depends on numerous patient-specific factors (47, 48). According to findings from another study, there appears to be no difference in effectiveness between atypical and typical antipsychotics in the treatment of primary psychosis, but there exists a distinct difference in the side effect profiles (49). Likewise, our study revealed that in the majority of new-onset psychosis cases subsequent to COVID-19 vaccination, atypical antipsychotics (83.3%) were prescribed as the primary pharmacological treatment. In cases of diagnosed or suspected autoimmune encephalitis, steroids were most frequently utilized (20.8%), either as monotherapy or in combination with antipsychotics. It is important to note that, according to the results of our review, 50% of the described cases achieved full recovery, while the second part of the patients retained some residual symptoms. Also, based on the available information, continuation of therapy in the prescribed regimen was necessary in 58.3% of cases, with an average duration of ≥3 months with regular check-ups, which also aligns with clinical guidelines.

Based on the outcomes of our review, the onset of primary psychosis occurred in most cases following vaccination with the mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine (33.3%), closely followed in frequency by cases of new-onset psychosis following vaccination with the viral vector ChAdOx1nCoV-19 vaccine (25%). Previous comparisons have demonstrated that viral vector vaccines tend to be associated with more systemic side effects compared to mRNA vaccines (50). It’s essential to highlight that in the United States and Europe, the mRNA vaccine has been administered in the vast majority of cases (51, 52). However, the results of the clinical study on systemic allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccination showed that hallucinations were observed in only 0.81% of cases as a psychiatric side effect following the administration of a placebo and subsequent two doses of the mRNA-1273 vaccine (53). This variance in vaccine administration statistics could potentially influence the prevalence of reported side effects, the number of publications, and available data regarding adverse effects associated with each vaccine type.

The majority of patients experienced psychosis following the administration of the first (45.8%) and second (50%) vaccine doses, with noticeable variation in the incidence of primary psychosis after receiving the third dose (4.2%). In general, symptoms manifested rapidly within 0-7 days after vaccination. Enhanced monitoring of psychiatric side effects in the initial weeks following COVID-19 vaccination may be advisable.

According to available data, the occurrence of psychosis following vaccination may be mediated by the body’s immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, vaccine administration induces a cellular immune response, triggering T-helper cell-mediated release of proinflammatory cytokines. In some instances, this cascade may lead to cytokine storms and hypofunction of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Consequently, elevated dopamine levels may result, potentially precipitating the development of psychosis (17).

Given the presence of increased inflammatory markers in certain psychiatric disorders (54–56), it is plausible to assume that this inflammatory condition could underlie various neuropsychiatric complications associated with vaccination. Likewise, the results of our study revealed elevated C-RP levels and mild to moderate leukocytosis as the most common blood abnormalities. Furthermore, CSF analysis indicated increased protein levels, lymphocytic pleocytosis, and high levels of Il-1 beta, confirming the activation of the inflammatory cascade as well.

Another hypothesis regarding post-vaccination psychosis suggests that the observed alterations in mental status, including psychotic symptoms, could represent a manifestation of autoimmune anti-NMDA encephalitis (15, 57). Cases of diagnosing anti-NMDA encephalitis were also observed in our review. In turn, instances of anti-NMDA encephalitis development have been repeatedly reported following vaccination against other infections, such as yellow fever, influenza, typhus, and pertussis (58–60). Considering the potential link between post-vaccination psychosis and autoimmune anti-NMDA encephalitis, it is advisable to consider immunological screening in individuals presenting psychiatric symptoms post-COVID-19 vaccination.

It is noteworthy that due to various speculations and uncertainties regarding the safety of COVID-19 vaccines, the population is experiencing significant stress, which could also provoke the development of psychiatric reactions (61, 62).

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, there are only a few published studies to date on psychiatric side effects following COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in small sample sizes. Second, our study included case reports only in English and only full-text studies, which significantly reduces the sample size. Another limitation is that, since there is no data from a matched control group, morbidity or prevalence cannot be calculated properly. Fourth, limitation is that in our review, there was no assessment of the risk of developing psychosis prior to vaccination in the individuals described in the clinical cases, which is associated with the complexity of conducting this task retrospectively.

6 Conclusion

Studies on psychiatric side effects post-COVID-19 vaccination are scarce. Conclusions on vaccine types’ advantages or disadvantages are challenging due to insufficient evidence. Vaccination is generally safe, but data suggest a potential link between young age, mRNA, and viral vector vaccines with new-onset psychosis within 7 days post-vaccination. Collecting data on vaccine-related psychiatric effects is crucial for prevention strategies. An algorithm for monitoring and treating mental health reactions post-vaccination is necessary for comprehensive management of psychiatric complications.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ML: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. LR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. JV: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. ER: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article-processing charge was funded by Riga Stradins University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1360338/full#supplementary-material

References

1. WHO. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO) (2023).

2. WHO. Status of COVID-19 Vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO) (2023).

3. Forni G, Mantovani A, Forni G, Mantovani A, Moretta L, Rappuoli R, et al. COVID-19 vaccines: where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Different. (2021) 28:626–39. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9

4. Spencer JP, Trondsen Pawlowski RH, Thomas S. Vaccine adverse events: separating myth from reality. Am Family phys. (2017) 95:786–94.

5. Abu-Halaweh S, Alqassieh R, Suleiman A, Al-Sabbagh MQ, Abuhalaweh M, Alkhader D, et al. Qualitative assessment of early adverse effects of pfizer–biontech and sinopharm covid-19 vaccines by telephone interviews. Vaccines (Basel). (2021) 9:950. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090950

6. Alonso Castillo R, Martínez Castrillo JC. Neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 vaccine. Neurologia. (2022) S2173-5808(22)00141-9. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2022.09.007

7. Boivin Z, Martin J. Untimely myocardial infarction or COVID-19 vaccine side effect. Cureus. (2021) 13:e1365. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13651

8. Østergaard SD, Schmidt M, Horváth-Puhó E, Thomsen RW, Sørensen HT. Thromboembolism and the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine: side-effect or coincidence? Lancet. (2021) 397:1441–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00762-5

9. Parkash O, Sharko A, Farooqi A, Ying GW, Sura P. Acute pancreatitis: A possible side effect of COVID-19 vaccine. Cureus. (2021) 13:e14741. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14741

10. Roberts K, Sidhu N, Russel M, Abbas MJ. Psychiatric pathology potentially induced by COVID-19 vaccine. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. (2021) 25:8–10. doi: 10.1002/pnp.723

11. Balasubramanian I, Faheem A, Padhy SK, Menon V. Psychiatric adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid review of published case reports. Asian J Psychiatr. (2022) 71:103129. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103129

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

13. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Aromataris E, Sears K, et al. JBI critical appraisal checklist for case reports. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna briggs institute reviewer’s manual. Adelaide, South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute (2017). p. 1–7.

14. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. (2019) 18:1. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

15. Flannery P, Yang I, Keyvani M, Sakoulas G. Acute psychosis due to anti-N-methyl D-aspartate receptor encephalitis following COVID-19 vaccination: A case report. Front Neurol [Internet]. (2021) 12:764197/full. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.764197/full

16. Reinfeld S, Cáceda R, Gil R, Strom H, Chacko M. Can new onset psychosis occur after mRNA based COVID-19 vaccine administration? A case report. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 304:114165. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114165

17. Grover S, Rani S, Kohat K, Kathiravan S, Patel G, Sahoo S, et al. First episode psychosis following receipt of first dose of COVID-19 vaccine: A case report. Schizophr Res. (2022) 241:70–1. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.01.025

18. Lien YL, Wei CY, Liang JS. Acute psychosis induced by mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents: A pediatric case report. Pediatr Neonatol. (2022) 64:364–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2022.10.007

19. Takata J, Durkin SM, Wong S, Zandi MS, Swanton JK, Corrah TW. A case report of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine–associated encephalitis. BMC Neurol. (2021) 21:485. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02517-w

20. Renemane L, Vrublevska J, Cera I. FIRST EPISODE PSYCHOSIS FOLLOWING COVID-19 VACCINATION: A CASE REPORT. Psychiatr Danub. (2022) 34:56–9.

21. Alphonso H, Demoss D, Hurd C, Oliphant N, Davis JK, Rush AJ. Vaccine-induced psychosis as an etiology to consider in the age of COVID-19. Primary Care Companion CNS Disord. (2022) 24:22cr03324. doi: 10.4088/PCC.22cr03324

22. Aljeshi AA, Abdelrahim ASI, Aljeshic MA. Psychosis associated with COVID-19 vaccination. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. (2022) 24(1):21cr03160. doi: 10.4088/PCC.21cr03160

23. Shukla A, Nandan NK, Singh LK. Acute psychosis after immunization with whole-virion inactivated COVID-19 vaccine; A case report from central India. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2023) 43:66–7. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001640

24. Fekih-Romdhane F, Ghrissi F, Hallit S, Cheour M. New-onset acute psychosis as a manifestation of lupus cerebritis following concomitant COVID-19 infection and vaccination: a rare case report. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23:419. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04924-4

25. Krishna J, Harshitha V, Endreddy A, Seshamma Vv. Psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination. Telangana J Psychiatry. (2022) 8:113. doi: 10.4103/tjp.tjp_28_22

26. Neves MV, Simon JJ, Henna Neto J, Hübner C von K, Henna E. Refractoy psychosis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Debates em Psiquiatria. (2023) 13:1–8. doi: 10.25118/2763-9037.2023.v13.432

27. Yadav A, Sehgal V, Ahluwalia I, Patil PS, Ahmed A. A rare case of Guillain barre syndrome with overlapping cerebral sinus venous thrombosis masquerading as acute psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination. Med Sci. (2023) 27. doi: 10.54905/disssi/v27i133/e168ms2806

28. Chang FY, Chen PA, Siao WH, Chen YC. Sequential provocation of Ekbom’s syndrome and acute mania following AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Asian J Psychiatr. (2023) 83:103569. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103569

29. Al-Mashdali AF, Ata YM, Sadik N. Post-COVID-19 vaccine acute hyperactive encephalopathy with dramatic response to methylprednisolone: A case report. Ann Med Surgery. (2021) 69:102803. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102803

30. Simanungkalit AD, Puspitasari V, Margono JT, Tiffani P, Stevano R. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis and myasthenia gravis post-COVID-19 vaccination: cases of possible COVID-19 vaccination-associated autoimmunity. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. (2022) 10:280–4. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2022.10632

31. Kita A, Fuyuno Y, Matsuura H, Yamaguchi Y, Okuhira K, Kimoto S. Psychiatric adverse reaction to COVID-19 vaccine booster presenting as first-episode acute mania with psychotic features: A case report. Psychiatry Res Case Rep. (2023) 2:100143. doi: 10.1016/j.psycr.2023.100143

32. Laxmi R, Grover S. Unmasking of schizophrenia following COVID vaccination. Indian J Psychiatry. (2023) 65:385–6. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_607_22

33. Yesilkaya UH, Sen M, Tasdemir BG. A novel adverse effect of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine: First episode of acute mania with psychotic features. Brain Behav Immun Health. (2021) 18:100363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100363

34. Borovina T, Popovic J, Mastelic T, Ercegovac MS, Kustura L, Uglesic B, et al. FIRST EPISODE OF PSYCHOSIS FOLLOWING THE COVID-19 VACCINATION - A CASE SERIES. Psychiatr Danub. (2022) 34:377–80. doi: 10.24869/psyd.

35. Mushtaq HA, Khedr A, Koritala T, Bartlett BN, Jain NK, Khan SA. A review of adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines. Infezioni Medicina. (2022) 30:1–10. doi: 10.53854/liim-1993

36. Gavi. The Vaccin Alliance. 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. There are four types of COVID-19 vaccines: here’s how they work | Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance . Available online at: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/there-are-four-types-covid-19-vaccines-heres-how-they-work?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAi6uvBhADEiwAWiyRdk30JbFb67yQf-9j-DhuCZ6KRxGarh4ibKgUQsfrnTvw2obkpOwO4hoCEpMQAvD_BwE.

37. Han X, Xu P, Ye Q. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccines: Types, thoughts, and application. J Clin Lab Anal. (2021) 35:e23937. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23937

38. World Health Organization. The different types of COVID-19 vaccines. Geneva, Switzerland: Who (2021).

39. Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, Cocohoba JM, Lin F, Olgin JE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2140364. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

40. Vassallo A, Shajahan S, Harris K, Hallam L, Hockham C, Womersley K, et al. Sex and gender in COVID-19 vaccine research: substantial evidence gaps remain. Front Glob Womens Health. (2021) 2:761511. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.761511

41. Jongsma HE, Turner C, Kirkbride JB, Jones PB. International incidence of psychotic disorders 2002–17: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2019) 4:e229–44. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30056-8

42. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-coV-2 vaccine. New Engl J Med. (2021) 384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

43. Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, Fireman B, Zerbo O, Hanson KE, et al. Surveillance for Adverse Events after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. (2021) 326:1390–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072

44. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Üstün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2007) 20:359–64. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

45. Ganesan S, Al Ketbi LMB, Al Kaabi N, Al Mansoori M, Al Maskari NN, Al Shamsi MS, et al. Vaccine side effects following COVID-19 vaccination among the residents of the UAE—An observational study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:876336. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.876336

46. Menni C, Klaser K, May A, Polidori L, Capdevila J, Louca P, et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2021) 21:939–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3

47. Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, et al. The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:868–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901

48. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management(2014). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555203/.

49. Crossley NA, Constante M, McGuire P, Power P. Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 196:434–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066217

50. Klugar M, Riad A, Mekhemar M, Conrad J, Buchbender M, Howaldt HP, et al. Side effects of mrna-based and viral vector-based covid-19 vaccines among german healthcare workers. Biol (Basel). (2021) 10:752. doi: 10.3390/biology10080752

51. Mikulic M. Number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered in the United States as of April 26, 2023, by vaccine manufacturer (2023). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1198516/covid-19-vaccinations-administered-us-by-company/.

52. Stewart C. COVID-19 vaccine doses distributed to the EEA in 2022, by manufacturer (2022). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1219343/covid19-vaccine-doses-distributed-in-europe-by-manufacturer/.

53. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). COVID19 SARS vaccinations: systemic allergic reactions to SARS-coV-2 vaccinations (SARS) (2023). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04761822?intr=COVID-19%20Vaccine&aggFilters=results:with&rank=2#contacts-and-locations.

54. Benedetti F, Aggio V, Pratesi ML, Greco G, Furlan R. Neuroinflammation in bipolar depression. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:71. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00071

55. Mahadevan J, Sundaresh A, Rajkumar RP, Muthuramalingam A, Menon V, Negi VS, et al. An exploratory study of immune markers in acute and transient psychosis. Asian J Psychiatr. (2017) 25:219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.11.010

56. Müller N, Weidinger E, Leitner B, Schwarz MJ. The role of inflammation in schizophrenia. Front Neurosci. (2015) 9:372. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00372

57. Kayser MS, Dalmau J. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, autoimmunity, and psychosis. Schizophr Res. (2016) 176:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.007

58. Guedes BF, Ribeiro AF, Pinto LF, Vidal JE, de Oliveira FG, Sztajnbok J, et al. Potential autoimmune encephalitis following yellow fever vaccination: A report of three cases. J Neuroimmunol. (2021) 355:577548. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577548

59. Hofmann C, Baur MO, Schroten H. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis after TdaP-IPV booster vaccination: Cause or coincidence? J Neurology. (2011) 258:500–1. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5757-3

60. Wang H. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and vaccination. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:193. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010193

61. Norhayati MN, Che Yusof R, Azman YM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 8:783982. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.783982

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, vaccination, new-onset psychosis, adverse effects

Citation: Lazareva M, Renemane L, Vrublevska J and Rancans E (2024) New-onset psychosis following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 15:1360338. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1360338

Received: 22 December 2023; Accepted: 29 March 2024;

Published: 12 April 2024.

Edited by:

Feten Fekih-Romdhane, Tunis El Manar University, TunisiaReviewed by:

Mostafa Meshref, Al-Azhar University, EgyptMary G. Hornick, Roosevelt University, United States

Arunas Germanavicius, Republican Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital, Lithuania

Daria Smirnova, Samara State Medical University, Russia

Copyright © 2024 Lazareva, Renemane, Vrublevska and Rancans. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marija Lazareva, ZHIubWFyaWphbGF6YXJldmFAZ21haWwuY29t

Marija Lazareva

Marija Lazareva Lubova Renemane

Lubova Renemane Jelena Vrublevska

Jelena Vrublevska Elmars Rancans

Elmars Rancans