Abstract

Objective:

To examine the mediating effects of social exclusion and experiential avoidance on college students’ emotional intelligence and problematic social media use.

Methods:

Using convenience sampling, 1,448 students enrolled at nine public universities in Chengdu, Beijing, Shanghai, and Kunming were recruited from May 1, 2021, to October 28, 2021. The Emotional Intelligence Scale, the Social Exclusion Questionnaire for College Students, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, and the Problematic Mobile Social Media Use Assessment Questionnaire for Adolescents were used to conduct the survey.

Results:

The results showed that college students’ emotional intelligence was negatively correlated with social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and problematic social media use (p < 0.01). Social exclusion among college students was positively correlated with experiential avoidance and problematic social media use (p < 0.01), and experiential avoidance was positively correlated with problematic social media use (p < 0.01). This study revealed that college students’ emotional intelligence directly influences their problematic social media use. Social exclusion and experiential avoidance mediated, and sequentially chain-mediated, the effects of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use.

Conclusion:

Emotional intelligence can potentially influence problematic social media use directly and indirectly through social exclusion and experiential avoidance.

1 Introduction

With the rapid development and popularization of the Internet, global Internet usage has increased by 1,331.9% since the beginning of the new century (1). The 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China states that as of December 2023, the Internet penetration rate will reach 77.5%, and the per capita weekly Internet access time will be 26.1 hours. The number of social media users, represented by mobile phone users, reached 1.091 billion (2). Students are heavy social media users; 99.39% of college students use social media daily, 33% use it for 4–6 h a day, and 22.63% use it for more than 7 h per day (3). Compared with offline socialization, the anonymity, idealized self-presentation, lack of time, and geographic constraints that characterize online socialization have lowered the Internet social media use threshold, attracting many college students (4).

Social media significantly strengthens interpersonal communication, maintains social relationships, and alleviates anxiety (5). However, when individuals use online social media with high frequency and intensity to fulfill their psychological needs, it may lead to problematic or pathological use (6, 7). This includes spending most of the day chatting on social media (e.g., WeChat and QQ) and staying up late using TikTok, Weibo, and other social networking services (8), which can lead to addiction-like symptoms (9). This unpleasant condition, known as problematic social media use (PSMU), involves the prolonged and intense use of online social media, which negatively affects the individual’s physical, psychological, and behavioral aspects. However, it does not meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ diagnostic criteria for mental illness (10). According to Jiang, PSMU includes five dimensions: increased viscosity, physiological damage, omission anxiety, cognitive failure, and guilt (11). Among them, “increased stickiness” means that individuals unconsciously use social apps frequently, gradually extend their use time, and become dependent on them, making it difficult for them to control themselves. “Physical damage” refers to the frequent and prolonged use of mobile social networks, which leads to physical problems such as eye fatigue, cervical spine pain, finger discomfort, vision loss, and poor sleep quality. “Missing anxiety” refers to the frequent checking of cell phones for fear of missing important information in social networks, accompanied by feelings of anxiety and uncontrollable urges to use the phone. “Cognitive failure” refers to the frequent and prolonged use of mobile social networks, which leads to distraction, memory loss, and weakening of the ability to think deeply and communicate realistically. “Guilt” refers to the emotional experience of regret and guilt due to the delay in study or work because of spending too much time on mobile social networks (11). PSMU is a subtype of Internet addiction based on traditional Internet addiction. Despite not reaching a pathological level, problematic social media use behaviors can impair an individual’s psychosocial functioning, resulting in depression (12) and anxiety (13); physiological problems such as impaired sleep quality (14, 15) and eating disorders (16); and cognitive impairments such as memory loss and attention deficits (17). This negatively affects physical and mental health. As college students comprise a large percentage of social media users, research has concentrated on the protective and risk factors for PSMU.

Currently, most research on PSMU is similar to that on Internet addiction, with many referencing the interaction of Person–Affect–Cognition–Execution (I-PACE) model of addictive behaviors. This model is the primary theoretical framework for explaining the formation mechanisms of internet addiction, including PSMU (18, 19). This describes how combinations of different factors can lead to Internet-related problems and suggests that core personal characteristics interact with specific affective and cognitive responses, leading to problematic usage patterns. Additionally, according to compensatory Internet use theory (CIUT) (20), individuals use online applications to fulfill their unmet real-life needs. This theory complements the I-PACE model and explains the different factors and motivations that influence PSMU. According to the I-PACE model, emotional intelligence (EI) is one of the core personal traits in the formation and development of PSMU in individuals (21). Previous studies have shown that individuals’ EI is related to social exclusion and that individuals with high social exclusion are prone to compensating through online social media. Due to China’s special accommodation system, all college students must live in school-designated dormitories during the school year. Thus, Chinese college students spend most of their time in group life, they are more sensitive to bad interpersonal relationships and social exclusion, and avoidance behaviors such as interpersonal avoidance increase accordingly. Thus, the sense of social exclusion as an affective factor may be one of the important factors in elucidating the relationship between an individual’s core characteristics (e.g., EI) and coping patterns (e.g., PSMU). According to the I-PACE model, cognitive processes and decision-making coping are among the influences on the formation and development of PSMU in individuals. Chinese college students are more competitive in terms of academics and pressure, which can easily trigger nonadaptive cognitions and avoidance behaviors after being frustrated. Thus, experiential avoidance, as a nonadaptive cognition, can explain to some extent why maladaptive individuals choose to cope with negative events and emotions by overusing online social media.

1.1 Emotional intelligence and problematic social media use

Certain core personal traits may be protective of or susceptible to PSMU (18, 19). As a core personal trait, emotional intelligence may be a distal factor influencing PSMU, necessitating its inclusion in various studies.

EI is the capacity to identify, comprehend, control, and use emotions. It encompasses self-emotional assessment, others’ emotional assessment, control, and use (22). The theory of compensatory network use states that adolescents with lower levels of EI who struggle to control and manage negative emotions may turn to social networks to distract themselves and avoid unpleasant emotions. Over time, this coping mechanism may lead to PSMU. In contrast, those with high EI are more adept at recognizing and managing unpleasant emotions, which lowers psychological stress (23, 24). Previous studies have indicated that low trait EI may trigger problems related to internet addiction (25–27). Recent research has suggested that EI can protect against PSMU (28). Individuals who excel at understanding and regulating their emotions can better adapt to society and engage in face-to-face socialization, reducing their reliance on social media to maintain social connections or share activities. This reduced the risk of social media overuse (29). Higher levels of EI enable individuals to handle emotion-related problems more rationally, better control their emotions, understand others’ emotions, and use the Internet appropriately, thereby preventing Internet addiction (30). In summary, EI was associated with PSMU, with higher EI negatively predicting it.

1.2 Mediating role of social exclusion

The I-PACE model describes affective and cognitive processes as explanatory mechanisms for Internet-related disorders. Social exclusion is an affective factor, while experiential avoidance is a cognitive factor. Social exclusion occurs when an individual is excluded by a social group, which blocks their belonging and relationship needs and leads to feelings of neglect and loneliness. Social exclusion included neglect, rejection, isolation, and denial (31). A correlation may exist between EI and social exclusion. Individuals with low EI are more likely to social exclusion from friends and family, whereas those with high EI can improve their social competence, interpersonal relationships, and social support (32). Additionally, negative life events such as social exclusion are distal factors that trigger adolescent addiction to social media (33). According to the CIUT (20), socially excluded individuals seek psychological resources to satisfy emotional requirements unavailable in offline life. As a convenient compensation method, social media can alleviate negative emotions, such as feelings of exclusion and loneliness, perceived in real-life interpersonal interactions. However, prolonged and high-frequency social media use increases the risk of PSMU. According to general stress theory (34), social exclusion is a stressful event in the external environment that makes socially excluded individuals prone to deviant online behaviors (35). Thus, social exclusion may mediate the effects of EI on PSMU.

1.3 Mediating role of experiential avoidance

Based on the I-PACE model, experiential avoidance, a nonadaptive cognition, involves actively avoiding unpleasant thoughts and emotions and an inability to accept and experience one’s true thoughts and emotions well (36–38). Previous research indicated a significant association between emotional dysregulation and experiential avoidance. The ability to regulate emotions significantly predicts experiential avoidance. The lower an individual’s EI, the more likely they are to adopt avoidant behaviors when encountering difficulties. Experiential avoidance, a method of avoiding negative emotions and experiences, can predispose individuals to fall into an avoidance pattern by allowing them to escape threats for brief periods of pleasantness (39). Previous research indicates that PSMU is an anxiety avoidance strategy associated with experience avoidance (40). Highly socially avoidant adolescents who experience experiential avoidance when encountering unpleasant stimuli are prone to developing PSMU (41). Thus, experiential avoidance may mediate the effects of EI on PSMU.

It has been shown that the experience of social exclusion is closely related to experiential avoidance tendencies, and both significantly predict PSMU among college students (41–43). This may be due to cultural factors specific to Chinese college students, especially collectivist norms, which may increase college students’ sensitivity to social exclusion and avoidance. College students are more sensitive to group belonging, and social exclusion is more likely to trigger avoidant coping, thus seeking emotional regulation and virtual belonging through increased social media use (44). Therefore, social exclusion and experiential avoidance were chosen for this study to provide insight into the psychological mechanisms underlying PSMU.

1.4 Present study

Previous studies have explored the relationship between EI and PSMU, but most of them have focused on Western samples, and not enough relevant studies have been conducted for Chinese populations. There are not enough studies exploring the potential mediating mechanisms between EI and PSMU for Chinese samples. It is of great significance to conduct this study for this research area. On the one hand, it can expand the applicability of the existing results in different cultural contexts, and on the other hand, it can help to deepen the understanding of the occurrence mechanism of PSMU among Chinese college students. This study aimed to investigate how EI affects PSMU among Chinese college students and to provide some basic references for PSMU intervention.

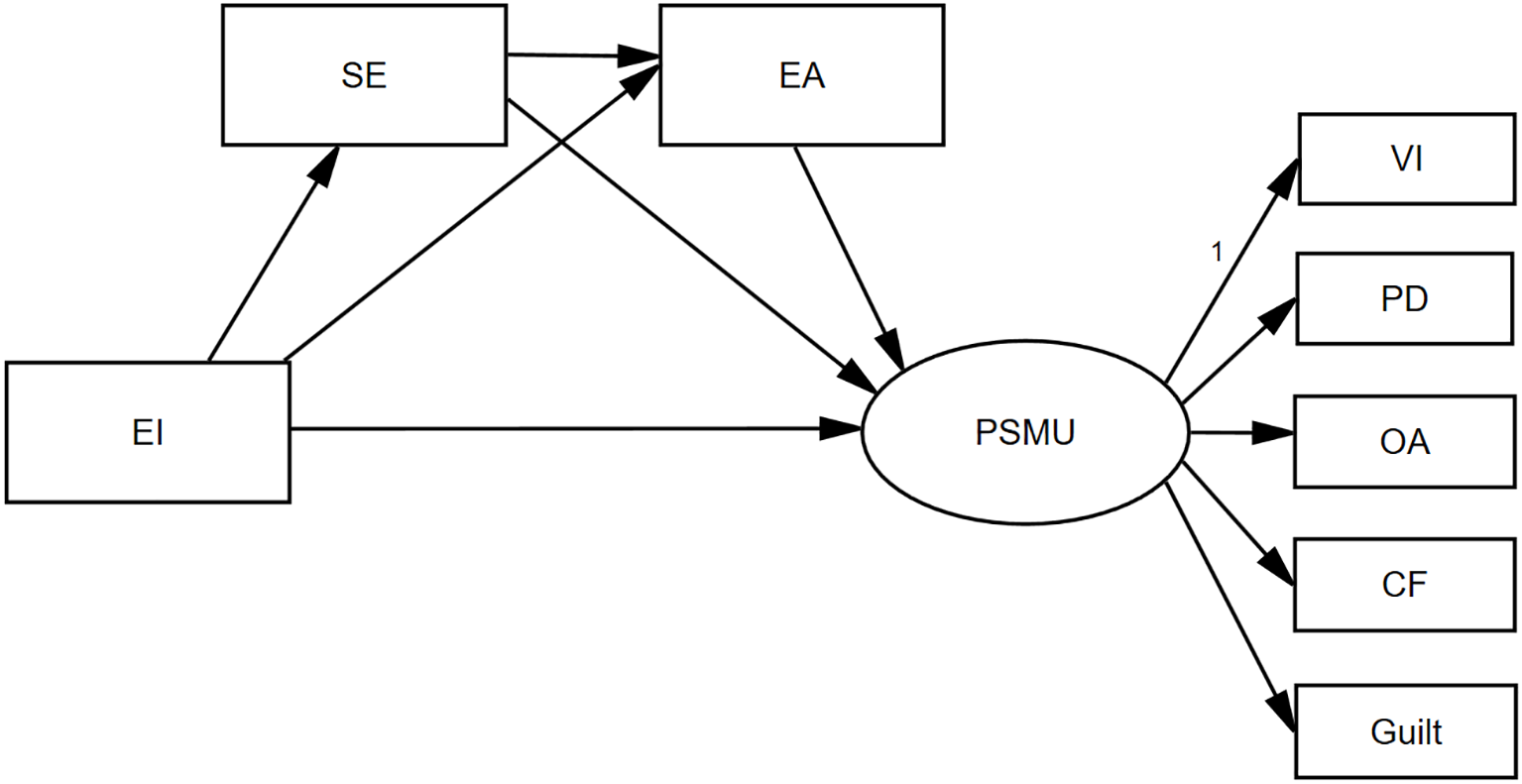

Therefore, the I-PACE model served as a theoretical foundation, EI as a core personal trait, social exclusion and experiential avoidance as affective and cognitive factors, respectively, and PSMU as a pattern of problematic behavior. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed model with the following assumptions:

Figure 1

Theoretical model. EI, emotional intelligence; PSMU, problematic social media use; SE, social exclusion; EA, experiential avoidance; VI, viscosity increase; PD, physiological damage; OA, omission anxiety; CF, cognitive failure. The same as below.

-

H1: EI negatively correlates with social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and PSMU.

-

H2: EI indirectly affects PSMU through social exclusion (H2a) and experiential avoidance (H2b).

-

H3: The relationship between EI and PSMU is serially mediated by social exclusion and experiential avoidance.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Convenience sampling was used to randomly select classes in nine public colleges and universities in Chengdu, Beijing, Shanghai, and Yunnan from May 1, 2021, to October 28, 2021. The survey was conducted through a psychological organization. The target participants were undergraduates and master’s degree students. The investigators surveyed the participants for informed consent. An informed consent statement was incorporated into the distributed paper questionnaire in written form. In this study, the participants’ completion and submission of the questionnaire indicated informed consent and voluntary participation. The content of the informed consent statement in the questionnaire is as follows (Supplementary File S1): “If you confirm that you have understood the content and purpose of this research survey and agree to participate, please complete this questionnaire based on your true situation. If you refuse to participate, please do not complete or return the questionnaire.” Participant anonymity was guaranteed. There were 1,448 valid questionnaires. The mean age difference between males and females was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chengdu Medical College (approval number: 2021NO.07) and strictly adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Wong and Law’s emotional intelligence scale-C

This scale is a Chinese revision of the scale compiled by Wang (22) based on the work of Wong et al. (45), with 16 entries and 4 dimensions (self-emotional assessment, others’ emotional assessment, emotional adjustment, and emotional use). “Self-Emotional Assessment” consists of items 1-4, with two items as examples below: I have a good sense of why I have certain feelings most of the time, and I have a good understanding of my own emotions. “Emotional adjustment” consists of items 5-8, with two items as examples below: I am able to control my temper so that I can handle difficulties rationally, and I am quite capable of controlling my own emotions. “Emotional use” consists of items 9-12, with two items as examples below: I always tell myself I am a competent person, and I am a self-motivating person. “Others’ emotional assessment” consists of items 13-16, with two items as examples below: I always know my friends’ emotions from their behavior, and I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others. On a seven-point rating system, responses range from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”). The overall scores ranged from 16 to 112. Higher overall scores represented a higher EI. The scale is suitable for measuring EI in individuals. The scale has been translated into Chinese and applied in Chinese-speaking cultures with a high degree of cultural adaptability. The scale has been confirmed to be applicable to a sample of Chinese college students by either prior literature or prior research (46–49). The Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.908.

2.2.2 Social exclusion questionnaire for undergraduates

The scale was developed by Wu et al. (31). The scale was used to measure social exclusion among university students. The scale comprises 19 items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Always”). Higher total scores indicated that individuals perceived social exclusion as stronger. The Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.958.

2.2.3 Acceptance and action questionnaire second edition

This scale was designed by Bond et al. (50) and adapted to Chinese by Cao et al. (36). This scale was used to measure the level of experiential avoidance among college students. It comprises seven items on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 7 (“always true”). The overall scores ranged from 7 to 49. Higher overall scores indicate higher levels of experiential avoidance. The Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.914.

2.2.4 Problematic mobile social media usage assessment questionnaire for adolescents

This scale is a behavioral assessment questionnaire for PSMU among adolescents developed by Jiang (11). The scale can be used to measure the level of PSMU among adolescents or college students. It contains 20 items categorized into five factors: viscosity increase, physiological damage, omission anxiety, cognitive failure, and guilt. The scale uses a five-point scale (1 = “Not at All,” 5 = “Fully”). A higher overall score represented a more severe tendency toward PSMU. The Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.951.

2.3 Procedures

In all Chinese universities, there are regular psychological support groups consisting of psychology committee members. Each class has a psychological committee member. Professional psychology committee members were contacted through psychological support groups, and offline paper questionnaires were collected. Two graduate psychology students and one psychology committee member from each program collaborated to distribute and collect questionnaires. Two graduate psychology students informed the participants of the study’s purpose before distributing the questionnaires. The participants initiated the survey with their consent. Questionnaires were collected uniformly after distribution. The questionnaire comprised a consent section, guidelines, questions, and notes. A questionnaire was considered invalid if less than one-third of the questions were completed or if many responses showed a regular pattern. After removing 127 invalid questionnaires from the 1,575 recovered questionnaires, 1,448 valid questionnaires with a validity rate of 91.94% remained.

2.4 Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Windows software version 22.0, employing descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, ANOVA, and correlation analysis. Structural equation modeling was performed using AMOS 22.0, and the mediating effect was tested using SPSS-Process 3.3. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The model fit indices were as follows: AGFI, GFI, NFI, CFI, and TLI > 0.95; RMSEA < 0.05 (good model); AGFI, GFI, NFI, CFI, and TLI > 0.80; RMSEA < 0.08 (acceptable models) (51, 52). Harman’s one-factor test was used to test Common Method Deviation, with the explanatory power of the first factor not surpassing the critical value of 50% (53).

3 Results

3.1 Common method deviation test

The first-factor interpretation percentage was 38.44%, lower than the critical value criterion of 50%, suggesting no serious common method bias (53).

3.2 Basic information and sex differences in emotional intelligence, social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and problematic social media use

Table 1 presents the basic information and sex differences for each variable. After removing 127 invalid questionnaires from the 1,575 recovered questionnaires, 1,448 valid questionnaires with a validity rate of 91.94% remained. Of them, 732 (50.8%) were males and 708 (49.2%) were females. Their overall mean age was 20.94 ± 2.07, with 21.07 ± 2.18 years for males and 20.79 ± 1.94 years for females. Gender differences appeared in social exclusion, with males scoring significantly higher than females on social exclusion (p < 0.05). Other factors showed no significant sex-related differences.

Table 1

| Variables | M ± SD | Male M ± SD | Female M ± SD | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1448 | n = 732 | n = 708 | ||

| 1. EI | 75.5 ± 17.21 | 75.44 ± 17.07 | 75.46 ± 17.40 | –0.02 |

| 2. Social exclusion | 39.05 ± 16.64 | 40.11 ± 16.67 | 38.07 ± 16.60 | 2.32* |

| 3. Experiential avoidance | 24.72 ± 9.56 | 25.02 ± 9.49 | 24.44 ± 9.65 | 1.15 |

| 4. PSMU | 61.71 ± 19.15 | 61.72 ± 19.35 | 61.82 ± 19.00 | –0.1 |

| Viscosity increase | 17.15 ± 5.13 | 17.23 ± 5.13 | 17.10 ± 5.15 | 0.51 |

| Physiological damage | 14.78 ± 5.89 | 14.79 ± 5.92 | 14.82 ± 5.86 | –0.10 |

| Omission anxiety | 12.45 ± 4.39 | 12.55 ± 4.43 | 12.37 ± 4.35 | 0.76 |

| Cognitive failure | 11.47 ± 3.99 | 11.33 ± 3.99 | 11.63 ± 4.00 | –1.43 |

| Guilt | 5.85 ± 2.63 | 5.81 ± 2.70 | 5.90 ± 2.56 | –0.62 |

Basic information and sex differences across variables.

* denotes p <.05.

3.3 Correlational analysis

Table 2 shows that EI was substantially negatively correlated with social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and PSMU. Social exclusion was substantially positively correlated with experiential avoidance and PSMU. Experiential avoidance was substantially positively correlated with PSMU. Therefore, H1 was supported.

Table 2

| Variables | Social exclusion | Experiential avoidance | PSMU | Viscosity increase | Physiological damage | Omission anxiety | Cognitive failure | Guilt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | –0.673** | –0.607** | –0.566** | –0.504** | –0.526** | –0.534** | –0.428** | –0.418** |

| Social exclusion | 1 | 0.661** | 0.567** | 0.525** | 0.532** | 0.593** | 0.376** | 0.353** |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.661** | 1 | 0.619** | 0.584** | 0.574** | 0.570** | 0.453** | 0.448** |

Bivariate correlation analysis of variables.

** denotes p <.01.

3.4 Mediating effect test of the overall model

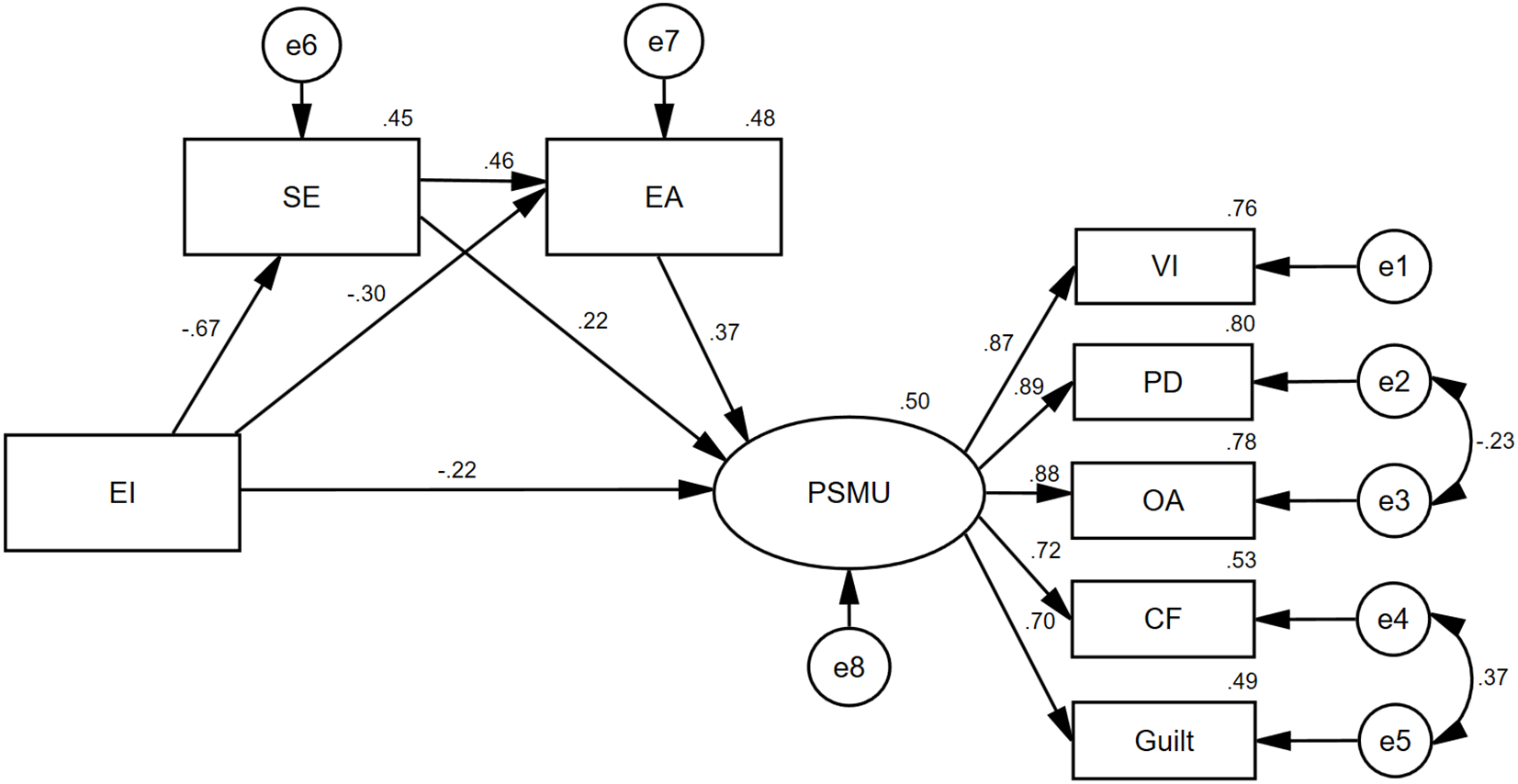

This study employed AMOS to analyze data from 1,448 college and university students. The results showed that All pathways were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Guided by the modification indices (MI), the initial model was revised to obtain a final model with a good fit (Figure 2). Table 3 lists the model fit indices.

Figure 2

Mediating role of social exclusion and experiential avoidance on the impact of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use.

Table 3

| Model | X2 | df | X2/df | AGFI | GFI | NFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial model | 298.905 | 17 | 17.583 | 0.888 | 0.947 | 0.962 | 0.964 | 0.940 | 0.107 |

| Final model | 111.257 | 15 | 7.417 | 0.954 | 0.981 | 0.986 | 0.988 | 0.977 | 0.067 |

| Indices | > 0.95 | > 0.95 | > 0.95 | > 0.95 | > 0.95 | < 0.08 | |||

| Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Acceptable |

Model fit comparison.

The final model (Figure 2) demonstrated that EI directly predicted PSMU. Both social exclusion and experiential avoidance partially mediate the effects of EI on PSMU. Social exclusion and experiential avoidance sequentially mediated the impact of EI on PSMU.

This study employed the SPSS add-in process (54) and further tested mediating effects using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method (5,000 replicate samples). The results (Table 4) show that the 95% confidence intervals for all paths exclude zero, suggesting that all paths are significant.

Table 4

| Effect | Effect value | SE | 95% CI | Ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | EI→PSMU | –0.63 | 0.02 | [–0.68, –0.58] | |

| Direct effects | EI→Social exclusion | –0.65 | 0.02 | [–0.69, –0.61] | |

| EI→Experiential avoidance | –0.16 | 0.01 | [–0.19, –0.14] | ||

| Social exclusion→Experiential avoidance | 0.27 | 0.02 | [0.24, 0.29] | ||

| Social exclusion→PSMU | 0.20 | 0.03 | [0.13, 0.26] | ||

| Experiential avoidance→PSMU | 0.74 | 0.05 | [0.63, 0.85] | ||

| EI→PSMU | –0.25 | 0.03 | [–0.31, –0.19] | 39.68% | |

| Indirect effects | EI→Social exclusion→PSMU | –0.13 | 0.02 | [–0.17, –0.08] | 20.63% |

| EI→Experiential avoidance→PSMU | –0.12 | 0.02 | [–0.16, –0.09] | 19.05% | |

| EI→Social exclusion→Experiential avoidance→PSMU | –0.13 | 0.01 | [–0.15, –0.10] | 20.63% | |

Bootstrap analysis of the mediated effects test.

4 Discussion

4.1 Current situation of college students’ emotional intelligence, social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and problematic social media use

This study demonstrated that no significant sex differences existed in any of the variables except for social exclusion, with males having higher social exclusion scores than females. This finding suggests that males were more socially excluded than females, which is consistent with the findings of Lev-Wiesel et al. (55), possibly because males are more impulsive, less able to control their emotions and behavior during interpersonal conflicts, more likely to conflict with others, and consequently, more likely to experience social exclusion over time. Being more affectionate and warm, females tended to develop similar traits. They believe they are more jeopardized by social exclusion than males, making them more reluctant to experience rejection (56). Previous studies have suggested sex differences in EI (57). Consistent with Marco et al. (58), our study failed to find any significant sex differences in EI. EI manifests in introspection, stress management, and interpersonal relationships. Males outperformed females in introspection and coping with stressful emotions. Females outperformed males in terms of empathy and socialization. While the dominant EI abilities differed between sexes, there was no absolute difference in the overall level of EI, explaining the lack of significant sex differences in EI scores. This study found no significant gender differences in experiential avoidance, consistent with the results of Munsamy et al. (59). This may be because both males and females experience emotional stress and anxiety when encountering difficulties, leading to certain avoidance behaviors and resulting in minimal sex-based differences in experiential avoidance. Additionally, there were no significant sex differences in PSMU, consistent with Primack et al. (60). This may be due to the continuous progress in modern information and communication technology, increasingly powerful smartphones, and social applications that align with individual needs. The widespread use of social applications, such as WeChat, TikTok, and QQ, has normalized this phenomenon in social network communication. Smartphones’ portability and ease of use make them less susceptible to external factors. Therefore, there is little distinction between males and females regarding the opportunities and duration of their social media use, nor is there much difference in the effects of their usage on themselves (61).

4.2 Impact of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use

This study aimed to investigate how EI affects PSMU. The results showed that EI was negatively related to PSMU and directly predicted it. EI acts as a core personal trait that protects against PSMU. College students with higher EI were at a lower risk of PSMU, consistent with the findings of Barberis et al. (28). PSMU can be considered a maladaptive and negative coping mechanism (62). College students with lower EI are less able to manage stress-related negative emotions, thus adopting nonadaptive strategies to cope with emotional problems, diverting attention, and alleviating distress through external resources, such as social media, ultimately resulting in PSMU (63, 64). According to impulsivity theory (65), individuals with high emotional control exhibit less impulsive Internet use. Therefore, improving the EI of college students can be an intervention for PSMU, leading to improved functioning in areas such as scholastic achievement, interpersonal interactions, and physical and psychological well-being (66). It can also reduce the tendency toward addictive behaviors (30).

4.3 Mediating role of social exclusion in the effect of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use

EI was negatively correlated with social exclusion, whereas social exclusion was positively correlated with PSMU. EI indirectly influences PSMU through social exclusion, supporting H2a. Prior studies have examined how EI affects peer interactions and social support (67). However, there is not enough literature on the direct effects of EI on social exclusion in Chinese samples. This study confirmed that EI affects social exclusion. Individuals with high EI are more adept at perceiving and utilizing social support (67). Shuo et al. found that EI was associated with social support. Individuals with higher EI are likely to receive more social support (68). The results of the structural equation modeling analysis in this study suggest that EI influences social exclusion with a path coefficient of -0.67, and social exclusion influences PSMU with a path coefficient of 0.22. The results of the mediation effect test showed that the mediation effect size for social exclusion was -0.13. This suggests that individuals with higher levels of EI tend to feel lower levels of social exclusion and thus their risk of PSMU is relatively low. They can identify, perceive, understand, and experience emotions (both their own and those of others) more effectively in everyday interpersonal interactions. Consequently, they are more socialized, more likely to develop positive attitudes, and respond with appropriate emotions and behaviors, resulting in greater social support from family, friends, and other contacts. This process improves mental health, provides social support and resources, and reduces indirect exclusion (68). Individuals with high EI are adept at managing and utilizing their emotions and cultivating positive emotional states through social interactions. This emotion affects those around them, promoting real-life interactions and reducing online socialization, consistent with the connotations of emotional contagion (69, 70). Furthermore, they understood how to effectively utilize social resources when encountering difficult situations, actively participate in social interactions, and reduce social alienation. This may reduce their need for access to psychological support and help via the Internet, leading to less time spent on social networks and thereby avoiding PSMU (71, 72). Conversely, college students with low EI struggle to control their emotions, which often leads to interpersonal conflict and social exclusion, particularly direct exclusion (73). To mitigate the unpleasant experiences triggered by social exclusion, they often take measures to avoid negative situations and alleviate negative emotions (74). Social media offer a safe environment for these students to share photos, express interest, interact with their peers, and build close online friendships (75), helping them avoid the interpersonal pressures of reality and negative emotions caused by social exclusion. Over time, these behaviors can lead to PSMU. Additionally, these behaviors gradually form a conditioned reflex, leading to the failure of self-control after continuous reinforcement, thus increasing addiction to social media and exacerbating their PSMU (76).

4.4 Mediating role of experiential avoidance in the effect of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use

There was a negative correlation between EI and experiential avoidance and a positive correlation between experiential avoidance and PSMU. EI indirectly influences PSMU through experiential avoidance, supporting H2b. MacCann et al. (77) found that emotion management skills were associated with avoidant coping. Individuals with poorer emotion management had more corresponding avoidance behaviors. The results of the structural equation modeling analysis in this study showed that EI had an effect on experiential avoidance with a path coefficient of -0.30, and experiential avoidance had an effect on PSMU with a path coefficient of 0.37. The results of the mediation effect test showed that the mediation effect size for experiential avoidance was -0.12. This suggests that individuals with higher EI tend to have lower levels of experiential avoidance, and thus their risk of PSMU is relatively low.

College students with higher EI were better able to manage emotions, regulate the external expression of emotions, and improve their internal psychological adaptation levels to resolve anxiety and fear when faced with pressure, unpleasant emotional states, and psychological changes. Therefore, when faced with stress, college students with high EI do not avoid or treat it negatively but adopt an accepting attitude toward facing the problem, enhancing their psychological development and reducing the likelihood of using experiential avoidance. This is consistent with Aljarboa et al. (78), who emphasized that college students with higher EI are less likely to exhibit avoidance behaviors (78). If an individual employs inappropriate emotion-regulation strategies, it may lead to the use of coping mechanisms for vicarious avoidance. Experiential avoidance can quickly alleviate the negative experience of an undesirable situation in the short term (39) and may be helpful and adaptive when dealing with negative emotions. However, this can be harmful if it becomes habitual, such as using social media as compensation. College students use social media to escape real life and negative emotions and to compensate for realistic frustrations and a lack of interpersonal responses through online socialization. When this behavior becomes habitual, it can lead to PSMU, resulting in social media addiction, consistent with the findings of Garcia-Oliva and Piqueras (79). Quan proposed a new perspective on addiction based on the connotation of experiential avoidance: the self-centered experiential avoidance model (80). This model explains addiction as a strategy for experiential avoidance and as a way for individuals with an addiction to interact with the social dimension. This model states that experiential avoidance can flexibly modulate an individual’s addiction level, which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

4.5 Chain mediating roles of social exclusion and experiential avoidance in the effect of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use

Based on previous research (81), this study suggests that social exclusion and experiential avoidance mediate the effects of EI on PSMU. According to Bennett (81), social exclusion positively predicts experiential avoidance, suggesting chain mediation. Compared to the direct impact of EI on PSMU, the chain-mediated effect was smaller but significant. The chain-mediating role was comparable to the separate mediating roles of social exclusion and experiential avoidance and was stable in the model. The chain-mediated model used in this study supports the interaction theory of addictive behaviors proposed by the I-PACE model, which explains affective and cognitive processes as mechanisms of Internet-related disorders. EI as a core personal trait, social exclusion as an affective factor, experiential avoidance as a cognitive factor, and PSMU as a pattern of problematic behavior. College students with lower EI were less able to recognize, assess, control, and apply their emotions. Consequently, they are less likely to comprehend others’ feelings and may be prone to conflict when their emotions are unstable. This makes them more susceptible to social exclusion, leading to loneliness and loss, which encourages them to avoid social contact and develop avoidance behaviors. Once accustomed to this avoidance pattern, they fall into experiential avoidance as the first sign of frustration or rejection (41, 44), using social media as a substitute for meeting social needs in real life. This behavior eventually leads to PSMU and a potential addiction to social media. Thus, social exclusion and experiential avoidance mediate the effect of EI on PSMU, supporting H3.

The hypotheses and the theoretical model of this study (Figure 1) were validated by the results of the study. EI negatively correlates with social exclusion, experiential avoidance, and PSMU. EI indirectly affects PSMU through social exclusion (H2a) and experiential avoidance (H2b). The relationship between EI and PSMU is serially mediated by social exclusion and experiential avoidance.

This study provides an empirical basis for the I-PACE model and highlights that core personal characteristics, combined with affective and cognitive factors, may trigger specific problematic Internet use behaviors. EI positively predicts PSMU. Social exclusion and experiential avoidance partially mediate the effect of EI on PSMU. These two variables also chain-mediate the impact of EI on PSMU. PSMU is the result of the interaction of personality traits, affective responses, and cognitive processes. Based on this, the present study proposes that college students with lower EI are more likely to experience a sense of social exclusion in group life due to their limited ability to perceive and regulate emotions, which in turn stimulates the tendency of experiential avoidance to alleviate emotional distress by avoiding internal pain. Online social media has become an important way for individuals to vicariously fulfill their social needs due to its instant gratification and low-risk interaction properties, but long-term use predisposes them to PSMU. This pathway reveals the mechanisms by which personality traits (EI) influence PSMU through affective responses (feelings of social exclusion) and cognitive responses (experiential avoidance), enriching the I-PACE model’s understanding of the mechanisms by which problematic Internet use behaviors occur.

In the future, educators should focus on developing EI in college students. Methods such as campus activities, themed class meetings, psychology classes, psychological counseling, and group counseling can help college students recognize and manage their emotions when they encounter difficulties, cultivate positive interpersonal relationships, and perceive the support of others, thereby reducing social exclusion. Consequently, college students may be less likely to engage in avoidance behaviors, effectively preventing PSMU. In future research, targeting internet addiction among college students, especially Reducing PSMU and improving mental health among college students can begin with increasing EI and reducing social exclusion and experiential avoidance among college students.

4.6 Limitations and future directions

This study has some limitations. First, although the participants were widely distributed, with 1,448 students enrolled in nine colleges and universities in Chengdu, Beijing, Shanghai, and Kunming, all were college students; thus, the sample was relatively homogeneous. Further research is necessary to determine whether the mechanisms of action of the study variables can be extrapolated to other groups. Future research should use samples from other age groups to address sample bias. Second, the questionnaires were administered independently. Participants may have been affected by the social approval effect when completing the questionnaire. Clinical assessments or event sampling should be used in future studies to gather information, as this will significantly reduce retrospective bias and enhance ecological validity. Third, In addition, the correlational nature of this study should be acknowledged as a limitation. Although significant associations were found among the variables, the cross-sectional and non-experimental design does not allow for causal inferences. Future research using longitudinal or experimental methods is needed to further clarify the factors that influence and shape PSMU mechanisms.

5 Conclusion

This study provides an empirical basis for the I-PACE model and highlights that core personal characteristics, in combination with affective and cognitive factors, may trigger specific problematic Internet use behaviors. The conclusions of this study are as follows: First, EI directly predicted PSMU. Second, social exclusion mediates the effects of EI on PSMU. Third, experiential avoidance mediated the impact of EI on PSMU. Finally, the social exclusion and experiential avoidance chains mediated the effect of EI on PSMU.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Review Committee of Chengdu Medical College (approval number: 2021NO.07). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. XMY: Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZC: Writing – review & editing. XY: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Chengdu Medical College and other collaborating institutions for supporting study participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this study was conducted without commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1567060/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary File S1Research Questionnaire. (PDF).

Supplementary File S2Raw Data. (EXCEL).

Abbreviations

PSMU, Problematic Social Media Usage; EI, Emotional intelligence; SE, Social exclusion; EA, Experiential avoidance; VI, Viscosity increase; PD, Physiological damage; OA, Omission anxiety; CF, Cognitive failure.

References

1

Dixon S . Social media – Statistics & facts. New York, USA: Statista Inc. (2017). Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks/ (Accessed October 12, 2022).

2

China Internet Network Information Center . China Internet Network Information Center releases the 53rd statistical report on Internet development in China Vol. 33. Beijing, China: National Library (2024). p. 104.

3

Cheng S Bi R Wang J . Young and old social media users “surf” and “treat water. China Youth Daily. (2022).

4

Arslan G Yıldırım M Zangeneh M . Coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment in college students: Exploring the role of college belongingness and social media addiction. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2022) 20:1546–59. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00460-4

5

Gentile B Twenge JM Freeman EC Campbell WK . The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Comput Hum Behav. (2012) 28:1929–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.012

6

Rasmussen EE Punyanunt-Carter N Lafreniere JR Norman MS Kimball TG . The serially mediated relationship between emerging adults’ social media use and mental well-being. Comput Hum Behav. (2020) 102:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.019

7

Lee S Lohrmann DK Luo J Chow A . Frequent social media use and its prospective association with mental health problems in a representative panel sample of US adolescents. J Adolesc Health. (2022) 70:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.11.029

8

Billieux J Maurage P Lopez-Fernandez O Kuss DJ Griffiths MD . Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr Addict Rep. (2015) 2:156–62. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

9

Andreassen CS . Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Curr Addict Rep. (2015) 2:175–84. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

10

Jiang YZ Bai XL AL Liu Y Li M Liu G . Problematic social networks usage of adolescent. Adv Psychol Sci. (2016) 24:1435–47. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.01435

11

Jiang YZ . Development of a questionnaire for assessing problematic mobile social media use among adolescents. Psychol Technol Appl. (2018) 6:613–21. doi: 10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2018.10.004

12

Williams MK Lewin KM Meshi D . Problematic use of five different social networking sites is associated with depressive symptoms and loneliness. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:20891–8. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05925-6

13

Keles B McCrae N Grealish A . A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth. (2019) 25:1–15. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

14

Alonzo R Hussain J Stranges S Anderson KK . Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2021) 56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

15

Wong HY Mo HY Potenza MN Chan MNM Lau WM Chui TK et al . Relationships between severity of Internet gaming disorder, severity of problematic social media use, sleep quality and psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1879. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061879

16

Zeeni N Doumit R Abi Kharma J Sanchez-Ruiz MJ . Media, technology use, and attitudes: Associations with physical and mental well-being in youth with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2018) 15:304–12. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12298

17

Hussain Z Griffiths MD . The associations between problematic social networking site use and sleep quality, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, anxiety and stress. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 19:686–700. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00175-1

18

Brand M Young KS Laier C Wölfling K Potenza MN . Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2016) 71:252–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

19

Brand M Wegmann E Stark R Müller A Wölfling K Robbins TW et al . The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 104:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

20

Kardefelt-Winther D . A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. (2014) 31:351–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

21

Alshakhsi S Chemnad K Almourad MB Altuwairiqi M Mcalaney J Ali R . The impact of objectively recorded smartphone usage and emotional intelligence on problematic Internet usage. J Adv Inf Technol. (2023) 14:85–93. doi: 10.12720/jait.14.1.85-93

22

Wang Y . A study on the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Emotional Intelligence Scale. Changsha, China: Central South University, (2010).

23

Ruiz-Aranda D Extremera N Pineda-Galán C . Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and subjective happiness in female student health professionals: The mediating effect of perceived stress. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2014) 21:106–13. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12052

24

Urquijo I Extremera N Villa A . Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being in graduates: The mediating effect of perceived stress. Appl Res Qual Life. (2015) 11:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11482-015-9432-9

25

Kircaburun K Demetrovics Z Griffiths MD Király O Kun B Tosuntaş ŞB . Trait emotional intelligence and internet gaming disorder among gamers: The mediating role of online gaming motives and moderating role of age groups. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2020) 18:1446–57. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00179-x

26

Kircaburun K Griffiths MD Billieux J . Trait emotional intelligence and problematic online behaviors among adolescents: The mediating role of mindfulness, rumination, and depression. Pers Individ Dif. (2019) 139:208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.024

27

Sechi C Loi G Cabras C . Addictive internet behaviors: The role of trait emotional intelligence, self-esteem, age, and gender. Scand J Psychol. (2021) 62:409–17. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12698

28

Barberis N Sanchez-Ruiz MJ Cannavò M Calaresi D Verrastro V . The dark triad and trait emotional intelligence as predictors of problematic social media use and engagement: The mediating role of the fear of missing out. Clin Neuropsychiatry. (2023) 20:129–40. doi: 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20230205

29

Calaresi D Cuzzocrea F Saladino V Verrastro V . The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and problematic social media use. Youth Society. (2025) 57:515–35. doi: 10.1177/0044118X241273407

30

Baghcheghi N Koohestani HR . The predictive role of tendency toward mobile learning and emotional intelligence in Internet addiction in healthcare professional students. J Adv Med Educ Prof. (2022) 10:113–9. doi: 10.30476/.2022.91971.1465

31

Wu HJ Zhang SY Zeng YQ . Development and reliability test of the Social Exclusion Questionnaire for college students. China J Health Psychol. (2013) 21:1829–31. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2013.12.012

32

Hidalgo-Fuentes S Martínez-Álvarez I Sospedra-Baeza MJ Martí-Vilar M Merino-Soto C Toledano-Toledano F . Emotional intelligence and perceived social support: Its relationship with subjective well-being. Healthc (Basel Switzerland). (2024) 12:634. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12060634

33

Dwivedi A Lewis C . How millennials’ life concerns shape social media behaviour. Behav Inf Technol. (2021) 40:1467–84. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2020.1760938

34

Elhai JD Tiamiyu M Weeks J . Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: The prominent role of rumination. Internet Res. (2018) 28:315–32. doi: 10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0019

35

Li Q Chen T Zhang S Gu C Zhou Z . The mediating role of intentional self-regulation in the constructive and pathological compensation processes of problematic social networking use. Addictive Behav. (2025) 160:108188. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.108188

36

Cao J Ji Y Zhu ZH . Reliability and validity of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ). 2nd ed. Chinese version for college students. Chin J Ment Health. (2013) 27:873–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000–6729

37

Luoma JB Pierce B Levin ME . Experiential avoidance and negative affect as predictors of daily drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. (2020) 34:421–33. doi: 10.1037/adb0000554

38

Rochefort C Baldwin AS Chmielewski M . Experiential avoidance: An examination of the construct validity of the AAQ-II and MEAQ. Behav Ther. (2018) 49:435–49. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.08.008

39

Di Giuseppe KD Taylor AJG . Investigating how intolerance of uncertainty and emotion regulation predict experiential avoidance in non-clinical participants. Psychol Stud. (2021) 66:181–90. doi: 10.1007/s12646-021-00602-1

40

Reed P Haas W . Social media use as an impulsive “escape from freedom. Psychol Rep. (2023) 128:1824–1838. doi: 10.1177/00332941231171034

41

Wang J Wang N Liu Y Zhou Z . Experiential avoidance, depression, and difficulty identifying emotions in social network site addiction among Chinese university students: a moderated mediation model. Behav Inf Technol. (2025), 1–14. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2025.2455406

42

Twenge JM Catanese KR Baumeister RF . Social exclusion and the deconstructed state: Time perception, meaninglessness, lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2003) 85:409–23. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409

43

Yi Z Wang W Wang N Liu Y . The relationship between empirical avoidance, anxiety, difficulty describing feelings and internet addiction among college students: A moderated mediation model. J Genet Psychol. (2025), 1–17. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2025.2453705

44

Poon KT . Unpacking the mechanisms underlying the relation between ostracism and Internet addiction. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 270:724–30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.056

45

Wong CS Law KS . The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude. Leadersh Q. (2002) 13:243–74. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

46

Di M Deng X Zhao J Kong F . Psychometric properties and measurement invariance across sex of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale in Chinese adolescents. psychol Rep. (2022) 125:599–619. doi: 10.1177/0033294120972634

47

Wang Y Kong F . The role of emotional intelligence in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and mental distress. Soc Indic Res. (2014) 116:843–52. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0327-6

48

Shi J Wang L . Validation of emotional intelligence scale in Chinese university students. Pers Individ Differ. (2007) 43:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.012

49

Law KS Wong CS Song LJ . The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. J Appl Psychol. (2004) 89:483–96. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

50

Bond FW Hayes SC Baer RA Carpenter KM Guenole N Orcutt HK et al . Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther. (2011) 42:676–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

51

Sun LR . Principles and operations of structural equation modeling (SEM). J Ningbo Univ (Educ Sci Ed). (2005) 27:31–34+43.

52

Wen ZL Hou JT Marsh H . Structural equation modeling: Fit indices and chi-square criteria. J Psychol. (2004) 36:186–94.

53

Podsakoff PM MacKenzie SB Lee JY Podsakoff NP . Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

54

Hayes AF Scharkow M . The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol Sci. (2013) 24:1918–27. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187

55

Lev-Wiesel R Sternberg R . Victimized at home revictimized by peers: Domestic child abuse a risk factor for social rejection. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. (2012) 29:203–20. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0258-0

56

Freedman G Fetterolf JC Beer JS . Engaging in social rejection may be riskier for women. J Soc Psychol. (2019) 159:575–91. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2018.1532388

57

Saraiva J Esgalhado G Pereira H Monteiro S Afonso RM Loureiro M . The relationship between emotional intelligence and Internet addiction among youth and adults. J Addict Nurs. (2018) 29:13–22. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000209

58

Tommasi M Sergi MR Picconi L Saggino A . The location of emotional intelligence measured by EQ-I in the personality and cognitive space: Are there gender differences? Front Psychol. (2022) 13:985847. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.985847

59

Munsamy K Walker S McHugh L . Repetitive negative thinking mediates the relationship between experiential avoidance and emotional distress among South African university students. S Afr J Psychol. (2023) 53:377–88. doi: 10.1177/00812463231186340

60

Primack BA Shensa A Sidani JE Escobar-Viera CG Fine MJ . Temporal associations between social media use and depression. Am J Prev Med. (2021) 60:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.014

61

Lopes LS Valentini JP Monteiro TH Costacurta MCF Soares LON Telfar-Barnard L et al . Problematic social media use and its relationship with depression or anxiety: A systematic review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2022) 25:691–702. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2021.0300

62

Lin S Yuan Z Niu G Fan C Hao X . Family matters more than friends on problematic social media use among adolescents: mediating roles of resilience and loneliness. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2023) 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11469-023-01026-w

63

Alshakhsi S Chemnad K Almourad MB Altuwairiqi M McAlaney J Ali R . Problematic internet usage: The impact of objectively recorded and categorized usage time, emotional intelligence components and subjective happiness about usage. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e11055. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11055

64

Marino C Gini G Angelini F Vieno A Spada MM . Social norms and e-motions in problematic social media use among adolescents. Addict Behav Rep. (2020) 11:100250. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100250

65

Ainslie G . Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychol Bull. (1975) 82:463–96. doi: 10.1037/h0076860

66

Kotsou I Mikolajczak M Heeren A Grégoire J Leys C . Improving emotional intelligence: A systematic review of existing work and future challenges. Emot Rev. (2019) 11:151–65. doi: 10.1177/1754073917735902

67

Bruno F Lau C Tagliaferro C Marunic G Quilty LC Liuzza MT et al . Effects of cancer severity on the relationship between emotional intelligence, perceived social support, and psychological distress in Italian women. Support Care Cancer. (2024) 32:142. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08346-0

68

Shuo Z Xuyang D Xin Z Xuebin C Jie H . The relationship between postgraduates’ emotional intelligence and well-being: The chain mediating effect of social support and psychological resilience. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:865025. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865025

69

Hua Y Miao X . Emotional intelligence and job burnout among secondary school teachers: the serial mediating roles of perceived social support and subjective well-being. Appl Educ Psychol. (2025) 6:168–176. doi: 10.23977/appep.2025.060124

70

Zhang L Roslan S Zaremohzzabieh Z Jiang Y Wu S Chen Y . Perceived stress, social support, emotional intelligence, and post-stress growth among Chinese left-behind children: A moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1851. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031851

71

Chen S . Chinese adolescents’ emotional intelligence, perceived social support, and resilience-the impact of school type selection. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1299. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01299

72

Diao K Wang J Zhang Y Huang Y Shan Y . The mediating effect of personal mastery and perceived social support between emotional intelligence and social alienation among patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1392224. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1392224

73

Parent-Lamarche A Saade S . Interpersonal conflict and psychological well-being at work: The beneficial effects of teleworking and emotional intelligence. Int J Confl Manage. (2024) 35:547–66. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-06-2023-0117

74

López Hernández G . ‘We understand you hate us’: Latinx immigrant-origin adolescents’ coping with social exclusion. J Res Adolesc. (2022) 32:533–51. doi: 10.1111/jora.12748

75

Yıldız Durak H . Modeling of variables related to problematic internet usage and problematic social media usage in adolescents. Curr Psychol. (2020) 39:1375–87. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9840-8

76

Seong Y Hyun MH . The mediating effect of experiential avoidance on the relationship between undergraduate students’ motives for using SNS and SNS addiction tendency: Focused on Facebook. Korean J Str Res. (2016) 24:257–63. doi: 10.17547/kjsr.2016.24.4.257

77

MacCann C Double KS Clarke IE . Lower avoidant coping mediates the relationship of emotional intelligence with well-being and ill-being. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:835819. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835819

78

Aljarboa BE Pasay An E Dator WLT Alshammari SA Mostoles R Jr. Uy MM et al . Resilience and emotional intelligence of staff nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc (Basel Switzerland). (2022) 10:2120–2120. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10112120

79

García-Oliva C Piqueras JA . Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. J Behav Addict. (2016) 5:293–303. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.041

80

Quan H . New insight of addiction: Experiential avoidance theory centered on the self-concept. Front Soc Sci. (2016) 5:552–61. doi: 10.12677/ASS.2016.54077

81

Bennett RJ Saulsman L Eikelboom RH Olaithe M . Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: A qualitative investigation using Leventhal’s self-regulation theory. Int J Audiol. (2022) 61:353–64. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1933620

Summary

Keywords

emotional intelligence, social exclusion, experiential avoidance, problematic social media use, internet addiction, college students

Citation

Guan H, Peng S, Liu Z, Sun H, Wu H, Yao X, Chen Z and Yang X (2025) Effect of emotional intelligence on problematic social media use among Chinese college students: mediating role of social exclusion and experiential avoidance. Front. Psychiatry 16:1567060. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1567060

Received

08 February 2025

Accepted

19 May 2025

Published

03 June 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Yuke Tien Fong, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Reviewed by

Olimpia Pino, University of Parma, Italy

Jing Li, Sichuan University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Guan, Peng, Liu, Sun, Wu, Yao, Chen and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zi Chen, Zi2116@hotmail.com; Xi Yang, yangxi@cmc.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.