- Department of Psychiatry, 82nd Group Army Hospital of People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Baoding, Hebei, China

Background: Trichotillomania is a chronic psychiatric and behavioral disorder characterized by recurrent hair-pulling, often leading to significant distress and impairment. Long-term psychotherapeutic case reports remain scarce, especially those integrating Narrative Therapy and the Satir Model in culturally-specific and resource-limited contexts.

Case Presentation: We present a two-year integrated psychotherapy case for a 28-year-old woman with trichotillomania, utilizing Narrative Therapy and Satir Transformational Systemic Therapy. Assessments included the Massachusetts General Hospital Hair Pulling Scale (MGH-HPS), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP), and Clinical Global Impression (CGI). Hair-pulling episodes decreased from 150 per day to 5, and MGH-HPS, SAS, and PSP scores improved substantially from baseline to end of treatment and one-year follow-up. The patient maintained gains post-treatment, with improved self-worth and social functioning.

Conclusions: This case supports the clinical utility of a Narrative Therapy–Satir Model integration for trichotillomania. The flexible, person-centered approach yielded lasting symptom and functional gains. Limitations include reliance on self-report and potential bias.

Introduction

Trichotillomania, also known as hair-pulling disorder, is a chronic and often debilitating psychiatric condition characterized by recurrent, irresistible urges to pull out one’s hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss and significant distress or functional impairment (1). First described by Hallopeau in 1889 (2), trichotillomania is estimated to affect approximately 1–2% of the general population, with a higher prevalence in females. The disorder frequently begins in childhood or adolescence and is often concealed by affected individuals due to feelings of shame or embarrassment, contributing to delays in seeking treatment and increased psychosocial burden (3).

Standard treatments for trichotillomania include pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions, particularly habit reversal training and cognitive-behavioral therapy (4). However, many patients experience only partial symptom relief or may be reluctant to engage in conventional treatments, especially in culturally-specific or resource-limited settings. There is growing recognition that innovative, integrative psychotherapeutic approaches are needed to address the complex emotional, relational, and identity issues underlying chronic hair-pulling.

Narrative Therapy, which emphasizes externalizing the problem and reconstructing personal meaning through storytelling, has shown promise in empowering individuals to re-author their experiences and identities (5), The Satir Model, a systemic and experiential approach, focuses on enhancing self-worth, improving family dynamics, and fostering emotional integration (6). despite the theoretical compatibility of these approaches, empirical reports documenting their long-term, combined application for trichotillomania remain rare, particularly in East Asian and low-resource contexts.

This case report follows CARE guidelines and aims to: (1) clarify the theoretical rationale for integrating Narrative Therapy and Satir Model interventions; (2) describe outcome measures and analytic methods; (3) present a visual and narrative timeline of the treatment process; and (4) include the patient’s perspective on recovery.

Patient information

Demographics

28-year-old married woman from Baoding, China.

Presentation

Sought psychiatric care before her wedding, reporting severe, chronic hair-pulling since age 8.

Family history

No formal psychiatric diagnoses reported, but her mother exhibited hair-pulling in childhood, which resolved spontaneously in adulthood.

Social history

Grew up in a dysfunctional family (paternal illness, parental conflict), assumed significant family responsibilities from a young age.

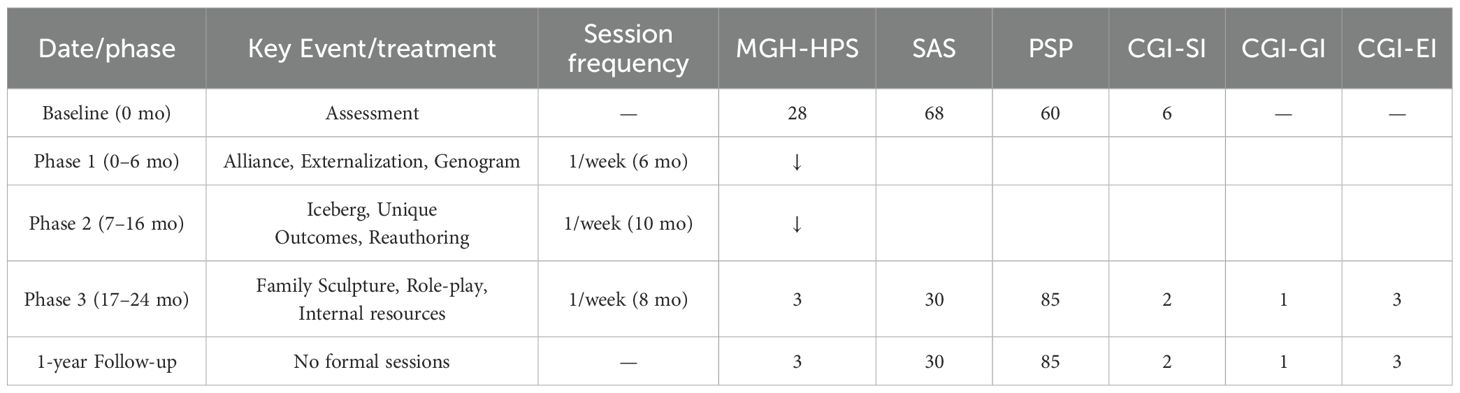

The key events, interventions, and clinical outcome measures of this patient’s treatment are summarized in Table 1.

Diagnostic assessment

● DSM-5 Criteria: Meets criteria for trichotillomania (1).

● MGH-HPS: Seven items, 0–28, higher=more severe (7).

● SAS: 20 items, 25–100, >63 = moderate to severe anxiety (8).

● PSP: 0–100, higher = better function (9).

● CGI: SI (Severity, 1–7), GI (Global Improvement, 1–7), EI (Efficacy Index) (10).

● Statistical Analysis: Paired t-test compared baseline and 24-month outcomes. Cohen’s d computed for effect size.

Therapeutic intervention

Theoretical framework

Intervention was not grounded in formal psychodynamic psychotherapy. Rather, it was an integrative, person-centered approach, combining Narrative Therapy (externalization, re-authoring, unique outcomes) and the Satir Model (iceberg metaphor, family sculpting, self-worth enhancement). Psychoanalytic concepts (e.g., defense mechanisms, unconscious conflict) were used only for explanatory context.

Satir model in practice

The Satir Model, a systemic and experiential family therapy, aims to increase congruence, self-esteem, and family harmony by exploring communication stances, family roles, and emotional needs (6, 11). In this case, key techniques included the “iceberg metaphor” (exploring visible behavior vs. underlying emotions/needs) and family sculpting (mapping family dynamics).

Intervention phases

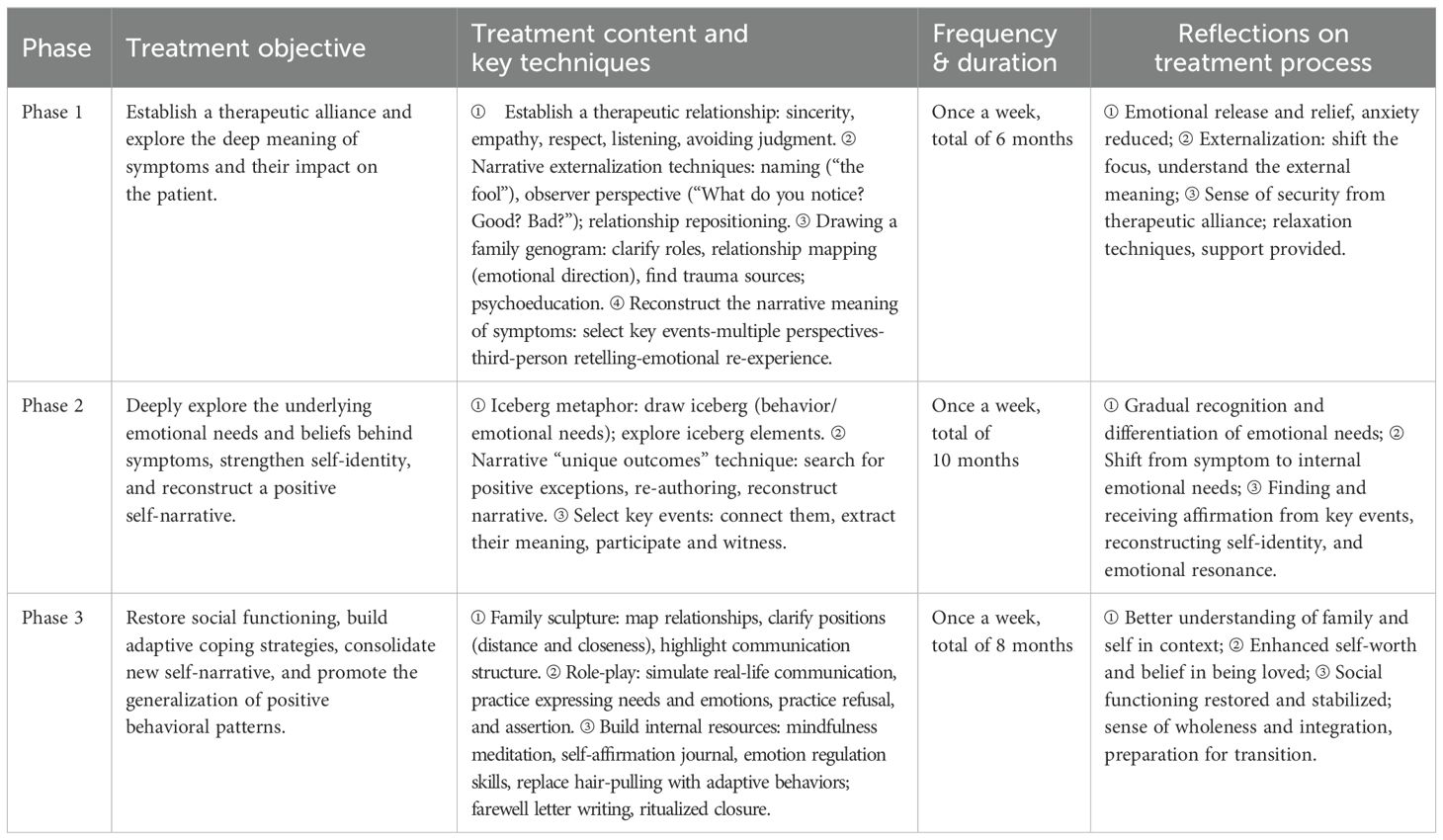

The integrated psychological intervention process for this patient is outlined in Table 2.

Phase 1: Symptom deconstruction (0–6 months)

● Establishment of alliance; externalization of hair-pulling (“Big Fool”).

● Genogram construction; trauma mapping; psychoeducation.

Phase 2: Cognitive/emotional reconstruction (7–16 months)

● Iceberg metaphor to connect behavior and emotional needs.

● Narrative “unique outcomes” and “re-authoring” to reconstruct self-identity.

Phase 3: Relationship remolding and social function restoration (17–24 months)

● Family sculpting and role-play to foster healthy communication.

● Mindfulness, self-affirmation journaling, ritual closure (farewell letter).

Results

Quantitative outcomes

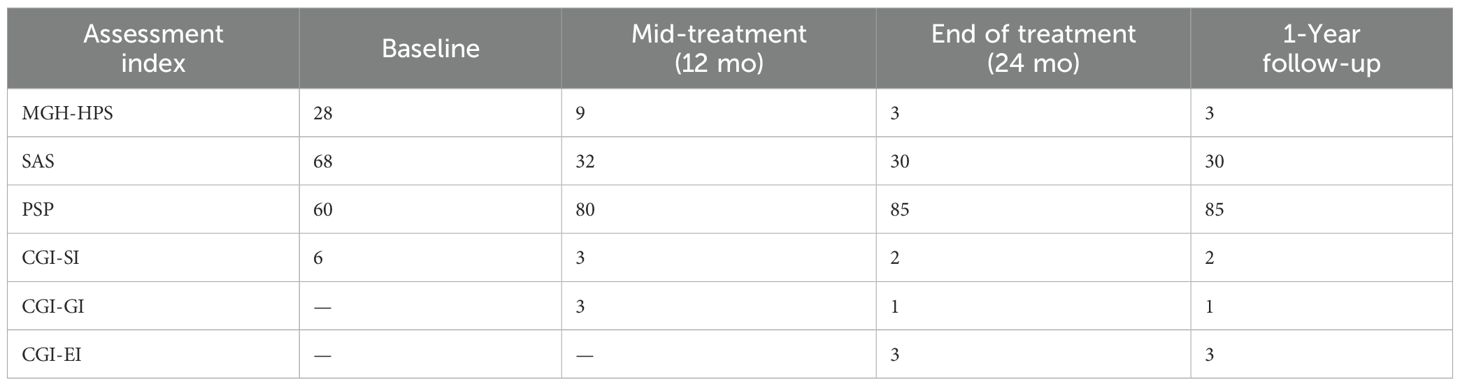

Key assessment scores at baseline, mid-treatment, end of treatment, and follow-up are presented in Table 3.

Statistical analysis

A paired samples t-test comparing baseline and post-treatment (24 months) MGH-HPS scores showed a significant reduction: t(1) = 7.07, p <.05; Cohen’s d = 2.65 (large effect size).

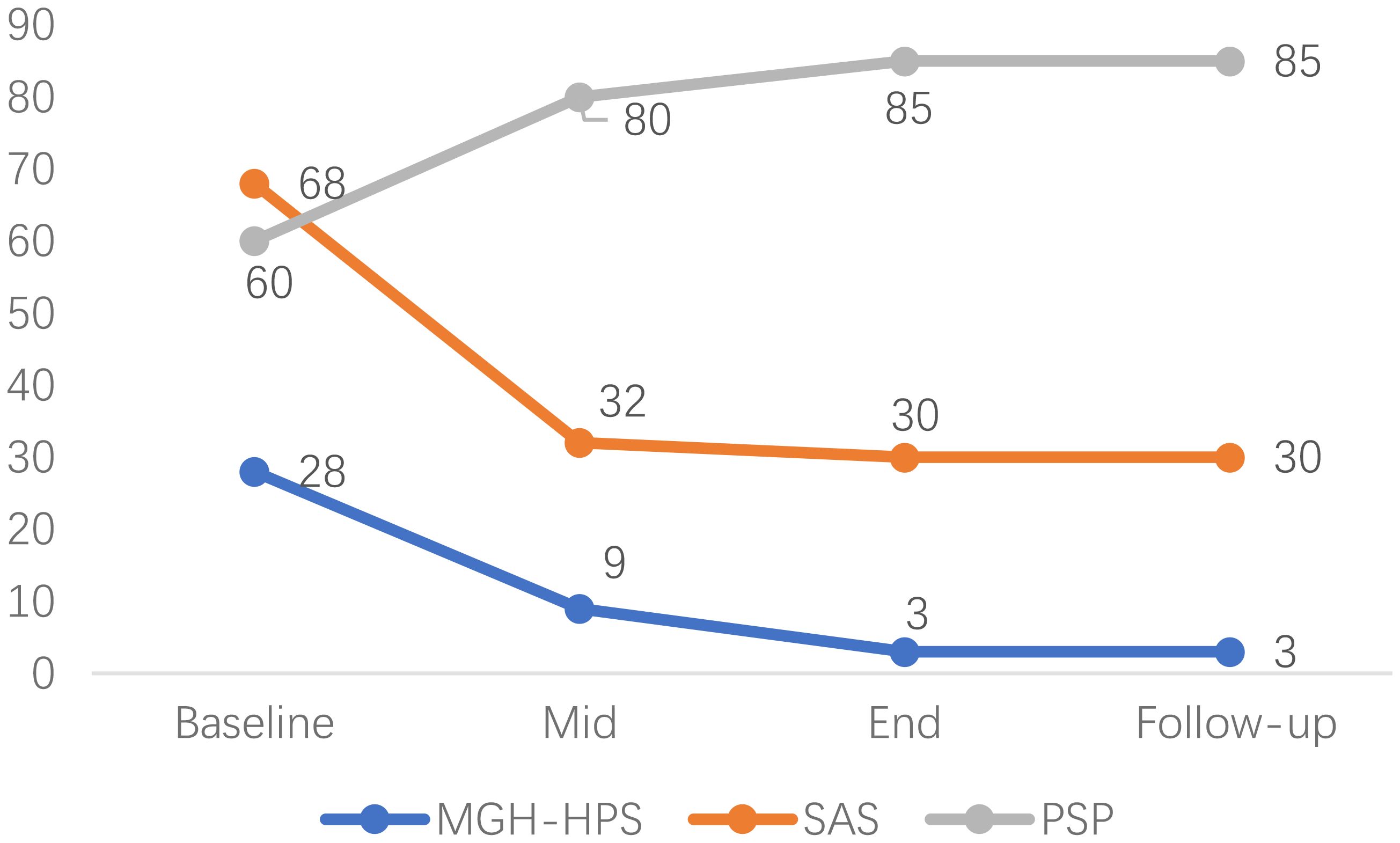

Visual timeline

A visual timeline of key assessment scores across treatment phases and follow-up is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visual timeline of key assessment scores (MGH-HPS, SAS, PSP) across treatment phases and follow-up.

Qualitative/functional outcomes

● Hair-pulling episodes reduced from 150/day to 5/day; normalized scalp appearance.

● Anxiety (SAS) decreased from severe (68) to mild (30).

● Social functioning (PSP) improved from impaired (60) to normal (85); secured stable employment; passed teacher qualification examination.

● Maintained gains at 1-year follow-up; rare, controlled relapses not affecting daily appearance or function.

Patient perspective

“Before therapy, I felt hopeless and ashamed. I always hid my bald patches with wigs, afraid of being found out. Over time, I understood my hair-pulling was not just a bad habit but a way I coped with pain and anxiety. Naming my problem and talking about my family helped me accept myself. Now, I can go out without a wig and am not ashamed. I believe I am capable and worthy, and I have plans for my future. Even when I feel the urge, I can control it.”

Discussion

This case illustrates the potential of integrating Narrative Therapy and the Satir Model for chronic trichotillomania. Despite the patient’s initial rejection of medication and cognitive restructuring therapy (12), an individualized, flexible approach achieved remission of hair-pulling symptoms, restored social function, and enhanced self-worth.

Theoretical integration: This intervention was guided by an integrative, not strictly psychodynamic, approach (13). Narrative Therapy and the Satir Model jointly addressed cognitive, emotional, and relational aspects, supporting sustained change, especially in culturally specific and resource-limited contexts.

Scales: The MGH-HPS, SAS, PSP, and CGI provided standardized, repeated measures of symptom severity, anxiety, and functioning. However, all were self-reported, and the patient’s desire to please the therapist may have introduced social desirability bias, especially in latter assessments.

Behavioral drives: While OCD and trichotillomania are often compared, their motivational drives differ: OCD behaviors are primarily anxiety-reducing, while hair-pulling can be both tension-reducing and pleasure-driven. In this case, initial relief from anxiety was reported, but over time, the behavior became a more complex means of emotional regulation and seeking control.

Limitations

● Single-case design: Generalizability is limited.

● Therapist bias: Strong alliance may have influenced patient responses and therapist ratings.

● Self-report instruments: Lack of third-party corroboration and potential for response distortion due to social desirability.

● No session fidelity monitoring: Treatment integrity was not formally measured.

Future directions: Larger, controlled studies with independent assessment and session fidelity are warranted. Exploring cultural adaptation and optimizing integrative protocols may improve accessibility and outcomes.

Conclusion

Integrative psychotherapy combining Narrative Therapy and the Satir Model may offer a valuable option for trichotillomania, especially when conventional approaches are declined. This case highlights the importance of person-centered, flexible, cross-theoretical interventions and the need for rigorous outcome monitoring and reporting in future research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

HL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. DW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HL:

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C., USA/Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

2. Hallopeau FH. Alopecie par grattage (trichomanie ou trichotillomanie). Bull la Société Française Dermatologie Syphiligraphie. (1889) 10:904–6.

3. Murase EM, Raygani S, and Murase JE. Narrative review of internet-based self-help tools for body-focused repetitive behaviors: recommendations for clinical practice. Dermatol Ther. (2025) 15:811–8. doi: 10.1007/s13555-025-01380-8

4. Franklin ME, Zagrabbe K, and Benavides KL. Trichotillomania and its treatment: A review and recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. (2011) 11:1165–74. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.93

6. Satir V, Banmen J, Gerber J, and Gomori M. The Satir Model: Family Therapy and Beyond. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Science and Behavior Books (1991).

7. Keuthen NJ, O’Sullivan RL, Ricciardi JN, Shera D, Savage CR, Borgmann AS, et al. The massachusetts general hospital (MGH) hairpulling scale: 1. Development and factor analyses. Psychother Psychosomatics. (1995) 64:141–5. doi: 10.1159/000289003

8. Zung WWK. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. (1971) 12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0

9. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, and Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2000) 101:323–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101004323.x

10. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338). Rockville, MD, USA: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (1976).

11. Khosravi M and Adibi A. STAIR plus narrative therapy-adolescent version (SNT-A) in an 11-year-old girl with PTSD and suicidal behaviors following rape/sexual assault: A case report. J Child Adolesc Trauma. (2022) 15:943–8. doi: 10.1007/s40653-021-00430-5

12. Whiting C, Azim SA, and Friedman A. Updates in the treatment of body-focused repetitive disorders. J Drugs Dermatol. (2023) 22:1069–70. doi: 10.36849/JDD.NVRN1023

Keywords: trichotillomania, integrative psychotherapy, narrative therapy, Satir model, case report

Citation: Liu H, Chen X, Wan X, Wang D and Chen Z (2025) Case Report: Narrative therapy combined with Satir model for the treatment of trichotillomania. Front. Psychiatry 16:1588939. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1588939

Received: 06 March 2025; Accepted: 14 August 2025;

Published: 02 September 2025.

Edited by:

Alberto Barceló-Soler, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by:

Alejandra Aguilar-Latorre, University of Zaragoza, SpainPrasad Kannekanti, King George’s Medical University, India

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Chen, Wan, Wang and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiguo Chen, NTYzODU1NjcxQHFxLmNvbQ==

Haiyan Liu

Haiyan Liu Xiuxiu Chen

Xiuxiu Chen