- Spiritual Health Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Objective: Cancer can have negative effects on mental health. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients’ worldwide using meta-analysis.

Methods: The study population was cancer patients who had cancer at the time of the study. The outcome studied in this study was anxiety symptoms/disorders. PubMed and Scopus were searched based on the syntax of keywords, this search was limited to articles published in English until September 2021. For this meta-analysis, data on the prevalence of anxiety were first extracted for each of the eligible studies. The random-effects method was used for the pool of all studies. Subgroup analysis was performed based on sex, anxiety disorders, cancer site, and continents. Heterogeneity in the studies was also assessed.

Result: After evaluating and screening the studies, eighty-four studies were included in the meta-analysis. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients showed that this prevalence is 23% (I2 = 99.59) in the 95% confidence interval between 22-25%. This prevalence was 20% (I2 = 96.06%) in the 95% confidence interval between 15-24% in men and this prevalence is 31% (I2 = 99.72%) in the 95% confidence interval between 28-34% in women. The highest prevalence of anxiety was in patients with ovarian, breast, and lung cancers.

Discussion: It showed a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients, in addition to therapeutic interventions for cancer, the necessary interventions should be made on the anxiety of these patients. Methodological limitation was the heterogeneity between the studies included in the meta-analysis. Some types of cancer sites could not be studied because the number of studies was small or the site of cancer was not identified.

Introduction

Mental disorders are among the leading causes of disease burden in the world so that a global study in 2019 showed that one of the two debilitating mental disorders was anxiety disorders, which was classified among the top 25 disease burden factors in 2019 (1, 2). Anxiety disorders continue to be one of the most common mental disorders in the world (3). Accordingly, a study by the Global Burden of Disease shows that anxiety disorders are responsible for 26.68 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (4). Studies show that anxiety disorders are more common than other mental disorders such as mood disorders, substance abuse, and impulse control disorders (5, 6). An examination of the prevalence of anxiety disorders shows that the prevalence of these disorders varies in different countries (7). According to the report published by the World Health Organization, anxiety symptoms often begin in childhood and adolescence (8). Currently, studies have reported a prevalence of anxiety disorders of 7.3%, ranging from 4.8% to 10.9% (9, 10).

There are gender differences in the prevalence of anxiety so that women are more likely to be affected by anxiety compared to men (11). Lifetime Generalized anxiety disorder prevalence was 3.7%, 12-month prevalence was 1.8%, and 1-month prevalence was 0.8% (3). The prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder was higher in high income countries (5%) than low income countries (1.6%) (3). Some of factors associated with the risk of developing anxiety disorders, including high body mass index (12–14), diabetic (15–17), stroke (18, 19), and personality and social risk factors (20). Cancer is diseases associated with anxiety (21).

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in the world (22). A global study published in 2016 shows that cancer is responsible for 213 million DALYs and 8.9 million deaths (23, 24). Between 2006 and 2016, cancer cases increased by 28%, the lowest increase was in countries with high sociodemographic index (23). In general, lung cancer is the most common type of cancer between the sexes (25). The most common type of cancer among men is prostate cancer, while the most common type of cancer among women is breast cancer (23). It is estimated that the number of cancers will increase to 28.4 million by 2040, which shows a 47% increase compared to 2020 (26). A range of factors has been suggested to increase the risk of cancer, including diet (27–29), smoking and alcohol use (30–32), aging (33, 34), psychological factors (35–37). Considering the effect of cancer on the dimensions of mental health (38, 39), studies have investigated the prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients (40–42).

The 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients was reported to be 39.4%, the most common of which were anxiety disorders (15.8%), followed by mood disorders (12.5%) and somatoform disorders (9.5%) (43). Extensive systematic review and meta-analysis studies have examined the prevalence of mental disorders, especially anxiety disorders, in cancer patients (44–50). Although studies examining the prevalence of anxiety disorders in cancer patients have become widespread, and systematic review and meta-analysis studies have been conducted in this area, several points required a new global study. First, fewer studies have been conducted on the prevalence of anxiety disorders, and most studies have studied a combination of mental disorders, and less distinction has been made between types of mental disorders. Second, in previous studies, each study often dealt with some types of cancer, and therefore different cancer sites have been less studied, and therefore a comprehensive view of different types of cancer is needed. Third, it is necessary to differentiate between men and women based on the types of cancer and anxiety disorders because types of cancer and anxiety disorders have different prevalence in men and women. Fourth, in studying the prevalence of anxiety disorders in cancer patients, a distinction should be made between cancer patients and cancer survivors. In this study, the focus was on cancer patients and not cancer survivors.

Based on what was stated, the aim of the present study was to investigate the global prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients and also to investigate the prevalence of anxiety based on sex, cancer site, type of anxiety disorder, and continents by conducting a meta-analysis.

Method

Protocol

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (51) guide was used for this study.

Information sources

Two databases, including PubMed and Scopus, were searched. This search was limited to articles published in English until September 2021. This search examined articles that were available online.

Search strategy

This search based on the syntax of keywords in Appendix 1; For example: The search strategy included terms such as ‘cancer’, ‘anxiety disorders’, ‘anxiety symptoms’, combined with Boolean operators.

Selection criteria

In the present study, a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was considered. The study population was cancer patients who had cancer at the time of the study. The outcome studied in this study was anxiety disorders or anxiety symptoms (Anxiety measurement included anxiety scales or anxiety diagnostic interviews). For the present study, cross-sectional, prospective and longitudinal studies (at baseline) were selected as the eligible study design. The following studies were not eligible: 1) Studies that have studied incidence rate. 2) Studies that have studied anxiety and depression together. 3) Studies on cancer survivors. 4) Studies with a sample size of fewer than 100 participants. 5) Review studies, studies with insufficient information to calculate the prevalence, and studies with the same database.

Data extraction

The extracted information included the characteristics of the authors, the year of the study, the demographic characteristics of the study population, as well as the methodological characteristics and results of each study. One researcher was responsible to data extraction.

Qualitative assessment

For quality evaluation, EPHPP tool (52, 53) was used, which in this study, three adjusted dimensions were used. These dimensions included selection bias, data collection method bias, and withdrawals/dropouts, and missing bias.

Meta-analysis

For this meta-analysis, data on the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders were first extracted for each of the eligible studies. After extracting the data for each study, some of the studies had several effect sizes, in which the average effect size was calculated. In some studies that used several anxiety measurement tools, one tool was selected. The random effects method was used for the pool of all studies in the form of meta-analysis. Subgroup analysis was performed based on sex, anxiety disorders, cancer site, and continents. Also, in the end, the degree of heterogeneity in the studies was examined using I2 and χ2 (54, 55). Data analysis in this study was using Stata-14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Selected studies

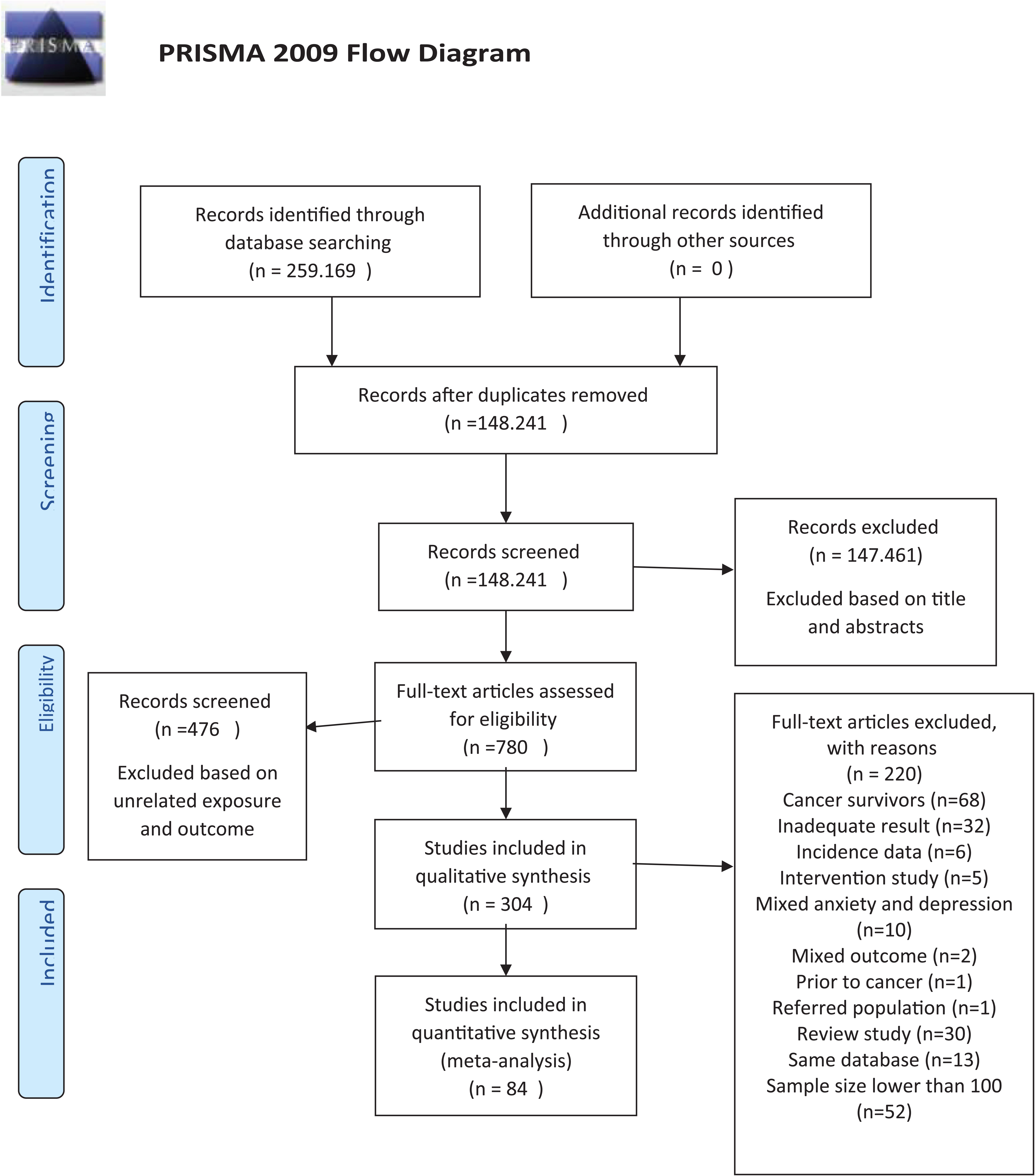

Figure 1 shows the selection and screening steps for articles. After screening, 84 eligible articles (43, 56–139) were included in the current meta-analysis (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of included studies. From: Moher et al. (150). For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

Quality of studies

Examination of the results in selective bias showed that except for 2 studies that had a high bias, the rest of the studies had a low and moderate bias. All studies had a low bias in the data collection method. Except for 1 study that had a high bias, the rest of the studies had a low and moderate bias in withdrawals/dropouts and missing.

Prevalence of anxiety

Prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients showed that this prevalence is 23% in the confidence interval between 22-25% (I2 = 99.59%). This finding shows that approximately one in four cancer patients was anxious.

Prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 20% in the confidence interval between 15-24% (I2 = 96.06%) in men. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 31% in the confidence interval between 28-34% (I2 = 99.72%) in women (Figure 2).

Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 7% in the confidence interval between 5-8% (I2 = 95.27%). Prevalence of panic disorder in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 3% in the confidence interval between 2-4% (I2 = 90.43%). Prevalence of PTSD in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 12% in the confidence interval between 8-16% (I2 = 98.91%). Prevalence of specific phobia in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 4% in the confidence interval between 0-7% (I2 = 0%). The prevalence of social phobia in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 2% in the confidence interval between 0-4% (I2 = 90.92%). Prevalence of OCD in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 0% in the confidence interval between 0-1% (I2 = 0%). The prevalence of agoraphobia in cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 2% in the confidence interval between 0-3% (I2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders was in ovarian cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 43% in the confidence interval between 31-56% (I2 = 93.30%). Lowest prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders was in colorectal cancer patients showed that this prevalence was 1% in the confidence interval between 1-1% (I2 = 0%) (Table 3).

Highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients was 38% in the confidence interval between 24-52% (I2 = 99.69%) in Asia. Lowest prevalence of anxiety in cancer patients was 12% in the confidence interval between 8-15% (I2 = 99.55%) in America (Figure 3).

Heterogeneity

To check the heterogeneity of the studies, the I2 was used, which showed that it was equal to 99.59 and was high (54). Also, this index was studied at the level of subgroups, but no significant difference was found. χ2 as the second test to check heterogeneity was also equal to 20230.12 (d.f 83; p <0.001).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the global prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients who had cancer at the time of the study. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients showed that 23% of patients had anxiety, in other words, it can be said that about one in four cancer patients had anxiety symptoms/disorders. This finding indicates a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients. However, studies in the general population show that the prevalence of anxiety is lower (140). Studies in other countries have also shown that the prevalence of anxiety in the general population is lower (10, 141). Therefore, the findings of the present study highlight the fact that patients with cancer have a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders, just as similar studies in cancer patients show a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in this population (142, 143). Experiencing anxiety symptoms/disorders after being diagnosed with cancer can be a common process and reaction that a person experiences (144). Cancer, on the other hand, can be considered a traumatic event, and as stated in the etiology of anxiety symptoms/disorders, stressful events can lead to anxiety (145).

Another finding from the current study was that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in men with cancer was 20%, while the prevalence was 31% for women. This finding clearly shows that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in women with cancer is almost one-third higher than men with cancer. In this regard, studies have shown that in the general population, the prevalence of anxiety in women is higher than men, accordingly (146), the lifetime prevalence of anxiety was 30.5% for women and 19.2% for men (147). The same finding has been shown in various types of anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, GAD, PTSD, OCD), ie higher prevalence of various types of anxiety disorders in women than men (147–149). Another finding from the current study showed that the highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders among cancers is in ovarian cancer (43%), followed by breast cancer (27%) and lung cancer (26%). Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders varies according to the cancer site (48, 143, 150). The most common type of anxiety disorder in cancer patients was post-traumatic stress disorder (12%), followed by generalized anxiety disorder (7%).

Limitations

One strength of this study was that it provided a comprehensive meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety based on different types of cancer sites. The second strength was that analyzes were based on a variety of anxiety symptoms/disorders and sex. One methodological limitation was the heterogeneity between the studies included in the meta-analysis, and this could be due to different sources, especially since different tools were used to measure anxiety. Some types of cancer sites could not be studied because the number of studies was small or the site of cancer was not identified. The study of prevalence points (4-weeks, 6-months, 12-months, and lifetime) was not possible in the present study and future studies could be performed in this area. Because the studies did not present these distinctions in the results.

Clinical implications

Considering the role that physical diseases play in mental symptoms and disorders, it is necessary to pay more attention to the appropriateness of psychological interventions for different groups of physical patients in the protocols related to the promotion of mental health as well as therapeutic interventions. After facing a physical disease, one person can suffer from a range of symptoms or mental disorders. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to treatment based on each person. Therefore, it is necessary to develop diagnostic, therapeutic and educational protocols based on cancer and symptoms/anxiety disorders.

Conclusion

The present study showed that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients is very high and this issue can impair their level of health and also affect the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Therefore, in addition to conventional interventions for cancer treatment, it is necessary to make psychological interventions to improve the mental health of cancer patients. It is also necessary to note that each person has unique characteristics that can affect health, healthy and unhealthy behaviors. Therefore, in interventions related to prevention and treatment, it is always necessary to pay special attention to the issue of personal characteristics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1422540/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

2. Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, Ashbaugh C, Erskine HE, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9(2):137–50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

3. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:465–75. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0056

4. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

5. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Jama. (2004) 291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

6. Kessler RC, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Wittchen HU. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Curr topics Behav neurosciences. (2010) 2:21–35.

7. Stein DJ, Scott KM, de Jonge P, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: from surveys to nosology and back. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2017) 19:127–36. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/dstein

8. WHO. Anxiety disorders. (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anxiety-disorders

9. Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Blore J, et al. The regional distribution of anxiety disorders: implications for the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2010. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2014) 23:422–38. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1444

10. Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. psychol Med May. (2013) 43:897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X

11. Javaid SF, Hashim IJ, Hashim MJ, Stip E, Samad MA, Ahbabi AA. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: global burden and sociodemographic associations. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. (2023) 30:44. doi: 10.1186/s43045-023-00315-3

12. Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. neuropsychiatrie. (2019) 33:72–89. doi: 10.1007/s40211-019-0302-9

13. Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. (2010) 34:407–19. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.252

14. Jebeile H, Gow ML, Baur LA, Garnett SP, Paxton SJ, Lister NB. Association of pediatric obesity treatment, including a dietary component, with change in depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics. (2019) 173:e192841–e192841. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2841

15. Smith KJ, Béland M, Clyde M, Gariépy G, Pagé V, Badawi G, et al. Association of diabetes with anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J psychosomatic Res. (2013) 74:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.11.013

16. Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Diabetes and anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2019) 91217419837407. doi: 10.1177/0091217419837407

17. Buchberger B, Huppertz H, Krabbe L, Lux B, Mattivi JT, Siafarikas A. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2016) 70:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.019

18. Burton CAC, Murray J, Holmes J, Astin F, Greenwood D, Knapp P. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. (2013) 8:545–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00906.x

19. Knapp P, Dunn-Roberts A, Sahib N, Cook L, Astin F, Kontou E, et al. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. (2020) 15:244–55. doi: 10.1177/1747493019896958

20. Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: A review. J Affect Disord. (2008) 106:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.005

21. Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF, Que JY, Liu JJ, Lappin JM, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry 2020/07/01. (2020) 25:1487–99. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x

22. Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, et al. The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. (2015) 1:505–27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735

23. Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdel-Rahman O, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. (2018) 4:1553–68. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2706

24. Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet (London England). (2017) 390:1151–210.

25. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

26. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

27. Gold EB, Gordis L, Diener MD, Seltser R, Boitnott JK, Bynum TE, et al. Diet and other risk factors for cancer of the pancreas. Cancer. (1985) 55:460–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850115)55:2<460::AID-CNCR2820550229>3.0.CO;2-V

28. Makarem N, Chandran U, Bandera EV, Parekh N. Dietary fat in breast cancer survival. Annu Rev Nutr. (2013) 33:319–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-112912-095300

29. McKenzie F, Ellison-Loschmann L, Jeffreys M, Firestone R, Pearce N, Romieu I. Cigarette smoking and risk of breast cancer in a New Zealand multi-ethnic case-control study. PloS One. (2013) 8:e63132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063132

30. Garrote LF, Herrero R, Reyes RMO, Vaccarella S, Anta JL, Ferbeye L, et al. Risk factors for cancer of the oral cavity and oro-pharynx in Cuba. Br J Cancer. (2001) 85:46–54. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1825

31. Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, Rohan T, Calle EE, Heath CW Jr, et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer–collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. (2002) 87:1234–45.

32. Jung S, Wang M, Anderson K, Baglietto L, Bergkvist L, Bernstein L, et al. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk by estrogen receptor status: in a pooled analysis of 20 studies. Int J Epidemiol. (2016) 45:916–28. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv156

33. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: Cancer J Clin. (2017) 67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387

34. Sun YS, Zhao Z, Yang ZN, Xu F, Lu HJ, Zhu ZY, et al. Risk factors and preventions of breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. (2017) 13:1387–97. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.21635

35. Eysenck HJ, Grossarth-Maticek R, Everitt B. Personality, stress, smoking, and genetic predisposition as synergistic risk factors for cancer and coronary heart disease. Integr Physiol Behav Science. (1991) 26:309–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02691067

36. Garssen B. Psychological factors and cancer development: evidence after 30 years of research. Clin Psychol review. (2004) 24:315–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.002

37. Levenson JL, Bemis C. The role of psychological factors in cancer onset and progression. Psychosomatics. (1991) 32:124–32. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72083-5

38. Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Cancer diagnosis and suicide mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Suicide Res. (2020) 24:S94–S112. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1596182

39. Krebber A, Buffart L, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology. (2014) 23:121–30. doi: 10.1002/pon.v23.2

40. Walker ZJ, Xue S, Jones MP, Ravindran AV. Depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders in patients with cancer in low- and lower-middle–income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JCO Global Oncol. (2021) 7:1233–50. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00056

41. Singer S, Das-Munshi J, Brähler E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care–a meta-analysis. Ann oncology: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. (2010) 21:925–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp515

42. Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S. Anxiety and depression prevalence in digestive cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. (2023) 13(e2):e235-43. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003275

43. Kuhnt S, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Keller M, Schulz H, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients. Psychother Psychosomatics. (2016) 85:289–96. doi: 10.1159/000446991

44. Singer S, Das-Munshi J, Brähler E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care—a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. (2010) 21:925–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp515

45. Vehling S, Koch U, Ladehoff N, Schön G, Wegscheider K, Heckl U, et al. Prevalence of affective and anxiety disorders in cancer: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie. (2012) 62:249–58. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309032

46. Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Keller M, Schulz H, et al. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:3540–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0086

47. Koutrouli N, Anagnostopoulos F, Potamianos G. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Women Health. (2012) 52:503–16. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.679337

48. Watts S, Prescott P, Mason J, McLeod N, Lewith G. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e007618. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007618

49. Swartzman S, Booth JN, Munro A, Sani F. Posttraumatic stress disorder after cancer diagnosis in adults: A meta-analysis. Depression anxiety. (2017) 34:327–39. doi: 10.1002/da.2017.34.issue-4

50. Peng Y-N, Huang M-L, Kao C-H. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients: a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:411. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030411

51. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

52. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract Feb. (2012) 18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

53. Thomas H. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. In: Effective public health practice project (2003). Available at: https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/

54. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.v21:11

55. Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Res ed.). (2007) 335:914–6.

56. Abuelgasim KA, Ahmed GY, Alqahtani JA, Alayed AM, Alaskar AS, Malik MA. Depression and anxiety in patients with hematological Malignancies, prevalence, and associated factors. Saudi Med J. (2016) 37:877–81. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.8.14597

57. Ahmed AE, Albalawi AN, Qureshey ET, Qureshey AT, Yenugadhati N, Al-Jahdali H, et al. Psychological symptoms in adult Saudi Arabian cancer patients: prevalence and association with self-rated oral health. (2018) 10:153. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S168139

58. Akyol M, Ulger E, Alacacioglu A, Kucukzeybek Y, Yildiz Y, Bayoglu V, et al. Sexual satisfaction, anxiety, depression and quality of life among Turkish colorectal cancer patients [Izmir Oncology Group (IZOG) study. (2015) 45(7):657–64. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyv051

59. Anuk D, Özkan M, Kizir A, Özkan S. The characteristics and risk factors for common psychiatric disorders in patients with cancer seeking help for mental health. (2019) 19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2251-z

60. Bergerot CD, Mitchell H-R, Ashing KT, Kim Y. A prospective study of changes in anxiety, depression, and problems in living during chemotherapy treatments: effects of age and gender. (2017) 25(6):1897–904. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3596-9

61. Blázquez MH, Cruzado JA. A longitudinal study on anxiety, depressive and adjustment disorder, suicide ideation and symptoms of emotional distress in patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy. (2016) 87:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.05.010

62. Borstelmann NA, Rosenberg SM, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, Schapira L, et al. Partner support and anxiety in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. (2015) 24(12):1679–85. doi: 10.1002/pon.v24.12

63. Cardoso G, Graca J, Klut C, Trancas B, Papoila A. Depression and anxiety symptoms following cancer diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. JP health Med. (2016) 21:562–70. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1125006

64. Chambers SK, Baade P, Youl P, Aitken J, Occhipinti S, Vinod S, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in lung cancer: the role of health-related stigma, illness appraisals and social constraints. Psychooncology. (2015) 24(11):1569–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.3829

65. Champagne A-L, Brunault P, Huguet G, Suzanne I, Senon JL, Body G, et al. Personality disorders, but not cancer severity or treatment type, are risk factors for later generalised anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder in non metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 236:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.12.032

66. Civilotti C, Botto R, Maran DA, Leonardis BD, Bianciotto B, Stanizzo MR. Anxiety and depression in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer and waiting for surgery: prevalence and associations with socio-demographic variables. (2021) 57(5):454. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050454

67. Costa-Requena G, Gil F. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in cancer: psychometric analysis of the Spanish Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian version. (2010) 19(5):500–7.

68. Coyne JC, Palmer SC, Shapiro PJ, Thompson R, DeMichele A. Distress, psychiatric morbidity, and prescriptions for psychotropic medication in a breast cancer waiting room sample. (2004) 26(2):121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.012

69. Dastan NB, Buzlu S. Depression and anxiety levels in early stage Turkish breast cancer patients and related factors. (2011) 12(1):137–41.

70. Dinkel A, Kremsreiter K, Marten-Mittag B, Lahmann C. Comorbidity of fear of progression and anxiety disorders in cancer patients. (2014) 36(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.08.006

71. Ene KW, Nordberg G, Johansson FG, Sjöström B. Pain, psychological distress and health-related quality of life at baseline and 3 months after radical prostatectomy. (2006) 5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-5-8

72. Geue K, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Schulz H, Weis J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial distress in German adolescent and young adult cancer patients (AYA). Psychooncology. (2018) 27(7):1802–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.v27.7

73. Goncalves V, Jayson G, Tarrier N. A longitudinal investigation of psychological morbidity in patients with ovarian cancer. (2008) 99(11):1794–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604770

74. Grassi L, Sabato S, Rossi E, Marmai L, Biancosino B. Affective syndromes and their screening in cancer patients with early and stable disease: Italian ICD-10 data and performance of the Distress Thermometer from the Southern European Psycho-Oncology Study (SEPOS). (2009) 114(1-3):193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.016

75. Hall A, A’hern R, Fallowfield L. Are we using appropriate self-report questionnaires for detecting anxiety and depression in women with early breast cancer? (1999) 35(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00308-6

76. Hassan MR, Shah SA, Ghazi HF, Mujar NMM, Samsuri MF, Baharom N. Anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients in an urban setting in Malaysia. (2015) 16(9):4031–5. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.9.4031

77. Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Riggs RL, et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. (2006) 107(12):2924–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v107:12

78. Hervouet S, Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H, Laverdière J, Vigneault E, et al. Psychological functioning associated with prostate cancer: cross-sectional comparison of patients treated with radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or surgery. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2005) 30(5):474–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.05.011

79. Hopwood P, Sumo G, Mills J, Haviland J, Bliss J. The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: results from the UK Standardisation of Radiotherapy Trials (START). (2010) 19(2):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.11.007

80. Jimenez-Fonseca P, Calderón C, Hernández R, Ramón Y, Cajal T, Mut M, et al. Factors associated with anxiety and depression in cancer patients prior to initiating adjuvant therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. (2018) 20(11):1408–15. doi: 10.1007/s12094-018-1873-9

81. Kang JI, Sung NY, Park SJ, Lee CG, Lee BO. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among women with breast cancer in South Korea: analysis of national registry data. (2014) 23(1):35–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.v23.1

82. Karakoyun-Celik O, Gorken I, Sahin S, Orcin E, Alanyali H, Kinay M. Depression and anxiety levels in woman under follow-up for breast cancer: relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Med Oncol. (2010) 27:108–13. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9181-4

83. Kazlauskiene J, Bulotiene G. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among Lithuanian breast cancer patients and its risk factors. J Psychosom Res. (2020) 131:109939. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109939

84. Keller M, Sommerfeldt S, Fischer C, Knight L, Riesbeck M, Löwe B, et al. Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: a multi-method approach. Ann Oncol. (2004) 15:1243–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh318

85. Kim SH, Seong DH, Yoon SM, Choi YD, Choi E, Song H. Predictors of health-related quality of life in Korean prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2017) 30:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.08.009

86. Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, Clarke DM, Bloch S, Smith GC. Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2004) 38:320–6. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01358.x

87. Köhler N, Friedrich M, Gansera L, Holze S, Thiel R, Roth S, et al. Psychological distress and adjustment to disease in patients before and after radical prostatectomy. Results of a prospective multi-centre study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2014) 23:795–802. doi: 10.1111/ecc.2014.23.issue-6

88. Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Zhang B, Trice ED, Kissane DW, Breitbart W, et al. Do rates of mental disorders and existential distress among advanced stage cancer patients increase as death approaches? Psychooncology. (2009) 18:50–61. doi: 10.1002/pon.1371

89. Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. (2012) 141:343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025

90. Liu B, Wu X, Shi L, Li H, Wu D, Lai X, et al. Correlations of social isolation and anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with breast cancer of Heilongjiang province in China: The mediating role of social support. Nurs Open. (2021) 8:1981–9. doi: 10.1002/nop2.v8.4

91. Liu CL, Liu L, Zhang Y, Dai XZ, Wu H. Prevalence and its associated psychological variables of symptoms of depression and anxiety among ovarian cancer patients in China: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2017) 15:161. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0738-1

92. Love AW, Kissane DW, Bloch S, Clarke D. Diagnostic efficiency of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in women with early stage breast cancer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2002) 36:246–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01014.x

93. Lueboonthavatchai P. Prevalence and psychosocial factors of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. J Med Assoc Thai. (2007) 90:2164–74.

94. Mallet J, Huillard O, Goldwasser F, Dubertret C, Le Strat Y. Mental disorders associated with recent cancer diagnosis: Results from a nationally representative survey. Eur J Cancer. (2018) 105:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.038

95. Marco DJT, White VM. The impact of cancer type, treatment, and distress on health-related quality of life: cross-sectional findings from a study of Australian cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27:3421–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4625-z

96. Mehnert A, Lehmann C, Graefen M, Huland H, Koch U. Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life and its association with social support in ambulatory prostate cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2010) 19:736–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01117.x

97. Mohamad Rodi I, Foong Ming M, Abdul Razack AH, ZAINUDDIN Z,MD, Zainal NZ. Anxiety status and its relationship with general health related quality of life among prostate cancer patients in two university hospitals in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. (2013) 42(3):240.

98. Naser AY, Hameed AN, Mustafa N, Alwafi H, Dahmash EZ, Alyami HS, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:585534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.585534

99. Nelson CJ, Balk EM, Roth AJ. Distress, anxiety, depression, and emotional well-being in African-American men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. Oct. (2010) 19:1052–60.

100. Ng CG, Dijkstra E, Smeets H, Boks MP, de Wit NJ. Psychiatric comorbidity among terminally ill patients in general practice in the Netherlands: a comparison between patients with cancer and heart failure. Br J Gen Pract Jan. (2013) 63:e63–68.

101. Ng GC, Mohamed S, Sulaiman AH, Zainal NZ. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the association with religiosity and religious coping. J Relig Health Apr. (2017) 56:575–90. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0267-y

102. Nikbakhsh N, Moudi S, Abbasian S, Khafri S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients. Caspian J Internal Med Summer. (2014) 5:167–70.

103. Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Hopper JL. Age-specific norms and determinants of anxiety and depression in 731 women with breast cancer recruited through a population-based cancer registry. Eur J Cancer. Apr. (2003) 39:755–62. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00814-6

104. Palmer SC, Taggi A, Demichele A, Coyne JC. Is screening effective in detecting untreated psychiatric disorders among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients? Cancer. (2012) 118:2735–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v118.10

105. Perry LM, Hoerger M, Silberstein J, Sartor O, Duberstein P. Understanding the distressed prostate cancer patient: Role of personality. Psycho-oncology. (2018) 27:810–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.v27.3

106. Price MA, Butow PN, Costa DSJ, King MT, Aldridge LJ, Fardell JE, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression in women with invasive ovarian cancer and their caregivers. Med J Aust. (2010) 193:S52–57. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03929.x

107. Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, Carreras E, Rovira M, Cirera E, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. (2002) 20:1907–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.101

108. Priscilla D, Hamidin A, Azhar MZ, Noorjan KO, Salmiah MS, Bahariah K. Assessment of depression and anxiety in haematological cancer patients and their relationship with quality of life. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. (2011) 21:108–14.

109. Puigpinós-Riera R, Graells-Sans A, Serral G, Continente X, Bargalló X, Domènech M, et al. Anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer: Social and clinical determinants and influence of the social network and social support (DAMA cohort). Cancer Epidemiol. (2018) 55:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.06.002

110. Punnen S, Cowan JE, Dunn LB, Shumay DM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. A longitudinal study of anxiety, depression and distress as predictors of sexual and urinary quality of life in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. (2013) 112:E67–75. doi: 10.1111/bju.2013.112.issue-2

111. Rasic DT, Belik SL, Bolton JM, Chochinov HM, Sareen J. Cancer, mental disorders, suicidal ideation and attempts in a large community sample. Psychooncology. (2008) 17:660–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.v17:7

112. Roth A, Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Warshowski A, O'Shea N, Scher H, et al. Assessing anxiety in men with prostate cancer: further data on the reliability and validity of the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer (MAX-PC). Psychosomatics. (2006) 47:340–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.4.340

113. Saboonchi F, Petersson LM, Wennman-Larsen A, Alexanderson K, Brännström R, Vaez M. Changes in caseness of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients during the first year following surgery: patterns of transiency and severity of the distress response. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2014) 18:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.06.007

114. Pedersini R, di Mauro P, Amoroso V, Castronovo V, Zamparini M, Monteverdi S, et al. Sleep disturbances and restless legs syndrome in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer given adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Breast. (2022) 66:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.10.006

115. Sánchez Sánchez E, González Baena AC, González Cáliz C, Caballero Paredes F, Moyano Calvo JL, Castiñeiras Fernández J. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in prostate cancer patients and their spouses: an unaddressed reality. Prostate cancer. (2020) 2020:4393175–4393175. doi: 10.1155/2020/4393175

116. Schellekens MPJ, van den Hurk DGM, Prins JB, Molema J, van der Drift MA, Speckens AEM. The suitability of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Distress Thermometer and other instruments to screen for psychiatric disorders in both lung cancer patients and their partners. J Affect Disord. (2016) 203:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.044

117. Singer S, Danker H, Dietz A, et al. Screening for mental disorders in laryngeal cancer patients: a comparison of 6 methods. Psychooncology. (2008) 17:280–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.v17:3

118. Smith AB, Wright EP, Rush R, Stark DP, Velikova G, Selby PJ. Rasch analysis of the dimensional structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psychooncology. (2006) 15:817–27. doi: 10.1002/pon.v15:9

119. So WK, Marsh G, Ling WM, Leung FY, Lo JC, Yeung M, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2010) 14:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.07.005

120. Spencer R, Nilsson M, Wright A, Pirl W, Prigerson H. Anxiety disorders in advanced cancer patients: correlates and predictors of end-of-life outcomes. Cancer. (2010) 116:1810–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v116:7

121. Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, Velikova G, House A, Selby P. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol. (2002) 20:3137–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.549

122. Storey DJ, McLaren DB, Atkinson MA, Butcher I, Frew LC, Smyth JF, et al. Clinically relevant fatigue in men with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer on long-term androgen deprivation therapy. Ann Oncol. (2012) 23:1542–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr447

123. Tan X-F, Xia F. Long-term fatigue state in postoperative patients with breast cancer. Chin J Cancer Res = Chung-kuo yen cheng yen chiu. (2014) 26:12–6.

124. Tavoli A, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Roshan R, Tavoli Z, Omidvari S. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: does knowledge of cancer diagnosis matter? BMC Gastroenterology. (2007) 7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-28

125. Unseld M, Krammer K, Lubowitzki S, Jachs M, Baumann L, Vyssoki B, et al. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorders in 1017 cancer patients and correlation with anxiety, depression, and distress. Psychooncology. (2019) 28:2382–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.v28.12

126. van Montfort E, de Vries J, Arts R, Aerts JG, Kloover JS, Traa MJ. The relation between psychological profiles and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:1359–67. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04923-w

127. Vehling S, Kissane DW, Lo C, Glaesmer H, Hartung TJ, Rodin G, et al. The association of demoralization with mental disorders and suicidal ideation in patients with cancer. Cancer. (2017) 123:3394–401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v123.17

128. Vin-Raviv N, Akinyemiju TF, Galea S, Bovbjerg DH. Depression and anxiety disorders among hospitalized women with breast cancer. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0129169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129169

129. Vin-Raviv N, Hillyer GC, Hershman DL, Galea S, Leoce N, Bovbjerg DH, et al. Racial disparities in posttraumatic stress after diagnosis of localized breast cancer: the BQUAL study. J Natl Cancer Institute. (2013) 105:563–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt024

130. Vodermaier A, Linden W, MacKenzie R, Greig D, Marshall C. Disease stage predicts post-diagnosis anxiety and depression only in some types of cancer. Br J Cancer. (2011) 105:1814–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.503

131. Watts S, Leydon G, Eyles C, Moore CM, Richardson A, Birch B, et al. A quantitative analysis of the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in patients with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e006674. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006674

132. Wen Q, Shao Z, Zhang P, Zhu T, Li D, Wang S. Mental distress, quality of life and social support in recurrent ovarian cancer patients during active chemotherapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2017) 216:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.07.004

133. Wiechno PJ, Sadowska M, Kalinowski T, Michalski W, Demkow T. Does pharmacological castration as adjuvant therapy for prostate cancer after radiotherapy affect anxiety and depression levels, cognitive functions and quality of life? Psychooncology. (2013) 22:346–51. doi: 10.1002/pon.v22.2

134. Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, Skirko MG, Allard P, Chary S, Gagnon PR, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2007) 33:118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.016

135. Yang H, Brand JS, Fang F, Chiesa F, Johansson AL, Hall P, et al. Time-dependent risk of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders in patients with invasive and in situ breast cancer. Int J Cancer. (2017) 140:841–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.v140.4

136. Yang YL, Liu L, Li MY, Shi M, Wang L. Psychological disorders and psychosocial resources of patients with newly diagnosed bladder and kidney cancer: A cross-sectional study. PloS One. (2016) 11:e0155607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155607

137. Yang YL, Liu L, Wang XX, Wang Y, Wang L. Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. PloS One. (2014) 9:e94804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094804

138. Yektatalab S, Ghanbari E. The relationship between anxiety and self-esteem in women suffering from breast cancer. J mid-life Health. (2020) 11:126–32. doi: 10.4103/jmh.JMH_140_18

139. Zhang AY, Cooper GS. Recognition of depression and anxiety among elderly colorectal cancer patients. Nurs Res practice. (2010) 2010:693961–1. doi: 10.1155/2010/693961

140. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2015) 17:327–35. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/bbandelow

141. Zuberi A, Waqas A, Naveed S, Hossain MM, Rahman A, Saeed K, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in the WHO eastern mediterranean region: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:1035. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.665019

142. Brunckhorst O, Hashemi S, Martin A, George G, Van Hemelrijck M, Dasgupta P, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer prostatic diseases. (2021) 24:281–9. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-00286-0

143. Hashemi SM, Rafiemanesh H, Aghamohammadi T, Badakhsh M, Amirshahi M, Sari M, et al. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer (Tokyo Japan). (2020) 27:166–78. doi: 10.1007/s12282-019-01031-9

144. Bates GE, Mostel JL, Hesdorffer M. Cancer-related anxiety. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:1007–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0254

145. Miloyan B, Joseph Bienvenu O, Brilot B, Eaton WW. Adverse life events and the onset of anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 259:488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.027

146. McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. (2011) 45:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

147. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1994) 51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002

148. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1995) 52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

149. Breslau N CH, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Gender differences in major depression: The role of anxiety. In: Frank E, editor. Gender And Its Effects On Psychopathology. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc, Arlington, VA (2000). p. 131–50.

150. Yan X, Chen X, Li M, Zhang P. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with lung cancer: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Manag Res. (2019) 11:4347–56. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S202119

151. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

152. Isa MR, Moy FM, Abdul Razack AH, Md Zainuddin Z, Zainal NZ. Anxiety status and its relationship with general health related quality of life among prostate cancer patients in two university hospitals in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Iran J Public Health. (2013) 42(3):240–8.

Keywords: anxiety, cancer patients, meta-analysis, systematic review, anxiety symptoms

Citation: Amiri S (2024) The prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 15:1422540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1422540

Received: 30 April 2024; Accepted: 15 October 2024;

Published: 15 November 2024.

Edited by:

Valeria Sebri, European Institute of Oncology (IEO), ItalyReviewed by:

Mohsen Khosravi, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, IranJerry Lorren Dominic, Jackson Memorial Hospital, United States

Copyright © 2024 Amiri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sohrab Amiri, YW1pcnlzb2hyYWJAeWFob28uY29t

Sohrab Amiri

Sohrab Amiri