- 1Visual Science and Optometry Center of Guangxi, The People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 2Scientific Research Department, The People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 3Guangxi Key Laboratory of Eye Health, The People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 4Guangxi Health Commission Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology and Related Systemic Diseases Artificial Intelligence Screening Technology, The People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 5Scientific Research Department, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 6Department of Ophthalmology, Nanxishan Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Guilin, Guangxi, China

- 7Department of School Health, Ningbo Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

Background: This study investigated the longitudinal dose–response relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization in school-aged adolescents and explored the mediating roles of psychological factors (loneliness, sadness, and nervousness).

Methods: A 2-year longitudinal design was used to collect self-reported data on sleep disorders, physical activity, screen time, smoking, alcohol use, and dieting behavior. Cyberbullying victimization was assessed during follow-up. Multivariate logistic regression analysis and restricted cubic splines (RCSs) were used to analyze the dose–response relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization. The mediation analysis explored indirect effects through loneliness, sadness, and nervousness.

Results: Among the 1,910 adolescents (mean age: 12.2 ± 0.47 years), the mean sleep disorder score was 3.32 ± 3.68 (range: 0–27.0), and 196 (10.3%) engaged in cyberbullying victimization during the follow-up period. Sleep disorders were significantly associated with an increased risk of cyberbullying victimization (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.06–1.14) after adjusting for confounders. Sensitivity analyses further validated the robustness of the results, which revealed that the risk of cyberbullying victimization increased approximately with increasing prevalence of sleep disorders. The RCS curve revealed that the risk of cyberbullying victimization increased approximately linearly with increasing prevalence of sleep disorders (P for overall<0.001, P for nonlinear=0.915). Compared with boys, girls with more sleep disorders presented a slightly greater risk of cyberbullying victimization (adjusted OR: 1.14 vs.1.08). Loneliness and nervousness partially mediated the association between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, accounting for 25.00% (indirect effect β = 0.003, P < 0.001) and 8.33% (indirect effect β = 0.001, P = 0.038) of the total effect, whereas sadness had no significant effect.

Conclusions: Sleep disorders independently predict cyberbullying victimization in adolescents, with stronger effects observed in girls. Loneliness and nervousness partially mediate this association. Targeted interventions to improve sleep, reduce loneliness and nervousness, and sex-specific strategies may mitigate cyberbullying victimization in school-aged adolescents.

1 Introduction

Sleep disorders among adolescents have emerged as a pressing global public health challenge, with meta-analyses estimating that approximately 34% (34%, 95% CI: 28–41%) of children and adolescents experience clinically significant sleep disturbances (1, 2). These deficits are associated with profound consequences, ranging from impaired neurocognitive development to heightened risks of mental health disorders (3–5). Concurrently, cyberbullying affects a substantial proportion of adolescents worldwide, with victimization rates reported ranging from 13.99% to 57.5%, and perpetration rates ranging from 6.0% to 46.3% (6–8). While previous studies suggest bidirectional links between sleep disruption and cyberbullying behaviors (9–11), the longitudinal mechanisms underlying this association remain poorly understood, particularly with respect to mediating psychological pathways and gender-specific vulnerabilities (9, 12).

Mounting evidence implicates sleep disorders as the precursors of cyberbullying (11). Neurobiological research has demonstrated that sleep deprivation disrupts prefrontal–amygdala connectivity—undermining emotion regulation and amplifying aggressive responses to social stressors (13–15). Conversely, cyberbullying victimization triggers hypervigilance and nocturnal rumination, thereby perpetuating sleep disturbances, with daily diary data illustrating sleep disturbance as a mediator between victimization and next-day negative affect (16, 17). However, three critical gaps limit current understanding (1): Most studies rely on cross-sectional designs, precluding causal inference (6, 10, 16) (2); the dose–response relationship between sleep disorder severity and cyberbullying risk remains unquantified; and (3) potential mediators—particularly distinct emotional states such as loneliness, sadness and nervousness—have not been systematically examined in longitudinal contexts (18, 19).

Psychological factors may mediate the link between sleep disorders and cyberbullying through various pathways. Loneliness, characterized by perceived social isolation, may exacerbate hostile attributions in peer interactions (20–22). Sadness—reflecting a dysphoric mood—can diminish motivation for prosocial conflict resolution (23), although older studies often conflated sadness with general emotional distress (24, 25). Nervousness (acute situational worry), although sometimes combined with anxiety, may operate differently, yet few recent studies have teased these aspects apart longitudinally. Our preliminary longitudinal data suggest that loneliness mediates 12.26% of the associations between sleep deficiency and fighting behavior (P < 0.05), whereas sadness and nervousness do not exhibit significant mediating effects (26). Notably, no longitudinal studies have compared these pathways while controlling for lifestyle confounders (e.g., screen time, substance use) that may covary with both sleep and cyberbullying (27).

This two-year prospective cohort study addresses these gaps through three objectives (1): to quantify the longitudinal dose–response relationship between baseline sleep disorders and incident cyberbullying victimization in Chinese adolescents (2); to test gender differences in this association, hypothesizing stronger effects in girls due to sex-specific emotional reactivity to sleep loss (28); and (3) to explore the influence of lifestyle factors (physical activity, screen time, smoking, alcohol use, and dieting behavior), as well as the mediating roles of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness. By employing restricted cubic splines (RCSs) for nonlinear exposure–outcome modelling and controlling for key behavioral confounders, this study advances the understanding of sleep disorder-cyberbullying mechanisms while informing targeted intervention strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

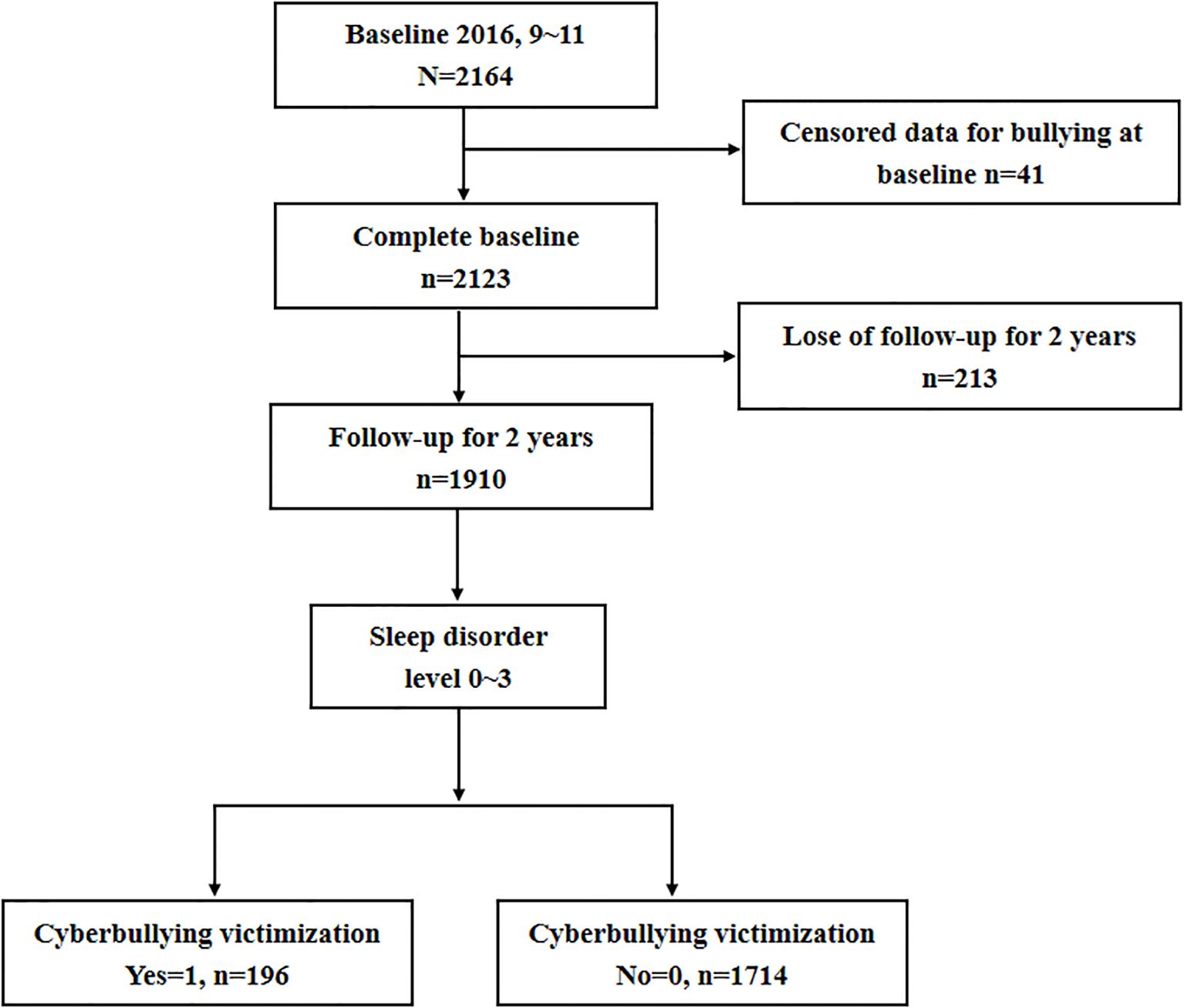

This school-based cohort study was conducted by the Ningbo Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Ningbo, China. The baseline survey was administered beginning in October 2016 and included seventh-grade students from 13 middle schools across 10 districts via cluster random sampling. Follow-up assessments were conducted in October 2017 and October 2018. The study enrolled healthy adolescents and excluded those with major illnesses or incomplete data. The study process is illustrated in Figure 1.

2.2 Measures

A standardized, self-report questionnaire adapted from the U.S. Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (29–31) was used to collect data on demographics, sleep duration and quality, physical activity, screen time, smoking, alcohol use, dieting behavior, and mental health. Trained investigators distributed and collected the questionnaires onsite, ensuring completeness.

2.2.1 Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders were evaluated at baseline via the sleep disorders subscale of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), developed by Buysee and colleagues (32), which is a self-administered questionnaire that measures sleep quality and disturbance over a 1-month period. There are nine items (5b to 5j) in this subscale dimension, ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (three or more times/week). The score of sleep disorders ranges from 0 to 27 points. The higher the score is, the greater the degree of sleep disorders. This sleep disorder evaluation method has been validated in a Chinese population (33). The Cronbach’s α for this subscale in the current sample was 0.717 (34).

2.2.2 Cyberbullying victimization

Cyberbullying victimization was assessed in October 2017 and October 2018 by the following question: “During the past 12 months, have you been electronically bullied (e.g., via email, chat rooms, instant messaging, websites, or texting)?” (1=yes, 0=no) (18, 35). The Cronbach’s α for this subscale in the current sample was 0.738.

2.2.3 Psychological factors

The psychological factors included self-reported loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (36). Psychological factors were assessed at Year 1 (2017). Loneliness was measured by the following question: “During the past 12 months, how often did you feel lonely?” with responses ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Sadness was measured by the following question: “During the past 12 months, have you felt very sad or hopeless for two weeks or longer and stopped your daily activities?” (1 = yes, 0 = no) (37). Nervousness was measured by the following question: “During the past 12 months, have you felt very nervous, worried, or anxious for a week or longer?” (1 = yes, 0 = no) (37).

2.2.4 Lifestyle factors and behavior

Lifestyle behaviors, including physical activity, screen time, smoking, alcohol use (38, 39), and dieting behavior, were evaluated at baseline. Physical activity was defined as engaging in moderate to vigorous exercise or muscle-strengthening activities at least once per week. Excessive screen time was defined as >2 hours per day of TV or internet use. Smoking and drinking were assessed on the basis of self-reported consumption at least once in the past month. Dietary behaviors included fruit and meat intake. Fruit intake was measured by the following question: “During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat fruits per day (excluding juice)?” The response options ranged from 1 (none) to 6 (5 or more times). Fruit intake was defined as engaging in at least once per day (1 = yes, 0 = no). A similar question was used to assess meat intake (39).

2.2.5 Covariates

Demographic variables, including sex, age, parental marital status, and parental education level, were collected at baseline as potential confounders (40).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all the variables. Continuous variables were assessed for normality via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables are reported as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), whereas nonnormally distributed variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages.

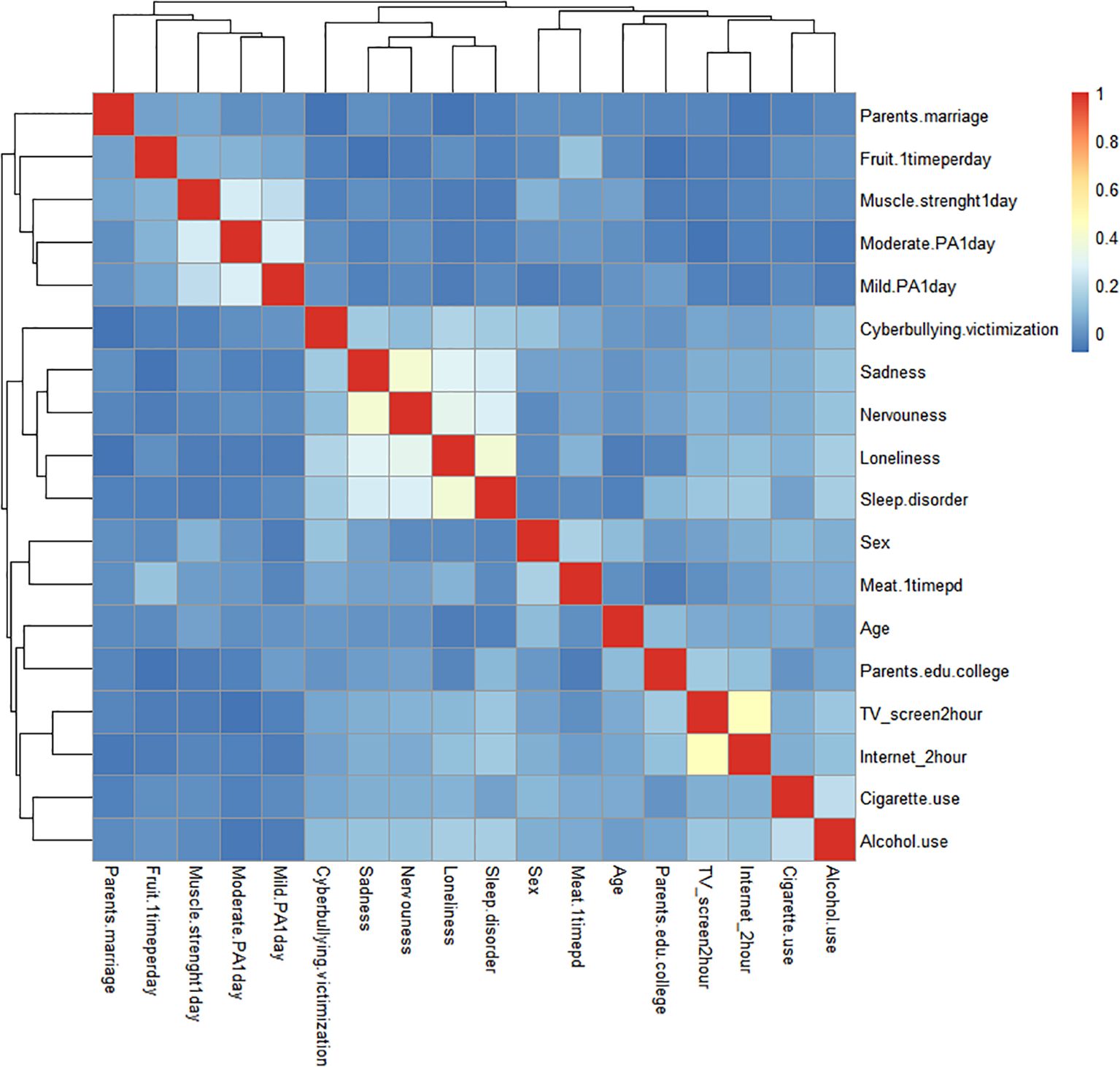

Between-group comparisons were performed via independent t tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Pearson correlation analysis or Spearman correlation analysis was used to explore the associations between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, lifestyle factors, and psychological factors, and heatmaps were drawn.

Multivariate logistic regression models were applied to examine the association between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, with the results reported as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To further explore the dose–response relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, we employed a restricted cubic spline (RCS) to further analyze their nonlinear relationship and plotted the RCS curve.

To assess the robustness of our results, we performed several additional sensitivity analyses. We classified sleep disorders into level 0 (sleep disorder score=0), level 1 (score=1–9), level 2 (score=10–18), and level 3 (score=19–27) groups on the basis of the sleep disorder score according to the PSQI instruction manual (32, 41) and calculated unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) via univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Mediation analysis was conducted to explore the indirect effects of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness on the relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization. All analyses were conducted via R software (version 4.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

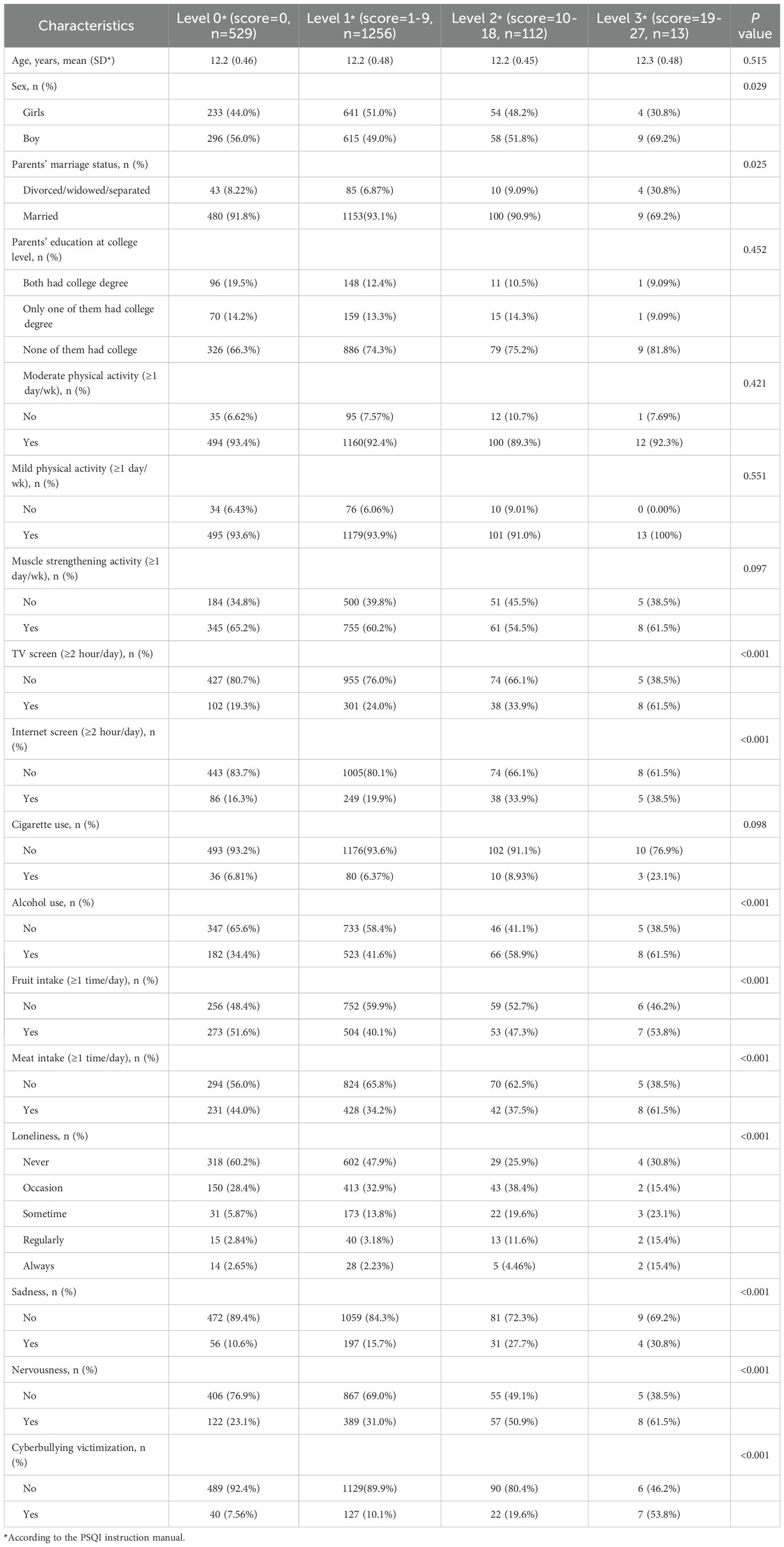

Among the 2164 students initially enrolled, 41 were excluded because of missing data, and 213 were lost to follow-up, resulting in a final sample of 1910 adolescents (Table 1). The mean age of the participants was 12.2 ± 0.47 years, and the mean sleep disorder score was 3.32 ± 3.68 (range: 0–27.0). Significant differences were observed among the sleep disorder groups in terms of sex, parental marriage status, TV screen time, internet screen time, alcohol use, fruit intake, and meat intake (all P < 0.05). Furthermore, adolescents with higher sleep disorder levels reported higher prevalences of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (all P < 0.05).

3.2 Incidence of cyberbullying victimization during follow-up

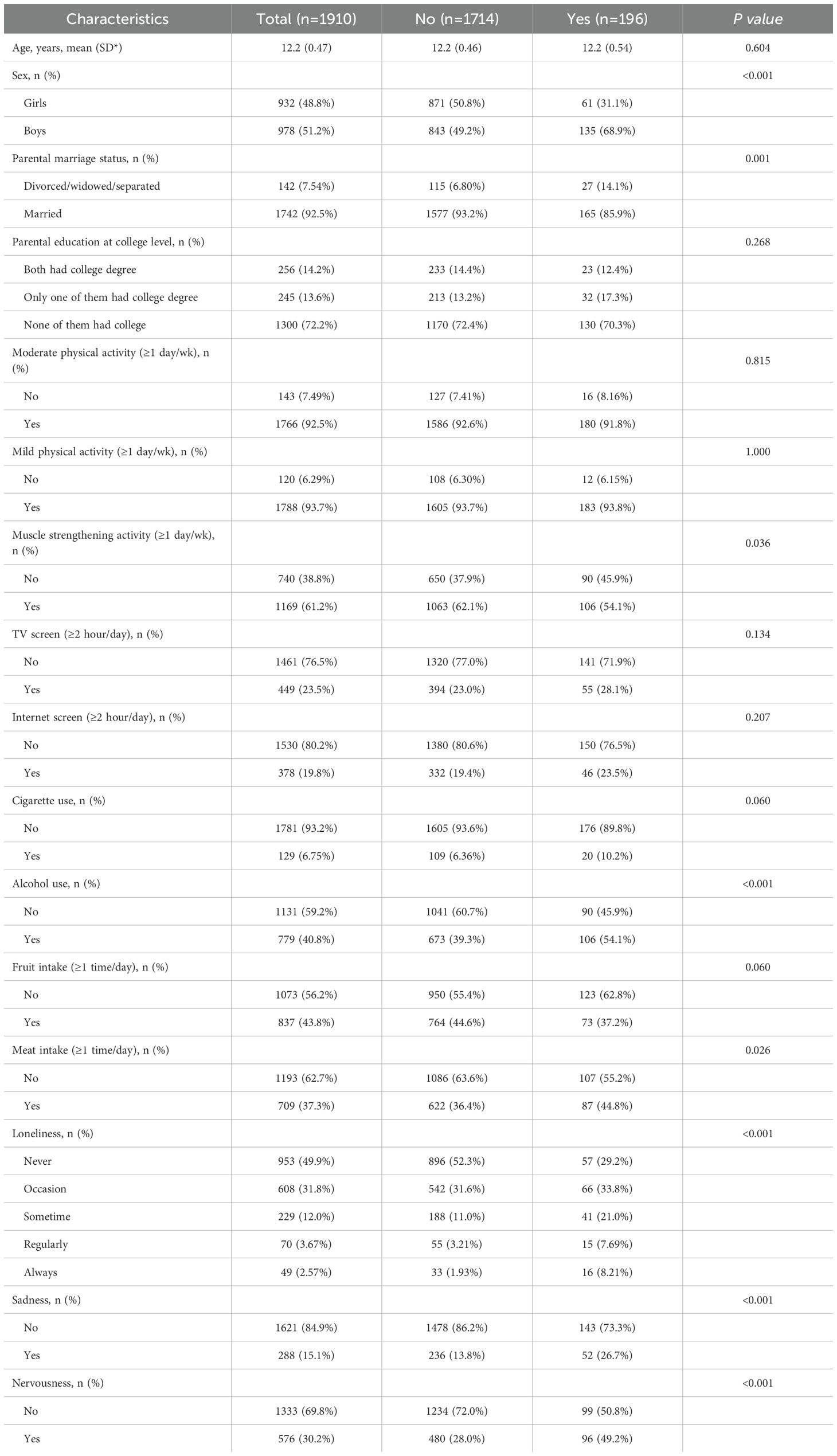

Over the two-year follow-up period, 196 adolescents (10.3%) engaged in cyberbullying victimization. The incidence of cyberbullying victimization was significantly associated with sex, parental marital status, muscle strengthening activity, alcohol use, meat intake, and adverse mental health outcomes, including loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (all P < 0.05, Table 2). Compared with girls (6.5%), boys were more likely to be involved in cyberbullying victimization (13.8%). Additionally, adolescents from households with divorced, widowed, or separated parents demonstrated an increased risk of cyberbullying victimization (19.0% vs. 9.5%). Compared with those not involved in cyberbullying victimization, adolescents involved in cyberbullying victimization presented significantly greater levels of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (all P < 0.05).

3.3 Correlations between cyberbullying victimization and covariates (sleep disorders, lifestyle and psychological factors)

Figure 2 shows the correlations of cyberbullying victimization with sleep disorders, lifestyle factors and psychological factors in school-aged adolescents. The heatmap correlation matrices revealed that cyberbullying victimization was significantly associated with sleep disorders, sex, parental marital status, TV screen time, internet screen time, alcohol use, fruit intake, meat intake, loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (all P < 0.05, Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Heatmap of correlations between cyberbullying victimization and covariates (sleep disorders, lifestyle and psychological factors).

3.4 Dose–response relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization

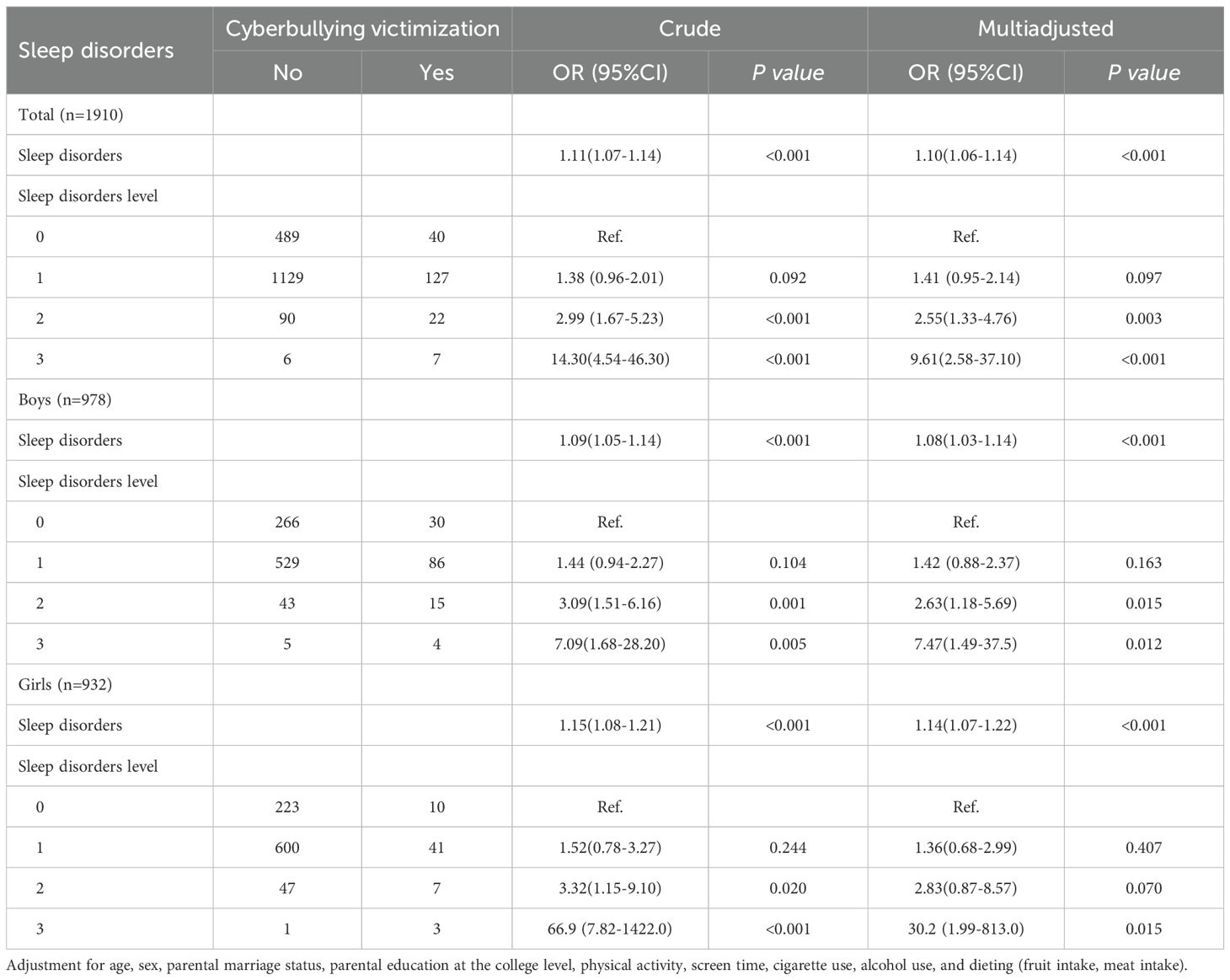

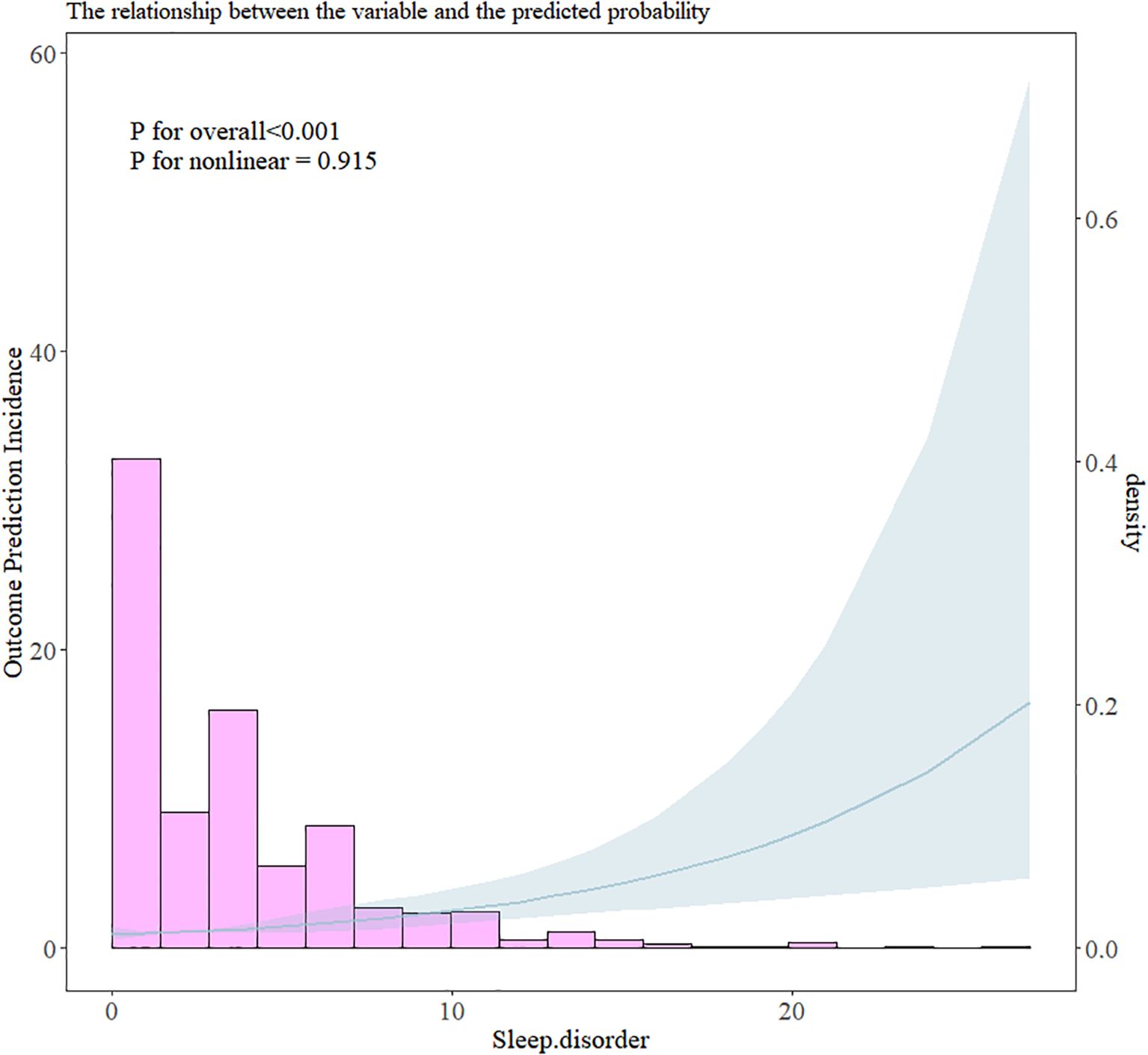

Multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that adolescents with sleep disorders at baseline had a significantly greater risk of cyberbullying victimization during follow-up (OR: 1.11, CI: 1.07–1.14; Table 3). After adjusting for age, sex, parental marital status, education level, physical activity, screen time, cigarette and alcohol use, and dietary habits, sleep disorders remained an independent predictor of cyberbullying victimization (OR: 1.10, CI: 1.06–1.14). Sensitivity analyses further validated the robustness of the results, with the risk ratio of cyberbullying victimization increasing approximately with increasing incidence of sleep disorders (Table 3). The RCS curve revealed that the risk ratio of cyberbullying victimization increased approximately linearly with increasing incidence of sleep disorders (P for overall<0.001, P for nonlinear=0.915; Figure 3).

Figure 3. RCS plot of the relationship between sleep disorders and the risk of cyberbullying victimization.

Gender-stratified analyses revealed that sleep disorders increased the risk of cyberbullying victimization among both boys (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.05–1.14) and girls (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.08–1.21). After adjusting for confounders, the association remained significant for both genders, although girls with greater sleep disorders presented a slightly greater risk of cyberbullying victimization (adjusted OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22) than boys did (adjusted OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.14).

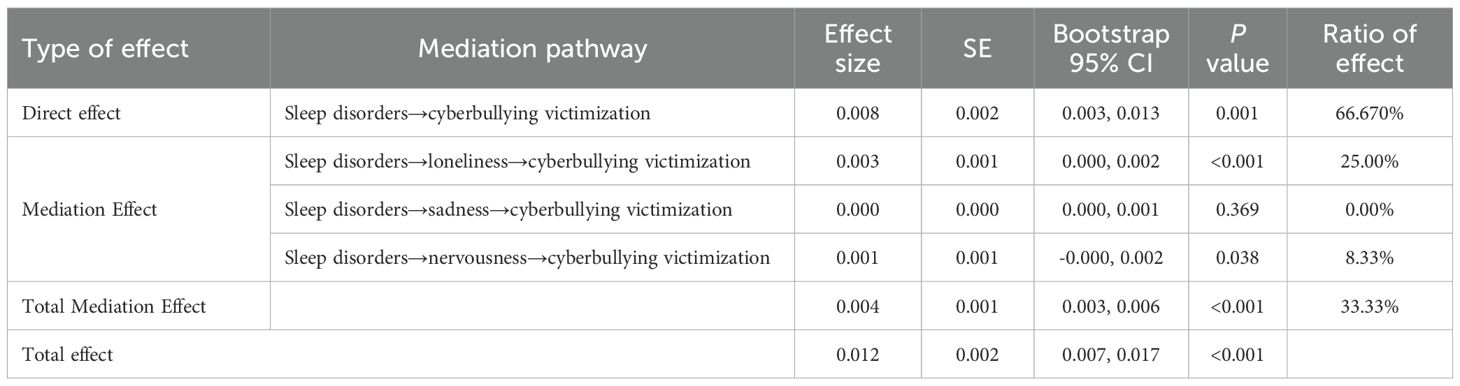

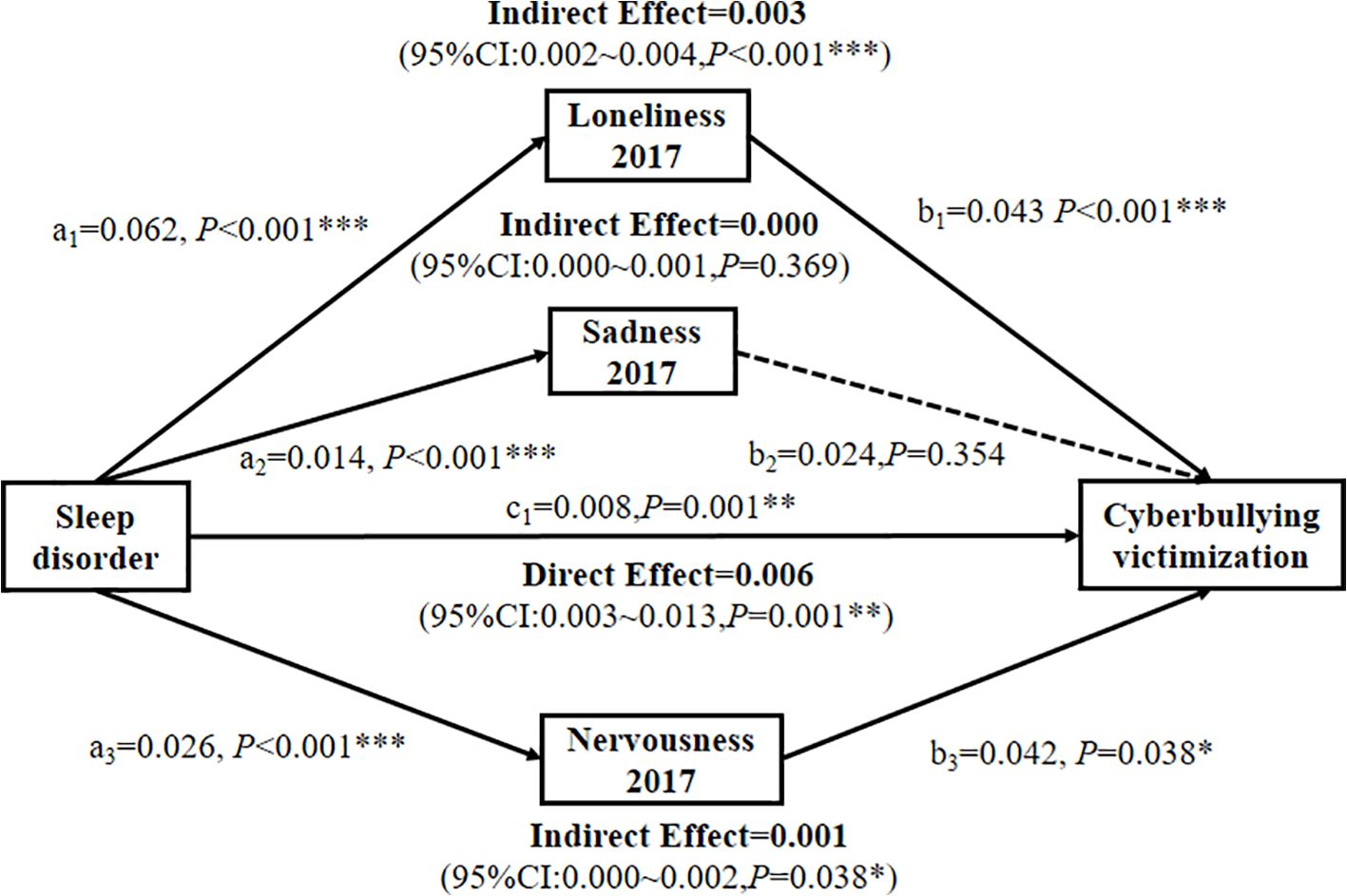

3.5 Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted to explore the roles of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness in the relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization (Table 4, Figure 4). Sleep disorders were positively correlated with cyberbullying victimization (β = 0.008, P = 0.001) and significantly predicted higher levels of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (all P < 0.05). Further analysis revealed that loneliness and nervousness were positively associated with cyberbullying victimization (β = 0.043 and 0.042, both P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Multiple parallel longitudinal associations between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization are mediated by loneliness, sadness, and nervousness at Year 1 (2017). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Loneliness partially mediated the relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, accounting for 25.00% of the total effect (indirect effect β = 0.003, P < 0.001; Table 4, Figure 4). Similarly, nervousness exhibited a partially mediated effect, contributing to 8.33% of the association (indirect effect β = 0.001, P = 0.038; Table 4, Figure 4). In contrast, sadness exhibited no significant mediating effects (P = 0.369), suggesting that the link between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization is driven primarily by increased loneliness and nervousness.

4 Discussion

4.1 Key findings

This two-year longitudinal study advances our understanding of the complex relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization in school-aged adolescents. After adjusting for lifestyle and sociodemographic confounders, sleep disorders independently predicted cyberbullying victimization (adjusted OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.06–1.14), with a stronger association observed in girls (adjusted OR: 1.14 vs. 1.08 for boys). Notably, loneliness and nervousness mediated 25.00% and 8.33% of this association, respectively, whereas sadness had no significant mediating effect. These findings highlight the critical interplay between sleep disturbances, emotional states, and cyberbullying behaviors, emphasizing the need for integrated interventions targeting sleep health and psychological well-being to mitigate the risk of cyberbullying victimization.

4.2 Mechanisms linking sleep disorders to cyberbullying victimization

Our results align with theoretical frameworks suggesting that sleep disorders impair emotional regulation and executive functioning, thereby increasing vulnerability to aggression and peer conflict (42–44). The observed dose–response relationship (P for overall < 0.001, P for nonlinear = 0.915) supports prior evidence that even subclinical sleep disturbances increase the risk of cyberbullying (11, 45, 46). For example, experimental studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation heightens amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli while reducing prefrontal cortex activity, fostering impulsivity and hostile social perceptions (47–49). Another cross-sectional survey by Chervin et al. (2003) demonstrated that adolescents with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) exhibit 2–3 times more bullying and other specific aggressive behaviors (50–52), which is consistent with our observed OR of 1.10. The lower risk magnitude in our cohort may stem from methodological differences: while prior studies focused on sleep disturbances (assessed via the Adolescent Sleep-Wake Scale) (53), we measured broader sleep deficits (e.g., insomnia, sleep apnea and narcolepsy) via the PSQI, a validated tool for adolescent populations (Cronbach’s α = 0.717 in our sample) (54). These neurobiological changes may explain why adolescents with sleep disorders are more prone to misinterpret social cues, escalating conflicts into cyberbullying perpetration or victimization (9, 10).

The gender-specific risk pattern—higher vulnerability in girls—contrasts with cross-sectional studies reporting stronger sleep-aggression associations in boys (55, 56) but aligns with longitudinal data suggesting that girls’ emotional reactivity to sleep loss is amplified during adolescence (57). This disparity may reflect sex differences in stress hormone responses (e.g., cortisol dysregulation) (58) or sociocultural factors, such as girls’ greater reliance on peer relationships for emotional support (59, 60). Further research should disentangle biological (e.g., pubertal hormones) and environmental (e.g., gender norms) contributors to these differences.

4.3 Moderating role of lifestyle factors and behaviors

The relationship between sleep disorders and cyberbullying may be moderated by lifestyle factors, with different lifestyle behavior variables presenting varying risk levels among adolescents. Interestingly, alcohol use is a lifestyle factor associated with both increased sleep disturbance and increased cyberbullying risk: adolescents who consume alcohol are more likely to experience sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization, reinforcing links between alcohol use, sleep disruption, and aggression (61). Surprisingly, reduced meat intake has been associated with increased sleep problems in recent dietary studies, yet in some contexts, it is correlated with lower engagement in aggressive behaviors, including cyberbullying—findings that suggest that dietary components may have complex, bidirectional associations with both sleep and peer conflict risk (62, 63). Moreover, while greater internet use time is consistently related to worsened sleep patterns (e.g., delayed sleep onset, lower sleep quality) (64), it does not always correlate with greater cyberbullying victimization in these same cohorts. A possible explanation is that these outcomes pertain to victimization rather than perpetration: high screen or internet time may increase exposure to online environments, but not all users become targets; moreover, lifestyle and dietary moderators may buffer or amplify risk differently for victims vs. perpetrators.

4.4 Mediating roles of loneliness and nervousness

The partial mediation by loneliness (25.00%) and nervousness (8.33%) highlights the importance of social-emotional pathways in the link between sleep disorders and cyberbullying. Sleep disturbances may intensify feelings of isolation by limiting opportunities for positive peer interactions, such as through daytime fatigue that hinders social engagement (44, 65). In contrast, nervousness may heighten negative appraisals of social situations, thereby increasing hostility (66, 67). These mechanisms align with the social information processing model, wherein sleep loss biases cognitive processing toward threat detection and retaliatory behaviors (68, 69).

The absence of mediation by sadness indicates that depressive symptoms may not directly influence cyberbullying victimization, contrasting with findings from cross-sectional studies (70, 71). This discrepancy could stem from differences in measurement (single-item vs. validated scales) or from the longitudinal design capturing the temporal precedence of mediators. Future studies should employ multidimensional mental health assessments to clarify these pathways. This distinction has practical implications: antibullying programs should prioritize social integration over worry reduction alone.

4.5 Implications for intervention

Our results advocate for multitiered interventions:

1. Primary prevention: School-based sleep hygiene programs (e.g., delayed school start times, reduced screen time before bed) could mitigate sleep disturbances and downstream cyberbullying risks (72).

2. Psychological Support: Cognitive–behavioral strategies targeting loneliness (e.g., social skills training) and sadness (e.g., emotion regulation techniques) may disrupt the mediation pathway (73).

3. Gender-Sensitive Approaches: Tailored interventions for girls—such as peer support groups addressing sleep-related emotional dysregulation—could address their heightened vulnerability.

4.6 Strength and limitations

The strengths of this study include its longitudinal design, adjustment for key confounders (e.g., substance use, screen time), and robust mediation analysis. However, several limitations must be acknowledged (1): Self-report bias and single-item assessment: Subjective measures and single-item assessments of sleep and cyberbullying may underreport sensitive behaviors. Objective tools (e.g., actigraphy, peer nominations) and repeat-item assessment can strengthen future work (74, 75) (2). Cultural specificity: The sample was drawn from a single Chinese region; replication in diverse populations is needed to assess generalizability (3). Temporal granularity: The 2-year follow-up may miss short-term fluctuations in mediators. Ecological momentary assessment can capture dynamic sleep–emotion–behavior interactions (40, 76).

4.7 Conclusion

Sleep disorders represent a modifiable risk factor for cyberbullying victimization in adolescents, with loneliness and nervousness serving as critical mediators. By integrating sleep promotion with psychosocial interventions targeting emotional well-being, policymakers and educators can disrupt the pathway from poor sleep to aggressive behaviors. Future research should test the efficacy of such strategies in randomized trials and explore the bidirectional relationships between sleep, emotions, and cyberbullying across developmental stages.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Upon reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide the dataset.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Ningbo CDC (No. 201703), and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants before participation. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

XX: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software. Z-LJ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. QL: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. S-JW: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. S-XL: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Q-HG: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by grants from the Science and Technology Project for Disease Control and Prevention of Zhejiang Province (No. 2025JK070), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (No. Guike AB23026047), Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program (No.2023020713), and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang (LTGY24H260007).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the study participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cai H, Chen P, Jin Y, Zhang Q, Cheung T, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents during covid-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiological surveys. Trans Psychiatry. (2024) 14:12. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02654-5

2. Liu J, Ji X, Pitt S, Wang G, Rovit E, Lipman T, et al. Childhood sleep: physical, cognitive, and behavioral consequences and implications. World J pediatrics: WJP. (2024) 20:122–32. doi: 10.1007/s12519-022-00647-w

3. Yang H, Luan L, Xu J, Xu X, Tang X, and Zhang X. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disturbance among adolescents in the eastern seaboard of China. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:1003. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18564-0

4. Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey AG, and Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:628–37. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30136-x

5. Zhang J, Paksarian D, Lamers F, Hickie IB, He J, and Merikangas KR. Sleep patterns and mental health correlates in us adolescents. J Pediatr. (2017) 182:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.007

6. Zhu C, Huang S, Evans R, and Zhang W. Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:634909. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.634909

7. Rao J, Wang H, Pang M, Yang J, Zhang J, Ye Y, et al. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimisation among junior and senior high school students in guangzhou, China. Injury prevention: J Int Soc Child Adolesc Injury Prev. (2019) 25:13–9. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042210

8. Marret MJ and Choo WY. Factors associated with online victimisation among Malaysian adolescents who use social networking sites: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e014959. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014959

9. Liu C, Liu Z, and Yuan G. Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, sleep quality, and emotional distress among adolescents: A two-wave cross-lagged analysis. J nervous Ment Dis. (2021) 209:123–7. doi: 10.1097/nmd.0000000000001267

10. Nagata JM, Yang JH, Singh G, Kiss O, Ganson KT, Testa A, et al. Cyberbullying and sleep disturbance among early adolescents in the U.S. Acad Pediatr. (2023) 23:1220–5. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.12.007

11. Barlett CP. Examining the longitudinal direct and indirect relationships between early sleep (Quality and duration) and later cyberbullying perpetration in emerging adults. Sleep Health. (2023) 9:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2023.08.022

12. Bhatnagar B. One in six school-aged children experiences cyberbullying, finds new who/europe study (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/27-03-2024-one-in-six-school-aged-children-experiences-cyberbullying--finds-new-who-europe-study (Accessed October 27, 2025).

13. Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, and Walker MP. The human emotional brain without sleep–a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr biology: CB. (2007) 17:R877–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007

14. Motomura Y, Kitamura S, Nakazaki K, Oba K, Katsunuma R, Terasawa Y, et al. Recovery from unrecognized sleep loss accumulated in daily life improved mood regulation via prefrontal suppression of amygdala activity. Front Neurol. (2017) 8:306. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00306

15. Chuah LY, Dolcos F, Chen AK, Zheng H, Parimal S, and Chee MW. Sleep deprivation and interference by emotional distracters. Sleep. (2010) 33:1305–13. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.10.1305

16. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Lien A, Hamilton HA, and Chaput JP. Cyberbullying involvement and short sleep duration among adolescents. Sleep Health. (2022) 8:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2021.11.009

17. Wang W, Xie M, Liu Z, Chen H, Wu X, and Lin D. Linking daily victimization to daily affect among adolescents: the mediating role of sleep quality and disturbance. J Youth adolescence. (2025) 54:354–67. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-02076-6

18. Sutter CC, Stickl Haugen J, Campbell LO, and Tinstman Jones JL. School and electronic bullying among adolescents: direct and indirect relationships with sadness, sleep, and suicide ideation. J adolescence. (2023) 95:82–96. doi: 10.1002/jad.12101

19. Kelly Y, Zilanawala A, Booker C, and Sacker A. Social media use and adolescent mental health: findings from the uk millennium cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. (2018) 6:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.005

20. Spithoven AWM, Bijttebier P, and Goossens L. It is all in their mind: A review on information processing bias in lonely individuals. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:97–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.003

21. Brinker V, Dewald-Kaufmann J, Padberg F, and Reinhard MA. Aggressive intentions after social exclusion and their association with loneliness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2023) 273:1023–8. doi: 10.1007/s00406-022-01503-8

22. Wu J, Zhang X, and Xiao Q. The longitudinal relationship between cyberbullying victimization and loneliness among chinese middle school students: the mediating effect of perceived social support and the moderating effect of sense of hope. Behav Sci (Basel Switzerland). (2024) 14:312. doi: 10.3390/bs14040312

23. Saija E, Pallini S, Baiocco R, Pistella J, and Ioverno S. Sharing, comforting, and helping in middle childhood: an explorative multimethod study. Child Indic Res. (2025) 18:401–21. doi: 10.1007/s12187-024-10198-3

24. Ferrando SJ, Lynch S, Ferrando N, Dornbush R, Shahar S, and Klepacz L. Anxiety and posttraumatic stress in post-acute sequelae of covid-19: prevalence, characteristics, comorbidity, and clinical correlates. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1160852. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1160852

25. BroChado S, Soares S, and Fraga S. A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma violence Abuse. (2017) 18:523–31. doi: 10.1177/1524838016641668

26. Wei W, Pan L, Li SX, Wang SJ, Gong QH, and Xiao X. Loneliness mediates the association between sleep deficiency and fighting in school-aged adolescents: A 2-year longitudinal study. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:29938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-13505-2

27. Cheng H, Hu W, Luo S, Feng X, Chen Z, Yu X, et al. Pathways linking loneliness and depressive symptoms among chinese adolescents: the mediating role of sleep disturbance. J Affect Disord. (2025) 370:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.11.006

28. Wright CJ, Milosavljevic S, and Pocivavsek A. The stress of losing sleep: sex-specific neurobiological outcomes. Neurobiol Stress. (2023) 24:100543. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2023.100543

29. Gong QH, Li SX, Li H, Cui J, and Xu GZ. Insufficient sleep duration and overweight/obesity among adolescents in a chinese population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050997

30. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2005. J school Health. (2006) 76:353–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00127.x

31. Gong Q, Li S, Wang S, Li H, and Han L. Sleep and suicidality in school-aged adolescents: A prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112918. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112918

32. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, and Kupfer DJ. The pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

33. Rong L. A meta-analysis of sleep quality studies with pittsburgh sleep quality index in young students over the past 15 years in China. Chin Ment Health J. (2010) 24:839–44. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2010.11.010

34. Xiao T, Pan M, Xiao X, and Liu Y. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: A chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol. (2024) 12:751. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-02237-z

35. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Chaput JP, Hamilton HA, and Colman I. Bullying involvement, psychological distress, and short sleep duration among adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53:1371–80. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1590-2

36. Liu T, Wang YH, Ng ZLY, Zhang W, Wong SMY, Wong GH, et al. Comparison of Networks of Loneliness, Depressive Symptoms, and Anxiety Symptoms in at-Risk Community-Dwelling Older Adults before and During Covid-19. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:14737. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-65533-z

37. Steen OD, Ori APS, Wardenaar KJ, and van Loo HM. Loneliness associates strongly with anxiety and depression during the covid pandemic, especially in men and younger adults. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:9517. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13049-9

38. Yang Y, Li SX, Zhang Y, Wang F, Jiang DJ, Wang SJ, et al. Chronotype is associated with eating behaviors, physical activity and overweight in school-aged children. Nutr J. (2023) 22:50. doi: 10.1186/s12937-023-00875-4

39. Gong QH, Li H, Zhang XH, Zhang T, Cui J, and Xu GZ. Associations between sleep duration and physical activity and dietary behaviors in chinese adolescents: results from the youth behavioral risk factor surveys of 2015. Sleep Med. (2017) 37:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.06.024

40. Shi X, Qiao X, and Zhu Y. Emotional Dysregulation as a Mediator Linking Sleep Disturbance with Aggressive Behaviors: Disentangling between- and within-Person Associations. Sleep Med. (2023) 108:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2023.06.003

41. Carpi M. The pittsburgh sleep quality index: A brief review. Occup Med (Oxford England). (2025) 75:14–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqae121

42. Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, and Tippett N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol psychiatry Allied disciplines. (2008) 49:376–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

43. Krizan Z and Herlache AD. Sleep disruption and aggression: implications for violence and its prevention. Psychol Violence. (2016) 6:542–52. doi: 10.1037/vio0000018

44. Wang W, Zhu Y, Yu H, Wu C, Li T, Ji C, et al. The impact of sleep quality on emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents: A chained mediation model involving daytime dysfunction, social exclusion, and self-control. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:1862. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19400-1

45. Ding H, Cao L, Xu B, Li Y, Xie J, Wang J, et al. Involvement in bullying and sleep disorders in chinese early adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1115561. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1115561

46. Peprah P, Oduro MS, Atta-Osei G, Addo IY, Morgan AK, and Gyasi RM. Problematic social media use mediates the effect of cyberbullying victimisation on psychosomatic complaints in adolescents. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:9773. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-59509-2

47. Chai Y, Gehrman P, Yu M, Mao T, Deng Y, Rao J, et al. Enhanced amygdala-cingulate connectivity associates with better mood in both healthy and depressive individuals after sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2023) 120:e2214505120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214505120

48. Hyndych A, El-Abassi R, and Mader EC Jr. The role of sleep and the effects of sleep loss on cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes. Cureus. (2025) 17:e84232. doi: 10.7759/cureus.84232

49. Zhang H, Xu L, Yi X, and Zhang X. Modulation mode of amygdala morphology and cognitive function under acute sleep deprivation in healthy male. Sleep Med. (2025) 127:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2025.01.008

50. Chervin RD, Dillon JE, Archbold KH, and Ruzicka DL. Conduct problems and symptoms of sleep disorders in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2003) 42:201–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00014

51. Kwon M, Seo YS, Nickerson AB, Dickerson SS, Park E, and Livingston JA. Sleep quality as a mediator of the relationship between cyber victimization and depression. J Nurs scholarship: an Off Publ Sigma Theta Tau Int Honor Soc Nurs. (2020) 52:416–25. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12569

52. Zeng R, Han D, Du W, Wen J, Zhang Y, Li Z, et al. The relationship between adolescent sleep duration and exposure to school bullying: the masking effect of depressive symptoms. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1417960. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1417960

53. Sun M, Ma Z, Xu B, Chen C, Chen QW, and Wang D. Prevalence of cyberbullying involvement and its association with clinical correlates among chinese college students. J Affect Disord. (2024) 367:374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.198

54. Scialpi A, Mignolli E, De Vito C, Berardi A, Tofani M, Valente D, et al. Italian validation of the pittsburgh sleep quality index (Psqi) in a population of healthy children: A cross sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9132. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159132

55. Fahlgren MK, Cheung JC, Ciesinski NK, McCloskey MS, and Coccaro EF. Gender differences in the relationship between anger and aggressive behavior. J interpersonal violence. (2022) 37:Np12661–np70. doi: 10.1177/0886260521991870

56. Van Veen MM, Lancel M, Beijer E, Remmelzwaal S, and Rutters F. The association of sleep quality and aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev. (2021) 59:101500. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101500

57. Jensen CD, Zaugg KK, Muncy NM, Allen WD, Blackburn R, Duraccio KM, et al. Neural mechanisms that promote food consumption following sleep loss and social stress: an fmri study in adolescent girls with overweight/obesity. Sleep. (2022) 45:zsab263. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab263

58. Zhou L, Kong J, Li X, and Ren Q. Sex differences in the effects of sleep disorders on cognitive dysfunction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2023) 146:105067. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105067

59. Schiff SJ and Lee SS. Peer correlates of conduct problems in girls. Aggressive Behav. (2023) 49:209–21. doi: 10.1002/ab.22063

60. Acheson A, Richards JB, and de Wit H. Effects of sleep deprivation on impulsive behaviors in men and women. Physiol Behav. (2007) 91:579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.020

61. Romualdo C, de Oliveira WA, Nucci LB, Rodríguez Fernández JE, da Silva LS, Freires EM, et al. Cyberbullying victimization predicts substance use and mental health problems in adolescents: data from a large-scale epidemiological investigation. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1499352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1499352

62. Zhong L, Han X, Li M, and Gao S. Modifiable dietary factors in adolescent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. (2024) 115:100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2024.02.009

63. López-Gil JF, Smith L, Victoria-Montesinos D, Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Tárraga-López PJ, and Mesas AE. Mediterranean dietary patterns related to sleep duration and sleep-related problems among adolescents: the ehdla study. Nutrients. (2023) 15:665. doi: 10.3390/nu15030665

64. American Psychological Association. Health advisory on social media use in adolescence. (2023). Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/social-media-internet/health-advisory-adolescent-social-media-use?utm (Accessed October 27, 2025).

65. Palmer CA, Powell SL, Deutchman DR, Tintzman C, Poppler A, and Oosterhoff B. Sleepy and secluded: sleep disturbances are associated with connectedness in early adolescent social networks. J Res adolescence: Off J Soc Res Adolescence. (2022) 32:756–68. doi: 10.1111/jora.12670

66. Albikawi ZF. Anxiety, depression, self-esteem, internet addiction and predictors of cyberbullying and cybervictimization among female nursing university students: A cross sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:4293. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054293

67. Aparisi D, Delgado B, and Bo RM. Explanatory model of cyberbullying, cybervictimization, aggressiveness, social anxiety, and adaptation to university: A structural equation analysis. J Comput Educ. (2025) 12:217–38. doi: 10.1007/s40692-023-00308-5

68. Tashjian SM and Galván A. Neural recruitment related to threat perception differs as a function of adolescent sleep. Dev Sci. (2020) 23:e12933. doi: 10.1111/desc.12933

69. Mi Y and Lei X. Sleep loss and lack of social interaction: A summary interview. Brain-Apparatus Communication: A J Bacomics. (2023) 2:2163593. doi: 10.1080/27706710.2022.2163593

70. Nagata JM, Shim J, Balasubramanian P, Leong AW, Smith-Russack Z, Shao IY, et al. Cyberbullying, mental health, and substance use experimentation among early adolescents: A prospective cohort study. Lancet regional Health Americas. (2025) 46:101002. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2025.101002

71. Hu Y, Bai Y, Pan Y, and Li S. Cyberbullying victimization and depression among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 305:114198. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114198

72. Duque FM, Santos D, Pinto D, da Silva Rêgo A, Vidinha T, Cardoso D, et al. Effectiveness of school-based sleep promotion programs for adolescents: A systematic review protocol. JBI evidence synthesis. (2023) 21:2422–8. doi: 10.11124/jbies-23-00053

73. Littlewood E, McMillan D, Chew Graham C, Bailey D, Gascoyne S, Sloane C, et al. Can we mitigate the psychological impacts of social isolation using behavioural activation? Long-term results of the uk basil urgent public health covid-19 pilot randomised controlled trial and living systematic review. Evidence-Based Ment Health. (2022) 25:e49–57. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2022-300530

74. Kahn M, Schnabel O, Gradisar M, Rozen GS, Slone M, Atzaba-Poria N, et al. Sleep, screen time and behaviour problems in preschool children: an actigraphy study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 30:1793–802. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01654-w

75. Kärnä A, Voeten M, Little TD, Poskiparta E, Alanen E, and Salmivalli C. Going to scale: A nonrandomized nationwide trial of the kiva antibullying program for grades 1-9. J consulting Clin Psychol. (2011) 79:796–805. doi: 10.1037/a0025740

Keywords: sleep disorders, cyberbullying victimization, adolescents, loneliness, nervousness, mediation effect

Citation: Xiao X, Jiang Z-L, Lei Q, Wang S-J, Li S-X and Gong Q-H (2025) Loneliness and nervousness mediated the longitudinal association between sleep disorders and cyberbullying victimization in school-aged adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 16:1640989. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1640989

Received: 04 June 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jason H. Huang, Baylor Scott and White Health, United StatesReviewed by:

Katharine Reynolds, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United StatesChuanwei Ma, Guangdong Medical University, China

Copyright © 2025 Xiao, Jiang, Lei, Wang, Li and Gong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin Xiao, eGlhb3hpMzg5MUAxNjMuY29t; Qing-Hai Gong, Z29uZ3FpbmdoYWlAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xin Xiao

Xin Xiao Zu-Ling Jiang5†

Zu-Ling Jiang5† Qing-Hai Gong

Qing-Hai Gong