- College of Educational Science, Jiangsu Second Normal University, Nanjing, China

Background: Research has revealed that presence of meaning in life may be a protective factor for life satisfaction among young adults in China. However, few studies have examined the underlying mechanisms that may mediate or moderate this association. This study aimed to test the mechanisms underlying the relationship between meaning in life and life satisfaction among young adults in China.

Objective: This study aimed to examine the effects of presence of meaning in life on the life satisfaction among Chinese young adults, as well as the mediating role of perceived stress and moderating role of hope.

Methods: A total of 909 young adults in China completed measures of presence of meaning, perceived stress, hope and life satisfaction. The participants were recruited from four large public universities located in Jiangsu Province in China. SPSS statistical analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between presence of meaning in life, perceived stress, hope and life satisfaction.

Results: Presence of meaning in life was both positively associated with life satisfaction, controlling for grade and being from an urban or rural area (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). Perceived stress played a mediating role in the association between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.08, 95%CI = [0.05,0.13]). Furthermore, the interaction of presence of meaning in life and hope was positively related to life satisfaction (β = 0.14, p < 0.01) and the interaction of perceived stress and hope was positively related to life satisfaction (β = 0.11, p < 0.05). A high level of hope can enhance the link between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction while reduce the link between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Conclusion: Presence of meaning in life was positively associated with life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Furthermore, perceived stress played a mediating role in the association between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction, and this mediating effect was moderated by hope.

1 Introduction

Well-being is the ultimate goal of human action. With the rise and development of positive psychology, psychological research on well-being has significantly progressed. As a measure of subjective well-being, life satisfaction refers to an individual’s cognitive evaluation of their overall quality of life (1). As a core concept of positive psychology, life satisfaction is considered an influential predictor of psychological health among young adults (2). Life satisfaction may serve as a composite health indicator because life dissatisfaction has been found to be a predictor of disease mortality and have a long-term effect on the risk of suicide (3). Meanwhile, the studies indicated that life satisfaction has a significant negative predictive effect on negative mental health outcomes (4) and Chinese young adults’ internet addiction (5). As a cohort shaped by China’s rapid urbanization, educational hyper-competition, and stringent family expectations, Chinese young adults face unique socio-developmental challenges. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the mechanism of life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

1.1 Presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults

Meaning in life has been an eternal topic for humanity, and its exploration accompanies different stages of the life process. Research on meaning in life began in the 1950s. Subsequently, in-depth research on meaning in life has been conducted in various fields of psychology, especially positive psychology (6). Based on the integration of several influential concepts of meaning in life, Steger, Frazier and Oishi (7) defined it as an individual’s perception of the essence of human beings and their existence, as well as those that they consider to be more important. Meaning in life includes two dimensions: presence of meaning and search for meaning. Presence of meaning refers to the degree to which an individual perceives their life as meaningful, emphasizing the outcome. Search for meaning refers to the degree to which an individual actively seeks meaning in life, emphasizing the process.

Constructing meaningful interpretations is an effective coping strategy for dealing with stressors (8). In this regard, meaning in life can not only enhance an individual’s immune system and promote physical health, but also significantly improve subjective well-being and life satisfaction (9–11). A meta-analysis based on Chinese samples showed a significant positive correlation between meaning in life and life satisfaction (12). The study demonstrated that presence of meaning in life and search for meaning represent distinct psychological constructs, necessitating separate investigations of their respective associations with life satisfaction (13). Previous studies have consistently found a positive relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction (12, 14). Furthermore, a study indicated that a large proportion of the stable variance in presence of meaning and life satisfaction is shared (9). However, results from previous studies on the relationship between search for meaning in life and life satisfaction are equivocal. In one study, search for meaning in life significantly negatively predicted life satisfaction (7), whereas in another, it significantly positively predicted life satisfaction (15). Therefore, this study focused on exploring the mechanisms underlying the relationships between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction.

In particular, few studies have investigated the mechanism underlying the relationships between presence of or search for meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. To reveal these mechanisms, the present study constructed a moderated mediation model to examine the mediating role of perceived stress and moderating role of hope among, thus helping improve life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

1.2 Perceived stress as a mediator

When faced with the same stressor, different individuals often have different cognitions and reactions. The cognitive appraisal theory of stress posits that if an individual believes that the external environment poses a threat to them and they are unable to effectively respond, they have a negative reaction (16). However, if they believe they can overcome the stress, they exhibit a positive reaction (17). The theory provides an integrated framework for explaining the cognitive and reactive processes of individuals facing stressors and has been widely applied in the field of stress research. Perceived stress is a psychological response to a stressful life event after cognitive evaluation of the event (18). When facing a stressful event, young adults who perceive the event as more stressful are more likely to experience less life satisfaction (19). According to the cognitive appraisal theory of stress, when faced with stressors, individuals perform primary and secondary evaluations and adopt corresponding stress-coping styles, thereby affecting their psychological adaptation. As a component of subjective well-being, life satisfaction is considered an indicator of positive adjustment. It is a cognitive evaluation of one’s life (20), which is subjective. When individuals appraise a stressor as a threat to their life, it inevitably affects their evaluation of their quality of life. Therefore, high levels of perceived stress can have a negative effect on life satisfaction. Indeed, Hamarat et al. (21) found that perceived stress is a better predictor of life satisfaction for younger adults. A recent empirical research has also indicated that perceived stress is a significant negative predictor for Chinese emerging adults’ life satisfaction (22).

The meaning-making model states that meaning includes both global and situational meaning. Global meaning refers to an individual’s general orienting system and consists of beliefs, goals, and presence of meaning, whereas situational meaning refers to meaning in the context of a particular environmental encounter (8). According to this model, perceived stress fundamentally arises from an inconsistency between the situational meaning individuals ascribe to stressors and their stable, internalized global meaning. A high level of presence of meaning—serving as a foundational element of global meaning—provides individuals with a clear, stable, and coherent cognitive framework. This framework promotes the appraisal of stressors as manageable challenges rather than fundamental threats, thereby reducing situational-global meaning discrepancies and ultimately lowering perceived stress levels. A study indicated that participants with lower levels of meaning in life reported greater stress than those who reported higher meaning in life (23). A recent study found that presence of meaning in life demonstrates a significant negative predictive effect on perceived stress, whereas search for meaning in life does not (24). Therefore, we speculated that perceived stress may mediate the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

1.3 Hope as a moderator

Hope is defined as a cognitive set comprising agency (the belief in one’s capacity to initiate and sustain actions) and pathways (the belief in one’s capacity to generate routes) to reach goals. It is a potential psychological strength that may serve as a protective factor for adolescents facing adverse life events (25). The Strengths theory posits that a psychological strength is a person’s natural capacity to behave, think, or feel in a way that enables their optimal functioning and performance in the pursuit of valued outcomes (25). People who identify and use their strengths were found to report higher levels of subjective and psychological well-being and experience less stress (26). Recent empirical studies have found that hope, as a psychological strength, could significantly positively predict young adults’ life satisfaction after the COVID-19 outbreak (27).

Although a higher presence of meaning can significantly reduce individuals’ perceived stress levels—thereby enhancing life satisfaction—the negative impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction may still vary considerably across different individuals when confronting intractable stressors. In such case, the moderating role of hope as a psychological strength becomes critical. Hope has been found to buffer the negative impact of risk factors on psychological development (28). Moreover, a longitudinal study has provided evidence of the functional role of hope as a moderator in the relationship between stressful life events and adolescent well-being (25). When experiencing perceived stress, individuals with high levels of hope can leverage their strong pathways thinking to conceive multiple effective coping strategies while utilizing agency thinking to sustain effort and confidence in implementation. This psychological strength enables them to more effectively manage stressful experiences, thereby buffering the erosive effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction. Therefore, we speculated that hope may moderate the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

According to the protective factor-protective factor model, when two protective factors impact the dependent variable, they may interact (29). As such, the predictive effect of a protective factor (e.g., meaning in life) on an outcome variable (e.g., life satisfaction) may be moderated by another protective factor (e.g., hope). There are two hypotheses for this interaction: the promotion hypothesis and exclusion hypothesis. The promotion hypothesis refers to one protective factor enhancing the predictive effect of another protective factor on an outcome variable, whereas the exclusion hypothesis refers to one protective factor weakening the predictive effect of another protective factor on an outcome variable (30). For example, hope (a protective factor) can enhance the impact of parent-child communication (another protective factor) on children’s prosocial behavior. Therefore, we hypothesized that the moderating effect of hope in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction may be explained by the promotion hypothesis. Specifically, hope would enhance the effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction of Chinese young adults.

In summary, we proposed the following four hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: Presence of meaning in life will positively predict life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

Hypothesis 2: Perceived stress will mediate the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

Hypothesis 3: Hope will moderate the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Specifically, the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction will be weaker for Chinese young adults with higher hope.

Hypothesis 4: Hope will moderate the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Specifically, the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction will be stronger for Chinese young adults with higher hope.

1.4 The Present study

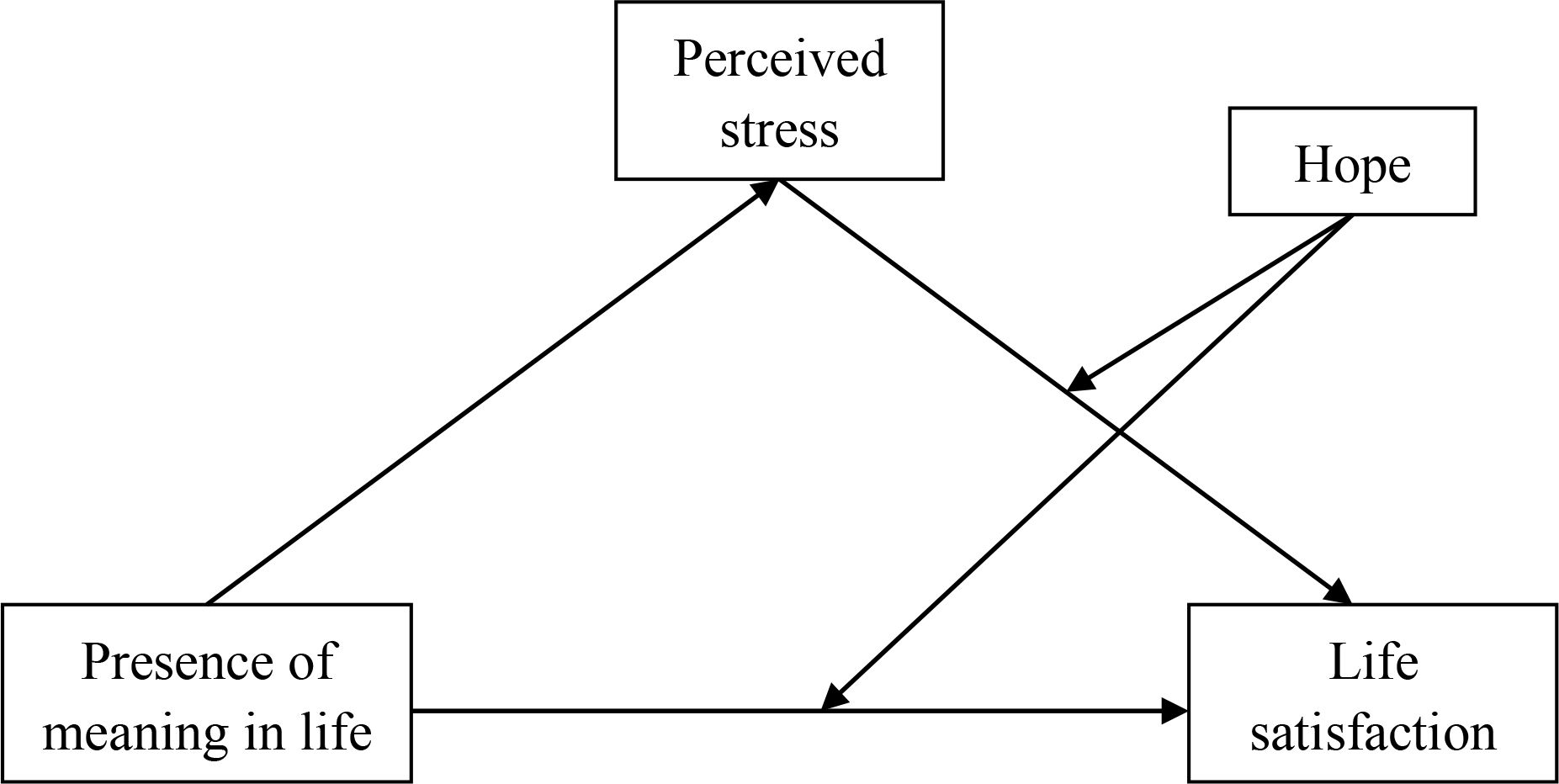

This study tested the mechanisms underlying the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. we examined a moderated mediation model to answer three questions: (a) Does perceived stress mediate the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults? (b) Does hope moderate the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction? (c) Does hope moderate the mediating effect of perceived stress in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction? (see Figure 1).

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

A total of 909 young adults were selected through stratified random sampling. They were recruited from four large public universities located in Jiangsu Province in China. The mean age was 20.97 years (SD = 1.31) and their ages ranged from 19–22 years. The sample consisted of 333 (36.63%) men and 576 (63.37%) women. A total of 423 (46.53%) participants were from urban families and 486 (53.47%) were from rural families. Regarding the year of study, 237 (26.07%) were freshmen, 246 (27.06%) were sophomores, 219 (24.09%) were juniors, and 207 (22.77%) were seniors.

2.2 Measurements

2.2.1 Presence of meaning in life

The Presence of Meaning Subscale of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) was administered to assess meaning in life among Chinese young adult (31). This subscale has 5 items. Items are responded to using a 7-point scale (1 = never, 7 = always). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.78. Confirmatory factor analysis further indicated that the one-factor model demonstrated a good fit to the data (x2/df = 5.58, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05, and RMSEA = 0.04).

2.2.2 Perceived stress

The Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale (CPSS) was used to measure perceived stress (32). This scale has 14 items and two subscales: Perceived Anxiety and Perceived Loss of Control. Items are responded to using a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = always). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.81 for the CPSS, 0.78 for Perceived Anxiety, and 0.84 for Perceived Loss of Control. Confirmatory factor analysis further indicated that the two-factor model demonstrated a good fit to the data (x2/df = 5.19, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.05, and RMSEA = 0.06).

2.2.3 Hope

The Chinese version of the Hope Scale (CHS) was used to assess hope (33). This scale has 12 items, of which 8 items assess two factors of hope: agency and pathways. The other four items are distracter items. Items are responded to using a 4-point scale (1 = definitely false, 4 = definitely true). Higher scores reflect higher levels of hope. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.88 for the CHS, 0.83 for the Agency subscale, and 0.80 for the Pathways subscale. Likewise, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the two-factor model demonstrated a good fit to the data (x2/df = 4.72, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.06, and RMSEA = 0.06).

2.2.4 Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to measure life satisfaction (34). The SWLS has five items that are responded to using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores reflect higher life satisfaction. The SWLS demonstrated good reliability and validity in a Chinese sample (35). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.85. Likewise, confirmatory factor analysis further indicated that the one-factor model demonstrated a good fit to the data (x2/df = 4.97, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04, and RMSEA = 0.05).

2.3 Procedure

Participants were recruited from four universities located in the two cities of Nanjing and Taizhou, China. The quantitative data were collected by administering a survey questionnaire to the participants in their classrooms at the university during school hours. Each class was provided with two trained psychology graduate students who were responsible for helping students with completing the questionnaire. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and the questionnaire was anonymous.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 and the SPSS macro PROCESS (http://www.afhayes.com) from Hayes (36). First, we calculated descriptive statistics to determine the characteristics of the sample. Second, we performed Pearson’s correlation analysis to evaluate the relationships between the variables, where gender and from an urban or rural area were transformed into dummy variables. Third, we used PROCESS Model 4 and Model 15 to test the moderated mediation model involving perceived stress and hope in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction.

3 Results

3.1 Common method bias

To ensure the reliability of the research findings, common method bias was assessed following Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations (37). An unrotated exploratory factor analysis employing Harman’s single-factor test (38) was conducted on all study variables. Results indicated the extraction of 11 factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0. The first factor accounted for only 20.85% of the total variance, well below the critical threshold of 40%. These findings indicate no significant common method bias in this study.

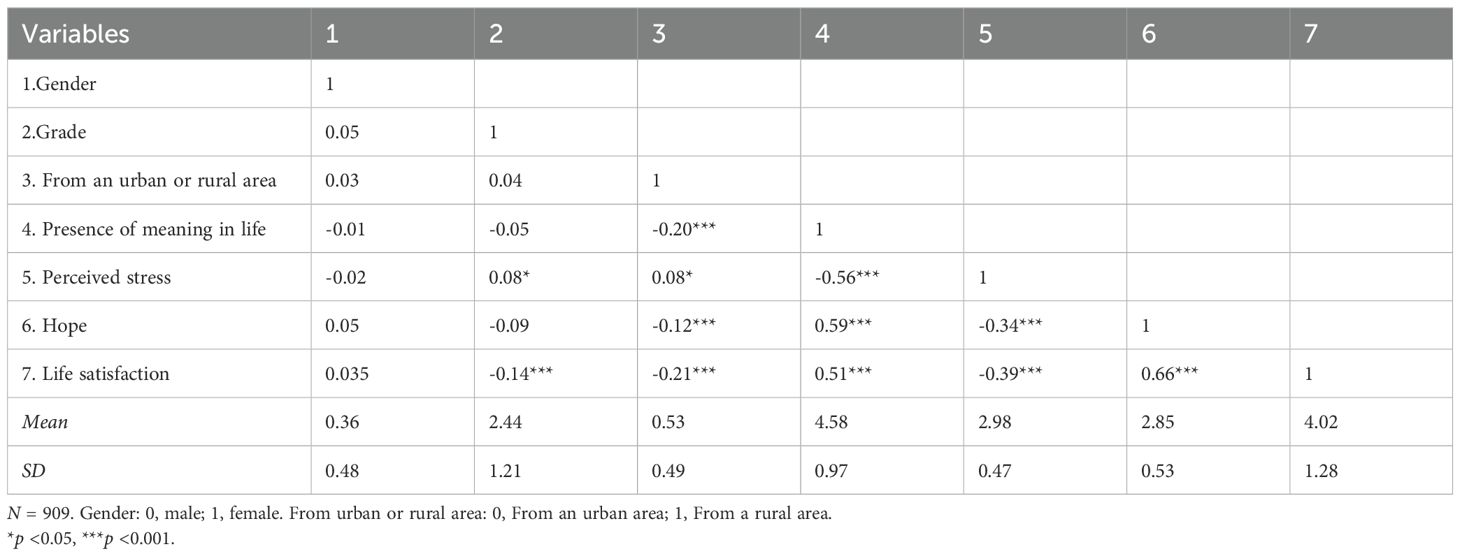

3.2 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables. Grade positively correlated with perceived stress (p < 0.05) and negatively correlated with life satisfaction (p < 0.001). Being from an urban or rural area was negatively correlated with presence of meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction (p < 0.001), but positively correlated with perceived stress (p < 0.05). Presence of meaning in life was positively correlated with hope, and life satisfaction (p < 0.001), but negatively correlated with perceived stress (p < 0.001). Perceived stress was negatively correlated with hope and life satisfaction (p < 0.001), and hope was positively correlated with life satisfaction (p < 0.001).

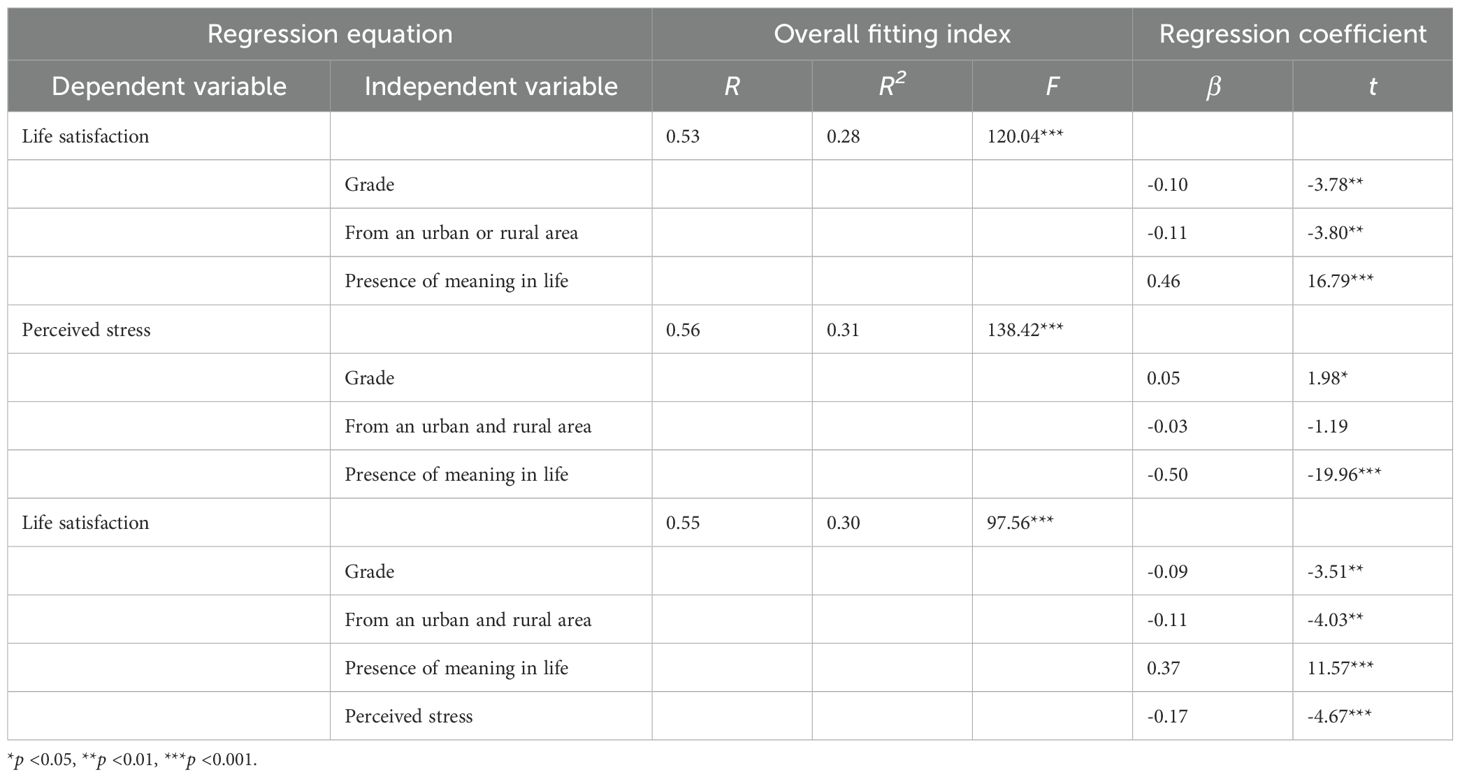

3.3 Conceptual model testing

PROCESS Model 4 was used to test the mediating effect of perceived stress in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction. Grade and being from an urban or rural area were controlled for, and the main variables were standardized. The results are presented in Table 2. Presence of meaning in life was positively correlated with life satisfaction (β = 0.46, p < 0.001), which supported for Hypothesis 1. After adding the mediator, the direct relationship was weakened (β = 0.37, p < 0.01). Presence of meaning in life was negatively associated with perceived stress (β = -0.50, p < 0.001), and perceived stress was negatively associated with life satisfaction (β = -0.17, p < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the results of the bootstrapping analyses indicated that perceived stress partially mediated the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.08, Boot LLCI = 0.05, Boot ULCI = 0.13).

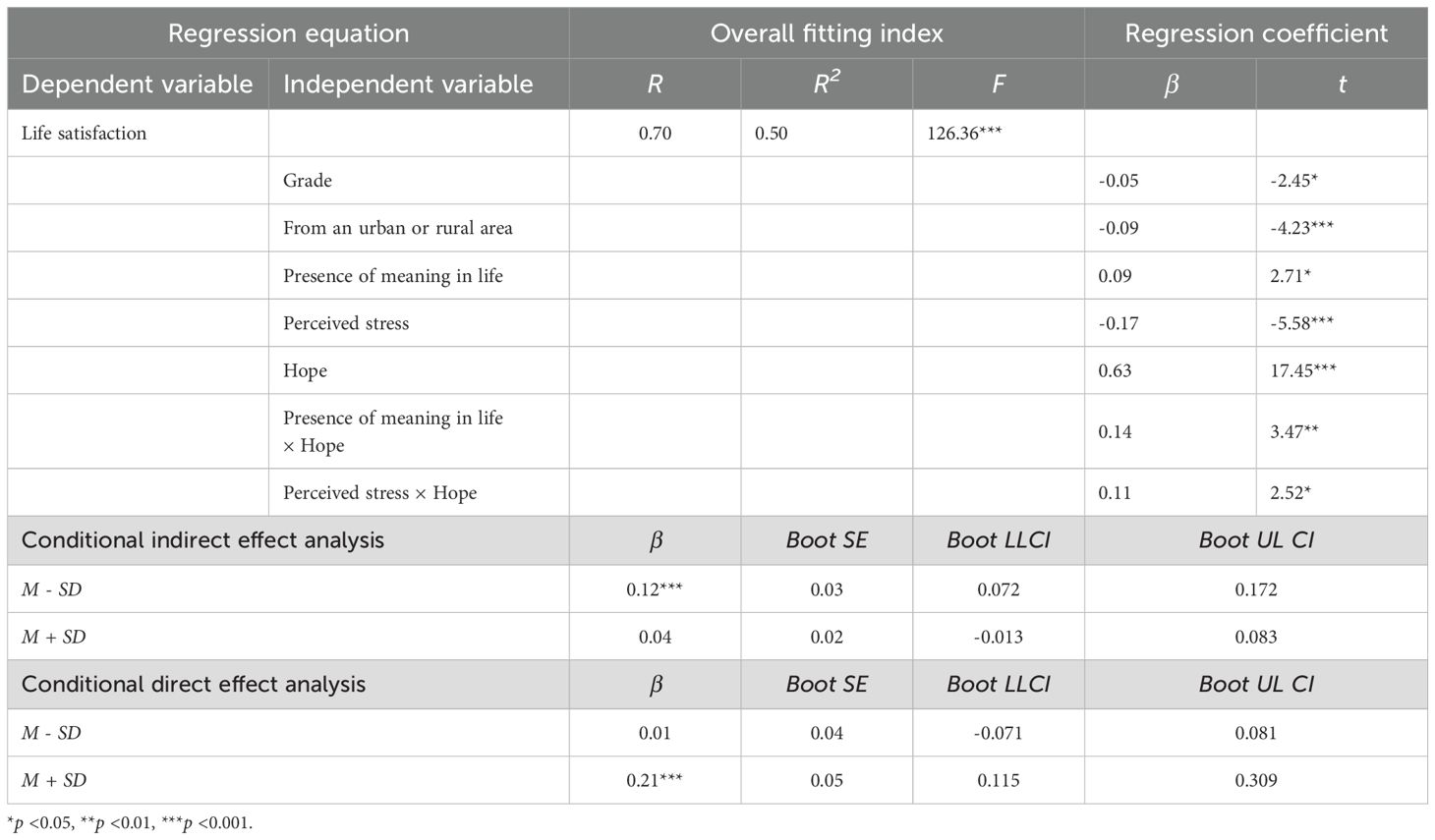

PROCESS Model 15 was used to test the moderated mediation model involving perceived stress and hope in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction after controlling for year of study and being from an urban or rural area. The main variables were standardized. The results are presented in Table 3. The interaction of perceived stress and hope had a significant effect on life satisfaction (β = 0.11, p < 0.05). The interaction of presence of meaning in life and hope also had a significant effect on life satisfaction (β = 0.14, p < 0.01).

Table 3. Moderated mediation analysis for presence of meaning in life, perceived stress, hope, and life satisfaction.

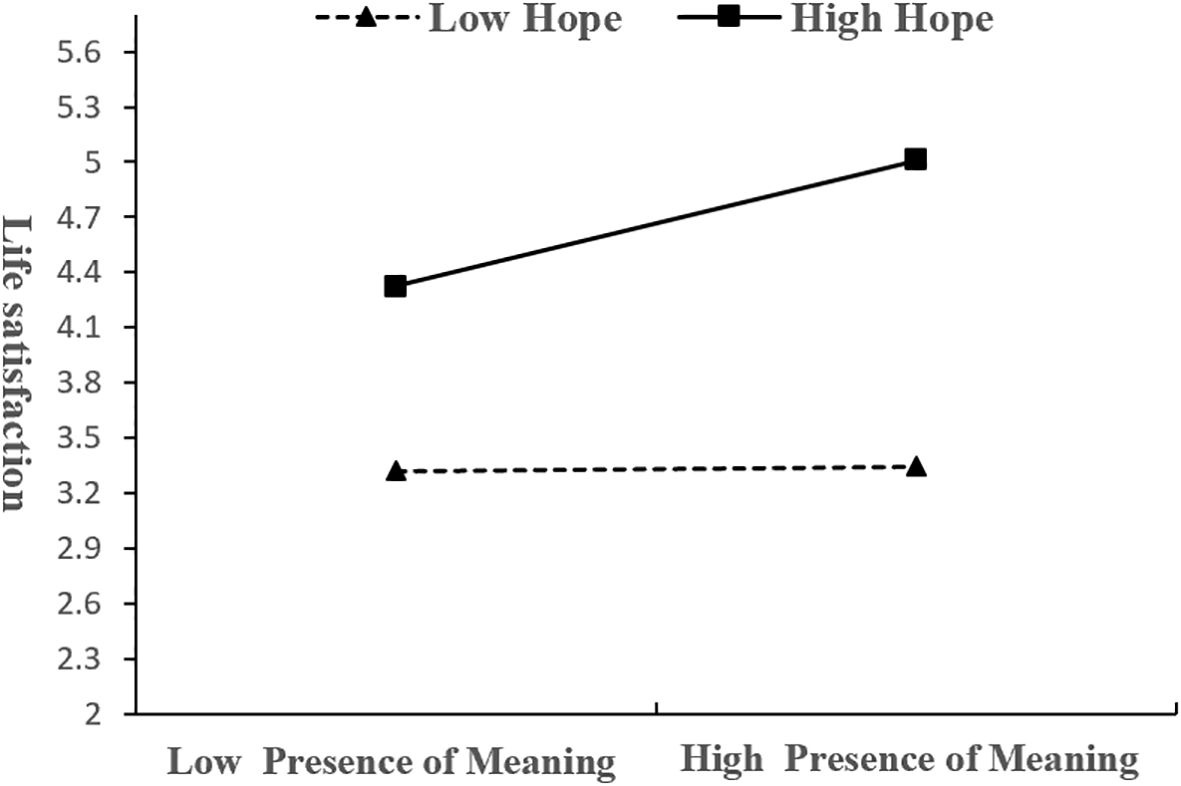

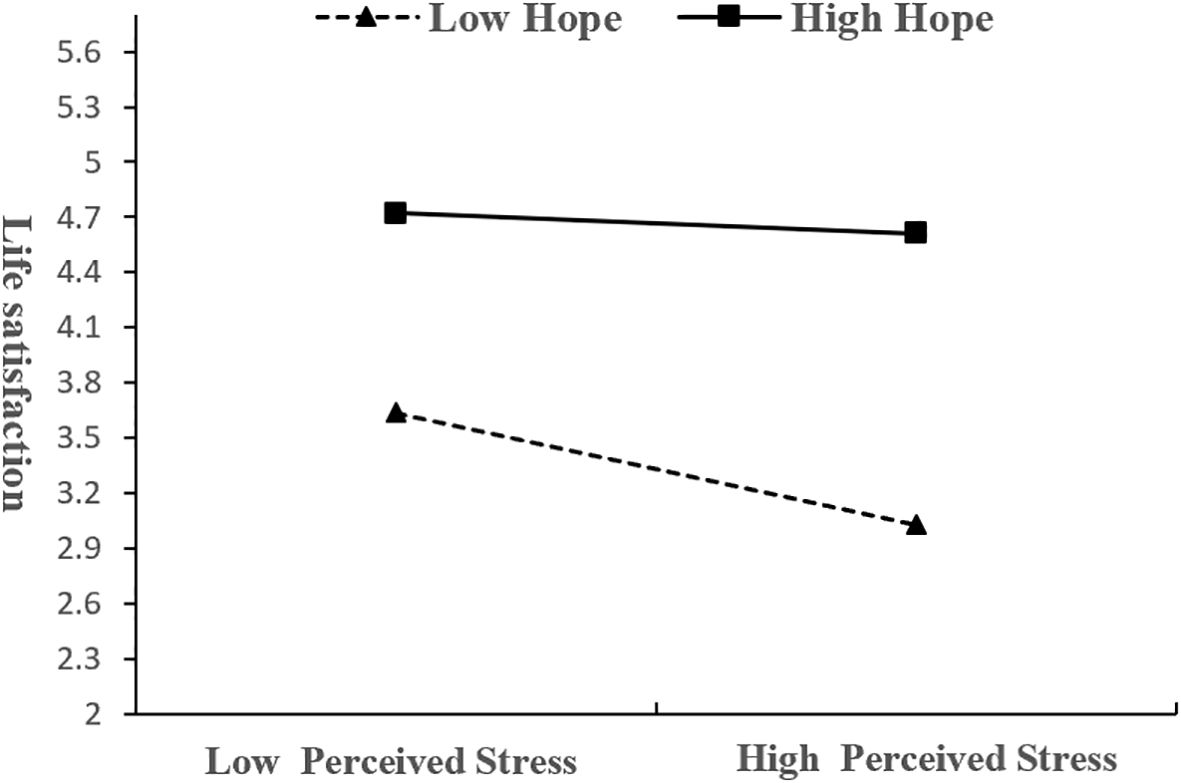

Simple slopes tests were used to interpret the significant interactions, and hope scores were dichotomized as low (M - SD) or high (M + SD). As shown in Figure 2, the predictive effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction was significantly stronger for individuals with high hope (β = 0.35, t = 5.22, p < 0.001) than for those with low hope (β = 0.01, t = 0.23, p = 0.82), indicating that increase in hope enhanced the effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction. Meanwhile, the predictive effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction was weaker for individuals with high hope (β = -0.11, t = -0.95, p = 0.33), and the predictive effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction was stronger for individuals with low hope (β = -0.63, t = -6.03, p < 0.001), indicating that increase in hope weakened the effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction (Figure 3). The effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction and the 95% bootstrap values are shown in Table 3. The findings demonstrated that the mediating role of perceived stress in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction was moderated by hope. Specifically, perceived stress fully accounted for this relationship at lower levels of hope (β= 0.12, 95%CI [0.072, 0.172]), whereas this mediating pathway was nonsignificant at elevated hope levels (β= 0.04, 95%CI [-0.013, 0.083]). Thus, Hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of hope on the relationship between the presence of life meaning and life satisfaction.

Figure 3. Moderating effect of hope on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

4 Discussion

The present study constructed a moderated mediation model to examine the mechanisms underlying the relationship between the presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. The results indicated that perceived stress played a mediating role in the association between the presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction, and this mediated relationship was moderated by hope.

4.1 Presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults

Building upon prior research (13), we investigated presence of meaning in life as separate constructs and explored its relationships with life satisfaction. The results showed that presence of meaning in life positively predicted life satisfaction among Chinese young adults, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (13, 15). Presence of meaning in life is a cognitive dimension that provides people with an overall framework for understanding themselves, the world, and the relationship between themselves and the world (39). When people have a meaning in life, they make more positive and meaningful cognitive evaluations of their lives and adopt positive coping strategies to cope with the stressors (40), which ultimately contributes to their satisfaction with life.

4.2 The mediating role of perceived stress

The findings suggest that perceived stress mediates the association between the presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Specifically, young adults who reported higher levels of meaning in life demonstrated lower perceived stress, which in turn was associated with greater life satisfaction. This can be attributed to the tendency of individuals with established life meaning to engage in more positive cognitive appraisals of life circumstances and employ adaptive coping strategies when confronting stressors (40). In line with the cognitive appraisal theory of stress, individuals initially conduct primary appraisal (assessing threat significance) followed by secondary appraisal (evaluating coping resources), ultimately determining their stress-coping approaches and subsequent psychological adaptation outcomes (16, 17). During the primary appraisal stage, individuals with a higher presence of meaning in life demonstrate a greater tendency to perceive stressors as opportunities for fulfilling life goals and actualizing personal values, rather than mere threats. This positive primary appraisal significantly attenuates perceived threat severity, thereby reducing perceived stress. At the secondary appraisal stage, presence of meaning provides robust psychological resources and coping efficacy. When confronting stressors, young adults with high levels of presence of meaning actively mobilize personal resources and employ diversified adaptive coping strategies, empowered by the conviction and motivation derived from their presence of meaning. These effective strategies facilitate practical problem-solving and diminish perceived stress levels. As perceived stress decreases, negative emotions subside while positive affect and psychological resources are restored and enhanced. This process fosters more favorable evaluations across life domains, ultimately elevating life satisfaction.

4.3 The moderating role of hope

The present study also indicated that hope not only moderated the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction, but also the mediating effect of perceived stress in the relationship.

Firstly, the effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction strengthened as hope increased. This result confirms the promotion hypothesis of the protective factor-protective factor model. Snyder et al. (41) pointed out that individuals with high levels of hope have clear future goals and can adopt various methods to overcome the obstacles in the process of achieving goals. For individuals with high levels of hope, presence of meaning can increase positive and constructive behaviors, thereby enhancing their sense of value and improving their level of life satisfaction. Conversely, young adults with diminished hope levels exhibit attenuated benefits from presence of meaning in life, likely due to deficient life goal articulation and limited utilization of adaptive problem-solving approaches when confronting challenges. The study have further shown that, in the long run, life satisfaction is deeply influenced by individual life goals (42). The absence of life goals might undermine the directional focus of proactive behaviors and impair problem-solving efficacy, thereby disrupting the effective translation of presence of meaning into sustained psychological benefits and ultimately constraining the enhancement of life satisfaction. Therefore, for young adults with low levels of hope, the effect of presence of meaning in life on life satisfaction was weaker.

Secondly, our study found that hope moderates the effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction, indicating that the effect of perceived stress weakened as hope increased. This result validates the protective factor model (43), which means that as a protective factor for young adults, hope could effectively buffer the adverse effects of risk factors such as perceived stress on their mental health and further promote their resilience. Hope refers to the strength of individuals to face the future (44). Individuals with high levels of hope tend to focus more on achieving future goals rather than on their current state. Even if they encounter various pressures while pursuing goals, they would actively take measures to minimize them and successfully achieve their goals. Therefore, for young adults with high levels of hope, perceived stress has less impact on their life satisfaction. Thus, hope may buffer the effects of perceived stress on life satisfaction.

Moreover, our study found that perceived stress exhibit a complete mediating effect in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction for Chinese young adults with low hope levels, but not for those with high hope levels. According to Snyder’s hope theory, young adults with low hope levels often fail to translate abstract meaning in life into specific behavioral strategies when facing stressful events due to the lack of pathways thinking. This inability promotes the elevation of perceived stress, which reduces their life satisfaction. In this case, presence of meaning in life remains confined to the conceptual level, unable to directly enhance life satisfaction due to its failure to drive substantive behaviors that would otherwise improve satisfaction. Therefore, for Chinese young adults with low hope levels, perceived stress exhibits a complete mediating effect in the relationship between presence of meaning and life satisfaction. Conversely, young adults with high hope levels can transform presence of meaning in life into operational coping strategies through pathways thinking and agency thinking. This transformation process allows presence of meaning to act directly on life satisfaction bypassing the mediation of perceived stress. In other words, for these young adults, presence of meaning in life itself becomes a tool to cope with stressful events, rather than indirectly enhancing life satisfaction by reducing perceived stress. Therefore, for Chinese young adults with high hope levels, perceived stress does not exhibit a significant mediating effect in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction.

4.4 Implications

To our knowledge, our study is the first to focus on the underlying influence of perceived stress and hope in the association between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults in the context of the meaning-making model and the strengths theory. This study provides a new perspective on the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Another contribution of this study is in expanding our understanding of well-being and resilience among non-Western young populations. The present research found that, in the context of Chinese culture, hope, as a protective factor, could enhance the impact of presence of meaning in life (another protective factor) on life satisfaction among young adults and effectively buffer the adverse effects of risk factors such as perceived stress on their life satisfaction. Moreover, the results can be used to guide future interventions aimed at improving life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Firstly, educators can increase the levels of presence of meaning in life to improve life satisfaction among young adults through various intervention strategies, such as Satir model group intervention. According to a recent study, Satir model group intervention can significantly improve the levels of presence of meaning in life among Chinese young adults (45). Secondly, we can enhance life satisfaction among Chinese young adults by cultivating their hope through targeted interventions. Substantial empirical evidence demonstrates that young adults’ hope levels can be significantly elevated via interventions such as group counseling programs (46, 47).

4.5 Limitations

Several limitations of the present study need to be highlighted. First, the sample was derived from four large public universities located in Jiangsu Province, China, which may not represent all young adults. Therefore, future studies should expand the sample. Second, this study employed a cross-sectional design, which precludes definitive causal inferences between the variables. Future research may employ a three-wave longitudinal tracking design and apply cross-lagged panel models to establish causal relationships. Third, self-report methods were used for data collection, which can be affected by social desirability bias and recall bias (48). Future investigations should adopt multimodal data collection approaches, integrating cross-channel data such as physiological indicators, behavioral observations, and multi-source reports to establish methodological triangulation.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the roles of perceived stress and hope in the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. The results indicated that presence of meaning in life was positively associated with life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Furthermore, perceived stress played a mediating role in the association between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction, and this mediating effect was moderated by hope. Overall, the results of this study provide a new perspective for exploring the relationship between presence of meaning in life and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults. Interventions to enhance presence of meaning in life and hope, as well as reduce perceived stress, are potential strategies to help increase life satisfaction among Chinese young adults.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Yan Zhang, cGV0ZXJ6aGFuZzExMDhAMTYzLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Nanjing Brain Hospital (2022-KY139-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YZ: Writing – original draft. BJ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. TL: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Humanity and Social Science Planning foundation of Ministry of Education, China (grant number: 22YJA880087); Key Project of “14th Five-Year” Planning of Education Science in Jiangsu Province, China (grant number: B-b/2024/01/39); Research Project on Teaching Reform of Jiangsu Second Normal University, China (grant number: JSSNUJXGG2023YB01); and Jiangsu Provincial College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program, China (grant number: 202414436049Y).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Diener E. Subjective well-being. psychol Bulletin. (1984) 95:542–75. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

2. Fatima I, Naeem MW, and Raza HMZ. Life satisfaction and psychological wellbeing among young adults. World J Advanced Res Rev. (2021) 12:365–71. doi: 10.30574/wjarr.2021.12.2.0599

3. Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkanen R, and Koskenvuo M. Life dissatisfaction as a predictor of fatal injury in a 20-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2002) 105:444–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01287

4. Padmanabhanunni A, Pretorius TB, and Isaacs S. A. Satisfied with life? The protective function of life satisfaction in the relationship between perceived stress and negative mental health outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:6777–89. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20186777

5. Zhou HY, Liang YY, and Liu XM. The impact of life satisfaction on college students’ internet addiction: multiple mediating effects of social support and self-esteem. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2020) 28:919–23. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.05.012

6. Stephens NM, Fryberg SA, and Markus HR. Who explains Hurricane Katrina and the Chilean earthquake as an act of God? The experience of extreme hardship predicts religious meaning-making. J Cross-Cultural Psychol. (2013) 44:606–19. doi: 10.1177/0022022112454330

7. Steger MF, Frazier P, and Oishi S. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. (2006) 53:80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

8. Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. psychol Bulletin. (2010) 136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301

9. Steger MF and Kashdan TB. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. J Happiness Stud. (2007) 8:161–79. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8

10. Doğan T, Sapmaz F, and Tel FDS. Meaning in life and subjective well-being among Turkish university students. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. (2012) 55:612–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.543

11. Yuan WW, Zhang XH, Meng KB, and Xu R. The influence of family function on college students’ life satisfaction: chain mediating effect of meaning of life and psychological resilience. China J Health Psychol. (2024) 32:498–502. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2024.04.004

12. Jin Y, He M, and Li J. The relationship between the meaning of life and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis based on the Chinese sample. Adv psychol Science. (2016) 24:1854–63. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.01854

13. Park N, Park M, and Peterson C. When is the search for meaning related to life satisfaction? Appl Psychology: Health Well-Being. (2010) 2:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01024.x

14. Dong X and Geng L. The role of mindfulness and meaning in life in adolescents’ dispositional awe and life satisfaction: the broaden-and-build theory perspective. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:28911–24. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03924-z

15. Zhao D, Wang Y, and Li J. The mediating role of coping strategies in the relationship between life satisfaction and life meaning among master’s students. Chin J Health Psychol. (2014) 22:1733–35. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2014.11.053

16. Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am Psychol. (1991) 46:819–34. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

17. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, and Gruen RJ. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1986) 50:571–79. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571

18. Cohen S, Kamarck T, and Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. (1983) 24:385–96. doi: 10.2307/2136404

19. Civitci A. Perceived stress and life satisfaction in college students: Belonging and extracurricular participation as moderators. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. (2015) 205:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.077

20. Diener E and Suh E. Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Soc Indic Res. (1997) 40:189–216. doi: 10.1023/A:1006859511756

21. Hamarat E, Thompson D, Karen Z, and Aysan F. Perceived stress and coping resource availability as predictors of life satisfaction in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Exp Aging Res. (2001) 27:181–96. doi: 10.1080/036107301750074051

22. Petrus Yat-nam NG, Yang S, and Chiu R. Features of emerging adulthood, perceived stress and life satisfaction in Hong Kong emerging adults. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:20394–406. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05811-1

23. Park J and Baumeister RF. Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. J Positive Psychol. (2017) 12:333–41. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1209542

24. Hashemikamangar S and Afshari A. Predicting role of resilience and meaning in life in perceived stress of frontline health care workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Soc Sci Humanity. (2022) 12:24–8. doi: 10.18178/ijssh.2022.V12.1060

25. Valle MF, Huebner ES, and Suldo SM. An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. J school Psychol. (2006) 44:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.03.005

26. Wood AM, Linley PA, Maltby J, Kashdan TB, and Hurling R. Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Pers Individ differences. (2011) 50:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.004

27. Wider W, Taib NM, Khadri MW, Yip Y, Lajuma S, and Punniamoorthy PAL. The unique role of hope and optimism in the relationship between environmental quality and life satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:7661–72. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19137661

28. Jiang Y, Ren Y, Liang Q, and You J. The moderating role of trait hope in the association between adolescent depressive symptoms and nonsuicidal self-injury. Pers Individ Differences. (2018) 135:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.010

29. Fergus S and Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. (2005) 26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

30. Bao ZZ, Zhang W, and Li DP. The relationship between campus atmosphere and adolescent academic achievement: a moderated mediation model. psychol Dev Education. (2013) 29:61–70. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.01.005

31. Liu SS and Gan YQ. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Scale among college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal. (2010) 24:478–82.

32. Liu WT, Yi JY, and Zhong MM. The measurement equivalence of the Perceived Stress Scale among college students of different genders. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2015) 23:944–47. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.05.043

33. Chen. CR, Shen HY, and Li XC. Reliability and validity of adult dispositional hope scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal. (2009) 17:24–8.

34. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, and Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers assessment. (1985) 49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

35. Yang Q and Ye BJ. The impact of gratitude on adolescent’ life satisfaction: the mediating role of social support and the moderating role of stressful life events. Psychol Sci. (2014) 37:610–16. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.03.018

36. Hayes AF and Scharkow M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? psychol science. (2013) 24:1918–27. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187

37. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, and Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

39. Heine SJ, Proulx T, and Vohs KD. The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Pers Soc Psychol review. (2006) 10:88–110. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

40. Thompson NJ, Coker J, Krause JS, and Henry E. Purpose in life as a mediator of adjustment after spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. (2003) 48:100–19. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.48.2.100

41. Snyder CR, Ilardi SS, Cheavens J, Michael ST, Yamhure L, and Sympson S. The role of hope in cognitive-behavior therapies. Cogn Ther Res. (2000) 24:747–62. doi: 10.1023/A:1005547730153

42. Diener E, Fujita F, Tay L, and Biswas-Diener R. Purpose, mood, and pleasure in predicting satisfaction judgments. Soc Indic Res. (2012) 105:333–41. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9787-8

43. Garmezy N, Masten AS, and Tellegen A. The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Dev. (1984) 55:97–111. doi: 10.2307/1129837

44. Pacico JC, Bastianello MR, Zanon C, and Hutz CS. Adaptation and validation of the dispositional hope scale for adolescents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica. (2013) 26:488–92. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000300008

45. Chen XZ, Yang JL, and Yang XJ. Enhancing effect of Satir model group intervention on life meaning among college students. China J Health Psychol. (2022) 30:256–60. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.02.020

46. Bernardo AB and Sit HY. Hope interventions for students: Integrating cultural perspectives. In: Promoting motivation and learning in contexts: Sociocultural perspectives on educational interventions. Charlotte, North Carolina, USA: Information Age Publishing. (2020). p. 281–302.

47. Li YH. Evaluation of group counseling intervention effects on hope traits among college students. China J School Health. (2019) 40:134–7. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2019.01.038

Keywords: presence of meaning, perceived stress, hope, life satisfaction, young adults

Citation: Zhang Y, Jiang B, Lei T and Yan Y (2025) The relationship between presence of meaning and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults: a moderated mediation model of perceived stress and hope. Front. Psychiatry 16:1610440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1610440

Received: 12 April 2025; Accepted: 30 July 2025;

Published: 25 August 2025.

Edited by:

Padmavati Ramachandran, Schizophrenia Research Foundation, IndiaReviewed by:

Xiaojing Yuan, Nanjing Normal University, ChinaWentao Xu, Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University, China

Changying Zhang, Jiangsu University of Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Jiang, Lei and Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Zhang, UGV0ZXJ6aGFuZzExMDhAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Yan Zhang

Yan Zhang Bo Jiang†

Bo Jiang†