- 1Reproductive Medicine Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China

- 2National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Study on Abnormal Gametes and Reproductive Tract, Hefei, Anhui, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Hefei, Anhui, China

- 4Reproductive Medicine Center, The Affiliated Jinyang Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, The Second People’s Hospital of Guiyang, Guiyang, China

Aim: Despite having been introduced into ICD-11, the appropriate classification and symptomatology of compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) remain controversial.

Methods: In this review, we examined the historical background, epidemiological status quo, comorbidities, neuroscience theories, current diagnoses, and treatment recommendations for CSBD. Additionally, we emphasized the limitations of the current research and the prospects for future work.

Results: Psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are the preferred treatment methods for CSBD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and naltrexone are commonly used as “off-label” drugs. The diagnosis and treatment of patients with CSBD should integrate biological, psychological, and social factors with expertise in sexual medicine by employing a comprehensive and holistic therapeutic approach. This treatment aims not only to control abnormal sexual desires and behaviors but also to assist patients in achieving a healthy and satisfying sexual life and well-being.

Conclusion: Future research should focus on understanding etiology, improving study population representation, correcting methodological flaws in treatment evaluation, enhancing clinician training in sexual medicine, and addressing patients’ addictions and sexual function issues. Narrowing these research gaps is crucial for improving clinical diagnosis and treatment levels and formulating targeted social intervention measures.

1 Introduction

For over four decades, the etiology and biological underpinnings of uncontrollable sexual behavior have been the subject of intense academic debate, continuing to this day (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) recently recognized the diagnosis of compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, https://icd.who.int/).

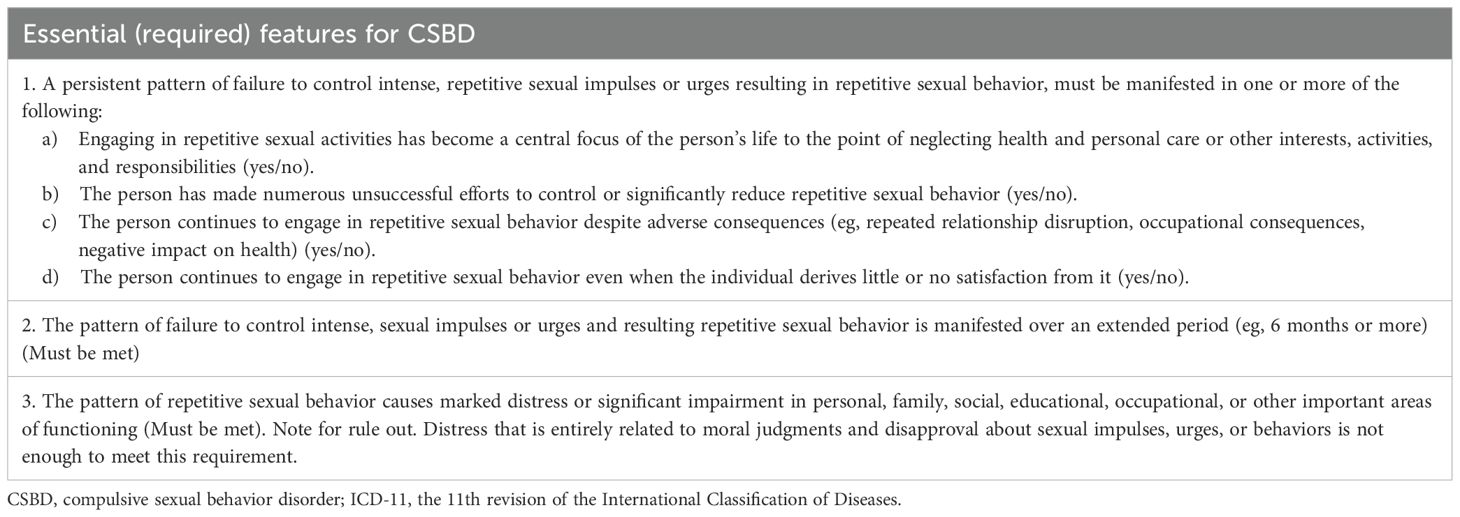

In the ICD-11, CSBD is characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges, leading to repetitive sexual behaviors. These behaviors persist for six months or more and cause significant distress or impairment in critical areas of psychosocial functioning. The complete diagnostic criteria for this disorder are listed in Table 1. The establishment and discussion of diagnostic criteria for CSBD have advanced research into developing etiological models and refining treatment approaches. The inclusion of CSBD in the ICD-11 resulted in a significant impact on clinical practice and research.

This review provides an overview of the current knowledge status of CSBD, with an emphasis on understanding the limitations of the current research and prospects for future work. In this review, compulsive sexual behavior (CSB), defined as challenges in controlling inappropriate or excessive sexual fantasies, urges/cravings, or behaviors that cause subjective distress or impair daily functioning, will be explored, along with its potential correlations with gambling and substance addictions (2). In the context of CSB, intense and repetitive sexual fantasies, urges/cravings, or behaviors may escalate over time and have been associated with health, psychosocial, and interpersonal impairments.

For this narrative review, we conducted a comprehensive literature search using databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The search timeframe was set from the inception of relevant research up to January 2025, with a focus on studies published in English. We employed keywords such as “compulsive sexual behavior”, “compulsive sexual behavior disorder”, “sexual addiction”, “hypersexuality”, and “CSBD treatment”. Although this review follows a narrative approach rather than a formal systematic review framework, we adopted principles of critical appraisal to select high-quality studies, including original research articles, review papers, and clinical guidelines. All titles and abstracts were reviewed for inclusion, followed by full paper review for studies that appeared to meet criteria. No specific scoping review model was strictly applied; instead, we prioritized seminal works, recent advancements, and studies addressing the review’s objectives on limitations and future directions.

2 Historical development

Research into excessive desire behaviors, including excessive craving for sex, began to emerge in the early 20th century. Early psychoanalysts observed and commented on cases where individuals developed excessive sexual desire (3). In the United States, the concept of sexual addiction first emerged in the context of CSB management and became deeply entrenched in the self-help methodologies of 12-step groups (4). This program, originally established by Bill Wilson in the 1930s to address alcohol misuse, eventually expanded to cover various addictions, leading to the creation of Sex Addicts Anonymous in 1977. In 1983, Patrick Carnes published “Out of the Shadows: Understanding Sexual Addiction,” introducing the concept of sexual behavior addiction to a broad clinical audience. This seminal work, grounded in clinical case reports and theoretical conjectures, rather than empirical evidence, has faced significant criticism (5). Nevertheless, research on excessive, addictive, or compulsive sexual behaviors continued to grow throughout the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by case reports, theoretical speculations, and narrative descriptions (6).

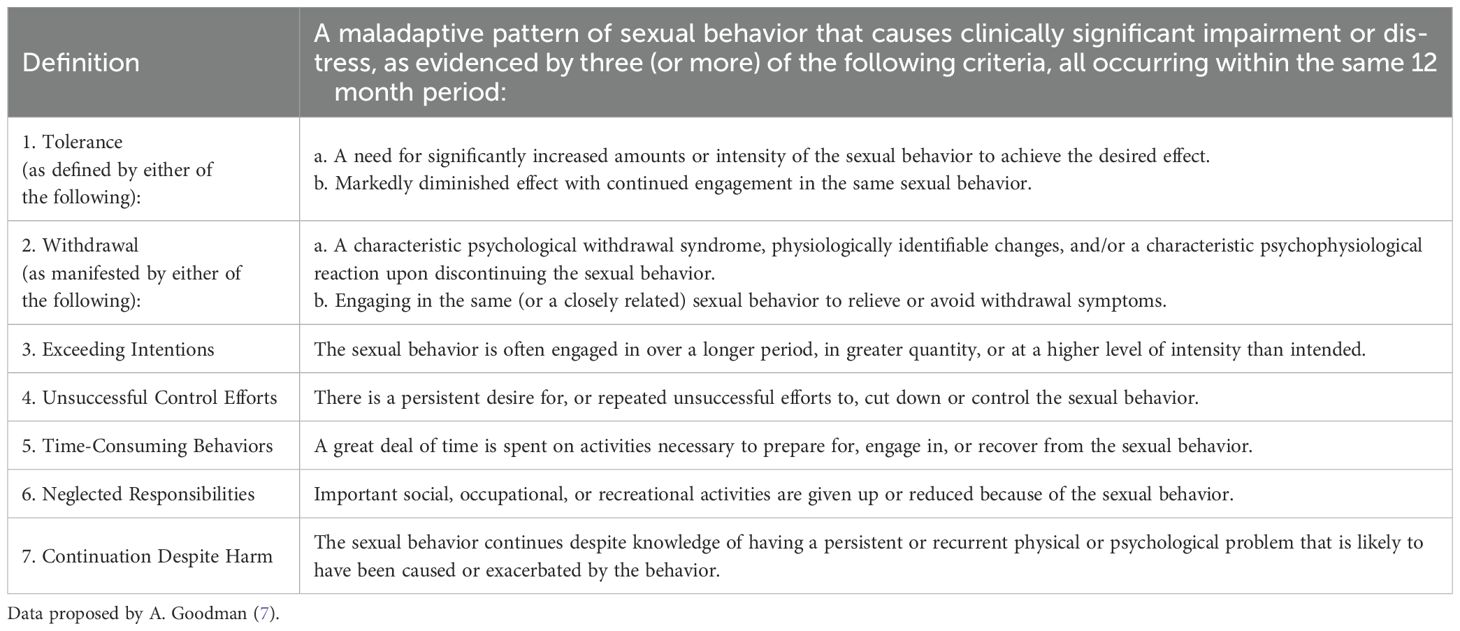

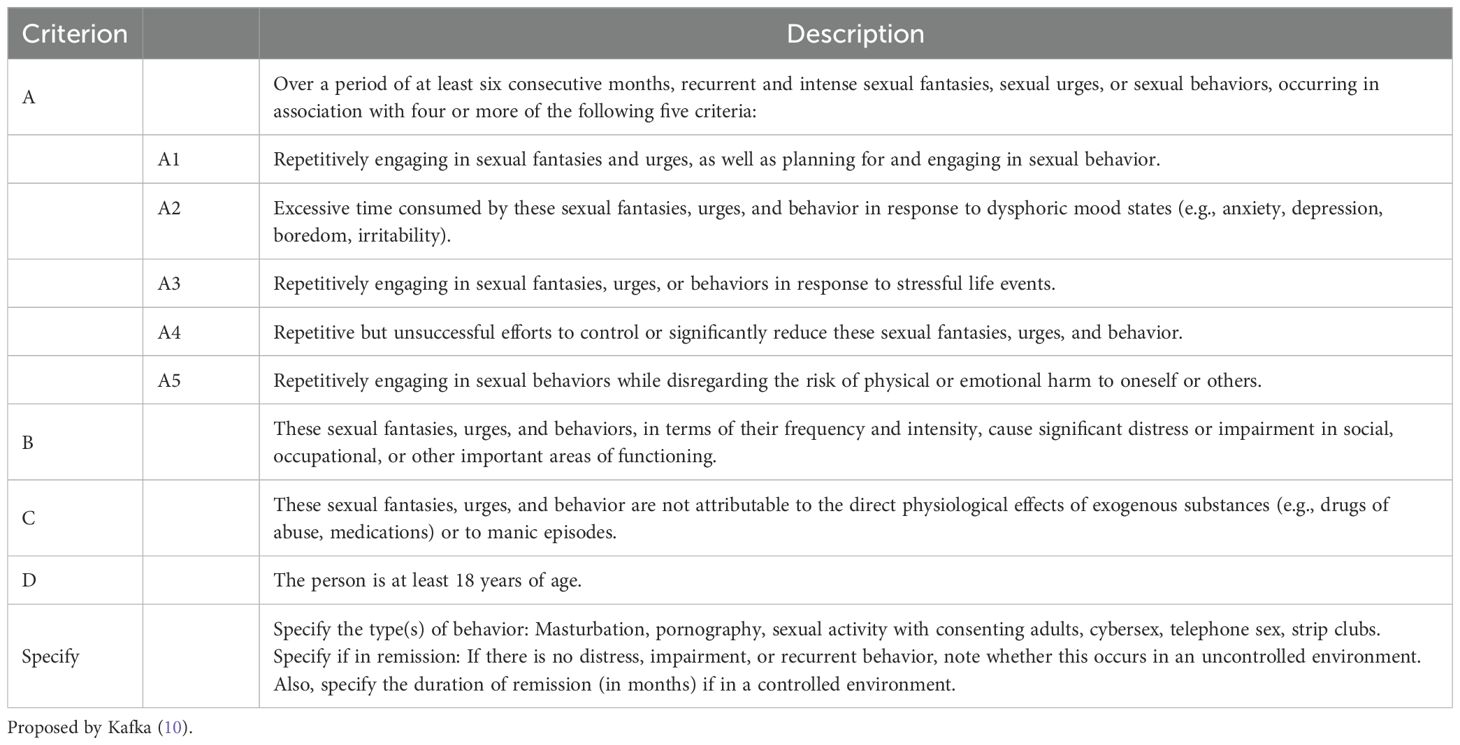

Efforts have been made in the field of psychiatry to establish diagnostic criteria related to sexual addiction. Psychiatrist Ariel Goodman proposed diagnostic criteria for sexual addiction based on the current diagnostic standards for substance abuse disorders, such as tolerance, withdrawal, and disruption of social and occupational functions (Table 2) (7). Carnes and his colleagues developed several self-report screening tools, such as the 25-item Sexual Addiction Screening Test and a brief screening test known as “PATHOS” (8). In 2006, Mick and Hollander introduced the term “impulsive-compulsive sexual behavior” to describe patients who exhibit impulsive traits at the onset of their behavior and compulsive traits when dysfunctional behavior persists (9). The growing attention to these empirical studies eventually led to the proposal of “Hypersexual Disorder” as a potential diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), emphasizing the possibility of some individuals exhibiting uncontrollable sexual behavior with symptom patterns very similar to those seen in gambling and substance use disorders (Table 3) (10).

Table 3. Hypersexual Disorder Diagnostic Criteria (The diagnosis of Hypersexual Disorder should meet both criteria B, C, and D, and at least four of the five criteria listed under subcategory A).

In light of new evidence from extensive research on excessive and uncontrollable sexual behaviors, the WHO’s Working Group on Impulse Control Disorders suggested the inclusion of the new diagnosis CSBD in the ICD-11 in 2018 (11). After considerable deliberation and public commentary, this disorder was ultimately included in the ICD-11 as an impulse control disorder (12). Although the diagnosis of CSBD is new, it essentially represents a reclassification of an old phenomenon. Excessive sexual behavior, hypersexuality, CSBD, and sexual addiction are different terms for the phenomenon of excessive sexual behavior, reflecting various theoretical frameworks for understanding this behavior (10, 13).

3 The epidemiology of CSBD

Previous epidemiological data on CSBD were mostly fragmented and criticized for methodological limitations, including non-representative samples and questionable diagnostic indicators (14). The incidence rates of CSBD vary significantly (15). In Western developed countries, 8–13% of men and 5–7% of women meet the diagnostic criteria for CSBD (16).

A recent large study involving 4,633 individuals from the general German population reported a lifetime CSBD prevalence of 4.9% in men and 3.0% in women (17). In the largest study to date that defined and operationalized CSBD according to the ICD-11 guidelines, researchers used data from the International Sex Survey (n=82,243) to validate the original version (CSBD-19) and the short version (CSBD-7) of the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale and compared CSBD risks across 42 countries, three genders, and eight sexual orientations (18). The study found that the global incidence rate of CSBD is approximately 5%. Country- and gender-based differences in CSBD levels were observed, but no differences were found based on sexual orientation. These variations may reflect cultural attitudes toward sexuality. For example, a study in Germany reported a lifetime prevalence of 4.9% in men and 3.0% in women, while region-specific data suggest that societies with stricter sexual morality may underreport CSBD due to stigma, or overreport it due to cultural guilt (17, 18). In addition, only 14% individuals with CSBD sought treatment.

These epidemiological findings may serve as a basis for promoting research on the prevention and intervention strategies for CSBD. Considering the compromised sexual health and well-being of individuals with CSBD, this is a serious public health issue given its current known prevalence.

4 The comorbidities of CSBD

The comorbidity rate between CSBD and other mental disorders is quite high. Mood disorders, particularly depression, are the most commonly associated conditions with CSBD (19). Anxiety disorders, particularly generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder, also frequently coexist with CSBD (20). Additionally, Wery et al. reported a high suicide risk among individuals with CSBD. Several studies reported that the most common personality types associated with CSBD are histrionic, paranoid, avoidant, obsessive-compulsive, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive (21, 22).

The association between bipolar disorder and CSBD is complex. In clinical practice, CSB frequently occurs alongside mania and hypomania (23). A meta-analysis of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder revealed that approximately 31–45% of adolescents experience CSB during manic episodes (24). A recent meta-analysis discovered that CSB emerged as a prodromal symptom before the first manic episode in 17% of patients with bipolar disorder, and is one of the most common symptoms before recurrent bipolar mood disorders (25). Some studies suggest that patients with CSB may exhibit more symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD). However, these symptoms are not severe enough to be classified as a formal diagnosis of ADHD (26).

Previous studies have also linked compulsivity to CSB (27). Compulsivity may also reflect habitual behaviors with little or no pleasure, as reflected in the CSBD criteria. Bothe et al. found a small but significant association between compulsivity and CSB in a sample of 13,778 men and women from the general population (28). However, a recent study of 539 outpatients with current impulse control disorders (OCD) (51.8% were females) found that only 5.6% had been diagnosed with CSBD and 3.3% had current CSBD. This suggests that the prevalence of CSB among patients with OCD may be comparable to that in the general population (29). Despite the use of the term compulsivity in the diagnostic category, CSBD is not considered a subtype of OCD. In contrast to CSBD, compulsive behaviors in OCD are usually a response to intrusive, unwanted, and anxiety-provoking thoughts, and are not considered pleasant.

CSB often co-occurs with behavioral addictions. In a study in Brazil that included 458 patients with gambling disorders, 6.4% reported CSB that met the criteria for mental disorders (30). Grant et al. reported that 19.6% of 225 gamblers exhibited CSBs, suggesting that similar physiological and psychological processes are associated with these two addictive behaviors. In 70.5% of patients with comorbidities, compulsive sexual behavior preceded pathological gambling, suggesting a shared mechanism of brain dysfunction (31).

CSB also frequently coexists with substance use disorders (SUDs). More than 40% of patients with CSBs are diagnosed with additional SUDs, with alcohol use disorder being the most common. Additionally, cocaine abuse was reported to be more prevalent among men with CSB than among those with paraphilias (32). Furthermore, the use of drugs such as methamphetamine, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid, and alkyl nitrates to facilitate participation in sexual activities or enhance their pleasure, described as “chemsex,” may also lead to out-of-control and dangerous sexual behaviors (33).

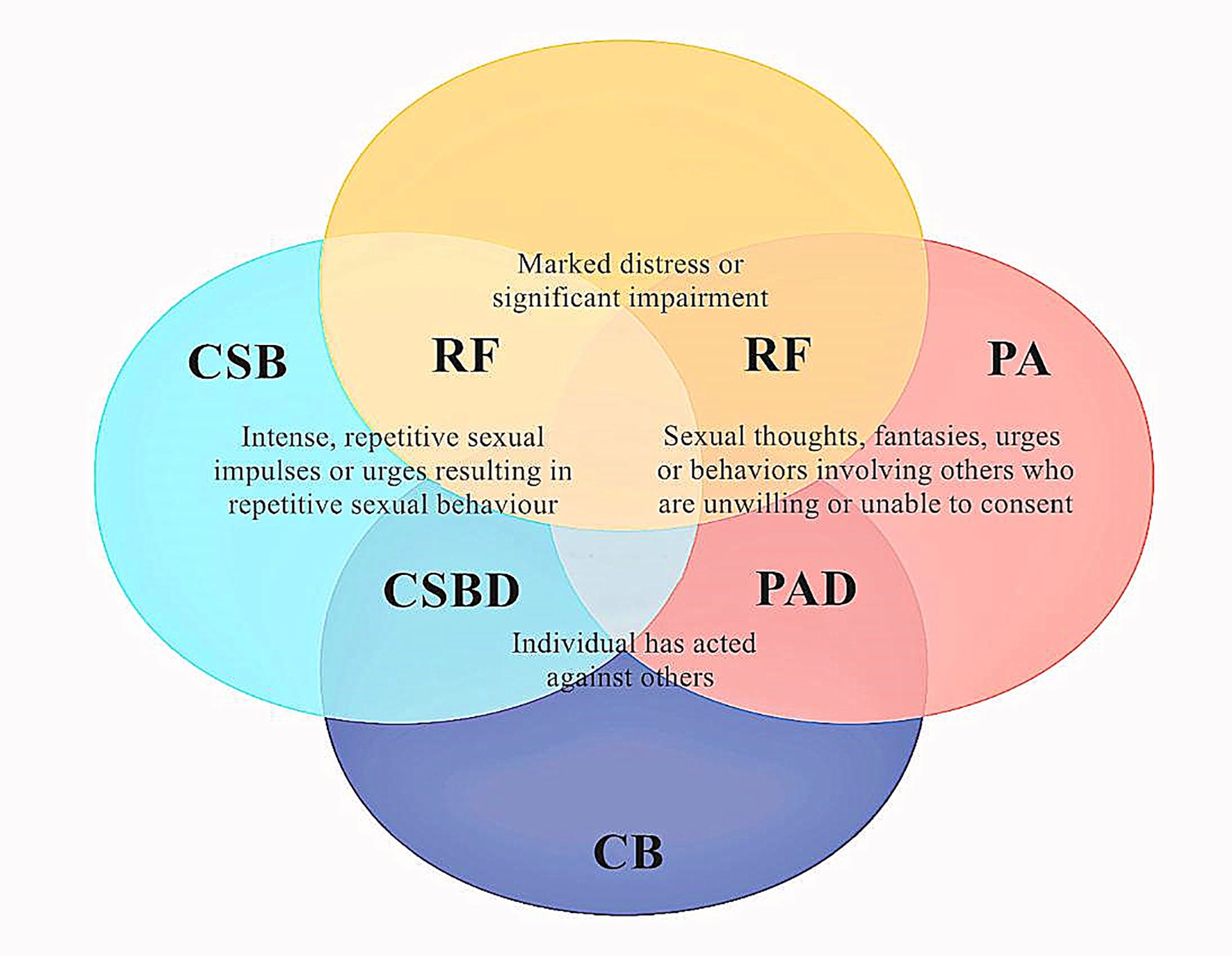

Paraphilic disorders represent another diagnostic entity that partially overlaps with CSBD. CSBD is characterized by normal sexual fantasies, whereas paraphilia is characterized by paraphilic fantasies, sexual urges, and sexual behaviors (34). The term “paraphilia” is limited to sexual behavior that involves patterns of sexual arousal directed primarily at non-consenting others or that is associated with substantial distress or an immediate risk of harm or death (35) (Figure 1). One diagnosis does not necessarily exclude the other, as they may exist as comorbid conditions in up to 30% of the cases (32, 36). According to the ICD-11, CSBD will not be diagnosed if an individual can exert some degree of control over their arousal patterns.

Figure 1. The link between paraphilia and compulsive sexuality and their association with sexual delinquency and distress. Psychological distress is a core disorder criterion for both CSBD and paraphilic disorders. CB, criminal behavior; PA, paraphilia; PAD, paraphilic disorder; RF, risk factor for sexual reoffending.

In conclusion, CSB often co-occurs with depression, anxiety, specific personality disorders, impulse control, addiction, and substance abuse. CSB may also appear as a symptom of other mental disorders, complicating the differential diagnosis in some patients. In such cases, the pattern of substance use and its relationship with sexual behavior (motivation, sequencing, and impact) should be carefully investigated. Differential diagnosis is crucial because whether CSBD is classified as a distinct medical condition or as part of another mental health disorder will influence the treatment methods. It is worth noting that CSB is also often accompanied by negative emotional states, interpersonal problems, financial difficulties, or unemployment, which in turn may have a negative impact on the symptoms of co-occurring emotional or anxiety disorders (37, 38). This may constitute a vicious cycle, leading to the persistence of CSB symptoms and co-occurring diseases.

5 The neurobiology of CSBD

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying CSBD and their differentials are important for determining the classification of CSBD.

Sexual pleasure is associated with the neural reward system, such as the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (39). According to the “salience incentive theory of addiction” (40), this neural activity is more about craving (“wanting”) for hedonic stimuli rather than the enjoyment or pleasure (“liking”) itself. This theory suggests that the pathological activation of the dopamine-”wanting” system underlies addictive behaviors. Neuroimaging studies indicate that patients with CSBD exhibit heightened reactivity in the limbic (wanting) region of the midbrain, similar to substance addiction. For instance, Voon et al. demonstrated that sexual cues led to greater corticostriatal activity among patients with CSBD than among healthy control participants (41). Specifically, enhanced activity was detected in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, ventral striatum, and amygdala. This pathway implies more “wanting” (as opposed to “liking”) arousal by patients with CSBD in response to sexual cues. Gola et al. revealed that, compared to control participants, individuals with problematic pornography use displayed greater neural activation in response to cues predicting sexual stimuli (42). This disparity was not observed when reacting to actual sexual stimuli, suggesting differences in “wanting” rather than in “liking.” These findings support the CSBD model of addiction. Klucken et al. reported slightly different results: patients with CSBD exhibited greater activity in the amygdala in response to conditioned stimuli than did the controls. However, no differences in the ventral striatum were identified between CSBD and control participants (43).

In addition to variations in cue activation between CSBD and control participants, differences in brain structure have also been noted. Volumetric differences in the striatum have been linked to SUDs, but findings are mixed, with some studies reporting decreased gray matter volume and others reporting an increase. Seok et al. also detected gray matter enlargement in the right cerebellar tonsil among patients with CSBD and those with OCD (44). Schmidt et al. found an increased volume in the amygdala, which is associated with motivational salience and emotional processing (45). They observed different results in alcohol addiction and suggested that this discrepancy might be attributed to alcohol neurotoxicity.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) is an MRI technique that examines the integrity of the white matter by measuring the self-diffusion of water in the brain tissue. Miner et al. found no differences in DTI measures between patients with CSBD and control participants (46). However, some differences were observed in the superior frontal region, resembling patterns seen in patients with OCD, which may also imply that CSBD aligns more closely with the OCD model.

A more recent study examined men with CSBD (n=26), gambling disorder (n=26), alcohol use disorder (n=21), and healthy controls (n=21) (47). The affected individuals, as a group, exhibited smaller frontal pole volumes in the orbitofrontal cortex, though these differences were less prominent in the CSBD group. An inverse relationship was observed between CSBD symptom severity and gray matter volumes in the anterior cingulate. According to DTI data, individuals with CSBD (36 heterosexual men) exhibited significantly reduced fractional anisotropy of the superior corona radiata tract, internal capsule tract, cerebellar tract, and white matter of the occipital gyrus than did the controls (31 matched healthy individuals) (48). These regions have also been identified in OCD and addiction, indicating similar abnormal patterns in the three conditions. However, whether CSBD is closer to addiction or OCD requires further investigation.

In conclusion, since the etiological research on CSBD conducted to date is limited, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Future studies, particularly those using larger samples and adopting longitudinal designs, are necessary.

6 The typology of CSBD

From a research perspective, diseases classified into the same category may provide a theoretical framework for similar etiological mechanisms, contributing to the advancement of disease research. From a practical viewpoint, appropriate classification might help in the assessment of comorbid diseases and facilitate the development of new or the application of existing and proven effective intervention measures for CSBD (for instance, if CSBD is classified as an addiction, then intervention measures for addiction might also treat CSBD) (49).

Patients with CSBD experience perceptions of uncontrollable behavior, extreme guilt related to sexual gratification, and distress related to adverse consequences or a lack of satisfaction from repetitive behaviors. This may encompass feelings of guilt and shame about masturbation, the use of online pornography, intrusive sexual thoughts, and engaging in sexual activities beyond established relational or societal boundaries. CSBD is commonly referred to in the media as “sex addiction” or “pornography addiction.” Some scientific publications attribute it to the sensitization of brain dopamine functions, similar to what is observed in substance addictions (50).

CSBD is regarded as an impulse control disorder in ICD-11. However, not all researchers agree on the rationale of this classification. Many scholars argue that CSBD can also be conceptualized as an addiction (15, 51), while others suggest that its manifestations might result from cultural differences or may even be non-pathological (52–54). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5-Text-Revision (DSM-5-TR) does not officially recognize CSBD as a diagnosis, employing terms such as ‘narrowly excluded’ to describe the omission of excessive sexual behavior disorders in the DSM-5 (1). Additionally, Sassover et al. argue that more attention should be paid to compulsive components in the manifestations of CSBD (13). However, symptomatic similarities between CSBD and other disorders in this category, such as OCD, body dysmorphic disorder, olfactory reference syndrome, hypochondriasis, and body-focused repetitive behavior disorder, are minimal. Among these disorders, avoiding negative states such as tension or fear is the focus, along with a lack of pleasant experiences or positive rewards. Given this, CSBD appears to be unsuitable for categorization under OCD. The current classification places CSBD alongside other impulse control disorders such as pyromania, kleptomania, and intermittent explosive disorders. However, the differences between the non-pathological and pathological states in these disorders are essential rather than frequency-based. Notably, CSB and all substance-related or behavior-related addictions, such as drinking, smoking, gambling, and gaming, are common behaviors in society.

The scientific community continues to gather knowledge regarding the nature of human sexual behavior. Three main models of sexual addiction have been proposed. They are based on impulse control disorders, OCD, and addictive disorders. The first model, proposed by Barth et al., is based on the compulsive-impulsive model, which is characterized by a lack of resistance to impulsive or harmful behaviors (55). This model interprets excessive sexual behavior as the inability to resist the impulse of sexual activities, which is in line with the DSM definition of impulse control disorder (56). Grant et al. investigated the prevalence of impulse control disorders among 204 psychiatric inpatients and found that 31% met the impulse control disorder criteria and 4.9% exhibited excessive sexual behavior (57). However, ICD-11 conceptualizes hypersexuality as an impulse control disorder but names it a CSBD, which puzzles many researchers and clinicians.

The second model introduces the term CSB, indicating a parallel relationship between OCD and sexual addiction, especially in terms of invasive and uncontrollable thoughts and behaviors. Sometimes, anxiety symptoms or psychological tension associated with the invasive thoughts that define OCD are observed in sexual addiction. Black et al. reported that among 36 patients with sexual addiction (28 males and 8 females), 42% reported repetitive and invasive sexual fantasies, and 67% reported poor self-esteem after sexual behavior (21). In another study, Raymond et al. reported that among 25 patients with sexual addiction (23 males and 2 females), 83% reported a decrease in mental tension after engaging in sexual behavior, and 70% described a sense of satisfaction after engaging in sexual behavior (22).

In the third model, hypersexuality is conceptualized as an addictive disorder (58). Craving starts as an early state, followed by repetitive behaviors that provide short-term pleasure or relief from mental distress. These behaviors become uncontrollable despite negative consequences. In a study by Potenza et al., 98% of patients reported withdrawal symptoms when sexual behavior was reduced, 94% reported difficulty or even an inability to control these behaviors, 92% reported spending excessive time on these behaviors, and 85% continued addictive behaviors despite negative physical or psychological consequences (59). The high prevalence of addictive comorbidities further supports this hypothesis: alcohol and psychotropic drugs (42%), gambling (5%), work (28%), shopping (26%), and eating disorders (38%) (2). These comorbidities may have pathophysiological bases similar to those of CSB.

The interaction between CSBD and neurochemical drugs suggests a correlation between CSBD and addiction. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist mainly used to control alcohol or opioid dependence, has been found to be effective in reducing the impulses and behaviors related to CSBD, which is consistent with its role in treating gambling disorder (60). A literature review by Nakum et al. reported that the prevalence of CSBD is higher in Parkinson’s disease patients receiving dopamine replacement therapy, especially dopamine agonists (61). Kraus et al. believe that the association between dopamine replacement therapy and CSBD can address this classification issue (15). However, this evidence is inconclusive, as it has been found that dopamine replacement therapy can also cause various impulse control problems that do not necessarily lead to addictive behaviors (62, 63).

Both identifying CSBD as an impulse control disorder or addictive behavior face obvious limitations. Brand et al. highlighted the risk of excessive pathologization of sexual behaviors and emphasized the importance of differentiating between frequent and addictive behavior patterns (51). Addiction, impulse control, and other clinical paradigms carry the risk of oversimplifying complex clinical phenomena. Applying treatment models designed for other disorders to CSBD without careful planning and outcome studies is risky and irresponsible. For instance, using treatment models designed for alcohol or drug use disorders, which focus on moderation, for CSB is particularly concerning.

The definition and classification of CSBD within mental disorder taxonomies may represent a compromise among different conceptualizations, including impulse control disorder, OCD, non-paraphilic hypersexual disorder, behavioral addiction, and sexual disorder. Given the heterogeneity in CSBD’s clinical presentation and the uncertainty surrounding the accuracy of epidemiological, psychological, and neurophysiological research on CSBD, debates about its etiology and diagnostic classification are likely to continue. Recent studies have effectively outlined the current diagnostic guidelines and controversies surrounding CSBD, suggesting that further research is required to better understand the etiology, clinical manifestations, comorbid factors, and appropriate classification of CSBD (13, 51, 64).

In conclusion, there is currently insufficient scientific evidence to determine the most appropriate classification and symptomatology of CSBD (13, 64). Whether problematic sexual behavior is described as CSB, sexual addiction, or sexual impulse disorder, thousands of psychiatrists and psychotherapists worldwide are engaged in the diagnosis and treatment of such disorders. The psychiatric community and the entire medical field should prioritize accumulating and summarizing evidence-based medical evidence for the treatment of CSBD.

7 The diagnosis of CSBD

The diagnosis of CSBD requires a thorough assessment, including a comprehensive examination of sexual history and current symptoms. It also involves the assessment of somatic and psychiatric medical histories to rule out other potential causes, such as neurological disorders or medication side effects. Moreover, examiners must conduct a psychiatric assessment to identify comorbid mental health conditions, including mood and anxiety disorders, SUDs, post-traumatic stress disorder, and personality disorders.

From a diagnostic perspective, CSBD should be regarded as a distinct and well-defined clinical disorder differentiated from other disorders (such as paraphilias and persistent genital arousal disorder). It must be acknowledged that the sense of loss of control and the perception of the consequences of uncontrolled sexual behavior represent a subjective experience influenced by factors such as personal values, beliefs, cultural norms, environmental expectations, and personality traits. To avoid overpathologizing individuals with high-frequency sexual behaviors that are personally or socially unacceptable, a limitation has been added to the diagnostic criteria of CSBD; that is, an individual’s distress should not be solely related to moral judgment or social disapproval. Cultural norms significantly influence perceptions of “loss of control” and “abnormal sexual behavior,” particularly in non-Western societies. For example, stigma around premarital sex, same-sex relationships, or masturbation in collectivist cultures may lead to misattribution of culturally disapproved behaviors as pathological (18, 65). A cross-cultural study involving 42 countries found that CSBD prevalence varied from 2.1% to 8.9%, partly due to cultural differences in defining “distress” and “impairment” (18). In some contexts, individuals may report “loss of control” based on cultural guilt rather than clinical dysfunction, risking overpathologization. It is important to distinguish between individuals with high sex drive and those with CSBD. If a high sex drive does not cause distress or if the distress is only mediated by negative social norms (e.g., cultural restrictions and religious thoughts regarding sex and sexual desire), then individuals with a high sex drive should not be pathologized (11, 66).

Various questionnaires and interviews can assess CSB and help determine whether an individual should be diagnosed with CSBD. A comprehensive evaluation should include both a self-rating tool (e.g., Hypersexual Behavior Inventory-19, HBI-19) and standardized external ratings (e.g., CD-11). For future research and clinical studies, we recommend using CSBD-19 and CSBD-7 based on ICD-11, as these tools have demonstrated their effectiveness in 42 countries (18). According to the DSM-5 criteria, the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI), consisting of seven items, was developed for screening CSBD (67). The first five items assess the intensity of sexual fantasies, sexual urges, and sexual behaviors, and the last two items assess personal distress or social impairment. It can be administered as an interview or a self-report scale. Compared with other existing diagnostic tools, the HDSI is noted for its strong psychometric properties (68). If there are concerns about the risk of sexual crimes related to CSB, standardized risk assessment tools (such as STABLE-2007 or the Violence Risk Scale-Sexual Offender Version) can be used to evaluate this aspect (69, 70). Conducting high-quality, internationally standardized assessments of CSBD will help identify patients with CSBDs across different populations and will ultimately facilitate research on evidence-based and culturally sensitive prevention and intervention strategies (1, 65).

8 The treatment of CSBD

The main treatment goals for patients with CSBD involve enhancing sexual self-control; reducing problematic sexual behaviors; minimizing adverse consequences, lowering the risk of harm to oneself or others; and alleviating distress and impairment in personal, family, social, educational, vocational, or other significant functional domains (71). Discrimination, stigmatization, and morally inconsistent therapeutic interventions should be strongly opposed and avoided. This includes pathologizing the sexual behaviors of sexually diverse individuals, unilaterally prohibiting certain sexual behaviors (e.g., watching pornography and masturbation), applying addiction models to control sexual behaviors, and attempting to impose the moral or religious values of medical professionals under the guise of evidence-based treatment.

According to the current state of knowledge, CSBD arises from the complex interactions between biology, psychology, and culture. Therefore, clinicians need to understand and skillfully manage the relevant factors that contribute to and perpetuate excessive sexual behaviors. Initially, treatment should focus on achieving stability, motivation, and self-management. Later, the treatment should address the functions of the aforementioned sexual behaviors, intimate relationships, and relationship issues.

Depending on differences in patients, available resources, and specific needs, various psychotherapy models and techniques may be used. Individual therapy, group therapy, and couple therapy are possible treatment modalities. In a recent systematic review, Antons et al. summarized 24 intervention studies on CSBD (72). Among the reviewed studies, the most widely used components of cognitive-behavioral therapy were as follows: psychoeducation; motivation and the impetus for change (e.g., motivational interviewing); goal determination; awareness of thoughts, emotions, and beliefs; training in self-regulation and impulse management; skill training: development of problem-solving skills, conflict management, time management, and coping strategies; mindfulness and meditation practices; relapse prevention and maintenance planning; along with acceptance and commitment therapy. Many of these techniques are only applicable during the initial stages of treatment.

An expert group from the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) recently proposed an algorithm for pharmacological treatment of CSBD (16). The extent of the intervention depends on the severity of the CSBD symptoms. The algorithm focuses on the evidence for the use of pharmacological treatments and classifies CSBD into three levels (mild, moderate, and severe) to guide the treatment plan. Typically, psychotherapy alone is used for first-level treatment and forms the basis for all subsequent treatments. In second-level treatment, the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone may be considered. In third-level treatment, a combination of these two drugs is recommended. While these drugs have shown some effectiveness in treating CSBD, they are “off-label” prescriptions, and no drug has been officially approved by regulatory agencies for the treatment of CSBD. In cases where CSBD coexists with paraphilic disorders, mainly considering the risk to others, drugs that reduce testosterone or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists may be used (73).

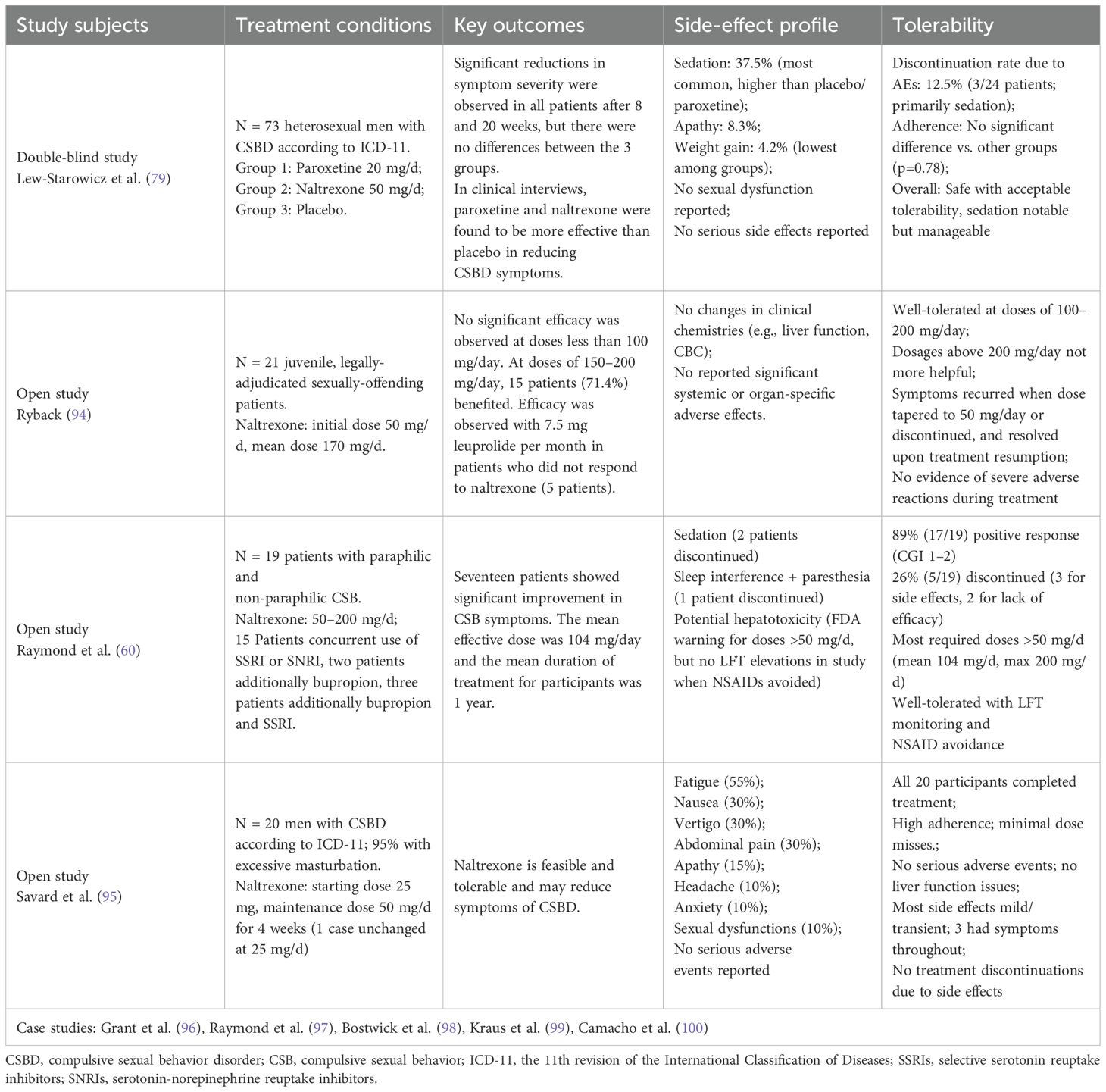

The summary of clinical research on the use of naltrexone is presented in Table 4. Naltrexone is a long-acting preferential opioid receptor antagonist that is widely used in the treatment of alcohol or opioid use disorders (74). Naltrexone may help reduce the potential for addiction by inhibiting endogenous opioids from triggering dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (75). The gradual desensitization achieved through naltrexone may be associated with reduced pleasurable effects, helping individuals with CSB reduce and regain control over their sexual behavior.

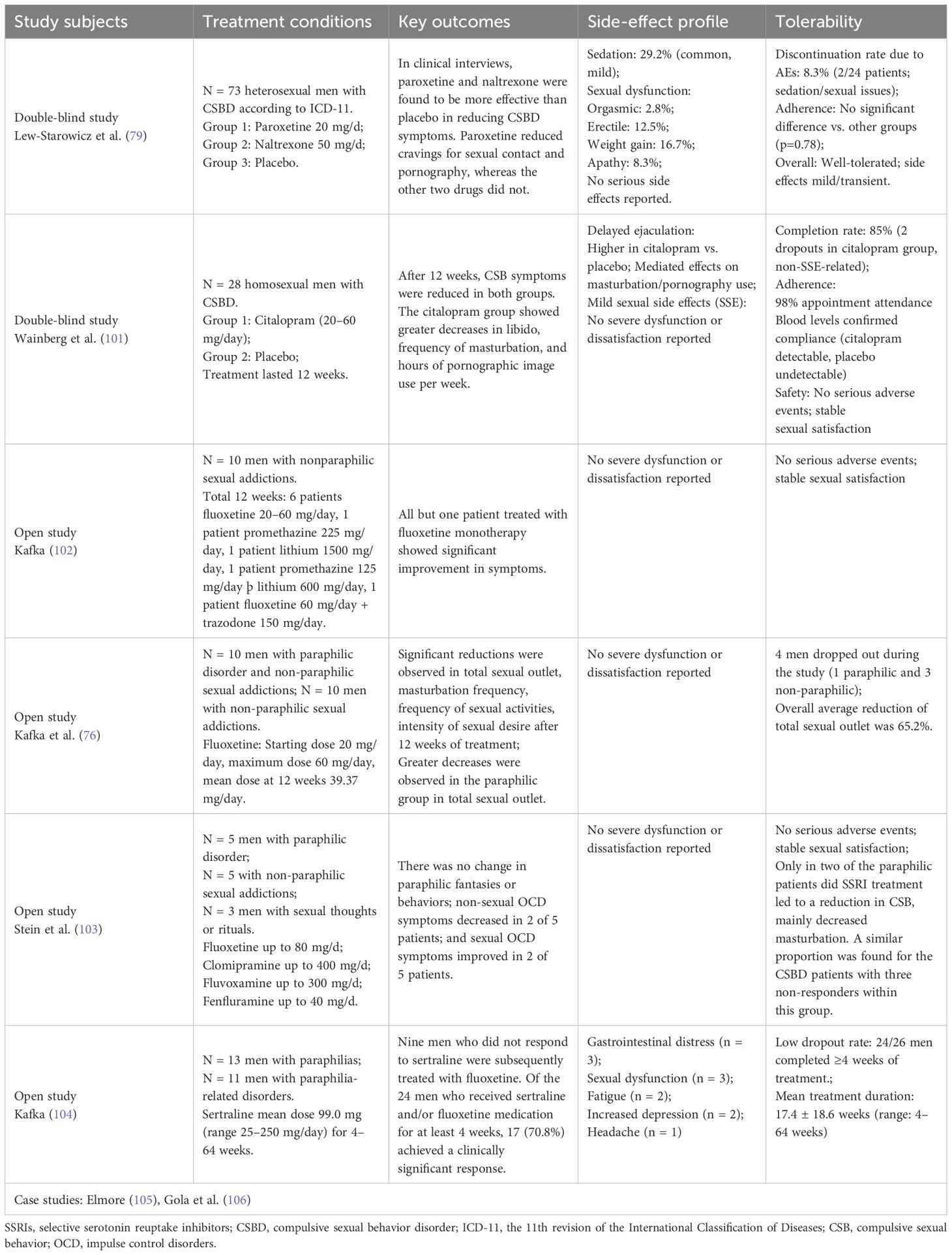

The summary of clinical research on the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is presented in Table 5. Many case reports and open studies have reported that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective in treating paraphilic disorders and non-paraphilic CSB, although SSRIs are not officially indicated for these conditions (76). One mechanistic hypothesis links the anti-obsessive effects of SSRIs to the hypothesis that CSB are related to OCD and impulse control disorders. SSRIs may decrease sexual desire, weaken erectile function, and delay ejaculation by increasing the binding of serotonin to the 5-HT-2 receptors in the brain and spinal cord (77). Sexual dysfunction associated with the use of SSRIs has been reported during the treatment of mood disorders and may persist during longer treatment courses (78).

In 2022, a placebo-controlled, double-blind RCT compared the tolerability and effectiveness of paroxetine and naltrexone in the treatment of CSBD (79). This study, involving 73 heterosexual men (average age 35.7) diagnosed with CSBD by ICD-11 criteria, compared naltrexone (50 mg daily), paroxetine (20 mg daily), and placebo over 20 weeks. The frequency of sexual urge episodes self-reported by patients at week 20 was reduced. In clinical interviews, paroxetine and naltrexone were found to be more effective than the placebo at reducing CSBD symptoms after 8 and 20 weeks, respectively.

Overall, there is currently very little high-level evidence regarding the pharmacological treatment of CSBD, and most studies are case reports. Notably, CSBD treatment plans have largely overlooked the specificity of sexual symptoms, moral incongruence, pornographic conflicts, and previous trauma. Additionally, they have neglected to address issues related to attachment, intimate relationships, and existing sexual function problems.

9 Limitations and future directions

9.1 Prospects for etiology research

There is currently insufficient scientific evidence to definitively categorize and symptomatically classify CSBD. The lack of etiological understanding has led to interventions based on flawed reasoning, which may result in erroneous, iatrogenic, and misleading outcomes. It is a misconception to believe that medications, such as naltrexone or SSRIs, can address all issues related to CSBD. In many cases, patients have experienced worsening conditions, intolerable side effects, or merely a placebo effect from the drugs (80). While viewing CSB as an addiction or impulse control disorder might seem like a step backward, future research should focus on exploring the underlying causes of CSBD, developing interventions that target these causes, and assigning research participants to optimal treatment conditions based on these etiological assessments.

9.2 Evaluation of treatment efficacy

Most reports on CSBD treatments are case reports or series, and studies on treatment efficacy often have methodological biases. Additionally, previous research often relied on self-reported sexual activity to evaluate treatment outcomes, focusing only on subjective improvements without standardized and reliable methods for measuring sexual behavior. More prospective studies are needed, using various measurement tools before and after interventions, including structured psychometric assessments, behavioral evaluations, and neuroimaging. National or international collaborative research, including large-scale CSBD cohort studies with long-term follow-up, is necessary to confirm credible data on the effectiveness of CSBD treatments.

9.3 Addressing polyaddiction

Polyaddiction is a critical aspect often overlooked in CSBD treatment. It is common for CSBD to co-occur with various other impulsive and addictive behaviors, such as substance use, problematic gaming, and gambling, as well as paraphilic disorders. This overlap is referred to as addiction interaction disorder in the sexual addiction community. For example, common addiction interaction disorder involves a combination of cocaine abuse, alcohol misuse, and excessive sexual behavior (81). Due to the shame associated with CSBD, patients often do not discuss it openly. In most substance abuse treatment centers, individuals seeking treatment for these behavioral combinations may have their sexual issues overlooked and receive treatment only for substance abuse and alcohol dependency. Unresolved sexual addiction can sometimes be a relapse trigger for substance and behavioral addictions. These issues underscore the need to assess CSBD within addiction treatment settings, especially where behavioral addiction is already the focus of treatment. Moreover, comprehensive education and interventions for patients with polyaddiction are crucial, with measures taken to reduce sexually transmitted infections, prevent human immunodeficiency virus, decrease alcohol/illicit drug intoxication and related adverse effects, and lower the risk of non-consensual sexual activities and sexual violence.

9.4 Addressing sexual dysfunction

Patients with CSBD often exhibit poor sexual performance. Individuals with CSBD display higher levels of sexual anxiety, sexual depression, external sexual control, and fear of sexual relationships than does the general population. Moreover, the severity of CSBD is inversely correlated with sexual self-esteem, internal sexual control, sexual awareness, sexual confidence, and sexual satisfaction (82). Individuals with sexual addiction may vigorously pursue their dysfunctional sexual behaviors, but they often face various forms of sexual dysfunction (83). Premature ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, impaired desire, sexual aversion, sexual anorexia, and anorgasmia are common among individuals with sexual addiction, particularly those in long-term partnerships or stable relationships. Consequently, integrated treatment is often necessary to foster healthy sexual relationships and satisfy sexual experiences during recovery. Sexual function therapy is typically initiated after achieving initial control of the behavioral disorder. Continuous monitoring and assessment of a patient’s sexual behavior are essential, with prescriptions tailored to address primary, secondary, and/or situational sexual dysfunctions.

9.5 Diagnosing and treating ADHD-CSBD comorbidity

ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, is often accompanied by early-onset emotional dysregulation, oppositional behaviors, or disorganization (84). The association between CSBD and ADHD reflects a complex interplay of shared and distinct mechanisms. Both disorders are characterized by deficits in self-regulation, particularly in impulse control and emotional regulation, which may underlie their comorbidity (85).

In clinical samples, ADHD symptoms are prevalent in individuals with CSBD, with historical studies reporting ADHD rates of 20–27% in men with CSB, often manifesting as the inattentive subtype (32, 86). According to a prior study, the co-occurrence rate of CSB in individuals with ADHD ranges between 5% and 12%, depending on the diagnostic threshold applied for ADHD (87). In a German online study involving 139 adults with ADHD (n = 89 women), approximately one-quarter (24.5%) reported CSB, with notable gender differences: 14.6% of women and 45.5% of men were affected. Despite these elevated co-occurrence rates, the study found no significant difference in the prevalence of CSB between adults with ADHD and those without (84).

A key diagnostic challenge is avoiding “overshadowing”, where impulsive sexual behaviors in ADHD might be misattributed to CSBD or vice versa. Both disorders involve difficulties with impulse control, but CSBD is characterized by recurrent, distressing sexual urges that persist despite negative consequences, whereas ADHD primarily involves sustained deficits in attention and hyperactivity (88). Clinicians must conduct thorough assessments to distinguish whether sexual compulsivity represents a primary disorder or secondary symptom of ADHD, particularly in cases where substance use or comorbid mood/anxiety disorders complicate presentation.

In terms of interventions, pharmacological approaches include psychostimulants, which may reduce both ADHD symptoms and sexual compulsivity by enhancing prefrontal control—though evidence is mixed, as seen in Kafka and Hennen’s positive findings versus Bijlenga et al.’s null results—thus necessitating individualized care (87, 89). Adjunctive medications like SSRIs, used for CSBD, help regulate mood and impulse control in comorbid cases but have limited impact on ADHD symptoms. Dual-diagnosis care is crucial, as untreated ADHD can hinder CSBD treatment adherence and vice versa, necessitating collaboration between sexologists and ADHD specialists (85). Such collaboration should involve integrating standardized assessments and longitudinal monitoring to tailor interventions effectively.

In summary, the complex interplay between CSBD and ADHD requires clinicians to avoid diagnostic oversights, recognize shared and distinct traits, and adopt integrated treatment strategies that combine pharmacological, behavioral, and collaborative approaches.

9.6 Focus on women and sexually diverse populations

The current understanding of CSBD is predominantly based on research on heterosexual male samples from Western countries. Little is known about the characteristics of CSBD among populations in non-Western cultures, as well as among women and sexually diverse groups. This indicates a methodological oversight where potential sex and cultural differences are frequently neglected. In fact, existing literature has reported differences in the prevalence and types of CSB when accounting for gender and sexual orientation. In a clinical study involving men (n = 64) and women (n = 16) with self-identified CSB, the most common problematic sexual behavior among men was pornography use (reported in 82% of cases), compared to 50% of women. Conversely, the most frequently cited behavior among women was engaging in sexual activity with consenting adults (88%), versus 36% of men (90).

A population-based study (n = 18,034) further indicated that non-heterosexual men—and to a lesser degree, non-heterosexual women (e.g., gay, bisexual individuals)—along with transgender and queer persons exhibited the highest prevalence of CSB indicators (e.g., masturbation frequency, number of sexual partners, pornography consumption frequency). This group also recorded the highest scores on the HBI-19 (91). Notably, however, these findings contrast with other research (92). For instance, Gleason et al. estimated that 7.9% of U.S. gay men exhibit clinically significant CSB—a prevalence not statistically higher than that observed in the general population (93).

These differences can affect risk factors, the severity of symptoms, the accuracy of diagnosis, and the effectiveness of treatment options for CSBD. More research is required on the prevalence, incidence, etiology, diagnostic criteria, comorbidities, sexual behavior patterns, and barriers to seeking help among women, impoverished and racial/ethnic minority groups, homosexuals, bisexuals, transgender individuals, people with physical and intellectual disabilities, and people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Bridging this research gap is crucial for improving clinical care, developing targeted interventions, and enhancing awareness of CSBD among the public, healthcare providers, and policymakers.

9.7 Enhancing training in sexual medicine

Given the sexual origins and consequences of CSBD, as well as the need for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of a range of sexual behaviors and disorders within a sociocultural context, expertise in clinical sexology or sexual medicine is required. Clinicians need to adopt a non-judgmental, positive attitude, understand sexual diversity, and identify the individual mechanisms that lead to uncontrolled sexual behavior, associated distress, and negative outcomes. The diagnostic process should also involve a detailed, thorough, and unbiased inquiry into partner-related issues and the patient’s sexual history. Treatment should focus not only on restricting sexual behaviors and preventing negative outcomes, but also on developing or restoring normal sexual and partner relationships. Therefore, clinicians need to knowledgeable in sexual medicine, including the assessment and management of various medical conditions and the interplay between various medications, sexual function, and behavior. Considering the limited focus on CSBD in current medical education, healthcare professionals treating CSBD may have limited knowledge of certain aspects of sexology. This highlights the need for interdisciplinary consultations and training programs.

10 Conclusions

CSBD is not a novel phenomenon or diagnostic entity but a problem described since the inception of the psychiatric-psychotherapeutic and sexual sciences. Despite being classified as an impulse control disorder, the precise etiological categorization of CSBD remains controversial. The diagnosis and treatment of patients with CSBD should integrate biological, psychological, and social factors with expertise in sexual medicine by employing a comprehensive and holistic therapeutic approach. This treatment aims not only to control abnormal sexual desires and behaviors but also to assist patients in achieving a healthy and satisfying sexual life and well-being.

Author contributions

LZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. WM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. RZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BS: Writing – review & editing. YC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82201777); and Basic and Clinical Collaborative Research Program of Anhui Medical University (grant numbers 2022.xkjT020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Grubbs JB, Hoagland KC, Lee BN, Grant JT, Davison P, Reid RC, et al. Sexual addiction 25 years on: A systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 82:101925. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925

2. Derbyshire KL and Grant JE. Compulsive sexual behavior: A review of the literature. J Behav Addict. (2015) 4:37–43. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.003

3. Giugliano JR. A psychoanalytic overview of excessive sexual behavior and addiction. Sexual Addict Compulsivity. (2003) 10:275–90. doi: 10.1080/713775415

4. Efrati Y and Gola M. Compulsive sexual behavior: A twelve-step therapeutic approach. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:445–53. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.26

5. Gold SN and Heffner CL. Sexual addiction: many conceptions, minimal data. Clin Psychol Rev. (1998) 18:367–81. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00051-2

6. Goodman A. Sexual addiction: designation and treatment. J sex marital Ther. (1992) 18:303–14. doi: 10.1080/00926239208412855

7. Goodman A. Diagnosis and treatment of sexual addiction. J sex marital Ther. (1993) 19:225–51. doi: 10.1080/00926239308404908

8. Carnes PJ, Green BA, Merlo LJ, Polles A, Carnes S, and Gold MS. Pathos: A brief screening application for assessing sexual addiction. J Addict Med. (2012) 6:29–34. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182251a28

9. Mick TM and Hollander E. Impulsive-compulsive sexual behavior. CNS spectrums. (2006) 11:944–55. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015133

10. Kafka MP. Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for Dsm-V. Arch sexual Behav. (2010) 39:377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7

11. Kraus SW, Krueger RB, Briken P, First MB, Stein DJ, Kaplan MS, et al. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the Icd-11. World Psychiatry. (2018) 17:109–10. doi: 10.1002/wps.20499

12. Fuss J, Lemay K, Stein DJ, Briken P, Jakob R, Reed GM, et al. Public stakeholders’ Comments on Icd-11 chapters related to mental and sexual health. World Psychiatry. (2019) 18:233–5. doi: 10.1002/wps.20635

13. Sassover E and Weinstein A. Should compulsive sexual behavior (Csb) be considered as a behavioral addiction? A debate paper presenting the opposing view. J Behav Addict. (2020) 11:166–79. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00055

14. Kowalewska E, Gola M, Kraus SW, and Lew-Starowicz M. Spotlight on compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A systematic review of research on women. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020) 16:2025–43. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S221540

15. Kraus SW, Voon V, and Potenza MN. Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addict (Abingdon England). (2016) 111:2097–106. doi: 10.1111/add.13297

16. Turner D, Briken P, Grubbs J, Malandain L, Mestre-Bach G, Potenza MN, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry guidelines on the assessment and pharmacological treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2022) 24:10–69. doi: 10.1080/19585969.2022.2134739

17. Briken P, Wiessner C, Štulhofer A, Klein V, Fuß J, Reed GM, et al. Who feels affected by “out of control” Sexual behavior? Prevalence and correlates of indicators for Icd-11 compulsive sexual behavior disorder in the German health and sexuality survey (Gesid). J Behav Addict. (2022) 11:900–11. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00060

18. Bőthe B, Koós M, Nagy L, Kraus SW, Demetrovics Z, Potenza MN, et al. Compulsive sexual behavior disorder in 42 countries: insights from the international sex survey and introduction of standardized assessment tools. J Behav Addict. (2023) 12:393–407. doi: 10.1556/2006.2023.00028

19. Schultz K, Hook JN, Davis DE, Penberthy JK, and Reid RC. Nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review of the literature. J sex marital Ther. (2014) 40:477–87. doi: 10.1080/0092623x.2013.772551

20. Wéry A, Vogelaere K, Challet-Bouju G, Poudat FX, Caillon J, Lever D, et al. Characteristics of self-identified sexual addicts in a behavioral addiction outpatient clinic. J Behav Addict. (2016) 5:623–30. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.071

21. Black DW, Kehrberg LL, Flumerfelt DL, and Schlosser SS. Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. Am J Psychiatry. (1997) 154:243–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.243

22. Raymond NC, Coleman E, and Miner MH. Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Compr Psychiatry. (2003) 44:370–80. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(03)00110-x

23. Kopeykina I, Kim HJ, Khatun T, Boland J, Haeri S, Cohen LJ, et al. Hypersexuality and couple relationships in bipolar disorder: A review. J Affect Disord. (2016) 195:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.035

24. Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Danielyan A, and Findling RL. Review and meta-analysis of the phenomenology and clinical characteristics of mania in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord. (2005) 7:483–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00261.x

25. Van Meter AR, Burke C, Youngstrom EA, Faedda GL, and Correll CU. The bipolar prodrome: meta-analysis of symptom prevalence prior to initial or recurrent mood episodes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2016) 55:543–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.017

26. Engel J, Veit M, Sinke C, Heitland I, Kneer J, Hillemacher T, et al. Same same but different: A clinical characterization of men with hypersexual disorder in the sex@Brain study. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:157. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020157

27. Stein DJ. Classifying hypersexual disorders: compulsive, impulsive, and addictive models. Psychiatr Clinics North America. (2008) 31:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.007

28. Bőthe B, Tóth-Király I, Potenza MN, Griffiths MD, Orosz G, and Demetrovics Z. Revisiting the role of impulsivity and compulsivity in problematic sexual behaviors. J sex Res. (2019) 56:166–79. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1480744

29. Fuss J, Briken P, Stein DJ, and Lochner C. Compulsive sexual behavior disorder in obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and associated comorbidity. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:242–8. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.23

30. Tang KTY, Kim HS, Hodgins DC, McGrath DS, and Tavares H. Gambling disorder and comorbid behavioral addictions: demographic, clinical, and personality correlates. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 284:112763. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112763

31. Rosenberg KP, Carnes P, and O’Connor S. Evaluation and treatment of sex addiction. J sex marital Ther. (2014) 40:77–91. doi: 10.1080/0092623x.2012.701268

32. Kafka MP and Hennen J. A Dsm-iv axis I comorbidity study of males (N = 120) with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Sex Abuse. (2002) 14:349–66. doi: 10.1177/107906320201400405

33. Lafortune D, Blais M, Miller G, Dion L, Lalonde F, and Dargis L. Psychological and interpersonal factors associated with sexualized drug use among men who have sex with men: A mixed-methods systematic review. Arch sexual Behav. (2021) 50:427–60. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01741-8

34. Reed GM, Drescher J, Krueger RB, Atalla E, Cochran SD, First MB, et al. Disorders related to sexuality and gender identity in the Icd-11: revising the Icd-10 classification based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:205–21. doi: 10.1002/wps.20354

35. Krueger RB, Reed GM, First MB, Marais A, Kismodi E, and Briken P. Proposals for paraphilic disorders in the international classification of diseases and related health problems, eleventh revision (Icd-11). Arch sexual Behav. (2017) 46:1529–45. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0944-2

36. Kafka MP and Hennen J. Hypersexual desire in males: are males with paraphilias different from males with paraphilia-related disorders? Sexual Abuse. (2003) 15:307–21. doi: 10.1177/107906320301500407

37. Dhuffar MK, Pontes HM, and Griffiths MD. The role of negative mood states and consequences of hypersexual behaviours in predicting hypersexuality among university students. J Behav Addict. (2015) 4:181–8. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.030

38. Koós M, Bőthe B, Orosz G, Potenza MN, Reid RC, and Demetrovics Z. The negative consequences of hypersexuality: revisiting the factor structure of the hypersexual behavior consequences scale and its correlates in a large, non-clinical sample. Addictive Behav Rep. (2021) 13:100321. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100321

39. Balfour ME, Yu L, and Coolen LM. Sexual behavior and sex-associated environmental cues activate the mesolimbic system in male rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2004) 29:718–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300350

40. Robinson TE and Berridge KC. Review. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B Biol Sci. (2008) 363:3137–46. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093

41. Voon V, Mole TB, Banca P, Porter L, Morris L, Mitchell S, et al. Neural correlates of sexual cue reactivity in individuals with and without compulsive sexual behaviours. PloS One. (2014) 9:e102419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102419

42. Gola M, Wordecha M, Sescousse G, Lew-Starowicz M, Kossowski B, Wypych M, et al. Can pornography be addictive? An Fmri study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2017) 42:2021–31. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.78

43. Klucken T, Wehrum-Osinsky S, Schweckendiek J, Kruse O, and Stark R. Altered appetitive conditioning and neural connectivity in subjects with compulsive sexual behavior. J sexual Med. (2016) 13:627–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.013

44. Seok JW and Sohn JH. Gray matter deficits and altered resting-state connectivity in the superior temporal Gyrus among individuals with problematic hypersexual behavior. Brain Res. (2018) 1684:30–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.035

45. Schmidt C, Morris LS, Kvamme TL, Hall P, Birchard T, and Voon V. Compulsive sexual behavior: prefrontal and limbic volume and interactions. Hum Brain Mapp. (2017) 38:1182–90. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23447

46. Miner MH, Raymond N, Mueller BA, Lloyd M, and Lim KO. Preliminary investigation of the impulsive and neuroanatomical characteristics of compulsive sexual behavior. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 174:146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.04.008

47. Draps M, Sescousse G, Potenza MN, Marchewka A, Duda A, Lew-Starowicz M, et al. Gray matter volume differences in impulse control and addictive disorders-an evidence from a sample of heterosexual males. J sexual Med. (2020) 17:1761–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.007

48. Draps M, Kowalczyk-Grębska N, Marchewka A, Shi F, and Gola M. White matter microstructural and compulsive sexual behaviors disorder - diffusion tensor imaging study. J Behav Addict. (2021) 10:55–64. doi: 10.1556/2006.2021.00002

49. Potenza MN. Commentary on: are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Defining and classifying non-substance or behavioral addictions. J Behav Addict. (2015) 4:139–41. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.023

50. Toates F. A motivation model of sex addiction - relevance to the controversy over the concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 142:104872. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104872

51. Brand M, Rumpf HJ, Demetrovics Z, MÜller A, Stark R, King DL, et al. Which conditions should be considered as disorders in the international classification of diseases (Icd-11) designation of “Other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”? J Behav Addict. (2020) 11:150–9. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00035

52. Borgogna NC and Aita SL. Another failure of the latent disease model? The case of compulsive sexual behavior disorder •. J Behav Addict. (2022) 11:615–9. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00069

53. Grubbs JB, Perry SL, Wilt JA, and Reid RC. Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: an integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch sexual Behav. (2019) 48:397–415. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1248-x

54. Jennings TL, Gleason N, and Kraus SW. Assessment of compulsive sexual behavior disorder among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer clients •. J Behav Addict. (2022) 11:216–21. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00028

55. Barth RJ and Kinder BN. The mislabeling of sexual impulsivity. J sex marital Ther. (1987) 13:15–23. doi: 10.1080/00926238708403875

56. Dell’Osso B, Altamura AC, Allen A, Marazziti D, and Hollander E. Epidemiologic and clinical updates on impulse control disorders: A critical review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2006) 256:464–75. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0668-0

57. Grant JE, Levine L, Kim D, and Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. (2005) 162:2184–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2184

58. Orford J. Hypersexuality: implications for a theory of dependence. Br J Addict to Alcohol other Drugs. (1978) 73:299–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1978.tb00157.x

59. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addict (Abingdon England). (2006) 101 Suppl 1:142–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01591.x

60. Raymond NC, Grant JE, and Coleman E. Augmentation with naltrexone to treat compulsive sexual behavior: A case series. Ann Clin Psychiatry. (2010) 22:56–62.

61. Nakum S and Cavanna AE. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of hypersexuality in patients with Parkinson’s disease following dopaminergic therapy: A systematic literature review. Parkinsonism related Disord. (2016) 25:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.02.017

62. Potenza MN, Voon V, and Weintraub D. Drug insight: impulse control disorders and dopamine therapies in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. (2007) 3:664–72. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0680

63. Seeman P. Parkinson’s disease treatment may cause impulse-control disorder via dopamine D3 receptors. Synapse (New York NY). (2015) 69:183–9. doi: 10.1002/syn.21805

64. Gola M, Lewczuk K, Potenza MN, Kingston DA, Grubbs JB, Stark R, et al. What should be included in the criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder? J Behav Addict. (2020) 11:160–5. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00090

65. Reed GM, First MB, Billieux J, Cloitre M, Briken P, Achab S, et al. Emerging experience with selected new categories in the icd-11: complex Ptsd, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry. (2022) 21:189–213. doi: 10.1002/wps.20960

66. Briken P. An integrated model to assess and treat compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Nat Rev Urol. (2020) 17:391–406. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0343-7

67. Reid RC, Garos S, and Fong T. Psychometric development of the hypersexual behavior consequences scale. J Behav Addict. (2012) 1:115–22. doi: 10.1556/jba.1.2012.001

68. Montgomery-Graham S. Conceptualization and assessment of hypersexual disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Med Rev. (2017) 5:146–62. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.11.001

69. Brankley AE, Babchishin KM, and Hanson RK. Stable-2007 demonstrates predictive and incremental validity in assessing risk-relevant propensities for sexual offending: A meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse. (2021) 33:34–62. doi: 10.1177/1079063219871572

70. Sowden JN and Olver ME. Use of the violence risk scale-sexual offender version and the stable 2007 to assess dynamic sexual violence risk in a sample of treated sexual offenders. psychol Assess. (2017) 29:293–303. doi: 10.1037/pas0000345

71. von Franqué F, Klein V, and Briken P. Which techniques are used in psychotherapeutic interventions for nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior? Sexual Med Rev. (2015) 3:3–10. doi: 10.1002/smrj.34

72. Antons S, Engel J, Briken P, Krüger THC, Brand M, and Stark R. Treatments and interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder with a focus on problematic pornography use: A preregistered systematic review. J Behav Addict. (2022) 11:643–66. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00061

73. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, Briken P, Goethals K, and Bradford JMW. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (Wfsbp) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 21:412–90. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1744723

74. Ray LA, Green R, Roche DJO, Magill M, and Bujarski S. Naltrexone effects on subjective responses to alcohol in the human laboratory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Biol. (2019) 24:1138–52. doi: 10.1111/adb.12747

75. Weerts EM, Kim YK, Wand GS, Dannals RF, Lee JS, Frost JJ, et al. Differences in delta- and mu-opioid receptor blockade measured by positron emission tomography in naltrexone-treated recently abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2008) 33:653–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301440

76. Kafka MP and Prentky R. Fluoxetine treatment of nonparaphilic sexual addictions and paraphilias in men. J Clin Psychiatry. (1992) 53:351–8.

77. Peleg LC, Rabinovitch D, Lavie Y, Rabbie DM, Horowitz I, Fruchter E, et al. Post-Ssri sexual dysfunction (Pssd): biological plausibility, symptoms, diagnosis, and presumed risk factors. Sexual Med Rev. (2022) 10:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.07.001

78. Reisman Y. Post-Ssri sexual dysfunction. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). (2020) 368:m754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m754

79. Lew-Starowicz M, Draps M, Kowalewska E, Obarska K, Kraus SW, and Gola M. Tolerability and efficacy of paroxetine and naltrexone for treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry. (2022) 21:468–9. doi: 10.1002/wps.21026

80. Borgogna NC, Owen T, Johnson D, and Kraus SW. No magic pill: A systematic review of the pharmacological treatments for compulsive sexual behavior disorder. J sex Res. (2024) 61:1328–41. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2023.2282619

81. Rawson RA, Washton A, Domier CP, and Reiber C. Drugs and sexual effects: role of drug type and gender. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2002) 22:103–8. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00215-x

82. Kowalewska E, Kraus SW, Lew-Starowicz M, Gustavsson K, and Gola M. Which dimensions of human sexuality are related to compulsive sexual behavior disorder (Csbd)? Study using a multidimensional sexuality questionnaire on a sample of polish males. J sexual Med. (2019) 16:1264–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.05.006

83. Glica A, Wizła M, Gola M, and Lewczuk K. Hypo- or hyperfunction? Differential relationships between compulsive sexual behavior disorder facets and sexual health. J sexual Med. (2023) 20:332–45. doi: 10.1093/jsxmed/qdac035

84. Hertz PG, Turner D, Barra S, Biedermann L, Retz-Junginger P, Schottle D, et al. Sexuality in adults with adhd: results of an online survey. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:868278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.868278

85. Soldati L, Bianchi-Demicheli F, Schockaert P, Kohl J, Bolmont M, Hasler R, et al. Association of Adhd and hypersexuality and paraphilias. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 295:113638. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113638

86. Reid RC, Carpenter BN, Gilliland R, and Karim R. Problems of self-concept in a patient sample of hypersexual men with attention-deficit disorder. J Addict Med. (2011) 5:134–40. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181e6ad32

87. Bijlenga D, Vroege JA, Stammen AJM, Breuk M, Boonstra AM, van der Rhee K, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and other sexual disorders in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to the general population. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. (2018) 10:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s12402-017-0237-6

88. Bothe B, Koos M, Toth-Kiraly I, Orosz G, and Demetrovics Z. Investigating the associations of adult adhd symptoms, hypersexuality, and problematic pornography use among men and women on a largescale, non-clinical sample. J Sex Med. (2019) 16:489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.312

89. Kafka MP and Hennen J. Psychostimulant augmentation during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in men with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders: A case series. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:664–70. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0912

90. Oberg KG, Hallberg J, Kaldo V, Dhejne C, and Arver S. Hypersexual disorder according to the hypersexual disorder screening inventory in help-seeking Swedish men and women with self-identified hypersexual behavior. Sex Med. (2017) 5:e229–e36. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2017.08.001

91. Bothe B, Bartok R, Toth-Kiraly I, Reid RC, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z, et al. Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Arch Sex Behav. (2018) 47:2265–76. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z

92. Blum AW, Lust K, Christenson G, and Grant JE. Links between sexuality, impulsivity, compulsivity, and addiction in a large sample of university students. CNS Spectr. (2020) 25:9–15. doi: 10.1017/S1092852918001591

93. Gleason N, Finotelli I Jr., Miner MH, Herbenick D, and Coleman E. Estimated prevalence and demographic correlates of compulsive sexual behavior among gay men in the United States. J Sex Med. (2021) 18:1545–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.07.003

94. Ryback RS. Naltrexone in the treatment of adolescent sexual offenders. J Clin Psychiatry. (2004) 65:982–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0715

95. Savard J, Öberg KG, Chatzittofis A, Dhejne C, Arver S, and Jokinen J. Naltrexone in compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A feasibility study of twenty men. J sexual Med. (2020) 17:1544–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.318

96. Grant JE and Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. (2002) 63:349–56. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0413

97. Raymond NC, Grant JE, Kim SW, and Coleman E. Treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour with naltrexone and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: two case studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2002) 17:201–5. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200207000-00008

98. Bostwick JM and Bucci JA. Internet sex addiction treated with naltrexone. Mayo Clinic Proc. (2008) 83:226–30. doi: 10.4065/83.2.226

99. Kraus SW, Meshberg-Cohen S, Martino S, Quinones LJ, and Potenza MN. Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. Am J Psychiatry. (2015) 172:1260–1. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060843

100. Camacho M, Moura AR, and Oliveira-Maia AJ. Compulsive sexual behaviors treated with naltrexone monotherapy. primary Care companion CNS Disord. (2018) 20. doi: 10.4088/PCC.17l02109

101. Wainberg ML, Muench F, Morgenstern J, Hollander E, Irwin TW, Parsons JT, et al. A double-blind study of citalopram versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive sexual behaviors in gay and bisexual men. J Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 67:1968–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1218

102. Kafka MP. Successful antidepressant treatment of nonparaphilic sexual addictions and paraphilias in men. J Clin Psychiatry. (1991) 52:60–5.

103. Stein DJ, Hollander E, Anthony DT, Schneier FR, Fallon BA, Liebowitz MR, et al. Serotonergic medications for sexual obsessions, sexual addictions, and paraphilias. J Clin Psychiatry. (1992) 53:267–71.

104. Kafka MP. Sertraline pharmacotherapy for paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders: an open trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 6:189–95. doi: 10.3109/10401239409149003

105. Elmore JL. Ssri reduction of nonparaphilic sexual addiction. CNS spectrums. (2000) 5:53–6. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900021921

Keywords: compulsive sexual behavior, sexual addiction, addictive behaviors, compulsivity, sexual function

Citation: Zhu L, Ma W, Zhang R, Wang C, Song B, Cao Y and Li G (2025) Evaluation and treatment of compulsive sexual behavior: current limitations and potential strategies. Front. Psychiatry 16:1621136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1621136

Received: 30 April 2025; Accepted: 13 June 2025;

Published: 03 July 2025.

Edited by:

Aviv M. Weinstein, Ariel University, IsraelReviewed by:

Lorenzo Zamboni, Integrated University Hospital Verona, ItalyLong Bai, Zhejiang University, China

Ewelina Kowalewska, Medical Centre for Postgraduate Education, Poland

Copyright © 2025 Zhu, Ma, Zhang, Wang, Song, Cao and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guanjian Li, YW55aXpob3VydW5mYUAxMjYuY29t; Yunxia Cao, Y2FveXVueGlhNkAxMjYuY29t; Bing Song, c29uZ2JpbmcwNjA5MDdAMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Lu Zhu

Lu Zhu Wenwen Ma1,3†

Wenwen Ma1,3† Chao Wang

Chao Wang Bing Song

Bing Song Yunxia Cao

Yunxia Cao Guanjian Li

Guanjian Li