Abstract

Background:

The parent–infant relationship is important for healthy infant development. Parent–infant assessments can aid clinicians in identifying any difficulties within the parent–infant relationship. Meaningful, valid, and reliable clinician-rated measures assist these assessments and provide diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment indications. Thus, this review aimed to (a) provide a comprehensive overview of existing clinician-rated measures and their clinical utility for the assessment of aspects of the parent–infant relationship and (b) evaluate their methodological qualities and psychometric properties.

Methods:

A systematic search of five databases was undertaken in two stages. In Stage 1, relevant clinician-rated parent–infant assessment measures, applicable from birth until 2 years postpartum were identified. In Stage 2, relevant studies describing the development and/or validation of those measures were first identified and then reviewed. Eligible studies from Stage 2 were quality assessed in terms of their methodological quality and risk of bias; a quality appraisal of each measure’s psychometric properties and an overall grading of the quality of evidence were also undertaken. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments methodology was used.

Results:

Forty-one measures were eligible for inclusion at Stage 1, but relevant studies reporting on the development and/or validation of the parent–infant assessments were identified for 25 clinician-rated measures. Thirty-one studies reporting on those 25 measures that met inclusion criteria were synthesised at Stage 2. Most measures were rated as “low” or “very low” overall quality according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach. The most promising evidence was identified for the Mother–Infant/Toddler Feeding Scale, Tuned-In Parenting Scale, and Coding Interactive Behaviour Instrument.

Conclusions:

There was a notable diversity of measures that can be used to assess various aspects of the parent–infant relationship, including attunement, attachment, interaction quality, sensitivity, responsivity, and reciprocity. The quality of methodological and psychometric evidence across the reviewed measures was low, with 76% of measures having only one study supporting the measure’s development and/or validation. Thus, further research is needed to review the psychometric properties and suitability as assessment measures.

Introduction

Disruptions to early childhood, for example, through trauma or illness, can have a long-term impact on infant mental and physical health, developmental trajectory, and even socioeconomic standing later in life (1, 2). During the first critical year in a child’s life, the infant brain undergoes rapid development and is particularly sensitive to experiences, both positive and negative (3). The parent–infant relationship has been identified as an early life experience, crucial for the infant’s development (4, 5). As infants can recognise and respond to parental speech and cues within the first three months of life (6), parental behaviours can significantly and profoundly influence infant wellbeing (7). Inappropriate parent–infant interactions and traumatic experiences in the early period of a child’s life can impact the developing brain (8, 9) and lead to increased cortisol levels, which may later increase the risk of hyperactivity, anxiety, and attachment difficulties (10, 11). Additionally, the quality of the parent–infant relationship is known to have a significant impact on the social and emotional development of the infant as well as on cognitive and academic development (5, 12, 13). Brief periods of poorly attuned parent–infant relationships are common; however, prolonged periods of inconsistent parenting and disorganisation within the dyad can lead to maladaptive outcomes for infants (4, 14).

The impact of perinatal mental health difficulties (PMHDs) on the parent–infant relationship has been acknowledged in the literature (15–17). PMHDs occur during pregnancy or in the first year following birth, affecting up to 20% of new and expectant mothers (18). PMHDs cover a wide range of conditions, including postpartum depression, anxiety and psychosis (19). If left untreated, PMHDs can have both short- and long-term impacts on the parent, child and wider family, including transgenerational effects (20). Perinatal mental health (PMH) services (including parent–infant services) can help to ameliorate these effects. PMH services assess the parent–infant relationship and identify negative and positive aspects of parent–infant interactions (21). The assessment of the parent–infant relationship and its associated aspects, such as attachment behaviours, sensitivity, responsivity, reciprocity, and attunement, can assist clinicians in providing assessment, guidance, and, importantly, interventions, with the aim of improving maternal sensitivity, the parent–child relationship and child behaviour (22). Measurement tools are also routinely used to monitor and evaluate treatment and service effectiveness. It is therefore of critical importance for clinicians to have access to meaningful, valid, and reliable measures to assess the parent–infant relationship.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists (23) recommends several parent report measures to assess the parent–infant relationship, namely, the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) (24) and the Mothers’ Object Relations Scale–short form (25) as well as clinician-rated measures, such as the Bethlem Mother–Infant Interaction Scale (26), the CARE-Index (27), the Parent–Infant Interaction Observation Scale (28), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development scale (NICHD) (29).

In a comprehensive review of 17 original parent report assessment measures and 13 modified versions, Wittkowski et al. (30) identified that the PBQ, both the original and modified versions, was found to have the strongest psychometric properties with the highest quality of evidence ratings received. Despite the potential drawbacks to using clinician-rated measures, several authors [e.g., (31–33)] have questioned the benefits of parent report measures over clinician-rated or observational measures, citing possible biases from the parents regarding their child’s perceived skills, behaviours, and interactions or their tendency to respond in a socially desirable way. Wittkowski et al. (30) also wondered if clinician-rated measures might not be used consistently across services, potentially due to a need for training to use the measures and any trainingcosts, as well as supervision and capacity issues.

At least three other reviews of clinician-rated measures assessing aspects of the parent–infant relationship exist. For example, in their systematic review of 17 measures, of the parent–infant interaction, Munson and Odom (34) provided good levels of detail regarding the validity and reliability of the identified assessment measures; however, they did not assess responsiveness or measurement error and, in terms of validity, they also did not assess the measures’ structural validity, thereby reducing the comprehensiveness of their results. They also drew information from non-peer reviewed information, such as books and manuals; thus, the impact of the results in this field of research may be reduced (30). Additionally, their review, which is now 28 years old, excluded measures that used behavioural coding systems, solely assessing measures which used rating scales.

To demonstrate the appropriateness of assessing behavioural and emotional problems during infancy, Bagner et al. (35) conducted a review of both parent report questionnaires (n = 7) and observational coding or clinician rated procedures (n = 4). Of the four observational coding measures they reviewed, the Functional Emotional Assessment Scale (36) and the Emotional Availability Scales (EAS) (37) are the most widely known ones. The authors concluded that the observational coding procedures provided more detailed and meaningful information regarding the infant (less than 12 months old) and caregiver than parent report measures. However, their review did not assess responsiveness, measurement error, or hypothesis testing for construct validity to determine the quality of the studies, potentially leading to errors in judgement when clincians or researchers attempt to determine the best measure to use (32).

Finally, in their comprehensive review of measures rated by a trained clinician, Lotzin et al. (32) focused on 24 existing measures with more than one journal article describing or evaluating each measure. They synthesised 104 articles published between 1975 and 2012, 60.5% of which had low methodological quality. Lotzin et al. (32) assigned lower quality ratings to authors not reporting enough detail about their study and/or using small sample sizes. Lotzin et al. (32) also concluded that further studies refining the existing tools were needed with regard to content validity and consequential validity. Although they were comprehensive and thorough in their evaluation of psychometric properties across their stipulated five validity domains of (1) content, (2) response process, (3) internal structure, (4) relation to other variables and (5) consequences of assessment, Lotzin et al. (32) appeared to follow their own idiosyncratic method of assessing a measure’s validity, rather than following standardised criteria.

Increasingly, systematic reviews of assessment measures (self-report and/or clinician-rated) have used the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) (38–41) tools. The COSMIN is an initiative of a team of researchers who have expertise in the development and evaluation of outcome measurement instruments. The COSMIN initiative aims to improve the selection of outcome measures within clinical practice and research (41) by developing specific standards and criteria for evaluating and reporting on the measurement properties of the outcome measures (42). For examples of reviews informed by the COSMIN criteria and guidelines, see Wittkowski et al. (43), Bentley, Hartley and Bucci (44) and Wittkowski et al. (30). These reviews did not assess clinician-rated measures.

Given the shortcomings of the abovementioned reviews by Wittkowski et al. (30), Munson and Odom (34), Bagner et al. (35) and Lotzin et al. (32), there is now a clear need for a systematic, transparent, comprehensive, COSMIN-informed review of relevant measures in this field. Thus, the aim of this systematic review was to assist practitioners and researchers in identifying the most suitable measures to use in their clinical practice or research by providing an overview (in Stage 1) and evaluation (Stage 2) of the current existing clinician-rated assessment measures of the parent–infant relationship, including its specific aspects such as attachment behaviours, sensitivity, responsivity, reciprocity, and attunement. The following questions were examined in this review:

-

What assessment measures did exist for clinicians to assess the parent–infant relationship in the perinatal period?

-

Which measures demonstrated the best clinical utility, methodological qualities, and psychometric properties?

Methods

This systematic review, registered with the PROSPERO database (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero; registration number CRD42024501229), was conducted in accordance with the COSMIN tools (38, 41, 42) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (45). The methodology, which was specifically developed and validated for use in reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) (38), can be adapted and used for other types of outcome measures, for example, those in which opinions on the parent–infant relationship are not self-reported but instead are evaluated by clinicians (clinician-reported outcome measures or ClinROMs) (40). The first author acted as the main reviewer but received support and supervision from the other two authors.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in two stages: 1) to identify which parent–infant assessments exist for clinicians to use and 2) to identify studies describing the development and/or validation of each identified measure. The following databases were searched for both stages: PsycINFO (Ovid), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE, Ovid), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE, Ovid), and Web of Science.

Stage 1 of the search involved designing a search strategy to identify and retrieve studies of relevance to the development and/or use of clinician-rated measures of the parent–infant relationship. As recommended by the COSMIN guidelines for systematic reviews (41), this initial search was first piloted and then, after further refinement with a university librarian, the final Stage 1 search was completed in November 2023. Searches using Ovid (MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsychINFO) were limited to abstracts, English language and “humans.” CINAHL and Web of Science did not offer these options of limits. Six search categories were developed, which were combined using the Boolean operator “AND.” The instruction “OR” was applied within each category and, when relevant, wildcard asterisks were used to capture related terms (Table 1). At Stage 1, all articles were screened based on abstract and title review and those mentioning parent–infant assessment measures were examined for full-text review. Each identified measure was assessed for eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1

| Database (and platform): PsycInfo (OVID); Medline (OVID), EMBASE (OVID); CINAHL plus (EBSCOhost); Web of Science (Clarivate) | |

|---|---|

| 1. | (Parent* or maternal or paternal or mother* or father* or caregiver* or guardian*) AND (Infant* or child* or newborn or baby or neonate or babie*) |

| 2. | (Parent–infant) OR (infant–parent) OR (mother–infant) OR (infant–mother) OR (father–infant) OR (infant–father) OR (caregiver–infant) OR (infant–caregiver) |

| 3. | Relations* OR interact* OR communicat* OR bond* OR attachment OR “nonverbal communicat*” OR dyadic behavio* OR “interpersonal relation*” OR “mother–child relation*” OR “father–child relation*” OR “parent–infant relation*” OR synchrony OR synchronicity OR “emotional availability” OR attitude* OR belief* OR responsiv* OR feel* |

| 4. | Perinat* OR antenat* OR prenat* OR puerper* OR postnat* OR postpart* OR peripartum |

| 5. | Assess* OR observation* OR behavio* OR measur* OR scale* OR tool* OR inventor* OR instrument* OR test* OR rat* OR behavio* cod* OR behavio* assessment* OR behavio* measure* OR rat* scale* OR cod* system* OR checklist* OR videotap* OR video* record* |

| 6. | Clinician* OR staff OR practitioner* OR observer* OR rater* OR professional* |

| 7. | 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 AND 5 AND 6 |

Search terms and limits at Stage 1.

Limits: Abstract, Humans and English language.

To ensure the reliability of this review process, an independent reviewer (E.W.) double screened 10% of randomly selected papers from Stage 1. Cohen’s kappa and the percentage of inter-rater agreement were calculated, with good agreement (κ = .80, p <.001; 98.20%) (46).

At Stage 2, any relevant measures identified in Stage 1 were searched for in the same databases to identify any studies describing each measure’s initial development and/or validation. This search was conducted in December 2023 and later updated in early 2024. The following terms were searched: “Relationship” OR “Interaction” OR “Dyad” OR “Bond” OR “Sensitivity” OR “Responsiveness” OR “Attachment” OR “Attunement” OR “Reflexivity” OR “Adjustment” OR “Behaviour” AND the measure’s name OR abbreviation. Studies identified in Stage 2 were reviewed based on title and abstract; studies were assessed for eligibility by examining their full text, and their reference lists were checked for additional studies.

Eligibility criteria of measures and studies

At Stage 1, measures were included if they were developed for clinicans to assess or rate the parent–infant relationship or a specific aspect of this relationship (e.g., attachment, reciprocity, attunement, bonding, parental sensitivity, and emotional regulation) (12). For the purpose of this review, we used the following definitions of the parent–infant relationship to help guide the identification of suitable measures: “Parent–infant relationships refer to the quality of the relationship between a baby and their parent or carer” [46, p. 2] and “the connection or bond created between the parent and infant through the exchange of behaviours and emotion communicated between both parties” [(47), p.3]. Thus, we included measures of interaction between the parent and their infant if it was a reciprocal exchange. The CARE-Index was also pre-determined to be included because its utility in assessing parent–infant interactions has been demonstrated in research into attachment behaviours (27, 48, 49). The CARE-Index has also been recognised in other systematic reviews of parent–infant assessment measures, including by Lotzin et al. (32) and the Royal College of Psychiatrists (23).

Measures were included only if they were applicable for use with an infant from birth up to the age of 2 years, which is defined as the perinatal period by the NHS Long Term Plan in the UK (50) and sometimes also referred to as the first 1,001 days (51). In the perinatal period, any difficulties within the parent–infant relationship should be identified as early as possible so that future interventions or treatment decisions can be made (52). Measures were excluded if they were designed to assess a related but different concept (e.g., “parenting style” or “attitudes to pregnancy”). Measures were also excluded if full-text studies could not be accessed or if they assessed the parent–infant relationship as part of a subscale in a longer inventory.

At Stage 2, studies were included if they 1) described the initial development and/or validation of an identified measure, 2) included data pertaining to an attempt to validate and/or to test the psychometric properties of the measure and this was stated in the aims of the study, and 3) were published in a peer reviewed journal in order to ensure consistently high-quality studies were used (53). Studies were excluded if they were not written in English and/or were reported only in theses, dissertations, or conference abstracts. We also excluded any measure for which we could not identify any studies describing the psychometric evaluation of that measure.

Quality assessment of the studies included after Stage 2

The COSMIN Risk of Bias Tool (40), an extended version of the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist (38), was used to assess the methodological quality of studies identified at Stage 2, and subsequently determine each study’s overall risk of bias. Figure 1 reflects the recommended 11-step procedure for conducting a systematic review on any type of outcome measure instrument outlined in the COSMIN Risk of Bias Tool user manual (40). The manual was developed to assess the quality of studies of all types of outcome measure instruments (including ClinROMs) and designed to be incorporated into the COSMIN methodology (40). It differs from the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist in that it includes boxes for assessing reliability and measurement error. Furthermore, Step 8 (“Evaluate interpretability and feasibility”) was removed from the Risk of Bias Tool because interpretability and feasibility do not refer to the quality of the ClinROM (40). Interpretability and feasibility were instead extracted and summarised within a descriptive characteristics table. In this table, we included ease of administration (with regard to home or laboratory observations and time required to complete observations), associated costs and interpretability of scores. Both the COSMIN Risk of Bias Tool (40) and the COSMIN criteria (41, 42) are based on the COSMIN taxonomy for measurement properties, and these criteria are generally agreed as gold standard when evaluating measures in the context of a systematic review ensuring standardisation across papers (39). The COSMIN guidelines recommend the following stages for assessing the quality of an outcome measure, outlined in Figure 1 as Parts A, B, and C.

Figure 1

Diagram of the 11 steps for conducting a systematic review on any type of outcome measure instrument.

Part A: quality appraisal for the methodological quality for each measurement property and risk of bias assessment across each study

The first steps in assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies were based on the Terwee et al. (42) COSMIN criteria and the Mokkink et al. (40) COSMIN Risk of Bias Tool. A COSMIN evaluation sheet (see Appendix A in Supplementary Materials) was adapted for this review to include comprehensibility (from the clinician’s point of view) because this was more applicable for clinician-rated measures (54). Content validity was assessed in terms of relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility using Terwee et al.’s (42) updated criteria. Each measurement property is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2

| Measurement property | Definition | Rating | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validity (the degree to which the clinician-reported outcome measure (ClinROM) measures the construct(s) it purports to measure) | |||

| Content validity (includes relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) | The degree to which the measure is an adequate reflection of the construct being measured. | + | Above 85% of the items of the measure are relevant AND are relevant for the target population AND are relevant for the context intended for use AND have appropriate response options OR have appropriate recall period AND include all key concepts AND together comprehensively reflect the construct intended to be measured. |

| ? | Not enough information for (+) OR potential biases identified OR the quality of the study is inadequate | ||

| - | Less than 85% of the items of the measure fulfil the above criteria | ||

| Structural validity | The degree to which the scores of an assessment measure can adequately reflect the dimensionality of the construct being measured. | + | Classical Test Theory (CTT) Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA): comparative fit index (CFI) or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) or comparable measure > 0.95 OR Root Mean Square Error or Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06 OR Standardised Root Mean Square Residuals (SRMR) < 0.08a Item Response Theory (IRT)/Rasch No violation of unidimensionalityb: CFI or TLI or comparable measure > 0.95 OR RMSEA < 0.06 or SRMR < 0.08 AND No violation of local independence: residual correlations among the items after controlling for the dominant factor < 0.20 OR Q3s < 0.37 AND No violation of monotonicity: adequate looking graphs OR item scalability > 0.30 AND Adequate model fit IRT: X2 > 0.001 Rasch: infit and outfit mean squares ≥; 0.5 and ¾ 1.5 OR Z-standardised values > - 2 and < 2 |

| ? | CTT: not all information for (+) reported IRT/Rasch: Model fit not reported |

||

| - | Criteria for (+) not met | ||

| Hypothesis testing for construct validity | The degree to which the scores of a measure are consistent with hypotheses based on the assumption that the outcome measure validly measures the construct being measured. | + | At least 75% of the results are in accordance with the hypothesis |

| ? | No hypothesis defined (by the review team) | ||

| - | Less than 75% of the results are in accordance with the hypothesis | ||

| Criterion validity | The extent to which the scores of the measure are an adequate reflection of a “gold standard.” | + | Correlation with gold standard ≥; 0.70 OR area under the curve (AUC) ≥; 0.70 |

| ? | Not all information for (+) reported | ||

| - | Correlation with gold standard < 0.70 OR AUC ≥; 0.70 | ||

| Reliability (the degree to which the measurement is free from measurement error) | |||

| Internal consistency | The degree of interrelatedness among the items of the assessment measure. | + | At least low evidence (as per GRADE) for sufficient validity AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) ≥; 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscale |

| ? | Criteria for “at least low evidence (as per GRADE) for sufficient structural validity” not met | ||

| - | At least low evidence (as per GRADE) for sufficient structural validity AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) < 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscale | ||

| Reliability | The scores given by clinicians are the same for repeated measurement under different conditions (i.e., test–retest, inter-rater, intra-rater). | + | Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), weighted Kappa, Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient ≥; 0.70 |

| ? | ICC, weighted kappa, Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient not reported | ||

| - | ICC, weighted kappa, Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient < 0.70 | ||

| Measurement error | The degree to which the systematic and random error of scores is not attributed to the changes in the construct being measured. | + | Smallest detectable change (SDC) or limits of agreement (LoA) or CV*√2*1.96 < minimal important change (MIC), % specific agreement > 80% |

| ? | MIC not defined | ||

| - | SDC or LoA > MIC, % specific agreement < 80% | ||

| Responsiveness | The ability of an instrument to detect change over time within the construct being measured. | + | At least 75% of the results are in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC ≥; 0.70 |

| ? | No hypothesis defined (by the review team) | ||

| - | Less than 75% of the results are in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC < 0.70 | ||

Definitions and criteria for good measurement properties.

(+) = sufficient, (−) = insufficient, ()? = indeterminate.

To rate the quality of the summary score, the factor structures should be equal across studies.

Unidimensionality refers to a factor analysis per subscale, while structural validity refers to a factor analysis of a (multidimensional) outcome measure.Background colours were chosen to reflect the graded scoring system in place.

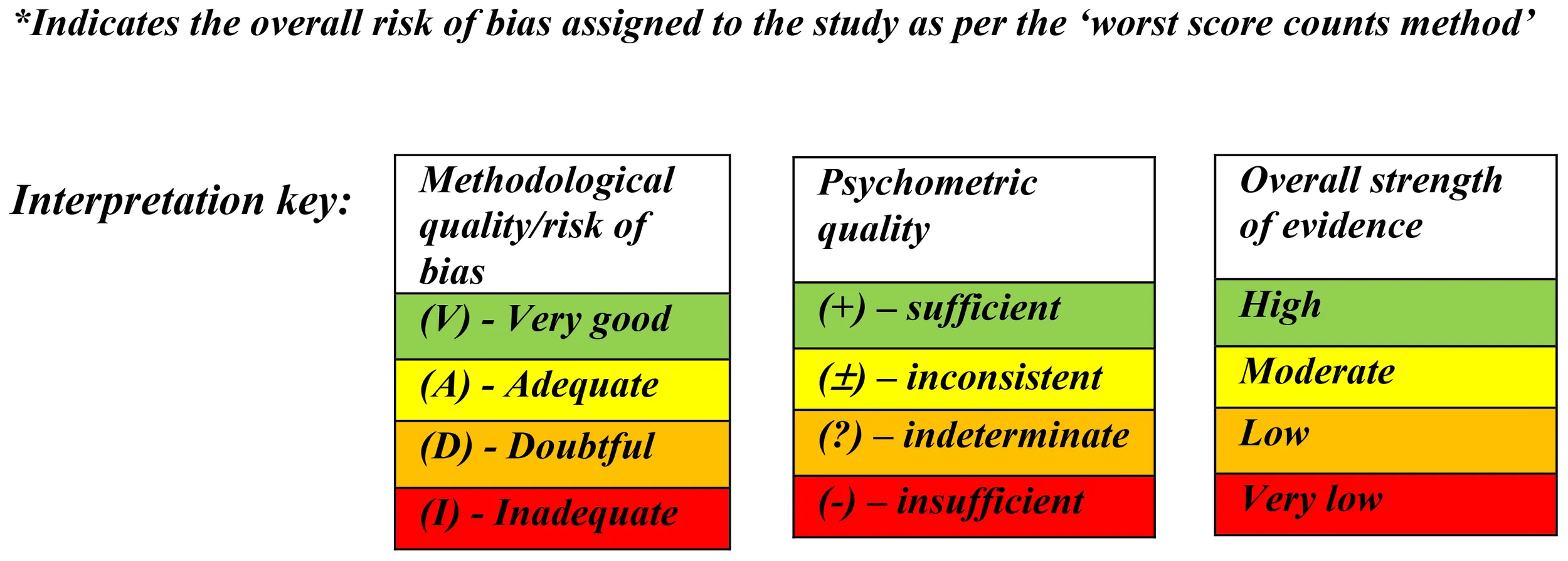

Each study was assessed for methodological quality and was rated using the COSMIN scale’s 4-point scoring system (4 = “very good,” 3 = “adequate,” 2 = “doubtful,” 1 = “inadequate”). An overall score for a study’s risk of bias was then determined by taking the lowest rating among all criteria for each category, known as the “worst score counts” method. This method was followed because poor methodological qualities should not be compensated for by good qualities (42).

Part B: quality appraisal of the psychometric properties of each measure

The main reviewer appraised the quality of the reported results in terms of psychometric properties for each measure. Each of the eight psychometric properties (except content validity) was rated as “sufficient” (+) if results were determined to provide good evidence of a measure exhibiting this property, an “indeterminate” (?) rating was assigned if results were not consistent, not reported, or appropriate tests had not been performed and an “insufficient” (−) rating was assigned when appropriate tests had been performed, but the results were below the COSMIN checklist’s standards.

Content validity (i.e., in terms of relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) was rated as either sufficient (+), insufficient (−), inconsistent (±) or indeterminate (?). A subjective rating regarding content validity was also considered (41). The evaluated results of all studies for each measure were summarised. The focus at this stage changed to the measures, whereas in the previous substeps, the focus was on the individual studies.

Part C: quality grading of the evidence

The strength of evidence for each category for each measure was determined based on the methodological quality and risk of bias (Part A) and the psychometric properties (Part B). The main reviewer utilised the modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (38) to assess the quality of the evidence provided for each measure (Table 3). Detailed information on the GRADE approach can be found in the COSMIN user manual (38, 41, 42). As per COSMIN guidance, if studies were rated as being “inadequate” overall (Part A), the GRADE rating of “very low” was given for the content validity categories. If studies were rated as being of “doubtful” quality overall, a GRADE rating of “low” was given for content validity categories (42). COSMIN guidelines recommend that studies determined to be “inadequate” should not be rated further. However, in order to gain a comprehensive overview of each measure, we rated all studies in full.

Table 3

| Quality level | Definition |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the true measurement property lies close to that of the estimate of the measurement property. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the measurement property estimate: the true measurement property is likely to be close to the estimate of the measurement property, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

| Low | Our confidence in the measurement property estimate is limited: the true measurement property may be substantially different from the estimate of the measurement property. |

| Very low | We have very little confidence in the measurement property estimate: the true measurement property is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the measurement property. |

Definitions of quality levels using the GRADE approach.

Background colours were chosen to reflect the graded scoring system in place.

As current COSMIN criteria do not include guidance regarding the rating of exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the criteria for assessing structural validity were adapted, comparable to Wittkowski et al. (30). EFAs were rated as “sufficient” if > 50% of the variance was explained (55) and studies using EFA could only be rated as “adequate” rather than “very good” for risk of bias.

When confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was also reported alongside EFA, the lower quality evidence of EFA was ignored and the study was rated according to the CFA results reported. If the percentage of variance accounted for and/or model fit statistics were not reported in studies, an “indeterminate” rating was given.

The GRADE approach to rating results also takes into consideration the risk of bias, inconsistency (unexplained inconsistency of results across multiple studies), imprecision (total sample size in the studies) and indirectness (evidence from different populations than the population of interest) (40, 41). The GRADE approach follows the assumption that all evidence is of high quality to begin with. The quality of the evidence is subsequently downgraded to “moderate,” “low,” or “very low” when there is a risk of bias, unexplained inconsistencies in the results, imprecision (less than 100 or less than 50 participants) or indirect results (41).

Results

Review process

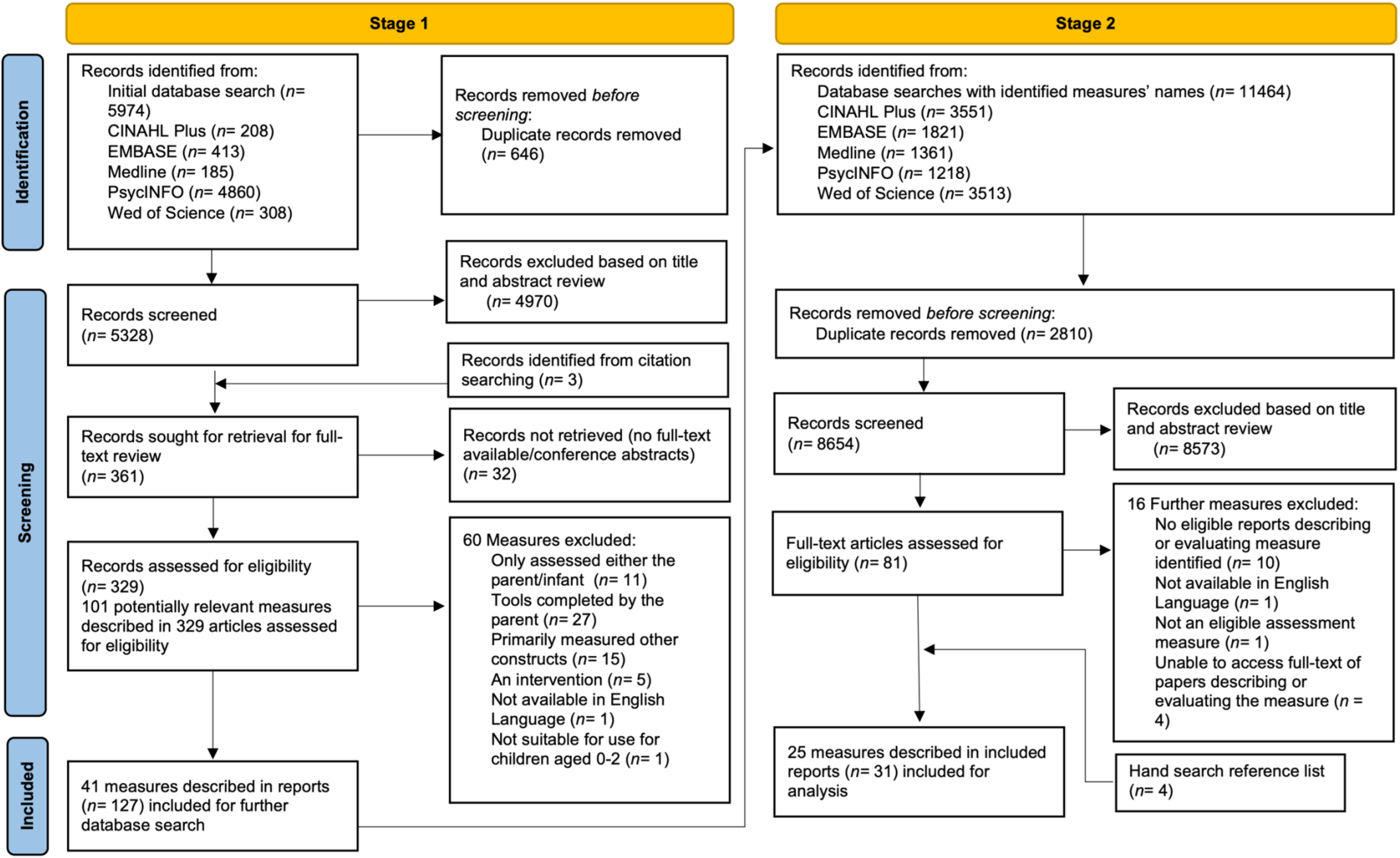

At Stage 1, 5,974 papers were identified (see Figure 2 for details). After removing duplicates at this stage, the titles and abstracts of 5,328 records were screened. The full texts of 329 papers were examined against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leading to the identification of 41 potentially eligible parent–infant measures.

Figure 2

PRISMA flow diagram of both stages of the search process.

At Stage 2, with the titles of the identified measures as the search terms, 11,464 records were identified. After removing 2,810 duplicates, 8,654 records were screened, with 8,573 records subsequently excluded based on title and abstract review. This process resulted in 81 full text articles, which were assessed for eligibility at Stage 2.

All decisions regarding inclusion and exclusion of studies and measures were discussed by all authors and any discrepancies were resolved (for a list of excluded measures, please see Appendix B in Supplementary Materials). After a detailed and comprehensive assessment of the identified studies from Stage 2, 31 studies describing the development of and/or validation of 25 measures were included in this review.

Study characteristics

After completion of Stage 2, the publication dates of the included studies ranged from 1978 to 2023 and sample sizes ranged from ten (56) to 838 participants (57). The greatest number of studies came from the United States of America (USA; n = 19), with the remaining studies from the United Kingdom (UK; n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Denmark (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Peru (n = 1), and Switzerland (n = 1). Studies were conducted using either a non-clinical sample (n = 17) or a clinical sample (n = 9), or both a clinical and non-clinical comparison sample (n = 5). Further details on measure development, aspects of clinical utility and characteristics of each of the included measures and studies are provided in Table 4.

Table 4

| Developer(s)/author(s), date and country | Focus of measure | Scoring format | Method of assessing the parent–infant relationship and time taken to administer | Age of child assessment designed for use | Constructs assessed (parent/infant/dyad) | Development of measure including study participants, sample size and population | Details of costs and training (if applicable) and access to the measure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item number | Name of subscales (number of items) | Total score range/Interpretation | ||||||||

| 1 | Assessment of Mother–Infant Sensitivity (AMIS) | |||||||||

| Price (1983) (58) USA |

The quality of the early mother–infant interactions, specifically in terms of sensitivity, in a feeding context. | 25 | Parent scales (15 items in total): 1. Spatial distance (1) 2. Holding style (1) 3. Predominant maternal mood/affect (1) 4. Verbalisation (tone) (1) 5. Verbalisation (content) (1) 6. Visual interaction behaviour (1) 7. Modulation of distress episodes (1) 8. Caregiving style (1) 9. Stimulation of infant (1) 10. Response to changing levels of infant activity (1) 11. Burping style (1) 12. Stimulation to feed (1) 13. Manner of stimulation to feed (1) 14. Frequency of stimulation to feed (1) 15. Response to infant satiation (1) Infant scales (7 items in total): 16. Predominant infant state (1) 17. Predominant infant mood/affect (1) 18. Vocalizations (1) 19. Distress (1) 20. Visual behaviour (1) 21. Posture (1) 22. Response to stimulation to feed at satiation (1) Dyadic scales (3 items in total): 23. Synchrony in response to pleasurable affect (1) 24. Regulation of feeding at initiation (1) 25. Regulation of feeding at termination (1) |

5-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 5). 1–5 points for each item, so total score ranges from 25 to 125. Higher values indicate greater “sensitivity.” The items within the scale can be grouped into three classes of behaviour including: holding/handling, social/affective and feeding/caregiving. |

Ratings are made from observations of 15- to 30-min videotaped recordings of the mother–infant interactions. Total scores are given from observations of the entire videotaped interaction rather than sections within the videotaped recording. Dyads can be observed at home or in clinic settings. Maternal behaviour is not scored within the context of the infant’s needs or the mother’s response to infant behaviour; thus, the scale is designed to identify areas of less sensitive maternal behaviour. |

0–3 months. A focus on feeding, so the scale intended to evaluate breastfeeding and/or bottle feeding of a baby less than 3 months old. Thus, limited utility in other contexts and outside of this age range. |

Parent, infant and dyad | The study sample consisted of 53 dyads in a feeding-context. The infants were 4–6 weeks old. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status not reported. No further information given in text on sample used or measure development (Price, 1983) (58). Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Not applicable Scale is free to access in the appendix of Price (1983) (58). Training: No specific training courses or reliability assessments required or reported online or in study (Price, 1983) to utilise this measure. Access: Scale is freely available and easily accessible in the Appendix of Price (1983) (58). |

|

| 2 | Attachment Q sort | |||||||||

| Waters and Deane (1985) (59) USA |

An assessment of the parent–infant relationship within the context of attachment. The Q-set covers a broad range of secure base and exploratory behaviour, affective responses, social referencing behaviours and social cognition. | 100 | Parent observed for the following constructs (100 items in total): 1.Attachment/exploration balance (12) 2. Differential responsiveness to parents (9) 3. Affectivity (19) 4. Social interaction (18) 5. Object manipulation (14) 6. Independence/dependency (14) 7. Social perceptiveness (8) 8. Endurance/resiliency (6) Infant observed for following constructs: Security Dependency Sociability Social desirability |

Rankings range from perfectly positive score (1.0 – secure attachment) to perfectly negative score (−1.0 – insecure attachment). Clinicians are required to rank order items on cards on a Q-sort grid. Each item is scored in terms of its placement (piles 1–9) on the Q-sort grid (e.g., items in pile 9 receive scores of 9, items in pile 1 receive scores of 1). Printed on each card is each item’s title and more specific descriptive statements. These items make specific reference to a behaviour of the parent or infant and make up the Q-set. |

Live observations by clinicians of the child interacting with the parent. It is recommended observers complete 6–8h of observations over 2 occasions to complete the Q sort. Dyads can be observed at home or in clinic settings. |

12–48 months Not suitable for newborns |

Parent and infant scales | This measure was developed and revised over several stages to subsequently compile a 100 item Q-set. This was described as developed through home visits and reviewing relevant literature (Waters & Deane, 1985) (59). Forty-three PhD experts provided Q-sort definitions of the relevant constructs regarding attachment behaviours. Over 100 infants and their mothers were recruited to develop the Q-set. The infants were aged 12–36 months. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status not reported. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Q-set items free to access in appendix of Waters and Dean (1985) (59). Training: No specific training courses identified or available online. Stated in paper that observers need to be trained and able to observe the child for an average of 6–8h. Reliability assessments required. Access: Q-set items free to access in freely available in appendix of Waters and Dean (1985) (59). |

|

| 3 | Bethlem Mother–Infant Interaction Scale (BMIS) | |||||||||

| Kumar and Hipwell (1996) (26) UK |

Assessing the quality of mother–infant interactions in a psychiatric context | 7 | Parent scales (6 items in total): 1. Eye contact (1) 2. Physical contact (1) 3. Vocal contact (1) 4. Mother’s mood (1) 5. General routine (1) 6. Assessment of risk (1) Infant scale (1 item in total): 7. Baby’s contribution to interaction (1) |

5-point rating scale (ranging from 0 to 5). 0 indicates the mother is interacting with the child in an appropriate, sensitive and well-organised way. A score of 3 indicates the mother was unable to sustain any meaningful dialogue or interaction with the infant. A score of 4 indicates very severe disturbances of maternal behaviour resulting in physical separation from the child. |

A seven-day observation period. Scored by two members of staff on a weekly basis. Staff members are instructed to review their clinical notes from the past week, usually during handover meetings and arrive at a consensus as to the worst level of interaction observed over the past week. Designed and validated for use in inpatient settings. |

0–12 months | Parent and infant scales | Measure developed out of clinical descriptions of key areas of disturbance and dysfunction. Study authors describe the use of pilot work to finalise subscales. Kumar and Hipwell (1996) also described developing descriptive anchor points into the scale to reduce the influence of bias from the raters and facilitate ratings. The study sample consisted of 78 mothers (age 18–41 years) and 78 infants (1–36 weeks) in a Mother and Baby Unit. Ethnicity not reported. The admission had to have lasted longer than 2 weeks so that at least two sets of nurse’s observations could be made. Clinical sample. |

Costs: Scale is free to access and available online. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr216.pdf?sfvrsn=12b1e81c_2 Training: This measure is aimed to be completed by nurses who were in daily contact with the mothers on the ward. So it is assumed a clinical training background is required; however, the study authors specified that the aim of developing the measure was to remove the need for specialist training for the raters. Access: No specific training courses or reliability assessments required or reported in study (Kumar & Hipwell, 1996) (26) to utilise this measure. Scale is free to access. |

|

| 4 | Child-Adult Relationship Experimental Index (CARE-Index) | |||||||||

| Crittenden (1988) (27) USA |

The quality of the adult–infant interaction. Focuses on assessing adult sensitivity in order to identify any risks | 14 | Parent scores (3 items in total): 1. Sensitive (1) 2. Controlling (1) 3. Unresponsive (1) Infant scores (4 items in total): 4. Cooperative (1) 5. Difficult (1) 6. Passive (1) 7. Compulsive Compliant (1) |

Allocation of 14 points among three adult patterns and, separately 14 points among the four child patterns of behaviour. The scores on the scales range from 0 to 14, with 0 sensitivity being dangerously insensitive, 7 normally sensitive and 14 outstandingly sensitive. |

Measure requires 3–5 min of semi structured play observation, which is then videotaped and coded by trained coders. Can be completed at home or in clinical settings. |

0–48 months | Parent and infant scales (adult–infant interactions – the adult does not have to be the parent) | Description of measure development not given. Study sample consisted of 121 mother–child dyads. Families were referred via social services or the public health department. referrals of “maltreating” families, mostly of very low-income. The children ranged in age from 2 to 48 months. Mothers age range was 15–38 years. Ethnicity of infants was reported as either Caucasian or African American. No information on socioeconomic status reported. Each family was seen four times. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Manual not free to access. Online training costs £850–£1,050. Training: Nine days, includes teaching, the manual and a reliability test. Access: training accessible through https://www.psychologyexperts.org/2018/02/20/care-index-training/ |

|

| 5 | Coding Interactive Behaviour (CIB) | |||||||||

| Feldman (2012) (60) (Information taken from Stuart et al., 2023) (57) Denmark |

Parent–infant interaction quality, with a focus on social interactions | 33 | Parent scales (18 items in total): 1. Parental sensitivity 2. Parental intrusiveness 3. Parental limit setting Infant scales (8 items in total): 4. Child social involvement 5. Child withdrawal/negative emotionality Dyadic scales (5 items in total): 6. Dyadic reciprocity 7. Dyadic negative states As well as two items representing the lead-lag of the interaction. |

5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5). All items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 representing a minimum level of behaviour, to 5 representing a maximum level of the attitude/behaviour. Half-point increases. Total score ranges from 33 to 165. Clinicians first examine the parent and infant behaviours separately, followed by the interactions between the dyad. |

Observations of videotaped recordings of 5 min of ‘free-play’ interactions between the adult and infant during a home visit. The recording is then coded by trained coders. |

2–36 months | Infant, parent and dyad | Measure described to have been developed based on theory and research in the field of early social development (Stuart et al., 2023) (57). 419 mother–infant dyads. Infants were aged 2-6 months. Clinical sample, consisting of mothers with depression and/or anxiety. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status not reported. |

Costs: Manual and scale not free to access, training costs $2,500. Training: Three-day training seminar available online via Zoom. Access: Training accessible through https://ruthfeldmanlab.com/coding-schemes-interventions/ |

|

| 6 | Dyadic Mutuality Code (DMC) | |||||||||

| Censullo et al. (1987) (61) USA |

Parent–infant interactions and levels of synchrony | 6 | Parent scales (2 items in total): 1. Maternal sensitive responsiveness (1) 2. Maternal pauses (1) Infant scale (1 item in total): 3. Infant clarity of cues (1) Dyadic scales (3 items in total): 4. Mutual attention (1) 5. Positive affect (1) 6. Turn-taking (1) |

Each item is given score of 1 or 2 and a total score, rated as synchronous or low synchronous.). (Score of 1 or 2 for each item where 1 = absent, 2 = present) The total score ranges from 6 to 12. A score of 6–9 is ranked a low synchronous and scores of 10–12 are ranked as synchronous. The infant and adult behaviour is observed dyadically as an interactive unit. |

Observations of 5 min of free-play between parent and infant, rated by clinicians with a scoring sheet. Original study described videotaping families in a laboratory setting. Unclear if can also be used by clinicians in home settings. |

0–6 months | Infant, parent and dyad | The DMC evolved from the Dyadic Interaction Code The six scale items were included because it was established these items are relevant components of synchronous interaction in literature. Therefore, they represent the concept and definition of synchrony. (Censullo et al., 1987) (61). The participants were selected from a child development unit at a children’s hospital. The sample consisted of 20 term and 20 preterm infants and their mothers. Ethnicity reported as all Caucasian participants and all were described to be of comparable socioeconomic status. Clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: Study author described training a research associate to use the DMC – so there is an implication that some training is required. Access: No access to training or manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 7 | Emotional Availability Scales (EAS) | |||||||||

| Biringen, Robinson and Emde (2000) (37) (Information taken from: Aran et al., 2022) (62) USA |

An evaluation of the quality of relationship between parent and child, in terms of levels of synchrony and sensitivity | 42 | Parent scales (28 items in total): 1. Sensitivity (7) 2. Structuring (7) 3. Non-intrusiveness (7) 4. Non-hostility (7) Infant scales (14 items in total): 5. Responsiveness to adult (7) 6. Involvement to adult (7) |

7-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 7). Higher values indicate higher sensitivity between the parent and infant and reflect the better overall quality of the relationship. Total score ranges from 7 to 42. Within the context of the parent–infant relationship, the observer is instructed to utilise context and clinical judgements to infer the appropriateness of observed behaviours. |

Observations of the dyad at home, childcare centre, free play or structured teaching. Observers rate these interactions using a coding system. Live or videotaped. 15–20 min observation minimum. |

0–14 years | Parent and Infant only (no dyadic scales) | This measure was developed for use among populations with clinical or developmental risk factors, including between depressed and nondepressed mothers and their infants. Informed by attachment research (Aran et al., 2022) (62). Study sample consisted of 35 mother–child dyads. No information on ages, socioeconomic status or ethnicity reported. Clinical sample. |

Costs: Training, scale and manual costs available upon request through website. Training: 3-day face-to-face, group training or self-paced distance training using reading, lecture and practice on 10 training videos required. Training and reliability certifications required. Access: training accessible through https://emotionalavailability.com/courses/ea-basic/ |

|

| 8 | Family Alliance Assessment Scales for Diaper Change Play (FAAS-DCP) | |||||||||

| Rime et al. (2018) (63) Switzerland |

An evaluation of the quality of family relations and family functioning | 9 | Parent(s)-infant ratings (9 items in total): 1. Readiness to interact (1) 2. Gaze orientation (1) 3. Inclusion of partners (1) 4. Coparental coordination (1) 5. Role organisation (1) 6. Parental scaffolding (1) 7. Shared and co-constructed activities (1) 8. Sensitivity (1) 9. Family warmth (1) |

5-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 5). The measure consists of 9 interactive dimensions, rated on a 5-point scale. A score of 5 indicates optimal functioning and a score of 1 indicates significant dysfunction is observed. Total score ranges from 9 to 45. The observation is made up of four parts, a score is thus assigned to each of these parts. The score on every dimension is then determined by summing the score on each part, ranging from 4 to 20. The observation also involves an assessment of the perceived quality of family alliance in terms of cooperative, collusive and disordered alliance. |

The FAAS-DCP is structured in four parts of observations of interactions during the changing of diapers. Part one, one parent begins to change the diaper of the infant and the other observes the interaction without intervening. These roles then swap in the second part, the second parent becomes active and finishes the process of diaper changing. Both parents are together with the infant to share a moment, in the third part. Examples of this moment include, stroking, smiling at or soothing the infant. The final part involves asking the parent to have a discussion in the presence of the baby. Time taken to administer unclear. All interactions during the diaper change are recorded so that videotaped recordings can be coded according to the manual. Clinic settings only. Equipment required includes table, changing mat, diapers, a bin and four cameras. |

The first three weeks of the child’s life | Dyadic/triadic interactions | The measure was developed based off Lausanne Trilogue Play (LTP, Gatta et al., 2016) (64). Whereas the LTP is based on a play task, the DCP is mainly based on a caregiving task. The difference being that a play activity was changed to a practical, caring activity mimicking everyday life. Good level of detail given in paper as to theoretical background and decision making around measure development. The coding system FAAS-DCP is modelled on the FAAS (Favez et al., 2011) (65). The measure was developed based off three validation studies, which involved one sample from two maternity wards in Switzerland. All the families were White European. The sample consisted of 44 triads and their newborns. Clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown Training: All interactions are coded so some level of training required to code. Access: FAAS-DCP coding system unpublished and not available in Rime et al. (2018) (63)or online. No training courses or access to manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 9 | Infant–Parent Social Interaction Code (IPSIC) | |||||||||

| Baird et al. (1992) (66) USA |

Assessing the quality of the parent–infant relationship within free-play scenarios between infant and parent. | 9 | Parent scales (4 items in total): 1. Response contingency (1) 2. Directiveness (1) 3. Intrusiveness (1) 4. Facilitation (1) Infant scales (4 items in total): 5. Initiation (1) 6. Participation (1) 7. Signal clarity (1) 8. Intentional communicative acts (1) Dyad scales (1 item in total): 9. Theme continuity (1) |

3-point rating scale (ranging from high, middle, low) A “High” score gives an indication of a higher frequency of behaviours and “low” scores indicate no specified behaviours were demonstrated. Only when social interaction occurs, can infant participation, infant initiation and dyadic theme continuity then be coded as present. Additonally, intrusiveness and facilitation are not compatible interactional constructs and so cannot co-occur. |

Observations of the parent and infants’ ‘free play’, ideally at home, videoed and coded by trained coders. More than 5 min of videotaped recordings of infant–parent play is required. Coding is split into twenty fifteen-second intervals of specific behaviours. The first 5 min are not coded. Parents are asked to play as they normally do. The manual provides examples and nonexamples for each construct, additionally, five standard videotapes were developed to facilitate and aid coders in their training. |

0–36 months. | Infant, parent and dyad. | A description of measure development is given as based on theoretical and empirical evidence for promoting optimal infant development. Definitions, examples, possible rationales for inclusion and references for each construct are given in Baird et al. (1992) (66). The study sample consisted of 159 infants ranging from birth to 31 months and their mothers (biological, adoptive and foster mothers). Infants were recruited from hospitals, early intervention programs and advertisements in newspapers. Infants were either normally developing, or there were identified environmental or biological risks for developmental delay. Ethnicity of the mothers was White and African-American and socioeconomic status was described as diverse. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Coding sheet to free to access in Baird et al. (1992) (66) Training costs unknown. Training: Training required – Baird et al. (1992) also details procedures for guiding coding decisions to ensure reliability, as well as, decision trees to provide guidelines for sequencing the series of decisions required in coding. The paper also explains five 1h group training sessions and independent coding are required. Observers are required to obtain minimum of 75% exact agreement on training tapes. Access: Procedure for training coders, establishing and maintaining reliability, decision trees, standard tapes and guidelines (manual) are stated as available from the first author upon request. |

|

| 10 | LoTTS Parent–Infant Interaction Coding Scale (LPICS) | |||||||||

| Beatty et al. (2011) (67) USA |

Observational measure of the quality of parent–infant interactions. A particular focus on responsivity, sensitivity and warmth. | 13 | Global ratings (3 items in total): 1. Responsiveness (1) 2. Sensitivity (1) 3. Warmth (1) Behavioural counts (10 items in total): 4. Look (1) 5. Chasing (1) 6. Touch (1) 7. Negative touch (1) 8. Talk (1) 9. Negative talk (1) 10. Smile (1) 11. Grimace/frown (1) 12. Positive child response (1) 13. Negative child response (1) |

The three global ratings: responsiveness, sensitivity and warmth are rated on a 3-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 3). The behavioural counts are noted and coded for presence of or absence of at each occurrence during the interaction. Total score ranges from 13 to 19. |

The measure consists of a 4-min videotaped recording of the parent and infant playing and interacting with a toy. Either at home or clinical settings. |

0–3 months | Dyad | Measure was developed based off adaptation from the Parent Infant Interaction Observation Worksheet (Beatty et al., 2011) (67), which grew out of Applied Behavioural Analysis literature. The LPICS is closely based on the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale in structure (Moyers et al., 2005) (68). 45 mother–infant dyads. Participants were all women who were recruited while pregnant from OB/GYN clinics in a large urban area. The measure was designed to be used with at-risk parenting populations, but not those with serious mental health disturbance. No information reported on ethnicity of the sample and all participants described as being of low socioeconomic status. Clinical and non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: Reliability assessment described as three rounds of coding and 8.5h of training in order to obtain adequate reliability. Access: No training courses or access to manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 11 | Manchester Assessment of Caregiver–Infant Interaction (MACI) | |||||||||

| Wan et al. (2017) (69) UK |

Designed to encapsulate the qualities of parent, infant and dyadic interactions. | 7 | Caregiver (2 items in total): 1. Sensitive responsiveness (SR) (1) 2. Nondirectiveness (1) Infant (3 items in total): 3. Attentiveness to caregiver (1) 4. Affect (1) 5. Liveliness (1) Dyad (2 items in total): 6. Mutuality (1) 7. Engagement intensity (1) |

7-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 7) A sore of 1 indicates minimal/very low quality of interaction to a score of 7 indicating high incidence of the behaviour. Total score ranges from 7 to 49. The measure is made up of seven rating scales, covering broad aspects of interaction between a caregiver and their infant. |

A 6- to 20-min videotaped recording of continuous play interactions. The videotaped recording starts once the dyad is settled in interaction yet the situation. The dyad are instructed to sit on the floor/mat either during a home visit or clinic premises. The parents are then instructed to engage in play as they normally would at home. Each videotaped recording is typically reviewed twice (or more), in order to note the observational sequence and initial ratings with the manual and then reviewed again so as to finalise the ratings. |

3–15 months | Parent, infant and dyad | Measure described as developed in alignment with the transactional model of development (Sameroff, 2009) (70) [which parent–infant interactions at the level of genes, as bidirectional processes. It’s constructs and scale distributions are designed to be suitable for high and low risk populations (Wan et al., 2017) (69). Study sample consisted of 147 healthy parent–infant dyads at 3–10 months post-partum. Three community-based samples used. No information on ethnicity of the participants or socioeconomic status. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: 3 day face-to-face workshop. Consisting of an extensive practice phase with supervision and feedback and a two-part reliability assessment process. In total, 75–85h is spent in training and coding to achieve certification (Wan et al., 2017) (69). Access: Comprehensive coding manual and training package detailed as available in Wan et al. (2017) (69); however, no specific training courses, scale or manual could be located online or in Wan et al. (69) to use this measure. |

|

| 12 | Massie-Campbell Scale of Mother–Infant Attachment Indicators During Stress (M-C ADS) | |||||||||

| Massie and Campbell (1986) 76] (71) (Information taken from Nóblega et al., 2019; Cárcamo et al., 2014) (72, 73) Peru/Netherlands |

Designed to assess the quality of interactions between mothers and children, in terms of attachment and in situations of moderate stress. | 14 | Parent scales (7 items in total): 1. Gazing (1) 2. Vocalising (1) 3. Touching (1) 4. Response to touch (1) 5. Holding (1) 6. Affect (1) 7. Proximity (1) Infant scales (7 items in total): 8. Gazing (1) 9. Vocalising (1) 10. Touching (1) 11. Response to touch (1) 12. Holding (1) 13. Affect (1) 14. Proximity (1) |

5-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 5). (1 = very avoidant behaviour, 3 and 4 = typical attachment behaviour, 5 = clinging and unusually strong reaction to stress). Each of the behaviours is scored on a scale of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or as not observed. Each behaviour is then rated as either secure or insecure. A behaviour with a score of 3 or 4 is assigned a rating of secure and behaviours with scores of 1, 2, or 5 are rated as insecure. The dyad is rated as secure when < 50% of the behaviours are rated as secure; if not, they are rated as insecure. |

Observations of the parent and infant interacting together during a mildly stressful event, lasting approximately 10 min. Examples of mildly stressful situations are given as dressing, bathing, playing, family mealtimes and mother–infant separations and reunions at a daycare centre. Videotaped recordings are scored by trained professionals. |

0–18 months | Parent and Infant only (not dyad) | The developers of the ADS designed this scale to be quick and inexpensive to detect difficulties within mother–infant interactions. Another aim of measure development was to increase clinicians’ awareness of infants’ psychological development. Both mother and infant behaviour are scored. Therefore, observers separately code mother and infant attachment behaviours (Nóblega et al., 2019; Cárcamo et al., 2014) (72, 73). The study samples consisted of 32 mothers and their children all from Peru, the infants were aged between 8 and 10 months. No details regarding ethnicity or socioeconomic status reported (Nóblega et al., 2019) (72) and 69 low socioeconomic status Dutch dyads of White origin (Cárcamo et al., 2014) (73) Both non-clinical samples. |

Costs: Both the manual and scale are free to access. Training: requires self-study of the manual. Training required to code interactions, as described in Nóblega et al. (2019) (72) and rating of 16 training videos to ensure reliability. Access: Both the manual and scale are free to access and can be found through the following website: https://www.allianceaimh.org/ads-scales |

|

| 13 | Monadic Phases | |||||||||

| Tronick, Als and Brazelton (1980) (56) USA |

A system for describing infant-adult face to face interactions. The importance of interaction (including between parents and infants) is emphasised and described as a structured system of mutually and reciprocally regulated units of behaviour. |

100 | Maternal scales (57 items in total): 1. Vocalisation (9) 2. Direction of Gaze (4) 3. Head orientation (13) 4. Facial Expression (13) 5. Body Position (10) 6. Specific Handling of the Infant (8) Infant scales (43 items in total): 7. Vocalisation (8) 8. Direction of Gaze (4) 9. Head orientation (9) 10. Facial Expression (13) 11. Body Position (9) |

Scale consists of 100 items, each scored for presence of or absence of. Total score ranges from 0 to 100. Infant monadic phases: protest, avert, monitor, set, play and talk. Maternal monadic phases: avoid, avert, monitor, elicit, set, play, and talk. |

Observations of an interaction between an infant and a parent. The mother is instructed to play with her baby. 3-min videotaped recording. Each behaviour is then categorised into monadic phases on a second-by-second basis, then analysed by observers. Videotaping is carried out in a laboratory setting. Scoring is then completed from the videotaped recordings. Each second-by-second combination of behaviours is transformed into one of seven Monadic Phases. |

0-6 months | Parent and Infant only (not dyad) | Measure development described as informed by previous research on behaviour (Brazelton et al., 1975) (74) and face to face interactions (Stern et al., 1977) (75). The measure was designed to build on previous research and overcome their limitations. It is designed to segment the interaction into separate units of behaviour that are called monadic phases (Tronick, Als & Brazelton, 1980) (56). The study sample consisted of 5 infant-mother pairs. The infants age range was 80 to 92 days old. No information on ethnicity or socioeconomic status reported. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Scoring tables can be found free in Tronick Als and Brazelton (1980) (56). Training: Specific training courses unknown. Reliability assessments required at 90% absolute agreement for each category. Access: No specific training courses or access to manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 14 | Mother-Infant/Toddler Feeding Scale (M-I/TFS) | |||||||||

| Chatoor et al. (1997) (76) USA |

Assesses the quality of the mother–infant relationship in a feeding context | 46 | Parent(s)-infant ratings (46 items in total): 1. Dyadic reciprocity (16) 2. Dyadic conflict (12) 3. Talk and distraction (4) 4. Struggle for control (7) 5. Maternal non-contingency (7) |

4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3). Rated on how often and how intensely each of the behaviours occurs (0 = none, 1 = a little, 2 = pretty much and 3 = very much). Total score ranges from 0 to 138. The scale consists of 46 mother and infant behaviours, which produce 5 subscale scores and are rated along 4 points at the end of the feed. |

A 20-min observation completed in a research or clinical setting. Videotaped recordings of parent–infant interactions as the mother feeds the infant, rated by a trained observer. Scoring is then completed from the videotaped recordings. |

1–36 months. However, it should also be noted the scale has not yet been validated for use with infants less than 5 weeks of age. |

Dyad only. | Measure development described as informed by a series of studies conducted. Initially, a group of items describing relevant behaviours of mothers and infants was pooled and generated by experienced clinicians (Chatoor et al., 1997) (76). A pilot study was completed in which the study sample consisted of 20 mother–infant pairs. Infants age range: 5 weeks to 32 months. A second larger validation study was then completed with 74 infants with feeding disorders and 50 normal comparison subjects. These infants ranged from 6 weeks to 36 months. Ethnicity (White/African-American) and socioeconomic status reported. Forty infants participated in a reliability study. Infants were aged 7 months to 3 years. Ethnicity reported as White, African-American, Hispanic and Asian. Clinical and non-clinical samples. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: involves scoring 10–12 feeding videotapes, comparing scores with a trained rater and achieving a reliability assessment of 80% agreement. Access: No specific training courses or access to manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 15 | Mutual Regulation Scales (Face-to-face still face paradigm) – MRS | |||||||||

| Tronick et al. (1978) (77) USA |

Infant facial expression in response to caregiver changes in facial expressions | 111 | Parent scales (57 items in total): 1. Vocalising (9) 2. Head position (13) 3. Body position (10) 4. Specific handling of the infant (8) 5. Direction of gaze (4) 6. Facial expression (13) Infant scales (54 items in total): 7. Vocalisation (7) 8. Direction of gaze (4) 9. Head orientation (9) 10. Head position (2) 11. Facial expression (13) 12. Amount of movement (8) 13. Blinks (2) 14. Specific hand movements (5) 15. Specific foot movements (2) 16. Tongue placement (2) |

Each item is rated “yes or “no” for presence of or absence of behaviours demonstrated. Separate ratings for parent and infant. From the videotaped recording, raters categorise and score the infant’s vocalizations, direction of gaze, head and body position, facial ex- pression and movement; and the mother’s vocalizations, head position, body position, direction of gaze, facial expression and handling of the infant. |

Observations take place in a double room with a unidirectional mirror and recording system. A laboratory setting. Videotaped recordings are micro-analytically coded. The mother first interacts normally with infant for 3 min, a 30-s break, followed by remaining “still faced” for 3 min. Scoring is completed by two observers for each 1-second time interval as the tape runs at 1/7th of its normal speed. |

0–10 months | Parent and infant (no dyadic scales) | Measure development was informed by previous research and studies of face-to-face interactions between mothers and infants (Tronick et al., 1978; Brazelton et al., 1975) (74, 77). Study sample consisted of 7 mothers and their healthy full-term infants, ranging in age from 1 to 4 months. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status not reported. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Scoring sheet freely available in appendix of Tronick et al. (1978) (78). Training: Training requirements unknown. Inter-scorer reliability should be maintained at above.85 for each category scored. Access: No specific training courses or access to manual could be located online to use this measure. |

|

| 16 | Mutually Responsive Orientation (MRO) | |||||||||

| Aksan, Kochanska and Ortmann. (2006) (78) USA |

Mutually responsive orientation (MRO). MRO is a positive, responsive, mutually binding, and cooperative interaction between the parent and the infant | 17 | Parent(s)-infant ratings (17 items in total): 1. Coordinated routines (2) 2. Harmonious communication (4) 3. Mutual cooperation (5) 4. Emotional ambiance (6) |

5-point rating scale (ranging from 1 to 5). With higher values indicating higher MRO. Total score ranges from 17 to 85. The study authors proposed four basic components of MRO in parent–child dyads: coordinated routines, harmonious communication, mutual cooperation, and emotional ambiance. |

Home sessions or laboratory sessions, lasting 1.5–2h. Videotaped recordings are coded by trained coders. The tasks include: leisurely chore-oriented and care-giving activities, such as preparing and having a snack with the baby, free play, playing with toys, bathing and dressing the child, opening a gift together. |

7–15 months | Dyad only | Measure development was informed by previous research on MRO of the parent and infant as individuals (Kochanska, 1997) (79), the current measure was designed with the aim of designing codes that explicitly captured the quality of the parent–child interaction at the dyadic level (Aksan, Kochanska & Ortmann, 2006) (78). Study sample consisted of 102 two-parent families with normally developing infants at 7 months and then 15 months old. Socioeconomic status and ethnicity reported (White Hispanic, African American, Asian Pacific Islander or other). Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: No training requirements detailed in Aksan, Kochanska and Ortmann (2006) (78) and no training courses available online. Access: manual, training courses or scale could not be located online or in Aksan, Kochanska and Ortmann (2006) (78) to use this measure. |

|

| 17 | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scales (NCATS) | |||||||||

| Barnard (1978) (80) (Information taken from Byrne &Keefe, 2003; Gross et al., 1993) (81, 82) USA |

Assesses the quality of the parent–child relationship, with a focus on parent–child reciprocity and mutual adaptation. | 73 | Parent scales (50 items in total): 1. Sensitivity to cues (11) 2. Response to the child’s distress (11) 3. Social-emotional growth fostering (11) 4. Cognitive growth fostering behaviour (17) Infant scales (23 items in total): 5. Clarity of cues (10) 6. Responsiveness to the mother (13) |

Each item is rated “yes or “no” for presence of or absence of behaviours demonstrated. (Yes answers receive a value of 1, and No answers are scored 0). Scores are summed for the six subscales to give a total score based on all items. Total score ranges from 0 to 73. |

Suitable for both home and laboratory settings. Procedure lasts 30–45 min, whilst the parent and infant complete two structured tasks, during which the parent teaches the infant. Can be completed live or videotaped recordings scored later. |

0–36 months | Parent and infant only | Measure development is based on literature in the areas of attachment, psychobiology and developmental psychology. The NCATS was developed through research within the Nursing Child Assessment Project. The NCATS is used during observation of the parent introducing a new skill that the infant has yet to demonstrate but is developmentally ready for (Gross et al., 1993) (82). The study sample consisted of 128 mothers and their 24- to 36-month-old children, mothers all had a clinical diagnosis of depression, socioeconomic status and ethnicity reported: African-American, Hispanic and Asian women (Gross et al., 1993) (82). As well as, a sample of 171 parent–child dyads, Hispanic ethnicity of low income backgrounds, the infants ranged in age from 5 to 36 months (Byrne and Keefe, 2003) (81). Clinical and non-clinical samples. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: A structured 2.5-day training course is offered by certified instructors. Each learner must purchase the NCATS manual and pass a reliability test at 0.85 for clinical use or 0.90 for research use. Access: This training is outlined in Byrne and Keefe (2003) (81); however, access to training courses, scale and manual could not be located online. |

|

| 18 | Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA) | |||||||||

| Clark (1999) (83) USA |

Assesses quality of affect and behaviour, or tone of the parent–infant relationship. | 65 | Parent scales (29 items in total): 1. Positive affective involvement and verbalisation (*) 2. Negative affect and behaviour 3. Intrusiveness, insensitivity, inconsistency Infant scales (28 items in total): 4. Positive affect, communicative and social skills 5. Quality of play, interest and attentional skills 6. Dysregulation and irritability Dyad scales (8 items in total): 7. Mutuality and reciprocity 8. Disorganisation and tension *exact distribution of items within subscales unknown. |

5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5). 1–2 = area of concern, 3 = area of some concern, 4–5 = area of strength. Total score ranging from 65 to 325. All items are rated so that high scores indicate more positive parent–infant interactions. Raters focus on rating 8 to 10 of the variables at a time for each pass through (a total of seven to nine viewings of the entire 5-min videotaped interactions). |

Measure consists of 5 min of parent and infant interactions, including a structured task, a feeding observation and free play. Videotaped. Designed to be completed in both clinical and research settings. |

0–5 years | Infant, parent and dyad | Measure was originally developed for use with psychiatrically ill mothers and their infants. Developed to assess and describe the patterns of interaction and to focus early intervention efforts at improving parenting skills and the quality of the relationship (Clark, 1999) (83). Now designed to assess interaction quality in mothers with and without a history of psychiatric disorders. Sample size consisted of 359 mothers and their infants aged 10–14 months. Socioeconomic status (household income and education) reported. Ethnicity reported as White, African-American, Native American and Asian American. Clinical and non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Unknown. Training: Unknown. Access: manual, training courses, or scale could not be located online to use this measure or reported in paper (Clark, 1999) (83). |

|

| 19 | Parent Infant Interaction Observation Scale (PIIOS) | |||||||||

| Svanberg, Barlow and Tigbe (2013) (50) UK |

Parental sensitivity and responsiveness, with the aim to identify families at high risk of parent–infant interaction problems | 16 | Interactional constructs of scale (16 items in total): 1. Eye contact and face-to-face placement (1) 2. Vocalisations (1) 3. Affective engagement and synchrony (1) 4. Warmth and mutual affection (1) 5. Holding and handling (1) 6. Verbal commenting about baby (1) 7. Attunement to distress (1) 8. Bodily intrusiveness (1) 9. Age appropriateness of chosen activity (1) 10. Expressed expectations about the baby (1) 11. Mind-mindedness (1) 12. Empathic understanding (1) 13. Responsive turn taking (1) 14. Gaze (1) 15. ‘Looming in’ (1) 16. Baby’s self‐soothing strategies (1) |

3-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 4). (0 = sensitively responsive/no concern, 2 = some problems or 4 = extensive problems/considerable concern). Total score ranging from 0 to 64. The three interactional patterns of behaviour: - Sensitive responsivity. - Intrusive and over-engaged. - Unresponsive un-engaged. |

Recorded observation of the parent–infant interaction over a 3- to 4-min period. Suitable for home, clinical or laboratory conditions. Videotaped recordings are then analysed by trained coders. |

6 weeks -7 months Time limited infant age range of only around a 5-month period. |

Dyad | The PIIOS was designed to be implemented as part of the English Healthy Child Programme and includes a number of constructs based on the CARE-Index (Crittenden, 1988) (27) so the measure is informed by attachment research. The measure also contains constructs based on research around the importance of ‘mind-mindedness’ (Meins et al., 2003) (84) in which the parent exhibits an ability to interpret and verbalise the infant’s thoughts or motivations, this has also been suggested to predict infant attachment security (Meins et al., 2001) (85). Measure was designed to identify families at low, medium and high risk of parent–infant interaction difficulties (Svanberg, Barlow and Tigbe, 2013) (50). Study sample consisted of 14 videotaped recordings of parent–infant dyads. No details on socioeconomic status, ethnicity of infant ages given. Non-clinical sample. |

Costs: Scale not free to access. Training/manual/scale costs £450. Training: Online or in-person 3-day training course, plus access to manual/scale and supervision. Access: Training, the manual and scale can be accessed through the following website: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/study/cpd/cpd/piios/#:~:text=PIIOS%20training%20is%20usually%20delivered,intrusive%20and%20over%2Dengaged |

|

| 20 | Parent–Infant Interaction Scale (PIIS) | |||||||||

| Clark and Seifer (1985) (28) USA |

Interaction style in parent–infant dyads, including parental sensitivity and reciprocity of their interactions. | 10 | Parent scales (7 items in total): 1. Acknowledging (1) 2. Imitating (1) 3. Expanding/Elaborating (1) 4. Parent direction of gaze (1) 5. Parent affect (1) 6. Forcing (1) 7. Overriding (1) Infant scales (2 items in total): 8. Child social referencing (1) 9. Child gaze aversion (1) Dyadic scales (1 item in total): 10. Dyadic reciprocity (1) |