- 1Department of Psychiatry, Shandong Mental Health Center, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 2Shenzhen Mental Health Center, Shenzhen Kangning Hospital, Shenzhen, China

Background: Alexithymia is closely related to problematic smartphone use (PSU) in adolescents, but its mechanism in adolescents with depression is still unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate the predictive effect of alexithymia on PSU in depressed adolescents and to examine the moderating effect of social support (family, friends, significant others) on this relationship.

Methods: A total of 2343 adolescents with depressive disorder aged 12–18 years from 14 medical institutions in China were included in this cross-sectional study. The Toronto Alexithymia Scale, Mobile Phone Addiction Index and Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale were used to evaluate the core variables. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to test the moderating effect after controlling demographic variables.

Results: Alexithymia was significantly and positively associated with PSU (r = 0.343, p < 0.01), with Difficulty in Recognizing Feelings having the strongest association (r = 0.348). Stratified regression revealed that family support (B = -0.625, p = 0.005) and friend support (B = -0.577, p = 0.013) significantly attenuated the positive predictive effect of alexithymia on PSU, whereas there was no significant moderating effect of significant others support.

Conclusion: Research shows that social support mitigates the risk of (PSU) among depressed adolescents with alexithymia, with family and friend support as key protective factors. These findings highlight the need for clinical screening and interventions targeting adolescents with alexithymia and low social support, who are at high risk for PSU. Integrating family systems therapy and friend support programs into clinical interventions may enhance emotional regulation and reduce smartphone dependence, thereby improving depressive symptoms.

1 Introduction

Smartphones have become indispensable tools for communication and information access in modern life, with their rich entertainment and social functions significantly enhancing convenience. However, adolescents’ relatively weaker self-control makes smartphones highly attractive to them, often leading to Problematic Smartphone Use (PSU) (1). Data indicates that a high percentage (93.9%) of Chinese adolescents access the internet via smartphones (2), raising concerns about excessive use. PSU refers to the excessive (in time or frequency) or inappropriate use of smartphones, characterized by the individual’s difficulty in self-control despite awareness of negative consequences. This behavior results in impairments to physical and mental health, academic performance, and daily life, manifesting as withdrawal symptoms akin to addiction (3–5). Although there is ongoing debate within academia about classifying PSU as a mental disorder (6–8), it shares similarities with internet addiction (9). Therefore, this study draws upon the “internet addiction” research framework, focusing on the smartphone use behavior itself without directly associating it with a mental disorder diagnosis.

The negative impact of PSU is particularly pronounced among adolescents with depressive disorders. Due to their immature psychosocial development and personality formation, adolescents are more vulnerable to adverse psychological consequences from PSU (10). Research demonstrates that PSU may exacerbate symptoms of anxiety and depression (11), and even increase the risk of self-harm or suicide (12, 13). It is also associated with attention deficits, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (14), as well as academic impairment (15). At the family level, excessive smartphone use correlates with increased parent-child conflict and decreased family cohesion (16). Regarding physical health, PSU may lead to sleep disturbances and vision problems (17, 18). Furthermore, excessive social media use among adolescents has been confirmed to be associated with mood disorders (19). Additionally, the phenomenon of social media intervention has been explored, with evidence suggesting that targeted interventions can mitigate some of the negative impacts of excessive use on adolescents’ mental health (20). Moreover, adolescent anhedonia—the inability to derive pleasure from normally enjoyable activities—has been identified as a significant factor that increases susceptibility to PSU, as adolescents with this condition may turn to the Internet for instant gratification and emotional escape (21). Similarly, the relationship between loneliness, Internet use, and depression has been widely studied, with findings indicating that excessive online engagement, especially on social media, contributes to feelings of isolation and worsens depressive symptoms (22).Consequently, PSU likely exacerbates the challenges faced by adolescents with depressive disorders, necessitating in-depth investigation into its underlying psychological mechanisms.

Alexithymia, regarded as a personality trait, involves difficulties in identifying, describing, and regulating emotions (23). This includes challenges in distinguishing emotions from physical sensations, limitations in verbalizing emotional experiences, and restricted imaginative thought (24, 25). For adolescents, alexithymia impedes the expression and understanding of negative emotions, potentially leading to the accumulation and worsening of depressive symptoms, prolonged episodes, and increased relapse risk (26). It also elevates the likelihood of suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury (27, 28). Studies have confirmed a significant correlation between the severity of alexithymia and PSU, identifying it as a risk factor for overuse (29). Social support, defined as the emotional and material assistance obtained from social networks (30), primarily refers to informal support from family, relatives, and friends in this study. Adolescents perceiving lower levels of social support are more likely to exhibit problematic use (31), possibly because they attempt to seek emotional fulfillment and social connection through their phones. Multiple studies consistently find that inadequate social support exacerbates negative emotions and loneliness, weakens self-regulation and self-control, and increases the risk of internet addiction (32, 33). A meta-analysis specifically focusing on Chinese adolescents (incorporating 92 studies with 59,716 participants) also clearly demonstrates a significant negative correlation between mobile phone addiction and social support (34). Therefore, social support, as a resource for coping with stress, may play a crucial role in mitigating the negative effects of alexithymia and PSU among adolescents with depressive disorders.

Although existing research indicates an association between alexithymia and PSU, the moderating role of social support in this relationship has not been systematically studied among adolescents with depressive disorders. Given the negative consequences associated with both alexithymia and PSU, it is crucial to clarify the psychological mechanisms underlying their interplay in order to understand their interaction and develop interventions aimed at reducing PSU. The primary aim of this study was to examine whether alexithymia predicts PSU, while the secondary aim was to explore whether social support moderates this relationship. This research aims to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding the factors influencing the mental health of adolescents with depressive disorders and to inform the development of relevant interventions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and population

The present study was of a cross-sectional study. Participants were adolescents diagnosed with depressive disorders. These individuals were recruited from the psychiatric outpatient departments of 14 mental health institutions or general hospitals across nine provinces in China. The study recruitment period commenced in December 2020 and ended in December 2021. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) Aged 12–18 years; (ii) Diagnosed with a depressive disorder (MDD, BD-D, or depressive state) according to DSM-5 criteria by senior psychiatrists; (iii) Adequate cognitive ability to complete the research questionnaire; (iv) Written informed consent was obtained from both the participant and their legal guardian. Exclusion criteria included: (i) Diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorders or intellectual disability; (ii) Presence of suicidal or homicidal ideation requiring immediate intervention; (iii) Active psychotic symptoms, such as schizophrenia or a manic episode. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Kangning Hospital (IRB: 2020-k021-02). Prior to the commencement of the survey, parents of each adolescent provided written informed consent for their children to take part in this study. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional research (35) (see supplementary material).

2.2 Assessment of mobile phone addiction index (Chinese version)

The degree of problematic smartphone use was assessed using the Chinese version of the Mobile Phone Addiction Index (MPAI) (36). This scale consists of 17 self-reported items designed to evaluate smartphone usage, covering four subscales: uncontrollability, withdrawal, escape, and inefficiency. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = frequently), with a total score ranging from 17 to 85. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of smartphone dependence, and a score of ≥51 is defined as problematic smartphone use. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.80, indicating good reliability.

2.3 Assessment of alexithymia

This study utilized the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) to assess alexithymia (37). The 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) was used to assess the severity of alexithymia. The scale comprises three subdimensions: Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF, 7 items), Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF, 5 items), and Externally-Oriented Thinking (EOT, 8 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), resulting in a total score between 20 and 100. Higher scores indicate greater levels of alexithymia. According to established cut-off criteria, scores of 51 or below are classified as “no alexithymia”, scores between 52 and 60 as “possible alexithymia”, and scores of 61 or above as “alexithymia”. In the present study, the TAS-20 demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

2.4 Assessment of social support

This study employed the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to evaluate participants’ perceived social support (38). The scale consists of 12 self-reported items designed to measure the extent of social support received from family, friends, and significant others. An example item is: “There is a special person who is always around when I need them.” Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The scores are used to calculate three subscale scores (family, friends, and significant others) and an overall score. The subscale and total scores are expressed as the average of the respective items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived social support. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the MSPSS was 0.84, indicating strong internal consistency.

2.5 Covariates

To control for potential confounding factors, the following covariates were included in the analyses: demographic characteristics (gender, age, only-child status, and residential area), parental marital status, parental highest level of education, quality of the parent–child relationship, and history of self-injurious behavior.

2.6 Data analysis

The collected data underwent preliminary screening to remove samples with obvious outliers. Normality tests were performed for all variables. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to calculate the means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum values for alexithymia, problematic smartphone use, and social support. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to analyze the pairwise correlations among alexithymia, problematic smartphone use, and social support. To test the moderating role of social support in the relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use, hierarchical regression analysis was employed. The analysis followed these steps: (1) Enter control variables (e.g., age, gender, family structure) into the model. (2) Add the main effects of alexithymia and social support (family support, friend support, and significant other support). (3) Introduce the interaction term between alexithymia and social support to examine the moderating effect of social support.

A simple slope analysis was conducted to further explore the strength of the relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use at different levels of social support. An interaction plot was created to visually illustrate the moderating effect of social support. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set at 0.05. Results with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics of the sample

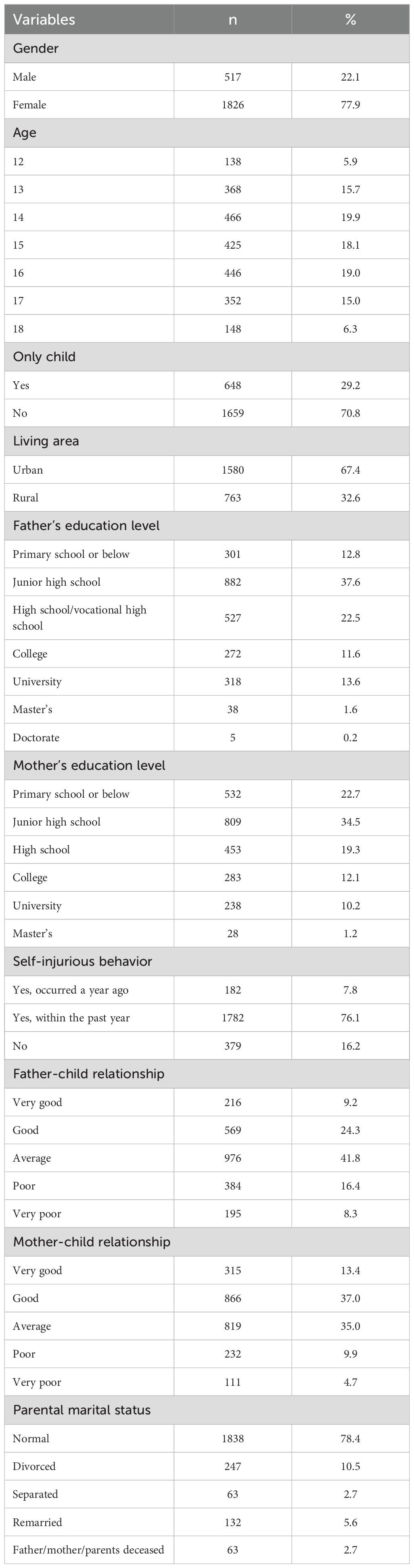

A total of 2,343 adolescents completed the survey. Participants ranged in age from 12 to 18 years (M = 14.99, SD = 1.65), with 517 males (22.1%) and 1,826 females (77.9%). Among them, 684 adolescents (29.2%) were only children, while 1,659 (70.8%) had siblings. Additionally, 67.4% of the participants were from urban areas, and 32.6% were from rural areas. Detailed participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

3.2 Descriptive statistics and correlations among main variables

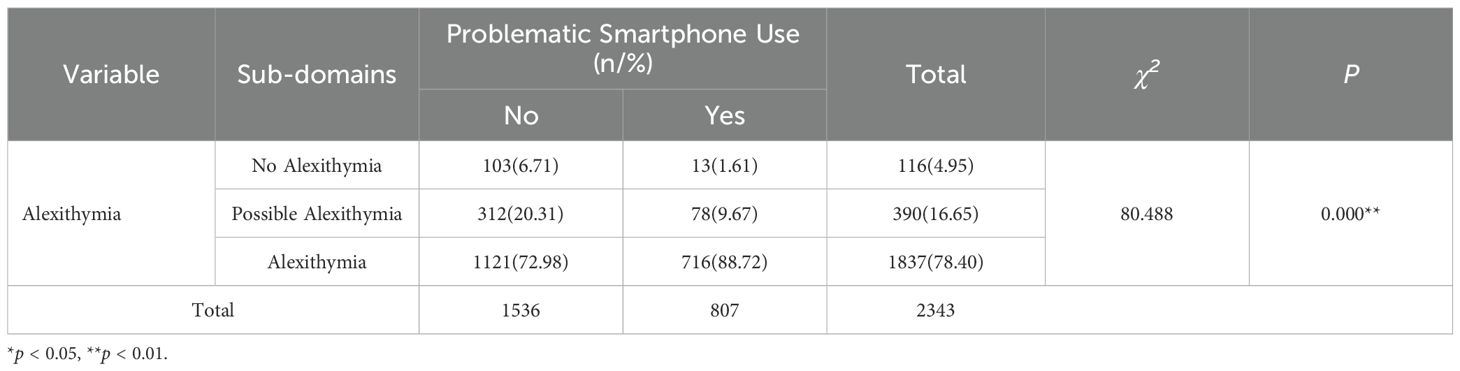

Descriptive statistics and correlations for measured variables are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Using the chi-square test (χ²), the relationship between different levels of alexithymia and problematic smartphone use among adolescents was examined. From the Table 2, it can be observed that there is a significant difference in the incidence of problematic smartphone use among adolescents with varying degrees of alexithymia, with a significance level of 0.01 (χ² = 80.488, p = 0.000 < 0.01). This suggests that alexithymia is significantly associated with problematic smartphone use, particularly among adolescents with alexithymia, where the rate of problematic smartphone use is notably higher. This indicates that alexithymia may be a risk factor for problematic smartphone use.

Table 2. Correlation between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use in adolescents with depression.

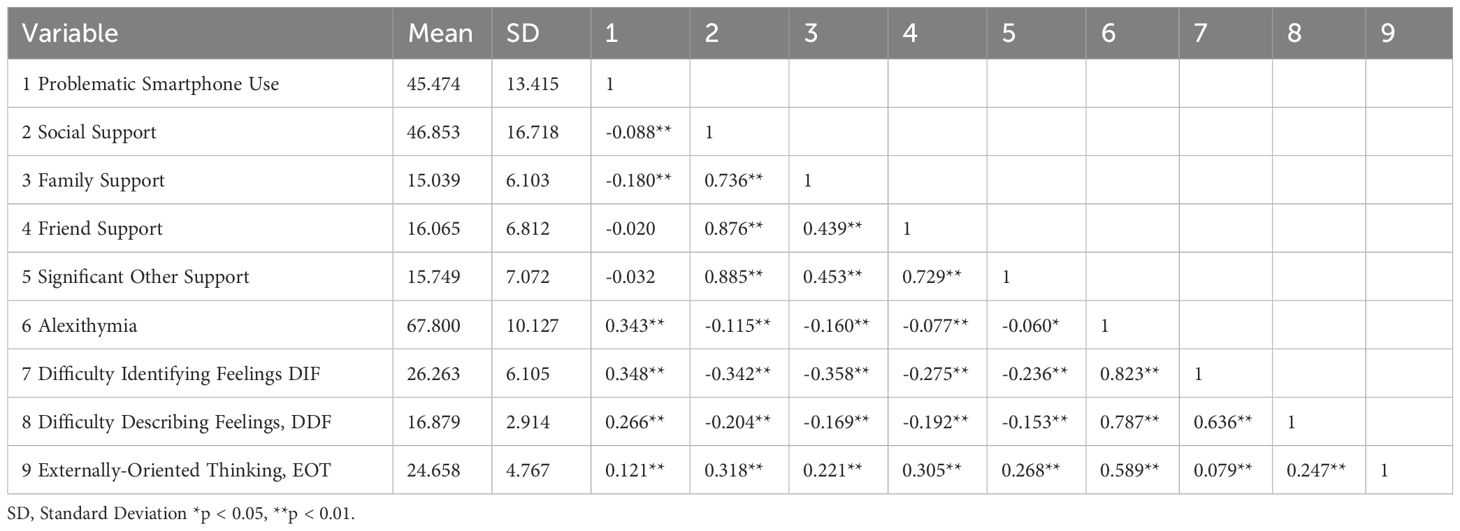

Table 3. Pearson correlation coefficients between excessive problematic smartphone use, alexithymia, and social support.

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients among problematic smartphone use (PSU), alexithymia, and perceived social support. PSU was significantly and positively correlated with overall alexithymia (r = 0.343, p < 0.01), indicating that higher levels of alexithymia are associated with more severe problematic smartphone use. Among the subdimensions of alexithymia, difficulty identifying feelings (DIF) showed the strongest correlation with PSU (r = 0.348, p < 0.01), followed by difficulty describing feelings (DDF; r = 0.266, p < 0.01), and externally-oriented thinking (EOT; r = 0.121, p < 0.01).Perceived social support was negatively correlated with PSU (r = -0.088, p < 0.01). Among the three sources of support, only family support demonstrated a significant negative correlation with PSU (r = -0.180, p < 0.01), whereas correlations with friend support and significant other support were nonsignificant.

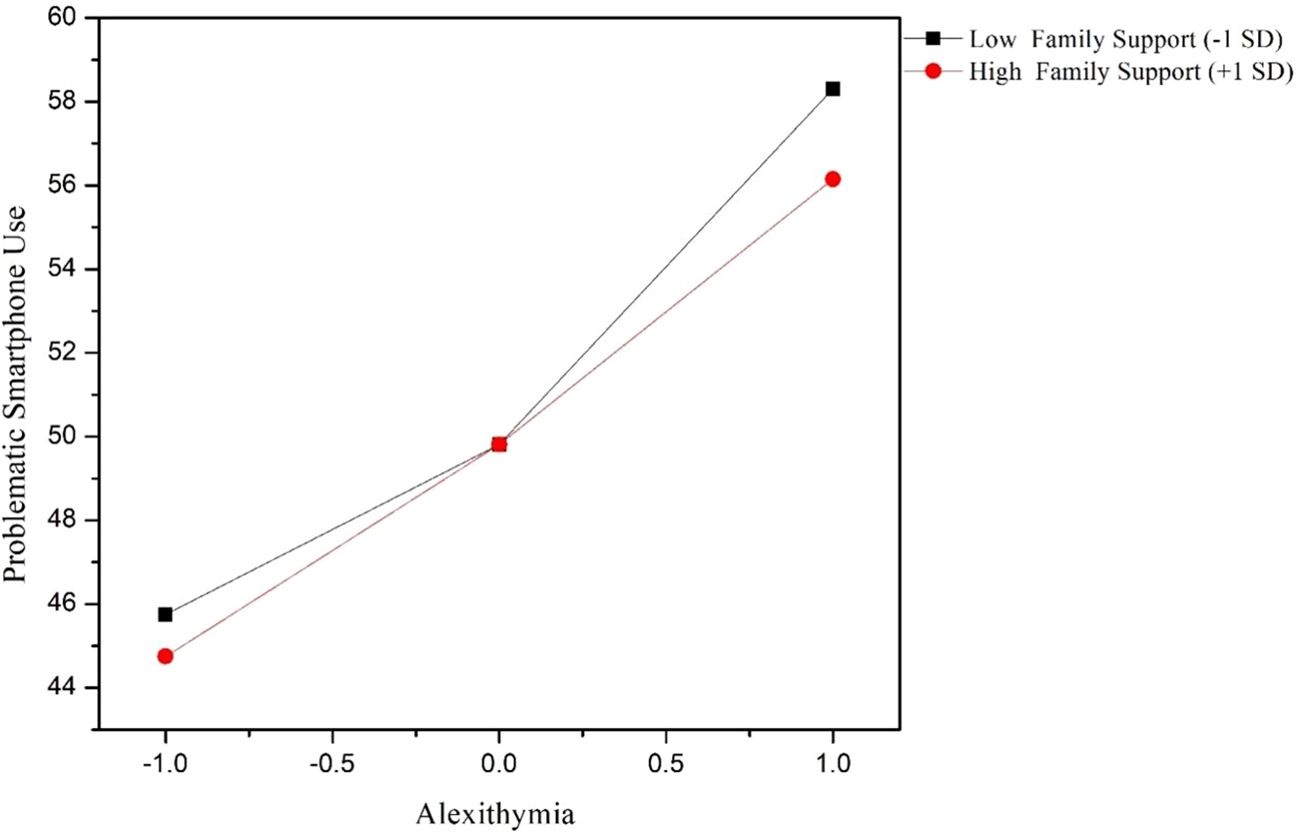

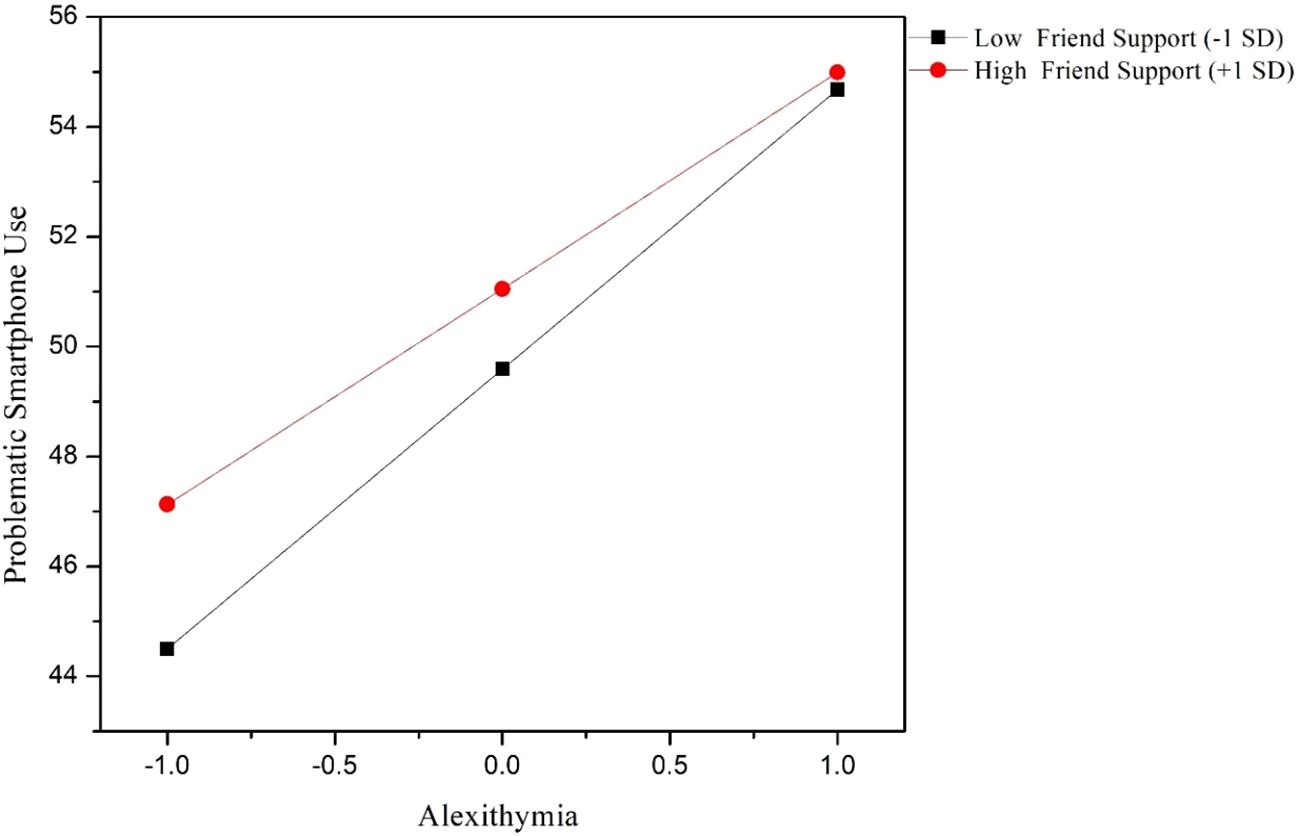

3.3 Regression analysis and moderating effects of social support

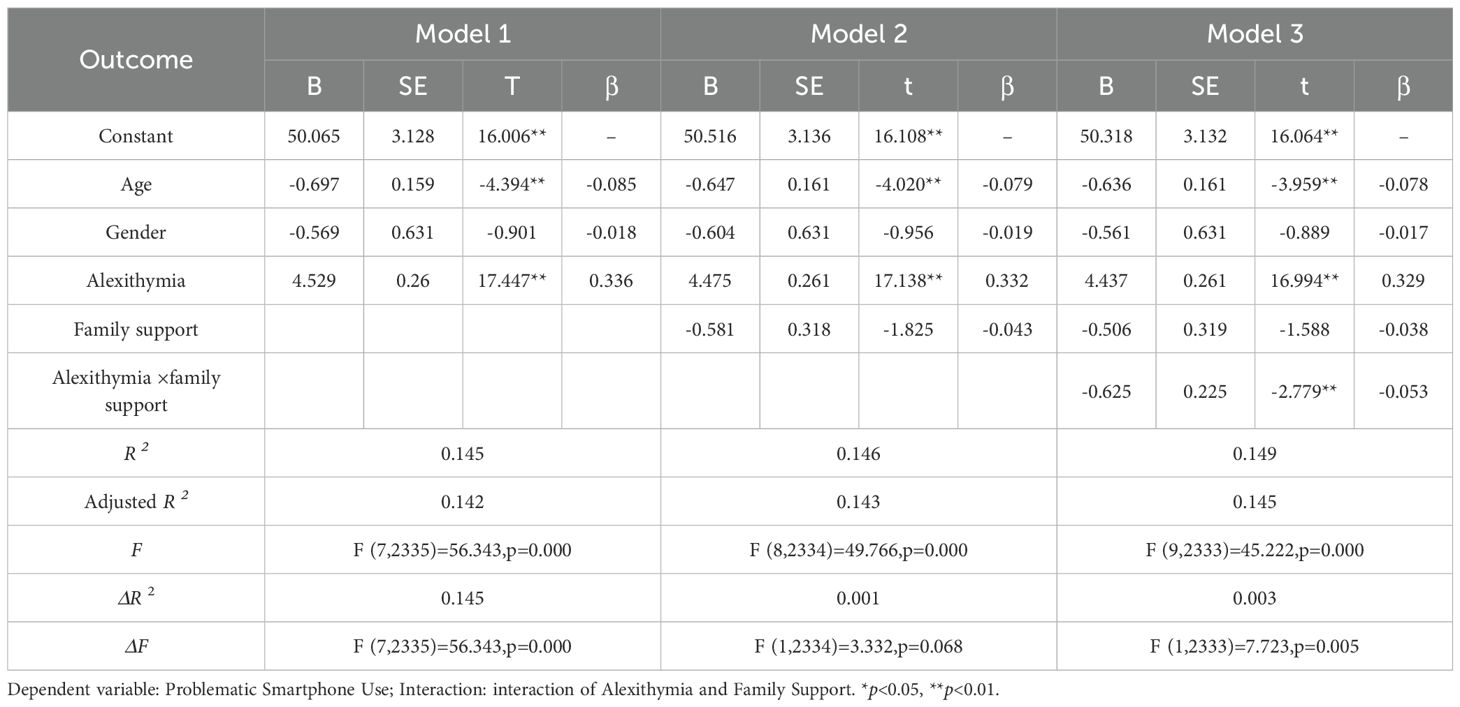

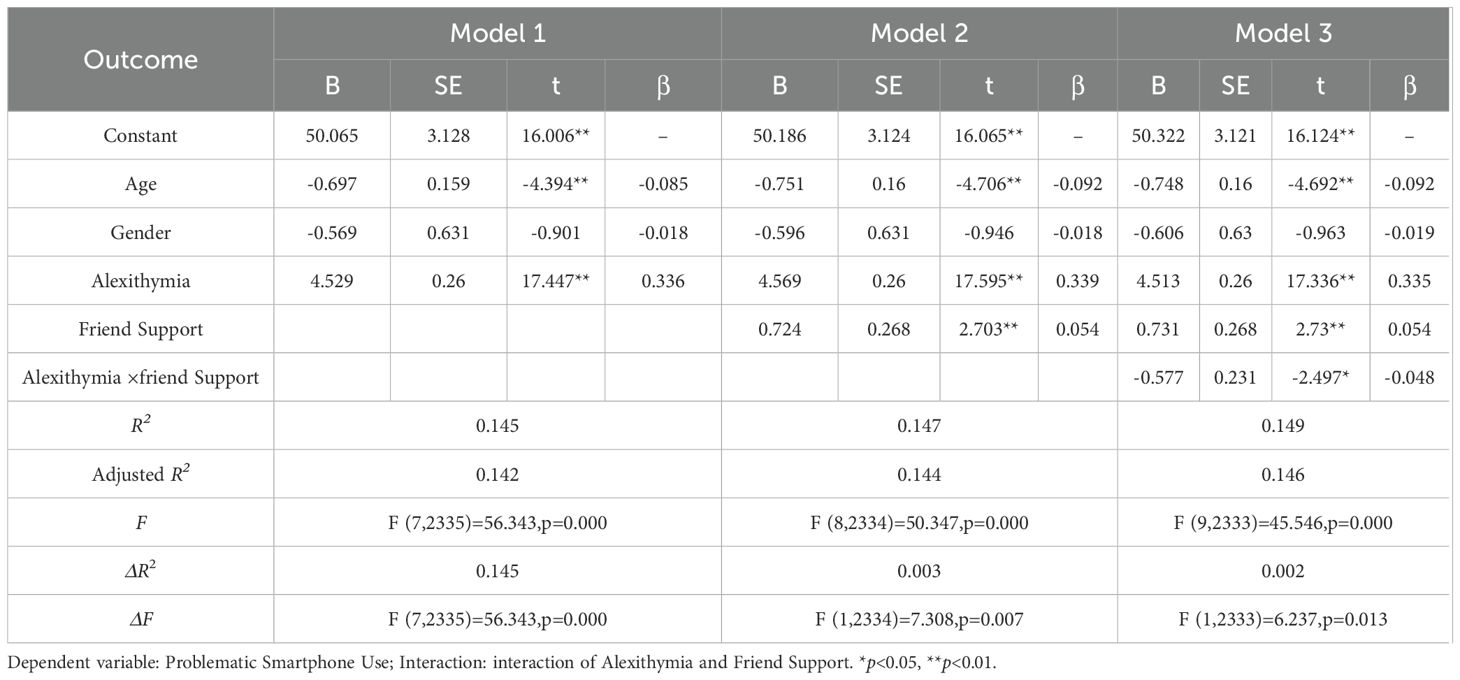

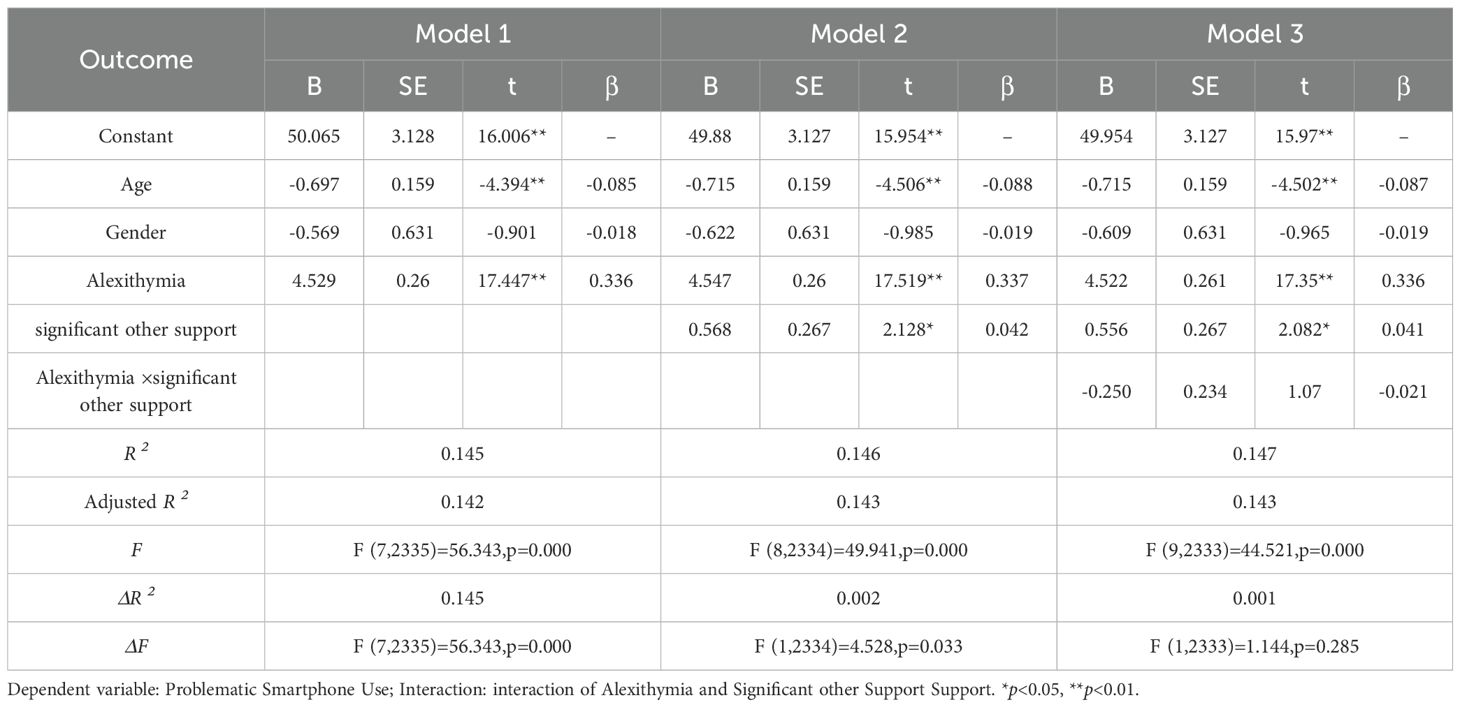

To further examine whether different types of social support moderated the association between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted separately for family support, friend support, and significant other support. Age and gender were controlled for in all models. In the family support model, alexithymia was found to be a significant positive predictor of problematic smartphone use (B = 4.437, p < 0.001). The interaction term between alexithymia and family support was significant and negative (B = -0.625, p = 0.005), indicating that higher levels of family support attenuated the positive relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use. In the friend support model, alexithymia again positively predicted problematic smartphone use (B = 4.513, p < 0.001). Friend support exhibited a significant negative association with problematic smartphone use (B = 0.724, p = 0.007). Moreover, the interaction between alexithymia and friend support was significant (B = -0.577, p = 0.013), suggesting that higher friend support weakened the association between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use. In contrast, in the significant other support model, although significant other support independently predicted lower levels of problematic smartphone use (B = 0.568, p = 0.033), the interaction between alexithymia and significant other support was not statistically significant (B = -0.250, p = 0.285). This indicates that significant other support did not moderate the relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use. Detailed information can be found in Tables 4–6 and Figures 1, 2.

Table 4. Moderation effect analysis of alexithymia and family support on problematic smartphone use in adolescents with depression.

Table 5. Moderation effect analysis of alexithymia and friend support on problematic smartphone use in adolescents with depression.

Table 6. Moderation effect analysis of alexithymia and significant other support on problematic smartphone use in adolescents with depression.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the impact of alexithymia on problematic smartphone use among depressed adolescents and the buffering role of social support in this relationship. The study included 2,343 adolescents recruited from 14 mental health institutions or psychiatric outpatient departments in general hospitals across nine provinces in China. The results and discussion are as follows:

4.1 The role of alexithymia in predicting problematic smartphone use

Consistent with our hypotheses, alexithymia was a significant positive predictor of PSU among adolescents with depressive disorders. This finding aligns with prior evidence indicating that alexithymia—characterized by difficulties in identifying and describing emotions and an externally oriented cognitive style—predisposes individuals to maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, including problematic technology use (39, 40). Specifically, our results revealed that among the alexithymia dimensions, and DIF demonstrated the strongest correlation with PSU, supporting previous research that this component is particularly detrimental to emotional processing and regulation (41).

Theoretically, adolescents with alexithymia may rely on smartphones as a compensatory mechanism to cope with distress, avoid aversive emotional states, and seek immediate gratification through digital interactions (42). Recent theoretical models provide additional insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship. According to the Compensatory Internet Use Theory (CIUT), individuals with impaired emotion regulation capacities—such as those with alexithymia—are more likely to engage in excessive digital behaviors as a maladaptive strategy to manage negative affect and unmet psychological needs. Given that adolescents with alexithymia struggle to process and verbalize emotions, smartphones offer an immediate, controllable, and socially acceptable outlet for distraction and emotion avoidance (43). Moreover, from the perspective of the I-PACE model (44),core deficits in emotional competence (such as DIF) contribute to the development and maintenance of problematic technology use through reinforcing maladaptive affective responses and promoting habitual engagement with digital media. Specifically, adolescents with alexithymia may experience difficulties interrupting negative affective cycles, leading to repetitive smartphone checking as a form of short-term emotional relief (45). Over time, such compensatory behavior can evolve into compulsive patterns of use, consistent with the high PSU prevalence observed in our sample. A recent study by Lyvers et al. (2022) further confirmed that alexithymia significantly predicts digital overuse across various platforms, including smartphones and social media, particularly in youth populations (46). Moreover, the extremely high prevalence of PSU in adolescents with moderate to high levels of alexithymia observed in our sample (88.7%) underscores the clinical relevance of this association. These findings suggest that alexithymia should be routinely assessed when evaluating risk factors for PSU in adolescents with mood disorders. Furthermore, data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021), which may have intensified social isolation, increased emotional distress, and elevated PSU levels. These contextual influences should be considered when interpreting the results to test the universality of these effects and explore potential cultural moderators (47–49).

4.2 Social support as a protective factor: differential effects across sources

One of the key contributions of this study lies in our examination of the moderating role of different sources of social support. Overall, perceived social support was negatively associated with PSU, echoing findings from prior studies (50). However, the protective effects varied significantly by source.

4.2.1 Family support: a robust buffering effect

Family support not only exerted a direct negative association with PSU but also significantly moderated the effect of alexithymia on PSU, suggesting that emotionally supportive family environments may buffer adolescents with poor emotional competence from developing maladaptive digital behaviors. This finding is consistent with family systems theory, which emphasizes the family’s central role in emotion socialization, co-regulation, and internal working model development during adolescence (51). From the lens of attachment theory, adolescents with high family support are more likely to develop secure attachment representations, which in turn foster confidence in expressing emotions and seeking relational support rather than resorting to technological escape (52). Secure family bonds provide a “safe base” for emotion exploration and distress regulation, which may offset the emotional dysregulation associated with alexithymia.

In addition, the emotion socialization model (53), suggests that parents’ emotional responsiveness and validation contribute to the development of children’s emotional awareness and regulation capacity. In families that promote open emotional expression and model adaptive coping, adolescents—even those with trait-level difficulties like alexithymia—may learn to better identify and manage their affect, thereby reducing the need for smartphone-based avoidance strategies (54).

Furthermore, high-quality family support may reduce negative appraisals of stressful situations and promote a sense of belonging and self-worth, which are protective against compulsive smartphone checking (55). In contrast, emotionally disengaged or invalidating family environments may fail to provide the necessary scaffolding, increasing reliance on solitary, screen-based coping methods (56).

Our findings support the view that family support operates not only as an external buffer but also as a developmental context that shapes internal emotional coping schemas. Thus, in adolescents with alexithymia, strong family relationships may serve as a compensatory resilience factor that reduces the risk of developing PSU.

4.2.2 Friend support: complex and context-dependent effects

Friend support also demonstrated a moderating effect on the alexithymia–PSU relationship, although its direct association with PSU was not significant, highlighting the complex and context-dependent nature of peer influences on adolescent digital behaviors.

From a developmental perspective, adolescence is a period when peer relationships assume increasing importance in emotional and social development (57). According to the emotional co-regulation framework (58), supportive friends can serve as vital co-regulators of affect, providing opportunities for emotional validation, perspective-taking, and adaptive coping modeling. For adolescents with alexithymia, who struggle with internal emotional processing, emotionally attuned peer interactions may offer external scaffolding for emotion regulation, thereby reducing reliance on smartphone-based coping strategies (59).

Moreover, friend support can foster a sense of social connectedness and belonging, which is negatively associated with maladaptive digital engagement (60). In this way, positive friend relationships can serve as an alternative source of emotional gratification, reducing the compensatory appeal of smartphones (32).

However, the effect of friend support is likely context-dependent, as peer groups also constitute a potential risk factor for problematic technology use. According to peer contagion theory (61), adolescents often model and reinforce each other’s behaviors. In peer contexts where excessive smartphone use is normalized or even valorized, higher friend support may inadvertently facilitate PSU (62). Additionally, adolescents with alexithymia may gravitate toward online-based friendships, which may lack the protective qualities of in-person peer interactions (Marino et al., 2020), further complicating the role of friend support.

Our findings suggest that the quality and nature of peer relationships are critical in determining whether friend support functions as a protective or risk factor. Interventions targeting adolescent PSU should therefore focus not only on enhancing friend support quantity but also on promoting high-quality, emotionally supportive, and offline peer relationships.

4.2.3 Significant other support: no buffering effect observed

Contrary to expectations, support from significant others did not exhibit a significant moderating effect on the relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use (PSU). This null finding may reflect the unique nature of “significant other” relationships in adolescents with depressive disorders and high alexithymia.

First, the ambiguous and heterogeneous definition of “significant others” in self-report measures—ranging from teachers and coaches to romantic partners or mentors—may contribute to variable psychological relevance. Unlike family and close friends, whose roles are often developmentally primary and emotionally intimate, significant others may occupy peripheral or less consistent positions in the adolescent’s emotional ecology (63). Second, individuals with alexithymia—by definition—struggle with emotional expressiveness, empathy reception, and interpersonal attunement (64). These deficits may impede the ability to accurately perceive or benefit from emotionally nuanced support that significant others typically offer (65). Compared with family members who provide instrumental and unconditional scaffolding, or peers who share symmetrical emotional contexts, significant others may not offer the type of emotionally accessible support that is useful for alexithymic individuals (66). Third, the trust calibration and affective reliance required to benefit from significant other support may be particularly challenging for adolescents with high interpersonal mistrust or emotional constriction—both of which are common among alexithymic and depressive populations (67). As such, the protective potential of these relationships may remain latent unless emotional closeness and perceived responsiveness reach a sufficient threshold. Finally, there is increasing evidence that support perceived as inauthentic or overly distant may not only fail to buffer psychological distress, but may also lead to reactance or disengagement, especially in emotionally dysregulated adolescents (67). For alexithymic individuals, emotional incongruence in significant other interactions may even exacerbate distress and contribute to increased smartphone dependency as a compensatory regulation strategy. Lastly, and importantly, in Chinese culture, family and friends typically play a more significant role in providing emotional support than ‘significant others’ such as romantic partners or mentors, especially during adolescence when these relationships are not yet fully stabilized. Therefore, the lack of a moderating effect of ‘significant other support’ on the relationship between alexithymia and PSU may reflect cultural differences in the roles of emotional support. Overall, these findings suggest that the buffering role of support is highly dependent on the source’s emotional proximity and relational attunement, and that in adolescents with alexithymia, family and close friends may play a more critical protective role than less emotionally embedded figures.

4.3 Clinical and theoretical implications

These findings have important implications for both clinical practice and future research. First, they emphasize the need for a comprehensive assessment of alexithymia in adolescents with depressive disorders who exhibit problematic smartphone use (PSU) behaviors, especially across different cultural contexts. Given the strong predictive role of alexithymia, particularly the Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF) component, interventions aimed at enhancing emotional awareness and expression (e.g., affect labeling, mindfulness-based emotion regulation training) may be especially effective. These interventions can be adjusted to fit various cultural contexts, ensuring they meet the unique emotional and social needs of adolescents in different regions (e.g., family-centered versus peer-centered cultures).Second, our results highlight the protective role of family support, with friend support also playing a significant role to a lesser extent. Specifically, family-based interventions, such as family systems therapy, including multigenerational family sessions and emotion coaching skills training for parents, can enhance parent-child emotional communication and support (68, 69).These interventions can be adjusted to cultural norms to fit the cultural differences in various family structures. Regarding peer support, social skills training and peer support group interventions have been shown to be effective (70, 71), and cultural differences, particularly in how adolescents form and maintain friendships, should be considered. These interventions could be integrated into treatment plans for adolescents at high risk for alexithymia and PSU, especially those from family structures that emphasize peer support over family support. Finally, these findings contribute to refining theoretical models of PSU by emphasizing the interaction between individual emotional traits (e.g., alexithymia) and interpersonal resources (e.g., social support). Research suggests that future theoretical models should account for the differential role of social support across various cultural and familial backgrounds, and how these resources regulate the emotion regulation processes that underpin PSU. Future studies should explore the cross-cultural differences between alexithymia, PSU, and social support, and examine how these findings can inform interventions globally.

5 Limitations

Despite the theoretical contributions and practical implications of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged: First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to elucidate the causal pathways between alexithymia and PSU, and could further conduct intervention experiments to evaluate the actual efficacy of enhancing social support in improving adolescents’ smartphone use behaviors. Second, PSU was assessed primarily through self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to social desirability bias and memory distortions. Future research should incorporate objective usage metrics (e.g., smartphone tracking data, application usage logs) to enhance the validity and ecological accuracy of the findings. Third, although the study employed a large, multi-center clinical sample, participants were clinically diagnosed adolescents with depressive disorders. Therefore, caution is warranted when generalizing the findings to non-clinical or community youth populations. Future studies should replicate and extend these findings in more diverse samples. Fourth, the measurement of PSU in this study was relatively global and did not differentiate between specific usage types (e.g., social media, gaming, short video platforms) or usage patterns (e.g., frequency, purpose). Future research should adopt more fine-grained, context-sensitive assessment methods, such as diary techniques and digital behavior tracking, to elucidate distinct behavioral pathways and identify more precise intervention targets. In addition, cultural factors specific to the Chinese adolescent context may have shaped the observed associations. Cross-cultural comparative studies are needed to test the universality of these effects. In addition, Data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021), a period that may have intensified adolescents’ feelings of isolation and emotional distress, thereby affecting the patterns of PSU and social support. This contextual factor should be considered when interpreting the results. Finally, the unbalanced gender distribution in our sample, with females comprising 77.9%, may limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly regarding gender-specific behaviors related to depression and smartphone use. This disproportionate representation likely reflects the higher female participation in mental health research, as females generally exhibit greater help-seeking behaviors in clinical settings. However, it is important to note that selection bias cannot be ruled out, especially if certain institutions or regions had a higher proportion of female participants. Therefore, future research should strive for a more balanced gender distribution in sample recruitment to enhance the external validity of the findings. Additionally, future studies should explore the potential moderating effects of other factors (e.g., attachment style, emotion regulation strategies) that may interact with alexithymia and social support in predicting PSU, thereby enriching existing theoretical models and guiding the development of more tailored intervention strategies.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides robust evidence that alexithymia significantly contributes to PSU in adolescents with depressive disorders and that family and friend support can buffer this risk. These findings underscore the importance of targeting both individual emotional vulnerabilities and social contextual resources in interventions aimed at reducing PSU in this high-risk population.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

This study has approved and reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Kangning Hospital and Shandong Mental Health Center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology. YW: Methodology, Writing – original draft. FS: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. YZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. AY: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Shandong Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Plan Project (Grant No.: 202103090868).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Li L, Xu D-D, Chai J-X, Wang D, Li L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of Internet addiction disorder in Chinese university students: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:610–23. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.53

2. Xu D-D, Lok K-I, Liu H-Z, Cao X-L, An F-R, Hall BJ, et al. Internet addiction among adolescents in Macau and mainland China: prevalence, demographics and quality of life. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:16222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73023-1

3. Huang S, Lai X, Xue Y, Zhang C, and Wang Y. A network analysis of problematic smartphone use symptoms in a student sample. J Behav Addict. (2020) 9:1032–43. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00098

4. Rozgonjuk D, Levine JC, Hall BJ, and Elhai JD. The association between problematic smartphone use, depression and anxiety symptom severity, and objectively measured smartphone use over one week. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 87:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.019

5. Su S, Cousijn J, Molenaar D, Freichel R, Larsen H, and Wiers RW. From everyday life to measurable problematic smartphone use: The development and validation of the Smartphone Use Problems Identification Questionnaire (SUPIQ). J Behav Addict. (2024) 13:506–24. doi: 10.1556/2006.2024.00010

6. Yen J-Y, Higuchi S, Lin P-Y, Lin P-C, Chou W-P, and Ko C-H. Functional impairment, insight, and comparison between criteria for gaming disorder in the International Classification of Diseases, 11 Edition and internet gaming disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. J Behav Addict. (2022) 11:1012–23. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00079

7. Wang X, Liu Y, Chu HK-C, Wong SY-S, and Yang X. Relationships of internet gaming engagement, history, and maladaptive cognitions and adolescent internet gaming disorder: A cross-sectional study. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0290955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290955

8. Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez-Fernandez O, Kuss DJ, and Griffiths MD. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr Addict Rep. (2015) 2:156–62. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

9. Wu Y-L, Lin S-H, and Lin Y-H. Two-dimensional taxonomy of internet addiction and assessment of smartphone addiction with diagnostic criteria and mobile apps. J Behav Addict. (2021) 9:928–33. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00074

10. Meng H, Cao H, Hao R, Zhou N, Liang Y, Wu L, et al. Smartphone use motivation and problematic smartphone use in a national representative sample of Chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of smartphone use time for various activities. J Behav Addict. (2020) 9:163–74. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00004

11. Sunday OJ, Adesope OO, and Maarhuis PL. The effects of smartphone addiction on learning: A meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav Rep. (2021) 4:100114. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100114

12. Čuš A, Edbrooke-Childs J, Ohmann S, Plener PL, and Akkaya-Kalayci T. Smartphone apps are cool, but do they help me?”: A qualitative interview study of adolescents’ Perspectives on using smartphone interventions to manage nonsuicidal self-injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3289. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063289

13. Shinetsetseg O, Jung YH, Park YS, Park E-C, and Jang S-Y. Association between smartphone addiction and suicide. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:11600. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811600

14. Kim S-G, Park J, Kim H-T, Pan Z, Lee Y, and McIntyre RS. The relationship between smartphone addiction and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity in South Korean adolescents. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2019) 18:1. doi: 10.1186/s12991-019-0224-8

15. Seo DG, Park Y, Kim MK, and Park J. Mobile phone dependency and its impacts on adolescents’ social and academic behaviors. Comput Hum Behav. (2016) 63:282–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.026

16. Lin S, Yu C, Chen J, Sheng J, Hu Y, and Zhong L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8197. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218197

17. Kheirinejad S, Visuri A, Ferreira D, and Hosio S. Leave your smartphone out of bed”: quantitative analysis of smartphone use effect on sleep quality. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. (2023) 27:447–66. doi: 10.1007/s00779-022-01694-w

18. Wang J, Li M, Zhu D, and Cao Y. Smartphone overuse and visual impairment in children and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e21923. doi: 10.2196/21923

19. Alonzo R, Hussain J, Stranges S, and Anderson KK. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2021) 56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

20. Colder Carras M, Aljuboori D, Shi J, Date M, Karkoub F, García Ortiz K, et al. Prevention and health promotion interventions for young people in the context of digital well-being: rapid systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2024) 26:e59968. doi: 10.2196/59968

21. Zhao Y, Qu D, Chen S, and Chi X. Network analysis of internet addiction and depression among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Comput Hum Behav. (2023) 138:107424. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107424

22. Ivie EJ, Pettitt A, Moses LJ, and Allen NB. A meta-analysis of the association between adolescent social media use and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.014

23. Preece DA, Mehta A, Petrova K, Sikka P, Bjureberg J, Chen W, et al. The Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire-Short Form (PAQ-S): A 6-item measure of alexithymia. J Affect Disord. (2023) 325:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.036

24. Iskric A, Ceniti AK, Bergmans Y, McInerney S, and Rizvi SJ. Alexithymia and self-harm: A review of nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112920. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112920

25. Gaggero G, Bonassi A, Dellantonio S, Pastore L, Aryadoust V, and Esposito G. A scientometric review of alexithymia: mapping thematic and disciplinary shifts in half a century of research. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:611489. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.611489

26. Visted E, Sørensen L, Vøllestad J, Osnes B, Svendsen JL, Jentschke S, et al. The association between juvenile onset of depression and emotion regulation difficulties. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:2262. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02262

27. He H, Hong L, Jin W, Xu Y, Kang W, Liu J, et al. Heterogeneity of non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents with depression: latent class analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23:301. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04808-7

28. Hemming L, Taylor P, Haddock G, Shaw J, and Pratt D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between alexithymia and suicide ideation and behaviour. J Affect Disord. (2019) 254:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.013

29. Jin X, Jiang Q, Xiong W, and Zhao W. Effects of use motivations and alexithymia on smartphone addiction: mediating role of insecure attachment. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1227931. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1227931

30. Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. (2011) 52:145–61. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592

31. Nowak M, Rachubińska K, Starczewska M, Kupcewicz E, Szylińska A, Cymbaluk-Płoska A, et al. Correlations between problematic mobile phone use and depressiveness and daytime sleepiness, as well as perceived social support in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:13549. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013549

32. Ihm J. Social implications of children’s smartphone addiction: The role of support networks and social engagement. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:473–81. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.48

33. Arslan G. Social exclusion, social support and psychological wellbeing at school: A study of mediation and moderation effect. Child Ind Res. (2018) 11:897–918. doi: 10.1007/s12187-017-9451-1

34. Wan X, Huang H, Jia R, Liang D, Lu G, and Chen C. Association between mobile phone addiction and social support among mainland Chinese teenagers: A meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:911560. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.911560

35. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 147:573–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010

36. Xiao T, Jiao C, Yao J, Yang L, Zhang Y, Liu S, et al. Effects of basketball and baduanjin exercise interventions on problematic smartphone use and mental health among college students: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2021) 2021:8880716. doi: 10.1155/2021/8880716

37. Monaco S, Massari MG, Renzi A, and Di Trani M. COVID-19 post-traumatic stress disorder: the role of ACEs, alexithymia, and attachment in the Italian population. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2024) 28:2615–24. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202403_35767

38. Stark L, Robinson MV, Seff I, Hassan W, and Allaf C. SALaMA study protocol: a mixed methods study to explore mental health and psychosocial support for conflict-affected youth in Detroit, Michigan. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:38. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8155-5

39. Mahapatra A and Sharma P. Association of Internet addiction and alexithymia - A scoping review. Addict Behav. (2018) 81:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.004

40. Lyvers M, Ryan N, and Thorberg FA. Alexithymia, negative moods, and fears of positive emotions. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:13507–16. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02555-0

41. Zhang Y, Zhong Y-L, Luo J, He J-L, Lin C, Zauszniewski JA, et al. Effects of resourcefulness on internet game addiction among college students: The mediating role of anxiety and the moderating role of gender. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:986550. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.986550

42. Wu J and Siu ACK. Problematic mobile phone use by Hong Kong adolescents. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:551804. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551804

43. Liu J, Xu Z, Zhu L, Xu R, and Jiang Z. Mobile phone addiction is associated with impaired cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression of negative emotion. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:988314. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.988314

44. Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, and Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2016) 71:252–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

45. Ng CSM and Chan VCW. Prevalence and associated factors of alexithymia among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113126. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113126

46. Lyvers M, Salviani A, Costan S, and Thorberg FA. Alexithymia, narcissism and social anxiety in relation to social media and internet addiction symptoms. Int J Psychol. (2022) 57:606–12. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12840

47. Fung XCC, Siu AMH, Potenza MN, O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Chen C-Y, et al. Problematic use of internet-related activities and perceived weight stigma in schoolchildren: A longitudinal study across different epidemic periods of COVID-19 in China. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:675839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.675839

48. Wang S, Zhang Y, Ding W, Meng Y, Hu H, Liu Z, et al. Psychological distress and sleep problems when people are under interpersonal isolation during an epidemic: A nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e77. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.78

49. Wang S, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Ding W, Meng Y, Hu H, et al. A nationwide evaluation of the prevalence of and risk factors associated with anxiety, depression and insomnia symptoms during the return-to-work period of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:2275–86. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02046-4

50. Zhao C, Xu H, Lai X, Yang X, Tu X, Ding N, et al. Effects of online social support and perceived social support on the relationship between perceived stress and problematic smartphone usage among chinese undergraduates. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:529–39. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S302551

51. Guo N, Wang MP, Luk TT, Ho SY, Fong DYT, Chan SS-C, et al. The association of problematic smartphone use with family well-being mediated by family communication in Chinese adults: A population-based study. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:412–9. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.39

52. Sun Y, Wu K, Wang L, Zhao X, Che Q, Guo Y, et al. From parents to peers! Social support and peer attachment as mediators of parental attachment and depression: A Chinese perspective. J Affect Disord. (2025) 380:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.03.043

53. Thompson SF, Zalewski M, Kiff CJ, Moran L, Cortes R, and Lengua LJ. An empirical test of the model of socialization of emotion: Maternal and child contributors to preschoolers’ emotion knowledge and adjustment. Dev Psychol. (2020) 56:418–30. doi: 10.1037/dev0000860

54. Butterfield RD, Siegle GJ, Lee KH, Ladouceur CD, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, et al. Parental coping socialization is associated with healthy and anxious early-adolescents’ neural and real-world response to threat. Dev Sci. (2019) 22:e12812. doi: 10.1111/desc.12812

55. MacDougall M and Steffen A. Self-efficacy for controlling upsetting thoughts and emotional eating in family caregivers. Aging Ment Health. (2017) 21:1058–64. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1196335

56. Rodriguez EM, Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Wilson HW, Brown LK, and Houck C. Family environment, coping, and mental health in adolescents attending therapeutic day schools. J Adolesc. (2014) 37:1133–42. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.012

57. Sahi RS, Eisenberger NI, and Silvers JA. Peer facilitation of emotion regulation in adolescence. Dev Cognit Neurosci. (2023) 62:101262. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101262

58. Williams WC, Morelli SA, Ong DC, and Zaki J. Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2018) 115:224–54. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000132

59. Berghoff CR, Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, Baer MM, Turner BJ, Tull MT, et al. Daily associations of interpersonal and emotional experiences following stressful events among young adults with and without nonsuicidal self-injury. J Clin Psychol. (2022) 78:2329–40. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23359

60. Haslam C, Cruwys T, Milne M, Kan C-H, and Haslam SA. Group ties protect cognitive health by promoting social identification and social support. J Aging Health. (2016) 28:244–66. doi: 10.1177/0898264315589578

61. Allen JP. Rethinking peer influence and risk taking: A strengths-based approach to adolescence in a new era. Dev Psychopathol. (2024) 36:2244–55. doi: 10.1017/S0954579424000877

62. Alotaibi MS, Fox M, Coman R, Ratan ZA, and Hosseinzadeh H. Perspectives and experiences of smartphone overuse among university students in umm al-qura university (UQU), Saudi Arabia: A qualitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:4397. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074397

63. Guevara RM, Moral-García JE, Urchaga JD, and López-García S. Relevant factors in adolescent well-being: family and parental relationships. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:7666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147666

64. Koppelberg P, Kersting A, and Suslow T. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems in healthy young individuals. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23:688. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05191-z

65. McQuade JD, Taubin D, and Mordy AE. Positive emotion dysregulation and social impairments in adolescents with and without ADHD. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. (2024) 52:1803–15. doi: 10.1007/s10802-024-01237-2

66. Morelli SA, Lee IA, Arnn ME, and Zaki J. Emotional and instrumental support provision interact to predict well-being. Emotion. (2015) 15:484–93. doi: 10.1037/emo0000084

67. Song J-H, Colasante T, and Malti T. Helping yourself helps others: Linking children’s emotion regulation to prosocial behavior through sympathy and trust. Emotion. (2018) 18:518–27. doi: 10.1037/emo0000332

68. Seddon JA, Reaume CL, and Thomassin K. A six-week group program of emotion focused family therapy for parents of children with mental health challenges: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2025) 25:131. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06382-y

69. Jiménez L, Hidalgo V, Baena S, León A, and Lorence B. Effectiveness of structural–strategic family therapy in the treatment of adolescents with mental health problems and their families. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1255. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071255

70. Bernecker SL, Williams JJ, Caporale-Berkowitz NA, Wasil AR, and Constantino MJ. Nonprofessional peer support to improve mental health: randomized trial of a scalable web-based peer counseling course. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e17164. doi: 10.2196/17164

Keywords: alexithymia, problematic smartphone use, social support, depressed adolescents, moderating effect

Citation: Liu S, Wu Y, Sun F, Zhou Y and Yin A (2025) The moderating role of social support in the relationship between alexithymia and problematic smartphone use among Chinese depressed adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 16:1650290. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1650290

Received: 19 June 2025; Accepted: 15 September 2025;

Published: 01 October 2025.

Edited by:

Ming Ai, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Shu Wang, Capital Medical University, ChinaMuflih Muflih, Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Wu, Sun, Zhou and Yin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongjie Zhou, cWluZ3podTExMDhAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Aihua Yin, eWFpaHVhZGVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Shumiao Liu

Shumiao Liu Yufeng Wu1

Yufeng Wu1 Yongjie Zhou

Yongjie Zhou