- 1Institute of Psychology, Humanitas University, Sosnowiec, Poland

- 2Prof. Department of Psychology of Emotion and Personality, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Lublin, Poland

Introduction: In addition to anxiety disorders and depressive symptoms, transgender people are also shown to have pathological personality profiles. These patterns are due to functioning under chronic stress, exposure to discrimination, victimization, the inability to affirm gender identity, and insufficient social support. The internalized transphobia predisposes transgender individuals to psychological decompensation. The study aims to assess Dark Personality Trait among transgender individuals and to establish the relationships between Dark Tetrad traits and resilience.

Materials and Methods: The Dark Tetrad (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, sadism) was assessed using The Short Dark Tetrad Scale (SD4-PL). Resilience was measured using The Resilience Measurement Scale (SPP-25) questionnaire. The dimensions of psychological resilience were also evaluated, including perseverance, determination in action, openness to new experiences, sense of humor, personal competence in coping, tolerance of negative emotions, tolerance for failure, viewing life as a challenge, optimism, and the ability to mobilize in difficult situations. In the statistical analysis, a Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted. Correlations between dark personality traits in the transgender and cisgender groups were compared using Fisher’s z-test.

Results: The study results indicate a slightly lower level of narcissism and Machiavellianism in transgender women compared with cisgender women, and a slightly increased level of sadism in all men, regardless of whether they are transgender or cisgender. No differences were observed between the transgender and cisgender groups in terms of dark personality traits. Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower level of general resilience than cisgender individuals.

Conclusions: The results of participants from the transgender group indicate lower level of dark personality traits. Observed differences in dark personality traits are related to gender and are independent of transgenderism. Psychological resilience provides a subtle protective function against the development of dark personality traits.

1 Introduction

Transgender individuals, as a sexual minority, experience discrimination and social prejudice, which leads to increased levels of stress that seriously affect their mental health, as well as causes psychological problems such as depressive and anxiety disorders (1–3).

Since the onset of identifying as transgender can usually be traced to adolescence or early adulthood, the personality traits that develop dynamically during this period may evolve as dysfunctional coping mechanisms. For example, transgender individuals may cope with severe gender dysphoria through social isolation, avoidance of close relationships, self-harm, outbursts of uncontrolled anger, or envy of the less problematic lives of others (4–9).

Over time, negative experiences of discrimination, harassment, and rejection by close ones generate the belief that transgender identity is impossible to accept and is invalidated. Chronic invalidation leads to self-invalidation, disrupting the process of self-acceptance (10–13).

Some researchers believe that transgender patients may present with various mental disorders (14), while others suggest that transgender identity is associated with personality disorders (15). In international studies, different personality scales have been used to understand the personality and psychological traits of transgender individuals. The results are inconsistent, which may be due to the small sample sizes (14–17).

Transgender identity is associated with internal, familial, occupational, social, financial, and health-related crises. The internal tension associated with the crises may occur on several levels. The first involves internal recognition of gender incongruence. Current societal norms, which assume cisgender identity as the default, necessitate the denial of cisgender identity in the process of recognizing one’s transgender identity. For this reason, the process of self-awareness regarding psychosexual identity in transgender individuals is often delayed (18, 19). The next problem generating stress and crisis is the act of coming out as transgender. Another stress-inducing process is undergoing gender transition (20). Health issues are primarily mental, although hormone therapy and various procedures undertaken to conceal external sexual characteristics that conflict with one’s experienced gender often carry adverse effects on physical health (21, 22).

There is some data in the literature, albeit not very extensive, pointing to pathological traits and/or personality profiles in transgender individuals (4, 23–26). The cross-sectional studies have evaluated prevalence estimates of personality pathology in the transgender population (17, 27, 28). Cluster B PDs and particularly borderline and narcissistic PDs, were identified as the most frequently diagnosed Axis II disorder in transgender people (29). Almost half of the included transgender clients exhibited at least one PD diagnosis (4). Therefore, we assume that differences between transgender and cisgender individuals may manifest in what are called dark personality traits, as there are gender differences in these traits. Dark personality traits include: Machiavellianism, sadism, psychopathy, and narcissism (30–35).

Machiavellianism is characterized by a focus on self-interest and the desire to achieve personal goals regardless of circumstances and at any cost. Numerous studies indicate that men score higher on Machiavellianism than women (36). In women, Machiavellianism is correlated with harm-avoidance, anxiety, and sensitivity or hypersensitivity. In men, it is associated with risk-taking, self-confidence, and an opportunistic worldview. Sex differences in Machiavellianism are explained by a theoretical perspective grounded in evolutionary theory. According to this view, sex differences in traits and values result from innate predispositions that developed in response to ancestral adaptive demands (37). Individuals can more freely express their internal tendencies, including those related to gender, if they have a sense of security provided by resource availability (36–38). By contrast, the socio-cultural perspective assumes that with greater gender equality, men are forced to compete not only with other men but also with women. This process is reflected in increases in Machiavellianism among men. At the same time, women derive greater benefits from increased gender equality and therefore need not rely to the same extent on Machiavellian strategies (39). In societies with greater gender equality, individuals tend to compare themselves across genders more frequently (36, 40). At the individual level, the apparent increase in the gender gap in Machiavellianism is driven by women’s reactions: women increasingly disapprove of Machiavellian tendencies in themselves, and consequently, Machiavellianism decreases among women, while remaining stable among men (36). The increase in resources available to women in countries with greater gender equality does not force women to compete for those resources. Consequently, women are not compelled to adopt Machiavellian strategies to achieve their goals. Women may more freely display characteristics associated with femininity that conflict with Machiavellian principles.

Another personality trait that manifests differently depending on the gender is narcissism. Differences in narcissism can be explained, among other factors, by reference to social roles. The level of narcissism is lower in women (41). Various behaviors observed in women are attributed to internal trait dispositions, which are then internalized as gender-typical traits, to which individuals compare their own behavior (3, 42). Narcissism involves agentic characteristics such as dominance and self-confidence; therefore, according to social role theory, this explains the higher level of narcissism in men (43–46). Men tend to exhibit lower levels of agreeableness, which is an antagonistic trait to narcissism (37, 41, 47). Women more often than men assume roles and work in occupations that promote high agreeableness, for example, nursing, teaching, and childcare. Gender-dependent socialization experiences may influence the level of narcissism and its antagonistic trait, agreeableness (48).

Sadism, in turn, has been the least extensively studied compared to other dark personality traits. It appears to be conditioned by environmental factors such as avoidant attachment patterns, exposure to domestic violence, and negative parenting styles (49, 50). This trait seems to function as an adaptation to the conditions transgender individuals live in. In this sense, it serves as a way to ensure dominance, protection, and control in hostile, violent environments (50, 51). From an evolutionary perspective, these traits, commonly perceived as negative, may be interpreted as adaptive responses to hostile, violent environments. In such environments, survival and competition for resources require the development of specific behavioral strategies. Adverse childhood experiences, which transgender individuals often encounter during this developmental stage, constitute critical events that influence the development of personality traits, including dark personality traits (23, 52–55). Psychological aggression is likely the strongest predictor of tendencies toward behaviors generally defined as sadism, and more precisely, behaviors based on exerting control over others. Aggressive behaviors experienced are internalized as a way of establishing dominance.

Justification of the role of psychological resources as resilience in our study on the personality traits of transgender individuals is of great importance, as personality pathology may affect the clinical symptoms of gender dysphoria (56). A precise understanding of the personality functioning of transgender individuals, determination of identity stability, self-regulation, and interpersonal relationships are important prognostic indicators that may help identify deficits and resources that should be considered in the transition process. Mental health problems are a significant, sometimes primary and at other times secondary, source of stress and may complicate the process of exploring gender identity and coping with gender dysphoria (57, 58). For example, symptoms of dysfunctional personality traits may lead to reduced adherence to medical and therapeutic recommendations, which require meticulous and regular engagement, while simultaneously disturbing the already challenging transition process.

Clinical consultations with transgender individuals should focus on psychological development, with particular attention to personality development. This study aims to enhance understanding of transgender individuals, mitigate discrimination and prejudice, and underscore the importance of building a supportive environment. Furthermore, the results may help create personalized treatment and psychological support plans for transgender individuals, thereby helping them cope with difficulties and improving their mental health and quality of life.

In a comprehensive analysis of health processes, we use knowledge of human resources and deficits as well as their environment. The context of environmental influences and individual traits in specific situations may support or hinder the process of meeting needs, fulfilling life tasks, and achieving goals. Resources and risk factors constitute the context conditioning the adaptation process (59–63). Key resources include psychological resilience, which conditions adaptive coping with stress experienced by transgender individuals. In our study, we decided to focus on resilience, considered an important individual resource, as well as personality traits that may represent a risk factor hindering the adaptation process, necessary during gender transition. Of particular importance for transgender individuals appears to be the general level of psychological resilience and its two aspects, perseverance and determination in action, and an optimistic outlook on life, with the ability to mobilize in difficult situations. At the same time, we chose not to control the level of minority stress in our study, as numerous reports confirm the presence of high levels of minority stress among transgender individuals (24, 64–67).

2 The current study

Taking into account the above-described findings presenting transgender people as characterized by pathological personality traits, first, we aim to assess the potential differences between transgender and cisgender individuals in terms of both dark personality traits. Second, we aim to identify the relationships between psychological resilience and dark personality traits such as sadism, psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism representing the Dark Personality Tetrad, in transgender men and women. We hypothesize that there are differences between transgender and cisgender people and that gender differences can play an important role in this differentiation. We consider resilience as an important covariant, as resilience can be a protective factor during the development of dark personality traits.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants

The study involved 242 participants. The sample was divided into two groups, clinical and control. The clinical group comprised 104 transgender respondents, while the control group included 138 cisgender individuals. Cisgender identity was determined based on anonymous self-identification by the participants. The control group was selected for the study according to gender. The control group was selected at random. The gender imbalance in the group of transgender individuals (77% men, 23% women) results from the predominance of transgender men in the general transgender population and the lack of access to transgender women. The problem of gender imbalance in studies of transgender individuals is a common issue in research on this group. This may distort study results, and we should be aware of this imbalance (68). However, in pour study the clinical group and control group were matched in term of gender. The age of transgender participants ranged from 18 to 52 years (M = 25.32; SD = 7.65). The age of cisgender participants ranged from 18 to 58 years (M = 34.35; SD = 10.13).

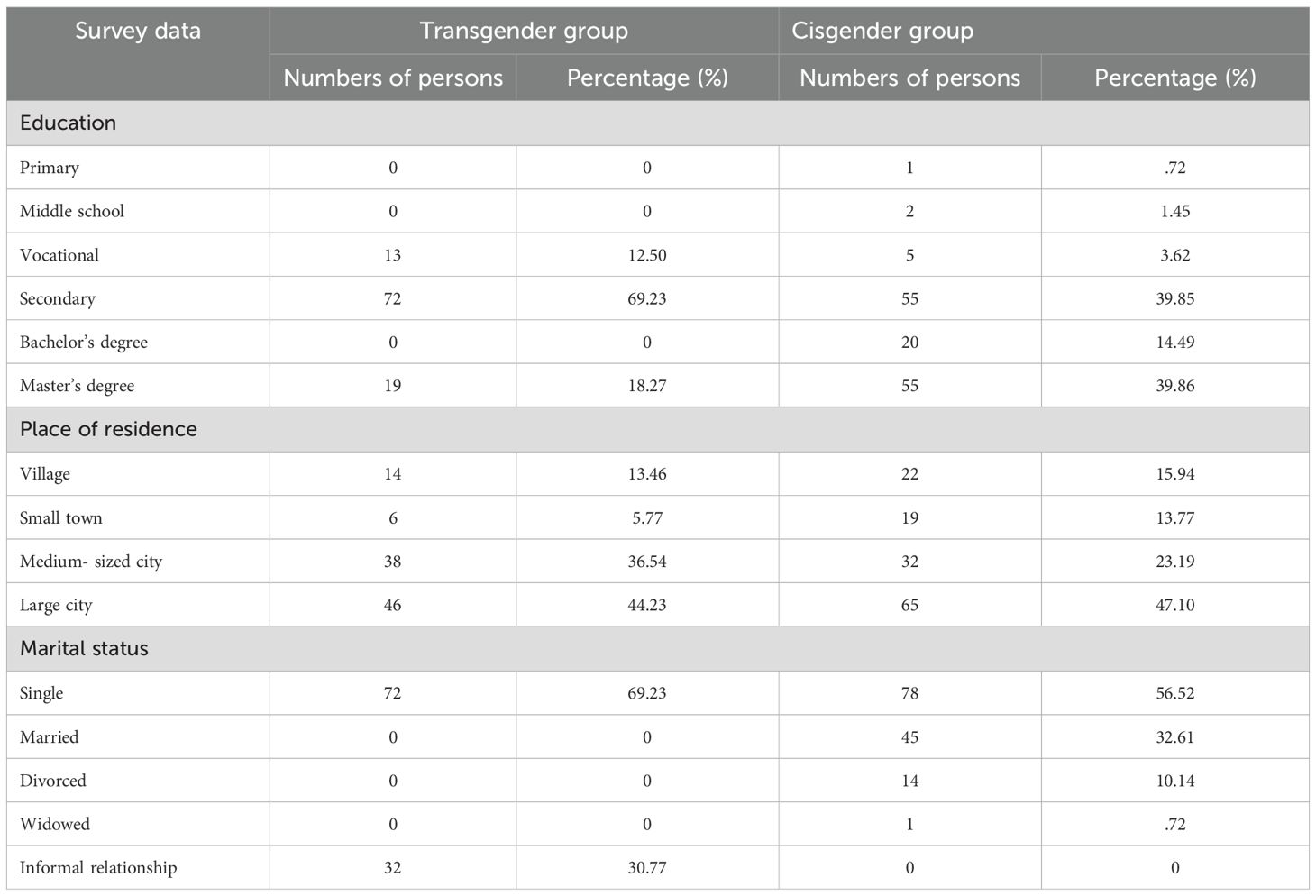

Sociodemographic data information collected through the survey are presented in Table 1.

3.2 Procedure

Recruitment of individuals for the clinical group was conducted among patients undergoing psychological evaluation as part of the gender transition process at the Rehabilitation and Medical Center Fizjomedica in Tychy, Poland. All transgender patients had been referred to the clinic by a sexologist overseeing their transition process, which allows the assumption that their transgender identity had been professionally confirmed. The group of transgender individuals is a clinical group, as it included persons undergoing the gender transition process and therefore subjected, among others, to psychological, psychiatric, endocrine, and neuroimaging assessments. The inclusion criteria were as follows: meeting the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for “transsexualism”, being at least 18 years of age, participation in the gender transition process before legal gender change, voluntary participation in the study. The exclusion criterion was a self-declared non-binary identity (14 individuals were excluded from the study on this basis). The proportions of women and men in both groups are the same.

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were informed of this both prior to the study and through a notice included at the beginning of each questionnaire. The study was conducted individually with each participant. Completing the questionnaire, which included socio-demographic data and psychometric instruments, took approximately 15 minutes.

The study was submitted to and received a favorable recommendation from the Research Ethics Committee of the Humanitas University (Poland, Sosnowiec; Opinion no. 4/2025).

3.3 Measures

The study assessed variables comprising the Dark Personality Tetrad (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, sadism), as well as the overall level of psychological resilience and its specific components.

Measurements were obtained using the following psychological instruments:

The Resilience Measurement Scale (SPP-25) (69) and the Short Dark Tetrad Scale (SD4) (70). Both questionnaires have demonstrated strong psychometric properties. An original survey questionnaire was also used to characterize the clinical and control groups. Within this survey, participants responded to questions regarding gender, age, education, place of residence, marital status, presence of illness, and medication use.

The SD4 measures antisocial personality traits, including Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism (70). SD4-PL is the Polish adaptation of the Short Dark Tetrad (SD4) questionnaire developed by D.L. Paulhus, E.E. Buckels, P.D. Trapnell, and D.N. Jones. The Polish version was adapted by P. Debski, P. Palczynski, M. Garczarczyk, M. Piankowska, K. Haratyk, and M. Meisner (71). The Polish version of SD4 is currently undergoing psychometric testing. The SD4-PL version was obtained from the authors of the study. The SD4-PL scale consists of 28 statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates Strongly disagree and 5 indicates Strongly agree. It is a newly developed scale, methodologically constructed during the work on the adaptation article (71, 72). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in the validation study: psychopathy is.71, narcissism is.79, Machiavellianism is.68, sadism is 77. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the entire scale in the current study is.68.

The SPP-25 was developed by Zygfryd Juczynski and Nina Oginska-Bulik (69). It demonstrates good psychometric properties. Cronbach’s alpha is 0.89, the standard error of measurement for the overall score is 3.81, and the reliability of individual subscales ranges from.67 to.75, which is considered satisfactory. The data comes from the validation study. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the current study is as follows.92. The SPP-25 scale consists of 25 statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 0 indicates Definitely Not and 4 indicates Definitely Yes. The scale measures aspects of psychological resilience understood as personality traits. It can be used to assess personality-based predispositions in individuals, particularly those exposed to stress. The tool is based on self-report. The SPP-25 provides a general resilience score as well as levels of the following five resilience components:

1. Perseverance and determination in action.

2. Openness to new experiences and sense of humor.

3. Personal competence in coping and tolerance of negative emotions.

4. Tolerance of failure and perceiving life as a challenge.

5. Optimistic outlook on life and the ability to mobilize oneself in difficult situations (69).

3.4 Data analysis plan

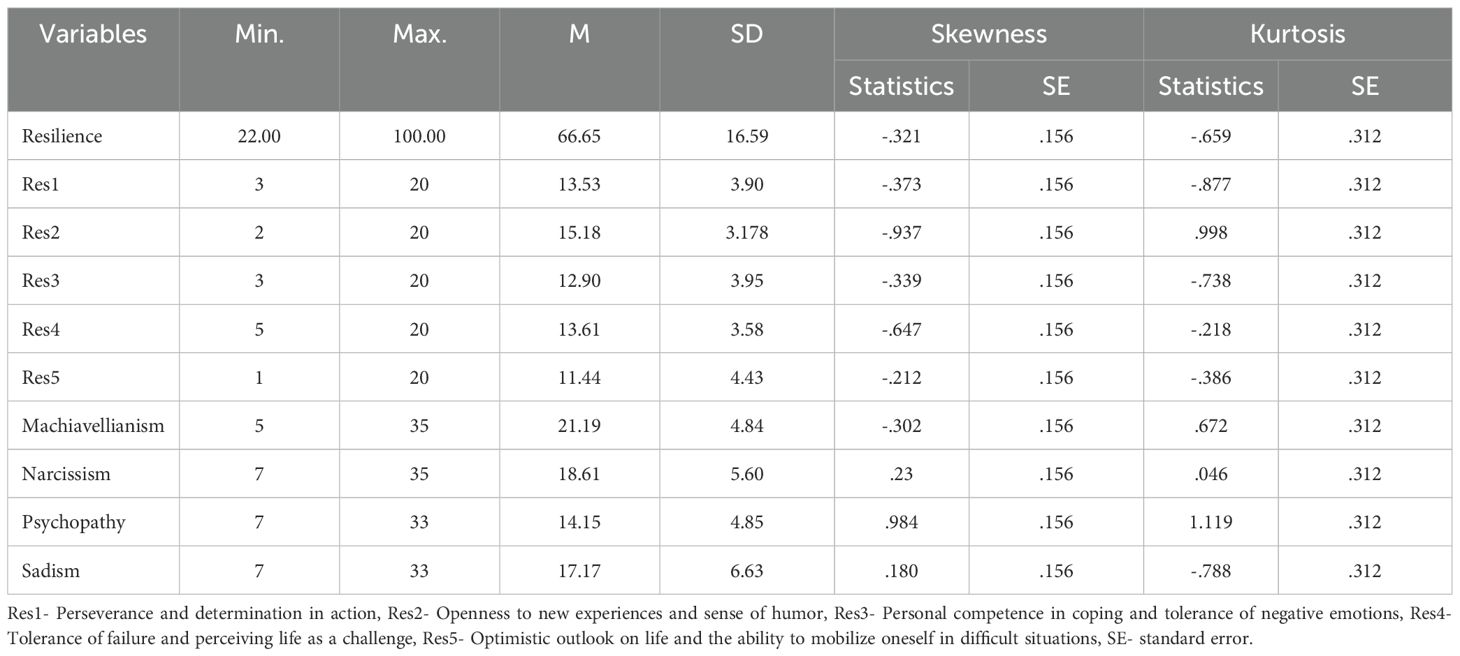

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. Skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the distributions of the variables do not deviate from the normal distribution. To account for more variables, a two-way (2 groups x 2 genders) Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was applied. Dependent variables were narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and sadism. The covariate in our study was resilience. Then, a similar two-way MANCOVA was conducted with five components of resilience as covariates. Next, correlations between the dark tetrad personality traits and resilience were calculated separately for both groups, i.e., transgender and cisgender, and these correlation values were compared between the two groups using a Fisher’s z test.

The data from this study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the studied population.

4 Results

A two-way MANCOVA was conducted to examine the combined effects of group (transgender vs. cisgender) and gender (women vs. men), while controlling psychological resilience as total score on the Dark Tetrad.

Multivariate tests revealed significant effects for group (Wilks’ λ = .75; F(4, 234) = 19.96; p <.001; ηp2 = .25), gender (Wilks’ λ = .88; F(4, 234) = 8.24; p <.001; ηp2 = .12) and their interaction (Wilks’ λ = .93; F(4, 234) = 4.33; p = .002; ηp2 = .07).

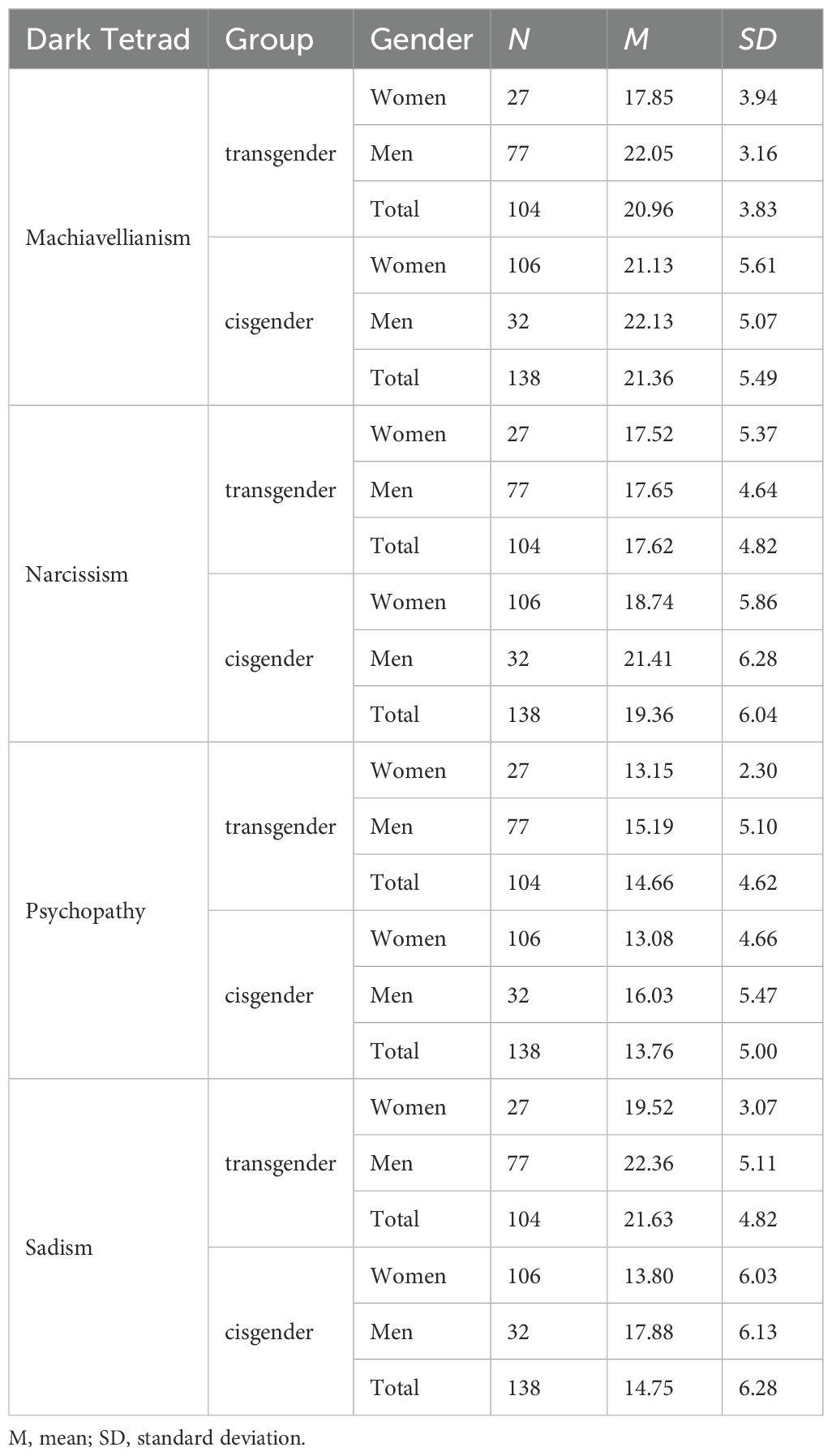

Table 3 presents the results of univariate tests for between-subject effects, showing that group membership differentiated levels of Machiavellianism, and sadism. Gender differentiated Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism. The interaction between group and gender was significant for Machiavellianism and narcissism. No statistically significant differences were found for the remaining Dark Triad dimensions in relation to the analyzed factors or their interaction (Table 3).

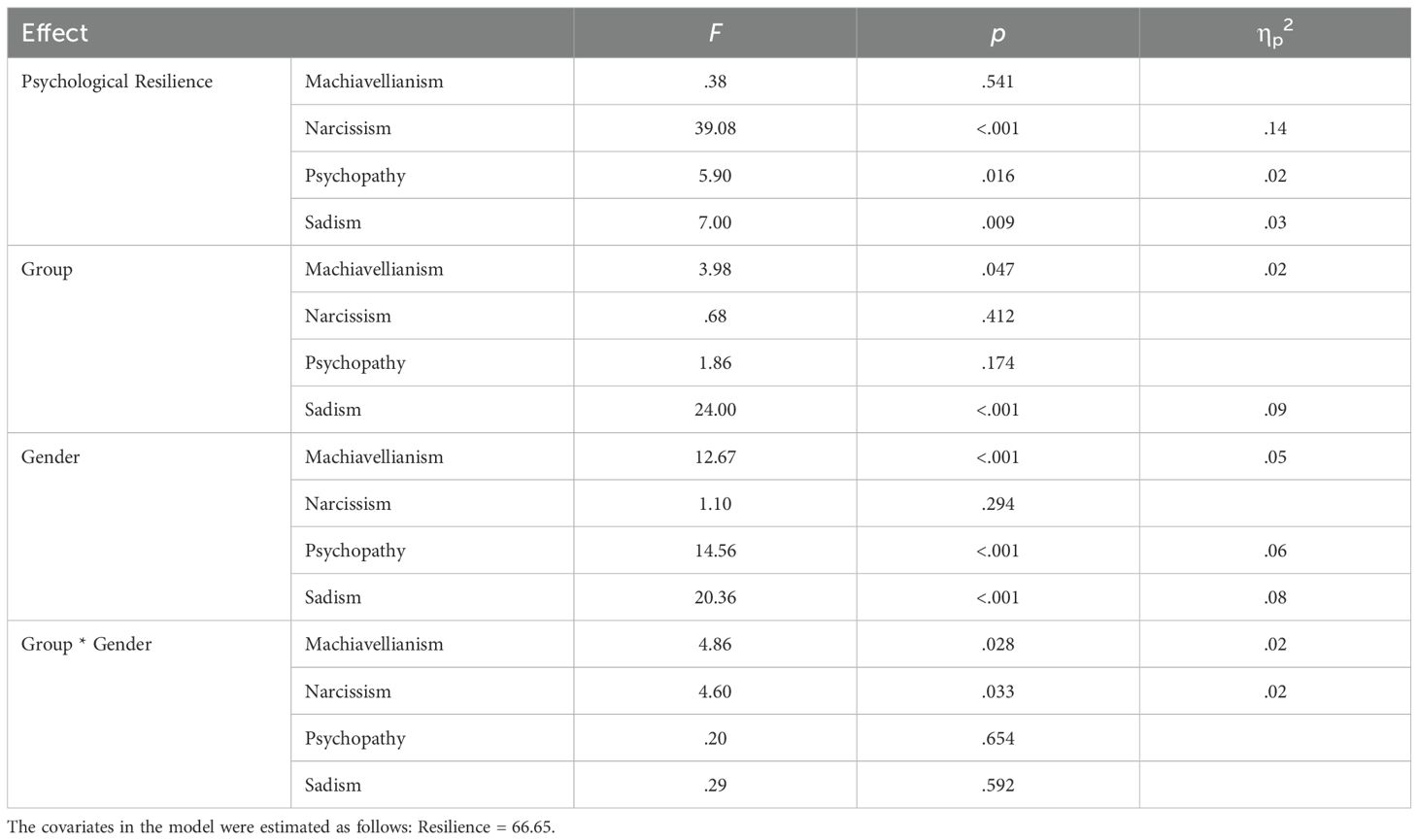

Table 3. Summary of univariate tests for between-subject effects for the Dark Tetrad explanatory model.

A detailed analysis of the comparison of mean scores showed that transgender individuals scored significantly higher on sadism (ΔM = -5.02; p <.001) than cisgender individuals. Women scored significantly lower on Machiavellianism (ΔM = -2.54; p <.001), psychopathy (ΔM = -2.71; p <.001), and sadism (ΔM = -3.72; p <.001) compared to man (Table 4).

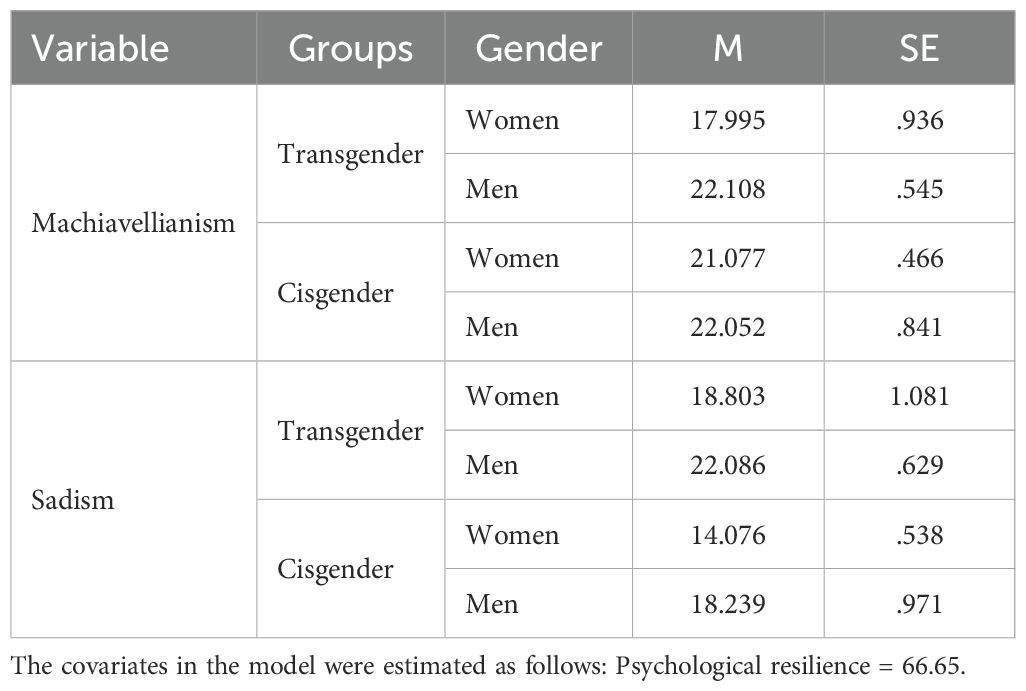

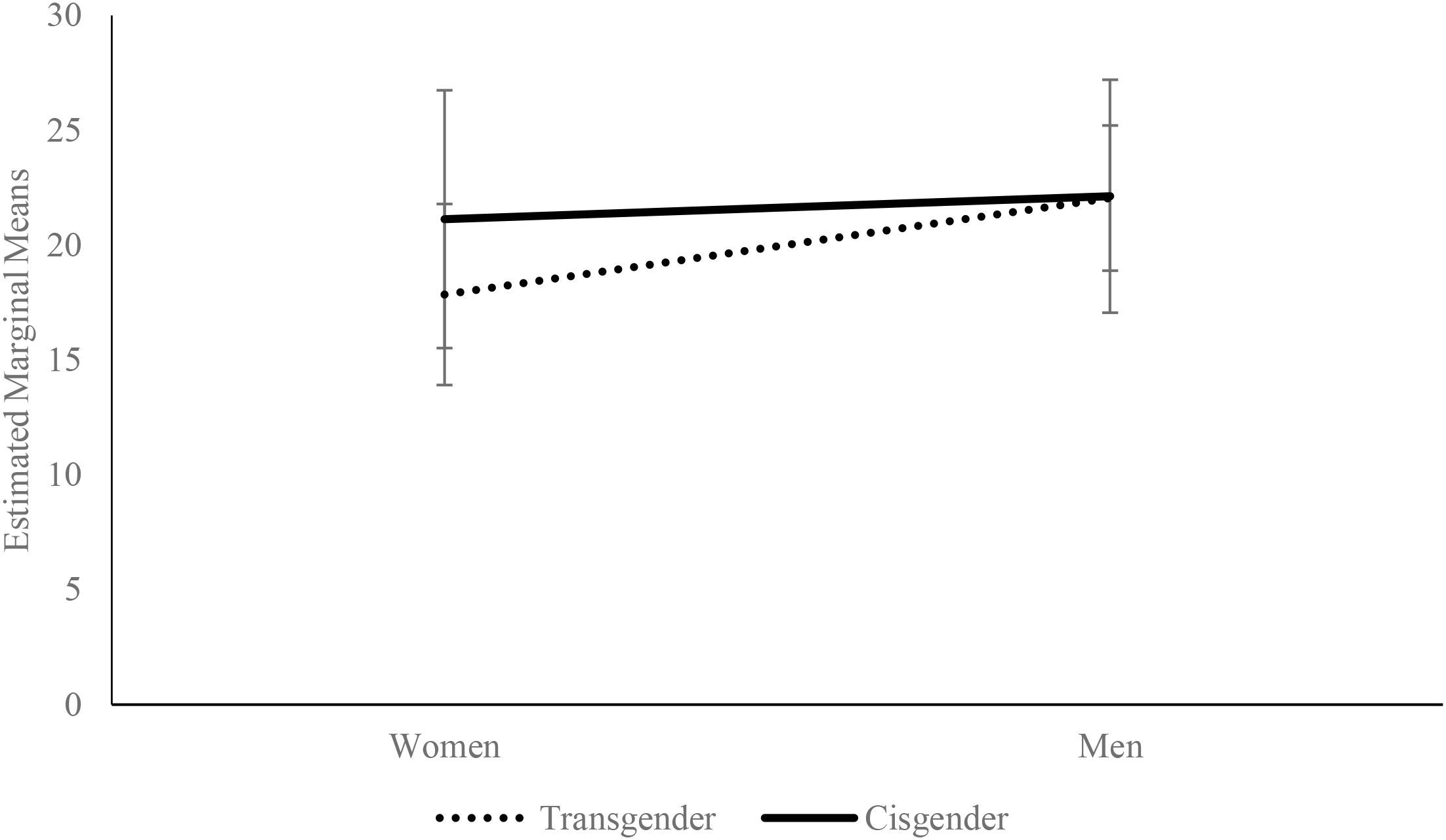

A simple effects analysis of group on Machiavellianism revealed that transgender women exhibited significantly lower levels of Machiavellianism than cisgender women ΔM = -3.08) (Figure 1). This effect was not significant in the male group F(1,237) = .003; p = .956; ηp2 <.01).

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means (± 1 SD) for Machiavellianism by gender and group. The covariates in the model were estimated as follows: Resilience = 66.65.

Although both groups and gender differentiate sadism, there is no significant interaction effect of gender and group on sadism. In both groups, i.e., transgender and cisgender, sadism is higher among men (Table 5).

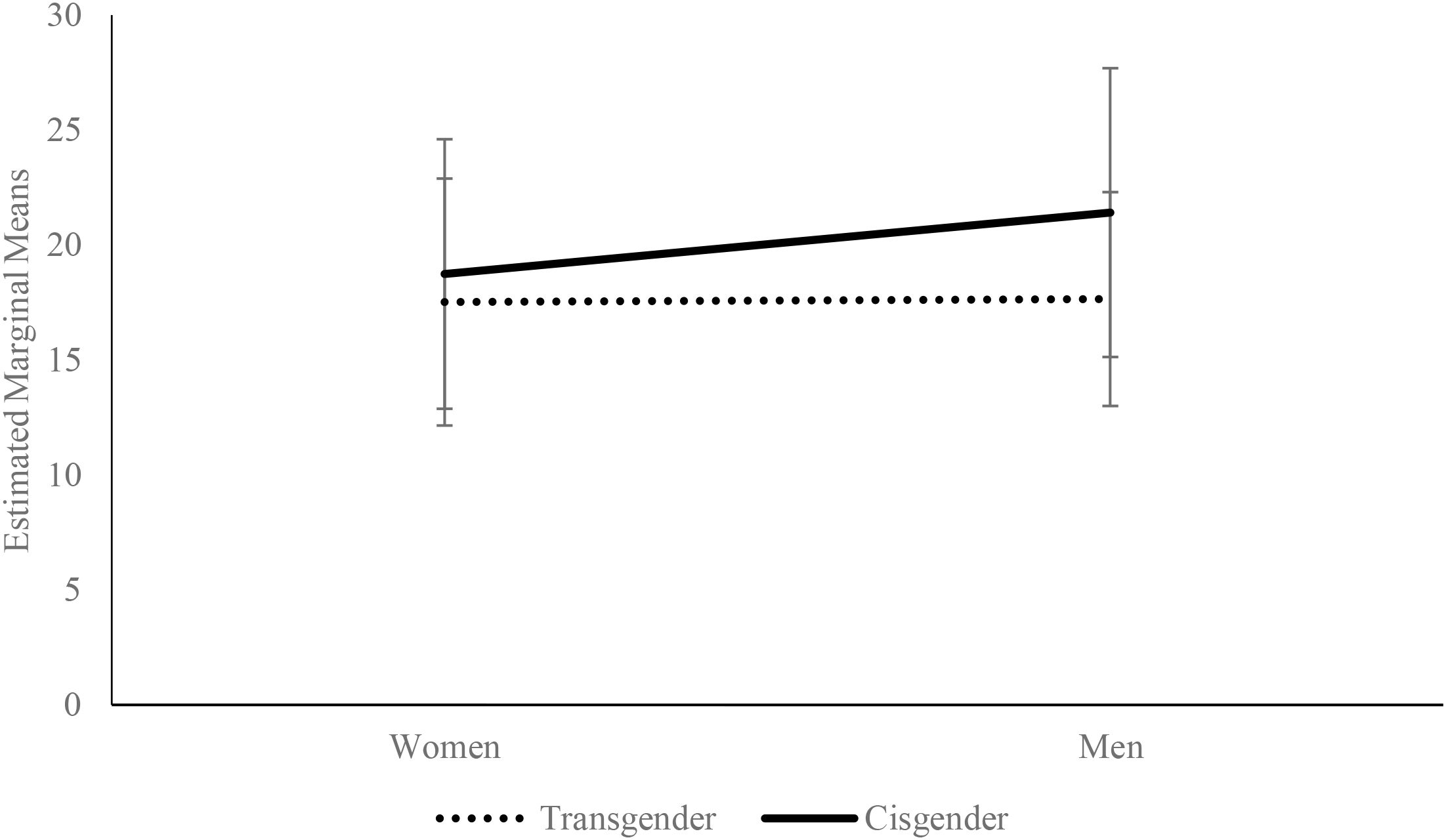

A simple effects analysis for narcissism by group indicated that transgender men exhibited significantly lower levels of narcissism than cisgender men, F(1,237) = 4.50; p = .035; ηp2 = .02; ΔM = -2.33. This effect was not significant in the female group, F(1,237) = 0.72; p = .398; ηp2 = .003. Analysis of simple effects for gender showed that within the cisgender group, women exhibited significantly lower narcissism levels compared to men, F(1,237) = 5.74; p = .017; ηp2 = .02; ΔM = -2.47, whereas no gender differences were observed among transgender individuals (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means (± 1 SD) for Narcissism, by gender and group. The covariates in the model were estimated as follows: Resilience = 66.65.

A second two-way MANCOVA (multivariate analysis of variance) was conducted. This analysis examined potential interactive effects of group (transgender vs. cisgender) and gender (women vs. men). Five covariates were controlled for: perseverance and determination, openness to new experiences and sense of humor, personal competence and tolerance of negative emotions, tolerance of setbacks and treating life as a challenge, and optimism, and the ability to mobilize oneself. The dependent variable was the Dark Tetrad.

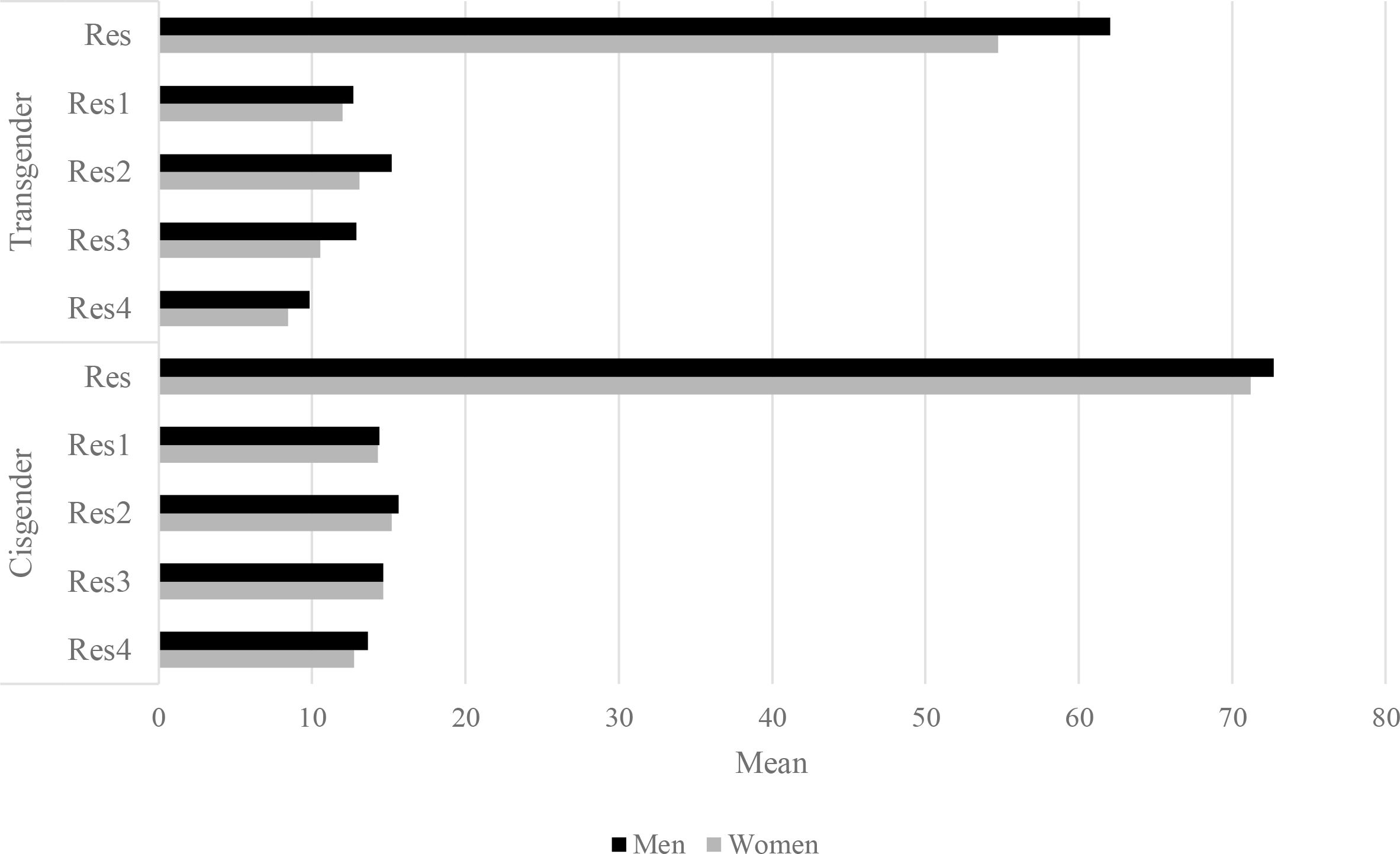

Multivariate tests revealed significant effects for psychological resilience components (Wilks’ λ = .72; F(4, 234) = 23.00; p <.001; ηp2 = .28). Univariate analyses showed the significant effects of group and gender on dark personality dimensions while controlling for resilience components. Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of resilience than cisgender individuals (ΔM = -11.430). Multivariate tests revealed significant effects for group, as well as significant effects for four of the five covariates. Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of perseverance and determination in action than cisgender individuals (Wilks’ λ = .73; F(4, 234) = 20.84; p <.001; ηp2 = .27; ΔM = -1.828). Transgender individuals display significantly lower levels of openness to new experiences and sense of humor than cisgender individuals (Wilks’ λ = .94; F(4, 234) = 3.73; p <.006; ηp2 = .06; ΔM = -.935). Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of tolerance for failures and treating life as challenges than cisgender individuals (Wilks’ λ = .94; F(4, 234) = 3.86; p <.005; ηp2 = .06; ΔM = -2.364). These individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of optimism and ability to mobilize in difficult situations than cisgender individuals (Wilks’ λ = .90; F(4, 234) = 6.58; p <.001; ηp2 = .26; ΔM = -3.50). The only statistical interaction effect of group and gender on Machiavellianism was found while controlling for resilience components. The effect is similar to that of including the overall resilience score as a covariate. To better illustrate the results obtained, Figure 3 displays the average levels of the general resilience score and its components, for which significant interaction effects were identified.

Figure 3. Mean levels of general resilience and resilience components (cisgender vs transgender participants) for dimensions with significant interaction effects. Res- Resilience, Res1- Perseverance and determination in action, Res2- Openness to new experiences and sense of humor, Res3- Tolerance of failure and perceiving life as a challenge, Res4- Optimistic outlook on life and the ability to mobilize oneself in difficult situations.

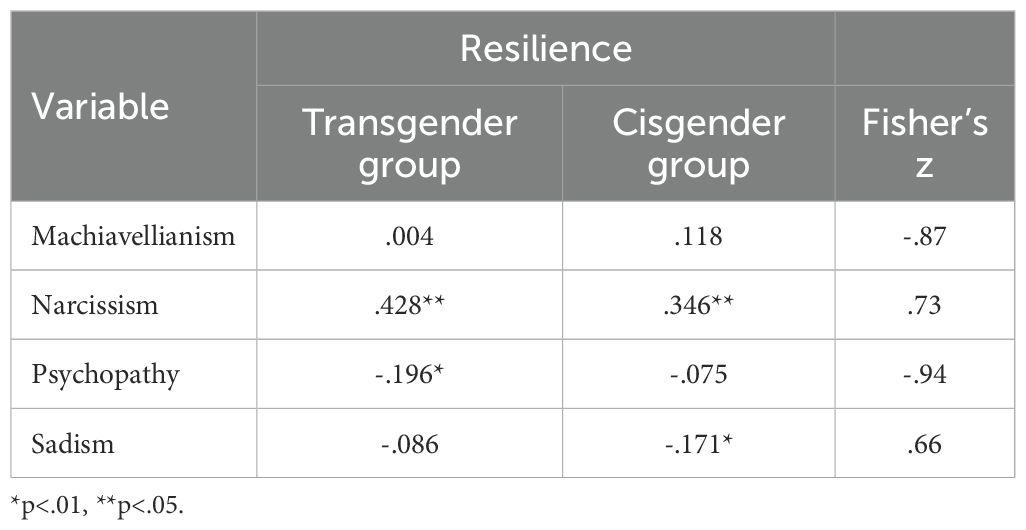

Subsequently, correlations between psychological resilience and dark personality traits were calculated (Table 6). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used, as skewness analysis confirmed a normal distribution in both groups. A significant correlation between psychological resilience and narcissism was found in both groups. The correlation is positive and moderate. The higher the resilience, the higher the narcissism. A weak negative correlation was found between resilience and psychopathy in transgender group. It indicates that the higher the resilience, the lower the psychopathy. A similar weak negative correlation between resilience and sadism was found. The value of Fisher’s z-test indicates no significant difference in correlations between the transgender group and cisgender group (Table 6).

Table 6. Pearson’s correlations between resiliency and the Dark Tetrad in the transgender and cisgender groups.

5 Discussion

Our study results do not confirm higher levels of dark personality traits in transgender people, although the literature on the subject suggests it. When comparing the two groups, researchers found differences in various personality traits (4). However, when we consider more variables, such as gender, the differences are found to be unrelated to transgenderism.

Our study results indicate a slightly lower level of narcissism and Machiavellianism in transgender women compared with cisgender women, and a slightly increased level of sadism in all men, regardless of whether they are transgender or cisgender. No differences were observed between the transgender and cisgender groups in terms of dark personality traits. Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of resilience than cisgender individuals for general resilience and four of the five of its components, such as perseverance and determination in action, openness to new experiences and sense of humor, tolerance for failures and treating life as challenges, and optimism and ability to mobilize in difficult situations.

The slightly lower level of Machiavellianism and narcissism in transgender women may be a consequence of hormonal treatment (73, 74). All cisgender women participating in the study underwent hormone therapy. Year by year, more transgender individuals, and at younger ages, begin hormone therapy. This is not due to an increase in the number of transgender people, but to reduced barriers to access to healthcare and to increased acceptance and destigmatization in society. The rise in the number of people undergoing hormone therapy concerns transgender women to a greater extent, because transgender women have historically experienced higher levels of stigmatization. Earlier initiation of hormone therapy may amplify characteristics typical of women, including lower levels of narcissism and Machiavellianism (75). Transgender women were subjected, during the first several, and in some cases many, years of life, to a masculine model of socialization and later internalized a feminine model. They may have displayed feminine traits earlier and been treated differently by their environment. Protective factors against anxiety symptoms in transgender women include self-esteem and good interpersonal functioning (76). The present study indicated that psychological resilience may mitigate the severity of dark personality traits, but the protective effect is subtle. We had assumed the protective effect would be stronger. This is an important correlation that permits the development of individualized therapeutic intervention plans for transgender women (77).

The gender gap is larger in countries with lower levels of gender equality. In Poland, gender inequality is greater than in Western European countries and the United States; therefore, Machiavellianism among the women in the studied sample is only slightly lower (78–80). In societies with greater gender equality, inter-gender comparisons are more salient and, consequently, gender identity and conformity to social gender norms are more clearly defined. This process may be somewhat stronger among transgender women, which is supported by the findings of the present study. Transgender women are perceived as less feminine and may perceive this as a threat to their femininity. This elicits reactive responses that increase differences between genders. This is manifested in the slightly lower level of Machiavellianism in transgender women compared with cisgender women. Thus, the mechanism that operates among women in societies with greater gender equality may be somewhat stronger in transgender women (36, 81–83). We do not observe an increase in the affirmation of male gender identity that might be expected to be threatened by gender equality, nor do we note an increase in Machiavellianism among transgender men relative to cisgender men. Gender equality does not reinforce a masculine pattern of gender identity (84–86).

The slight, uniformly elevated value of sadism in all men may be caused by men’s tendency toward competition and dominance. This could be connected to testosterone levels (14, 87). In conflictual situations or those perceived as difficult, men’s levels of tension rise and are expressed as anger, rage, and sometimes aggression. Thus, the slight increase in sadism among men may be related to their methods of regulating negative emotions. This issue, however, requires further research (51, 88, 89). It has been observed that the antagonism domain has been reported to show marked gender differences, with men scoring consistently higher than women (90). Manipulativeness, Grandiosity, Collousness, and Hostility, as facets included in the Antagonism domain, seem therefore to be less characteristic of the personality functioning of transgender men as opposed to cisgender men. One speculative explanation for this result could be ascribed to a lower propensity of transmen to a sense of entitlement and self-assertiveness, as they navigate a world in which they are more exposed to aggressions, microaggressions, harassment, and violence than cisgender men (91, 92).

Further research into the personality traits of transgender individuals is needed. Understanding the psychological functioning of transgender people will allow therapeutic processes to be adapted accordingly and reduce the level of minority stress (93). As a result, the quality of life of transgender people will improve.

4.1 Limitations

The interpretation of results regarding personality traits among transgender individuals is limited by the lack of comparable studies and the insufficient volume of such measurements. Additionally, participants in these studies are often at various stages of transition, which significantly affects psychological functioning (94).

Transgender research populations are often limited to those receiving clinical care. This study aimed to avoid that bias by recruiting individuals seeking the mandatory psychological evaluation required for transition, not necessarily those being treated for psychiatric disorders.

A significant challenge lies in assembling a gender-diverse research group. As in many studies, this one showed a predominance of transgender men (74%) compared to transgender women (26%). Efforts were made to minimize the impact of this imbalance by deliberately selecting a gender-balanced control group.

Another issue is the self-measure techniques we used. Self-report measures usually provide a less accurate description of personality functioning than the clinician assessment.

5 Conclusions

The study results indicate a slightly lower level of narcissism and Machiavellianism in transgender women compared with cisgender women, and a slightly increased level of sadism in all men, regardless of whether they are transgender or cisgender. No differences were observed between the transgender and cisgender groups in terms of dark personality traits. Transgender individuals exhibited significantly lower levels of resilience than cisgender individuals for general resilience and four of the five components, such as perseverance and determination in action, openness to new experiences and sense of humor, tolerance for failures and treating life as challenges, and optimism and ability to mobilize in difficult situations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Humanitas University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AM: Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Formal analysis, Project administration, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. BG: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that financial support for the research and publication of this article was provided by Humanitas University (Sosnowiec, Poland). The content is the responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Arcelus J, Bouman WP, Van Den Noortgate W, Claes L, Witcomb G, and Fernandez- Aranda F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in transsexualism. Eur Psychiatry. (2015) 30:807–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.005

2. Jones AK, Wehner CL, Andrade IM, Jones EM, Wooten LH, and Wilson LC. Minority stress and posttraumatic growth in the transgender and nonbinary community. Psychol Sexual Orientation Gender Diversity. (2024) 11:488–97. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000610

3. Xia N and Liu A. A review of mental health in transgender people. Chin Ment Health J. (2021) 35:231–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.03.010

4. Anzani A, De Panfilis C, Scandurra C, and Prunas A. Personality disorders and personality profiles in a sample of transgender individuals requesting gender-affirming treatments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1521. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051521

5. Charkhgard A and Kakavand A. Gender identity disorder and improvement of life satisfaction and psychological well-being indices after sex reassignment surgery: A multicenter prospective cohort study. JPCP. (2024) 12:27–32. doi: 10.32598/jpcp.12.1.760.1

6. Crowter J. To be that self which one truly is”: trans experiences and rogers’ Theory of personality. Person-Centered Experiential Psychotherapies. (2022) 21:293–308. doi: 10.1080/14779757.2022.2028665

7. Furente F, Matera E, Margari L, Lavorato E, Annecchini F, Scarascia Mugnozza F, et al. Social introversion personality trait as predictor of internalizing symptoms in female adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:3236. doi: 10.3390/jcm12093236

8. Pfeffer CA. Transgender sexualities. In: Goldberg AE, editor. The SAGE encyclopedia of LGBTQ studies. SAGE Publications (2016). p. 1247–51. Available online at: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-lgbtq-studies-2nd-edition/book283559 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

9. Lev AI. Gender dysphoria: two steps forward, one step back. Clin Soc Work J. (2013) 41:288–96. doi: 10.1007/s10615-013-0447-0

10. Cabrera C, Dueñas J-M, Cosi S, and Morales-Vives F. Transphobia and gender bashing in adolescence and emerging adulthood: the role of individual differences and psychosocial variables. Psychol Rep. (2022) 125:1648–66. doi: 10.1177/00332941211002130

11. Cole CM, O’Boyle M, Emory LE, and Meyer WJ III. Comorbidity of gender dysphoria and other major psychiatric diagnoses. Arch Sex Behav. (1997) 26:13–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1024517302481

12. Goldhammer H, Crall C, and Keuroghlian AS. Distinguishing and addressing gender minority stress and borderline personality symptoms. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2019) 27:317–25. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000234

13. Mizock L and Lewis TK. Trauma in transgender populations: Risk, resilience, and clinical care. JEA. (2008) 8:335–54. doi: 10.1080/10926790802262523

14. Liu Y, Wang Z, Dong H, et al. Assessment of psychological personality traits in transgender groups using the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1416011. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1416011

15. Zhang F, Zhang J, and Li X. A review of the development of the research on personality characteristics in people with gender dysphoria. Psychol Commun. (2022) 3:252–7. doi: 10.12100/j.issn.2096-5494.22008

16. Bonierbale M, Baumstarck K, Maquigneau A, et al. MMPI-2 profile of french transsexuals. The role of sociodemographic and clinical factors A cross-sectional design. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:1038. doi: 10.1038/srep24281

17. Miach PP, Berah EF, Butcher JN, and Rouse S. Utility of the MMPI-2 in assesing gender dyshoric patients. J Pers Assess. (2000) 75:268–79. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7502_7

18. Livingston NA, Heck NC, Flentje A, Gleason H, Oost KM, and Cochran BN. Sexual minority stress and suicide risk: Identifying resilience through personality profile analysis. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. (2015) 2:321–8. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000116

19. Marsman MA. Transgenderism and transformation: an attempt at a Jungian understanding. J Anal Psychol. (2017) 62:678–87. doi: 10.1111/1468-5922.12356

20. Cavanaugh T, Hopwood R, and Lambert C. Informed consent in the medical care of transgender and gender- nonconforming patients. AMA J Ethics. (2016) 18:1147–55. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.11.sect1-1611

21. Bocting W. The impact of stigma on transgender identity development and mental health. In: Kreulkels BPC, Steensma T, and de Vries ALC, editors. Gender dyshoria and disorders of sex development. Springer, New York- Heidelberg- Dordrecht- London (2014). p. 319–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7441-8_16

22. Carmel TC and Erickson-Schroth L. Mental health and the transgender population. Psychiatr Ann. (2016) 46:346–9. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20160419-02

23. Bryant WT, Livingston NA, McNulty JL, Choate KT, and Brummel BJ. Examining Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF) scale scores in a transgender and gender diverse sample. Psychol Assess. (2021) 33:1239–46. doi: 10.1037/pas0001087

24. Denny D. Changing models of transsexualism. J Gay& Lesb. (2004) 8:.25–40. doi: 10.1300/J236v08n01_04

25. Drescher J. Queer diagnoses revisited: The past and future of homosexuality and gender diagnoses in DSM and ICD. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2015) 27:386–95. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1053847

26. Magann S, Dahlenburg SC, and Bartsch DR. Exploring personality pathology and minority stress among Australian sexual and gender minorities. Pers. Disord.: Theory Res Treat. (2025) 16(6):540–9. doi: 10.1037/per0000735

27. Duišin D, Batinić B, Barišić J, Djordjevic ML, Vujović S, and Bizic M. Personality disorders in persons with gender identity disorder. Sci World J. (2014) 2014:809058. doi: 10.1155/2014/809058

28. Ganguly J and Mathur K. Personality and social adjustment among transgender. Indian J Health Wellbeing. (2016) 7:1131–4. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/fffcb5072183e91258fa7718608531a1/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2032134 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

29. Meybodi AM, Hajebi A, and Jolfaei AG. The frequency of personality disorders in patients with gender identity disorder. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2014) 28:90. Available online at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4301205/ (Accessed November 01, 2025).

30. Furnham A, Richards SC, and Paulhus DL. The dark triad of personality: A 10 year review. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. (2013) 7:199–216. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12018

31. Galan M, Pineda D, Rico-Bordera P, Piqueras J, and Muris P. Dark childhood, dark personality: Relations between experiences of child abuse and dark tetrad traits. Pers Individ Dif. (2025) 238:113089. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2025.113089

32. Maples- Keller JL and Miller JD. Insight and the Dark Triad: Comparing self- and meta- perceptions in relation to psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism. Pers Disord.: TRT. (2018) 9:30–9. doi: 10.1037/per0000207

33. Paulhus DL and Williams KM. The dark triad of personality: narcissism, machavellianism and psychopathy. J Res Pers. (2002) 36:556–63. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

34. Plouffe RA, Wilson CA, and Saklofske DH. Examining the relationships between childhood exposure to intimate partner violence, the dark tetrad of personality, and violence perpetration in adulthood. J Interpers Violence. (2022) 37:NP3449–73. doi: 10.1177/0886260520948517

35. Paulhus DL, Buckels EE, Trapnell PD, and Jones DN. Screening for dark personalities. Eur J Psychol Assess. (2020) 37:208–22. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000602

36. Confino D, Ghisletta P, Stoet G, and Falomir-Pichastor JM. National gender equality and sex differences in Machiavellianism across countries. Int J Pers Psychol. (2024) 10:105–15. doi: 10.21827/ijpp.10.41854

37. Schmitt DP, Realo A, Voracek M, and Allik M. Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2008) 94:168. doi: 10.1037/a0014651

38. Falk A and Hermle J. Relationship of gender differences in preferences to economic development and gender equality. Sci. (2018) 362:eaas9899. doi: 10.1126/science.aas9899

39. Arat ZFK. Feminisms, women’s rights, and the UN: Would achieving gender equality empower women? Am Political Sci Rev. (2015) 109:674–89. doi: 10.1017/S0003055415000386

40. Costa PT Jr., Terracciano A, and McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: robust and surprising findings. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2001) 81:322. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2001-01642-012 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

41. Weidmann R, Chopik WJ, Ackerman RA, Allroggen M, Bianchi EC, Brecheen C, et al. Age and gender differences in narcissism: A comprehensive study across eight measures and over 250,000 participants. J Pers. Soc Psychol. (2023) 124:1277–98. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000463

42. Eagly AH and Wood W. Social role theory. In: van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, and Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of theories in social psychology, vol. 2 . New York: SAGE Open (2011). p. 458–476). doi: 10.4135/9781446249222.n46

43. Basto-Pereira M, Gouveia-Pereira M, Pereira CR, Barrett EL, Lawler S, Newton N, et al. The global impact of adverse childhood experiences on criminal behavior: A cross-continental study. Child Abuse Negl. (2022) 124:105459. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105459

44. Green A, MacLean R, and Charles K. Recollections of parenting styles in the development of narcissism: The role of gender. Pers Individ Dif. (2020) 167:110246. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110246

45. Grijalva E, Newman DA, Tay L, Donnellan MB, Harms PD, Robins RW, et al. Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. (2015) 141:261–310. doi: 10.1037/a0038231

46. Orth U, Krauss S, and Back MD. Development of narcissism across the life span: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. (2024) 150:643. doi: 10.1037/bul0000436

47. Twenge JM. Status and gender: the paradox of progress in an age of narcissism. Sex Roles. (2009) 61:338–40. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9617-5

48. Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Nelemans SA, Orobio de Castro B, Castro B, Overbeek G, et al. Origins of narcissism in children. PNAS. (2015) 112:3659–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420870112

49. Nickisch A, Palazova M, and Ziegler M. Dark personalities–dark relationships? An investigation of the relation between the Dark Tetrad and attachment styles. Pers Individ Dif. (2020) 167:110227. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110227

50. Plouffe RA, Saklofske DH, and Smith MM. The assessment of sadistic personality: Preliminary psychometric evidence for a new measure. Pers Individ Dif. (2017) 104:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.043

51. Buckels EE, Jones DN, and Paulhus DL. Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychol Sci. (2013) 24:2201–9. doi: 10.1177/0956797613490749

52. Bryant WT, Livingston NA, McNulty JL, Choate KT, Santa Ana EJ, and Ben-Porath YS. Exploring the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)-3 in a transgender and gender diverse sample. Psychol Assess. (2024) 36:1–13. doi: 10.1037/pas0001287

53. Caspi A, Roberts BW, and Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol. (2005) 56:453–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

54. Kaplan HS and Gangestad SW. Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. Handb. Evol Psychol. (2015), 68–95. doi: 10.1002/9780470939376.ch2

55. Keo- Meier CL, Herman LJ, Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Sharp C, and Babcock JC. Testosterone treatment and MMPI-2 improvement in transgender men: A prospective controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2015) 83:143–56. doi: 10.1037/a0037599

56. Ashley F. The Misuse of gender dysphoria: Toward greater conceptual clarity in transgender health. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2019) 16:1159–64. doi: 10.1177/1745691619872987

57. Csathó Á and Birkás B. Early-life stressors, personality development, and fast life strategies: An evolutionary perspective on malevolent personality features. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00305

58. Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, and Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2016) 28:36–43. doi: 10.4324/9781315446806

59. Block JL and Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1996) 70:349. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1996-01717-012 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

60. Letzring TD, Block J, and Funder DC. Adapting to life’s slings and arrows: Individual differences in resilience when recovering from an anticipated threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2005) 42:1031–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.02.005

61. Mansouri Z, Mousavi- Nasab H, and Shamsodini LL. A study of the mediating role of resilience in personality characteristics and attitudes toward delinquency. Fundam. Ment Health. (2015) 17:103–10. doi: 10.22038/jfmh.2015.4033

62. Nakaya M, Oshio A, and Kaneko H. Correlations for adolescent resilience scale with big five personality traits. Psychol Rep. (2006) 98:927–30. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.3.927-930

63. Oshio A, Taku K, Hirano M, and Saeed G. Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta- analysis. Pers Individ Dif. (2018) 127:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048

64. Flynn SS, Touhey S, Sullivan TR, and Mereish EH. Queer and transgender joy: A daily diary qualitative study of positive identity factors among sexual and gender minority adolescents. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. (2024). doi: 10.1037/sgd0000733

65. Pinna F, Paribello P, Somaini G, Corona A, Ventriglio A, Corrias C, et al. Mental health in transgender individuals: a systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2022) 34:292–359. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2022.2093629

66. Shipherd JC, Green KE, and Abramovitz S. Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing bariers to mental health treatment. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. (2010) 14:94–108. doi: 10.1080/19359701003622875

67. Sloan CA, Berke DS, and Shipherd JC. Utilizing a dialectical framework to inform conceptualization and treatment of clinical distress in transgender individuals. Prof. Psychol Res Pr. (2017) 48:301–9. doi: 10.1037/pro0000146

68. Nolan IT, Kuhner CJ, and Dy GW. Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. (2019) 8:184. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.04.09

69. Ogińska-Bulik N and Juczyński Z. Skala pomiaru prężności–SPP-25. Now. Psych. (2008) 3:39–56. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zygfryd-Juczynski-3/publication/284689565_Skala_pomiaru_preznosci/links/565c2def08ae4988a7bb63b1/Skala-pomiaru-preznosci.pdf (Accessed November 01, 2025).

70. Paulhus DL, Buckels EE, Trapnell PD, and Jones DN. screening for dark personalities. The short dark tetrad (SD4). Eur J Psychol Assess. (2021) 37:208–22. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000602

71. Dębski P, Pałczyński P, Garczarczyk M, Piankowska M, Haratyk K, Noras M, et al. Short Dark Tetrad- Polish version (SD4-PL)- examination of psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism and sadism- preeleminary psychometric properties of the tool in Polish conditions. In: 33rd European Congress of Psychiatry (EPA 2025) - “Towards Real-World Solutions in Mental Health”. Madrit [Spain]: Cambridge University Press (2025). Available online at: https://b-com.mci-group.com/CommunityPortal/ProgressivePortal/EPA2025/App/Views/InformationPage/View.aspx?InformationPageID=18060 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

72. Dębski P, Pałczyński P, Garczarczyk M, Piankowska M, Haratyk K, Noras M, et al. The dark tetrad of personality among men and women in Poland. Eur J Psychol Open. (2025) 84:498. doi: 10.1024/2673-8627/a000085

73. Pfattheicher S. Testosterone, cortisol and the Dark Triad: Narcissism (but not Machiavellianism or psychopathy) is positively related to basal testosterone and cortisol. Pers Individ Dif. (2016) 97:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.015

74. Wei M, Li J, Wang X, Su Z, and Luo YL. Will the dark triad engender psychopathological symptoms or vice versa? A three-wave random intercept cross-lagged panel analysis. J Pers. (2025) 93:767–80. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12974

75. Leinung MC and Joseph J. Changing demographics in transgender individuals seeking hormonal therapy: Are trans women more common than trans men? Transgender Health. (2020) 5:241–5. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2019.0070

76. Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, Crawford JR, Millet N, Fernandez- Aranda PD, et al. Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int J Transgend. (2016) 18:16–26. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1258352

77. Vaishnav K, Singh A, and Mazumdar S. Relationship between personality traits and resilience of transgenders: A review. Int J Indian Psychol. (2024) 12. doi: 10.25215/1202.227

78. Jonason PK, Żemojtel-Piotrowska M, Piotrowski J, Sedikides C, Campbell WK, Gebauer JE, et al. Country-level correlates of the Dark Triad traits in 49 countries. J Pers. (2020) 88:1252–67. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000602

79. Malghan D and Swaminathan H. Global trends in intra-household gender inequality. J Econ Behav Organ. (2021) 189:515–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.07.022

80. Sharma RR, Chawla S, and Karam CM. 10. Global Gender Gap Index: world economic forum perspective. In: Ng ES, Stamper CL, and Han Y, editors. Handbook on Diversity and Inclusion Indices: A Research Compendium. Edward Elgar Publishing (2021). p. 150–64. Available online at: https://books.google.pl/books?hl=pl&lr=&id=fXA4EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA150&dq=Sharma,+R.R.,+Chawla,+S.,+and+Karam,+C.M.+(2021).+10.+global+gender+gap+index:+world+economic+forum+perspective.+Handbook+on+Diversity+and+Inclusion+Indices:+A+Research+Compendium,+150.+&ots=q_zQBrSJGs&sig=2li3asBJx5yx8fNcH1iCVd-JtNU&redir_esc=yv=onepage&q&f=false (Accessed November 01, 2025).

81. Fischer AH and Manstead A. The relation between gender and emotions in different cultures. In: Fisher AH, editor. Gender and emotion. Social psychological perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2000). p. 71–94.

82. Guimond S, Branscombe NR, Brunot S, Buunk AP, Chatard A, Desert M, et al. Culture, gender, and the self: Variations and impact of social comparison processes. J Pers. Soc Psychol. (2007) 92:1118. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1118

83. Jones DN and Paulhus DL. Machiavellianism. In: Leary MR and Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of individuals differences in social behawior. The Guilford Press (2009). p. 93–108. Available online at: https://books.google.pl/books?hl=pl&lr=&id=VgcGZ5sCEcIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=M.R.+Leary+and+R.H.+Hoyle+(eds.).+Handbook+of+individuals+differences+in+social+behawior&ots=kCG76OWRxr&sig=8XkhvpAhmj0zlCc5vuBpvbvLZVY&redir_esc=yv=onepage&q=M.R.%20Leary%20and%20R.H.%20Hoyle%20(eds.).%20Handbook%20of%20individuals%20differences%20in%20social%20behawior&f=false (Accessed November 01, 2025).

84. Falomir-Pichastor JM, Mugny G, and Berent J. The side effect of egalitarian norms: Reactive group distinctiveness, biological essentialism, and sexual prejudice. Group Processes Intergroup Relations. (2017) 20:540–58. doi: 10.1177/1368430215613843

85. Thompson EH Jr. and Bennett KM. Measurement of masculinity ideologies: A (critical) review. Psychol Men. Masc. (2015) 16:115. doi: 10.1037/a0038988

86. Vandello JA and Bosson JK. Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychol Men Masc. (2013) 14:101. doi: 10.1037/a0029826

87. Thomas L and Egan V. A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the relationship between everyday sadism and aggression: Can subclinical sadistic traits predict aggressive behaviour within the general population? Aggress. Violent Behav. (2022) 65:101750. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2022.101750

88. Johnson LK, Plouffe RA, and Saklofske DH. Subclinical sadism and the dark triad. J Individ. Differ. (2019) 40:127–33. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000284

89. Moor L and Anderson JR. A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviours. J Individ. Differ. (2019) 144:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.027

90. Fossati A, Borroni S, Somma A, et al. PID-5 ADULTI: Manuale d’uso della versione Italiana. Raffello Cortina Editore(2016). Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11768/50092 (Accessed November 01, 2025).

91. Nadal KL, Skolnik A, and Wong Y. Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. JLGBTTIC. (2012) 6:55–82. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2012.648583

92. Prunas A, Bandini E, Fisher AD, Maggi M, Pace V, Quagliarella L, et al. Experiences of discrimination, harassment, and violence in a sample of Italian transsexuals who have undergone sex-reassignment surgery. J Interpers Violence. (2018) 33:2225–40. doi: 10.1177/0886260515624233

93. Mizock L and Lundquist C. Missteps in psychoterapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. PSOGD. (2016) 3:148–55. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000177

94. Gijs L, van der Putten- Bierman E, and De Cuypere G. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with gender identity problems. In: Kreukels BPC, Steensma T, and de Vries ALC, editors. Gender dysphoria and disorders of sex development. Springer, New York- Heidelberg- Dordrecht- London (2014). p. 255–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7441-8_13

Keywords: transgender, dark personality tetrad, resilience, narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, sadism

Citation: Mateja A and Gawda B (2025) Low level of dark personality traits in transgender people and their relationships with resilience. Front. Psychiatry 16:1674117. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1674117

Received: 27 July 2025; Accepted: 24 October 2025;

Published: 07 November 2025.

Edited by:

Magdalena Piegza, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, PolandReviewed by:

Marta Leuenberger, University of Basel, SwitzerlandManuel Galán, Catholic University San Antonio of Murcia, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Mateja and Gawda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Agnieszka Mateja, YWduaWVzemthLm1hdGVqYUBodW1hbml0YXMuZWR1LnBs

†ORCID: Agnieszka Mateja, orcid.org/0000-0002-7279-2823

Barbara Gawda, orcid.org/0000-0002-6783-1779

Agnieszka Mateja

Agnieszka Mateja Barbara Gawda

Barbara Gawda