- Unit of Epidemiological Psychiatry and Digital Mental Health, IRCCS Istituto Centro San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli, Brescia, Italy

Psychosocial disabilities refer to a range of mental health conditions that significantly impact an individual’s ability to function in daily life and participate fully in society. Across Europe, individuals with these conditions face systemic barriers, including inadequate support services, stigma, and limited healthcare access. This perspective article examines these challenges through the lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Saraceno’s community psychiatry framework. By analyzing identified key pillars of psychosocial disability - housing, social inclusion, employment, healthcare access, service organization, and stigma – this article underscores the necessity of targeted interventions to promote dignity, autonomy, and recovery for individuals with psychosocial disabilities across Europe. Stable housing is foundational for recovery, social integration, and employment. Social inclusion and meaningful employment are essential for psychological well-being, though stigma and discrimination remain a major obstacle. Employment programs are crucial for fostering social reintegration. Healthcare access, already fragmented, can be obstacolated by stigma in healthcare settings as an additional barrier. Positive organizational culture in mental health services, emphasizing co-production and shared decision-making, is vital for recovery and healthcare access. This article highlights how key pillars of psychosocial disability are strongly interrelated, with each significantly influencing the others. The reciprocal impact among these elements demonstrates that improvements or setbacks in one area inevitably affect the others, creating either a reinforcing cycle of support or a compounding negative effect. Coordinated efforts and comprehensive strategies are essential to integrating these pillars and overcoming barriers to psychosocial disability across Europe.

Introduction

Psychosocial disabilities refer to mental health conditions that significantly impact an individual’s ability to function in daily life, including work, education, social relationships and self-care, ultimately affecting full participation in society (1–3). Due to these challenges, individuals with psychosocial disability require comprehensive care that includes medical, social, and community support. Conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and other severe mental disorders can impair independent living and societal participation (4–6). Approximately 84 million people in the WHO European Region experience psychosocial disabilities (3). Across Europe, these individuals encounter numerous systemic barriers that compound their challenges, including inadequate support services, persistent stigma, and limited access to healthcare. These challenges are multifaceted and exist at multiple levels, from individual to societal (2, 7, 8).

The objective of this perspective article is to analyze the systemic barriers faced by individuals with psychosocial disabilities in Europe across six key pillars: housing, social inclusion, employment, healthcare access, organizational culture in mental health services, stigma and discrimination.

A theoretical analysis of psychosocial disabilities in Europe will be presented by applying Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (9) and Saraceno’s community psychiatry framework (10) to explore these challenges. Maslow’s model (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model) emphasizes the necessity of meeting basic physiological and safety needs before individuals can achieve personal growth and societal contribution. Saraceno’s work in community psychiatry underscores the interconnectedness of essential life domains—family, work, and housing—in promoting mental health and social well-being. By applying Maslow’s and Saraceno’s models, the article aims to demonstrate how addressing these intertwined pillars can improve recovery, enhance social participation, and support the overall well-being of individuals with psychosocial disabilities.

Housing

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs places shelter and security among the most fundamental requirements for human well-being (9). For individuals with psychosocial disabilities, stable housing is essential, as it supports the fulfillment of higher-order needs like social belonging and self-esteem.

Without safe housing, individuals struggle to meet basic needs, hindering personal growth and societal participation. Secure housing reduces the psychological stress associated to mental health conditions and mitigates the heightened risk of homelessness, which can exacerbate existing challenges and impede recovery. Thus, stable housing is vital for mental health and recovery (1, 7, 11, 12). Saraceno’s work further underscores the centrality of housing in recovery, emphasizing its role as a foundation for fostering social connections, supporting employment, and building pathways toward community integration (10).

Despite the importance of housing, significant disparities persist across Europe. The average number of psychiatric beds across inpatient units (psychiatric hospitals, mental health units in general hospitals, forensic facilities, community residential housing, and child/adolescent facilities) is 93 per 100,000 inhabitants, but this varies widely. In low-income countries, mental hospitals are nearly twice as large as those in high-income countries, with a median of 300 beds compared to 166. In low-income countries, the number of mental hospital beds ranges from 28 to 40 per 100,000 inhabitants. In contrast, high-income countries have the highest bed rates in psychiatric units within general hospitals (22 per 100,000 inhabitants) and in mental health community residential housing (60 per 100,000 inhabitants) (13). Notably, Italy and Iceland are the only European countries where psychiatric hospitals have been fully eliminated (14). As a result, many individuals with psychosocial disabilities remain in psychiatric hospitals rather than being integrated into their communities.

Community residential housing provides long-term or transitional living for individuals with mental health conditions, offering support, independence, and access to care from mental health professionals. In this context, Italy and England are the only countries that have developed robust mental health supported accommodation services that promote independent living. These services follow a progressive care model, where individuals gradually transition from higher to lower levels of support as they acquire skills for independent living and societal participation. This approach ensures individuals receive appropriate support tailored to their specific needs, with the goal of moving on to less supported or fully independent housing over time. While this model offers tailored support and clear goals for both staff and service users, it also requires individuals to move homes as they progress in their recovery (15, 16).

Italy, often celebrated as a pioneer of deinstitutionalization thanks to the contributions of Basaglia and the movement he inspired, exemplifies both progress and ongoing challenges (14). Basaglia’s efforts led to the closure of Italy’s psychiatric hospitals with the enactment of Law 180/1978, which dismantled institutional care in favor of community-based services (17, 18). This shift to community-based care aligns with principles championed by figures like Erving Goffman and global initiatives such as the WHO’s QualityRights Toolkit (19, 20). However, even in Italy, the deinstitutionalization process remains a work in progress (14). Recent evaluations of supported accommodation services in Italy using the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care - Supported Accommodation (QuIRC-SA) tool (21, 22) revealed areas for improvement. This comprehensive tool assesses care quality across seven domains, with higher scores indicating better outcomes. The overall mean QuIRC-SA score across facilities was 52.3% (SD = 9.3) with particularly low scores in key domains such as Social Interface (48.6%, SD = 11.4) and Recovery-Based Practices (45.8%, SD = 9.1) (23). However, the QuIRC-SA domain scores for Italian supported accommodation services were lower than those of a national sample from England, except for the Treatments and Interventions domain, which was >2% higher. The mean score for England was 69.2%, with a range from 55.1% (SD = 8.4) to 86.7% (SD = 5.0), which is the only other sample for which QuIRC-SA data has been published to date (24).

Countries like The Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark have made significant progress in balancing institutional and community-based services, and are developing alternatives such as supported accommodations and using the “Housing First” approach, enabling individuals with psychosocial disabilities to live independently and participate fully in society (14, 25, 26).

These findings underscore the need for sustained investment in rehabilitative housing programs that prioritize not only physical shelter but also social reintegration and recovery-focused practices. Political commitment is essential to reduce institutionalization and promote a human rights-based approach to housing for individuals with psychosocial disabilities.

Social inclusion

Maslow’s model highlights the importance of belonging and social connection for psychological well-being (9). Saraceno further emphasized that supportive social networks mitigate isolation and promote resilience (10). Social inclusion fosters a sense of identity, purpose, and connection, which are essential for recovery (8, 27). Despite these insights, individuals with psychosocial disabilities often face stigma and discrimination, leading to social isolation and diminished self-worth (28).

Data from Eurostat indicate that in 2022, people with disabilities in the EU had lower participation rates in cultural activities, sporting events, and voluntary work compared to those without disabilities. For example, only 10.3% of people with disabilities participated in formal voluntary activities, compared to 13.0% of those without disabilities. The highlighted disabilities gap varies significantly by country. In 2022, the percentage of people (16 and older) who visited the cinema, attended a live performance, or explored a cultural site in the past year was the highest in Luxembourg (77.6%) and Denmark (77.1%) and the lowest in Romania (22.2%) and Bulgaria (19.7%). Romania had the biggest gap, where 28.3% of people without disabilities took part in cultural activities, compared to just 7.1% of those with disabilities. In 2022, the percentage of people (16+) meeting with family at least once a year ranged from 93.6% in Estonia to 99.4% in Poland and Romania. In most EU countries, people with disabilities were less likely to do so, except in Cyprus, where their rate was 1.8 percentage points (pp) higher. The largest disability gap was in Estonia (6.6 pp). Women were generally more likely than men to meet family. For meeting friends at least once a year, the rates varied more, from 78.5% in Latvia to over 98% in Denmark, Cyprus, Greece, Croatia, and Bulgaria. Again, people with disabilities participated less, with the biggest gaps in Malta (20.9 pp), Estonia (20.1 pp), and Latvia (18.2 pp). Unlike family gatherings, men were more likely than women to meet friends. Participation in voluntary activities also showed a disability gap. In 2022, 12.3% of EU citizens took part in formal volunteering (10.3% for people with disabilities, 13% for those without). Informal volunteering had a smaller gap (13.3% vs. 14.7%). Active citizenship (e.g., political activities) was reported by 7.4% of people with disabilities and 8.4% of those without. Gender gaps in volunteering and civic activities were minor, but disability gaps varied by age. Younger people with disabilities had higher participation rates than their peers without disabilities, while older individuals (65+) with disabilities participated significantly less than their non-disabled counterparts (29). This variability suggests that while there are common challenges, specific conditions and policies differ widely across Europe (30). However, there is a lack of specific, detailed data on psychosocial disabilities across Europe. This is partly due to the absence of a unified definition of disability and inconsistent data collection methods across countries.

Across Europe, various initiatives have been introduced to boost community involvement for individuals with psychosocial disabilities and support their independence. These include cultural, educational, and recreational programs, as well as peer support networks (31), that have proven effective in reducing stigma and fostering inclusive environments (32, 33). Family education programs (34, 35), such as those implemented in the United Kingdom, help build empathy and understanding, creating nurturing environments that support recovery (31, 36–40).

Employment

Meaningful work fulfills higher-level needs in Maslow’s hierarchy, contributing to self-esteem and self-actualization (9). Saraceno’s work emphasized the reciprocal relationship between employment and mental health, noting that meaningful work reduces stress and enhances social participation (10). However, workplace discrimination and misconceptions about the capabilities of individuals with psychosocial disabilities continue to limit employment opportunities (41, 42).

Individuals with disabilities, including those with psychosocial disabilities, face higher risks of poverty and social exclusion. In the EU, nearly 30% of people with disabilities live in poverty, which is significantly higher than those without disabilities (43). The economic burden of mental health disorders in the EU is substantial, accounting for up to 4% of GDP annually, or over €600 billion (44). In Europe, only 10% to 20% of people with severe mental disorder are employed, and they are twice as likely to lose their jobs after the onset of their condition (45–47). From 2014 to 2022, the employment gap between individuals with and without disabilities in the EU27 averaged between 22.7 and 21.4 percentage points. This gap varies significantly across EU countries, with Ireland having one of the largest at nearly 40 percentage points, while Luxembourg has one of the smallest at 8.5 percentage points. Belgium, Bulgaria, and Croatia also experience substantial disparities (48). People with psychosocial disability living in community residential housing or supported accommodation face even greater challenges in finding employment. For example, in Italy, 75.5% of residents in supported accommodation services are unemployed (23, 49).

Supported employment programs, social enterprises, and models like Individual Placement, Support (IPS) and Clubhouse have demonstrated success in improving employment outcomes and supporting people with psychosocial disability in their recovery (50–52). In the WHO European Region, 91% of countries have reported having at least one stand-alone mental health policy or plan related to social protection, employment, education, or other areas (40).

The economic and social benefits of inclusive employment cannot be overstated—reducing economic insecurity, fostering social connections, and promoting mental well-being (39, 53, 54).

Healthcare access

Access to healthcare is a critical pillar for individuals with psychosocial disabilities. Maslow’s model underscores the importance of health and safety (9), while Saraceno’s work highlights the need for integrated and community-based mental health services (10). Despite efforts to improve healthcare access, barriers persist across Europe (40).

Although mental health services and psychotropic medicines in the WHO European Region are fully covered in 100% and 98% of cases or require at most a 20% co-payment (40), many individuals still struggle to receive care. Stigma, discrimination in healthcare settings, and social factors—such as precarious employment and broader societal biases—often discourage individuals from seeking help. These challenges not only affect mental health but also hinder access to integrated care, worsening inequalities and health outcomes (31).

To address these issues, Global Target 2.3 of the Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (54) aims for 80% of countries to integrate mental health into primary healthcare by 2030. This initiative promotes a shift from long-stay mental hospitals to community-based care. In the WHO European Region, 74% of countries have reported having guidelines for this integration, with pharmacological interventions in 71% and psychosocial interventions in 30%. Additionally, government social support for individuals with mental health conditions varies widely across WHO European countries, ranging from 2% to 50%. Despite this effort, health systems across Europe still struggle to meet the demand for mental health care. Between 35% to 50% of individuals with severe mental disorders in high-income countries go untreated, while the gap is likely even wider in lower-income regions (40). Stigma within healthcare settings and fragmented care systems further prevent individuals from receiving comprehensive treatment (31).

Ensuring that mental health care is affordable, accessible, and culturally sensitive is essential for promoting recovery and reducing health disparities (54–56).

Organizational culture

Saraceno’s emphasis on the organizational culture of mental health services underscores its critical role in shaping recovery outcomes (10). Positive organizational environments foster collaboration, respect, and shared decision-making between professionals, patients, and families. In contrast, hierarchical and rigid systems often hinder engagement and recovery. A shift toward recovery-oriented practices that prioritize personal goals and autonomy is essential (57–59). Co-production models, where individuals with lived experience collaborate in service design and delivery, have shown promise in fostering more inclusive and effective care environments (4, 60). Identifying European countries adopting recovery-oriented practices is complex due to overlaps with broader mental health strategies. While many demonstrate commitment, implementation varies based on contextual and resource factors. Sustained efforts are crucial for accessible, recovery-focused care (42, 61–63).

Stigma

Despite Maslow and Saraceno not directly addressing stigma and discrimination, their models cannot be fully realized without tackling these barriers. Stigma and discrimination must be addressed to fully realize the potential of Maslow and Saraceno’s models. These barriers hinder access to services, reduce employment opportunities, and contribute to social exclusion (28, 64, 65). Despite international frameworks like the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) advocating for the elimination of stigma (8), progress remains insufficient (31).

Stigma and discrimination surrounding mental health persist in many European countries, hindering individuals from seeking help (44). Around a quarter (24.7%) of respondents across the EU-27 reported difficulty speaking to a person with a significant mental disorder, indicating a significant social distance (66).

Initiatives like the International Study of Discrimination and Stigma Outcomes (INDIGO) Network projects emphasize the need for public awareness, anti-discrimination laws, and better training for mental health professionals (67).

Discussion

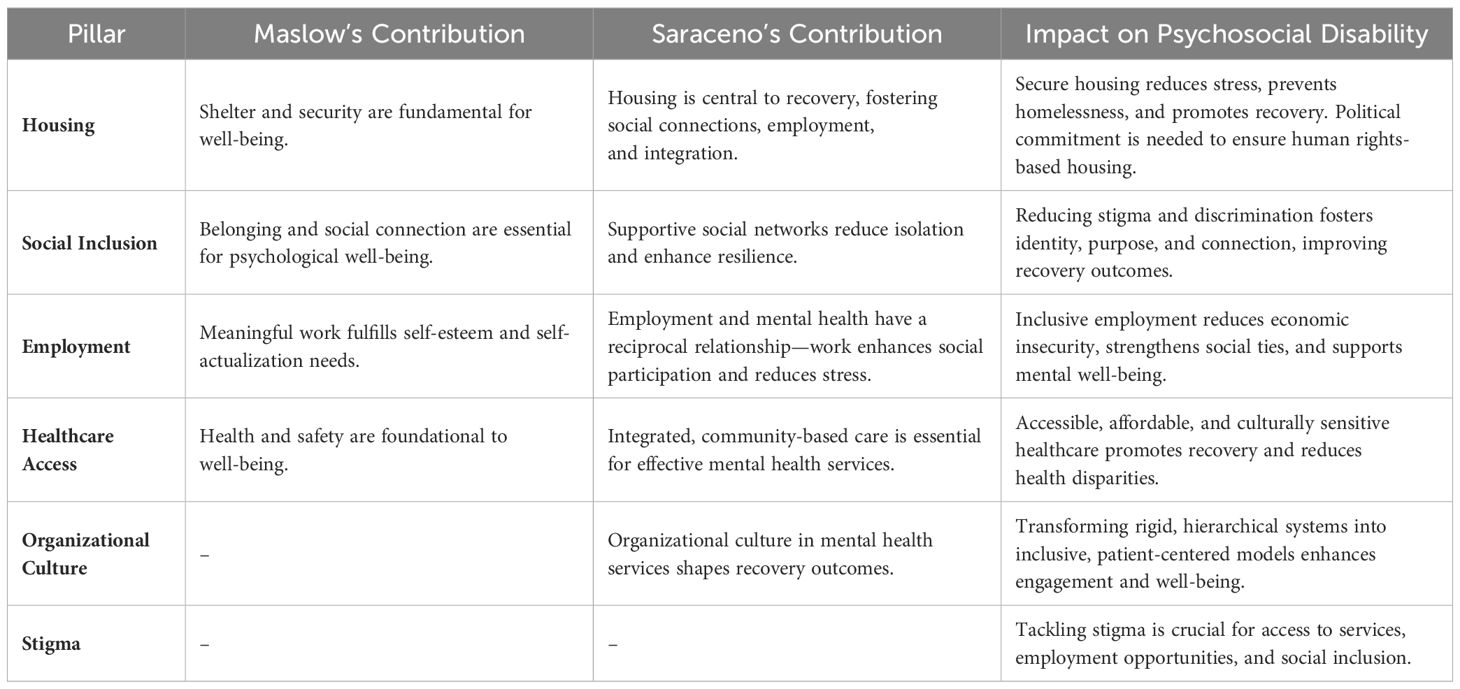

This article seeks to analyze the systemic barriers faced by individuals with psychosocial disabilities in Europe, focusing on six key pillars: housing, social inclusion, employment, healthcare access, organizational culture, and stigma. By applying Maslow’s and Saraceno’s models, the findings underscore how these key pillars are strongly interrelated, with each significantly influencing the others, reinforcing the necessity of integrated interventions. The reciprocal impact among these elements demonstrates that improvements or setbacks in one area inevitably affect the others, either fostering a reinforcing cycle of support or exacerbating existing challenges. For example, stable housing provides a foundation for employment and social inclusion, while access to meaningful work enhances self-esteem and promotes financial independence, reducing economic and psychological stress. Similarly, healthcare access is vital for managing mental health conditions, yet stigma and fragmented services often prevent individuals from seeking the care they need, ultimately affecting their ability to participate in society. Table 1 illustrates how integrating Maslow’s and Saraceno’s models into policy and practice can create a comprehensive framework for addressing these barriers in a structured approach and fostering long-term recovery. Maslow’s model emphasizes the progression from basic needs to self-actualization, reinforcing the importance of housing, employment, and healthcare as foundational to recovery. Saraceno’s contributions further stress the significance of social inclusion, community-based care, and supportive environments in fostering autonomy and dignity.

Table 1. Integration of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Saraceno’s recovery model to address psychosocial disability.

Furthermore, the interconnected pillars shape recovery, social participation, and overall well-being and their development requires integrated policies and interventions. Governments, healthcare systems, and communities must collaborate to invest in rehabilitative housing, inclusive employment, and community-based mental health services. Reducing stigma requires systemic reforms and public awareness efforts to foster inclusion.

Future research should assess the long-term impact of policies based on Maslow’s and Saraceno’s models, evaluating their effectiveness in employment, social participation, and mental health outcomes. Comparative studies across European regions can help identify adaptable best practices.

By refining and applying the models of Maslow and Saraceno, it becomes evident that addressing the pillars of psychosocial disability is essential for fostering recovery, independence, and dignity. Housing, social inclusion, employment, healthcare access, organizational culture, and stigma are interconnected domains that require sustained investment and collaboration among governments, healthcare systems, and communities. Only through such a holistic approach can we create a society where individuals with psychosocial disabilities can thrive, free from discrimination and exclusion.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with American Psychiatric Association (1992) ethical standards for the treatment of human volunteers; each participant provided consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The study has been approved by the ethical committees (Ecs) of the three main participating centers: EC of IRCCS Istituto Centro San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli (31/07/2019; no. 211/2019), EC of Area Vasta Emilia Nord (25/09/2019; no. 0025975/19), and EC of Pavia (02/09/2019, no. 20190075685), and by the ethical committees of all participating institutions. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. DACSSA Disability Advocacy. Psychosocial Disability. (2024) Australia. Available at: https://dacssa.org.au/ (Accessed December 12, 2024).

2. Reed GM. What’s in a name? Mental disorders, mental health conditions and psychosocial disability. World Psychiatry. (2024) 23:209–10. doi: 10.1002/wps.21190

3. WHO Europe. The WHO European Framework for action to achieve the highest attainable standard of health for persons with disabilities 2022–2030. (2022) (Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe).

4. Liberman RP. Recovery from disability: manual of psychiatric rehabilitation. J Nervous Ment Dis. (2007) 197. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a5ae72

5. Rizvi A, Safwi SR, Usmani MA. Schizophrenia: disability, clinical insights, and management. In: The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2024). p. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-40858-8_119-1

6. WHO. Helping people with severe mental disorders live longer and healthier lives. (2017) (Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization).

7. European Council of the European Union. Disability in the EU: facts and figures. (2024). Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/disability-eu-facts-figures/ (Accessed January 10, 2025).

8. United Nations. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations General Assembly A/61/611 (2006). Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=61 (Accessed May 05, 2018).

11. Muir K, Fisher K, Abello D, Dadich A. [amp]]lsquo;I didn’t like just sittin’ around all day’: Facilitating Social and Community Participation Among People with Mental Illness and High Levels of Psychiatric Disability. J Soc Policy. (2010) 39:375–39. doi: 10.1017/S0047279410000073

12. Pevalin D, Reeves A, Baker E, Bentley R. The impact of persistent poor housing conditions on mental health: A longitudinal population-based study. Prev Med. (2017) 105:304–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.09.020

13. WHO. Mental Health Atla. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse World Health Organization (2018).

14. Taylor Salisbury T, Killaspy H, King M. An international comparison of the deinstitutionalisation of mental health care: Development and findings of the Mental Health Services Deinstitutionalisation Measure (MENDit). BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0762-4

15. Killaspy H. Supported accommodation for people with mental health problems. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:74–5. doi: 10.1002/wps.20278

16. Martinelli A, Iozzino L, Ruggeri M, Marston L, Killaspy H. Mental health supported accommodation services in England and in Italy: a comparison. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:1419–27. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01723-9

17. Camera dei deputati ed il Senato della Repubblica. LEGGE 13 maggio 1978, n. 180 Accertamenti e trattamenti sanitari volontari e obbligatori. (GU Serie Generale n.133 del 16-05-1978) Rome, Italy.

19. Funk M, Drew N. WHO QualityRights: transforming mental health services. Lancet Psychiatry. (2017) 4:826–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30271-7

20. Goffman E. Asylums Le istituzioni totali: i meccanismi dell’esclusione e della violenza. Bologna, Italy: Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi (2010).

21. Killaspy H, White S, Dowling S, Krotofil J, Mcpherson P, Sandhu S, et al. Adaptation of the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC) for use in mental health supported accommodation services (QuIRC-SA). BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0799-4

22. Martinelli A. QuIRC-SA versione italiana. QuIRC/QuIRC-SA Website. (2019). Available at: https://quirc.eu/quirc-sa/ (Accessed January 10, 2025).

23. Martinelli A, Killaspy H, Zarbo C, Agosta S, Casiraghi L, Zamparini M, et al. Quality of residential facilities in Italy: satisfaction and quality of life of residents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:717. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04344-w

24. Killaspy H, Priebe S, McPherson P, Zenasni Z, McCrone P, Dowling S, et al. Feasibility randomised trial comparing two forms of mental health supported accommodation (Supported Housing and Floating Outreach); a component of the QUEST (Quality and Effectiveness of Supported Tenancies) study. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:258. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00258

25. Aguiar R, Lindström M. Stories of taking part in Everyday Life Rehabilitation - A narrative inquiry of residents with serious mental illness and their recovery pathway. AIMS Public Health. (2024) 11:1198–222. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2024062

26. Greenwood RM, Stefancic A, Tsemberis S, Busch-Geertsema V. Implementations of housing first in europe: successes and challenges in maintaining model fidelity. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2013) 16:290–312. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2013.847764

27. Giummarra MJ, Randjelovic I, O’Brien L. Interventions for social and community participation for adults with intellectual disability, psychosocial disability or on the autism spectrum: An umbrella systematic review. Front Rehabil Sci. (2022) 3:935473. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2022.935473

28. Corrigan PW. Impact of consumer-operated services on empowerment and recovery of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. (2006) 57:1493–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1493

29. eurostat. Disability statistics - leisure and social participation. Statistics Explained (2024). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/ (Accessed January 15, 2025).

30. Grammenos S. Comparability of statistical data on persons with disabilities across the EU. (2024) Luxembourg: Parliament's Committee on Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL). doi: 10.2861/9204094|QA-01-24-079-EN-N

31. WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming mental health for all. (2022) Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Use World Health Organization.

32. Jacob S, Munro I, Sci BA, Chn N, Ma N, Taylor BJ, et al. Mental health recovery : A review of the peer-reviewed published literature. Collegian. (2017) 24:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2015.08.001

33. Shalaby RAH, Agyapong VIO. Peer support in mental health: Literature review. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7. doi: 10.2196/15572

34. Afita L, Nuranasmita T. The role of social support in promoting resilience and mental well-being. Bull Sci Educ. (2023) 3:269–79.

35. Jeon YH, Brodaty H, Chesterson J. Respite care for caregivers and people with severe mental illness: Literature review. J Advanced Nurs. (2005) 49:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03287.x

36. Fenwick-Smith A, Dahlberg EE, Thompson SC. Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychol. (2018) 6. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0242-3

37. Kokkinaki T, Hatzidaki E. COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions: factors that may affect perinatal maternal mental health and implications for infant development. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:846627. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.846627

38. McDaid D, Hewlett E, Park A. Understanding effective approaches to promoting mental health and preventing mental illness. OECD Health Working Papers, No. 97, Paris: OECD Publishing (2017). doi: 10.1787/bc364fb2-en

39. United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. (2022) New York, United States: United Nations Publications.

40. WHO. Mental Health ATLAS 2020. (2021) Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Use World Health Organization.

41. Becker D, Drake R. Individual placement and support: A community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Ment Health J. (1994) 30:193–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02188630

42. Wolfson P, Holloway F, Killaspy H. Enabling recovery for people with complex mental health needs. A template for rehabilitation services. In: Faculty of Rehabilitation and Social Psychiatry Working Group Report. Royal College of Psychiatrists (2009). Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/college/faculties/rehabilitationandsocialpsyc/resourcecentre.aspx. (retrieved 11 October 2010): Vol. FR/RS/1. London, United Kingdom: Royal College of Psychiatrists, Faculty of Rehabilitation and Social Psychiatry. Enabling recovery for people with complex mental h.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2018).

43. MHF. Mental Health Europe. Equal rights. Better mental health. For all. (2025). Available at: https://www.mentalhealtheurope.org/mhe-manifesto-for-better-mental-health-in-europe/ (Accessed January 15, 2025).

44. European Parliament. Mental health in the EU. (2023). EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service, online briefing.

45. Burchardt T. Being and becoming: Social exclusion and the onset of disability. LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASEREPORT21 (2003). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1163131

46. Marwaha S, Johnson S, Bebbington P, Stafford M, Angermeyer MC, Brugha T, et al. Rates and correlates of employment in people with schizophrenia in the UK, France and Germany. Br J Psychiatry. (2007) 191:30–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020982

47. Viering S, Bärtsch B, Obermann C, Rusch N, Rössler W, Kawohl W. The efectiveness of individual placement and support for people with mental illness new on social benefits:A study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. (2013) 13:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-195

48. Atanasova A. Narrowing the employment gap for people with disabilities: The need for effective policy implementation. January 2023SSRN Electronic Journal. (2023). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4652537

49. Martinelli A, Dal Corso E, Psy C, Pozzan T, Cristofalo D, Bonetto C, et al. Addressing challenges in residential facilities: promoting human rights and recovery while pursuing functional autonomy. Psych Res Clin Pract. (2024) 6(1):12–22. doi: 10.1176/appi

50. Burns T, Catty J, EQOLISE group. IPS in europe: the EQOLISE trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2008) 31:313–7. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.313.317

51. Martinelli A, Bonetto C, Bonora F, Cristofalo D, Killaspy H, Ruggeri M. Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: a pilot study of an Italian social enterprise with a special ingredient. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03881-8

52. McKay C, Nugent K, Johnsen M, Eaton W, Lidz C. A systematic review of evidence for the clubhouse model of psychosocial rehabilitation. Administration Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. (2016) 45:28–47. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0760-3

53. OECD/European Union. Promoting mental health in Europe: Why and how? In: Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris, France: OECD Publishing (2018). doi: 10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-4-en

54. WHO. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2030. (2021). Geneva Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Use World Health Organization.

55. WHO - Regional Office for Europe. 71st session of the Regional Committee for Europe (Virtual session, 13–15 September 2021). (2021).

56. WHO. Fact sheet on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): health targets. (2018) (Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe).

57. Giusti L, Ussorio D, Salza A, Casacchia M, Roncone R. Easier said than done: the challenge to teach “Personal recovery“ to mental health professionals through a short, targeted and structured training programme. Community Ment Health J. (2021) 58:1014–23. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00910-w

58. Martinelli A. Addressing challenges in functional and clinical recovery outcomes: The critical role of personal recovery. Psychiatry Res. (2024) 339. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2024.116029

59. Shepherd G, Boardman J, Burns M. Implementing Recovery: A Methodology for Organisational Change. Policy Paper. London, The UK: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010).

60. Trieman N, Leff J. Long-term outcome of long-stay psychiatric in-patients considered unsuitable to live in the community: TAPS Project 44. Br J Psychiatry. (2002) 181:428–32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.5.428

61. Fiorillo A, Barlati S, Bellomo A, Corrivetti G, Nicolò G, Sampogna G, et al. The role of shared decision-making in improving adherence to pharmacological treatments in patients with schizophrenia: a clinical review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 19. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00293-4

62. Martinelli A, Bonetto C, Pozzan T, Procura E, Cristofalo D, Ruggeri M, et al. Exploring gender impact on collaborative care planning: insights from a community mental health service study in Italy. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05307-5

63. Shields-Zeeman L, Petrea I, Smit F, Walters BH, Dedovic J, Kuzman MR, et al. Towards community-based and recovery-oriented care for severe mental disorders in Southern and Eastern Europe: Aims and design of a multi-country implementation and evaluation study (RECOVER-E). Int J Ment Health Syst. (2020) 14. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00361-y

64. Corrigan PW. Recovery from schizophrenia and the role of evidencebased psychosocial interventions. Expert Rev Neurother. (2006) 6:993–1004. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.7.993

65. Votruba N, Thornicroft G, FundaMentalSDG Steering Group. Sustainable development goals and mental health: learnings from the contribution of the FundaMentalSDG global initiative. Glob Ment Health (Camb). (2016) 3:e26. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2016.20

66. Pybus K, Pickett KE, Lloyd C, Wilkinson R. The socioeconomic context of stigma: examining the relationship between economic conditions and attitudes towards people with mental illness across European countries. Front Epidemiol. (2023) 3:1076188. doi: 10.3389/fepid.2023.1076188

Keywords: psychosocial disability, housing, employment, recovery, social inclusion, stigma, Europe

Citation: Martinelli A (2025) The key pillars of psychosocial disability: a European perspective on challenges and solutions. Front. Psychiatry 16:1574301. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1574301

Received: 10 February 2025; Accepted: 07 March 2025;

Published: 07 April 2025.

Edited by:

Ottar Ness, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NorwayReviewed by:

Shazia Tahira, Bahria University, Karachi, PakistanKamilia Hamidah, Institut Pesantren Mathali’ul Falah, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Martinelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandra Martinelli, YW1hcnRpbmVsbGlAZmF0ZWJlbmVmcmF0ZWxsaS5ldQ==

†ORCID: Alessandra Martinelli, orcid.org/0000-0002-4430-0713

Alessandra Martinelli

Alessandra Martinelli