- 1Forensic Psychiatry Division, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Psychiatry Department, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Forensic Psychiatric Clinic, Psychiatric University Hospitals, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Introduction: The measurement of patient satisfaction with mental health services is well-established and a key indicator of performance. Patient satisfaction with mental health services received in criminal justice settings however is however less frequently studied. Our aim was to establish how frequently patient satisfaction with mental health services in correctional (prison) settings is being reported, and to identify methods of measurement including all tools that have been used to measure patient satisfaction in these settings.

Methods: A comprehensive search of published articles and thesis dissertations was undertaken using multiple databases. Two reviewers independently screened the references to determine eligibility and then extracted the necessary data using a predefined extraction template. Only studies that measured patient satisfaction with a mental health service or intervention within a correctional facility were included.

Results: 46 studies, which included various measures, were identified as being eligible for inclusion. The median number of patients involved in these studies was 37.5 (range: 4–1150). Tools were heterogeneous in length, purpose, and design, and these measured a variety of different domains. Most of the tools used had been developed in non-correctional settings and applied in correctional settings without adaptation. Tools with established psychometric properties were used only in ten instances, whereas the majority of the studies reported using author-developed interviews and questionnaires to obtain feedback.

Conclusion: Patient satisfaction measurement tools in correctional services are heterogeneous and largely unvalidated; there is no uniformity in the measurement methods used.

Systematic Review Registration: https://osf.io/md8vp, identifier md8vp.

Introduction

The systematic measurement of patients’ attitudes towards their treatment in general psychiatric settings began to emerge in the 1960s, initially focusing on perceptions of the ward environment and staff interactions (1). By the 1980s, structured questionnaires became more common to evaluate satisfaction with healthcare treatment (2, 3), gaining more prominence in the 1990s (4, 5).

Patient feedback is now recognized as a key indicator of health service quality. McLellan et al. (6, 7) emphasized the importance of proactively seeking patient feedback in mental health and addiction services as part of a continuous quality improvement process (8). Direct patient feedback can be used to improve quality of care by highlighting areas of weakness in the care process, identifying unmet needs, improving patient-centered care, and driving continuous improvement. High satisfaction levels are increasingly pursued by health services as indicators of good service structure and delivery (9).

Satisfaction is a multidimensional concept, often poorly defined, but broadly reflects the patients’ subjective evaluation of the care they received (10). It is influenced by various factors directly related to the healthcare provided (11), as well as patients’ expectations of the service and variations in attitudes and response tendencies across different patient groups (12). The assessment of patients’ satisfaction with the service may be expressed in relation to the overall care received or may relate to a specific aspect of a service or treatment intervention. A significant body of literature focuses on patients’ experience of therapeutic relationships, ward atmosphere, and the social climate of mental health services (13). Environmental factors such as aesthetics, space, and food have also been the focus of satisfaction surveys. Nevertheless, there are established methods for obtaining reliable measurement despite the diversity of the concept (14).

Correctional services have grown internationally and are now said to be the largest providers of mental health services in the United States (15). The number of people in prisons globally has reached 11.5 million (16), with approximately one in seven incarcerated individuals having psychosis or major depression (17). International standards such as the Mandela Rules (18), Bangkok Rules (19), and the American Psychiatric Association’s practice guidelines (20) require that people who are incarcerated should receive health care that is at least equivalent to those who are not incarcerated", however the quality of healthcare often falls below acceptable standards (21). The development of clinical service tools for evaluating quality of correctional mental health services has lagged behind other healthcare services. Systematic measurement of patient satisfaction is essential to capture the experiences and perspectives of this population and to incorporate them into service improvement efforts.

Although correctional facilities present unique challenges for mental health service provision, patient feedback should be integral as one facet of measuring the adequacy of the service. Those who receive care in coercive environments have limited autonomy and may fear negative consequences from expressing dissatisfaction. Despite this, assessment of patient satisfaction has been established in forensic mental health services where involuntary detention is also present, and patients have been shown to provide thoughtful feedback on the healthcare service (22). Nevertheless, there are clear differences in healthcare delivery in correctional facilities compared to hospitals and other healthcare settings, such as an enhanced focus on security, crisis intervention, and more limited resources in custodial settings, which require adaptations in the methods used to assess satisfaction.

We therefore carried out a scoping review to summarize the international literature on the practice of patient satisfaction measurement with mental health services in correctional settings. Our aim was to establish (1) how frequently patient satisfaction with mental health services is reported; (2) identify the methods used to assess patient satisfaction, and (3) identify all published tools used to measure patient satisfaction in these settings, including their psychometric properties, and any evidence of replication or validation.

Methods

We used the PCC (Population, Concept and Context) framework to guide the development of the review question (23). The PCC elements were as follows: (a) Population: individuals in a criminal justice mental health service referred to as “patients” or “clients”, who have received or are receiving mental health care during incarceration (we consider “patient” and “client” to be synonymous for the purpose of this review). (b) Concept: patient satisfaction with the mental health service or intervention that they have received. We have considered “satisfaction”, “patient perception of care” and “patient experience” as interchangeable for the purpose of this review. We have included studies that measured patient satisfaction with mental health services overall, or any specific therapeutic group or intervention received. (c) Context: the term ‘criminal justice setting’ is used here to refer to any facility where incarcerated individuals are detained while awaiting trial or after being sentenced. These institutions are known in different jurisdictions as jails, prisons, penitentiaries, or correctional centers.

A correctional mental health service is defined as any service addressing the psychiatric needs of incarcerated individuals within a correctional facility. These services are typically designed to treat incarcerated individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental disorder prior to their incarceration, during their incarceration, or when facing an acute mental health crisis.

The review protocol was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) methodology (24) and was registered on the Open Science Framework Registries (25).

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

We aimed to identify all studies that measured patient satisfaction with mental health services in a correctional setting that were published in English involving adult patients (aged 18 and above). All study designs were considered. We excluded studies if they primarily measured aspects that were not directly part of the healthcare service (e.g. perceptions of safety and security), those evaluating satisfaction with services for addictions, and those eliciting only staff attitudes or perceptions of care.

Search strategy

We considered all literature published in any year in English until the final search date on 1 August 2024. A search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian. Studies were identified through a search of PsycINFO, PubMed and CINAHL databases, as well as hand-searches conducted in Google Scholar and reference scans of identified papers. The following list of search terms was used: “offender”, “inmate”, “prison”, “incarcerated”, “detainee”, “jail”, “feedback”, “prisoners”, “correctional institutions”, “correction or detention center or center or facility or institute”, “satisfaction or preference or opinion, tool or survey or questionnaire”.

Screening and data extraction were carried out by two independent reviewers. Any conflicts were resolved after discussion with the principal investigator. We carried out a narrative synthesis to examine and summarize the findings of the included studies. Search terms, method of analysis (descriptive), inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in advance and documented in the protocol. The literature reviewed included primary research studies published in a peer-reviewed journal and thesis dissertations. Articles were limited to English language, and no date limitation was set.

Data sources and data extraction

After the database searches were completed, the records were imported into Covidence—a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews (26)—and duplicates were automatically removed. All abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers, and a third one for conflict resolution where this arose. Abstracts that met the aforementioned eligibility criteria were subjected to a full-text screening by the same reviewers, and eligible studies were retained.

Study selection and characteristics

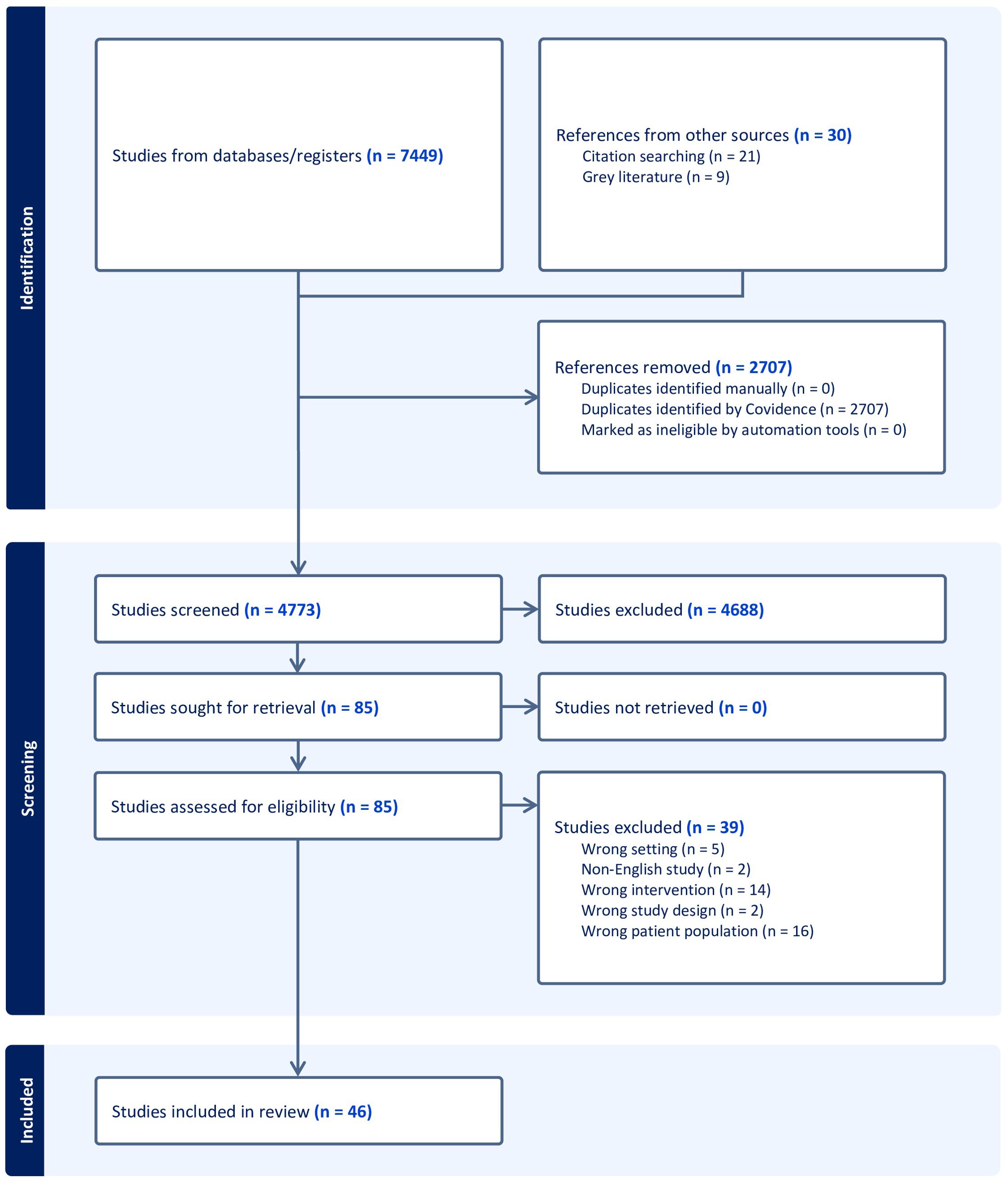

A total of 7479 papers were identified using the search strategy. After removing duplicates, posters, and non-original studies, 4772 papers remained. Following a review of abstracts, 85 papers were subjected to a full text review and 46 studies were eligible for inclusion (See Figure 1).

Results

Synthesized findings

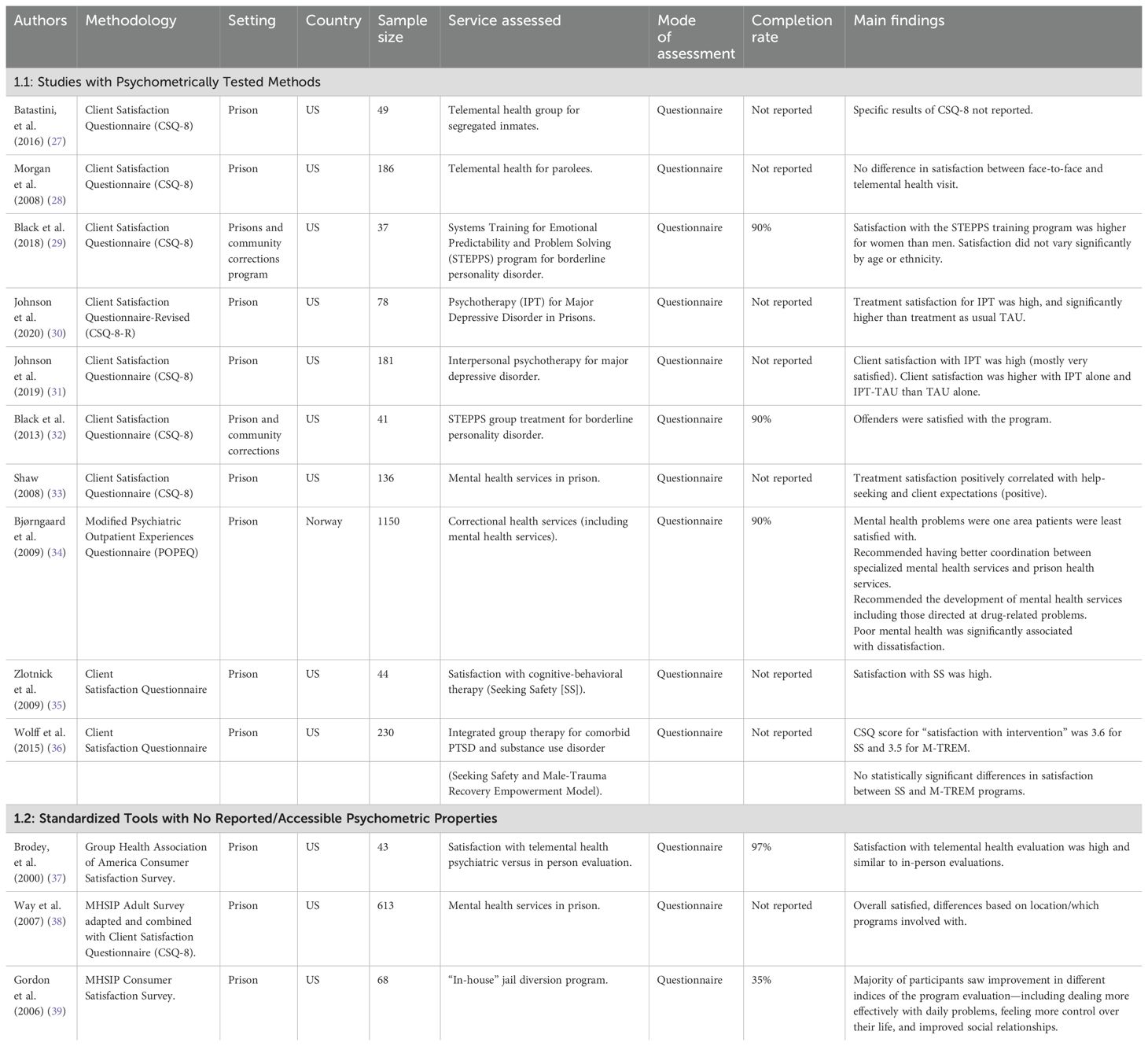

Studies fell into three major categories: studies with tools that showed evidence of psychometric testing (10 studies), studies that reported standardized tools but without psychometric testing in the setting used (3 studies), and study-specific questionnaires or semi-structured interviews (34 studies) (Tables 1–3).

Psychometrically validated tools

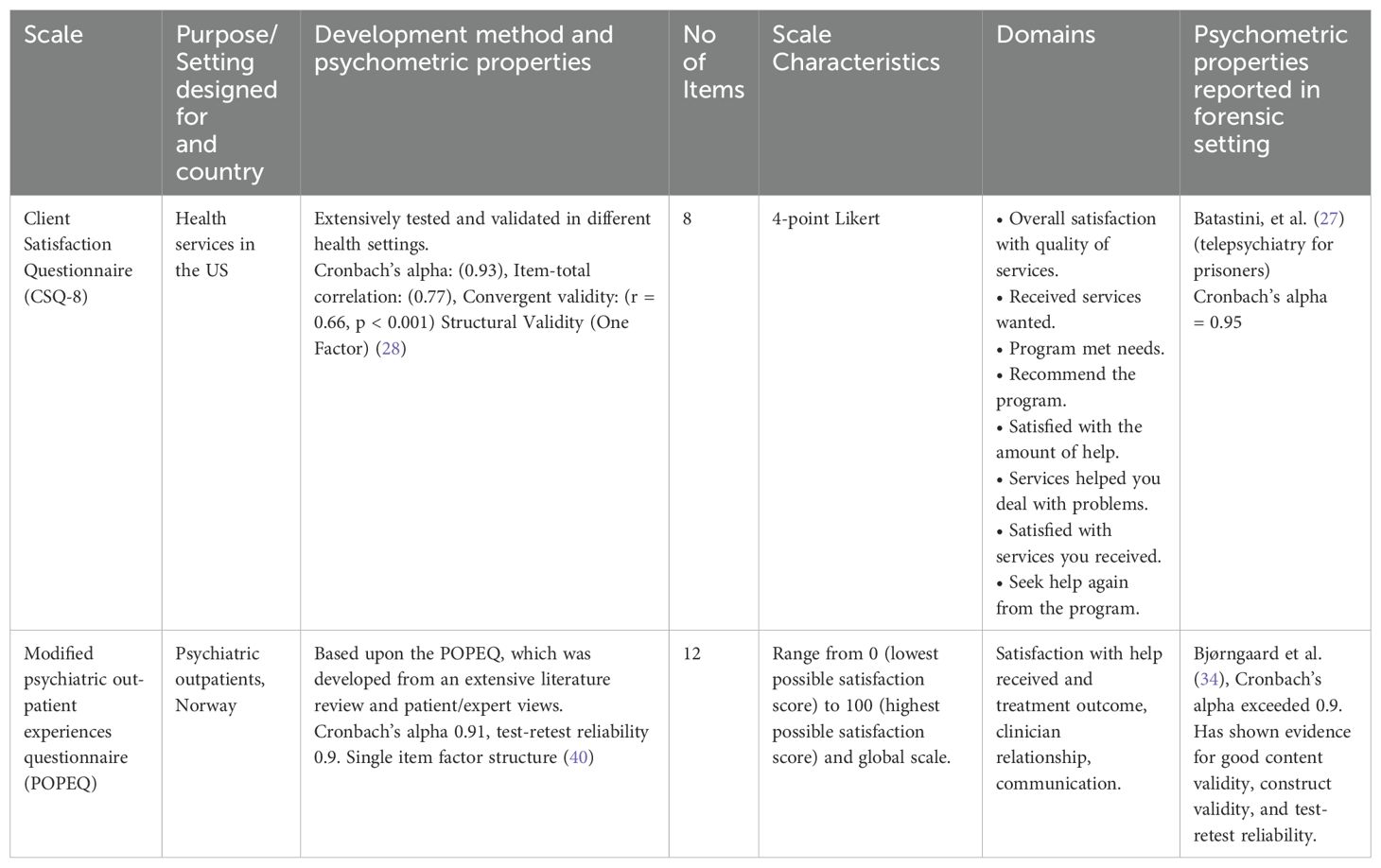

We identified 10 studies, nine of which were conducted in the United States (US), and one in Norway. (Table 1.1). All of the US studies used the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) and the Norwegian study used a modified Psychiatric Out-patient Experiences Questionnaire (POPEQ). Both tools were originally developed in civil settings but had psychometric properties reported in correctional settings (Table 2). The CSQ-8 is an 8-item unidimensional tool that addresses satisfaction with service desirability, perceived helpfulness, intention to reuse the program, program recommendation and overall satisfaction (3). Although the CSQ-8 has been widely used in various healthcare settings, only two studies in correctional settings reported psychometric properties specific to their analysis (27, 33). Bjørngaard et al. (2009) modified an existing tool, the Psychiatric Out-Patient Experiences Questionnaire (POPEQ) (40). This is a 12-item questionnaire, and has a unidimensional structure. As it had been developed for outpatients, it was modified to be applicable to a correctional setting.

Eight of the ten studies were conducted exclusively within a correctional setting, and two studies additionally involved community corrections programs. Only two studies evaluated correctional mental health services overall, two studies assessed telepsychiatric services, and the remaining six evaluated specific mental health programs, such as a program designed for borderline personality disorder (STEPPS) and psychotherapy. The sample sizes varied, from 37 to 1150. Three studies reported response rates (all 90%). None of the studies reported regular use over time to track trends in satisfaction measures, nor was there any evidence that responses were used to initiate service changes.

Non-psychometrically tested tools

Three studies used standardized tools without reported or accessible psychometric properties (Table 1.2). These tools included the Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program (MHSIP) Consumer Satisfaction Survey (39), MHSIP adapted with a CSQ-8 (38), and Group Health Association of America Consumer Satisfaction Survey (GHACSS) (37). The MHSIP measured domains including accessibility, perceived benefit, overall satisfaction, as well as satisfaction with treatment processes and content; its modified version additionally incorporated measures of medication compliance, misbehavior, and utilization of crisis services (38, 39). The GHACSS evaluated patients’ perceptions of the evaluator and overall satisfaction with the evaluation (37). All three studies were conducted in the US and exclusively within correctional settings. Two studies (37, 39) reported completion rates of 35% (Gordon et al, 2006) and 97% (Brodey et al, 2000).

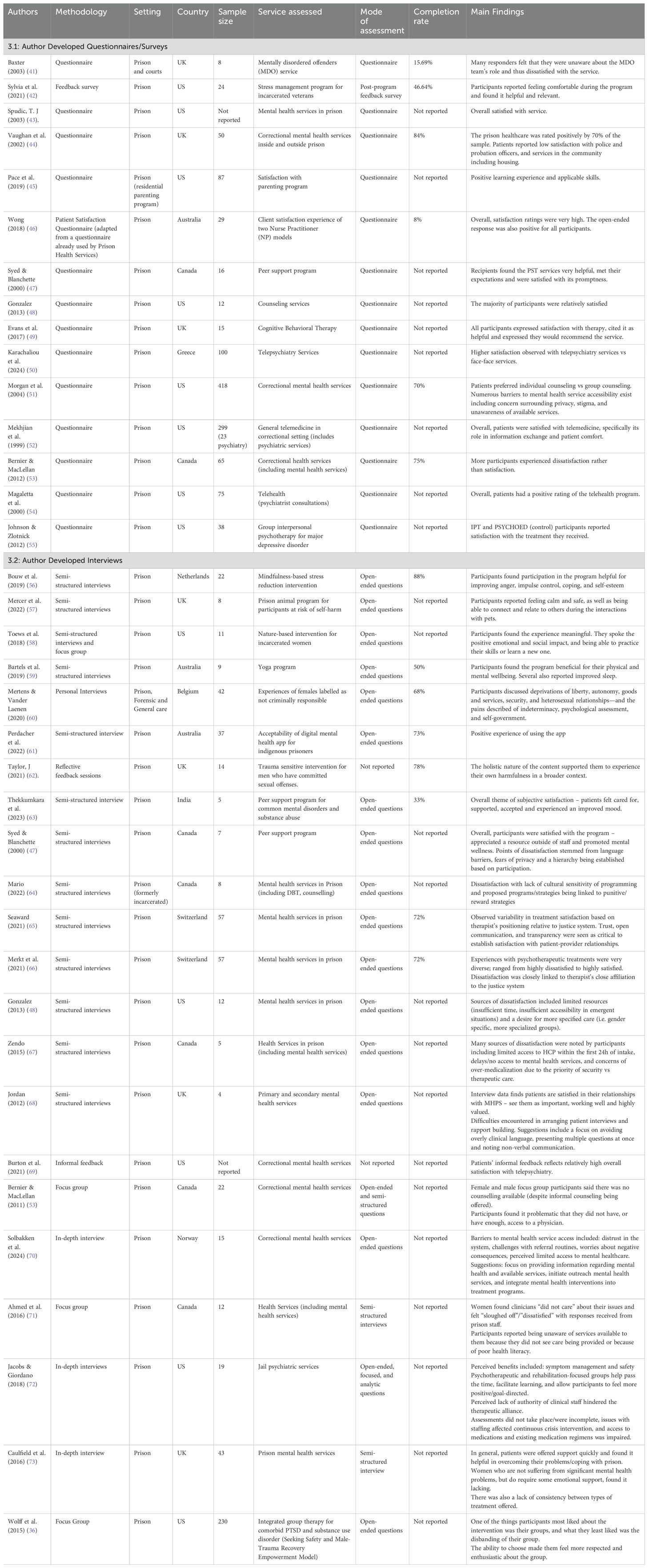

There were 15 studies which had developed questionnaires specifically for the site that they were evaluating and had not been replicated in other settings (Table 3.1). Of these studies, eight were conducted in the USA, three in the UK, two in Canada, one in Australia, and one in Greece. Five studies evaluated satisfaction with correctional mental health services overall; three of these focused on telepsychiatric services. Nine focused on specific programs including counseling services, cognitive behavioral therapy, peer support programs, a stress reduction program, and a parenting program. A single study evaluated patient satisfaction with two different nurse practitioner models. The sample sizes varied, ranging from 8 to 418. The surveys addressed domains such as helpfulness, expectations, perceived effectiveness, recommendation, promptness, and overall service satisfaction.

Twenty-three studies (Table 3.2) employed study-specific interviews aimed at capturing satisfaction or providing feedback regarding the adequacy of mental health services. Numerous studies rationalized that an open-ended format would provide the necessary opportunity for elaboration, considering the subjectivity of satisfaction as a measure. Of these studies, six were from the USA, five from Canada, four from the UK, two from Australia, two from Switzerland, and one each from Belgium, Norway, the Netherlands, and India.

The completion rate was reported in 9 studies, with an average of 68.67% (range: 33-88%; SD: 17.17). Thirteen studies evaluated general satisfaction with mental health services, while the remaining 10 focused on specific programs, including digital mental health services, mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention, nature-based intervention, prison animal program, yoga program, peer support programs, and trauma sensitive interventions. Five studies concentrated on specific subsets of the correctional population; three exclusively interviewed female detainees, one interviewed Indigenous inmates, and one evaluated a service specific to sexual offenders. The interview structure covered domains such as relationships with providers, accessibility, implications on day-to-day life, and overall satisfaction with the program. While the vast majority of studies employing satisfaction questionnaires reported positive feedback towards the services evaluated, seven of the interview-based studies reported sources of dissatisfaction. These included concerns surrounding privacy, accessibility of services, over-medicalization, and a desire for more specialized and patient-centered care (i.e. cultural sensitivity, addressing language barriers).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify the tools and methods used to measure patient satisfaction with correctional mental health services or specific interventions. Four main findings emerge from our review.

First, very few studies have measured patient satisfaction in correctional settings overall. There were 46 studies identified in the entire literature in English, and most were very small indicating this is a much overlooked area of inquiry given the size of the population receiving mental health services in correctional settings.

Second, only two different psychometrically validated tools have been reported (CSQ-8 and POPEQ) and neither had been designed specifically for use in correctional settings.

Third, the majority of studies had used study-specific (ad-hoc) surveys or interviews to evaluate satisfaction for a particular group or intervention which had not been validated. None of the study-specific measures demonstrated psychometric properties required for widespread dissemination.

Fourth, while patient satisfaction is a multidimensional concept, the only tools validated in correctional settings to date have unidimensional structures (3, 40). This suggests that important dimensions of patient satisfaction relevant to correctional settings may not be adequately captured by existing tools.

Psychometric methodology is essential to establish the reliability and validity of instruments when evaluating complex constructs such as patient satisfaction. However, only one instrument, the CSQ-8, met the established standards for psychometric development (74), and it has been validated outside the correctional environment. This raises questions about its applicability within correctional environments. There have been numerous studies that have developed questionnaires for measuring satisfaction in forensic settings; however, these are specific to inpatient populations and may not translate effectively to correctional settings (75–80). This highlights the need to develop and validate satisfaction instruments designed for use with correctional populations.

In addition, it is important to engage service users and content experts in developing the components of satisfaction to make sure that the domains assessed reflect the priorities and perspectives of those being assessed (81). Failure to incorporate patient perspectives has been a major criticism of past satisfaction questionnaires (81–84). None of the study-specific questionnaires described how items were generated, nor whether input from patients or other stakeholders informed their development. Furthermore, recurrent themes of interest identified in studies applying a qualitative methodology, such as privacy, staff-patient relationships, and effective communication, were frequently absent from the survey questionnaires (47, 48, 64–66).

Few studies described the regular use of satisfaction surveys or how satisfaction data have been translated into actionable changes for mental health service delivery and quality improvement. Reporting such experiences could reinforce the utility of satisfaction tools and provide valuable insights into the ongoing development of correctional mental health care provision. Communication of this purpose could help promote a more patient-centered approach addressing concerns that have been highlighted in numerous studies (48, 64).

Beyond considerations of tool development, the methods used to administer the tools should also be considered. For correctional populations, ensuring anonymity during data collection and dissemination is essential, considering patients’ fears of stigma and criticism from disclosure (47). Many of the studies had small sample sizes and low completion rates which may indicate concerns about lack of confidentiality. Therefore, ensuring that there are robust mechanisms in place to preserve anonymity, coupled with efforts to reduce the stigma of mental health care among both patients and correctional staff could improve participation and data quality.

The majority of studies included in our review evaluated satisfaction using surveys, a favored approach due to their ease of administration. However, dissatisfaction with correctional mental health services was more readily apparent in studies which adopted a qualitative methodology. This may be attributed to the open format of an interview, which enables participants to contextualize their experiences and to express views that may not emerge from structured surveys (85).

There are several limitations to our review. We excluded non-English studies and studies which evaluated correctional mental health services from the perspectives of other stakeholders (i.e., clinicians, family members). This could be an avenue for further research. In addition, correctional settings prove a challenging environment for conducting research; although many correctional services may carry out satisfaction surveys for continuous quality improvement, unfavorable results could discourage these services from widely disseminating their data, contributing to publication bias.

Conclusion

There is currently no standardized or widely accepted method for measuring patient satisfaction measurement with the mental health services in correctional settings. While adapting tools developed in non-correctional settings is a reasonable step, validation is required for use in correctional settings. Moreover, none of the reviewed studies described repeated use, stakeholder co-design or the results of regular satisfaction surveys to monitor service quality over time. The results of this review emphasize the need for correctional-specific tool development and validation in correctional settings, to regularly gauge patient satisfaction and implement measures to improve service delivery when deficiencies are identified.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NM: Writing – original draft, Data curation. MW: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. MM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. CT: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. VA: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. MK: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. CG: Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Weinstein RM. Patient attitudes toward mental hospitalization: A review of quantitative research. J Health Soc Behavior. (1979) 20:237–58.

2. Hansson L. Patient satisfaction with in-hospital psychiatric care: A study of a 1-year population of patients hospitalized in a sectorized care organization. Eur Arch Psychiatry neurological Sci. (1989) 239:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01759581

3. Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. (1982) 5:233–7. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x

4. Greenwood N, Key A, Burns T, Bristow M, Sedgewick P. Satisfaction with in-patient psychiatric services: relationship to patient and treatment factors. Br J Psychiatry. (1999) 174:159–63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.2.159

5. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB, Thiele J, Higdon J. Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr services. (1998) 49:929–34. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.7.929

6. Thomas McLellan A, Hunkeler E. Alcohol & Drug abuse: patient satisfaction and outcomes in alcohol and drug abuse treatment. Psychiatr Services. (1998) 49:573–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.5.573

7. McLellan AT, Chalk M, Bartlett J. Outcomes, performance, and quality: what’s the difference? J Subst Abuse Treat. (2007) 32:331–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.09.004

8. Meadows G, Burgess P, Fossey E, Harvey C. Perceived need for mental health care, findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychol Med. (2000) 30:645–56. doi: 10.1017/S003329179900207X

9. Miglietta E, Belessiotis-Richards C, Ruggeri M, Priebe S. Scales for assessing patient satisfaction with mental health care: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 100:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.014

10. Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: A review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Medicine. (1997) 45:1829–43. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00128-7

11. McInnes DK. Don’t forget patients in patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood). (2010) 29:2127. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0990

12. Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. (2014) 7:235–41. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0060-5

13. Schalast N, Redies M, Collins M, Stacey J, Howells K. EssenCES, a short questionnaire for assessing the social climate of forensic psychiatric wards. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2008) 18:49–58. doi: 10.1002/cbm.v18:1

14. Lyratzopoulos G, Elliott MN, Barbiere JM, Staetsky L, Paddison CA, Campbell J, et al. How can Health Care Organizations be Reliably Compared?: Lessons From a National Survey of Patient Experience. Med Care. (2011) 49:724–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b3482

15. Reingle Gonzalez JM, Connell NM. Mental health of prisoners: identifying barriers to mental health treatment and medication continuity. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:2328–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302043

16. Nations U, UNODC. Prison Matters 2024: Global prison population and trends. A focus on rehabilitation (2024) UNODC. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/briefs/Prison_brief_2024.pdf.

17. Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, Clerici M, Trestman R. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:871–81. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0

18. McCall-Smith K. United Nations standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules). International Legal Materials. (2016) 55(6):1180–205. doi: 10.1017/S002078290003089

19. Priebe S, Miglietta E. Assessment and determinants of patient satisfaction with mental health care. World Psychiatry. (2019) 18:30–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20586

20. Association AP. Psychiatric services in correctional facilities. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Pub (2015). Available at: https://www.appi.org/psychiatric_services_in_correctional_facilities_third_edition.

21. Preston AG, Rosenberg A, Schlesinger P, Blankenship KM. I was reaching out for help and they did not help me”: Mental healthcare in the carceral state. Health Justice. (2022) 10:23. doi: 10.1186/s40352-022-00183-9

22. Coffey M. Researching service user views in forensic mental health: A literature review. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. (2006) 17:73–107. doi: 10.1080/14789940500431544

23. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13(3):141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

24. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-scR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

25. Jones R, Waqar M, Simpson S. Client satisfaction measures in correctional settings: A scoping review protocol. (2024). doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/MD8VP

26. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. (2024). Available online at: www.covidence.org (Accessed October 9, 2024).

27. Batastini AB, Morgan RD. Connecting the disconnected: Preliminary results and lessons learned from a telepsychology initiative with special management inmates. Psychol Serv. (2016) 13:283–91. doi: 10.1037/ser0000078

28. Morgan RD, Patrick AR, Magaletta PR. Does the use of telemental health alter the treatment experience? Inmates’ perceptions of telemental health versus face-to-face treatment modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2008) 76:158–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.158

29. Black DW, Blum N, Allen J. Does response to the STEPPS program differ by sex, age, or race in offenders with borderline personality disorder? Compr Psychiatry. (2018) 87:134–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.005

30. Johnson JE, Hailemariam M, Zlotnick C, Richie F, Sinclair J, Chuong A, et al. Mixed methods analysis of implementation of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for major depressive disorder in prisons in a hybrid type I randomized trial. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2020) 47:410–26. doi: 10.1007/s10488-019-00996-1

31. Johnson JE, Stout RL, Miller TR, Zlotnick C, Cerbo LA, Andrade JT, et al. Randomized cost-effectiveness trial of group interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for prisoners with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2019) 87:392–406. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000379

32. Black DW, Blum N, McCormick B, Allen J. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) group treatment for offenders with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2013) 201:124–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827f6435

33. Shaw LB. Inmate characteristics and mental health services: An examination of service utilization and treatment effects. Texas Tech University (2008). Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/2346/10548.

34. Bjorngaard JH, Rustad AB, Kjelsberg E. The prisoner as patient - a health services satisfaction survey. BMC Health Serv Res. (2009) 9:176. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-176

35. Zlotnick C, Johnson J, Najavits LM. Randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy in a sample of incarcerated women with substance use disorder and PTSD. Behav Ther. (2009) 40:325–36. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.09.004

36. Wolff N, Huening J, Shi J, Frueh BC, Hoover DR, McHugo G. Implementation and effectiveness of integrated trauma and addiction treatment for incarcerated men. J Anxiety Disord. (2015) 30:66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.10.009

37. Brodey BB, Claypoole KH, Motto J, Arias RG, Goss R. Satisfaction of forensic psychiatric patients with remote telepsychiatric evaluation. Psychiatr Serv. (2000) 51:1305–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.10.1305

38. Way BB, Sawyer DA, Kahkejian D, Moffitt C, Lilly SN. State prison mental heath services recipients perception of care survey. Psychiatr Q. (2007) 78:269–77. doi: 10.1007/s11126-007-9048-9

39. Gordon JA, Barnes CM, VanBenschoten SW. The dual treatment track program: A descriptive assessment of a new in-house jail diversion program. Fed Probation. (2006) 70:9. Available online at: https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/70_3_2_0.pdf.

40. Garratt A, Bjørngaard JH, Dahle KA, Bjertnaes OA, Saunes IS, Ruud T. The Psychiatric Out-Patient Experiences Questionnaire (POPEQ): data quality, reliability and validity in patients attending 90 Norwegian clinics. Nord J Psychiatry. (2006) 60:89–96. doi: 10.1080/08039480600583464

41. Baxter V. Evaluating a service for offenders with mental health problems. Nurs times. (2003) 99:24–7.

42. Sylvia LG, Chudnofsky R, Fredriksson S, Xu B, McCarthy MD, Francona J, et al. A pilot study of a stress management program for incarcerated veterans. Mil Med. (2021) 186:1061–5. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab121

43. Spudic T. Assessing inmate satisfaction with mental health services. New York City: Behaviour Therapy in Correctional Settings (2003) p. 217–8.

44. Vaughan P, Stevenson S. An opinion survey of mentally disordered offender service users. Br J Forensic Practice. (2002) 4:11–20. doi: 10.1108/14636646200200017

45. Pace AE, Krings K, Dunlap J, Nehilla L. Service and learning at a residential parenting program for incarcerated mothers: Speech-language pathology student outcomes and maternal perspectives. Language speech hearing Serv schools. (2019) 50:308–23. doi: 10.1044/2018_LSHSS-CCJS-18-0030

46. Wong I, Wright E, Santomauro D, How R, Leary C, Harris M. Implementing two nurse practitioner models of service at an Australian male prison: A quality assurance study. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27:e287–300. doi: 10.1111/jocn.2018.27.issue-1pt2

47. Syed F, Blanchette K. Results of an evaluation of the peer support program at Grand Valley Institution for Women. Correctional Service Canada, Research Branch, Corporate Development (2000). Available online at: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/scc-csc/PS83-3-86-eng.pdf.

48. Gonzalez M. Voices from Behind Bars: A Working Alliance? University of Missouri, St. Louis (2013).

49. Evans C, Forrester A, Jarrett M, Huddy V, Campbell CA, Byrne M, et al. Early detection and early intervention in prison: improving outcomes and reducing prison returns. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. (2017) 28:91–107. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2016.1261174

50. Karachaliou E, Douzenis P, Chatzinikolaou F, Pantazis N, Martinaki S, Bali P, et al. Prisoners’ Perceptions and satisfaction with telepsychiatry services in Greece and the effects of its use on the coercion of mental healthcare. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12(10):1044. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12101044

51. Morgan RD, Rozycki AT, Wilson S. Inmate perceptions of mental health services. Prof psychology: Res practice. (2004) 35:389. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.4.389

52. Mekhjian H, Turner JW, Gailiun M, McCain TA. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine in a prison environment. J Telemed Telecare. (1999) 5:55–61. doi: 10.1258/1357633991932397

53. Bernier JR, MacLellan K. Health status and health services use of female and male prisoners in provincial jail. Halifax, Canada: Atlantic Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (2012).

54. Magaletta PR, Fagan TJ, Peyrot MF. Telehealth in the federal bureau of prisons: Inmates’ perceptions. Prof Psychology: Res Practice. (2000) 31:497. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.31.5.497

55. Johnson JE, Zlotnick C. Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2012) 46:1174–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.007

56. Bouw N, Huijbregts SCJ, Scholte E, Swaab H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in prison: experiences of inmates, instructors, and prison staff. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2019) 63:2550–71. doi: 10.1177/0306624X19856232

57. Mercer J, Davies EW, Cook M, Bowes NJ. I feel happier in myself with the dogs”: the perceived impact of a prison animal programme for well-being. J Forensic Practice. (2022) 24:81–94. doi: 10.1108/JFP-11-2021-0057

58. Toews B, Wagenfeld A, Stevens J. Impact of a nature-based intervention on incarcerated women. Int J Prison Health. (2018) 14:232–43. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-12-2017-0065

59. Bartels L, Oxman LN, Hopkins A. I would just feel really relaxed and at peace”: findings from a pilot prison yoga program in Australia. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminology. (2019) 63:2531–49. doi: 10.1177/0306624X19854869

60. Mertens A, Vander Laenen F. Pains of imprisonment beyond prison walls: qualitative research with females labelled as not criminally responsible. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2020) 64:1343–63. doi: 10.1177/0306624X19875579

61. Perdacher E, Kavanagh D, Sheffield J, Healy K, Dale P, Heffernan E. Using the stay strong app for the well-being of indigenous Australian prisoners: feasibility study. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6:e32157. doi: 10.2196/32157

62. Taylor J. Compassion in custody: developing a trauma sensitive intervention for men with developmental disabilities who have convictions for sexual offending. Adv Ment Health Intellectual Disabilities. (2021) 15:185–200. doi: 10.1108/AMHID-01-2021-0004

63. Thekkumkara S, Jagannathan A, Muliyala KP, Joseph A, Murthy P. Feasibility testing of a peer support programme for prisoners with common mental disorders and substance use. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2023) 33:229–42. doi: 10.1002/cbm.v33.4

64. Mario B. Responsibilizing Rehabilitation: A Critical Investigation of Correctional Programming for Federally Sentenced Women. Ottawa, Canada: Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa (2022).

65. Seaward H. Intersections of mental health and criminal justice: A qualitative study of women in Swiss prisons. Basel, Switzerland: University of Basel (2022).

66. Merkt H, Wangmo T, Pageau F, Liebrenz M, Devaud Cornaz C, Elger B. Court-mandated patients’ Perspectives on the psychotherapist’s dual loyalty conflict – between ally and enemy. Front Psychol. (2021) 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.592638

67. Zendo S. The Experiences of Criminalized Women When Accessing Health Care Services During Incarceration Within Provincial Jails: A Critical Narrative Study. London, Ontario, Canada: The University of Western Ontario Canada (2015).

68. Jordan M. Prison mental health: context is crucial: a sociological exploration of male prisoners’ mental health and the provision of mental healthcare in a prison setting. Nottingham, United Kingdom: University of Nottingham (2012).

69. Burton PRS, Morris NP, Hirschtritt ME. Mental health services in a U.S. Prison during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. (2021) 72:458–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000476

70. Solbakken LE, Bergvik S, Wynn R. Breaking down barriers to mental healthcare access in prison: a qualitative interview study with incarcerated males in Norway. BMC Psychiatry. (2024) 24:292. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05736-w

71. Ahmed R, Angel C, Martel R, Pyne D, Keenan L. Access to healthcare services during incarceration among female inmates. Int J Prison Health. (2016) 12:204–15. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-04-2016-0009

72. Jacobs LA, Giordano SNJ. It’s not like therapy”: patient-inmate perspectives on jail psychiatric services. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2018) 45:265–75. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0821-2

73. Caulfield LS. Counterintuitive findings from a qualitative study of mental health in English women’s prisons. Int J Prison Health. (2016) 12:216–29. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-05-2016-0013

74. Fung D, Cohen MM. Measuring patient satisfaction with anesthesia care: A review of current methodology. Anesthesia Analgesia. (1998) 87:1089–98. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199811000-00020

75. Meehan T, Bergen H, Stedman T. Monitoring consumer satisfaction with inpatient service delivery: the Inpatient Evaluation of Service Questionnaire. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2002) 36:807–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01094.x

76. Shiva A, Haden SC, Brooks J. Forensic and civil psychiatric inpatients: development of the inpatient satisfaction questionnaire. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law Online. (2009) 37:201–13.

77. Shiva A, Haden SC, Brooks J. Psychiatric civil and forensic inpatient satisfaction with care: the impact of provider and recipient characteristics. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr epidemiology. (2009) 44:979–87. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0019-3

78. Macinnes D, Beer D, Keeble P, Rees D, Reid L. The development of a tool to measure service user satisfaction with in-patient forensic services: the forensic satisfaction scale. J Ment Health. (2010) 19:272–81. doi: 10.3109/09638231003728133

79. MacInnes D, Courtney H, Flanagan T, Bressington D, Beer D. A cross sectional survey examining the association between therapeutic relationships and service user satisfaction in forensic mental health settings. BMC Res notes. (2014) 7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-657

80. Bressington D, Stewart B, Beer D, MacInnes D. Levels of service user satisfaction in secure settings–A survey of the association between perceived social climate, perceived therapeutic relationship and satisfaction with forensic services. Int J Nurs Stud. (2011) 48:1349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.011

81. Chou S-C, Boldy DP, Lee AH. Measuring resident satisfaction in residential aged care. Gerontologist. (2001) 41:623–31. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.623

82. Larrabee JH, Bolden LV. Defining patient-perceived quality of nursing care. J Nurs Care Quality. (2001) 16:34–60. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200110000-00005

83. Castle NG. A review of satisfaction instruments used in long-term care settings. J Aging Soc Policy. (2007) 19:9–41. doi: 10.1300/J031v19n02_02doi: 10.1300/J031v19n02_02

84. Robinson JP, Lucas JA, Castle NG, Lowe TJ, Crystal S. Consumer satisfaction in nursing homes: current practices and resident priorities. Res Aging. (2004) 26:454–80. doi: 10.1177/0164027504264435

Keywords: patient satisfaction, correctional psychiatry, forensic psychiatry, scoping review, mental health, incarceration

Citation: Jones RM, Mather N, Waqar MU, Manetsch M, Taylor C, Adamo V, Kilada M, Gerritsen C and Simpson AIF (2025) Measuring patient satisfaction with mental health services in correctional settings: a systematic scoping review. Front. Psychiatry 16:1575157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1575157

Received: 11 February 2025; Accepted: 15 April 2025;

Published: 14 May 2025.

Edited by:

Yasin Hasan Balcioglu, Bakirkoy Prof Mazhar Osman Training and Research Hospital for Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Panteleimon Giannakopoulos, Geneva University Hospitals, SwitzerlandStefano Ferracuti, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Gizem Sahin-Bayindir, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Jones, Mather, Waqar, Manetsch, Taylor, Adamo, Kilada, Gerritsen and Simpson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roland M. Jones, cm9sYW5kLmpvbmVzQGNhbWguY2E=

Roland M. Jones

Roland M. Jones Niroshini Mather1

Niroshini Mather1 M. Umer Waqar

M. Umer Waqar Vito Adamo

Vito Adamo Cory Gerritsen

Cory Gerritsen Alexander I. F. Simpson

Alexander I. F. Simpson