Abstract

The primary purpose of public mental health is to promote wellbeing. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) have found that it is crucial to engage community to improve wellbeing and to support persons at times of stress. The United States Surgeon General has reported on significant debilitation caused by an epidemic of loneliness, contributed to by the loss of social connections through fewer and less vibrant social infrastructures. WHO, SAMHSA and the Surgeon General recognize that spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) are prevalent social infrastructures, dispersed geographically, as well as found across diverse economic, ethnic, immigrant, well-served and underserved communities. Because of their prevalence and social connectedness, what role could SFBOs play to improve social cohesion and individual wellbeing, increase community support, reduce dysfunction and sustain recovery? How could mental health service organizations (MHSOs) engage SFBOs in collaborative care? This paper will review evidence that supports the role of religion and spirituality (R/S) to both promote wellbeing, as well as to respond to stressors in ways that can both prevent the onset of mental disorders and support recovery after clinical treatment. We also review negative attributes of R/S that can be the source of trauma and also impede access to mental health care. We provide a framework for Community Outreach & Professional Engagement (COPE) to guide collaborations that originate in MHSOs and reach out to SFBOs to build relationships that can become partnerships. Key principles of COPE are to recognize that community and clinic are separate domains, that clergy have both religious and cultural expertise pertinent to wellbeing and social support, and that clinicians have expertise pertinent to assessment and treatment for dysfunction. COPE is a framework to bridge these separate domains in order to facilitate community-engaged collaborative care, which is clinically crucial for persons with more severe mental illness or substance abuse to sustain their recovery. We provide case examples of the COPE categories of collaboration, and include recommendations for future research in the context of outcomes for public mental health.

1 Introduction

The primary purpose of public mental health is to promote wellbeing (1–3). Both the World Health Organization (WHO) through its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – as well as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) through its categories of wellness (4, 5) – have articulated attributes of wellbeing. The WHO and SAMHSA’s wellbeing attributes emphasize social belonging, emotional connectedness, intellectual pursuits and spiritual meaning, along with health, financial stability, and justice. WHO, SAMHSA, and diverse public health and clinician-researchers (6–19), all advocate that in order to promote wellbeing and support, as well as clinical treatment and sustained recovery, mental health systems require partnerships with community infrastructures (i.e. organizations that facilitate social connectedness and support) (5, 20–24).

One robust path to achieve these collaborations is to cultivate partnerships between mental health service organizations (MHSOs) and spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) (23, 25–29). Since its inception, the WHO has promoted the utility of partnerships between MHSOs and SFBOs (22, 30). In this paper we review evidence that supports the role of religion and spirituality (R/S) to promote wellbeing, as well as respond to stressors in ways that can both prevent the onset of mental disorders and support recovery after clinical treatment (31). We also review negative attributes of R/S that can be the source of trauma and also impede access to mental health care and sustained recovery (32).

Religion and spirituality (R/S) are core domains of identity and psychosocial functioning for most persons (33, 34). A compelling evidence base highlights the role of R/S in preventing the onset of mental ill health and disorders as well as providing resources for recovery and growth when such conditions occur (33, 35). Advances in translational research from university to community affirm the value of assessing peoples’ R/S and – when relevant – including these beliefs, practices, and relationships in psychotherapeutic interventions (35), which include those negative R/S experiences that can be sources of trauma (32).

The salience of a focus on community collaboration is also supported by data that demonstrate that religious practice in a religious community is most predictive of positive health outcomes (33, 35). For example, one study explicitly compared personal vs. communal (congregation-affiliated) religiosity, and observed that personal religiosity alone was not protective: greater personal religiosity – at a low level of communal religiosity – led to negative religious coping, which was significantly associated with grief severity (36).

Consistent with current clinical emphases on whole-health and person-centred care, asking about persons’ R/S can tailor evidence-informed prevention and clinical interventions so as to enter into dialogue with each person’s potent beliefs, values, practices, and relationships. However, these public mental health resources are frequently overlooked by MHSOs, with the result that – even when salient – it is uncommon for MHSOs to enact evidence-informed assessment and integration of R/S in treatment. This is not surprising as mental health providers infrequently receive training in the clinical applications of R/S (37, 38). Therefore, a core ethical challenge for MHSOs, is to establish training and systems of intervention that are capable of attending to needs of persons across the wide variety of their lifespan religious practices and beliefs, as well as persons with no beliefs or practices of a spiritual nature, and persons for whom religion is a source of harm (23).

We present a framework (Figure 1) of Community Outreach & Professional Engagement (COPE) that maps how to collaborate and bridge the resources and goals of communities and clinics to promote wellbeing, prevent dysfunction, provide treatment and sustain recovery (23, 28, 37, 39–46). In turn, we describe examples of COPE in community settings. We conclude with suggestions for future designs of outcomes research for these initiatives. We hope to offer an actionable guide for mental health clinicians and researchers – as well as clergy and lay leaders – to build sustainable and reciprocally beneficial partnerships between MHSOs and the SFBOs in their communities.

Figure 1

COPE: Framework for collaboration between community care & clinical treatment.

2 Assessment of policy/guidelines options and implications

2.1 An epidemic of loneliness

Recently, the United States Surgeon General has reported on the significant debilitation of wellbeing caused by an epidemic of loneliness (5). Contributing to this malaise is the loss of social connections from ever fewer and less vibrant social infrastructures in our communities (47–49). The Surgeon General also notes that spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) remain prevalent, and are de facto community resources that may ameliorate loneliness and improve wellbeing. However, these prevalent community resources, are frequently overlooked by clinical practitioners and researchers (5).

2.2 Spiritual/faith-based organizations as public mental health resources

The idea of SFBOs as de facto public mental health resources is not new. In “The Churches and Mental Illness” (50), written in 1962 for the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health, Richard McCann describes examples of wellbeing, promoted by SFBOs through de facto primary prevention:

The “primary level” of prevention, while a profoundly complicated matter, would see the clergy facilitating the maximum contribution of religion to the growth of whole, mature persons – creative, adventuresome, able to give and receive love fully, with long-range orientations and aspirations [emphasis added] (p, 239).

Spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) are naturally-occurring social infrastructures and conduits of prevention and recovery in communities. Religious communities and their leaders are part of the network of community providers who help both promote wellbeing and prevent illness, in well-resourced as well as in underserved communities (2, 29, 30, 51). Persons from under-represented ethnic groups who often contend with other social determinants of poor health (e.g. systemic racism, poverty) (52, 53), as well as older persons – who often have higher disease burdens and poorer health outcomes – tend to be more likely to participate in community SFBOs activities as well as seek help and counsel there (54, 55). Immigrants are also a group in which many people adhere to strong religious beliefs and practices (56–59), and for whom mental health care is often both hard to access and avoided due to stigma (60–62). Therefore, SFBOs have the potential to provide much-needed extra support for all these groups; a useful resource in the drive to “level-up” and improve mental health indices in disadvantaged populations (2, 21, 28, 30, 63, 64). In turn, collaboration between MHSOs and SFBOs could strengthen the range and duration of the support that each offer (18, 52, 53).

2.3 Public mental health and religion: structural & cultural bridges

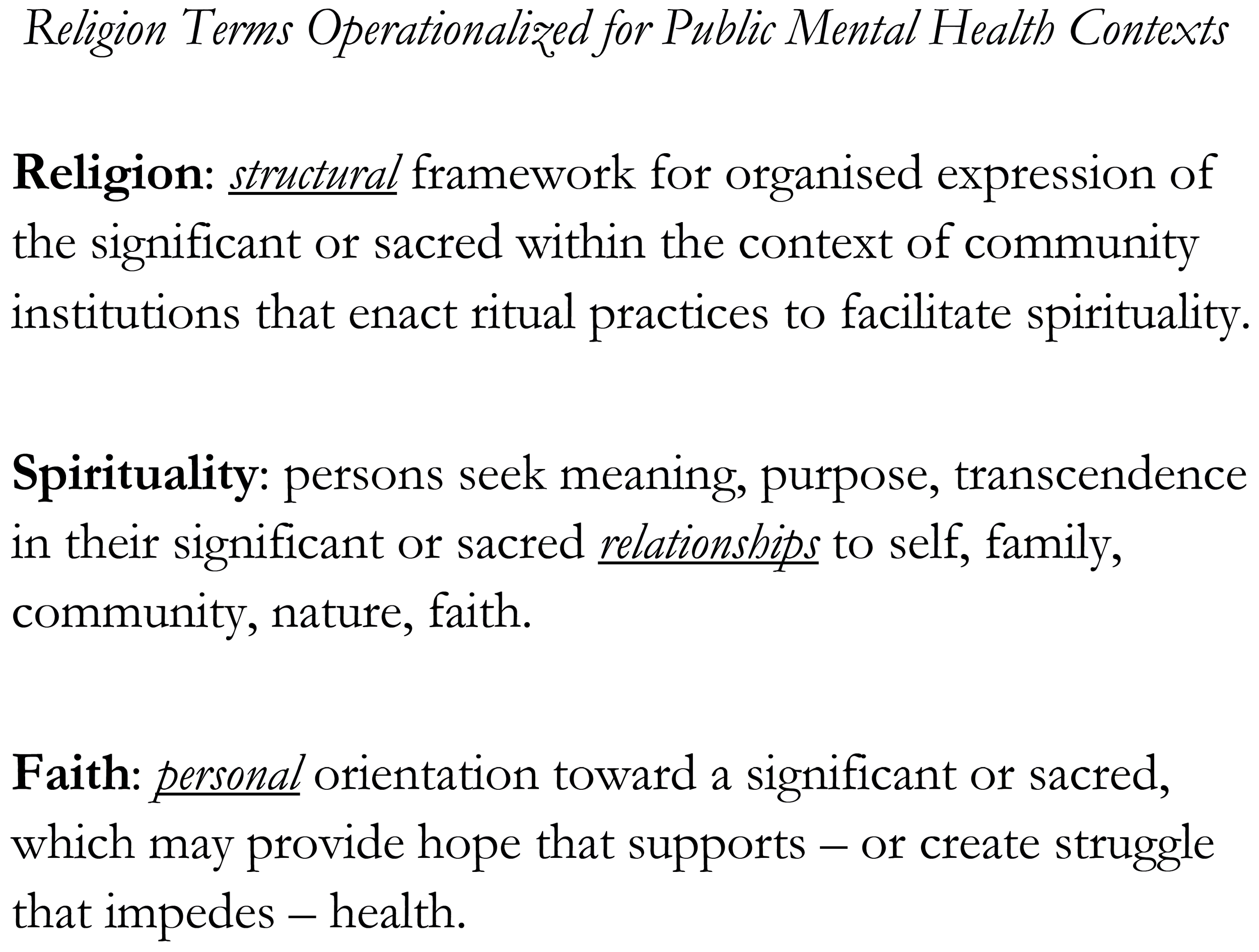

Religions across the world share two attributes that can organize efforts to bridge community and clinic (Figure 1): (1) Religions are structural: they have buildings in locations where followers gather; (2) Religions are cultural and spiritual: their beliefs, rituals and prayers are as varied as the languages of humanity (65–68). The terms Religion, Spirituality and Faith are operationalized for public mental health contexts in Figure 2 (69–72).

To initiate dialogue with SFBOs, an MHSO will first need to physically locate SFBOs structures. Congregations vary greatly in size and accessibility. Persons from MHSOs who reach out to SFBOs, will also need to learn and respond to the varied cultural beliefs and practices of different denominations, which will guide priorities for how MHSO representatives will interact with the larger community (21, 23).

A core ethic of COPE is the empirical understanding that, religion is real: it is present across humanity and influences both emotions and behaviours (73). This is distinct from any conversation about whether any one religion (or denomination) may be true: that refers to an individual’s or community’s own spiritual path toward specific beliefs of transcendence (Figure 2). With this understanding that religion is real, even MHSO clinicians and SFBO clergy and congregants who have divergent worldviews can nevertheless collaborate to reduce the pain caused to individuals and families by mental illnesses and substance abuse.

Figure 2

Religion terms operationalized for public mental health contexts.

2.3.1 Structural bridges: religions construct buildings

The robust public mental health opportunities that are possible when we facilitate sustained interactions of MHSOs and SFBOs are to be expected when one considers that – in addition to untold numbers of unaffiliated spiritual communities – research has identified 356,642 SFBOs across the United States (74). As examples of SFBOs’ prevalence by population densities: Arkansas – with the highest – has an SFBO for every 405 people in the state, and even Nevada – with the lowest – has an SFBO for every 2,016 people. From a community integration and access perspective, no other single category of social infrastructure has so much reach into such a variety of communities, or is present for individuals across their lifespans from infancy to old age. SFBOs are rooted in a variety of communities: those with numerous resources, as well as those with few resources and poor access to care. Clergy and other faith leaders are frequently called on to assist with the material sustenance of the congregants in their communities. SFBOs also frequently assist persons in the community who are not affiliated with their congregation. Particularly in underserved and highly religious locales, SFBOs fill gaps and expand resources for housing, food, counselling, and other supports, which mitigate multiple social determinants of poor mental health (75).

2.3.1.1 Public mental health of attendance

After more than a quarter century of empirical mental health research on the risk and protective factors of religion and spirituality (R/S), rigorous studies have found that attendance at religious services has consistently predicted positive mental health outcomes (33, 34). A recent systematic assessment examined 8,946 empirical research studies of R/S variables in association with serious illness and another 6,274 empirical studies of health outcomes. A multi-stage review determined the highest quality studies with the least evidence of bias. This yielded 441 studies of serious illness and 276 studies of health outcomes. The most consistent and robust findings were the benefits of communal religiousness factors such as religious service attendance on physical, mental and substance use outcomes (35).

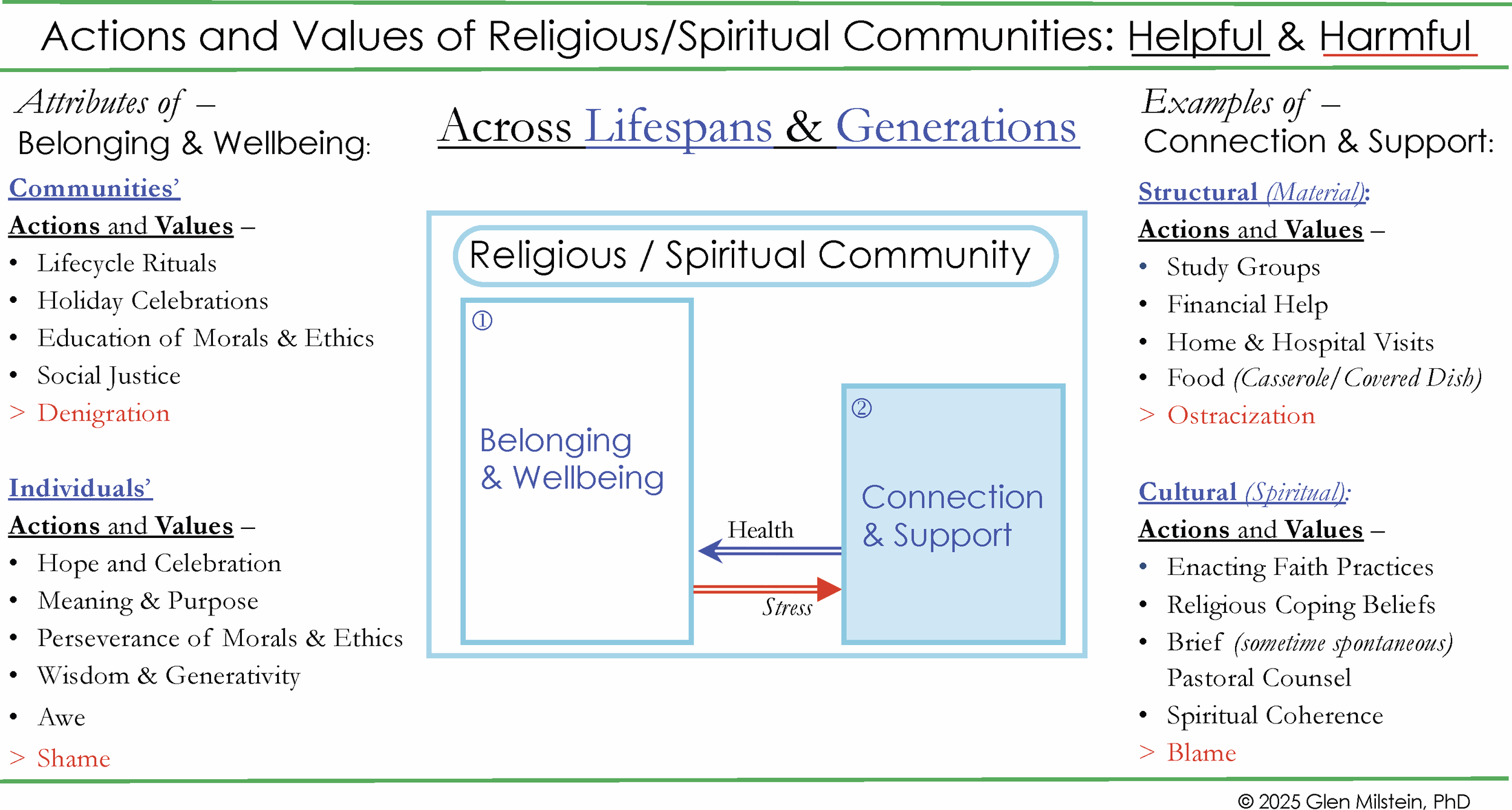

The psychological attributes of attendance likely involve many distinct motivations and ways to experience religious services (50). Congregations invite people to become part of a community; they are spaces where congregants might enact personal and communal prayer; where there is learning and teaching. Persons celebrate ceremonial events and lifecycle rituals from birth, through school years to marriage, child-rearing and until death (23, 76–78). Since people go to services for so many reasons, attendance may be the source of widespread benefits exactly because different people benefit in different ways at different stages of life (10, 48). What they do share are the benefits – and possible harm – of attendance in a locatable physical space (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Actions and values of religious/spiritual communities: helpful & harmful.

2.3.1.2 SFBOs are locatable

In order for MHSOs to offer care as early and effectively as possible, to target prevention initiatives at developmentally sensitive periods, and to sustain recovery via community, collaboration will necessitate locating capable and caring partners (1). Religious congregations and other SFBOs are usually housed in physical spaces, and as noted, there are over 300,000 SFBOs’ doors to knock on. Twenty-first century web-based technology makes it easy to create maps of the locations of SFBOs near to MHSOs, as well as to record the types of public health resources they provide (food banks, childcare, after-school, housing support, Alcoholic Anonymous meetings…). Details for the use of a free web-based program to map locations and resources is found in Appendix 1. Another structural, public mental health advantage of MHSOs outreach to SFBOs is that this work creates no new infrastructure; it bridges a continuity of collaboration between extant organizations, without necessitating any new building or capital campaigns.

While congregations may facilitate positive social determinants of health, they are not clinics. Rather, clinics (and clinicians in private practice) can provide mental health care through professional assessments and treatments. In turn, religious communities can help persons sustain recovery after treatment (79). To achieve successful outreach to connect community support and clinical treatment (Figure 1), MHSOs also need to understand the cultural views of SFBOs’ and individuals’ R/S as they pertain to care.

2.3.2 Cultural bridges: spirituality and faith

In addition to hundreds of thousands of physical locations, in the United States alone, people belong to 236 religious denominations (74). SFBOs have denominational worldviews and meaning frameworks that are shared among their community members (Figure 3). In turn, these denominational beliefs and values guide R/S practices and relationships among adherents, which can support development of shared purpose, character strengths, and social connections (80). We have emphasised the positive psychological potency of R/S that can be woven into people’s personal spirituality, and serve as a source of hope and strength. It must also be recognised that R/S can produce negative outcomes (Figure 3). In families and communities R/S can devolve into negative judgments that harm persons mental health and wellbeing (81). Research also finds that, in the aftermath of painful transitions, traumas, or morally injurious events, faith can engender strains, tensions, and conflicts, which diminish people’s wellbeing and capacity for resilience (45, 82–86). Some persons’ present-day trauma is imbedded in a developmental history of rejection or other harm from their religious upbringing (32).

At other times, it is a theological vocabulary – in place of a medical vocabulary – that frames how people describe their lived experiences with mental illness (65, 69, 87). In the words of a young man with schizophrenia:

“The biomedical model of mental illness has contributed significantly to our understanding of major mental illness, but little to true recovery. While medications may help one’s behavior become more acceptable to society, they do nothing to put one’s shattered soul back together.” (88, p 25).

This person describes the disruptions and pain of schizophrenia in two ways. First, he describes the disruptions his illness causes between himself and others. Second, he describes how his illness interferes with his connection to himself and to an ineffable transcendent: as he says, to his soul (Figure 2).

In another example, a mother whose son has schizophrenia, was asked if she thought his illness would ever be cured, she responded,

Si Dios hace la obra, él se va a sanar, aunque los doctores digan que él va a ser así siempre (89). [If God performs the deed, he will get well, even though the doctors say he will always be like this.]

For many religious persons, the belief in the possibility of a cure is an expression of their faith in the healing power of a deity, and also their spiritual motivation to provide care (Figure 2).

Therefore, to treat the whole person, any intervention that seeks to restore mental health and sustain recovery must also assess and possibly integrate resources, which – for most people – will include some combinations of religion, spirituality, faith and ritual practices (Figure 2). It is the disregard of R/S, on the part of mental health professionals, that may interfere with persons’ paths to wellbeing. As such, clinicians need to cultivate religion and spirituality (R/S) competencies (awareness, knowledge, and skills) to assess, discuss, and address religious or spiritual concerns with their patients, and to work therapeutically in response to these positive or negative experiences of R/S across individuals’ lifespans (38, 90).

3 Actionable recommendations

3.1 COPE: Community Outreach & Professional Engagement – a framework to bridge public mental health services with religious organizations

We built on lessons learned from previous generations (50, 91–94) to develop a collaborative public mental health framework to offer actionable strategies for the delivery of culturally competent care, through pathways of reciprocally beneficial partnerships between mental health service organizations (MHSOs) and spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs). Community Outreach & Professional Engagement (COPE) is the result of decades of work with religion and spirituality (R/S) across a breadth of public mental health settings (21, 23, 28, 37–43, 45, 46, 80, 89, 95–110). In collaboration with experts in public health, systems science, clinical care, and theology, as well as with chaplains, community clergy, people with lived experiences of mental disorders and their families, we developed the adaptive COPE program to bridge community care and clinical treatment (Figure 1). COPE first acknowledges borders between persons’ community and their clinical treatment, and then builds programs that bridge clinical services of MHSOs with local resources of SFBOs in order to: a) strengthen wellbeing through community resilience; b) enhance access and effectiveness of clinical treatment; c) generate a continuum of collaborative care across MHSOs and SFBOs to sustain recovery and renew wellbeing (21, 39, 40, 111).

3.2 COPE has three core principles

-

Clergy and Religious Communities: have specific expert knowledge about religion & culture.

-

Clinicians and Research Scientists: have specific expert knowledge about assessment & treatment.

-

Professional Collaboration: can reduce burdens of SFBOs and MHSOs – and help more persons – through a continuum of wellbeing, support, treatment and recovery.

3.3 COPE has two implementation strategies: inreach and outreach

3.3.1 Inreach

Works within an MHSO to first gauge the interest of administrators, clinicians, staff, and those who receive services, to include R/S as part of care. As a next step, an internal evaluation is often needed to determine how much the clinic’s staff demonstrates basic awareness, knowledge, and skills necessary to attend to the spiritual or religious aspects of clients’ lives (i.e., spiritual and religious competencies) and to determine whether the MHSO’s prevention and treatment programs sufficiently address this cultural domain (38, 104, 112).

For example, Inreach has identified the need to train clinicians and other staff in R/S competence and to include terms in the intake questionnaire which identify clients who prefer a spiritually responsive approach to their treatment (including collaboration with clergy or other faith leaders). COPE will guide supervisors and administrators to dedicate resources to ensure that clients and community members receive spiritually competent assessment and services from the MHSO. Even persons who report that they are not religious or spiritual may have been raised in a religion that had a negative effect on their current mental health. Therefore, a lifespan assessment of R/S is necessary, as earlier religious traumas may need to be a focus of persons’ clinical treatment (23, 105, 113).

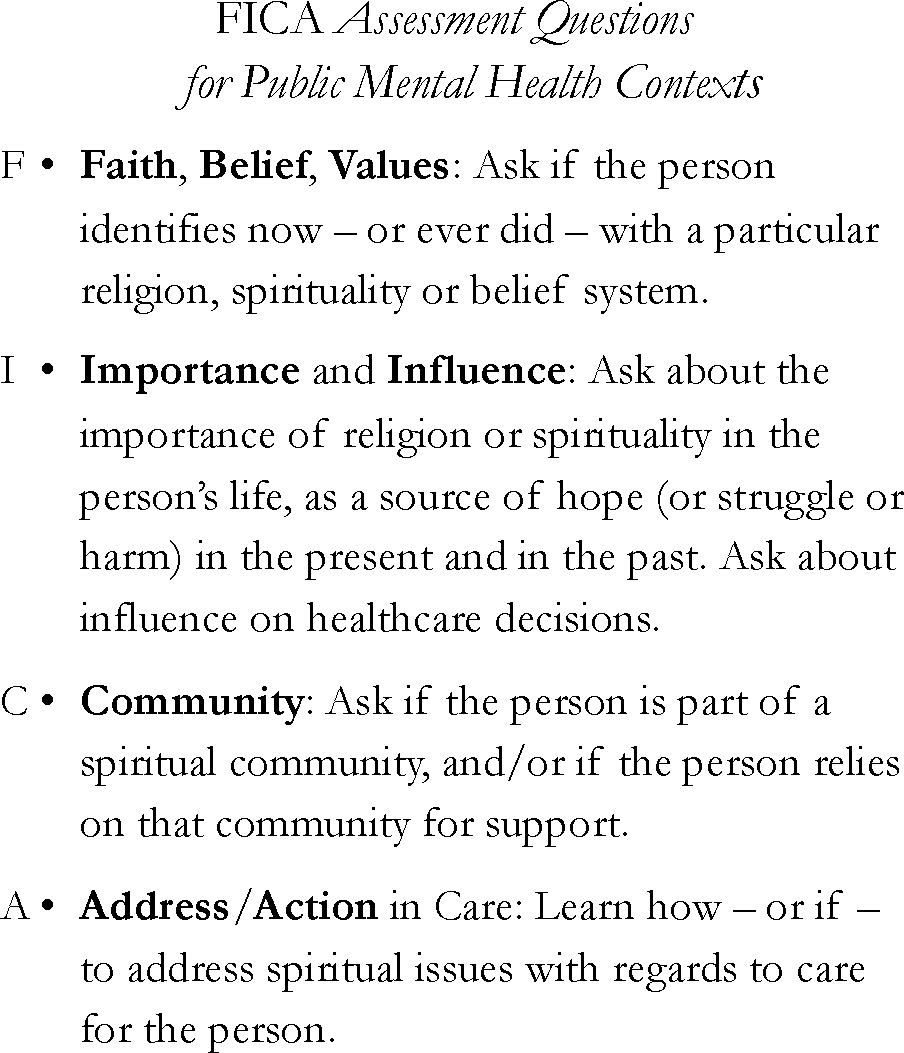

An example of a clinical assessment with demonstrated utility is the four-part FICA (Faith, Importance, Community, Action) (70, 114) (Figure 4). The FICA guides medical providers to facilitate conversations through open-ended questions about their patients’ R/S concerns and needs. Research has supported the acceptability, feasibility, and validity of the FICA with both patients and physicians, irrespective of the clinicians’ own R/S (115, 116). The FICA is a tool that facilitates assessment of persons’ experiences of their religious faith and spirituality – both positive and negative. It is therefore a useful guide to both individual clinical treatment, as well as to community engagement of collaborative partnerships. Other assessments are also available (28, 117–119). In Figure 4, we adapt the FICA assessment for public mental health contexts.

Figure 4

Assessment questions.

One psychotherapy training – that we have used with clinics – is the online program, Spiritual Competency Training in Mental Health” (SCT-MH) (120, 121). The eight-module program has demonstrated support for the effectiveness of promoting facets of foundational competence for addressing clients’ religion and spirituality (R/S) in mental health practice (112). The breadth of training modules includes instruction to, “Distinguish between: Helpful & Harmful Spirituality”, as well as to both “Mobilize Spiritual Resources” and “Address Spiritual Problems.” One key is to demonstrate cultural humility with persons who receive clinical care and say, “I don’t know about your faith (spirituality…). I am curious to learn from you how it helps you, or how it might cause difficulties” (122). As clergy are often concerned about how clinicians will attend to peoples’ spiritual and religious identities, this dedication to train R/S competence for clinicians is also reassuring to clergy when they consider making a referral to a MHSO. In addition, work with administrators in MHSOs also revealed the possibility to track referrals from SFBOs in the Electronic Health Record to identify possible community partners and also track the success of the COPE-based initiatives for referrals from SFBOs (28).

3.3.2 Outreach

Persons from MHSOs contact SFBOs to inquire about unmet mental health needs and to initiate exploratory dialogue with MHSOs. When SFBOs have an interest, this process ideally leads to co-creating bidirectional educational presentations. Outreach and dialogues can nurture familiarity that allow for referrals. In turn, this can build trust and long-term partnerships and collaborations. We have learned that MHSOs need to designate a person to lead these outreach efforts. They are the bridge builders. Frequently they are persons with both clinical and pastoral training, and often have certification in both areas. This allows one MHSO to reach out to many SFBOs, regardless of denomination, often guided by persons who receive services. Webinars that describe these programs are found in Appendix 2. Appendix 3 provides a selection of online resources.

An example is when MHSOs teach Mental Health First Aid (123) courses in SFBOs, which help congregations support those members facing mental health stressors. At the same time, clergy demonstrate to clinicians the de facto care provided outside of the clinic, allowing those who return to the community from clinical treatment to have more support for sustained recovery from within the community. With this bridge of collaboration, there is burden reduced on both clinicians and clergy. There is burden reduction for clergy who know they can make a referral for a member of the congregation. There is burden reduction for clinicians when they know that there is a participant community to provide a “solid welcome” to their patient, to sustain the hard-won recovery (28, 42). To guide these initiatives and demonstrate the interdependence and opportunities for prevention, treatment and sustained recovery we developed the COPE framework.

3.4 COPE bridges community care with clinical treatment and maps collaborative flows

COPE: Community Outreach & Professional Engagement (Figure 1) diagrams the dynamic flows of relationships between SFBOs in community contexts and MHSOs in clinical contexts (13, 15, 124–126). Figure 1 is a snapshot of the epidemiology of mental health in a society. The reducing sizes of the rectangles represent the smaller number of persons who pertain to the category. This is to be expected as the increased shading represents increased dysfunction caused by more debilitating forms of mental disorder and substance abuse (8, 14, 79).

The larger, Community rectangle encompasses two categories. The first category is how most people spend most of their time: (1) Here we experience Belonging – to a community, to a family, to a home (127). This generates Wellbeing (10, 117, 128–133). Next is: (2) Connection to community, which offers us hope and Support in times of stress (134).

The smaller, Clinic rectangle, encompasses the next two, more-shaded rectangles. These show the place(s) for persons who need to receive clinical treatment(s) in response to dysfunction. For most persons, this is: (3) Outpatient Treatment. Some persons require: (4) Intensive (or Inpatient) Treatment for their severe or chronic mental illness or substance abuse.

The greatest challenge for persons with chronic mental disorders and chronic substance abuse is to sustain recovery. As noted in rectangle (5) Community-Engaged Collaborative Care: it is when persons can avail themselves of both Community and Clinic that that they can best Sustain Recovery.

Some religions’ stigma about the veracity of mental illness makes it a challenge for people to be willing to seek clinical treatment. In turn, few clinical treatments guide clinicians on how to return people to community connections that provide support and belonging (135, 136). The COPE framework identifies the work required to create programs that will bridge persons sustained movement between community and clinic. This work requires MHSOs to support their staff who work as community outreach bridge builders as they seek partnerships with community SFBOs.

COPE maps two directions of flows. The red arrows that flow from left to right demonstrate worsening conditions that devolve into three flows of: Stress, Dysfunction, and Severity/Chronicity. However, most stress occurs and – ideally – is resolved in our homes and communities. We experience Stress, which leads us to seek Community Support. We then experience our Health Flow, with a return to Wellbeing and no need for clinical treatment.

It becomes necessary to crossover beyond our Community to receive Clinical Treatment when our difficulties flow (or may flow) to Dysfunction (2, 137). Preferably, we have access to care and can receive outpatient treatment to resolve our dysfunction. The Severity/Chronicity flow of some mental illnesses and some substance abuse may require Intensive or even Inpatient Treatment. There can be fruitful collaboration in these settings between clinicians and hospital chaplains (100, 138). The goal for COPE is to engage as many settings and stakeholders to work together as possible. The blue arrows, flowing from right to left, represent improved conditions cultivated by clinical interventions and community supports, which can evolve into flows of: Reintegration, Recovery, and Health. Recovery and wellbeing will best be sustained by community-engaged collaborative care.

3.5 Bereavement pathways mapped by COPE

The universal human experience of loss is frequently the cause of profound stress (139, 140). Human bereavement provides robust paradigms to elucidate the dynamic flows of the continuities of care mapped by COPE. Figure 3 is a diagram of the first two categories of COPE: Belonging and Connection, which in turn provide Wellbeing and Support. These are found in communities, not clinics.

Figure 3 illustrates the normative flows of the vast majority of persons in response to grief (139, 141). Here we see how roots in a community provide a sense of Belonging through shared actions and values across lifespans (and generations), which support and affirm Wellbeing. When people lose someone close to them, many reach out to their faith leaders and communities for material, emotional, and spiritual support (142). In response to this Stress Flow, faith leaders and fellow congregants of SFBOs may offer the structural (material) Support such as, visits, financial help and even prepared meals. They may also offer the cultural (spiritual) Support to enact mourning rituals, which may help to re-establish connection, intelligibility, and belonging (141). For most persons these rituals are practiced from their youth to their old age and provide a spiritual coherence that can engage hope (23, 143–145). In most bereavement situations – through a period of mourning – these supports can return persons to Wellbeing without any involvement of clinicians: the Health Flow. A crucial caveat is that grieving can also be a time when the negative attributes of religion can energise judgments of shame and blame from family or community or within oneself, leading to spiritual incoherence and worsened mental health (32).

Returning to the full COPE diagram in Figure 1, some persons’ bereavement might instead lead to persistent distress or Dysfunction Flow that warrants clinical care. In those cases, family, friends, or clergy could recognize these warning signs and refer the person to a trusted clinic or provider. In turn, this Outpatient Treatment will ideally promote a Recovery Flow that returns people to Support and Wellbeing in their communities. However, some people require more assistance in their recovery journey. In particular, we have learned that those who are typically most in need of Intensive clinical care often have complex histories of trauma over the life span, possibly with addiction, and other issues. In such cases, persons’ Severity/Chronicity Flow may pose harm to themselves or others and lead to needed Intensive (or Inpatient) Treatment. When persons are discharged, Figure 1 illustrates how Community Engaged Collaborative Care enacted across people receiving services as well as their clinicians, peers, families, and faith leaders can then limit social isolation to engage hope, promote moral agency, facilitate Reintegration Flow, sustain Recovery Flow and a Health Flow that returns to Wellbeing and Sustained Recovery (146).

3.6 COPE: case studies1

The COPE framework has been adopted in multiple locations, and informed work at others. Here, we share three initiatives with clinical case examples. Two programs were built based on COPE, the third built their program independently while working collaboratively with our team. In our work, we consistently see that SFBOs have frequent experiences with mental health and substance problems among their congregants, and equally evident is that MHSOs know the importance of R/S among the people they serve. What SFBOs and MHSOs need is a bridge to bring them together (Figure 1). Below are three examples.

3.6.1 Denver, Colorado

The Director of Clinical Services at a comprehensive mental health center in Denver, CO reached out to the first author in order to best respond to interest from her staff on how to address the R/S concerns of the persons under care in their clinics. A survey of the staff and those receiving services quantified the significant interest in R/S as an aspect of care. Using an earlier version of the COPE framework (21), they worked with their new Director of Faith and Spiritual Wellness (DFSW) to launch the program. The DFSW was trained both as a minister and in mental health. Inreach and Outreach programming was developed. For Inreach programs, the clinic staff was guided to add R/S questions to both the intake and treatment plan forms; discussion groups were held to study the varieties of religious experiences of both the staff members, and the people receiving care at the clinic. The DFSW reached out to local congregations in the community that had demonstrated interest in how to use mental health resources in the care of persons in their communities. This bridge had immediate results: from congregations, the DFSW received requests for training on mental health issues and interventions, which led to providing regular programming in congregations on mental health first aid. The clinic also started a peer-support spirituality group. More bridges were built between the Denver clinic and the congregations: the clinic organized a half-day seminar to bring together clergy, clinicians and consumers. The heart of the program was a panel led by persons in treatment for mental illness. Each speaker was accompanied by both one’s therapist and one’s clergy. The speakers spoke about their struggles to bring these two resources of their life to become complementary. Their therapists said that since R/S inquiry was not part of their training, it had not been part of their therapy work, until these clients brought it up. Their clergy spoke of how their early views were that persons did not need mental health care, they needed to pray harder, until these parishioners confirmed a need for both R/S and clinical care to have shared presence in their lives. A review of feedback from the conference demonstrated that both clergy and clinicians in attendance viewed the COPE framework as a way to guide access to the others’ expertise; furthermore, persons of different traditions were open to receive care inclusive of religious resources. Most people felt the COPE framework delivered at the seminar not only bridged the distance between local clergy and mental health professionals, it had given all a common language with which to explore their shared interests (28).

3.6.2 Mobile, Alabama

For three years we implemented COPE in the Vets Recover (VRR) clinic in Mobile, Alabama, which specializes in serving veterans, first responders and their families. VRR has Inpatient, Outpatient, Peer-Support and Community Integration services. The COPE Coordinator (CC) – working for Community Integration – was part of Inreach training of clinicians and led an extensive outreach program with presentations to churches that have included Mental Health First Aid, Trauma Informed Care, Black Men and Mental Health and presentations on the Bible and Wellbeing. The CC is both an ordained pastor and certified counsellor (and third author). The CC also worked with local ministries who serve unhoused people. One man served by the ministry worked with the CC, and the man requested a referral to the outpatient clinic. Through the therapy the person worked to stop substance use, to return to his vocation as a welder and to become a member of a local congregation. The CC reports that the way to build the necessary trust for healing with this person, was to approach the man with sensitivities steeped in ethnicity and religiosity. It was crucial to the man that his religion be respected, and as the clinic had invested in understanding R/S, the man’s care benefited from the connection between his faith, his clergy and his mental health caregiver that the CC facilitated.

3.6.3 Fort Washington, Pennsylvania

Intersect is a program within Access Services, a comprehensive mental health center. They describe themselves as, “Supporting people at the intersection of faith and mental health.” Intersect has developed an independent program within Access Services. They train across the centre’s programs, do workshops at local congregations and in neighbouring cities. They have also organized a County Multi-Faith Coalition. One example of the flow of how their integrated system works is the case of a man enrolled in their psych rehab program. He took part in a spirituality group developed and led by the Director of Intersect (the fifth author), who is both an ordained pastor and social worker. Through the group the man – who had been estranged from his religion due to earlier trauma – expressed his wish to find a congregation. The Director contacted a minister he knew and the minister met with the man and the Director and then invited the man and his wife to come to services. The couple attended regularly. After some time, the man had a crisis, locked himself in the bathroom and threatened suicide. The wife called the minister. The minister called the Director who – with the minister on the line – called the mobile crisis team who were able to bring the man to treatment. Because the couple were comfortable and familiar with the minister and had never hidden the man’s mental illness, they were also comfortable returning to the social infrastructure of their recently joined church community. Sometime later the man had another crisis and, again, the wife called the minister and this time, the minister called mobile crisis directly. A bridge was built and was travelled across.

3.7 Future outcome research

Looking ahead, strategic and inter-disciplinary research will be needed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of COPE as a guiding framework for mental health service organizations (MHSOs) who seek to partner with religious congregations and other spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) to engage the social infrastructures and determinants of mental health care (147, 148). Researchers might begin by considering these basic questions for varying stakeholders in their communities:

-

What are the mutual (or divergent) interests for collaboration among faith-based members and leaders, mental health care providers, people who receive care, their families, as well as civic leaders?

-

What are the community facilitators and barriers to COPE implementation?

-

What are the most effective strategies for facilitating Outreach and Inreach activities within MHSOs?

-

What are the impacts of COPE implementation on the accessibility and outcomes of clinical care?

By spearheading rigorous research on COPE to address these types of questions, MHSOs can identify resources and develop programs for training and aligning their clinical procedures to engage the role of R/S in the lives of their clientele (Inreach) along with evidence-based strategies for building partnerships with SFBOs in their communities (Outreach). Such efforts could provide the evidence base to support an increase in the number of MHSOs with a commitment to spiritually competent care and collaboration with clergy and faith leaders in ways that could strengthen community resilience, increase access to clinical care, and improve outcomes of clinical care and wellbeing in poorly resourced – as well as well-resourced – communities.

4 Discussion

The primary purpose of public mental health is to promote wellbeing. People are in preventable pain, which is in part due to the loss of social connections brought on by ever fewer and less vibrant social infrastructures (47, 49). WHO and SAMHSA recognize that spiritual/faith-based organizations (SFBOs) are prevalent and locatable social infrastructures that could partner productively with mental health service organizations (MHSOs) to better address mental health distress.

COPE (Community Outreach & Professional Engagement) is a framework that facilitates interaction between MHSOs and SFBOs, and contributes to community wellbeing through collaborative care. This collaborative bridge between MHSOs and SFBOs informs mental health professionals so that – when salient – they may create a more substantive role for religion and spirituality (R/S) in the treatment of those seeking their care. COPE also trains clinicians to assess for how religion could be a negative source of trauma for persons they serve.

COPE guides MHSOs to offer SFBOs training on public mental health responses to mental health needs and how to set up clinical support for clergy facing mental health issues in their congregations. The connection between community care and clinical treatment may benefit clients and congregants directly: SFBOs can help persons find clinical treatment, a public mental health collaboration with SFBOs for persons in recovery from inpatient treatment, may serve as the support system they need as they integrate from intensive clinical care to sustained recovery and wellbeing in community.

Every day, SFBOs can generate hope. Hope that is nurtured through belonging to community, which supports both wellbeing and sustained recovery. COPE is a framework to build bridges of hope between public mental health and religion.

Statements

Author contributions

GM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work has been funded by the Lilly Endowment; National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH 19132; R03 MH64614); The Research Foundation of the City University of New York, PSC-CUNY Research Award Program (# 60256-00 48; 67486-00 55); The Innovating Forward initiative of the Spirituality Mind Body Institute at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Acknowledgments

We first wish to acknowledge the many clergy, clinicians, chaplains, people with lived experience and their families who have engaged with COPE and directed its development. We are also grateful to these people who supported and guided the research and enactment of this work: Bruce Link, Peter Guarnaccia, Elizabeth Midlarsky, Dennis Middel, Larry Sebert, William Salton, Lisa Miller, Ben O’Dell, Jess Fenchel, Lisa Rudolfsson and Leora Liggins. Much of this paper was developed by the first author while on sabbatical at the University of Cambridge as a Visiting Scholar in the Cambridge Interfaith Programme of the Faculty of Divinity and as a Visiting Researcher at Darwin College. In the UK, conversations and collaborations with David Fergusson, Mary Kells, Philip Evans, Gerald Midgley, Fraz Mir and Aileen Walsh informed and expanded this work. Over many years, additional support was provided by the Duke Clergy Health Initiative Writing Group, funded in part by the Rural Church Area of The Duke Endowment and led by Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell. Finally, we thank Andrea Casson who reviewed each page of the manuscript and provided invaluable feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ Appendix 2 has links to three COPE webinars that cover more case examples and also more of the theory behind the COPE framework. Four of this paper’s authors teach in the webinars.

References

1

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders . Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (1994). Available at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2139 (Accessed May 28, 2025).

2

Patel V Saxena S Lund C Thornicroft G Baingana F Bolton P et al . The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. (2018) 392:1553–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

3

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) . Creating a Healthier Life: A Step-By-Step Guide to Wellness. Washington, DC: United States Health and Human Services (2016).

4

Swarbrick M . A wellness approach. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2006) 29:311–4. doi: 10.2975/29.2006.311.314

5

United States’ Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General . Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services (2023).

6

Bourdieu P . The forms of capital. In: RichardsonJG, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn (1986). p. 241–58.

7

Bronfenbrenner U . Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. (1977) 32:513–31. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

8

Bronfenbrenner U . Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development Vol. xxix. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications (2005). 306 p.

9

Erikson EH . Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton & Co, Inc (1950/1963). 445 p.

10

Erikson EH . Ontogeny of ritualization in man. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B Biol Sci. (1966) 251:337–49. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1966.0019

11

Erikson EH Erikson JM . The life cycle completed. Extended/ed. New York: W.W. Norton (1997).

12

Geronimus AT . Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society. United States: Little, Brown (2023).

13

Homer JB Hirsch GB . System dynamics modeling for public health: background and opportunities. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:452–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062059

14

McLeroy KR Bibeau D Steckler A Glanz K . An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. (1988) 15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401

15

Midgley G . Systemic intervention for public health. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:466–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067660

16

Gordon R . An operational classification of disease prevention. In: SteinbergJASilvermanMM, editors. editors. Preventing mental disorders: A research perspective. National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, Maryland (1987). p. 20–6.

17

Kellam SG Van Horn YV . Life course development, community epidemiology, and preventive trials: A scientific structure for prevention research. Am J Community Psychol. (1997) 25:177–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1024610211625

18

Anglin DM Ereshefsky S Klaunig MJ Bridgwater MA Niendam TA Ellman LM et al . From womb to neighborhood: A racial analysis of social determinants of psychosis in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. (2021) 178(7):599–610. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20071091

19

Oman D ed. Why religion and spirituality matter for public health: Evidence, implications, and resources. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature (2018).

20

Jacob K Patel V . Classification of mental disorders: a global mental health perspective. Lancet. (2014) 383:1433–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62382-X

21

Milstein G Manierre A Yali AM . Psychological care for persons of diverse religions: A collaborative continuum. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. (2010) 41:371–81. doi: 10.1037/a0021074

22

Peng-Keller S Winiger F Rauch R . The Spirit of Global Health: The World Health Organization and the ‘Spiritual Dimension’ of Health, 1946-2021. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (2022).

23

Milstein G Manierre A . Culture ontogeny: Lifespan development of religion and the ethics of spiritual counselling. Counsel Spiritual. (2012) 31:9–30.

24

Kaplan K Salzer MS Brusilovskiy E . Community participation as a predictor of recovery-oriented outcomes among emerging and mature adults with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2012) 35:219–29. doi: 10.2975/35.3.2012.219.229

25

Hankerson SH Svob C Jones MK . Partnering with black churches to increase access to care. Psychiatr Serv. (2018) 69:125. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.69201

26

Idler EL . Religion as a social determinant of public health. New York: Oxford University Press (2014).

27

Long KNG Symons X VanderWeele TJ Balboni TA Rosmarin DH Puchalski C et al . Spirituality as A determinant of health: emerging policies, practices, and systems. Health Aff (Millwood). (2024) 43:783–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01643

28

Milstein G Middel D Espinosa A . Consumers, clergy, and clinicians in collaboration: Ongoing implementation and evaluation of a mental wellness program. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2017) 20:34–61. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2016.1267052

29

World Health Organization . Improving mental health and related service environments and promoting community inclusion - WHO QualityRights training to act, unite and empower for mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

30

Winiger F Peng-Keller S . Religion and the World Health Organization: an evolving relationship. BMJ Global Health. (2021) 6:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004073

31

Pargament KI . The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Publications (2001).

32

Pargament KI Exline JJ . Working with spiritual struggles in psychotherapy: From research to practice. New York: Guilford Publications (2021).

33

Koenig HG VanderWeele T Peteet JR . Handbook of Religion and Health. 3rd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press (2023).

34

Rosmarin DH Koenig HG . Handbook of spirituality, religion, and mental health. 2 ed. Waltham, MA: Elsevier (2020).

35

Balboni TA VanderWeele TJ Doan-Soares SD Long KNG Ferrell BR Fitchett G et al . Spirituality in serious illness and health. JAMA. (2022) 328:184–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.11086

36

Stelzer E-M Palitsky R Hernandez EN Ramirez EG O’Connor M-F . The role of personal and communal religiosity in the context of bereavement. J Prev Intervent Commun. (2020) 48:64–80. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2019.1617523

37

Rudolfsson L Milstein G . Clergy and mental health clinician collaboration in Sweden: Pilot Survey of COPE. Ment Health Religion Cult. (2019) 22:805–18. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2019.1666095

38

Currier JM Fox J Vieten C Pearce M Oxhandler HK . Enhancing competencies for the ethical integration of religion and spirituality in psychological services. psychol Serv. (2022) 20(1):40–50. doi: 10.1037/ser0000678

39

Milstein G Sims E Liggins L . Community outreach by a mental health center: A dialogue with clergy. Community Psychol. (1999) 32:49–51.

40

Milstein G Midlarsky E Link BG Raue PJ Bruce ML . Assessing problems with religious content: a comparison of rabbis and psychologists. J Nervous Ment Dis. (2000) 188:608–15. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200009000-00008

41

Milstein G Kennedy GJ Bruce ML Flannelly K Chelchowski N Bone L . The clergy’s role in reducing stigma: elder patients’ views. World Psychiatry. (2005) 4:26–32.

42

Milstein G Manierre A Susman V Bruce ML . Implementation of a program to improve the continuity of mental health care through clergy outreach and professional engagement (COPE). Prof Psychol: Res Pract. (2008) 39:218–28. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.218

43

Milstein G Manierre A . Normative and diagnostic reactions to disaster: clergy and clinician collaboration to facilitate a continuum of care. In: BrennerGHBushDHMosesJ, editors. Creating Spiritual and Psychological Resilience: Integrating Care in Disaster Relief Work. Routledge, New York (2010). p. 219–26.

44

Ali O Milstein G . United States’ Imams’ Recognition of mental illness and their willingness to refer. J Muslim Ment Health. (2012) 6:3–13. doi: 10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0006.202

45

Milstein G . Disasters, psychological traumas, and religions: Resiliencies examined. psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. (2019) 11:559–62. doi: 10.1037/tra0000510

46

Milstein G Palitsky R Cuevas A . The religion variable in community health promotion and illness prevention. J Prev Intervent Commun. (2020) 48:1–6. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2019.1617519

47

Putnam RD . Bowling Alone: Revised and Updated: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Second ed. New York: Simon & Schuster (2020).

48

Putnam RD Garrett SR . The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. New York: Simon & Schuster (2020).

49

Case A Deaton A . Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2021).

50

McCann RV . Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health: The churches and mental health. EwaltJR, editor. New York: Basic Books (1962). 278 p.

51

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Building Bridges: Mental Health Consumers and Members of Faith-Based and Community Organizations in Dialogue. Services USDoHaH(SAMHSA) SAaMHSAServices CfMH, editors. Rockville, MD: United States’ Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Mental Health Services (2004).

52

Desai MU Guy K Brown M Thompson D Manning B Johnson S et al . That Was a State of Depression by Itself Dealing with Society”: Atmospheric racism, mental health, and the Black and African American faith community. Am J Community Psychologyl. (2024) 73:104–17. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.v73.1-2

53

Hankerson SH Suite D Bailey RK . Treatment disparities among African American men with depression: implications for clinical practice. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2015) 26:21–34. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0012

54

Pew Research Center . America’s Changing Religious Landscape. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center (2015).

55

Wang PS Berglund PA Kessler RC . Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv Res. (2003) 38:647–73. doi: 10.1111/hesr.2003.38.issue-2

56

Berry JW Hou F . Multiple belongings and psychological well-being among immigrants and the second generation in Canada. Can J Behav Science/Revue Can Des Sci du Comportement. (2019) 51:159. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000130

57

Nguyen AW Taylor RJ Chatters LM . Church-Based social support among Caribbean blacks in the United States. Rev Relig Res. (2016) 58:385–406. doi: 10.1007/s13644-016-0253-6

58

Lynn CA Lee SA . Newcomers in a nontraditional receiving community: Korean immigrant adaptation strategies in the American deep south. Qual Rep. (2016) 21:2209–29. doi: 10.46743/nsu_tqr

59

Koenig M Maliepaard M Güveli A . Religion and new immigrants’ labor market entry in Western Europe. Ethnicities. (2016) 16:213–35. doi: 10.1177/1468796815616159

60

Sanchez F Gaw A . Mental health care of Filipino Americans. Psychiatr Serv. (2007) 58:810–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.810

61

Kokanovic R Petersen A Klimidis S . ‘Nobody Can Help Me … I am Living Through it Alone’: Experiences of Caring for People Diagnosed with Mental Illness in Ethno-Cultural and Linguistic Minority Communities. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2006) 8:125–35. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-8521-0

62

Marwaha S Livingston G . Stigma, racism or choice. Why do depressed ethnic elders avoid psychiatrists? J Affect Disord. (2002) 72:257–65.

63

Idler E . Equal protection? Differential effects of religious attendance on black-white older adult mortality. Innovation Aging. (2020) 4:395–. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igaa057.1271

64

Nguyen H . Linking social work with buddhist temples: developing a model of mental health service delivery and treatment in Vietnam. Br J Soc Work. (2013) 45(4):1242:58. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct181

65

Osler W . The faith that heals. BMJ: Br Med J. (1910) 1:1470–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2581.1470

66

Geertz C . Religion as a cultural system. In: GeertzC, editor. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Third ed, vol. 2017 . Basic Books, New York (1966). p. 87–125.

67

Darwin CR . The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. First ed. London: J. Murray (1871).

68

Santayana G . The Life of Reason or the Phases of Human Progress. Reason in Religion. New York: C. Scribner’s sons (1905).

69

Fergusson D . Theology and therapy: Maintaining the connection. Pacifica. (2013) 26:3–16. doi: 10.1177/1030570X12469087

70

Puchalski CM Vitillo R Hull SK Reller N . Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. (2014) 17:642–56. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427

71

Hill PC Pargament KI Hood RWJ McCullough ME Swyers JP Larson DB et al . Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. J Theory Soc Behav. (2000) 30:51–77. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.2000.30.issue-1

72

Fowler JW . Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. New York: Harper & Row (1981). 332 p.

73

Dunbar RIM . Religion, the social brain and the mystical stance. Arch Psychol Relig. (2020) 42:46–62. doi: 10.1177/0084672419900547

74

Grammich C Dollhopf EJ Gautier ML Houseal R Jones DE Krindatch A et al . 2020 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study. University Park, PA: Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (2023). Available at: https://www.usreligioncensus.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/2020_US_Religion_Census.pdf (Accessed May 23, 2025).

75

Chaves M Hawkins M Holleman A Roso J . Introducing the Fourth Wave of theNational Congregations Study. J Sci Stud Religion. (2020) 59(4):646–50.

76

Govig SD . In the Shadow of Our Steeples: Pastoral Presence for Families Coping with Mental Illness Vol. xiv. . New York: Haworth Pastoral Press (1999). 122 p.

77

Jernigan HL . Pastoral care and the crises of life. In: ClinebellHJ, editor. Community mental health: the role of church & temple. Nashville: Abingdon Press (1970).

78

Shifrin J . The Faith community as a support for people with mental illness. New Dir Ment Health Serv. (1998) 1998:69–80. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319988009

79

Campbell MK Hudson MA Resnicow K Blakeney N Paxton A Baskin M . Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health. 28. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews (2007) p. 213–34.

80

Park CL Currier JM Harris JI Slattery JM . Trauma, meaning, and spirituality: Translating research into clinical practice. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association (2017). doi: 10.1037/15961-000

81

Lotufo Z . Cruel God, kind God: How images of God shape belief, attitude, and outlook Vol. ix. . Santa Barbara, CA, US: Praeger/ABC-CLIO (2012) p. 185–ix, p.

82

Aten JD O’Grady KA Milstein G Boan D Smigelsky MA Schruba A et al . Providing spiritual and emotional care in response to disaster. In: WalkerDFCourtoisCAAtenJDWalkerDFCourtoisCAAtenJD, editors. Spiritually oriented psychotherapy for trauma. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US (2015). p. 189–210.

83

Bockrath MF Pargament KI Wong S Harriott VA Pomerleau JM Homolka SJ et al . Religious and spiritual struggles and their links to psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Religion Spiritual. (2022) 14:283–99.

84

Currier JM Holland JM Drescher KD . Spirituality factors in the prediction of outcomes of PTSD treatment for U.S. military veterans. J Trauma Stress. (2015) 28:57–64. doi: 10.1002/jts.2015.28.issue-1

85

Exline JJ . Stumbling blocks on the religious road: Fractured relationships, nagging vices, and the inner struggle to believe. psychol Inquiry. (2002) 13:182–9. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1303_03

86

Exline JJ Yali AM Sanderson WC . Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. J Clin Psychol. (2000) 56:1481–96. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200012)56:12<1481::AID-1>3.0.CO;2-A

87

Hinshaw SP . The Mark of Shame: Stigma of Mental Illness and an Agenda for Change. New York: Oxford University Press (2007). 352 p.

88

Sullivan WP . Recoiling, regrouping, and recovering: first-person accounts of the role of spirituality in the course of serious mental illness. New Dir Ment Health Serv. (1998) 1998:25–33. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319988005

89

Milstein G Guarnaccia PJ Midlarsky E . Ethnic differences in the interpretation of mental illness: perspectives of caregivers. In: GreenleyJR, editor. Research in Community and Mental Health: the Family and Mental Illness. Research in Community and Mental Health. 8. JAI Press, Inc, Greenwich, CT (1995). p. 155–78.

90

Mahoney A . The Science of Children’s Religious and Spiritual Development. BornsteinMH, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2021).

91

Hong B Scribner S Downs D Jackson-Beavers R Wright T Orson W et al . The Saint Louis bridges program: A mental health network of more than one hundred churches and the mental health community. Journal of the National Medical Association. (2024) 116(1):16–23.

92

Stanford J . An introductory discourse, delivered to the lunatics in the asylum, city of New York. Am J Insanity. (1819/1847) 4:39–45. doi: 10.1176/ajp.4.1.39

93

American Public Health Association . Can the clergy aid the health officer in the upbuilding of mental health? Am J Public Health. (1946) 36:1313–4.

94

Blizzard SW . The minister’s dilemma. Christian Century. (1956) 73:508.

95

Milstein G . Religion and mental health care in practice: A nationwide, cross-sectional survey of rabbis and psychologists. New York: Columbia University (1999).

96

Milstein G Bruce ML Gargon N Brown E Raue PJ McAvay G . Religious practice and depression among geriatric homecare patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2003) 33:71–83. doi: 10.2190/MUP1-DFB4-23KK-XPCF

97

Ali O Milstein G Marzuk P . The Imam’s role in meeting the counseling needs of Muslim communities in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. (2005) 56:202–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.202

98

Milstein G Dugan T Siegel C Haugland G . A Pastoral Education Guide: Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Multicultural Faith Communities. Orangeburg, NY: New York State Office of Mental Health, The Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research Center of Excellence in Culturally Competent Menial Health (2011). Available at: http://nkiccase.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/mentalhealthclergyguide101711A.pdf (Accessed May 28, 2025).

99

Milstein G Dugan T Siegel C Haugland G . A Pastoral Education Workbook: Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Multicultural Faith Communities. Orangeburg, NY: New York State Office of Mental Health, The Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research Center of Excellence in Culturally Competent Menial Health (2011). Available at: http://nkiccase.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/mentalhealthworkbook111511.pdf (Accessed May 28, 2025).

100

Nieuwsma JA Rhodes JE Jackson GL Cantrell WC Lane ME Bates MJ et al . Chaplaincy and mental health in the department of veterans affairs and department of defense. J Health Care Chaplaincy. (2013) 19:3–21. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2013.775820

101

Aten JD O’Grady KA Milstein G Boan D Schruba A . Spiritually oriented disaster psychology. Spiritual Clin Pract. (2014) 1:20–8. doi: 10.1037/scp0000008

102

Milstein G . COPE: A bridge between islam and mental health care through collaborative programs for consumers, clergy and clinicians. In: AytenAKoçMTınazN, editors. Religious-Spiritual Counselling & Care. Center for Values Education Press, Istanbul, Turkey (2016). p. 167–83.

103

Milstein G Ferrari JR . Religion, cultural competence, and community service: promoting wellness - responding to stress - facilitating sustained recovery. In: HoffmanA, editor. Creating a Transformational Community: The Fundamentals of Stewardship Activities. Lexington Books, Lanham, MD (2017). p. 105–28.

104

Currier JM Pearce M Carroll TD Koenig HG . Military veterans’ preferences for incorporating spirituality in psychotherapy or counseling. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. (2018) 49:39–47. doi: 10.1037/pro0000178

105

Engelman J Milstein G Schonfeld IS Grubbs JB . Leaving a covenantal religion: Orthodox Jewish disaffiliation from an immigration psychology perspective. Ment Health Religion Cult. (2020) 23:153–72. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2020.1744547

106

Milstein G Ferrari JR . Supporting the wellness of laity: clinicians and Catholic deacons as mental health collaborators. J Spiritual Ment Health. (2022) 24(2):172:90.

107

Milstein G Hybels CF Proeschold-Bell RJ . A prospective study of clergy spiritual well-being, depressive symptoms, and occupational distress. Psychol Religion Spiritual. (2020) 12:409–16. doi: 10.1037/rel0000252

108

Baldwin I Poje AB . Rural faith community leaders and mental health center staff: Identifying opportunities for communication and cooperation. J Rural Ment Health. (2020) 44:16–25. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000126

109

Singh H Shah AA Gupta V Coverdale J Harris TB . The efficacy of mental health outreach programs to religious settings: A systematic review. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2012) 15:290–8. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2012.703557

110

Smith AE Riding-Malon R Aspelmeier JE Leake V . A qualitative investigation into bridging the gap between religion and the helping professions to improve rural mental health. J Rural Ment Health. (2018) 42:32–45. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000093

111

Milstein G . Clergy and psychiatrists: opportunities for expert dialogue. Psychiatr Times. (2003) 20:36–9.

112

Salcone SG Currier JM Hinkel HM Pearce MJ Wong S Pargament KI . Evaluation of Spiritual Competency Training in Mental Health (SCT-MH): A replication study with mental health professionals. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. (2023) 54:336–41. doi: 10.1037/pro0000525

113

Clark MT Littlemore J Taylor J Debelle G . Child abuse linked to faith or belief: working towards recognition in practice. Nurs Children Young People. (2023) 35:34–42. doi: 10.7748/ncyp.2022.e1444

114

Puchalski CM . The ©FICA Spiritual History Tool. Washington, DC: George Washington Institute for Spirituality & Health (2022).

115

Borneman T Ferrell B Puchalski CM . Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2010) 40:163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019

116

Vermandere M Choi YN De Brabandere H Decouttere R De Meyere E Gheysens E et al . GPs’ views concerning spirituality and the use of the FICA tool in palliative care in Flanders: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. (2012) 62:e718–25. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X656865

117

Herth K . Hope in the family caregiver of terminally ill people. J Adv Nurs. (1993) 18:538–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18040538.x

118

Pargament KI . Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York, NY US: Guilford Press (2007).

119

Anandarajah G Hight E . Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Family Physician. (2001) 63:81–9.

120

Pearce MJ Pargament KI Oxhandler HK Vieten C Wong S . A novel training program for mental health providers in religious and spiritual competencies. Spiritual Clin Pract. (2019) 6:73–82. doi: 10.1037/scp0000195

121

Pearce MJ Pargament KI Oxhandler HK Vieten C Wong S . Novel online training program improves spiritual competencies in mental health care. Spiritual Clin Pract. (2020) 7:145–61. doi: 10.1037/scp0000208

122

Abrams Z . Can religion and spirituality have a place in therapy? Experts say yes. Monit Psychol. (2023) 54(8):67.

123

Jorm AF . Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol. (2012) 67:231–43. doi: 10.1037/a0025957

124

Midgley G Lindhult E . A systems perspective on systemic innovation. Syst Res Behav Sci. (2021) 38:635–70. doi: 10.1002/sres.v38.5

125

Sterman JD . Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:505–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043

126

McLeroy KR . Thinking of systems. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:402. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084459

127

Joiner TE . The interpersonal theory of suicide: guidance for working with suicidal clients. 1st ed Vol. x. . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2009). 246 p.

128

Davidson L . Recovering a sense of self in schizophrenia. J Pers. (2020) 88:122–32. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12471

129

Hefti R . Integrating religion and spirituality into mental health care, psychiatry and psychotherapy. Religions. (2011) 2:611–27. doi: 10.3390/rel2040611

130

Scioli A Ricci M Nyugen T Scioli ER . Hope: Its nature and measurement. Psychol Religion Spiritual. (2011) 3:78–97. doi: 10.1037/a0020903

131

Swarbrick M Brice G . Sharing the message of hope, wellness, and recovery with consumers psychiatric hospitals. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2006) 9:101–9. doi: 10.1080/15487760600876196

132

Uncapher H Gallagher-Thompson D Osgood NJ Bongar B . Hopelessness and suicidal ideation in older adults. Gerontol Soc America. (1988) 38:62–70.

133

Vandecreek L Nye C Herth K . Where theres life, theres hope, and where there is hope, there is …. J Religion Health. (1994) 33:51–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02354499

134

Krause N . Assessing the relationships among religiousness, loneliness, and health. Arch Psychol Relig Archiv Fur Religionspsychologie. (2016) 38:278–300. doi: 10.1163/15736121-12341330

135

Davidson L . Living outside mental illness: qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia Vol. xii. . New York: New York University Press (2003). 227 p.

136

Davidson L Ridgway P Wieland M O’Connell M . A capabilities approach to mental health transformation: A conceptual framework for the recovery era. Can J Community Ment Health. (2009) 28:35–46. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2009-0021

137

McGorry P van Os J . Redeeming diagnosis in psychiatry: timing versus specificity. Lancet. (2013) 381:343–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61268-9

138

Fitchett G Burton LA Sivan AB . The religious needs and resources of psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. (1997) 185(5):320–6.

139

Bonanno GA . The other side of sadness: what the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss. Revised paperback edition. New York: Basic Books (2019). cm p.

140

Engel GL . The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. (1977) 196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

141

Kleinman A . Culture, bereavement, and psychiatry. Lancet. (2012) 379:608–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60258-X

142

Krause NM . Religion, virtues, and health: new directions in theory construction and model development. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press (2022).

143

Falkenburg JL van Dijk M Tibboel D Ganzevoort RR . The fragile spirituality of parents whose children died in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Health Care Chaplaincy. (2020) 26:117–30. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2019.1670538

144

Miller L . The awakened brain: the new science of spirituality and our quest for an inspired life. First edition Vol. xii. . New York: Random House (2021). 272 p.

145

Otto R . The idea of the holy; an inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational. Revised with additions Vol. xix. . London: Oxford University Press (1917/1958). 1, 239 p., 1 p.

146

Myers NAL . Recovery’s edge: an ethnography of mental health care and moral agency Vol. xii. . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press (2015). 191 p.

147

Glasgow RE Harden SM Gaglio B Rabin B Smith ML Porter GC et al . RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. (2019) 7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

148

Alegría M NeMoyer A Falgàs Bagué I Wang Y Alvarez K . Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Current Psychiatry Reports. (2018) 20(11):95.

Appendix 1 COPE: Building Bridges Map Instructions

-

Create COPE Asset Map in Google Sheets

-

Fields to include: Existing Connection, Name of Church, Religious Affiliation, Denomination, Location, Address, Active Website with Link, Contact Information, Phone Number, Email, Food Resource, Counseling Resource, Housing Resource.

-

Google search to fill in R/S Asset Map.

> Complete R/S Asset Map using Google. Look for church websites and/or social media pages. Include the church if it has an active website and at least one email address to reach out to the institution.

-

Call to further fill in the R/S Asset Map.

> Further fill out the R/S Asset Map by calling the phone number listed on the church website.

-

Create COPE Building Bridges Map in Google Maps.

-

Example: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1Cpub66kfu0OD_pcH6wBwyAKEyCJw6f4&usp=sharinghttps://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1Cpub66kfu0OD_pcH6wBwyAKEyCJw6f4&usp=sharing

-

Go to Google My Maps and select “Create a New Map.”

-

-

Edit map title & description.

> Add the map title and description. Save information.

-

Add layers into Map

> Select “Add layer” _and then “Edit layer name” _to rename it to the categories from the R/S Asset Map (Congregations, Other FBOs, Mental Health Service Organization, Healthcare Organization, Food Resource, Counseling Resource, Housing Resource).

-

Type the address in the search bar. Press enter. Click “add to map.”

-

Edit the data table affiliated with the layer.

-

Select the three vertical dots next to the name of the layer. This will open the data table. Insert and name columns as needed based on the layer.

-

Refer to the R/S Asset Map to determine what columns to add to the layer (Point of Contact, Denomination, Solid Welcome, Website).

-

-

Consider changing the color of each layer to better distinguish them from one another.

-

Drop pins into Map for each Church identified in the R/S Asset Map.

> Search for Church in the Search Bar. A pin will be dropped into the location of the Church on the Map. Click the + button to add the Church into your Map. Drag the Church under the appropriate layer. Note that some Churches may be found under multiple layers, depending on the services provided.

-

Open each Church to add content to the data table.

> Select the pencil icon. Input the content into the data table from the R/S Asset Map. Once all content is added to the Map, you can turn on and off the layers by selecting the check box to the left of the name of the layer.

-

Set the privacy features and sharing capabilities of the Map.

> Select “Share” and edit how to share it based on your needs.

Appendix 2 – Online COPE Webinars:

U.S. Health & Human Services Center for Faith & Opportunity Initiatives

Milstein, G., Steinberg, T., Eckert, D. & Moister, D. (2020, August). Meaning & Meaningfulness: Building Bridges across Borders of Religion & Mental Health Care. Webinar for the series, Treating The Whole Person: Faith and Mental Health Professionals Partner to Address Mental Illness, sponsored by the U.S. Health & Human Services Center for Faith & Opportunity Initiatives, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceBj7v48Tso)