- Centre for Affective Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

Background: The prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ individuals (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, and other sexual/gender minorities) is not well understood. Studies suggest that LGBTIQ+ people may have higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders, potentially influenced by societal acceptance.

Aims: This systematic review aims to examine the prevalence of depressive disorders (DD), bipolar disorders (BD), and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations and explore potential associations with societal acceptance in different global regions.

Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, APA PsychInfo, and citations from 1990–2022 identified studies reporting on the prevalence of DD, BD, and anxiety disorders among LGBTIQ+ people. These rates were compared to societal acceptance, using the Williams’ Institute Global Acceptance Index, and to general population rates. Study quality was assessed with the National Institute of Health checklist.

Results: 123 studies from 31 countries were included, with 116 rated as good quality. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 15 to over 254,462,596. Mean prevalence rates in LGBTIQ+ populations from these studies was 35.3% for depressive disorders, 5.6% for bipolar disorders, and 34.3% for anxiety disorders. A significant correlation was found between societal acceptance and depressive and anxiety disorder prevalence rates in North American LGBTIQ+ populations.

Conclusions: This study found that LGBTIQ+ people experience markedly higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders compared to the general population, with societal acceptance correlating with these rates in North America. Further research is needed, particularly for underrepresented groups such as nonbinary individuals and those identifying as pansexual, asexual, or genderqueer.

Systematic review registration: www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42022320324.

Introduction

The prevalence and impact of affective disorders in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and people with other sexual/gender identities (LGBTIQ+) is not well understood, but trends in the evidence seem to indicate that LGBTIQ+ people may be more likely to be diagnosed with a mood or anxiety disorder. A meta-analysis by Meyer (1) found that lesbian, gay, and bisexual males and females were twice as likely to receive a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis compared to heterosexuals. In the developed world, rates of mood disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations range from 17.1% (2) to 21.4% (3). The evidence in the developing world is even more striking, with rates of depression in LGBTIQ+ people ranging from 19.1% (4) to 56% (5).

The stressors that LGBTIQ+ people experience may be associated with, or exacerbate the symptomology, of depressive disorders (DD), bipolar disorders (BD), or anxiety disorders. A report by the LGBTIQ+ organisation Stonewall (6) found that one in five sexual/gender minority youths in the UK had experienced not only social isolation, which in itself is linked to the development of depression (7), but also experienced hate crimes. This figure rises to two in five for transgender individuals. Suicide rates are also elevated, with some studies reporting a four times increased risk of LGBTIQ+ youth suicides compared to heterosexual controls (8). Additionally, non-suicidal self-injury is more apparent in LGBTIQ+ people, with lifetime prevalence rates of 29.7% and 46.7% in sexual and gender minorities respectively, relative to 14.6% in heterosexual and/or cisgendered individuals (9).

The severity of the environmental stressors experienced by LGBTIQ+ people may relate to societal acceptance. A lack of societal acceptance could create a hostile, stigmatised and prejudiced environment, and the accompanying social, environmental and minority stressors are known to increase the risk of mental illness (1). This varies between countries and can be measured using the Williams’ Institute’s Global Acceptance Index (GAI) (10) which provides a quantitative measure of the societal acceptance of LGBTIQ+ people.

To date, previous reviews have focused on affective disorders in the context of co-morbidities (10, 11), or specific sub-groups (such as gay or lesbian individuals) of the LGBTIQ+ population. No systematic reviews to our knowledge have compared prevalence rates across the LGBTIQ+ spectrum, nor have they explored whether prevalence rates correlate with the degree of public acceptance. The primary aim of this systematic review was to investigate the prevalence of depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, and anxiety disorders in the LGBTIQ+ population across countries. This systematic review aimed to compare prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders between regions and to explore the relationship between prevalence rates and public acceptance and equality of LGBTIQ+ people.

Methods

Protocol

The study protocol was submitted to the NIHR PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews on 1st April 2022 and registered on 25th July 2022 (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42022320324). We followed the PRISMA 2020 reporting guideline (12), and the completed PRISMA checklist is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles were determined prior to database searching. Studies were required to have investigated one (or more) of depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, and/or anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations. If participants had received a diagnosis of another primary psychiatric condition, the study was excluded. Diagnostic tools or measures were required to have been implemented in accordance with either DSM or ICD criteria. Studies exploring mood disorders in heterosexual and cisgendered individuals was included only if LGBTIQ+ populations were measured adjunctively as comparators. Studies including participants identifying as males who have sex with males, but not necessarily as gay or bisexual males, were included in this review as this group is often included in the “+” part of LGBTIQ +. There was no stipulated limitation on study settings or the age range of participants.

Cross-sectional, longitudinal, cohort, and retrospective chart reviews were included in the review while case studies and systematic reviews were excluded. Records were excluded from the review if English translations were unavailable, if studies were not peer-reviewed, or if studies focused primarily on potential mediators (such as HIV, minority stress, abuse, and COVID-19) that could have direct impact on prevalence rates of affective disorders. Moreover, studies were excluded if they did not include mood and anxiety disorder prevalence measures or odds ratios.

Literature search

Two reviewers (SJ and OP) conducted the database searches independently between 1st and 23rd June 2022. Relevant studies were identified using electronic database searches of PubMed, Embase, and PsychInfo, as well as the citation lists of any provisionally included material, and in addition to the studies which cited them. The following search terms were used: depression, major depressive disorder, major depressive episode, depressive symptoms, bipolar, bipolar disorder, mania, manic symptoms, hypomania, hypomanic symptoms, anxiety, anxiety disorder, LGBTIQIA+, LGBTIQ+, LGBT+, LGBT, homosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, intersex, and asexual, pansexual, prevalence, experience. The search string used is available in supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 2). As homosexuality had been declassified as an independent mental disorder in both the DSM and ICD by 1990, only studies published between 1990 and 23rd June 2022 were extracted. In addition, conference proceedings from 2012–2022 were screened for relevance from the following sources: British Psychological Society, Royal College of Psychiatrists, American Psychiatric Association, Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing, American Psychological Association, Association of LGBTIQ Psychiatrists, Stonewall, World Health Organization, International Society for Affective Disorders, and International Society for Bipolar Disorders.

SJ and OP independently identified and compiled articles identified in searches using Rayyan (13). De-duplication was conducted separately by each researcher, first by using Rayyan’s de-duplication function and then by the reviewers manually screening articles. After de-duplication, titles and abstracts were evaluated for inclusion using the predetermined criteria. Disagreements were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Reference lists of provisionally included studies were reviewed for relevant parent studies. Additionally, records that had cited the included studies were reviewed for relevance. Researchers then screened abstracts of any selected articles discovered during forwards or backwards searches. The reviewers collaborated and finalized the inclusion list together (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data extraction was performed by SJ and OP, compiling the following information: title, first author, date of publication, research design, sample size, participant selection method, NIH quality rating, age range of participants, country of participant origin, participant gender identity, participant sexual identity, number of participants with depressive, bipolar, and/or anxiety disorders, the proportion of participants with depressive, bipolar, and/or anxiety disorders, the implemented diagnostic criteria, severity of disorder(s), presence (or lack thereof) of psychosis, scores of psychiatric tests, and any additional notes. SJ checked the accuracy of extracted data, manually calculating missing data where possible. Extracted data was collated into Microsoft Excel and are summarised in Supplementary Table 3. Studies with missing or derived data are shown in Supplementary Table 4 and solutions employed in Supplementary Table 5.

Societal acceptance of LGBTIQ+ people, measured using the GAI (10), was identified for each country that provided prevalence data. Comparative general population prevalence figures were sourced from Global Disease Burden research (14).

Study risk of bias assessment

The National Institute of Health (NIH) study quality assessment checklist (15) was used to assess the risk of bias in studies. OP and SJ evaluated each included study using 14 criteria to assign an overall rating of ‘good’, ‘fair’, or ‘poor’ for each study. The two raters completed the checklist independently before comparing results. The NIH study quality assessment checklist questions used can be found in Supplementary Table 6.

Statistical analysis

Sexual and gender identities were assessed at the nominal categorical level. Prevalence rates were assessed as numerical continuous data, considered as the number or proportion of participants with a disorder, expressed as a percentage. If no percentage was reported, it was calculated manually from available data. Confidence intervals of 95% were used in all analyses and where possible, bootstrapping was performed at 1,000 samples. SPSS Version 28.0.1.1 was used for all analysis tasks.

Ethical considerations

No ethical consideration or approval was required as this was a systematic review of the published evidence base.

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 details the PRISMA flow diagram for the identification and inclusion of the studies included in this review and the PRISMA checklist can be found in supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 1). 123 studies (16–138) were included in the review, representing data from 31 countries. 110 studies were used in analyses of the prevalence of depressive disorders, 22 in analyses of bipolar disorders, and 77 in analyses of anxiety disorders. A description of the studies included in this systematic review, including the quality assessment, their geographical location, sample size and LGBTIQ+ population investigated, can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Worldwide prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people

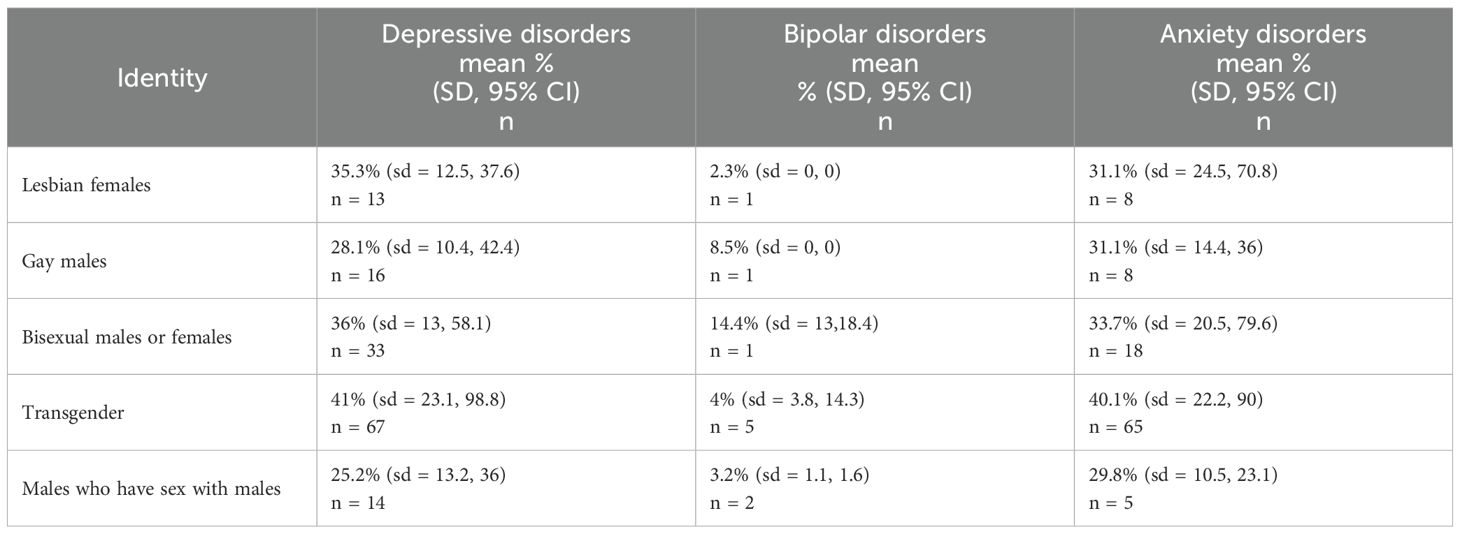

We found that LGBTIQ+ individuals experience depressive disorders at a mean rate of 35.3%, bipolar disorders at a mean rate of 5.6%, and anxiety disorders at a mean rate of 34.3% (Table 1). These rates are representative of the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in individuals of any combination of gender and sexual identities. Prevalence rates were 8–11 times higher than those reported in the general population (see Table 1). Meta-analyses were not conducted due to differences in study methodologies and a noted lack of use of comparator group in selected studies.

Table 1. Worldwide prevalence of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations compared to the general population.

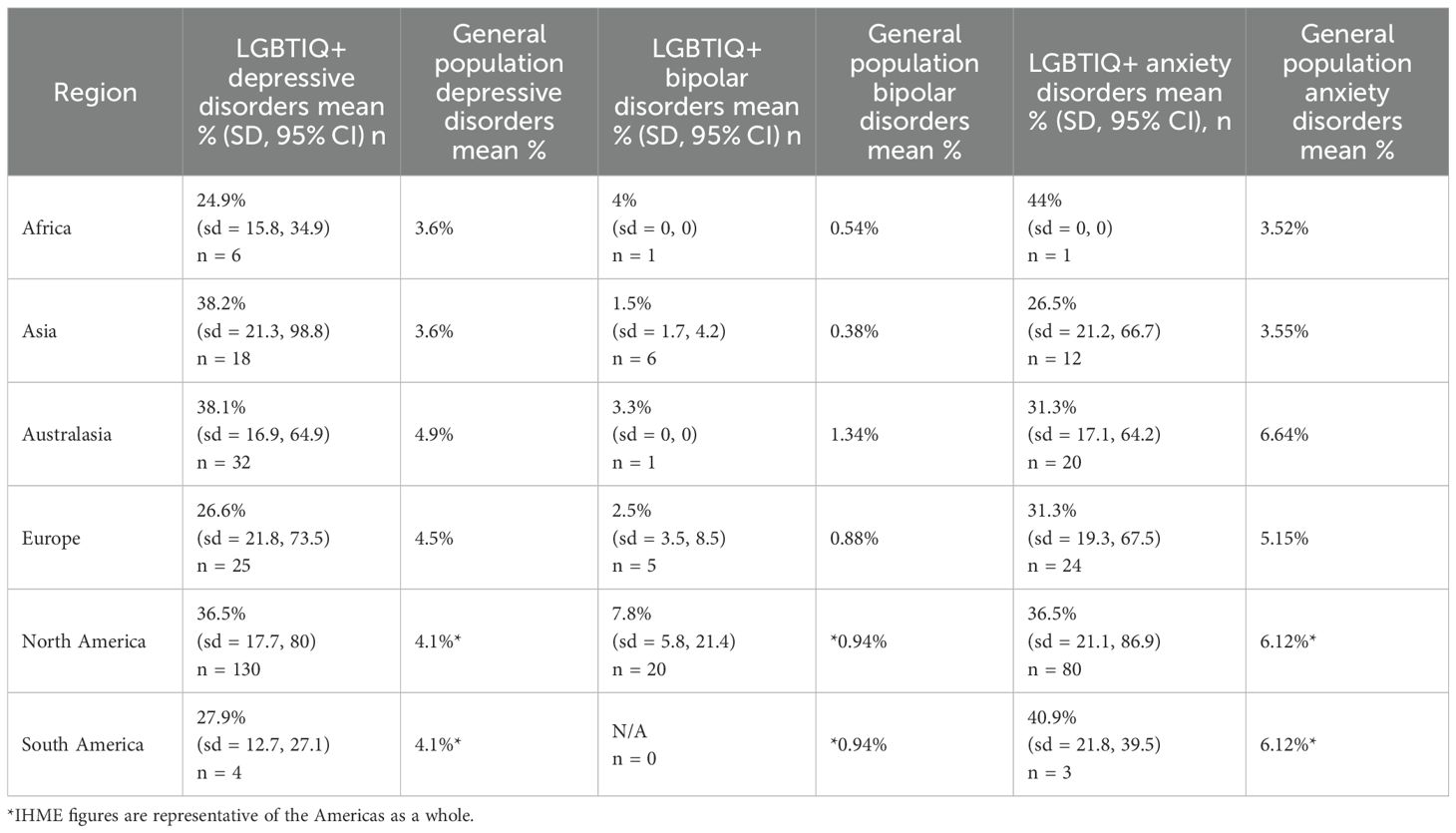

Regional prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people

Prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people varied depending on continent (see Table 2). Where multiple studies were available, the highest prevalence rates of depressive disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations were in Asia, the highest prevalence rates of bipolar disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations were in North America, and the highest prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations were in South America. There were relatively few studies investigating the prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people published from African or South American countries.

Table 2. Regional prevalence of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations compared to the general population.

Prevalence by LGBTIQ+ subgroup

This analysis investigated the prevalence of affective disorders in populations of lesbians, gay males, bisexuals (females and males), transgender people (both binary and nonbinary-identified individuals) and males who have sex with males (see Table 3). Results of the analysis indicated the highest prevalence of both depressive and anxiety disorders was in transgender people. Bisexual people were found to have the highest prevalence of bipolar disorders, but this finding may be affected by how few studies exist and the small number of participants in the available studies. Conversely, males who have sex with males were found to have the lowest prevalence of both depressive and anxiety disorders, while lesbian females the lowest prevalence of bipolar disorders.

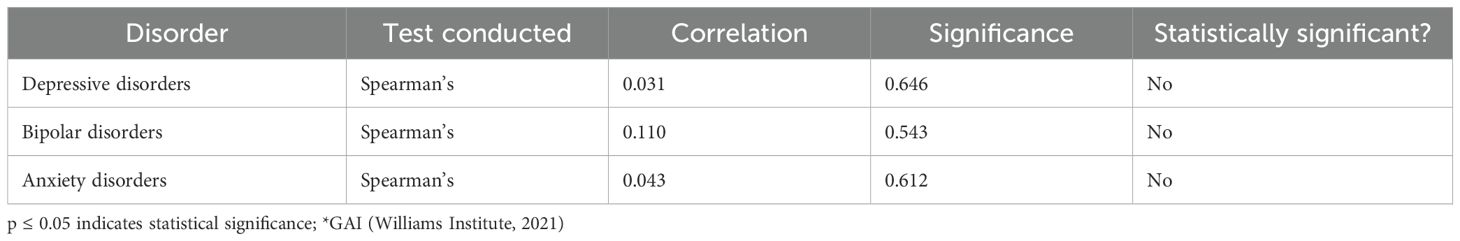

Relationship between prevalence rates and GAI scores

Taking together the studies included in this review from a variety of countries and regions, we did not find a statistically significant relationship between the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders globally and GAI (10) equality/acceptance ratings (see Table 4). Examining this relationship on a regional level, there was a significant correlation in North American LGBTIQ+ populations between GAI (10) equality/acceptance ratings and the prevalence of depressive (rs=0.3 p <0.001) and anxiety disorders (rs=0.26 p <0.017) but no significant correlations in other regions (see Table 5).

Table 4. Correlations between worldwide prevalence rates of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations and GAI* acceptance/equality scores.

Table 5. Correlations between regional rates of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations and GAI* acceptance/equality scores.

Quality assessment of included studies

116 studies were rated as ‘good’ and seven were assessed as ‘fair’. No studies were rated as ‘poor’ quality. These are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we found markedly higher prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people compared to the overall general population. Globally, we found that LGBTIQ+ people experienced an 8-11-fold higher prevalence rate of depressive disorders, bipolar disorders and anxiety disorders compared to the general population. This pattern of increased prevalence occurred irrespective of continent. We found that rates of depressive disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations were 6–11 times higher across continents. In continents where multiple studies were available, rates of bipolar disorders in Asian, European and North American LGBTIQ+ populations were 3–8 times higher, and rates of anxiety disorders in Asian, Australasian, European, North and South American LGBTIQ+ populations were 5–7 times higher. These findings need to be considered in the context of over-representation of studies from North America, and a relative lack of studies from Africa and South America, together with the under representation of certain diagnostic categories and sexual identities.

There did not seem to be a great difference in the prevalence rates of depressive or anxiety disorders between LGBTIQ+ communities, for example, between gay males and lesbian females, although rates did seem to be comparatively higher in transgender people. There was more variation in the prevalence rates of bipolar disorders across LGBTIQ+ groups, which may reflect the small number of studies available.

Given how common lived experiences of homophobia, heteronormativity, rejection by family and friends, discrimination, and victimization due to LGBTIQ+ status are (7–9, 19) higher prevalence rates of depressive (35.5% v. 3.8%), bipolar (5.6% v. 0.5%) and anxiety (34.3% v. 4.1%) disorders were not unexpected. However, we were surprised at how much higher the prevalence rates we found in our review were compared to the general population. This is an important finding and underlines the public health importance of providing LGBTIQ+ informed mental healthcare to LGBTIQ+ people with, and at risk for developing, mood and anxiety disorders.

The correlations between Global Acceptance Index scores (10) and depressive and anxiety disorders in North America were the only statistically significant correlations found, and they were unexpectedly positive. This positive correlation might indicate that relative social acceptance, the metric measured by the GAI, is not a large contributor to the diagnosis of depressive and/or anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ individuals outside of North America. Further examination into alternative factors for the development of mood disorders in LGBTIQ+ people is needed. With that said, because the North American continent was so over-represented relative to other regions in these analyses, the results found for North America may be more sensitive than those for other, less represented areas.

Overall, all studies included in the review, regardless of their country of origin, were of good or fair quality.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this systematic review include the availability of research studies for inclusion in analysis, the wide geographical spread of these studies and the representation of transgender people in the research identified. High quality research was found to be available from all six inhabited continents, making the review worldwide in scope. Moreover, changing attitudes about sexual and gender minority identity, as well as mental health conditions, have allowed more people to participate openly in this kind of research. Transgender individuals, and their mental health, have been studied extensively as of late, offering a range of information upon which to build statistical analyses.

Along with strengths, there are a number of limitations to consider. A limitation of the evidence base was that there was a comparative lack of studies of mood and anxiety disorder prevalence rates in gay males and lesbian females compared to bisexual and transgender people. We did not identify any studies investigating mood and anxiety prevalence rates in participants with less common identities, including pansexual, omnisexual, demisexual, asexual, nonbinary, genderqueer/genderfluid, and agender (15). Such individuals are minorities in the LGBTIQ+ population and merging diverse identities into a single LGBTIQ+ category may mask mental health challenges unique to specific LGBTIQ+ identities. There was also a relative lack of studies investigating the prevalence of bipolar disorders in LGBTIQ+ people, and the prevalence of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations in Africa and South America. The severity of mood and anxiety disorders was also not measured by most studies and so the degree of impairment associated with these disorders experienced by LGBTIQ+ people is hard to assess.

Limitations of the review were that only studies published in, or translated to, English were included; and that some of the included studies did not necessarily report the period over which they measured prevalence rates and so we could not specify our prevalence estimates to a specific time periods.

Implications and future research

This systematic review highlights the continuing need for sexual and/or gender-identity affirmative mental healthcare worldwide to tackle the higher prevalence rates of affective disorders we identified in LGBTIQ+ people. Affirmative and culturally competent mental healthcare could be key in the improvement and protection of mental health in LGBTIQ+ people, possibly serving as protective factors against both environmental and internal experiences of homophobia, heteronormativity and stigma.

We would suggest that future research particularly investigates the prevalence of bipolar disorders in LGBTIQ+ people as there is a relative lack of research in this area. Furthermore, as current research has tended towards examining mood and anxiety disorder prevalence rates in bisexual and transgender people, it would be beneficial to conduct further studies focusing on prevalence rates in lesbian females and gay males in order to provide an updated comparison. Finally, more research is needed exploring the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in less common LGBTIQ+ identities.

Conclusions

We identified that mood and anxiety disorder prevalence rates are 8- to 11-fold higher in LGBTIQ+ people compared to the general population, indicating the need for better preventative mental health interventions. We found a relative lack of studies in bipolar disorders, gay males, lesbian females and other individuals identifying as LGBTIQ+, and in LGBTIQ+ populations in Africa and South America. Our study suggests that the proactive prevention and treatment of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ populations is important and calls for further work exploring factors influencing prevalence rates of affective disorders in LGBTIQ+ communities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LA: Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. MB was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MR/W006820/1) and King’s College London member of the MRC Doctoral Training Partnership in Biomedical Sciences. LA was supported by an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow award in Translational Psychiatry (ACF-2022-17-016).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Olivia Perren (OP) who contributed to developing the search protocol, conducting the review search process and extracting data, and writing initial drafts of the introduction.

Conflict of interest

PS reports grant funding from the Medical Research Council UK, National Institute for Health and Care Research NIHR, H. Lundbeck A/S and King’s Health Partners, funding from NIHR, non-financial support from Janssen Research and Development LLC for an MRC funded study led by PS, editorial honoraria and non-financial support from Frontiers in Psychiatry outside the submitted work. PS is a member of the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs ACMD, and Speciality Chief Editor, Mood Disorders section, Frontiers in Psychiatry.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1662265/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Meyer IH. Prejudice and discrimination as social stressors. In: The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. Boston, MA: Springer (2007). p. 242–67. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4_10

2. Pakula B and Shoveller JA. Sexual orientation and self-reported mood disorder diagnosis among Canadian adults. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-209

3. Harvard Medical School. National comorbidity survey (NCS) (2017). Available online at: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php (Accessed November 22, 2022).

4. Wichaidit W, Assanangkornchai S, and Chongsuvivatwong V. Disparities in behavioral health and experience of violence between cisgender and transgender Thai adolescents. PloS One. (2021) 16:252520. doi: 10.1374/journal.pone.0252520

5. Shrestha M, Boonmongkon P, Peerawaranun P, Samoh N, Kanchawee K, and Guadamuz TE. Revisiting the ‘Thai gay paradise’: negative attitudes toward same-sex relations despite sexuality education among Thai LGBT students. Global Public Health. (2020) 15:414–23. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1684541

7. Rudert SC, Janke S, and Greifeneder R. Ostracism breeds depression: Longitudinal associations between ostracism and depression over a three-year-period. J Affect Disord Rep. (2021) 4:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100118

8. Husain-Krautter S. A brief discussion on mood disorders in the LGBT population. Am J Psychiatry Residents’ J. (2017) 12:10–1. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2017.120505

9. Liu RT, Sheehan AE, Walsh RF, Sanzari CM, Cheek SM, and Hernandez EM. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2019) 74:101783. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783

10. Flores AR. Social acceptance of LGBTI people in 175 countries and locations (2021). Available online at: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Global-Acceptance-Index-LGBTI-Nov-2021.pdf (Accessed October 26, 2022).

11. Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, and Catalan J. HIV and depression–a systematic review of interventions. Psychology Health Med. (2011) 16:493–527. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579990

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, and Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71109

13. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, and Elmagarmid A. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Rev. (2016) 5. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

14. Global burden of disease study 2019 results . Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available online at: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (Accessed September 2, 2024).

15. Study quality assessment tools . NHLBI, NIH. Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (Accessed September 2, 2024).

16. Ahaneku H, Ross MW, Nyoni JE, Selwyn B, Troisi C, Mbwambo J, et al. Depression and HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Tanzania. AIDS Care. (2016) 1:140–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1146207

17. Alibudbud RC. Does sexual orientation matter?": A comparative analysis of the prevalence and determinants of depression and anxiety among heterosexual and non-heterosexual college students in a university in metro Manila. J Homosexuality. (2021) 70(6):1–19. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.2015953

18. Atteberry-Ash B, Kattari SK, Harner V, Prince DM, Verdino AP, Kattari L, et al. Differential experiences of mental health among transgender and gender-diverse youth in Colorado. Behavioral Sciences (2021) 11:48. doi: 10.3390/bs11040048

19. Barnhill MM, Lee J, and Rafferty AP. Health inequities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in North Carolina, 2011-2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 17:17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080835

20. Başar K and Öz G. Resilience in individuals with gender dysphoria: Association with perceived social support and discrimination. Turkish J Psychiatry. (2016) 27:225–34. doi: 10.5080/u17071

21. Batchelder AW, Stanton AM, Kirakosian N, King D, Grasso C, Potter J, et al. Mental health and substance use diagnoses and treatment disparities by sexual orientation and gender in a community health center sample. LGBT Health. (2021) 8:290–9. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0293

22. Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, Cromwell L, Flanders WD, Getahun D, et al. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. (2018) 141:20173845. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3845

23. Beckwith N, McDowell MJ, Reisner SL, Zaslow S, Weiss RD, Mayer KH, et al. Psychiatric epidemiology of transgender and nonbinary adult patients at an urban health center. LGBT Health. (2019) 6:51–61. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0136

24. Berg MB, Mimiaga MJ, and Safren SA. Mental health concerns of gay and bisexual men seeking mental health services. J Homosexuality. (2008) 54:293–306. doi: 10.1080/00918360801982215

25. Bergero-Miguel T, García-Encinas MA, Villena-Jimena A, Pérez-Costillas L, Sánchez-Álvarez N, De Diego-Otero Y, et al. Gender dysphoria and social anxiety: an exploratory study in Spain. J Sexual Med. (2016) 13:1270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.05.009

26. Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Andersson G, Cochran S, and Kosidou K. Anxiety and depression among sexual minority women and men in Sweden: Is the risk equally spread within the sexual minority population? J Sexual Med. (2017) 14:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.012

27. Blashill AJ and Calzo JP. Sexual minority children: Mood disorders and suicidality disparities. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:96–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.040

28. Bolton SL and Sareen J. Sexual orientation and its relation to mental disorders and suicide attempts: findings from a nationally representative sample. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. (2011) 56:35–43. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600107

29. Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, and McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:468–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942

30. Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, and Everett B. Health behavior, status, and outcomes among a community-based sample of lesbian and bisexual women. LGBT Health. (2015) 2:121–6. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0074

31. Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, Crawford JR, Millet N, Fernandez-Aranda F, et al. Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int J Transgenderism. (2017) 18:16–26. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1258352

32. Budge SL, Adelson JL, and Howard KA. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J Consulting Clin Psychol. (2013) 81:545–57. doi: 10.1037/a0031774

33. Burns MN, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Newcomb ME, and Mustanski B. Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018

34. Castelo-Branco C, Ribera-Torres L, Gómez-Gil E, Uribe C, and Cañizares S. Psychopathological symptoms in Spanish subjects with gender dysphoria. A Cross-Sectional Study. Gynecological Endocrinol. (2021) 37:534–40. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2021.1913113

35. Chakraborty A, McManus S, Brugha TS, Bebbington P, and King M. Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. Br J Psychiatry: J Ment Sci. (2011) 198:143–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082271

36. Chaudhry AB and Reisner SL. Disparities by sexual orientation persist for major depressive episode and substance abuse or dependence: Findings from a national probability study of adults in the United States. LGBT Health. (2019) 6:261–6. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0207

37. Cheung AS, Ooi O, Davidoff D, Bretherton I, Grossmann M, and Zajac JD. Clinical characteristics of trans and gender diverse individuals attending specialist endocrinology clinics. Clin Endocrinol. (2018) 89:57–8. doi: 10.1111/cen.13727

38. Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, Denny SJ, Fleming TM, Robinson EM, et al. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12. J Adolesc Health. (2014) 55:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008

39. Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, and Mays VM. Sexual orientation differences in functional limitations, disability, and mental health services use: Results from the 2013–2014 National Health Interview Survey. J Consulting Clin Psychol. (2017) 85:1111–21. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000243

40. Cochran SD and Mays VM. Depressive distress among homosexually active African American men and women. Am J Psychiatry. (1994) 151:524–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.524

41. Cochran SD and Mays VM. Lifetime prevalence of suicide symptoms and affective disorders among men reporting same-sex sexual partners: results from NHANES III. Am J Public Health. (2000) 90:573–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.573

42. Cochran SD and Mays VM. Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. J Abnormal Psychol. (2009) 118:647–58. doi: 10.1037/a0016501

43. Cochran SD, Mays VM, Alegria M, Ortega AN, and Takeuchi D. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consulting Clin Psychol. (2007) 75:785–94. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785

44. Cohen JM, Blasey C, Barr Taylor C, Weiss BJ, and Newman MG. Anxiety and related disorders and concealment in sexual minority young adults. Behav Ther. (2016) 47:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.09.006

45. Durwood L, McLaughlin KA, and Olson KR. Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2017) 56:116–123 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.016

46. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, and Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1999) 56:876–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876

47. Ferlatte O, Salway T, Rice SM, Oliffe JL, Knight R, and Ogrodniczuk JS. Inequities in depression within a population of sexual and gender minorities. J Ment Health (Abingdon. (2020) 29:573–80. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1581345

48. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Kim HJ, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, et al. The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: the role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. Gerontologist. (2013) 53:664–75. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns123

49. Galea J, Marhefka S, León SR, Rahill G, Cyrus E, Sánchez H, et al. High levels of mild to moderate depression among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Lima, Peru: implications for integrated depression and HIV care. AIDS Care. (2021) 34(12):1–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2021.1991877

50. Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, and Kessler RC. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. (2001) 91:933–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.933

51. Gómez-Gil E, Trilla A, Salamero M, Godás T, and Valdés M. Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychiatric characteristics of transsexuals from Spain. Arch Sexual Behav. (2009) 38:378–92. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9307-8

52. Gómez-Gil E, Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Esteva I, Guillamon A, Godás T, Cruz Almaraz M, et al. Hormone-treated transsexuals report less social distress, anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2012) 37:662–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.010

53. Gonzales G and Henning-Smith C. Health disparities by sexual orientation: Results and implications from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Community Health. (2017) 42:1163–72. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0366-z

54. Grabovac I, Smith L, McDermott DT, Stefanac S, Yang L, Veronese N, et al. Well-being among older gay and bisexual men and women in England: A cross-sectional population study. J Am Med Directors’ Assoc. (2019) 20:1080–1085 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.119

55. Hanna B, Desai R, Parekh T, Guirguis E, Kumar G, and Sachdeva R. Psychiatric disorders in the U.S. transgender population. Ann Epidemiol. (2019) 39:1–7 1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.09.009

56. Hepp U, Kraemer B, Schnyder U, Miller N, and Delsignore A. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder. J Psychosomatic Res. (2005) 58:259–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.010

57. Hershner S, Jansen EC, Gavidia R, Matlen L, Hoban M, and Dunietz GL. Associations between transgender identity, sleep, mental health and suicidality among a North American cohort of college students. Nat Sci Sleep. (2021) 13:383–98. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S286131

58. Heylens G, Elaut E, Kreukels BP, Paap MC, Cerwenka S, Richter-Appelt H, et al. Psychiatric characteristics in transsexual individuals: multicentre study in four European countries. Br J 61. Psychiatry: J Ment Sci. (2014) 204:151–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.121954

59. Hickson F, Davey C, Reid D, Weatherburn P, and Bourne A. Mental health inequalities among gay and bisexual men in England, Scotland and Wales: a large community-based cross-sectional survey. J Public Health (Oxford. (2017) 39:266–73. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw021

60. Hoshiai M, Matsumoto Y, Sato T, Ohnishi M, Okabe N, Kishimoto Y, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity among patients with gender identity disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2010) 64:514–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02118.x

61. Hoy-Ellis CP and Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Depression among transgender older adults: General and minority stress. Am J Community Psychol. (2017) 59:295–305. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12138

62. Hyde Z, Doherty M, Tilley PJ, Mccaul K, Rooney R, and Jancey J. The first Australian national trans mental health study: summary of results. (2015).

63. James HA, Chang AY, Imhof RL, Sahoo A, Montenegro MM, Imhof NR, et al. A community-based study of demographics, medical and psychiatric conditions, and gender dysphoria/incongruence treatment in transgender/gender diverse individuals. Biol Sex Dif. (2020) 11:55. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00332-5

64. Janković J, Slijepčević V, and Miletić V. Depression and suicidal behavior in LGB and heterosexual populations in Serbia and their differences: Cross-sectional study. PloS One. (2020) 15:234188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234188

65. Kalibatseva Z, Bathje GJ, Wu I, Bluestein BM, Leong F, and Collins-Eaglin J. Minority status, depression and suicidality among counseling center clients. J Am Coll. (2022) 70(1):295–304. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1745810

66. Kattari SK, Kattari L, Johnson I, Lacombe-Duncan A, and Misiolek BA. Differential experiences of mental health among trans/gender diverse adults in Michigan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6805. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186805

67. Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2017) 170:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.03

68. Khorashad BS, Talaei A, Aghili Z, and Arabi A. Psychiatric morbidity among adult transgender people in Iran. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 142:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.035

69. Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Weiss G, Wong C, Lopez D, Iverson E, et al. The health and health behaviors of young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. (2007) 40:342–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.019

70. Konrad M and Kostev K. Increased prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment and somatoform disorders in transsexual individuals. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:482–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.074

71. Kunzweiler CP, Bailey RC, Okall DO, Graham SM, Mehta SD, and Otieno FO. Depressive symptoms, alcohol and drug use, and physical and sexual abuse among men who have sex with men in Kisumu, Kenya: The Anza Mapema study. AIDS Behav. (2018) 22:1517–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1941-0

72. Lachowsky NJ, Dulai JJ, Cui Z, Sereda P, Rich A, Patterson TL, et al. Lifetime doctor-diagnosed mental health conditions and current substance use among gay and bisexual men living in Vancouver, Canada. Subst Use Misuse. (2017) 52:785–97. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1264965

73. Lipson SK, Raifman J, Abelson S, and Reisner SL. Gender minority mental health in the U.S.: Results of a national survey on college campuses. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 57:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.025

74. Liu X and Jiang D. The characteristics of the vulnerable Chinese gay men with depression and anxiety: a cross-sectional study. J Men’s Health. (2022) 18:032. doi: 10.31083/jomh.2021.091

75. Liu X, Jiang D, Chen X, Tan A, Hou Y, He M, et al. Mental health status and associated contributing factors among gay men in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061065

76. López JD, Duncan A, Shacham E, and McKay V. Disparities in health behaviors and outcomes at the intersection of race and sexual identity among women: Results from the 2011–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prev Med. (2021) 142:106379. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106379

77. Lucassen M, Perry Y, Frampton C, Fleming T, Merry SN, Shepherd M, et al. Intersex adolescents seeking help for their depression: the case study of SPARX in New Zealand. Australas Psychiatry: Bull R Aust New Z Coll Psychiatrists. (2021) 29:450–3. doi: 10.1177/1039856221992642

78. Lucassen MF, Merry SN, Robinson EM, Denny S, Clark T, Ameratunga S, et al. Sexual attraction, depression, self-harm, suicidality and help-seeking behaviour in New Zealand secondary school students. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2011) 45:376–83. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.559635

79. Malta M, Jesus J, LeGrand S, Seixas M, Benevides B, Silva M, et al. ‘Our life is pointless… ‘: Exploring discrimination, violence and mental health challenges among sexual and gender minorities from Brazil. Global Public Health. (2020) 15:1463–78. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1767676

80. Mao L, Kidd MR, Rogers G, Andrews G, Newman CE, Booth A, et al. Social factors associated with major depressive disorder in homosexually active, gay men attending general practices in urban Australia. Aust New Z J Public Health. (2009) 33:83–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00344.x

81. Mazaheri Meybodi A, Hajebi A, and Ghanbari Jolfaei A. Psychiatric axis I comorbidities among patients with gender dysphoria. Psychiatry J. (2014), 971814. doi: 10.1155/2014/971814

82. McGarty A, McDaid L, Flowers P, Riddell J, Pachankis J, and Frankis J. Mental health, potential minority stressors and resilience: evidence from a cross-sectional survey of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men within the Celtic nations. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12030-x

83. McNair R, Kavanagh A, Agius P, and Tong B. The mental health status of young adult and mid-life non-heterosexual Australian women. Aust New Z J Public Health. (2005) 29:265–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00766.x

84. Meyer IH, Dietrich J, and Schwartz S. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and suicide attempts in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. (2008) 98:1004–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096826

85. Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang YJ, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:278–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278

86. Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, and Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:2426–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319

87. Nahata L, Quinn GP, Caltabellotta NM, and Tishelman AC. Mental health concerns and insurance denials among transgender adolescents. LGBT Health. (2017) 4:188–93. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0151

88. Nunes-Moreno M, Buchanan C, Cole FS, Davis S, Dempsey A, Dowshen N, et al. Behavioral health diagnoses in youth with gender dysphoria compared with controls: A PEDSnet study. J Pediatr. (2022) 241:147–153 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.09.032

89. Oginni OA, Mosaku KS, Mapayi BM, Akinsulore A, and Afolabi TO. Depression and associated factors among gay and heterosexual male university students in Nigeria. Arch Sexual Behav. (2018) 47:1119–32. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0987-4

90. Oswal R, Patel F, Rathor D, Dave K, and Mehta R. Depression and its correlates in men who have sex with men attending a community based organization. Int J Integrated Med Res. (2017) 4:1–5.

91. Oswalt S and Lederer A. Beyond depression and suicide: The mental health of transgender college students. Soc Sci. (2017) 6:20. doi: 10.3390/socsci6010020

92. Parodi KB, Holt MK, Green JG, Katz-Wise SL, Shah TN, Kraus AD, et al. Associations between school-related factors and mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth. J School Psychol. (2022) 90:135–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2021.11.004

93. Poguri M, Sarkar S, and Nambi S. A pilot study to assess emotional distress and quality of life among transgenders in South India. Neuropsychiatry. (2016) 6:22–7. doi: 10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000113

94. Prestage G, Hammoud M, Jin F, Degenhardt L, Bourne A, and Maher L. Mental health, drug use and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men. Int J Drug Policy. (2018) 55:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.01.020

95. Reis A, Sperandei S, Carvalho P, Pinheiro TF, Moura FD, Gomez JL, et al. A cross-sectional study of mental health and suicidality among trans women in São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:557. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03557-9

96. Reisner SL, Biello KB, White Hughto JM, Kuhns L, Mayer KH, Garofalo R, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and comorbidities in a diverse, multicity cohort of young transgender women: Baseline findings from Project LifeSkills. JAMA Pediatr. (2016) 170:481–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0067

97. Reisner SL and Hughto J. Comparing the health of non-binary and binary transgender adults in a statewide non-probability sample. PloS One. (2019) 14:221583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221583

98. Reisner SL, Katz-Wise SL, Gordon AR, Corliss HL, and Austin SB. Social epidemiology of depression and anxiety by gender identity. J Adolesc Health. (2016) 59:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.006

99. Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, et al. Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:274–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264

100. Rentería R, Benjet C, Gutiérrez-García RA, Abrego-Ramírez A, Albor Y, Borges G, et al. Prevalence of 12-month mental and substance use disorders in sexual minority college students in Mexico. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 56:247–57. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01943-4

101. Rice CE, Vasilenko SA, Fish JN, and Lanza ST. Sexual minority health disparities: an examination of age-related trends across adulthood in a national cross-sectional sample. Ann Epidemiol. (2019) 31:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.01.001

102. Rich AJ, Armstrong HL, Cui Z, Sereda P, Lachowsky NJ, Moore DM, et al. Sexual orientation measurement, bisexuality, and mental health in a sample of men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. J Bisexuality. (2018) 18:299–317. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2018.1518181

103. Rogers G, Curry M, Oddy J, Pratt N, Beilby J, and Wilkinson D. Depressive disorders and unprotected casual anal sex among Australian homosexually active men in primary care. HIV Med. (2003) 4:271–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00155.x

104. Rogers TL, Emanuel K, and Bradford J. Sexual minorities seeking services. J Lesbian Stud. (2003) 7:127–46. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_09

105. Rosenwohl-Mack A, Tamar-Mattis S, Baratz AB, Dalke KB, Ittelson A, Zieselman K, et al. A national study on the physical and mental health of intersex adults in the U.S. PloS One. (2020) 15:0240088–0240088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240088

106. Ross LE, Bauer GR, MacLeod MA, Robinson M, MacKay J, and Dobinson C. Mental health and substance use among bisexual youth and non-youth in Ontario, Canada. PloS One. (2014) 9:101604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101604

107. Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Travers R, Travers A, Scanlon K, and Kaay M. Depression in male-to-female transgender ontarians: Results from the trans PULSE project. Can J Community Ment Health. (2012) 30:113–33. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0020

108. Sandfort TG, Graaf R, Bijl RV, and Schnabel P. Same-sex sexual behavior and psychiatric disorders: findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2001) 58:85–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.85

109. Sandfort TG, Graaf R, Ten Have M, Ransome Y, and Schnabel P. Same-sex sexuality and psychiatric disorders in the second Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS-2. LGBT Health. (2014) 1:292–301. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0031

110. Scott RL, Lasiuk G, and Norris CM. Sexual orientation and depression in Canada. Can J Public Health. (2016) 107:545–9. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.107.5506110

111. Secor AM, Wahome E, Micheni M, Rao D, Simoni JM, Sanders EJ, et al. Depression, substance abuse and stigma among men who have sex with men in coastal Kenya. AIDS. (2015) 3:251–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000846

112. She J, McCall J, Pudwell J, Kielly M, and Waddington A. An assessment of the mental health history of patients in a transgender clinic in Kingston, Ontario. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. (2020) 65:281–3. doi: 10.1177/0706743719901245

113. Simenson AJ, Corey S, Markovic N, and Kinsky S. Disparities in chronic health outcomes and health behaviors between lesbian and heterosexual adult women in Pittsburgh: A longitudinal study. J Women’s Health. (2020) 29:1059–67. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8052

114. Sivasubramanian M, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Anand VR, Johnson CV, Prabhugate P, et al. Suicidality, clinical depression, and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in men who have sex with men in Mumbai, India: findings from a community-recruited sample. Psychology Health Med. (2011) 16:450–62. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.554645

115. Spittlehouse JK, Boden JM, and Horwood LJ. Sexual orientation and mental health over the life course in a birth cohort. psychol Med. (2020) 50:1348–55. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001284

116. Stahlman S, Grosso A, Ketende S, Sweitzer S, Mothopeng T, Taruberekera N, et al. Depression and social stigma among MSM in Lesotho: Implications for HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention. AIDS Behav. (2015) 19:1460–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1094-y

117. Stanton AM, Batchelder AW, Kirakosian N, Scholl J, King D, Grasso C, et al. Differences in mental health symptom severity and care engagement among transgender and gender diverse individuals: Findings from a large community health center. PloS One. (2021) 16:245872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245872

118. Steele LS, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Veldhuizen S, and Tinmouth JM. Women’s sexual orientation and health: results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women Health. (2009) 49:353–67. doi: 10.1080/03630240903238685

119. Stepelman LM, Yohannan J, Scott SM, Titus LL, Walker J, Lopez EJ, et al. Health needs and experiences of a LGBT population in Georgia and south carolina. J Homosexuality. (2019) 66:989–1013. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1490573

120. Stewart SL, Dyke JN, and Poss JW. Examining the mental health presentations of treatment-seeking transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2023) 54(3):826–836. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01289-1

121. Stoloff K, Joska JA, Feast D, Swardt G, Hugo J, Struthers H, et al. A description of common mental disorders in men who have sex with men (MSM) referred for assessment and intervention at an MSM clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. (2013) 17:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0430-3

122. Strauss P, Cook A, Winter S, Watson V, Wright Toussaint D, and Lin A. Associations between negative life experiences and the mental health of trans and gender diverse young people in Australia: findings from Trans Pathways. psychol Med. (2020) 50:808–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000643

123. Su D, Irwin JA, Fisher C, Ramos A, Kelley M, Mendoza D, et al. Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health. (2016) 1:12–20. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

124. Tan K, Ellis SJ, Schmidt JM, Byrne JL, and Veale JF. Mental health inequities among transgender people in aotearoa, New Zealand: Findings from the counting ourselves survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082862

125. Terra T, Schafer JL, Pan PM, Costa AB, Caye A, Gadelha A, et al. Mental health conditions in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and asexual youth in Brazil: A call for action. J Affect Disord. (2022) 298:190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.108

126. Thirunavukkarasu B, Khandekar J, Parasha M, Dhiman B, and Yadav K. Psychosocial health and its associated factors among men who have sex with men in India: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychiatry. (2021) 63:490–4. doi: 10.4103/Indianjpsychiatry.Indianjpsychiatry_18_21

127. Tomori C, McFall AM, Srikrishnan AK, Mehta SH, Solomon SS, Anand S, et al. Diverse rates of depression among men who have sex with men (MSM) across India: Insights from a multi-site. mixed method study. AIDS Behav. (2016) 20:304–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1201-0

128. Vargas SM, Sugarman OK, Tang L, Miranda J, and Chung B. Depression at the intersection of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and income. J Bisexuality. (2021) 21:541–59. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2021.2024932

129. Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, and Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. (2017) 60:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014

130. Wallien M, Swaab H, and Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity among children with gender identity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2007) 46:1307–14. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181373848

131. Wang J, Häusermann M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Aggleton P, and Weiss MG. High prevalence of mental disorders and comorbidity in the geneva gay men’s health study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2007) 42:414–20. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0190-3

132. Warne G, Grover S, Hutson J, Sinclair A, Metcalfe S, Northam E, et al. & Murdoch children’s research institute sex study group. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. (2005) 18:555–67. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.6.555

133. White YR, Barnaby L, Swaby A, and Sandfort T. Mental health needs of sexual minorities in Jamaica. Int J Sexual Health. (2010) 22:91–102. doi: 10.1080/19317611003648195

134. Williams CC, Curling D, Steele LS, Gibson MF, Daley A, Green DC, et al. Depression and discrimination in the lives of women, transgender and gender liminal people in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. (2017) 25:1139–50. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12414

135. Witcomb GL, Claes L, Bouman WP, Nixon E, Motmans J, and Arcelus J. Experiences and psychological wellbeing outcomes associated with bullying in treatment-seeking transgender and gender-diverse youth. LGBT Health. (2019) 6:216–26. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0179

136. Yi H, Lee H, Park J, Choi B, and Kim SS. Health disparities between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and the general population in South Korea: Rainbow Connection Project I. Epidemiol Health. (2017) 39:2017046. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017046

137. Yu L, Jiang C, Na J, Li N, Diao W, Gu Y, et al. Elevated 12-month and lifetime prevalence and comorbidity rates of mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders in Chinese men who have sex with men. PloS One. (2013) 8:50762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050762

Keywords: LGBTIQ+, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, global prevalence, systematic review

Citation: Johnson S, Bogdanova M, Alexander L and Stokes PRA (2025) Exploring the global prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in LGBTIQ+ people: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 16:1662265. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1662265

Received: 22 July 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025; Revised: 04 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Marina Miscioscia, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Lucas Bandinelli, University of Connecticut, United StatesAnja Lepach-Engelhardt, Private University of Applied Sciences, Germany

Patricia Joseph Kimong, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Teresa Graziano, University of Vermont, United States

Copyright © 2025 Johnson, Bogdanova, Alexander and Stokes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Johnson, c2pvaG5zb25tc2NAZ21haWwuY29t

Sarah Johnson

Sarah Johnson Mariia Bogdanova

Mariia Bogdanova Laith Alexander

Laith Alexander Paul R. A. Stokes

Paul R. A. Stokes