Abstract

Psychiatric disorders like depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress Disorder have conventionally theorized on alterations in neurotransmitters, receptor pharmacodynamics, and neural connectivity. However, recent research points to a complementary framework involving the glymphatic system, a specialized glial lymphatic pathway that removes metabolic waste products, particularly during deep sleep, through the coordinated action of cerebrospinal fluid, interstitial fluid, and the aquaporin 4 channels of astrocytes. When the glymphatic network is compromised, neurotoxic proteins, such as beta-amyloid and tau, and inflammatory mediators can accumulate, potentially exacerbating insomnia, inflammation, and circadian disturbances. These same processes often occur in psychiatric disorders, fueling oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and cognitive decline. New neuroimaging methods, such as diffusion tensor imaging and the analysis Along the Perivascular Space, ALPS, index, allow clinicians and researchers to quantify perivascular flow deficits in vivo. Preliminary evidence suggests that enhancing glymphatic function by improving sleep architecture, supporting astrocyte health, or scheduling drug delivery based on circadian fluctuations may offer clinical benefits. Here, we present an overview of glymphatic biology, examine its relevance to psychiatric pathophysiology, highlight findings from emerging neuroimaging studies, and consider ways modulating glymphatic flow may improve psychiatric pharmacotherapy.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background and rationale

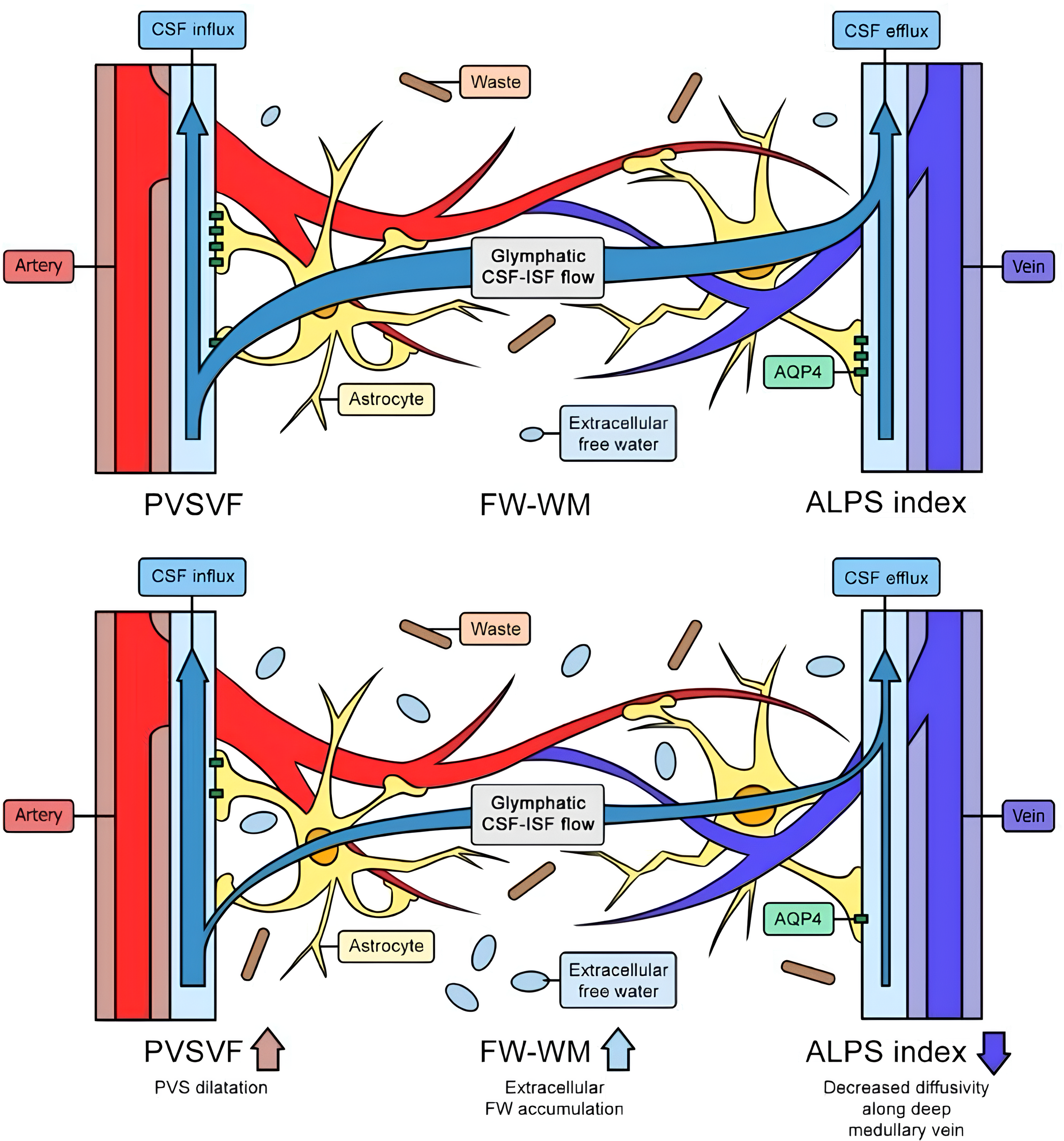

Traditional neuron−centric models, focused on neurotransmitters, receptor signaling, and connectivity, do not fully capture the complexity of major psychiatric disorders (1–3). Currently, the attention has shifted to processes that are geared by brain systems that handle sleep patterns, inflammation, and metabolism in understanding and improving these complex conditions of psychiatric disorders (4–8). One of the systems that handles these processes of maintaining brain homeostasis is the glymphatic system. The key mechanism of this system is that it uses the organized network of perivascular pathways extending from the vasculature to push and circulate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the subarachnoid spaces to the brain parenchyma via specialized structures called aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels at the end feet of the astrocytic cells (9–11) Figure 1.

Figure 1

A new integrated and pragmatic theoretical model is essential for clinical application, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment, by correlating noninvasive neuroimaging data with alterations in the neuro-glio-vascular microenvironment and the broader macroenvironment. This framework helps explain the clinical symptoms observed in patients, murine models, and other experimental models with degenerative glymphatic changes.

1.1.1 CSF production and entry into brain parenchyma

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced predominantly by the choroid plexus and flows from the ventricular system to the subarachnoid space (12, 13). From there, CSF enters the brain parenchyma mainly along peri−arterial, Virchow–Robin, spaces that accompany penetrating arteries, where it exchanges with interstitial fluid (ISF) through aquaporin−4 (AQP4)−rich astrocytic endfeet (14–16). In addition, local transependymal/subependymal exchange can contribute under specific physiological or pathological conditions (17). Outflow proceeds toward perivenous spaces, dural venous sinuses, and meningeal lymphatic vessels, ultimately draining to head and cervical, especially deep cervical, lymph nodes (18–22).

1.1.2 Drivers of perivascular exchange

Perivascular CSF–ISF exchange is driven by arterial pulsatility, slow vasomotion generated by vascular smooth muscle cells, like the intramural periarterial drainage (IPAD) mechanism, and respiratory oscillations (14, 23, 24). Within the neuro−glio−vascular unit, AQP4 polarization at astrocytic endfeet lowers hydraulic resistance and supports efficient clearance (15, 25).

1.1.3 Sleep in contex

Deep non−REM sleep transiently expands the extracellular space and enhances convective flow, wherea fragmented or insufficient sleep can diminish clearance capacity (16, 26–28). However, sleep outstand as one of several modulators alongside vascular, respiratory, and astroglial factors, rather than the sole driver of glymphatic clearance.

1.1.4 Emerging in vivo biomarkers

Diffusion MRI methods, particularly Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Analysis Along the Perivascular Space (DTI−ALPS), together with BOLD−CSF and arterial spin labeling (ASL), provide noninvasive readouts of perivascular transport and related hemodynamics (17, 29, 30). Early studies in psychiatric cohorts associate altered glymphatic metrics with cognitive an affective symptom burden (31–35).

1.1.5 Scope and article structure

We therefore evaluate glymphatic biology with emphasis on CSF production/entry routes and the main flow drivers, synthesize neuroimaging evidence across psychiatric conditions, and outline a glymphatic−oriented therapeutic perspective integrating sleep architecture, astrocyte/AQP4 health, vascular control, and dosing−time alignment. After this Introduction, we first present a biological overview (Section 1.2) and clinical relevance (Section 1.3); we then describe the Methods, followed by neuroimaging characteristics, pharmacotherapy implications, and a concise one−paragraph conclusion.

1.2 Overview of the glymphatic system

1.2.1 CSF production, routes of entry, and outflow

The glymphatic pathway links CSF dynamics to ISF exchange: CSF is produced predominantly by the choroid plexus, travels through the ventricles to the subarachnoid space, and then enters the parenchyma primarily along Virchow–Robin spaces where it mixes with ISF via AQP4−enriched astrocytic endfeet (12–16, 36). In addition to this perivascular entry, transependymal/subependymal exchange can contribute under specific physiological or pathological conditions (17). Clearance proceeds along perivenous routes toward dural venous sinuses and meningeal lymphatic vessels, with downstream drainage to head and cervical, especially deep cervical, lymph nodes (18–20, 22, 37).

1.2.2 Forces that drive glymphatic transport

Convective CSF–ISF exchange is propelled by a combination of arterial pulsatility, slow vasomotion generated by vascular smooth muscle cells, the IPAD mechanism, and respiratory oscillations (14, 23, 24, 38). Noradrenergic tone modulates the microarchitecture of non−REM sleep and the underlying vasomotion that supports bulk flow, providing a physiological link between arousal state and clearance efficiency (39). Within this framework, meningeal and dural lymphatic conduits complete the loop by returning solutes to extracranial lymph nodes (18, 20, 22, 40).

1.2.3 Astrocytes, AQP4 polarization, and neuroimmune crosstalk

Astrocytic endfeet organize low−resistance perivascular conduits through AQP4 polarization (41); stress, inflammation, and vascular insults can mislocalize AQP4, heighten astrocyte reactivity, and amplify microglial signaling, thereby reducing perivascular exchange and perturbing glutamate and metabolic homeostasis (10, 15, 25, 42–45). These glial changes, by raising hydraulic resistance and altering neurovascular coupling, are expected to dampen glymphatic throughput and set the stage for neuroinflammatory feedback (1, 24, 46, 47).

1.2.3.1 Sleep as one modulator among several

Deep non−REM sleep transiently expands the extracellular space and enhances convective flow, whereas sleep fragmentation or insufficiency can blunt this effect (16, 26). Despite its importance, sleep emerges as one of many factors influencing glymphatic function, along with IPAD vasomotricity, arterial pulsatility, respiration, and astroglial polarity.

1.2.3.2 Posture, respiration, and practical considerations

Experimental work in rodents indicates that lateral recumbency favors tracer clearance compared with supine or prone postures, likely by reducing venous outflow resistance; most reports specify “lateral” without a consistent right/left preference, and the principal comparison is lateral versus non−lateral positions (14, 16). Respiratory oscillations additionally entrain CSF movement and interact with cardiac pulsatility to shape perivascular transport (24).

1.2.3.3 Summary and link to psychiatric relevance

In sum, the glymphatic system is a paravascular–lymphatic interface governed by CSF production and routing, vascular and respiratory forcing, and astrocyte/AQP4 biology, with efflux through meningeal lymphatics to deep cervical nodes (13, 14, 18, 20, 22). Because sleep disruption, inflammation, and vascular stiffening converge on these same mechanisms, they represent plausible levers through which psychiatric conditions may alter clearance and, reciprocally, be exacerbated by impaired removal of neurotoxic and inflammatory mediators (15, 24).

1.3 Relevance for psychiatric disorders

Glymphatic dysfunction is clinically relevant to psychiatry because impaired CSF–ISF exchange mislocalization of AQP4, and altered vascular/respiratory forcing can promote retention of neurotoxic proteins and inflammatory mediators, disrupt neuro−glio−vascular coupling, and degrade synaptic and cognitive integrity, mechanisms that map onto symptom clusters observed across mood, psychotic, stress−related, substance−use, and neurodevelopmental disorders (4, 9, 14–16, 24, 48–50).

1.3.1 Pathways linking glymphatic impairment to psychiatric phenotypes

Direct, clearance−centric, pathway. When perivascular flow slows, removal of β−amyloid, tau, reactive oxygen species, and cytokines is diminished, fostering neuroinflammation and synaptopathy that manifest as anergia, anhedonia, impaired executive control, and negative symptoms (14, 16, 24, 48, 51). In parallel, elevated interstitial metabolites perturb astrocytic glutamate handling and neurovascular coupling, compounding cognitive−affective dysfunction (15, 52).

Sleep–circadian−mediated pathway. Insomnia, hyperarousal, and circadian misalignment curtail deep non−REM−linked expansion of the extracellular space and lower convective flux; over time, this amplifies inflammatory signaling and symptom persistence (5, 6, 16, 26). Noradrenergic dynamics during sleep modulate slow vasomotion, a driver of glymphatic flow, thus arousal level and clearance efficiency are directly connected (39, 53).

Vascular–metabolic–immune pathway. Arterial stiffening, metabolic dysregulation, and systemic inflammation degrade pulsatility and IPAD vasomotion, mislocalize AQP4, and raise hydraulic resistance, thereby compounding clearance failure (4, 15, 23, 25, 40, 54). These changes also interact with endothelial dysfunction and microglial activation to sustain low−grade neuroinflammation relevant to chronic mood and psychotic illness (24, 55–57).

1.3.2 Neuroimaging evidence and biomarkers of relevance

Diffusion MRI approaches quantify paravascular transport in vivo (17, 58). The DTI−ALPS index measures water diffusion along perivenular spaces and serves as a proxy of glymphatic transport efficiency; moreover, related signals from BOLD−CSF and ASL could provide complementary information on CSF pulsatility and cerebral perfusion (17, 24, 29, 30, 59). Across psychiatric cohorts, lower ALPS values and abnormal BOLD−CSF coupling associate with cognitive deficits, fatigue, and disease duration, supporting a clearance component beyond neurotransmitter models (31–34). Importantly, ALPS reductions have been observed even with minimal antipsychotic exposure, suggesting that glymphatic alterations are not solely medication effects (60, 61).

1.3.3 Structural and inflammatory correlates strengthen biological plausibility

Choroid plexus enlargement and systemic inflammatory/oxidative markers have been linked to reduced glymphatic indices in depression, indicating a nexus between CSF production interfaces, immune trafficking, and paravascular clearance (62). Moreover, coupling ALPS with regional cerebral blood flow improves classification in stimulant−use cohorts, consistent with intertwined vascular and perivascular mechanisms (63).

1.3.4 Disorder−specific summaries

Major depressive disorder (MDD). MDD frequently features sleep fragmentation, elevated inflammatory burden, and cognitive inefficiency. Imaging studies report lower ALPS indices correlating with fatigue and cognitive symptoms, alongside inflammatory signatures and choroid plexus changes that implicate impaired perivascular transport (32, 34, 62, 64). Drug−naïve somatic depression may show increased ALPS, possibly compensatory, highlighting state/stage heterogeneity (65).

Bipolar disorder (BD). In BD, erratic sleep–wake cycles, circadian dysregulation, and metabolic stress converge on glymphatic inefficiency. Diffusion metrics, including free−water alterations, suggest extracellular fluid shifts and astroglial involvement beyond purely neurotransmitter−based accounts (35). Frontal pole atrophy has been associated with lower ALPS, reinforcing structural–functional coupling (66). Clinically, stabilizing sleep/circadian timing and reducing inflammatory load are predicted to mitigate neuroprogression and cognitive decline (6, 67, 68).

Schizophrenia/psychosis. Characteristic abnormalities in sleep architecture, like reduced slow−wave activity and frequent awakenings, coincide with ALPS alterations and reduced BOLD−CSF clearance in early psychosis, supporting an intrinsic clearance component linked to cognitive/negative symptoms (31, 33, 69). Observations in individuals minimally exposed to antipsychotics indicate that these glymphatic changes are present early and are unlikely to be medication artifacts (60, 61). Preliminary ALPS reductions have also been noted in acutely hospitalized young adults during a first psychotic episode (70).

Post−traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Persistent hyperarousal and elevated nocturnal noradrenergic tone can suppress slow vasomotion and glymphatic throughput. ALPS index abnormalities could parallel symptom severity, suggesting a pathophysiological loop in which impaired clearance maintains stress−related molecular signatures, augments fear memory, and perpetuates sleep fragmentation (16, 34, 39).

Substance use disorders (SUD). Alcohol and stimulants disrupt sleep architecture and perivascular flow, entraining inflammatory loops that worsen cognition and relapse risk (71, 72). Diffusion and cerebral blood flow coupling analyses reveal multi−system involvement, and glymphatic metrics correlate with addiction trajectories and classification performance in methamphetamine cohorts (63, 73, 74).

Neurodevelopmental disorders (ADHD/ASD). Atypical sleep and ALPS−indexed dysfunction in youth suggest early contributions of impaired CSF–ISF exchange to attentional, executive, and social−communication trajectories (75, 76). Adult ADHD also shows reduced ALPS tracking cognitive performance (77). In pediatric ASD, a positive association between ALPS and age suggest a delayed or altered maturation of perivascular exchange in ASD (75). These associations accord with broader evidence of astrocyte−mediated circuit refinement and the vulnerability of AQP4 polarity to stress/inflammation during sensitive developmental windows (78–81).

1.3.5 Aging and risk modifiers

Vascular aging, APOE−related glial vulnerability, and chronic sleep loss synergistically lower glymphatic output and raise neurodegenerative risk, offering a parsimonious link between late−life psychiatric burden, cognitive decline, and clearance failure (14, 82–85).

1.3.6 Clinical implications and empirically testable directions

Cross−sectional: severity of insomnia, inflammatory load, and arterial stiffness will independently predict lower DTI−ALPS values and weaker BOLD−CSF coupling after adjustment for age, sex, head motion, and medication exposure. Longitudinal: within−person increases in slow−wave activity or reductions in systemic inflammatory markers (e.g., C−reactive protein) will precede, and possibly correlate with, subsequent alterations in ALPS/BOLD−CSF signals.

Interventional: CBT−I or circadian stabilization, like structured light–dark exposure, aerobic exercise, and anti−inflammatory/astroglial−supportive strategies will increase ALPS/BOLD−CSF readouts in parallel with symptomatic improvement. Conversely, interventions that enhance slow−wave sleep, restore AQP4 polarity, and improve vascular drivers (pulsatility/IPAD) should improve glymphatic metrics and clinical outcomes (17, 29, 30, 86).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Review design

This work is a narrative review that adopts selected items from the PRISMA 2020 recommendations, information sources, search strategy, eligibility criteria, study selection, and data items, but does not constitute a full systematic review. No protocol was registered; no formal risk−of−bias tool was applied; and no meta−analysis was conducted owing to heterogeneity in study designs, imaging metrics, and populations (87).

2.2 Information sources and search strategy

We searched ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus, and PubMed without date limits; English−language records only were considered. The final comprehensive database search was completed on May 31, 2025, and an update search was performed through August 2025 to capture late−breaking publications now reflected in Table 1. To contextualize emerging concepts, we also screened preprint servers (e.g., SSRN) and flagged their status explicitly in tables. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic, the research strategy included a broad set of English-language keywords identified and combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT). The search terms included “glymphatic system,” “glymphatic,” “brain lymphatic,” “cerebrospinal fluid,” “CSF,” “brain clearance,” “interstitial fluid,” “astroglial,” “neurovascular,” “DTI,” “ALPS Index,” “BOLD CSF,” “arterial spin labeling/ASL,” “free water,” “MRS/macromolecule” “psychiatric disorders,” “mental disorders,” “psychiatric conditions,” “mood disorders,” “affective disorders,” “depressive disorders,” “depression,” “bipolar disorder,” “anxiety disorder,” “panic disorder,” “phobia,” “obsessive compulsive disorder,” “OCD,” “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” “ADHD,” “autism spectrum disorder,” “ASD,” “schizophrenia,” “psychotic disorders,” “sleep disorders,” “sleep-wake disorders,” “insomnia,” “personality disorders,” “borderline personality disorder,” “narcissistic personality disorder,” “antisocial personality disorder,” “substance use disorder,” “SUD,” “trauma,” “PTSD,” “post-traumatic stress disorder,” “eating disorders,” “feeding disorders,” “bulimia,” “anorexia,” “binge eating,” “stress,” “distress,” “adjustment disorder,” and “mental illness.”

Table 1

| Author(s) | Year | Study | Location | Sample | Diagnosis | Key aims | Main measures | Key findings | Clinical/biological correlates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | 2022 | Children with autism spectrum disorder present with glymphatic system dysfunction highlighted by DTI−ALPS | China | 30 ASD, 25 HC | ASD | Test ALPS differences and age effects | DTI−ALPS | Lower ALPS in ASD; ALPS positively correlated with age in ASD | Developmental trajectory implications |

| Chen et al. | 2023 | Evaluation of glymphatic function in children with ADHD | China | 47 ADHD (drug−naïve), 52 HC | ADHD (child) | Evaluate GS impairment in ADHD | DTI−ALPS; Conners | Lower ALPS in ADHD vs HC | Links to attention/executive symptoms |

| Fang et al. | 2025 | Glymphatic dysfunction in adult ADHD: relationship to cognitive performance | USA | 41 ADHD−adult, 123 HC | ADHD (adult) | Test ALPS–cognition associations | DTI−ALPS; CVLT; symptom scales | Lower ALPS relates to memory/executive deficits | Cognitive impairment linkage |

| Ueda et al. | 2024 | Glymphatic system dysfunction in mood disorders | Japan | 58 BD, 66 HC | Bipolar disorder | Test glymphatic alterations in BD | DTI−ALPS; FWI; HAMD; YMRS | No robust ALPS difference; increased free water (callosal) suggests neuroinflammation | Fluid/inflammatory signatures |

| Kikuta et al. | 2025 | Association between frontal−pole atrophy and glymphatic dysfunction in BD | Japan | MRI cohort (BD) | Bipolar disorder | Link regional atrophy to glymphatic metrics | DTI−ALPS; cortical thickness | Frontal−pole atrophy associates with lower ALPS | Neurodegeneration−clearance nexus. |

| Yang et al. | 2024 | Glymphatic function and white−matter alterations in MDD (reviewed/quantified) | China | 35 MDD, 23 HC | MDD | Assess ALPS in MDD & white−matter microstructure | DTI−ALPS; DTI metrics; HAMD/HAMA/MoCA | Lower ALPS in MDD; associations with WM abnormalities | Cognitive & anxiety burden; WM changes. |

| Bao et al. | 2025 | Glymphatic dysfunction in MDD revealed by DTI−ALPS: correlation with fatigue | China | 46 MDD, 55 HC | MDD | Test ALPS vs fatigue/depression | DTI−ALPS; HAMD; Chalder Fatigue | Lower ALPS in MDD; links to fatigue severity | Fatigue pathophysiology |

| Gong et al. | 2025 | Glymphatic function & ChP volume linked to systemic inflammation/oxidative stress in MDD | China | 665 MDD, 338 HC | MDD | Relate ALPS & ChP to immune markers | DTI−ALPS; automated ChP; blood indices | Larger ChP & lower ALPS in MDD; ALPS correlates with NLR/PLR/SII in MDD compared to HC | Immune–CSF–clearance axis. |

| Chen et al. | 2025 | Glymphatic dysfunction associated with cortisol dysregulation in MDD | China | MDD cohort + HC | MDD | Test ALPS vs HPA/cortisol | DTI−ALPS; diurnal cortisol | Lower ALPS correlates with cortisol dysregulation | HPA–glymphatic coupling |

| Liang et al. | 2025 | Inflammation and psychomotor retardation in depression: moderating role of GS | China | 67 MDD, 67 HC | MDD | Does ALPS moderate inflammation–PMR | DTI−ALPS; hsCRP; PMR; motor FC | Lower ALPS magnifies hsCRP–PMR link; ALPS moderates motor−network effects | Inflammation–motor circuit coupling. |

| Deng et al. | 2025 | Increased GS activity & thalamic vulnerability in drug−naïve somatic depression | China | 272 total (SMD, PMD, HC) | MDD (SMD/PMD) | Compare ALPS among subgroups | DTI−ALPS; VBM thalamus | Higher ALPS (awake) in MDD—esp. SMD; ALPS–thalamus volume positive correlation | State−dependent activity; thalamic link. |

| Tao et al. | 2025 | Altered DMN and glymphatic function in insomnia with depression | China | 60 CID+MDD, 52 CID−only, 56 HC | CID ± MDD | Examine DMN–glymph coupling | DTI−ALPS; rs−fMRI; PSQI/HAMD | DMN disruption parallels ALPS changes in CID comorbid with MDD | Sleep–glymph–mood interactions |

| Korann et al. | 2025 | Dysregulation of the glymphatic system in psychosis with minimal antipsychotics | Canada | 13 psychosis (minimally exposed), 123 HC | Psychotic spectrum | Test ALPS in early/limited exposure | DTI−ALPS; EPS scales | Lower ALPS vs HC despite minimal exposure | Intrinsic alteration beyond medication. |

| Tu et al. | 2024 | Glymphatic dysfunction in schizophrenia associates with cognitive impairment | China | 43 SZ, 108 HC | Schizophrenia | Link ALPS to cognition/symptoms | DTI−ALPS; SAPS/SANS; cognition | Lower ALPS in SZ; associations with cognition | Negative/cognitive symptom load. |

| Abdolizadeh et al. | 2024 | Glymphatic evaluation with macromolecules & DTI−ALPS in SZ | Canada | 103 SZ, 47 HC | Schizophrenia | Test macromolecule diffusivity vs ALPS | DTI−ALPS; 1H−MRS macromolecules | Lower ALPS in SZ; macromolecules not different | Candidate clearance deficit. |

| Hua et al. | 2025 | Reduced glymphatic clearance in early psychosis | China | Early psychosis cohort | Early psychosis | Assess early−stage clearance | BOLD–CSF coupling; ALPS | Reduced clearance early; links to symptoms | Early biomarker potential |

| Wu et al. | 2025 | GS dysfunction correlates with gut dysbiosis & cognition in SZ | China | SZ + HC; microbiome | Schizophrenia | Integrate microbiome and ALPS | DTI−ALPS; 16S microbiome; cognition | ALPS reduction tracks dysbiosis and cognitive loss | Microbiome–glymph axis. |

| Shao et al. | 2024 | Linking ALPS with cortical microstructure in PTSD | China | 67 male veterans | PTSD | Detect early neurodegenerative signal | DTI−ALPS; cortical MD; neurocognitive scales | Lower ALPS associates with increased cortical MD | Neurodegeneration−vulnerability |

| Dai et al. | 2024 | DTI−ALPS and cognition in alcohol use disorder | China | 40 AUD, 40 HC | Alcohol use disorder | Test ALPS–cognition | DTI−ALPS; MoCA/MMSE | Lower ALPS correlates with cognitive deficits | Memory/executive burden. |

| Wang et al. | 2023 | Glymphatic function in heroin dependence on methadone | China | 51 MMT, 48 HC, 20 HD | Opioid use | Relate GS to addiction/relapse | DTI−ALPS; clinical outcomes | ALPS associates with outcomes during MMT | Relapse risk & inflammation. |

| Cheng et al. | 2025 | ALPS–CBF coupling in methamphetamine dependence | China | 46 METH, 46 HC | Methamphetamine | Improve classification | DTI−ALPS; ASL−CBF; ML models | ALPS–CBF coupling improves discrimination | Vascular–perivascular interplay |

| Barlattani et al. | 2025 | GS dysfunction in young adults hospitalized for acute psychosis (pilot) | Italy | First−episode cohort | Acute psychosis | Feasibility and signal | DTI−ALPS; SCADIS; PSQI, MoCA | Preliminary ALPS abnormality during acute psychosis | Acute−state biomarker. |

| Ma et al. (preprint) | 2025 | Glymphatic–rumination relationship in MDD | China/HK | 51 MDD, 45 HC | MDD | Test ALPS rumination/depression | DTI−ALPS; RRS/HAMD; static/dynamic FC; PET maps | Lower ALPS associates with rumination; FC/dFC and neurotransmitter maps link ALPS, rumination and depression | Candidate cognitive mediator |

Summary of human neuroimaging studies examining glymphatic-related MRI measures across psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, including key aims, methods, findings, and clinical correlates.

ALPS, Analysis Along the Perivascular Space; CP(V), choroid plexus (volume); DMN, default mode network; d/sFC, dynamic/static functional connectivity; PMR, psychomotor retardation; CID, chronic insomnia disorder.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

We included experimental, observational, and theoretical articles that examined or discussed glymphatic−related physiology CSF/ISF exchange, perivascular flow, ALPS/BOLD−CSF/ASL markers, AQP4/astroglia, meningeal lymphatics in relation to psychiatric conditions mood, psychotic, anxiety/trauma−related, substance−use, neurodevelopmental. Human and relevant preclinical studies were eligible. Studies were also included when glymphatic metrics were explicitly linked to: endocrine measures, microbiome features, structural interfaces, or transdiagnostic constructs. Preprints were cite for background and clearly identified; they were not pooled with peer−reviewed MRI outcomes in any quantitative synthesis.

2.4 Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and then full texts against prespecified criteria; disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. Duplicates across databases were removed before screening using a reference−management workflow. The August 2025 update search was screened with the same procedure and labeled by publication status (peer−reviewed vs. preprint).

2.5 Data extraction and synthesis approach

For each record, two reviewers extracted study design; sample and diagnosis; imaging method (DTI−ALPS, BOLD−CSF, ASL, free water, MRS/other) and primary glymphatic metrics; direction of effect versus controls; clinical correlates (symptoms, cognition, disease duration, inflammatory/oxidative markers); medication exposure; and potential confounders (sleep measures, time−of−day/circadian phase, vascular/metabolic comorbidity). Additional fields captured update−driven correlates (HPA/cortisol assay and timing; gut microbiome pipeline and diversity/taxa summaries; choroid plexus/frontal pole volumes; rumination scales). Publication status was recorded. Extraction used a piloted template. Given heterogeneity, we conducted a structured narrative synthesis, grouping findings by mechanistic pathway (clearance−centric, sleep–circadian, vascular–metabolic–immune) and diagnosis. To enhance transparency, Table 1 summarizes human studies across conditions and MRI methods, and Table 2 compiles methods/targets to enhance glymphatic clearance. We qualitatively appraised recurrent biases (head motion; sedation/sleep state; circadian timing; medication exposure, including “minimal exposure” in early psychosis; vascular/metabolic comorbidity; scanner/pipeline heterogeneity; cortisol assay timing; microbiome pre−analytics/analytics).

Table 2

| Lever/intervention | Primary target(s) on glymphatic pathway | Evidence level | Population/sample | Glymphatic proxy/readout | Clinical/biological correlates | Notes/psychiatric applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT−I; sleep consolidation | Increased deep NREM; decreased arousal/noradrenergic tone; increased vasomotion | Clinical evidence and mechanistic studies | Insomnia, MDD, mixed | BOLD−CSF coupling; sleep macro−architecture | Reduction in depression severity; improved cognition | Foundational lever in mood/psychosis with insomnia (6, 26). |

| Light−dark scheduling/chronotherapy | Circadian alignment; AQP4 polarization | Clinical practice + reviews | Mood disorders | Indirect (sleep/circadian markers) | Improved sleep timing, daytime function | Align med timing with clearance windows (88, 89). |

| Aerobic exercise | Increased vascular pulsatility; anti−inflammatory; astroglial support | Preclinical + human associative | Older adults; MDD | Indirect; DTI−ALPS where available | Memory/cognition benefits; anti−inflammatory | AQP4−dependent benefits in models (54). |

| Lateral sleep posture; slow breathing | Reduction in venous outflow resistance; entrain CSF with respiration | Preclinical + human physio | Healthy; patient groups | CSF flow surrogates | Better coupling of cardiac/respiratory drivers | Low−risk adjuncts (14, 16, 24). |

| rTMS (older adults) | Network−level modulation; sleep and vascular coupling | Early clinical signal | Older adults | “Glymphatic proxies” + cognition | Cognitive improvement | Mechanistic bridge to psychiatry; needs target−engagement biomarkers (90). |

| 40 Hz multisensory (“gamma”) stimulation | Gamma entrainment favors neurovascular/meningeal coupling; Admeloriate paravascular clearance | Preclinical (mouse), high−impact | Amyloid mouse models | CSF/perivascular clearance; amyloid reduction | Improved behavioral readouts | Translational potential to psychiatric cohorts with disrupted sleep/network dynamics; human feasibility needed (91). |

| Melatonin | Circadian/AQP4 polarity; antioxidative | Preclinical + early clinical | Sleep loss, ICH models | AQP4 polarity; cognitive & BBB outcomes | Sleep alignment; cognitive benefit | Candidate chronobiotic in mood/PTSD (92–94). |

| Omega−3 PUFAs | Vascular/astroglial integrity | Preclinical + small clinical | Depression/cognition | Indirect; vascular markers | Cognitive & mood benefits | Pro−glymphatic vascular support (95, 96). |

| Lithium | Choroid plexus clock; CSF production dynamics | Preclinical/physiology | Bipolar disorder | Indirect (CP clock) | Mood stabilization | May influence day–night CSF rhythms (97). |

| Dexmedetomidine | NE−sparing sedation; increased intrathecal drug delivery; protect AQP4 pathways | Preclinical + peri−op studies | Surgical/ICU; TRD pilots | Tracer delivery; conceptual proxies | Antidepressant−like signals in TRD | Time−sensitive, “glymphatic−friendly” sedation candidate (98–100). |

| Ketamine/esketamine | NMDA modulation; astroglial effects | Preclinical mixed + clinical efficacy | Depression | Conflicting preclinical glymph findings | Rapid antidepressant effects | Mixed glymphatic signals (impair vs improve via astrocyte pyroptosis); consider dose/timing/context (101, 102). |

| Benzodiazepines; late−evening alcohol; zolpidem | Decreased REM & SWS quality; disrupt NE slow vasomotion | Observational/mechanistic | Insomnia; SUD | Sleep architecture; NE oscillations | Worsened sleep, cognition | Use sparingly/strategically; potential anti−glymphatic effects (39, 71, 103). |

Summarizes pharmacologic, behavioral, and device−based options highlighting targets, readouts, and psychiatric use−cases with putative glymphatic effects.

3 Characteristics of neuroimaging studies in patients with psychiatric pathology and clinical insights

3.1 Study landscape across diagnoses

Human neuroimaging studies that use diffusion‐MRI proxies of perivascular transport predominantly DTI−ALPS, BOLD–CSF coupling, or ASL consistently suggest glymphatic alterations across major psychiatric disorders Figure 2. In MDD, ALPS reductions co−occur with inflammatory and oxidative signatures and choroid plexus (ChP) changes, pointing to a CSF–immune–clearance axis (17, 62). Recent work also links lower ALPS indices to dysregulated diurnal cortisol secretion in major depressive disorder, highlighting a potential HPA–glymphatic coupling (104). An additional multicenter analysis indicates that glymphatic function moderates the link between peripheral inflammation and psychomotor retardation (PMR) in MDD, i.e., lower ALPS amplifies inflammation−related PMR and motor−network alterations (105). Notably, one large study in drug−naïve somatic depression reports higher ALPS (vs controls) during wakefulness, correlating with thalamic volume, interpreted as heightened daytime activity and thalamic vulnerability rather than overall “better clearance” (65). Preliminary preprint data also suggest that reduced ALPS values are associated with higher rumination severity and specific functional-connectivity patterns in major depressive disorder (106). In schizophrenia and early psychosis, ALPS reductions relate to cognitive deficits and are present in minimally medicated cohorts (60, 61). Emerging work links glymphatic metrics with gut dysbiosis and cognition, positioning the microbiome–meningeal–CSF axis as a candidate mechanism (107).

Figure 2

The top image illustrates a healthy glymphatic system, efficiently clearing waste and adapting to changing conditions. The bottom image shows chronic glymphatic dysfunction, characterized by a reduced ALPS index, dilated perivascular spaces, waste accumulation, extracellular fluid buildup, and decreased outflow. Legend: FW: free water; PVSVF: perivascular spaces venous flow; WM: waste matter; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; ALPS: along perivascular spaces; AQP4: aquaporin 4; ISF: interstitial fluid.

In BD, a diffusion−MRI study reported free−water increases, suggesting neuroinflammatory/extracellular fluid changes, without robust ALPS differences (35). Independent work associates frontal−pole atrophy with glymphatic dysfunction in BD (66).

In PTSD, higher cortical mean diffusivity in regions vulnerable to neurodegeneration correlates with lower ALPS (34). SUD show ALPS abnormalities and clinically meaningful ALPS–CBF coupling that aids classification in methamphetamine dependence (63), and ALPS–cognition associations in alcohol use disorder (73).

Neurodevelopmental disorders, ALPS reductions are reported in ASD and in ADHD, both children and adults, with links to age and cognition (75–77).

Insomnia with depression shows concurrent default mode network dysfunction and glymphatic alterations (108). A preliminary acute psychosis pilot study during early hospitalization suggests ALPS abnormalities in young adults (70).

3.2 Imaging readouts and their correlates

Most studies used DTI−ALPS with atlas−constrained ROIs; several adjusted for age, sex, education, and motion; fewer accounted for time−of−day or sleep. Consistent correlates include depression severity (HAMD), fatigue, cognition, systemic inflammation/oxidative stress indices (NLR, PLR, SII, etc.), and ChP volume (62). In major depressive disorder, ALPS reductions have also been linked to tract-specific white-matter alterations, reinforcing the connection between glymphatic metrics and microstructural integrity (109). In schizophrenia/psychosis, ALPS tracks cognitive impairment (61) and appears reduced even with minimal antipsychotic exposure (60).

3.3 Clinical insights and mechanistic threads

Convergent threads suggest that sleep–circadian disruption, vascular/IPAD changes, astroglial/AQP4 polarity, and immune–ChP signaling jointly shape glymphatic measures in psychiatric populations. Large−scale MDD data indicate ChP enlargement and lower ALPS with stronger ties to inflammatory ratios in patients than controls, consistent with a peripheral–central inflammatory bridge modulating CSF production and clearance (62). Conversely, when assessed during wakefulness, elevated ALPS in somatic−symptom MDD may reflect state−dependent disinhibition of daytime glymphatic activity (65).

3.4 Methodological notes

Medication exposure, time−of−day, sleep the night before scanning, and vascular risk vary across studies. Importantly, some reports include medication−naïve or minimally exposed cohorts (60, 65), strengthening causal inferences to the disease process. Multi−modal combinations, ALPS and CBF, enhance classification and may help disentangle vascular from perivascular drivers (63).

4 A glymphatic-oriented paradigm in psychiatric pharmacotherapy

Growing awareness of the glymphatic system raises the question of whether enhancing paravascular flow might optimize pharmacotherapy. Traditionally, psychiatric medications have been formulated and dosed with a primary emphasis on neurotransmitter or receptor targets. However, many agents linger in the CNS and often cause sedation or metabolic disturbances. In contexts of impaired glymphatic clearance, driven by insomnia, chronic inflammation, or circadian misalignment, drugs may accumulate or distribute unevenly, exacerbating lethargy and cognitive side effects (1, 2, 6, 49). By contrast, sedative strategies that conserve or deepen slow−wave sleep could expand extracellular spaces and support more efficient clearance of metabolic waste and residual drugs (15, 110). Interventions that bolster astrocyte functionality (e.g., anti−inflammatory strategies that stabilize AQP4 polarization) and circadian alignment, timing medications when glymphatic flow peaks (89, 111), are convergent levers that may improve both efficacy and tolerability (17, 26, 30, 88, 112).

Non−pharmacological levers complement medication strategies. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, structured light–dark exposure, and aerobic exercise improve sleep consolidation and vascular pulsatility, both key drivers of CSF–ISF exchange (6, 17, 30). Postural habits, in particular favoring lateral recumbency during sleep, and slow, regular breathing can also support perivascular transport (14, 16, 24). Emerging neuromodulation adds a mechanistic foothold: in older adults, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been reported to modulate putative glymphatic proxies alongside cognitive outcomes, suggesting a network−level pathway to “glymphatic−friendly” brain states translatable to psychiatric populations (90).

Network−level neuromodulation and sensory entrainment. Beyond rTMS, multisensory 40 Hz “gamma” stimulation, delivered via synchronized visual and auditory stimuli, has been shown in mouse models to promote glymphatic clearance of amyloid, likely by coupling neuronal oscillations to neurovascular dynamics and meningeal/lymphatic outflow pathways (91). Gamma entrainment reduced amyloid burden and improved behavioral readouts in preclinical settings, with concomitant signatures consistent with enhanced perivascular transport. While clinical translation to psychiatric cohorts remain exploratory, this approach could be mechanistically appealing for disorders marked by sleep fragmentation, neuroinflammation, and impaired network dynamics, as it could jointly influence vasomotion, arousal state, and astroglial physiology, all key determinants of glymphatic throughput. Early feasibility work in humans is needed to establish target engagement (e.g., BOLD−CSF coupling, DTI−ALPS) and symptom relevance.

Pharmacologic levers, dosing time, and sleep architecture. Melatonin may realign circadian timing and AQP4 polarity, while omega−3 PUFAs protect cerebrovascular and astroglial integrity, both plausibly pro−glymphatic and symptom−relevant in mood disorders (64, 92, 93, 95, 96, 113). Lithium’s effects on the choroid plexus clock hint at leverage via CSF production and day–night dynamics (97). Among sedatives, dexmedetomidine may be “glymphatic−friendly,” enhancing intrathecal drug delivery and potentially countering anesthetic−induced glymphatic disruption (98–100). By contrast, chronic benzodiazepine use, and late−evening alcohol may degrade sleep architecture and fluid transport, and zolpidem reduces norepinephrine slow−wave dynamics implicated in vasomotion and CSF movement, arguing for sparing, time−sensitive use (39, 71, 103). Ketamine shows mixed glymphatic effects across preclinical paradigms, both impairment and improvement have been reported, underscoring the importance of dose, timing, and disease context (101, 102). A preliminary, non– peer−reviewed report suggests that pairing esketamine with dexmedetomidine−based sleep modulation may accelerate antidepressant response and improve sleep in patients with depression and insomnia, a concept consistent with pro−glymphatic interventions but awaiting confirmation in randomized, peer−reviewed trials (114).

Collectively, “glymphatic−friendly” practice may include: prioritizing NREM−deepening over nonspecific sedation; aligning dosing to circadian windows of heightened clearance; supporting astrocyte health and vascular pulsatility; and integrating neuromodulatory or behavioral tools that stabilize network and autonomic dynamics central to perivascular flow. Table 2 summarizes pharmacologic, behavioral, and device−based options highlighting targets, readouts, and psychiatric use−cases.

5 Conclusion

Viewing the brain as an organ that depends on nightly fluid clearance reframes psychiatric pathophysiology and care. Convergent evidence, from DTI−ALPS, CSF−BOLD and ASL coupling, choroid−plexus and inflammatory correlates, and preliminary interventional work, indicates that disrupted glymphatic function can perpetuate neuroinflammation, cognitive−affective symptoms, and suboptimal pharmacotherapy response in mood, psychotic, trauma−related, substance−use, and neurodevelopmental disorders (32, 34, 60, 62, 115). A glymphatic−oriented paradigm, preserving slow−wave sleep, aligning dosing to circadian biology, supporting astroglial and vascular health, and selectively leveraging agents such as dexmedetomidine, melatonin, and PUFAs while clarifying the role of ketamine and ensuring the judicious use of hypnotics, offers actionable paths to improve outcomes. Prospective trials that combine symptom scales with objective glymphatic readouts (e.g., ALPS, CSF−BOLD) are warranted to define who benefits, by how much, and with which combinations of behavioral, device−based, and pharmacologic interventions (17, 30, 90).

Statements

Author contributions

TB: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. AC: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. AB: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. VS: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. ET: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MM: Writing – review & editing. AR: Writing – review & editing. VM: Writing – review & editing. CT: Writing – review & editing. DD: Writing – review & editing. GD: Writing – review & editing. FP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. GD was supported by #NEXTGENERATIONEU (NGEU) and funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), project MNESYS (PE0000006) – (DN. 1553 11.10.2022).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors declare that they used ChatGPT (OpenAI) for language editing and proofreading. The authors confirm that they have verified the accuracy of all content, including citations, references, and data, and accept full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the results presented. In accordance with Frontiers’ guidelines and the ICMJE criteria, ChatGPT was not listed as an author because it cannot be held responsible for the content of the manuscript and does not meet the necessary requirements for scientific authorship.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Carotenuto A Cacciaguerra L Pagani E Preziosa P Filippi M Rocca MA . Glymphatic system impairment in multiple sclerosis: relation with brain damage and disability. Brain. (2021) 145:2785–95. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab454

2

Engelhardt B Ransohoff RM . Capture, crawl, cross: the T cell code to breach the blood–brain barriers. Trends Immunol. (2012) 33:579–89. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.004

3

Zhang J Yao W Hashimoto K . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-trkB signaling in inflammation-related depression and potential therapeutic targets. Curr Neuropharmacology. (2016) 14:721–31. doi: 10.2174/1570159x14666160119094646

4

Dunn GA Loftis JM Sullivan EL . Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: An introductory primer. Pharmacology Biochemistry Behav. (2020) 196:172981. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172981

5

Riemann D . Insomnia and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Sleep Med. (2007) 8:S15–20. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(08)70004-2

6

Riemann D Krone LB Wulff K Nissen C . Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (2020) 45:74–89. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0411-y

7

Braak H Braak E . Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica. (1991) 82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/bf00308809

8

Salcedo C Pozo Garcia V García-Adán B Ameen AO Gegelashvili G Waagepetersen HS et al . Increased glucose metabolism and impaired glutamate transport in human astrocytes are potential early triggers of abnormal extracellular glutamate accumulation in hiPSC-derived models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochemistry. (2024) 168:822–40. doi: 10.1111/JNC.16014

9

Barlattani T Grandinetti P Cintio A Montemagno A Testa R D’Amelio C et al . Glymphatic system and psychiatric disorders: A rapid comprehensive scoping review. Curr Neuropharmacology. (2024) 22:2016–33. doi: 10.2174/1570159X22666240130091235

10

Verkhratsky A Nedergaard M . Physiology of astroglia. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:239–389. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2016

11

Andreazza AC Duong A Young LT . Bipolar disorder as a mitochondrial disease. Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 83:720–1. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.018

12

Eide PK Valnes LM Pripp AH Mardal K-A Ringstad G . Delayed clearance of cerebrospinal fluid tracer from choroid plexus in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabolism: Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2020) 40:1849–58. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19874790

13

Redzic ZB Preston JE Duncan JA Chodobski A Szmydynger-Chodobska J . The choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system: from development to aging. Curr Topics Dev Biol. (2005) 71:1–52. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)71001-2

14

Iliff JJ Wang M Liao Y Plogg BA Peng W Gundersen GA et al . A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Trans Med. (2012) 4:147ra111–147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748

15

Salman MM Kitchen P Iliff JJ Bill RM . Aquaporin 4 and glymphatic flow have central roles in brain fluid homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2021) 22:650–1. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00514-z

16

Xie L Kang H Xu Q Chen MJ Liao Y Thiyagarajan M et al . Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Sci (New York N.Y.). (2013) 342:373–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224

17

He Y Guan J Lai L Zhang X Chen B Wang X et al . Imaging of brain clearance pathways via MRI assessment of the glymphatic system. Aging. (2023) 15:14945–56. doi: 10.18632/aging.205322

18

Aspelund A Antila S Proulx ST Karlsen TV Karaman S Detmar M et al . A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. (2015) 212:991–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290

19

Kida S Pantazis A Weller RO . CSF drains directly from the subarachnoid space into nasal lymphatics in the rat. Anatomy, histology and immunological significance. Neuropathology Appl Neurobiol. (1993) 19:480–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00476.x

20

Louveau A Plog BA Antila S Alitalo K Nedergaard M Kipnis J . Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:3210–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI90603

21

Scallan JP Zawieja SD Castorena-Gonzalez JA Davis MJ . Lymphatic pumping: mechanics, mechanisms and malfunction. J Physiol. (2016) 594:5749–68. doi: 10.1113/JP272088

22

Da Mesquita S Fu Z Kipnis J . The meningeal lymphatic system: A new player in neurophysiology. Neuron. (2018) 100:375–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.022

23

Aldea R Weller RO Wilcock DM Carare RO Richardson G . Cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells as the drivers of intramural periarterial drainage of the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. (2019) 11:1/FULL. doi: 10.3389/FNAGI.2019.00001/FULL

24

Rasmussen MK Mestre H Nedergaard M . The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. (2018) 17:1016–24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30318-1

25

Mestre H Hablitz LM Xavier AL Feng W Zou W Pu T et al . Aquaporin-4-dependent glymphatic solute transport in the rodent brain. ELife. (2018) 7:e40070. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40070

26

Benveniste H Heerdt PM Fontes M Rothman DL Volkow ND . Glymphatic system function in relation to anesthesia and sleep states. Anesth Analgesia. (2019) 128:747–58. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000004069

27

Nair VV Kish BR Oshima H Wright AM Wen Q Schwichtenberg AJ et al . Amplitude fluctuations of cerebrovascular oscillations and CSF movement desynchronize during NREM3 sleep. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2025). doi: 10.1177/0271678X251337637. 0271678X251337637.

28

Rábago-Monzón Á.R Osuna-Ramos JF Armienta-Rojas DA Camberos-Barraza J Camacho-Zamora A Magaña-Gómez JA et al . Stress-induced sleep dysregulation: the roles of astrocytes and microglia in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Biomedicines. (2025) 13:1121. doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES13051121

29

Ringstad G . Glymphatic imaging: a critical look at the DTI-ALPS index. Neuroradiology. (2024) 66:157–60. doi: 10.1007/s00234-023-03270-2

30

Taoka T Ito R Nakamichi R Nakane T Kawai H Naganawa S . Diffusion tensor image analysis ALong the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS): revisiting the meaning and significance of the method. Magnetic Resonance Med Sciences: MRMS: Off J Japan Soc Magnetic Resonance Med. (2024) 23:268–90. doi: 10.2463/mrms.rev.2023-0175

31

Abdolizadeh A Torres-Carmona E Kambari Y Amaev A Song J Ueno F et al . Evaluation of the glymphatic system in schizophrenia spectrum disorder using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurement of brain macromolecule and diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space index. Schizophr Bull. (2024) 50:1396–410. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbae060

32

Bao W Jiang P Xu P Lin H Xu J Lai M et al . Lower DTI-ALPS index in patients with major depressive disorder: Correlation with fatigue. Behav Brain Res. (2025) 478:115323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2024.115323

33

Hua L Zeng X Zhang K Zhao Z Yuan Z . Reduced glymphatic clearance in early psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41380-025-03058-1

34

Shao Z Gao X Cen S Tang X Gong J Ding W . Unveiling the link between glymphatic function and cortical microstructures in post-traumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. (2024) 365:341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.094

35

Ueda R Yamagata B Niida R Hirano J Niida A Yamamoto Y et al . Glymphatic system dysfunction in mood disorders: Evaluation by diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroscience. (2024) 555:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.07.026

36

Plog BA Nedergaard M . The glymphatic system in central nervous system health and disease: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Pathology: Mech Dis. (2018) 13:379–94. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-PATHOL-051217-111018

37

Petrova TV Koh GY . Organ-specific lymphatic vasculature: From development to pathophysiology. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:35–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171868

38

Miteva DO Rutkowski JM Dixon JB Kilarski W Shields JD Swartz MA . Transmural flow modulates cell and fluid transport functions of lymphatic endothelium. Circ Res. (2010) 106:920–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207274

39

Hauglund NL Andersen M Tokarska K Radovanovic T Kjaerby C Sørensen FL et al . Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep. Cell. (2025) 188:606–622.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.027

40

Breslin JW Yang Y Scallan JP Sweat RS Adderley SP Murfee WL . Lymphatic vessel network structure and physiology. Compr Physiol. (2018) 9:207–99. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c180015

41

Das N Dhamija R Sarkar S . The role of astrocytes in the glymphatic network: a narrative review. Metab Brain Dis. (2023) 39:453–65. doi: 10.1007/s11011-023-01327-y

42

Fernández-Arjona MDM Grondona JM Granados-Durán P Fernández-Llebrez P López-Ávalos MD . Microglia morphological categorization in a rat model of neuroinflammation by hierarchical cluster and principal components analysis. Front Cell Neurosci. (2017) 11:235. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00235

43

de Ceglia R Ledonne A Litvin DG Lind BL Carriero G Latagliata EC et al . Specialized astrocytes mediate glutamatergic gliotransmission in the CNS. Nature. (2023) 622:120–9. doi: 10.1038/S41586-023-06502-W

44

Mogensen FLH Delle C Nedergaard M . The glymphatic system (En)during inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:7491. doi: 10.3390/IJMS22147491

45

Szlufik S Kopeć K Szleszkowski S Koziorowski D . Glymphatic system pathology and neuroinflammation as two risk factors of neurodegeneration. Cells. (2024) 13:286. doi: 10.3390/cells13030286

46

Bellier F Walter A Lecoin L Chauveau F Rouach N Rancillac A . Astrocytes at the heart of sleep: from genes to network dynamics. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2025) 82. doi: 10.1007/S00018-025-05671-3

47

Sun Y Lv Q-K Liu J-Y Wang F Liu C-F . New perspectives on the glymphatic system and the relationship between glymphatic system and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. (2025) 205:106791. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2025.106791

48

Cai Y Zhang Y Leng S Ma Y Jiang Q Wen Q et al . The relationship between inflammation, impaired glymphatic system, and neurodegenerative disorders: A vicious cycle. Neurobiol Dis. (2024) 192:106426. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106426

49

Hablitz LM Plá V Giannetto M Vinitsky HS Stæger FF Metcalfe T et al . Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4411. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18115-2

50

Gao Y Liu K Zhu J . Glymphatic system: an emerging therapeutic approach for neurological disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. (2023) 16:1138769. doi: 10.3389/FNMOL.2023.1138769

51

Deane R Du Yan S Submamaryan RK LaRue B Jovanovic S Hogg E et al . RAGEmediates amyloid-β peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. (2003) 9:907–13. doi: 10.1038/nm890

52

Maiese K . Diabetes mellitus and glymphatic dysfunction: Roles for oxidative stress, mitochondria, circadian rhythm, artificial intelligence, and imaging. World J Diabetes. (2025) 16. doi: 10.4239/WJD.V16.I1.98948

53

Martini E . Norepinephrine oscillations regulate glymphatic clearance during spleen. Nat Cardiovasc Res. (2025) 4:121–1. doi: 10.1038/s44161-025-00616-2

54

Liu Y Hu P-P Zhai S Feng W-X Zhang R Li Q et al . Aquaporin 4 deficiency eliminates the beneficial effects of voluntary exercise in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regeneration Res. (2022) 17:2079–88. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.335169

55

Bottaccioli AG Bottaccioli F Minelli A . Stress and the psyche–brain–immune network in psychiatric diseases based on psychoneuro endocrine immunology: a concise review. Ann New York Acad Sci. (2018) 1437:31–42. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13728

56

Grommes C Lee CYD Wilkinson BL Jiang Q Koenigsknecht-Talboo JL Varnum B et al . Regulation of microglial phagocytosis and inflammatory gene expression by Gas6 acting on the Axl/Mer family of tyrosine kinases. J NeuroImmune Pharmacol. (2008) 3:130–40. doi: 10.1007/S11481-007-9090-2

57

Yan T Qiu Y Yu X Yang L . Glymphatic dysfunction: A bridge between sleep disturbance and mood disorders. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:658340. doi: 10.3389/FPSYT.2021.658340

58

Gaberel T Gakuba C Goulay R De Lizarrondo SM Hanouz J-L Emery E et al . Impaired glymphatic perfusion after strokes revealed by contrast-enhanced MRI. Stroke. (2014) 45:3092–6. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.114.006617

59

Pelletier A Periot O Dilharreguy B Hiba B Bordessoules M Chanraud S et al . Age-related modifications of diffusion tensor imaging parameters and white matter hyperintensities as inter-dependent processes. Front Aging Neurosci. (2016) 7:255. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00255

60

Korann V Panganiban KJ Stogios N Remington G Graff-Guerrero A Chintoh A et al . The dysregulation of the glymphatic system in patients with psychosis spectrum disorders minimally exposed to antipsychotics. Biol Psychiatry. (2025) 97:S323–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2025.02.786

61

Tu Y Fang Y Li G Xiong F Gao F . Glymphatic system dysfunction underlying schizophrenia is associated with cognitive impairment. Schizophr Bull. (2024) 50:1223–31. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbae039

62

Gong W Zhai Q Wang Y Shen A Huang Y Shi K et al . Glymphatic function and choroid plexus volume is associated with systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in major depressive disorder. Brain Behavior Immun. (2025) 128:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2025.04.008

63

Cheng P Li Y Wang S Liang L Zhang M Liu H et al . Coupling analysis of diffusion tensor imaging analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) with abnormal cerebral blood flow in methamphetamine-dependent patients and its application in machine-learning-based classification. J Affect Disord. (2025) 376:463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.02.020

64

Chen J Zeng X Wang L Zhang W Li G Cheng X et al . Mutual regulation of microglia and astrocytes after Gas6 inhibits spinal cord injury. Neural Regeneration Res. (2025) 20:557–73. doi: 10.4103/NRR.NRR-D-23-01130

65

Deng Z Wang W Nie Z Ma S Zhou E Xie X et al . Increased glymphatic system activity and thalamic vulnerability in drug-naïve somatic depression: Evidenced by DTI-ALPS index. NeuroImage. Clin. (2025) 46:103769. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2025.103769

66

Kikuta A Yamagata B Niida R Hirano J Niida A Yamamoto Y et al . Association between frontal-pole atrophy and glymphatic dysfunction in BD. J Affect Disord. (2025) 389:119686. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.119686

67

Alloy LB Nusslock R Boland EM . The development and course of bipolar spectrum disorders: an integrated reward and circadian rhythm dysregulation model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2015) 11:213–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112902

68

Harvey AG Talbot LS Gershon A . Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder across the lifespan. Clin Psychology: A Publ Division Clin Psychol Am psychol Assoc. (2009) 16:256–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01164.x

69

Ferrarelli F . Sleep abnormalities in schizophrenia: state of the art and next steps. Am J Psychiatry. (2021) 178:903–13. doi: 10.1176/APPI.AJP.2020.20070968

70

Barlattani T De Luca D Giambartolomei S Bologna A Innocenzi A Bruno F et al . Glymphatic system dysfunction in young adults hospitalized for an acute psychotic episode: A preliminary report from a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. (2025) 16:1653144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1653144

71

Koob GF Colrain IM . Alcohol use disorder and sleep disturbances: a feed-forward allostatic framework. Neuropsychopharmacology: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (2020) 45:141–65. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0446-0

72

Chen W Huang P Zeng H Lin J Shi Z Yao X . Cocaine-induced structural and functional impairments of the glymphatic pathway in mice. Brain Behavior Immun. (2020) 88:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.057

73

Dai X Gao L Zhang J Li X Yu J Yu L et al . Investigating DTI-ALPS index and its association with cognitive impairments in patients with alcohol use disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J Psychiatr Res. (2024) 180:213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.10.008

74

Wang L Qin Y Li X Li X Liu Y Li W et al . Glymphatic-system function is associated with addiction and relapse in heroin dependents undergoing methadone maintenance treatment. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1292. doi: 10.3390/BRAINSCI13091292

75

Li X Ruan C Zibrila AI Musa M Wu Y Zhang Z et al . Children with autism spectrum disorder present glymphatic system dysfunction evidenced by diffusion tensor imaging along the perivascular space. Medicine. (2022) 101:e32061–1. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000032061

76

Chen Y Wang M Su S Dai Y Zou M Lin L et al . Assessment of the glymphatic function in children with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Radiol. (2023) 34:1444–52. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-10220-2

77

Fang Y Peng J Chu T Gao F Xiong F Tu Y . Glymphatic system dysfunction in adult ADHD: Relationship to cognitive performance. J Affect Disord. (2025) 379:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.03.059

78

Barlattani T D’Amelio C Cavatassi A De Luca D Di Stefano R di Berardo A et al . Autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric comorbidities: a narrative review. J Psychopathol. (2023) 29:3–29. doi: 10.36148/2284-0249-N281

79

Banaschewski T Belsham B Bloch MH Ferrin M Johnson M Kustow J et al . Supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in the management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Nutr Health. (2018) 24:279. doi: 10.1177/0260106018772170

80

Ceccariglia S D’altocolle A Del Fa’ A Silvestrini A Barba M Pizzolante F et al . Increased expression of Aquaporin 4 in the rat hippocampus and cortex during trimethyltin-induced neurodegeneration. Neuroscience. (2014) 274:273–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.05.047

81

Nagai J Yu X Papouin T Cheong E Freeman MR Monk KR et al . Behaviorally consequential astrocytic regulation of neural circuits. Neuron. (2021) 109:576–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.12.008

82

Bishir M Bhat A Essa MM Ekpo O Ihunwo AO Veeraraghavan VP et al . Sleep deprivation and neurological disorders. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/5764017

83

Riedel BC Thompson PM Brinton RD . Age, APOE and sex: Triad of risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. (2016) 160:134–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.012

84

Björkhem I & Meaney S . Brain cholesterol: long secret life behind a barrier. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vasc Biol. (2004) 24:806–15. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000120374.59826.1b

85

Corder EH Saunders AM Strittmatter WJ Schmechel DE Gaskell PC Small GW et al . Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. (1993) 261:921–3. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443

86

Vandebroek A Yasui M . Regulation of AQP4 in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:1603. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051603

87

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71.

88

Lohela TJ Lilius TO Nedergaard M . The glymphatic system: implications for drugs for central nervous system diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2022) 21:763–79. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00500-9

89

Dallaspezia S Benedetti F . Chronobiologic treatments for mood disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. (2025) 206:181–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90918-1.00011-3

90

Sundman MH Liu Y Chen NK Chou Y-H . The glymphatic system as a therapeutic target: TMS-induced modulation in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. (2025) 17:1597311. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1597311

91

Murdock MH Yang CY Sun N Pao PC Blanco-Duque C Kahn MC et al . Multisensory gamma stimulation promotes glymphatic clearance of amyloid. Nature. (2024) 627:149–56. doi: 10.1038/S41586-024-07132-6;TECHMETA=14,19,45,69,91;SUBJMETA=1283,1689,2607,378,631,87;KWRD=ALZHEIMER

92

Yao D Li R Hao J Huang H Wang X Ran L et al . Melatonin alleviates depression-like behaviors and cognitive dysfunction in mice by regulating the circadian rhythm of AQP4 polarization. Trans Psychiatry. (2023) 13:310. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02614-z

93

Sun H Cao Q He X Du X Jiang X Wu T et al . Melatonin mitigates sleep restriction-induced cognitive and glymphatic dysfunction via aquaporin-4 polarization. Mol Neurobiol. (2025). doi: 10.1007/S12035-025-04992-5

94

Chen Y Guo H Sun X Wang S Zhao M Gong J et al . Melatonin regulates glymphatic function to affect cognitive deficits, behavioral issues, and blood–brain barrier damage in mice after intracerebral hemorrhage: potential links to circadian rhythms. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2025) 31:e70289. doi: 10.1111/CNS.70289

95

Liu X Hao J Yao E Cao J Zheng X Yao D et al . Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplement alleviates depression-incident cognitive dysfunction by protecting the cerebrovascular and glymphatic systems. Brain Behavior Immun. (2020) 89:357–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.022

96

Macura I Milanovic D Tesic V Major T Perovic M Adzic M et al . The impact of high-dose fish oil supplementation on mfsd2a, aqp4, and amyloid-β Expression in retinal blood vessels of 5xFAD alzheimer’s mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:9400. doi: 10.3390/ijms25179400

97

Liška K Dočkal T Houdek P Sládek M Lužná V Semenovykh K et al . Lithium affects the circadian clock in the choroid plexus – A new role for an old mechanism. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy. (2023) 159:114292. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114292

98

Lilius TO Blomqvist K Hauglund NL Liu G Stæger FF Bærentzen S et al . Dexmedetomidine enhances glymphatic brain delivery of intrathecally administered drugs. J Controlled Release. (2019) 304:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.05.005

99

Persson ND >Å. Uusalo P Nedergaard M Lohela TJ Lilius TO . Could dexmedetomidine be repurposed as a glymphatic enhancer? Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 43:1030–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.09.007

100

Liu Y Hu Q Xu S Li W Liu J Han L et al . Antidepressant effects of dexmedetomidine compared with ECT in patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. (2024) 347:437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.11.077

101

Wu X Wen G Yan L Wang Y Ren X Li G et al . Ketamine administration causes cognitive impairment by destroying the circulation function of the glymphatic system. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy. (2024) 175:116739. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116739

102

Wen G Zhan X Xu X Xia X Jiang S Ren X et al . Ketamine improves the glymphatic pathway by reducing the pyroptosis of hippocampal astrocytes in the chronic unpredictable mild stress model. Mol Neurobiol. (2023) 61:2049–62. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03669-1

103

Mazza M Losurdo A Testani E Marano G Di Nicola M Dittoni S et al . Polysomnographic findings in a cohort of chronic insomnia patients with benzodiazepine abuse. J Clin Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med. (2014) 10:35–42. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3354

104

Chen S Xu Z Guo Z Lin S Zhang H Liang Q et al . Glymphatic dysfunction associated with cortisol dysregulation in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2025) 15:265. doi: 10.1038/s41398-025-03486-1

105

Liang Q Peng B Chen S Wei H Lin S Lin X et al . Inflammation and psychomotor retardation in depression: The moderating role of glymphatic system. Brain Behav Immun. (2025) 127:387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2025.03.024

106

Ma J Zhang R Lin K Lee T . Modulation of depression through the neurobiological underpinnings of the glymphatic-rumination relationship. Available at SSRN 5392835.

107

Wu H Liu B Liu WV Wen Z Yang W Yang H et al . Glymphatic system dysfunction correlated with gut dysbiosis and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. (2025) 11:113. doi: 10.1038/s41537-025-00661-7

108

Tao Y Zhou Y Li W Ding Y Wu P Wu Z et al . Altered default mode network and glymphatic function in insomnia with depression: A multimodal MRI study. Sleep Medicine. 131. (2025) 106482. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2025.106482

109

Yang W Li Z Sun Y Matsubara T Higuchi F Kobayashi M et al . DTI ALPS in patients with major depressive disorder and its relation to white matter alteration. J Affect Disord. (2024) 337:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.025

110

Bellesi M de Vivo L Tononi G Cirelli C . Effects of sleep and wake on astrocytes: clues from molecular and ultrastructural studies. BMC Biol. (2015) 13:66. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0176-7

111

Camargos EF Nóbrega OT . Revisiting old drugs owing to the glymphatic system: A step toward unlocking the role of hypnotics in brain health. J Clin Pharmacol. (2023) 63:745–6. doi: 10.1002/JCPH.2219

112

Baraldo M . The influence of circadian rhythms on the kinetics of drugs in humans. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. (2008) 4:175–92. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.2.175

113

Zhang D Li X Li B . Glymphatic system dysfunction in central nervous system diseases and mood disorders. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:873697. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.873697

114

Zuo M Li Y Williams JP Li Y Sun L Wang R et al . Esketamine rapid antidepression combined with dexmedetomidine sleep modulation for patients with depression and insomnia. (2024). doi: 10.2139/SSRN.4797253963

115

Zou K Deng Q Zhang H Huang C . Glymphatic system: a gateway for neuroinflammation. Neural Regeneration Res. (2024) 19:2661–72. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.391312

Summary

Keywords

glymphatic system, mental disorders, diffusion tensor imaging, aquaporin-4, astrocytes, cerebrospinal fluid, extracellular fluid, sleep

Citation

Barlattani T, Cavatassi A, Bologna A, Socci V, Trebbi E, Malavolta M, Rossi A, Martiadis V, Tomasetti C, De Berardis D, Di Lorenzo G and Pacitti F (2025) Glymphatic system and psychiatric disorders: need for a new paradigm?. Front. Psychiatry 16:1642605. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1642605

Received

06 June 2025

Accepted

03 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Yanming Wang, University of Science and Technology of China, China

Reviewed by

Benedictor Alexander Nguchu, University of Science and Technology of China, China

Matthew E. Peters, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Barlattani, Cavatassi, Bologna, Socci, Trebbi, Malavolta, Rossi, Martiadis, Tomasetti, De Berardis, Di Lorenzo and Pacitti.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valentina Socci, valentina.socci@univaq.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.