Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of mental health disorders and their associations with chronic physical diseases in secondary healthcare settings in Kuwait.

Methods:

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed data collected from electronic health records of psychiatric care units in secondary healthcare hospitals in Kuwait. Mental health disorders were diagnosed by professionals and documented using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). We collected both mental and physical health data, along with basic demographic information. Logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, drug abuse, and developmental disorders were used to examine associations. Results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results:

A total of 11921 patient records from psychiatric units in secondary care hospitals were analyzed. Among these patients, 41.1% (n= 4902) had a chronic mental health disorder, with depression being the most common (33.7%, n= 4023). Comorbid chronic mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases were observed in 19.5% (n= 2319) of patients. Patients with chronic physical diseases were 1.8 times more likely to have a chronic mental health disorder compared to those without chronic diseases (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.6–2.0, p< 0.001). Depression was significantly associated with cancer (AOR, 2.9; 95%CI, 2.4–3.6), diabetes (AOR, 2.0; 95%CI, 1.7–2.3), renal disease (AOR, 1.8; 95%CI, 1.5–2.1), hypertension (AOR, 1.7; 95%CI, 1.4–2.0), neurological disease (AOR, 1.6; 95%CI, 1.4–1.8), cardiovascular disease (AOR, 1.5; 95%CI, 1.3–1.8), and respiratory disease (AOR, 1.2; 95%CI, 1.0–1.5). Somatic symptom disorder was significantly associated with neurological disease (AOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.0).

Conclusions:

This study revealed a substantial burden of mental health disorders, with depression showing significant associations with multiple chronic physical diseases. However, causal inferences cannot be drawn from this cross-sectional design. These findings are hypothesis-generating and highlight the need for further research on systematic mental health monitoring in secondary care populations.

1 Introduction

Mental health disorders contribute substantially to the global burden of morbidity and mortality (1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in every eight people worldwide is living with a mental health disorder (2). In the Middle East, the prevalence of mental illness in the general population ranges from 15.6% to 35.5% (3). In Kuwait, a study reported that 42.7% of patients attending primary health clinics had a mental health disorder (4). Mental health disorders have long been recognized as contributing to poor quality of life, premature mortality, and substantial healthcare costs. Individuals with severe mental health disorders are estimated to die 10 to 20 years earlier than those without such conditions (5). Moreover, patients with both mental and physical health comorbidities are at a higher risk of mortality compared to those with mental health disorders alone (6). The economic burden associated with mental health disorders is immense. In the USA, medical spending to treat adults with mental health disorders reached $106.5 billion in 2019 (7).

Mental health disorders constitute a wide range of conditions, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, psychotic disorders, delirium, and schizophrenia (8). The etiology of mental illness is not yet fully understood but appears to involve a complex interplay of biological, psychological and social factors (9).

Mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases have become two major health challenges, often leading to poorer health outcomes. Numerous studies have reported that people with mental health disorders are at increased risk of developing chronic physical diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes (10, 11). For example, depression can cause physiological changes, including stress hormone imbalance, poor blood circulation, and inflammation, all of which may increase the risk of chronic physical disease (12, 13). Conversely, the psychological burden of managing a chronic physical disease can exacerbate mental health problems, creating a cycle of adverse health outcomes (14). Many studies have shown that individuals with diabetes, hypertension, and asthma are more likely to experience psychological distress (15–17).

Psychological support plays a pivotal role in improving outcomes for individuals with chronic physical illnesses and in preventing the onset or progression of these conditions (18). Addressing psychological challenges in patients enhances treatment adherence, promotes healthier lifestyle behaviors, and strengthens self-management capacities, which collectively contribute to improved disease control and overall quality of life (19, 20). However, in clinical care, mostly physicians pay less attention to the interdependence of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases. The primary focus typically remains on managing physical symptoms, ensuring medication adherence, and preventing complications. As a result, mental health issues are often overlooked or underestimated.

In Western countries, mental health status is routinely assessed, and appropriate psychological support is provided (21). Similarly, in Kuwait, mental healthcare services are available within secondary healthcare settings, where professionals assess mental health conditions and provide support to the affected patients (22). However, the prevalence of mental illness in secondary healthcare settings has not yet been reported. Previous local studies, mainly conducted in primary healthcare settings, have been limited to a narrow range of mental health disorders, primarily depression and anxiety (4, 23, 24). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the broader spectrum of mental health disorders and their associations with chronic physical diseases in secondary healthcare settings in Kuwait.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and population

This study is a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of patient data collected from psychiatric care units of secondary healthcare hospitals in Kuwait. Mental health disorders were assessed by professionals and documented in patients’ electronic health records using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). We extracted data from the electronic medical records of all patients who attended psychiatric care units between January 2016 and December 2019. The extracted data included patient age, sex, mental health diagnoses, physical health conditions, and appointment dates.

The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethical Committee of the Ministry of Health, Kuwait (No. 1245). To ensure patient confidentiality and data privacy, all identification details were anonymized prior to data extraction for analysis.

2.2 Data screening and extraction

Data screening was conducted by two medical graduates, F. Alsarraf and S. Raina, who independently reviewed electronic medical records. Inclusion criteria for the study were individuals aged 18 years or older with complete information on age, sex, and mental and physical health assessment records. We included only the first-visit assessment record for each patient, even if multiple entries were available. Records with missing or invalid entries were excluded to maintain the accuracy and integrity of the analysis.

Mental health disorders were identified from patient files using diagnostic codes based on the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (8). These conditions included delirium, psychotic disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, somatic symptom disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, suicidal behaviors and dementia. All of these are classified within ICD-10th revision as mental disorders. Furthermore, we grouped acute conditions (delirium, and suicidal behaviors) and chronic conditions (depression, schizophrenia, chronic psychosis, anxiety, bipolar disorder, somatic symptom disorder, dementia). We acknowledge that this classification may contribute to higher prevalence estimates and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

We included all defined chronic physical diseases (yes or no), such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, neurological disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM, USA, version 29) software. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics. Chi-squared tests were then performed between the prevalence of mental health disorders and sociodemographic characteristics or chronic health diseases.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the associations between mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases, controlling for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, developmental disorder, and drug abuse. The results were presented with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated. The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 for all statistical tests, and two-tailed p-values were reported.

3 Results

Table 1 presents the distribution of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients. This study included 11921 patients, with an almost equal gender distribution (51.0% females and 49.0% males). The age range was 18–99 years (mean ± SD: 51.0± 21.3 years).

Table 1

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–32 years | 3132 | 26.3 |

| 33–50 years | 2864 | 24.0 |

| 51–70 years | 3081 | 25.8 |

| >70 years | 2844 | 23.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5845 | 49.0 |

| Female | 6076 | 51.0 |

| Physical and mental health | ||

| Depression | 4023 | 33.7 |

| Psychosis | 1316 | 11.0 |

| Somatic symptom disorder | 686 | 5.8 |

| Schizophrenia | 247 | 2.1 |

| Anxiety disorder | 228 | 1.9 |

| Bipolar disorder | 109 | 0.9 |

| Delirium | 2381 | 20.0 |

| Suicidal behaviors | 1834 | 15.4 |

| Sleep disorder | 1759 | 14.8 |

| Burn | 120 | 1.0 |

| Drug overdose | 1156 | 9.7 |

| Substance used | 1072 | 9.0 |

| Developmental Disability | 31 | 0.3 |

| Parkinson | 80 | 0.7 |

| Alzheimer | 99 | 0.8 |

| Dementia | 148 | 1.2 |

| Chronic physical diseases | 4805 | 40.3 |

| Neurological disease | 1792 | 15.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 931 | 7.8 |

| Respiratory disease | 432 | 3.6 |

| Renal disease | 770 | 6.5 |

| Diabetes | 764 | 6.4 |

| Hypertension | 625 | 5.2 |

| Cancer | 435 | 3.6 |

| Chronic liver disease | 54 | 0.5 |

| Hypothyroidism | 75 | 0.6 |

| Chronic gastrointestinal disease | 183 | 1.5 |

| Epilepsy | 259 | 2.2 |

| Fits | 143 | 1.2 |

| Seizures | 94 | 0.8 |

| Orthopedics | 114 | 1.0 |

| Injuries-RTA | 225 | 1.9 |

| Injured-other causes | 550 | 4.6 |

| Assault | 23 | 0.2 |

Patients demographics, physical and mental health disorders (n= 11921).

3.1 Mental health disorders

Of the total 11921 patients, 64.9% (n= 7735) had at least one mental health disorder when all ICD-10 mental health conditions were grouped (including both chronic disorders and acute or transient presentations such as delirium and suicidal behaviors). When limited to chronic mental disorders only (e.g., depressive disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, somatic symptom disorder, chronic psychosis), the prevalence was 41.1% (n = 4,902). Acute or transient mental health conditions (e.g., delirium, suicidal behaviors) accounted for 23.8% (n = 2,833), whereas 35.1% (n = 4,183) of the total sample had no recorded mental health disorder.

Among these with chronic mental disorders, 19.7% had one disorder, 13.3% had two disorders, and 8.2% had more than two disorders. The most common disorder was depression (33.7%). Other disorders were psychosis (11.0%), somatic symptom disorder (5.8%), schizophrenia (2.1%), anxiety (1.9%), and bipolar disorder (0.9%). Among acute mental disorders, the most common were delirium (20.0%) followed by suicidal behaviors (15.4%). Neurological conditions, including epilepsy (2.2%), dementia (1.2%), and seizures (0.8%), were also observed.

Chronic mental health disorders were more prevalent among females than males (45.2% vs 36.9%), whereas acute mental health disorders were slightly more prevalence in males compared to females (26.7% vs 20.9%) (χ2 = 97.9; p= 0.001). Across age groups, chronic disorders were most frequent among those aged 51–70 years (46.0%) and 33–50 years (41.7%), while acute disorders were most prominent among those aged >70 years (32.9%) (χ² = 356.1, p <.001) (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2 Mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases

In this cohort, the overall prevalence of chronic physical disease was 40.3%. These included neurological disease (15.0%), cardiovascular disease (7.8%), respiratory disease (3.6%), renal disease (6.5%), diabetes (6.4%), hypertension (5.2%), and cancer (3.6%). A small proportion of patients had other chronic conditions such as liver disease (0.5%), gastrointestinal disease (1.5%), and hypothyroidism (0.6%). Of the total patients, 19.5% (n= 2319) had comorbid chronic mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases, whereas 9.6% (n=1143) had comorbid chronic physical diseases and acute mental health disorders. In adjusted regression analyses, the presence of chronic physical disease was associated with a 1.8-fold higher likelihood of chronic mental health disorders (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.6–2.0, p < 0.001), but showed a week association with acute mental health disorders (AOR=1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.2, p=0.045).

3.3 Sensitivity and specificity between chronic physical diseases and mental health disorders

Chronic physical disease moderately identified chronic mental disorders, with a sensitivity of 47.3% (95% CI: 46.0–48.7) and specificity of 64.6% (95% CI: 64.0–65.2), but its ability to identify acute mental disorders was lower, with a sensitivity of 40.3% (95% CI: 38.6–42.0) and specificity of 59.7% (95% CI: 58.7–60.7). When using mental disorders to predict chronic physical disease, chronic mental disorders had similar sensitivity (48.3%, 95% CI: 46.9–49.7) but slightly lower specificity (63.7%, 95% CI: 62.6–64.8), whereas acute mental disorders had low sensitivity (23.8%, 95% CI: 22.7–25.0) and higher specificity (76.3%, 95% CI: 75.3–77.2). These results indicate that chronic physical disease is a modest predictor of chronic mental disorders and less effective for acute mental disorders, while acute mental disorders are poor predictors of chronic physical disease.

3.4 Disease-specific prevalence and associations

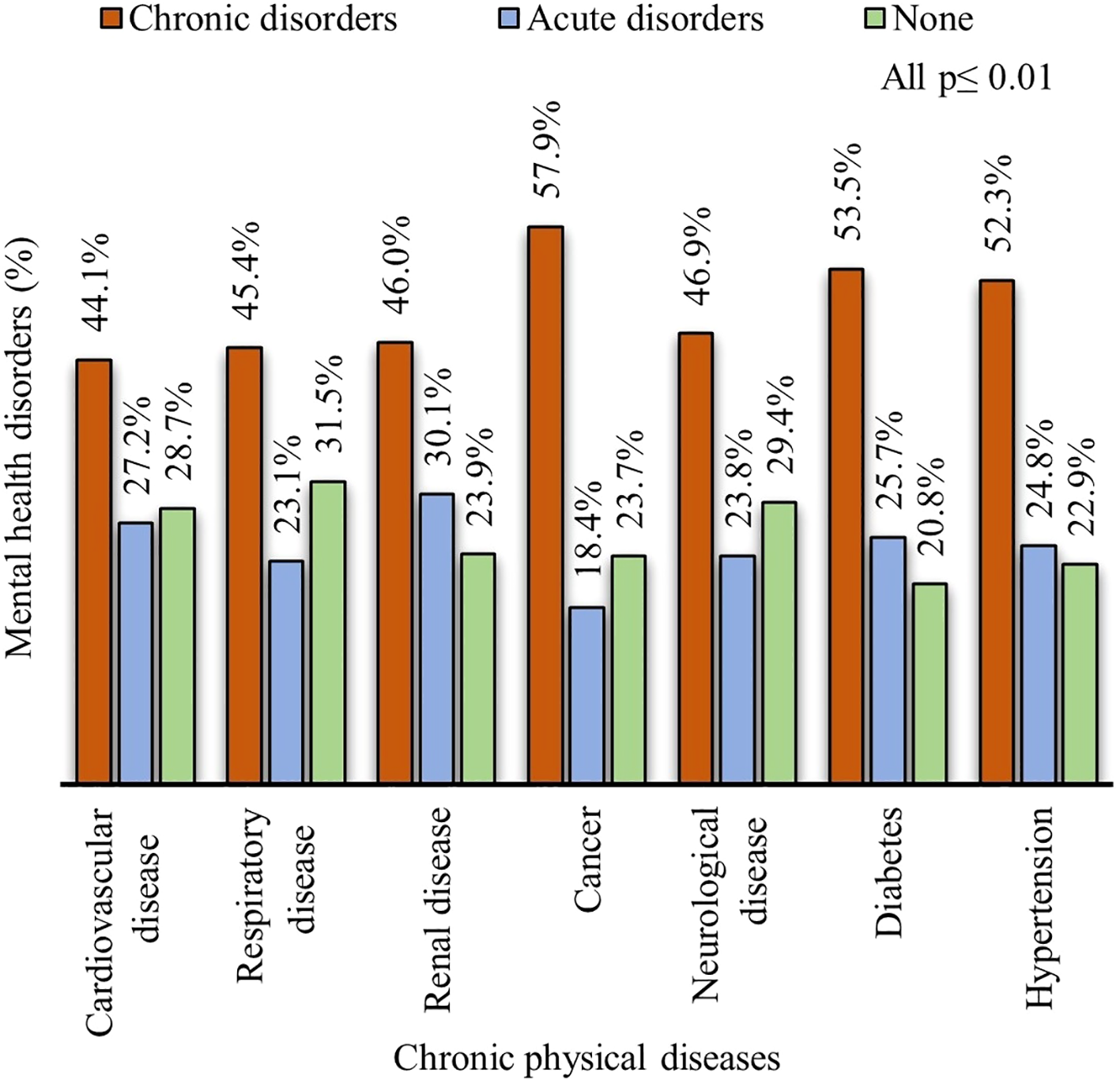

Disease-specific analyses showed higher prevalence of chronic mental health disorders among patients with diabetes (53.5%), hypertension (52.3%), cancer (57.9%), renal disease (46.0%), cardiovascular disease (44.1%), neurological disease (46.9%), and respiratory disease (45.4%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Prevalence of mental health disorders among patients with chronic physical diseases.

Table 2 presents the most common mental health disorders among patients with chronic physical diseases and their associations. Depression was the most common disorder among patients with cancer (53.8%), diabetes (45.4%), renal disease (41.8%), hypertension (41.0%), neurological disease (39.5%), cardiovascular disease (37.2%), and respiratory disease (33.1%). In contrast, psychosis (9.8–12.7%), somatic symptom disorder (2.9–7.5%), anxiety (1.1–2.7%), and bipolar disorder (0.2–1.4%) were comparatively less prevalent across chronic physical diseases. Delirium was also common among patients with chronic physical diseases (14.3 – 24.9%). Some patients with delirium were also coded under chronic psychiatric disorders (approximately 14.5%), reflecting overlap in electronic health record coding.

Table 2

| Comorbid | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Cardiovascular disease | 346 (37.2) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 143 (33.1) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 0.135 | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.047 |

| Renal disease | 322 (41.8) | 1.7 (1.5, 2.0) | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disease | 708 (39.5) | 1.5 (1.4, 1.7) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 234 (53.8) | 2.8 (2.3, 3.3) | <0.001 | 2.9 (2.4, 3.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 347 (45.4) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.3) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.7, 2.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 256 (41.0) | 1.6 (1.4, 1.9) | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Psychosis | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Cardiovascular disease | 102 (11.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.844 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.159 |

| Respiratory disease | 48 (11.1) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 0.969 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.363 |

| Renal disease | 98 (12.7) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.196 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.790 |

| Neurological disease | 203 (11.3) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 0.851 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.359 |

| Cancer | 50 (11.5) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.836 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.423 |

| Diabetes | 75 (9.8) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.256 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.130 |

| Hypertension | 69 (11.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.920 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.161 |

| Somatic symptom disorder | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Cardiovascular disease | 49 (5.3) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.731 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 0.094 |

| Respiratory disease | 22 (5.1) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.695 | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) | 0.574 |

| Renal disease | 22 (2.9) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.002 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.069 |

| Neurological disease | 134 (7.5) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 0.002 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 18 (4.1) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.214 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) | 0.669 |

| Diabetes | 36 (4.7) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.341 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 0.949 |

| Hypertension | 35 (5.6) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 0.947 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 0.131 |

| Delirium | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Cardiovascular disease | 212 (22.8) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 0.038 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.010 |

| Respiratory disease | 85 (19.7) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.922 | 0.7 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.021 |

| Renal disease | 192 (24.9) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 0.001 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.393 |

| Neurological disease | 360 (20.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.916 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.111 |

| Cancer | 62 (14.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.004 | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 168 (22.0) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 0.165 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.387 |

| Hypertension | 129 (20.6) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) | 0.644 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.005 |

Association between common mental disorders and chronic health diseases.

Model 1: Unadjusted; Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, developmental disorder, and drug abuse.

OR, Odds Ratio; AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95% CI, 95% Confidence Interval.

Reference group: Patients without any chronic disease.

In adjusted regression analysis, depression was strongly associated with cancer (AOR, 2.9; 95% CI, 2.4–3.6; p< 0.001), diabetes (AOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7–2.3; p< 0.001), renal disease (AOR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.5–2.1; p< 0.001), hypertension (AOR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4–2.0; p< 0.001), neurological disease (AOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4–1.8; p< 0.001) and cardiovascular disease (AOR, 1.5; 95%CI, 1.3–1.8; p< 0.001). Somatic symptom disorder was associated with neurological disease (AOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.0; p< 0.003). Psychosis showed no significant associations with chronic physical diseases in this cohort. Delirium was inversely associated with cardiovascular disease (AOR=0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9, p = 0.01), respiratory disease (AOR=0.7, 95% CI: 0.7–1.0, p = 0.021), cancer (AOR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.4–0.7, p < 0.001), and hypertension (AOR=0.7, 95% CI: 0.6–0.9, p = 0.005).

4 Discussion

We explored all types of mental health disorders and chronic physical diseases in a large cohort dataset from secondary care hospitals in Kuwait. Our study contributes by providing a large dataset with clinician diagnoses, highlighting comorbidity patterns with chronic diseases. In this cohort of patients attending psychiatric units in secondary care hospitals in Kuwait, 64.9% had at least one mental health diagnosis when all ICD-10 mental health conditions were considered, while 41.2% had a chronic psychiatric disorder. Approximately 40.3% of the cohort had a chronic physical disease.

The prevalence of chronic mental health disorders in our study was slightly lower than that reported in a recent Kuwait primary-care study (42.7%) (4), but aligns with estimates from other secondary care hospital settings, where chronic psychiatric disorders typically account for 40–45% of patients (25).

For broader context, hospital-based studies internationally have reported comparable ranges: for example, a Puerto Rican hospital system integrating clinical health psychology services found 53% of inpatients had a mental disorder (26), while systematic reviews show prevalence across general practice populations varying widely (2.4–56.3%) depending on setting and diagnostic methodology (27). These comparisons should be interpreted cautiously because differences in care level (primary vs. secondary), referral patterns, and coding practices can substantially influence recorded prevalence.

In this study, most patients had depression, while anxiety was relatively less common. The prevalence of depression observed in this study was slightly higher than that reported in primary health clinics in Kuwait (4). This difference may be explained by the secondary healthcare setting of our study, which typically manages patients with more complex conditions compared to primary healthcare clinics. The prevalence of depression in our study was comparatively higher than developed countries (24.0%) but lower than developing countries (38.0%) in outpatient clinical settings (28). We also observed acute disorders, with delirium (20.0%) being common. The prevalence of delirium was almost equal among patients with chronic physical diseases (20.1%) and those without chronic physical diseases (19.9%). For comparison, international hospital studies have generally reported delirium prevalence ranging from 9% to 32% in general acute care settings (29, 30). Our estimates is lower than that reported in meta-analyses of critically ill patients (82%) (31), and older cancer patients (61.4%) (32). Another meta-analysis in patients with diabetes found delirium prevalence of 31% in prospective cohort studies and 26% in retrospective studies (33). Overall, our study highlights the prevalence of delirium in Kuwait, which should not be overlooked in clinical practice. As reported, delirium is a severe neuropsychiatric syndrome arising from disruptions in neuroinflammation, vascular function, metabolism, and neurotransmission, leading to acute impairments in attention, awareness, and cognition (34).

Conversely, we found a relatively low prevalence of anxiety disorder compared to international and regional studies (35, 36). This may be due to anxiety symptoms often recorded under other diagnostic categories or overshadowed by more severe disorders or overlap with somatic presentations (37). Additional contributing factors may include under-diagnosis, coding bias, and under-recording in EHR workflows. These issues highlight the need for systematic diagnostic and EHR coding practices that minimize overlap with other disorders and improve the accuracy of prevalence estimates.

This study also highlights the sex- and age-related patterns in mental health disorder. Chronic mental health disorders were more common among women than men, aligning with established evidence that women are more vulnerable, possibly due to social and cultural factors (38). Across age groups, the 51–70-year group showed the highest prevalence of chronic disorders compared to younger and older age groups, plausibly reflecting cumulative exposure to risk factors and comorbidities over the life course.

Of the total sample, 19.5% of patients had both chronic mental health disorders and chronic health diseases. The prevalence of comorbid mental illness and chronic physical diseases in our study was lower than that reported in a meta-analysis from Africa (45.8%), Asia (37.0%) and the USA (26.8%) (39). However, regression analyses showed that the presence of chronic physical disease was associated with a 1.8-fold higher likelihood of chronic mental health disorders. Depression alone was more common among patients with chronic diseases (39.7%), compared to those without chronic disease (29.7%), with significantly higher odds among patients with hypertension, renal disease, diabetes, and cancer. The comorbidity of depression was 41.0% in patients with hypertension and 45.4% in patients with diabetes. In comparison, a recent local study conducted in a public primary healthcare setting reported higher rates of comorbid depression with hypertension (54%) and type 2 diabetes (81%) (40). Similarly, a study from Pakistan reported higher prevalence of depression among cancer patients (67%), but lower prevalence in patients with diabetes (38%) and cardiovascular diseases (33%), than our study (41). Many studies have identified depression as an important risk factor associated with chronic physical diseases, including cardiovascular disease (42), diabetes (17), hypertension (43), and kidney disease (44). People with diabetes and cardiovascular disease consistently exhibited higher rates of depression (45, 46). Conversely, a retrospective cohort study suggested that depression may also increase the risk of cancer (47). Likewise, the relationship between depression and neurological diseases is well-documented (48).

In this study, somatic symptom disorders were comparatively uncommon in both patients with and without chronic physical diseases. This finding align with a previous study reporting 6.8% prevalence of somatic symptom disorder among patients with major medical disorders (49). Despite its lower prevalence, somatic symptom disorder was significantly associated with neurological diseases, suggesting that brain tissue damage, such as that seen in stroke, may contribute to somatic symptom disorder (50). Similarly, psychosis was observed in approximately 11% of patients, almost equally distributed among patients with and without chronic physical diseases. In contrast, a recent study from the UK reported a lower prevalence of psychosis (3%) in primary care mental health services (51), it may be higher in healthcare settings due to the presence of comorbid mental disorders (52).

Overall, the high prevalence of mental health disorders in this cohort underscores the substantial mental health burden in clinical populations. Nearly one-fifth of patients had comorbid chronic physical diseases, which were associated with an increased likelihood of mental health disorders. Depression showed particularly strong associations with chronic physical conditions, highlighting the need of systematic mental health screening among these patients. Delirium was also prevalent in patients, highlighting the need of careful monitoring of acute cognitive disturbances in clinical practice.

This study also has limitations. First, the data were collected retrospectively, which lacked information on patients’ socioeconomic status and severity of psychological symptoms, both of which may affect associations with chronic physical diseases. Second, information on treatment approaches for mental illness before visits to secondary care hospitals was also unavailable, limiting our ability to assess non-pharmacological interventions. Third, because data were drawn from psychiatric units in secondary hospitals, referral bias is likely, with more severe or complex patients overrepresented compared to community or primary care settings; this limits the generalizability of our findings. Fourth, delirium is an acute, transient syndrome that may have been coded alongside chronic psychiatric diagnoses in our data set. This coding overlap can inflate prevalence estimates and limits direct comparability with studies using strictly separated diagnostic categories; therefore, delirium prevalence should be interpreted cautiously. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference.

In conclusion, this study reveals a substantial burden of mental health disorders, especially depression, among patients attending secondary healthcare psychiatric units in Kuwait. Strong associations were observed between depression and several chronic physical diseases, but causal relationships cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional design. These findings are hypothesis-generating and suggest that routine monitoring of mental health among patients with chronic diseases warrants further evaluation. However, given the limitations of retrospective electronic health record data and potential referral and documentation biases, these results should be interpreted cautiously, and future prospective studies are needed to confirm these associations. Future work should validate routine ICD-10 coding practices in psychiatric units and explore how referral criteria and coding conventions influence prevalence estimates.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Standing Committee for Coordination of Health and Medical Research, Ministry of Health Kuwait. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because this study is a retrospective study.

Author contributions

AA: Validation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Software, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology. MI: Software, Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Data curation, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. FA: Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SR: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Software, Visualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis. HA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Resources, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Validation. EA: Software, Methodology, Data curation, Resources, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The manpower used in this study has been funded by the Kuwait Foundation of Advancement of Science (KFAS) and the Ministry of Health, Kuwait. The funding agency did not influence the study design, data analysis, interpretation, or report preparation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1658457/full#supplementary-material

References

1

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9:137–50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

2

WHO . World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All: Executive Summary. World Health Organization (2022). Available online at: https://books.google.com.kw/books?id=lnkOEQAAQBAJ.

3

Ibrahim NK . Epidemiology of mental health problems in the Middle East. In: LaherI, editor. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2019). p. 1–18.

4

Alkhadhari S Alsabbrri AO Mohammad IH Atwan AA Alqudaihi F Zahid MA . Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the primary health clinic attendees in Kuwait. J Affect Disord. (2016) 195:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.037

5

Luciano M Pompili M Sartorius N Fiorillo A . Editorial: Mortality of people with severe mental illness: Causes and ways of its reduction. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:1009772. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1009772

6

Tan XW Lee ES Toh MPHS Lum AWM Seah DEJ Leong KP et al . Comparison of mental-physical comorbidity, risk of death and mortality among patients with mental disorders — A retrospective cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 142:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.039

7

Soni A . Healthcare expenditures for treatment of mental disorders: estimates for adults ages 18 and older, US civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2019. (2022). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st539/stat539.pdf.

8

Organization WH . The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines Vol. 362. Geneva:World Health Organization (1992).

9

Alegría M NeMoyer A Falgàs Bagué I Wang Y Alvarez K . Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2018) 20:95. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0969-9

10

Belcher J Myton R Yoo J Boville C Chidwick K . Exploring the physical health of patients with severe or long-term mental illness using routinely collected general practice data from MedicineInsight. Aust J Gen Practice. (2021) 50:944–9. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-20-5563

11

De Hert M Dekker JM Wood D Kahl KG Holt RIG Möller HJ . Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry. (2009) 24:412–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.005

12

Beurel E Toups M Nemeroff CB . The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron. (2020) 107:234–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.002

13

Yin Y Ju T Zeng D Duan F Zhu Y Liu J et al . Inflamed” depression: A review of the interactions between depression and inflammation and current anti-inflammatory strategies for depression. Pharmacol Res. (2024) 207:107322. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107322

14

Jayatilleke N Hayes RD Chang CK Stewart R . Acute general hospital admissions in people with serious mental illness. psychol Med. (2018) 48:2676–83. doi: 10.1017/s0033291718000284

15

Liao B Xu D Tan Y Chen X Cai S . Association of mental distress with chronic diseases in 1.9 million individuals: A population-based cross-sectional study. J psychosomatic Res. (2022) 162:111040. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.111040

16

Adzrago D Williams DR Williams F . Multiple chronic diseases and psychological distress among adults in the United States: the intersectionality of chronic diseases, race/ethnicity, immigration, sex, and insurance coverage. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2024) 60:181–99. doi: 10.1007/s00127-024-02730-1

17

AlOzairi A Irshad M AlKandari J AlSaraf H Al-Ozairi E . Prevalence and predictors of diabetes distress and depression in people with type 1 diabetes. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1367876. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1367876

18

Fekete EM Antoni MH Schneiderman N . Psychosocial and behavioral interventions for chronic medical conditions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2007) 20:152–7. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280147724

19

Ganguli A Clewell J Shillington AC . The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient preference adherence. (2016) 10:711–25. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s101175

20

Al-Ozairi A Irshad M Alsaraf H AlKandari J Al-Ozairi E Gray SR . Association of physical activity and sleep metrics with depression in people with type 1 diabetes. Psychol Res Behav Manage. (2024) 17:2717–25. doi: 10.2147/prbm.S459097

21

Jaeschke K Hanna F Ali S Chowdhary N Dua T Charlson F . Global estimates of service coverage for severe mental disorders: findings from the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017. Global Ment Health. (2021) 8:e27. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2021.19

22

Kaladchibachi S Al-Dhafiri AM . Mental health care in Kuwait: Toward a community-based decentralized approach. Int Soc Work. (2018) 61:329–34. doi: 10.1177/0020872816661403

23

Al-Ghareeb HY Al-Zayed KE Albaba ME . Prevalence of undiagnosed Depression among adult Type 2 diabetic patients attending Adan Primary Health Care Center in Kuwait. Middle East J Of Family Med. (2025) 23(2):16–33. doi: 10.5742/MEWFM.2025.95257854

24

Al-Otaibi B Al-Weqayyan A Taher H Sarkhou E Gloom A Aseeri F et al . Depressive symptoms among Kuwaiti population attending primary healthcare setting: prevalence and influence of sociodemographic factors. Med Principles Practice. (2007) 16:384–8. doi: 10.1159/000104813

25

Li Z Kormilitzin A Fernandes M Vaci N Liu Q Newby D et al . Validation of UK Biobank data for mental health outcomes: A pilot study using secondary care electronic health records. Int J Med Informatics. (2022) 160:104704. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104704

26

Scott G Beauchamp-Lebrón AM Rosa-Jiménez AA Hernández-Justiniano JG Ramos-Lucca A Asencio-Toro G et al . Commonly diagnosed mental disorders in a general hospital system. Int J Ment Health Systems. (2021) 15:61. doi: 10.1186/s13033-021-00484-w

27

Ravichandran N Dillon E McCombe G Sietins E Broughan J O’ Connor K et al . Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders in General Practice from 2014 to 2024: A literature review and discussion paper. Irish J psychol Med. (2025), 1–8. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2025.24

28

Wang J Wu X Lai W Long E Zhang X Li W et al . Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017173. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017173

29

Fuchs S Bode L Ernst J Marquetand J von Känel R Böttger S . Delirium in elderly patients: Prospective prevalence across hospital services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 67:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.08.010

30

Schubert M Schürch R Boettger S Garcia Nuñez D Schwarz U Bettex D et al . A hospital-wide evaluation of delirium prevalence and outcomes in acute care patients - a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:550. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3345-x

31

Oh ES Needham DM Nikooie R Wilson LM Zhang A Robinson KA et al . Antipsychotics for preventing delirium in hospitalized adults. Ann Internal Med. (2019) 171:474–84. doi: 10.7326/M19-1859

32

Martínez-Arnau FM Buigues C Pérez-Ros P . Incidence of delirium in older people with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2023) 67:102457. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102457

33

Komici K Fantini C Santulli G Bencivenga L Femminella GD Guerra G et al . The role of diabetes mellitus on delirium onset: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc diabetol. (2025) 24:216. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02782-w

34

Wilson JE Mart MF Cunningham C Shehabi Y Girard TD MacLullich AMJ et al . Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2020) 6:90. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4

35

Walker J van Niekerk M Hobbs H Toynbee M Magill N Bold R et al . The prevalence of anxiety in general hospital inpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2021) 72:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.08.004

36

Okasha T Shaker NM El-Gabry DA . Mental health services in Egypt, the Middle East, and North Africa. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2025) 37:306–14. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2024.2400143

37

Zhu C Ou L Geng Q Zhang M Ye R Chen J et al . Association of somatic symptoms with depression and anxiety in clinical patients of general hospitals in Guangzhou, China. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2012) 34:113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.09.005

38

Ghuloum S . Gender differences in mental health in the Middle East. Int Psychiatry. (2018) 10:79–80. doi: 10.1192/S1749367600003982

39

Daré LO Bruand PE Gérard D Marin B Lameyre V Boumédiène F et al . Co-morbidities of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases in developing and emerging countries: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:304. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6623-6

40

Hussein Abdalla DK Alali SM Alsaqabi A Al-Kandari H Mahomed O . Depressive symptoms and associated factors among patients with diabetes in public primary healthcare facilities in Kuwait city, 2024. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:29960. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-13783-w

41

Abbas U Hussain N Tanveer M Laghari RN Ahmed I Rajper AB . Frequency and predictors of depression and anxiety in chronic illnesses: A multi disease study across non-communicable and communicable diseases. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0323126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323126

42

Kwak Y Kim Y Kwon SJ Chung H . Mental health status of adults with cardiovascular or metabolic diseases by gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020514

43

Wang L Li N Heizhati M Li M Yang Z Wang Z et al . Association of depression with uncontrolled hypertension in primary care setting: A cross-sectional study in less-developed northwest China. Int J Hypertension. (2021) 2021:6652228. doi: 10.1155/2021/6652228

44

Zhao J Wu M Zhang L Han X Wu J Wang C . Higher levels of depression are associated with increased all-cause mortality in individuals with chronic kidney disease: A prospective study based on the NHANES database. J Affect Disord. (2025) 390:119785. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.119785

45

Bojanić I Sund ER Sletvold H Bjerkeset O . Prevalence trends of depression and anxiety symptoms in adults with cardiovascular diseases and diabetes 1995–2019: The HUNT studies, Norway. BMC Psychol. (2021) 9:130. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00636-0

46

Al-Ozairi A Taghadom E Irshad M Al-Ozairi E . Association between depression, diabetes self-care activity and glycemic control in an Arab population with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes. (2023) 16:321–9. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S377166

47

Mössinger H Kostev K . Depression is associated with an increased risk of subsequent cancer diagnosis: A retrospective cohort study with 235,404 patients. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1–14. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13020302

48

Trifu SC Trifu AC Aluaş E Tătaru MA Costea RV . Brain changes in depression. Romanian J morphol embryol = Rev roumaine morphologie embryologie. (2020) 61:361–70. doi: 10.47162/rjme.61.2.06

49

Buck L Peters L Maehder K Hartel F Hoven H Harth V et al . Risk of somatic symptom disorder in people with major medical disorders: Cross-sectional results from the population-based Hamburg City Health Study. J psychosomatic Res. (2025) 189:111997. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2024.111997

50

Löwe B Toussaint A Rosmalen JGM Huang W-L Burton C Weigel A et al . Persistent physical symptoms: definition, genesis, and management. Lancet. (2024) 403:2649–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00623-8

51

Newman-Taylor K Maguire T Smart T Bayford E Gosden E Addyman G et al . Screening for psychosis risk in primary mental health care services - Implementation, prevalence and recovery trajectories. Br J Clin Psychol. (2024) 63:589–602. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12490

52

Fusar-Poli P Salazar de Pablo G Correll CU Meyer-Lindenberg A Millan MJ Borgwardt S et al . Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:755–65. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4779

Summary

Keywords

mental disorders, depression, delirium, cancer, hypertension, diabetes

Citation

Al-Ozairi A, Irshad M, Alsarraf F, Raina S, Alsaraf H and Al Ozairi E (2025) Prevalence of mental health disorders and their association with chronic physical diseases in Kuwait. Front. Psychiatry 16:1658457. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1658457

Received

02 July 2025

Accepted

01 October 2025

Published

17 October 2025

Corrected

27 October 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Ozayr Mahomed, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Reviewed by

Uzair Abbas, Dow University of Health Sciences, Pakistan

Mohammad Zafaryab, Alabama State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Al-Ozairi, Irshad, Alsarraf, Raina, Alsaraf and Al Ozairi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdullah Al-Ozairi, alozairi@gmail.com; Mohammad Irshad, mohammad.irshad@dasmaninstitute.org; Ebaa Al Ozairi, ebaa.alozairi@dasmaninstitute.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.